Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. AE-Based Corrosion Imaging

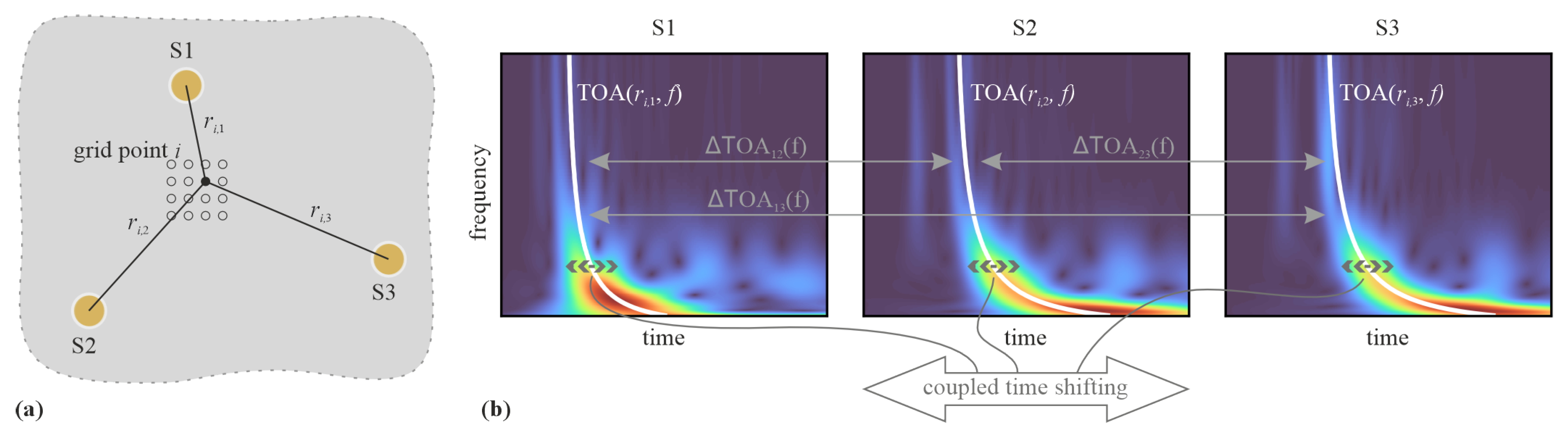

2.2. Model-Based AE Source Localization Algorithm

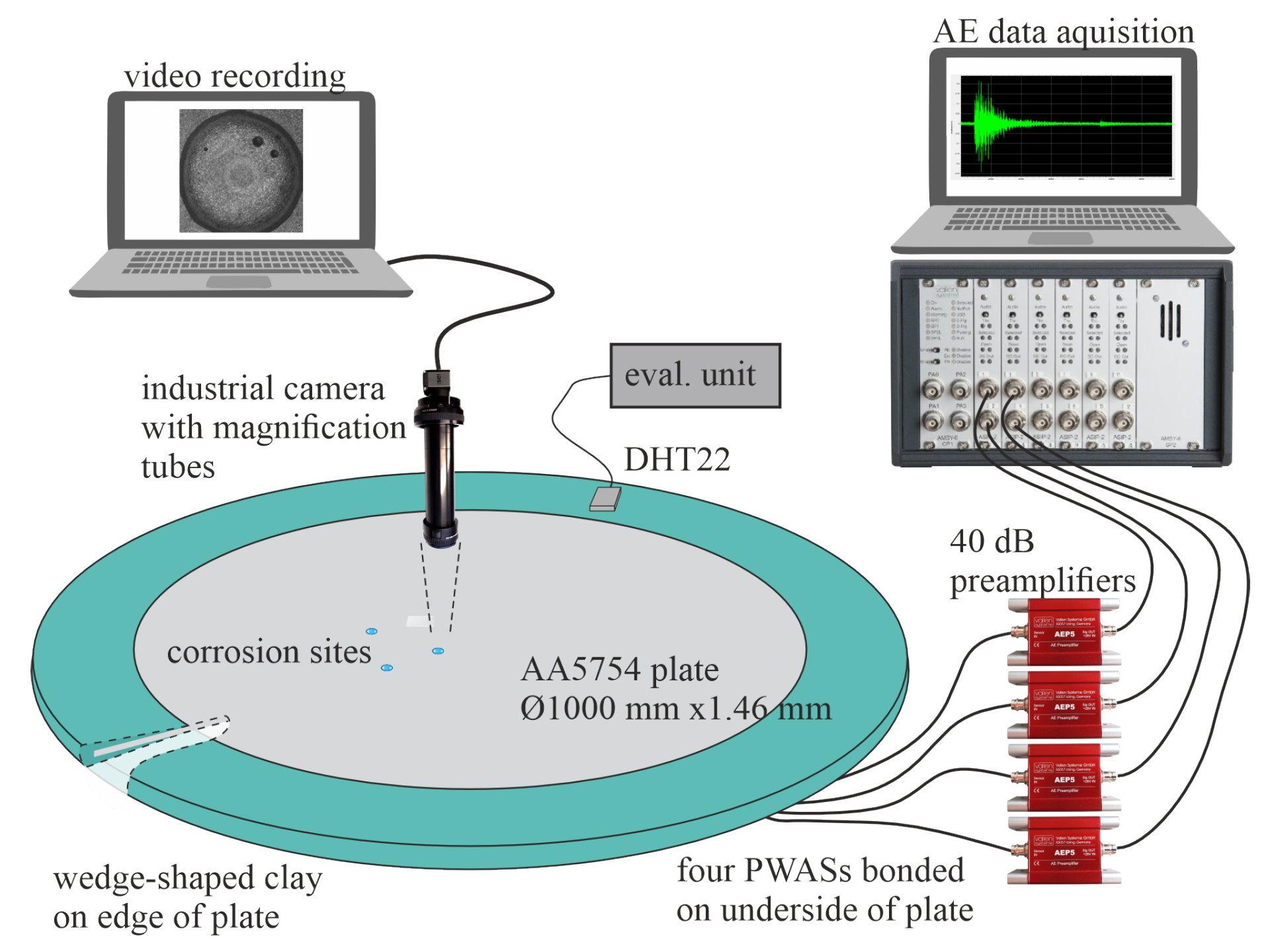

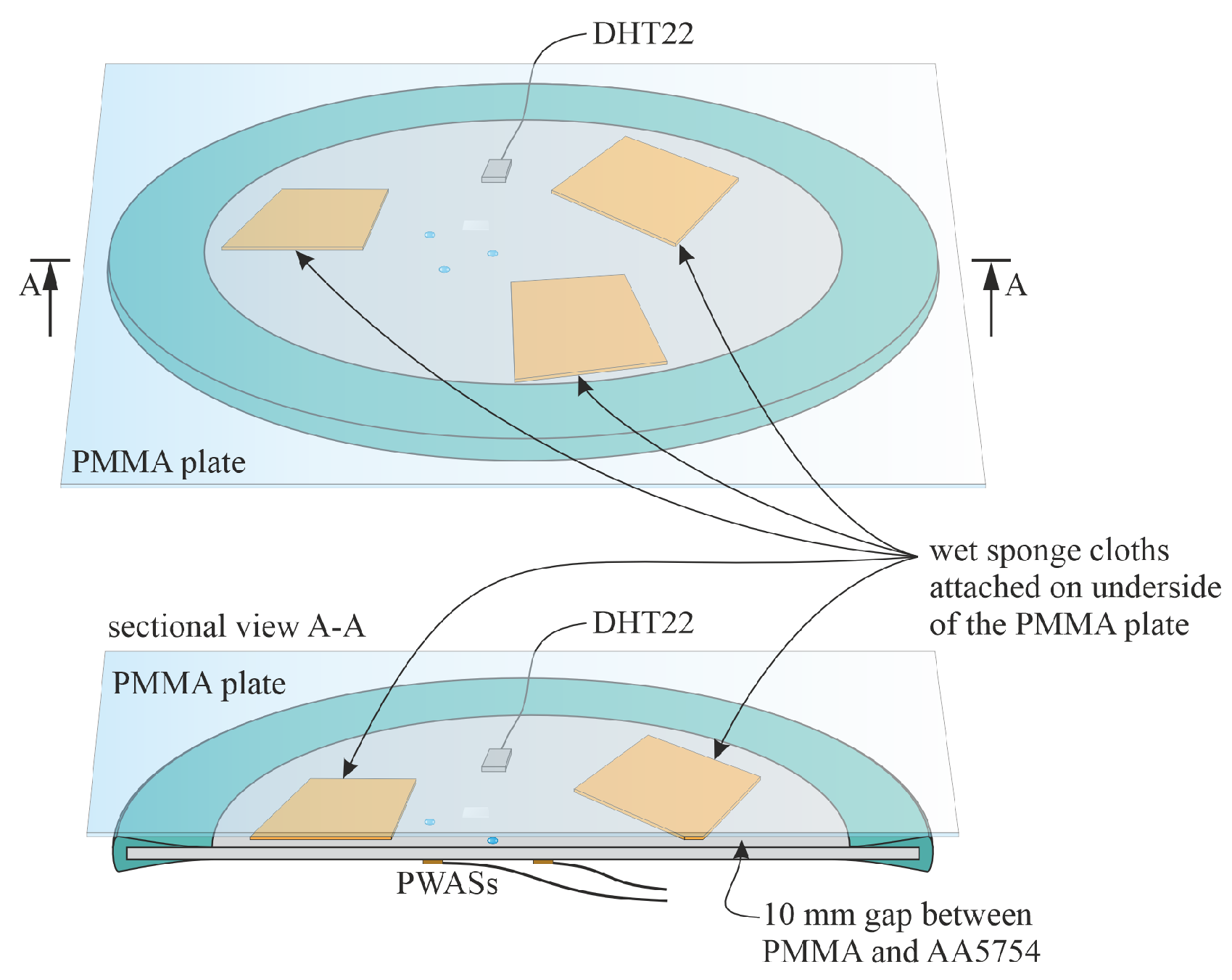

2.3. Experimental Setup and Procedure

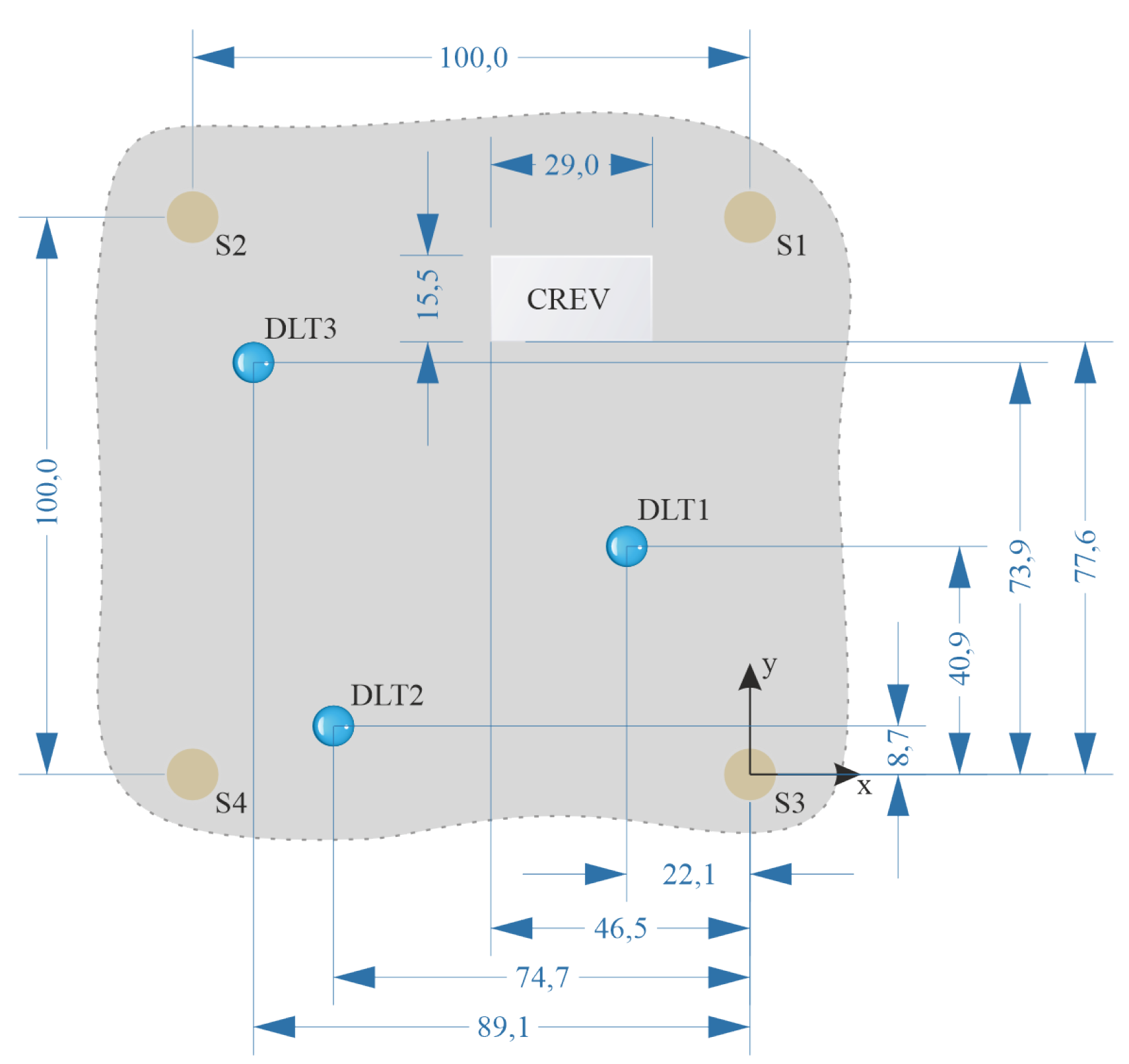

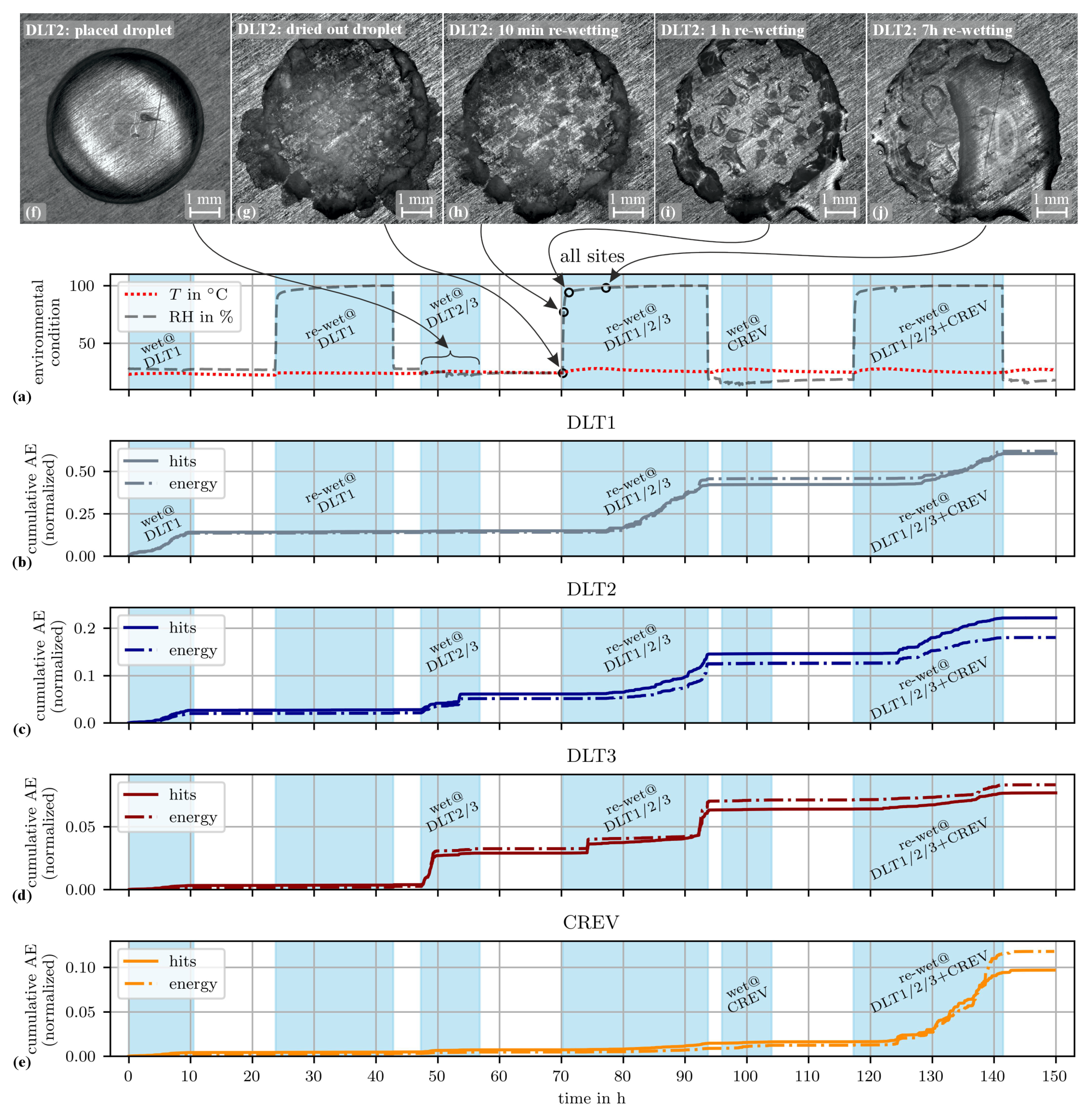

- A droplet of the NaCl solution was placed at site DLT1. To avoid evaporation, 0.03 mL of the NaCl solution was added hourly to the droplet. After about 9 h from the start no more solution was added. The droplet evaporated. Re-wetting was forced after about 30 h from the placement of the first droplet, the wet state was maintained for about 18 h. Afterwards the evaporation was initiated by removing the PMMA plate from the aluminum alloy plate resulting in exposure to room conditions.

- One droplet was placed at site DLT2 and another one at site DLT3. 0.03 mL of distilled water were added hourly to each droplet to avoid full evaporation. After 8 h no more water was added to allow full evaporation. The re-wetting phase started after 24 h resulting in electrolyte accumulations at sites DLT1, DLT2 and DLT3. This wet state was kept for another 24 h. Afterwards the evaporation was initiated by removing the PMMA plate.

- Several droplets were given to the edges of the glass plate at position CREV. The solution was soaked under the glass plate. Small droplets of distilled water were applied on the edges of the glass plate half-hourly due to the warm and dry conditions (27 °C and 15 %RH) in the laboratory. After about 8 h no more water was added to allow the evaporation. The re-wetting phase started after about 22 h resulting in electrolyte accumulations at sites DLT1, DLT2, DLT3 and around CREV. The wet state was maintained for 24 h. Afterwards final evaporation was initiated by removing the PMMA plate.

2.4. Acoustic Emission Data Acquisition and Pre-Filtering

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Environmental Conditions and AE Correlation

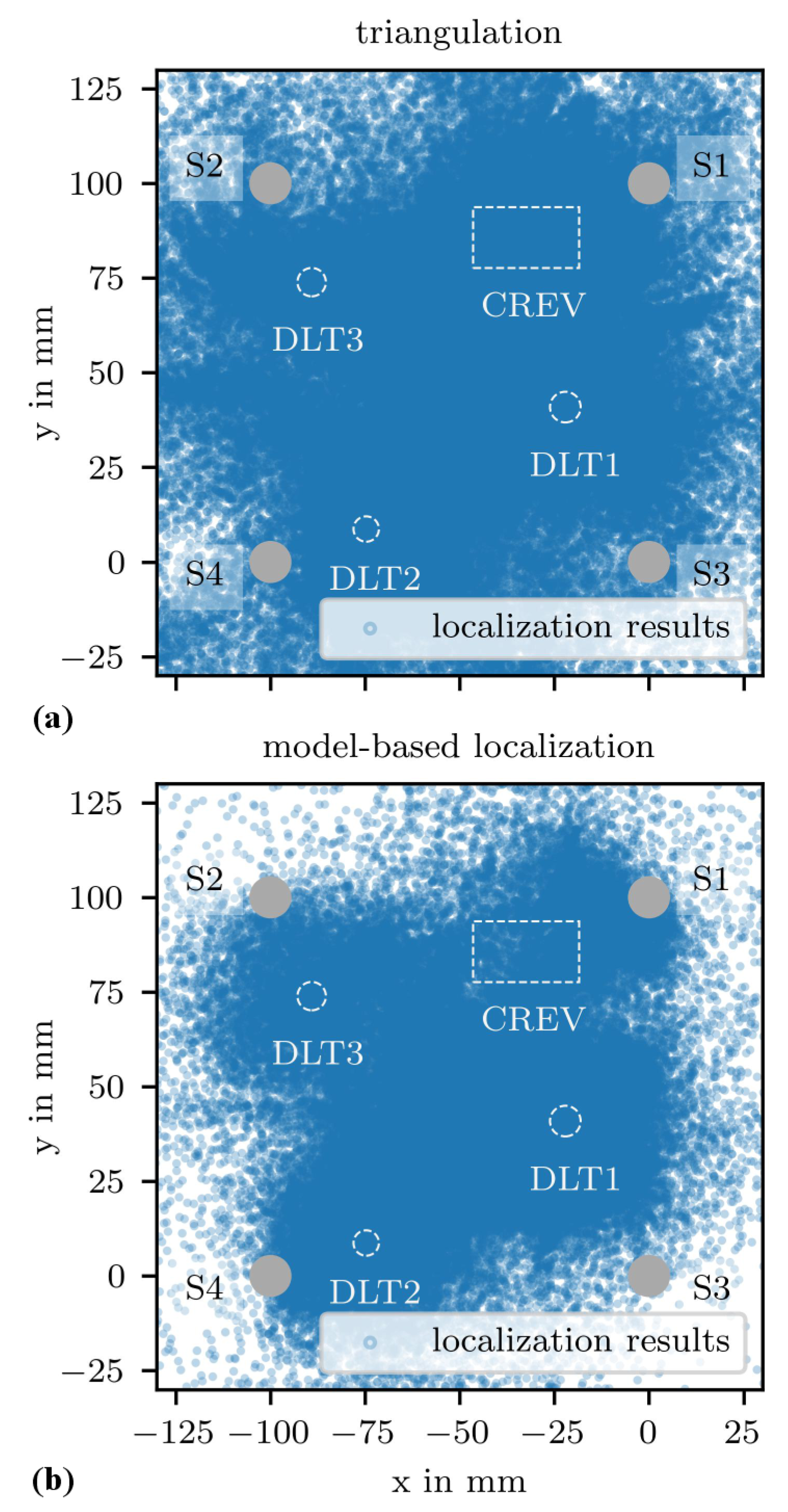

3.2. AE Source Localization Results

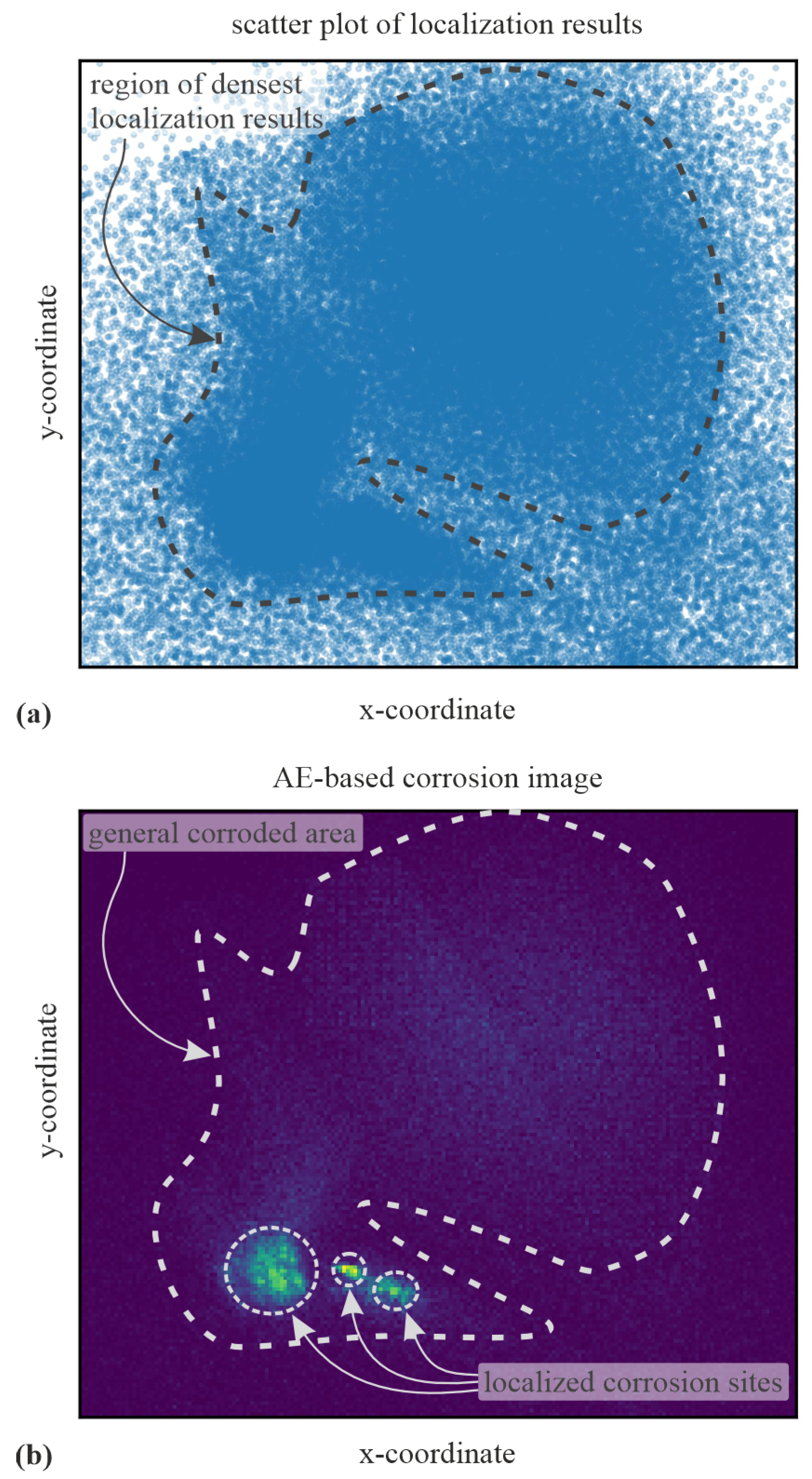

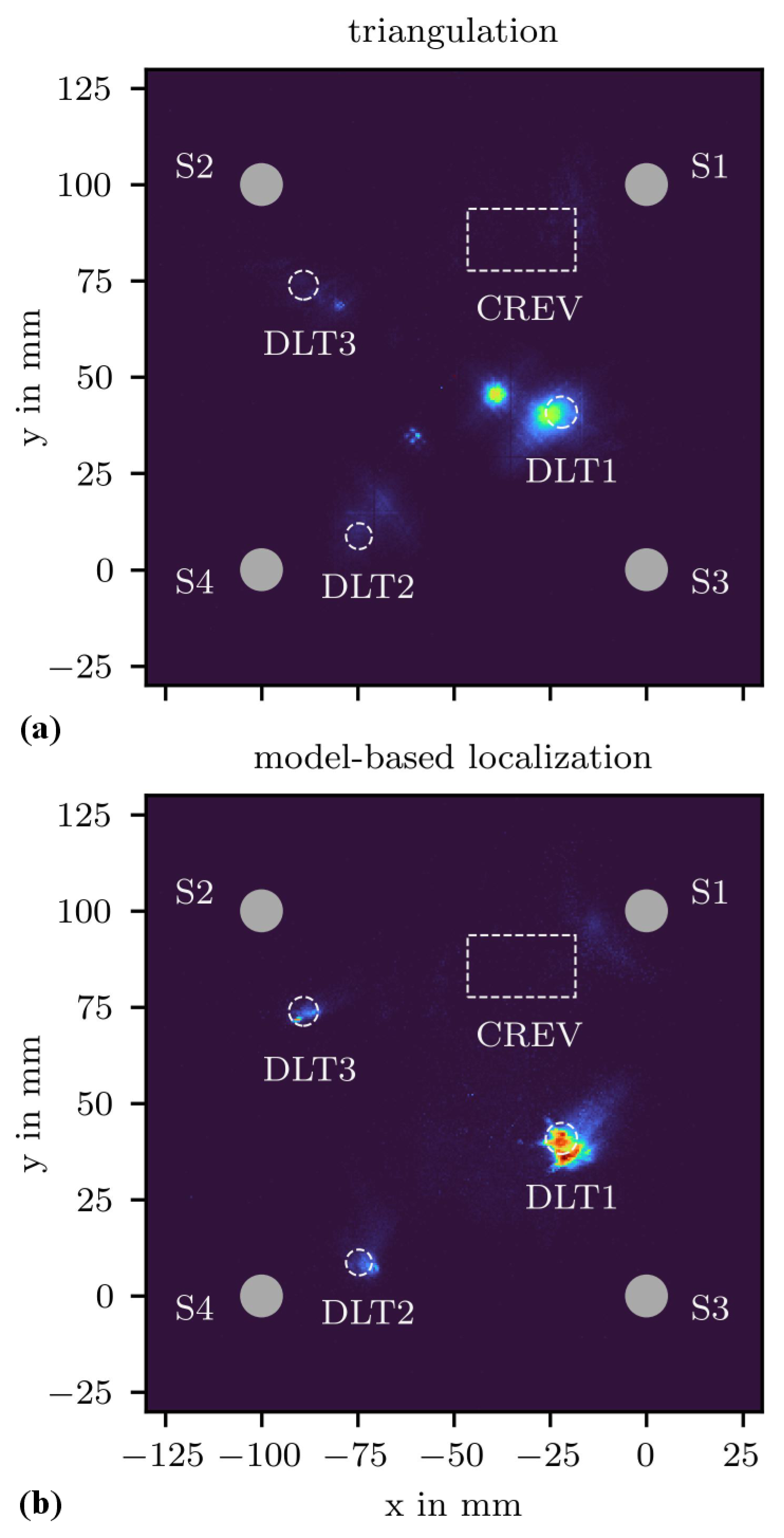

3.3. Corrosion State Imaging

3.4. Corrosion Evolution Imaging

4. Conclusions

References

- P. D. Mangalgiri, Corrosion issues in structural health monitoring of aircraft, ISSS Journal of Micro and Smart Systems 8 (1) (2019) 49–78. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Wright, P. Lu, J. Devkota, F. Lu, M. Ziomek-Moroz, P. R. Ohodnicki, Corrosion Sensors for Structural Health Monitoring of Oil and Natural Gas Infrastructure: A Review, Sensors 19 (18) (2019) 3964. [CrossRef]

- M. G. R. Sause, E. Jasiūnienė (Eds.), Structural Health Monitoring Damage Detection Systems for Aerospace, Springer Aerospace Technology, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-72192-3.

- M. Wevers, K. Lambrighs, Applications of Acoustic Emission for SHM: A Review, in: Encyclopedia of Structural Health Monitoring, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. Bellenger, H. Mazille, H. Idrissi, Use of acoustic emission technique for the early detection of aluminum alloys exfoliation corrosion, NDT & E International 35 (6) (2002) 385–392. [CrossRef]

- C. Abarkane, A. M. Florez-Tapia, J. Odriozola, A. Artetxe, M. Lekka, E. García-Lecina, H. J. Grande, J. M. Vega, Acoustic emission as a reliable technique for filiform corrosion monitoring on coated AA7075-T6: Tailored data processing, Corrosion Science 214 (2023) 110964. [CrossRef]

- L. Calabrese, E. Proverbio, A Review on the Applications of Acoustic Emission Technique in the Study of Stress Corrosion Cracking, Corrosion and Materials Degradation 2 (1) (2021) 1–30. [CrossRef]

- T. Erlinger, C. Kralovec, M. Schagerl, Monitoring of Atmospheric Corrosion of Aircraft Aluminum Alloy AA2024 by Acoustic Emission Measurements, Applied Sciences 13 (1) (2023) 370. [CrossRef]

- F. Ostermann, Anwendungstechnologie Aluminium, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Vargel, Corrosion of Aluminium, 2nd Edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. du Plessis, Studies on Atmospheric Corrosion Processes in AA2024, Ph.D. thesis, University of Birmingham (2015).https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/5642/5642.

- T. Erlinger, C. Kralovec, M. Schagerl, Acoustic emission-based structural health monitoring concept for corrosion of aluminum aircraft structures, e-Journal of Nondestructive Testing 28 (1) (2023). [CrossRef]

- T. Kundu, Acoustic source localization, Ultrasonics 54 (1) (2014) 25–38. [CrossRef]

- F. Hassan, A. K. B. Mahmood, N. Yahya, A. Saboor, M. Z. Abbas, Z. Khan, M. Rimsan, State-of-the-Art Review on the Acoustic Emission Source Localization Techniques, IEEE Access 9 (2021) 101246–101266. [CrossRef]

- C. U. Grosse, M. Ohtsu, D. G. Aggelis, T. Shiotani (Eds.), Acoustic Emission Testing: Basics for Research – Applications in Engineering, Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Kalafat, M. G. Sause, Acoustic emission source localization by artificial neural networks, Structural Health Monitoring 14 (6) (2015) 633–647. [CrossRef]

- T. Erlinger, C. Kralovec, C. Humer, M. Schagerl, Impact of Model Knowledge on Acoustic Emission Source Localization Accuracy, e-Journal of Nondestructive Testing 29 (2024). [CrossRef]

- M. Mandel, M. Fritzsche, S. Henschel, L. Krüger, Lamb wave-based corrosion source location on a plate of magnesium alloy WZ73 using the acoustic emission technique, Corrosion Communications 13 (2024) 60–67. [CrossRef]

- C. Jomdecha, A. Prateepasen, P. Kaewtrakulpong, Study on source location using an acoustic emission system for various corrosion types, NDT & E International 40 (8) (2007) 584–593. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Sheikh, K. Kamal, F. Rafique, S. Sabir, H. Zaheer, K. Khan, Corrosion detection and severity level prediction using acoustic emission and machine learning based approach, Ain Shams Engineering Journal 12 (4) (2021) 3891–3903. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, Z. Zhang, J. Tan, X. Wu, Quantitatively related acoustic emission signal with stress corrosion crack growth rate of sensitized 304 stainless steel in high-temperature water, Corrosion Science 157 (2019) 79–86. [CrossRef]

- C. Van Steen, L. Pahlavan, M. Wevers, E. Verstrynge, Localisation and characterisation of corrosion damage in reinforced concrete by means of acoustic emission and X-ray computed tomography, Construction and Building Materials 197 (2019) 21–29. [CrossRef]

- E. Vandecruys, C. Martens, C. Van Steen, G. Lombaert, E. Verstrynge, Corrosion level estimation in reinforced concrete beams by acoustic emission sensing and selective crack measurements, Structural Concrete n/a (n/a) (2024). [CrossRef]

- A. Zaki, H. K. Chai, D. G. Aggelis, N. Alver, Non-Destructive Evaluation for Corrosion Monitoring in Concrete: A Review and Capability of Acoustic Emission Technique, Sensors 15 (8) (2015) 19069–19101. [CrossRef]

- E. Verstrynge, C. Van Steen, E. Vandecruys, M. Wevers, Steel corrosion damage monitoring in reinforced concrete structures with the acoustic emission technique: A review, Construction and Building Materials 349 (2022) 128732. [CrossRef]

- K. Asamene, L. Hudson, M. Sundaresan, Influence of attenuation on acoustic emission signals in carbon fiber reinforced polymer panels, Ultrasonics 59 (2015) 86–93. [CrossRef]

- K. Ono, Review on Structural Health Evaluation with Acoustic Emission, Applied Sciences 8 (6) (2018) 958. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Aggelis, M. G. R. Sause, P. Packo, R. Pullin, S. Grigg, T. Kek, Y.-K. Lai, Acoustic Emission, in: M. G. R. Sause, E. Jasiūnienė (Eds.), Structural Health Monitoring Damage Detection Systems for Aerospace, Springer Aerospace Technology, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021, pp. 175–217. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-72192-3_7.

- M. A. Hamstad, On Lamb Modes As a Function Of Acoustic Emission Source Rise Time, Journal of Acoustic Emission (28) (2010) 41–58.

- J. Jiao, C. He, B. Wu, R. Fei, X. Wang, Application of wavelet transform on modal acoustic emission source location in thin plates with one sensor, International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping 81 (5) (2004) 427–431. [CrossRef]

- F. Ciampa, M. Meo, Acoustic emission source localization and velocity determination of the fundamental mode A0 using wavelet analysis and a Newton-based optimization technique, Smart Materials and Structures 19 (4) (2010) 045027. [CrossRef]

- E. Schindelholz, R. G. Kelly, Wetting phenomena and time of wetness in atmospheric corrosion: A review, Corrosion Reviews 30 (5-6) (2012) 135–170. [CrossRef]

- J. Muradeli, Ssqueezepy, GitHub repository, https://github.com/OverLordGoldDragon/ssqueezepy/ (2020). [CrossRef]

- F. Rotea, Lambwaves, GitHub repository, https://github.com/franciscorotea/Lamb-Wave-Dispersion (2020).

- J. H. Kurz, C. U. Grosse, H.-W. Reinhardt, Strategies for reliable automatic onset time picking of acoustic emissions and of ultrasound signals in concrete, Ultrasonics 43 (7) (2005) 538–546. [CrossRef]

- Matplotlib, Matplotlib.colors.SymLogNorm (2025). https://matplotlib.org/stable/api/_as_gen/matplotlib. colors.SymLogNorm.html (accessed: 22 April 2025).

- V. Bonamigo Moreira, A. Krummenauer, J. Zoppas Ferreira, H. M. Veit, E. Armelin, A. Meneguzzi, "Computational image analysis as an alternative tool for the evaluation of corrosion in salt spray test ", Studia Universitatis, Babes-Bolyai Chemia 65 (3) (2020) 45–61. [CrossRef]

- I. Ivasenko, V. Chervatyuk, Detection of Rust Defects of Protective Coatings Based on HSV Color Model, in: 2019 IEEE 2nd Ukraine Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (UKRCON), 2019, pp. 1143–1146. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).