1. Introduction

Heavy metal pollution poses a global environmental concern due to its severe toxicity [

1,

2], long-term persistence, and bioaccumulation in food chains [

3,

4,

5]. Harmful heavy metals (HHM) are continuously introduced into the environment [

6] through natural and anthropogenic sources [

7,

8]. In estuarine waters, the presence of HHM is generally observed in two distinct phases: dissolved in the water column and particulate adsorbed on the sediments. The partitioning of HHM between these phases depends on the physical and chemical characteristics of suspended particles [

9,

10], in conjunction with environmental conditions such as salinity, pH, and dissolved organic matter [

10].

Upon entering surface waters, HHM are transported by rivers through wash load transport and eventually accumulate in marine sediments. Hydro-sedimentary processes such as desorption [

11], resuspension and dredging can release these contaminants back into the overlying water column [

12], affecting water quality, the marine environment, and human health. Although HHM adsorption initially occurs near areas with significant anthropogenic activities, this study emphasizes the downstream consequences, particularly focusing on sediment contamination.

Various researchers rely on predicting interactions between water and sediments as a critical method for understanding HHM pollution [

5,

13,

14,

15]. Mathematical models have become powerful tools to address complex research questions related to coastal environments offering reliable, cost-effective, and time-saving approaches [

16].

Specifically, reaction-transport models, as described by Boudreau [

17], Lynch and Officer [

18], and Nicolis [

19], have been pivotal in advancing sediment diagenesis and biogeochemical modelling, integrating key processes such as molecular diffusion, advection, and chemical reactions. These frameworks form the theoretical foundation of this study, focused on the vertical distribution and temporal evolution of HHM in sediments.

Previous studies, such as, Wu et al. [

10], developed a two-dimensional (2D) transport model, later integrated into a one-dimensional (1D) framework to simulate the movement of dissolved and particulate HHM along estuaries. However, these models did not explicitly address the accumulation of HHM contaminants or their subsequent phase evolution within the substrate, a significant gap in understanding the long-term impacts and interactions of HHM with sediment dynamics.

This study proposes a novel approach that integrates both dissolved and particulate HHM phases. Four critical hydrodynamic processes are quantified and modeled to evaluate their influence on HHM dynamics. This model, in accordance with empirical data, assumes that the dissolved-phase concentration (

) is considerably lower than the particulate-phase concentration (

) in the water column (

<< ). This assumption aligns with the concept of the infinite dilution diffusion coefficient [

17], thereby providing a more realistic representation of HHM in sediments.

To demonstrate the model’s applicability, simulations were referenced against estuarine conditions in the Cartagena Bay, Colombia (CB), a system subject to intense sedimentation and HHM inputs. Results obtained through this model align closely with empirical observations, reinforcing its validity.

A novel 1D mathematical model is developed to investigate HHM dynamics in estuarine sediments and to elucidate the processes HHM governing background concentrations (

). These concentrations serve as critical indicators for identifying anthropogenic inputs [

20] and facilitate the formulation of effective management and remediation strategies [

7,

21]. This research represents the first attempt to establish

of HHM in Colombia, highlighting its significance in addressing local and regional environmental concerns.

The model is applicable beyond the specific conditions of the Colombian coastline and could be effectively extended to various aquatic systems, including rivers, estuaries, and lakes worldwide affected by sediment contamination. Model outputs, including dynamic profiles illustrating the temporal drift of are presented and critically discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cartagena Bay: A Reference System for Estuarine Conditions

CB is a semi-enclosed estuarine system on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, (10°16′–10°26′ N, 75°30′–75°35′ W), with an average depth of 16 m, a maximum depth of 32 m, and a surface area of 84 km² [

22]. The bay receives large amounts of sediments [

23], nutrients, wastewater runoff [

24], and contaminants from the Dique Channel [

25,

26], an artificial structure connected to the extensive Magdalena River basin (260,000-km²) [

26,

27].

The Magdalena River transports a sediment flux of 184 Mt yr⁻¹ and delivers the highest freshwater discharge (6 496 m³ s⁻¹) and sediment load (144 Mt yr⁻¹) to the Caribbean [

26,

27]. Seasonal rainfall from the Magdalena River, where the Dique Channel diverges, strongly influence the hydrology and sediment quality of CB [

28]. Due to wash load transport, HHM adsorption does not occur in CB but rather in distant sources before HHM are transported downstream. This explains the HHM accumulation in precipitated sediments.

2.2. Mathematical Model

2.2.1. Definition of the Physical Problem

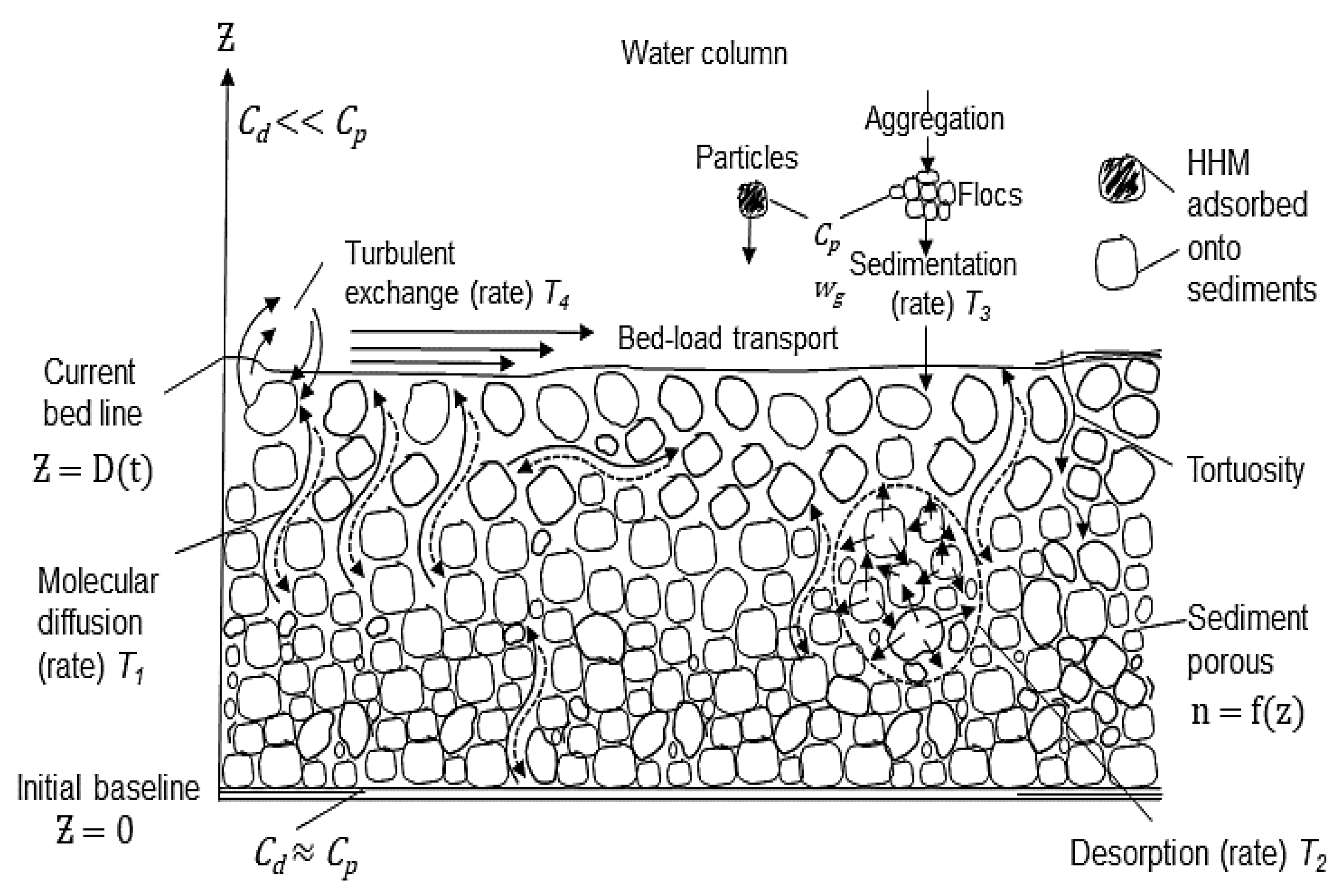

This research considers wash load transport [

29] of fine cohesive sediments (silt and clay) loaded with HHM in particulate form. The primary source of HHM is the rapid upstream industrialization in the Magdalena River. Particles are deposited at the bottom in the form of flocs. In the porous medium of precipitated sediments, desorption continues but at a lower rate than that during transport in the water column.

In the water column, HHM exist in colloidal, particulate, and dissolved phases. The concentration of HHM in dissolved form () is generally lower than that in particulate form (). Hereafter, we assume that concentrations are multiplied by the constant Kd, which represents the equilibrium distribution coefficient. In the sediment substrate, these concentrations are also assumed to reach equilibrium due to limitations in molecular diffusion, which is partially restricted by porosity (n) and tortuosity ( Lower porosity and higher tortuosity restrict molecular diffusion, reducing HHM exchange with overlying waters and consequently promoting high accumulation and persistence within the sediment layer.

Tortuosity quantifies the complexity of pore pathways through which water and dissolved substances, such as HHM, move within sediment layers [

30]. Porosity, defined as the ratio of pore volume to total sediment volume [

17], also plays a critical role in transport dynamics. Lower porosity implies fewer and smaller pores, restricting mobility and facilitating contaminant accumulation. As sediment compacts over time, porosity typically decreases with depth (

z), becoming a time-dependent function. This leads to a gradual increase in substrate thickness in the absence of resuspension.

The desorption rate

, reflects the release of HHM from

to

and depends on the grain diameter of sediments (

), their porosity (

n), salinity (

S), and pH. The porosity and tortuosity together influence molecular diffusion, calculated in the model using the Schmidt number (

Sc), a dimensionless parameter to characterizes the relationship between the molecular viscosity of water and the diffusion of substances [

31].

A 1D vertical model was formulated, neglecting the horizontal dispersion of HHM, with the vertical axis directed upward from z = 0 (the reference level is assumed to be the starting point of sedimentation, as shown in

Figure 1). The 1D model can be considered a sufficient approximation, considering that (a) the relationship between the vertical scale of the sediment layer and its horizontal extent along an estuary or river is small, and (b) exchange processes in the substrate in the vertical direction are much faster than the horizontal dynamics.

The domain is defined as

, where D = sediment thickness as a function of time (

t). At the initial time,

D was set as D(t = 0) = 0. To avoid singularities when solving the differential equations of the model, we assumed that

under the absence of resuspension. The dynamics of the layer D(

t) are expressed as follows:

where

is the settling velocity of sediments due to gravity, given by the Stokes formula (

), and

,

, and

are the volumetric and mass concentrations of suspended sediments, and their density, respectively. Within the bottom substrate, the molecular diffusion flux of the dissolved fraction

is defined as:

where

is the kinematic molecular viscosity of water (Constant) and

defines the inverse Schmidt number (

) [

31], which generally depends on time and substrate level or porosity

n.

To determine the desorption rate

, at least three timescales must be considered: 1) the molecular diffusion rate (

T1) of HHM, 2) the desorption rate (

T2), and 3) the sediment deposition rate (

T3) at the bottom, as follows:

The parameters of the model, particularly sedimentation and desorption rates were calibrated within observed HHM concentrations reported in empirical data from CB [

24,

25,

27,

32]. The resulting optimization problem was numerically solved using FORTRAN program, with an implicit time-stepping scheme to ensure numerical stability under varying sediment thicknesses and boundary conditions.

Table 1.

State variables and parameters used in this study.

Table 1.

State variables and parameters used in this study.

| Parameter |

Description |

Unit |

Value |

Reference |

|

HHM Background concentration |

g L⁻¹, mg kg⁻¹ (dw)* |

see Table 2

|

calculated |

|

Drag coefficient |

/ |

2 × 10⁻³ |

[33] |

|

Dissolved-phase HHM concentration |

g L⁻¹, mg kg⁻¹ (dw)* |

/ |

calculated |

| Cm |

Suspended-sediment mass concentration |

g L⁻¹ |

/ |

[34] |

|

Particulate-phase HHM concentration |

g L⁻¹, mg kg⁻¹ (dw)* |

/ |

calculated |

|

Initial particulate HHM at precipitation |

g L⁻¹ |

/ |

assumed |

|

Suspended-sediment volumetric concentration |

/ |

10⁻⁴–10⁻⁵ |

assumed |

| d50 |

Median grain diameter of sediment |

m |

/ |

measured |

| D |

Sediment thickness |

m |

0–1.6** |

calculated |

| F |

Porosity–tortuosity factor |

/ |

/ |

calculated |

| HHM |

Harmful heavy metals |

g L⁻¹, mg kg⁻¹ (dw)* |

varies |

measured |

|

Coefficient of equilibrium distribution |

/ |

/ |

assumed |

| m |

Exponent in the relationship of Sc and n

|

/ |

/ |

literature |

| N |

Number of computational nodes |

/ |

100 |

assumed |

| n |

Porosity |

/ |

0.4 |

[35] |

| Q |

Molecular diffusion flux |

kg m⁻² s⁻¹ |

varies |

calculated |

| S |

Salinity |

/ |

0.06-35.7 |

assumed |

|

Schmidt number |

/ |

10–100 |

[6] |

| t |

Time |

s |

0–8.64 × 10⁸ s |

assumed |

| T1 |

Molecular diffusion rate |

yr |

0.3–3 |

calculated |

| T2 |

Desorption rate |

yr |

3.15 (for γ=5×10⁻⁸) |

calculated |

| T3 |

Sediment rate |

yr |

>31 |

calculated |

| T4 |

Turbulent exchange rate |

yr |

/ |

calculated |

|

Friction (dynamic) velocity |

m s⁻¹ |

0–0.01 |

assumed |

|

Settling velocity of sediments due to gravity |

m s⁻¹ |

10⁻⁵ |

assumed |

| y |

Dimensionless vertical coordinate |

/ |

0–1 |

calculated |

|

Vertical level within the substrate |

m |

0–1.6 |

calculated |

|

Roughness parameter |

m |

/ |

literature |

|

Inverse Schmidt number |

/ |

0.01–0.1 |

[31] |

| γ |

Desorption coefficient |

s⁻¹ |

5×10⁻⁸–1×10⁻⁹ |

[36] |

|

Vertical grid size in dimensionless coordinates |

/ |

1/(N−1) |

calculated |

| θ |

Tortuosity |

/ |

/ |

[30] |

|

Karman constant |

/ |

0.41 |

literature |

| ν |

Kinematic molecular viscosity of water |

m² s⁻¹ |

10⁻⁶ |

constant |

|

Sediment–particle density |

kg m⁻³ |

2 650 |

[33] |

|

Molecular diffusion coefficient (water only) |

m² s⁻¹ |

/ |

[17] |

|

Molecular diffusion coefficients (with sediments) |

m² s⁻¹ |

/ |

calculated |

2.2.2. Governing equations and boundary conditions

The mathematical formulation of the problem is expressed in Equation (1). The governing equations for

and

of HHM are defined clearly below (Equations (6)–(7)), including mass balance constraints and desorption processes:

where

is the HHM concentration in sediment particles, with the concentration

at the time of precipitation [

34]; and

is the Dirac delta function. This function in Equation (6) models a localized source of HHM at depth z = D, representing the input of

concentrations at the top of the sediment layer. Details on the Schmidt number in Equation (7) can be found in

Appendix C.

Equations (6) and (7) require initial conditions

and the following boundary conditions:

In equation (8),

A is a constant defined in

Appendix B, based on the fact that in the water column,

due to diffusion in open water systems. As stated by the no-flux condition in Equation (9), an asymptotic equilibrium is assumed at z = 0 between

and

, with values equal to the

to be defined in this study.

This boundary condition assumes equilibrium at lower sediment layers (z = 0), reaching a balance due to decreased porosity and restricted molecular diffusion over time. In equation (9), the molecular flux of at z = 0 is assumed to be zero. The boundary conditions at z = 0 and z = D(t) ensure the mass balance of HHM within the sediment, accurately representing fluxes and the conservation of mass. At z = D(t), the boundary condition models the exchange between the sediment and the overlying water column.

2.2.3. Numerical solution under variable boundary conditions

The equations (6)–(9), with their respective initial conditions of

, have a variable boundary at an initial thickness of D(t = 0) = 0. The vertical coordinate (z) was transformed into a non-dimensional coordinate, following Yao et al. [

13], to imptove numerical solution robustness. The system herein was reformulated using a new variable:

This becomes

; j = 1, …, N;

, where

N is the number of vertical computational nodes. Thus, combining Equations (6) and (7) with Equation (1), we obtain:

These equations were then discretized using an implicit time scheme, ensuring numerical stability regardless of the sediment thickness, D. The first derivatives concerning y were then represented using an "upward" scheme of . The solution was obtained using the Thomas factorization algorithm.

3. Results

3.1. Estimation of Molecular Diffusion (T1), Desorption (T2), and Sedimentation (T3)

To estimate the timescales (

T1,

T2,

T3) given by Equations (3)–(5), a characteristic sediment thickness (

= 1 m), molecular viscosity (v =

m² s⁻¹), and Schmidt number (Sc = 100) were adopted [

6]. With these parameters,

T1 was estimated to be 3 years. For Sc = 10,

T1 was approximately 115 days. According to Liu et al. [

37], the values of

vary between 10

–8 and 10

–9 s⁻¹. For

5 × 10⁻⁸ s⁻¹, the timescale of

T2 was 3.15 years.

Finally, assuming that the volumetric concentration was between 10–4 and 10–5 and the settling velocity due to gravity was 10–5 m/s, the value of T3 was greater than 31 years. Therefore, T3 >> max (T1, T2) T3 has the slowest timescale, while the other two timescales were similar to each other.

3.2. In Addition to Previously Defined Timescales (T1-T3), a Fourth Timescale (T4) Representing Turbulent Water-Column Exchange Of Dissolved HHM at the Sediment-Water Interface was Determined. Resuspension Was Not Considered, as Particulate-Bound HHM do not Significantly Participate in this Exchange. Numerical Experiments

The sediment density (

was set at 2 650 kg m⁻³, with porosity (

n) fixed at 0.4. A drag coefficient (

) of 2 × 10

–3 [

33], and an initial dynamic velocity of 0.01 m s⁻¹ were applied. Numerical experiments were conducted over 28 years, using a daily time step (1 d).

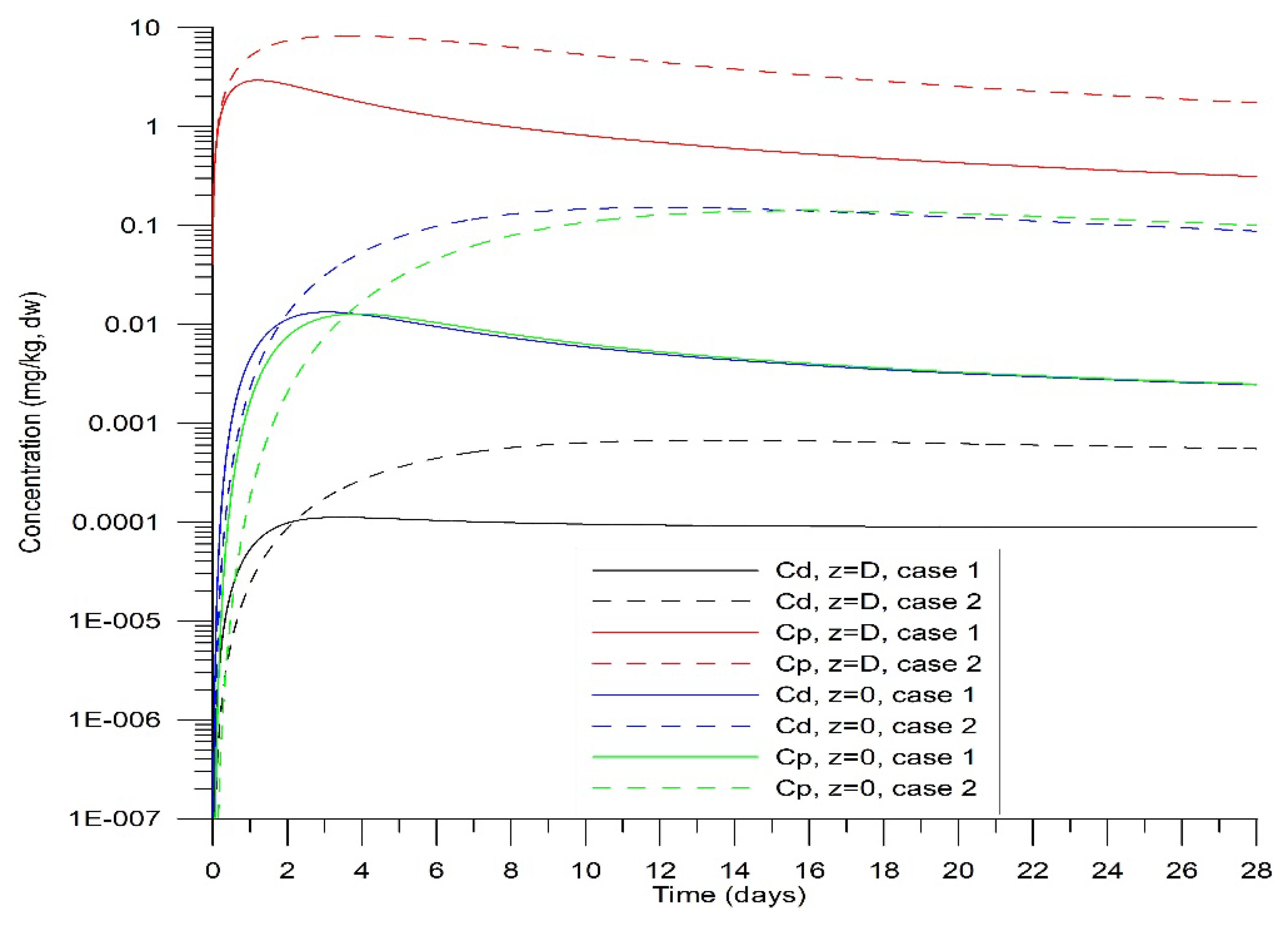

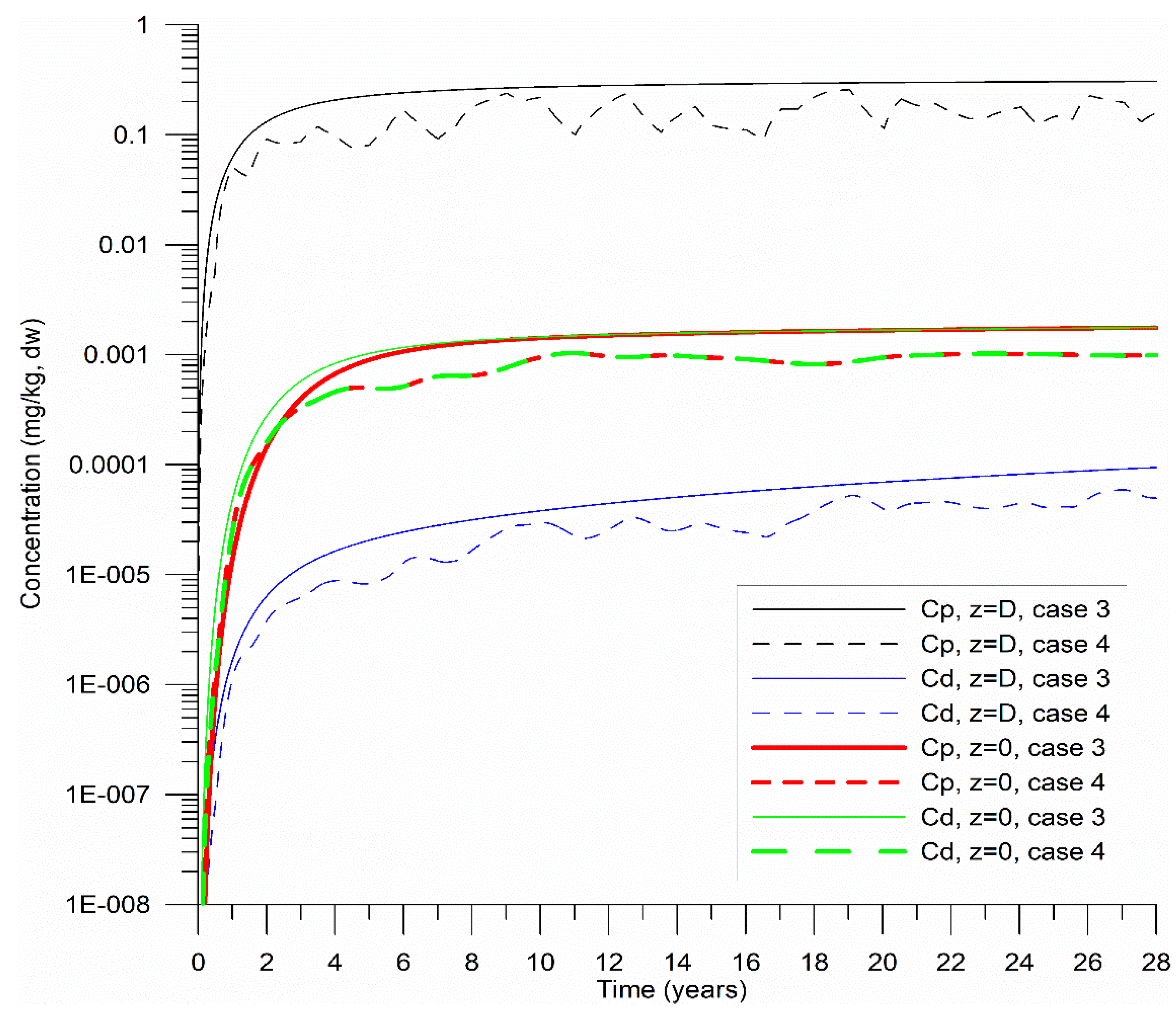

Figure 2 illustrates the temporal evolution of

and

from the beginning of precipitation on both the surface and base when the desorption coefficient

is varied. Sedimentation was assumed to continue uniformly over the 28-year simulation at constant rates, with fixed HHM concentrations in the precipitated sediments. In

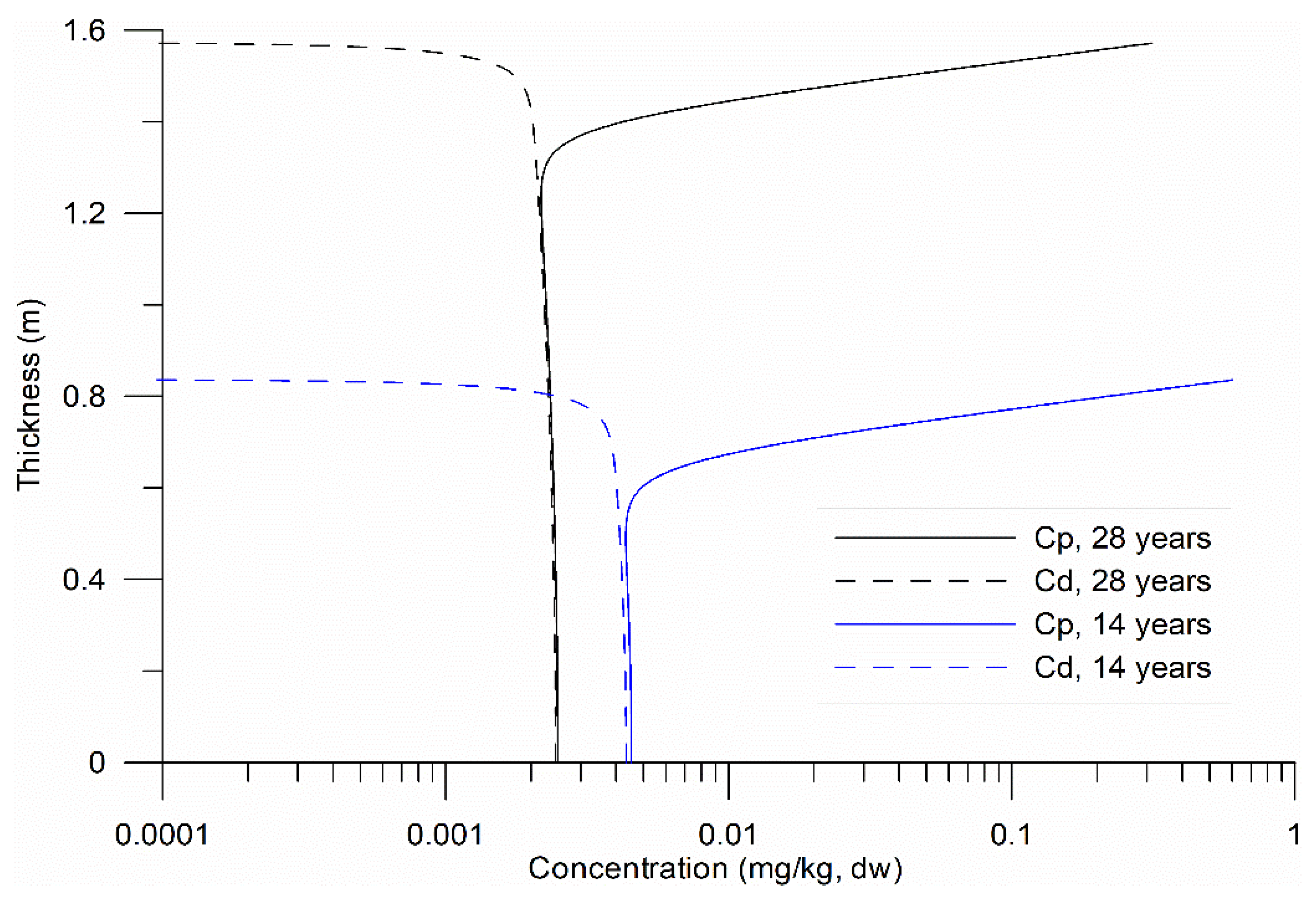

Figure 3, profiles of HHM concentrations in sediments are presented at both the midpoint and the end of the numerical experiments.

Over 28 years, the sediment layer grew to 1.6 m, which aligned well with data from CB and served as a reference for this study. Following an initial transient period (

Figure 2), the

and

stabilized. The desorption rate was slower, corresponding to 6.3 years on the timescale of this process, compared to the reference value of 3.15 years.

The vertical profiles exhibited an exponential variation in the upper layer of the substrate (

Figure 3), over 30–40 cm, followed by a uniform distribution. The variation was attributed to the vertical molecular diffusion of HHM and their loss, particularly in

, due to turbulent exchange with the water column at the bottom. The uniform distribution in the lower sublayer indicates equilibrium between the two phases; however, this equilibrium was not constant (

Figure 3). Equilibrium stability between

and

is crucial for ecological risk assessments, as it governs HHM bioavailability and potential toxicity in benthic ecosystems.

5. Discussion

5.1. Temporal Evolution of Background Concentrations Estimated by the Model

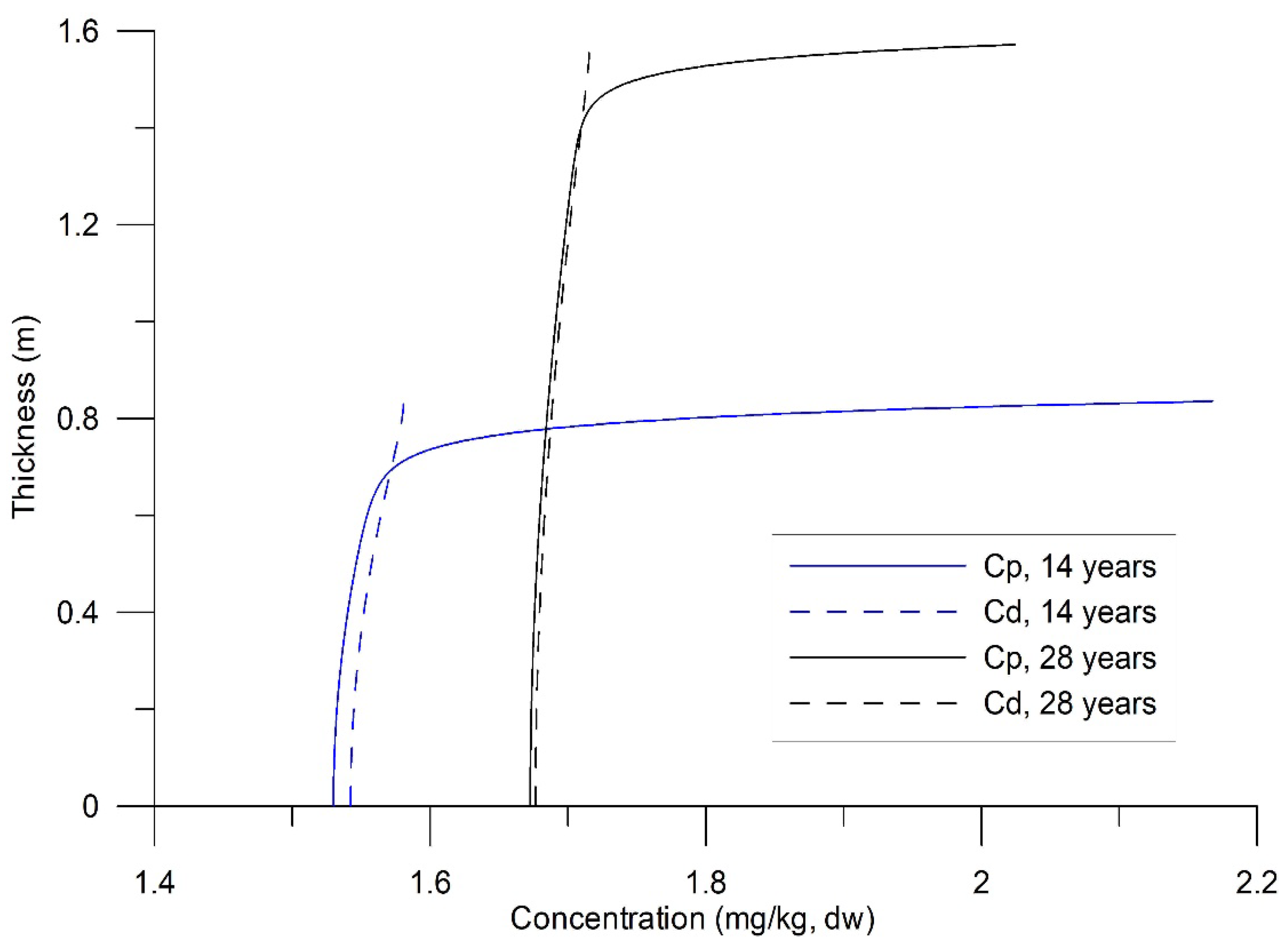

A drift value, tentatively called the background

, was observed, characterized by a gradual decrease over time. This decrease is attributable to continuous slow molecular diffusion within the non-zero sediment porosity, transporting HHM towards the sediment-water interface. Subsequent experiments were conducted by minimizing the turbulent exchange of the dissolved phase with the water column above the bed. This occurs when

(

Figure 4). A nearly uniform distribution of

in the vertical direction was observed, along with the input of

at the bottom surface. The total concentrations of HHM in the sediments were the sum of

and

/

, and in the laboratory, a single value is defined: "HHM concentrations in sediments."

For Case 1,

was set to 5 × 10⁻⁸ s⁻¹, which suggested a relatively faster desorption rate compared to Case 2 (

10⁻⁸ s⁻¹). Two additional cases (Cases 3 and 4) were simulated (

Figure 5). In Case 3, the initial particulate concentration

increased linearly from 0 to 2.4 mg kg⁻¹ over 28 years, reflecting observed trends in CB associated with increased HHM loading from a distant source, the Magdalena River. Case 4 was similar to Case 3, but with a variable sediment input varied between 55 and 250 m³ s⁻¹ to replicate the Dique Channel’s seasonal flow, using annually periodic white-noise perturbations (stochastic values 0–1).

The cases in

Figure 5 were compared to Case 1 in

Figure 2, where HHM in sediments accumulated more slowly. Notably, when HHM loading gradually increased (Case 3), the concentrations at the sediment base (z = 0) consistently reached equilibrium (

=

=

). Conversely, seasonal variations in sediment load from the Dique Channel (Case 4) did not significantly alter the equilibrium

value. These findings imply that

remain stable despite short-term fluctuations, highlighting their value as robust indicators for long-term ecological risk assessment.

Table 2.

Model-derived Hg background concentrations () at boundary (z = 0) under different simulation cases.

Table 2.

Model-derived Hg background concentrations () at boundary (z = 0) under different simulation cases.

| Case |

Description |

mg kg⁻¹ (dw) |

Observation |

| 1 |

γ = 5 × 10⁻⁸ 1/s |

1.4 – 1.7 |

Long-term equilibrium at z = 0 |

| 2 |

γ = 10⁻⁸ 1/s |

1.0 – 1.2 |

Slower equilibrium from low γ |

| 3 |

increasing over 28 yr |

2.0 – 2.4 |

Closest to observed CB field data |

| 4 |

Variable sediment input* |

2.0 – 2.2 |

Dynamic but consistent at z = 0 |

| - |

Average Hg (model) |

0.2 ± 1.7 |

Variability across all cases |

5.1. Dimensionless Analysis and HHM Dynamics

To perform an analysis of the systems in Equations (1) and (6)–(9), dimensionless variables were introduced, as follows:

; ; ; ; ; ; ; ;

; ; ; The “~” symbol implies a dimensionless variable.

The systems (6 and 7) and their respective conditions (8 and 9) are described in a dimensionless form as follows:

Adding Systems (6’) and (7’,) and using conditions (8’) and (9’), the results are:

Applying Leibniz's rule and reformulating Equation (1) in terms of “fast” time

, we obtain:

The temporal variation in the total HHM concentration of sediments over the entire extent of its layers can be defined by the following equation:

The first term on the right-hand side of Equation (13) represents the input of HHM in particulate form into the sediment column, while the second term accounts for their loss through exchange with the overlying water in the dissolved phase. The final term corresponds to the increase in the total HHM concentration due to changes in substrate thickness and its redistribution in the column. This term was considered less relevant when the T3 scale represented a slow time relative to T1 and T2. Within the same body of water, as exemplified by CB, the T3 scale is spatially variable.

If for the “fast” time in System (1’), then systems (6’)–(9’) are represented as parabolic equations whose asymptotes in time are . Steady-state conditions are possible only if the particle sedimentation process stops.

For , considering condition (9') at a given level, the molecular flow is equal to zero throughout the substrate.

In this case, (background concentration). The only reason this did not occur throughout the entire sediment column is the permanent entry of HHM, owing to their precipitation on particles at the bottom and the exchange of the diluted phase with the water column at the same vertical level.

The simulated sedimentation rates ranged from 0.5 m per 25 years (low deposition) to 10 m per 25 years (at the river mouth). Therefore, the 1D model should be applied at each calculation node of a 3D hydrodynamic mesh, with local scales adjusted accordingly. Considering the timescale variation in the main processes, the desorption rate, the average speed of sediment settling by gravity, and the molecular viscosity of water were fixed. The thickness of the sediment layer and its porosity (through the Schmidt number) varied within reasonable limits, characterizing CB as an example of an estuary. The resulting values of the dimensionless parameters for systems (6’) to (9’) were: a = 10–3 to 103; = 102 to 104; /= 0.25 (10–1–10–5) and = 10–2 to 102.

Under these conditions, Equations (6’) and (7’) can present multiple scenarios of HHM dynamics because the ratios of scale

and

change four to six orders of magnitude. In the case where the parameter a =

, the scales become inverted. Regarding condition (8’), the relationship

/

<< 1 implied an abrupt gradient

, which was observed in

Figure 3 at the interface between sediments and water. This detail was not observed in the measurements of HHM in sediments because the laboratories analyze the total concentrations, where

/

+

, and the

concentration predominates in the samples.

5.1. Model Assumptions, Limitations, and Ecological Implications

The proposed 1D model was developed under the assumptions of continuous sedimentation without bottom erosion events. Technically, erosion could be easily included in the model; however, it may be difficult to control over extended periods of sediment dynamics. Changes in the porosity and tortuosity were also considered, which influence HHM transport and accumulation. These mechanisms may require a rheological model. Since the model operated under the assumption that the muddy substrate was not in motion, no assumption of the fluid type or the Newtonian fluid approximation is required.

This modeling approach adressess a critical gap in the representation of sediment processes, particularly the understanding of of HHM in estuarine sediments by integrating transport and reaction processes with site-specific hydro-sedimentary influences which are often simplified or omitted in traditional frameworks. The relevance of lies in its strong association with toxicological thresholds, bioavailability, and long-term ecological risks related to HHM pollution. Although a 1D framework offers notable advantages in computational efficiency and vertical resolution, it limits horizontal transport and spatial interactions across estuarine gradients. Future initiatives could benefit from integrating diagenetic and hydrodynamic models to support evidence-based environmental management for preserving estuarine and coastal ecosystems.

6. Conclusions

Under physically valid assumptions, a novel one-dimensional mathematical model was developed to simulate HHHM dynamics in estuarine sediments, with broad applicability to water bodies influenced by HHM-contamination. This numerical framework advances prior approaches by integrating coupled transport-reaction processes while dynamically accounting for porosity and tortuosity. Unlike conventional models, this approach includes molecular diffusion (T1), desorption (T2), sedimentation (T3), and water-turbulence exchange (T4) as a distinct method to estimate HHM . A notable innovation is the separation of and , reaching an asymptotic equilibrium ( = = ) at the sediment base (z = 0). This mathematical formulation has not been previously reported in existing sediment models.

The for Hg in CB ranged from 1.0 to 2.4 mg kg⁻¹ dw, providing a valuable reference for future ecological risk assessments, pollution indexing, and numerical model calibration in estuarine sediments. of Hg

were characterized by very slow desorption. Particularly, values did not remain constant but exhibited a drift, influenced by limited exchange with upper layers and overlying water. These findings may improve ecological risk assessment, environmental monitoring, and policy formulation to mitigate HHM impacts in CB and similar contaminated ecosystems.

Spatial and temporal variability in arise from local sediment dynamics, precisely variations in precipitation rates, highlighting the need for zone-specific assessments within the same water body. Consequently, the 1D model can be applied to each node of the general hydrodynamic model of the basin.

The observed drift in

values demonstrate that profiling sediment layers dated with the 14C do not necessary reflect historical in-situ concentrations, as reported by Fukue et al. [

38]. This issue draws attention and stimulates future research using inverse models to restore HHM ancient profiles from in-situ measurements.

Future works will focus on integrating the 1D model into a three-dimensional hydrodynamic framework to continuously simulate the long-term fate of sediments and HHM, to compare the model’s stratification predictions to in-situ measurements of the vertical substrate. Such advancements could significantly aid in developing more effective management strategies to mitigate HHM pollution in coastal marine environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W. Tatiana Gonzalez Cano, Serguei Lonin and Kyoungrean Kim; Data curation, W. Tatiana Gonzalez Cano; Formal analysis, W. Tatiana Gonzalez Cano; Funding acquisition, Kyoungrean Kim; Investigation, W. Tatiana Gonzalez Cano, Serguei Lonin and Kyoungrean Kim; Methodology, W. Tatiana Gonzalez Cano, Serguei Lonin and Kyoungrean Kim; Project administration, Kyoungrean Kim; Resources, Serguei Lonin and Kyoungrean Kim; Software, Serguei Lonin; Supervision, Kyoungrean Kim; Validation, Serguei Lonin and Kyoungrean Kim; Visualization, Serguei Lonin; Writing – original draft, W. Tatiana Gonzalez Cano and Serguei Lonin; Writing – review & editing, Serguei Lonin and Kyoungrean Kim. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology, Republic of Korea, grant number PEA0301, and by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Republic of Korea, grant number KIMST-20220027. The authors gratefully acknowledge this support.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank everyone who was related to this research and the anonymous reviewers, whose comments led to the enhancement of the final version of this manuscript. Graphical abstract created in

https://BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Without the source term and molecular diffusion in a closed system, Equations (6) and (7) can be expressed as follows:

This represents the desorption from the particulate to the dissolved form of the HHM, with .

Assuming the initial conditions

and

, the respective analytical solution of the system (Equations (A1) and (A2)) becomes:

until it reaches an equilibrium, where

for

. The characteristic scale of this process, given in Equation (4), according to Equation (A3) is

Appendix B

To specify the boundary conditions for Equation (7) at the bottom surface, a flux equilibrium was established for the dissolved components of the HHM:

Here, the first and second terms on the left-hand side represent the turbulent and molecular fluxes of the HHM with concentrations in the water, respectively. The term on the right-hand side is the molecular diffusion flux of the substance in the sediments.

The sum of the turbulent and molecular fluxes was constant in a relatively thick layer, known as the near-surface bulk layer or “layer of constant fluxes.” This could be parameterized based on the K-theory of turbulence by defining the flux

q within the logarithmic profile of the substance:

where

= Karman constant (

;

is the friction (dynamic) velocity in the near- surface layer;

is the roughness parameter. In this case,

z extends from the bottom surface

upwards and is fixed with a reference value

of concentrations.

Introducing the drag coefficient

and assuming that the concentration in water is

in Equation (B.2), and based

, Equation (B1) gives:

which is Equation (8) when A =

The fact that

in the water column was justified under the assumption that the volumetric sediment concentrations in the water were less than 10

–4. In an extreme hypothetical scenario, where equilibrium is reached between the HHM in the water column, encompassing both particulate and dissolved phases, the concentration

represents no more than 0.01 % of the particulate concentration

.

Appendix C

Generally, the molecular Schmidt number,

Sc, characterizes the relationship between the molecular viscosity of water and the molecular diffusion of substances; it measures how fast the “diffusion of momentum” occurs relative to other fluid properties. Substances with a water temperature of approximately

Sc = 10 can increase by one or two orders of magnitude [

31].

The Schmidt number is associated with the porosity and tortuosity of a fluid composed of liquid and bottom sediments. Porosity and tortuosity are considered to play major roles in the increase of this number. In the proposed study by Maerki et al. [

39] the molecular flow (2) was identified as follows:

where

n represents porosity,

characterizes tortuosity, and

F combines the effect of both;

and

are the molecular diffusion coefficients with and without sediment particles, respectively.

If

and all diffusion effects (substance, porosity and tortuosity) are assigned to the

Sc number, then

Sc =

F. Based on Maerki et al. [

39], we conclude that:

where m > 1 (m = 1.81 in the cited work).

Consequently, the

Sc value depends on the substrate level, residence time and compaction of the sediment, among other factors. Shen and Chen [

40] provided further details on the parameterizations of these effects in sediments.

References

- Abdelmonem, B.H.; Kamal, L.T.; Elbaz, R.M.; Khalifa, M.R.; Abdelnaser, A. From Contamination to Detection: The Growing Threat of Heavy Metals. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proshad, R.; Asharaful Abedin Asha, S.M.; Tan, R.; Lu, Y.; Abedin, M.A.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhao, Z. Machine Learning Models with Innovative Outlier Detection Techniques for Predicting Heavy Metal Contamination in Soils. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 481, 136536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ding, C.; Zhang, G.; Guo, Y.; Song, Y.; Thangaraj, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Dissolved and Particulate Heavy Metal Pollution Status in Seawater and Sedimentary Heavy Metals of the Bohai Bay. Marine Environmental Research 2023, 191, 106158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, P.; Hu, Z.; Shu, Q.; Chen, Y. Identification of the Sources and Influencing Factors of the Spatial Variation of Heavy Metals in Surface Sediments along the Northern Jiangsu Coast. Ecological Indicators 2022, 137, 108716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, F.; Meng, Y.; Byrne, P.; Ghomshei, M.; Abbaspour, K.C. Modeling Transport and Fate of Heavy Metals at the Watershed Scale: State-of-the-Art and Future Directions. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 878, 163087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- chnoor, J.; Sato, C.; McKechnie, D.; Sahoo, D. Processes, Coefficients, and Models for Simulating Toxic Organics and Heavy Metals in Surface Waters. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, The University of Iowa; EPA/600/3-87/015 1987, 319.

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hao, L.; Zhao, X.; Lu, J.; Shi, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, Q. Application of the Partial Least Square Regression Method in Determining the Natural Background of Soil Heavy Metals: A Case Study in the Songhua River Basin, China. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 918, 170695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Kang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yu, H.; Tao, Y.; Wang, H.; Niu, Y.; Niu, Y. Research on the Geochemical Background Values and Evolution Rules of Lake Sediments for Heavy Metals and Nutrients in the Eastern China Plain from 1937 to 2017. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 436, 129136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wang, H.; Du, S.; Gong, H.; Liu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, S. Bioavailability of Trace Metals in Sediments from Daya Bay Nature Reserve: Spatial Variation, Controlling Factors and the Exposure Risk Assessment for Aquatic Biota. Ecological Indicators 2024, 169, 112789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Falconer, R.; Lin, B. Modelling Trace Metal Concentration Distributions in Estuarine Waters. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2005, 64, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Han, L.; Chen, R.; Liu, Z.; Fan, Y.; An, X.; Zhai, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, T. Vulnerability Assessment of Soil Cadmium with Adsorption–Desorption Coupling Model. Ecological Indicators 2023, 146, 109904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristea, E.; Pârvulescu, O.C.; Lavric, V.; Oros, A. Assessment of Heavy Metal Contamination of Seawater and Sediments Along the Romanian Black Sea Coast: Spatial Distribution and Environmental Implications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z. Numerical Solution of a Moving Boundary Problem of One-Dimensional Flow in Semi-Infinite Long Porous Media with Threshold Pressure Gradient. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Champagne, P.; Ong, S.K.; Tyagi, R.D.; Lo, I.M.C. Remediation Technologies for Soils and Groundwater. Remediation Technologies for Soils and Groundwater 2007, 60, 1–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Du, S.L.; Cao, J.L.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhao, H.; Ding, T.T. Heavy Metals in Sediments of the River-Lake System in the Dianchi Basin, China: Their Pollution, Sources, and Risks. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 957, 177652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonin, S.; Andrade, C.A.; Monroy, J. Wave Climate and the Effect of Induced Currents over the Barrier Reef of the Cays of Alburquerque Island, Colombia. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, B.P. Diagenetic Models and Their Implementation; 1998; Vol. 15; ISBN 978-3-642-64399-6.

- Lynch, D.R.; Officer, C.B. Nonlinear Parameter Estimation for Sediment Cores. Chemical Geology 1984, 44, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolis, C. Tracer Dynamics in Ocean Sediments and the Deciphering of Past Climates. Mathematical computing modelling 1995, 21, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, K.; Gong, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, K.; Hu, S.; Fu, Y.; et al. Differentiating Environmental Scenarios to Establish Geochemical Baseline Values for Heavy Metals in Soil: A Case Study of Hainan Island, China. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 898, 165634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.M.; Kim, C.J.; Chung, C.S.; Kim, T.; Gu, H.S.; Kim, H.E.; Choi, K.Y. Applying New Regional Background Concentration Criteria to Assess Heavy Metal Contamination in Deep-Sea Sediments at an Ocean Dumping Site, Republic of Korea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2024, 200, 116065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivero-Verbel, R.; Eljarrat, E.; Johnson-Restrepo, B. Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants in Sediments and Marine Fish Species in Colombia: Occurrence, Distribution, and Implications for Human Risk Assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2025, 213, 117654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Alcala-Orozco, M.; Barraza-Quiroz, D.; De la Rosa, J.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Environmental Risks Associated with Trace Elements in Sediments from Cartagena Bay, an Industrialized Site at the Caribbean. Chemosphere 2020, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosic, M.; Restrepo, J.D.; Lonin, S.; Izquierdo, A.; Martins, F. Water and Sediment Quality in Cartagena Bay, Colombia: Seasonal Variability and Potential Impacts of Pollution. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2019, 216, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Murillo, P.; Gallego, J.L.; Leignel, V. Marine Pollution and Advances in Biomonitoring in Cartagena Bay in the Colombian Caribbean. Toxics 2023, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosic, M.; Restrepo Ángel, J.D. Sustainability Impacts of Sediments on the Estuary, Ports, and Fishing Communities of Cartagena Bay, Colombian Caribbean. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Cano, W.T.; Kim, K. How to Achieve Sustainably Beneficial Uses of Marine Sediments in Colombia ? Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosic, M.; Martins, F.; Lonin, S.; Izquierdo, A.; Restrepo, J.D. Hydrodynamic Modelling of a Polluted Tropical Bay: Assessment of Anthropogenic Impacts on Freshwater Runoff and Estuarine Water Renewal. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 236, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijn, L.C. van Principles of Sediment Transport in Rivers, Estuaries and Coastal Seas. Aqua Publ 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbarian, B.; Hunt, A.G.; Ewing, R.P.; Sahimi, M. Tortuosity in Porous Media: A Critical Review. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2013, 77, 1461–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, A.S.; Yaglom, A.M. Statistical Fluid Mechanics: The Mechanics of Turbulence, Volume 1; MIT Press, 1973; Vol. 60.

- Orani, A.M.; Vassileva, E.; Azemard, S.; Alonso-Hernandez, C. Trace Elements Contamination Assessment in Marine Sediments from Different Regions of the Caribbean Sea. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 399, 122934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchuk, G.I.; Kagan, B.A. Ocean Tides. Mathematical Models and Numerical Experiments; Pergamon Press, 1984.

- Pintilie, S.; Brânză, L.; Beţianu, C.; Pavel, L.V.; Ungureanu, F.; Gavrilescu, M. Modelling and Simulation of Heavy Metals Transport in Water and Sediments. Environmental Engineering and Management Journal 2007, 6, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, B.P. The Diffusive Tortuosity of Fine-Grained Unlithified Sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1996, 60, 3139–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Luo, M.; Li, F.; Qi, X.; Huo, A.; Wang, Z.; He, B.; Takara, K.; Nover, D.; Wang, Y. Urban Flood Numerical Simulation: Research, Methods and Future Perspectives. Environmental Modelling & Software 2022, 156, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jia, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, S.; Hu, J. Assessment of Heavy Metals Remobilization and Release Risks at the Sediment-Water Interface in Estuarine Environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 187, 114517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukue, M.; Yanai, M.; Sato, Y.; Fujikawa, T.; Furukawa, Y.; Tani, S. Background Values for Evaluation of Heavy Metal Contamination in Sediments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2006, 136, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maerki, M.; Wehrli, B.; Dinkel, C.; Müller, B. The Influence of Tortuosity on Molecular Diffusion in Freshwater Sediments of High Porosity. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2004, 68, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Chen, Z. Critical Review of the Impact of Tortuosity on Diffusion. Chemical Engineering Science 2007, 62, 3748–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).