Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Background and Motivation

- Unigram model:

- Bigram model:

- Trigram model:

- N-gram model:

- Statistical language models (SLM): SLMs [16,17,18] are developed based on statistical learning methods proposed in the 1990s. The main idea is to build a word prediction model based on the Markov hypothesis. Bigram and trigram language models SLMs have been widely used to improve task performance in information retrieval (IR)[19] and natural language processing (NLP)[20]. These models often suffer from the curse of dimensionality. Also, accurate estimation of language models is difficult due to the many transition probabilities that need to be estimated.

- Neural language models (NLM): NLMs [21,22] characterize the probability of word sequences by neural networks, for example, multilayer perceptron (MLP) and recurrent neural network (RNN). In these models, neural networks try to learn feature selection and representation by gradient. Various approaches such as Word2vec, Glove, Fasttext, and Bert have been proposed for learning distributed word representations, which have been very effective in various NLP tasks.

- Pre-trained language models (PLM): These are neural networks trained on the large-scale unlabeled corpus, from which various downstream tasks can be further tuned. One of the first models presented in this category is ELMo [23]. This model captures context-aware word representations by pre-training a bi-directional LSTM (biLSTM) network (instead of learning fixed word representations) and then fine-tuning the biLSTM network. Other models have been developed based on this idea, the most important of which are GPT-2[24] and BART [25].

- Large language models (LLM):. Researchers use the term LLM for large PLMs. They find that scaling PLMs often leads to improved model capacity on downstream tasks (i.e., following the scaling law [26]). One notable application of LLMs is ChatGPT2, which adapts the GPT series LLMs for conversation, offering the ability to converse with humans.

Search Method

Problem Statement and Research Questions

- What are the capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) in biological data analysis?

- Which models perform better in predicting biological traits and behaviors?

- How can LLMs model long-range dependencies and genetic interactions?

- What are the limitations and challenges in applying LLMs to biological data?

- How effective are LLMs in predicting complex biological structures and molecular interactions?

- What are the differences between supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid learning methods in biological models?

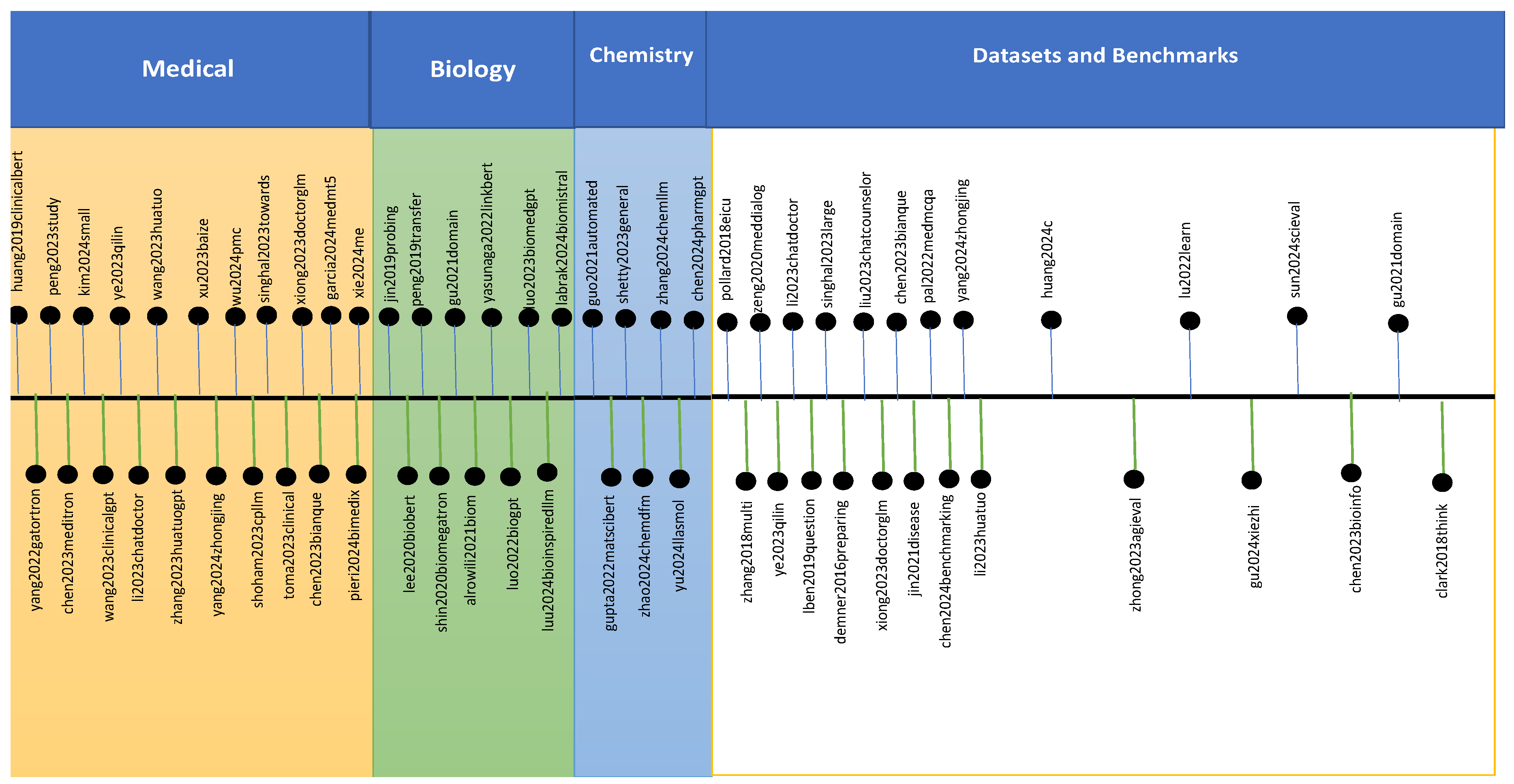

0.1. Big Picture of the Literature Review

Document Outline

1. Textual Scientific Large Language Models

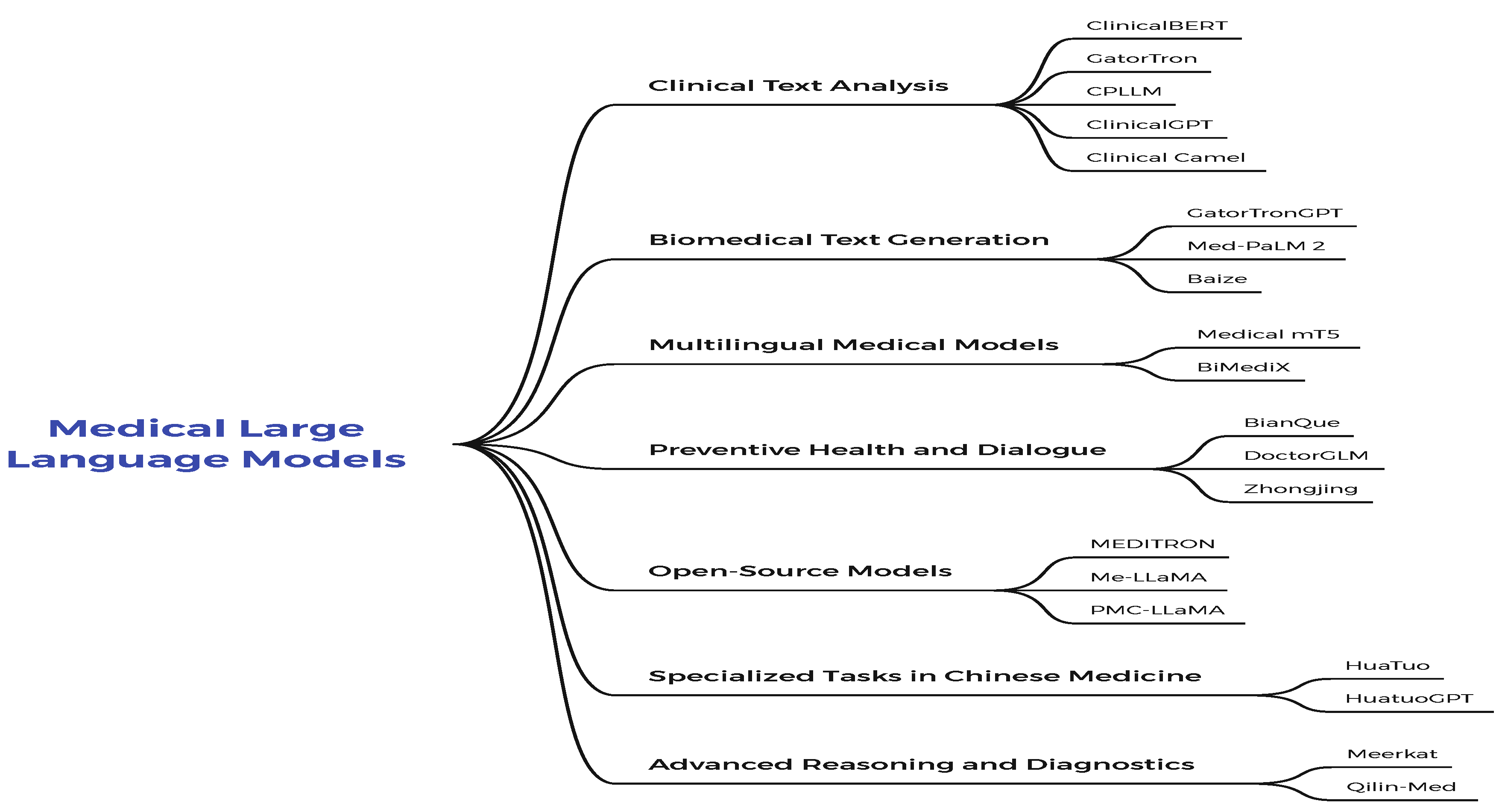

1.1. Medical Large Language Models

- Clinical Guidelines: a new dataset of 46 thousand clinical practice guidelines from various healthcare-related sources.

- Article Abstracts: abstracts available from 16.1 million closed-access PubMed and PubMed Central articles.

- Medical Articles: full-text articles extracted from 5 million publicly available PubMed and PubMed Central articles.

- Replay dataset: public domain data distilled to write 1% of the total corpus.

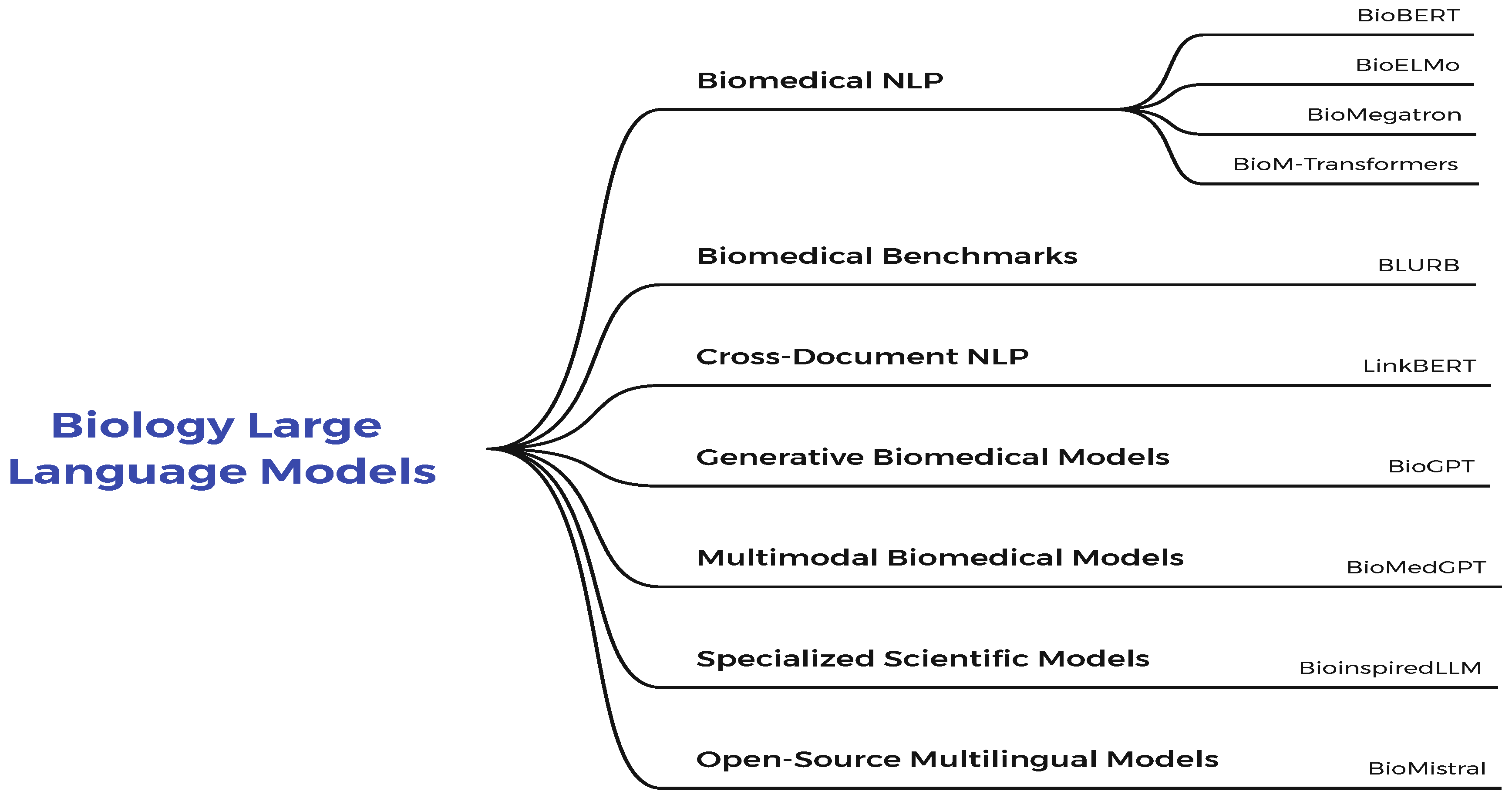

1.2. Biology Large Language Models

-

Sentence similarity with data:

- MedSTS:sentence pairs

- BIOSSES: sentence pairs

-

Named entity recognition with data:

- BC5CDR-disease: mentions

- BC5CDR-chemical: mentions - ShARe/CLEFE mentions

-

Relation extraction with data:

- DDI: relations

- ChemProt: relations

- i2b2 2010: relations

-

Document classification with data:

- HoC: documents

-

Inference with data:

- MedNLI: pairs

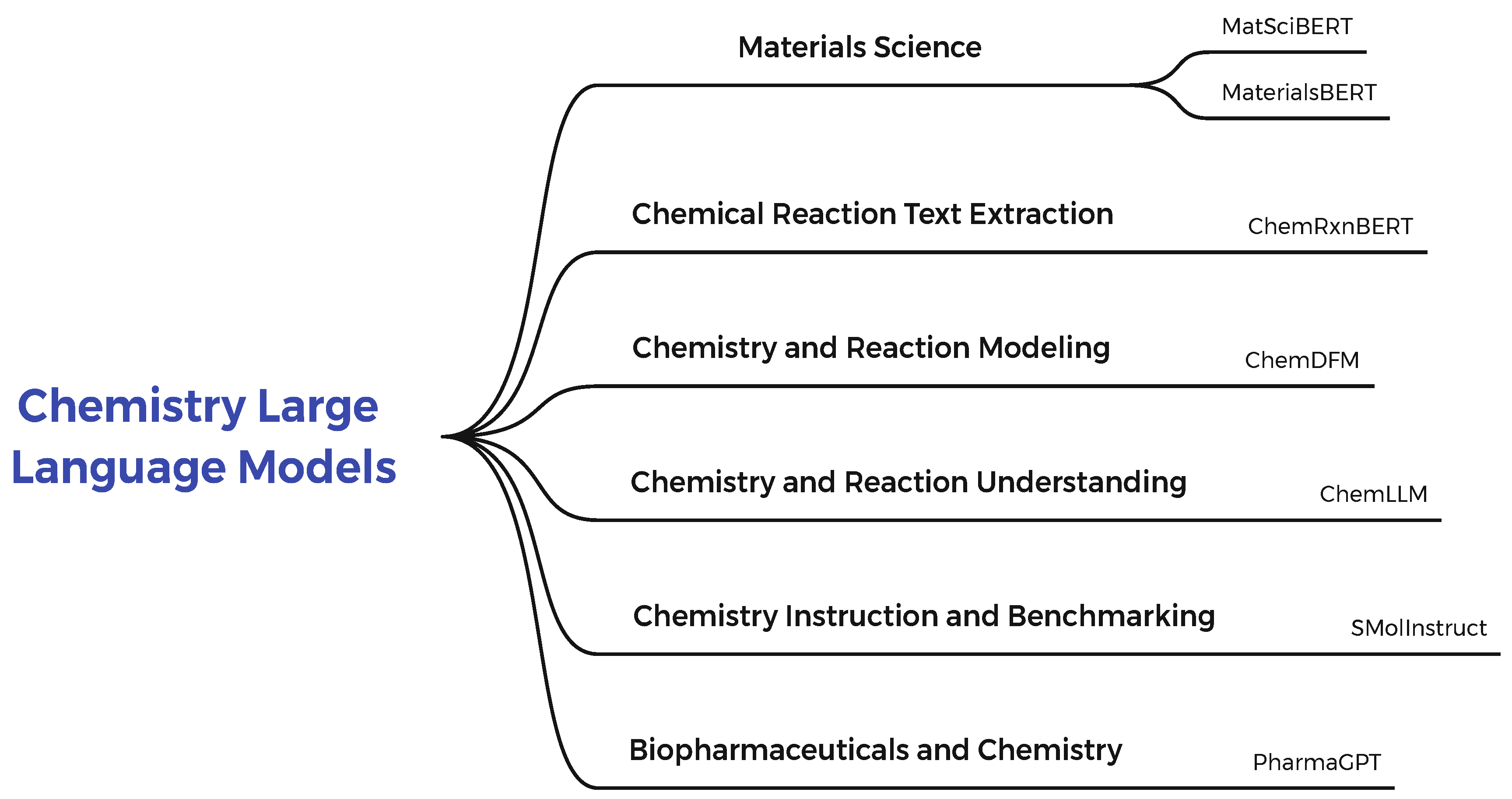

1.3. Chemistry Large Language Models

- Name Conversion: IUPAC to Molecular Formula (NC-I2F), IUPAC to SMILES (NC-I2S), SMILES to Molecular Formula (NC-S2F), and SMILES to IUPAC (NC-S2I)

- Molecule Description: Molecule Captioning (MC), and Molecule Generation (MG)

- Property Prediction: ESOL (PP-ESOL), LIPO (PP-LIPO), BBBP (PP-BBBP), ClinTox (PP-ClinTox), HIV (PP-HIV), and SIDER (PP-SIDER)

- Chemical Reaction: Forward Synthesis (FS) and Retrosynthesis (RS)

1.4. Datasets and Benchmarks

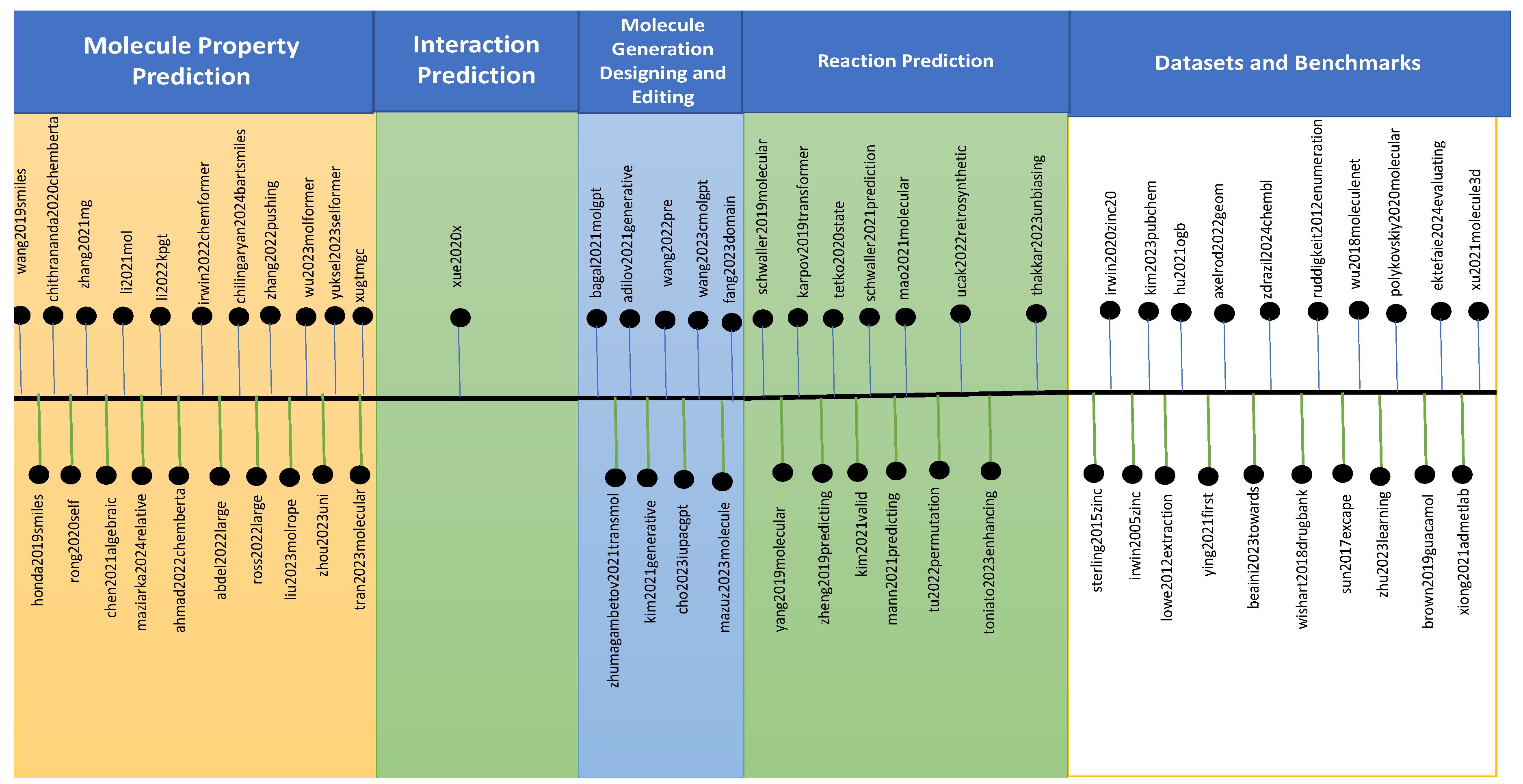

2. Molecular Large Language Models

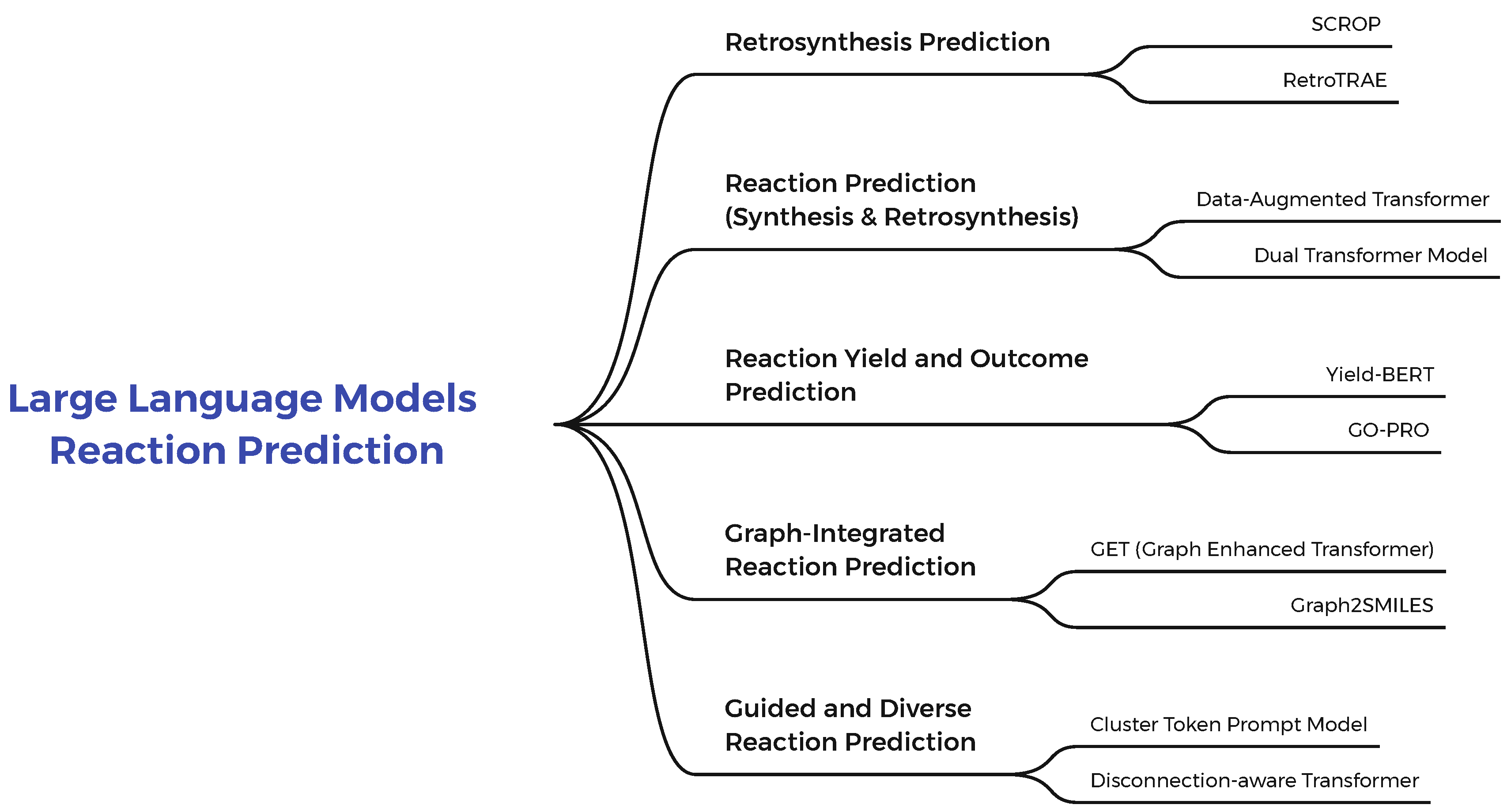

2.1. Large Language Models for Reaction Prediction

2.2. Datasets and Benchmarks

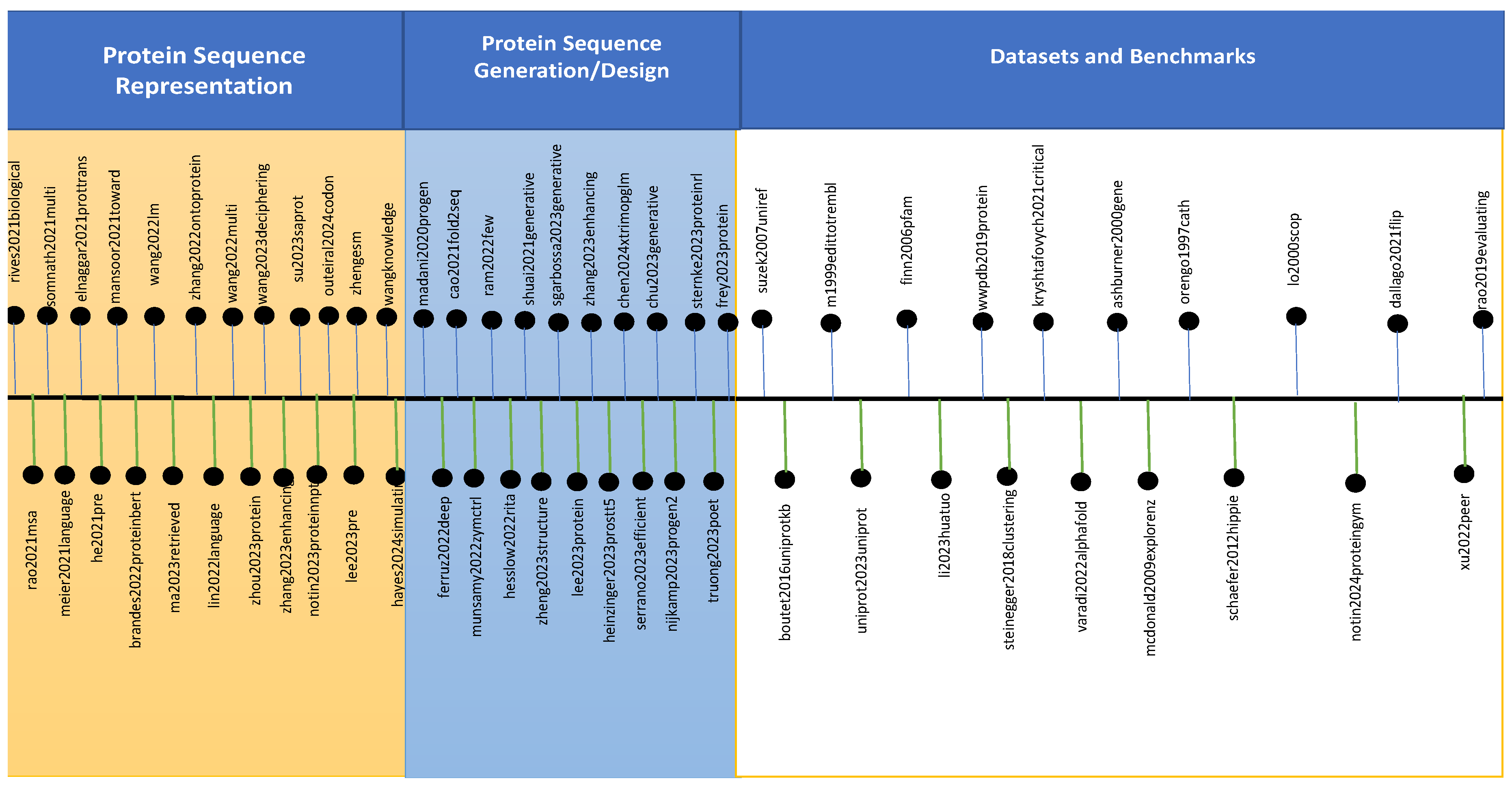

3. Protein Large Language Models

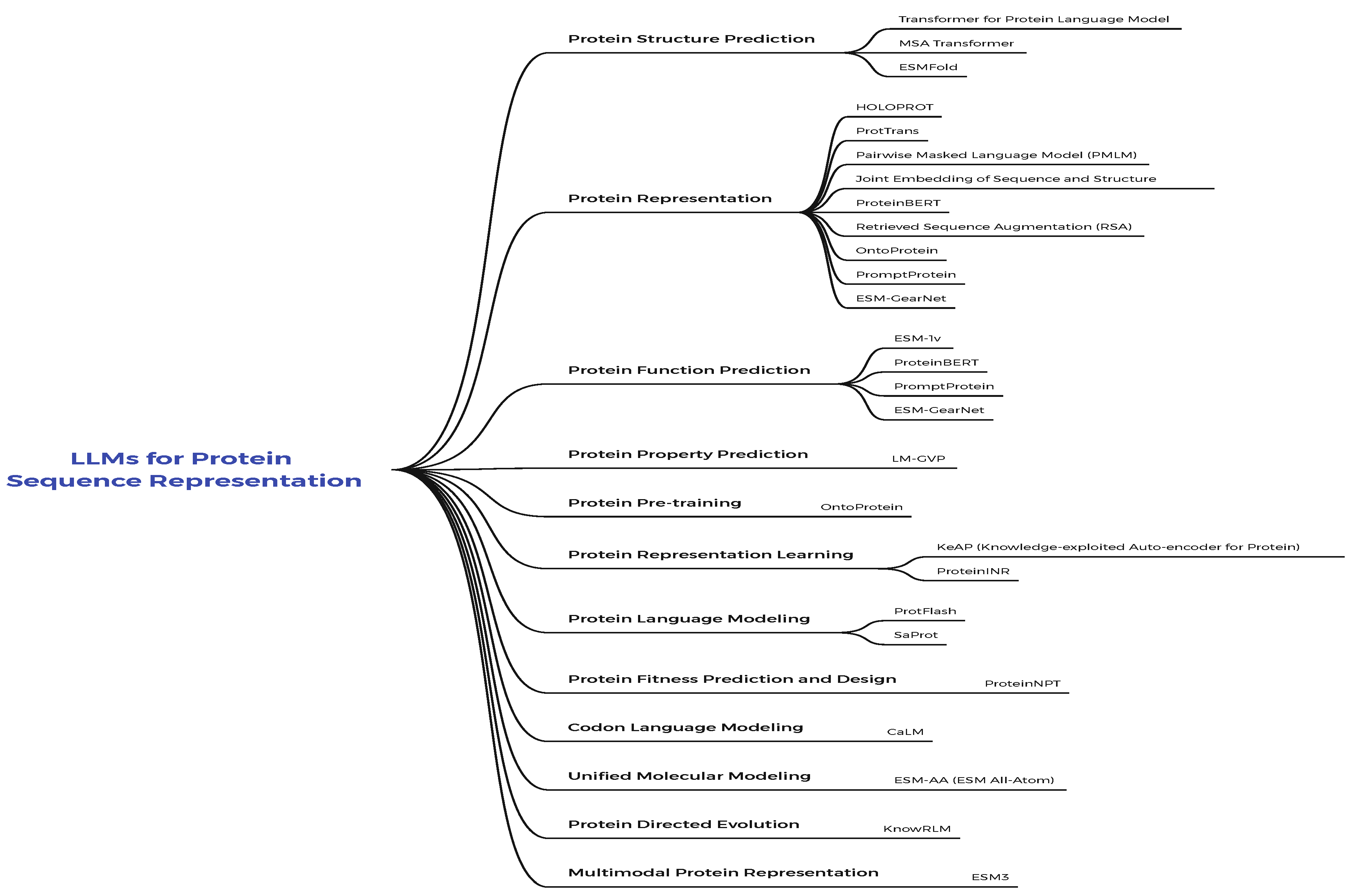

3.1. LLMs for Protein Sequence Representation

3.2. LLMs for Protein Sequence Generation and Designing

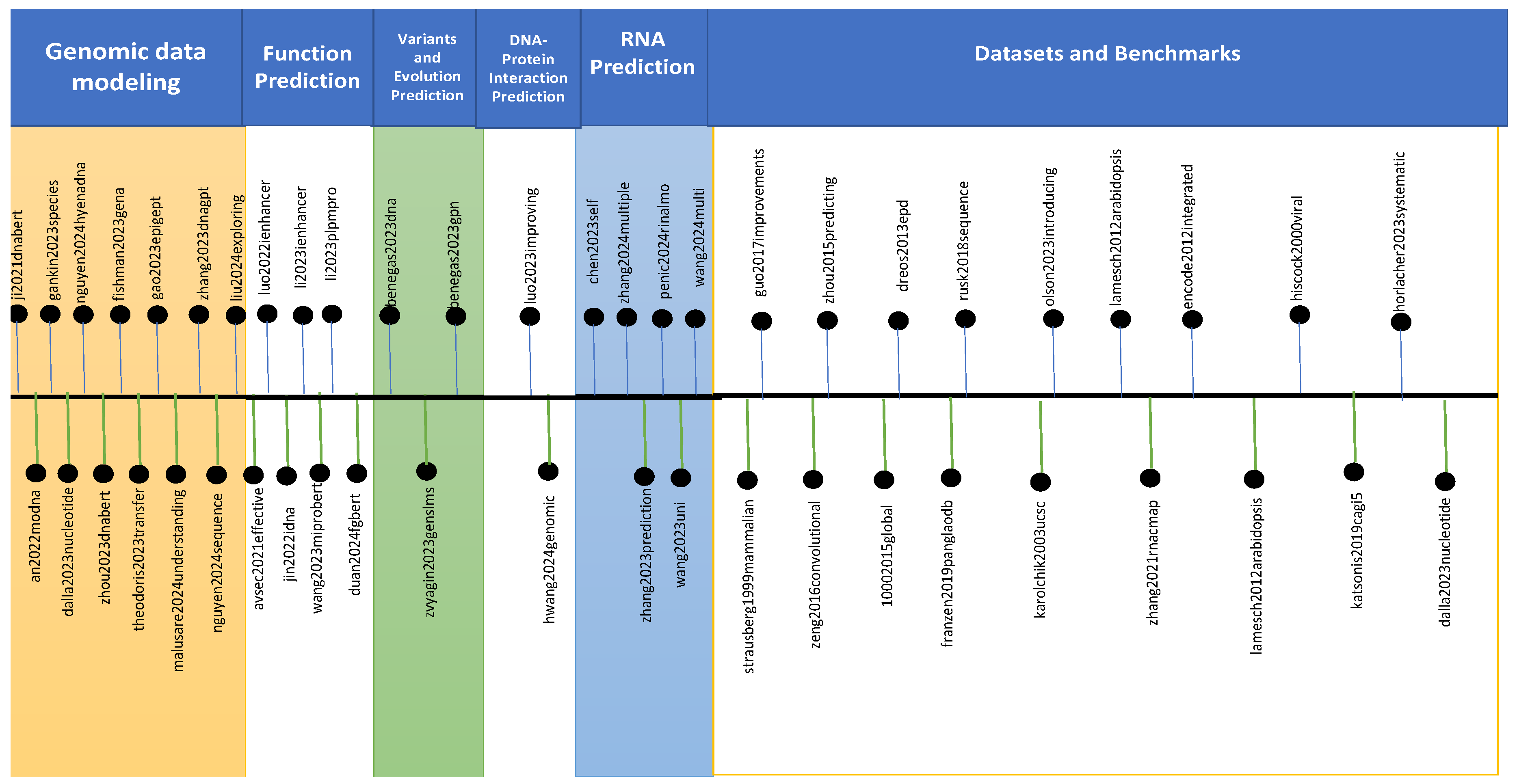

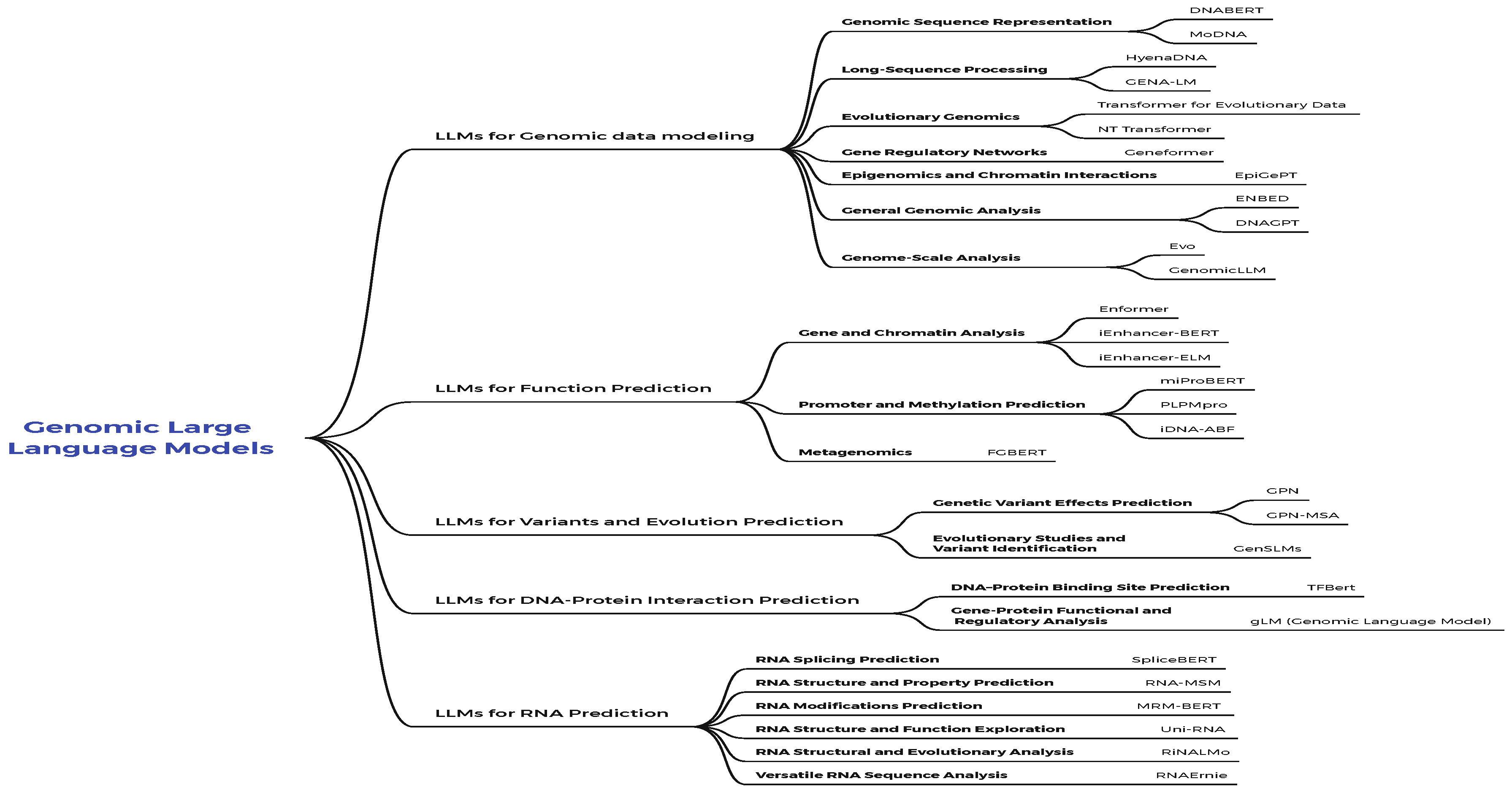

4. Genomic Large Language Models

4.1. LLMs for Genomic Data Modeling

- A 500 million parameter model trained on sequences extracted from the human reference genome.

- A 2.5 billion parameter model, both trained on 3202 genetically diverse human genomes

- A 2.5 billion parameter model, including 850 species from different phyla including 11 model organisms.

4.2. LLMs for Function Prediction

4.3. LLMs for Variants and Evolution Prediction

4.4. LLMs for DNA-Protein Interaction Prediction

4.5. LLMs for RNA Prediction

4.6. Datasets and Benchmarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Training Multi-Billion Parameter Language Models Using Model Parallelism (Megatron-LM)[238].

- Larger Biomedical Domain Language Model(BioMegatron)[72].

- End-to-End Training of Neural Retrievers for Open-Domain Question Answering[239]

- Large Scale Multi-Actor Generative Dialog Modeling[240].

- Local Knowledge Powered Conversational Agents[241]

- MEGATRON-CNTRL[242]

- InstructRetro[243]

Appendix B

-

Meta

- Llama 3.2-1|3|11|90B: https://llama.meta.com/

- Llama 3.1-8|70|405B: https://llama.meta.com/

- Llama 3-8|70B: https://llama.meta.com/llama3/

- Llama 2-7|13|70B: https://llama.meta.com/llama2/

- Llama 1-7|13|33|65B: https://ai.facebook.com/blog/large-language-model-llama-meta-ai/

- OPT-1.3|6.7|13|30|66B: https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.01068

-

Mistral AI

- Codestral-7|22B https://mistral.ai/news/codestral/

- Mistral-7B: https://mistral.ai/news/announcing-mistral-7b/

- Mixtral-8x7B: https://mistral.ai/news/mixtral-of-experts/

- Mixtral-8x22B: https://mistral.ai/news/mixtral-8x22b/

-

Google

- RecurrentGemma-2B: https://github.com/google-deepmind/recurrentgemma

-

Apple

- OpenELM-1.1|3B: https://huggingface.co/apple/OpenELM

-

Microsoft

- Phi1-1.3B: https://huggingface.co/microsoft/phi-1

- Phi2-2.7B: https://huggingface.co/microsoft/phi-2

- Phi3-3.8|7|14B: https://huggingface.co/microsoft/Phi-3-mini-4k-instruct

-

AllenAI

-

xAI

- Grok-1-314B-MoE https://x.ai/blog/grok-os

-

Cohere

- Command R-35B: https://huggingface.co/CohereForAI/c4ai-command-r-v01

-

DeepSeek

- DeepSeek-Math-7B: https://huggingface.co/collections/deepseek-ai/

- DeepSeek-Coder-1.3|6.7|7|33B: https://huggingface.co/collections/deepseek-ai/

- DeepSeek-VL-1.3|7Bhttps://huggingface.co/collections/deepseek-ai/

- DeepSeek-MoE-16B: https://huggingface.co/collections/deepseek-ai/

- DeepSeek-v2-236B-MoE: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.04434

- DeepSeek-Coder-v2-16|236B-MOE: https://github.com/deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-Coder-V2

-

Alibaba

- Qwen-1.8B|7B|14B|72B: https://huggingface.co/collections/Qwen/

- Qwen1.5-0.5B|1.8B|4B|7B|14B|32B|72B|110B|MoE-A2.7B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen1.5/

- Qwen2-0.5B|1.5B|7B|57B-A14B-MoE|72B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen2

- Qwen2.5-0.5B|1.5B|3B|7B|14B|32B|72B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen2.5/

- CodeQwen1.5-7B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/codeqwen1.5/

- Qwen2.5-Coder-1.5B|7B|32B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen2.5-coder/

- Qwen2-Math-1.5B|7B|72B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen2-math/

- Qwen2.5-Math-1.5B|7B|72B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen2.5-math/

- Qwen-VL-7B: https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen-VL

- Qwen2-VL-2B|7B|72B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen2-vl/

- Qwen2-Audio-7B: https://qwenlm.github.io/blog/qwen2-audio/

-

01-ai

- Yi1.5-6|9|34B: https://huggingface.co/collections/01-ai/

- Yi-VL-6B|34B: https://huggingface.co/collections/01-ai/

-

Baichuan

- Baichuan-7|13B: https://huggingface.co/baichuan-inc

- Baichuan2-7|13B: https://huggingface.co/baichuan-inc

-

Nvidia

- Nemotron-4-340B: https://huggingface.co/nvidia/Nemotron-4-340B-Instruct

-

BLOOM

-

Zhipu AI

- GLM-2|6|10|13|70B: https://huggingface.co/THUDM

- CogVLM2-19B: https://huggingface.co/collections/THUDM/

-

OpenBMB

- MiniCPM-2B: https://huggingface.co/collections/openbmb/

- OmniLLM-12B: https://huggingface.co/openbmb/OmniLMM-12B

- VisCPM-10B: https://huggingface.co/openbmb/VisCPM-Chat

- CPM-Bee-1|2|5|10B: https://huggingface.co/collections/openbmb/

-

RWKV Foundation

- RWKV-v4|5|6: https://huggingface.co/RWKV

-

ElutherAI

- Pythia-1|1.4|2.8|6.9|12B: https://github.com/EleutherAI/pythia

-

Stability AI

- StableLM-3B: https://huggingface.co/collections/stabilityai/

- StableLM-v2-1.6|12B: https://huggingface.co/collections/stabilityai/

- StableCode-3B: https://huggingface.co/collections/stabilityai/

-

BigCode

- StarCoder-1|3|7B: https://huggingface.co/collections/bigcode/

- StarCoder2-3|7|15B: https://huggingface.co/collections/bigcode/

-

DataBricks

- DBRX-132B-MoE: https://www.databricks.com/

-

Shanghai AI Laboratory

- InternLM2-1.8|7|20B: https://huggingface.co/collections/internlm/

- InternLM-Math-7B|20B: https://huggingface.co/collections/internlm/

- InternLM-XComposer2-1.8|7B: https://huggingface.co/collections/internlm/

- InternVL-2|6|14|26: https://huggingface.co/collections/OpenGVLab/

References

- Turing, A. Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind. Vol. LIX,?. 236. In Proceedings of the Computers & Thought, 1950.

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bellegarda, J.R. Statistical language model adaptation: review and perspectives. Speech communication 2004, 42, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Hou, L.; Nie, L.; Li, J. A survey of knowledge enhanced pre-trained language models. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauphin, Y.N.; Fan, A.; Auli, M.; Grangier, D. Language modeling with gated convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2017; pp. 933–941. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Casas, D.d.L.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15556 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.; Kardas, M.; Cucurull, G.; Scialom, T.; Hartshorn, A.; Saravia, E.; Poulton, A.; Kerkez, V.; Stojnic, R. Galactica: A large language model for science. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.09085 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288 2023. [Google Scholar]

- GLM, T.; Zeng, A.; Xu, B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Yin, D.; Zhang, D.; Rojas, D.; Feng, G.; Zhao, H.; et al. Chatglm: A family of large language models from glm-130b to glm-4 all tools. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.12793 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A.; Xiao, B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, B.; Bian, C.; Yin, C.; Lv, C.; Pan, D.; Wang, D.; Yan, D.; et al. Baichuan 2: Open large-scale language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.10305 2023. [Google Scholar]

- GDR, H.B.; Sharon, N.; Australia, E. Nomenclature and symbolism for amino acids and peptides. Pure and Applied Chemistry 1984, 56, 595–624. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ivison, H.; Dasigi, P.; Hessel, J.; Khot, T.; Chandu, K.; Wadden, D.; MacMillan, K.; Smith, N.A.; Beltagy, I.; et al. How far can camels go? exploring the state of instruction tuning on open resources. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 74764–74786. [Google Scholar]

- Neubig, G. Neural machine translation and sequence-to-sequence models: A tutorial. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.01619 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Min, S.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Choi, Y.; Hajishirzi, H. Infini-gram: Scaling unbounded n-gram language models to a trillion tokens. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.17377 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek, F. Statistical methods for speech recognition; MIT press, 1998.

- Gao, J.; Lin, C.Y. Introduction to the special issue on statistical language modeling, 2004.

- Rosenfeld, R. Two decades of statistical language modeling: Where do we go from here? Proceedings of the IEEE 2000, 88, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Croft, W.B. Statistical language modeling for information retrieval. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thede, S.M.; Harper, M. A second-order hidden Markov model for part-of-speech tagging. In Proceedings of the 37th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 1999; pp. 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Ducharme, R.; Vincent, P. A neural probabilistic language model. Advances in neural information processing systems 2000, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Karafiát, M.; Burget, L.; Cernockỳ, J.; Khudanpur, S. Recurrent neural network based language model. In Proceedings of the Interspeech. Makuhari; 2010; Vol. 2, pp. 1045–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Zettlemoyer, L. Deep contextualized word representations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M. Bart: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.13461 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Altosaar, J.; Ranganath, R. Clinicalbert: Modeling clinical notes and predicting hospital readmission. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.05342 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Chen, A.; PourNejatian, N.; Shin, H.C.; Smith, K.E.; Parisien, C.; Compas, C.; Martin, C.; Flores, M.G.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Gatortron: A large clinical language model to unlock patient information from unstructured electronic health records. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.03540 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Yang, X.; Chen, A.; Smith, K.E.; PourNejatian, N.; Costa, A.B.; Martin, C.; Flores, M.G.; Zhang, Y.; Magoc, T.; et al. A study of generative large language model for medical research and healthcare. NPJ digital medicine 2023, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cano, A.H.; Romanou, A.; Bonnet, A.; Matoba, K.; Salvi, F.; Pagliardini, M.; Fan, S.; Köpf, A.; Mohtashami, A.; et al. Meditron-70b: Scaling medical pretraining for large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.16079 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Hwang, H.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Kim, D.; Lee, T.; Yoon, C.; Sohn, J.; Choi, D.; Kang, J. Small language models learn enhanced reasoning skills from medical textbooks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.00376 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yang, G.; Du, Z.; Fan, L.; Li, X. ClinicalGPT: large language models finetuned with diverse medical data and comprehensive evaluation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.09968 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Q.; Liu, J.; Chong, D.; Zhou, P.; Hua, Y.; Liu, A. Qilin-med: Multi-stage knowledge injection advanced medical large language model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09089 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Dan, R.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y. Chatdoctor: A medical chat model fine-tuned on a large language model meta-ai (llama) using medical domain knowledge. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Xi, N.; Qiang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Qin, B.; Liu, T. Huatuo: Tuning llama model with chinese medical knowledge. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.06975 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Jiang, F.; Yu, F.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, G.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Q.; et al. Huatuogpt, towards taming language model to be a doctor. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.15075 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Taori, R.; Gulrajani, I.; Zhang, T.; Dubois, Y.; Li, X.; Guestrin, C.; Liang, P.; Hashimoto, T.B. Stanford alpaca: An instruction-following llama model, 2023.

- Zeng, A.; Liu, X.; Du, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lai, H.; Ding, M.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Xia, X.; et al. Glm-130b: An open bilingual pre-trained model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.02414 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Guo, D.; Duan, N.; McAuley, J. Baize: An open-source chat model with parameter-efficient tuning on self-chat data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.01196 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Taori, R.R. Ingredients for Accessible and Sustainable Language Models. PhD thesis, Stanford University, 2024.

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Li, T.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, Z.; Lin, Z.; Xing, E.P.; et al. Lmsys-chat-1m: A large-scale real-world llm conversation dataset. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.11998 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D. Chatgpt and open-ai models: A preliminary review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, K. GPT-4 is here: what scientists think. Nature 2023, 615, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, G.; Xu, H.; Jia, Y.; Zan, H. Zhongjing: Enhancing the chinese medical capabilities of large language model through expert feedback and real-world multi-turn dialogue. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2024; Vol. 38, pp. 19368–19376. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Lin, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y. PMC-LLaMA: toward building open-source language models for medicine. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2024, ocae045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoham, O.B.; Rappoport, N. Cpllm: Clinical prediction with large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.11295 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Neal, D.; et al. Towards expert-level medical question answering with large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.09617 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Pan, E.; Oufattole, N.; Weng, W.H.; Fang, H.; Szolovits, P. What disease does this patient have? a large-scale open domain question answering dataset from medical exams. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Umapathi, L.K.; Sankarasubbu, M. Medmcqa: A large-scale multi-subject multi-choice dataset for medical domain question answering. In Proceedings of the Conference on health, inference, and learning; PMLR, 2022; pp. 248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q.; Dhingra, B.; Liu, Z.; Cohen, W.W.; Lu, X. Pubmedqa: A dataset for biomedical research question answering. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.06146 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Basart, S.; Zou, A.; Mazeika, M.; Song, D.; Steinhardt, J. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.03300 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, A.; Lawler, P.R.; Ba, J.; Krishnan, R.G.; Rubin, B.B.; Wang, B. Clinical camel: An open expert-level medical language model with dialogue-based knowledge encoding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.12031 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q.; Shen, D. Doctorglm: Fine-tuning your chinese doctor is not a herculean task. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.01097 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xing, X.; Xu, Z.; Fang, K.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; et al. Bianque: Balancing the questioning and suggestion ability of health llms with multi-turn health conversations polished by chatgpt. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.15896 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Segonne, V.; Mannion, A.; Schwab, D.; Goeuriot, L.; Portet, F. MedDialog-FR: a French Version of the MedDialog Corpus for Multi-label Classification and Response Generation related to Women’s Intimate Health. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Patient-Oriented Language Processing (CL4Health)@ LREC-COLING 2024; 2024; pp. 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. MING-MOE: Enhancing Medical Multi-Task Learning in Large Language Models with Sparse Mixture of Low-Rank Adapter Experts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.09027 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dinghao, P.; Zhihao, Y.; Hongfei, L.; Jian, W. Dialogue Symptom Inference Based on Structured Self-Attention Network. Journal of Computer Engineering & Applications 2024, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Tang, J.; Qin, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Z.; Liang, X. Meddg: A large-scale medical consultation dataset for building medical dialogue system. Europe PMC 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y. ChatGLM-6B Fine-Tuning for Cultural and Creative Products Advertising Words. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Culture-Oriented Science and Technology (CoST). IEEE; 2023; pp. 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Ding, W.; Lin, C. ChatGPT. tackle the growing carbon footprint of generative AI 2023, 615, 586. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ferrero, I.; Agerri, R.; Salazar, A.A.; Cabrio, E.; de la Iglesia, I.; Lavelli, A.; Magnini, B.; Molinet, B.; Ramirez-Romero, J.; Rigau, G.; et al. MedMT5: An Open-Source Multilingual Text-to-Text LLM for the Medical Domain. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), 2024, pp. 11165–11177.

- Xie, Q.; Chen, Q.; Chen, A.; Peng, C.; Hu, Y.; Lin, F.; Peng, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Keloth, V.; et al. Me llama: Foundation large language models for medical applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.12749 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, S.; Mullappilly, S.S.; Khan, F.S.; Anwer, R.M.; Khan, S.; Baldwin, T.; Cholakkal, H. Bimedix: Bilingual medical mixture of experts llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13253, arXiv:2402.13253 2024.

- Jin, Q.; Dhingra, B.; Cohen, W.W.; Lu, X. Probing biomedical embeddings from language models. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.02181 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kenton, J.D.M.W.C.; Toutanova, L.K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of naacL-HLT. Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019, Vol. 1, p. 2.

- Peters, M.E.; Ruder, S.; Smith, N.A. To tune or not to tune? adapting pretrained representations to diverse tasks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.05987 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Tanabe, L.K.; Ando, R.J.n.; Kuo, C.J.; Chung, I.F.; Hsu, C.N.; Lin, Y.S.; Klinger, R.; Friedrich, C.M.; Ganchev, K.; et al. Overview of BioCreative II gene mention recognition. Genome biology 2008, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, E.F.; De Meulder, F. Introduction to the CoNLL-2003 shared task: Language-independent named entity recognition. arXiv 2003, arXiv:cs/0306050. [Google Scholar]

- Romanov, A.; Shivade, C. Lessons from natural language inference in the clinical domain. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.06752 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Yan, S.; Lu, Z. Transfer learning in biomedical natural language processing: an evaluation of BERT and ELMo on ten benchmarking datasets. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.05474 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.C.; Zhang, Y.; Bakhturina, E.; Puri, R.; Patwary, M.; Shoeybi, M.; Mani, R. BioMegatron: larger biomedical domain language model. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2020; pp. 4700–4706. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Tinn, R.; Cheng, H.; Lucas, M.; Usuyama, N.; Liu, X.; Naumann, T.; Gao, J.; Poon, H. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare (HEALTH) 2021, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Johnson, R.J.; Sciaky, D.; Wei, C.H.; Leaman, R.; Davis, A.P.; Mattingly, C.J.; Wiegers, T.C.; Lu, Z. BioCreative V CDR task corpus: a resource for chemical disease relation extraction. Database 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doğan, R.I.; Leaman, R.; Lu, Z. NCBI disease corpus: a resource for disease name recognition and concept normalization. Journal of biomedical informatics 2014, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, N.; Ohta, T.; Tsuruoka, Y.; Tateisi, Y.; Kim, J.D. Introduction to the bio-entity recognition task at JNLPBA. In Proceedings of the International Joint Workshop on Natural Language Processing in Biomedicine and its Applications (NLPBA/BioNLP); 2004; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, B.; Li, J.J.; Patel, R.; Yang, Y.; Marshall, I.J.; Nenkova, A.; Wallace, B.C. A corpus with multi-level annotations of patients, interventions and outcomes to support language processing for medical literature. In Proceedings of the conference. Association for Computational Linguistics. Meeting. NIH Public Access; 2018; Vol. 2018, p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Krallinger, M.; Rabal, O.; Akhondi, S.A.; Pérez, M.P.; Santamaría, J.; Rodríguez, G.P.; Tsatsaronis, G.; Intxaurrondo, A.; López, J.A.; Nandal, U.; et al. Overview of the BioCreative VI chemical-protein interaction Track. In Proceedings of the sixth BioCreative challenge evaluation workshop; 2017; Vol. 1, pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Zazo, M.; Segura-Bedmar, I.; Martínez, P.; Declerck, T. The DDI corpus: An annotated corpus with pharmacological substances and drug–drug interactions. Journal of biomedical informatics 2013, 46, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, À.; Piñero, J.; Queralt-Rosinach, N.; Rautschka, M.; Furlong, L.I. Extraction of relations between genes and diseases from text and large-scale data analysis: implications for translational research. BMC bioinformatics 2015, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soğancıoğlu, G.; Öztürk, H.; Özgür, A. BIOSSES: a semantic sentence similarity estimation system for the biomedical domain. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, i49–i58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nentidis, A.; Bougiatiotis, K.; Krithara, A.; Paliouras, G. Results of the seventh edition of the bioasq challenge. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: International Workshops of ECML PKDD 2019, Proceedings, Part II. Springer. Würzburg, Germany, 16–20 September 2019; 2020; pp. 553–568. [Google Scholar]

- Alrowili, S.; Vijay-Shanker, K. BioM-transformers: building large biomedical language models with BERT, ALBERT and ELECTRA. In Proceedings of the 20th workshop on biomedical language processing; 2021; pp. 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga, M.; Leskovec, J.; Liang, P. Linkbert: Pretraining language models with document links. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15827 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, R.; Sun, L.; Xia, Y.; Qin, T.; Zhang, S.; Poon, H.; Liu, T.Y. BioGPT: generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. Briefings in bioinformatics 2022, 23, bbac409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fan, S.; Yang, K.; Wu, Y.; Qiao, M.; Nie, Z. Biomedgpt: Open multimodal generative pre-trained transformer for biomedicine. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.09442 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luu, R.K.; Buehler, M.J. BioinspiredLLM: Conversational Large Language Model for the Mechanics of Biological and Bio-Inspired Materials. Advanced Science 2024, 11, 2306724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrak, Y.; Bazoge, A.; Morin, E.; Gourraud, P.A.; Rouvier, M.; Dufour, R. Biomistral: A collection of open-source pretrained large language models for medical domains. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.10373 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Lu, Z. An empirical study of multi-task learning on BERT for biomedical text mining. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.02799 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Ibanez-Lopez, A.S.; Gao, H.; Quach, V.; Coley, C.W.; Jensen, K.F.; Barzilay, R. Automated chemical reaction extraction from scientific literature. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2021, 62, 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Zaki, M.; Krishnan, N.A.; Mausam. MatSciBERT: A materials domain language model for text mining and information extraction. npj Computational Materials 2022, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, P.; Rajan, A.C.; Kuenneth, C.; Gupta, S.; Panchumarti, L.P.; Holm, L.; Zhang, C.; Ramprasad, R. A general-purpose material property data extraction pipeline from large polymer corpora using natural language processing. npj Computational Materials 2023, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, D.; Chen, L.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Fan, S.; Shen, G.; et al. Chemdfm: Dialogue foundation model for chemistry. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.14818 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, W.; Tan, Q.; Chen, J.; Yan, H.; Yan, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Yue, X.; Zhou, D.; et al. Chemllm: A chemical large language model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06852 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D1373–D1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, D.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; De Veij, M.; Félix, E.; Magariños, M.P.; Mosquera, J.F.; Mutowo, P.; Nowotka, M.; et al. ChEMBL: towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47, D930–D940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, J.; Owen, G.; Dekker, A.; Ennis, M.; Kale, N.; Muthukrishnan, V.; Turner, S.; Swainston, N.; Mendes, P.; Steinbeck, C. ChEBI in 2016: Improved services and an expanding collection of metabolites. Nucleic acids research 2016, 44, D1214–D1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, J.J.; Tang, K.G.; Young, J.; Dandarchuluun, C.; Wong, B.R.; Khurelbaatar, M.; Moroz, Y.S.; Mayfield, J.; Sayle, R.A. ZINC20—a free ultralarge-scale chemical database for ligand discovery. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2020, 60, 6065–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.C.; Myers, A.; Graham, S.J.; D’Agostino, P.; Apple, K. The USPTO patent assignment dataset: Descriptions and analysis. SSRN 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigh, D.S.; Arrowsmith, J.; Pomberger, A.; Felton, K.C.; Lapkin, A.A. ORDerly: Data Sets and Benchmarks for Chemical Reaction Data. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2024, 64, 3790–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, B. Preprints and Scholarly Communication in Chemistry: A look at ChemRxiv. Chemistry International 2018, 40, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Baker, F.N.; Chen, Z.; Ning, X.; Sun, H. Llasmol: Advancing large language models for chemistry with a large-scale, comprehensive, high-quality instruction tuning dataset. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.09391 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Bai, Z.; Xu, P.; Fang, Y.; Fang, J.; Wu, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, R.; Xia, Y.; et al. PharmGPT: Domain-Specific Large Language Models for Bio-Pharmaceutical and Chemistry. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.18045 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, T.J.; Johnson, A.E.; Raffa, J.D.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R.G.; Badawi, O. The eICU Collaborative Research Database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Scientific data 2018, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Yang, W.; Ju, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, M.; Zeng, J.; Dong, X.; Zhang, R.; et al. MedDialog: Large-scale medical dialogue datasets. In Proceedings of the 2020 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP); 2020; pp. 9241–9250. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abacha, A.B.; Agichtein, E.; Pinter, Y.; Demner-Fushman, D. Overview of the medical question answering task at TREC 2017 LiveQA. In Proceedings of the TREC; 2017; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Abacha, A.B.; Mrabet, Y.; Sharp, M.; Goodwin, T.R.; Shooshan, S.E.; Demner-Fushman, D. Bridging the gap between consumers’ medication questions and trusted answers. In MEDINFO 2019: Health and Wellbeing e-Networks for All; IOS Press, 2019; pp. 25–29.

- Singh, S.; Romanou, A.; Fourrier, C.; Adelani, D.I.; Ngui, J.G.; Vila-Suero, D.; Limkonchotiwat, P.; Marchisio, K.; Leong, W.Q.; Susanto, Y.; et al. Global mmlu: Understanding and addressing cultural and linguistic biases in multilingual evaluation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.03304 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Fang, Z.; Singla, Y.; Dredze, M. Benchmarking Large Language Models on Answering and Explaining Challenging Medical Questions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.18060 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Fu, J.; Tiwari, P.; Wan, X.; Wang, B. Huatuo-26m, a large-scale chinese medical qa dataset. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.01526 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Su, T.; Liu, J.; Lv, C.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; et al. C-eval: A multi-level multi-discipline chinese evaluation suite for foundation models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Cui, R.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y.; Saied, A.; Chen, W.; Duan, N. Agieval: A human-centric benchmark for evaluating foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.06364 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Mishra, S.; Xia, T.; Qiu, L.; Chang, K.W.; Zhu, S.C.; Tafjord, O.; Clark, P.; Kalyan, A. Learn to explain: Multimodal reasoning via thought chains for science question answering. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 2507–2521. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Ye, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Xiong, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, W.; et al. Xiezhi: An ever-updating benchmark for holistic domain knowledge evaluation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2024; Vol. 38, pp. 18099–18107. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, D.; Shen, Z.; Chen, B.; Chen, L.; Yu, K. Scieval: A multi-level large language model evaluation benchmark for scientific research. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2024; Vol. 38, pp. 19053–19061. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Deng, C. Bioinfo-Bench: A Simple Benchmark Framework for LLM Bioinformatics Skills Evaluation. bioRxiv, 2023; 2023–10. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P.; Cowhey, I.; Etzioni, O.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A.; Schoenick, C.; Tafjord, O. Think you have solved question answering? try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.05457 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Rao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yang, Y. Predicting retrosynthetic reactions using self-corrected transformer neural networks. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2019, 60, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetko, I.V.; Karpov, P.; Van Deursen, R.; Godin, G. State-of-the-art augmented NLP transformer models for direct and single-step retrosynthesis. Nature communications 2020, 11, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Lee, D.; Kwon, Y.; Park, M.S.; Choi, Y.S. Valid, plausible, and diverse retrosynthesis using tied two-way transformers with latent variables. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2021, 61, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwaller, P.; Vaucher, A.C.; Laino, T.; Reymond, J.L. Prediction of chemical reaction yields using deep learning. Machine learning: science and technology 2021, 2, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, V.; Venkatasubramanian, V. Predicting chemical reaction outcomes: A grammar ontology-based transformer framework. AIChE Journal 2021, 67, e17190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Xiao, X.; Xu, T.; Rong, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhao, P. Molecular graph enhanced transformer for retrosynthesis prediction. Neurocomputing 2021, 457, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Coley, C.W. Permutation invariant graph-to-sequence model for template-free retrosynthesis and reaction prediction. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2022, 62, 3503–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucak, U.V.; Ashyrmamatov, I.; Ko, J.; Lee, J. Retrosynthetic reaction pathway prediction through neural machine translation of atomic environments. Nature communications 2022, 13, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniato, A.; Vaucher, A.C.; Schwaller, P.; Laino, T. Enhancing diversity in language based models for single-step retrosynthesis. Digital Discovery 2023, 2, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.; Vaucher, A.C.; Byekwaso, A.; Schwaller, P.; Toniato, A.; Laino, T. Unbiasing retrosynthesis language models with disconnection prompts. ACS Central Science 2023, 9, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, T.; Irwin, J.J. ZINC 15–ligand discovery for everyone. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2015, 55, 2324–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, J.J.; Shoichet, B.K. ZINC- a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2005, 45, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.M. Extraction of chemical structures and reactions from the literature. PhD thesis, 2012.

- Hu, W.; Fey, M.; Ren, H.; Nakata, M.; Dong, Y.; Leskovec, J. Ogb-lsc: A large-scale challenge for machine learning on graphs. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.09430 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, C.; Yang, M.; Zheng, S.; Ke, G.; Luo, S.; Cai, T.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; He, D. First place solution of kdd cup 2021 & ogb large-scale challenge graph prediction track. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.08279 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, S.; Gomez-Bombarelli, R. GEOM, energy-annotated molecular conformations for property prediction and molecular generation. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaini, D.; Huang, S.; Cunha, J.A.; Li, Z.; Moisescu-Pareja, G.; Dymov, O.; Maddrell-Mander, S.; McLean, C.; Wenkel, F.; Müller, L.; et al. Towards foundational models for molecular learning on large-scale multi-task datasets. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.04292 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zdrazil, B.; Felix, E.; Hunter, F.; Manners, E.J.; Blackshaw, J.; Corbett, S.; de Veij, M.; Ioannidis, H.; Lopez, D.M.; Mosquera, J.F.; et al. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic acids research 2024, 52, D1180–D1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Guo, A.C.; Lo, E.J.; Marcu, A.; Grant, J.R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Sayeeda, Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic acids research 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddigkeit, L.; Van Deursen, R.; Blum, L.C.; Reymond, J.L. Enumeration of 166 billion organic small molecules in the chemical universe database GDB-17. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2012, 52, 2864–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jeliazkova, N.; Chupakhin, V.; Golib-Dzib, J.F.; Engkvist, O.; Carlsson, L.; Wegner, J.; Ceulemans, H.; Georgiev, I.; Jeliazkov, V.; et al. ExCAPE-DB: an integrated large scale dataset facilitating Big Data analysis in chemogenomics. Journal of cheminformatics 2017, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Ramsundar, B.; Feinberg, E.N.; Gomes, J.; Geniesse, C.; Pappu, A.S.; Leswing, K.; Pande, V. MoleculeNet: a benchmark for molecular machine learning. Chemical science 2018, 9, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hwang, J.; Adams, K.; Liu, Z.; Nan, B.; Stenfors, B.; Du, Y.; Chauhan, J.; Wiest, O.; Isayev, O.; et al. Learning Over Molecular Conformer Ensembles: Datasets and Benchmarks. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N.; Fiscato, M.; Segler, M.H.; Vaucher, A.C. GuacaMol: benchmarking models for de novo molecular design. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2019, 59, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polykovskiy, D.; Zhebrak, A.; Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Golovanov, S.; Tatanov, O.; Belyaev, S.; Kurbanov, R.; Artamonov, A.; Aladinskiy, V.; Veselov, M.; et al. Molecular sets (MOSES): a benchmarking platform for molecular generation models. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11, 565644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Wu, Z.; Yi, J.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Yin, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, A.; et al. ADMETlab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, W5–W14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ektefaie, Y.; Shen, A.; Bykova, D.; Marin, M.; Zitnik, M.; Farhat, M. Evaluating generalizability of artificial intelligence models for molecular datasets. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Xie, Y.; Liu, M.; Dickerson, K.; Deng, C.; Nakata, M.; Ji, S. Molecule3d: A benchmark for predicting 3d geometries from molecular graphs. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.01717 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rives, A.; Meier, J.; Sercu, T.; Goyal, S.; Lin, Z.; Liu, J.; Guo, D.; Ott, M.; Zitnick, C.L.; Ma, J.; et al. Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2016239118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.M.; Liu, J.; Verkuil, R.; Meier, J.; Canny, J.; Abbeel, P.; Sercu, T.; Rives, A. MSA transformer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 8844–8856. [Google Scholar]

- Somnath, V.R.; Bunne, C.; Krause, A. Multi-scale representation learning on proteins. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 25244–25255. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, J.; Rao, R.; Verkuil, R.; Liu, J.; Sercu, T.; Rives, A. Language models enable zero-shot prediction of the effects of mutations on protein function. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 29287–29303. [Google Scholar]

- Elnaggar, A.; Heinzinger, M.; Dallago, C.; Rehawi, G.; Wang, Y.; Jones, L.; Gibbs, T.; Feher, T.; Angerer, C.; Steinegger, M.; et al. Prottrans: Toward understanding the language of life through self-supervised learning. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2021, 44, 7112–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Zhang, S.; Wu, L.; Xia, H.; Ju, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, J.; Deng, P.; et al. Pre-training co-evolutionary protein representation via a pairwise masked language model. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.15527 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, S.; Baek, M.; Madan, U.; Horvitz, E. Toward more general embeddings for protein design: Harnessing joint representations of sequence and structure. bioRxiv, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes, N.; Ofer, D.; Peleg, Y.; Rappoport, N.; Linial, M. ProteinBERT: a universal deep-learning model of protein sequence and function. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2102–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Combs, S.A.; Brand, R.; Calvo, M.R.; Xu, P.; Price, G.; Golovach, N.; Salawu, E.O.; Wise, C.J.; Ponnapalli, S.P.; et al. Lm-gvp: an extensible sequence and structure informed deep learning framework for protein property prediction. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, L.; Xin, J.; Li, Q.; Wu, L.; Deng, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Kong, L. Retrieved sequence augmentation for protein representation learning. bioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Bi, Z.; Liang, X.; Cheng, S.; Hong, H.; Deng, S.; Lian, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H. Ontoprotein: Protein pretraining with gene ontology embedding. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11147 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; dos Santos Costa, A.; Fazel-Zarandi, M.; Sercu, T.; Candido, S.; et al. Language models of protein sequences at the scale of evolution enable accurate structure prediction. BioRxiv 2022, 2022, 500902. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Shuang-Wei, H.; Yu, H.; Jin, X.; Gong, Z.; Chen, H. Multi-level protein structure pre-training via prompt learning. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bian, C.; Yu, Y. Protein representation learning via knowledge enhanced primary structure modeling. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.13154 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, W.; Xue, Z.; Wang, Y. Deciphering the protein landscape with ProtFlash, a lightweight language model. Cell Reports Physical Science 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Lozano, A.; Chenthamarakshan, V.; Das, P.; Tang, J. Enhancing protein language model with structure-based encoder and pre-training. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2023-Machine Learning for Drug Discovery workshop; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Han, C.; Zhou, Y.; Shan, J.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, F. Saprot: Protein language modeling with structure-aware vocabulary. bioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Notin, P.; Weitzman, R.; Marks, D.; Gal, Y. Proteinnpt: Improving protein property prediction and design with non-parametric transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 33529–33563. [Google Scholar]

- Outeiral, C.; Deane, C.M. Codon language embeddings provide strong signals for use in protein engineering. Nature Machine Intelligence 2024, 6, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Yu, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. Pre-training Sequence, Structure, and Surface Features for Comprehensive Protein Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K.; Long, S.; Lu, T.; Yang, J.; Dai, X.; Zhang, M.; Nie, Z.; Ma, W.Y.; Zhou, H. ESM All-Atom: Multi-Scale Protein Language Model for Unified Molecular Modeling. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, M.; Zhuang, X.; Li, X.; Gong, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, J.; Ding, K.; et al. Knowledge-aware Reinforced Language Models for Protein Directed Evolution. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning.

- Hayes, T.; Rao, R.; Akin, H.; Sofroniew, N.J.; Oktay, D.; Lin, Z.; Verkuil, R.; Tran, V.Q.; Deaton, J.; Wiggert, M.; et al. Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model. bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Madani, A.; McCann, B.; Naik, N.; Keskar, N.S.; Anand, N.; Eguchi, R.R.; Huang, P.S.; Socher, R. Progen: Language modeling for protein generation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.03497 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferruz, N.; Schmidt, S.; Höcker, B. A deep unsupervised language model for protein design. BioRxiv, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Das, P.; Chenthamarakshan, V.; Chen, P.Y.; Melnyk, I.; Shen, Y. Fold2Seq: A joint sequence (1D)-Fold (3D) embedding-based generative model for protein design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 1261–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Munsamy, G.; Lindner, S.; Lorenz, P.; Ferruz, N. ZymCTRL: a conditional language model for the controllable generation of artificial enzymes. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Machine Learning in Structural Biology Workshop; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, S.; Bepler, T. Few Shot Protein Generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.01168 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hesslow, D.; Zanichelli, N.; Notin, P.; Poli, I.; Marks, D. Rita: a study on scaling up generative protein sequence models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.05789 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shuai, R.W.; Ruffolo, J.A.; Gray, J.J. Generative language modeling for antibody design. BioRxiv, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Deng, Y.; Xue, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, F.; Gu, Q. Structure-informed language models are protein designers. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 42317–42338. [Google Scholar]

- Sgarbossa, D.; Lupo, U.; Bitbol, A.F. Generative power of a protein language model trained on multiple sequence alignments. Elife 2023, 12, e79854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Vecchietti, L.F.; Jung, H.; Ro, H.; Cha, M.; Kim, H.M. Protein sequence design in a latent space via model-based reinforcement learning. OpenReview 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzinger, M.; Weissenow, K.; Sanchez, J.G.; Henkel, A.; Steinegger, M.; Rost, B. Prostt5: Bilingual language model for protein sequence and structure. bioRxiv. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Geng, Y.a.; Gong, J.; Li, S.; Bei, Z.; Tan, X.; Wang, B.; Zeng, X.; et al. xTrimoPGLM: unified 100B-scale pre-trained transformer for deciphering the language of protein. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.06199 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, Y.; Roda, S.; Guallar, V.; Molina, A. Efficient and accurate sequence generation with small-scale protein language models. bioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.K.; Wei, K.Y. Generative Antibody Design for Complementary Chain Pairing Sequences through Encoder-Decoder Language Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.02748 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, E.; Ruffolo, J.A.; Weinstein, E.N.; Naik, N.; Madani, A. Progen2: exploring the boundaries of protein language models. Cell systems 2023, 14, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternke, M.; Karpiak, J. ProteinRL: Reinforcement learning with generative protein language models for property-directed sequence design. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023 Generative AI and Biology (GenBio) Workshop; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Truong Jr, T.; Bepler, T. Poet: A generative model of protein families as sequences-of-sequences. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 77379–77415. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, N.C.; Berenberg, D.; Zadorozhny, K.; Kleinhenz, J.; Lafrance-Vanasse, J.; Hotzel, I.; Wu, Y.; Ra, S.; Bonneau, R.; Cho, K.; et al. Protein discovery with discrete walk-jump sampling. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.12360 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, H.; Davuluri, R.V. DNABERT: pre-trained Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers model for DNA-language in genome. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Y.; Ma, H.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Huang, J. MoDNA: motif-oriented pre-training for DNA language model. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM international conference on bioinformatics, computational biology and health informatics, 2022, pp. 1–5.

- Gankin, D.; Karollus, A.; Grosshauser, M.; Klemon, K.; Hingerl, J.; Gagneur, J. Species-aware DNA language modeling. bioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla-Torre, H.; Gonzalez, L.; Mendoza-Revilla, J.; Carranza, N.L.; Grzywaczewski, A.H.; Oteri, F.; Dallago, C.; Trop, E.; de Almeida, B.P.; Sirelkhatim, H.; et al. The nucleotide transformer: Building and evaluating robust foundation models for human genomics. BioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, E.; Poli, M.; Faizi, M.; Thomas, A.; Wornow, M.; Birch-Sykes, C.; Massaroli, S.; Patel, A.; Rabideau, C.; Bengio, Y.; et al. Hyenadna: Long-range genomic sequence modeling at single nucleotide resolution. Advances in neural information processing systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, V.; Kuratov, Y.; Petrov, M.; Shmelev, A.; Shepelin, D.; Chekanov, N.; Kardymon, O.; Burtsev, M. Gena-lm: A family of open-source foundational models for long dna sequences. bioRxiv. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Theodoris, C.V.; Xiao, L.; Chopra, A.; Chaffin, M.D.; Al Sayed, Z.R.; Hill, M.C.; Mantineo, H.; Brydon, E.M.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, X.S.; et al. Transfer learning enables predictions in network biology. Nature 2023, 618, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, W.; Jiang, R.; Wong, W.H. EpiGePT: a Pretrained Transformer model for epigenomics. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Malusare, A.; Kothandaraman, H.; Tamboli, D.; Lanman, N.A.; Aggarwal, V. Understanding the natural language of DNA using encoder–decoder foundation models with byte-level precision. Bioinformatics Advances 2024, 4, vbae117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; et al. DNAGPT: A generalized pre-trained tool for versatile DNA sequence analysis tasks. Preprint at https://doi. org/10.48550/arXiv 2023, 2307. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, E.; Poli, M.; Durrant, M.G.; Thomas, A.W.; Kang, B.; Sullivan, J.; Ng, M.Y.; Lewis, A.; Patel, A.; Lou, A.; et al. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. BioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, S.; Chen, P.; Liu, J.; Huo, K.G.; Han, L. Exploring Genomic Large Language Models: Bridging the Gap between Natural Language and Gene Sequences. bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Avsec, Ž.; Agarwal, V.; Visentin, D.; Ledsam, J.R.; Grabska-Barwinska, A.; Taylor, K.R.; Assael, Y.; Jumper, J.; Kohli, P.; Kelley, D.R. Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions. Nature methods 2021, 18, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Chen, C.; Shan, W.; Ding, P.; Luo, L. iEnhancer-BERT: a novel transfer learning architecture based on DNA-language model for identifying enhancers and their strength. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing. Springer; 2022; pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zeng, X.; Pang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z.; Dai, Y.; Su, R.; Zou, Q.; et al. iDNA-ABF: multi-scale deep biological language learning model for the interpretable prediction of DNA methylations. Genome biology 2022, 23, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Lin, W.; Luo, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J. iEnhancer-ELM: improve enhancer identification by extracting position-related multiscale contextual information based on enhancer language models. Bioinformatics Advances 2023, 3, vbad043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, G.; Li, D. miProBERT: identification of microRNA promoters based on the pre-trained model BERT. Briefings in bioinformatics 2023, 24, bbad093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jin, J.; Long, W.; Wei, L. PLPMpro: Enhancing promoter sequence prediction with prompt-learning based pre-trained language model. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2023, 164, 107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zang, Z.; Xu, Y.; He, H.; Liu, Z.; Song, Z.; Zheng, J.S.; Li, S.Z. FGBERT: Function-Driven Pre-trained Gene Language Model for Metagenomics. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.16901 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Benegas, G.; Batra, S.S.; Song, Y.S. DNA language models are powerful predictors of genome-wide variant effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2311219120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagin, M.; Brace, A.; Hippe, K.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Bohorquez, C.O.; Clyde, A.; Kale, B.; Perez-Rivera, D.; Ma, H.; et al. GenSLMs: Genome-scale language models reveal SARS-CoV-2 evolutionary dynamics. The International Journal of High Performance Computing Applications 2023, 37, 683–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benegas, G.; Albors, C.; Aw, A.J.; Ye, C.; Song, Y.S. GPN-MSA: an alignment-based DNA language model for genome-wide variant effect prediction. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Shan, W.; Chen, C.; Ding, P.; Luo, L. Improving language model of human genome for DNA–protein binding prediction based on task-specific pre-training. Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Sciences 2023, 15, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Cornman, A.L.; Kellogg, E.H.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Girguis, P.R. Genomic language model predicts protein co-regulation and function. Nature communications 2024, 15, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Yang, Y. Self-supervised learning on millions of pre-mRNA sequences improves sequence-based RNA splicing prediction. bioRxiv 2023, 2023–01. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lang, M.; Jiang, J.; Gao, Z.; Xu, F.; Litfin, T.; Chen, K.; Singh, J.; Huang, X.; Song, G.; et al. Multiple sequence alignment-based RNA language model and its application to structural inference. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, e3–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ge, F.; Li, F.; Yang, X.; Song, J.; Yu, D.J. Prediction of multiple types of RNA modifications via biological language model. IEEE/ACM transactions on computational biology and bioinformatics 2023, 20, 3205–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gu, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Ji, X.; Ke, G.; Wen, H. UNI-RNA: universal pre-trained models revolutionize RNA research. bioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Penić, R.J.; Vlašić, T.; Huber, R.G.; Wan, Y.; Šikić, M. Rinalmo: General-purpose rna language models can generalize well on structure prediction tasks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.00043 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Bian, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Mumtaz, S.; Kong, L.; Xiong, H. Multi-purpose RNA language modelling with motif-aware pretraining and type-guided fine-tuning. Nature Machine Intelligence 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strausberg, R.L.; Feingold, E.A.; Klausner, R.D.; Collins, F.S. The mammalian gene collection. Science 1999, 286, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Dai, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhao, S.; Samuels, D.C.; Shyr, Y. Improvements and impacts of GRCh38 human reference on high throughput sequencing data analysis. Genomics 2017, 109, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Edwards, M.D.; Liu, G.; Gifford, D.K. Convolutional neural network architectures for predicting DNA–protein binding. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, i121–i127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Troyanskaya, O.G. Predicting effects of noncoding variants with deep learning–based sequence model. Nature methods 2015, 12, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, G.P.; et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreos, R.; Ambrosini, G.; Cavin Périer, R.; Bucher, P. EPD and EPDnew, high-quality promoter resources in the next-generation sequencing era. Nucleic acids research 2013, 41, D157–D164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzén, O.; Gan, L.M.; Björkegren, J.L. PanglaoDB: a web server for exploration of mouse and human single-cell RNA sequencing data. Database 2019, 2019, baz046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusk, N. Sequence-based prediction of variants’ effects. Nature Methods 2018, 15, 571–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolchik, D.; Baertsch, R.; Diekhans, M.; Furey, T.S.; Hinrichs, A.; Lu, Y.; Roskin, K.M.; Schwartz, M.; Sugnet, C.W.; Thomas, D.J.; et al. The UCSC genome browser database. Nucleic acids research 2003, 31, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; et al. Introducing the bacterial and viral bioinformatics resource center (BV-BRC): a resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamesch, P.; Berardini, T.Z.; Li, D.; Swarbreck, D.; Wilks, C.; Sasidharan, R.; Muller, R.; Dreher, K.; Alexander, D.L.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic acids research 2012, 40, D1202–D1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Singh, J.; Litfin, T.; Zhan, J.; Paliwal, K.; Zhou, Y. RNAcmap: a fully automatic pipeline for predicting contact maps of RNAs by evolutionary coupling analysis. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 3494–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, E.P.; et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, D.; Upton, C. Viral Genome DataBase: storing and analyzing genes and proteins from complete viral genomes. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 484–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsonis, P.; Lichtarge, O. CAGI5: Objective performance assessments of predictions based on the Evolutionary Action equation. Human mutation 2019, 40, 1436–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlacher, M.; Cantini, G.; Hesse, J.; Schinke, P.; Goedert, N.; Londhe, S.; Moyon, L.; Marsico, A. A systematic benchmark of machine learning methods for protein–RNA interaction prediction. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2023, 24, bbad307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T. Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1910.03771 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rasley, J.; Rajbhandari, S.; Ruwase, O.; He, Y. Deepspeed: System optimizations enable training deep learning models with over 100 billion parameters. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2020; pp. 3505–3506. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj, P.; Xiong, C.; Ke, G.; Liu, X.; He, D.; Tiwary, S.; Liu, T.Y.; Bennett, P.; Song, X.; Gao, J. Metro: Efficient denoising pretraining of large scale autoencoding language models with model generated signals. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.06644 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; Puri, R.; LeGresley, P.; Casper, J.; Catanzaro, B. Megatron-lm: Training multi-billion parameter language models using model parallelism. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.08053 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sachan, D.S.; Patwary, M.; Shoeybi, M.; Kant, N.; Ping, W.; Hamilton, W.L.; Catanzaro, B. End-to-end training of neural retrievers for open-domain question answering. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.00408 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, A.; Puri, R.; Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; Catanzaro, B. Large scale multi-actor generative dialog modeling. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.06114 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santhanam, S.; Ping, W.; Puri, R.; Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; Catanzaro, B. Local knowledge powered conversational agents. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.10150 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Patwary, M.; Shoeybi, M.; Puri, R.; Fung, P.; Anandkumar, A.; Catanzaro, B. MEGATRON-CNTRL: Controllable story generation with external knowledge using large-scale language models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.00840 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Ping, W.; McAfee, L.; Xu, P.; Li, B.; Shoeybi, M.; Catanzaro, B. Instructretro: Instruction tuning post retrieval-augmented pretraining. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.07713 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, J.; Frostig, R.; Hawkins, P.; Johnson, M.J.; Leary, C.; Maclaurin, D.; Zhang, Q. JAX: Composable Transformations of Python+ NumPy Programs. https://github.com/google/jax, 2018. Accessed: 2024-02-07.

- Li, S.; Liu, H.; Bian, Z.; Fang, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; You, Y. Colossal-ai: A unified deep learning system for large-scale parallel training. In Proceedings of the 52nd International Conference on Parallel Processing, 2023, pp. 766–775.

- Tang, T.; Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Luo, W.; Qin, Z.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Cheng, X.; Guo, G.; et al. LLMBox: A Comprehensive Library for Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.05563 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; Casas, D.d.l.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06825 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Workshop, B.; Scao, T.L.; Fan, A.; Akiki, C.; Pavlick, E.; Ilić, S.; Hesslow, D.; Castagné, R.; Luccioni, A.S.; Yvon, F.; et al. Bloom: A 176b-parameter open-access multilingual language model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.05100 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, D.; Chia, Y.K.; Majumder, N.; Poria, S. Flacuna: Unleashing the problem solving power of vicuna using flan fine-tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.02053 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, E.; Pang, B.; Hayashi, H.; Tu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Savarese, S.; Xiong, C. Codegen: An open large language model for code with multi-turn program synthesis. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.13474 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Allal, L.B.; Zi, Y.; Muennighoff, N.; Kocetkov, D.; Mou, C.; Marone, M.; Akiki, C.; Li, J.; Chim, J.; et al. Starcoder: may the source be with you! arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.06161 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Azerbayev, Z.; Schoelkopf, H.; Paster, K.; Santos, M.D.; McAleer, S.; Jiang, A.Q.; Deng, J.; Biderman, S.; Welleck, S. Llemma: An open language model for mathematics. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.10631 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.03300 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, G.; Zhang, C.; Ye, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; Peng, Y.; Lin, H.; Wu, C. Hybridflow: A flexible and efficient rlhf framework. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.19256 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Liu, T.; Wright, L.; Constable, W.; Gu, A.; Huang, C.C.; Zhang, I.; Feng, W.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; et al. TorchTitan: One-stop PyTorch native solution for production ready LLM pre-training. arXiv 2024, arXiv:cs.CL/2410.06511]. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 |

| Row | Topic | Query for Searching Articles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical Large Language Models | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Large Language Model’ OR ‘Generative AI’ OR ‘Transformer Models’) AND (‘Medical Data’ OR ‘Electronic Health Records’ OR ‘EHR’) |

| 2 | Biology Large Language Models | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Large Language Model’) AND (‘Biology Data’ OR ‘Genomics’ OR ‘Protein Data’) AND (‘Sequence Representation’ OR ‘Function Prediction’ OR ‘Evolution Modeling’) |

| 3 | Chemistry Large Language Models | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Transformer’ OR ‘BERT’) AND (‘Molecular Data’ OR ‘Chemical Structures’) AND (‘Molecule Property Prediction’ OR ‘Reaction Prediction’ OR ‘Molecule Design’) |

| 4 | Datasets and Benchmarks (General) | (‘Datasets’ OR ‘Benchmarks’) AND (‘LLM Evaluation’ OR ‘Scientific LLMs’ OR ‘Biological Data’ OR ‘Chemical Data’ OR ‘Medical Data’) |

| 5 | LLMs for Molecule Property Prediction | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Large Language Model’) AND (‘Molecular Property’ OR ‘Chemical Properties’) AND (‘Prediction’ OR ‘Transformer-based Analysis’) |

| 6 | LLMs for Interaction Prediction | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Large Language Model’) AND (‘Protein-Ligand Interaction’ OR ‘DNA-Protein Binding’ OR ‘RNA Interaction’) |

| 7 | LLMs for Molecule Generation | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Generative Models’ OR ‘Molecule Generation’) AND (‘Drug Design’ OR ‘Protein Engineering’ OR ‘DNA Synthesis’) |

| 8 | LLMs for Reaction Prediction | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Reaction Prediction’) AND (‘Transformer Models’ OR ‘Molecular Modeling’) AND (‘Chemical Reactions’ OR ‘Organic Chemistry’) |

| 9 | Protein Sequence Representation | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Large Language Model’) AND (‘Protein Sequence’ OR ‘Sequence Representation’) AND (‘Transformer’ OR ‘Masked Language Modeling’) |

| 10 | Protein Sequence Generation | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Protein Design’) AND (‘Sequence Generation’ OR ‘Generative Modeling’) |

| 11 | Genomic Data Modeling | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Large Language Model’) AND (‘Genomic Data’ OR ‘DNA Modeling’) AND (‘Sequence-to-Function’ OR ‘Gene Prediction’) |

| 12 | Function Prediction | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Transformer Model’) AND (‘Gene Function Prediction’ OR ‘Protein Function Prediction’) |

| 13 | Variants and Evolution Prediction | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Evolution Modeling’) AND (‘Variants’ OR ‘Mutations’) |

| 14 | DNA-Protein Interaction | (‘LLM’ OR ‘Transformer’) AND (‘DNA-Protein Interaction’ OR ‘Binding Affinity’) |

| 15 | RNA Prediction | (‘LLM’ OR ‘RNA Modeling’) AND (‘Sequence Prediction’ OR ‘RNA Binding Proteins’) |

| Model | # Parameter | Evaluation Metrics | Core Model | Pretraining Datasets | Language | Evaluation Tasks | Open-source | Model Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClinicalBERT | 110M | AUROC AUPRC RP80 | BERT | MIMIC-III | English | predicts 30-day readmission using discharge summaries | ✓ | https://github.com/kexinhuang12345/clinicalBERT |

| Gatortron | 8.9B | Pearson , Accuracy, F1 score ,Exact Match | BERT | MIMIC-III, PubMed, etc. | English | Semantic textual similarity and Question answering | ✓ | https://github.com/uf-hobi-informatics-lab/GatorTron |

| GatorTronGPT | 5B, 20B | Precision, Recall, and F1 | GPT | Pubmed, and Custom Data | English | Clinical concept extraction, and Question answering | ✓ | https://github.com/uf-hobi-informatics-lab/GatorTronGPT |

| MEDITRON-70B | 7B, 70B | Accuracy | LLAMA2 | Pubmed, PMC, etc. | English | Question answering | ✓ |

https://github.com/epfLLM/meditron, https://huggingface.co/epfl-llm/ |

| Meerkat-7B | 7B | Accuracy | Mistral | Custom Data | English | Multiple-choice QA | ✓ | https://huggingface.co/dmis-lab/meerkat-7b-v1.0 |

| CLINICALGPT | 7B | Win, Lose, and Tie | BLOOM | cMedQA2, MedDialog, etc. | Chinese | Medical question answering | ✗ | - |

| Qilin-Med | 7B | Accuracy, BLEU, and ROUGE | Baichuan | ChiMed | Chinese | medical exam and practice question | ✓ | https://github.com/williamliujl/Qilin-Med |

| ChatDoctor | 7B | Precision, Recall, and F1 | LLAMA | HealthCareMagic | English | question answering | ✓ | https://github.com/Kent0n-Li/ChatDoctor |

| HuaTuo | 7B,69B | Safety, Usability, and Smoothness | LLaMA | Custom Data | Chinese | question answering | ✓ | https://github.com/SCIR-HI/Huatuo-Llama-Med-Chinese |

| HuatuoGPT | 7B | BLEU, GLEU, ROUGE, and Distinct | BLOOM | Custom Data | Chinese | Efficacy,Medical Expenses, and Consequences Description | ✓ | https://github.com/FreedomIntelligence/HuatuoGPT |

| Baize | 7B | ARC | LLAMA | MedQuAD | English | question answering | ✓ | https://github.com/project-baize/baize-chatbot |

| Zhongjing | 13B | Safety, Prof, Fluency, and Length | LLAMA | Medical Books, Wiki, etc. | Chinese | single-turn and multi-turn dialogue capabilities of the Chine | ✓ | https://github.com/SupritYoung/Zhongjing |

| PMC-LLaMA | 13B | Accuracy | LLAMA | PMC, Medical books, etc | English | Medical question answering | ✓ | https://github.com/chaoyi-wu/PMC-LLaMA |

| CPLLM | 2.7B, 13B | PR-AUC ROC-AUC | LLAMA-2 | eICU-CRD, MIMIC-IV | English | disease prediction | ✓ | https://github.com/nadavlab/CPLLM |

| Med-PaLM 2 | 340B | Accuracy | PaLM2 | MultiMedQA | English | Long-form question | ✗ | - |

| Clinical Camel | 13B, 70B | Zero-shot five-shot |

LLAMA-2 | PubMed | English | Long-form question | ✗ | - |

| DoctorGLM | 6.2B | - | ChatGLM | CMD., HealthCareMagic, etc. | Chinese | Long-form question | ✓ | https://github.com/xionghonglin/DoctorGLM |

| BianQue | 6.2B | BLEU | ChatGLM | BianQueCorpus | Chinese | chain of questioning (CoQ) | ✓ | https://github.com/scutcyr/BianQue |

| Medical mT5 | 738M, 3B | Zero-shot F1 scores | T5 | Custom Data | English, French, Italian and Spanish | Named Entity Recognition, Argument Mining, and Question Answering | ✓ | https://huggingface.co/DHEIVER/Medical-mT5-large |

| Me-LLaMA | 13B, 70B | Accuracy, F1-score | LLAMA | Custom Data | English | Question Answering | ✓ | https://github.com/BIDS-Xu-Lab/ |

| BiMediX | 7B | Accuracy | Mixtral | BiMed1.3M | English and Arabic | Multiple-Choice Question Answering (MCQA)and Question Answering (QA) | ✓ | https://github.com/mbzuai-oryx/BiMediX |

| Model | Reference | #Parameters | Base Model | Pretraining dataset | Open source | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioELMo | [64] | - | ELMo | PubMed | ✓ | https://github.com/mbzuai-oryx/BiMediX |

| BioBERT | [67] | 117M | BERT | PubMed, PMC | ✓ | https://github.com/Andy-jqa/bioelmo |

| BlueBERT | [90] | 117M | BERT | PubMed | ✓ | https://github.com/ncbi-nlp/bluebert |

| BioMegatron | [72] | 345M-1.2B | BERT | PubMed, PMC | ✓ | https://github.com/NVIDIA/NeMo |

| PubMedBERT | [73] | 117M | BERT | PubMed | ✗ | - |

| BioM-BERT | [84] | 235M | BERT | PubMed, PMC | ✓ | https://github.com/BioMedBERT/biomedbert |

| BioLinkBERT | [85] | 110M, 340M | BERT | ioL PubMed | ✓ | https://github.com/michiyasunaga/LinkBERT |

| BioGPT | [86] | 347M | GPT | PubMed | ✓ | https://github.com/microsoft/BioGPT |

| BioMedGPT-LM | [87] | 7B | LLaMA | PMC, arXiv, WIPO | ✓ | https://github.com/PharMolix/OpenBioMed |

| BioinspiredLLM | [88] | 13B | Llama-2 | Biological article | ✓ | https://huggingface.co/lamm-mit/BioinspiredLLM |

| BioMistral | [89] | 7B | Mistral | PMC | ✓ | https://github.com/BioMistral/BioMistral |

| Model | Reference | #Parameters | Base Model | Pretraining dataset | Open source | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBERT | [91,105] | 120M | BERT | Chemical journals | ✓ | https://github.com/jiangfeng1124/ChemRxnExtractor |

| MatSciBERT | [92] | 117M | BERT | Elsevier journals | ✓ | https://github.com/M3RG-IITD/MatSciBERT |

| MaterialsBERT | [293] [93] | ✗ | BERT | Material journals | ✓ | https://huggingface.co/pranav-s/MaterialsBERT |

| PharmGPT | [104] | 13B, 70B | LLaMA | Paper, report, book, etc. | ✗ | - |

| Model | Ref | param | Eval met | Dataset | O-source | Model link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCROP | [120] | N/A | Accuracy | USPTO-50k | ✓ | https://github.com/sysu-yanglab/Self-Corrected-Retrosynthetic-Reaction-Predictor. |

| Tetko et. al | [121] | N/A | Accuracy | USPTO-50k | ✓ | https://github.com/bigchem/synthesis |

| Two-way Transformers | [122] | 34.8 M | Accuracy | USPTO | ✓ | http://github.com/ejklike/tied-twoway-transformer/ |

| Transformer+Regressor | [123] | N/A | USPTO | ✓ | https://rxn4chemistry.github.io/rxn_yields/ | |

| GO-PRO | 98 | 5M | Top-1,2,3 accuracies, BLEU, Syntactic validity, and Character based similarity | Jin’s USPTO and Human Chemists | Upon Request | Upon Request |

| Graph Enhanced Transformer | [125] | N/A | Accuracy | USPTO-50k | ✓ | https://github.com/papercodekl/MolecularGET |

| Graph2SMILES | [126] | N/A | Accuracy | USPTO | ✓ | https://github.com/coleygroup/Graph2SMILES |

| RetroTRAE | [127] | N/A | Accuracy, Tanimoto Coefficient (Tc), and Sørensen–Dice Coefficient (S) | USPTO | ✓ | https://github.com/knu-lcbc/RetroTRAE |

| Toniato et. Al | [128] | 12 M | Accuracy, Round-trip Accuracy, Coverage, and Class diversity | Pistachio Dataset, USPTO-50k |

✓ | https://github.com/rxn4chemistry/rxn_cluster_token_prompt |

| Thakkar et. al | [129] | N/A | Accuracy, Round Trip Accuracy, Disconnection Accuracy, and Reaction Class Diversity | Pistachio Dataset, USPTO, ECReact |

✓ | https://github.com/rxn4chemistry/disconnection_aware_retrosynthesis |

| Model | Reference | #Parameters | Base Model | Pretraining dataset | Open source | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProGen | [171] | 1.2B | GPT | Uniparc SWISS-Prot | ✓ | https://github.com/salesforce/progen |

| ProtGPT2 | [172] | 738M | GPT | Uniref50 | ✓ | https://huggingface.co/nferruz/ProtGPT2 |

| ZymCTRL | [174] | 738M | GPT | BRENDA | ✓ | https://huggingface.co/AI4PD/ZymCTRL |

| RITA | [176] | 1.2B | GPT | UniRef100 | ✗ | |

| IgLM | [177] | 13M | GPT | - | https://github.com/Graylab/IgLM | |

| ProGen2 | [185] | 151M - 6.4B | GPT | Uniref90, BFD30, PDB | ✓ | https://github.com/salesforce/progen |

| ProteinRL | [186] | 764M | GPT | - | ✗ | |

| PoET | [187] | 201M | GPT | - | ✗ | |

| C. Frey et al. | [188] | 9.87M-1.03M | GPT | hu4D5 antibody mutant | ✗ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).