Introduction

LLMs are rapidly being integrated into various aspects of medical practice and research as valuable tools in diagnostics, clinical decision making, clinical support, medical writing, education, and personalized medicine [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In geroscience and longevity medicine [

5], LLM technologies have, for example, been utilized for health monitoring, geriatric assessment and care, psychiatry, and risk assessment; other studies highlight the potential of these and related technologies, such as robotics, more generally, in supporting cognitive health, social interaction, assisted living, and rehabilitation [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Benchmarks for evaluating LLMs have become indispensable to meet the rigorous standards and professionalism required in healthcare and medical research. Existing public benchmarks [

11,

12,

13,

14] focus on assessing LLM performance in general medical and biomedical tasks, primarily using multiple-choice formats. Other datasets assess proficiency in understanding and summarizing medical texts or in disease recognition, relation extraction, and bias recognition [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Only a few benchmarks address medical interventions or treatment recommendations [

21,

22], but these focus on disease-targeting interventions, and, also, not on free-text responses. A major cause of judgement bias is benchmark “contamination”, that is availability of (parts of) the benchmark data to LLMs, in their training data or while searching the internet, rendering novel data specifically valuable.

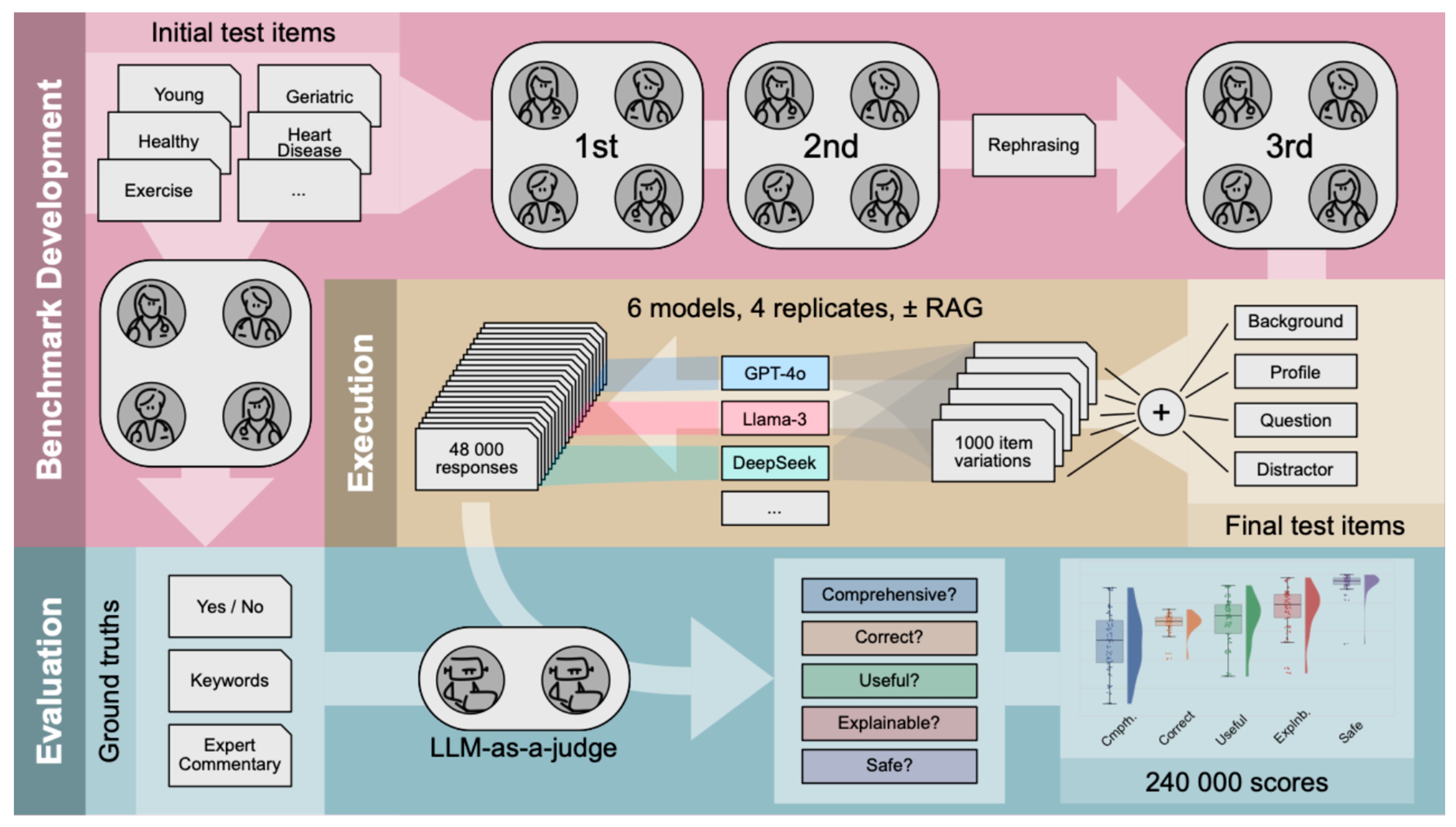

Our benchmark, reviewed and approved by physicians as domain experts, was generated anew and consists of 25 medical profiles (test items), each simulating a user seeking advice regarding well-known longevity interventions. Each test item is presented as an open query. All items consist of multiple modules that can be combined to introduce diversity in syntax, resulting in 1,000 different test cases. To introduce semantic variance in the input, items were varied across two dimensions: according to age groups of individuals and types of interventions. Furthermore, we examined the impact of additional augmented context on LLM performance using Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG).

Both proprietary and open-source LLMs were evaluated across 5 validation requirements, using the LLM-as-a-judge paradigm [

23]: Comprehensiveness (Comprh), Correctness (Correct), Usefulness (Useful), Interpretability/Explainability (Explnb) and Consideration of Toxicity/Safety (Safe). The LLM-as-a-judge was provided with expert commentaries, describing what we believe a good response should entail. Overall, we found that LLMs did not address all requirements equally well. However, instructing models with the requirements induced a moderate increase in model performance, confirming our perspective from last year [

24]. Our results show alignment with studies that assessed similar axes of model performance, such as the work by Zakka et al. [

25], but are based on a statistically powered set of evaluations specifically focused on the domain of longevity medicine and geroscience. We developed a framework that automates LLM-based judgment, considering test-item-specific human-approved ground truths, and integrated it into BioChatter [

26]. The framework is freely available at

https://github.com/biocypher/biochatter and may be used and adapted for future LLM studies.

Methods

Benchmark Dataset and Test Items / User Prompts

We developed a benchmark of 25 test items assessing personalized LLM advice on longevity interventions and then tested the LLMs across the mentioned 5 validation requirements, as defined comprehensively in Supplementary Appendix A; in some evaluation scenarios, these requirements were given as an explicit guide to the LLM-as-a-judge. One of us (HJ) drafted the test items along with the ground truths, which centered around expert commentaries with keywords, describing what is expected from the LLM response, such as the gains and caveats to consider. In this context, the keywords distill the core content of the expert commentaries and function as supplementary input for the LLM-as-a-Judge. Additionally, each query was designed so that a “Yes” or “No” response (binary ground truth) could be assigned, indicating whether an intervention is recommended or not, see Supplementary Appendix B.

Four domain experts (AH, BZ, CB, SF) reviewed the test items and ground truths in three rounds. Initially, subsets of items were reviewed independently, followed by a revision of the full benchmark in the second round. The test items were then structured into standardized modules: background information, biomarker profile, and the final binary question (“Yes” or “No”). To simulate diverse conversational scenarios, variations were created by rephrasing backgrounds and profiles into different formats (short or verbose backgrounds, paragraph-based or list-based profiles), with an additional "distracting statement" - placed at the end of a test case or not, to test the LLM's robustness against irrelevant information. In the third round, all experts re-reviewed the full benchmark. Eight different test cases were thus created from one test item’s modules and used as user prompts. Together with five different system prompts (see below), this modular approach enabled the automated generation of 8 * 5 * 25 = 1,000 test cases from the 25 modular items, see

Figure 1. The structure of a finalized test case and its combinatorial assembly are illustrated in Supplementary

Appendices B and C. All 25 test items are listed in Supplementary Appendix D.

Domain Background and Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

The benchmarking data features clinical biomarker data from various individuals who wish to undertake one or a combination of the following longevity interventions: caloric restriction (n = 6), intermittent fasting (n = 4), exercise (n = 5), a combination of caloric restriction and exercise (n = 4), and the intake of supplements or drugs commonly associated with health effects. The latter are Epicatechin (n = 2), Fisetin (n = 1), Spermidine (n = 1), and Rapamycin (n = 2); see Supplementary Appendix E for background information. Furthermore, the individuals were categorized into the following age groups: young (20–39 years, n = 11), mid-aged (40–60 years, n = 7), and elderly/geriatric (>60 years, n = 7). Five young and mid-aged profiles indicate the presence of the risk for an underlying hormonal disorder (hypothyroidism, cushing syndrome, acromegaly, and polycystic ovarian syndrome [PCOS]) for which longevity interventions should not be the primary recommendation. Additionally, for four “geriatric” profiles, the application of longevity interventions is contraindicated due to age-related musculoskeletal (osteoporosis and sarcopenia) or cardiovascular (coronary artery disease, two cases) diseases, along with their respective comorbidities. These diseases are noted, together with potential differential diagnoses, in the expert commentaries.

To test the effect of RAG on LLM response quality, we appended RAG-based data to the user prompts, for which a vector database was created using QDrant (

https://qdrant.tech/), containing approximately 18,000 open-source scientific research papers with focus on the fields of geroscience and longevity medicine, see Supplementary Appendix F.

System Prompts

We defined five different system prompts with varying complexity that are automatically combined with the user prompts, where the information content of the instructions increases from “Minimal” towards “Requirements-explicit”. “Minimal” prompts the LLM to return, at the end of the answer, either “Yes” or “No”, stating whether the intervention is recommended or not. “Specific” adds that the query relates to longevity medicine, geroscience, aging research and geroprotection. “Role encouraging” additionally integrates a definition of the advisory role that the LLM is expected to assume. “Requirements-specific” further lists the five validation requirements the LLM should fulfill in its response, while “Requirements-explicit” additionally provides the definitions of these requirements. The instructions to the LLM-as-a-judge then included the test case, the response of the LLM being evaluated and the expert annotated ground truths, see

Figure 1, while the binary ground truth was added only in some evaluation scenarios when the LLM-as-a-judge had to evaluate the correctness of a model response; for more information on the system prompts see Supplementary Appendix G.

Models

Proprietary LLMs available in February/March 2025 included GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer) series models (OpenAI), specifically o3-mini (with “reasoning effort” set to medium), GPT-4o and GPT-4o mini, while open-source models selected were Llama 3.2 3B (by Meta) [

27], Qwen 2.5 14B and DeepSeek R1 Distill Llama 70B (DSR Llama 70B for short), which is built based on Llama 3.3 70B. All models were accessed via the appropriate APIs (OpenAI API, Groq, LMStudio). Models were evaluated in the time period February-March 2025. Except for o3-mini, all models were tested using greedy decoding (temperature 0). o3-mini was used with default temperature settings (temperature = 1), as OpenAI offered this model only through an API program which does not allow for custom adjustments of temperature. Motivated by their advanced reasoning capabilities at an acceptable speed, OpenAI’s GPT-4o mini and GPT-4o were pre-selected as candidate judges. To further elucidate the robustness of their judgements, both GPT-4o mini and GPT-4o were used to assess correctness in two evaluation settings: one when given the binary ground truth (standard setting) and one without. We selected GPT-4o mini as the final LLM-as-a-Judge for our experiments because GPT-4o mini’s judgments showed higher alignment with the ground truth in both evaluation settings, while a comparative analysis across all validation requirements revealed that both models showed high interrater reliabilities for Correctness; see Supplementary Appendix H for further information.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Pingouin (0.5.5) [

29], Scikit-learn (1.6.1) [

30] and SciPy (1.15.2) [

31] in Python (version 3.11.2). The mean scores of the models were determined based on the verdicts and compared with each other. To compare model performances across test cases, McNemar’s test was used. Cochran’s Q test was applied for comparisons between model performances grouped across the validation requirements and system prompts. The Chi-square test was used to compare grouped model performances across age groups. P-values were Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. The interrater reliability between GPT-4o mini and GPT-4o was evaluated using Cohen’s Kappa.

Discussion

By testing performance across multiple validation requirements using modular, physician-approved test items, we went beyond the exam-based assessment of LLMs in a reproducible and transparent manner, allowing for the assessment of free-text tasks. We evaluated proprietary and open-source LLMs using a benchmark specifically designed for evaluating intervention recommendations in the fields of geroscience and longevity medicine. Using the LLM-as-a-judge approach, our findings demonstrated that current LLMs must still be used with caution for any unsupervised medical intervention recommendations. Indeed, LLMs showed inconsistent performance across validation requirements, rendering benchmarks that measure single dimensions of model performance insufficient to capture the full complexity of heterogeneous and test-item-specific model capabilities. This demonstrated the complexity of judging LLM responses, justifying a detailed analyses by the automated judging approach described in

Figure 1. However, we must be aware that automated judging suffers severely from the impossibility to systematically check the automated verdicts for their alignment with human judgements; the only exception was correctness, in the scenario where the expert-provided binary ground truth was either matched or not by the response of the LLM (see Supplementary Appendix H). Then again, human judgements are prone to heterogeneity, errors and biases, and it is future research to analyze their correlation with judgements by LLM-as-a-judge more deeply.

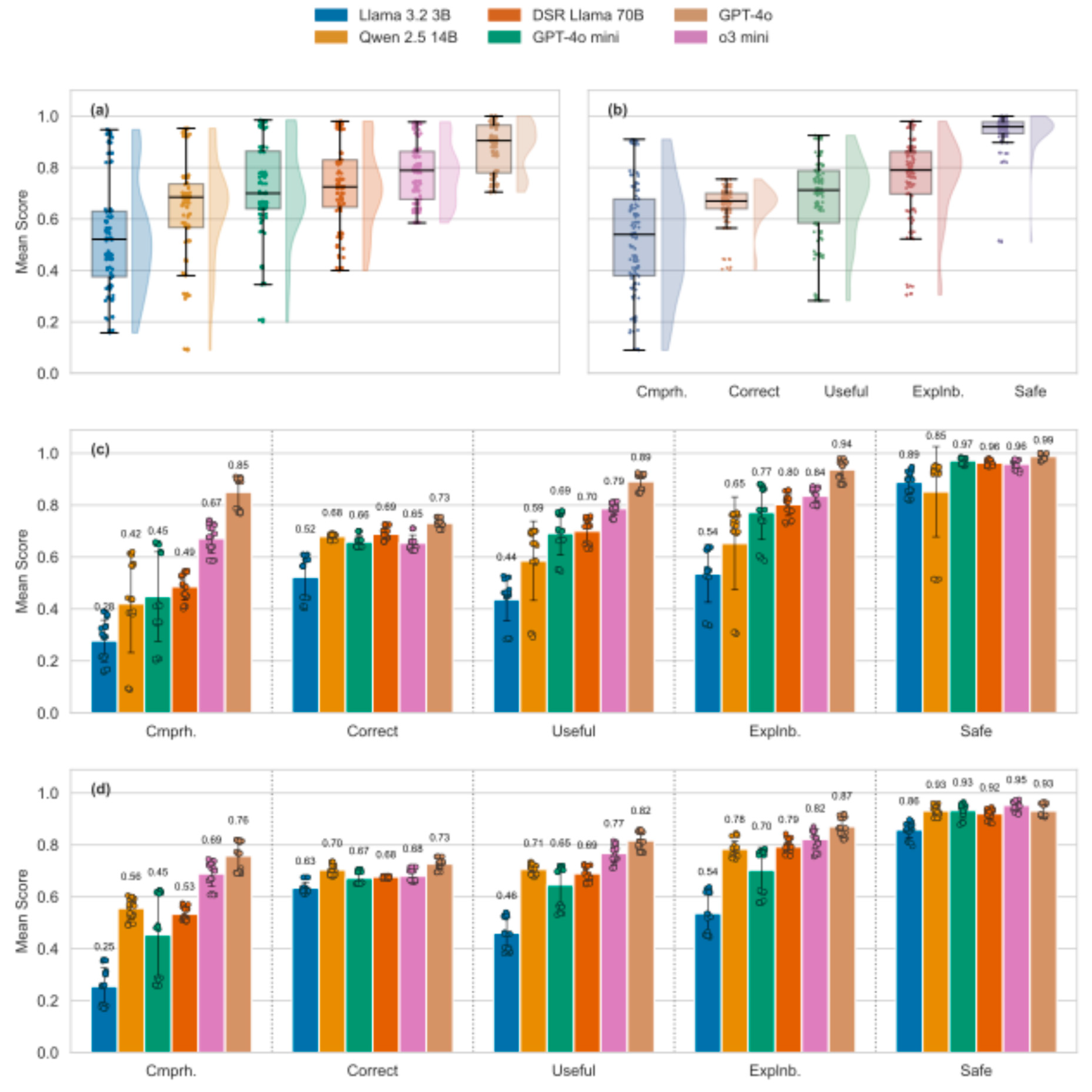

Overall, open-source models tended to perform worse than proprietary models, yet response quality of the latter was mostly considered sufficient, triggering positive verdicts by the LLM-as-a-judge in more than 80% of cases, see

Figure 2. Open-source models struggled particularly in achieving sufficient comprehensiveness. Along these lines, a recent study found that around 90% of research papers criticized the lack of comprehensiveness (defined heterogeneously, yet in alignment with our definition) in LLM-generated medical responses [

32]. However, while a lack of comprehensiveness may mean that LLM outputs fail to reveal knowledge important to the user, comprehensive responses may be less

comprehensible (useful) by overwhelming the user. Moreover, a notable positive aspect was that all models exhibited a high “Consideration of Toxicity/Safety”, such that any lack of comprehensiveness does not tend to imply the recommendation of a harmful intervention. This may reflect an alignment of LLMs with common human values, presumably a consequence of Reinforcement-Learning via Human Feedback (RLHF). From an ethical perspective, safety is fundamental (reflecting the principle of non-maleficence), yet in our application domain, overly cautious model behavior may mean that no intervention is recommended – not even diet or exercise; this may not be in the interest of the user. Also, while comprehensive responses may pose cognitive challenges for users, a lack of comprehensiveness may harm informed decision-making and thus the principle of autonomy. Ethically, comprehensiveness must thus be balanced with comprehensibility; it cannot be neglected without compromising user empowerment [

33,

34].

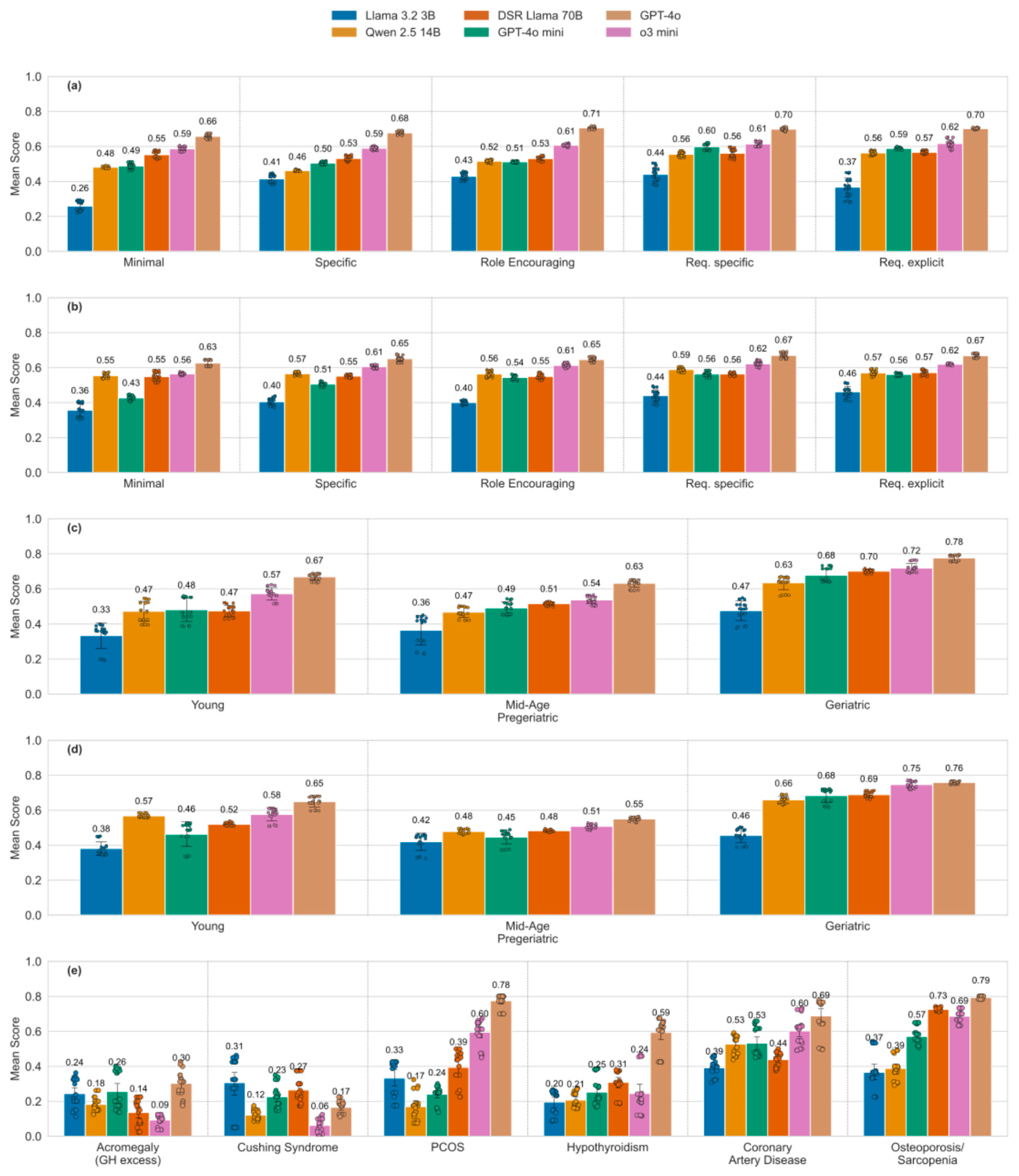

Many studies have already demonstrated that LLM responses can be highly dependent on prompt design and on the ordering of information within a prompt [

35,

36], posing a risk in healthcare in particular. In our case, even small modifications in test case structure (e.g., increased verbosity) led to performance differences across prompt settings. However, LLMs demonstrated stability when exposed to irrelevant statements, maintaining focus on the main query. This is a positive outcome, though the possibility remains that more complex distractions could affect performance. Generally, prompt sensitivity is not inherently a disadvantage; it can be beneficial when used intentionally for performance enhancement through prompt engineering. Our study found that instructive and advanced system prompts, which request specific and detailed reasoning by pointing out the validation requirements, improve performance by up to 12 score-points for medium-performing models. Curiously, this improvement, predicted in [

24], was triggered by mere mentioning of the requirements, whereas quoting their explicit definition resulted in no additional gains (compare the improvements by system prompt complexity for DSR Llama 70B and GPT-4o mini,

Figure 3a). However, state-of-the-art commercial models like GPT-4o and o3 mini already perform consistently well with simple prompts, showing only slight improvements when given additional instructions.

In our study, LLMs appeared to exhibit age-related performance bias [

37], which however may be induced by the differential incidence of diseases represented in the corresponding test cases. And indeed, our framework revealed that LLMs are more likely to correctly identify frequently observed degenerative musculoskeletal and cardiovascular diseases, compared to rare hormonal conditions, demonstrating that the age bias may be explained at least in part by the age-associated prevalence of certain diseases, see

Figure 3c-e. RAG led to model-dependent increases or decreases in performance. This is interesting since RAG is typically used to mitigate knowledge gaps and improve response quality. Given the growing interest in clinically applicable RAG systems [

38,

39], future research should explore how RAG-based applications affect different dimensions of model quality, helping to determine which aspects of LLM performance are most influenced by this strategy. As a clear limitation, we applied only one frequently implemented flavor of RAG based on a database of papers relevant to longevity interventions.

There are general limitations to our study. Our benchmark started with queries synthesized for 25 fictional individuals, and use of real-world queries would have provided more authenticity at the expense of a much higher heterogeneity and a lack of patterns such as the ones used to investigate the role of the age group and the underlying disease. By generating 1,000 test cases through modular variation, we mimicked some real-world diversity. Another limitation is the use of an LLM-as-a-Judge to evaluate tested LLMs, which may introduce model-specific biases, that is, the tendency of judgments to favor the responses from certain models rather than assessing them based on e.g. a predefined metric. To mitigate this, provision of physician-validated ground truths to the LLM-as-a-judge were employed, but further studies are needed to assess the consistency of automated judgments, and also to compare these to human evaluations. Furthermore, while our study examined performance differences based on age and disease, it did not explore how other definitions of the age groups, swapping ages within test cases, or including a higher variety of diseases might influence LLM behavior. More elaborate item templates, i.e. by “symbolization” [

36] are left to future investigations.

Popular medical and biomedical benchmarks, including MedQA, MedMCQA, MultiMedQA and the MIMIC datasets (including MIMIC-III [

40], MIMIC-IV-ED [

41], MIMIC-IV-ICD [

42]) primarily assess LLM performance using multiple-choice question formats. While valuable, these approaches often fail to capture important nuances of model capabilities, such as personalization or robustness in open-ended tasks. Here, we developed a benchmark designed to evaluate LLMs across five validation requirements using modular, open-ended test items. These items focussed on personalized intervention recommendations in geroscience and longevity medicine and were aligned with physician expertise through expert annotation. Our systematic and automated model evaluation approach enables testing LLMs in various medical domains. Future work could explore the extension of our framework to real-world clinical settings and continuous evaluation as models evolve. To facilitate this effort, the frameworks used and developed in this study are freely available and intended to be adapted and extended by other researchers for benchmarking models in diverse medical or other research contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: GF, SL, BK; Data Curation: HJ, CB, SF, AH, BZ; Formal Analysis: HJ; Funding Acquisition: --; Investigation: HJ; Methodology: GF, SL; Project Administration: GF, SL, BK; Resources: GF, SL; Software: HJ, SL; Supervision: GF, SL, BK; Validation: GF, SL; Visualization: HJ, SL; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: HJ, GF, SL; Writing – Review & Editing: all authors.

Funding

AH is supported by the Hermann and Lilly Schilling Stiftung für medizinische Forschung im Stifterverband.

Data and code availability

Statement on the use of AI

The first draft was written by HJ, with help from GF and SL. No writing assistance was employed. While the topic of the perspective is the use of generative AI/LLMs, no such tools were used to generate text or content of the manuscript. GPT4-o was used for copy-editing (grammar, spelling) assistance and research queries on related work and references.

Conflicts of Interest

BKK reports a relationship with Ponce de Leon Health that includes: consulting or advisory and equity or stocks. CB has received lecturing fees from Novartis Deutschland GmbH and Bayer Vital GmbH. CB serves on the expert board for statutory health insurance data of IQTIG, the Institute for Quality and Transparency in German Healthcare (Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen). GF is a consultant to BlueZoneTech GmbH, who distribute supplements.

References

- Alowais SA, Alghamdi SS, Alsuhebany N, et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med Educ 2023;23(1):689. [CrossRef]

- Secinaro S, Calandra D, Secinaro A, Muthurangu V, Biancone P. The role of artificial intelligence in healthcare: a structured literature review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2021;21(1):125. [CrossRef]

- Meng X, Yan X, Zhang K, et al. The application of large language models in medicine: A scoping review. iScience 2024;27(5):109713. [CrossRef]

- Silcox C, Zimlichmann E, Huber K, et al. The potential for artificial intelligence to transform healthcare: perspectives from international health leaders. NPJ Digit Med 2024;7(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Kroemer G, Maier AB, Cuervo AM, et al. From geroscience to precision geromedicine: Understanding and managing aging. Cell 2025;188(8):2043-2062. [CrossRef]

- Parchmann N, Hansen D, Orzechowski M, Steger F. An ethical assessment of professional opinions on concerns, chances, and limitations of the implementation of an artificial intelligence-based technology into the geriatric patient treatment and continuity of care. Geroscience 2024;46(6):6269-6282. [CrossRef]

- Vahia IV. Navigating New Realities in Aging Care as Artificial Intelligence Enters Clinical Practice. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2024;32(3):267-269. [CrossRef]

- Stefanacci RG. Artificial intelligence in geriatric medicine: Potential and pitfalls. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023;71(11):3651-3652. [CrossRef]

- Wiil UK. Important steps for artificial intelligence-based risk assessment of older adults. Lancet Digit Health 2023;5(10):e635-e636. [CrossRef]

- Ma B, Yang J, Wong FKY, et al. Artificial intelligence in elderly healthcare: A scoping review. Ageing Res Rev 2023;83:101808. [CrossRef]

- Jin D, Pan E, Oufattole N, Weng W-H, Fang H, Szolovits P. What Disease Does This Patient Have? A Large-Scale Open Domain Question Answering Dataset from Medical Exams. Applied Sciences. Appl Sci 2021; 11(14):6421. [CrossRef]

- Pal A, Umapathi LK, Sankarasubbu M. MedMCQA: A Large-scale Multi-Subject Multi-Choice Dataset for Medical domain Question Answering. In: Gerardo F, George HC, Tom P, Joyce CH, Tristan N, eds. Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research: PMLR, 2022:248-260. Available from: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v174/pal22a.html.

- Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023;620(7972):172-180. [CrossRef]

- Jin Q, Dhingra B, Liu Z, Cohen W, Lu X. PubMedQA: A Dataset for Biomedical Research Question Answering. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 2019:2567–2577. Available from: https://pubmedqa.github.io.

- Šuster S, Daelemans W. CliCR: a Dataset of Clinical Case Reports for Machine Reading Comprehension. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2018:1551-1563. [CrossRef]

- Wang LL, deYoung J, Wallace B. Overview of MSLR2022: A Shared Task on Multi-document Summarization for Literature Reviews. Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Scholarly Document Processing, 2022:175-180. Available from: https://aclanthology.org/2022.sdp-1.20.

- Li J, Sun Y, Johnson RJ, et al. BioCreative V CDR task corpus: a resource for chemical disease relation extraction. Database (Oxford) 2016;2016. [CrossRef]

- Krallinger M, Leitner F, Rabal O, Vazquez M, Oyarzabal J, Valencia A. CHEMDNER: The drugs and chemical names extraction challenge. J Cheminform 2015;7(Suppl 1 Text mining for chemistry and the CHEMDNER track):S1. [CrossRef]

- Kury F, Butler A, Yuan C, et al. Chia, a large annotated corpus of clinical trial eligibility criteria. Sci Data 2020;7(1):281. [CrossRef]

- Schmidgall S, Harris C, Essien I, et al. Evaluation and mitigation of cognitive biases in medical language models. NPJ Digit Med 2024;7(1):295. [CrossRef]

- Wu C, Qiu P, Liu J, et al. Towards evaluating and building versatile large language models for medicine. NPJ Digit Med 2025;8(1):58. [CrossRef]

- Kanithi PK, Christophe C, Pimentel MAF, et al. MEDIC: Towards a Comprehensive Framework for Evaluating LLMs in Clinical Applications. September 11, 2024 (https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.07314). Preprint.

- Zheng L, Chiang W-L, Sheng Y, et al. Judging LLM-as-a-judge with MT-bench and Chatbot Arena. 37th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023) Track on Datasets and Benchmarks, 2020:46595-46623. Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3666122.3668142.

- Fuellen G, Kulaga A, Lobentanzer S, et al. Validation requirements for AI-based intervention-evaluation in aging and longevity research and practice. Ageing Res Rev 2025;104:102617. [CrossRef]

- Zakka C, Shad R, Chaurasia A, et al. Almanac - Retrieval-Augmented Language Models for Clinical Medicine. NEJM AI 2024;1(2). [CrossRef]

- Lobentanzer S, Feng S, Bruderer N, et al. A platform for the biomedical application of large language models. Nat Biotechnol 2025;43(2):166-169. [CrossRef]

- Grattafiori A, Dubey A, Jauhri A, et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. July 31, 2024 (https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.21783). Preprint.

- Lobentanzer S, Aloy P, Baumbach J, et al. Democratizing knowledge representation with BioCypher. Nat Biotechnol 2023;41(8):1056-1059. [CrossRef]

- Vallat R. Pingouin: statistics in Python. The Journal of Open Source Software 2018;3(31):1026. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res 2011;12(85):2825-2830. Aailable from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/1953048.2078195.

- Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020;17(3):261-272. [CrossRef]

- Busch F, Hoffmann L, Rueger C, et al. Current applications and challenges in large language models for patient care: a systematic review. Commun Med (Lond) 2025;5(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Pang C. Is a partially informed choice less autonomous?: a probabilistic account for autonomous choice and information. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2023;10:131. [CrossRef]

- Hager P, Jungmann F, Holland R, et al. Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision-making. Nat Med 2024;30(9):2613-2622. [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh I, Alizadeh K, Shahrokhi H, Tuzel O, Bengio S, Farajtabar M. GSM-Symbolic: Understanding the Limitations of Mathematical Reasoning in Large Language Models. October 7, 2024 (https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.05229). Preprint.

- Chu CH, Nyrup R, Leslie K, et al. Digital Ageism: Challenges and Opportunities in Artificial Intelligence for Older Adults. Gerontologist 2022;62(7):947-955. [CrossRef]

- Ng KKY, Matsuba I, Zhang PC. RAG in Health Care: A Novel Framework for Improving Communication and Decision-Making by Addressing LLM Limitations. N Engl J Med AI 2024;2(1). [CrossRef]

- Kresevic S, Giuffre M, Ajcevic M, Accardo A, Croce LS, Shung DL. Optimization of hepatological clinical guidelines interpretation by large language models: a retrieval augmented generation-based framework. NPJ Digit Med 2024;7(1):102. [CrossRef]

- Harutyunyan H, Khachatrian H, Kale DC, Ver Steeg G, Galstyan A. Multitask learning and benchmarking with clinical time series data. Sci Data 2019;6(1):96. [CrossRef]

- Xie F, Zhou J, Lee JW, et al. Benchmarking emergency department prediction models with machine learning and public electronic health records. Sci Data 2022;9(1):658. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen T-T, Schlegel V, Kashyap A, et al. Mimic-IV-ICD: A new benchmark for eXtreme MultiLabel Classification. April 27, 2023 (https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.13998). Preprint.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).