1. Introduction

The widespread adoption of chat-based Artificial Intelligence (AI) models has enabled individuals to access detailed information about various diseases, including rare ones [?]. Users can interact with both free and pay-per-use web-based dialogue systems to pose complex queries about general and specific disease topics. Building upon the foundational work by Sarraju et al. [?], this study evaluates the accuracy of responses from five prominent AI models—chatGPT3.5, chatGPT4.0, Talk.AI, Gemini 1.0-Pro, and Web Search—to a series of standardized questionnaires.

Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a sophisticated class of computational tools capable of performing both general and specialized language tasks [

1,

2]. These models process vast amounts of text during their training, positioning them within the broader category of generative AI. The underlying architecture for these models is based on deep artificial neural networks using the transformer architecture [

3,

4]. Within this architecture, each input text is tokenized and represented as a vector in an

n-dimensional space. Neural layers employing an attention mechanism then process these vectors, emphasizing contextually relevant tokens. However, LLMs can sometimes generate inconsistent outputs, or

hallucinations, due to semantically inaccurate associations between token vectors. Techniques such as fine-tuning on specific contexts or employing Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) systems have been proposed to mitigate these issues [?].

The potential applications for LLMs are vast [

5], with a notable proficiency in encoding medical and clinical knowledge [

6,

7,

8]. LLMs efficiently learn and compress knowledge from medical texts, which can then be applied in various downstream tasks, such as clinical decision support, summarization of medical findings, and answering patient inquiries.

In this research, we specifically assess how well LLMs respond to established medical questionnaires. Our methodology extends the investigations of Sarraju et al. [

9] by including a broader array of models and questionnaires, similar to focused studies in specific disciplines [

10].

The evaluation was conducted during July and August 2024, using nine distinct questionnaires including DKQ-R [

11],

Rare Disease. Rare Disease 2 and Rare Disease 3 [

12], Hearth Disease KC [

13], MSKQ-A and MSKQ-B [

14], Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire for CHD [

15], and Questionnaire of knowledge and perception towards COVID-19 [

16]. . These tools cover a spectrum of topics related to various diseases, such as risk factors, prevalence, awareness, and patient behaviors. Demographic queries were excluded from this analysis. Responses from each AI model were collated and assessed by expert clinicians as either "appropriate" or "inappropriate."

Our findings indicate that while there are notable differences between the models, all were deemed to provide appropriate responses. Notably, chatGPT4.0 frequently delivered more comprehensive and engaging information, enhancing the user’s understanding of disease demographics and subgroups.

This research not only builds on previous studies, but also introduces the evaluation of rare diseases into the evaluation of AI model responses. The increasing reliance on AI tools by both individuals and clinicians for educational and informational purposes underscores the importance of accurate information dissemination. Our study demonstrates improvements in AI-generated responses, crucial for managing both common and rare diseases with limited available information.

We also propose that AI models could significantly enrich patient and student knowledge. Clinicians might leverage customized chat interfaces to facilitate enhanced communication with patients, encouraging the use of AI to broaden their understanding of diseases and inform their management strategies. Despite these promising results, limitations remain, such as the non-suitability of chatbots as medical devices and the need for further research to evaluate response stability and regulatory compliance. Future research will aim to develop standardized grading criteria and enable fair comparisons among different AI models, as suggested by prior studies [

17,

18].

2. Methods

For each of the following questionnaires, we submitted questions to various Large Language Models (LLMs). The responses were recorded and assessed as appropriate or inappropriate with the assistance of a medical doctor holding a PhD.

2.1. LLM Descriptions

We considered the following LLMs and chatbots: Claude 3 Haiku [

19], WebSearch [

20], chatGPT3.5 and chatGPT4.0 [

21], TalkAI [

22], and Gemini A1 [

23].

Claude 3, also referred to as "Claude 3-Haiku," developed by Anthropic, belongs to the Claude family of models. It is designed for intuitive and natural interactions, optimized for accuracy and minimal hallucinations. This model, built on a transformer architecture, features billions of parameters and has been fine-tuned to enhance its performance. It includes APIs for easy integration into custom applications.

Web-Search, powered by Claude 3.5 Sonnet, combines LLM capabilities with real-time internet search. This unique feature allows it to access and process current information, making it especially useful for queries about ongoing events. It is accessible through APIs for integration into various platforms.

ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4, developed by OpenAI, are advanced models based on the Transformer architecture, designed to generate human-like text. ChatGPT-3.5 features 175 billion parameters and 96 Transformer layers, using the GELU activation function and trained to minimize cross-entropy loss. ChatGPT-4, an evolution of ChatGPT-3.5, includes more layers and an extended context window, enhancing its ability to manage complex dialogues.

TalkAI is tailored for conversational interactions, supporting text and voice inputs. This model excels in maintaining context over extended dialogue turns and ensures data security and privacy compliance, making it ideal for applications in customer service and personal assistants.

Gemini A1 by Google AI, is a versatile model capable of text generation, translation, and summarization, with significant implications for healthcare and medical applications. It boasts 1.8 billion parameters and supports tasks like medical literature summarization and clinical decision-making.

2.2. Questionnaires

We utilized the following questionnaires: DKQ-R [

11],

Rare Disease series [

12], Heart Disease KC [

13], MSKQ-A and MSKQ-B [

14], Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire for CHD [

15], and the Questionnaire on knowledge and perception towards COVID-19 [

16].

The DKQ-R is designed to evaluate diabetes knowledge, specifically type 2 diabetes, and is used to tailor educational interventions for better diabetes management.

The Rare Disease questionnaire series assesses knowledge about rare diseases in Kazakhstan, covering definitions, etiology, and prevalence. The Rare Disease 2 focuses on general questions, while the Rare Disease 3 targets medical students to identify educational gaps.

The Heart Disease KC explores awareness and understanding of heart disease, including prevention, symptoms, and treatment options.

The MSKQ-A and MSKQ-B assess knowledge about musculoskeletal disorders, aiming to improve educational strategies and clinical practices.

The Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire for CHD assesses knowledge related to coronary heart disease, and the Questionnaire on knowledge and perception towards COVID-19 focuses on COVID-19 related knowledge and perceptions, excluding demographic sections.

Figure 1.

Accuracy of the Models.

Figure 1.

Accuracy of the Models.

Table 1.

Average Accuracy on all questionnaires

Table 1.

Average Accuracy on all questionnaires

| Questionnaire |

N. Answers |

Accuracy |

| DKQ-R |

22 |

100% |

| Rare Disease |

14 |

100% |

| Rare Disease 2 |

7 |

100% |

| Rare Disease 3 |

6 |

100% |

| Heart Disease KC |

15 |

100% |

| MSKQ-A |

21 |

100% |

| MSKQ-B |

25 |

100% |

| Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire for CHD |

18 |

100% |

| Questionnaire of knowledge and perception towards COVID-19 |

8 |

100% |

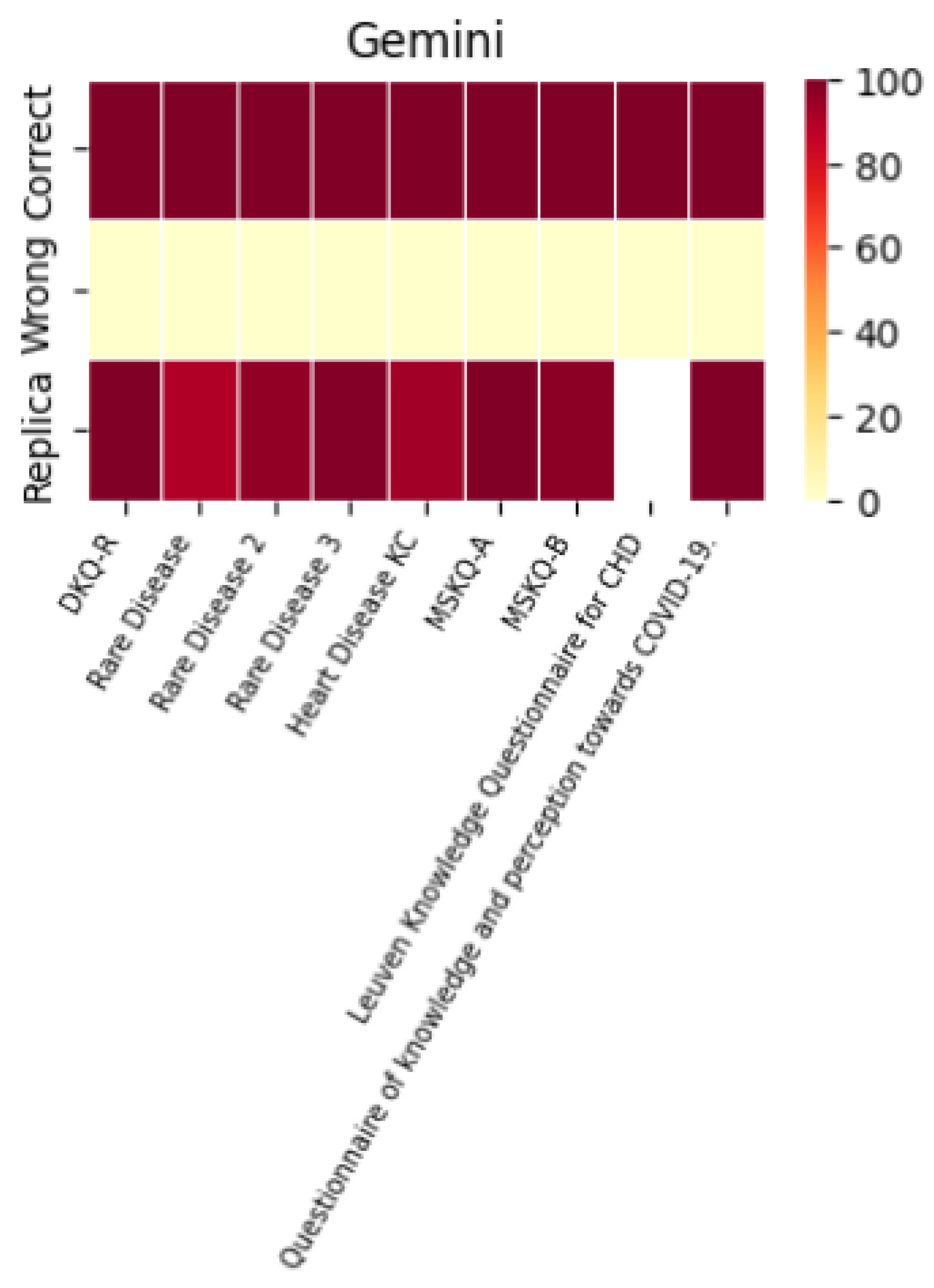

3. Results and Discussion

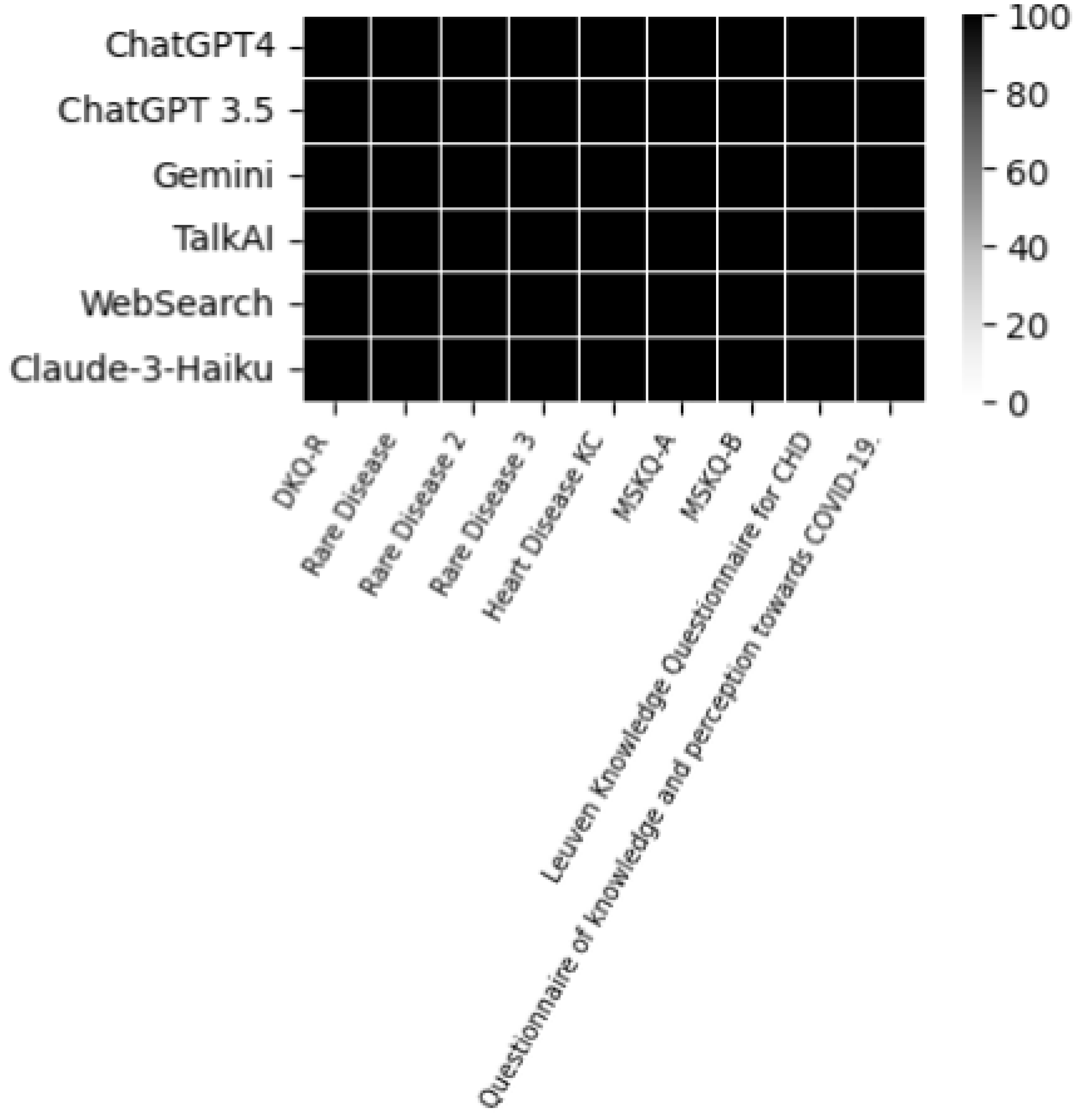

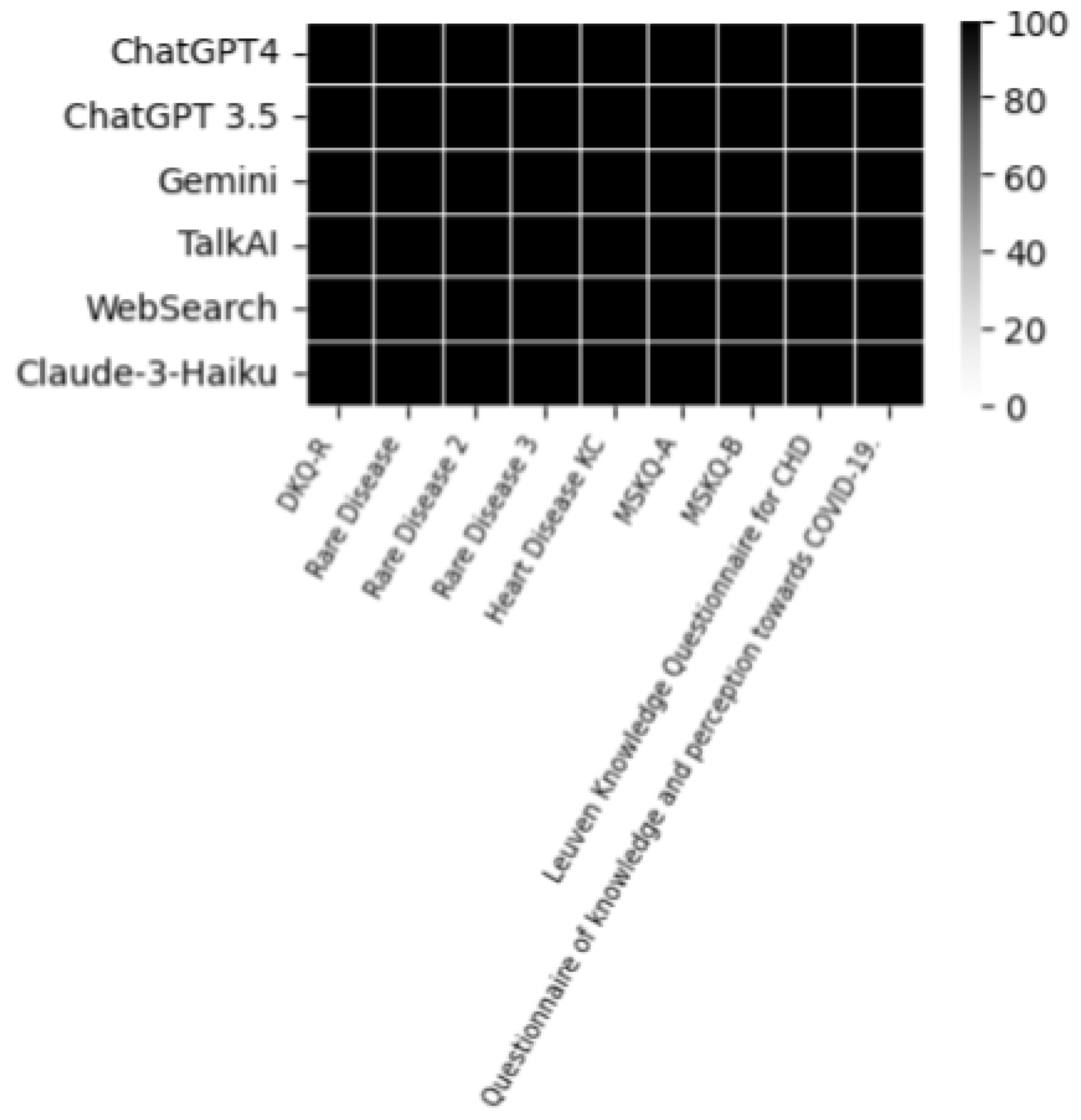

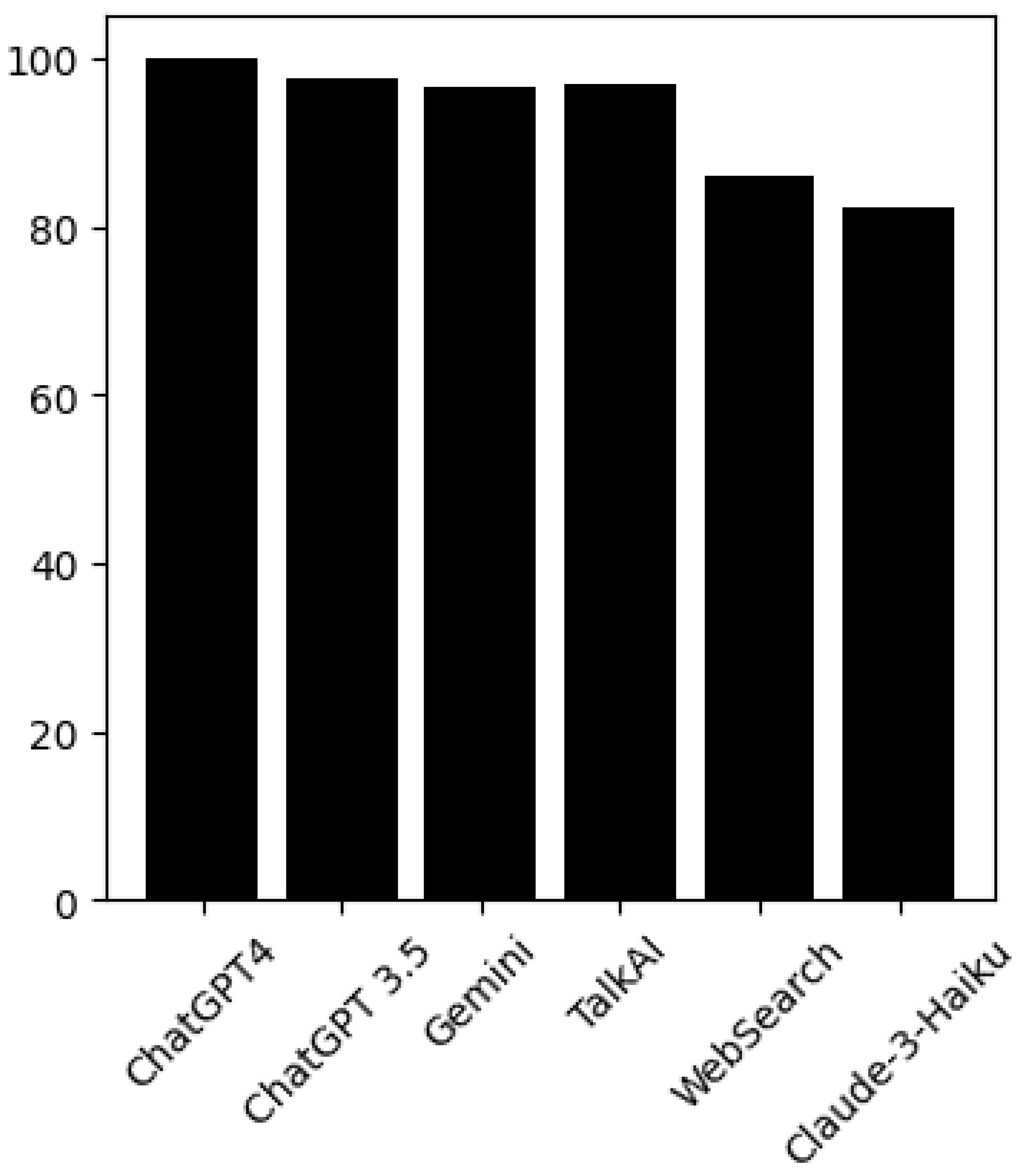

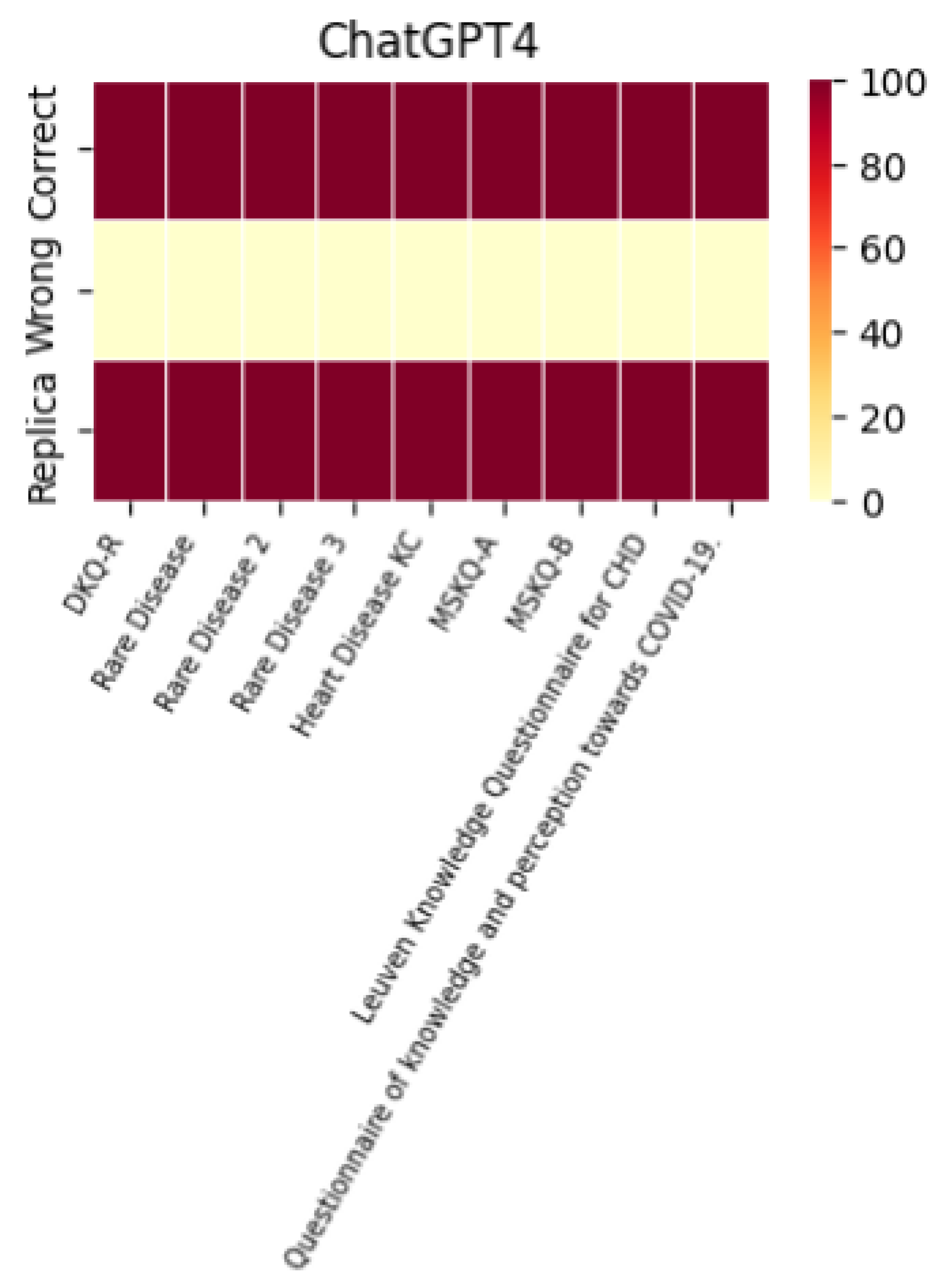

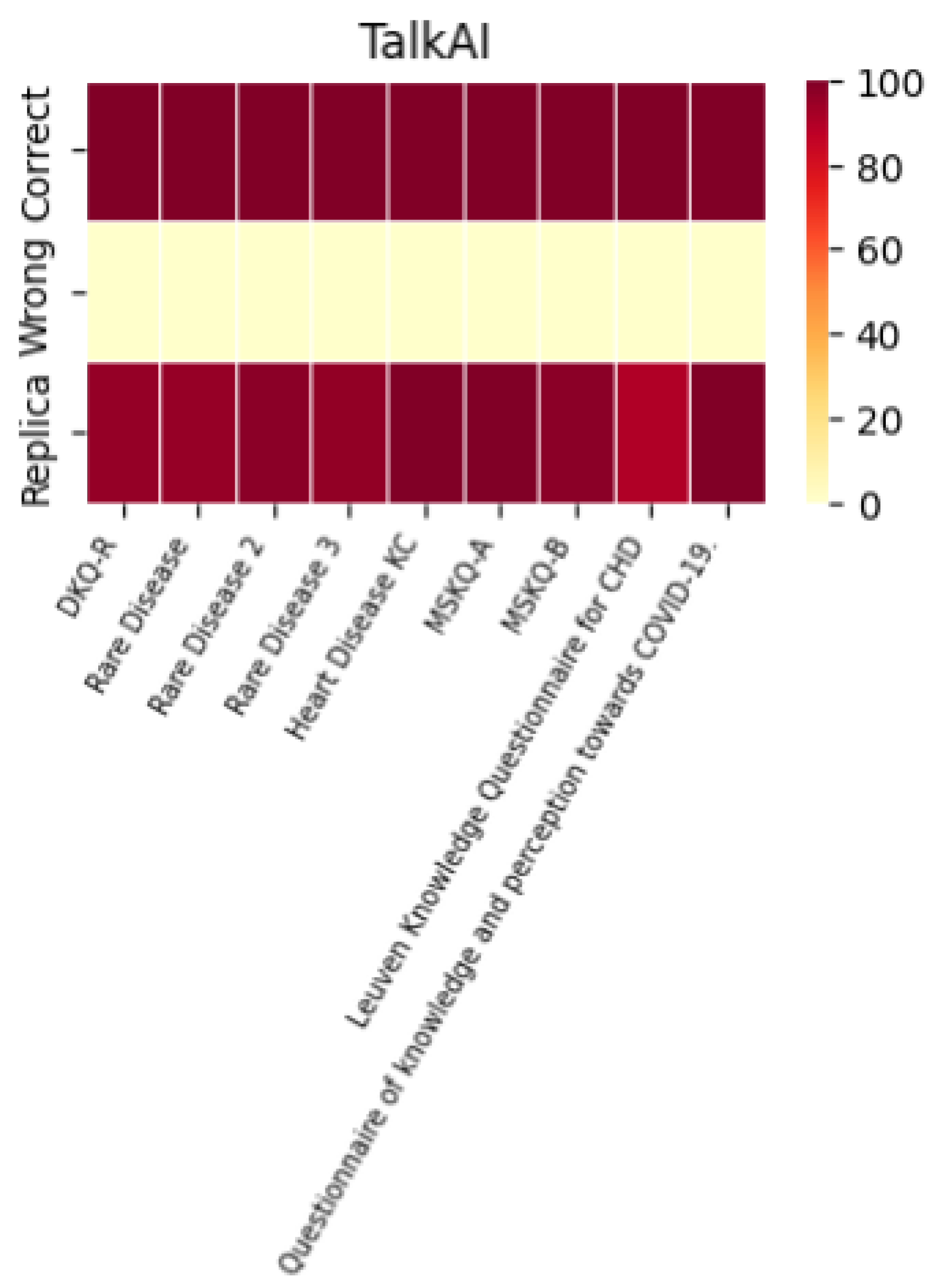

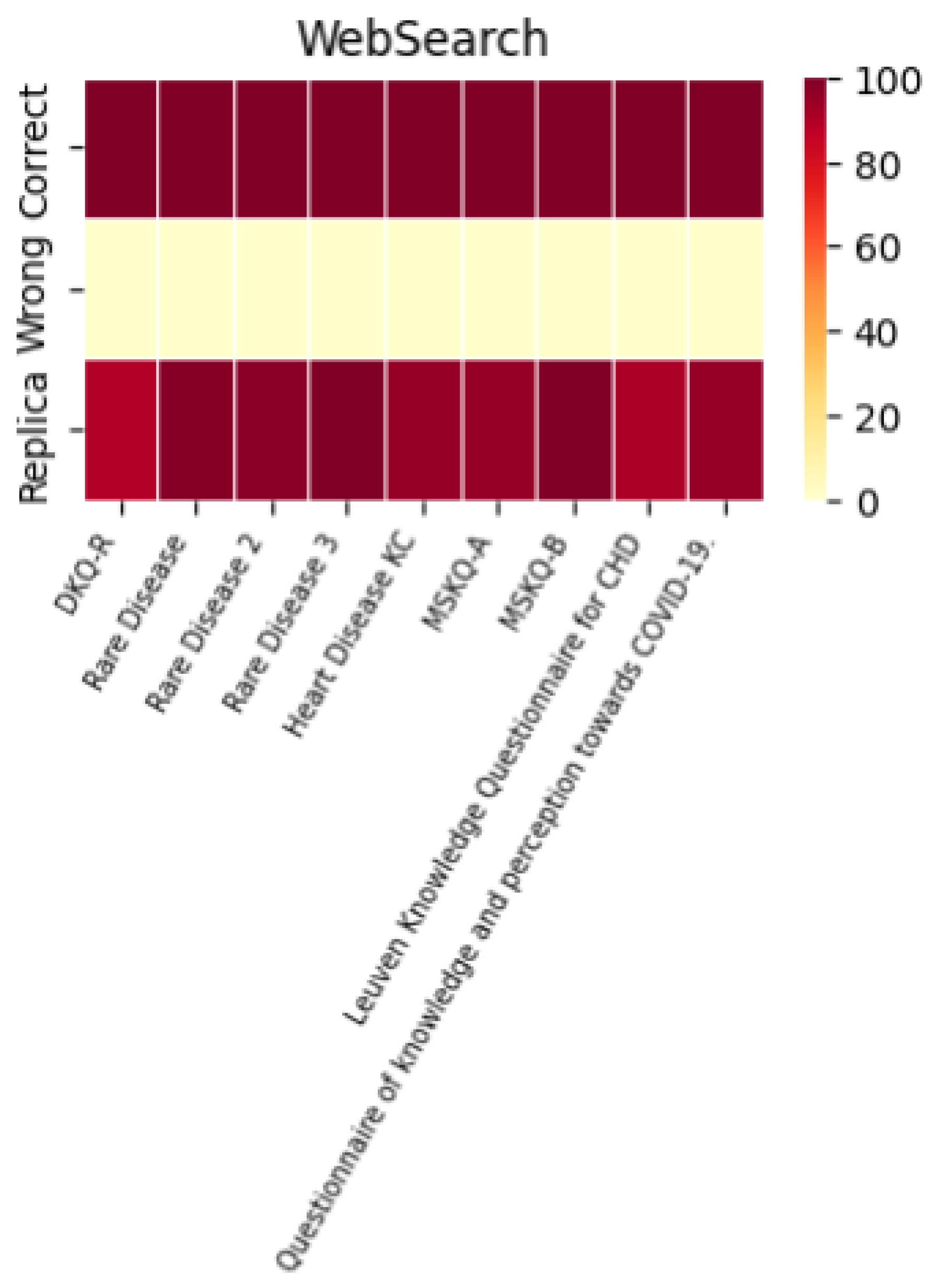

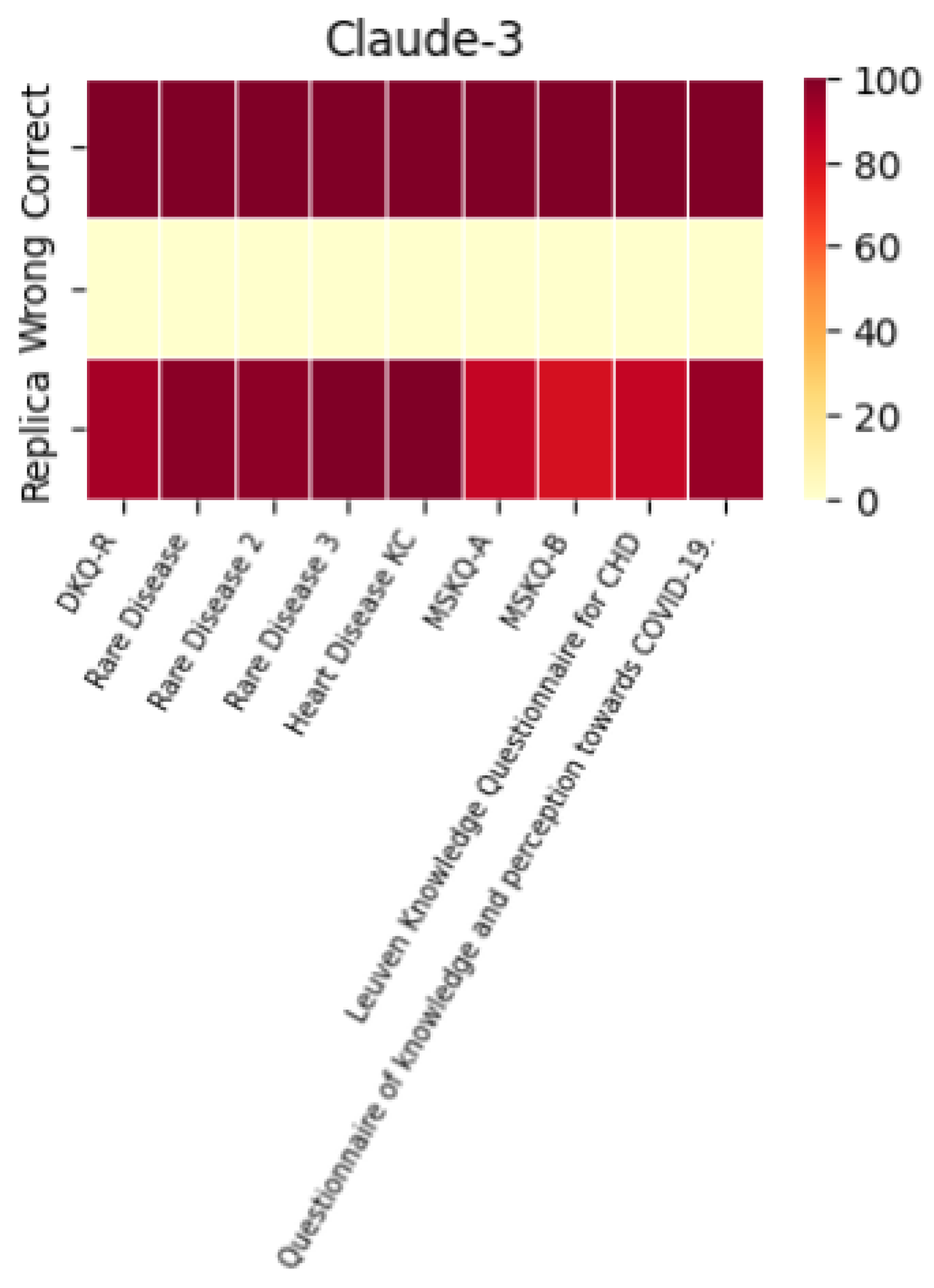

In this section, we discuss the results obtained using various graphical representations. Specifically, we generated heat maps and histograms to evaluate the repetition percentages for each questionnaire (

Figure 2), the overall performance of each LLM for each questionnaire (

Figure 3), and the general performance of each individual LLM by assessing the percentages of correct answers, incorrect answers, and the number of repetitions (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9). Additionally, we analyzed the appropriateness of the different LLMs’ responses (

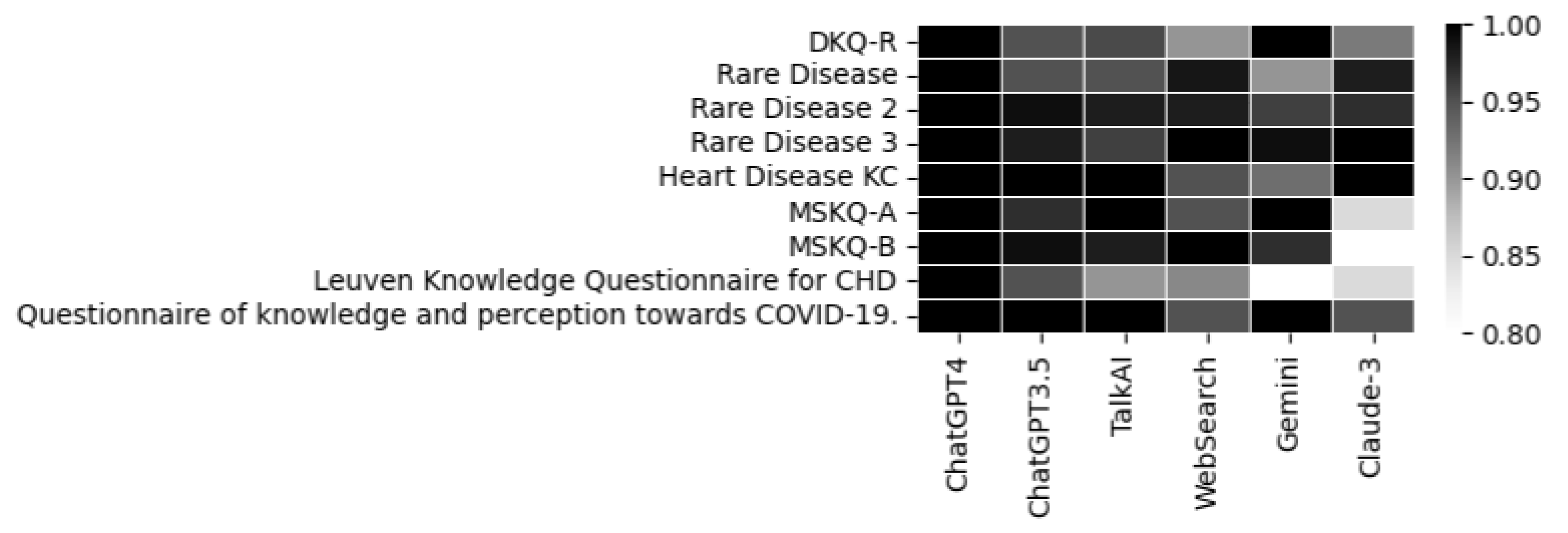

Figure 3).

A histogram was used to evaluate the models’ performance in terms of their ability to replicate correct responses consistently. The results across different LLMs were surprisingly consistent. For example, with the MSKQ-B questionnaire, almost every model achieved scores between 97% and 100% for appropriate responses. This consistency not only strengthens the reliability of each LLM but also suggests a potential alignment in the training data. The stability and reliability demonstrated by the repetition of responses are crucial for the use of these models in educational settings and healthcare management.

The overall performance of the various LLMs was evaluated using a heat map constructed with the following formula:

Appropriate responses were defined as those containing correct and relevant information, while inappropriate responses included inaccurate or misleading content.

The performance of each individual LLM is described by the heat maps below, which visualize the average of correct answers, incorrect answers, and repetitions for each model.

It is noteworthy that the performance in terms of correct and incorrect answers is identical for both ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-3.5, while ChatGPT-4 demonstrates superior performance in response repetition accuracy compared to ChatGPT-3.5.

The recorded accuracy rates provide a clear indicator of each model’s reliability in processing and delivering relevant information. The various LLMs exhibit similar performance, with only minimal variations related to the repetition percentage.

A heatmap is also included to represent the appropriateness, summarizing the performance of each individual LLM across the different questionnaires used.

Figure 10.

Appropriateness of each LLM.

Figure 10.

Appropriateness of each LLM.

4. Conclusion

This study examines the applicability of large language models (LLMs) within the healthcare sector, focusing on their capacity to accurately and contextually convey information on diverse medical conditions. Utilizing a structured series of specialized questionnaires, we analyzed the response quality from a selection of LLMs, including ChatGPT 4.0, ChatGPT 3.5, Gemini, TalkAI, Web Search, and Claude-3 Haiku. The results reveal a high degree of precision and consistency, underscoring the substantial potential of these models for healthcare communication.

The data confirm that the LLMs under examination can deliver contextually appropriate and accurate responses, demonstrating an advanced level of comprehension and communication within medical contexts. This accuracy supports the models’ utility in enhancing clinical knowledge dissemination and promoting health literacy, which are essential for improved patient outcomes and informed healthcare practices. The appropriateness of the responses also highlights potential areas for educational interventions, particularly for conditions such as diabetes and rare diseases.

Notably, the findings suggest that LLMs can function as effective tools for broadening awareness of specific medical conditions, benefiting both patients and healthcare providers. Their demonstrated relevance in response generation highlights their viability for educational and instructional applications within healthcare.

Moreover, the observed consistency across responses indicates stable performance among the tested LLMs, affirming their potential reliability for educational and informational support in medical settings. While each model exhibits distinct characteristics, the alignment in comprehension across models suggests shared elements in their training frameworks, a crucial factor in refining these models for optimized healthcare application.

Future developments could involve the inclusion of questionnaires covering a broader spectrum of conditions, such as rare diseases. Simultaneously, it may be beneficial to develop models specifically tailored to particular medical fields.

Acknowledgments

PVe was partially supported by project SERICS (PE00000014) under the MUR National Recovery and Resilience Plan funded by the European Union: NextGenerationEU. PHG is partially funded by the Next Generation EU - Italian NRRP, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.5, call for the creation and strengthening of “Innovation Ecosystems”, building “Territorial R&D Leaders” (Directorial Decree n. 2021/3277) - project Tech4You - Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement, n. ECS0000009.

References

- Ray, P.P. Timely need for navigating the potential and downsides of LLMs in healthcare and biomedicine. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2024, 25, bbae214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, U.; Ahmed, A.; Mumtaz, S. LLMs-Healthcare: Current applications and challenges of large language models in various medical specialties. Artificial Intelligence in Health 2024, 1, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, X. A survey of transformers. AI open 2022, 3, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Yang, J.; Jin, H.; Tang, R.; Han, X.; Feng, Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhong, S.; Yin, B.; Hu, X. Harnessing the power of llms in practice: A survey on chatgpt and beyond. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 2024, 18, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Jin, Q.; Yeganova, L.; Lai, P.T.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Kim, W.; Comeau, D.C.; others. Opportunities and challenges for ChatGPT and large language models in biomedicine and health. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2024, 25, bbad493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defilippo, A.; Veltri, P.; Lió, P.; Guzzi, P.H. Leveraging graph neural networks for supporting automatic triage of patients. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 12548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; others. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarraju, A.; Bruemmer, D.; Van Iterson, E.; Cho, L.; Rodriguez, F.; Laffin, L. Appropriateness of cardiovascular disease prevention recommendations obtained from a popular online chat-based artificial intelligence model. Jama 2023, 329, 842–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, M.C.; Wick, W.; Venkataramani, V. Performance of large language models on a neurology board–style examination. JAMA network open 2023, 6, e2346721–e2346721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuniga, J.A.; Huang, Y.C.; Bang, S.H.; Cuevas, H.; Hutson, T.; Heitkemper, E.M.; Cho, E.; García, A.A. Revision and Psychometric Evaluation of the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire for People With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum 2023, 36, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walkowiak, D.; Bokayeva, K.; Miraleyeva, A.; Domaradzki, J. The awareness of rare diseases among medical students and practicing physicians in the Republic of Kazakhstan. An exploratory study. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 872648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, H.E.; Reeve, B.B.; Moser, R.P.; Scholl, S.; Klein, W.M. Development of a comprehensive heart disease knowledge questionnaire. American journal of health education 2011, 42, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.; Messmer Uccelli, M.; Pucci, E.; Martinelli, V.; Borreani, C.; Lugaresi, A.; Trojano, M.; Granella, F.; Confalonieri, P.; Radice, D.; others. The Multiple Sclerosis Knowledge Questionnaire: a self-administered instrument for recently diagnosed patients. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2010, 16, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Wang, J.K.; Gau, B.S.; Chen, C.W.; Moons, P. Measuring knowledge of patients with congenital heart disease and their parents: validity of the ‘Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire for Congenital Heart Disease’. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 2012, 11, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayana, G.; Pradeepkumar, B.; Ramaiah, J.D.; Jayasree, T.; Yadav, D.L.; Kumar, B.K. Knowledge, perception, and practices towards COVID-19 pandemic among general public of India: a cross-sectional online survey. Current medicine research and practice 2020, 10, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, A.; Rostami, M.; Guzzi, P.H. AI-enabled pipeline for virus detection, validation, and SNP discovery from next-generation sequencing data. Frontiers in Genetics 2024, 15, 1492752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancotti, R.; Bosoni, P.; Vizza, P.; Tradigo, G.; Gnasso, A.; Guzzi, P.H.; Bellazzi, R.; Irace, C.; Veltri, P. Forecasting glucose values for patients with type 1 diabetes using heart rate data. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2024, 257, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3, A.C. https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-haiku.

- Websearch. https://poe.com/chat/.

- OpenAI. ChatGPT (August 26 version), 2024. Large language model, retrieved from https://chatgpt.com/.

- TalkAI. https://talkai.info/chat/.

- AI, G. Gemini AI, 2024. Available at https://www.google.com/gemini.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).