Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Rumen Samples for Yeast Isolation and Identification

2.2. Selection of Yeasts with Probiotic Potential

2.3. The Preparation of Candida Rugosa (NJ-5) Yeast Culture

2.4. Experimental Design and In Vitro Culture Procedure

2.5. Assessment of VFAs

2.6. DNA Extraction and 16S rDNA Sequencing

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

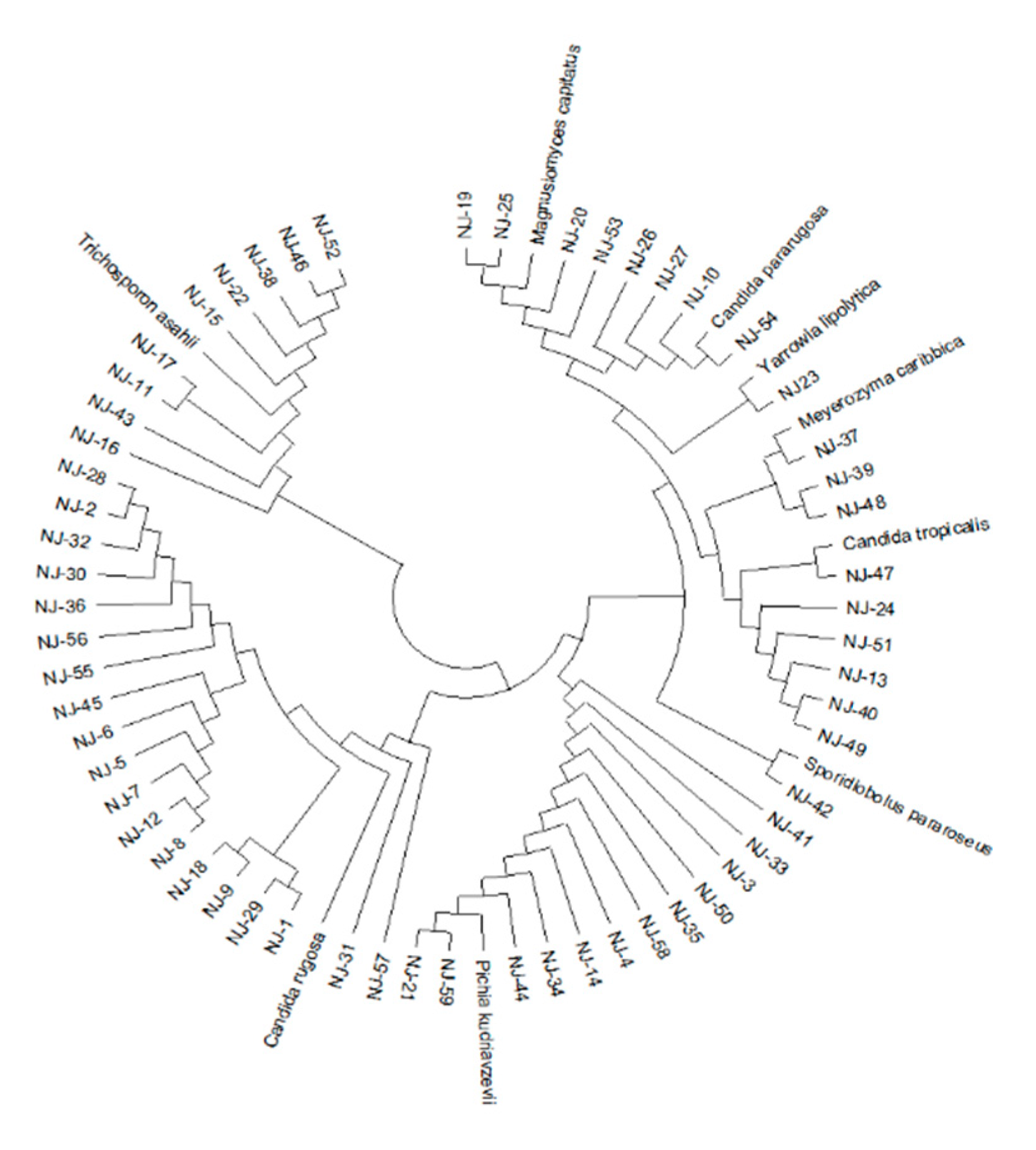

3.1. Isolation and Identification of Yeast Strains

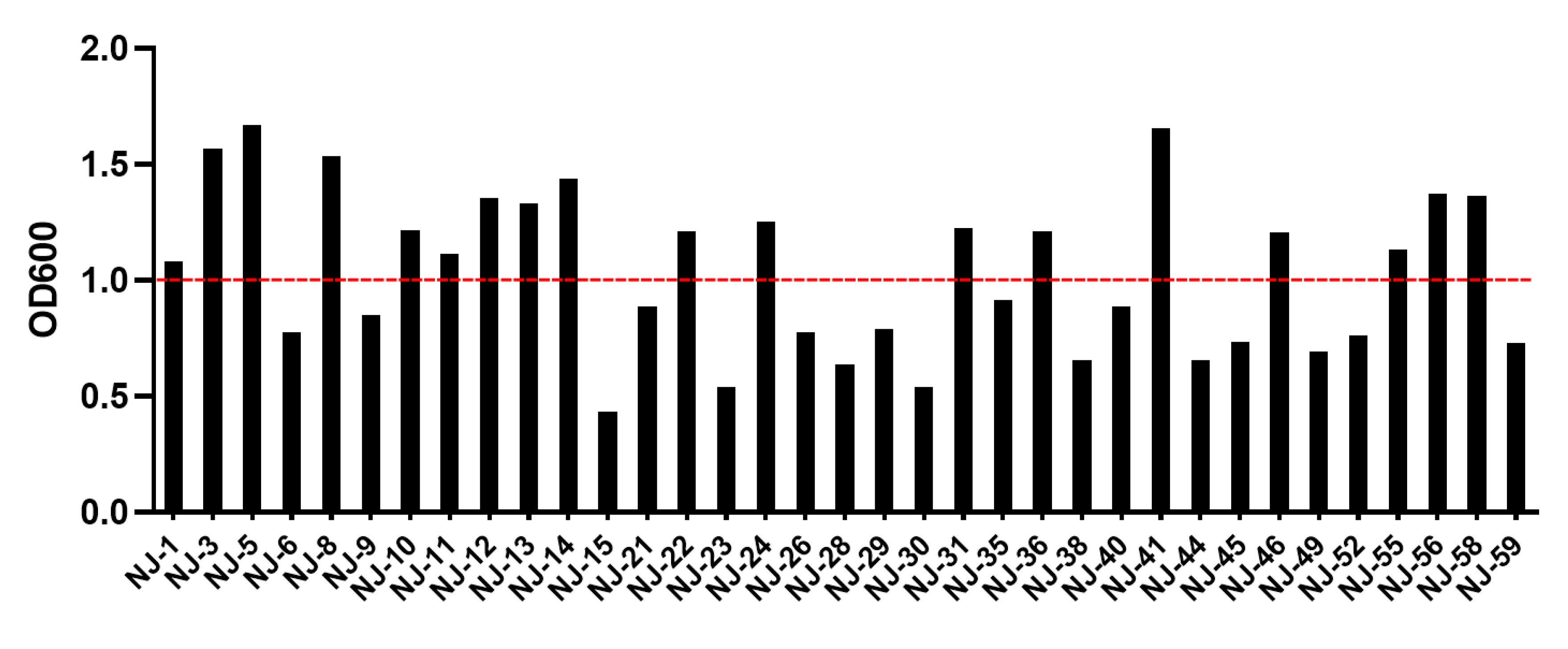

3.2. Anaerobic Capacity of Yeast Strains

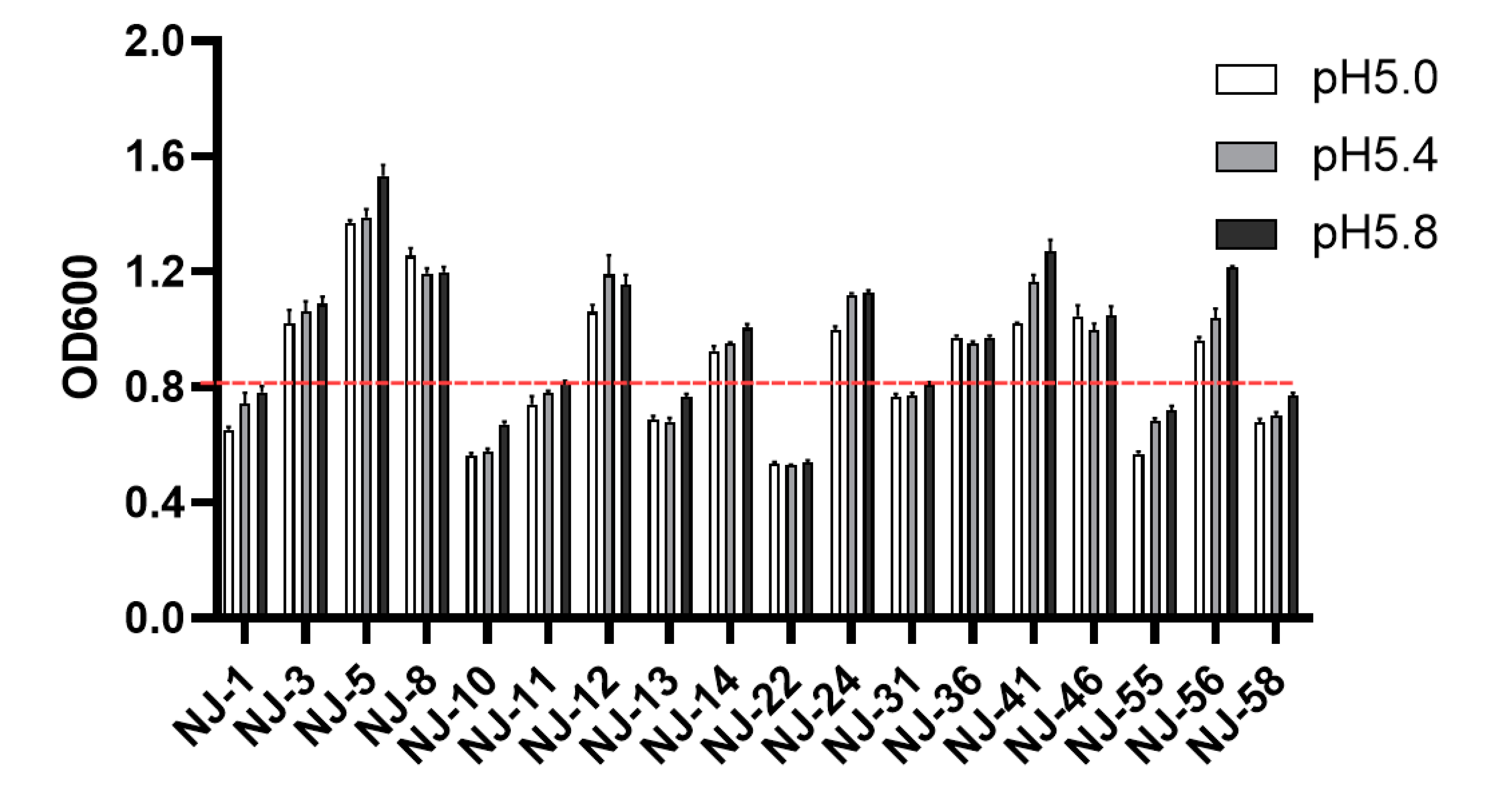

3.3. Evaluation of Acid Tolerance of Yeast Strains

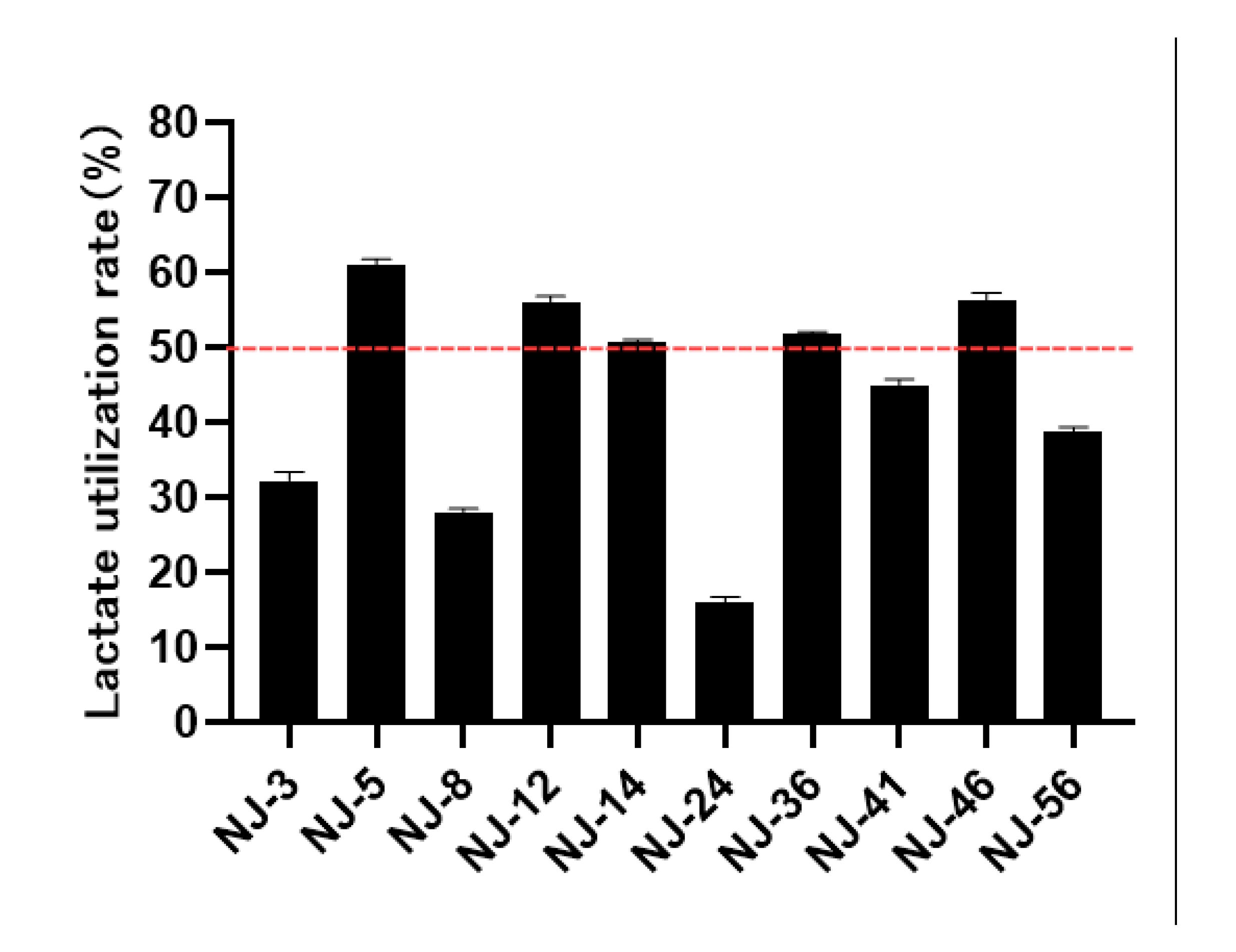

3.4. Evaluation of Lactate Utilization Capacity of Yeast Strains

3.5. Effect of Yeast Strains On VFAs Production In Vitro Rumen Fermentation

3.6. Preparation of Yeast Culture

3.7. Impact of Yeast Culture Supplementation on pH Value In Vitro Fermentation

3.8. Effect of Yeast Culture on VFAs Concentrations In Vitro Fermentation

3.9. Impact of Yeast Culture on bacteria Community In Vitro Fermentation

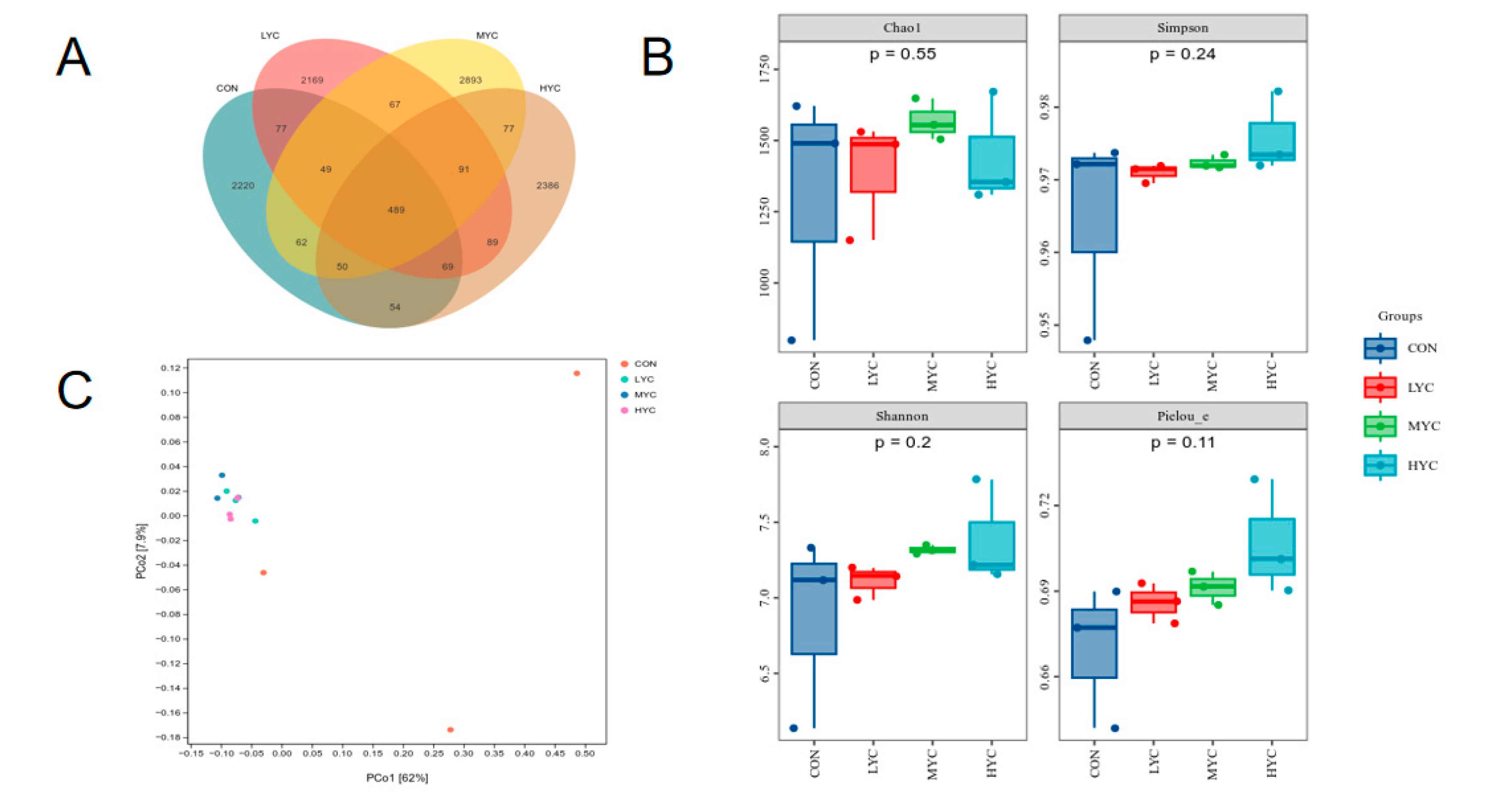

3.9.1. Rumen Bacterial Diversity Analysis

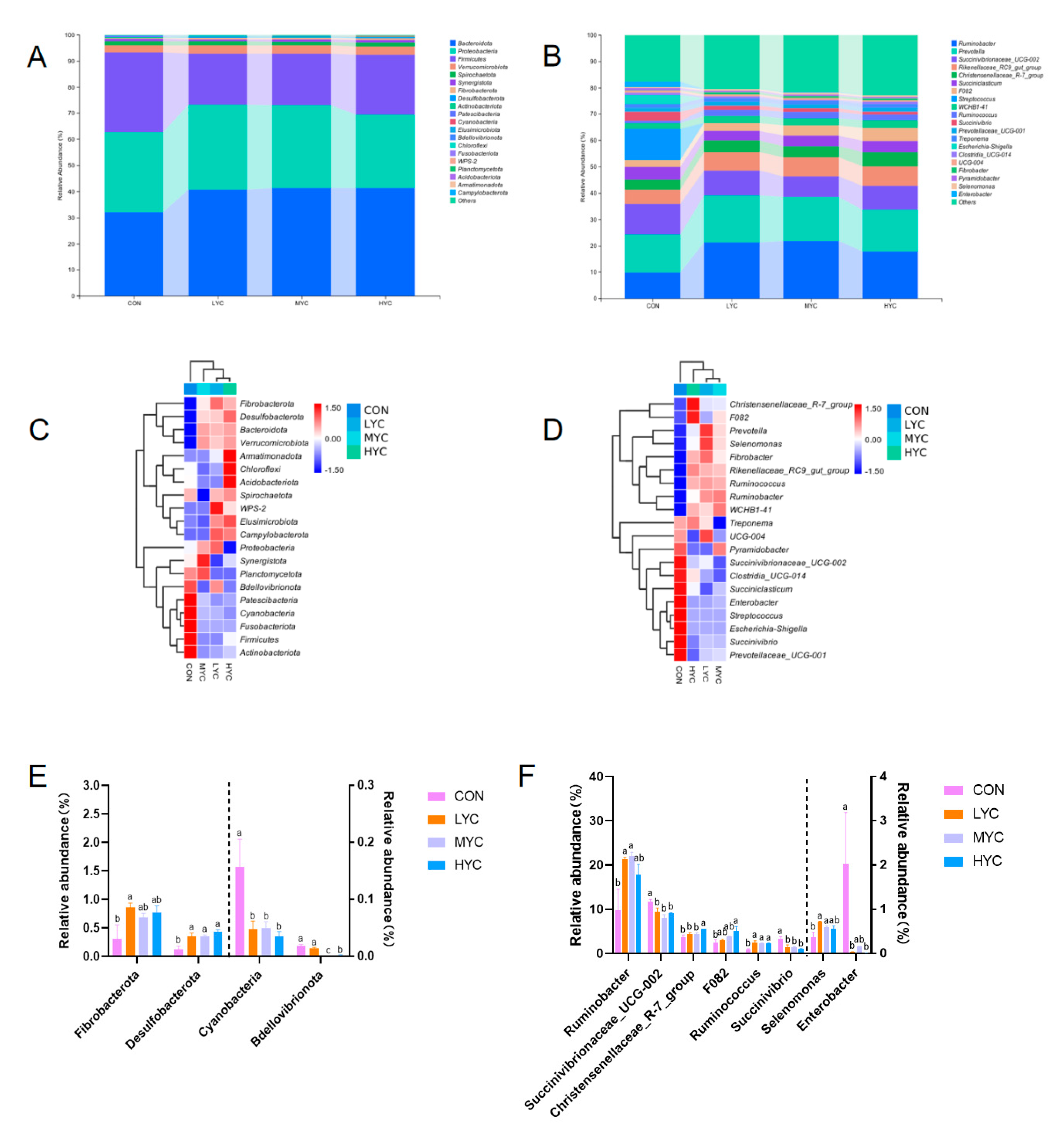

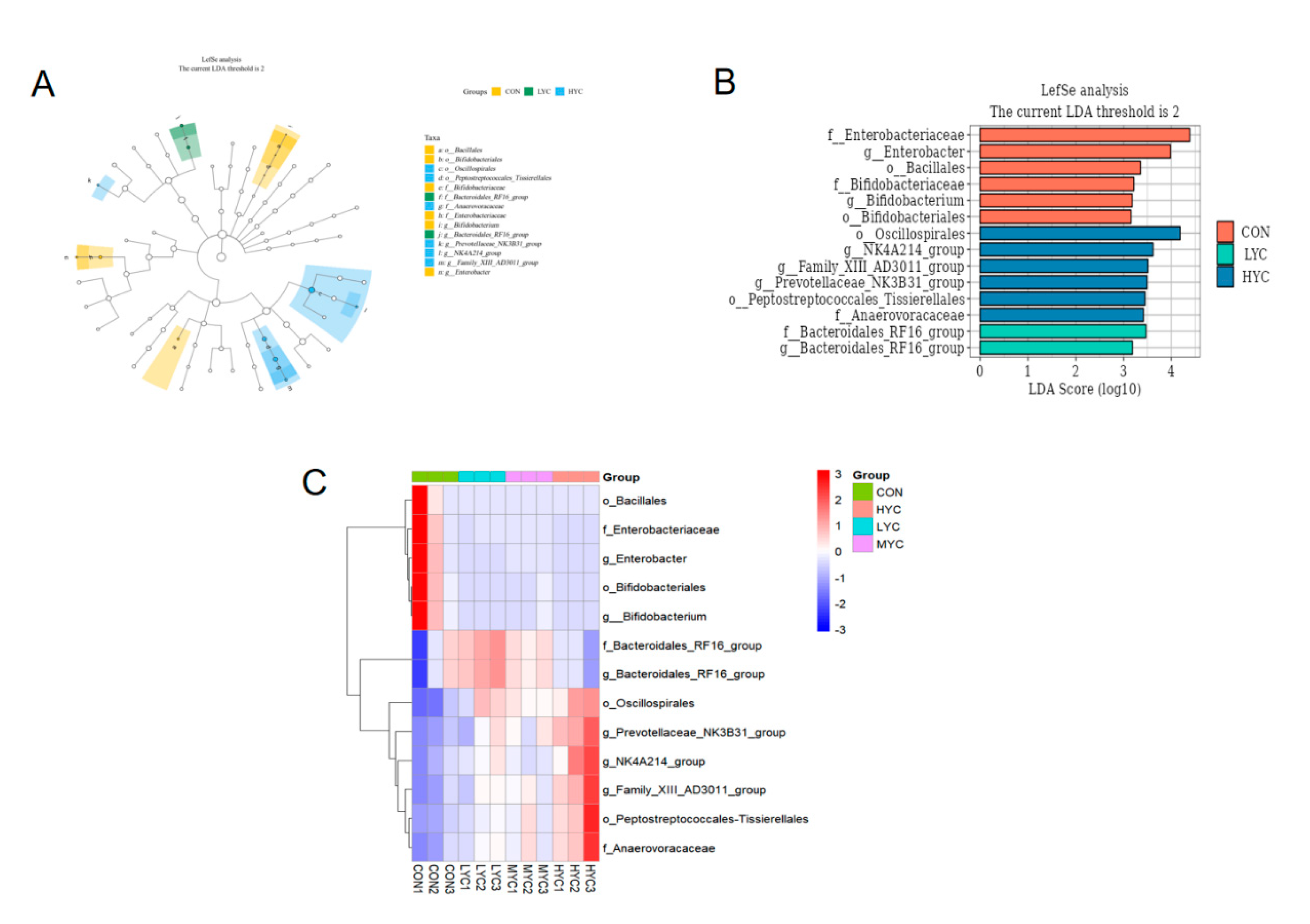

3.9.2. Impact of Yeast Culture on Bacteria Abundance in vitro Fermentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campanile, G.; Zicarelli, F.; Vecchio, D.; Pacelli, C.; Neglia, G.; Balestrieri, A.; Di Palo, R.; Infascelli, F. Effects of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae on in Vivo Organic Matter Digestibility and Milk Yield in Buffalo Cows. Livestock Science 2008, 114, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.K.; Heinrichs, A.J. Feeding Various Forages and Live Yeast Culture on Weaned Dairy Calf Intake, Growth, Nutrient Digestibility, and Ruminal Fermentation. Journal of Dairy Science 2020, 103, 8880–8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Su, M.; Wang, C.; Li, D.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Qi, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, T.; et al. Yeast Culture Repairs Rumen Epithelial Injury by Regulating Microbial Communities and Metabolites in Sheep. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1305772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfen, J.; Carpinelli, N.; Del Pino, F.A.B.; Chapman, J.D.; Sharman, E.D.; Anderson, J.L.; Osorio, J.S. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Lactation Performance and Rumen Fermentation Profile and Microbial Abundance in Mid-Lactation Holstein Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 11580–11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Guasch, I.; Elcoso, G.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Castex, M.; Fàbregas, F.; Garcia-Fruitos, E.; Aris, A. Changes in Gene Expression in the Rumen and Colon Epithelia during the Dry Period through Lactation of Dairy Cows and Effects of Live Yeast Supplementation. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101, 2631–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfar, S. Understanding the Mechanism of Action of Indigenous Target Probiotic Yeast: Linking the Manipulation of Gut Microbiota and Performance in Animals. In Saccharomyces; Peixoto Basso, T., Carlos Basso, L., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2021 ISBN 978-1-83968-789-1.

- Dias, J.D.L.; Silva, R.B.; Fernandes, T.; Barbosa, E.F.; Graças, L.E.C.; Araujo, R.C.; Pereira, R.A.N.; Pereira, M.N. Yeast Culture Increased Plasma Niacin Concentration, Evaporative Heat Loss, and Feed Efficiency of Dairy Cows in a Hot Environment. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101, 5924–5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, L.; Kreck, E.M.; Tung, R.S.; Hession, A.O.; Sheperd, A.C.; Cohen, M.A.; Swain, H.E.; Leedle, J.A.Z. Effects of a Live Yeast Culture and Enzymes on In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation and Milk Production of Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science 1997, 80, 2045–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajagai. Yadav S Probiotics in Animal Nutrition: Production, Impact and Regulation; FAO animal production and health paper; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2016; ISBN 978-92-5-109333-7. [Google Scholar]

- De Melo Pereira, G.V.; De Oliveira Coelho, B.; Magalhães Júnior, A.I.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. How to Select a Probiotic? A Review and Update of Methods and Criteria. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36, 2060–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkala, B.Z.; DiGiacomo, K.; Alvarez Hess, P.S.; Gardiner, C.P.; Suleria, H.; Leury, B.J.; Dunshea, F.R. Evaluation of Legumes for Fermentability and Protein Fractions Using in Vitro Rumen Fermentation. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2023, 305, 115777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisan, V.; Pattarajinda, V.; Vichitphan, K.; Leesing, R. Isolation, Identification and Growth Determination of Lactic Acid-Utilizing Yeasts from the Ruminal Fluid of Dairy Cattle. Lett Appl Microbiol 2013, 57, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, Y.; Castillo, Y.; Ruiz, O.; Burrola, E.; Angulo, C. Feeding of Yeast (Candida Spp.) Improves in Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Fibrous Substrates. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2015, 14, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, O.; Castillo, Y.; Arzola, C.; Burrola, E.; Salinas, J.; Corral, A.; Hume, M.E.; Murillo, M.; Itza, M. Effects of Candida Norvegensis Live Cells on In Vitro Oat Straw Rumen Fermentation. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci 2015, 29, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Jin, W.; Mao, S. Isolation and Characterization of Ruminal Yeast Strain with Probiotic Potential and Its Effects on Growth Performance, Nutrients Digestibility, Rumen Fermentation and Microbiota of Hu Sheep. JoF 2022, 8, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B.F.; Ávila, C.L.S.; Bernardes, T.F.; Pereira, M.N.; Santos, C.; Schwan, R.F. Fermentation Profile and Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeasts of Rehydrated Corn Kernel Silage. J Appl Microbiol 2017, 122, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, H. H; Steingass, H Estimation of the Energetic Feed Value Obtained from Chemical Analysis and in Vitro Gas Production Using Rumen Fluid. Animal Research and Development 1988, 28, 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Lin, L.; Hu, F.; Zhu, W.; Mao, S. Disruption of Ruminal Homeostasis by Malnutrition Involved in Systemic Ruminal Microbiota-Host Interactions in a Pregnant Sheep Model. Microbiome 2020, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denman, S.E.; McSweeney, C.S. Development of a Real-Time PCR Assay for Monitoring Anaerobic Fungal and Cellulolytic Bacterial Populations within the Rumen: Real-Time PCR Assay of the Rumen Anaerobic Fungal Population. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2006, 58, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suntara, C.; Cherdthong, A.; Wanapat, M.; Uriyapongson, S.; Leelavatcharamas, V.; Sawaengkaew, J.; Chanjula, P.; Foiklang, S. Isolation and Characterization of Yeasts from Rumen Fluids for Potential Use as Additives in Ruminant Feeding. Veterinary Sciences 2021, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, G.F.C.; Carvalho, B.F.; Schwan, R.F.; Pereira, M.N.; Ávila, C.L.S. Diversity and Probiotic Characterisation of Yeast Isolates in the Bovine Gastrointestinal Tract. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2023, 116, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar Saadat, Y.; Yari Khosroushahi, A.; Movassaghpour, A.A.; Talebi, M.; Pourghassem Gargari, B. Modulatory Role of Exopolysaccharides of Kluyveromyces Marxianus and Pichia Kudriavzevii as Probiotic Yeasts from Dairy Products in Human Colon Cancer Cells. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 64, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelliah, R.; Ramakrishnan, S.R.; Prabhu, P.R.; Antony, U. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity and Probiotic Properties of Wild-strain Pichia Kudriavzevii Isolated from Frozen Idli Batter. Yeast 2016, 33, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mazcorro, J.F.; Ishaq, S.L.; Rodriguez-Herrera, M.V.; Garcia-Hernandez, C.A.; Kawas, J.R.; Nagaraja, T.G. Review: Are There Indigenous Saccharomyces in the Digestive Tract of Livestock Animal Species? Implications for Health, Nutrition and Productivity Traits. Animal 2020, 14, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.S.; Zhang, R.Y.; Zhu, W.Y.; Mao, S.Y. Effects of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis Challenges on Fermentation and Biogenic Amines in the Rumen of Dairy Cows. Livestock Science 2013, 155, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B. The Importance of pH in the Regulation of Ruminal Acetate to Propionate Ratio and Methane Production In Vitro. Journal of Dairy Science 1998, 81, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Song, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, P.; Cao, A.; Ni, Y. Bile Acids Supplementation Improves Colonic Mucosal Barrier via Alteration of Bile Acids Metabolism and Gut Microbiota Composition in Goats with Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 287, 117313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberberg, M.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Commun, L.; Mialon, M.M.; Monteils, V.; Mosoni, P.; Morgavi, D.P.; Martin, C. Repeated Acidosis Challenges and Live Yeast Supplementation Shape Rumen Microbiota and Fermentations and Modulate Inflammatory Status in Sheep. Animal 2013, 7, 1910–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrune, M.; Bach, A.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.; Stern, M.D.; Linn, J.G. Effects of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae on Ruminal pH and Microbial Fermentation in Dairy Cows. Livestock Science 2009, 124, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraretto, L.F.; Shaver, R.D.; Bertics, S.J. Effect of Dietary Supplementation with Live-Cell Yeast at Two Dosages on Lactation Performance, Ruminal Fermentation, and Total-Tract Nutrient Digestibility in Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2012, 95, 4017–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A.R.; Kairenius, P.; Stefański, T.; Leskinen, H.; Comtet-Marre, S.; Forano, E.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Shingfield, K.J. Effect of Camelina Oil or Live Yeasts (Saccharomyces Cerevisiae) on Ruminal Methane Production, Rumen Fermentation, and Milk Fatty Acid Composition in Lactating Cows Fed Grass Silage Diets. Journal of Dairy Science 2015, 98, 3166–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Carvalho, B.F.; Mantovani, H.C.; Schwan, R.F.; Ávila, C.L.S. Identification and Characterization of Yeasts from Bovine Rumen for Potential Use as Probiotics. J Appl Microbiol 2019, 127, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wen, H.; Wan, H.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Li, B.; et al. Yeast Probiotic and Yeast Products in Enhancing Livestock Feeds Utilization and Performance: An Overview. JoF 2022, 8, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B.E.; Tsai, T.-C.; Yang, H.; Perez, V.; Holzgraefe, D.; Chewning, J.; Frank, J.W.; Maxwell, C.V. Influence of a Whole Yeast Product ( Pichia Guilliermondii ) Fed throughout Gestation and Lactation on Performance and Immune Parameters of the Sow and Litter. Journal of Animal Science 2019, 97, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shah, A.M.; Wang, Z.; Fan, X. Potential Protective Effects of Thiamine Supplementation on the Ruminal Epithelium Damage during Subacute Ruminal Acidosis. Animal Science Journal 2021, 92, e13579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Zhou, A.; Yang, H.; Kang, K.; Ahmed, S.; Li, B.; Farooq, U.; Hou, F.; Wang, C.; et al. Effects of Yeast Culture on in Vitro Ruminal Fermentation and Microbial Community of High Concentrate Diet in Sheep. AMB Expr 2024, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desnoyers, M.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Bertin, G.; Duvaux-Ponter, C.; Sauvant, D. Meta-Analysis of the Influence of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Supplementation on Ruminal Parameters and Milk Production of Ruminants. Journal of Dairy Science 2009, 92, 1620–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Li, Y.; Mao, K.; Zang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qiu, Q.; Qu, M.; Ouyang, K. Effects of Rumen-Protected Creatine Pyruvate on Meat Quality, Hepatic Gluconeogenesis, and Muscle Energy Metabolism of Long-Distance Transported Beef Cattle. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 904503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Gao, X.; Duan, J.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.; He, J.; Huo, N.; Pei, C.; Li, H.; Gu, S. Effects of Yeasts on Rumen Bacterial Flora, Abnormal Metabolites, and Blood Gas in Sheep with Induced Subacute Ruminal Acidosis. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2021, 280, 115042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, L.L.; Yoon, I.; Plaizier, J.C.; Khafipour, E. Postbiotics from Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Fermentation Stabilize Microbiota in Rumen Liquid Digesta during Grain-Based Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA) in Lactating Dairy Cows. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 2024, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.; Liu, Y.; Kong, F.; Guo, C.; Dong, C.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, W. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Culture’s Dose–Response Effects on Ruminal Nutrient Digestibility and Microbial Community: An In Vitro Study. Fermentation 2023, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.-R.; Whon, T.W.; Bae, J.-W. Proteobacteria: Microbial Signature of Dysbiosis in Gut Microbiota. Trends in Biotechnology 2015, 33, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.S.; Wang, R.; Ma, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Jiao, J.Z.; Zhang, Z.G.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Le Yi, K.; Zhang, B.Z.; Long, L.; et al. Dietary Selection of Metabolically Distinct Microorganisms Drives Hydrogen Metabolism in Ruminants. The ISME Journal 2022, 16, 2535–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, M.S.; Cormican, P.; Keogh, K.; O’Connor, A.; O’Hara, E.; Palladino, R.A.; Kenny, D.A.; Waters, S.M. Illumina MiSeq Phylogenetic Amplicon Sequencing Shows a Large Reduction of an Uncharacterised Succinivibrionaceae and an Increase of the Methanobrevibacter Gottschalkii Clade in Feed Restricted Cattle. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Diet ingredients % | Nutritional Composition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa | 70 | ME (MJ/kg) | 8.81 |

| Corn | 14 | CP(%) | 10.81 |

| Soybean meal | 13 | NDF(%) | 44.82 |

| Calcium hydrophosphate | 1.42 | ADF(%) | 23.89 |

| Limestone | 0.58 | Starch(%) | 23.16 |

| NaCl | 0.5 | Calcium(%) | 0.81 |

| Premix1 | 0.5 | Phosphorus(%) | 0.47 |

| Total | 100 |

| Yeast species | Number of isolates | Strain ID |

|---|---|---|

| Candida rugosa | 19 | NJ(1, 2, 5-9, 12, 18, 28-32, 36, 45, 55-57) |

| Pichia kudriavzevii | 12 | NJ(3, 4, 14, 21, 33-35, 41, 44, 50, 58, 59) |

| Trichosporon asahii | 9 | NJ(11, 15-17, 22, 38, 43, 46, 52) |

| Candida tropicalis | 6 | NJ(13, 24, 40, 47, 49, 51) |

| Magnusiomyces capitatus | 4 | NJ(19, 20) 25, 53) |

| Candida pararugosa | 4 | NJ(10, 26, 27, 54) |

| Meyerozyma caribbica | 3 | NJ(37, 39, 48) |

| Sporidiobolus pararoseus | 1 | NJ(42) |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | 1 | NJ(23) |

| Culture time (h) | Groups | SEM | p-values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | NJ-5 | NJ-12 | NJ-14 | NJ-36 | NJ-46 | |||

| pH | 5.58b | 5.65a | 5.61ab | 5.57b | 5.61ab | 5.58b | 0.05 | 0.040 |

| Total VFA, mmol/L | 100.13bc | 101.02ab | 100.82abc | 101.41a | 100.64abc | 100.06c | 0.28 | 0.003 |

| Acetate(%) | 52.61c | 53.34a | 53.23ab | 52.72bc | 52.73bc | 52.84abc | 0.16 | 0.003 |

| Propionate(%) | 27.7c | 28.37b | 28.39ab | 28.81a | 28.45ab | 28.69ab | 0.13 | 0.000 |

| Butynate(%) | 13.87 | 13.52 | 13.56 | 13.47 | 13.66 | 13.40 | 0.17 | 0.155 |

| Isobutyrate(%) | 1.62a | 1.40b | 1.38b | 1.42b | 1.45b | 1.45b | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| Valerate(%) | 2.63a | 1.98c | 1.97c | 2.08bc | 2.19b | 2.04bc | 0.06 | 0.000 |

| Isovalerate(%) | 1.56 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1.50 | 1.52 | 1.50 | 0.04 | 0.654 |

| Acetate/Propionate ratio | 1.90a | 1.88ab | 1.88ab | 1.83c | 1.85bc | 1.84bc | 0.01 | 0.000 |

| Culture time (h) | Groups | SEM | p-values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | LYC | MYC | HYC | |||

| 6 | 5.89b | 5.92ab | 6.07a | 6.03a | 0.06 | 0.038 |

| 12 | 5.85b | 5.84b | 5.85b | 6.00a | 0.03 | 0.001 |

| 24 | 5.69b | 5.84a | 5.82a | 5.88a | 0.05 | 0.040 |

| Culture time (h) | Groups | SEM | p-values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | LYC | MYC | HYC | |||

| Total VFA,mmol/L | 75.69b | 76.00ab | 76.09ab | 76.36a | 0.16 | 0.018 |

| Acetate(%) | 53.53c | 54.56b | 55.09b | 56.01a | 0.16 | 0.000 |

| Propionate(%) | 28.62a | 27.41b | 27.19b | 26.70c | 0.10 | 0.000 |

| Butynate(%) | 14.46a | 14.62a | 14.43a | 14.09b | 0.10 | 0.005 |

| Isobutyrate(%) | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 0.214 |

| Valerate(%) | 1.20 | 1.29 | 1.21 | 1.12 | 0.05 | 0.090 |

| Isovalerate(%) | 1.05 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.04 | 0.543 |

| Acetate/Propionate ratio | 1.97 | 1.99 | 1.92 | 1.91 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s) . MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).