Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

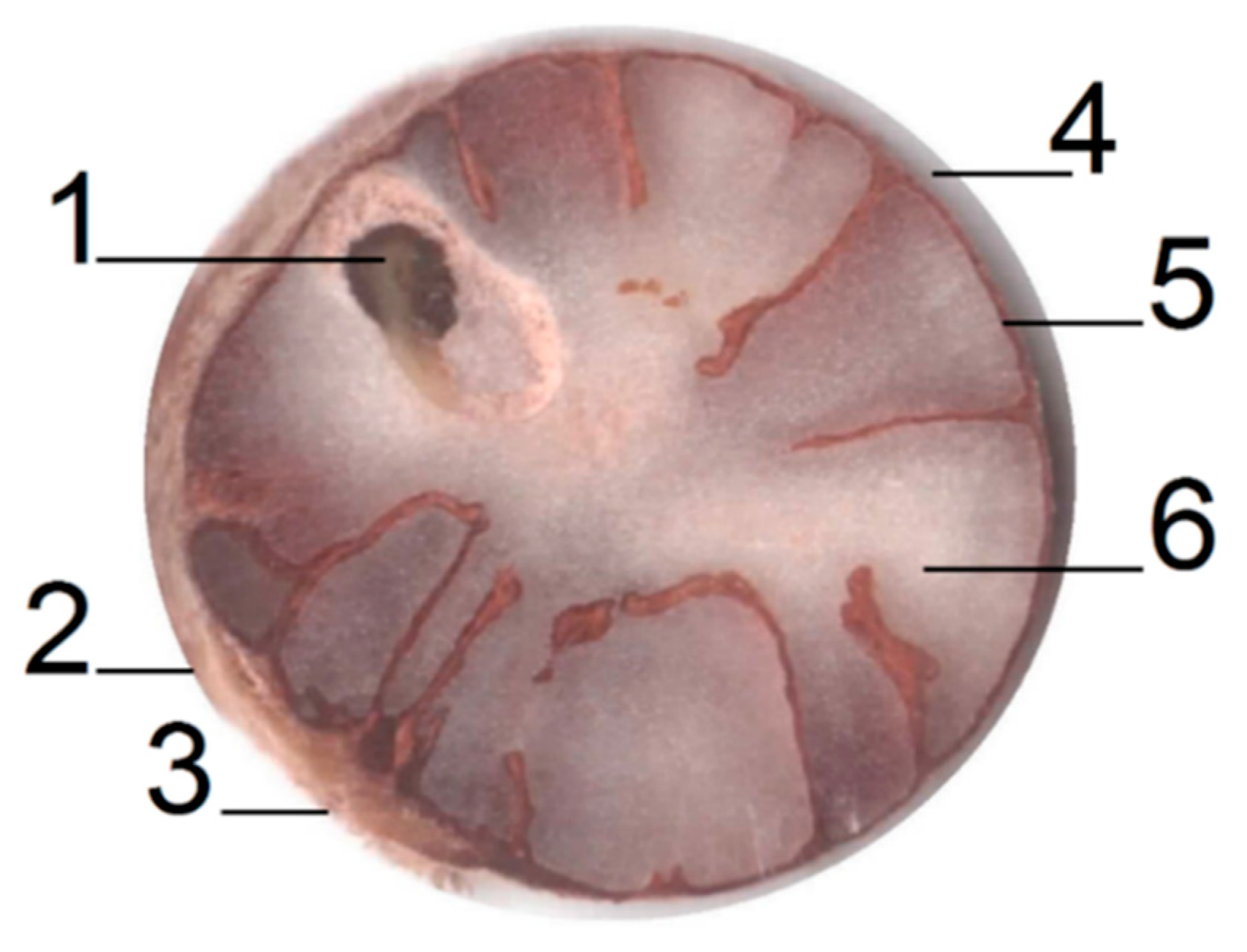

2.2. Pre-Treatment of Açaí Seeds (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.)

2.3. Characterization of Açai (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart.) Seeds in Nature

2.3.1. Centesimal and Elemental Characterization of Açai (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart.) Seeds in Nature

2.3.2. Centesimal and Elemental Characterization of Açai (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart.) Seeds in Nature

2.4. Experimental Procedure for in Natura Açaí Seeds

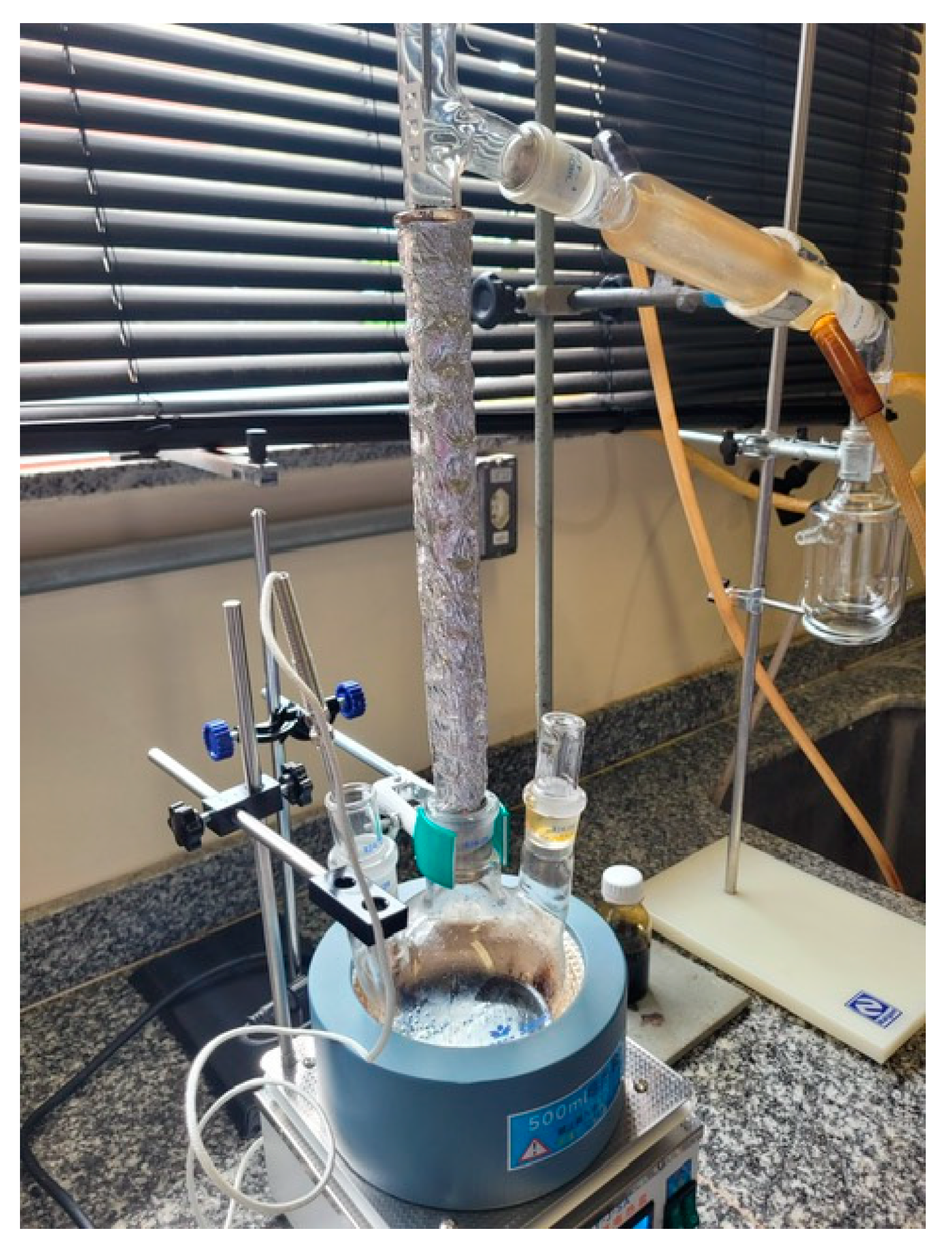

2.4.1. Thermal Pyrolysis Process

2.4.2. Distillation: Experimental Apparatus and Procedures

2.5. Physicochemical and Chemical Composition of Bio-Oils and Distillation Fractions

2.5.1. Physicochemical Analysis of Bio-Oils and Distillation Fractions

2.5.2. GC-MS of Bio-Oil

2.6. Material Balance Resulting from the Pyrolysis of Raw Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Seeds

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Centesimal and Elemental Characterization of Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart.) Seeds

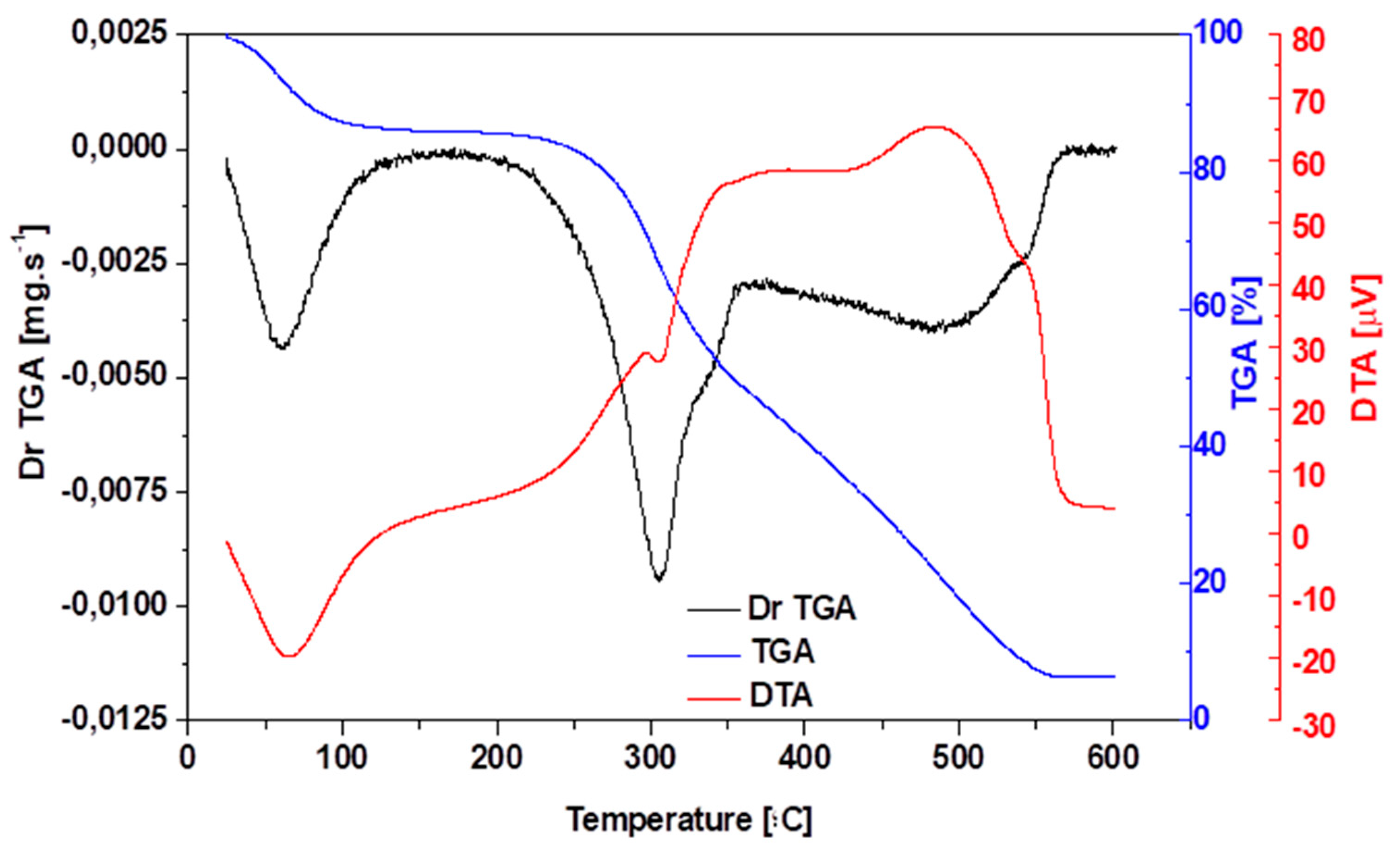

3.2. Thermo-Gravimetric (TG/DTG) Analysis of Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart) Seeds in Nature

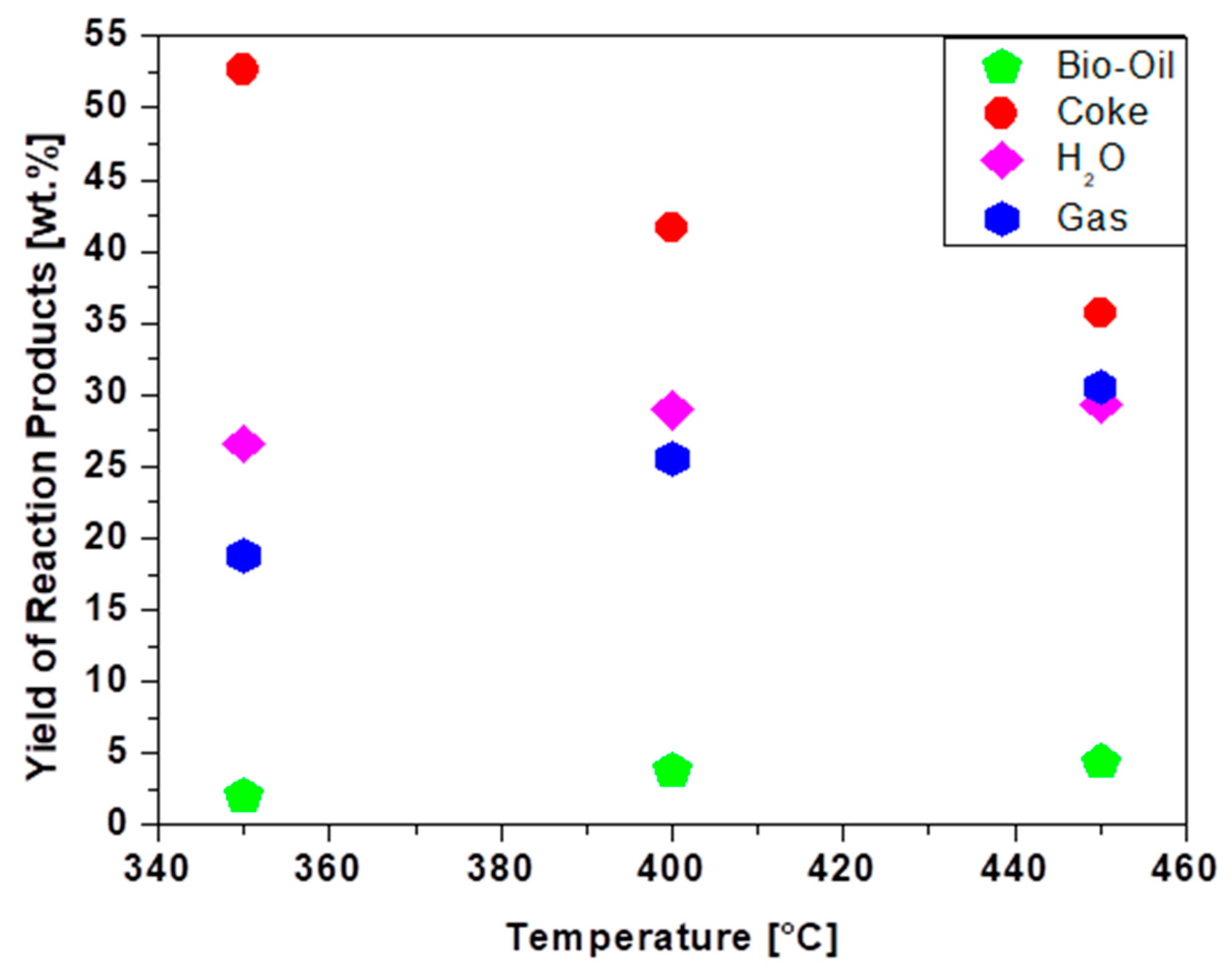

3.3. Process Parameters and Overall Steady-State Material Balances of Dried Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart.) Seed Pyrolysis

3.4. Physicochemical Characterization of Bio-Oils

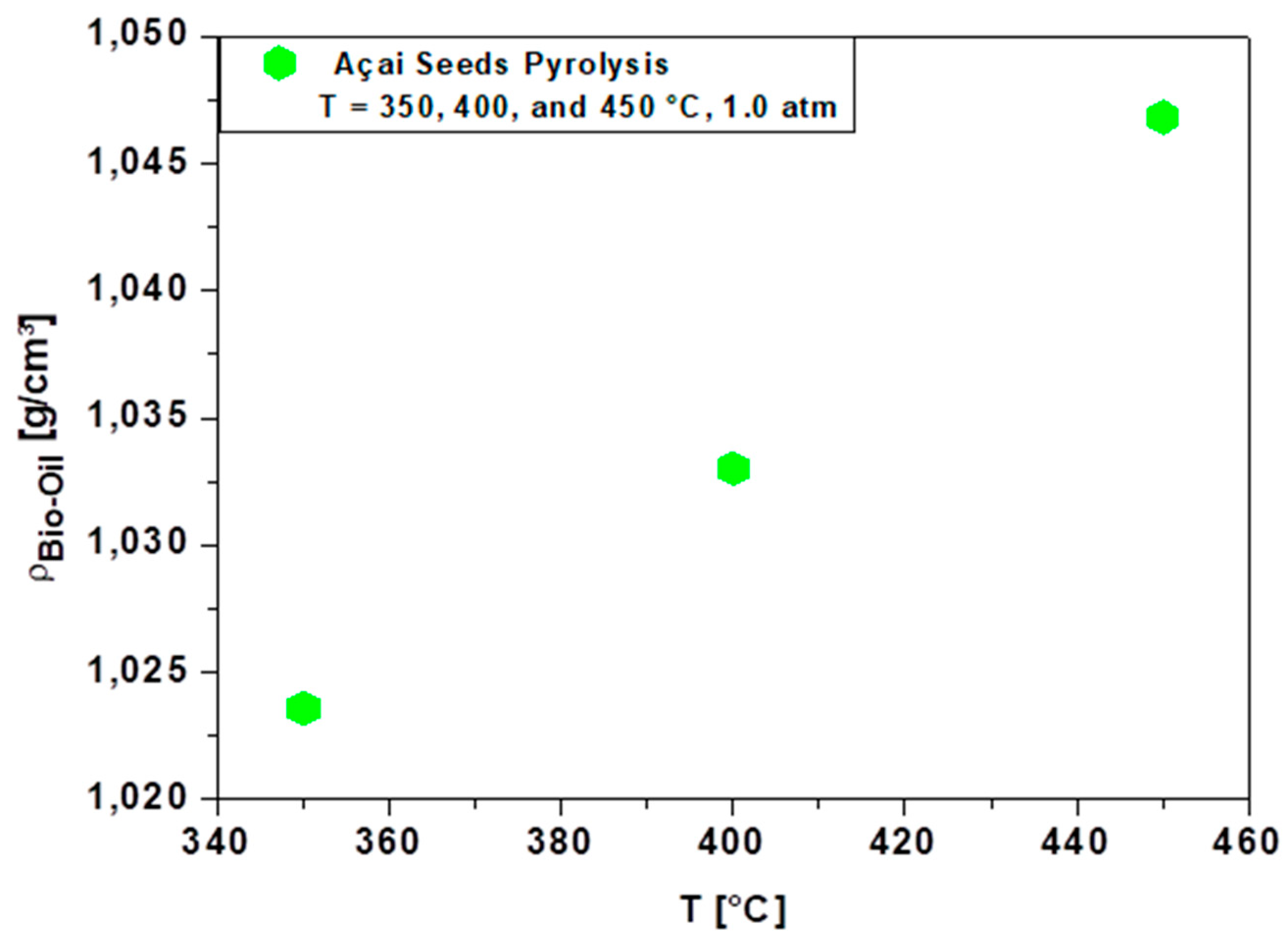

3.4.1. Density of Bio-Oil

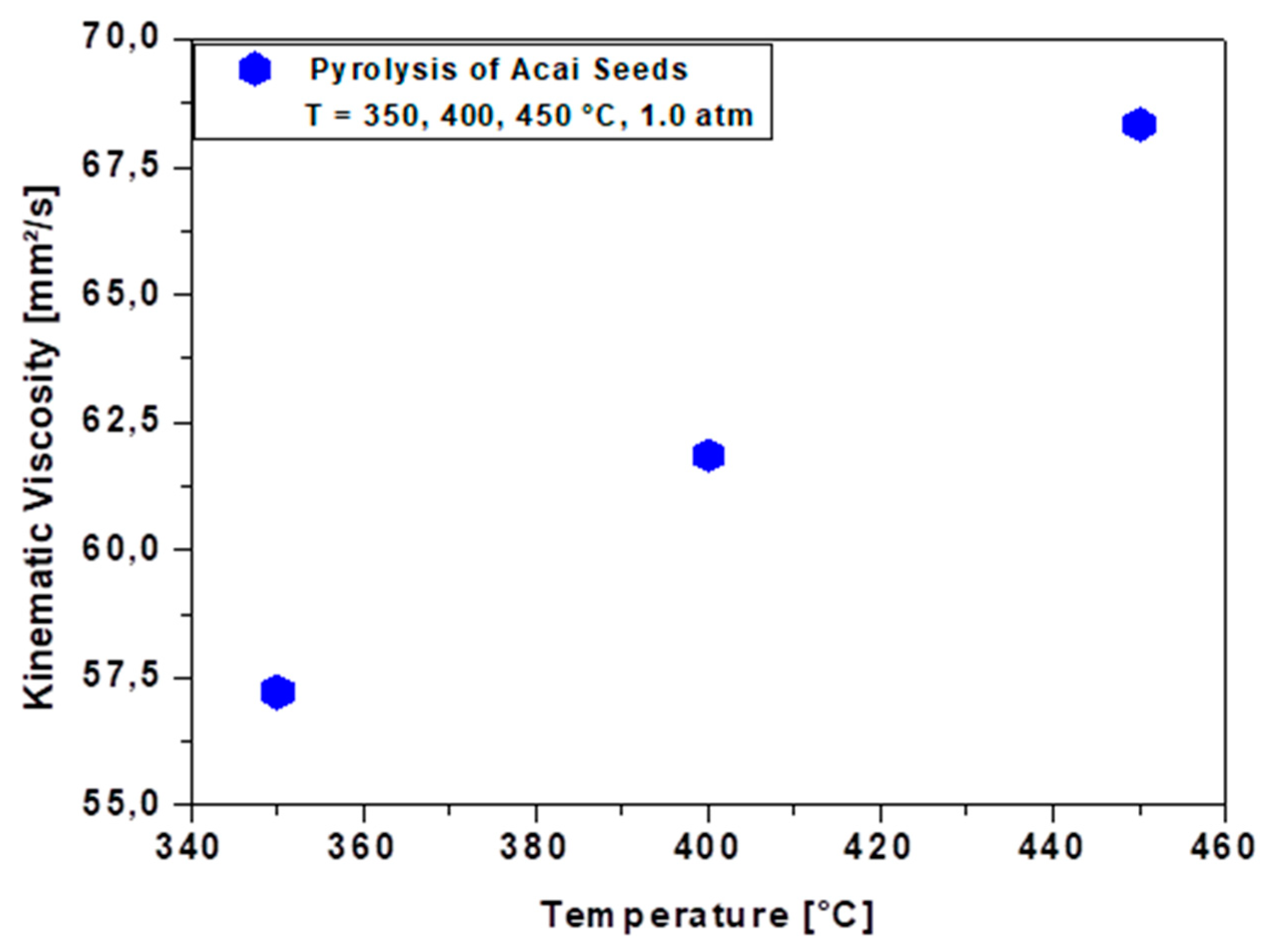

3.4.2. Viscosity of Bio-Oil

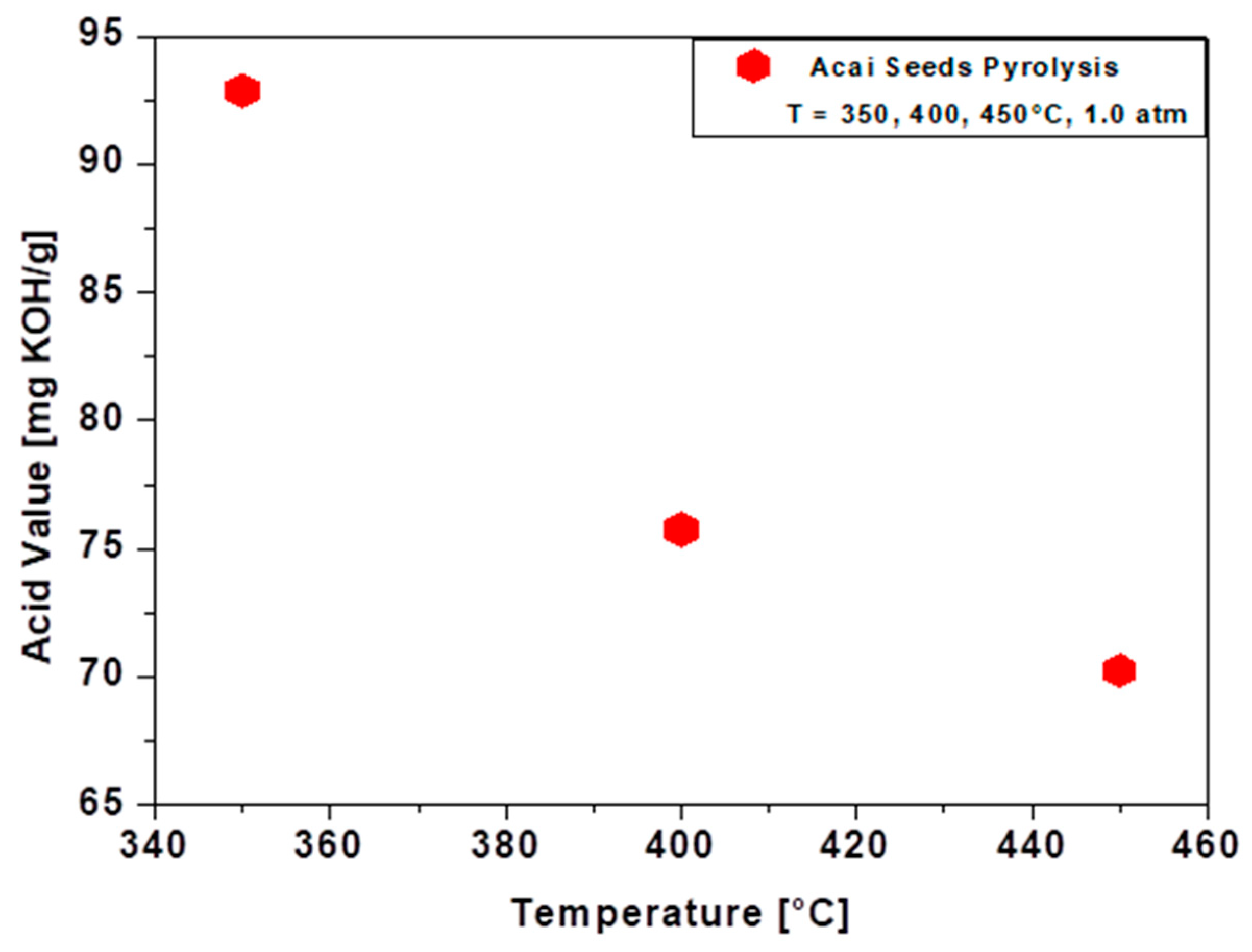

3.4.3. Acid Value of Bio-Oil

3.5. Mass Balances and Yields (Distillates and Raffinate) by Fractional Distillation of Bio-Oil Obtained by Pyrolysis of Dried Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart.) Seeds

3.5.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Distillation Fractions

3.6. Mass Balances and Yields (Distillates and Raffinate) by Fractional Distillation of Bio-Oil Obtained by Pyrolysis of Dried Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea, Mart.) Seeds

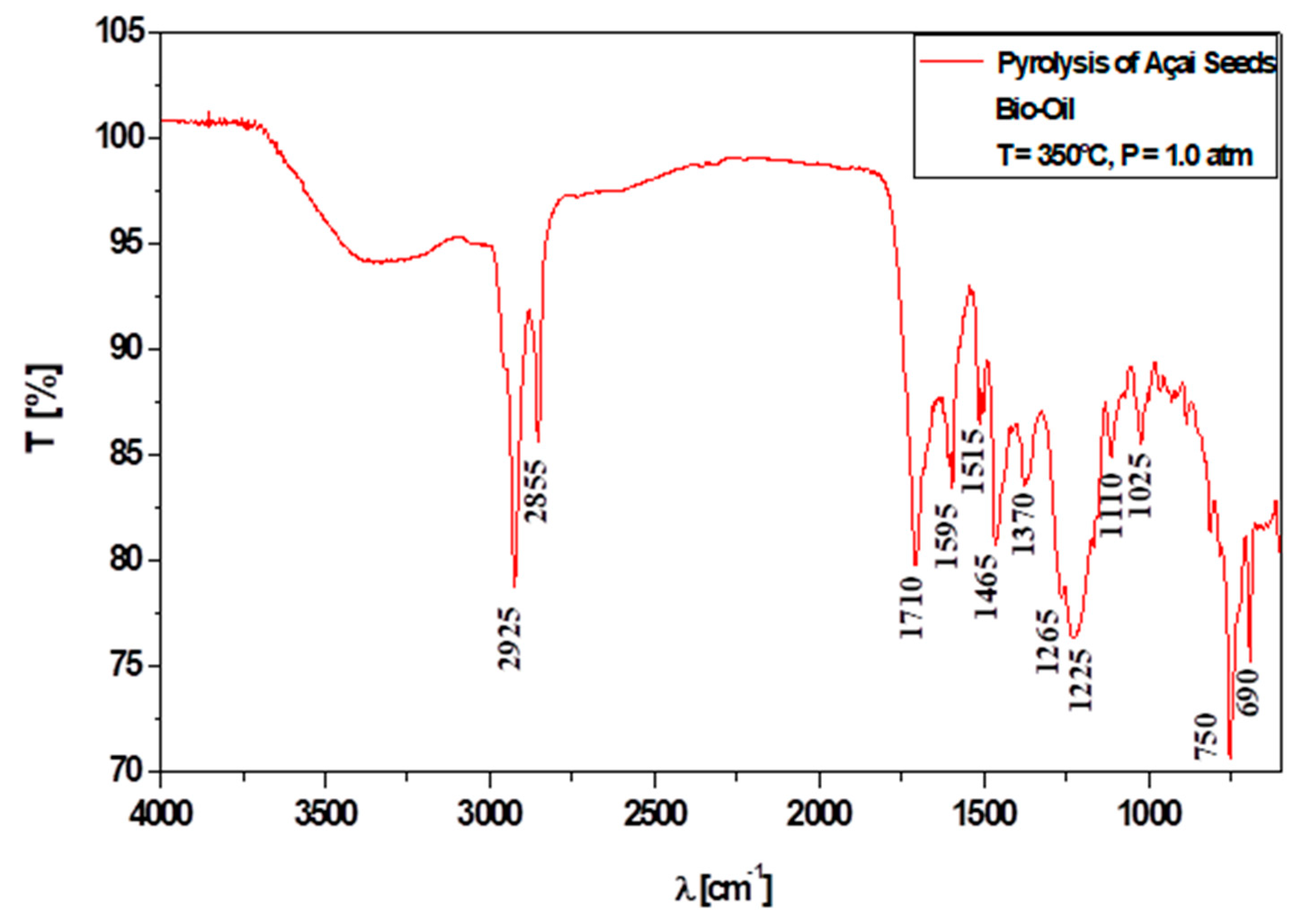

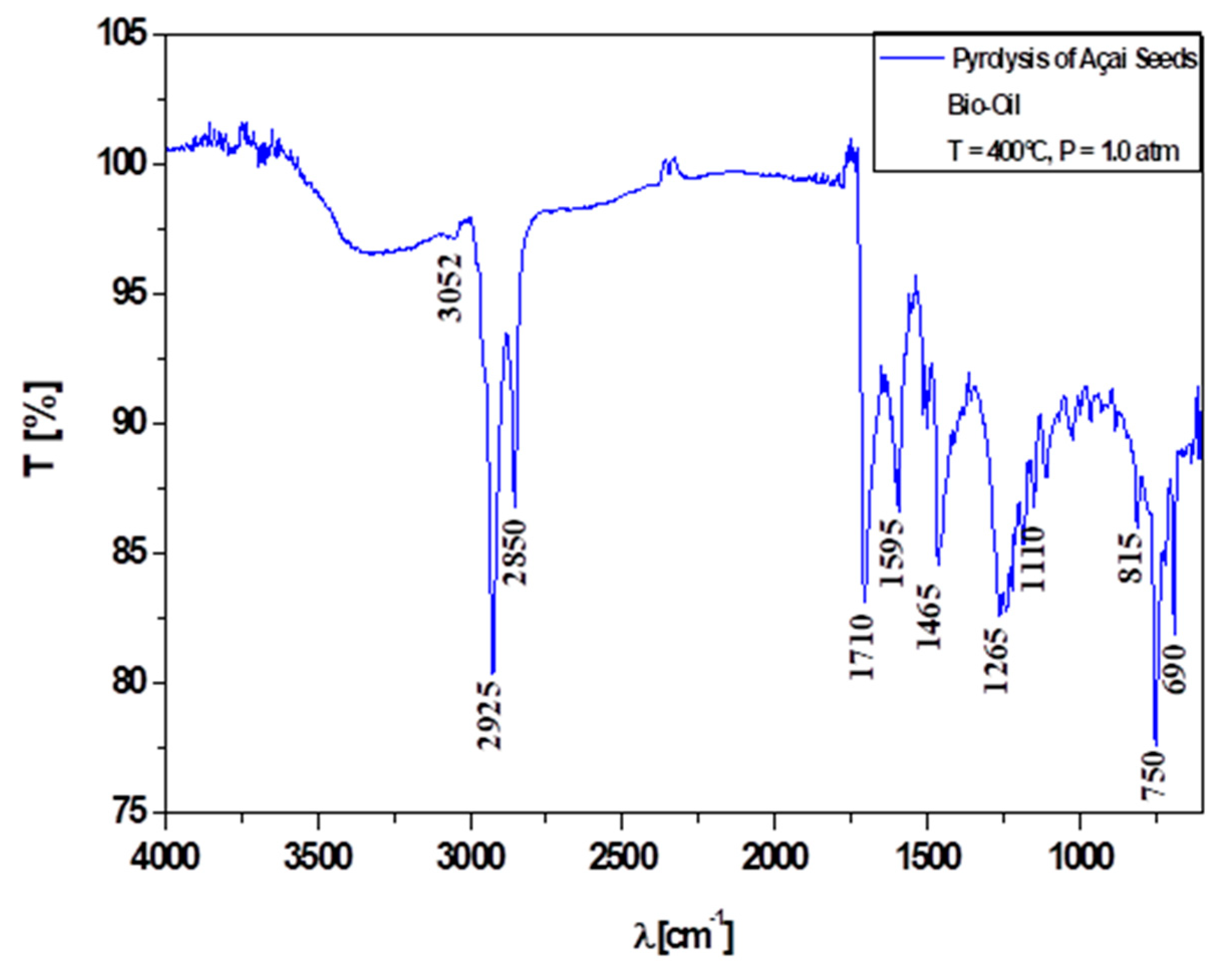

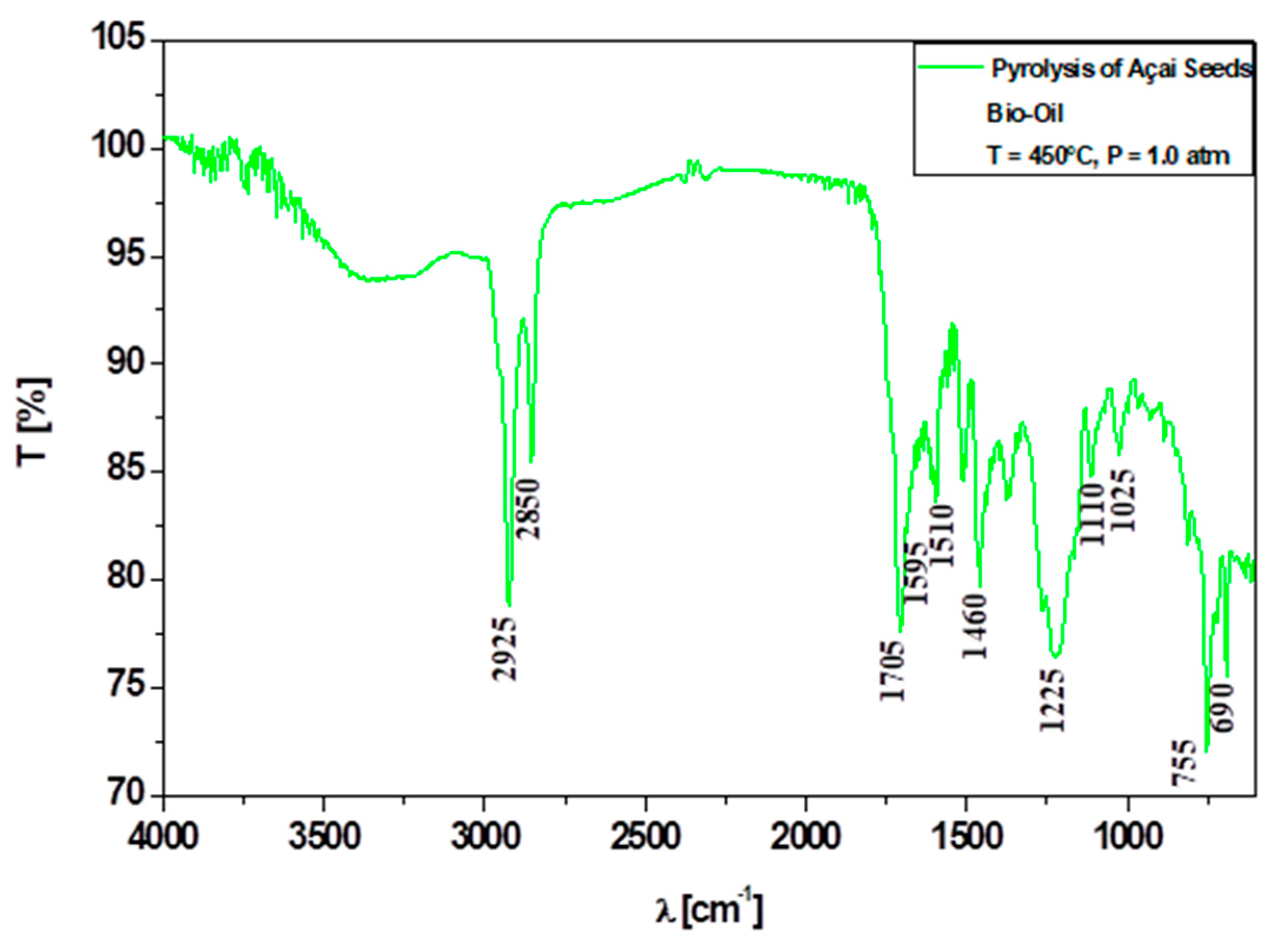

3.6.1. Qualitative Analyses of Chemical Functions of Bio-Oils by FT-IR Spectroscopy

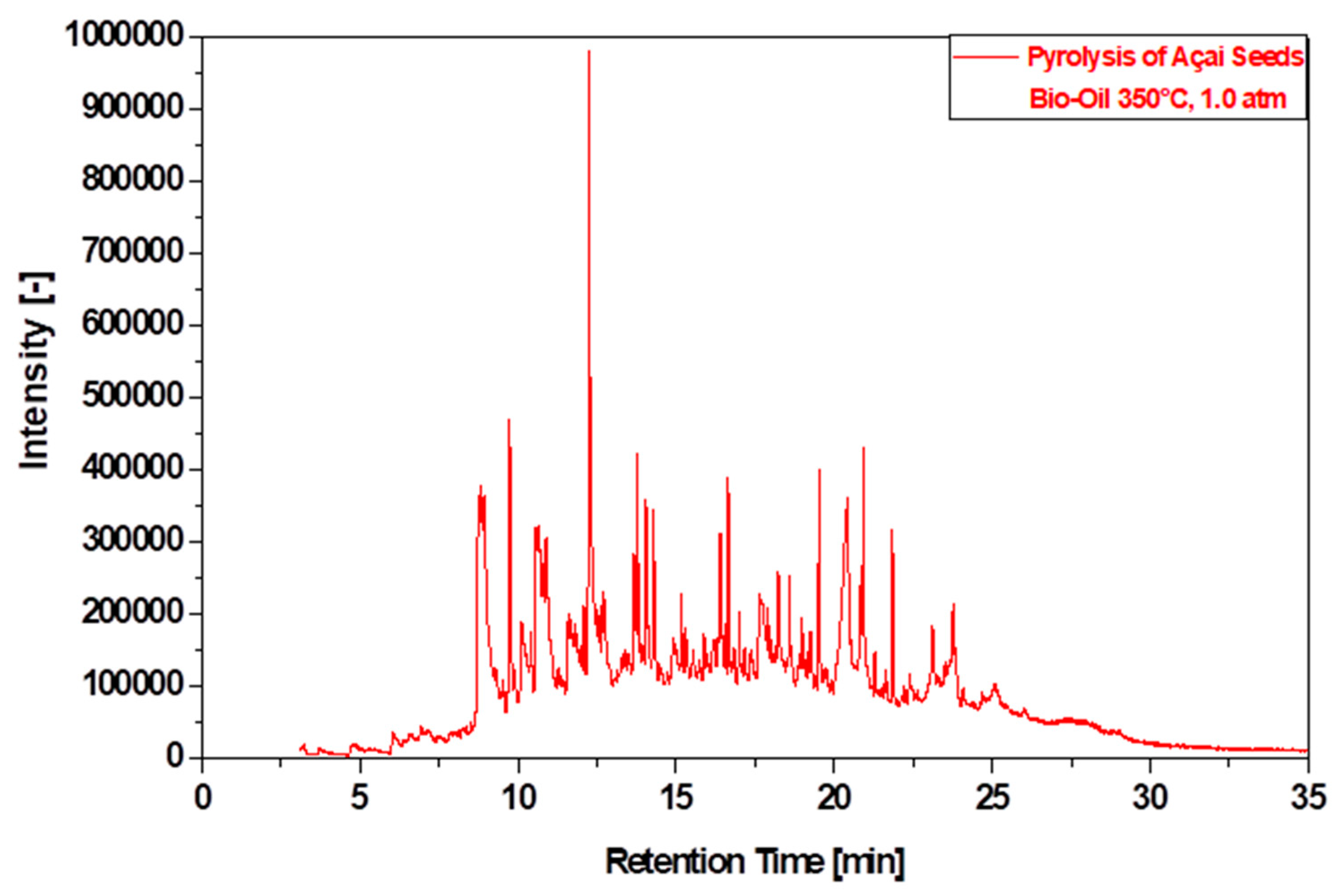

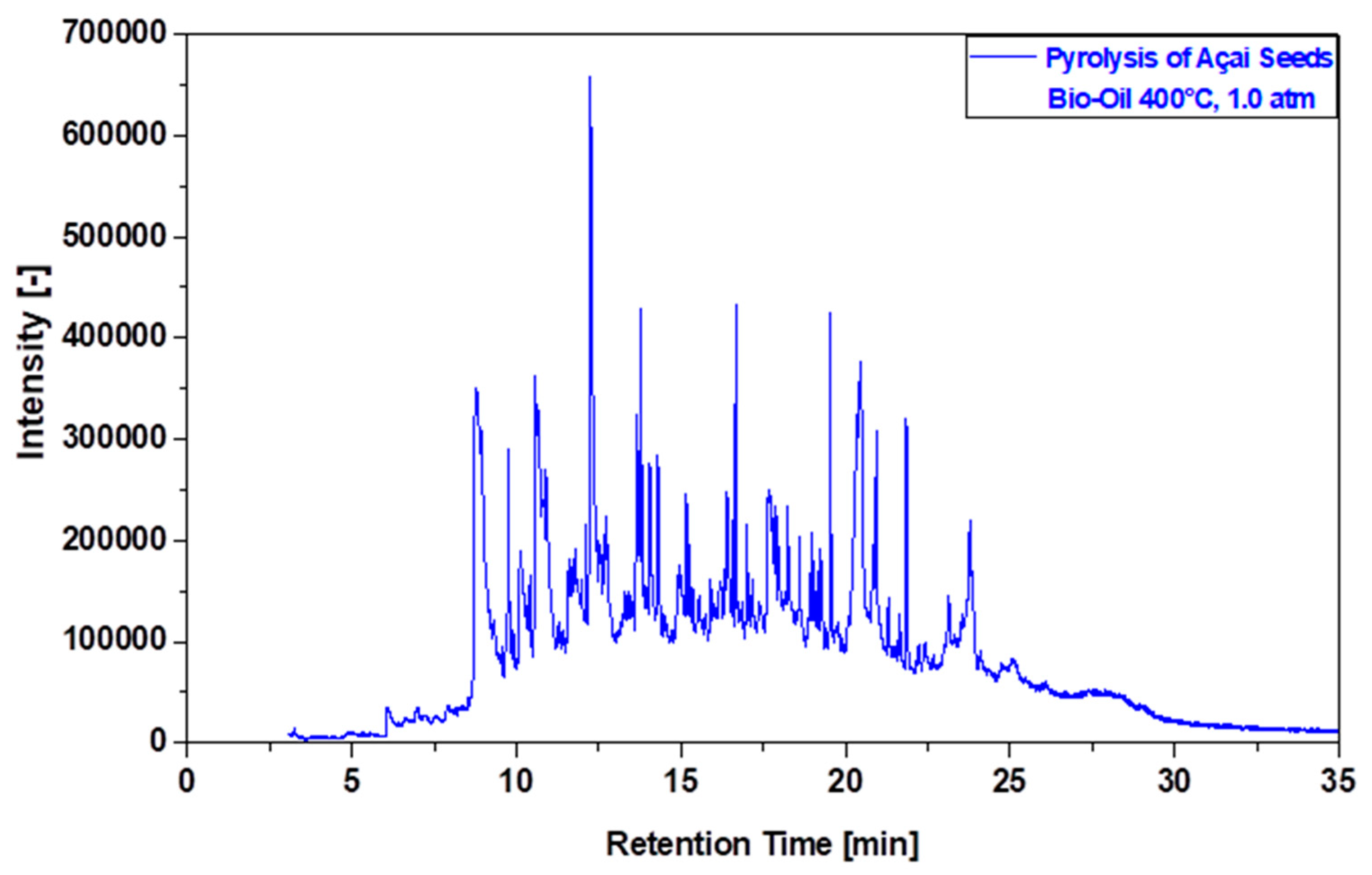

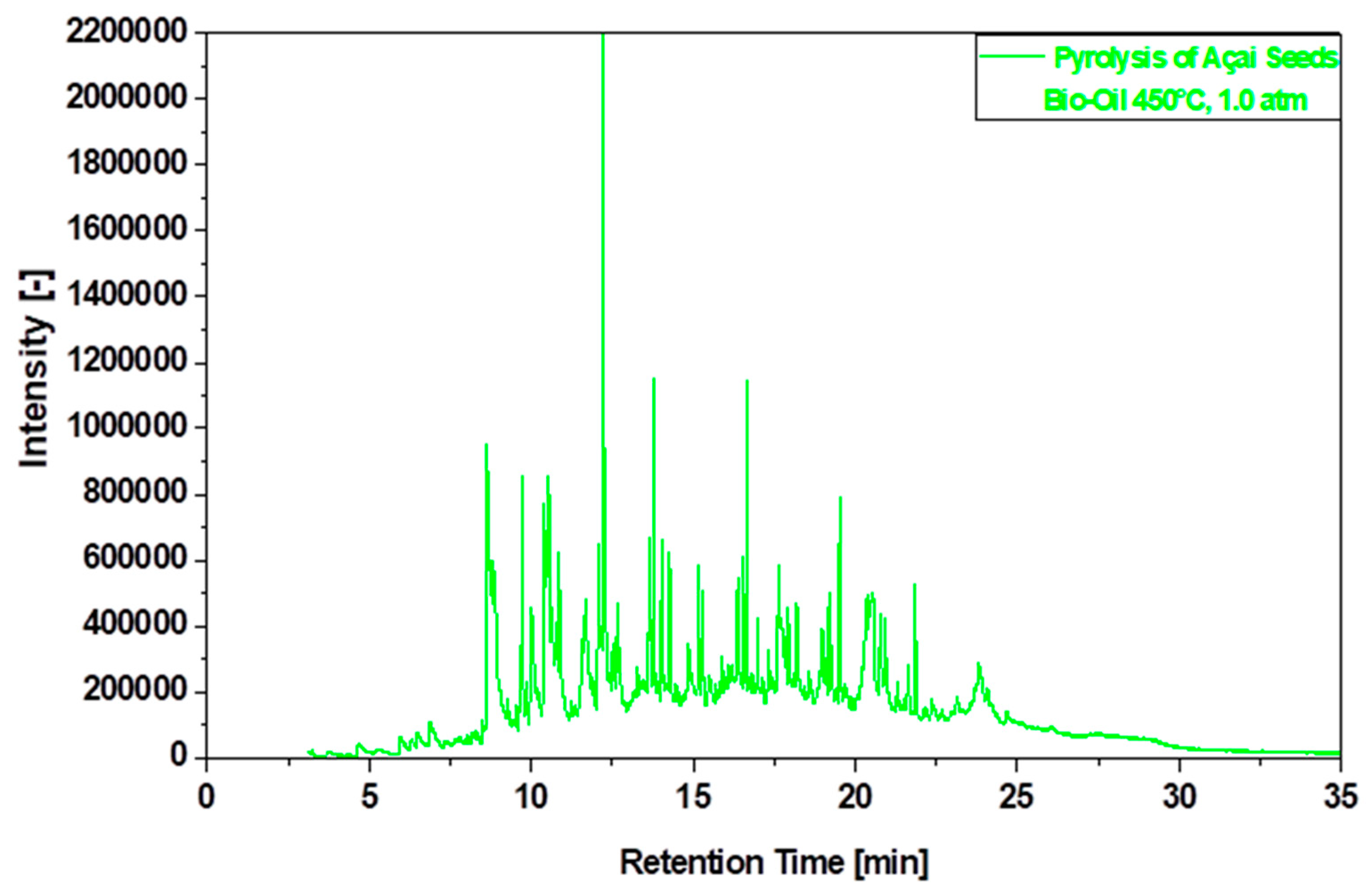

3.6.2. Compositional Analyses of Bio-Oil by GC-MS

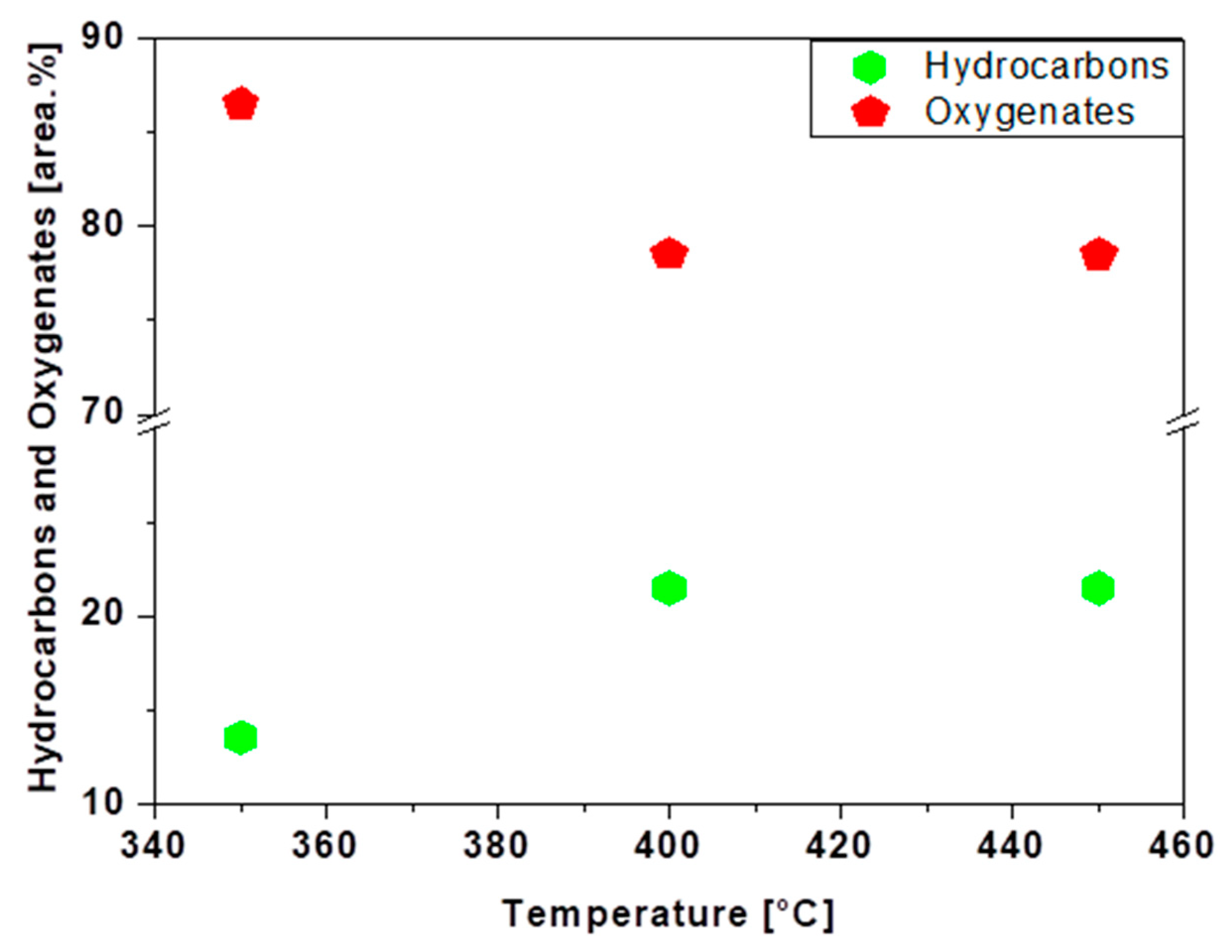

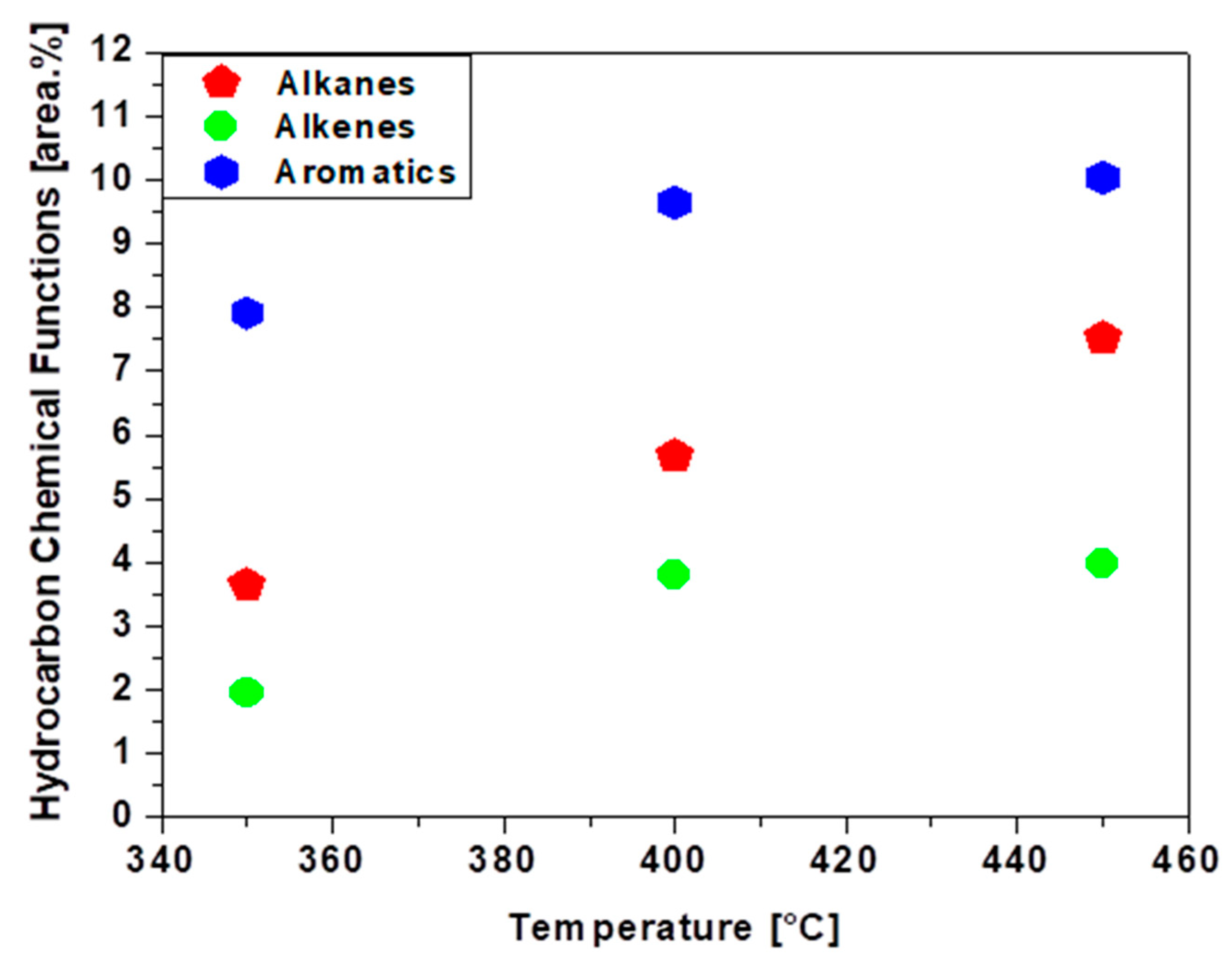

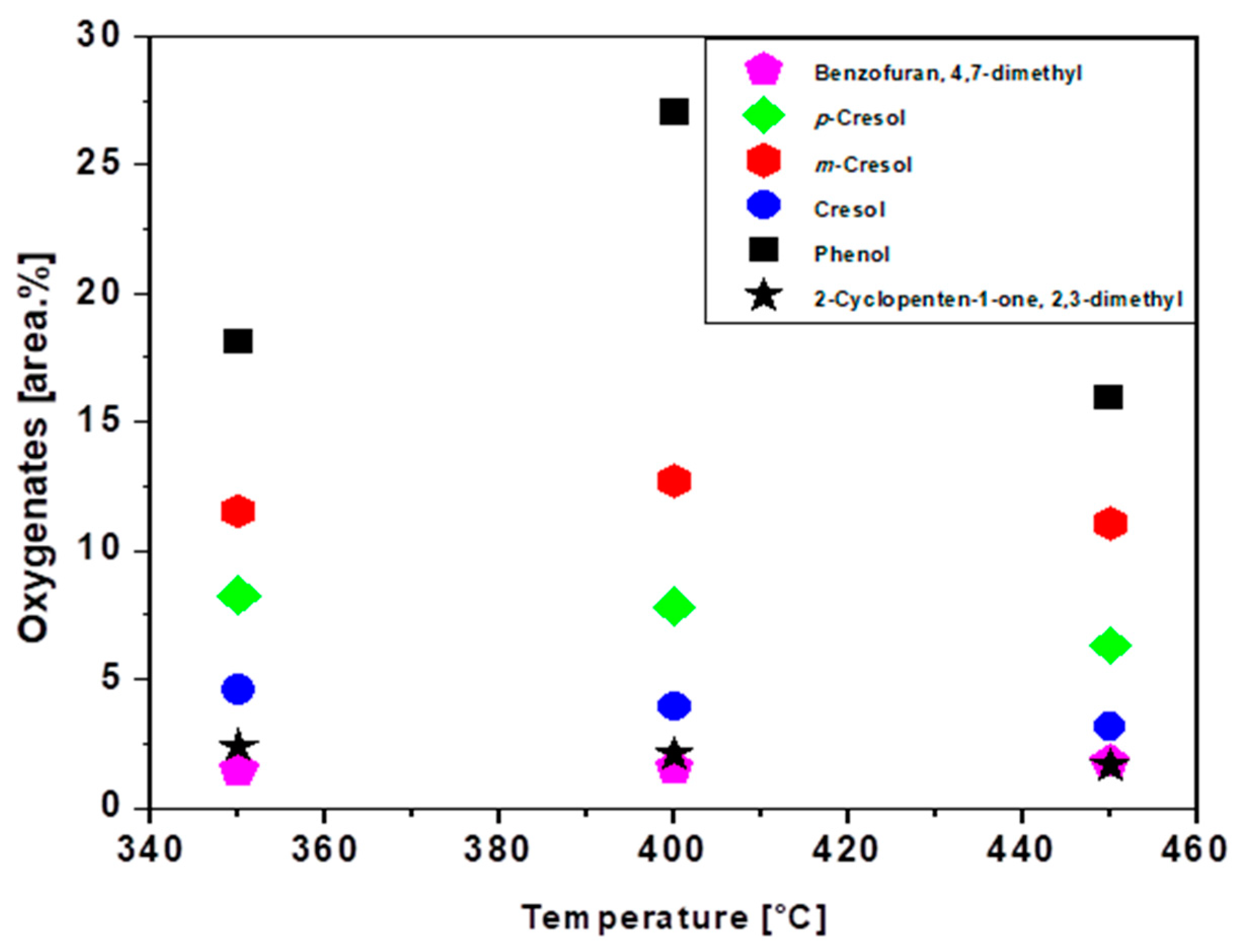

3.7. luence of Temperature on the Chemical Composition of Bio-Oils

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonny Everson Scherwinski-Pereira; Rodrigo da Silva Guedes; Ricardo Alexandre da Silva; Paulo César Poeta Fermino Jr.; Zanderluce Gomes Luis; Elínea de Oliveira Freitas. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in açaí palm (Euterpe oleracea). Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult (2012) 109:501–508. [CrossRef]

- Alexander G. Schauss; Xianli Wu; Ronald L. Prior; Boxin Ou; Dinesh Patel; Dejian Huang; James P. Kababick. Phytochemical and Nutrient Composition of the Freeze-Dried Amazonian Palm Berry, Euterpe oleraceae Mart. (Acai). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 22, 8598-8603. [CrossRef]

- Sara Sabbe; Wim Verbeke; Rosires Deliza; Virginia Matta; Patrick Van Damme. Effect of a health claim and personal characteristics on consumer acceptance of fruit juices with different concentrations of açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). Appetite 53 (2009) 84–92. [CrossRef]

- Lisbeth A. Pacheco-Palencia; Christopher E. Duncan; Stephen T. Talcott. Phytochemical composition and thermal stability of two commercial açai species, Euterpe oleracea and Euterpe precatoria. Food Chem. 115 (2009) 1199-1205. [CrossRef]

- Eduardo S. Brondízio; Carolina A. M. Safar; Andréa D. Siqueira. The urban market of Açaí fruit (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) and rural land use change: Ethnographic insights into the role of price and land tenure constraining agricultural choices in the Amazon estuary. Urban Ecosystems (2002) 6-67. [CrossRef]

- Elisabeth dos Santos Bentes; Alfredo Kingo Oyama Homma; César Augusto Nunes dos Santos. Exportações de Polpa de Açaí do Estado do Pará: Situação Atual e Perspectivas. In: Anais Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de Economia, Administração e Sociologia Rural, 55, Santa Maria, RS-Brazil, 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319465735_Exportacoes_de_Polpa_de_Acai_do_Estado_do_Para_Situacao_Atual_e_Perspectivas.

- Ana Victoria da Costa Almeida; Ingrid Moreira Melo; Isis Silva Pinheiro; Jessyca Farias Freitas; André Cristiano Silva Melo. Revalorização do caroço de açaí em uma beneficiadora de polpas do município de Ananindeua/PA: proposta de estruturação de um canal reverso orientado pela PNRS e logística reversa. GEPROS. Gestão da Produção, Operações e Sistemas, Bauru, Ano 12, Nº 3, jul-set/2017, 59-83. [CrossRef]

- Claudio Ramalho Townsend; Newton de Lucena Costa; Ricardo Gomes de Araújo Pereira; Clóvis C. Diesel Senger. Características químico-bromatológica do caroço de açaí. COMUNICADO TÉCNICO Nº 193 (CT/193), EMBRAPA-CPAF Rondônia, ago./01, 1-5. ISSN 0103-9458. https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/100242/1/Cot193-acai.pdf.

- Carlos Fioravanti. Açaí: Do pé para o lanche. Revista Pesquisa Fapesp, Vol. 203, Janeiro de 2013, 64-68. https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/2013/01/11/folheie-a-edicao-203/.

- Antônio Cordeiro de Santana; Ádamo Lima de Santana; Ádina Lima de Santana; Marcos Antônio Souza dos Santos; Cyntia Meireles de Oliveira. Análise Discriminante Múltipla do Mercado Varejista de Açaí em Belém do Pará. Rev. Bras. Frutic., Jaboticabal - SP, Vol. 36, N°. 3, 532- 541, Setembro 2014. [CrossRef]

- José Dalton Cruz Pessoa; Paula Vanessa da Silva e Silva. Effect of temperature and storage on açaí (Euterpe oleracea) fruit water uptake: simulation of fruit transportation and pre-processing. Fruits, 2007, Vol. 62, 295–302; [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro M. A. Estudo da hidrólise enzimática do caroço de açaí (Euterpe oleracea, Mart) para a produção de etanol. Dissertação de Mestrado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Química, UFPA-Brazil. Marcio de Andrade Cordeiro; 2016.

- Tamiris Rio Branco da Fonseca; Taciana de Amorim Silva; Mircella Marialva Alecrim; Raimundo Felipe da Cruz Filho; Maria Francisca Simas Teixeira. Cultivation and nutritional studies of an edible mushroom from North Brazil. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2015;9(30):1814-1822.

- Kababacknik A; Roger H. Determinação do poder calorífico do caroço do açaí em três distintas umidades, 38th Congresso Brasileiro de Química, São Luiz-MA-Brazil; 1998.

- Altman R. F. A. O Caroço de açaí (Euterpe oleracea, Mart). Vol. 31. Belém-Pa, Brasil: Boletim Técnico do Instituto Agronômico do Norte; 1956, 109-111.

- Michael Stöcker. Biofuels and Biomass-To-Liquid Fuels in the Biorefinery: Catalytic Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass using Porous Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9200–9211. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. L.F.; Martins, D. U.; Iha, O. K.; Ribeiro R. A.M.; Quirino R. L.; Suarez P. A.Z. Agro-industrial residues as low-price feedstock for diesel-like fuel production by thermal cracking. Bioresource Technology 101 (2010) 6157–6162. [CrossRef]

- Diadem Özçimen; Ayşegül Ersoy-Meriçboyu. Characterization of biochar and bio-oil samples obtained from carbonization of various biomass materials. Renewable Energy, June 2010;35(6):1319-1324. [CrossRef]

- David L. Nelson; Michael M. Cox: Leininger Principles of Biochemistry. 5th Edition. Freeman, New York, NY 2008, ISBN: 978-0-7167-7108-1.

- Kelli G. Roberts; Brent A. Glory; Stephen Joseph; Norman R. Scott; Johannes Lehmann. Life Cycle Assessment of Biochar Systems: Estimating the Energetic, Economic, and Climate Change Potential. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2010, 44 (2), 827–833. [CrossRef]

- John D. Adjaye; Ramesh K. Sharma; Narendra N. Bakhshi. Characterization and stability analysis of wood-derived bio-oil. Fuel Processing Technology 31 (1992) 241-256. [CrossRef]

- Carazza F; Rezende M. E. A; Pasa V. M. D; Lessa A. Fractionation of wood tar. Proc Adv Thermochem Biomass Convers 1994;2:465.

- Piyali Das; Anuradda Ganesh. Bio-oil from pyrolysis of cashew nut shell—a near fuel. Biomass and Bioenergy, Volume 25, Issue 1, July 2003, 113-117. [CrossRef]

- Xu B. J; Lu N. Experimental research on the bio oil derived from biomass pyrolysis liquefaction. Trans Chin Soc Agr Eng 1999;15:177–81.

- Boucher M. E; Chaala A; Roy C. Bio-oils obtained by vacuum pyrolysis of softwood bark as a liquid fuel for gas turbines. Part I: Properties of bio-oil and its blends with methanol and a pyrolytic aqueous phase. Biomass Bioenergy 2000;19:337–50.

- Ayşe E. Pütün; EsinApaydın; Ersan Pütün. Rice straw as a bio-oil source via pyrolysis and steam pyrolysis. Energy, Volume 29, Issues 12–15, October–December 2004, 2171-2180.

- Czernik S; Bridgwater A. V. Overview of applications of biomass fast pyrolysis oil. Energy & Fuels. 2004;18:590-598. [CrossRef]

- Mohan D; Pittman C. U. Jr; Steelee P. H. Pyrolysis of wood/biomass for bio-oil: A critical review. Energy & Fuels. 2006; 20:848-889. [CrossRef]

- Fei Yu; Shaobo Deng; Paul Chen; Yuhuan Liu; Yiquin Wan; Andrew Olson; David Kittelson; Roger Rua. Physical and Chemical Properties of Bio-Oils From Microwave Pyrolysis of Corn Stover. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 136–140 (2007) 957-970.

- Zhang Qi; Chang Jie; Wang Tiejun; Xu Ying. Review of biomass pyrolysis oil properties and upgrading research. Energy Conversion and Management 48 (2007) 87-92.

- Boateng A. A; Mullen C. A; Goldberg N; Hicks K. B. Production of bio-oil from alfalfa stems by fluidized-bed fast pyrolysis. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research. 2008;47:4115-4122. [CrossRef]

- Lu Qiang; Yang Xu-lai; ZhuXi-feng. Analysis on chemical and physical properties of bio-oil pyrolyzed from rice husk. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 82 (2008) 191-198.

- Xu Junming; Jiang Jianchun; SunYunjuan; LuYanju. Bio-Oil Upgrading by means of Ethyl Ester Production in Reactive Distillation to Remove Water to Improve Storage and Fuel Characteristics. Biomass and Bioenerg 32 (2008) 1056-1061. [CrossRef]

- W.T.Tsaia; M. K. Lee; Y. M. Chang. Fast pyrolysis of rice husk: Product yields and compositions. Bioresource Technology, Volume 98, Issue 1, January 2007, 22-28.

- M. Asadullah; M. A. Rahman; M. M. Ali; M. S. Rahman; M. A. Motin; M. B. Sultan; M. R.Alam. Production of bio-oil from fixed bed pyrolysis of bagasse. Fuel Volume 86, Issue 16, November 2007, 2514-2520. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Ji-lu. Bio-oil from fast pyrolysis of rice husk: Yields and related properties and improvement of the pyrolysis system. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 80 (2007) 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Azri Sukiran; Chow Mee Chin; Nor Kartini Abu Bakar. Bio-oils from Pyrolysis of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches. American Journal of Applied Sciences 6 (5): 869-875, 2009.

- Oasmaa A; Elliott D. C; Korhonen J. Acidity of biomass fast pyrolysis bio-oils. Energy & Fuels. 2010;24(12):6548-6554. [CrossRef]

- Michael W. Nolte; Matthew W. Liberatore. Viscosity of Biomass Pyrolysis Oils from Various Feedstocks. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 12, 6601-6608. [CrossRef]

- Seon-Jin Kim; Su-Hwa Jung; Joo-Sik Kim. Fast pyrolysis of palm kernel shells: Influence of operation parameters on the bio-oil yield and the yield of phenol and phenolic compounds. Bioresource Technology, Volume 101, Issue 23, December 2010, 9294-930. [CrossRef]

- Gaurav Kumar; Achyut K. Panda; R. K. Singh. Optimization of process for the production of bio-oil from eucalyptus wood. J Fuel Chem Technol, 2010, 38(2), 162-167. [CrossRef]

- Xiujuan Guo; Shurong Wang; Zuogang Guo; Qian Liu; Zhongyang Luo; Kefa Cen. Pyrolysis characteristics of bio-oil fractions separated by molecular distillation. Applied Energy 87 (2010) 2892-2898. [CrossRef]

- Hyeon Su Heo; Hyun Ju Park; Jong-In Dong; Sung Hoon Park; Seungdo Kim; Dong Jin Suh; Young-Woong Suh; Seung-Soo Kim; Young-Kwon Park. Fast pyrolysis of rice husk under different reaction conditions. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, Volume 16, Issue 1, 25 January 2010, 27-31.

- John V.Ortega; Andrew M. Renehan; Matthew W. Liberatore; Andrew M. Herring. Physical and chemical characteristics of aging pyrolysis oils produced from hardwood and softwood feedstocks. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, Volume 91, Issue 1, May 2011, 190-198. [CrossRef]

- Dilek Angın. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate on biochar obtained from pyrolysis of safflower seed press cake. Bioresource Technology 128 (2013) 593–597. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Pollard; M. R. Rover; R. C. Brown. Characterization of bio-oil recovered as stage fractions with unique chemical and physical properties. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 93 (2012) 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Ajay Shah; Matthew J. Darr; Dustin Dalluge; Dorde Medic; Keith Webster; Robert C. Brown. Physicochemical properties of bio-oil and biochar by fast pyrolysis of stored single-pass corn Stover and cobs. Bioresource Technology 125 (2012) 348-352. [CrossRef]

- Tahmina Imam; Sergio Capareda. Characterization of bio-oil, syn-gas and bio-char from switch grass pyrolysis at various temperatures. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 93 (2012) 170-177.

- Shuangning Xiu; Abolghasem Shahbazi. Bio-oil production and upgrading research. A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 16 (2012) 4406-4414.

- Rajeev Sharma; Pratik N. Sheth. Thermo-Chemical Conversion of Jatropha Deoiled Cake: Pyrolysis vs. Gasification. International Journal of Chemical Engineering and Applications, Vol. 6, No. 5, October 2015. [CrossRef]

- Xue-Song Zhang; Guang-Xi Yang; Hong Jiang; Wu-Jun Liu; Hong-Sheng Ding. Mass production of chemicals from biomass-derived oil by directly atmospheric distillation coupled with co-pyrolysis. Scientific Reports. 2013;3:1-7. Article Number 1120. [CrossRef]

- Jewel A. Capunitan; Sergio C. Capareda. Characterization and separation of corn stover bio-oil fractional distillation. Fuel 112 (2013) 60-73. [CrossRef]

- Yining Sun; Bin Gao; YingYao; June Fang; Ming Zhang; Yanmei Zhou; Hao Chen; Liuyan Yang. Effects of feedstock type, production method, and pyrolysis temperature on biochar and hydrochar properties. Chemical Engineering Journal 240 (2014) 574-578.

- Huijun Yang; Jingang Yao; Guanyi Chen; Wenchao Ma; BeibeiYan; YunQi. Overview of upgrading of pyrolysis oil of biomass. Energy Procedia 61 (2014) 1306-1309.

- Chaturong Paenpong; Adisak Pattiya. Effect of pyrolysis and moving-bed granular filter temperatures on the yield and properties of bio-oil from fast pyrolysis of biomass. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, Volume 119, May 2016, 40-51. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Biradar; K. A. Subramanian; M. G. Dastidar. Production and fuel upgrading of pyrolysis bio-oil Jatropha Curcas de-oiled seed cake. Fuel 119 (2014) 81-89.

- Elkasabi Y; Mullen C. A; Boateng A. A. Distillation and isolation of commodity chemicals from bio-oil made by tail-gas reactive pyrolysis. Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2014;2:2042-2052. [CrossRef]

- Rahul Garg; Neeru Anand; Dinesh Kumar. Pyrolysis of babool seeds (Acacia nilotica) in a fixed bed reactor and bio-oil characterization. Renewable Energy, Volume 96, Part A, October 2016, 167-171. [CrossRef]

- Shurong Wang; Qinjie Cai; Xiangyu Wang; Li Zhang; Yurong Wang; Zhongyang Luo. Biogasoline production from the co-cracking of the distilled fraction of bio-oil and ethanol. Energy Fuels, 2014, 28 (1), 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Sadegh Papari; Kelly Hawboldt. A review on the pyrolysis of woody biomass to bio-oil: Focus on kinetic models. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 52 (2015) 1580-1595. [CrossRef]

- Harpreet Singh; Kambo Animesh Dutta. A comparative review of biochar and hydro-char in terms of production, physico-chemical properties and applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 45(2015) 359-378.

- Shushil Kumar; Jean-Paul Lange; Guus Van Rossum; Sascha R. A. Kersten. Bio-oil fractionation by temperature-swing extraction: Principle and application. Biomass and Bioenergy 83 (2015) 96-104. [CrossRef]

- Anil Kumar Varma; Prasenjit Mondal. Pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse in semi batch reactor: Effects of process parameters on product yields and characterization of products. Industrial Crops and Products 95 (2017) 704–717. [CrossRef]

- Yaseen Elkasabi; Charles A. Mullen; Michael A. Jackson; Akwasi A. Boateng. Characterization of fast-pyrolysis bio-oil distillation residues and their potential applications. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 114 (2015) 179-186. [CrossRef]

- Kanaujia P. K; Naik D. V; Tripathi D; Singh R; Poddar M. K; Siva Kumar Konathala L. N; Sharma Y. K. Pyrolysis of Jatropha Curcas seed cake followed by optimization of liquid– liquid extraction procedure for the obtained bio-oil. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2016;118:202-224. [CrossRef]

- Tao Kan; Vladimir Strezov; Tim J. Evans. Lignocellulose biomass pyrolysis: A review of product properties and effects of pyrolysis parameters. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 57 (2016) 1126-1140. [CrossRef]

- Junmeng Cai; Scott W. Banks; Yang, Surila Darbar; Tony Bridgwater. Viscosity of Aged Bio-Oils from Fast Pyrolysis of Beech Wood and Miscanthus: Shear Rate and Temperature Dependence. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 6, 4999-5004. [CrossRef]

- Yunwu Zheng; Fei Wang; Xiaoqin Yang; Yuanbo Huang; Can Liu; Zhifeng Zheng; Jiyou Gu. Study on aromatics production via catalytic pyrolysis vapor upgrading of biomass using metal-loaded modified H-ZSM-5. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 126 (2017) 169-179. [CrossRef]

- Ann Christine Johansson; Kristiina Iisa; Linda Sandström; Haoxi Ben; Heidi Pilath; Steve Deutch; Henrik Wiinikka; Olov G. W. Öhrman. Fractional condensation of pyrolysis vapors produced from Nordic feedstocks in cyclone pyrolysis. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 123 (2017) 244-254.

- Hsiu-Po Kuo; Bo-Ren Hou; An-Ni Huang. The influence of the gas fluidization velocity on the properties of bio-oils from fluidized bed pyrolizer with in-line distillation. Applied Energy 194 (2017) 279-286. [CrossRef]

- Raquel Escrivani Guedes; Aderval S. Luna; Alexandre Rodrigues Torres. Operating parameters for bio-oil production in biomass pyrolysis: A review. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 129 (2018) 134-149. [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav Dhyani; Thallada Bhaskar. A comprehensive review on the pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Renewable Energy 129 (2018) 695-716. [CrossRef]

- Wenfei Cai; Ronghou Liu; Yifeng He; Meiyun Chai; Junmeng Cai. Bio-oil production from fast pyrolysis of rice husk in a commercial-scale plant with a downdraft circulating fluidized bed reactor. Fuel Processing Technology 171 (2018) 308-317. [CrossRef]

- Ni Huang; Chen-Pei Hsu; Bo-Ren Hou; Hsiu-Po Kuo. Production and separation of rice husk pyrolysis bio-oils from a fractional distillation column connected fluidized bed reactor. Powder Technology 323 (2018) 588-593. [CrossRef]

- Shofiur Rahman; Robert Helleur; Stephanie MacQuarrie; Sadegh Papari; Kelly Hawboldt. Upgrading and isolation of low molecular weight compounds from bark and softwood bio-oils through vacuum distillation. Separation and Purification Technology 194 (2018) 123–129. [CrossRef]

- An-Ni Huang; Chen-Pei Hsua; Bo-Ren Houa; Hsiu-Po Kuo. Production and separation of rice husk pyrolysis bio-oils from a fractional distillation column connected fluidized bed reactor. Powder Technology Volume 323, 1 January 2018, 588-593. [CrossRef]

- D. A. R. de Castroa; H. J. da Silva Ribeiro; C. C. Ferreira; L. H. H. Guerreiroa; M. de Andrade Cordeiro; A. M. Pereira; W. G. dos Santos; F. B. de Carvalho; J. O. C. Silva Jr.; R. Lopes e Oliveira; M. C. Santos; S. Duvoisin Jr; L. E. P. Borges; N. T. Machado. Fractional Distillation of Bio-Oil Produced by Pyrolysis of Açaí (Euterpe oleracea) Seeds. Editor Hassan Al-Haj Ibrahim: Fractionation, Intechopen ISBN: 978-1-78984-965-3. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Adjaye; N. N. Bakhshi. Production of hydrocarbons by catalytic upgrading of a fast pyrolysis bio-oil. Part I: Conversion over various catalysts. Fuel Processing Technology 45 (1995) 161-183. [CrossRef]

- Oasmaa A; Kuoppala E; Gust S; Solantausta Y. Fast pyrolysis of forestry residue. 1. Effect of extractives on phase separation of pyrolysis liquids. Energy & Fuels. 2003;17(1): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Guo Z.; Wang S.; Zhu Y.; Luo Z.; Cen K. Separation of acid compounds for refining biomass pyrolysis oil. Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology. 2009;7(1):49-52.

- Vispute T. P; Huber G. W. Production of hydrogen, alkanes and polyols by aqueous phase processing of wood-derived pyrolysis oils. Green Chemistry. 2009;11:1433-1445. [CrossRef]

- Song Q; Nie J; Ren M; Guo Q. Effective phase separation of biomass pyrolysis oils by adding aqueous salt solutions. Energy & Fuels. 2009;23:3307-3312. [CrossRef]

- Shurong Wang,; Yueling Gu; Qian Liu; YanYao; Zuogang Guo; Zhongyang Luo; Kefa Cen. Separation of bio-oil by molecular distillation. Fuel Processing Technology 90 (2009) 738-745.

- Guo X.; Wang S.; Guo Z.; Liu Q.; Luo Z.; Cen K. Pyrolysis characteristics of bio-oil fractions separated by molecular distillation. Applied Energy. 2010;87(9):2892-2898.

- Guo Z.; Wang S.; Gu Y.; Xu G.; Li X.; Luo Z. Separation characteristics of biomass pyrolysis oil in molecular distillation. Separation and purification. 2010;76(1):52-57.

- Zuogang Guo; Shurong Wang; Yueling Gu; Guohui Xu; Xin Li; Zhongyang Luo. Separation characteristics of biomass pyrolysis oil in molecular distillation. Separation and Purification Technology 76 (2010) 52-57. [CrossRef]

- Christensen E. D; Chupka G. M; Smurthwaite J. L. T; Alleman T. L; Lisa K; Franz J. A; Elliott D. C; Mc Cormick R. L. Analysis of oxygenated compounds in hydrotreated biomass fast pyrolysis oil distillate fractions. Energy & Fuels. 2011;25(11):5462-5471. [CrossRef]

- Ji-Lu Zheng; Qin Wei. Improving the quality of fast pyrolysis bio-oil by reduced pressure distillation. Biomass and Bioenergy 35 (2011) 1804-1810. [CrossRef]

- Arakshita Majhi; Y. K. Sharma; D. V. Naik. Blending optimization of Hempel distilled bio-oil with commercial diesel. Fuel 96 (2012) 264-269.

- Akhil Tumbalam Gooty; Dongbing Li; Franco Berruti; Cedric Briens. Kraft-lignin pyrolysis and fractional condensation of its bio-oil vapors. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 106 (2014) 33-40. [CrossRef]

- Akhil Tumbalam Gooty; Dongbing Li; Cedric Briens; Franco Berruti. Fractional condensation of bio-oil vapors produced from birch bark pyrolysis. Separation and Purification Technology 124 (2014) 81-88. [CrossRef]

- Yaseen Elkasabi; Akwasi A. Boateng; Michael A. Jackson. Upgrading of bio-oil distillation bottoms into biorenewable calcined coke. Biomass and Bioenergy 81 (2015) 415-423. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Costa; C. C. Ferreira; A. L. B. dos Santos; H. da Silva Vargens; E. G. O. Menezes; V. M. B. Cunha; M. P. da Silva; A. A. Mâncio; N. T. Machado; M. E. Araújo. Process simulation of organic liquid products fractionation in countercurrent multistage columns using CO2 as solvent with Aspen-Hysys. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids Volume 140, October 2018, 101-115. [CrossRef]

- Standards T. Acid-Insoluble Lignin in Wood and Pulp. Tappi Method T 222 Om-06. Atlanta, GA: Tappi Press. 2006.

- Buffiere P; Loisel D. Dosage des fibres Van Soest. Weened, Laboratoire de Biotechnologie de l’Environnement. INRA Narbonne. 2007:1-14.

- da Mota S. A. P; Mâncio A. A; Lhamas D. E. L; de Abreu D. H; da Silva M. S; dos Santos W. G; de Castro D. A. R; de Oliveira R. M; Araújo M. E; Borges L. E. P; Machado N. T. Production of green diesel by thermal catalytic cracking of crude palm oil (Elaeis guineensis Jacq) in a pilot plant. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 2014;110:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira C. C; Costa E. C; de Castro D. A. R; Pereira M. S; Mâncio A. A; Santos M. C; Lhamas D. E. L; da Mota S. A. P; Leão A. C; Duvoisin S. Jr; Araújo M. E; Borges L. E. P; Machado N. T. Deacidification of organic liquid products by fractional distillation in laboratory and pilot scales. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 2017;127:468-489. [CrossRef]

- Seshadri K. S; Cronauer D. C. Characterization of coal-derived liquids by 13C N.M.R. and FT-IR Spectroscopy. Fuel. 1983;62:1436-1444.

- Haiping Yang; Rong Yan; Hanping Chen; Dong Ho Lee; Chuguang Zheng. Characteristics of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin pyrolysis. Fuel 86 (2007) 1781-1788.

- Jamshed Akbar; Mohammad S. Iqbal; Shazma Massey; Rashid Masih. Kinetics and mechanism of thermal degradation of pentose- and hexose-based carbohydrate polymers. Carbohydrate Polymers 90 (2012) 1386–1393. [CrossRef]

- Xinwei Yu; Hongbing Ji; Shengzhou Chen; Xiaoguo Liu; Qingzhu Zeng. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Glucose-Based and Fructose-Based Carbohydrates. Advanced Materials Research, Vols. 805-806, 265-268, 2013.

- Sathish K. Tanneru; Divya R. Parapati; Philip H. Steele. Pretreatment of bio-oil followed by upgrading via esterification to boiler fuel. Energy 73 (2014) 214-220. [CrossRef]

- Abnisa F.; Arami-Niya A.; W. M. A. Wan Daud; J. N. Sahu. Characterization of bio-oil and bio-char from pyrolysis of palm oil wastes. Bioenergy Res 2013;6:830–40. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez M.; Chaala A.; Roy C. Vacuum pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse. J Anal Appl Pyrol 2002;65(2):111–36. [CrossRef]

- Tuya Ba. Abdelkader Chaala; Manuel Garcia-Perez; Denis Rodrigue; Christian Roy. Colloidal properties of bio-oils obtained by vacuum pyrolysis of softwood bark. Characterization of water-soluble and water-insoluble fractions. Energy Fuels 2004;18:704–12. [CrossRef]

| Physicochemical Analysis | Cordeiro [12]Wet Basis |

Tamiris et. al. [13]Dry Basis | Kabacknik & Roger [14]Wet Basis |

Altman [15]Wet Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture [%] | 10.15 | 0.79 | 58.30 | 13.60 |

| Lipids [%] | 0.61 | 1.89 | 1.65 | 3.48 |

| Proteins [%] | 6.25 | 7.85 | 5.56 | 5.02 |

| Fibers [%] | 29.79 | 2.1 | 21.29 | 62.95 |

| Hemicelluloses [%] | 5.5 | ─ | ─ | 14.19 |

| Cellulose [%] | 40.29 | ─ | ─ | 39.83 |

| Lignin[%] | 4.00 | ─ | ─ | 8.93 |

| Volatile Matter [%] | 0.5 | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Fixed Carbon [%] | 0.83 | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Ash [%] | 0.15 | 1.68 | 5.97 | 1.55 |

| Nitrogen | ─ | 1.26 | ─ | ─ |

| Carbohydrate | ─ | 85.69 | ─ | ─ |

| Process Parameters | Temperature [°C] |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 450 | 400 | 350 | |

| Mass of Açaí (kg) | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Mass of GLP (kg) | 14.3 | 10.2 | 5.8 |

| Cracking Time (min) | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Time to reach Cracking Temperature (min) | 120 | 110.5 | 100 |

| Burning Time of the Gas Produted (min) | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Initial Cracking Temperature (°C) | 179 | 160 | 167 |

| Mas of Aqueous Phase (OLP + H2O) (kg) | 10.133 | 9.825 | 8.573 |

| Mass of Coke (kg) | 10.700 | 12.500 | 15.800 |

| Mass of OLP (kg) | 1.316 | 1.146 | 0.599 |

| Mass of H2O (kg) | 8.816 | 8.678 | 7.973 |

| Mass of Gas (kg) | 9.167 | 7.675 | 5.627 |

| Yield of OLP (kg) | 4.39 | 3.82 | 2.00 |

| Yield of Coke (%) | 35.67 | 41.67 | 52.67 |

| Yield of H2O (%) | 29.39 | 28.93 | 26.58 |

| Yield of Gas (%) | 30.56 | 25.58 | 18.76 |

| Physicochemical Properties |

450 ºC | 400 ºC | 350 ºC | [25] | [29] | [32] | [45] | ]73] | [86] | [87] | ANP Nº 65 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | Bio-Oil | ||

| ρ [g/cm3], 30°C | 1.043 | 1.0330 | 1.0236 | 1.066 | 1.250 | 1.140 | 1.190 | 1.1581 | 1.200 | 1.030 | 0.82-0.85 |

| I. A [mg KOH/g] | 70.26 | 75.76 | 92.87 | - | - | - | - | - | - | . | |

| I. R [-] | ND | ND | ND | - | - | - | - | - | - | . | |

| ν [mm²/s], 40°C, *60°C | 68.34 | 61.85 | 57.22 | 38.0 | 148.0 | 13.2 | 40.0* | 5.0-13.0 | 12.0 | . | 2.0-4.5 |

| Distillation: Vigreux Column of 03 Stages |

OLP [g] |

Gas [g] | Raffinate [g] |

Distillates [g] | Yield [wt.%] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | G | K | LD | HD | H2O | G | K | LD | HD | ||||

| 450 ºC | 136.84 | 0 | 40.98 | 20.26 | 6.43 | 38.60 | 30.59 | 0 | 14.80 | 4.70 | 28.21 | 22.35 | 0 |

| Physical-chemistry Properties | 450 ° C | ANP Nº 65 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gasoline | Kerosene | Light Diesel | ||

| ρ [g/cm3] | SNA | 0.9816 | 0.9191 | 0.82-0.85 |

| I. A [mg KOH/g] | 19.94 | 61.08 | 64.78 | |

| I. R[-] | 1.455 | 1.497 | 1.479 | |

| μ [cSt] | SNA | 4.29 | 9.05 | 2.0-4.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).