Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

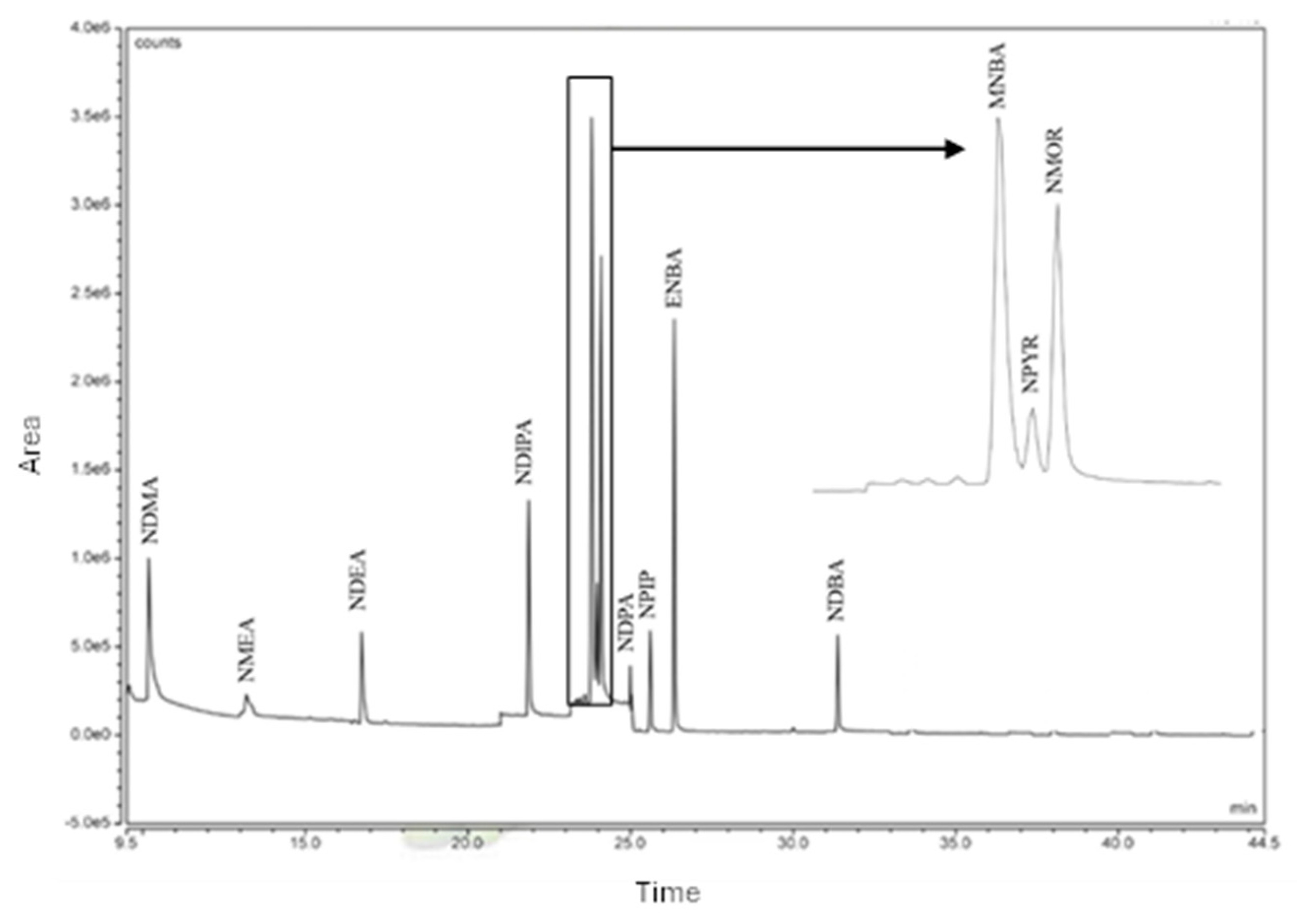

2.1. Chromatographic Run

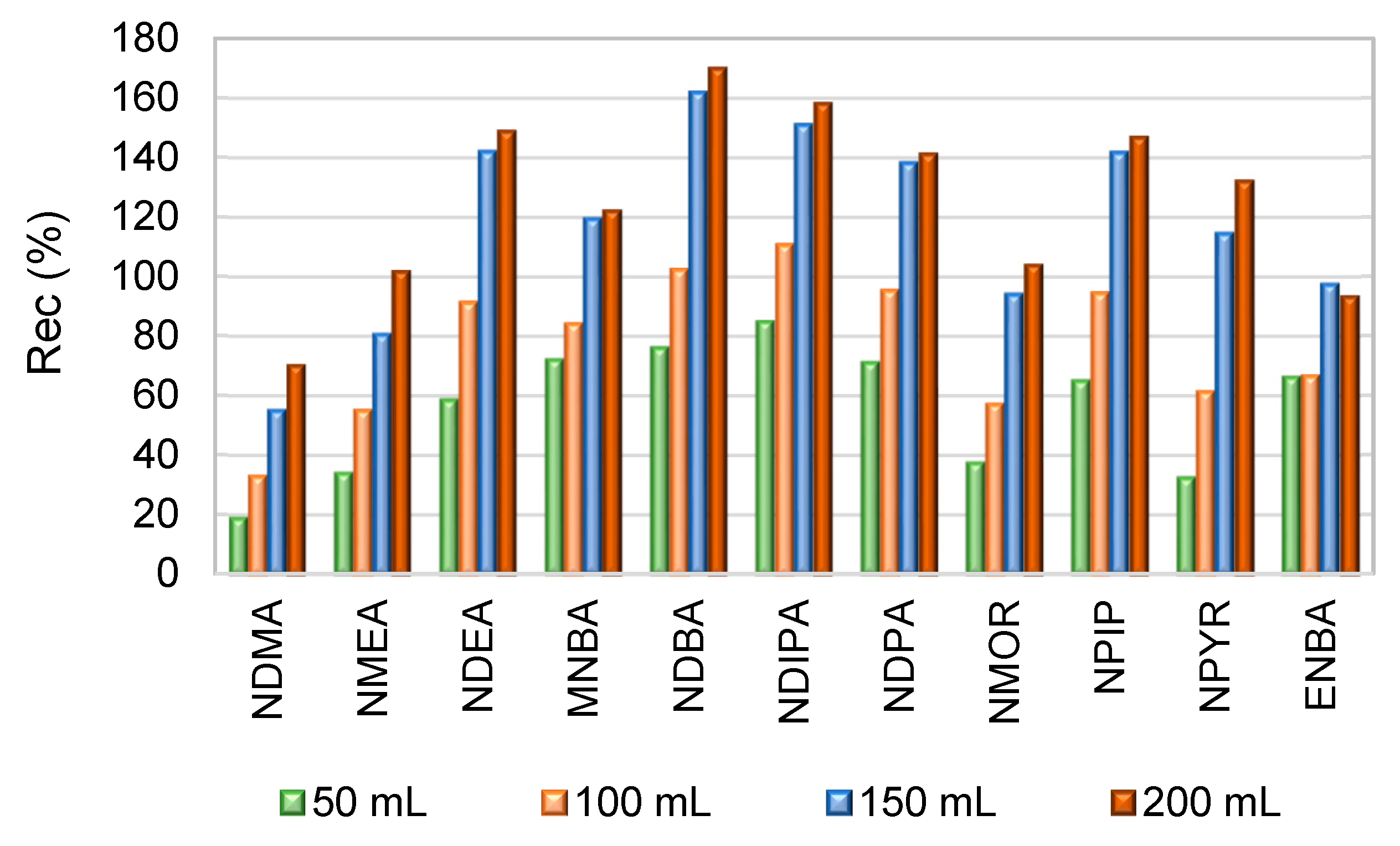

2.2. LLE Procedure

2.3. Linear/Working Range

2.4. Precision

2.5. Recovery and Method Quantification Limit

2.6. Nitrosamines in Drinking Water

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

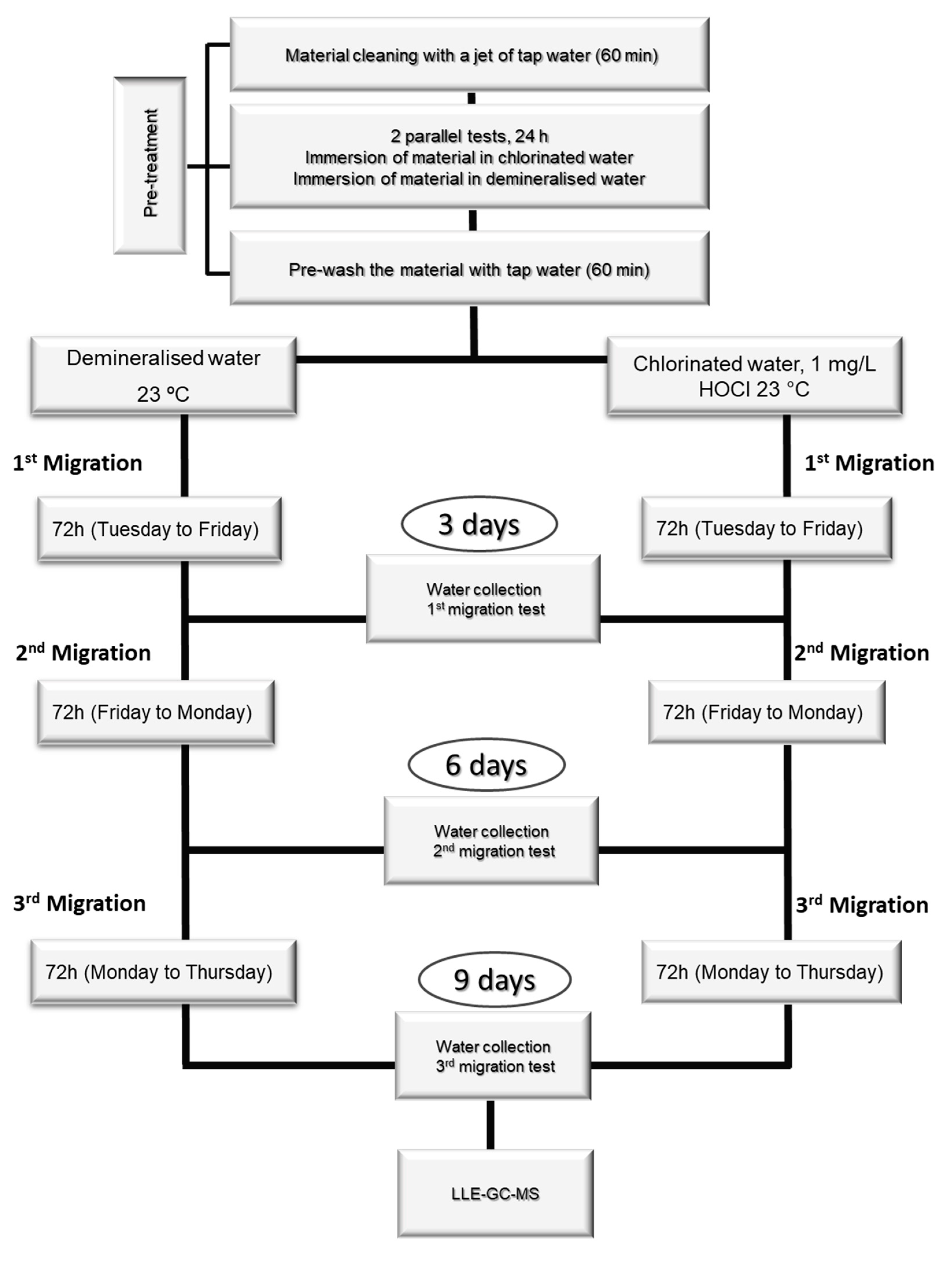

3.2. Sample Selection

3.3. Liquid-Liquid Extraction

3.4. GC-MS Analysis

3.5. Quality Assurance and In-House Validation Studies

3.6. Migration Assays

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directive (UE) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Official Journal of the European Union L435/1. 2020:1–62.

- Benoliel MJ (2013) Influência de produtos químicos e de materiais na qualidade da água de consumo humano. Associação Portuguesa dos Recursos Hídricos (APRH),1–12 https://www.aprh.pt/congressoagua98/files/com/133.pdf.

- Chaves Simões L, Simões M (2013) Biofilms in drinking water: Problems and solutions. RSC Adv 3:2520–2533. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez S, Lopez-Roldan R, Cortina JL (2013) Presence of metals in drinking water distribution networks due to pipe material leaching: A review. Toxicol Environ Chem 95:870–889. [CrossRef]

- Naismith I, Jönssen J, Pitchers, Rocket L et al (2017) Draft Final Report: Support to the implementation and further development of the Drinking Water Directive (98/83/EC): Study on materials in contact with drinking water, Umweltbundesamt GmbH in cooperation with subcontractor WRc. Available at: https://www.ecocae.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Study-on-materials-in-contact-with-drinking-water.pdf.

- Tomboulian P, Schweitzer L, Mullin K, et al (2004) Materials used in drinking water distribution systems: Contribution to taste-and-odor. Water Science and Technology 49:219–226. [CrossRef]

- Fawell J, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ (2003) Contaminants in drinking water. Br Med Bull 68:199–208. [CrossRef]

- Iram M (2019) From Valsartan to Ranitidine: The Story of Nitrosamines So Far. Indian Journal of Pharmacy Practice 13:01–02. [CrossRef]

- Vrzal T, Olsovská J (2016) N-nitrosamines in 21th Century. Kvasny Prumysl 62:2–8. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alba A and Agüera A (2005) Nitrosamines. In book: Encyclopedia of Analytical Science. 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Low H (1974) Nitroso compounds: Safety and public health. Arch Environ Health 29:256–260. [CrossRef]

- Crosby NT, Sawyer R (1976) N-Nitrosamines: A review of chemical and biological properties and their estimation in foodstuffs. Adv Food Res 22:1–71. [CrossRef]

- Hayes JE (2010) Sensory descriptors for cooked meat products. In Book: Sensory Analysis of Foods of Animal Origin, Edited ByLeo M.L. Nollet, Fidel Toldra, Chapter 10, 26 pages, CRC Press, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/b10822-12/sensory-descriptors-cooked-meat-products-jenny-hayes?context=ubx&refId=9cf8333d-c685-4439-9a1f-fbe9f3327439.

- Deblonde T, Cossu-Leguille C, Hartemann P, et al (2022) Nitrosamines. Water Res 47:1–62. [CrossRef]

- Xia J, Chen Y, Huang H, et al (2023) Occurrence and mass loads of N-nitrosamines discharged from different anthropogenic activities in Desheng River, South China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30:57975–57988. [CrossRef]

- Crews C (2014) Processing Contaminants: N-Nitrosamines. Encyclopedia of Food Safety 2:409–415. [CrossRef]

- IARC (2022) Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–135, https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/.

- Ripollés C, Pitarch E, Sancho J V., et al (2011) Determination of eight nitrosamines in water at the ngL-1 levels by liquid chromatography coupled to atmospheric pressure chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta 702:62–71. [CrossRef]

- Yoon S, Nakada N, Tanaka H (2012) A new method for quantifying N-nitrosamines in wastewater samples by gas chromatography - Triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Talanta 97:256–261. [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Wu M, Wang W, et al (2015) Determination of 14 nitrosamines at nanogram per liter levels in drinking water. Anal Chem 87:1330–1336. [CrossRef]

- Sieira BJ, Carpinteiro I, Rodil R, et al (2020) Determination of N-nitrosamines by gas chromatography coupled to quadrupole–time-of-flight mass spectrometry in water samples. Separations 7:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki J, Andrzejewski P (2011) Nitrosamines and water. J Hazard Mater 189:1–18. [CrossRef]

- US EPA (2016) Six-Year Review 3 Technical Support Document for Nitrosamines. United states environmental protection agency.

- World Health Organization (WHO). N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 3rd ed. including 1st and 2nd addenda, 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/chemicals/ndmasummary_2ndadd.pdf.

- Crews C (2010) The determination of N- nitrosamines in food. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops and Foods 2:2–12. [CrossRef]

- Sen NP, Seaman S, Tessier L (1982) Comparison of Two Analytical Methods for the Determination of Dimethylnitrosamine in Beer and Ale, and Some Recent Results. J Food Saf 4:243–250. [CrossRef]

- Scheeren MB, Sabik H, Gariépy C, et al (2015) Determination of N-nitrosamines in processed meats by liquid extraction combined with gas chromatography-methanol chemical ionisation/mass spectrometry. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 32:1436–1447. [CrossRef]

- Aragón M, Marcé RM, Borrull F (2013) Determination of N-nitrosamines and nicotine in air particulate matter samples by pressurised liquid extraction and gas chromatography-ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 115:896–901. [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko S, Mölder U (2006) Volatile N-nitrosamines in various fish products. Food Chem 96:325–333. [CrossRef]

- Bian Y, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, et al (2021) Progress in the pretreatment and analysis of N-nitrosamines: an update since 2010. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 61:3626–3660. [CrossRef]

- Llop A, Borrull F, Pocurull E (2012) Pressurised hot water extraction followed by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of N-nitrosamines in sewage sludge. Talanta 88:284–289. [CrossRef]

- Fekete A, Malik AK, Kumar A, Schmitt-Kopplin P (2010) Amines in the environment. Crit Rev Anal Chem 40:102–121. [CrossRef]

- Cantwell FF, Losier M (2002) Liquid-liquid extraction. Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry 37:297–340. [CrossRef]

- Ma M, Cantwell FF (1999) Solvent microextraction with simultaneous back-extraction for sample cleanup and preconcentration: quantitative extraction. Anal Chem 71:388–393. [CrossRef]

- Thornton JD (2011) Extraction, Liquid-Liquid. A-to-Z Guide to Thermodynamics, Heat and Mass Transfer, and Fluids Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Ren S, Zhang H, et al (2011) Occurrence of nine nitrosamines and secondary amines in source water and drinking water: Potential of secondary amines as nitrosamine precursors. Water Res 45:4930–4938. [CrossRef]

- Rudneva II, Omel’chenko SO (2021) Nitrosamines in Aquatic Ecosystems: Sources, Formation, Toxicity, Environmental Risk (Review). 2. Content In Aquatic Biota, Biological Effects and Risk Assessment. Water Resources 48:291–299. [CrossRef]

- Planas C, Palacios Ó, Ventura F, et al (2008) Analysis of nitrosamines in water by automated SPE and isotope dilution GC/HRMS. Occurrence in the different steps of a drinking water treatment plant, and in chlorinated samples from a reservoir and a sewage treatment plant effluent. Talanta 76:906–913. [CrossRef]

- Heim TH, Dietrich AM (2007) Sensory aspects and water quality impacts of chlorinated and chloraminated drinking water in contact with HDPE and cPVC pipe. Water Res 41:757–764. [CrossRef]

- EN 12873-1: 2003. Influence of materials on water intended for human consumption- Influence due to migration - Part 1: Test method for factory-made products made from or incorporating organic or glassy (porcelain/vitreous enamel) materials.

- EN 12873-2: 2005. Influence of materials on water intended for human consumption- Influence due to migration- Part 2: Test method for non-metallic and noncementitious site-applied materials.

- Decreto - Lei no 69/2023 de 21 de agosto. Diário da República - I Série-B 5–13.

- JMC (2020) 4MSI Joint Management Committee, Common Approach on Organic Materials in Contact with Drinking Water. 1–26. Available at: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/5620/dokumente/common_approach_on_organic_materials_-_part_a_methodologies_for_testing_and_accepting_starting_substances_0.pdf.

- Almeida CMM (2021) Overview of sample preparation and chromatographic methods to analysis pharmaceutical active compounds in waters matrices. Separations 8:1–50. [CrossRef]

- ISO 8466-1:2021 Water quality — Calibration and evaluation of analytical methods — Part 1: Linear calibration function.

- Munch JW, Bassett MV (2004) Method 521: Determination of nitrosamines in drinking water by solid-phase extraction and capillary column gas chromatography with large volume injection and chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_report.cfm?Lab=NERL&dirEntryId=103912.

- De Caroli Vizioli B, Wang Hantao L, Carolina Montagner C (2021) Drinking water nitrosamines in a large metropolitan region in Brazil. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28:32823–32830. [CrossRef]

| NAs | N | Linear range (µg/L) |

r2 | CVm (%) | Mandel Test VT ≤ F(0.05;1;N-3) |

Calibration curve | Repeatability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOD (µg/L) |

LOQ (µg/L) |

LOD (µg/L) |

LOQ (µg/L) |

||||||

| NDMA | 8 | 24 - 109 | 0.9999 | 0.39 | 0.064 < 6.61 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.09 | 0.30 |

| NMEA | 9 | 30 - 180 | 0.9998 | 0.90 | 0.218 < 5.99 | 2.3 | 7.6 | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| NDEA | 9 | 60 - 359 | 0.9997 | 1.12 | 0.835 < 5.99 | 5.6 | 18.8 | 0.07 | 0.22 |

| NDIPA | 9 | 35 - 208 | 0.9995 | 1.43 | 0.098 < 5.99 | 4.2 | 13.9 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| MNBA | 9 | 16 - 96 | 0.9998 | 0.91 | 1.43 < 5.99 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| NPYR | 6 | 65 - 193 | 0.9992 | 1.34 | 7.17 < 10.13 | 4.9 | 16.2 | 0.08 | 0.26 |

| NMOR | 6 | 45 - 157 | 0.9994 | 1.34 | 5.78 < 10.13 | 3.8 | 12.7 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| NDPA | 6 | 24 - 72 | 0.9986 | 1.74 | 4.82 < 10.13 | 2.4 | 7.8 | 0.06 | 0.21 |

| NPIP | 9 | 50 - 300 | 0.9989 | 2.12 | 3.29 < 5.99 | 8.9 | 29.8 | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| ENBA | 8 | 10 - 45 | 0.9997 | 0.94 | 2.58 < 6.61 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.16 | 0.53 |

| NDBA | 7 | 60 - 208 | 0.9992 | 1.38 | 4.38 < 7.71 | 5.2 | 17.3 | 0.11 | 0.35 |

| NAs | Lower concentration | Higher concentration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (µg/L) | RSD (%) | C (µg/L) | RSD (%) | |

| NDMA | 24.2 | 3.0 | 145 | 2.3 |

| NMEA | 30.0 | 2.7 | 180 | 0.80 |

| NDEA | 59.8 | 2.2 | 269.3 | 6.4 |

| NDIPA | 34.7 | 1.1 | 208.4 | 3.0 |

| MNBA | 16.0 | 2.7 | 96.0 | 4.3 |

| NPYR | 64.5 | 2.6 | 193.4 | 11 |

| NMOR | 44.7 | 1.9 | 201.2 | 5.3 |

| NDPA | 24.0 | 2.1 | 72.1 | 11 |

| NPIP | 50.0 | 2.9 | 225.1 | 6.2 |

| ENBA | 10.0 | 5.3 | 59.9 | 3.3 |

| NDBA | 59.5 | 3.5 | 208.2 | 4.8 |

| NAs | Lower concentration | Higher concentration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (µg/L) | RSD (%) | C (µg/L) | RSD (%) | |

| NDMA | 24.2 | 3.0 | 145 | 2.3 |

| NMEA | 30.0 | 2.7 | 180 | 0.80 |

| NDEA | 59.8 | 2.2 | 269.3 | 6.4 |

| NDIPA | 34.7 | 1.1 | 208.4 | 3.0 |

| MNBA | 16.0 | 2.7 | 96.0 | 4.3 |

| NPYR | 64.5 | 2.6 | 193.4 | 11 |

| NMOR | 44.7 | 1.9 | 201.2 | 5.3 |

| NDPA | 24.0 | 2.1 | 72.1 | 11 |

| NPIP | 50.0 | 2.9 | 225.1 | 6.2 |

| ENBA | 10.0 | 5.3 | 59.9 | 3.3 |

| NDBA | 59.5 | 3.5 | 208.2 | 4.8 |

| NAs | C (µg/L) | Ultrapure Water (n=10) |

Drinking Water (n=29) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rec (%) | RSD (%) | Rec (%) | RSD (%) | ||

| NDMA | 48.3 | 57 | 7.9 | 47 | 18.3 |

| NMEA | 60.0 | 59 | 7.7 | 62 | 9.4 |

| NDEA | 119.7 | 106 | 14.5 | 112 | 14.2 |

| NDIPA | 69.5 | 103 | 12.9 | 115 | 14.5 |

| MNBA | 32.0 | 94 | 7.8 | 108 | 18.7 |

| NPYR | 128.9 | 93 | 17.0 | 101 | 13.5 |

| NMOR | 89.4 | 83 | 12.5 | 83 | 12.8 |

| NDPA | 48.0 | 97 | 15.0 | 104 | 14.1 |

| NPIP | 100.0 | 103 | 13.4 | 115 | 13.9 |

| ENBA | 20.0 | 82 | 13.0 | 89 | 19.2 |

| NDBA | 119.0 | 103 | 13.4 | 125 | 11.6 |

| NAs | LOQ (µg/L) | MQL (µg/L) | MCTTap (µg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDMA | 0.0060 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| NMEA | 0.0092 | ||

| NDEA | 0.033 | ||

| NDIPA | 0.0089 | ||

| MNBA | 0.0083 | ||

| NPYR | 0.033 | ||

| NMOR | 0.019 | ||

| NDPA | 0.012 | ||

| NPIP | 0.028 | ||

| ENBA | 0.0045 | ||

| NDBA | 0.038 |

| Material | Surface area (dm2) |

N | Volume (dm2) |

S/V ratio (dm-1) |

Fc (dia.dm-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 18.35 | 4 | 4 | 4.6 | 1 |

| B | 22.25 | 4 | 4 | 5.6 | 1 |

| C | 19.20 | 4 | 4 | 4.8 | 0.01 |

| D | 6.41 | 4 | 5 | 5.1 | 1 |

| Material | NAs | (µg/L) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Migration | 2nd Migration | 3rd Migration | |||||

| CW | DW | CW | DW | CW | DW | ||

| C | MNBA | 106 | 97 | 79 | 47 | 50 | 23 |

| NMOR | < LOQ | 57 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | |

| NDPA | 76 | 30 | 51 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | |

| ENBA | 267 | 99 | 142 | 73 | 58 | 39 | |

| D | MNBA | < LOQ | 21 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | 16 |

| NDBA | < LOQ | < LOQ | 65 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | |

| Material | NAs | Taxa de Migração (µg dm-2d-1) | CTap | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Migration | 2nd Migration | 3rd Migration | |||||||

| CW | DW | CW | DW | CW | DW | CW | DW | ||

| C | MNBA | 7.1 | 6.5 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 0.030 | 0.010 |

| NMOR | < LOQ | 3.9 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | --- | --- | |

| NDPA | 5.3 | 1.9 | 3.3 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | --- | --- | |

| ENBA | 18.6 | 6.9 | 9.9 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 0.040 | 0.030 | |

| D | MNBA | 1.4 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | --- | --- |

| NDBA | < LOQ | < LOQ | 4.2 | < LOQ | < LOQ | < LOQ | --- | --- | |

| Parameter | Material | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| Length (mm) | 150 | 158 | 150 | 209 |

| Width (mm) | 147 | 158 | 150 | 147 |

| Height/Thickness (mm) | 3 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| Colour | Grey | White | Black | Beige |

| Opacity | Opaque | Glossy | Opaque | Glossy |

| Suggested use | Waterproof coating for waterworks, roofs, and bridge decks | Impermeable coating for drinking water tanks | High-strength sealant for applications in sewers and drinking water tanks | Biocomponent for the production of 100 %polyurea coatings |

| Nitrosamine | Retention time (min) | Time window (min) | Quantitation ion (m/z) | Confirmation ion (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDMA | 10.13 | 9.5 – 12.99 | 42 | 74 |

| NMEA | 13.61 | 13 – 16.39 | 42 | 88 |

| NDEA | 16.70 | 16.40 – 20.99 | 42 | 102 |

| NDIPA | 21.88 | 21 – 23.14 | 43 | 70 |

| MNBA | 23.85 | 23.15 – 24.99 | 77 | 106 |

| NPYR | 23.90 | 41 | 100 | |

| NMOR | 24.01 | 56 | 86 | |

| NDPA | 24.14 | 43 | 70 | |

| NPIP | 25.66 | 25 – 30.99 | 55 | 114 |

| ENBA | 26.39 | 106 | 121 | |

| NDBA | 31.47 | 31 – 32.99 | 57 | 84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).