Submitted:

26 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

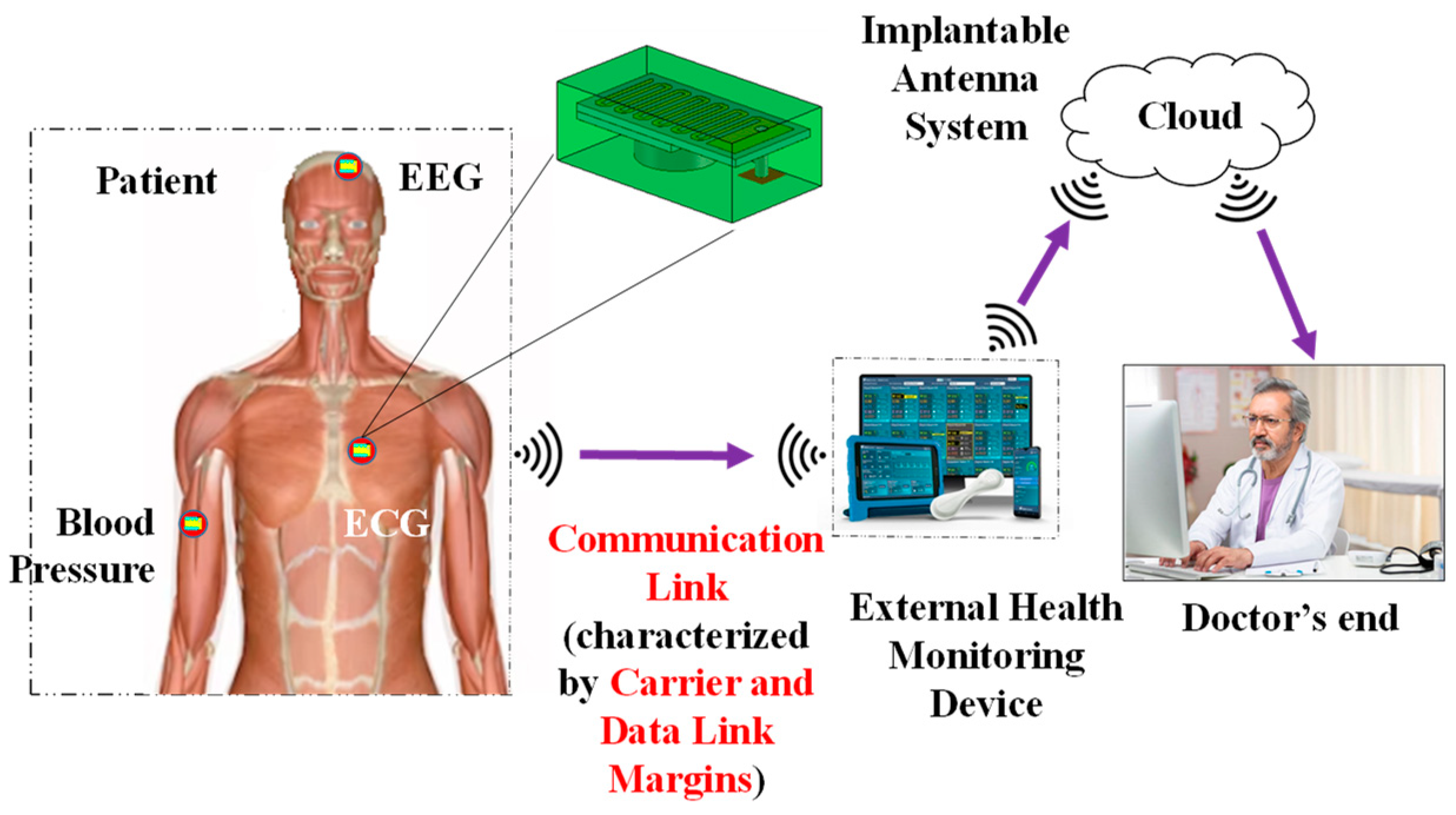

1. Introduction

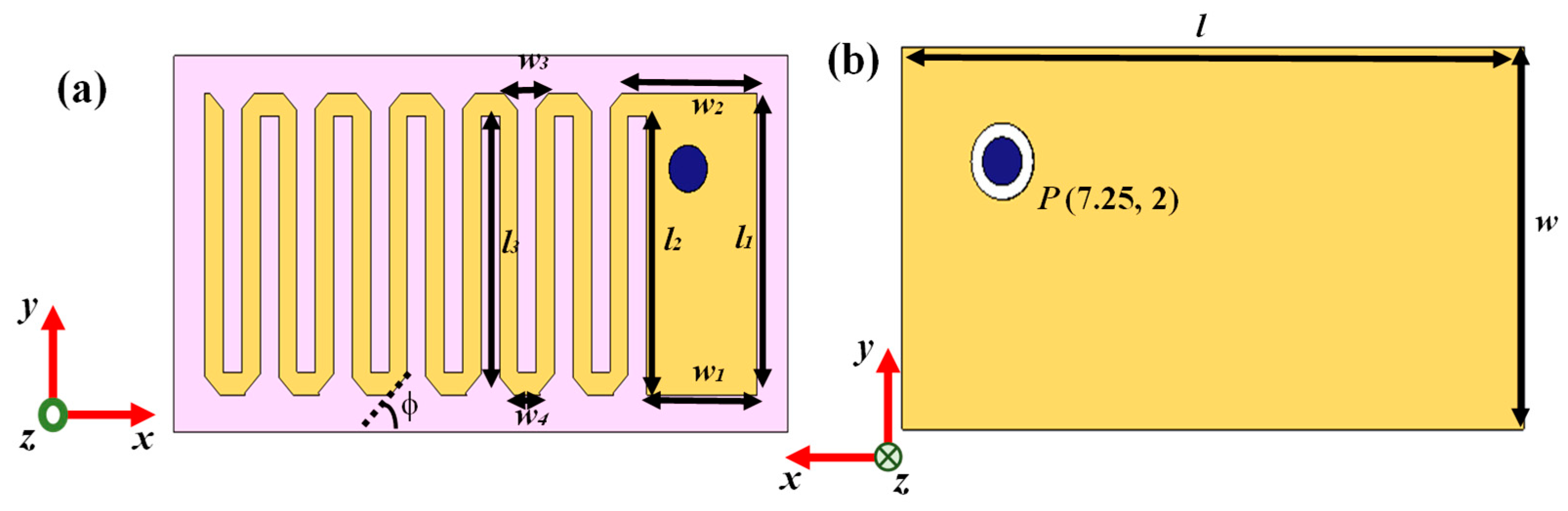

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| l | 20 mm | w2 | 4.397 mm |

| w | 10 mm | w3 | 1.46 mm |

| l1 | 8 mm | w4 | 0.86 mm |

| w1 | 3.6 mm | φ | 45o |

| l2 | 7.4 mm | P | (7.25 mm, 2 mm) |

2. Models and Methods

2.1. Implantable Transmitting Antenna System Design

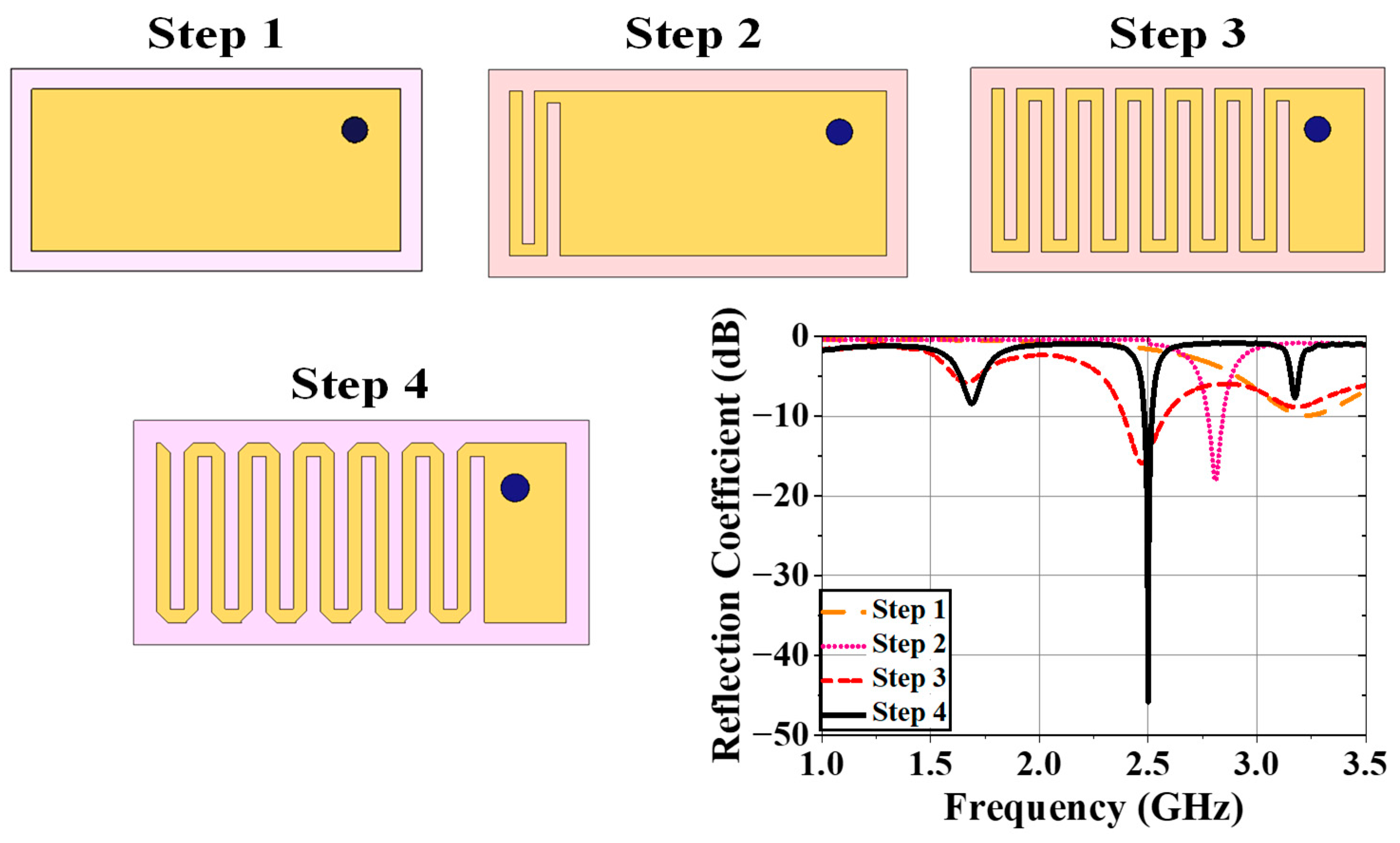

2.1.1. Design Procedure

2.1.2. Simulation Setup

2.1.3. Design Evolution

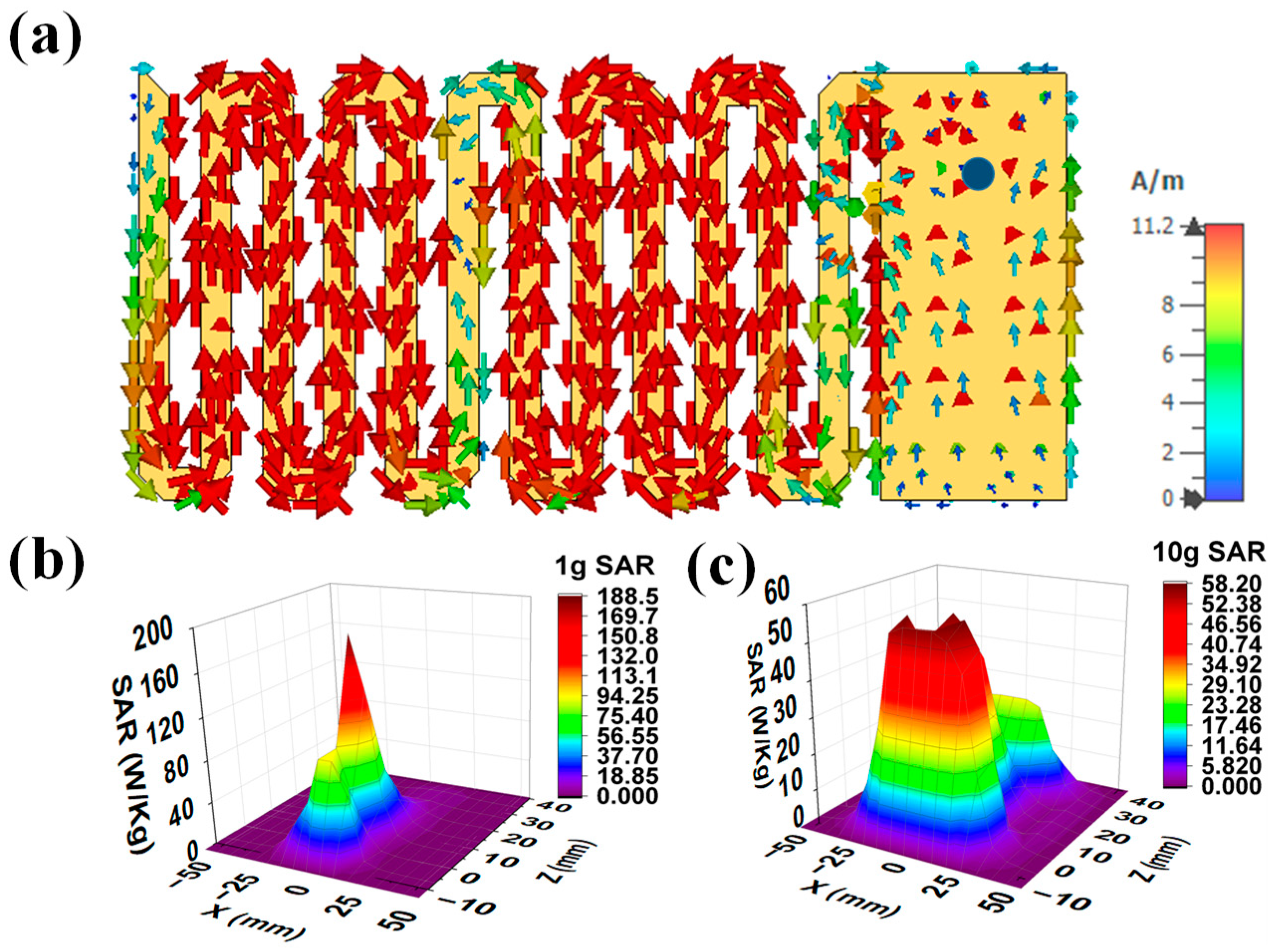

2.1.4. Current Distribution and SAR profile

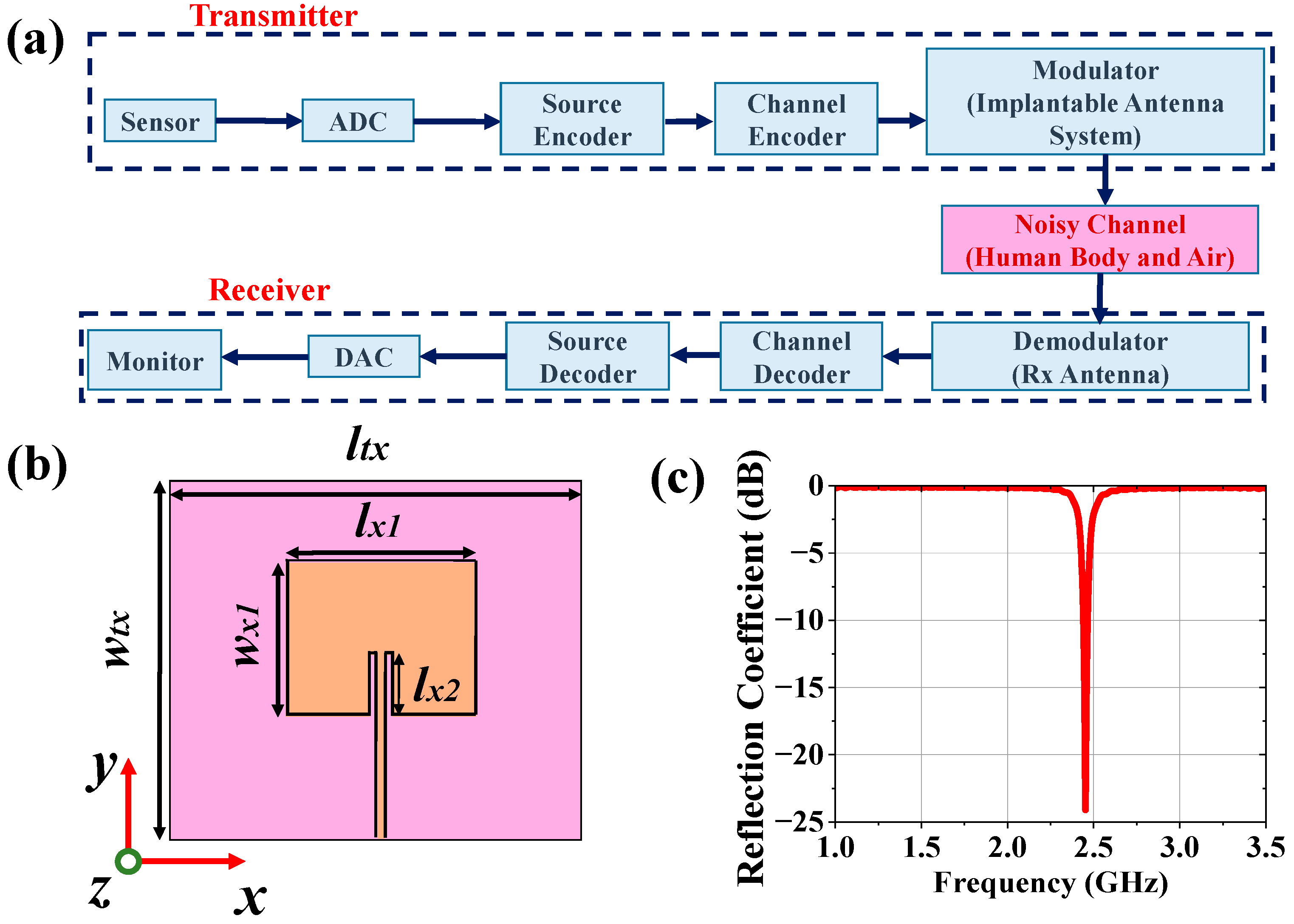

2.2. Antenna Design for Monitoring Device

2.3. Communication Performance Characterization

2.4. Carrier-Link-Margin and Data-Link-Margin Calculation

| Parameters | Variable | Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmitter | Frequency | fr | 2.47 GHz |

| Transmitted Power | PTX | 8.45 dBm | |

| Tx Antenna gain | GTX | -38.42 dBi | |

| Receiver | Receiving Antenna gain | GRX | 4.95 dBi |

| Polarization | P | LP | |

| Temperature | To | 293 K | |

| Boltzmann Constant | K | 1.38Χ10-23 | |

| Noise Power Density | No | 199.95 dB/Hz | |

| Signal Quality | Distance | d | 1-15m |

| Ideal-BPSK | Eb/No | 9.6 dB | |

| Coding gain | GC | 0 | |

| Fixing deterioration | GD | 2.5 dB |

3. Dependence Analysis and Discussion

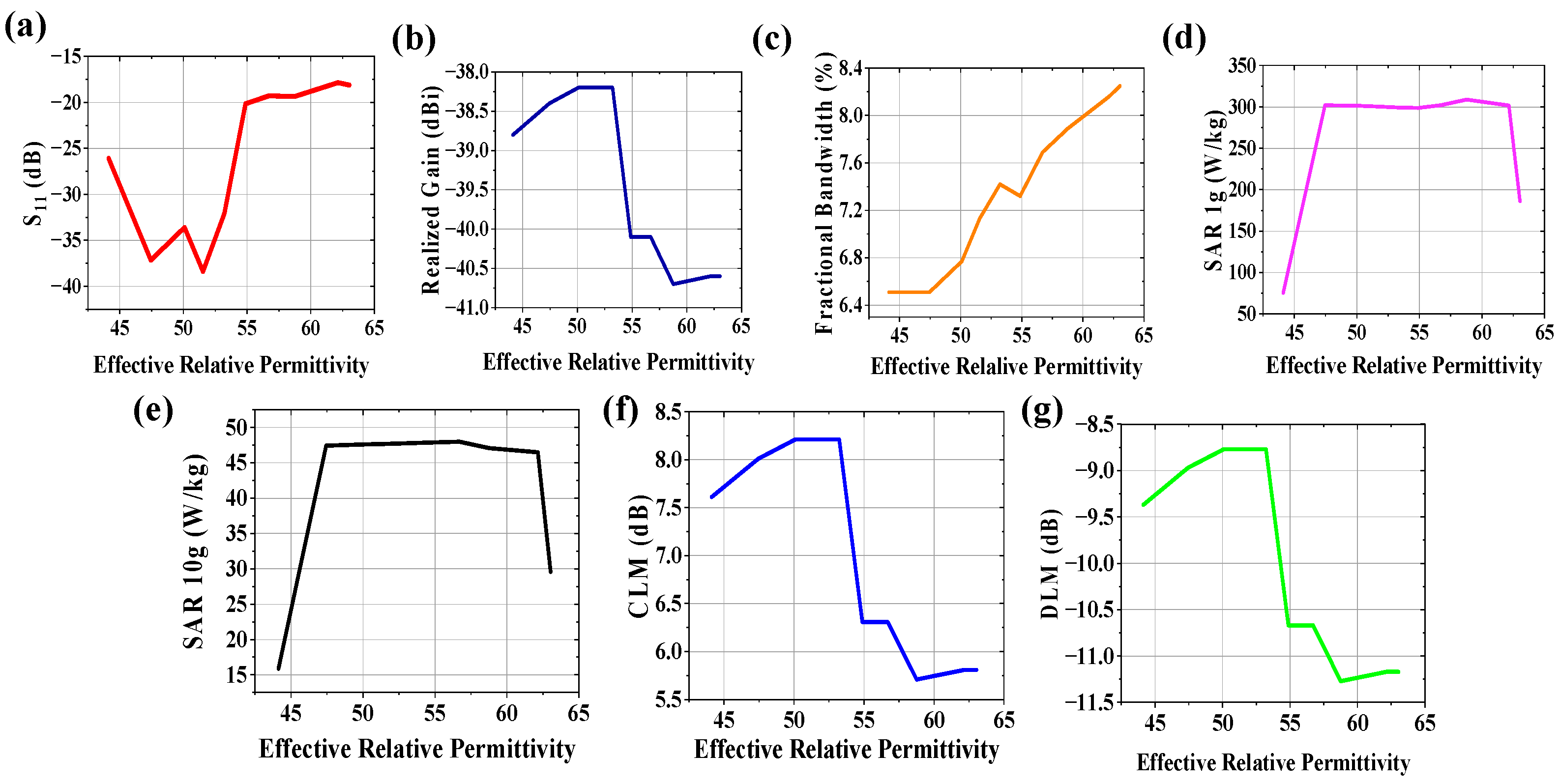

3.1. Variation of Effective Relative Permittivity

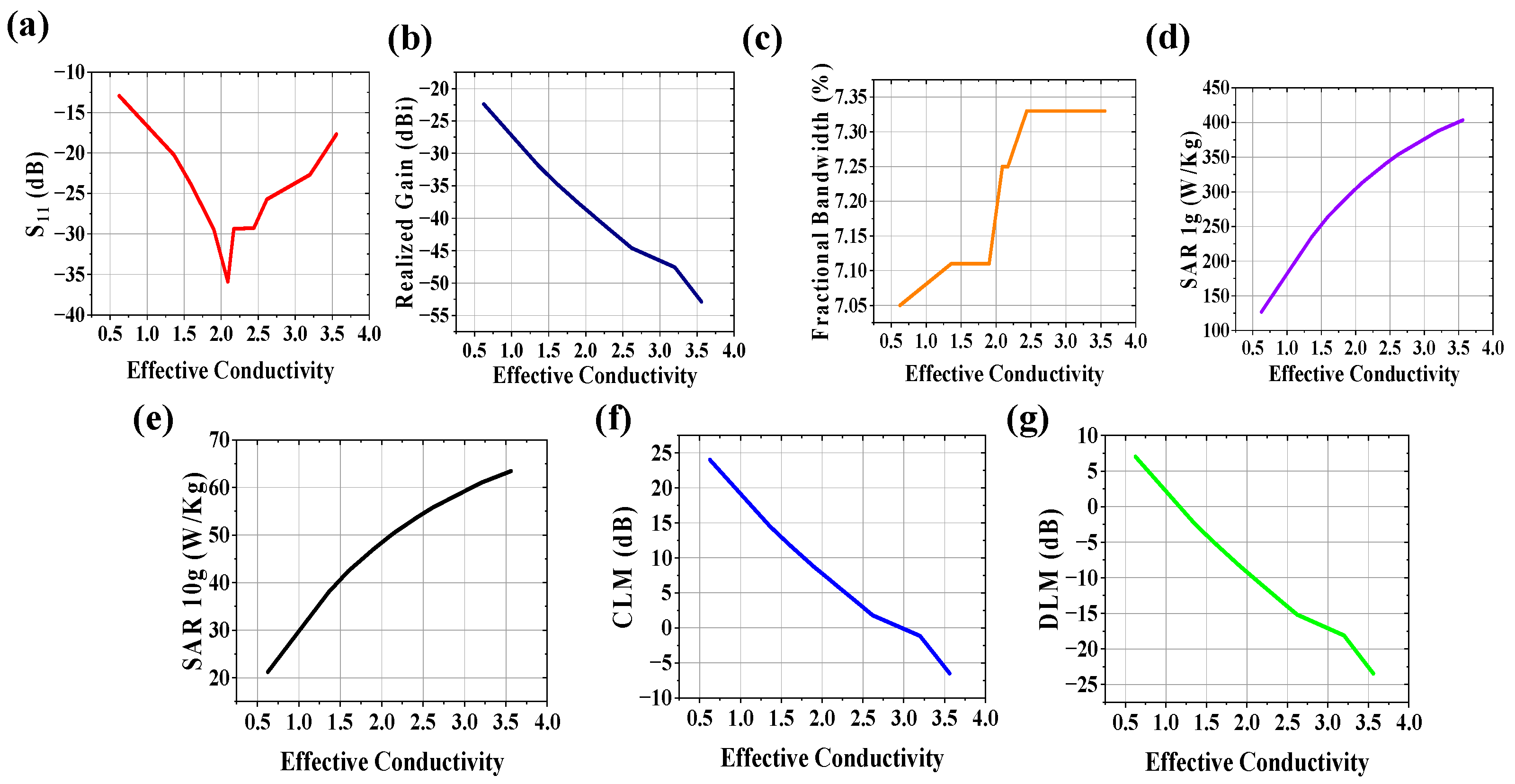

3.2. Variation of Effective Conductivity

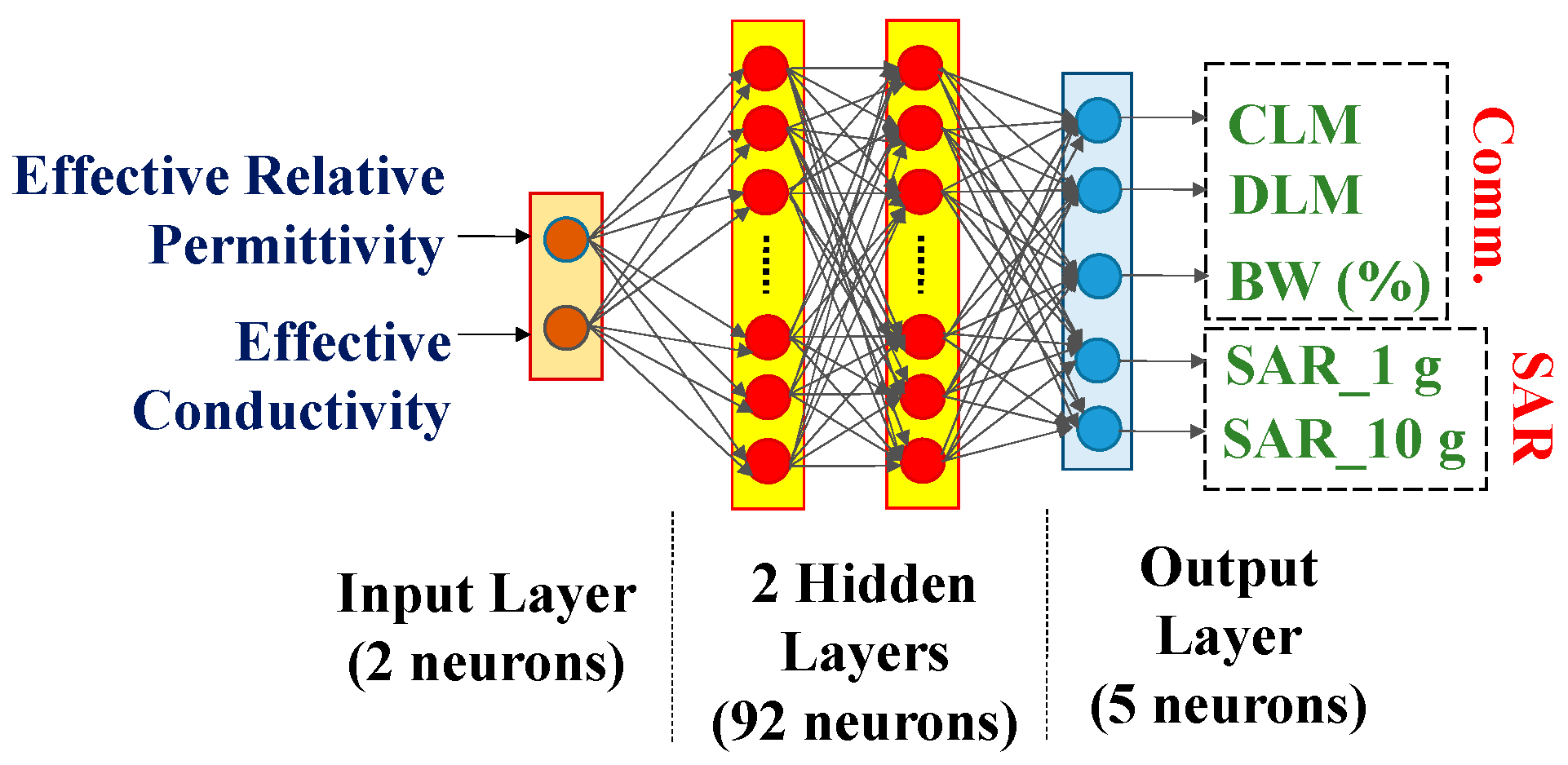

3.3. Variations in both Effective Relative Permittivity and Conductivity

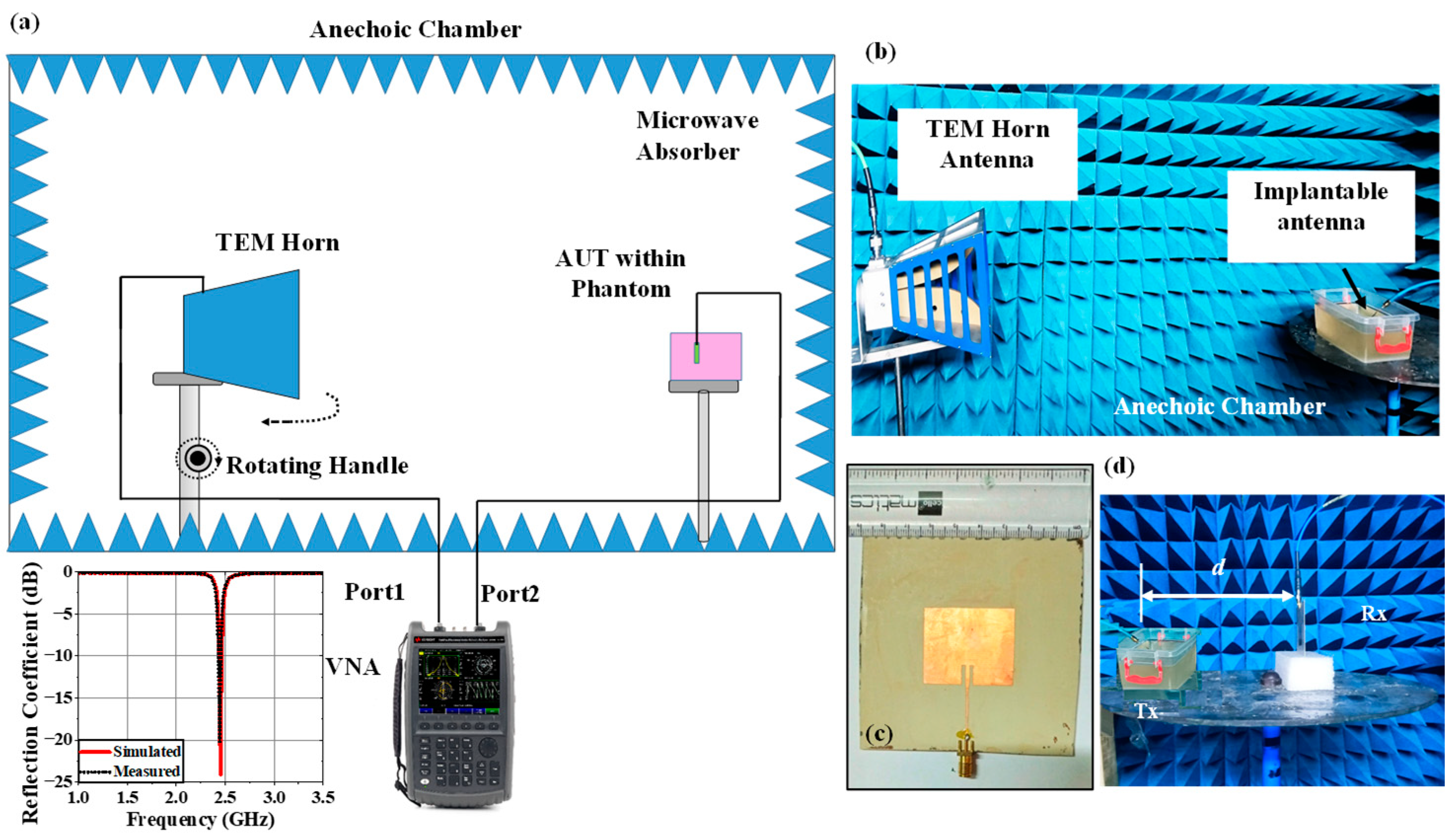

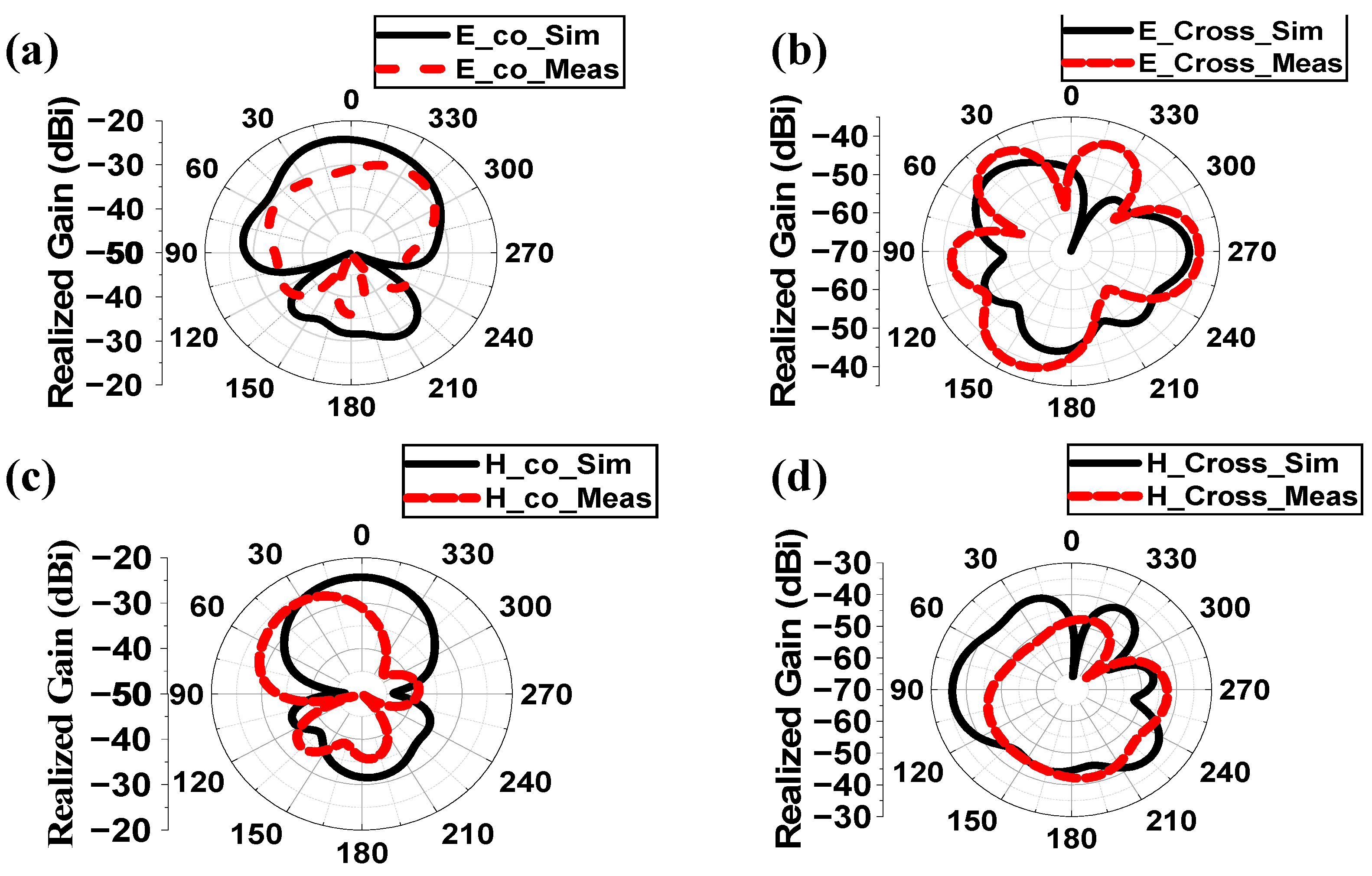

4. Experimental Setup and Measurement

4.1. Implantable Antenna System

4.2. Monitoring Antenna

4.3. Variation Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, M. S.; Ghosh, J.; Ghosh, S.; and Sarkhel, A. Miniaturized Dual-Antenna System for Implantable Biotelemetry Application. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters. 2021, 20(8), 1394-1398. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A. M. R.; Allstot, E. G.; Gangopadhyay, D.; and Allstot, D. J. Compressed Sensing System Considerations for ECG and EMG Wireless Biosensors. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and System. 2012, 6(2), 156-166. [CrossRef]

- Kiourti, A.; and Nikita, K. S. Numerical Assessment of the Performance of a Scalp-Implantable Antenna: Effects of Head Anatomy and Dielectric Parameters. Bioelectromagnetics, 2012, 34(3). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; and Rahmat-Samii, Y.; Implanted antennas inside a human body: simulations, designs, and characterizations. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. 2004, 52(8), pp. 1934-1943. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Shah, S. A. A.; and Yoo, H.; Miniaturized Dual-Band Circularly Polarized Implantable Antenna for Capsule Endoscopic System. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation. 2021, 69(4), 1885-1895. [CrossRef]

- Crumley, G. C.; Evans, N. E.; Burns, J. B.; and Trouton, T. G. On the design and assessment of a 2.45 GHz radio telecommand system for remote patient monitoring. Medical Engineering & Physics. 1999, 20(10), 750-55. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R. L.; Iskra, S.; McKenzie, R. J.; Chambers, J;. Metzenthen, B.; and Anderson, V. Assessment of SAR and thermal changes near a cochlear implant system for mobile phone type exposures. Bioelectromagnetics, 2007, 29(1), pp. 71-80. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kundu, A.; and Gupta, B.; Slot based Miniaturized Human Body Implantable Antenna Design at 2.45 GHz ISM Band. In 2022 IEEE Wireless Antenna and Microwave Symposium, Rourkela, India, 2022, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Yeap, K.; Voon, C.; Hiraguri, T.; and Nisar, H. A compact dual-band implantable antenna for medical telemetry. Microwave Optical Technology Letters. 2019, 61(9). [CrossRef]

- Karacolak, T.; Hood, A. Z.; and Topsakal, E. Design of a Dual – Band Implantable Antenna and Development of Skin Mimicking Gels for Continuous Glucose Monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Microwave theory and Techniques, 2008, 56(4). [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, T.; Karacolak, T.; and Topsakal, E. Characterization and Testing of a Skin Mimicking Material for Implantable Antennas Operating at ISM Band (2.4 GHz – 2.48 GHz). IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, 2008, 7, 418 – 420. [CrossRef]

- Zada, M. and Yoo, H. A Miniaturized Triple – Band Implantable Antenna System for Bio -Telemetry Applications. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, 2018, 66(12), 7378 – 7382. [CrossRef]

- ICNIRP. Guidelines for limiting exposure to electromagnetic fields (100 KHz to 300 GHz). Health Phys. 2020, 118(5), 483-524.

- Cleveland, R. F., Jr.; Sylvar, D. M;. and Ulcek, J. L. Evaluating compliance with FCC guidelines for human exposure to radiofrequency electromagnetic fields. FCC OET Bulletin. 1997, 65(97-01), Washington D.C.

- Department of Telecommunication (DoT). A Journey for EMF. 2012, www.dot.gov.in/journey-emf.

- Le, T. T.; Kim, Y. -D.; and Yun, T. -Y. A Triple-Band Dual-Open-Ring High-Gain High-Efficiency Antenna for Wearable Applications. IEEE Access. 2021, 9, 118435-118442. [CrossRef]

- Fear, E. C.; Meaney, P. M.; and Stuchly, M. A. Microwaves for breast cancer detection? IEEE Potentials. 2003, 22(1), 12-18. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, H., Alhajj, M., Sharma, S. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. StatPearls [Internet], 2023.

- Markova, M. S., Zeskand, J., McEntee, B., Rothstein, J., Jimenez, S. A., Siracusa, L. D. A role for the androgen receptor in collagen content of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2004, 123, 1052-1056. [CrossRef]

- Kopera, D. Impact of Testosterone on Hair and Skin. Endocrinology& Metabolic Syndrome, 2015. 4(3), 2015.

- Wang, X., Xu, M., Li, Y. Adipose Tissue Aging and Metabolic Disorder, and the impact of Nutritional Inventions. Nutrients. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Walia, N. S., Raj, R., and Tak, C. S. Gottron’s syndrome. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy. 2001, 67.

- Szewc, M., Sitarz, R., Moroz, N., Maciejewski, R. and Wierzbicki, R. Madelung’s disease – progressive, excessive, and symmetrical deposition of adipose tissue in the subcutaneous layer: case report and literature review. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy. 2018, 11, 819-825. [CrossRef]

- Ghodgaonkar, D. K.; Gandhi, O. P.; and Iskander, M. F. Complex permittivity of human skin in vivo in the frequency band 26.5-60 GHz. IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium. Transmitting Waves of Progress to the Next Millennium. 2000 Digest. Held in conjunction with: USNC/URSI National Radio Science Meeting (C, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2000, 2, 1100-1103.

- Hwang, H.; Yim, J.; Cho, J.-W.; Cheon, C.; and Kwon, Y. 110 GHz broadband measurement of permittivity on human epidermis using 1 mm coaxial probe. In IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest, 2003, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1, 399-402.

- Boric-Lubecke, O.; Nikawa, Y.; Snyder, W.; Lin, J.; and K. Mizuno, Novel microwave and millimeter-wave biomedical applications. In 4th International Conference on Telecommunications in Modern Satellite, Cable and Broadcasting Services. TELSIKS'99 (Cat. No.99EX365), Nis, Yugoslavia, 1999, 186-193.

- Peyman, A.; Kos, B.; Djokic, M.; Trotovsek, B.; L.-Stokin, C.; Sersa, G.; and Miklavcic, D. Variation in Dielectric Properties Due to Pathological Changes in Human Liver. Bioelectromagnetics. 2015. 36,603-612. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. Statistical analysis of detuning effects for implantable microstrip antennas. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Utah, 2007.

- Vidal, N.; Curto, S.; Lopez Villegas, J. M.; Sieiro, J.; and Ramos, F. M. Detuning study of implantable antennas inside the human body. Progress in Electromagnetics Research. 2012. 124, 265-283. [CrossRef]

- Ekpo, S. C.; and George, D. Impact of Noise Figure on a Satellite Link Performance. IEEE Communications Letters. 2011, 15(9), 977-979. [CrossRef]

- Ekpo, S. C. Parametric System Engineering Analysis of Capability-Based Small Satellite Missions. IEEE Systems Journal. 2019, 13, (3), 3546-3555. [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Li, H.; Ding, X.; Shao, W.; and Xiao, S. Compact and Broadband Circularly Polarized Implantable Antenna for Wireless Implantable Medical Devices. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters. 2023, 22(6), 1236-1240. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Du, X.; Bärhold, M.; Wang, Q.; and Plettemeier, D. MICS-Band Helical Dipole Antenna for Biomedical Implants. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters. 2022, 21(12), 2502-2506. [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Cho, Y.; Shah, I. A.; Hayat, S.; Basir, A.; and Yoo, H. Compact Dual-Band MIMO Implantable Antenna System for High-Data-Rate Cortical Visual Prostheses Applications. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation. 2024, 72(8), 6374-6386. [CrossRef]

- Ashvanth, B.; and Partibane, B. Miniaturized dual wideband MIMO antenna for implantable biomedical applications. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett.. 2023, 65(12), 3296–3302.

- Iqbal, A.; Al-Hasan, M.; Mabrouk, I. B.; and Denidni, T. A.; Deep-Implanted MIMO Antenna Sensor for Implantable Medical Devices. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2023, 23(3), 2105-2112. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Sura, P. R.; Smida, A.; Al-Hasan, M.; Ben Mabrouk, I.; and Denidni, T. A. Dual-Band 3-D Implantable MIMO Antenna for IoT-Enabled Wireless Capsule Endoscopy. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2024, 11(19), 31385-31393. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.; Garcia-Miquel, A.; Lopez-Villegas, J. M.; Sieiro, J. J. and Ramos, F. M. Influence of phantom models on implantable antenna performance for biomedical applications. In 2015 9th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Lisbon, Portugal, 2015, 1-4..

- Perez, M. D.; Jeong, S. H.; Raman, S.; Nowinski, D.; Wu, Z.; Redzwan, S.; Velander, J.; Peng, Z.; Hjort, K.; and Augustine, R. Head-compliant microstrip split ring resonator for noninvasive healing monitoring after craniosynostosis-based surgery. Healthcare Technology Letters. 2020, 7(1), 29-34. [CrossRef]

- Patra, K. Analytical Modelling of Microstrip Travelling Wave Antennas. PhD Dissertation. Electronics and Tele-Communication Engineering, Jadavpur University, India, 2018.

- IEEE Standard for Safety Levels with Respect to Human Exposure to Electric, Magnetic, and Electromagnetic Fields, 0 Hz to 300 GHz – Redline. IEEE Std C95.1-2019 (Revision of IEEE Std C95.1-2005/ Incorporates IEEE Std C95.1-2019/Cor 1-2019) – Redline. 2019, 1-679, 4.

Short Biography of Authors

|

SOHAM GHOSH was born in Kolkata, India, in 1997. He received the B. Tech degree in Electronics and Communication Engineering from Academy of Technology affiliated to Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, Kolkata, India in 2019 and M.E. degree in Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India in 2022. He is currently pursuing Ph. D. degree from the Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Jadavpur University, India since 2022. His research interests include electromagnetic theory, implantable antenna design and communication, mathematical modeling of antenna, 5G antennas, Terahertz antennas etc. He has authored three conference papers and coauthored five conference papers published in IEEE. He has authored three journal papers and coauthored two journal papers published in different journals. He is a member of IEEE Microwave Theory and Techniques- Student Branch Chapter, Jadavpur University under Kolkata Section, India. He received University Gold medal from Jadavpur University, India in 2022. He received “Best Student Paper Award” in the conference IEEE Wireless Antenna and Microwave Symposium in 2022. |

|

SUNDAY C. EKPO obtained the MSc. Degree in Communication Engineering from the University of Manchester, Manchester, U.K. in September 2008 and proceeded for his PhD degree in Electrical and Electronic Engineering at the same institution. He holds a PGC. in Academic Practice; MA. in Higher Education; Chartered Engineer; and Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, UK. He is a Chartered Engineer (CEng) with experience of carrying out world-leading fundamental, use-inspired and applied research projects on sustainable radio communication and satellite systems engineering. He designs reconfigurable / digitally-assisted architectures to achieve ultra-low energy and spectrum-efficient multi-radio multi-coverage/range solutions/ internet of things products. He is a Senior Lecturer in Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK; leads the Communication and Space Systems Engineering research team. He is a British Council Stakeholder for the Innovation for African Universities Projects and Community of Practice. His research work spans 120+ peer-reviewed and refereed technical publications and attracted £1.5m+ grants income. He is a recipient of the Huawei's Influential Thinkers in Engineering and Technology Recognition 2019, and member of the UK Research and Innovation Talent Panel College; Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Peer Review College; Institution of Engineering and Technology, UK; internationally recognized R&D leader in Advanced Manufacturing of Electronics; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Member of the Association of International Education Administrators, USA; Carbon Literacy Champion for the Electrical & Electronic Engineering program; and Principal Investigator of the Sony’s Sensing Solutions University Program. |

|

FANUEL ELIAS is an accomplished Electrical and Electronics Engineering researcher who received his first-class BEng Degree in Electrical and Electronics Engineering from the Manchester Metropolitan University, UK, in 2023. He is pursuing a PhD in RF Engineering and specializes in Reconfigurable Holographic Multi-Radio Metasurface Rectennas for Ultra-low Power 5G/Wi-Fi 6/6E/7/Hallow Applications. His award-winning final year project focused on Reconfigurable Wireless WI-FI6/6E/7/5G Energy Harvesting Design. He's also a research assistant for the Royal Academy of Engineering, contributing to Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) sensors. His expertise encompasses RF engineering, including subsystem design, rectifiers, antenna design, and RF transceiver characterization. His research interests lie in metamaterial and metasurface analysis, specifically emphasizing energy harvesting and antenna applications, driving innovation in wireless communication technology. He served on the technical programme committee for the Second International Adaptive and Sustainable Science, Engineering and Technology (ASSET) Conference 2023 and as Publicity Chair for the Third ASSET Conference 2024, both held in Manchester, UK. |

|

STEPHEN ALABI holds a BSc in Engineering Physics and a MSc in Advanced Process Design for Energy from The University of Manchester, UK. He currently leads the R&D of passive, hybrid and active energy-efficient and ultra-low-carbon internet of things sensors electronics innovations using advanced nanoscale integrated manufacturing technology for the global net zero attainment. He is the Founder and Managing Director of SmOp CleanTech and has overall responsibility for its operational performance. Stephen is also the driving force behind SmOp’s strategic plan. His background is in the scientific aspects of the Company’s project which has aided products delivery and knowledge transfer. His involvement in setting the strategic direction of the business and authority to commit resources to support Research and development projects make him the ideal candidate to act as Senior Business Employee. He was the Technical Programme Chair at the Second International Adaptive and Sustainable Science, Engineering and Technology (ASSET) Conference 2023 held in Manchester, UK and gave Keynote Speeches on “Hybrid Wireless Power Transfer for Passive Electronic Appliances” (ASSET 2023); and “Advanced Manufacturing of Electronics for Green Energy Harvesting Use Cases and Applications” (ASSET 2024). SmOp CleanTech was the Diamond Sponsor of the ASSET Conference and He is an Executive Stakeholder of the ASSET Council has 10 peer-reviewed and refereed technical publications and 10+ peer-reviewed articles on “green energy development for future-generations telecoms infrastructure” in-preparation. Under Stephen’s R&D engineering leadership, SmOp has developed intellectual properties and patentable green radio frequency communication and low-carbon hybrid RF-solar energy harvesting products for different horizontal and vertical use cases spanning civil and commercial applications for the major industries/sectors. |

|

BHASKAR GUPTA was born in Kolkata, India, in 1960. He received the B.E.Tel.E., M.E.Tel.E., and Ph.D. (Eng.) degrees from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, in 1982, 1984 and 1996, respectively. He is Ex-Vice Chancellor at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India where he has been teaching since 1985. He has published numerous research articles in refereed journals and conferences and co-authored three books of advanced research topics. He is a Senior Member of IEEE, Fellow of IETE, Fellow of Institution of Engineers (India), and Life Member of SEMCE (I). He was the Chairman of WB Centre, ET division of IE(I) and Vice Chair, IEEE Kolkata Section. He served as referee, Associate Editor and Guest Editor in different internationally acclaimed journals. His present area of interest is Planar Antennas, Implantable and Wearable Antennas etc. in Microwave Engineering and Antennas. He has published about 200 research articles in refereed journals including IEEE journals and conferences and coauthored two books on advanced research topics, published internationally. |

| Ref. | Freq. (GHz) | S11 (dB) |

Gain (dBi) | SAR_1g (1W) (W/Kg) | CLM (dB) | DLM (dB) | Comm. range (m) | Uncertain Parameters | Samples | Variation Analysis Techniques | Variation in parameters Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32] | 2.4 | -25 | -24.7 | 697.5 | No | No | 17 (7kbps), 4.3 (100 kbps) and 1.4 (1 Mbps) |

No | No | No | No |

| [33] | 0.4 | -20 | -18.9 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| [34] | 0.915, 2.45 | -25, -40 |

-30.47, -24.71 |

658, 589 | No | No | 2 | No | No | No | No |

| [35] | 0.915, 2.45 | -20, -37 |

-36, -30.1 |

333 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| [36] | 0.915 | -20 | -23.23 | 270.3 | No | No | 13 | Effective permittivity | 6 | Cartesian plot | Sensing Performance |

| [37] | 0.915, 2.45 | -19, -15 |

-26.30, -20.9 |

306.19, 252.36 | No | No | 8 | No | No | No | No |

| [38] | 0.402, 2.45 | No | -37, -24.5 |

No | No | No | No | Phantom Size | 2 | Cartesian plot | Gain, efficiency |

| [39] | 2.45 | -11 | No | No | No | No | No | Relative Permittivity | 6 | Cartesian plot | S11 and frequency |

| This Work | 2.5 | -45.9 | -38.42 | 220.26 |

20.73 (d = 1m, Ts =13K) (First) |

9.28 (d = 1m, Ts =13K) (First) |

15 (7kbps), 10 (100 kbps) and 3.5 (1 Mbps) |

Effective permittivity and Conductivity | 2500 |

ANN modeling (First) |

CLM, DLM, bandwidth and SAR performance (First) |

| Sample | Effective Properties | Simulation | ANN | % error of prediction w.r.t Simulation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ɛeff | σeff | 1 g | 10 g | 1 g | 10 g | 1 g | 10 g | |

| 1 | 46.02 | 0.63 | 250.15 | 65.09 | 247.60 | 64.98 | 1.03 | 0.17 |

| 2 | 46.02 | 0.92 | 147.78 | 43.57 | 145.98 | 42.65 | 1.23 | 2.16 |

| 3 | 46.02 | 3.56 | 302.63 | 74.26 | 300.98 | 75.95 | 0.55 | 2.23 |

| 4 | 49.80 | 1.80 | 227.38 | 61.01 | 227.22 | 61.42 | 0.07 | 0.67 |

| 5 | 51.69 | 1.51 | 203.46 | 56.43 | 202.65 | 57.23 | 0.40 | 1.40 |

| 6 | 53.59 | 1.80 | 225.20 | 60.72 | 226.18 | 60.55 | 0.43 | 0.28 |

| 7 | 55.48 | 2.10 | 348.30 | 64.03 | 345.45 | 65.22 | 0.83 | 1.82 |

| 8 | 57.37 | 0.63 | 109.15 | 33.91 | 108.45 | 33.22 | 0.65 | 2.08 |

| 9 | 59.26 | 0.92 | 127.85 | 42.47 | 125.65 | 42.58 | 1.75 | 0.26 |

| 10 | 63.04 | 2.97 | 231.16 | 68.81 | 235.22 | 69.18 | 1.73 | 0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).