1. Introduction

New wearable and portable medical monitoring and screening techniques are investigated for future’s wireless healthcare and telemedicine applications. The development and optimization of emerging techniques require numerous trials and experimentation before they can pass the standards of clinical applications. These trials are generally performed on humans or animals like rats, pigs, or monkeys. This process proves to be very costly in terms of time and monetary aspects and is often not very straightforward due to ethical issues. Therefore, the development and the use of realistic simulation and emulation platforms is essential for evaluating techniques already in their initial phase. Emulation platforms are usually build with human tissue mimicking phantoms [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] or with animal tissues, e.g pork tissues [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Recently, there has been strong interest on the development of more accurate and realistic phantoms for different sensing techniques based on, such as microwaves, optics, and acousto-optics. The focus of this paper is in microwave technique.

1.1. Microwave technique and its advantages

Microwave sensing is recognized as one of the most promising emerging techniques for different medical monitoring and screening applications due to its several advantages: sufficient propagation depth enabling deep tissue monitoring, good resolution, low power, low cost, reliability, and security. Especially at the lower parts of the microwave frequency band (1-4GHz), superior propagation depth can be achieved compared to other modalities. Thus it is considered suitable for deep tissue monitoring applications with higher penetration depth requirements, such as whole brain screening and breast health monitoring, as well as for implant communications, such as capsule endoscopy. Instead, at higher frequencies, a better resolution can be achieved since the wavelength in the tissue decreases as the frequency increases. Therefore, the microwave technique is contemplated as a suitable candidate for deep tissue monitoring and implant communications.

During the past decade, several microwave techniques-based studies have been proposed for different medical and healthcare applications [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In recent years, particularly phantom-based studies have been under intensive sly conducted for development of teh different applications. The next subsection gives an overview of the state-of-the-art tissue mimicking phantom development for different microwave technique-based applications.

1.2. State-of-the-art for tissue-mimicking phantom development for microwaves

The characteristics of phantoms allow quantifying the state, shape, and operation mechanism of the actual human body without the fuss and risk of using any living being. Furthermore, phantoms have a lot of advantageous features such as a fast construction process, low cost, repeatability, and reusability which makes it an even more suitable option than human and animal trials. Due to all these reasons, many different tissue mimicking (TM) phantom models are proposed in the literature to simulate different organs/parts of the human body. These phantoms can be categorized into several classes based on the materials used (solid, liquid, hybrid), number of layers, purpose (sensing, imaging, detection), and detail of architecture. The design of a good phantom for microwave studies essentially requires the phantom to mimic not only the shape and physical properties of the original biological tissue but also precisely replicate its dielectric properties. However, a phantom model with very fine details of the tissue results in an intricate design challenging to manufacture and reproduce. Therefore, a majority of phantom models proposed in the literature are very simplistic and are created based on crude assumptions.

1.3. Brain Phantoms

In [

21], a six-layered human head phantom is proposed for the sensor-based microwave brain imaging system (SMBIS) for the diagnosis of tumors in the head. The phantom model consists of Dura, CSF, White Matter, Gray Matter, Fat, and Skin for a wideband frequency band (1 GHz to 4 GHz).vA tissue-mimicking 3D head phantom is fabricated with Dura, CSF, gray matter, white matter, and blood (haemorrhage) agar, gelatin, distilled water, cornflour, propylene glycol, sodium azide, and sodium chloride in [

22]. The presented phantom is tested for a frequency range of 1GHz to 4GHz.

Karadima et al. [

23] proposed a brain phantom model for the validation of microwave tomography with the DBIM-TwIST algorithm for 0.5 to 2.5 GHz frequency. The phantom consists of the average brain, CSF/blood, and ischemia layers made from gelatine power, kerosene, safflower oil, propanol, and surfactant. The effect of aging on the dielectric properties of phantoms is also studied. In [

24,

25] a head phantom to test microwave systems for brain imaging is proposed and tested for 1–4 GHz. The brain phantom consists of CSF, grey and white matter, and bold. The dielectric properties of the fresh sample and after aging of four weeks are presented. The recipe for the proposed phantom has water, corn flour, gelatin, agar, sodium azide, and propylene glycol as the main components.

The heterogeneous brain phantom model presented by Najafi et al. [

26] has polytetrafluoroethylene and methyl methacrylate as a bone and soft tissue and the phantom was tested for stereotactic radiosurgery. Joachimowicz et al. [

27] proposed the use of TX-100 and salted water for the preparation of brain phantom for the frequency range of 0.5–6 GHz band. The phantom consists of the brain, CSF, muscle, bone, and blood made by mixing TX-100 and NaCl in different compositions. Pokorny et al. [

28] proposed an Anatomically and dielectrically realistic 2.5 D 5-layer reconfigurable head phantom. The phantom consists of 5 different layers that mimic the scalp, skull, cerebrospinal fluid, brain, and stroke regions which are synthesized from urethane rubber, graphite powder, carbon black powder, and acetone. The liquid brain consists of a solution of deionized water, isopropanol, and NaCl.

Mobashsher and Abbosh [

29] proposed a human head phantom wherein the skull cavity is constructed using 3-D-printed molds representing gray matter, white matter, Dura, CSF, eye, cerebellum, spinal cord, and blood. The phantom is tested at a frequency range of 0.5-4 GHz and water, corn flour, gelatine, agar, sodium azide, propylene glycol, and NaCl are utilized in the construction of the phantom model. Another human brain phantom is proposed in [

30] by Suleiman et al. for a frequency range of 1 to 4 GHz. The phantom is constructed using appropriate combinations of water, corn flour, gelatin, agar, sodium azide, and propylene glycol, and dielectric properties from [

31] are taken as references for preparing the phantom. The measurements reported in [

30] are repeated after two months of phantom creation to confirm the stability of the properties over time.

Luis et al. [

32] proposed a brain phantom consisting of brain, fat, muscle, gray matter, white matter, and blood. The bone is made of plaster, water, and ethyl alcohol is used for muscle while the gray matter is composed of water, sugar, NaN3, and Agar. The white matter of the phantom is constructed using water and ethyl alcohol, while the blood sample was created using a mixture of water, sugar, NaN3, and Agar. Another phantom model is proposed in [

33] by Konstantinos et al. and tested for four frequency bands of 1.1 GHz, 1.8 GHz, 2.4 GHz, and 2.8 GHz. Two cylindrical containers with radii of 7 cm and 2 cm are utilized for the phantom. De-ionized water at room temperature and tepid de-ionized water were filled in the two containers to mimic the dielectric properties of the brain during the experiments.

A brain phantom for the ISM 2.4-GHz band is proposed in [

34] wherein a 4-mm-thick skin is used around the phantom with 10-mm-thick cortical bone. Further, the phantom model consists of grey and white matter and muscle. The conductivity and relative permittivity are measured and found to match the actual biological brain. A polyvinyl chloride (PVC) based head phantom is proposed in [

35] by Mohammed et al. which consists of soft brain tissues with main ingredients as propylene glycol, water, grape seed oil, commercial dishwashing liquid, sodium azide, corn flour. Authors in [

36] used the recipe from [

29] to fabricate a five-layer human brain phantom consisting of Dura, CSF, gray matter, white matter, and blood for hemorrhage. The basic materials such as Agar, gelatin, corn flour, sodium azide, sodium chloride, distilled water, and propylene glycol are utilized in making this phantom model.

A skull phantom filled with liquids and semi-solids is proposed in [

37] for brain hemorrhage studies. The thickness of the skull bone is taken to be 7 mm and the recipe consists of a mixture of epoxy, SrTiO3 powder, ethanol, distilled water, glycerol, sucrose, and salt. Shahidul et al. [

38] proposed a phantom model with CSF, dura, gray matter, white matter, and blood for 1–4 GHz. Sterile water, corn flour, gelatin, agar, sodium azide, propylene glycol, and sodium chloride are used in the construction of different parts of the phantom. Jacob et al. [

39] proposed a 4-layer phantom model with skin, skull, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain for 2-3 GHz frequency. The thickness of the skin is 5 mm, CSF is kept at 10 mm and the brain is 5 mm with agar, polyethylene powder (PEP), TX-151, and sodium chloride as main ingredients. A brain phantom model based on a 3D printed structure is presented in [

40] wherein the biological tissues of the brain are mimicked by a liquid solution of TX-100 and NaCl

1.4. Breast Phantoms

Joachimowicz et al. [

41] proposed a breast phantom for microwave imaging in the 0.5–6 GHz range using the one-pole Debye model. The effect of time and temperature on the stability of the proposed phantom is studied. Porter et al. developed a realistic breast phantom for breast cancer detection using n-propanol, deionized water, bloom gelatin, formaldehyde, oil, and ultra ivory detergent [

42]. The phantom consists of skin, fat, small gland, and large gland for tumor detection. A similar oil-in-gelatin recipe is utilized in four heterogeneous breast phantoms in [

43]. The phantoms are constructed in order to cover the complete range of volumetric breast densities for microwave imaging experiments. Homogenous as well as heterogeneous realistic breast phantoms constituting skin, fat, glandular tissue, and tumors are presented by Islam et al. in [

44]. The proposed phantoms are tested for a 3.1–10.6 GHz frequency range.

Even though these oil-in-gelatin phantoms can replicate the dielectric properties of actual breast tissues, they are hypersensitive to environmental exposure and their properties can deteriorate with time. Therefore, liquid-based phantoms constructed by mixtures of distilled water and polyethylene glycol mono phenylether (Triton X-100) are proposed in literature which are easy to generate and conserve over time [

45]. Gunnarsson et al. also proposed a liquid-based breast phantom model using Triton X-100, water, and salt mixtures [

46,

47,

48]. A study on Triton X-100 and distilled water-based phantom models for 0.5–12 GHz frequency band is presented in [

49]. The phantoms are tested for their temperature stability in the range of 18–30 degree celsius. Authors in [

50] present an interesting survey on numerical breast phantoms based on software and physical phantom models. Garrett and Fear presented a breast phantom made from carbon and rubber [

51]. The phantom model is generated using a 3D printing technique and consists of skin, fat, glandular, and tumor.

1.5. Objectives and Novelty of this Study

This paper is an extension and complement to our previous studies in [

15,

52,

53].

The first objective of this paper is to present a new approach for developing and evaluating realistic emulation platforms for human head and torso areas. The main focus is on 3D phantom emulation platforms for a) brain tumor/stroke detection, b) breast cancer detection, and b) abdominal disorder detection e.g. using capsule endoscopy. The paper describes phases of phantom development including several new recipe trials, whose suitability is verified with dielectric property measurement.

The second objective of this paper is to present a new method to verify the feasibility and reliability of the phantoms for practical scenarios using electromagnetic simulations to calculate antenna reflection coefficients and channel parameters with the tissue layer simulations having the same dielectric properties as the developed phantoms. The results are compared using the reference layer model with dielectric properties of realistic human tissues.

The third objective is to study the impact of phantom cooking temperature on the dielectric properties of the final phantom.

This paper is organized as follows: Section II presents Materials and Methods: Materials and procedures for the development of 3D molds and phantoms. Additionally, simulation models used in the phantom verification are shown. Measurement setups for dielectric property and S-parameters evaluations are explained. Results are presented in Section III for dielectric property measurements, and phantom verifications with electromagnetic simulations. Discussion and future work are presented in Section IV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Used in Phantom Development

The characteristics of human tissues vary clearly depending on their water content as seen in

Table 1 [

54]. Depending on the application it can be crucial to use multilayer models in the evaluations instead of averaged models. The human tissue mimicking phantoms is prepared using ingredients and materials which are easily accessible either in supermarkets, pharmacies, or chemical stores. The main materials are distilled water, gelatine, sunflower oil, sugar, Natrium Chloride (NaCl), Xanthum, and Propylene Glycol (pure, 98 %). The recipes for different human tissues consist of varying amounts of these ingredients as shown in

Table 2. Recipes 1-5 are improved modifications of the recipes presented in several sources from literature, the muscle/intestinal recipe is from [

6], and the fat phantom recipe is the novel proposal by authors from [

52] with new ingredients.

2.2. Procedures to prepare phantoms for different tissues

This section describes the details of the procedures to prepare different tissue phantom recipes. The description is divided into four different categories depending on the used ingredients a) Brain, Skin, and Tumor1 Phantoms, b) glandular phantom, c) Muscle phantom, d) fat phantom.

2.2.1. Brain, Skin and Tumor 1 phantoms

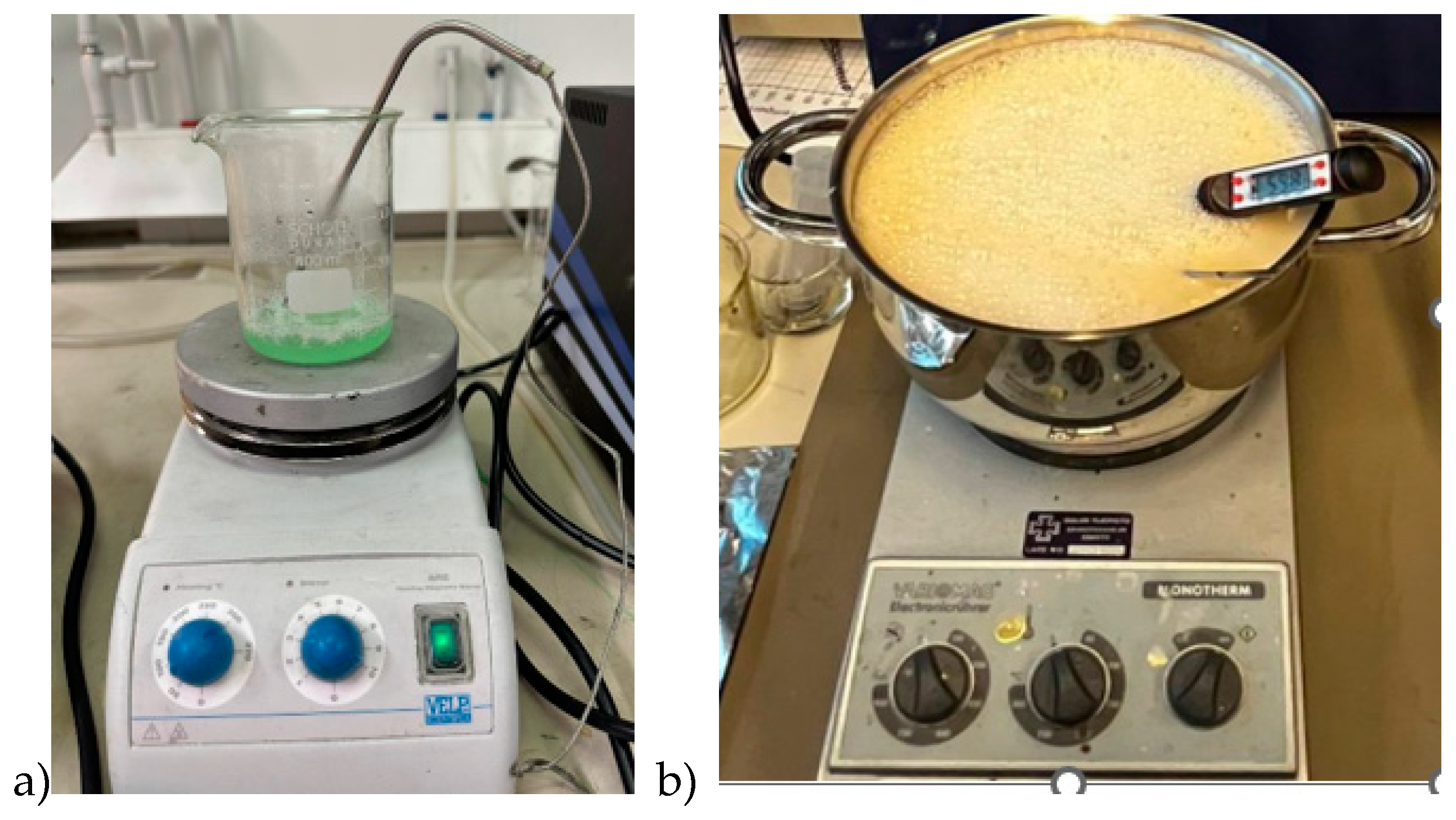

Skin, tumor, and average brain phantoms are prepared using the same ingredients: distilled water (DI), gelatine, sunflower oil, and dishwashing liquid but with different amounts of ingredients. Furthermore, in the skin and tumor phantom preparation, DI water is heated only to 65°C whereas, in the brain phantom preparation, the water is heated to 85°C.

Firstly, all the ingredients were measured separately using a high-precision scale. Gelatine was added to distilled water and the mixture was heated slowly till 65°C (in skin and tumor phantom case) while stirring on a magnetic hot-plate stirrer. Sunflower oil was heated separately until 65°C before adding to the water-gelatine mixture together with dishwashing liquid. The stirring continued for around five minutes. The mixture was then removed from the hot plate while being continuously stirred, and the heat was turned off, allowing the temperature to drop to about 50°C. The mixture was poured on the mold polymerization. Molds are described and illustrated in

Section 2.3. For tumor and smaller skin tissue phantoms, a beaker of size 0.5 l is sufficient (

Figure 1a), but for realistic-sized brain phantoms, a large kettle is needed (

Figure 1b). Stirring should be done gently to avoid excessive air bubbles which affect dielectric properties. Air bubbles can also be gathered from the phantom surface before solidification.

2.2.2. Muscle and Intestinal Phantoms

The procedure for preparing muscle phantom mixture is similar to that of the skin phantom except NaCl is added to DI water before adding the gelatin. Muscle phantom recipe is commonly used for intestinal phantoms since the dielectric properties of the muscle and intestines are close to each other.

When preparing a layered muscle phantom, the phantom mixture is poured on a tray of size 40 cm x 40 cm for solidification. The tray is filled until 21 mm depth to obtain a muscle layer of 20 mm thickness since in this study case, the phantom shrinks during the solidification process by approximately 4%. Intestinal phantoms can be prepared as layered phantoms or as realistic-shaped phantoms as described in Subsection 2.3.3.

2.2.3. Fat Phantoms

There are several fat phantom recipes in the literature but due to the high amount of sunflower oil, the polymerized phantoms are fatty, wet, break easily, and hence difficult to use with 3D phantom models. These challenges with existing phantom recipes encouraged authors to develop a more solid fat phantom using pure propylene glycol, which is presented for the first time in [

52]. This paper briefly summarizes the procedure steps.

On a hot plate stirrer, gelatine was added to distilled water and the mixture was heated slowly till 65°C while stirring for 5 minutes. Propylene glycol is heated separately to around 50 °C and then added to the gelatin- DI water mixture, which is continuously stirred till the solution reaches 65°C. Then xanthan is added to the solution thoroughly. Finally, dishwashing liquid is added and well mixed into the solution. The mixture is poured into an appropriate mold and refrigerated for 24 hours.

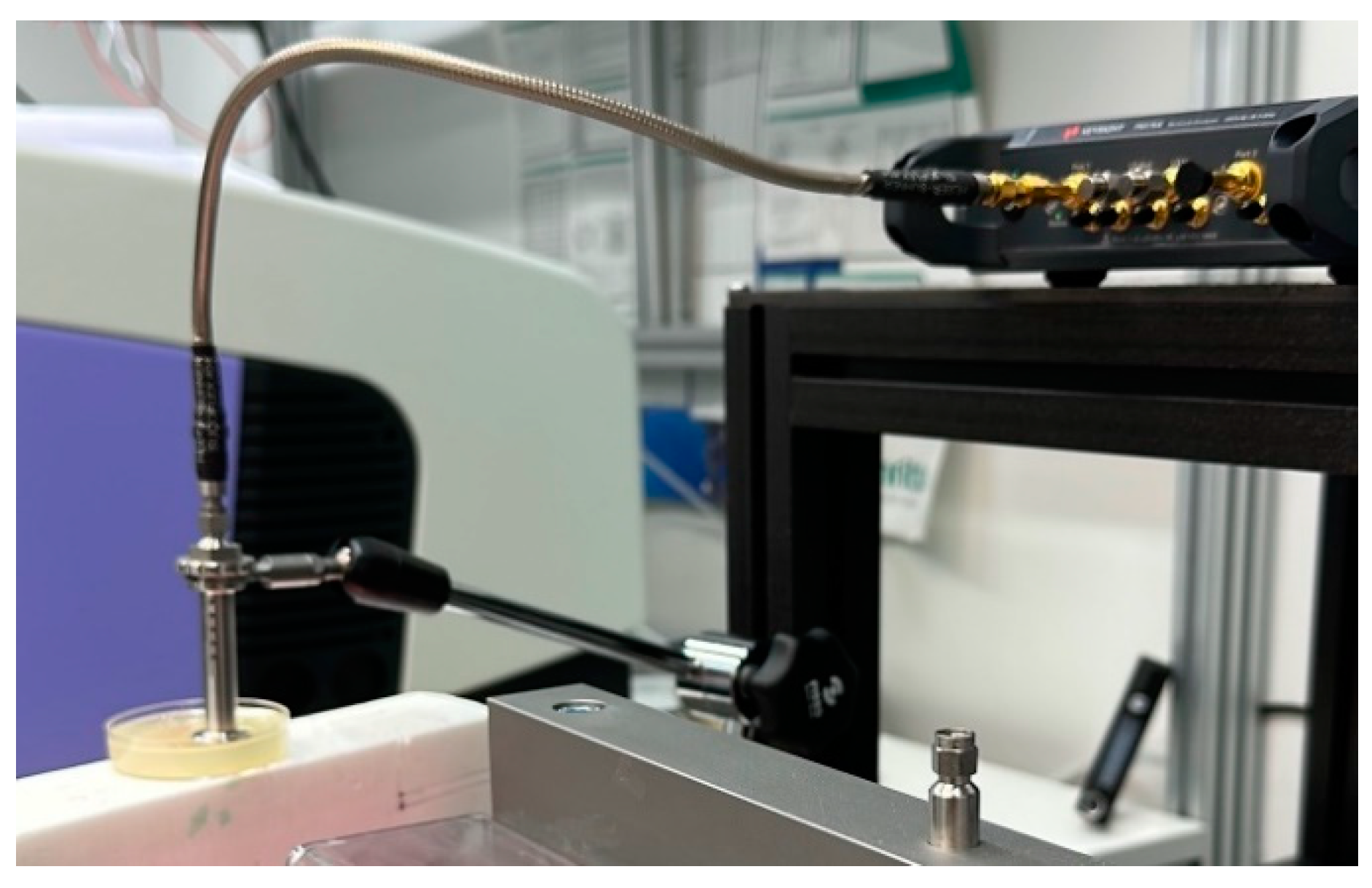

2.2.4. Dielectric Property Measurements

Dielectric properties of the phantoms were measured using Vector Networks Analyzer (VNA) 8720ES connected to SPEAG’s Dielectric Assessment Kit (DAK). The DAK software converts the measured complex S11 of the phantom sample into the complex permittivity and conductivity. The application operation frequency range is 200 MHz to 20 GHz with a sweep of 117 points. The device was calibrated using Speag’s calibration kit “Head”.

The dielectric properties of the sample were measured twice at 3 different locations and are given as an average of all. The measurement setup for measuring the dielectric properties of the phantom sample is presented in

Figure 2.

2.2.5. Verification of Phantoms with EM-Simulations

The authors in [

52] presented a novel idea for phantom verifications using tissue layer model electromagnetic simulations by which the proposed fat phantom was evaluated. In the simulations, the antenna reflection coefficient, i.e. S11 parameter, was calculated with tissue layer models. For the fat tissue layer, the dielectric properties are varied between the reference case with real fat tissue values from [

54] and fat phantom mixture solutions. The aim is to see how much small differences in the dielectric properties of the phantoms affect the simulated antenna reflection coefficients. The results will provide insight into how close the phantom-based antenna performance evaluations are to the realistic case. This idea is further extended in this paper to verify both S11 and channel transfer function S21 parameters. In this paper, the evaluations are carried out also for other phantoms.

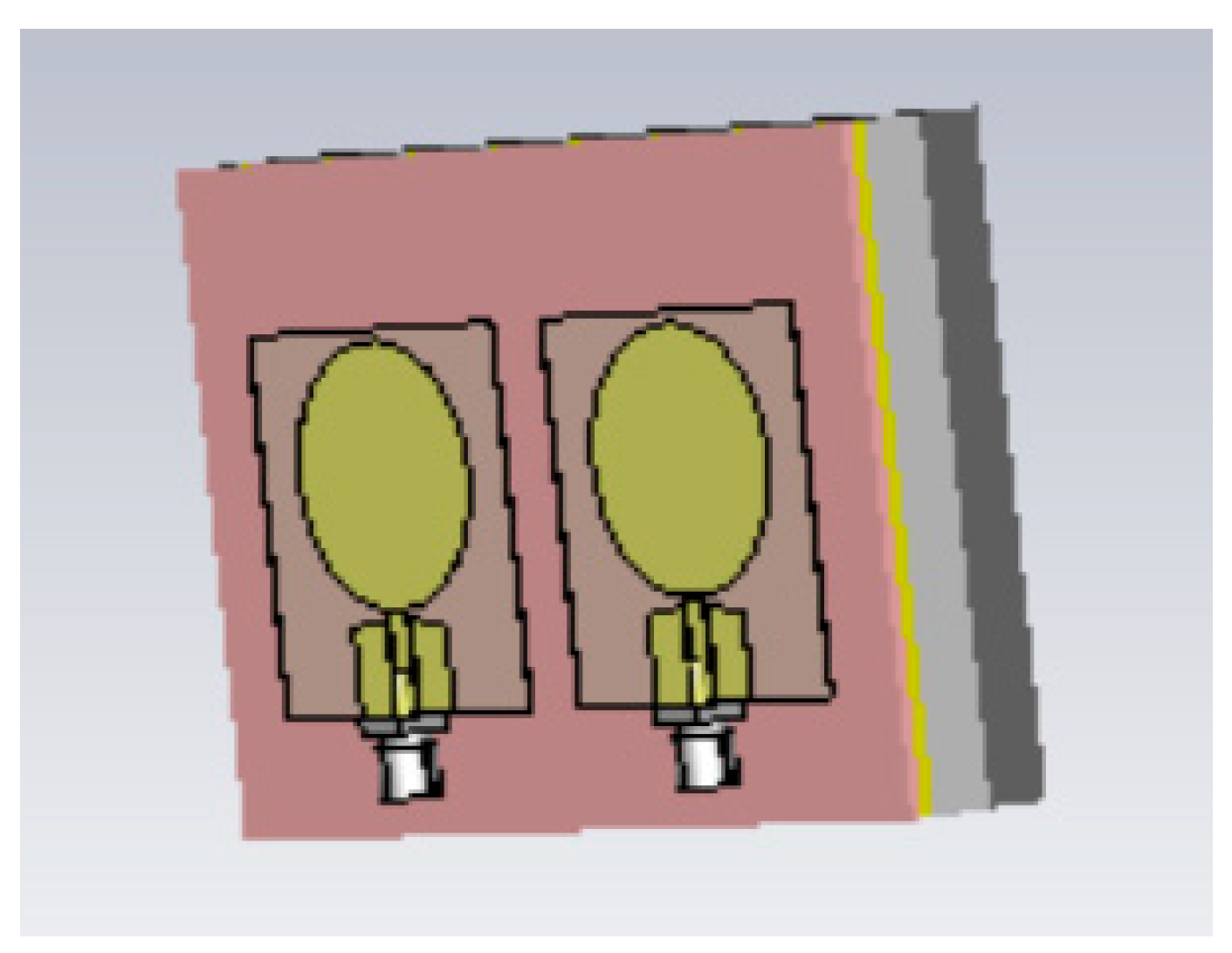

The simulations are conducted using the electromagnetic simulation software Simulia Dassault CST Studio Suite [

55]. Two different layer models are used in the simulations for different phantom verifications Layer Model 1 resembles the head model to verify skin, fat, and brain phantoms, and Layer Model 2 resembles the abdominal area to verify muscle and intestinal phantoms. The Layer Model 1 with on-body antennas is presented in

Figure 3. The thicknesses of the tissue layers in both layer models are presented in

Table 3.

For the simulations, human tissue values are automatically found from CST’s BioModel material library. Those values are used for the reference case simulations. However, in CST, it is possible to edit the tissue properties by changing relative permittivity and loss tangent values manually. Therefore, we first calculate

values for the phantom cases from the measured conductivity values using the formula:

in which

is the conductivity,

with

f the evaluated frequency,

e

-12 is the free space permittivity and

is the real part of the complex permittivity value [

56]. The obtained

values are inserted to CST and simulations are carried out to validate impact of the differences in dielectric properties to S11 and S21 parameters.

Figure 3 illustrated also the on-body antenna used in the simulations. The on-body antenna is an improved version of the flexible UWB antenna designed for wearable health monitoring applications [

57]. It is slighly larger than antenna presented in [

57], with size 40mm x 40 mm x 0.125mm but it has better radiation characteristics in terms of gain towards the body. The implant antenna is same as used in [

61].

2.3. Phantom molds for realistic 3D emulation platforms

In this section, phantom molds as well as procures to develop realistic-shaped phantoms are presented.

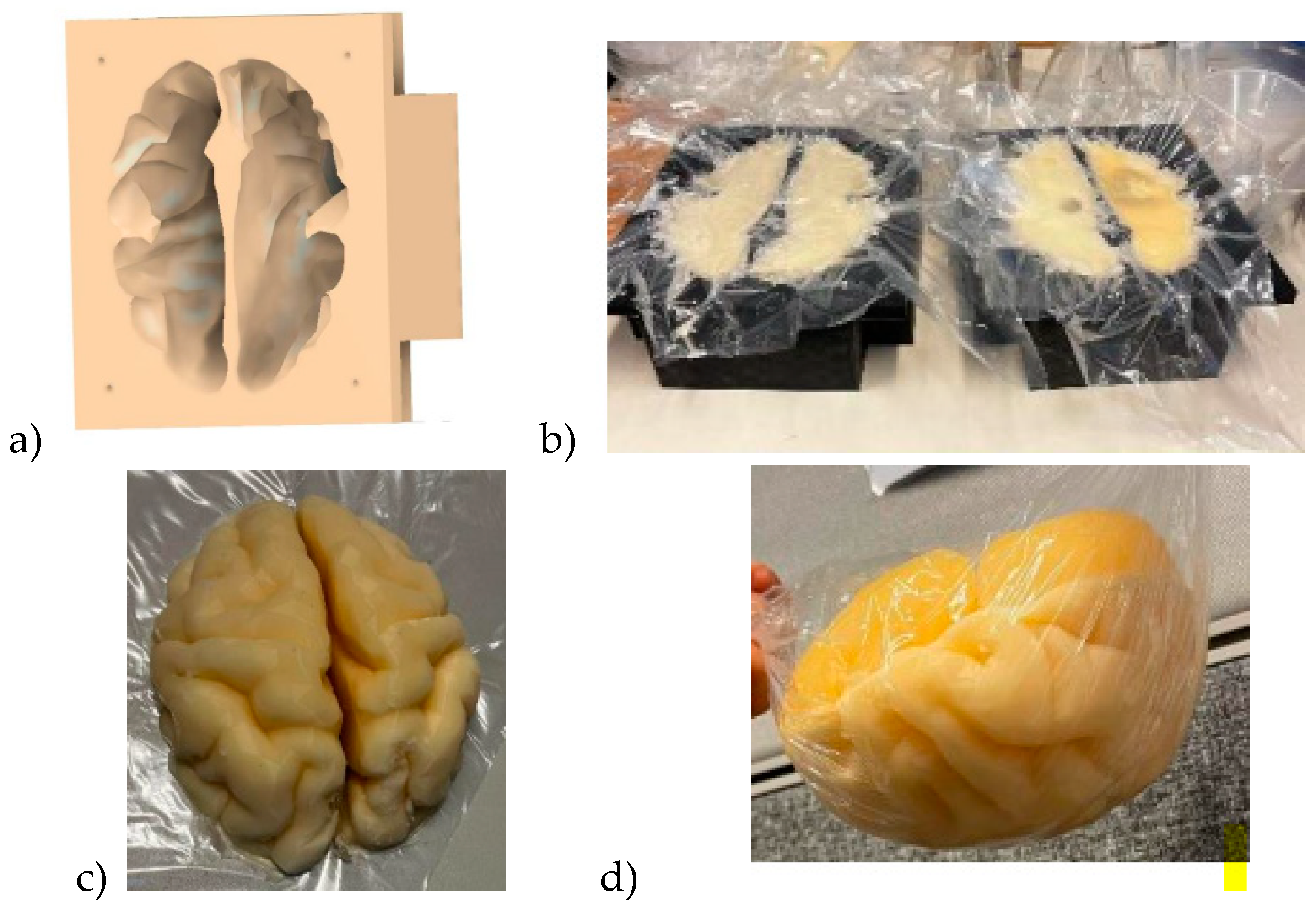

2.3.1. Brain Mold

Brain mold is originally obtained from printable 3D brain mold retrieved from [

58]. The size of the retrieved resembles an average brain but it can be scaled for different sizes. Next, the negation of the 3D model is performed with the Fusion360 program yielding a 3D brain mold model illustrated in

Figure 4a. The mold is divided into two pieces: the upper part and the lower part of the brain. Next, the 3D printing of the molds is carried out with a 3D printer which takes approximately 24 hours for an average-sized brain.

The brain phantom mixture is poured into the molds as shown in

Figure 4b: the lower part and upper parts of the brain phantom in the left and right, respectively. For brain tumor detection studies, the previously made, well-solidified tumor is set inside the brain phantom mixture in before solidification. However, the brain phantom mixture should be cooled before inserting the tumor phantoms to avoid melting the tumor. Approximately 2 days are needed for the brain phantoms to become fully solidified.

Figure 4c presents the solidified upper part of the brain phantom and

Figure 4d is the full brain phantom (from an upside-down view).

For brain tumor detection studies it is essential to produce a reference brain phantom without tumors with an identical brain mold. The tumourous and reference brain phantoms which are identical in size and shape allow realistic and reliable investigations e.g. how tumors change the signal propagation inside the brain tissue.

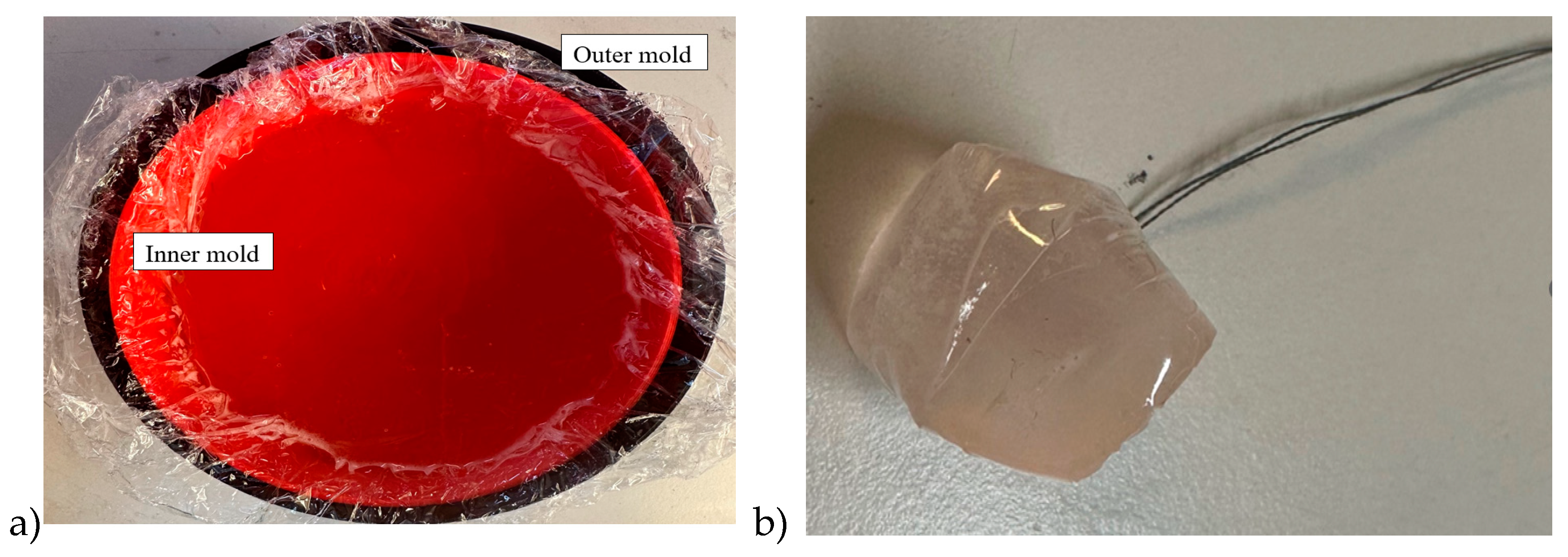

2.3.2. Breast phantoms for breast tumor detection studies

Breast phantom is built separately on skin, fat, glandular, and muscle tissues. In this case, the molds are simpler: fat mold is a simple bowl having diameters of 18 cm and the glandular tissue mold is a smaller bowl depending on the targeted breast density, as shown in

Figure 5a. The glandular tissue mold was placed inside the fat tissue mold before a liquid fat tissue mixture was poured inside the mold for solidification. This way the fat tissue is solidified in the form in which different glandular phantoms (reference and tumor tissues) can be changed easily.

Also, in this case, two glandular tissues were prepared: one with a tumor and another identical-sized without the tumor for the reference case. Tumors having different sizes are prepared with a thread attached, as shown in

Figure 5b, to ease adding the tumor inside glandular tissue in the solidification process (

Figure 5c). Additionally, skin and muscle tissue phantoms are prepared for the final setup. For skin phantom, a simple tray with size 40cm x 40cm covered, with thin plastic, was used as a mold. The muscle tissue is prepared on a smaller plane tray, 20cm x 20cm.

Figure 5d presents the realistic phantom emulation platform used in breast cancer detection studies.

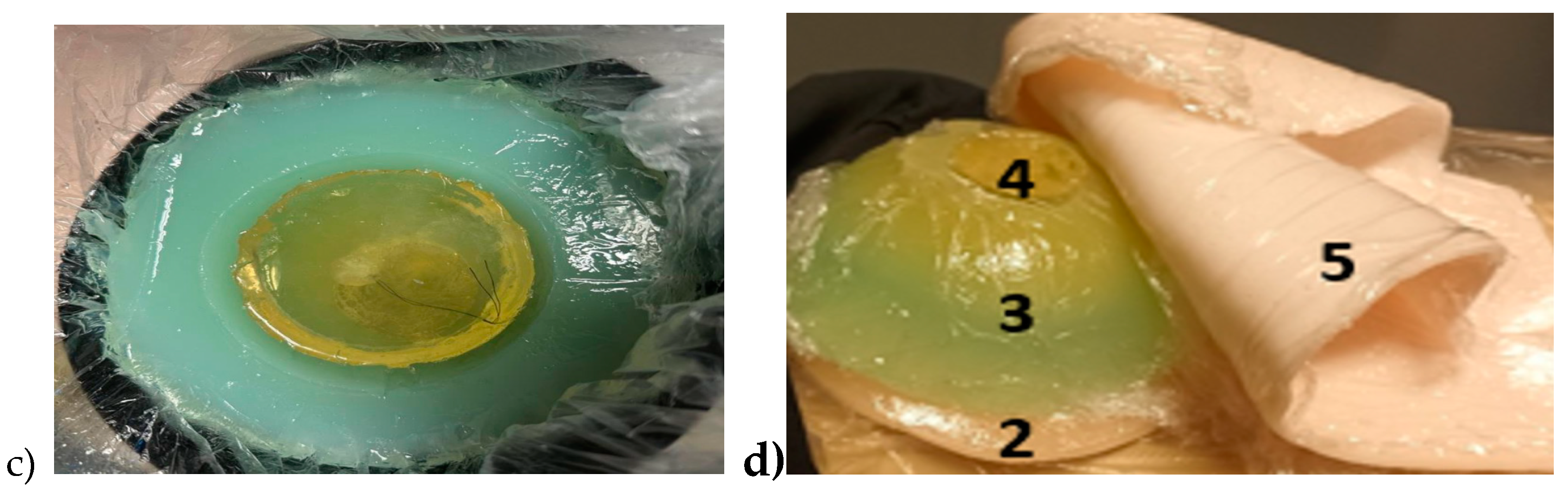

2.3.3. Abdominal molds

A realistic phantom setup for the abdominal area consists of skin, fat, muscle, visceral fat, and intestinal phantom layers. In this scenario, skin, outer fat, and muscle layers are modeled as pure layer models and hence simple trays with varying sizes are used as molds. In this example scenario, the skin thickness is 1.5mm and muscle thickness 15mm. Additionally, liquid propylene glycol is used as a fat phantom as proposed in [

52]. The liquid propylene glycol is poured into a plastic bag which is sealed with heat sealer for the targeted size. With liquid phantom, the fat tissue thickness can be easily adjusted according to the study scenarios, in this example case it is 20mm.

Since the shape of the intestinal area is complex and versatile, the phantoms resembling realistic shaped small and large intestines are developed by formulating molds from plastic using a heat sealer. The thickness of the small intestine plastic mold was 2.5 cm and the colon 4 cm [

59]. The plastic intestine molds were filled with a phantom mixture before solidification. The phantom mixture must be poured carefully to avoid springing off excessive air bubbles. Typically, some bubbles appear especially when pouring the phantom mixture into small intestine molds that are thinner than colon molds, but most of the air bubbles can be removed by carefully transferring the air bubbles to the upper part of the mold and carefully gathering them with a spoon before sealing the mold. Additionally, the air bubbles can also be removed after the sealing by carefully pressing the mold. Next, the molds were formulated in the appropriate form to resemble small and large intestine structures, as shown in

Figure 6a, and were left for solidification for the following day.

The full phantom emulation platform is illustrated in

Figure 6b. This kind of measurement setup is useful, e.g. in the realistic radio channel evaluations for capsule endoscopy since the measurement setup provides the possibility to verify the results obtained in the simulations using anatomical voxel models [

60]. Additionally, this kind of scenario is useful in general in studies relating to the detection of abnormalities in the intestinal region.

3. Results

The Results section is divided into three Subsections: Subsection 3.1 presents evaluations of the impact of the phantoms cooking temperature on dielectric properties of skin and fat phantoms. Subsection 3.2 presents the results for dielectric property measurements for skin, muscle, glandular, brain, and fat tissues. The evolution of recipes is shown by presenting the dielectric properties of different recipe trials. Additionally, the longevity of each recipe is evaluated. Subsection 3.3 presents the results for phantom verification with electromagnetic layer model simulations for different scenarios.

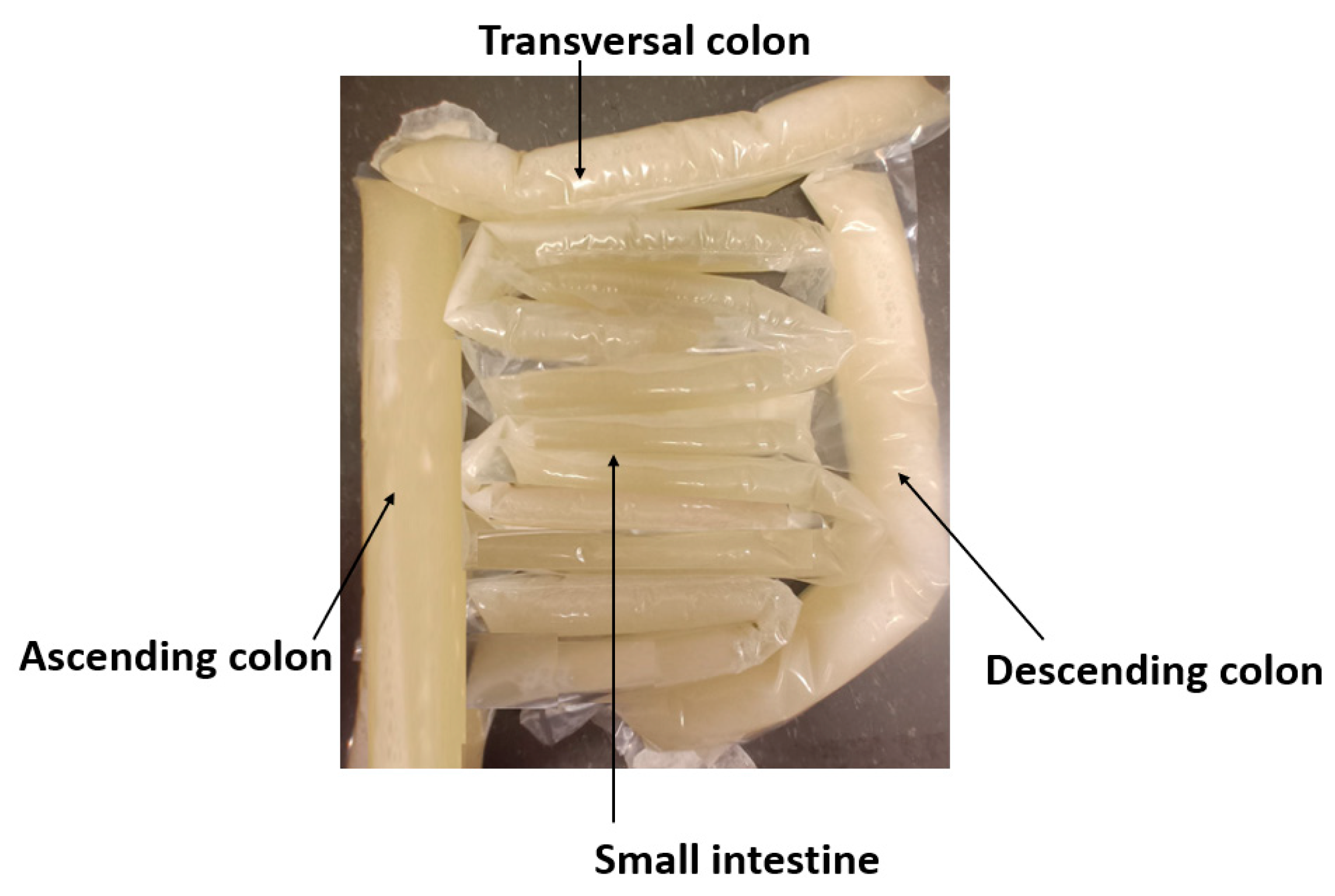

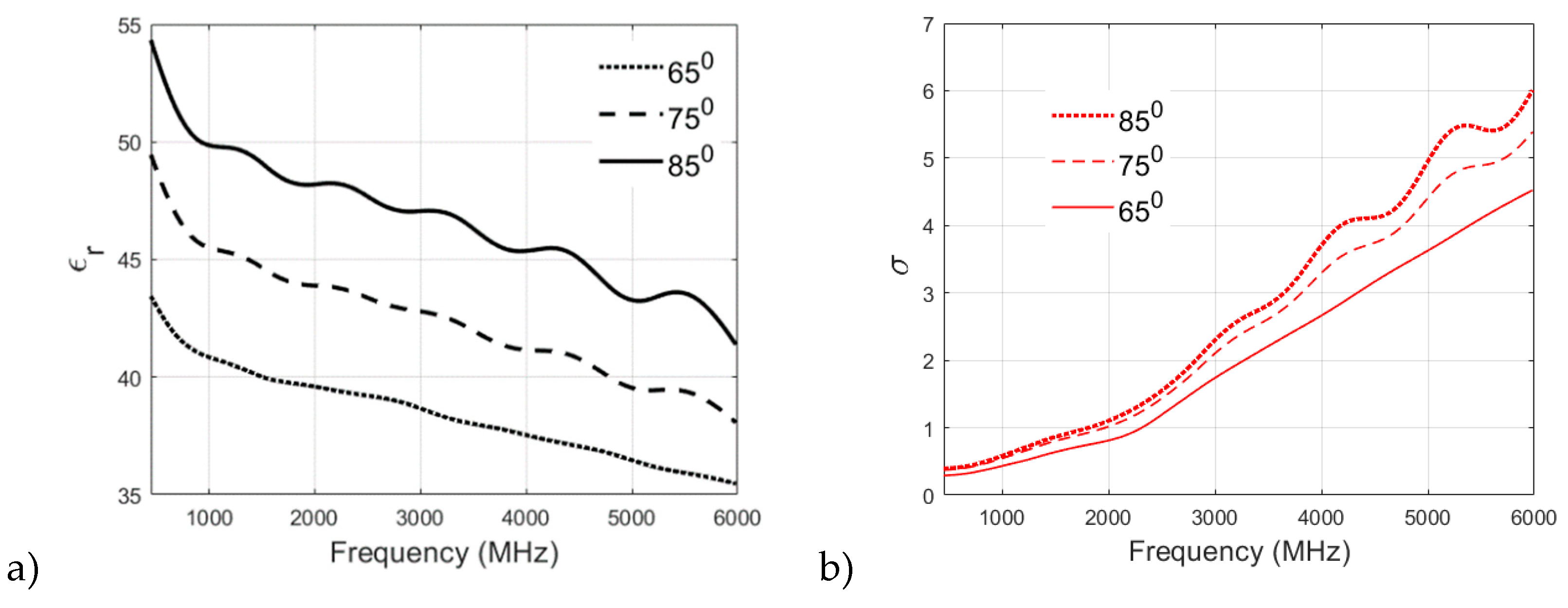

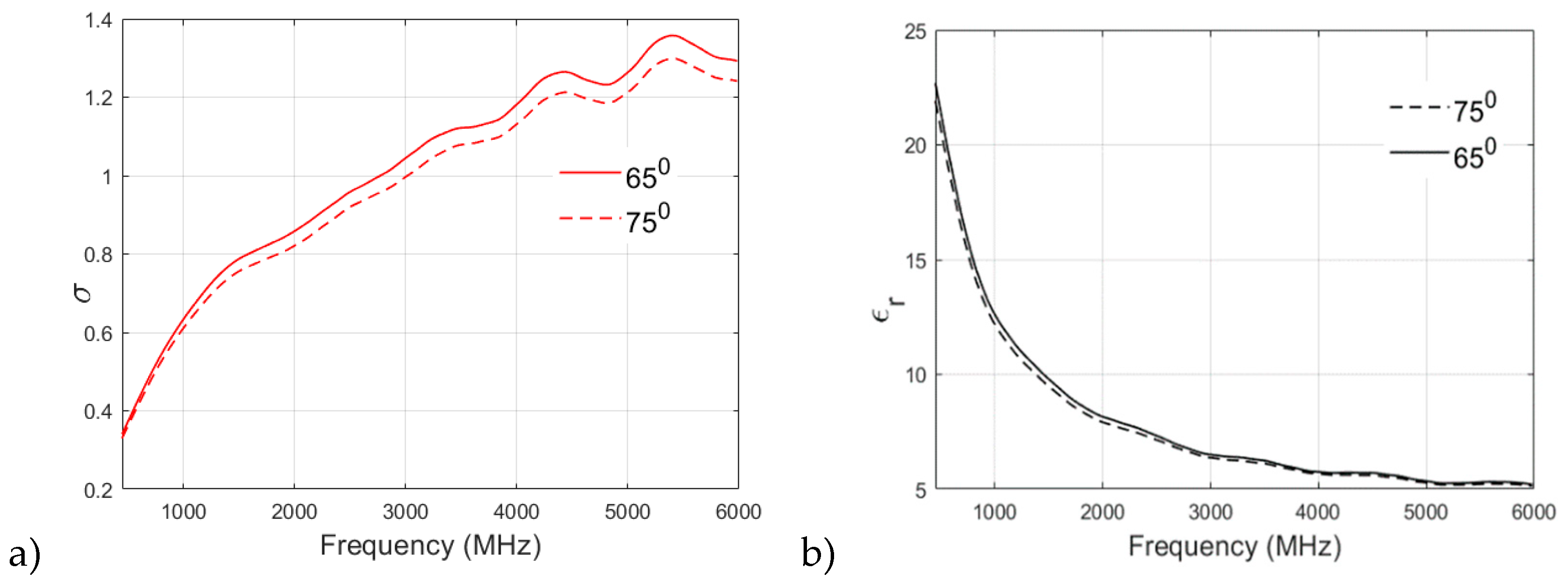

3.1. Effect of Cooking Temperature on Dielectric Properties of Phantom Recipies

The selection of a particular heating temperature in the recipe for the preparation of a phantom is often argued among the research fraternity. Therefore, in this section, different recipes are analyzed to study the effect of cooking temperature on the dielectric properties of the phantom. The muscle, skin, and fat phantom recipes are prepared and analyzed with a cooking temperature of 650, 750, and 850. It is to be noted that the original recipe for Skin Phantom is cooked at 650.

Figure 7a,b showcase the effect of cooking temperature on the relative permittivity and conductivity of skin phantom. The relative permittivity is found to increase clearly with the cooking temperature as it can be visualized from

Figure 7a which plots the permittivity v/s frequency values for the three cooking temperatures for skin phantom. Again, the original recipe cooked at 65

0 shows a smother decrement in permittivity values with increasing frequency as compared to 75

0 and 85

0 recipes which proves the suitability of the proposed recipe for skin phantom.

It can be visualized from

Figure 7b that the conductivity of the skin phantom increases with an increase in observation frequency for all three recipes at 65

0, 75

0, and 85

0 but the phantom recipe cooked at 65

0 shows a smooth and almost linear transition in conductivity values whereas some oscillations are observed in conductivity values of 75

0 and 85

0 recipes.

A similar analysis of the fat phantom recipe cooked at 65

0 and 75

0 is shown in

Figure 8a,b for relative permittivity and conductivity, respectively. From

Figure 8a, an interesting observation can be drawn from the permittivity v/s frequency plot: there is no significant effect of cooking temperature on the relative permittivity of fat phantom and both recipes show negligible difference in permitivity values at higher frequency bands. From

Figure 8b it is found that both of the recipes have similar conductivity values at lower frequencies. For example, at 500 MHz, the conductivity value observed for the 65

0 sample is 0.3608, whereas the 75

0 sample is 0.3497. However, there is a clear distinction between conductivity values at the higher frequency band (>2 GHz). In the case of fat phantom, cooking temperature 85

0 was not possiblesince the mixture become too grainy.

3.2. Evaluation of dielectric properties of phantoms

The phantoms were developed by attempting several different trials whose dielectric properties, i.e. relative permittivity and conductivity were measured at different frequencies. Additionally, longevity of the phantoms were evaluated with measuring the dielectric properties of the samples after 5h, 24h, 1 week and 10 days.

3.1.1. Measurement Analysis and Summary for Skin and Tumor Phantoms

The skin and tumor phantoms were successfully prepared using the aforementioned procedure. Through a series of trials and adjustments in ingredient concentrations, optimal compositions were identified for both skin and tumor phantoms as shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Several trials were conducted to create tumor phantoms that closely imitate real tumor tissue. The initial trial, TS1, consisted of distilled water, gelatine, sunflower oil, and dishwashing liquid. However, the relative permittivity values for TS1 were significantly lower than those of real tumor tissue, indicating the need for further adjustments. Additionally, the mixture had an excessively oily and liquid consistency, failing to solidify properly.

Subsequent trials, like TS2, attempted to address the issue by reducing the water content to promote solidification. However, the mixture remained excessively oily. Although TS2 showed a decrease in relative permittivity compared to TS1, it didn't resolve the consistency problem.

To improve the mixture, trials TS3 to TS8 were conducted. These trials involved reducing the amount of oil and slightly decreasing the gelatine while increasing the water content in each trial. These adjustments led to a progressive increase in relative permittivity values. Notably, TS7, which contained 20.3 ml of distilled water, exhibited relative permittivity and conductivity values that closely resembled those of real tumor tissue. Moreover, TS7 successfully achieved the desired solid consistency.

Based on the findings from the tumor-phantom trials, the optimal composition was determined to be 20.3 ml of distilled water, 1.63 g of gelatine, 1.1 ml of sunflower oil, and 0.9 ml of dishwashing liquid. This specific combination closely replicated the dielectric and mechanical properties of actual tumor tissue.

Similarly, for the skin phantoms various trials were conducted as seen in Error! Reference source not found., and the optimal composition was found to be 10 ml distilled water, 3.01 g gelatin, 1.68 ml sunflower oil, and 0.83 ml dishwashing liquid. The prepared skin and tumor phantoms were measured at different time intervals at 2.5G Hz and 6 GHz, and it was observed that they remained stable and reliable for a duration of up to one week as depicted in Error! Reference source not found.. This durability allows for extended experimentation and analysis without significant changes in their dielectric properties.

In conclusion, the developed skin and tumor phantoms provide valuable tools for investigating microwave characteristics in skin and tumor tissues. Their composition closely mimics the properties of their respective tissues, enabling accurate and controlled experiments. These phantoms offer promising opportunities for further research in the field of microwave applications and hold the potential to advance our understanding of various biomedical phenomena.

3.2.2. Glandular Phantom Preparation and Longevity

The glandular phantom is prepared by heating deionized water to 65°C on a magnetic hot-plate stirrer. Gradually, gelatine was added and stirred continuously until fully dissolved, resulting in a clear solution. Sugar was then added to the mixture, which was continually stirred. The heat was turned off, and the temperature was allowed to cool to approximately 50°C while maintaining constant stirring. The mixture was then poured into a mold for polymerization. Afterward, the phantoms were refrigerated for 3.5 hours and allowed to rest at room temperature for one hour before use. To assess the longevity of the glandular phantoms, their stability was monitored over time. The results revealed that these phantoms maintain their properties for up to 10 days as depicted in VI, demonstrating their durability and suitability for extended research studies. This prolonged duration ensures consistent and reliable simulations of glandular tissue, providing researchers with ample time to conduct multiple experiments without compromising the integrity of the phantoms.

In conclusion, the carefully prepared glandular phantoms offer a robust and realistic solution for simulating glandular tissue. With their extended longevity and stable properties, these phantoms serve as invaluable tools for various research investigations, enabling accurate and consistent outcomes in the study of glandular tissue.

4.1.3. Muscle Phantom Preparation and Longevity

The fabrication process for the muscle phantom involved the creation of a saline solution using NaCl in distilled water, which was heated to approximately 65°C on a magnetic hot plate stirrer. Gelatin was gradually added to the heated solution while stirring continuously, ensuring complete dissolution and clarity of the mixture. To enhance the homogeneity of the phantom, dishwashing liquid, and sunflower oil were introduced to the saline-gelatin solution once it became clear. After stirring for approximately 5 minutes, the heat was turned off, and the mixture was poured into a mold and refrigerated for about 3 hours until it solidified.

The resulting muscle phantom closely emulates the electrical properties and composition of muscle tissue, making it a valuable tool for research and experimentation. It provides a realistic model for studying the behavior of muscle tissue under various conditions and can be utilized in the development and testing of medical devices and imaging techniques.

It is important to note that the stability and longevity of the muscle phantom are crucial considerations. Based on evaluations, it has been determined from

Table 6, that the muscle phantom remains suitable for use for approximately 7 days. This time frame ensures that the phantom maintains its desired characteristics and can reliably simulate muscle tissue throughout experimental procedures.

To preserve the stability of the muscle phantom, appropriate storage conditions, such as refrigeration, should be maintained. Regular assessments and measurements should be conducted to monitor any potential alterations in the phantom's properties over time.

By following the outlined fabrication process and taking into account the stability of the muscle phantom, researchers can confidently utilize this phantom to investigate and gain insights into the behavior and characteristics of muscle tissue in their research endeavors.

3.1.4. Fat phantom

Fat phantom, its evolution with different trials, and its longevity are studied in detail in [

52] and thus this paper only summarizes the values of the best recipe in

Table 7. In [

52] it was emphasized that the final trial (trial 14) had the most realistic dielectric properties but the physical characteristics of the phantom were not sufficiently solid to be used in 3D molds.

3.2. Verification of the final phantom recipes with EM simulations

In [

52], we proposed a novel idea for validating the feasibility and reliability of the developed phantoms for practical scenarios with tissue layer model simulations. In the simulations, the antenna reflection coefficient, i.e. S11 parameter, is calculated with tissue layer models consisting of tissue layers whose dielectric properties are the same as those measured with the phantoms. For the reference simulations, the dielectric properties are the same as with ideal human tissue [

54]. The aim is to see how much small differences in the dielectric properties of the phantom and ideal case affect the simulated antenna reflection coefficients. The results will provide insight into how close the phantom-based antenna performance evaluations are to the realistic case.

In this section, each phantom is first evaluated individually by changing the dielectric properties of each tissue: skin, brain, muscle, fat, and small intestine separately (subsection 4.2.1-4.2.5). Skin and brain phantom evaluations are carried out with LM1 (resembling head tissue) and an on-body antenna setup. Muscle, fat, and SI phantoms are evaluated with LM2 (resembling abdominal tissues) and on-body implant antenna -setup. In each case, the results are compared with the reference case. Finally, the whole LM2 phantom setup is evaluated by changing the dielectric properties of each tissue layer to those obtained with the developed phantoms and compared with reference LM2 (subsection 4.2.6).

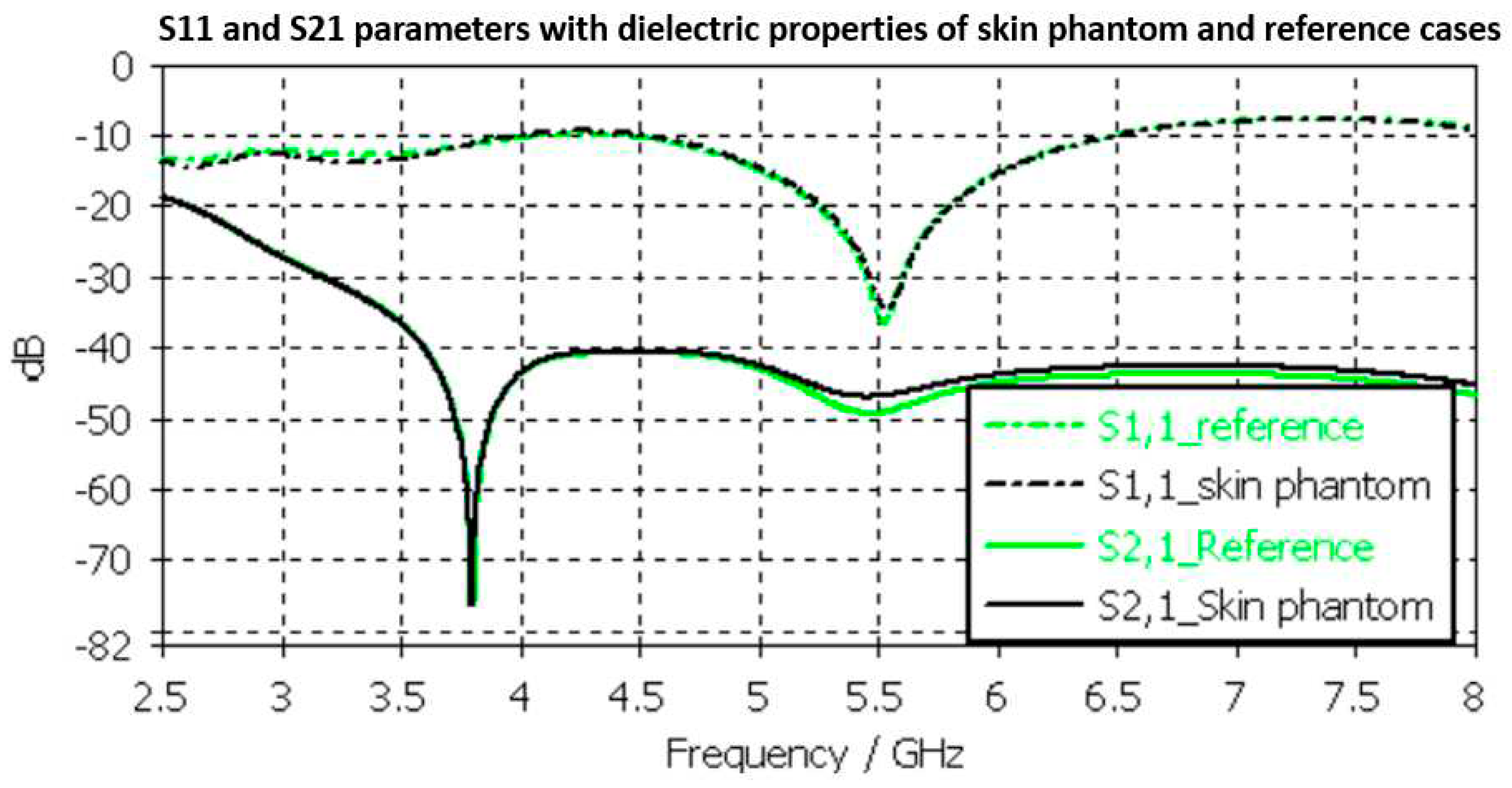

3.2.1. Skin Phantom Verification

Skin phantom evaluations are carried out with Layer Model 1 with two flexible on-body antennas. In this case, only the dielectric properties of the skin are changed while the dielectric properties of the other tissues are kept as reference case retrieved from [

54].

Evaluated S11 andS21 results shown for the reference case and skin phantom case in

Figure 9. As it can be seen, the difference between the skin phantom and reference cases is negligible within most of the simulated frequency band: the maximum differences can be found at 5.5 GHz, 1.4 dB for S11 and 2 dB for S21 results.

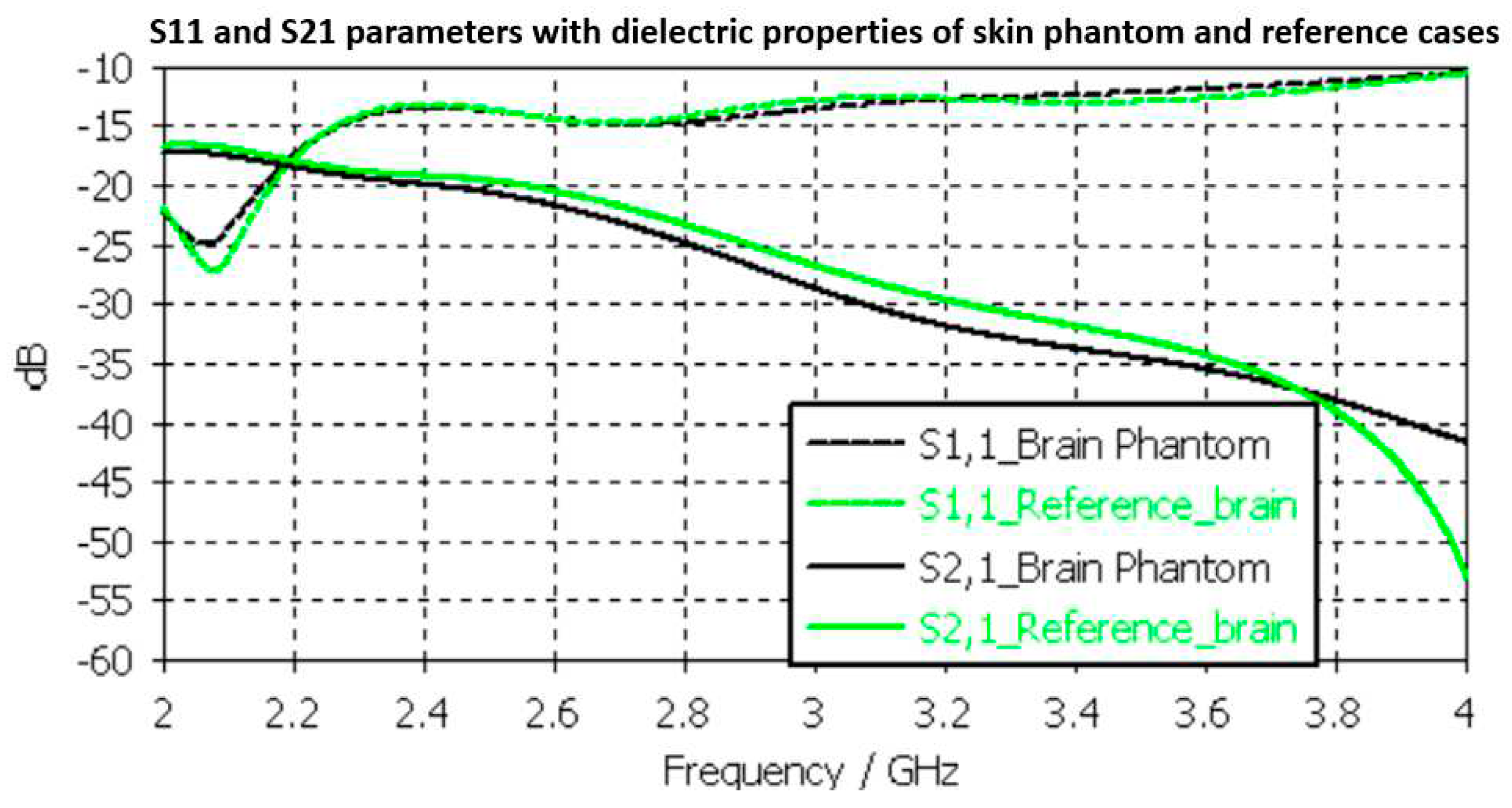

3.2.2. Brain phantom verification

Next, the brain phantom is evaluated using Layer Model 1 and flexible antennas. In this case, only the dielectric properties of the brain are changed and the dielectric properties of the other tissues are kept as reference cases retrieved from [

54]. The results are presented in

Figure 10. In the case of brain phantoms, the differences in S11 results are somewhat similar to skin phantom S11 results; maximum 2dB difference and it occurs at 2.1 GHz. Instead, there are clearer differences in S21 results especially at 2.8-3.6GHz and at 4GHz. The maximum differences in these ranges are 2dB and 10dB. However, S21 analysis for frequency ranges above 4 GHz is seldom used due to high propagation loss, and thus this phantom recipe can be considered suitable for different applications.

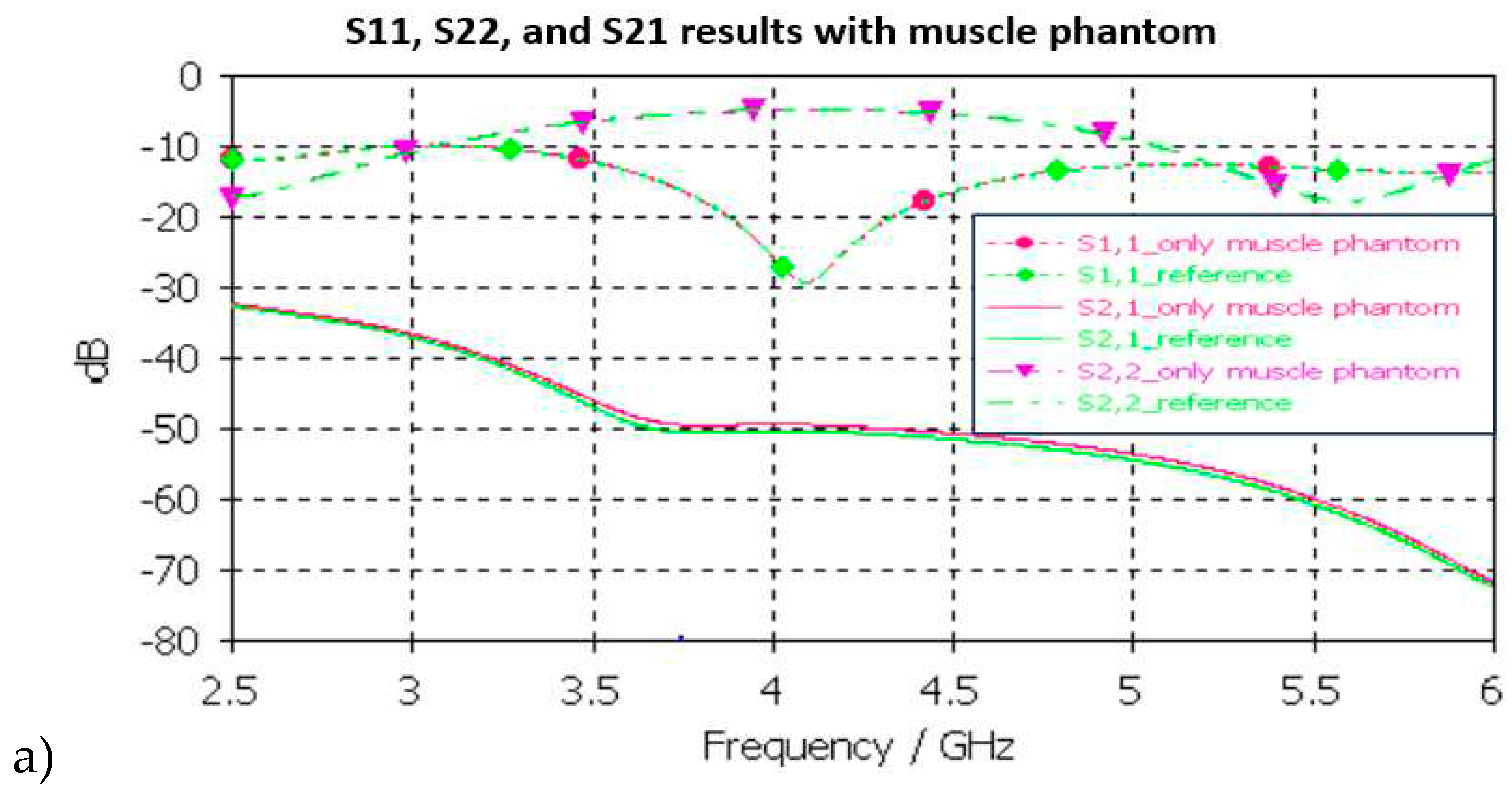

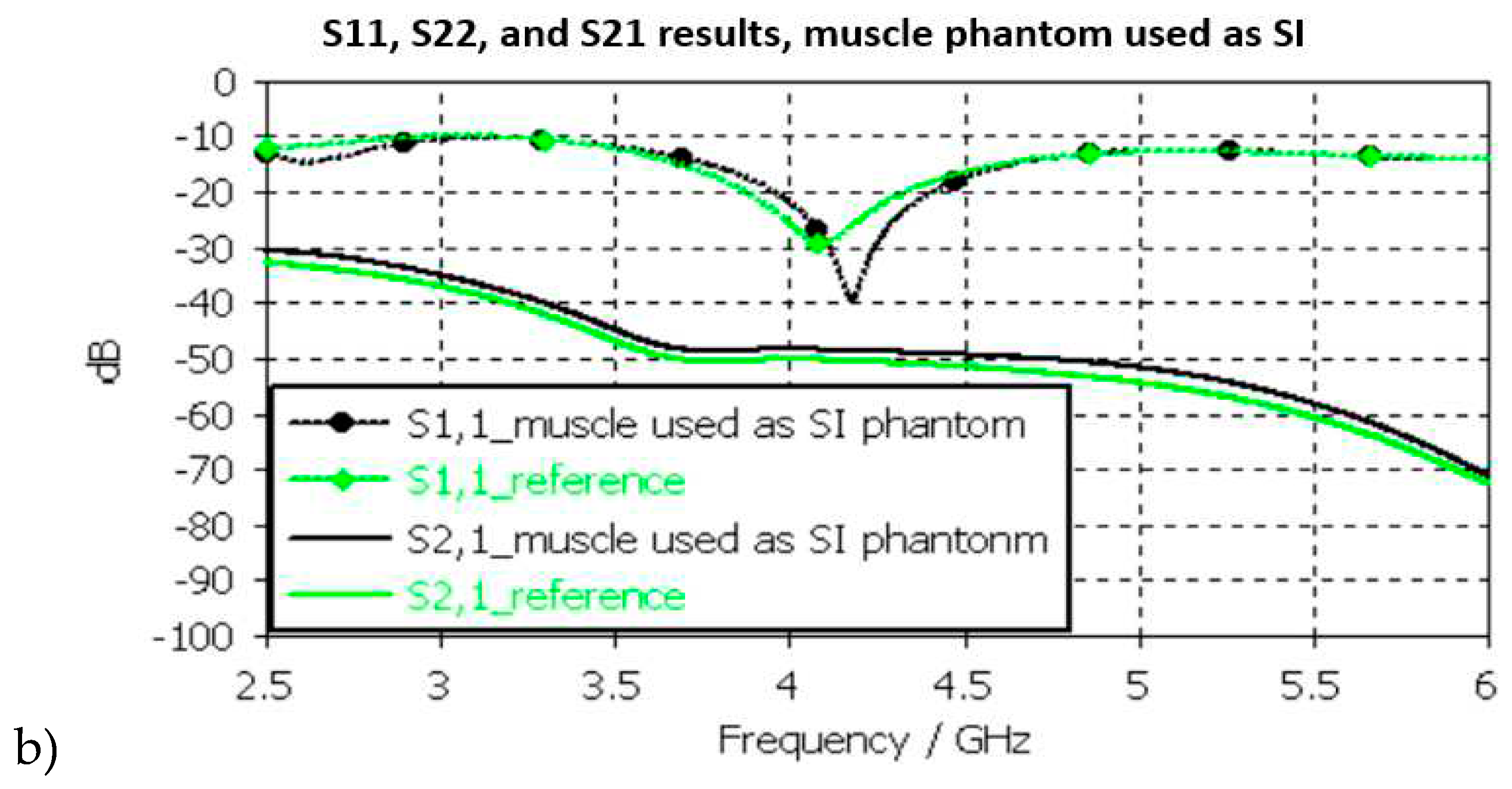

3.2.3. Muscle and Intestinal Phantom Verification

Next, the muscle phantom is verified with layer model 2 which resembles abdominal tissue layers. In this case, the dielectric properties of the developed muscle phantom are used both in the muscle and intestinal layers as commonly concluded in the literature [

5]. The channel is evaluated between the implant and on-body flexible antennas. The evaluations are carried out separately only for muscle layer evaluations and small intestine layer evaluations, as presented in

Figure 11a,b, respectively

In muscle layer evaluation shown in

Figure 11a, changes between the S11, S22, and S21 results in reference and phantom cases are negligible in muscle layer evaluations. The maximum difference is only 1.5 dB which is observed in S21 results at 5-6GHz. Besides of insignificant difference, commonly considered frequency ranges for implant (ingestible) communications and sensing are at ISM band 2.5GHz, the first part of the UWB band 3.1-4.1 GHz, and 3.75-4.25GHz [

60,

61,

62].

In SI layer evaluations, presented in

Figure 11b, the differences between the reference and phantom cases are small except in S11 (implant antenna reflection coefficient) at around 4.2GHz, in which the difference is even 13dB. This is due to the fact that the small intestine and muscle layer have small differences in their dielectric properties as shown in

Table 2 Nevertheless, the differences in S21 results are a relatively small, maximum of 2dB at 5GHz.

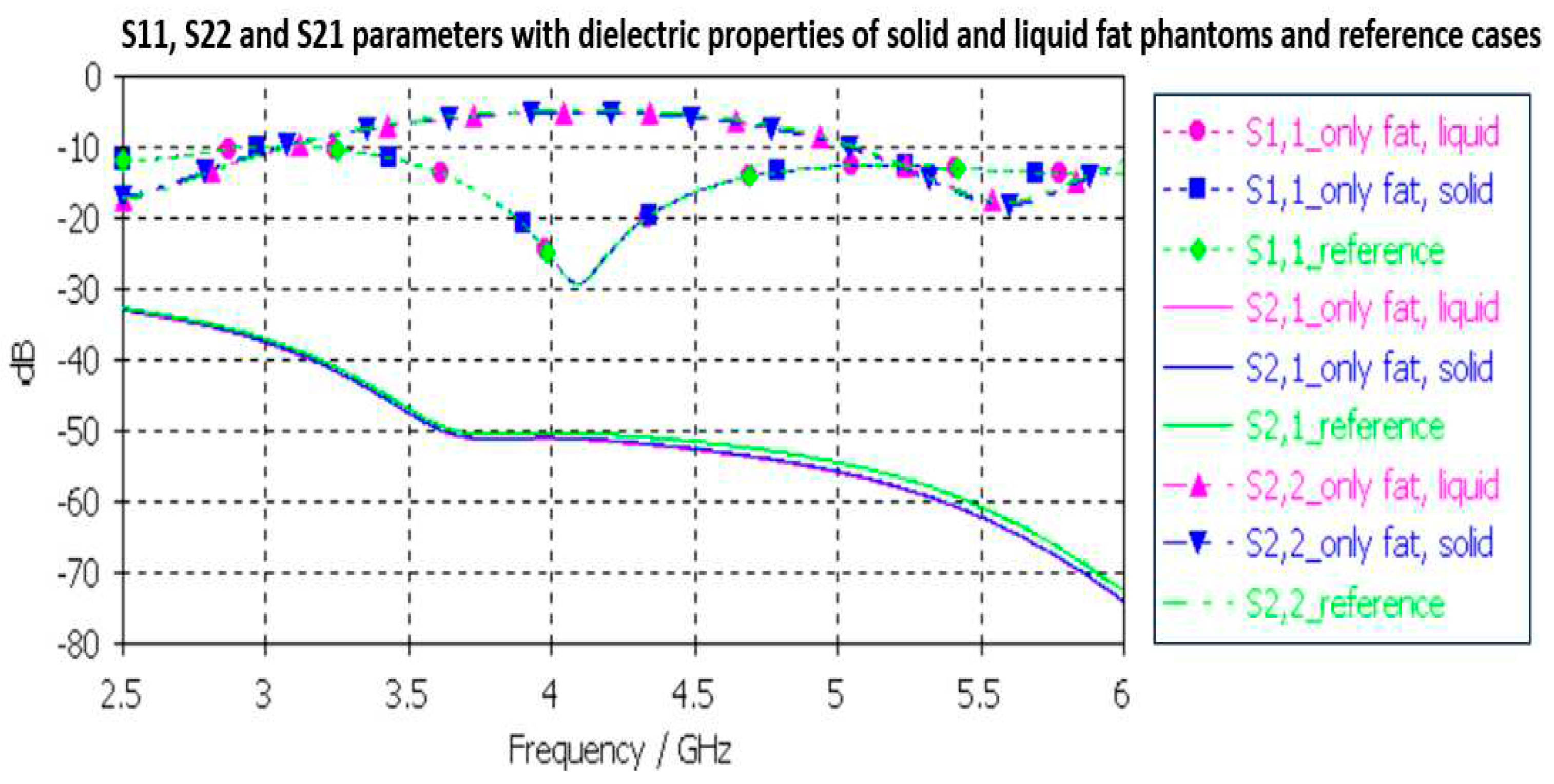

3.2.4. Fat phantom verification

Finally, the fat phantom is evaluated with Layer model 2 and with a flexible on-body antenna and the capsule antenna using dielectric properties of a fat phantom, both with liquid and solid fat phantoms. The results are shown in

Figure 12. As it can be seen, the differences between the liquid and solid phantoms are minor compared to the reference case: the maximum difference is 2dB at 5.5GHz.

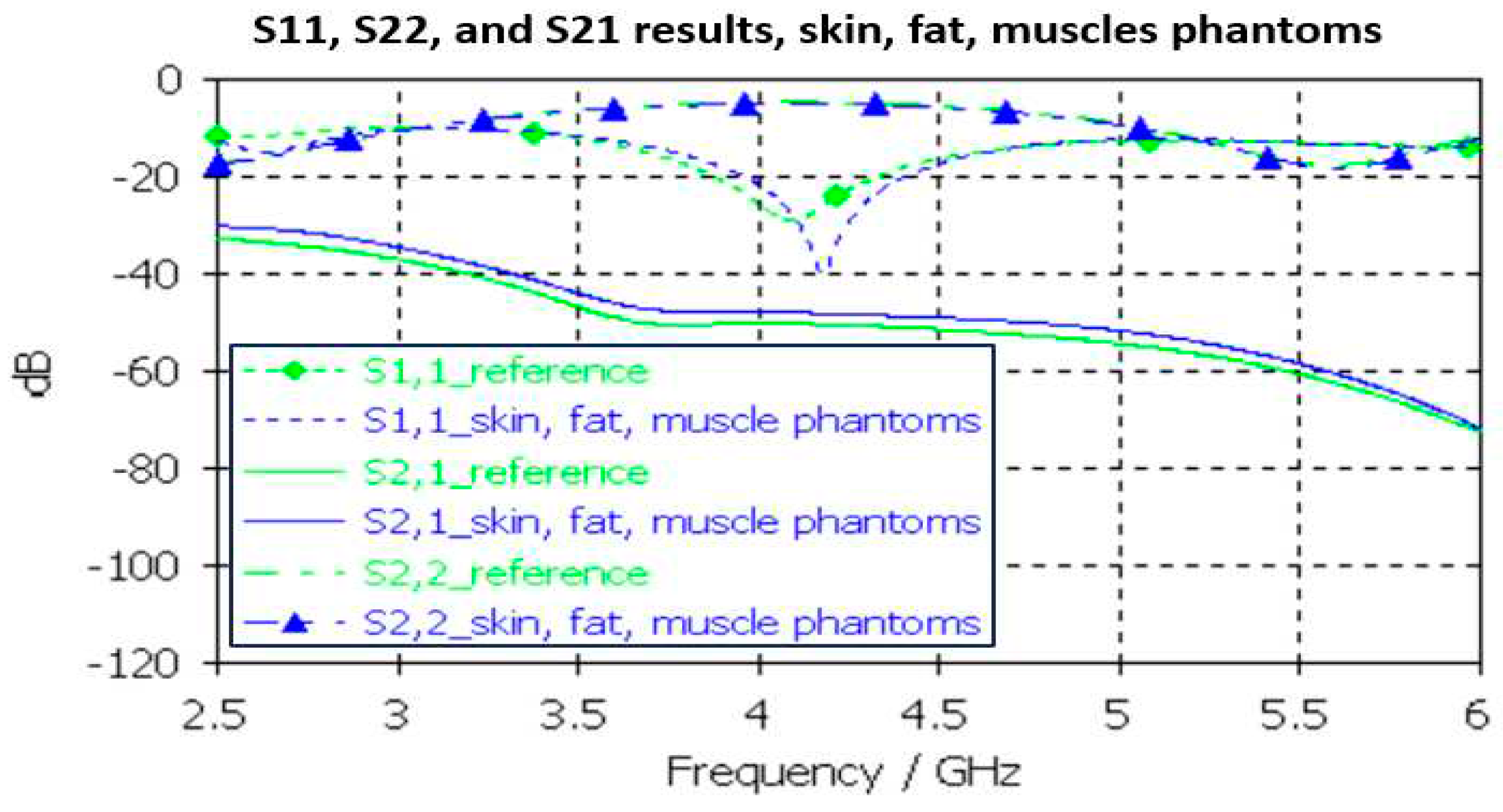

3.2.4. Full abdominal phantom layer model verification

Finally, the full abdominal layer model is evaluated when using skin, fat and muscle phantoms. Muscle phantoms is used also in small intestine layer. The results are presented in Figure 15. As it can be seen, the results are similar as presented with SI-evaluations in Figure 15, just minor changes in S21 results. To obtain even better accuracy, the muscle phantom could be further developed to resemble small intestine by increasing the amount of water and salt slightly to increase permittivity and conductivity, respectively.

The differences between the S11, S22, and S21 parameters obtained with the simulations conducted using dielectric properties of the phantoms and reference cases for each tissues are shown in

Table 2 at frequencies 2.5 and 6 GHz. Additionally, the maximum difference at the corresponding frequency is included. As it can be seen, although there are differences in the dielectric properties of the developed phantoms and real human tissues, the differences in practical scenarios is not so significant. Therefore, it can be concluded that the presented phantoms are valid both for on-body and in-body sensing/communications applications.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in the tissue phantom verifications show that although there might be some differences in the measured dielectric properties of the developed phantoms respect to the those of real human tissues, the differences in S11 and S21 simulation results are not so significant. Especially in the frequency ranges targeted for medical applications, such as ISM band 2.5GHz and UWB band, the differences are minor. Therefore, it can be concluded that the presented phantoms are valid both for on-body and in-body sensing/communications applications.

The evaluations on the impact of the phantom cooking temperature validate the importance of carefulness with temperature during the phantom cooking process. Depending on the phantom, differences in the dielectric properties may change remarkably if the temperature increases excessively. With skin phantom, the increase was maximum 13 units in relative permittivity and 1.5 in conductivity. The changes in realtive permittivity are larger are somewhat similar within the whole measured bandwidth. Instead with conductivity, the changes are minor at lower frequencies than at higher frequencies. This result is a new interesting and useful for phantom development. Besides of emphasizing the carefulness in phantom preparation process, it also enables use of same recipe for different tissue phantoms if different cooking temperature is used. Interestingly, with fat phantom, the changes due to cooking temperature are clearly minor. As a future work, the authors will study the impact of temperature with other phantom recipes as well.

In general, the results presented in this paper provide several new insights on microwave sensing field. New phantom recipes and new innovative approaches to prepare realistic 3D phantoms for validation of several emerging medical monitoring applications. As a future work, we will present comprehensive evaluations for several monitoring applications using the proposed realistic platforms.

New phantom recipes and new innovative approaches to prepare realistic 3D phantoms facilitate in its part the introduction and validation of several novel medical monitoring applications utilizing microwave technique. These novel 3D phantoms can be considered as part of the development of digital twins for healthcare applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S, D. S, R. D, C. H, S. M, and T. M.; methodology, M.S. S.M, T. M; software, M. S.; validation, M.S, R. D, D. S, C. H, S. M.; formal analysis, M. S, D. S, R. D, and C- H; investigation, M.S, D. S, R. D, C. H, S. M, T. M .; resources, T. M, S. M.; data curation, M. S, D. S, R. D; writing—original draft preparation, M. S, R. D, and D. S.; writing—review and editing, M.S, D. S, R. D, C. H, S. M, and T. M.; visualization, M.S, D. S, R. D, C. H, S. M.; supervision, T. M.; project administration, T. M. M. S; funding acquisition, T. M. and M.S All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Academy of Finland Profi6 funding, 6G-Enabling Sustainable Society (University of Oulu, Finland), and by European Structural and Investment Funds - European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), EMUVALID, which are greatly acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data is shared in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lukasz Surazynski for his help with 3d Printing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Neira, L.M.; Mays, R.O.; Hagness, S.C. Human Breast Phantoms: Test Beds for the Development of Microwave Diagnostic and Therapeutic Technologies. IEEE Pulse 2017, 8, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, S.; Cioffi, V.; Qureshi, A.M.; Borgia, A. Gel-Like Human Mimicking Phantoms: Realization Procedure, Dielectric Characterization and Experimental Validations on Microwave Wearable Body Sensors. Biosensors 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, J.; Fear, E. Stable and Flexible Materials to Mimic the Dielectric Properties of Human Soft Tissues. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2014, 13, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló-Palacios, S.; Garcia-Pardo, C.; Fornes-Leal, A.; Cardona, N.; VallésLluch, A. Tailor-Made Tissue Phantoms Based on Acetonitrile Solutions for Microwave Applications up to 18 GHz. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2016, 64, 3987–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollacco, D.A.; Conti, M.C.; Farrugia, L.; Wismayer, P.S.; Farina, L.; Sammut, C.V. Dielectric properties of muscle and adipose tissue-mimicking solutions for microwave medical imaging applications. Phys. Med. Biol. 2019, 64, 095009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Meo, S.; Pasotti, L.; Iliopoulos, I.; Pasian, M.; Ettorre, M.; Zhadobov, M.; Matrone, G. Tissue-mimicking materials for breast phantoms up to 50 GHz. Phys. Med. Biol. 2019, 64, 055006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazebnik, M.; Madsen, E.L.; Frank, G.R.; Hagness, S.C. Tissue mimicking phantom materials for narrowband and ultrawideband microwave applications. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005, 50, 4245–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, E.; Fakhoury, J.; Oprisor, R.; Coates, M.; Popović, M. Improved tissue phantoms for experimental validation of microwave breast cancer detection. In Proceedings of the Fourth European Conference on Antennas and Propagation. Barcelona, Spain; 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Martellosio, A. , et al. (2017). Dielectric Properties Characterization From 0.5 to 50 GHz of Breast Cancer Tissues. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, 65, pp. 998–1011.

- Meo, S.D. , et al. (2019). Tissue mimicking materials for breast phantoms using waste oil hardeners. In 2019 13th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Krakow, Poland, pp. 1–4.

- Khaleghi, A. Hasanvand and I. Balasingham, Radio Frequency Backscatter Communication for High Data Rate Deep Implants. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2019, 67, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzai, D.; Katsu, K.; Chavez-Santiago, R.; Wang, Q.; Plettemeier, D.; Wang, J.; Balasingham, I. Experimental Evaluation of Implant UWB-IR Transmission With Living Animal for Body Area Networks. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2014, 62, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, P.; Khaleghi, A.; Mahmood, S.; Albatat, M.; Bergsland, J.; Balasingham, I. Evaluation of Data Telemetry for Future Leadless Cardiac Pacemaker. IEEE Access 2014, 7, 157933–157945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Särestöniemi, M.; Pomalaza-Raez, C.; Kissi, C.; Iinatti, J. On the UWB in-body propagation measurements using pork meat. International conference of BodyNets 2020.

- Särestöniemi, M.; Myllymäki, S.; Reponen, J.; Myllylä, T. Remote diagnostics and monitoring using microwave technique – improving healthcare in rural areas and in exceptional situations. Finnish Journal of eHealth and eWelfare (FinJeHeW) April 2023.

- Chandra, R.; Zhou, H.; Balasingham, I.; Narayanan, R.M. On the Opportunities and Challenges in Microwave Medical Sensing and Imaging. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 1667–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldhaeebi, M.A.; Alzoubi, K.; Almoneef, T.S.; Bamatraf, S.M.; Attia, H.; Ramahi, O.M. Review of Microwaves Techniques for Breast Cancer Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalitha, K.; Manjula, J. Non-invasive microwave head imaging to detect tumors and to estimate their size and location. Phys. Med. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, A.; Augello, E.; Battistini, G.; Benassi, F.; Masotti, D.; Paolini, G. Microwave Devices for Wearable Sensors and IoT. Sensors 2023, 23, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Duarte, D.O.; Origlia, C.; Vasquez JA, T.; Scapaticci, R.; Crocco, L.; Vipiana, F. Experimental Assessment of Real-Time Brain Stroke Monitoring via a Microwave Imaging Scanner. IEEE Open J. Antennas Propag. 2022, 3, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Islam, M.T.; Hoque, A.; Rahim, S.K.A.; Alshammari, A.S.; Chowdhury, M.E.; Soliman, M.S. Sensor-based microwave brain imaging system (SMBIS): An experimental six-layered tissue based human head phantom model for brain tumor diagnosis using electromagnetic signals. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2023, 45, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.T.; Hoque, A.; Amin, N.; Chowdhury, M.E. A portable electromagnetic head imaging system using metamaterial loaded compact directional 3D antenna. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 50893–50906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadima, O.; Rahman, M.; Sotiriou, I.; Ghavami, N.; Lu, P.; Ahsan, S.; Kosmas, P. Experimental validation of microwave tomography with the DBIM-TwIST algorithm for brain stroke detection and classification. Sensors 2020, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.J.; Abbosh, M. Realistic head phantom to test microwave systems for brain imaging. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2014, 56, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.J.; Abbosh, A.M.; Mustafa, S.; Ireland, D. Microwave system for head imaging. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2013, 63, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Teimouri, J.; Shirazi, A.; Geraily, G.; Esfahani, M.; Shafaei, M. Construction of heterogeneous head phantom for quality control in stereotactic radiosurgery. Med. Phys. 2017, 44, 5070–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joachimowicz, N.; Duchêne, B.; Conessa, C.; Meyer, O. Anthropomorphic breast and head phantoms for microwave imaging. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorny, T.; Vrba, D.; Tesarik, J.; Rodrigues, D.B.; Vrba, J. Anatomically and dielectrically realistic 2.5 D 5-layer reconfigurable head phantom for testing microwave stroke detection and classification. Internat. J. Antenn. Propag. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobashsher, A.; Abbosh, A. Three-dimensional human head phantom with realistic electrical properties and anatomy. IEEE Antenn. Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2014, 13, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Mohammed, B.; Abbosh, A. Novel preprocessing techniques for accurate microwave imaging of human brain. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2013, 12, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.; Lau, R.; Gabriel, C. The dielectric properties of biological tissues: III. Parametric models for the dielectric spectrum of tissues. Phys. Med. Biol. 1996, 41, 2271–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jofre, L.; Hawley, M.; Broquetas, A.; Reyes, E.d.L.; Ferrando, M.; Elias-Fuste, A. Medical imaging with a microwave tomographic scanner. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1990, 37, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karathanasis, K.T.; Gouzouasis, I.A.; Karanasiou, I.S.; Stratakos, G.; Uzunoglu, N.K. Passive focused monitoring and non-invasive irradiation of head tissue phantoms at microwave frequencies. In 2008 8th IEEE International Conference on BioInformatics and BioEngineering, pp. 1–6. IEEE, 2008.

- Looi, Chun Keat, and Zhi Ning Chen. Design of a human-head-equivalent phantom for ISM 2.4-GHz applications. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2005, 47, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.; Abbosh, A.; Henin, B.; Sharpe, P. Head phantom for testing microwave systems for head imaging,” in Proc. Biomed. Eng. Conf., Cairo, Egypt, 2012, pp. 191–193.

- Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.T.; Almutairi, A.F. A portable non-invasive microwave based head imaging system using compact metamaterial loaded 3D unidirectional antenna for stroke detection. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterskog, M.; Petrovic, N.; O Risman, P. A multi-layered head phantom for microwave investigations of brain hemorrhages. In 2016 IEEE conference on antenna measurements & applications (CAMA), pp. 1–3. IEEE, 2016.

- Islam, M.S.; Almutairi, A.F. Experimental tissue mimicking human head phantom for estimation of stroke using IC-CF-DMAS algorithm in microwave based imaging system. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velander, J.; Redzwan, S.; Perez, M.D.; Asan, N.B.; Nowinski, D.; Lewen, A.; Enblad, P.; Augustine, R. A four-layer phantom for testing in-vitro microwave-based sensing approach in intra-cranial pressure monitoring. In 2018 IEEE International Microwave Biomedical Conference (IMBioC), pp. 49–51. IEEE, 2018.

- Joachimowicz, N.; Vasquez, J.T.; Turvani, G.; Dassano, G.; Casu, M.R.; Vipiana, F.; Duchene, B.; Scapaticci, R.; Crocco, L. “Head phantoms for a microwave imaging system dedicated to cerebrovascular disease monitoring.” In 2018 IEEE Conference on Antenna Measurements & Applications (CAMA), pp. 1–3. IEEE, 2018.

- Joachimowicz, N.; Conessa, C.; Henriksson, T.; Duchene, B. Breast phantoms for microwave imaging. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2014, 13, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, E.; Fakhoury, J.; Oprisor, R.; Coates, M.; Popović, M. Improved tissue phantoms for experimental validation of microwave breast cancer detection." In Proceedings of the fourth European conference on antennas and propagation, pp. 1–5. IEEE, 2010.

- Mashal, A.; Gao, F.; Hagness, S.C. Heterogeneous anthropomorphic phantoms with realistic dielectric properties for microwave breast imaging experiments. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2011, 53, 1896–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, T.; Samsuzzaman; Kibria, S. ; Islam, M.T. Experimental breast phantoms for estimation of breast tumor using microwave imaging systems. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 78587–78597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneras, V.; Bonnaudin, F. Biological tissues equivalent liquids in the frequency range 900–3000 MHz." In Proc. XXVIIIth URSI Gen. Assembly, pp. 1–4. 2005.

- Gunnarsson, T.; Joachimowicz, N.; Joisel, A.; Conessa, C.; Diet, A.; Bolomey, J.C. "Quantitative microwave breast phantom imaging using a planar 2.45 GHz system." Proc. XXIX Gen. Assem. URSI (2008).

- Henriksson, T.; Joachimowicz, N.; Conessa, C.; Bolomey, J.-C. Quantitative microwave imaging for breast cancer detection using a planar 2.45 GHz system. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2010, 59, 2691–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommy, H. Contribution to quantitative microwave imaging techniques for biomedical applications." PhD diss., Mälardalen University, 2009.

- Romeo, S.; Di Donato, L.; Bucci, O.M.; Catapano, I.; Crocco, L.Scarfì, M.R.; Massa, R. Dielectric characterization study of liquid-based materials for mimicking breast tissues. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2011, 53, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, L.M.; Mays, R.O.; Hagness, S.C. Development and application of human breast phantoms in microwave diagnostic and therapeutic technologies." In 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), pp. 6018–6021. IEEE, 2016.

- John, G.; Fear, E. A new breast phantom with a durable skin layer for microwave breast imaging. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2015, 63, 1693–1700. [Google Scholar]

- Särestöniemi, M.; Dessai, R.; Myllymäki, S.; Myllylä, T. A Novel Durable Fat Tissue Phantom for Microwave Based Medical Monitoring Applications. EAI BICT 2023 - 14th EAI International Conference on Bio-inspired Information and Communications Technologies, April 2023.

- Dessai, R. Evaluating a Breast Tumor Monitoring Vest with Flexible UWB Antennas and Realistic Phantoms - A Proof-of -Concept Study”, Master thesis, University of Oulu, (2022).

- https://www.itis.ethz.ch/virtual-population/tissue-properties/databaseM (2022).

- Dassault Simulia CST Suite. https://www.3ds.com/ (2022).

- Orfanidis, S.J. Electromagnetic Waves and Antennas. 2002, revised 2016, online: http://www.ece.rutgers.edu/~orfanidi/ewa/.

- Särestöniemi, M.; Sonkki, M.; Myllymäki, S.; Pomalaza-Raez, C. Wearable Flexible Antenna for UWB On-body and Implant Communications,” MPDI Telecom Journal, August 2021.

- https://www.embodi3d.com/files/category/7-brain/.

- Helander, H.F.; Fändriks, L. Surface area of the digestive tract – revisited. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Särestöniemi, M.; Taparugssanagorn, A.; Wisanmongkol, J.; Hämäläinen, M.; Iinatti, J. Comprehensive Analysis of Wireless Capsule Endoscopy Radio Channel Characteristics Using Anatomically Realistic Gastrointestinal Simulation Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 35649–35669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiourti, A.; Konstantina, S.N. A review of in-body biotelemetry devices: Implantables, ingestibles, and injectables. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 64, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, R.; Kaushik, A.; Park, J.; Abramson, A. Communication protocols integrating wearables, ingestibles, and implantables for closed-loop therapies. Device 1, no. 3 (2023).

Figure 1.

a) Preparing tumor phantom on a beaker, b) preparing brain phantom in a large with careful control of the temperature.

Figure 1.

a) Preparing tumor phantom on a beaker, b) preparing brain phantom in a large with careful control of the temperature.

Figure 2.

Setup to verify dielectric properties of phantoms with VNA and SPEAG probe.

Figure 2.

Setup to verify dielectric properties of phantoms with VNA and SPEAG probe.

Figure 3.

The tissue layer simulation model.

Figure 3.

The tissue layer simulation model.

Figure 4.

a) A negative model of the brain phantom, b) lower (left) and upper (right) molds of the brain after pouring the phantom mixture for solidification, c) solidified upper part of the brain phantom, d) whole brain phantom (upside down).

Figure 4.

a) A negative model of the brain phantom, b) lower (left) and upper (right) molds of the brain after pouring the phantom mixture for solidification, c) solidified upper part of the brain phantom, d) whole brain phantom (upside down).

Figure 5.

a) Outer mold for fat tissue, inner mold for glandular tissue, b) tumor phantom, c)Fat phantom with a tumorous glandular phantom inside, and d) The realistic phantom emulation platform for breast cancer detection studies with muscle phantom (2), fat phantom (3), glandular tissue phantom(4), and skin phantom (5).

Figure 5.

a) Outer mold for fat tissue, inner mold for glandular tissue, b) tumor phantom, c)Fat phantom with a tumorous glandular phantom inside, and d) The realistic phantom emulation platform for breast cancer detection studies with muscle phantom (2), fat phantom (3), glandular tissue phantom(4), and skin phantom (5).

Figure 6.

a) small and large intestines with realistic sizes, b) layered setup including skin, fat, muscle, and intestine layers.

Figure 6.

a) small and large intestines with realistic sizes, b) layered setup including skin, fat, muscle, and intestine layers.

Figure 7.

a)relative permittivity and b)conductivity v/s frequency (MHz) plots for skin phantom at 650, 750, and 850 .

Figure 7.

a)relative permittivity and b)conductivity v/s frequency (MHz) plots for skin phantom at 650, 750, and 850 .

Figure 8.

a)relative permittivity and b)conductivity v/s frequency (MHz) plot for fat phantom at 650 and 750 .

Figure 8.

a)relative permittivity and b)conductivity v/s frequency (MHz) plot for fat phantom at 650 and 750 .

Figure 9.

Skin phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulation using layer model 1. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are the same as presented in

Table 2 for skin phantom. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are the same as with average human tissue [

54].

Figure 9.

Skin phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulation using layer model 1. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are the same as presented in

Table 2 for skin phantom. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are the same as with average human tissue [

54].

Figure 10.

Brain phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 1. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are the same as presented in

Table 2 for brain phantom. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are the same as with average human tissue [

54].

Figure 10.

Brain phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 1. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are the same as presented in

Table 2 for brain phantom. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are the same as with average human tissue [

54].

Figure 11.

a) Muscle and b) intestinal phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 2. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are the same as presented in

Table 2 for muscle phantom. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are the same as with average human tissue [

54] for a) muscle and b) intestinal tissues.

Figure 11.

a) Muscle and b) intestinal phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 2. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are the same as presented in

Table 2 for muscle phantom. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are the same as with average human tissue [

54] for a) muscle and b) intestinal tissues.

Figure 12.

Solid and liquid fat phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 2. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are same as obtained in phantom measurements presented in

Table 2. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are same as with average human tissue [

54].

Figure 12.

Solid and liquid fat phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 2. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are same as obtained in phantom measurements presented in

Table 2. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are same as with average human tissue [

54].

Figure 13.

Solid and liquid fat phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 2. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are same as obtained in phantom measurements presented in

Table 2. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are same as with average human tissue [

54].

Figure 13.

Solid and liquid fat phantom verification with S11 and S21 simulations using layer model 2. In the phantom case, the dielectric properties of the tissue layers are same as obtained in phantom measurements presented in

Table 2. In the reference case, the dielectric properties are same as with average human tissue [

54].

Table 1.

Relative permittivity values at GHz, 4GHz, 6GHz and 8GHz [

54].

Table 1.

Relative permittivity values at GHz, 4GHz, 6GHz and 8GHz [

54].

| Tissue |

Frequency |

| 2 GHz |

4 GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

| Brain, grey and white matters |

49.7/36.7 |

46.6/34.5 |

43.7/32.4 |

40.9/30.4 |

| Brain tumor |

59.0 |

55.7 |

52.2 |

48.6 |

| Fat |

5.33 |

5.12 |

4.84 |

4.46 |

| Glandular tissue |

58.1 |

54.9 |

51.7 |

48.4 |

| Breast tumor |

63.0 |

59.1 |

56.6 |

55.4 |

| Skin |

38.6 |

36.6 |

34.9 |

33.2 |

| Muscle |

53.3 |

50.8 |

48.2 |

45.5 |

| Large intestine |

54.7 |

51.3 |

48.1 |

45.0 |

| Large intestine Lumen |

53.3 |

50.8 |

48.2 |

45.5 |

| Small intestine |

55.4 |

51.6 |

48.3 |

45.1 |

| Small intestine Lumen |

53.3 |

50.8 |

48.2 |

45.5 |

Table 2.

Incredients for different human tissue phantom recipes.

Table 2.

Incredients for different human tissue phantom recipes.

Phantom

type |

Concentration of Ingredients |

DI

Water |

Gelatine |

Sunflower oil |

DW

liquid1

|

Xanthum |

PG2

|

Sugar |

NaCl |

| Skin |

10 ml |

3.01 g |

1.68 ml |

0.83 ml |

- |

- |

|

|

| Tumor |

20.3 ml |

1.63 g |

1.1 ml |

0.9ml |

- |

|

|

|

| Brain |

9 ml |

1.5 g |

1.1 ml |

0.5 ml |

- |

|

|

|

Glandular

tissue |

25.2ml |

5.05g |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.525 |

- |

Muscle/

Intestine |

20ml |

6.02g |

3.36ml |

1.67ml |

1.67ml |

- |

- |

- |

| Fat |

3 ml |

2g |

- |

0.5 ml |

1 g |

50ml |

- |

- |

1DW liquid: Dish-washing liquid

2PG: Propylene glycol |

Table 3.

Thicknesses of tissue layers in Layer Model 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Thicknesses of tissue layers in Layer Model 1 and 2.

| |

Skin |

Fat |

Skull bone |

Brain |

Muscle |

Small intestine |

| Layer model 1 (head) |

1.2mm |

1.2mm |

7.5mm |

7.5mm |

- |

- |

| Layer model 2 (abdomen) |

2.2mm |

10mm |

- |

- |

8mm |

20mm |

Table 4.

Different Tumor and skin phantom mixture trials with their recipes.

Table 4.

Different Tumor and skin phantom mixture trials with their recipes.

| Phantom Type |

Sample Trial |

Concentration of ingredients |

| Water (ml) |

Gelatin (g) |

Oil (ml) |

Dishwasher (ml) |

| Tumor |

TS1 |

22 |

1.7 |

4.25 |

0.95 |

| TS2 |

8 |

1.7 |

4.25 |

0.95 |

| TS3 |

12.3 |

1.63 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

| TS4 |

14.3 |

1.63 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

| TS5 |

16.3 |

1.63 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

| TS6 |

18.3 |

1.63 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

| TS7 |

20.3 |

1.63 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

| TS8 |

22.3 |

1.63 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

| Skin |

SS1 |

6 |

3.01 |

1.68 |

0.83 |

| SS2 |

8 |

3.01 |

1.68 |

0.83 |

| SS3 |

10 |

3.01 |

1.68 |

0.83 |

Table 5.

Different Tumor and skin phantom mixture trials and their dielectric properties after 5 hours, 24 hours, 1 week, and 10 days.

Table 5.

Different Tumor and skin phantom mixture trials and their dielectric properties after 5 hours, 24 hours, 1 week, and 10 days.

| Phantom Type |

Sample Trial |

Permittivity/Conductivity |

| After 5 hours |

After 24 hours |

After 1 Week |

After 10 days |

| 2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

| Tumor |

TS1 |

43.2/1.38 |

38.6/4.97 |

41.06/1.08 |

36.61/4.26 |

40.8/1.36 |

36.96/4.99 |

38.06/1.56 |

33.3/4.32 |

| TS2 |

28.4/2.87 |

24.6/3.16 |

28.7/2.81 |

24.6/3.63 |

29.3/2.145 |

24.31/3.62 |

25.3/1.98 |

20.6/3.13 |

| TS3 |

31.7/1.23 |

29.2/3.9 |

31.2/1.12 |

29.7/4.11 |

30.9/1.3 |

28.2/4.16 |

21.2/1.31 |

18.5/4.8 |

| TS4 |

38.7/1.03 |

35.12/4.23 |

38.92/1.04 |

34.27/4.09 |

38.7/1.122 |

33.21/4.03 |

37.92/1.02 |

26.25/3.98 |

| TS5 |

42.27/1.24 |

37.51/4.52 |

43.12/1.32 |

39.21/5.0 |

42.27/1.43 |

38.13/5.1 |

39.18/1.13 |

31.42/4.82 |

| TS6 |

49/1.45 |

45.2/5.53 |

50.9/1.46 |

45.27/5.6 |

50.34/1.54 |

43.52/5.34 |

40.4/1.32 |

39.7/4.99 |

| TS7 |

62.8/1.68 |

59.0/6.32 |

62.9/1.69 |

57.2/6.52 |

61.01/1.48 |

56.47/6.13 |

57.3/1.21 |

48.6/5.82 |

| TS8 |

70.5/1.75 |

67.3/6.84 |

69.0/1.75 |

63.1/7.16 |

69.51/1.48 |

61.26/6.951 |

61.1/1.83 |

56.4/6.27 |

| Skin |

SS1 |

30.07/0.93 |

26.37/3.2 |

35.07/0.08 |

27.14/2.15 |

29.86/1.655 |

25.12/3.478 |

20.26/0.54 |

17.25/2.12 |

| SS2 |

35.1/1.34 |

31.7/3.36 |

38.9/1.07 |

32.8/3.12 |

41.39/1.72 |

31.96/5.38 |

23.5/1.82 |

18.7/2.28 |

| SS3 |

40.3/1.48 |

36.9/4.78 |

38.2/1.96 |

34.1/3.76 |

41.22/1.54 |

34.11/5.51 |

30.1/0.93 |

26.37/3.2 |

Table 6.

Glandular phantom recipe and its dielectric properties after 5 hours, 24 hours, 1 week and 10 days.

Table 6.

Glandular phantom recipe and its dielectric properties after 5 hours, 24 hours, 1 week and 10 days.

| Concentration of ingredients |

Permittivity/Conductivity |

| Water (ml) |

Gelatin (g) |

Sugar (g) |

After 5 hours |

After 24 hours |

After 1 Week |

After 10 days |

| 2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

8

GHz |

2.5

GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

| 252 |

50.5 |

5.25 |

62.03/2.03 |

50.95/8.23 |

44.75/12.8 |

61.82/2.15 |

50.78/8.03 |

45.39/11.58 |

62.45/2.15 |

51.44/8.36 |

48.11/12.25 |

57.1/2.02 |

50.7/8.34 |

44.99/12.96 |

Table 7.

Muscle phantom recipe and its dielectric properties after 5 hours, 24 hours, 1 week, and 10 days.

Table 7.

Muscle phantom recipe and its dielectric properties after 5 hours, 24 hours, 1 week, and 10 days.

| Concentration of ingredients |

Permittivity/Conductivity |

| Water (ml) |

Gelatin (g) |

Oil (ml) |

NaCl (ml) |

Dishwasher (ml) |

After 5 hours |

After 24 hours |

After 1 Week |

After 10 days |

| 2.5 GHz |

6

GHz |

8 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

2.5 GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

| 200 |

60.2 |

33.6 |

166.6 |

16.6 |

54.98/

1.75 |

48.9/

5.63 |

45.7/

8.2 |

55.1/

1.8 |

48.59/

5.399 |

45.34/

8.6 |

54.79/

1.91 |

47.99/

5.12 |

45.1/

8.59 |

51.84/

3.67 |

45.1/

7.63 |

43.3/

10.2 |

Table 8.

Dielectric properties (Permittivity/conductivity) of fat phantom [

52] at different frequencies.

Table 8.

Dielectric properties (Permittivity/conductivity) of fat phantom [

52] at different frequencies.

| |

2 GHz |

6 GHz |

8 GHz |

| Fat |

6.4/0.75 |

5.0/0.953 |

4.76/1.02 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).