1. Introduction

The invention of light emitting diodes (LEDs) and the advancement of power supplies have led to improving lighting systems, replacing the inconveniences of traditional lamps [

1]. LED lighting is characterized by high luminous efficiency, long life and high reliability, but due to the low luminous flux of a single LED, it cannot be used in most applications, and when there is a high demand for illumination, such as street lighting, plaza lighting, and other applications, it is necessary to combine a few LEDs in series or in parallel. However, the V-I curve of each LED is not the same due to negative temperature coefficient, leading to a large change in the conduction current, so the LED driver is designed to a fixed current to power LED strings [

2], and the current equalization control is required to solve the problem of current imbalance between the LED strings.

Up to now, there are many LED current equalization strategies have been proposed can be divided into two categories, namely, active current equalization and passive current equalization. For the active current equalization method, it can be divided into linear type and switching type. First of all, for the linear type, it uses the linear regulator or current mirror connected in series with the LED string. Generally speaking, the linear regulator is the switch is operated in the linear region and can be regarded as the variable resistor [

3]. In order to achieve the LED current balance, the literature [

4] proposes an adaptive voltage circuit between the main power stage and the LED strings, so that the voltage across the switch of the linear regulator can be regulated to reduce the loss of energy. Although it is simple to control the variable resistance to achieve current equalization, the power loss during conduction is large, so it is more suitable for use in low-power applications. As for current mirroring, it utilizes the characteristics of transistors to map the reference current to other transistors in equal or proportional currents so that the currents flowing through each transistor are equal. This active method commonly uses semiconductor components or packaged in the form of integrated circuits. Also, this method is small in size and low in cost, but is not suitable for high-power applications. Another active current equalization method is to add an additional switching converter to achieve current equalization by switching. The literatures [

5,

6] present that each string of LEDs is connected to the corresponding converter, and the output current of the converter is used to achieve current equalization of each string of LEDs, but its drawback is that the cost of the circuit is relatively high, and the control circuit is relatively complex. In the LED driver proposed in [

7,

8,

9], a dimming switch is added to each LED string, and the duty cycle of the pulse width modulated (PWM) signal is adjusted to change the average value of current flowing through the LED string to achieve current equalization, whose disadvantage is that each LED string is connected in series with a switch, resulting in a larger number of switches and increasing the difficulty and complexity of design. Since the active current equalization method uses additional circuits, making the overall size larger, loss higher, control loop complex, etc., reducing the number of current detection circuits and regulation circuits is the goal of improving active current equalization.

Passive methods utilize the characteristics of passive components to achieve current equalization, and are divided into capacitor current equalization and transformer current equalization. The capacitor equalization method mentioned in [

10] is when two different LED series have a voltage difference, the current equalization capacitor for charging and discharging is added, because the capacitor in the steady state has the characteristics of the ampere-second balance, that is to say, the average value of the capacitor current in a cycle is zero. The literature [

11] shows a two-channel interleaved step-down LED driver using current equalization capacitors. In this circuit, the energy of the previous stage is transferred to the next LED driver through the current equalization capacitor, and thus part of the energy is consumed in the process of the transfer, which leads to relatively large current errors between the LEDs in the later stages. Moreover, every time a channel is expanded, an additional number of components close to the number of components needed for a buck circuit are used. The transformer current equalization method can be also a method used for current equalization of LED strings through the same turns of the transformer windings, and the primary and secondary sides of the transformer will be connected with two different LED strings. When the voltage of the LED string is unbalanced, a differential mode signal will be generated on the transformer, and the current equalization transformer will be activated to force the currents through the LED strings to be identical by utilizing the characteristics of the same number of turns on the primary and secondary sides. The current equalization circuit using differential-mode transformer proposed in the literatures [

12,

13] must add a freewheeling diodes or a zener diode to each LED string to ensure that the magnetic element has sufficient demagnetization voltage to make the switch completely demagnetized during the switch cutoff period, so the duty cycle of the switch will be limited.

Today’s high power density LED driver circuits require switching power supplies to cope with the increased demand for LED loads. Although increasing the switching frequency of the switches can reduce the size of the passive components, the problems of switching loss and electromagnetic interference (EMI) become more serious with hard switching. In order to solve the above problems, the soft switching technology has been developed, which can be divided into zero voltage switching (ZVS) and zero current switching (ZCS), which can reduce the cross area between current and voltage during the switching period to minimize the switching loss. The literature [

14] proposes a two-stage multi-channel LED driver, the front stage is a buck converter to regulate the rear CLL resonant converter, so that the latter can be operated at the resonant frequency through the primary-side coils of the transformers in series connection to achieve current equalization between the LED string modules, and in each LED string current equalization capacitor is added to balance the LED string module current flow in the opposite direction of the two LED strings. In order to expand the LED strings, more transformers are needed to be connected in series. The literature [

15] proposes a step-down converter without any transformer, which operates in DCM mode with ZCS. At the same time, the amperage-second balance of the resonant capacitor is utilized to achieve the current equalization between the LED strings. In comparison, the difference between the literatures [

16] and [

15] is that the resonant current is operated in CCM and DCM, and the switch achieves ZVS turn-on when operated in CCM and ZCS turn-off when operated in DCM. The literature [

17] proposes a LED driver that combines an LLC resonant converter and a current balancing circuit. A half-bridge LLC converter is used to provide the primary-side switches ZVS turn-on and the secondary-side rectifier diodes ZCS turn-off, and a current equalization capacitor is added to the secondary side to balance the current flowing through the LED strings. The literature [

18] proposes an LCLC resonant LED driver, where the resonant tank of the LCLC can provide a relatively large ZVS range of the switch, and at the same time, reduce the current stress of the switch, and finally achieve the LED current regulation through the auxiliary switch. However, because the number of resonant components in this circuit is relatively large, there are several resonance points, causing the control of the range of operating frequency to be designed carefully. In addition to the original resonant topology, the ZCS turn-off applied to an additional auxiliary resonant circuit or snubber. The literature [

19] adopts an interleaved buck-boost structure, consisting of two phases and adds one coupling inductor to replace the original two inductors, which are resonated with the parasitic capacitance of the main switch to realize the ZVS turn-on of the switch. In [

20], a passive damping circuit is added to reduce the overlapping area of switching voltage and current during the switching period, so many passive components and diodes are added, resulting in additional losses. In addition, the auxiliary inductors in the damping circuit oscillate with the parasitic components of the switch during the switch cutoff period, resulting in additional switching losses. In [

21], a dimmable LED driver based on H-bridge and differential-mode transformer are presented.

In this paper, a series resonant LED driver circuit based on differential-mode transformer current equalization is proposed. The proposed LED driver utilizes the characteristics of a differential-mode transformer to equalize the current flowing through each LED string. In the proposed circuit, the resonant circuit enables the half-bridge switch to realize ZVS turn-on. At the same time, when one even number of LED strings is increased, only one differential-mode transformer and one additional set of diodes need to be added, so that the number of parts used can be reduced. The purpose of this paper is to improve the magnetic resetting of the differential-mode transformer. Compared with [

12], the circuit proposed in this paper is not limited by the duty cycle of the gate driving signals for the main switches, so that a higher load regulation range can be achieved.

3. Operating Principle

Before introducing the analysis of the circuit behavior, there are some assumptions and symbol definitions:

(1) Vin is the input voltage; LS1 and LS2 are the output LED strings and the voltages on them are equal to the output voltages Vo1 and Vo2, respectively.

(2) S1 and S2 are the switches of the upper and lower switches of the half-bridge, Db1 and Db2 are the body diodes of the switches S1 and S2, respectively, Coss1 and Coss2 are the output capacitances of the switches S1 and S2, respectively, and the corresponding forward conduction voltages are assumed to be zero.

(3) The characteristics of rectifier diodes D1 and D2 and magnetic resetting diode D3 are ideal.

(4) The coupling coefficient of the differential-mode transformer is one, i.e., only the magnetizing inductance Lm is taken into account, and the leakage inductances Llk1 and Llk2 are ignored.

(5) The output capacitors Co1 and Co2 are large enough to be considered as constant.

(6) The current through the resonant inductor Lr is iLr, and the voltage on the resonant capacitor Cr is vCr.

(7) vds1 is the voltage on the switch S1, vds2 is the voltage on the switch S2, vD1 is the voltage on the diode D1, vD2 is the voltage on the diode D2, vD3 is the voltage on the diode D3, and vLm is the voltage on the magnetizing inductance Lm.

(8) ids1 is the current flowing through the switch S1, ids2 is the current flowing through the switch S2, iD1 is the current flowing through the diode D1, iD2 is the current flowing through the diode D2, iD3 is the current flowing through the diode D3, iN1 is the primary-side current of the differential-mode transformer T1, iN2 is the secondary-side current of the differential-mode transformer, iLm is the current flowing through the magnetizing inductance Lm, ILED1 is the current flowing through the first LED string LS1, and ILED2 is the current through the second LED string LS2.

(9) vgs1 and vgs2 are the driving signals for upper arm the switches S1 and S2 respectively.

(10) Ts is the switching period, and fs is the switching frequency.

Figure 2 shows key waveforms relevant to the proposed circuit.

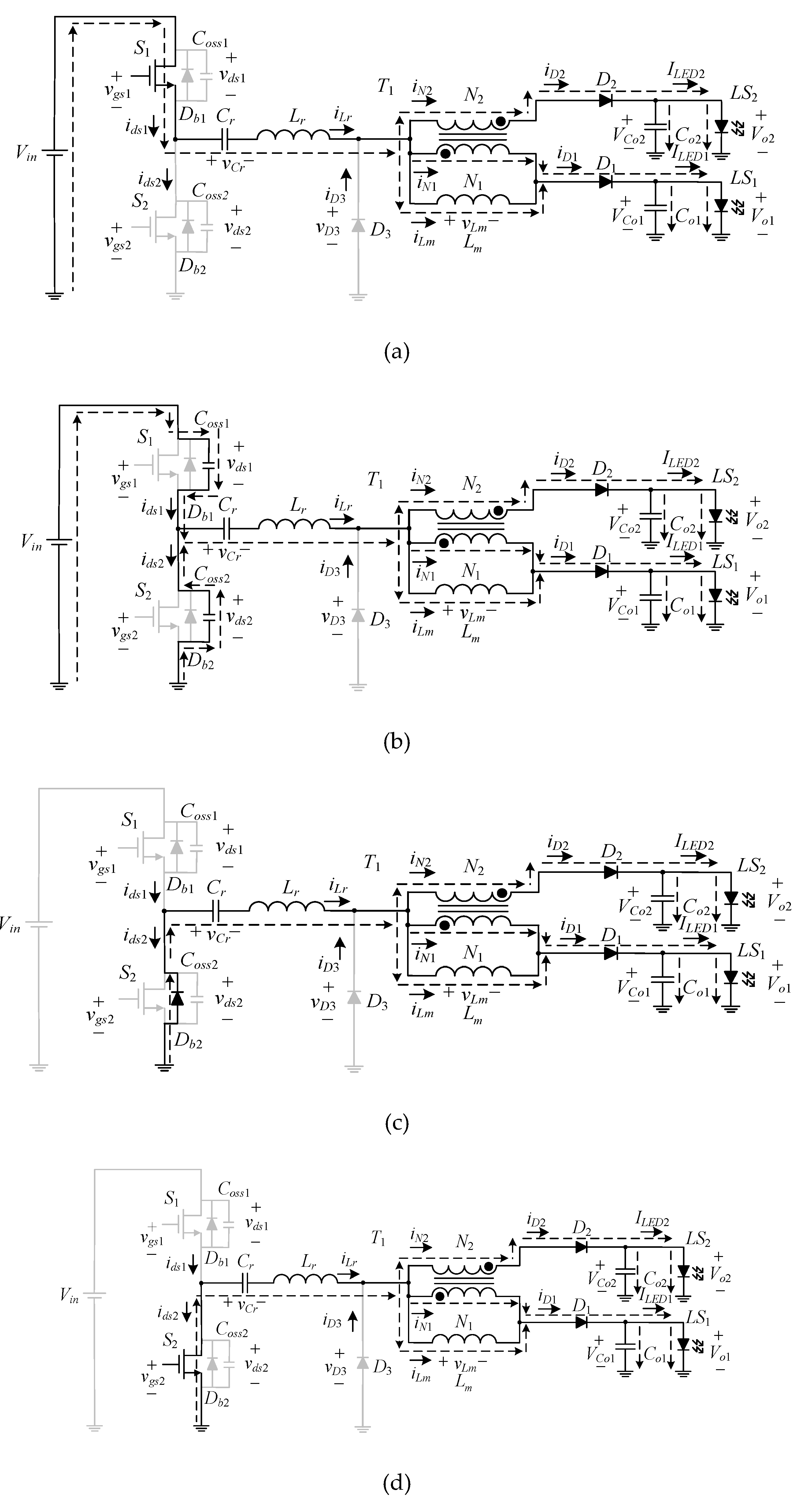

State 1.

: As shown in

Figure 3a, the switch

S1 is on, the switch

S2 is off, and the resonant inductor current

iLr resonates from negative to zero. Sequentially, the resonant inductor

Lr and the resonant capacitor

Cr resonate with each other, and the resonant inductor current

iLr starts to flow positively from zero. The current flows from the input

Vin, through the switch

S1, the resonant capacitor

Cr, the resonant inductor

Lr, the diodes

D1 and

D2, and the differential-mode transformer

T1 to the LED strings

LS1 and

LS2. If there is a voltage difference between the two LED strings, the differential-mode transformer is activated, and the voltage on

Lm, called

vLm, is clamped at half of the difference in voltage between the two LED strings, and the magnetizing inductance

Lm starts to be linearly excited. Once the switch

S1 cuts off, the circuit enters state 2.

State 2.

: As shown in

Figure 3b, the switches S

1 and S

2 are off. During this state, the resonant inductor current

iLr still flows positively, and the current flows to the LED strings

LS1 and

LS2 through the differential-mode transformer

T1 and the freewheeling diodes

D1 and

D2. In this state, the operation of the differential-mode transformer

T1 and the two LED strings

LS1 and

LS2 is the same as that in the previous state. Since both of the switches are in the off-and the resonant current

iLr must continue, the resonant inductor current

iLr is the same as that in the previous state. The resonant inductor current

iLr charges the output capacitor

Coss1 of the switch

S1 and discharges the output capacitor

Coss2 of the switch

S2, respectively. The moment the output

Coss1 is charged to the input voltage

Vin and the output

Coss2 is discharged to zero, the circuit enters state 3.

State 3.

: As shown in

Figure 3c, the switches

S1 and

S2 are still cutoff. During this state, the output capacitor

Coss2 of the switch

S2 has been discharged to zero, causing the body diode

Db2 of the switch 0

S2 to conduct, and the resonant inductor current

iLr is still positively flowing and gradually decreasing. In this state, the differential-mode transformer

T1 and the two LED series

LS1 and

LS2 operate as in the previous state. Once the switch

S2 is turned on, the circuit enters state 4.

State 4.

: As shown in

Figure 3d, the switch

S1 is still off and the switch

S2 is on. During this state, since the body diode of

S2 has been first conducted in the previous state, the voltages across the switches

S1 and

S2 are close to zero, so the switch

S2 is turned with ZVS. In addition, the resonant inductor current

iLr flows in the positive direction and decreases gradually. In this state, the differential-mode transformer

T1 and the LED strings

LS1 and

LS2 operate as in the previous state. As soon as the resonant inductor current

iLr decreases to zero and the circuit enters state 5.

State 5.

: As shown in

Figure 3e, the switch

S1 remains off and the switch

S2 remains on. During this state, the resonant inductor current

iLr starts to flow from zero in the opposite direction. In addition, the magnetizing inductor

Lm of the differential-mode transformer

T1 is demagnetized through the freewheeling diode

D1 and the magnetic resetting diode

D3, so the magnetizing inductance current

iLm decreases linearly. Note that this experienced time in this state is much smaller than half of the switching period. Once the magnetizing inductance current

iLm drops to zero, the circuit proceeds to state 6.

State 6.

: As shown in

Figure 3f, the switch

S1 is still off and the switch

S2 is continuously on. During this state, the resonant inductor current

iLr flows negatively through the diode

D3. In addition, since the magnetizing inductor current

iLm has been demagnetized to zero, so the freewheeling diodes

D1 and

D2 are both cut off and there is no energy sent to the output side. Therefore, the energy required for the LED strings

LS1 and

LS2 is supplied by the output capacitors

Co1 and

Co2, respectively. The moment the switch

S2 is cut off, the circuit enters state 7.

State 7.

: As shown in

Figure 3g, the switches

S1 and

S2 are cut off. During this state, the resonant inductor current

iLr still flows negatively through

D3, and the freewheeling diodes

D1 and

D2 are still cut off. In addition, the operation of the differential-mode transformer

T1 and the output is the same as the previous state. Since the switches

S1 and

S2 are off, the resonant inductor current

iLr discharges

Coss1 and charges

Coss2. As soon as the output capacitance

Coss1 discharges to zero and the output capacitance

Coss2 charges to

Vin, the circuit enters state 8.

State 8.

: As shown in

Figure 3h, the switches

S1 and

S2 are in the off-state. During this state, since the output capacitor

Coss1 of the switch

S1 has been discharged to zero, the body diode

Db1 of the switch is on, and the resonant inductor current

iLr flows through the diode

D3, the resonant inductor

Lr, the resonant capacitor

Cr, the body diode

Db1 of the switch

S1, and the input. In addition, the differential-mode transformer and the two LED strings

LS1 and

LS2 operate in the same way as in the previous state. Once the upper arm switch

S1 turns on and enters state 9.

State 9.

: As shown in

Figure 3i, the switches

S1 is on and the switch

S2 is off. During this state, since the body diode

Db1 of the switch has been on in the previous state, the switch

S1 can realize ZVS turn-on, and the resonant inductor current

iLr flows negatively and rises continuously. In addition, the differential-mode transformer and the two LED series

LS1 and

LS2 operate as in the previous state. The moment the resonant inductor current

iLr rises to zero, the circuit proceeds to the next cycle.

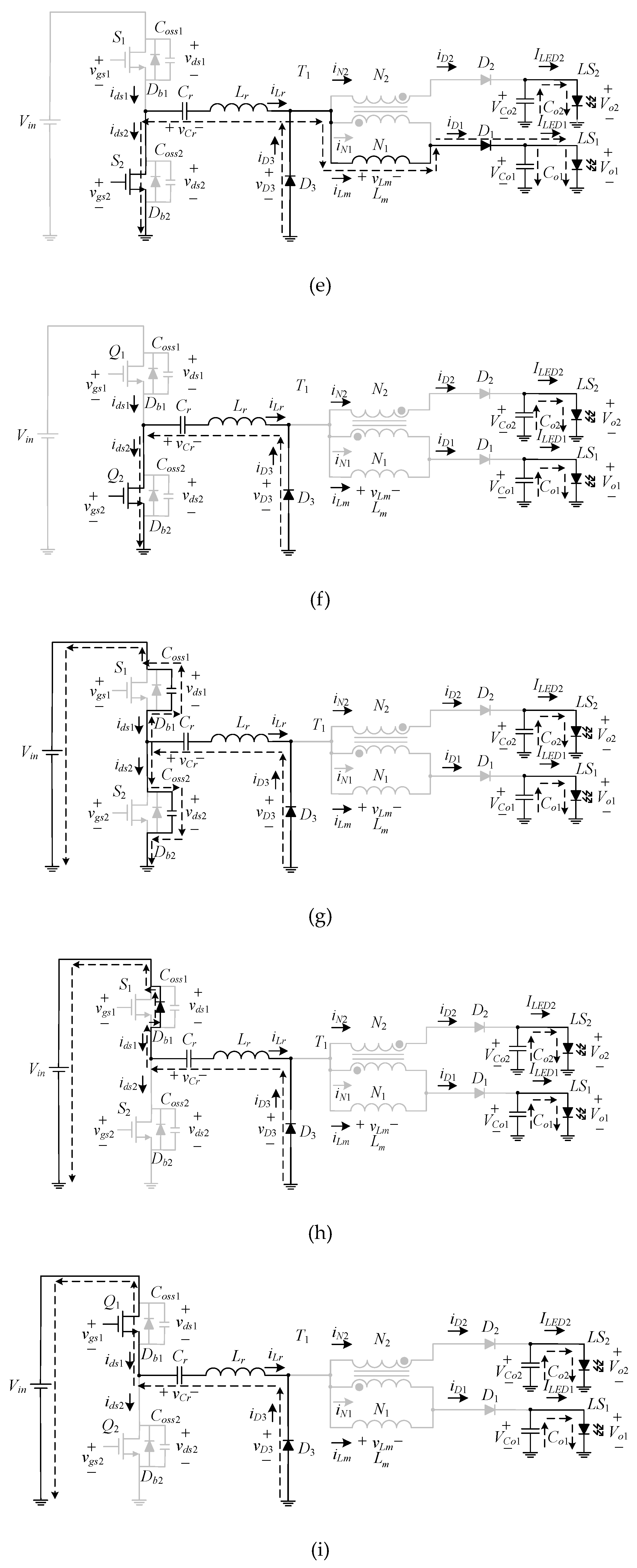

3.1. Voltage Gain

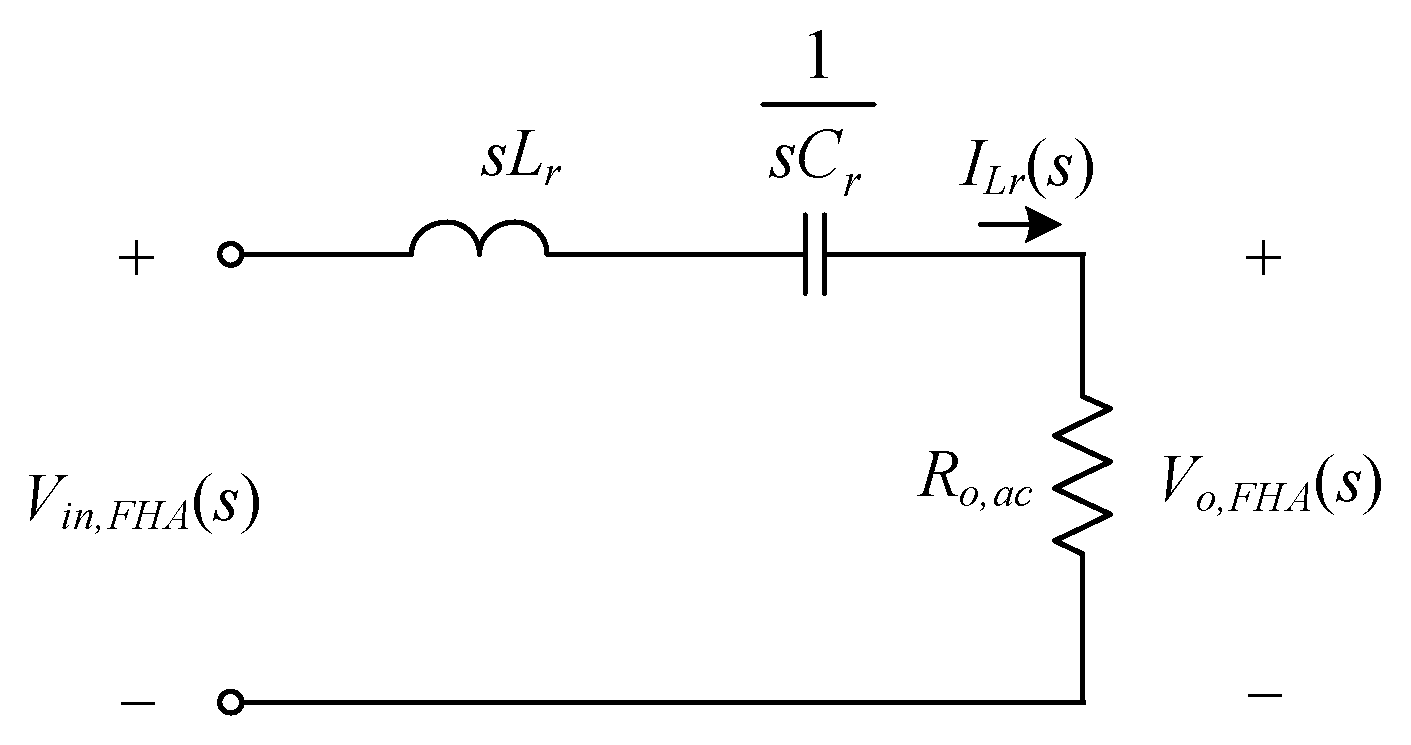

The first harmonic approximation (FHA) is utilized herein to find the equivalent output AC load resistance Ro,ac, reflected from the secondary side to the primary side, to be derived as follows.

First, the average value

ILr,avg of the half-cycle resonant current

iLr is the sum of the currents in the two LED strings, equal to the total output current

Io:

Also, the peak value

ILr,peak and RMS value

IL,rms of the resonant current

iLr can be expressed as follows:

The output voltage

vo of the resonant tank is the voltage on the diode

D3, which is a unipolar square wave, that is,

Thus, the fundamental RMS value

Vo,FHA,rms of the output voltage

vo of the resonant tank is

Eventually, dividing (5) by (3) yields

On the other hand, the input voltage

vin of the resonant can be expressed as

Therefore, the RMS value of the fundamental wave of

vin is

From the above derivation, the relationship between the input fundamental waveform and the output fundamental waveform of the resonant tank can be found. By using (5) and (8), the DC gain

Mdc of the circuit can be expressed by

According to (3), (5) and (8), the s-domain equivalent circuit of the proposed circuit is shown in

Figure 4.

According to

Figure 4, the voltage gain

M(

s) of the circuit is given by

The defined resonant radian frequency ω

r, the characteristic impedance

Zr, and the quality factor

Q are

Substituting (11) into (10) yields

Substituting

and

into (10) and letting

, the voltage gain

M of the proposed circuit is given by

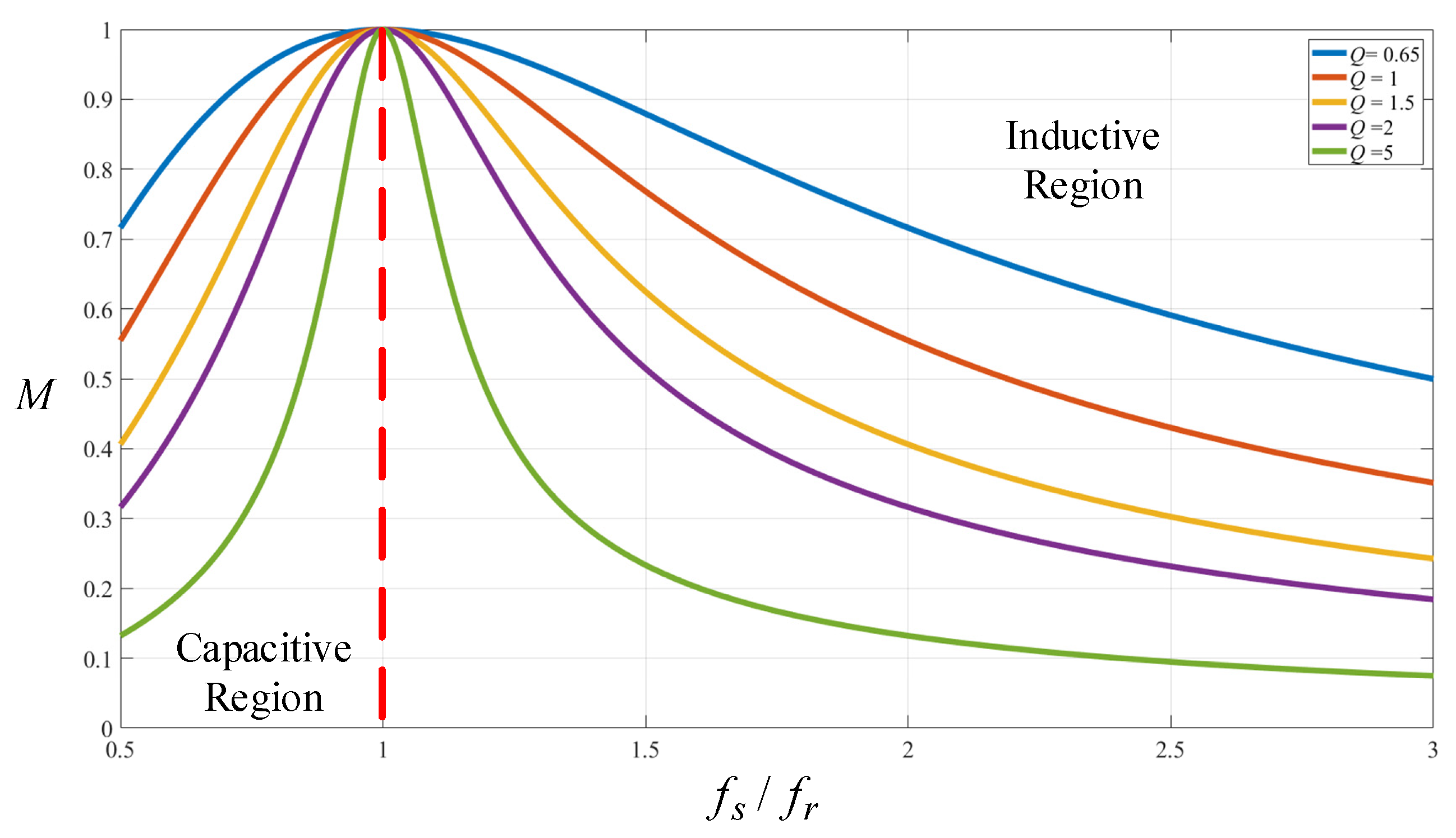

Figure 5 shows the curve of voltage gain

M versus the ratio of switching frequency

fs to resonant frequency

fr for different values of quality factor

Q. In the case of a fixed resonant elements, the smaller the load resistance is, the larger the value of

Q is, the curve of the voltage gain

M is steeper, and the voltage gain is more likely to be caused by the change of frequency, so the stability of the system is poorer but the response speed of voltage regulation is faster. On the contrary, the smaller the value of

Q is, the larger the frequency change range is needed to stabilize the output voltage.

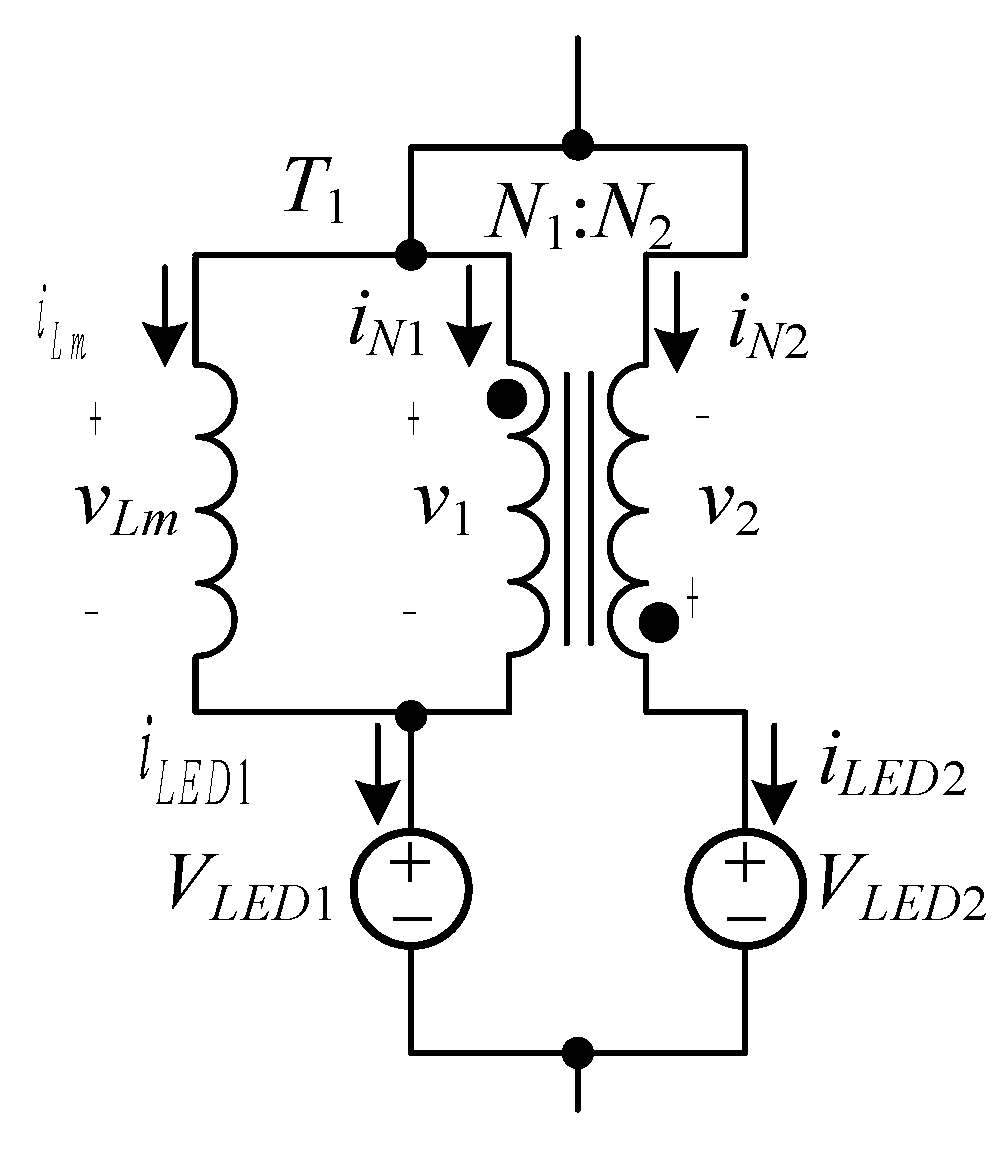

Figure 6 shows the current equalization circuit of the differential-mode transformer

T1, where

N1 and

N2 are the primary and secondary windings of the differential-mode transformer

T1 with

N1 equal to

N2,

Lm is the primary-side magnetizing inductance, and

LED1 and

LED2 are the loads connected in series to

N1 and

N2, respectively. In addition,

iN1 and

iN2 are the primary-side and secondary-side currents of

T1, respectively.

iLm is the current flowing through the magnetizing inductance

Lm,

v1 and

v2 are the primary-side and secondary-side voltages of

T1, respectively, and

vLm is the voltage on the magnetizing inductance

Lm of

T1.

Since the turns ratio is one and the polarity dots are in the opposite direction, the following are the results

In

Figure 6, according to Kirchhoff’s voltage law, it can be known that

When two LED strings have the same voltages on them, i.e.

VLED1=

VLED2, according to (14) and (16), there is no voltage on the differential-mode transformer

T1, i.e.,

T1 is not activated. When a voltage imbalance occurs, a balancing voltage on the magnetizing inductance is generated, as shown in (17). Accordingly,

T1 is activated, forcing the primary and secondary sides of

T1 to have the same currents, i.e., equalizing the currents in

LED1 and

LED2 due to the turns ratio of one.

However, in practice, there must be a magnetizing inductance

Lm. Therefore, in the case of voltage imbalance, the balanced voltage will energize the magnetizing inductance and generate the magnetizing current

iLm, and the average value of this current will be the current error between the two LED strings. In

Figure 6, according to Kirchhoff’s current law, it can be seen that

Accordingly, in the process of current equalization, the current in the magnetizing inductance Lm of T1, called iLm, will cause the current equalization error.

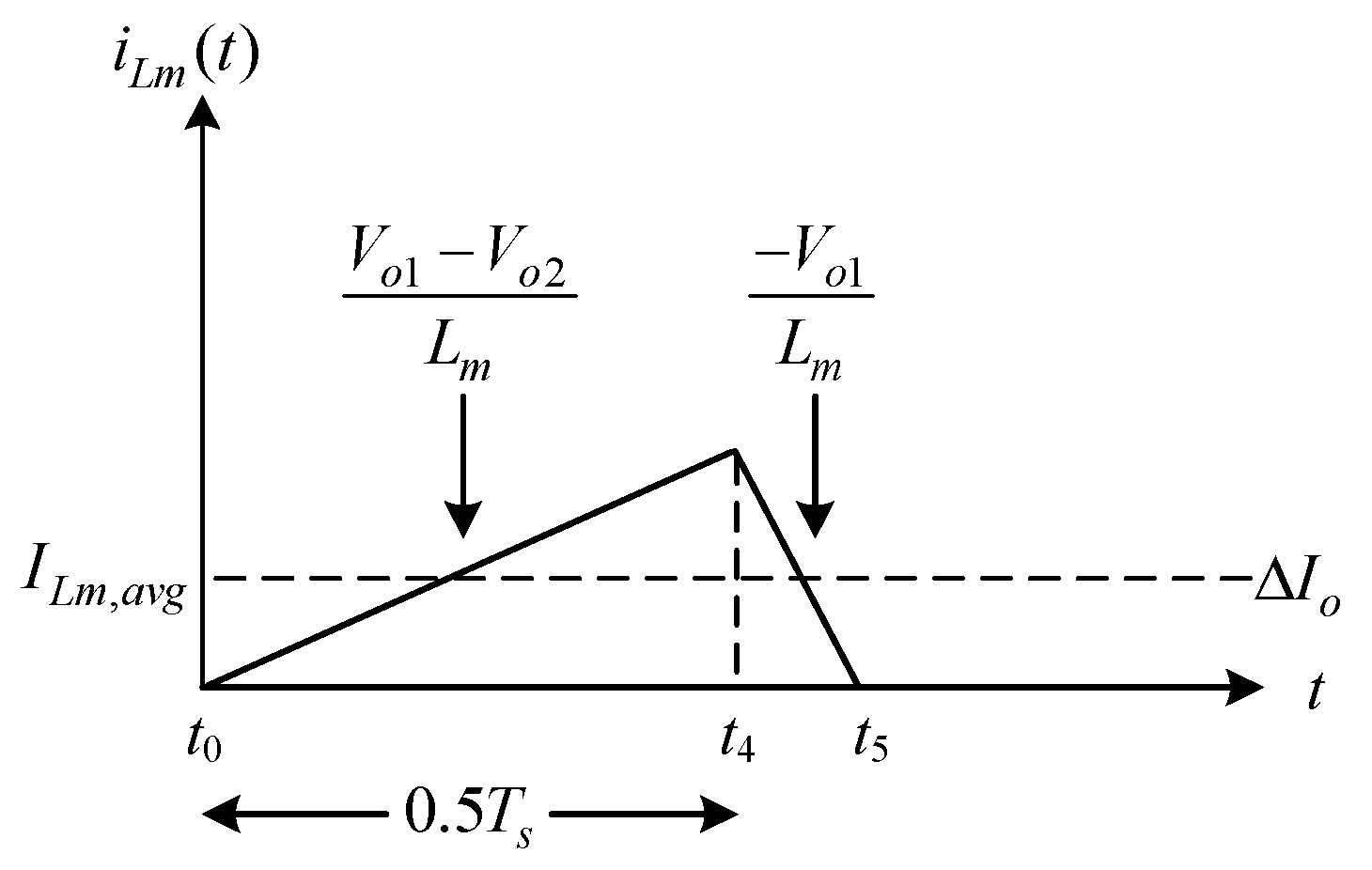

From

Section 3, it can be seen that the magnetizing inductance

Lm is linearly excited in states 1 to 4 (

) and the voltage

vLm is

. In state 5, the magnetizing inductance

Lm is linearly demagnetized, and the voltage

vLm is

.

Figure 7 shows the operating behavior of the magnetizing inductance.

From

Figure 7, the elapsed time of the magnetizing inductance

Lm is 0.5

Ts, and the magnetization voltage is much smaller than the demagnetization voltage. So, the demagnetization time can be ignored, and the average value of the magnetizing inductance current, called

ILm,avg, can be expressed as

where

is the difference in voltage between the two LED strings, namely,

.

After that, the average

Iavg of the currents of the two LED strings can be expressed by

Substituting (18) and (19) into (22) yields

Sequentially, the current sharing error percentage

ε is defined to be

By substituting (23) into (24), the current error

can be expressed as

By substituting (25) into (20), the relationship between the current error percentage and the magnetizing inductance

Lm can be obtained to be

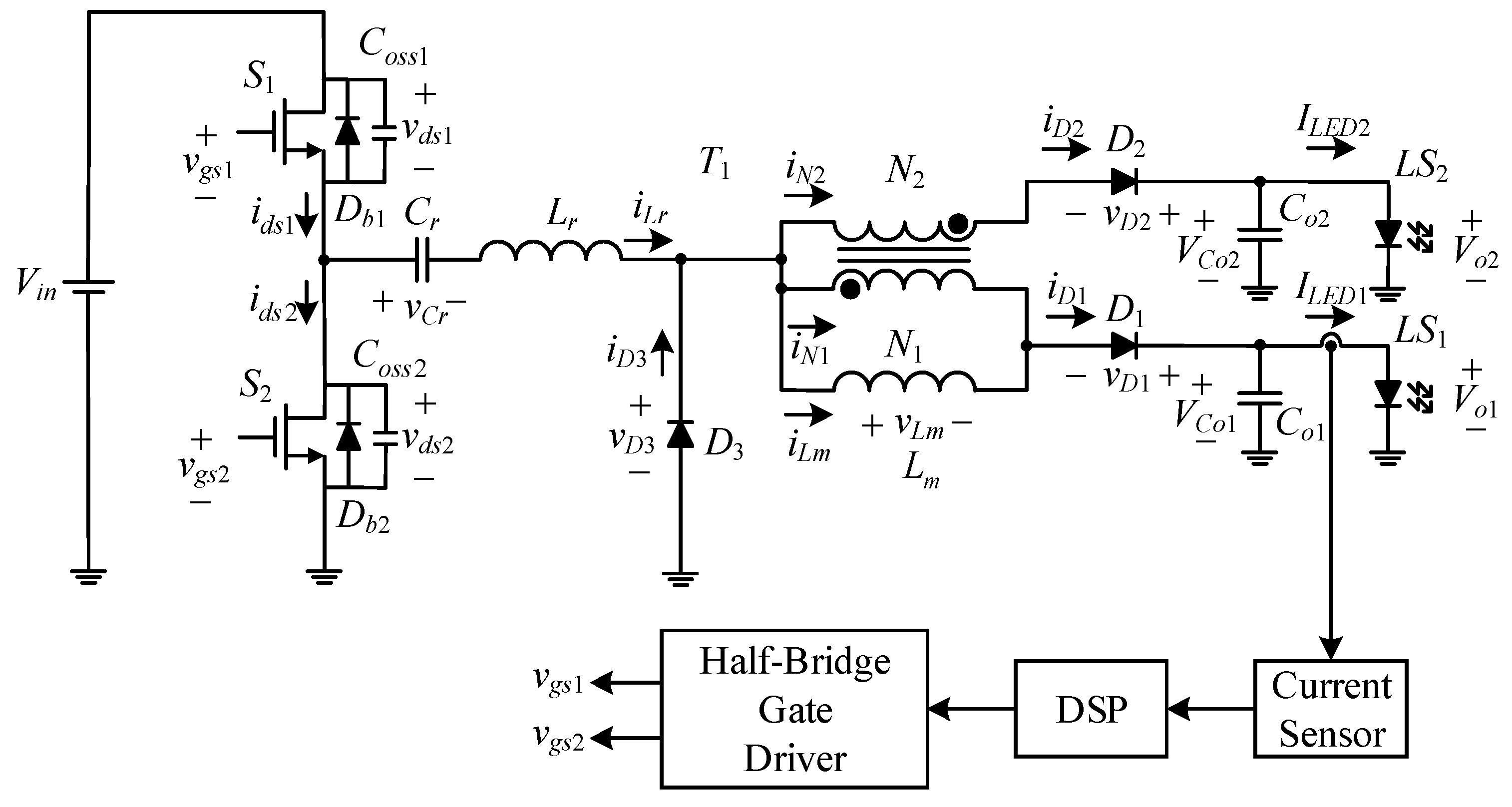

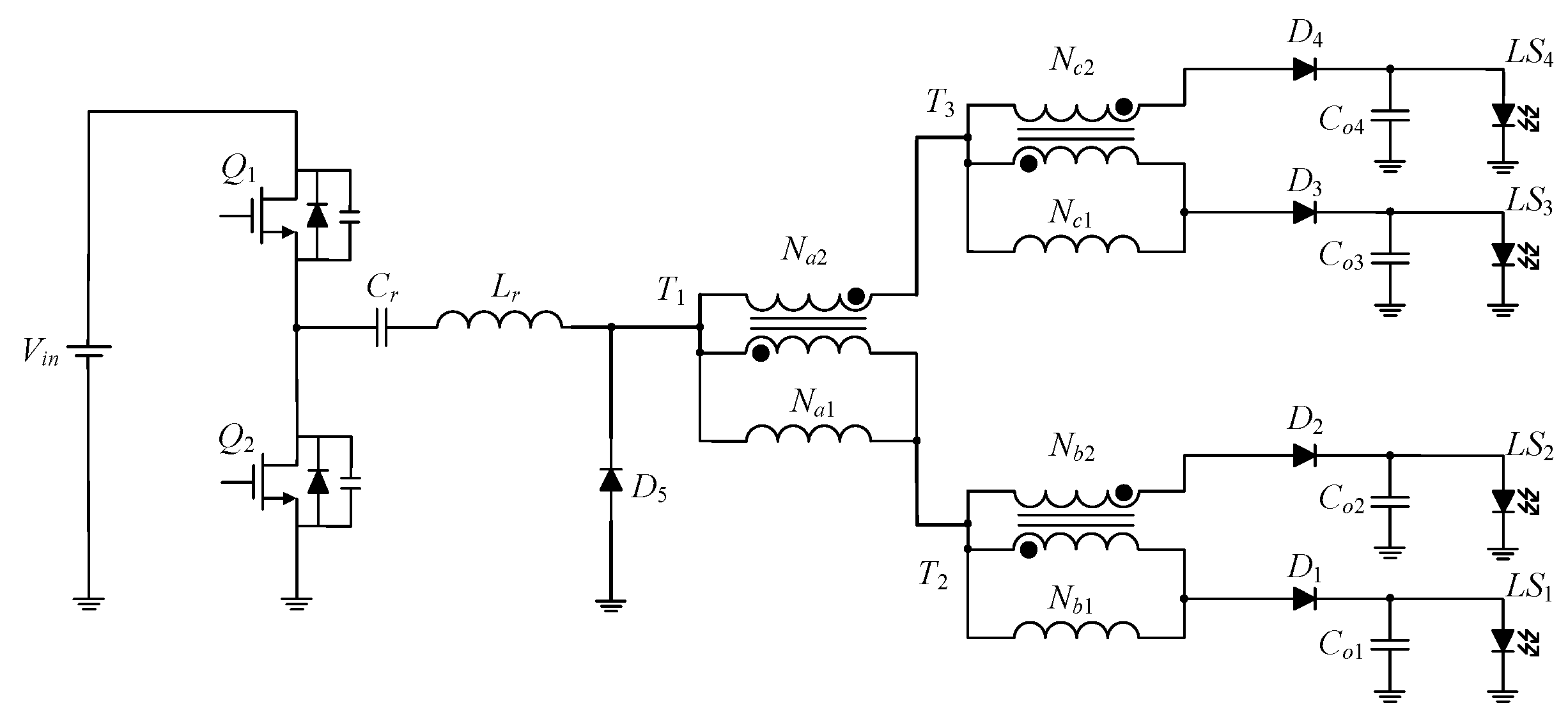

Figure 1.

System configuration of the proposed circuit.

Figure 1.

System configuration of the proposed circuit.

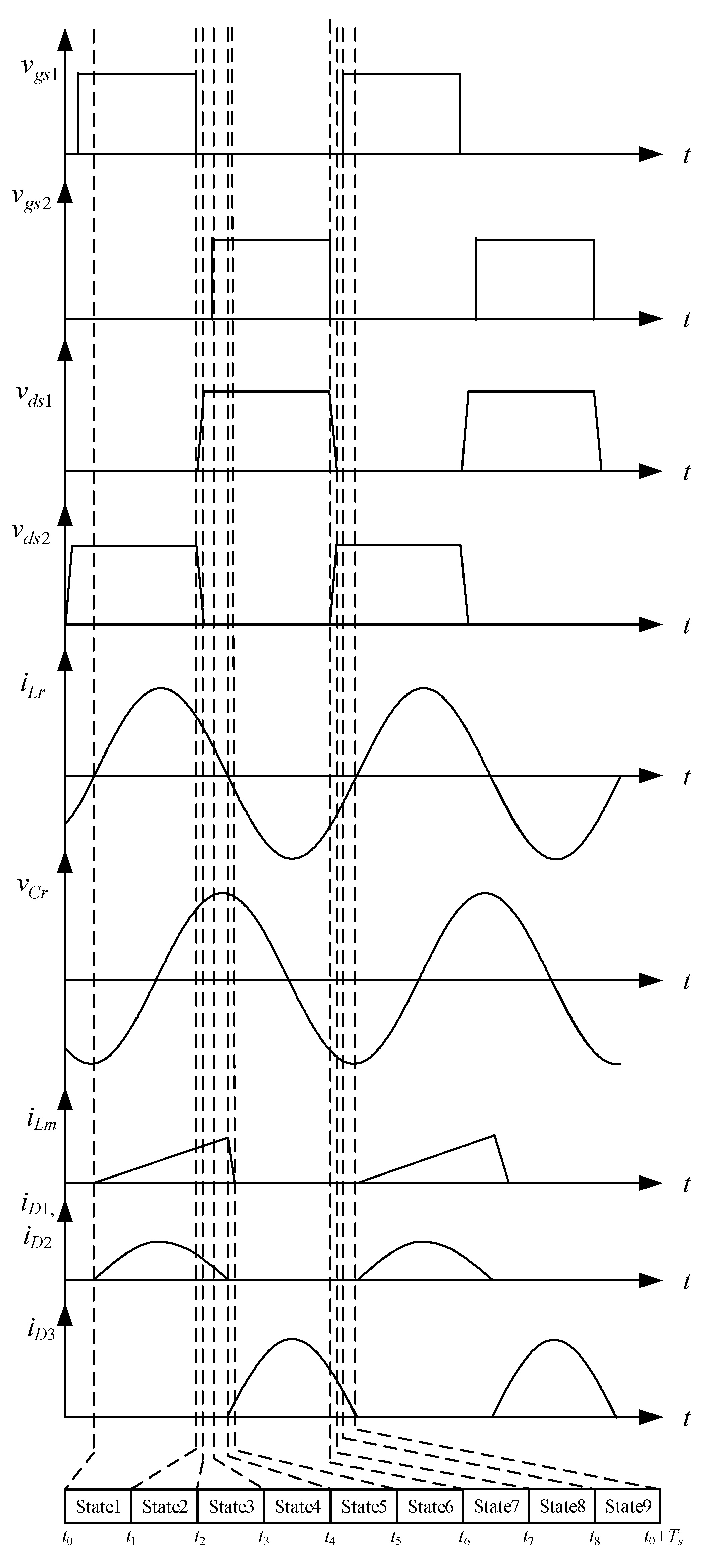

Figure 2.

Key waveforms relevant to the proposed circuit.

Figure 2.

Key waveforms relevant to the proposed circuit.

Figure 3.

Current flow: (a) state 1; (b) state 2; (c) state 3; (d) state 4; (e) state 5; (f) state 6; (g) state 7; (h) state 8; (i) state 9.

Figure 3.

Current flow: (a) state 1; (b) state 2; (c) state 3; (d) state 4; (e) state 5; (f) state 6; (g) state 7; (h) state 8; (i) state 9.

Figure 4.

s-domain equivalent of the proposed circuit.

Figure 4.

s-domain equivalent of the proposed circuit.

Figure 5.

Voltage gain curve of the proposed circuit.

Figure 5.

Voltage gain curve of the proposed circuit.

Figure 6.

Current equalization circuit based on the differential-mode transformer.

Figure 6.

Current equalization circuit based on the differential-mode transformer.

Figure 7.

Operating behavior of magnetizing inductance.

Figure 7.

Operating behavior of magnetizing inductance.

Figure 8.

Four-channel LED circuit.

Figure 8.

Four-channel LED circuit.

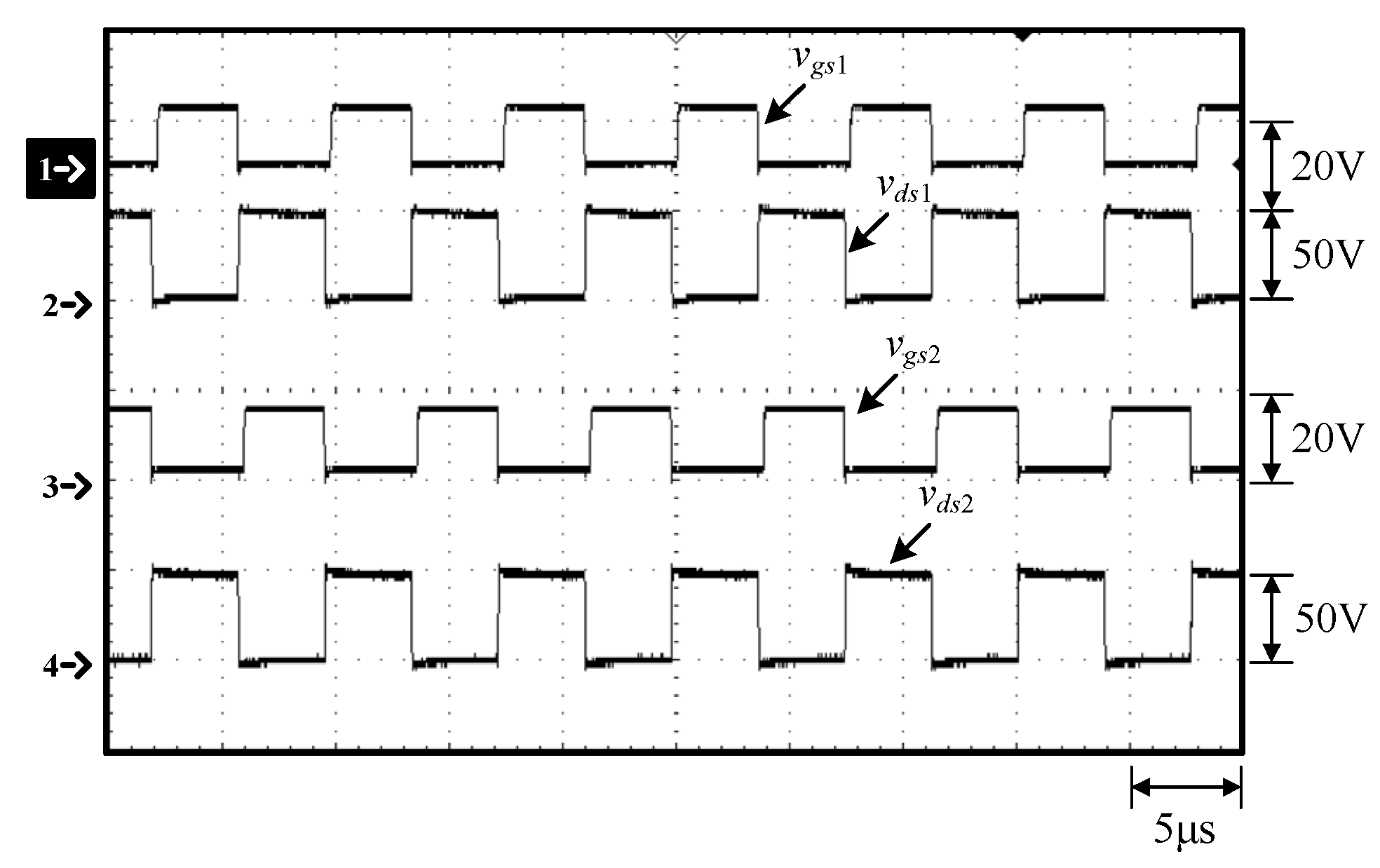

Figure 9.

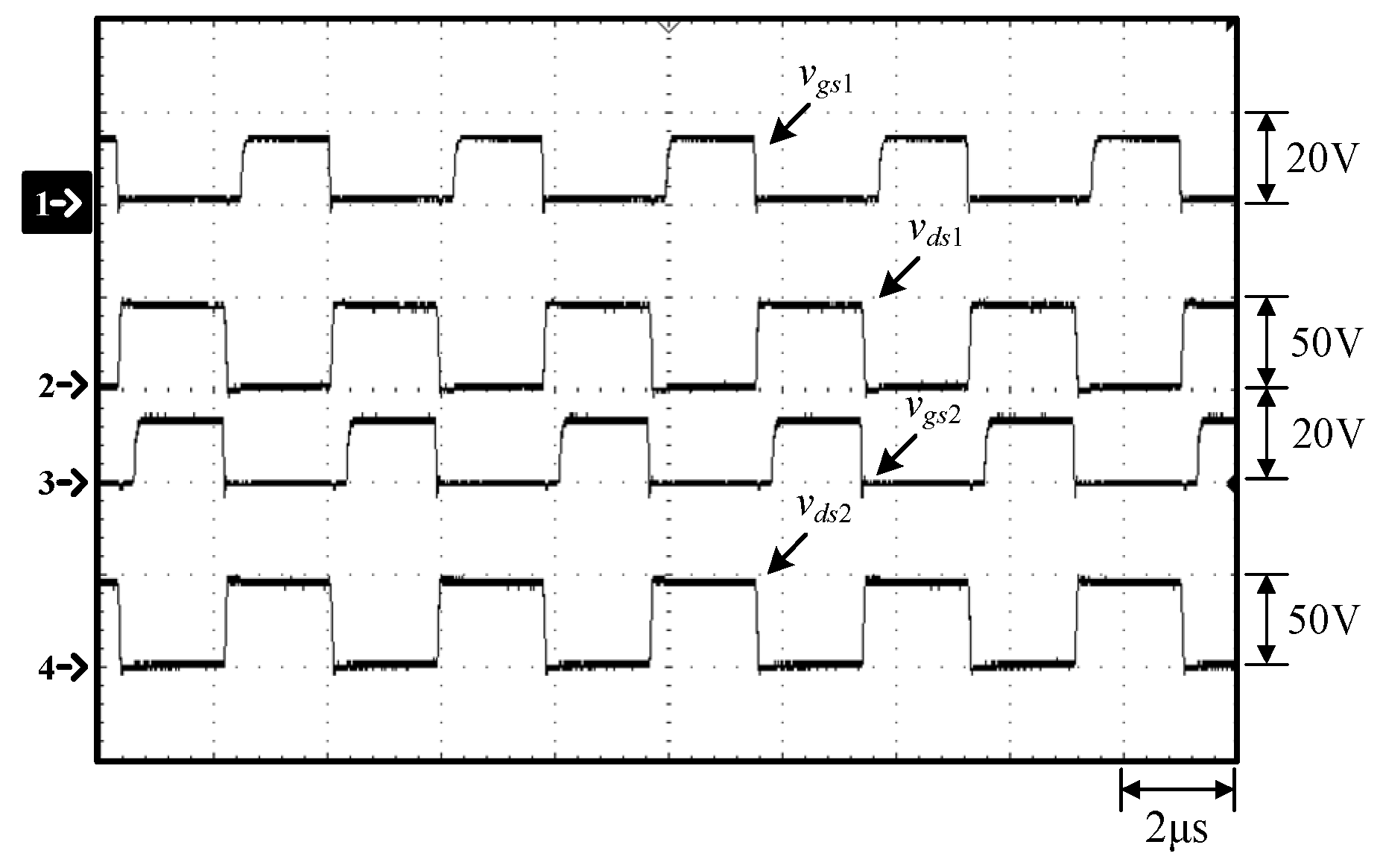

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1; (3) vgs2; (4) vds2.

Figure 9.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1; (3) vgs2; (4) vds2.

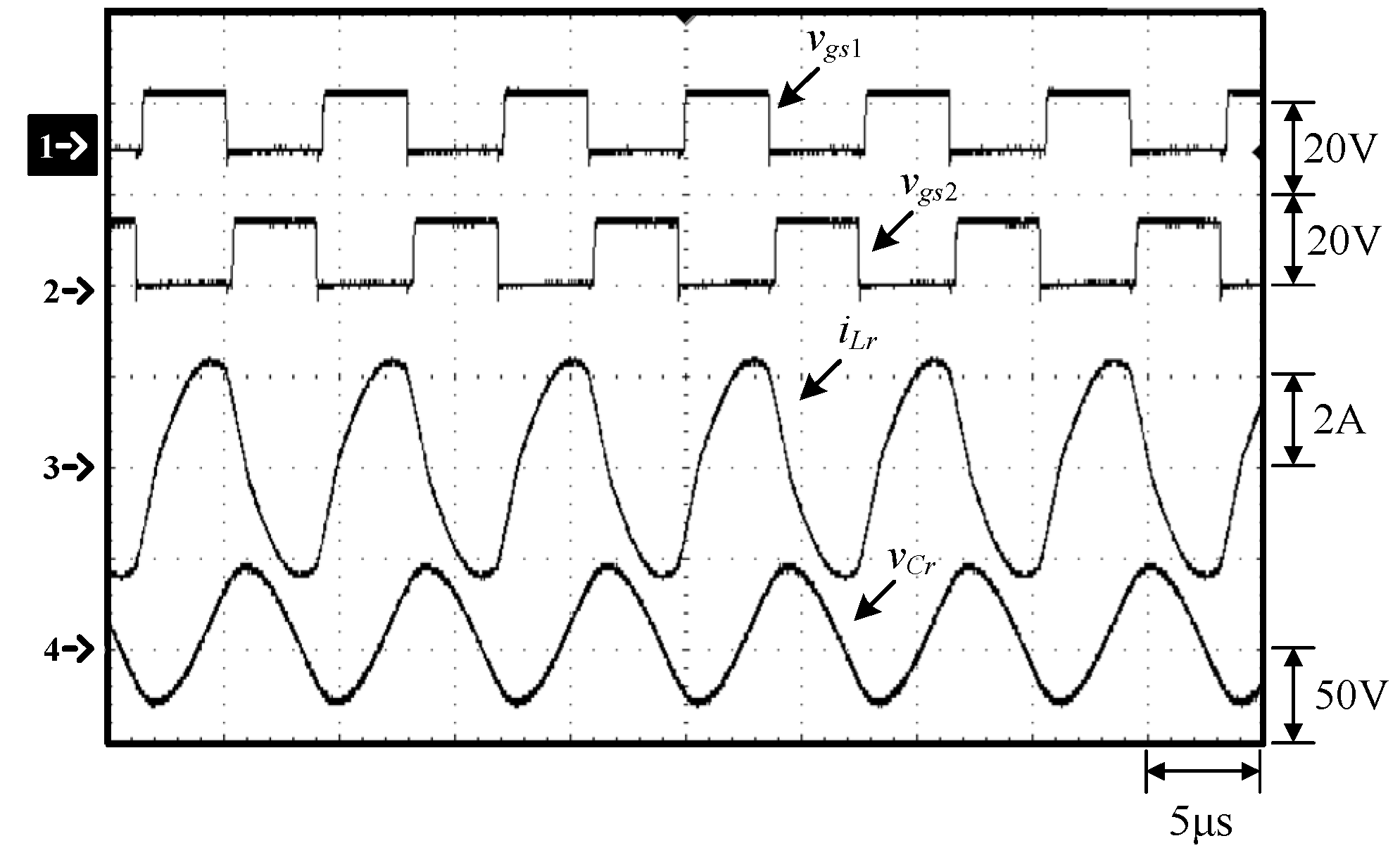

Figure 10.

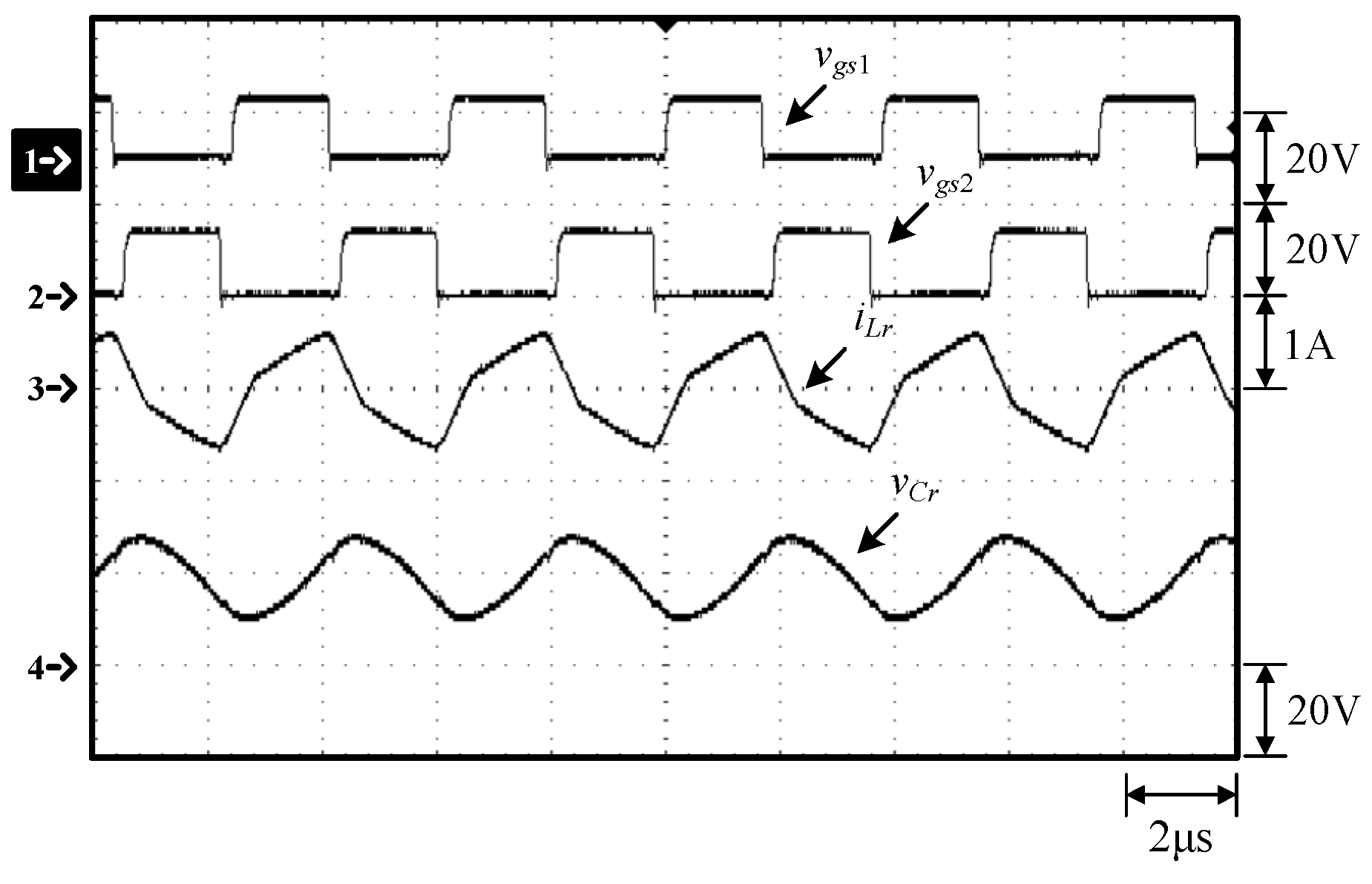

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vgs2; (3) iLr; (4) vCr.

Figure 10.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vgs2; (3) iLr; (4) vCr.

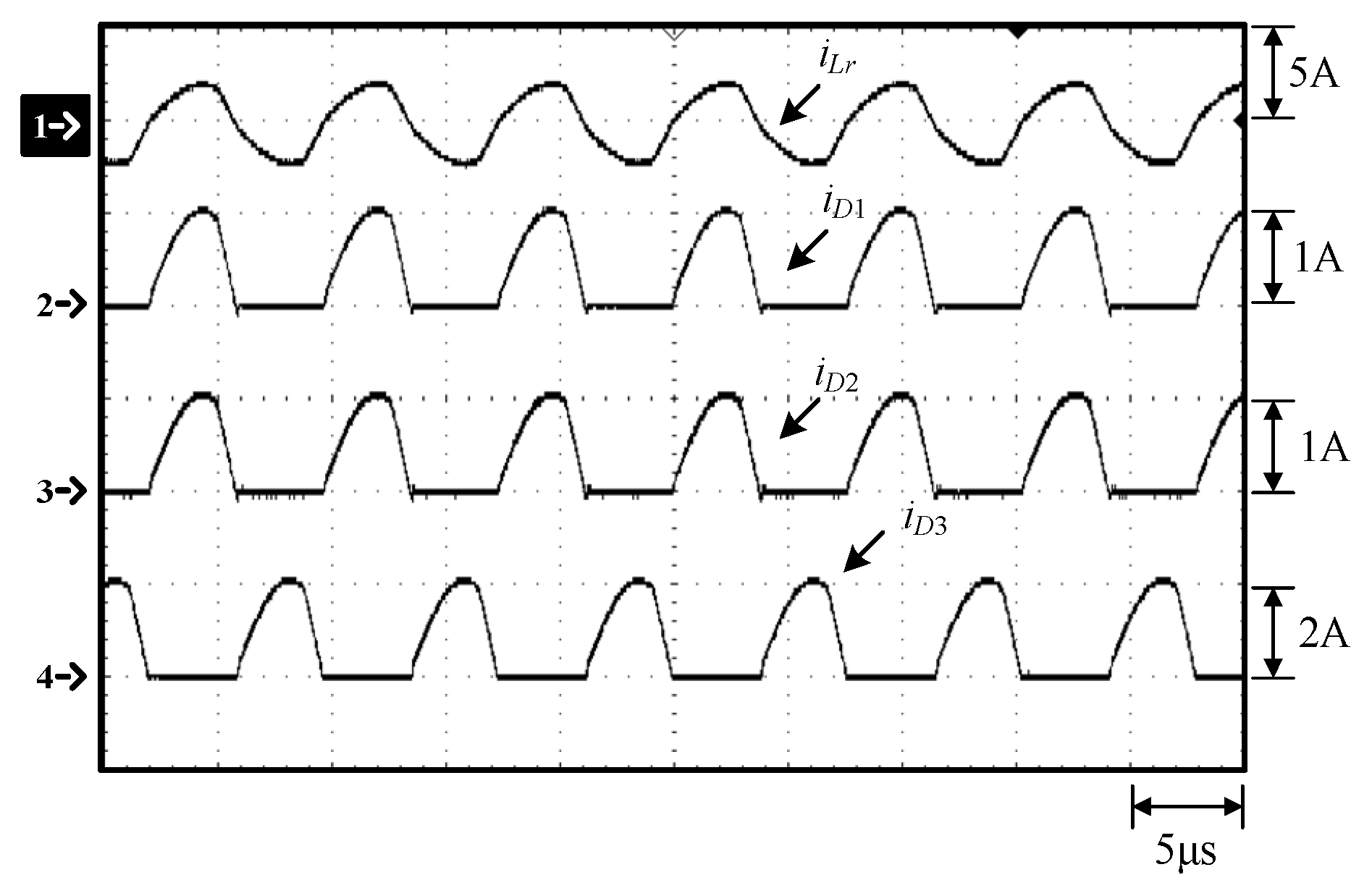

Figure 11.

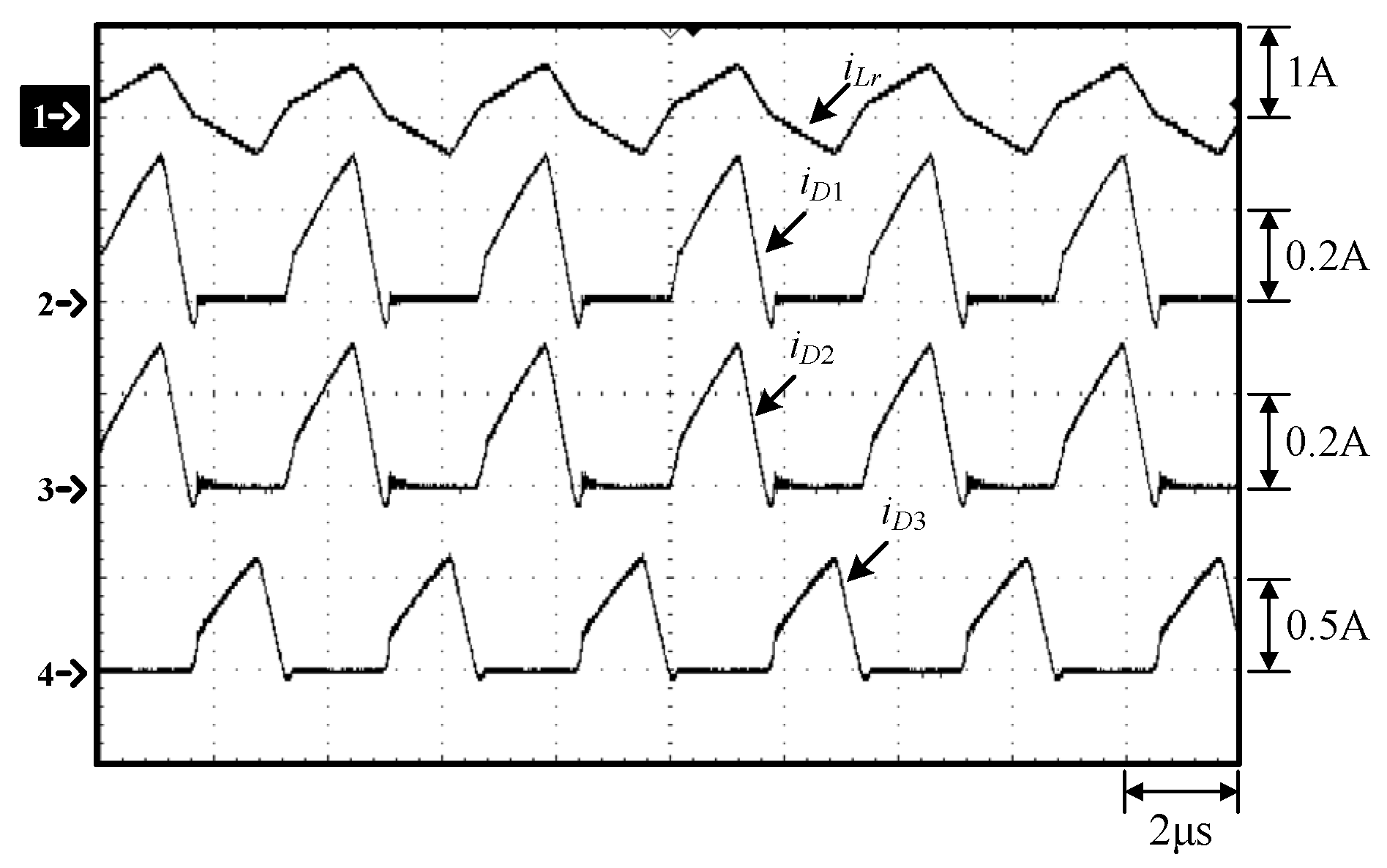

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) iLr; (2) iD1; (3) iD2; (4) iD3.

Figure 11.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) iLr; (2) iD1; (3) iD2; (4) iD3.

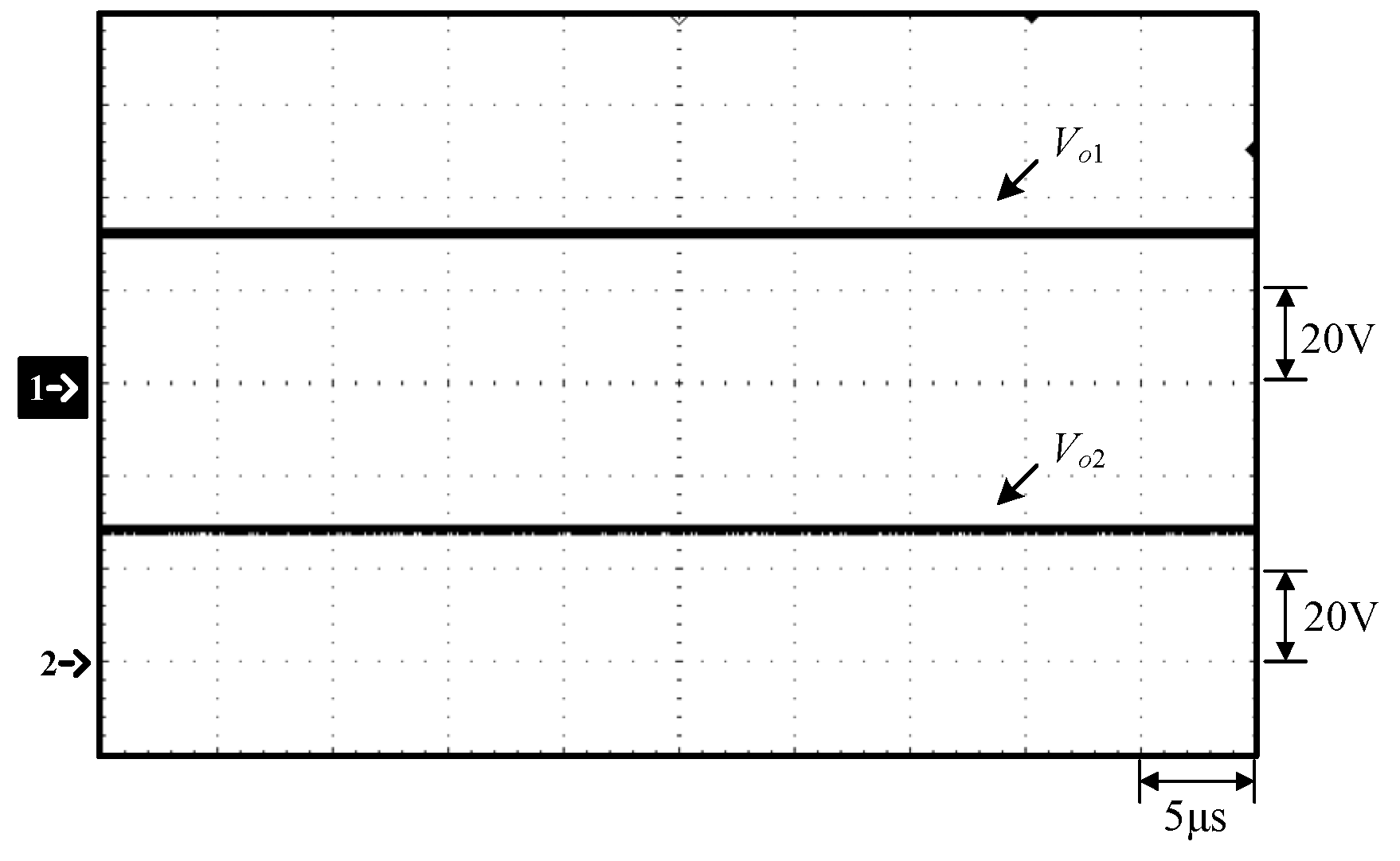

Figure 12.

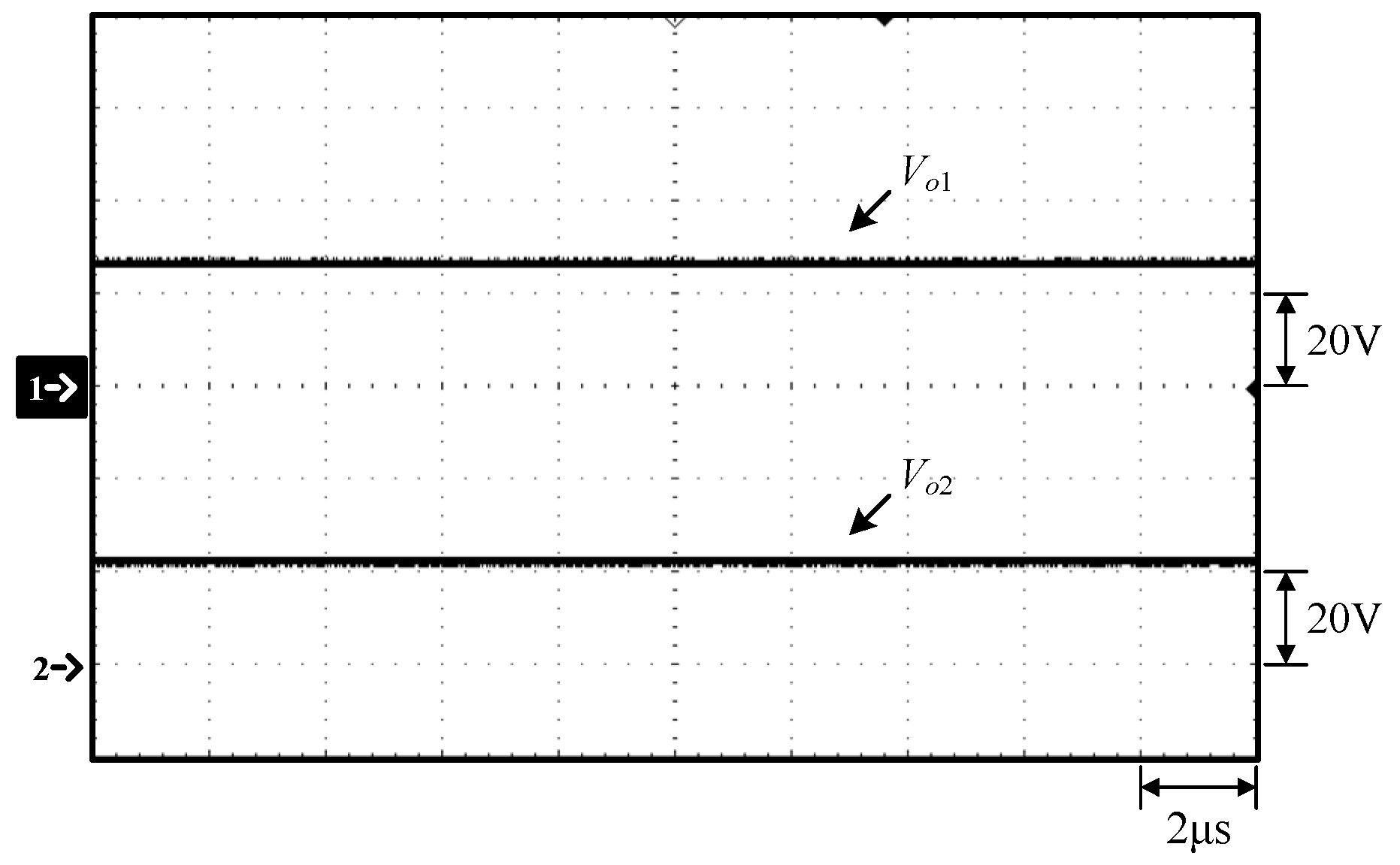

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) Vo1; (2) Vo2.

Figure 12.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) Vo1; (2) Vo2.

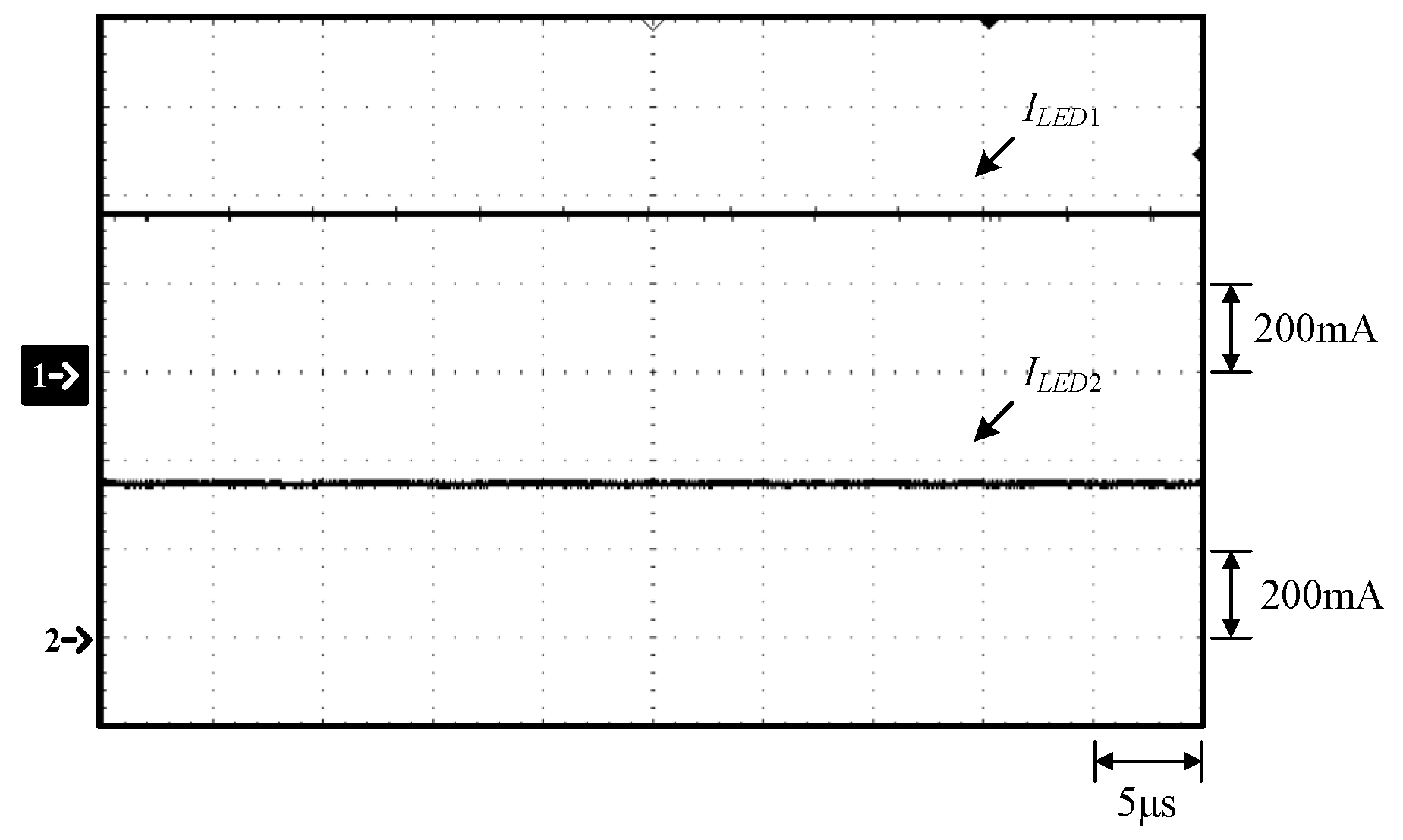

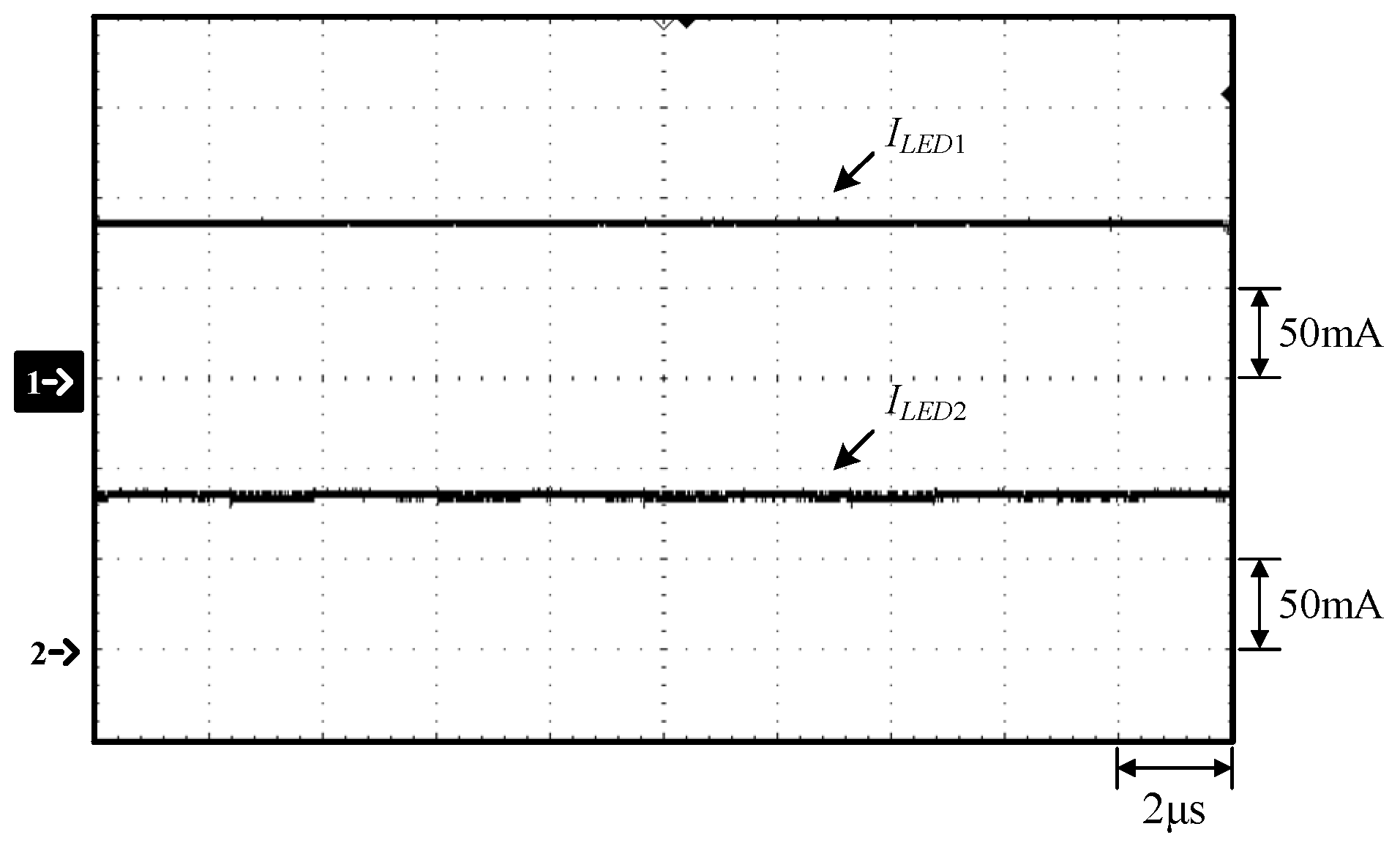

Figure 13.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) ILED1; (2) ILED2.

Figure 13.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) ILED1; (2) ILED2.

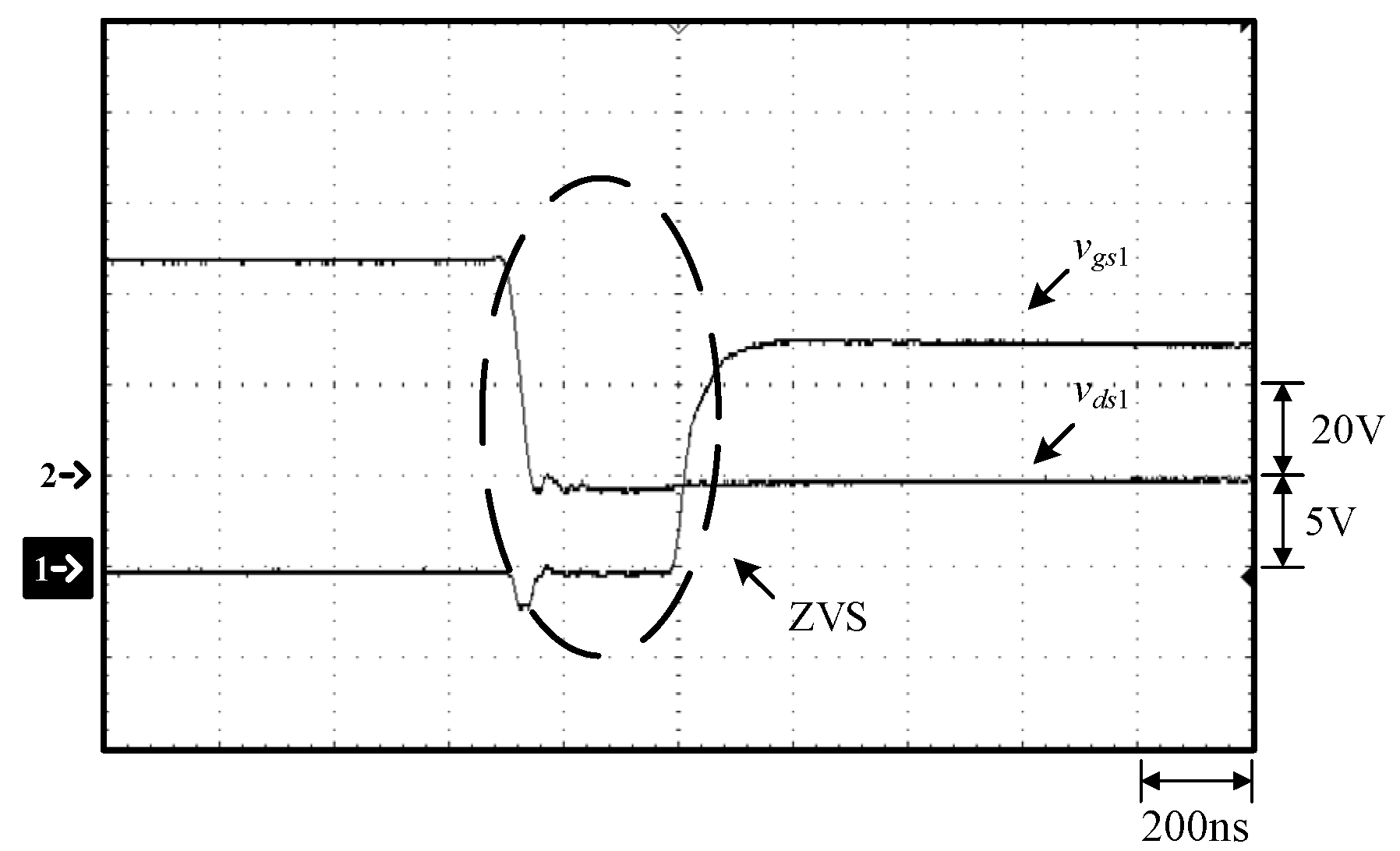

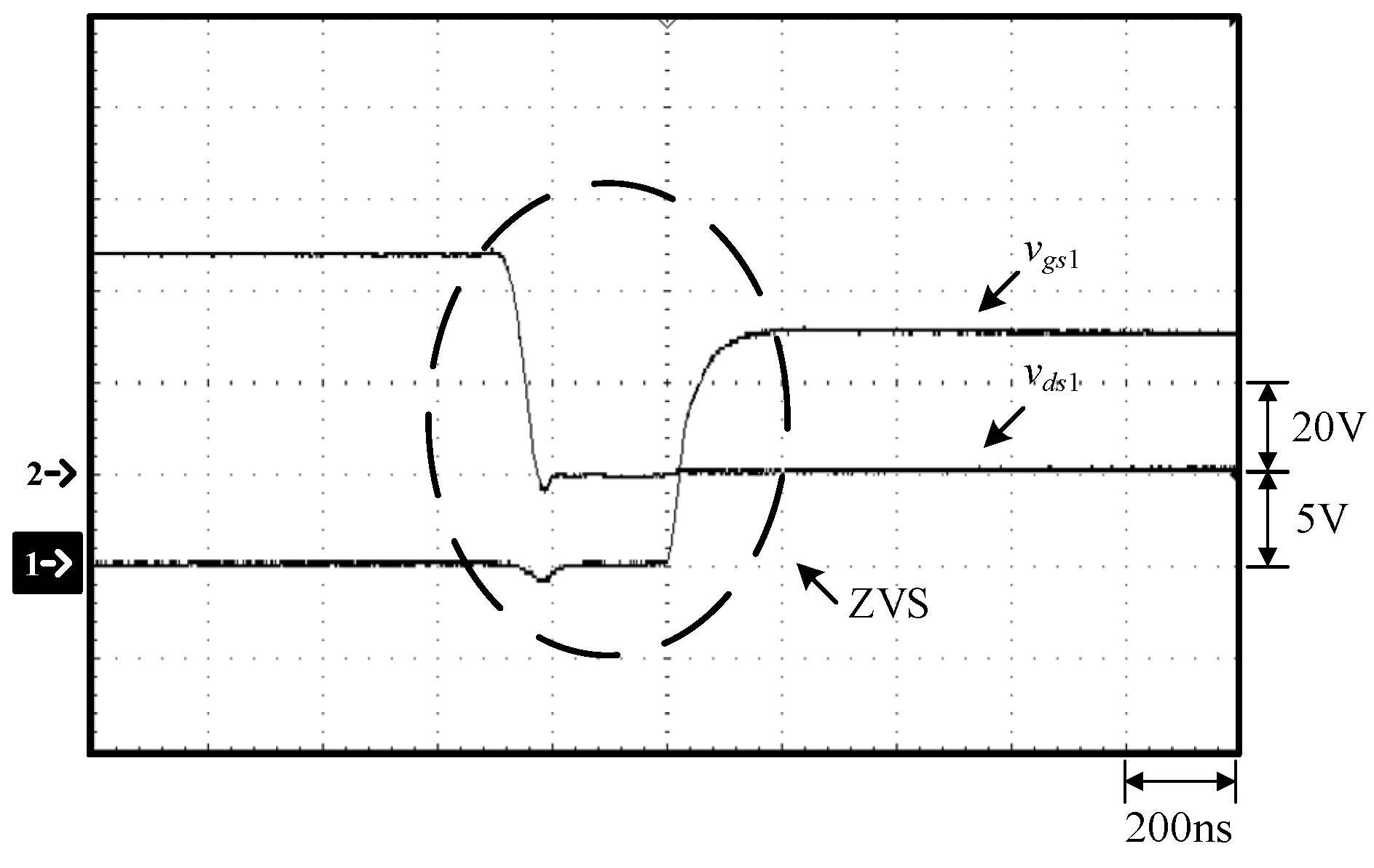

Figure 14.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1.

Figure 14.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1.

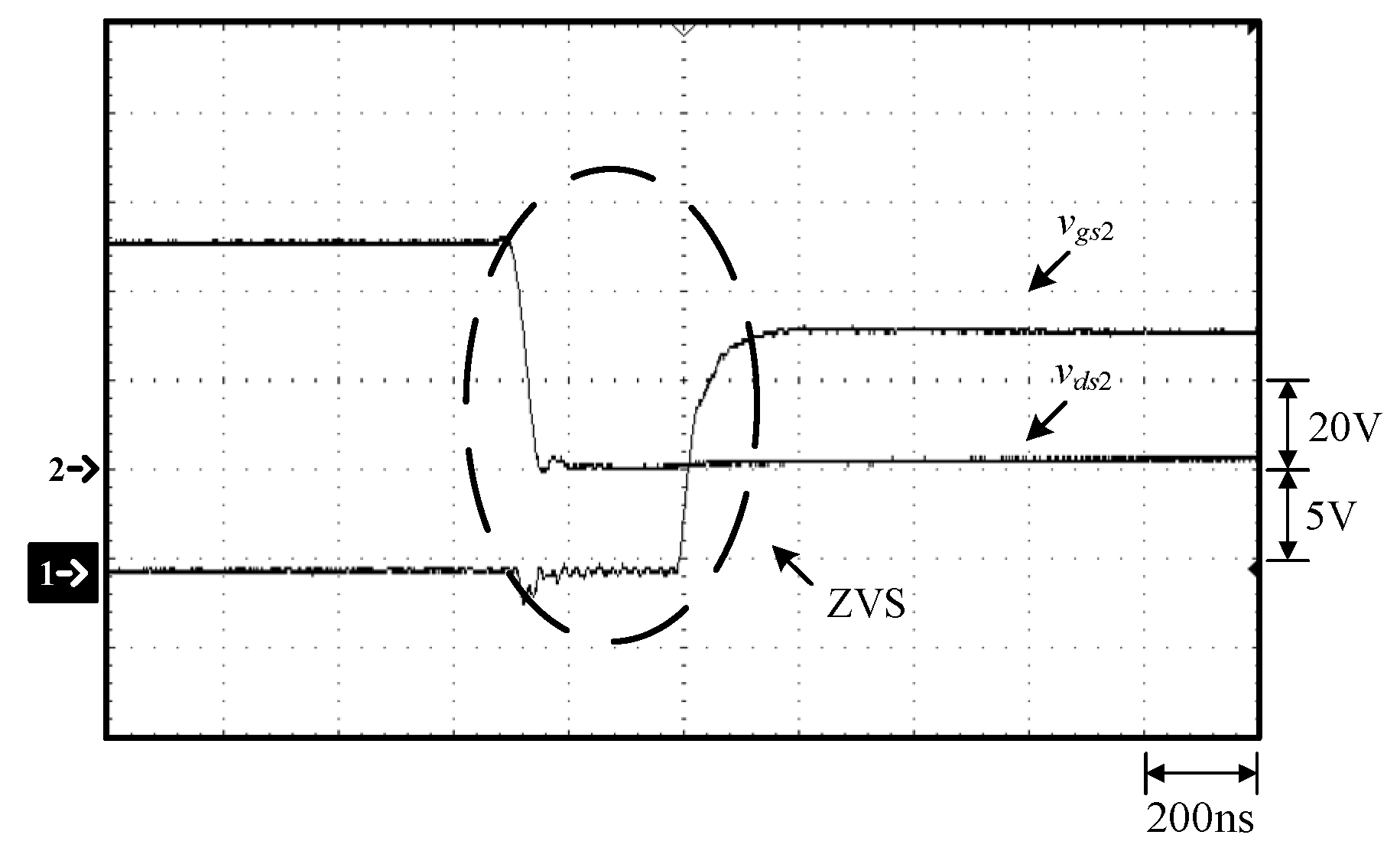

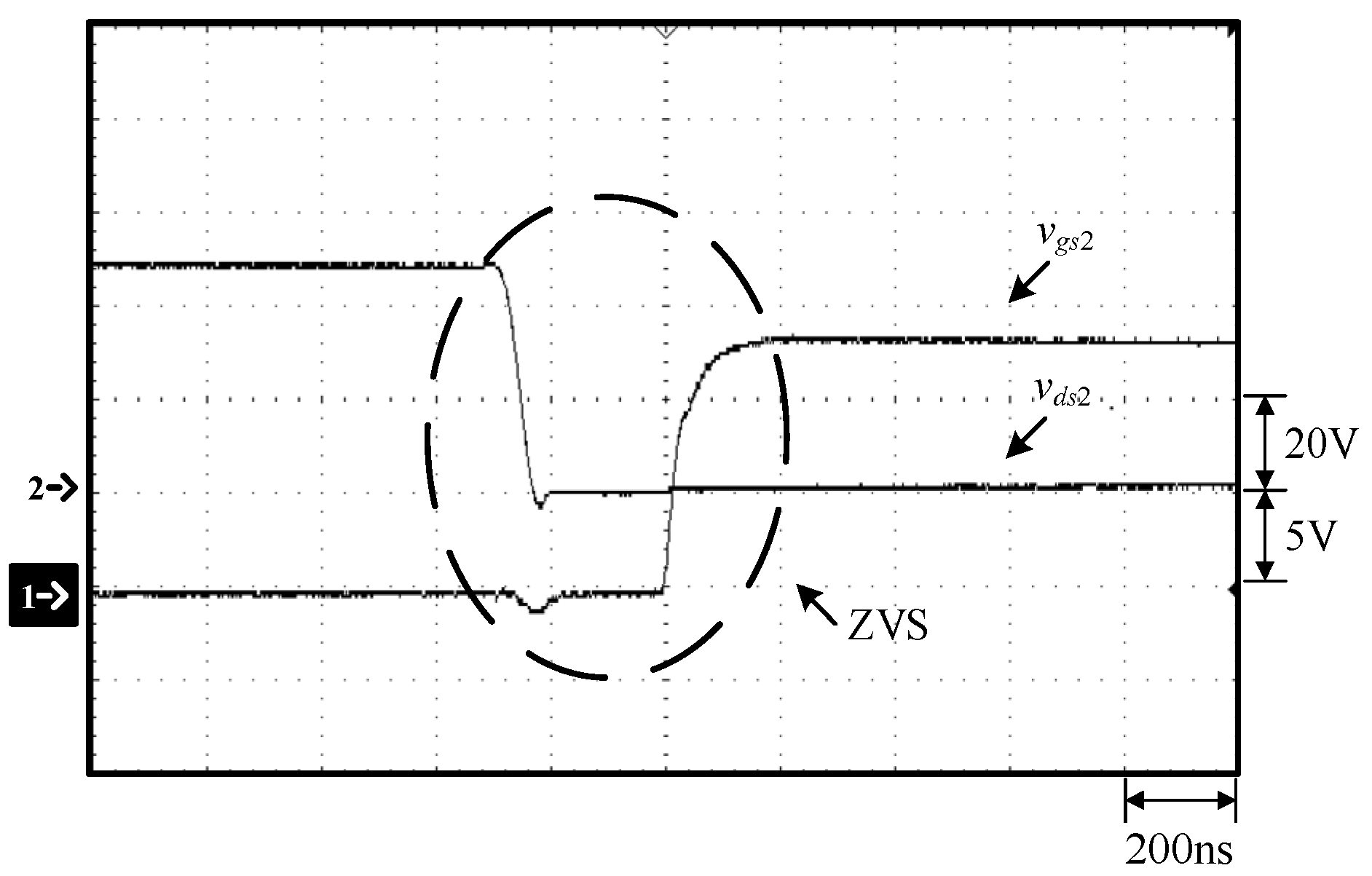

Figure 15.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs2; (2) vds2.

Figure 15.

Waveforms at 100% load: (1) vgs2; (2) vds2.

Figure 16.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1; (3) vgs2; (4) vds2.

Figure 16.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1; (3) vgs2; (4) vds2.

Figure 17.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vgs2; (3) iLr; (4) vCr.

Figure 17.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vgs2; (3) iLr; (4) vCr.

Figure 18.

Waveforms at 25% load: iLr; (2) iD1; (3) iD2; (4) iD3.

Figure 18.

Waveforms at 25% load: iLr; (2) iD1; (3) iD2; (4) iD3.

Figure 19.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) Vo1; (2) Vo2.

Figure 19.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) Vo1; (2) Vo2.

Figure 20.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) ILED1; (2) ILED2..

Figure 20.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) ILED1; (2) ILED2..

Figure 21.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1.

Figure 21.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs1; (2) vds1.

Figure 22.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs2; (2) vds2.

Figure 22.

Waveforms at 25% load: (1) vgs2; (2) vds2.

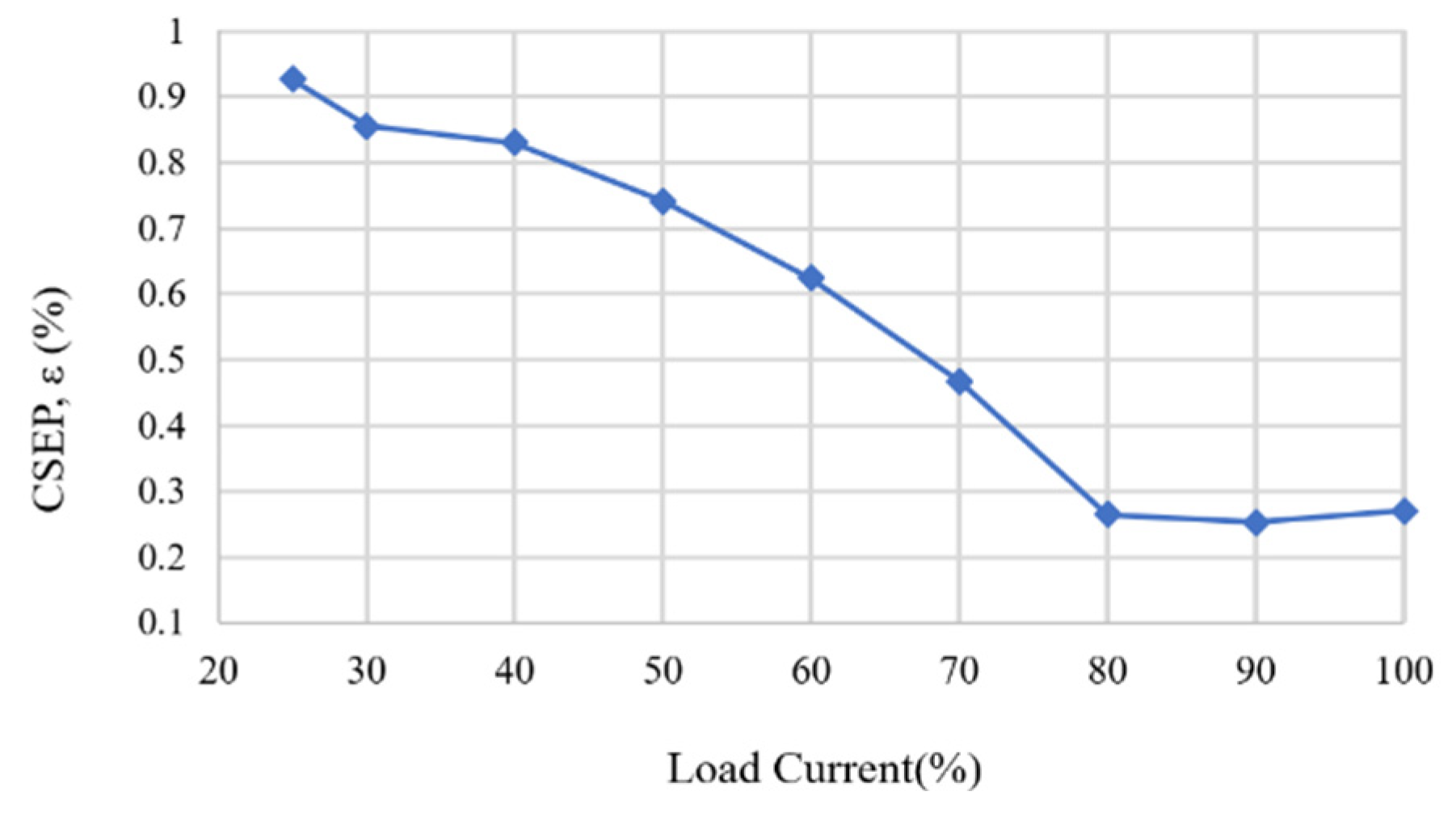

Figure 23.

Current sharing error percentage ε from 25% to 100% loads.

Figure 23.

Current sharing error percentage ε from 25% to 100% loads.

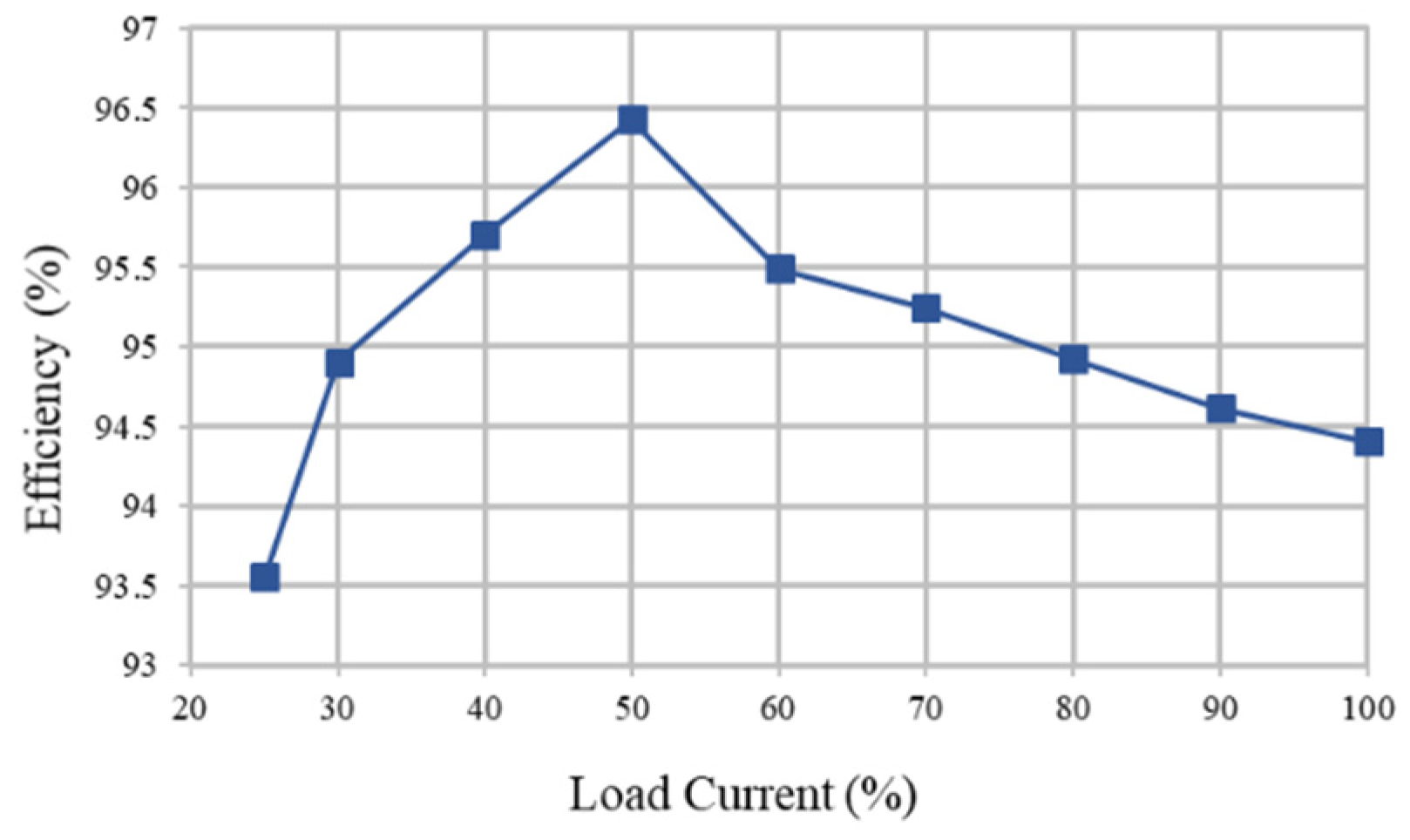

Figure 24.

Curve of efficiency versus load current.

Figure 24.

Curve of efficiency versus load current.

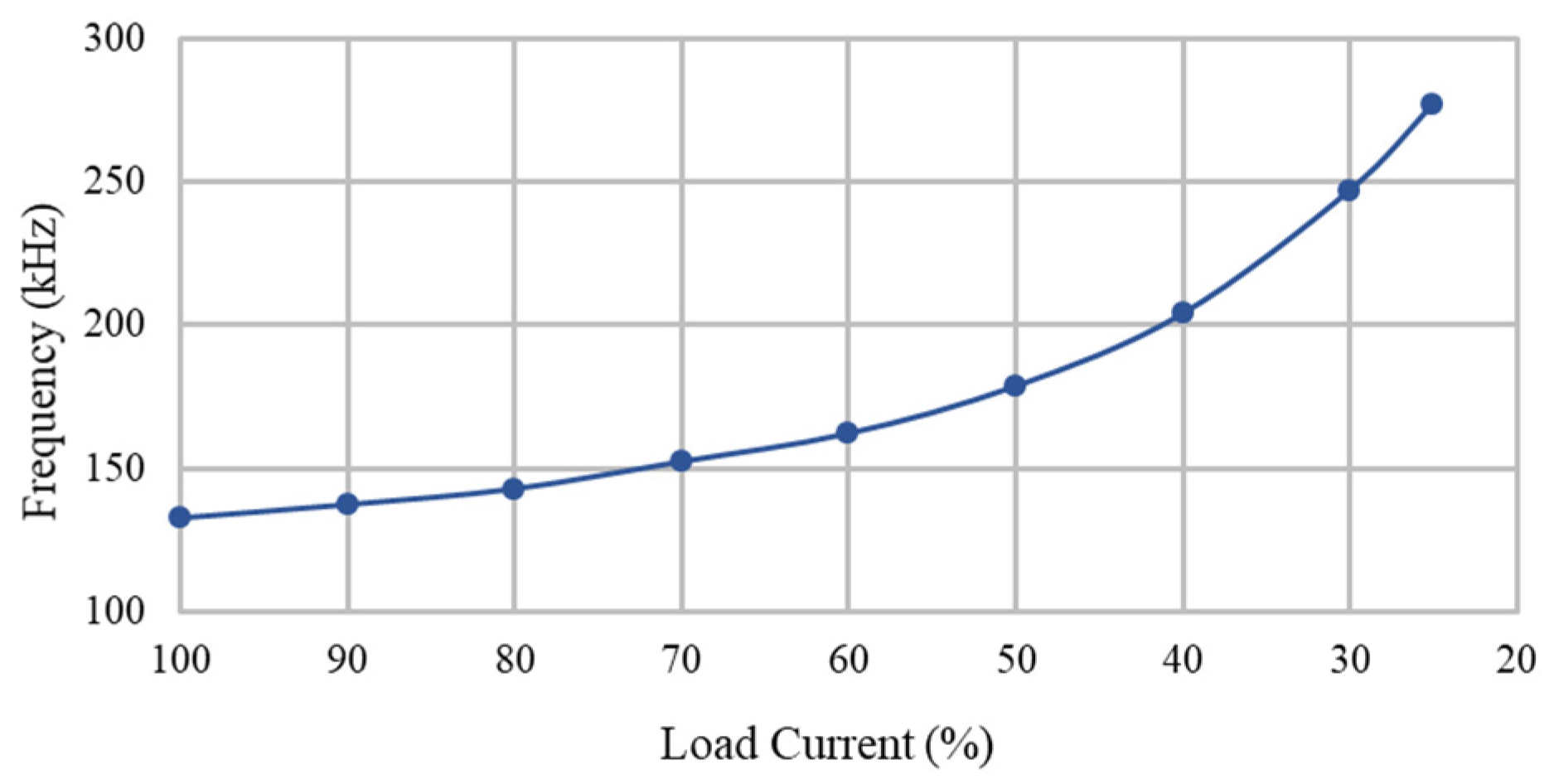

Figure 25.

Curve of switching frequency versus load current.

Figure 25.

Curve of switching frequency versus load current.

Table 1.

System specifications.

Table 1.

System specifications.

| Rated Input Voltage (Vin) |

48V |

| Rated Output Voltage (Vo,rated) |

32V (10 units in a string) |

| Rated Output Current (Io,rated) |

0.7A |

| Rated Output Power (Po,rated) |

22.4W (10LEDs,10LEDs) |

| Unbalanced Output Power (Po,unbalanced) |

20.16W (10 LEDs, 8LEDs) |

| Resonant Frequency (fr) |

100kHz |

| Quality Factor (Q) |

2 |

| Absolute current error percentage () |

<1% |

Table 2.

Measurement data at 100% load.

Table 2.

Measurement data at 100% load.

| |

LS1

|

LS2

|

|

ILED (mA) |

351.2 |

353.1 |

|

VLED (V) |

31.68 |

25.3 |

Table 3.

Measurement data at 25% load.

Table 3.

Measurement data at 25% load.

| |

LS1

|

LS2

|

|

ILED (mA) |

85.50 |

87.10 |

|

VLED (V) |

28.06 |

22.48 |

Table 4.

Comparison between the existing and proposed circuits.

Table 4.

Comparison between the existing and proposed circuits.

| |

[12] |

[13] |

[21] |

[14] |

Proposed

Circuit |

Number of

LED strings |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

Number of diodes for four

LED strings |

8 |

8 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

| Wide adjustable load range |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Current equalization method |

Transformer |

Transformer |

Transformer |

Transformer and Capacitor |

Transformer |

Number of transformers for four

LED strings |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

| Soft switching |

No |

No |

No |

ZVS |

ZVS |

Extension of the number of

LED strings |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |