1. Introduction

Current wireless technologies are mostly based on the Radio Frequency (RF) spectrum, with ubiquitous technologies such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and 5G. The current growth of new wirelessly connected devices is leading to stricter regulation and notable congestion of the RF spectrum [

1]. To mitigate the congestion, or find alternatives to the RF spectrum, researchers and industry have been examining new technologies and solutions to substitute or supplement the RF spectrum.

One of the most promising solutions is Visible Light Communication (VLC) [

2]. By taking advantage of widespread High-Brightness LED (HB-LED) based Solid-State Lighting (SSL), VLC uses HB-LED’s inherent capability for fast changes in its emitted light, which makes it suitable as a wireless transmitter. VLC is proposed as an alternative to the RF spectrum where such lighting is already present or where RF is not a viable option due to strict regulations (such as hospitals or aircraft, etc.) [

3,

4,

5].

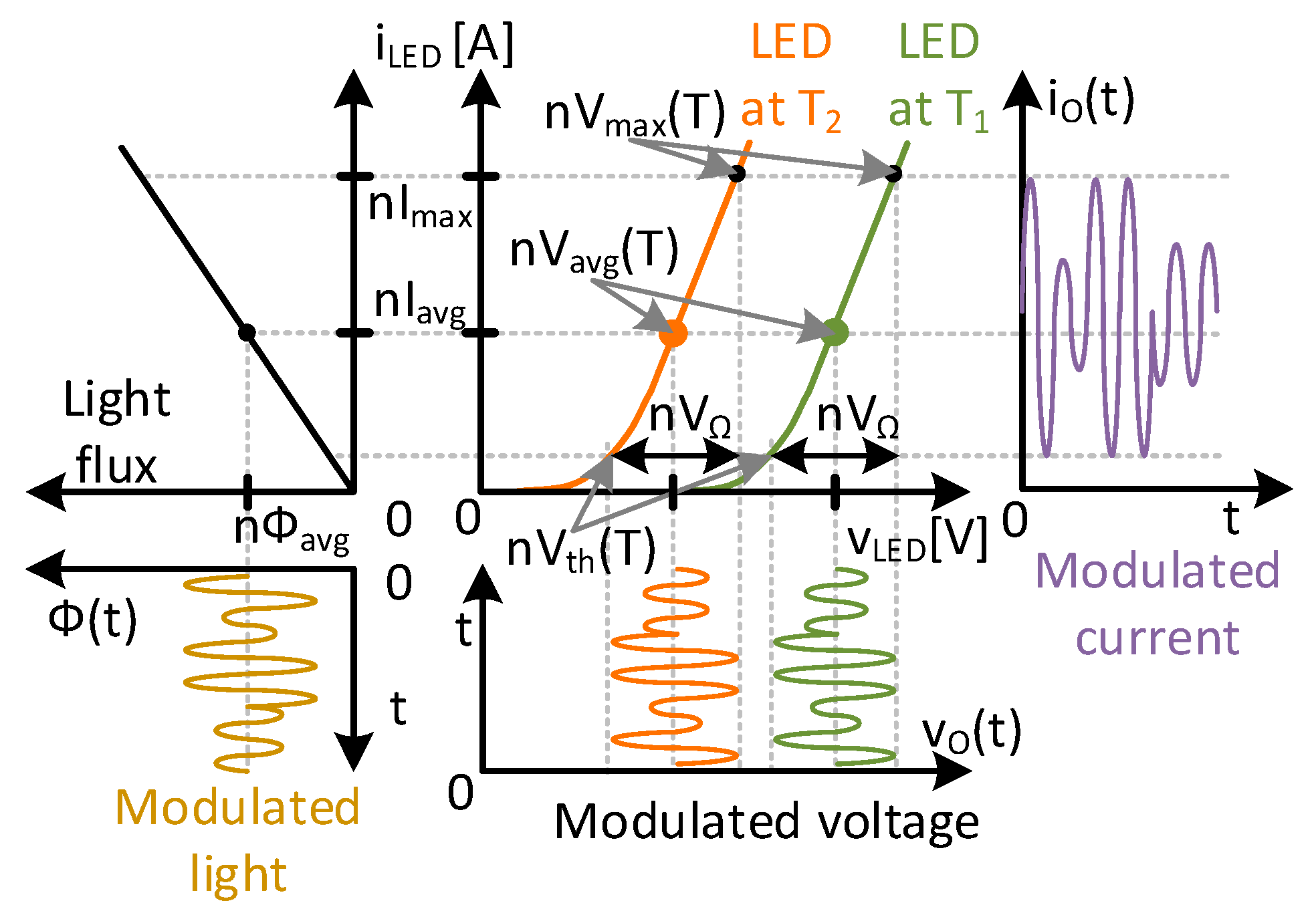

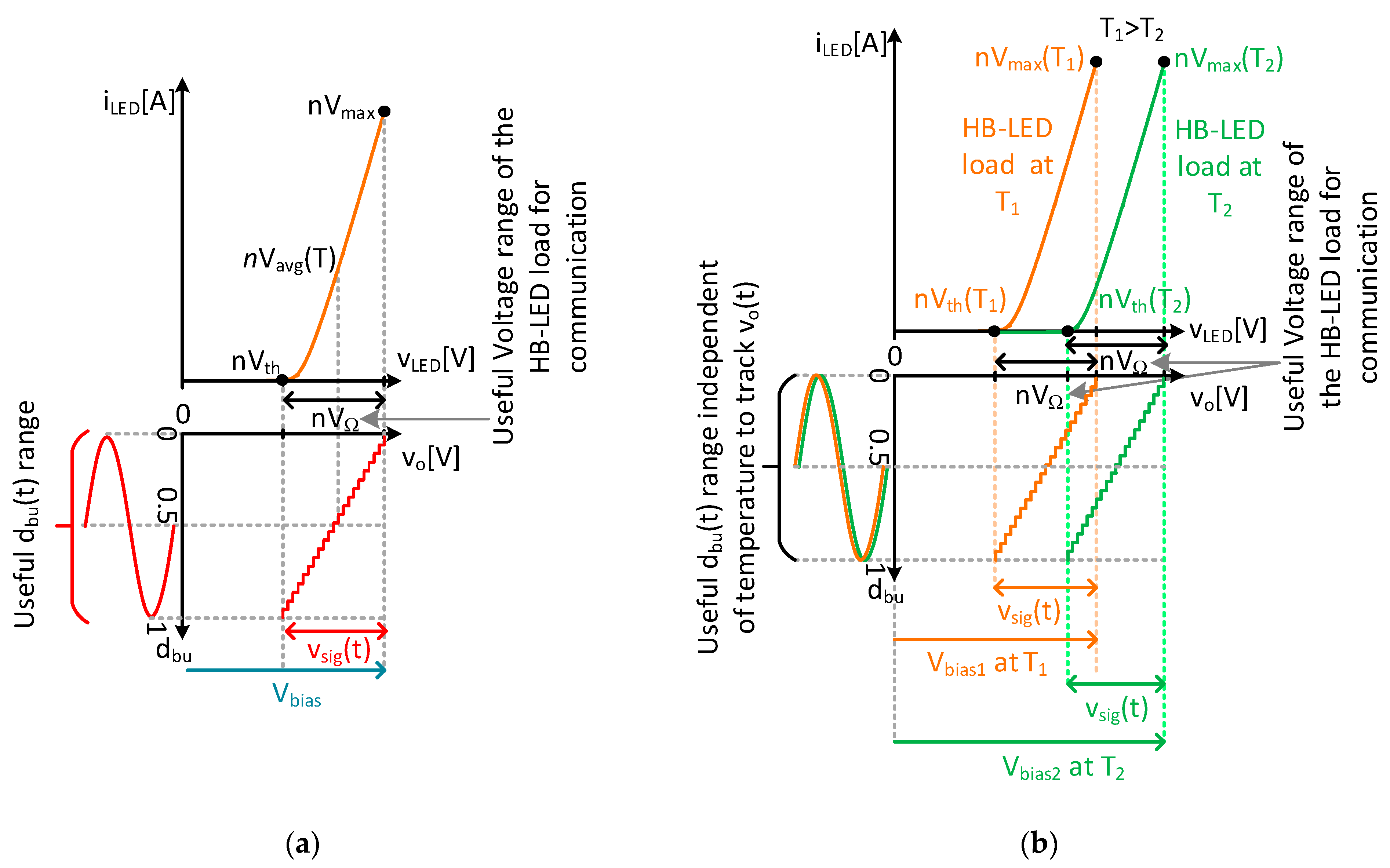

Figure 1 depicts the behaviour of a string of HB-LEDs and its control in a VLC system. A VLC system needs to accomplish two tasks: the bias task and the communication task.

The bias task generates a constant voltage across the HB-LED string, controlling the average current through the HB-LEDs, and then the light emitted by the HB-LEDs. As

Figure 1 shows, for a specific emitted light flux nϕ

avg and average current nI

avg, the voltage nV

avg(T) depends on the temperature T of the HB-LEDs due to the temperature shift. T

2 > T

1 when the HB-LEDs go from a lower temperature T

1 to a higher temperature T

2, the necessary nV

avg(T) decreases for the same current nI

avg. This undesired effect leads to the need for a control system for the LEDs. Without proper control to counteract this effect, communication performance is affected [

6]. In order to counteract the temperature shift, the driver has to control the average current in order to always be working in the middle of the LED’s linear region, which also maximizes the range for the communication signal, nV

Ω. The working range nV

Ω is defined as the linear part of the voltage-current relation, between the threshold voltage nV

th(T) and the maximum voltage nV

max(T).

The communication task is responsible for generating the communication signal within the working range nV

Ω. As

Figure 1 shows, the slope of the curve and the maximum HB-LED current are kept unmodified regardless of the temperature, meaning that the working range is also unchanged. Providing that the communication signal is lower than nV

Ω and the bias task works properly delivering nI

avg, distortion on the emitted light is minimized [

6].

The most common VLC HB-LED transmitter topology is based on using a regular HB-LED driver for the bias task connected to an amplifier (i.e. class A or B) for the communication task [

7,

8,

9], using a bias-T circuit. Even though they achieve high bit rates, the main drawback of this approach is power efficiency. For example, the maximum efficiency of class A and B amplifiers is 50% and 78% respectively (when a constant amplitude signal is delivered), but when a more complex amplitude modulated signal is used, the efficiency drops significantly [

10].

Another way to implement a VLC transmitter is to modify the traditional HB-LED driving stage by integrating the communication task, producing a VLC HB-LED driver. High frequency and fast response DC-DC converters have been proposed as a very promising alternative to linear amplifiers, achieving higher efficiencies (around 90%) and providing high bit rate communication [

11,

12,

13]. The main drawback of this approach is that the converter is processing both bias and communication power at high frequency, increasing total power losses. In a VLC system roughly 3/4 of the power comes from bias and 1/4 from communication. The bias task controls the current to adapt it according to the slow temperature effects over the HB-LEDs. This means that there is no need for the converter to have a fast response and therefore no need to have a high switching frequency. Thus, one way to further improve efficiency is by splitting the power in the converters depending on which part of the VLC HB-LED driver they are [

14,

15]. The idea involves making two specialized converters working together: a low frequency converter and a high frequency, fast output voltage response converter. The low frequency converter is responsible for delivering the bias power (most of the power in the system) and then maintaining the illumination at the desired level. In the other part, the high frequency, fast response converter is responsible for delivering a limited part of the power (mostly only the communication power). In [

14] two Buck DC/DC converters were used with their outputs connected in series for the HB-LED load: one low frequency converter for the bias task and a high frequency converter for the communication signal. Although the solution achieved high efficiency and communication capability, the main drawbacks of this approach are the need for two different input voltages, one for each converter, and one higher than the threshold voltage of the HB-LED load. In [

15] the need for two different input voltages was addressed by using two Buck DC/DC converters in a Two Input Buck (TIBuck) configuration, although the need for an input voltage higher than the HB-LED maximum voltage (due to the use of only Buck DC/DC converters) would not be suitable for battery powered VLC applications. Moreover, the TIBuck DC/DC converter suffers a reduction in its resolution for tracking the voltage across HB-LED load versus temperature changes.

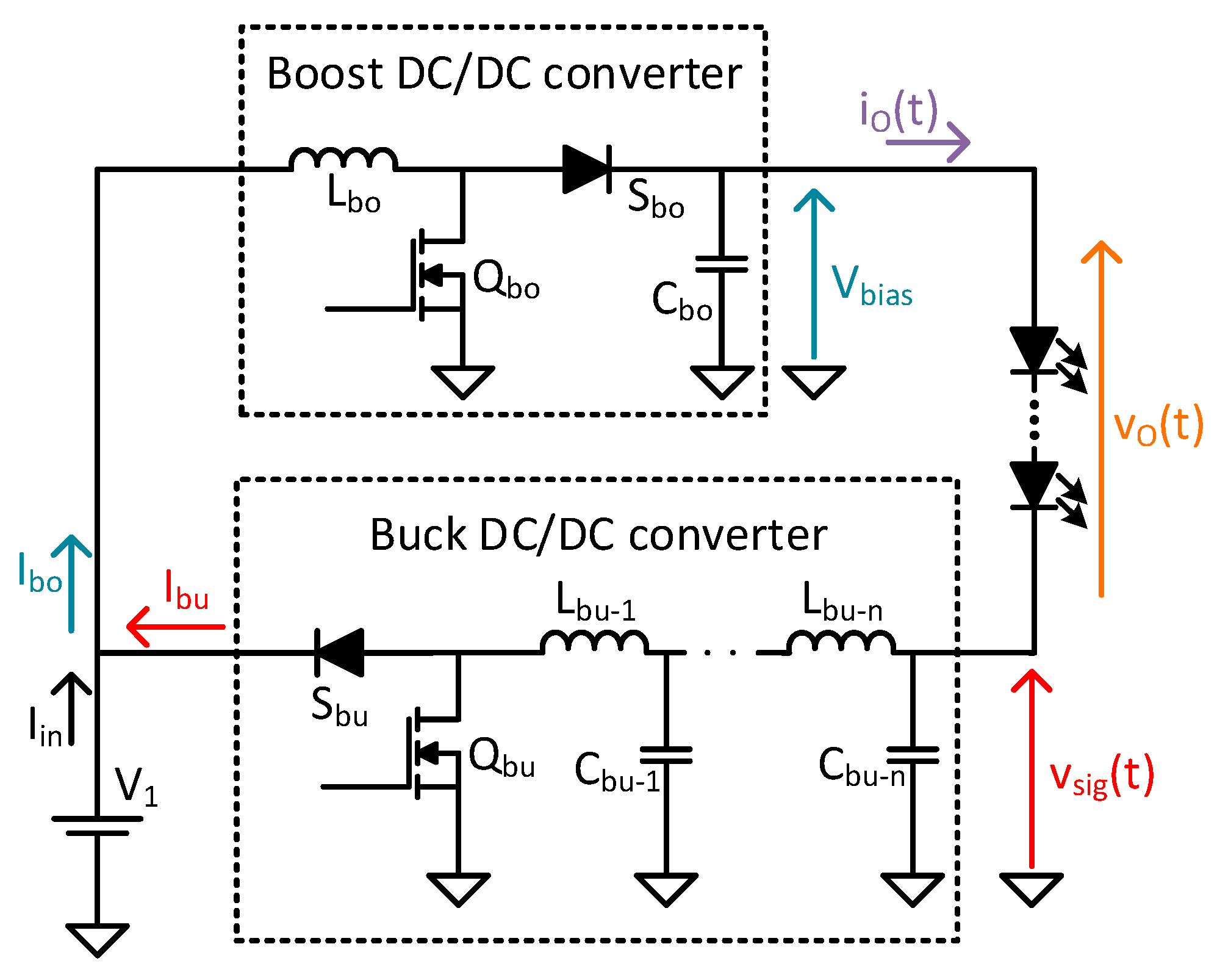

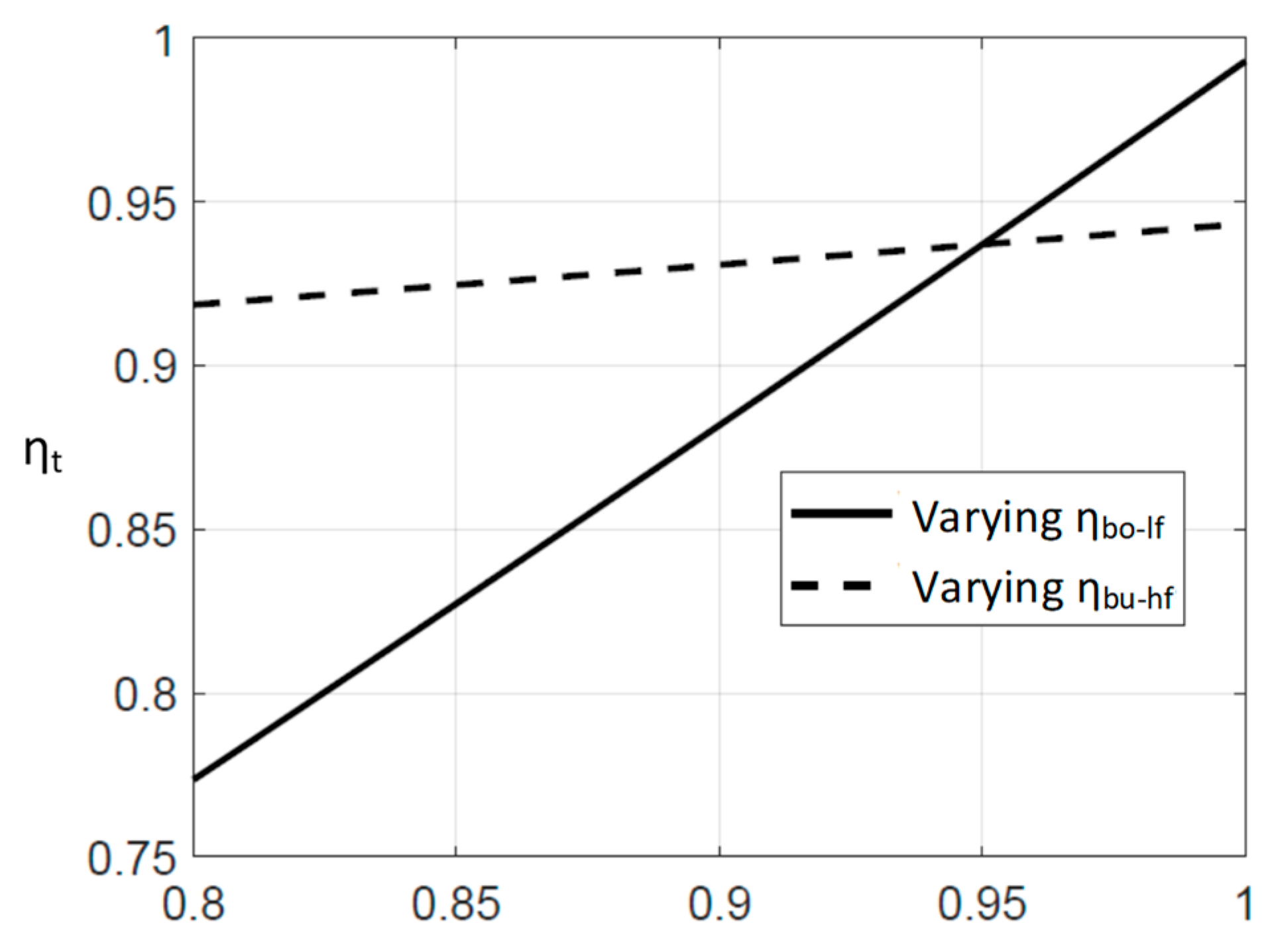

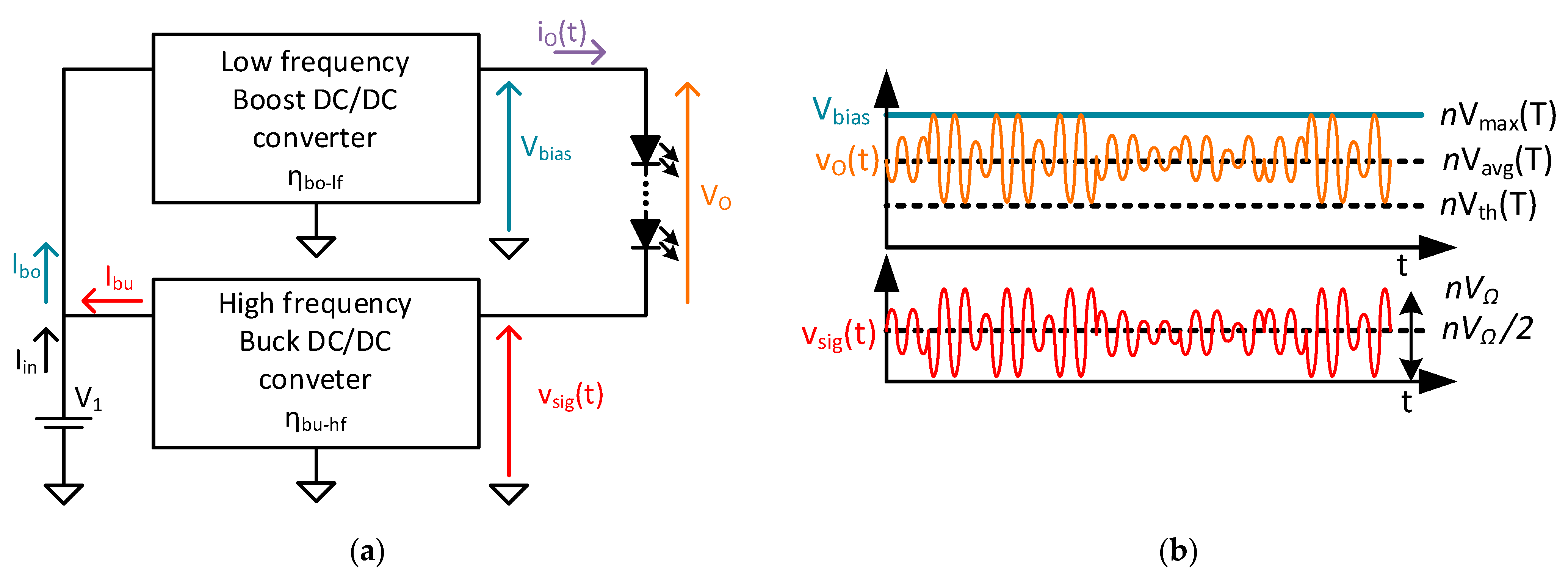

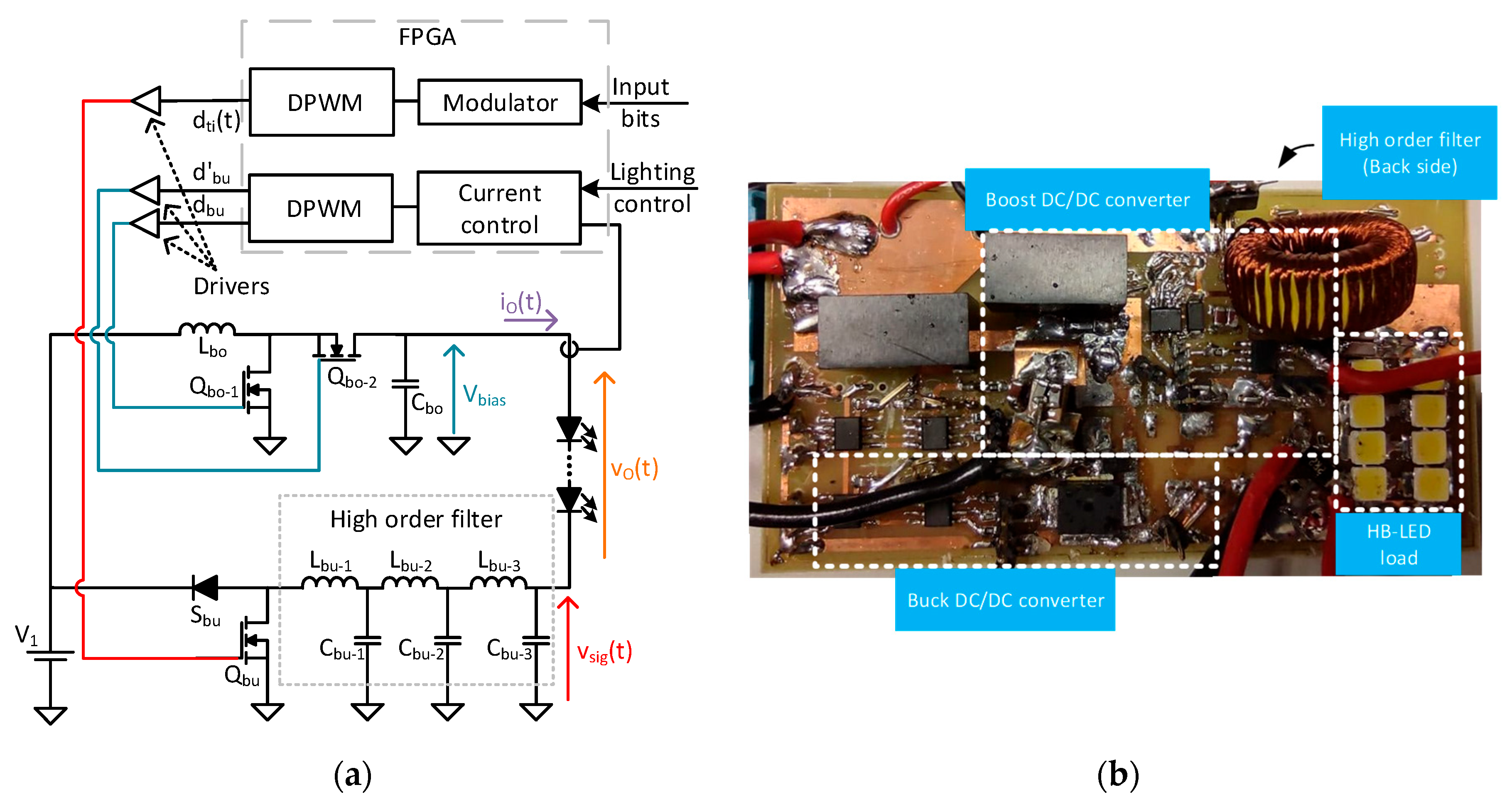

This paper presents a VLC HB-LED driver based on a low frequency Boost DC/DC converter and a high frequency Buck DC/DC converter, called a Series/Parallel Boost/Buck DC/DC converter. Both DC/DC converters share the same input voltage and are connected in series for the HB-LED load. The proposed topology achieves high efficiency and high communication performance by splitting the power between them. The low frequency Boost DC/DC converter is responsible for controlling the bias of the HB-LEDs, while the high frequency Buck DC/DC converter generates the communication signal. This technique allows most of the bias power to be processed by the low frequency converter (achieving high efficiency) and keeping the high frequency converter delivering the communication power (achieving high communication performance). This configuration follows the same principle as other split power proposals for VLC but without the need for two input voltages [

14], and without the inability to take advantage of the Buck DC/DC converter useful duty cycle range, which always provides the maximum resolution to the converter [

15].

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the analysis of the Series/Parallel Boost/Buck DC/DC converter, highlighting the main advantages over other topologies that use split power [

14,

15].

Section 3 describes the power flow between the two converters and an efficiency analysis. The experimental results are given in

Section 4, and finally, the conclusions are described in

Section 5.

4. Experimental Results

To provide experimental results, the proposed VLC HB-LED driver was built. The proposed converter is based on a low frequency Boost DC/DC converter and a high frequency Buck DC/DC converter sharing the same input voltage and connected in series in relation to the HB-LED load (

Figure 6).

The HB-LED load is a string of 8 XLamp MX-3 HB-LEDs, with an output power around 8 W. The current and voltage necessary for the HB-load can be obtained from the datasheet of the XLamp MX- 3 LED used [

16]. A string of 8 XLamp MX-3 HB-LEDs has a maximum voltage of 32 V (4 V for a single LED) and a current of 0.25 A in the middle of the linear region. The working range is nV

Ω= 8 V (1 V for a single LED). The input voltage used was V

1 = n nV

Ω = 8 V. As previously explained, this value of input voltage maximizes the resolution for tracking the output voltage for communication tasks.

The average current through the HB-LEDs was kept at 0.25 A (in the middle of the linear region) and the overall efficiency achieved was 91.5%. Efficiency was measured by comparing the DC input power to the RMS output power (taking into account biasing and communication power) on the HB-LED load.

A Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) (Nexys A7) was used both to control the Buck DC/DC converter and the Boost DC/DC converter using a Digital Pulse Width Modulator (DPWM). The FPGA controls the Boost DC/DC converter in order to control the average value of the current through the HB-LED load (i.e., controlling Vbias value using a control loop). The FPGA also controls the Buck DC/DC converter operating at high frequency in order to send information (i.e., reproducing the input bits at its output).

4.1. Effiuciency Analysis

The low frequency boost DC/DC converter is designed to work as a traditional HB- LED driver with a switching frequency of 100 kHz, working in a closed loop. It is responsible for increasing the dc output voltage up to the maximum voltage allowed across the LED. It also implements the bias current loop control of the LED string. Due to the low dynamic behaviour of the temperature shift in the LEDs, there is no need for the converter to have a fast output dynamic response. There needs to be a trade-off with regard to the switching frequency: increasing the switching frequency allows the reactive elements of the converter to be reduced (especially interesting in small applications), but it increases power losses and the effect of switching noise on communication (if this noise is within the communication band). The noise is produced by the output voltage ripple on the output boost capacitor C

bo. Using (10), the boost output ripple is limited to a maximum of 2% of the output boost voltage. The final values of the reactive elements of this converter are shown in

Table 1.

In this equation, ΔQ is the total charge of the capacitor and D

bo and T

bo are the duty cycle and the time period of the boost DC/DC converter. A current control was implemented so that the boost DC/DC converter could control the I

o current. The current was measured by means of an isolated current shunt, connected in series to the LED string. The current control included a low pass filter which eliminates the communication components in the HB-LED current and a PI controller. No new considerations are needed with regard to the PI controller in this implementation, and a standard current controller for HB-LED can be used. Both the PWM modulation and the current control were implemented in a FPGA Nexys A7, as noted previously. The remaining component selection was as follows: the dual CSD88539 MOSFET was used for Q

1bo and Q

2bo; an ISL6700 half bridge driver was used for the driving stage. The complete list of components are summarized in

Table 2.

4.2. Effiuciency Analysis

The converter reproduces a 64-QAM modulation, with a carrier frequency fsig of 1 MHz. The symbol period is equal to four signal periods, achieving a maximum bit rate of 1.5 Mbps. In order to avoid any switching noise coming from the Boost DC/DC converter, the signal frequency was selected a decade higher than the Boost DC/DC converter switching frequency.

4.3. High Frequency and Fast Response Buck DC/DC Converter Design

The high frequency Buck DC/DC converter is responsible for generating the communication signal as mentioned previously. This converter works in an open loop and includes a high order output filter to achieve high bandwidth and a fast response. To properly reproduce a communication signal by means of a Buck DC/DC converter, the inequation

relating to the carrier frequency f

sig, the cut-off frequency of the filter f

cut, and the Buck DC/DC converter switching frequency f

bu, must be applied. The exact relation between the frequencies and the order and attenuation of the filter was analysed in [

17]. Based on this analysis, the output filter used a 6

th low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency f

cut of 2.5 MHz. The reactive components of the filter are shown in

Table 2. The switching frequency f

bu used was 10 MHz

Due to the high switching frequency of the Buck DC/DC converter, two RF high frequency PD84010-E MOSFETs were used for Q1bu and Q2bu in parallel with two high speed Schottky UPS115UE3 diodes. For the driving stage two high speed EL7155CSZ drivers were used.

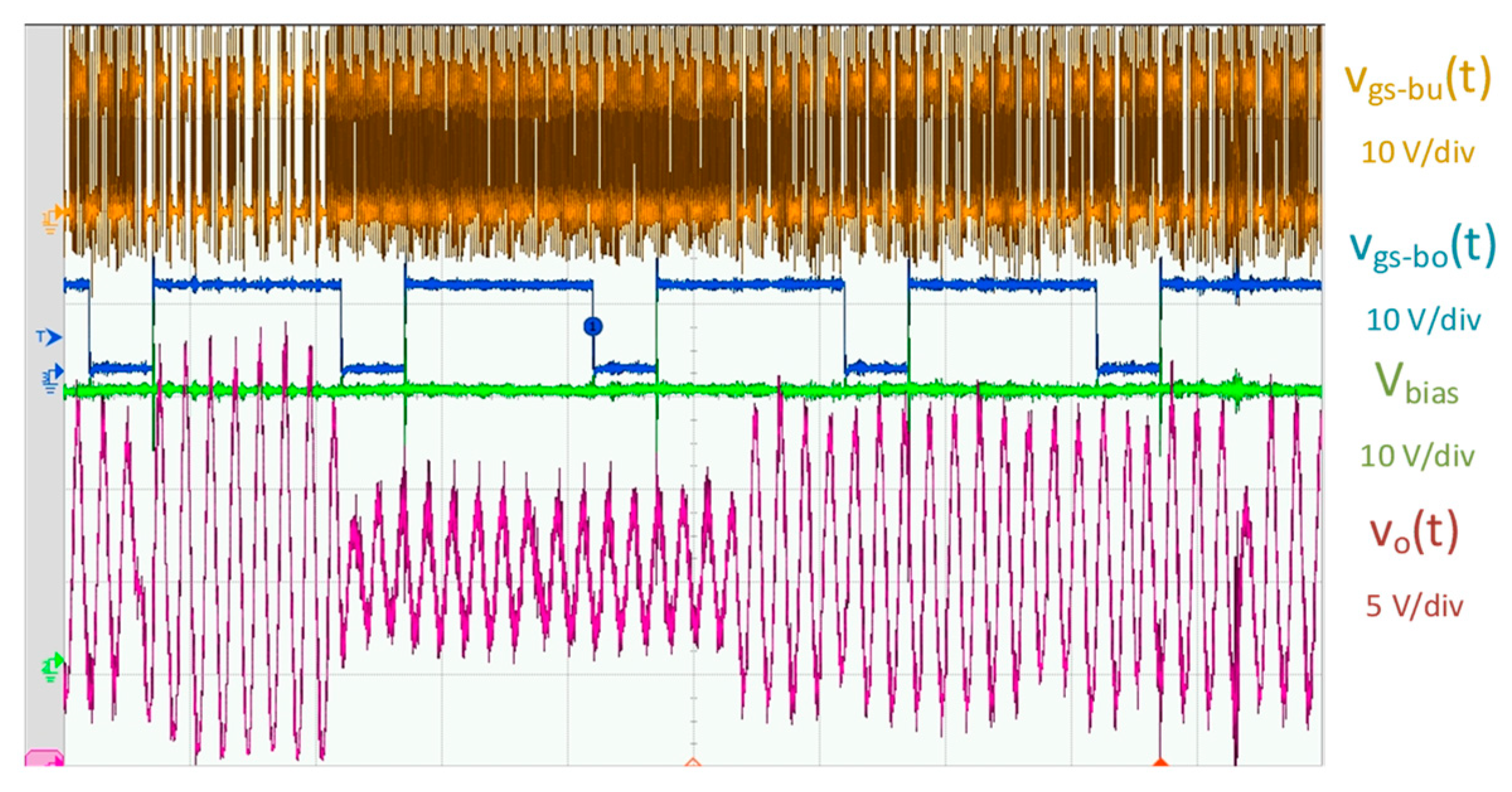

4.4. Experimental Results for Communication

Figure 7 shows some of the most representative waveforms of the DC/DC converters. The signals v

gs-bot and v

gs-bu are the gate-to-source signals of the Boost and Buck DC/DC converters respectively. The difference in frequency between these two signals is notable, v

gs-bot is a 100 kHz PWM signal, while v

gs-bu is a 10 MHz PWM signal. The signals V

bias and v

sig(t) are the output voltage of the Boost and Buck DC/DC converters respectively. As shown, the output voltage of the Boost DC/DC converter is kept constant (and with low ripple) and the current loop control varies the duty cycle of the signal v

gs-bot in order to keep the average output current constant through the HB-LEDs, at the design level of 0.25 A. Without considering any temperature shift over the HB-LED, the input voltage of the Boost DC/DC converter should be 32 V, which is the maximum HB-LED voltage of the 8 LED string used. After a few minutes, when the LED temperature is stabilized, the current control loop of the boost dc-dc converter reduces V

bias by 21% to 25 V.

The Buck DC/DC converter works in an open loop reproducing the communication signal. The variation of the duty cycle in vgs-bu can be seen, along with the effect over the output voltage vo(t). The peak to peak voltage of the Buck DC/DC converter is 7.5 V, closer to the maximum working range of the 8 HB-LED string, which is 8 V. The output Buck DC/DC converter filter is able to filter the high switching frequency of the converter and allows the communication signal to pass through. The correct design of this filter must take into account the correct reproduction of the sine carrier frequency of the modulation and the correct change in phase and amplitude between symbols.

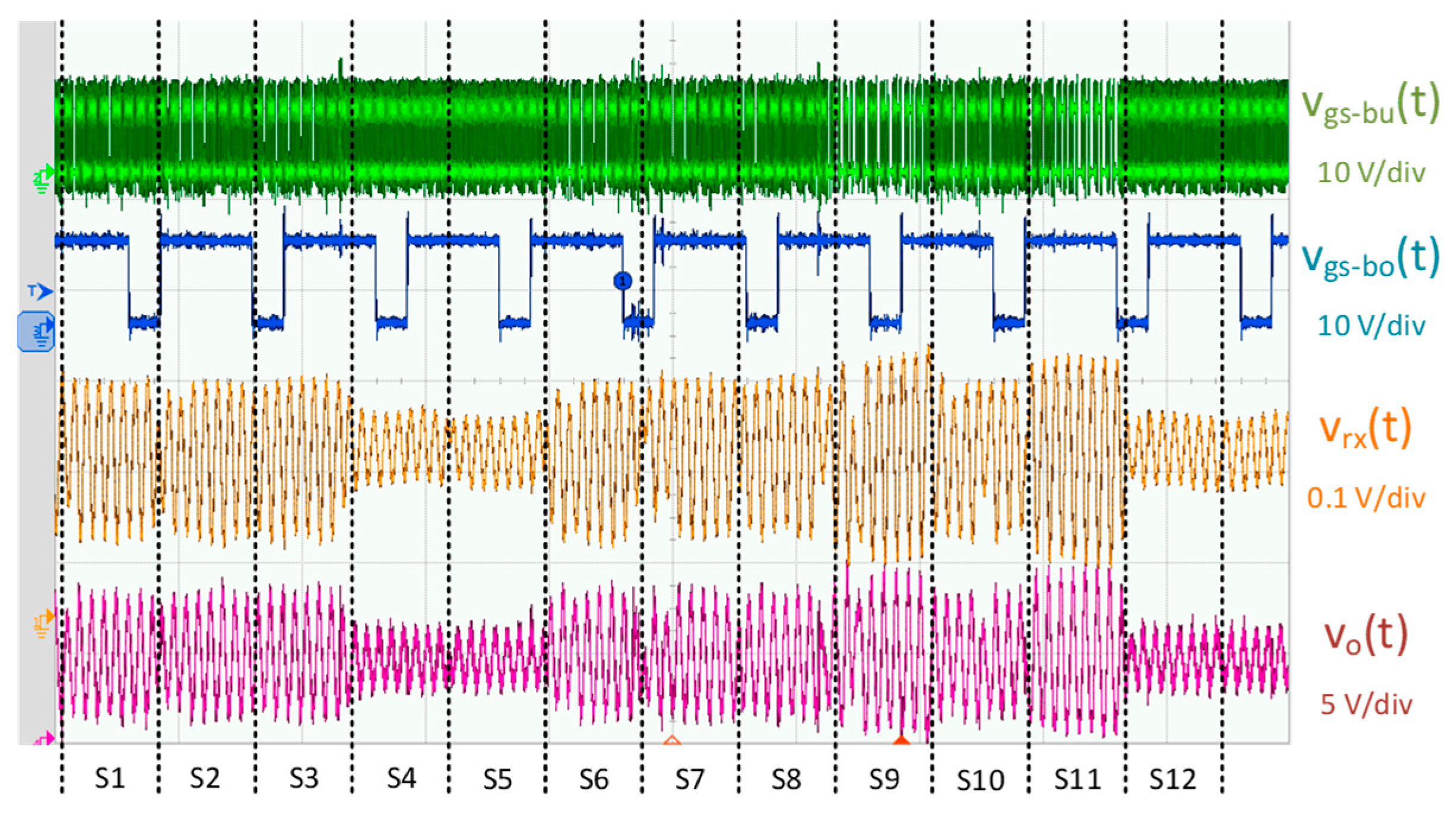

In order to focus the analysis on the converter’s communication task, a longer period of time is shown in

Figure 8. Thus to test the communication performance, the communication signal generated by the Buck DC/DC converter v

sig(t) and the light emitted by the HB-LEDs were measured during transmission of 12 different symbols. To properly measure the light, a Thorlabs PDA10A-EC [

18] high bandwidth optical receiver was used, placed in front of the HB-LED string, giving an output voltage v

rx(t) proportional to the light. Comparing the two signals v

o(t) and v

rx(t) shows that the converter was able to properly reproduce the communication signal without distortion. Distortion could occur due to temperature shifts in the HB-LEDs by making the HB_LED work outside its linear region. Comparing the v

o(t) and its received light signal v

rx(t) indicates that this undesired effect was avoided due to proper current loop control.

In terms of efficiency, the experimental results were gathered using 34461A Digital Multimeterers and indicated an efficiency of 91.5% reproducing a 64-QAM digital modulation, with a bit rate of 1.5 Mbps