Submitted:

26 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

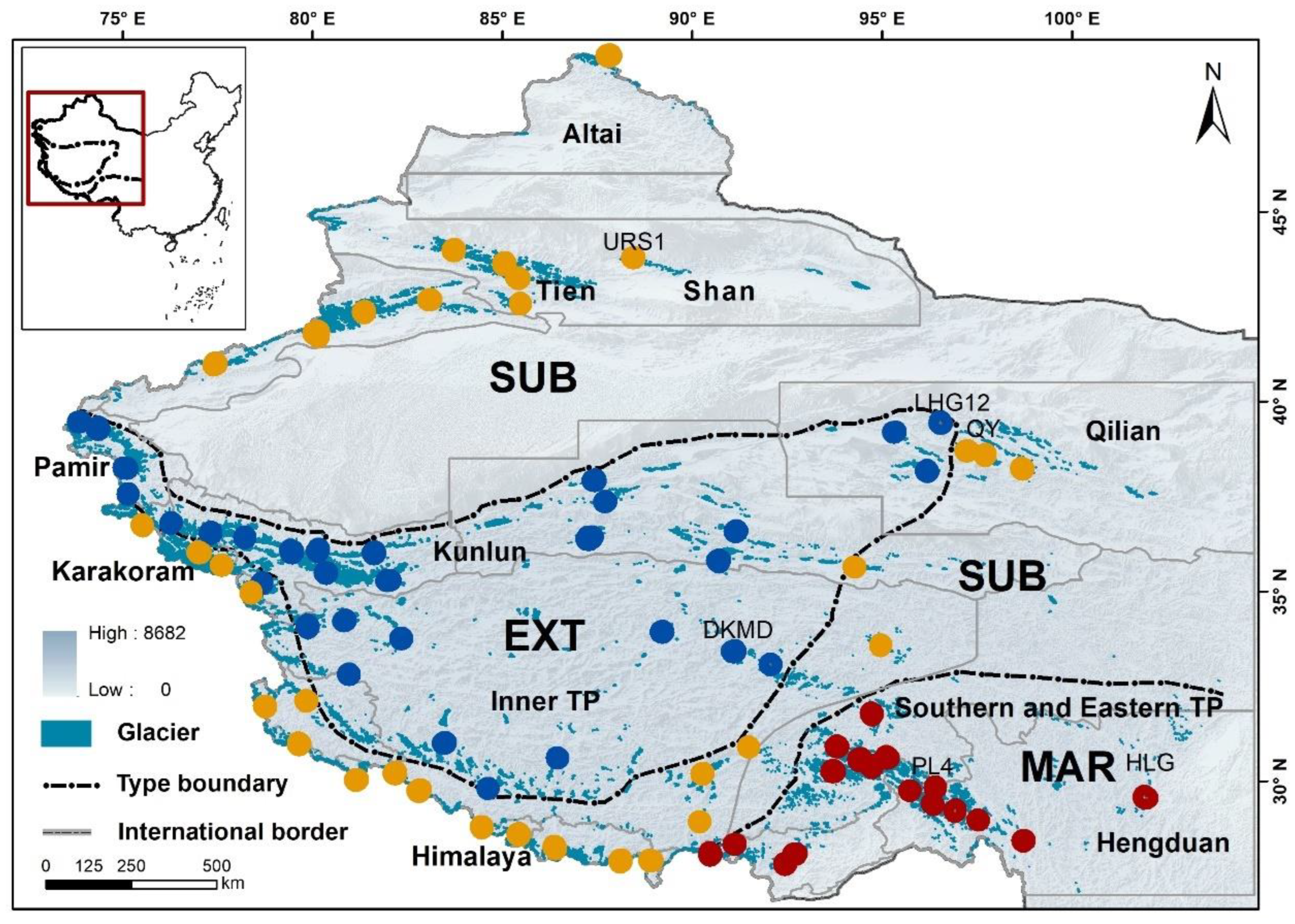

2. Study Glaciers

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Shi-Xie Classification Method

3.2. Glacier Outlines

3.3. DEMs

3.4. Equilibrium Line Altitude

3.5. Meteorological Data at ELA

3.6. Near-Surface Ice Temperature

3.7. Glacier Surface Velocities

4. Results

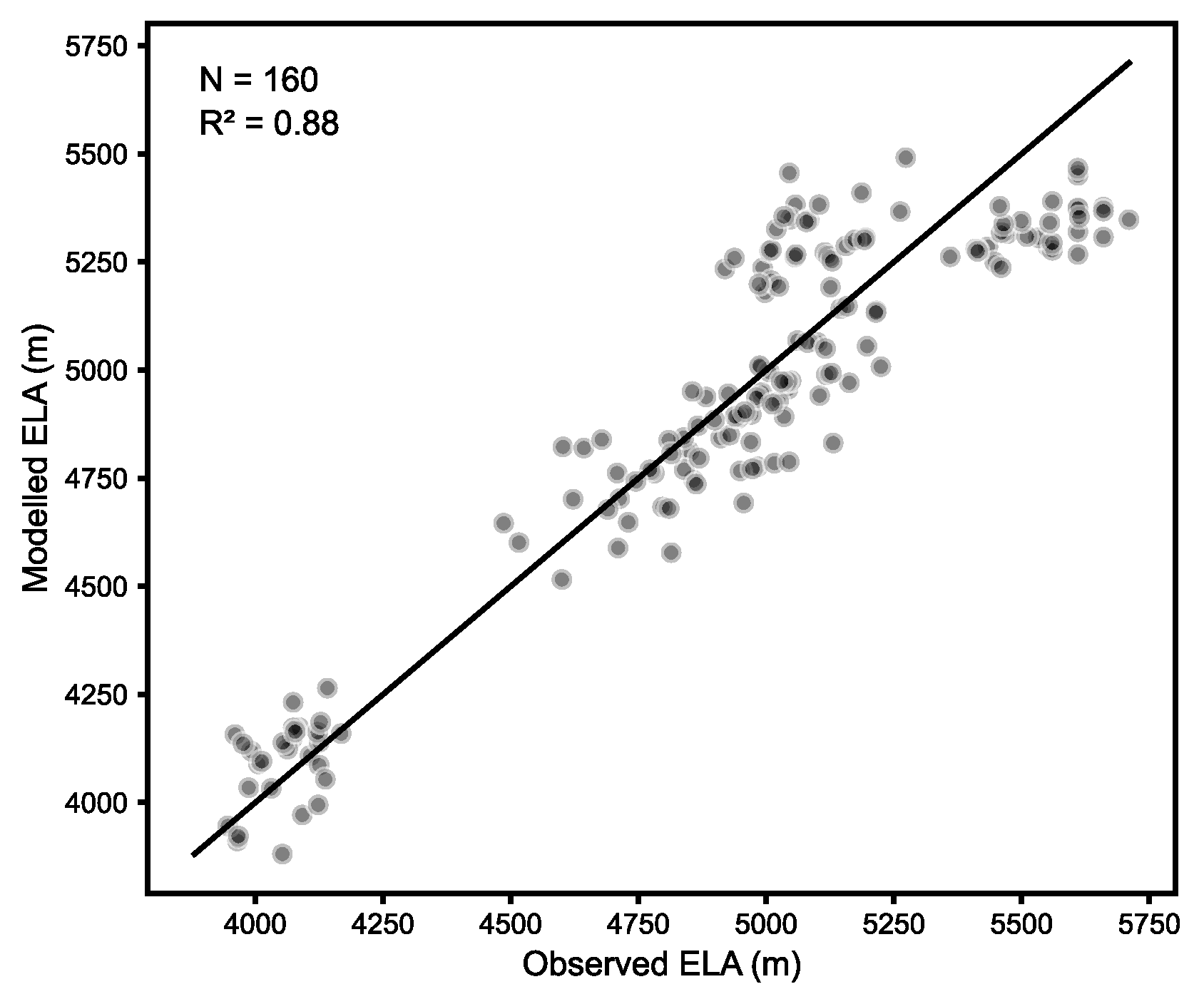

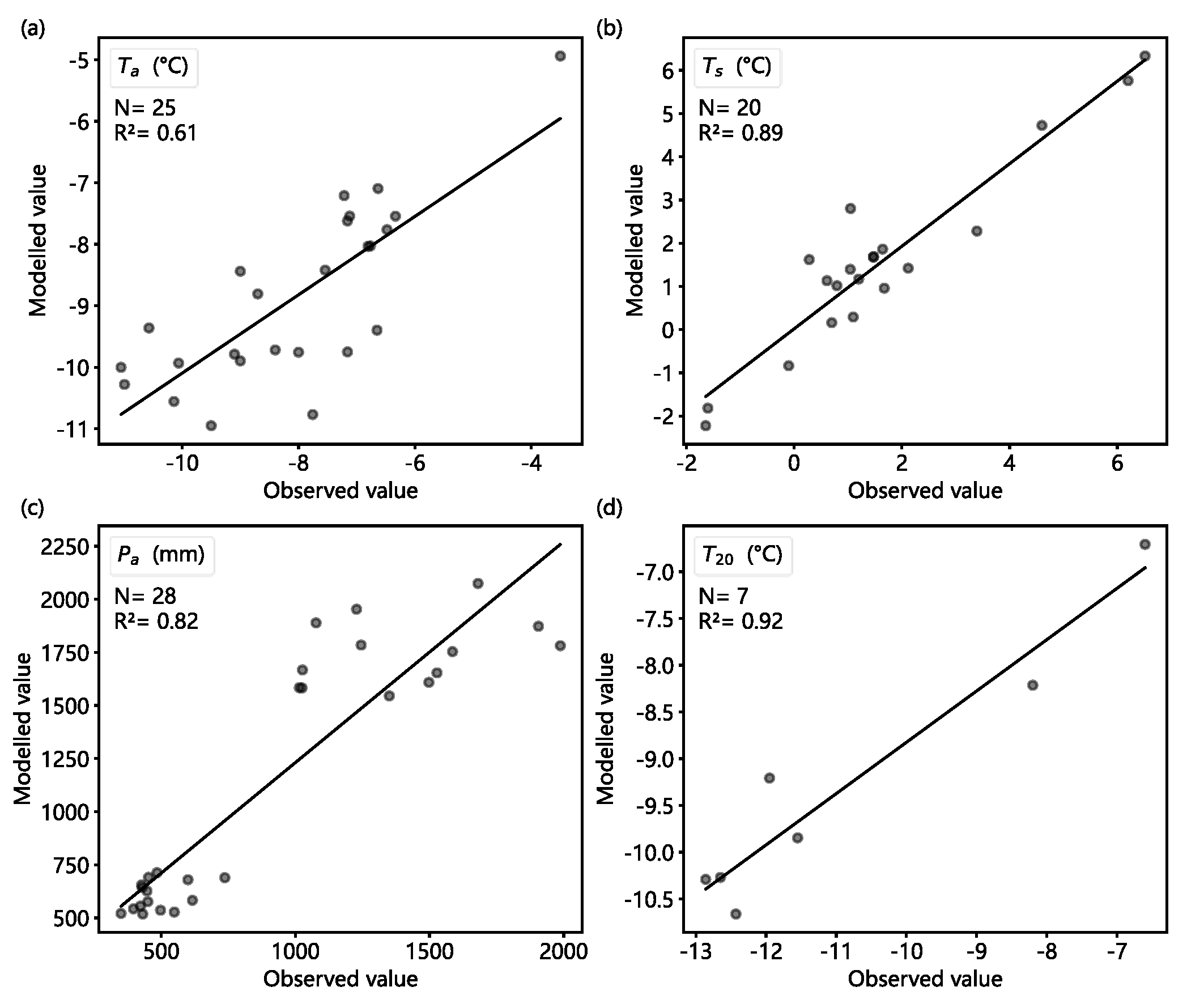

4.1. Calibration and Validation

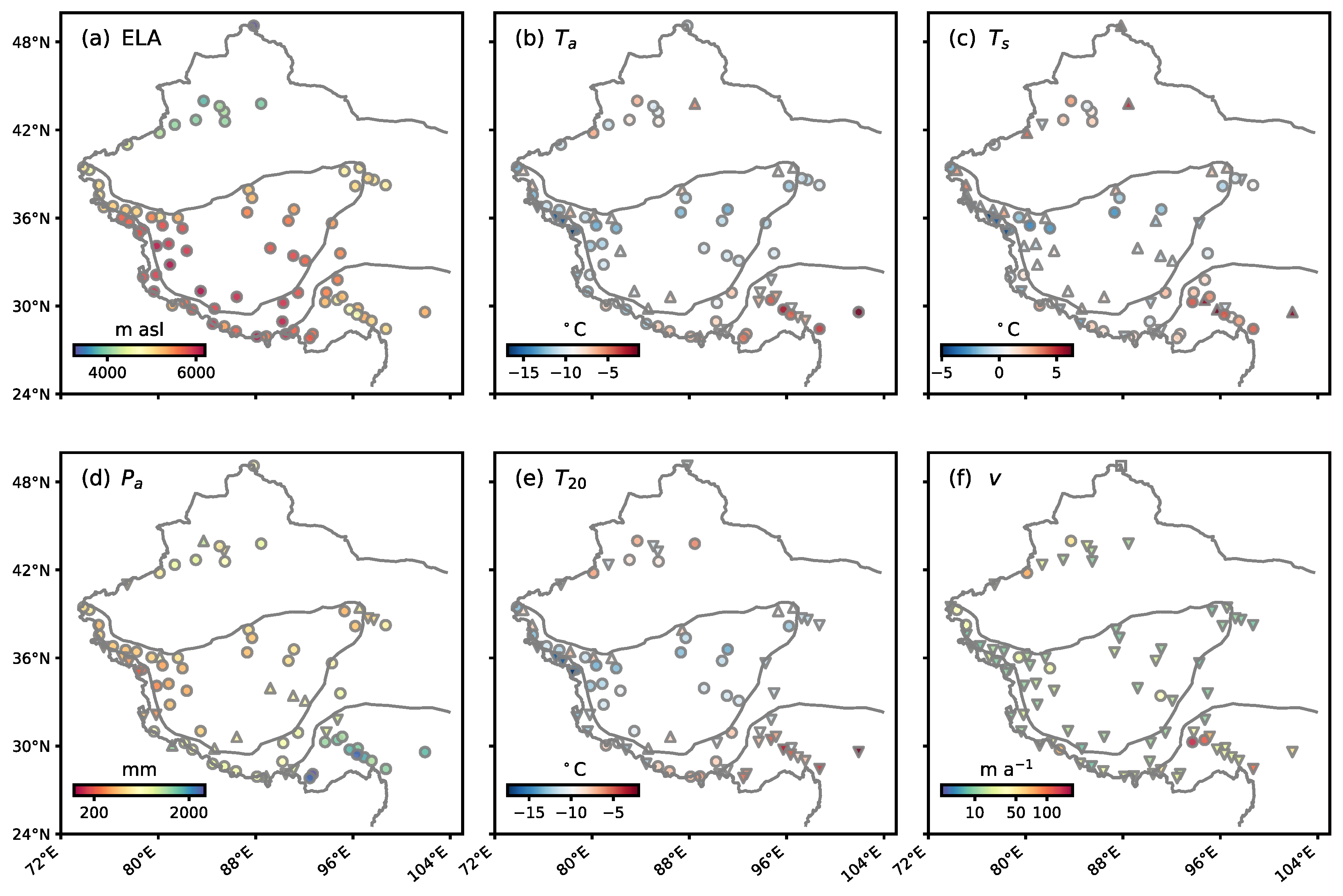

4.2. Spatiotemporal Distribution of ELAs and Glacier Criteria

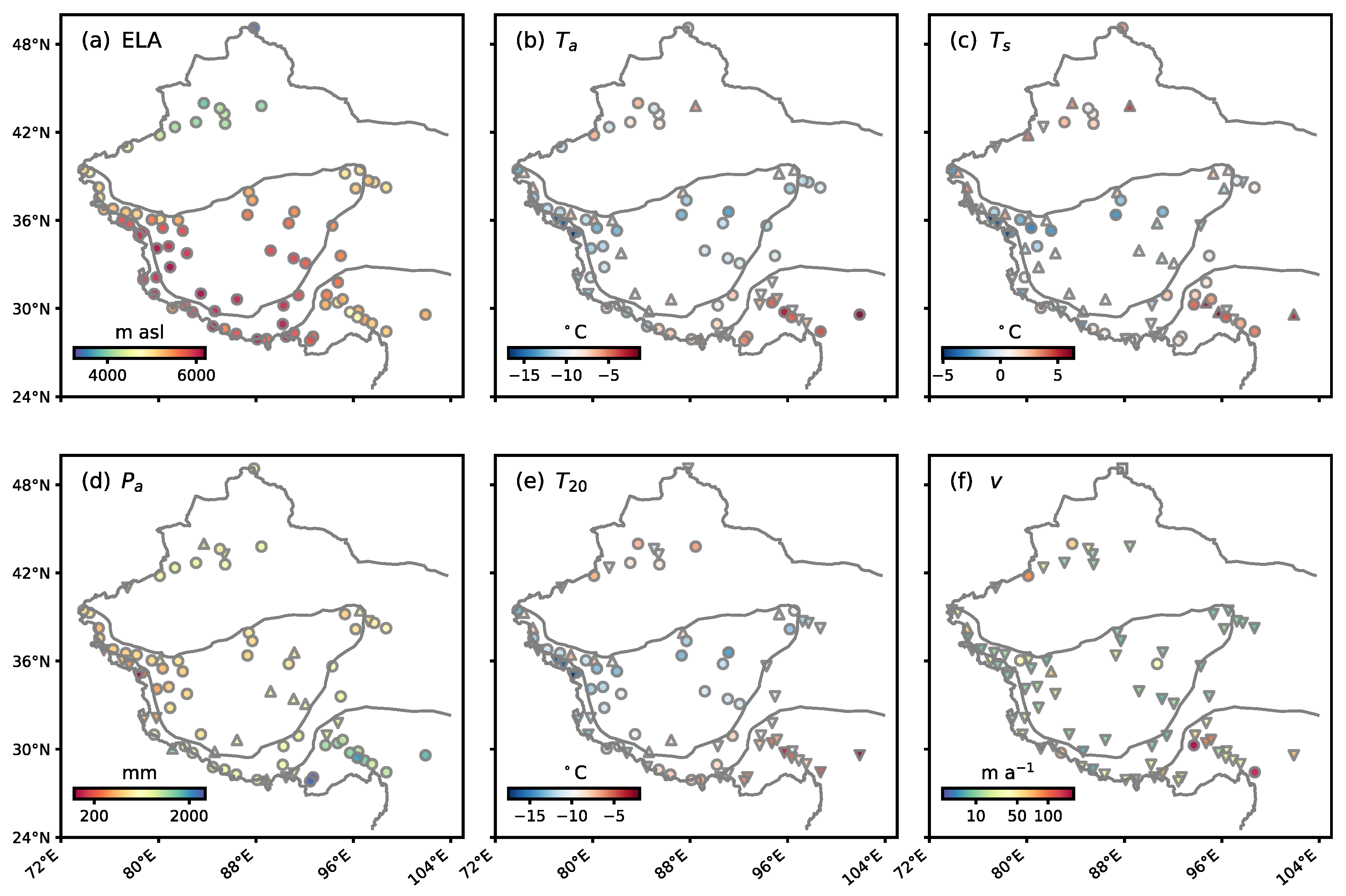

4.2.1. Distribution over the Period 1982-2000

- ELA

- 2.

- Annual mean temperature at ELA (Ta)

- 3.

- Summer mean temperature at ELA (Ts)

- 4.

- Annual precipitation at ELA (Pa)

- 5.

- Annual mean 20m ice temperature (T20)

- 6.

- Maximum glacier surface velocity (v)

4.2.2. Distribution over the Period 2001-2019

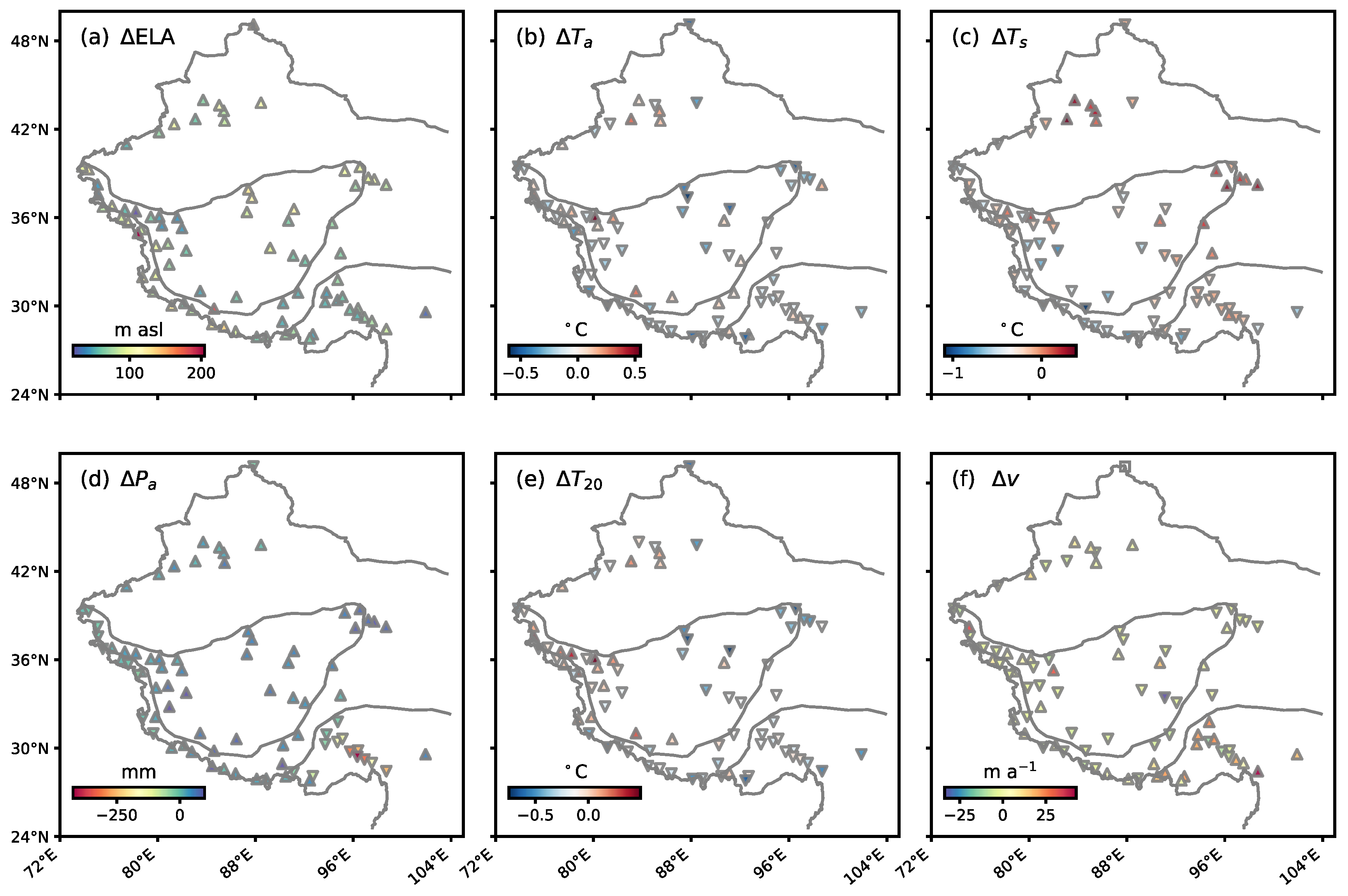

4.2.3. Changes Between the Two Periods

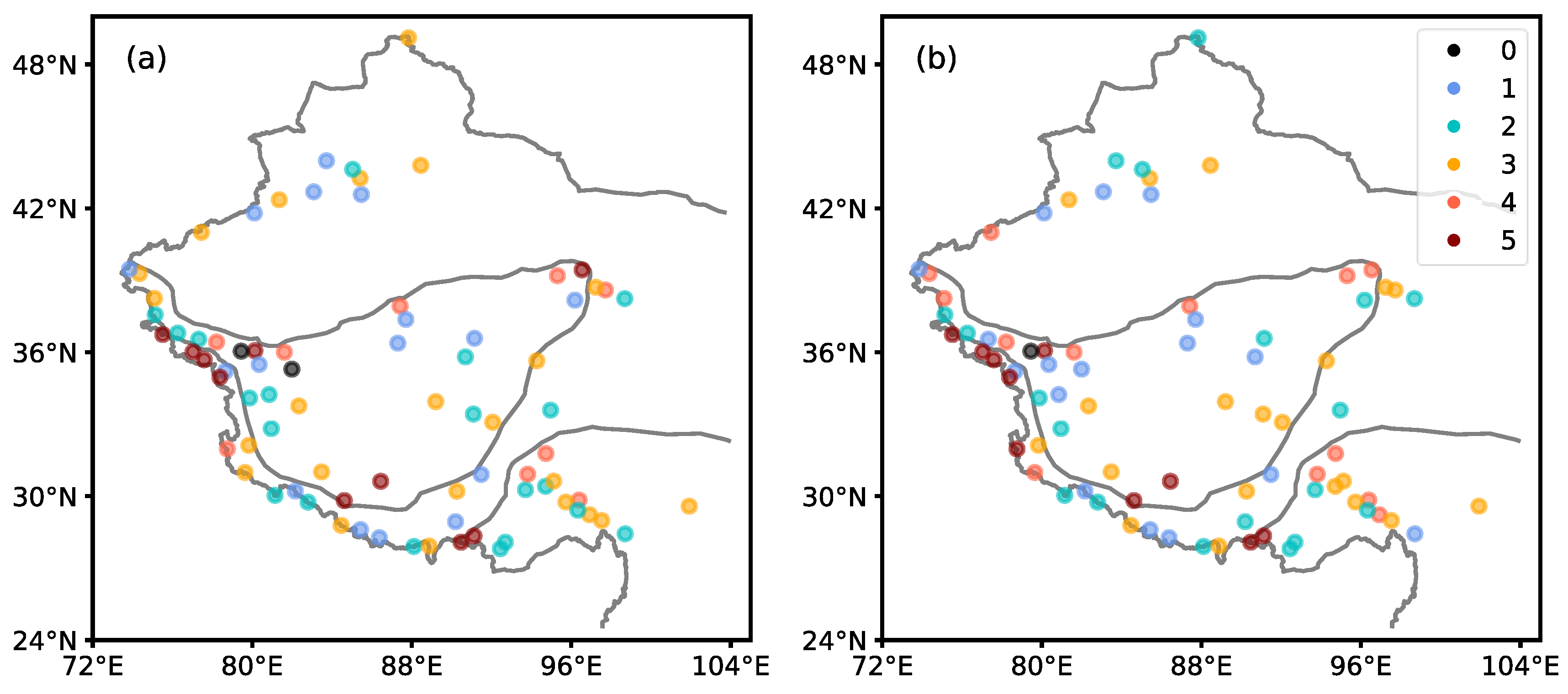

4.3. Threshold-Based Transitions in Glacier Types

5. Discussion

5.1. Drivers of Glacier Criteria Changes

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, Wanqin, Shiyin Liu, Junli Xu, Lizong Wu, Donghui Shangguan, Xiaojun Yao, Junfeng Wei, Weijia Bao, Pengchun Yu, Qiao Liu, and Zongli Jiang. "The Second Chinese Glacier Inventory: Data, Methods and Results." Journal of Glaciology 61, no. 226 (2015): 357-72.

- Kang, Ersi, Chaohai Liu, Zichu Xie, Xin Li, and Yongping Shen. "Assessment of Glacier Water Resources Based on the Glacier Inventory of China." Annals of Glaciology 50, no. 53 (2009): 104-10.

- Xiao, Cunde, Shijin Wang, and Dahe Qin. "A Preliminary Study of Cryosphere Service Function and Value Evaluation." Advances in Climate Change Research 6, no. 3 (2015): 181–87. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Tandong, Lonnie Thompson, Wei Yang, Wusheng Yu, Yang Gao, Xuejun Guo, Xiaoxin Yang, Keqin Duan, Huabiao Zhao, Baiqing Xu, Jiancheng Pu, Anxin Lu, Yang Xiang, Dambaru B. Kattel, and Daniel Joswiak. "Different Glacier Status with Atmospheric Circulations in Tibetan Plateau and Surroundings." Nature Climate Change 2, no. 9 (2012): 663-67. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ninglian, Tandong Yao, Baiqing Xu, An'an Chen, and Weicai Wang. "Spatiotemporal Pattern, Trend, and Influence of Glacier Change in Tibetan Plateau and Surroundings under Global Warming." Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences 34, no. 11 (2019): 1220–32.

- Shean, David E., Shashank Bhushan, Paul Montesano, David R. Rounce, Anthony Arendt, and Batuhan Osmanoglu. "A Systematic, Regional Assessment of High Mountain Asia Glacier Mass Balance." Frontiers in Earth Science 7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hugonnet, Romain, Robert McNabb, Etienne Berthier, Brian Menounos, Christopher Nuth, Luc Girod, Daniel Farinotti, Matthias Huss, Ines Dussaillant, Fanny Brun, and Andreas Kääb. "Accelerated Global Glacier Mass Loss in the Early Twenty-First Century." Nature 592, no. 7856 (2021): 726-31. [CrossRef]

- Dehecq, Amaury, Noel Gourmelen, Alex S. Gardner, Fanny Brun, Daniel Goldberg, Peter W. Nienow, Etienne Berthier, Christian Vincent, Patrick Wagnon, and Emmanuel Trouvé. "Twenty-First Century Glacier Slowdown Driven by Mass Loss in High Mountain Asia." Nature Geoscience 12, no. 1 (2019): 22–27. [CrossRef]

- Kääb, Andreas, Silvan Leinss, Adrien Gilbert, Yves Bühler, Simon Gascoin, Stephen G. Evans, Perry Bartelt, Etienne Berthier, Fanny Brun, Wei-An Chao, Daniel Farinotti, Florent Gimbert, Wanqin Guo, Christian Huggel, Jeffrey S. Kargel, Gregory J. Leonard, Lide Tian, Désirée Treichler, and Tandong Yao. "Massive Collapse of Two Glaciers in Western Tibet in 2016 after Surge-Like Instability." Nature Geoscience 11, no. 2 (2018): 114–20. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Tandong, Wusheng Yu, Guangjian Wu, Baiqing Xu, Wei Yang, Huabiao Zhao, Weicai Wang, Shenghai Li, Ninglian Wang, Zhongqin Li, Shiyin Liu, and Chao You. "Glacier Anomalies and Relevant Disaster Risks on the Tibetan Plateau and Surroundings." Science Bulletin 64, no. 27 (2019): 2770-82. [CrossRef]

- An, Baosheng, Weicai Wang, Wei Yang, Guangjian Wu, Yanhong Guo, Haifeng Zhu, Yang Gao, Ling Bai, Fan Zhang, Chen Zeng, Lei Wang, Jing Zhou, Xin Li, Jia Li, Zhijun Zhao, Yingying Chen, Jingshi Liu, Jiule Li, Zhongyan Wang, Wenfeng Chen, and Tandong Yao. "Process, Mechanisms, and Early Warning of Glacier Collapse-Induced River Blocking Disasters in the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, Southeastern Tibetan Plateau." Science of The Total Environment 816 (2022): 151652-52. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Guoxiong, Simon Keith Allen, Anming Bao, Juan Antonio Ballesteros-Cánovas, Matthias Huss, Guoqing Zhang, Junli Li, Ye Yuan, Liangliang Jiang, Tao Yu, Wenfeng Chen, and Markus Stoffel. "Increasing Risk of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods from Future Third Pole Deglaciation." Nature Climate Change 11, no. 5 (2021): 411–17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Taigang, Weicai Wang, Baosheng An, and Lele Wei. "Enhanced Glacial Lake Activity Threatens Numerous Communities and Infrastructure in the Third Pole." Nature Communications 14, no. 1 (2023): 8250. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Guoqing, Jonathan L. Carrivick, Adam Emmer, Dan H. Shugar, Georg Veh, Xue Wang, Celeste Labedz, Martin Mergili, Nico Mölg, Matthias Huss, Simon Allen, Shin Sugiyama, and Natalie Lützow. "Characteristics and Changes of Glacial Lakes and Outburst Floods." Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 5, no. 6 (2024): 447-62. [CrossRef]

- Su, Bo, Cunde Xiao, Deliang Chen, Yi Huang, Yanjun Che, Hongyu Zhao, Mingbo Zou, Rong Guo, Xuejia Wang, Xin Li, Wanqin Guo, Shiyin Liu, and Tandong Yao. "Glacier Change in China over Past Decades: Spatiotemporal Patterns and Influencing Factors." Earth-Science Reviews 226 (2022): 103926-26. [CrossRef]

- Hagg, Wilfried. Glaciology and Glacial Geomorphology: Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2022.

- Shi, Yafeng, and Zichu Xie. "Fundamental Characteristics of Modern Glaciers in China." Acta Geographica Sinica 30, no. 3 (1964): 183-213.

- Lai, Zuming, and Maohuan Huang. "The Fuzzy Cluster Analysis of Glaciers in China." Science Bulletin 33, no. 16 (1988): 1250-53.

- Shi, Yafeng, and Shiyin Liu. "Estimation on the Response of Glaciers in China to the Global Warming in the 21st Century." Science Bulletin 45 (2000): 434-38. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Dahe, Tandong Yao, Yongjian Ding, and Jiawen Ren. Introduction to Cryospheric Science, Springer Geography. Singapore: Springer, 2021.

- Wu, Guanghe, and Yongping Shen. "Glaciers Tourism Resources in China and Their Development." Journal of Glaciology and Geocryology 29, no. 4 (2007): 664-67.

- Li, Zhongqin, Feiteng Wang, Huilin Li, Chunhai Xu, Puyu Wang, Ping Zhou, and Xiaoying Yue. "Science and Long-Term Monitoring of Continental-Type Glaciers in Arid Region in China." Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences 33, no. 12 (2018): 1381-90.

- Ohno, Hiroyuki, Tetsuo Ohata, and Keiji Higuchi. "The Influence of Humidity on the Ablation of Continental-Type Glaciers." Annals of Glaciology 16 (1992): 107-14.

- Fujita, Koji, Yutaka Ageta, Pu Jianchen, and Yao Tandong. "Mass Balance of Xiao Dongkemadi Glacier on the Central Tibetan Plateau from 1989 to 1995." Annals of Glaciology 31 (2000): 159-63. [CrossRef]

- Bolch, T., T. Yao, S. Kang, M. F. Buchroithner, D. Scherer, F. Maussion, E. Huintjes, and C. Schneider. "A Glacier Inventory for the Western Nyainqentanglha Range and the Nam Co Basin, Tibet, and Glacier Changes 1976–2009." The Cryosphere 4, no. 3 (2010): 419–33.

- Shi, Yafeng. Concise Glacier Inventory of China. Shanghai: Shanghai Popular Science Press, 2005.

- Maussion, F., A. Butenko, N. Champollion, M. Dusch, J. Eis, K. Fourteau, P. Gregor, A. H. Jarosch, J. Landmann, F. Oesterle, B. Recinos, T. Rothenpieler, A. Vlug, C. T. Wild, and B. Marzeion. "The Open Global Glacier Model (Oggm) V1.1." Geoscientific Model Development 12, no. 3 (2019): 909–31-09–31. [CrossRef]

- Becker, J. J., D. T. Sandwell, W. H. F. Smith, J. Braud, B. Binder, J. Depner, D. Fabre, J. Factor, S. Ingalls, S. H. Kim, R. Ladner, K. Marks, S. Nelson, A. Pharaoh, R. Trimmer, J. Von Rosenberg, G. Wallace, and P. Weatherall. "Global Bathymetry and Elevation Data at 30 Arc Seconds Resolution: Srtm30_Plus." Marine Geodesy 32, no. 4 (2009): 355-71. [CrossRef]

- Maussion, F., A. Butenko, N. Champollion, M. Dusch, J. Eis, K. Fourteau, P. Gregor, A. H. Jarosch, J. Landmann, F. Oesterle, B. Recinos, T. Rothenpieler, A. Vlug, C. T. Wild, and B. Marzeion. "The Open Global Glacier Model (Oggm) V1.1." Geoscientific Model Development 12, no. 3 (2019): 909–31. [CrossRef]

- Lange, Stefan, Christoph Menz, Stephanie Gleixner, Marco Cucchi, Graham P. Weedon, Alessandro Amici, Nicolas Bellouin, Hannes Müller Schmied, Hans Hersbach, Carlo Buontempo, and Chiara Cagnazzo. "Wfde5 over Land Merged with Era5 over the Ocean (W5e5 V2.0)." ISIMIP Repository, 2021.

- Muñoz-Sabater, J., E. Dutra, A. Agustí-Panareda, C. Albergel, G. Arduini, G. Balsamo, S. Boussetta, M. Choulga, S. Harrigan, H. Hersbach, B. Martens, D. G. Miralles, M. Piles, N. J. Rodríguez-Fernández, E. Zsoter, C. Buontempo, and J. N. Thépaut. "Era5-Land: A State-of-the-Art Global Reanalysis Dataset for Land Applications." Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, no. 9 (2021): 4349-83.

- Chen, Yingying, Shankar Sharma, Xu Zhou, Kun Yang, Xin Li, Xiaolei Niu, Xin Hu, and Nitesh Khadka. "Spatial Performance of Multiple Reanalysis Precipitation Datasets on the Southern Slope of Central Himalaya." Atmospheric Research (2020): 105365-65. [CrossRef]

- Li, Yanzhao, Xiang Qin, Yushuo Liu, Zizhen Jin, Jun Liu, Lihui Wang, and Jizu Chen. "Evaluation of Long-Term and High-Resolution Gridded Precipitation and Temperature Products in the Qilian Mountains, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau." Frontiers in Environmental Science 10 (2022).

- Zhao, Peng, Zhibin He, Dengke Ma, and Wen Wang. "Evaluation of Era5-Land Reanalysis Datasets for Extreme Temperatures in the Qilian Mountains of China." Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cucchi, M., G. P. Weedon, A. Amici, N. Bellouin, S. Lange, H. Müller Schmied, H. Hersbach, and C. Buontempo. "Wfde5: Bias-Adjusted Era5 Reanalysis Data for Impact Studies." Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, no. 3 (2020): 2097-120. [CrossRef]

- Huss, Matthias, and Regine Hock. "A New Model for Global Glacier Change and Sea-Level Rise." Frontiers in Earth Science 3 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Lehner, Bernhard, and Günther Grill. "Global River Hydrography and Network Routing: Baseline Data and New Approaches to Study the World's Large River Systems." Hydrological Processes 27, no. 15 (2013): 2171-86. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Yaozhi, Kun Yang, Hua Yang, Hui Lu, Yingying Chen, Xu Zhou, Jing Sun, Yuan Yang, and Yan Wang. "Characterizing Basin-Scale Precipitation Gradients in the Third Pole Region Using a High-Resolution Atmospheric Simulation-Based Dataset." Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 26, no. 17 (2022): 4587-601. [CrossRef]

- Jing, Zhefan, Zaiming Zhou, and Li Liu. "Progress of the Research on Glacier Velocities in China." Journal of Glaciology and Geocryology 32, no. 4 (2010): 749-54.

- Gardner, A. S., M. A. Fahnestock, and T. A. Scambos. "Its_Live Regional Glacier and Ice Sheet Surface Velocities: Version 1." National Snow and Ice Data Center, 2019.

- Friedl, P., T. Seehaus, and M. Braun. "Global Time Series and Temporal Mosaics of Glacier Surface Velocities Derived from Sentinel-1 Data." Earth System Science Data 13, no. 10 (2021): 4653–75. [CrossRef]

- Millan, Romain, Jérémie Mouginot, Antoine Rabatel, and Mathieu Morlighem. "Ice Velocity and Thickness of the World's Glaciers." Nature Geoscience 15, no. 2 (2022): 124–29-24–29. [CrossRef]

- Kienholz, C., J. L. Rich, A. A. Arendt, and R. Hock. "A New Method for Deriving Glacier Centerlines Applied to Glaciers in Alaska and Northwest Canada." The Cryosphere 8, no. 2 (2014): 503-19. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Keqin, Tandong Yao, Ninglian Wang, Peihong Shi, and Yali Meng. "Changes in Equilibrium-Line Altitude and Implications for Glacier Evolution in the Asian High Mountains in the 21st Century." Science China Earth Sciences 65, no. 7 (2022): 1308-16. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Tandong, Tobias Bolch, Deliang Chen, Jing Gao, Walter Immerzeel, Shilong Piao, Fengge Su, Lonnie Thompson, Yoshihide Wada, Lei Wang, Tao Wang, Guangjian Wu, Baiqing Xu, Wei Yang, Guoqing Zhang, and Ping Zhao. "The Imbalance of the Asian Water Tower." Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 3, no. 10 (2022): 618-32. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Rongjun, Shiyin Liu, Donghui Shangguan, Valentina Radić, and Yong Zhang. "Spatial Heterogeneity in Glacier Mass-Balance Sensitivity across High Mountain Asia." Water 11, no. 4 (2019): 776. [CrossRef]

- Jouberton, Achille, Thomas E Shaw, Evan Miles, Michael McCarthy, Stefan Fugger, Shaoting Ren, Amaury Dehecq, Wei Yang, and Francesca Pellicciotti. "Warming-Induced Monsoon Precipitation Phase Change Intensifies Glacier Mass Loss in the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, no. 37 (2022): e2109796119. [CrossRef]

- Arndt, Anselm, and Christoph Schneider. "Spatial Pattern of Glacier Mass Balance Sensitivity to Atmospheric Forcing in High Mountain Asia." Journal of Glaciology 69, no. 278 (2023): 1616-33. [CrossRef]

- Rounce, David R, Regine Hock, and David E Shean. "Glacier Mass Change in High Mountain Asia through 2100 Using the Open-Source Python Glacier Evolution Model (Pygem)." Frontiers in Earth Science 7 (2020): 331. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Cen, Da-He Qin, and Pan-Mao Zhai. "Amplification of Warming on the Tibetan Plateau." Advances in Climate Change Research 14, no. 4 (2023): 493-501. [CrossRef]

- Sagredo, Esteban A, Summer Rupper, and Thomas V Lowell. "Sensitivities of the Equilibrium Line Altitude to Temperature and Precipitation Changes Along the Andes." Quaternary Research 81, no. 2 (2014): 355-66. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hongbo, WW Immerzeel, Fan Zhang, Remco J de Kok, Deliang Chen, and Wei Yan. "Snow Cover Persistence Reverses the Altitudinal Patterns of Warming above and Below 5000 M on the Tibetan Plateau." Science of The Total Environment 803 (2022): 149889. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L, J Chen, K Yang, Y Yang, W Huang, X Zhang, and F Chen. "The Northern Boundary of the Asian Summer Monsoon and Division of Westerlies and Monsoon Regimes over the Tibetan Plateau in Present-Day 66.4 (2023): 882-893." Science China Earth Sciences 66, no. 4 (2023): 882-93. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Yifeng, Qinglong You, Yuqing Zhang, Zheng Jin, Shichang Kang, and Panmao Zhai. "Integrated Warm-Wet Trends over the Tibetan Plateau in Recent Decades." Journal of Hydrology 639 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Eric, and Summer Rupper. "An Examination of Physical Processes That Trigger the Albedo-Feedback on Glacier Surfaces and Implications for Regional Glacier Mass Balance across High Mountain Asia." Frontiers in Earth Science 8 (2020): 129. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Maohuan;, and Yafeng Shi. "Progress in the Study on Basic Features of Glaciers in China in the Last Thirty Years." Journal of Glaciology and Geocryology 10, no. 3 (1988): 228-37.

- Paul, Frank, Tobias Bolch, Andreas Kääb, Thomas Nagler, Christopher Nuth, Killian Scharrer, Andrew Shepherd, Tazio Strozzi, Francesca Ticconi, Rakesh Bhambri, Etienne Berthier, Suzanne Bevan, Noel Gourmelen, Torborg Heid, Seongsu Jeong, Matthias Kunz, Tom Rune Lauknes, Adrian Luckman, John Peter Merryman Boncori, Geir Moholdt, Alan Muir, Julia Neelmeijer, Melanie Rankl, Jeffrey VanLooy, and Thomas Van Niel. "The Glaciers Climate Change Initiative: Methods for Creating Glacier Area, Elevation Change and Velocity Products." Remote Sensing of Environment 162 (2015): 408-26.

- Cuffey, Kurt M, and William Stanley Bryce Paterson. The Physics of Glaciers: Academic Press, 2010.

- Nanni, Ugo, Dirk Scherler, Francois Ayoub, Romain Millan, Frederic Herman, and Jean-Philippe Avouac. "Climatic Control on Seasonal Variations in Mountain Glacier Surface Velocity." The Cryosphere 17, no. 4 (2023): 1567-83.

- Wallis, Benjamin J., Anna E. Hogg, J. Melchior van Wessem, Benjamin J. Davison, and Michiel R. van den Broeke. "Widespread Seasonal Speed-up of West Antarctic Peninsula Glaciers from 2014 to 2021." Nature Geoscience 16 (2023): 231-37. [CrossRef]

| Type | Ta (°C) | Ts (°C) | Pa (mm) | T20 (°C) | v (m a-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXT | <-10 | <-1 | 200 - 500 | <-10 | 30 - 50 |

| SUB | -12 ~ -6 | 0 ~ 3 | 500 - 1000 | -10 ~ -1 | 50 - 100 |

| MAR | >-6 | 1 ~ 5 | 1000 - 3000 | -1 ~ 0 | >100 |

| Glacier | Altitude | Time period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LHG12 | 0.76 | 4.5% /100 m | 4500 m | 2010-2015 |

| DKMD | 0.82 | 1.4% /100 m | 4600 m | 2008-2010 |

| QY | 0.61 | 2.4% /100 m | 4870 m | 2008-2012 |

| URS1 | 0.60 | 4.1% /100 m | 3700 m | 2002-2004 |

| PL4 | 1.15 | -1.9% /100 m | 4600 m | 2008-2018 |

| HLG | 0.79 | -3.4% /100 m | 3500 m | 1980 and 2000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).