1. Introduction

Ag

2S QDs have been attracting great attentions because of their excellent performances and broad applications in various fields like solar cells [

1,

2], photocatalysis [

3], biology [

4,

5], optoelectronics[

6], etc. Their photophysical properties, including band gap, CB/VB positions and oscillator strength show strong size dependence, termed as quantum size effect. They show maximum quantum efficiency when their size is smaller than or comparable to the double exciton Bohr radius[

7,

8,

9]. Generally, the QDs are engineered into 2D /3D structures in their applications[

10,

11], when uniform small-size particles are desired. However, how to synthesize such products remains a long-standing challenge due to complicated and polluting process, lower yield, as well as high cost.

The prevalent routes for synthesizing Ag

2S QDs are high-temperature including heating up process[

12,

13], hot injection approach[

14,

15] and thermal decomposition of single source precursor[

16,

17], which are all carried out in organic solvent. In the synthesis, the size of products could be finely controlled, but the direct products are oil-soluble wrapping by ligands, hindering interfacial charge transfer and quantum yields [

18,

19]. The post treatment include purifying and ligand-exchanging procedures[

20], leaving behind a lot of pollutants and resulting in lower yield and high cost. So, it is urgent to develop a low-temperature and direct approach for synthesizing desired products. Pileni reported a reverse microemulsion protocol, a room-temperature approach, for synthesizing small-size nanoparticles in late 1980s[

21,

22], which utilized micelles as nanoreactors controlling particle size. In fact, the system is a “twin micelles” approach, carrying out by mixing two micelles of different water-soluble precursors. The reaction take place through coalescence of different micelles, resulting polydisperse products. The monodisperse products were obtained through a multiple size-selective extraction process [

23], resulting lower yield.

In hot injection approach, alkylamines are used as ligands, preventing particles from aggregating by forming protective shells, but it doesn’t work for “twin micelles” [

24]. During past two decades, phase-transfer was extensively investigated to extract metal ions from water by toluene [

25,

26]. If the oil-soluble metal ions can reversely diffuse to new water phase they can be directly used as oil-soluble precursors constructing a “uni-micelle” system. Aiming the purposes, we developed a reversible phase-transfer process, and water- soluble Ag(I) was enabled to be dual-soluble in oil/water by forming Ag(I)-OA complex [

27]. Here we first conducted an “uni-micelle” approach for controlled synthesis of Ag

2S QDs, in which aqueous solution of Na

2S is employed as S precursor, sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulphosuccinate (AOT) as surfactant and isooctane as oil phase, forming an “uni-micelle” of water/AOT/isooctane. It is worth noting that there is only one kind micelle containing Na

2S solution in the system while the oil solution of Ag(I)-OA is gradually added into the reaction system. Monodisperse Ag

2S QDs were directly fabricated with tunable solubility in water/oil by employing different ligands.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of the Oil Solution of Ag(I) Precursor via Reversible Phase-Transfer

In order to develop a uni-micelle synthesis method for silver sulfide quantum dots, the preparation of oil-soluble silver precursors is an important step. In our previous research work [

27], we developed a reversible phase transfer method to transfer silver ions of silver nitrate into isooctane and enabled it solubility in water/oil, and used it for the controlled synthesis of silver nanoparticles with good results. However, the synthesis effect is poor when this silver-amine complex was used to synthesize silver sulfide quantum dots, which should be attributed to the different reaction mechanisms of the two materials and the different crystallization properties of the two materials. The former is a redox reaction in which a high concentration of ascorbic acid (0.6 M) is used to reduce silver ions to obtain silver nanocrystals, while the synthesis of silver sulfide is a co-precipitation reaction between sulfur ions and silver ions. At the same time, the concentration of sodium sulfide must be controlled below 0.05 M, although the specific reaction mechanism needs to be further studied to be revealed, we speculate that the crystallization of silver sulfide molecules is poorer than that of silver nanocrystals, and the presence of high concentrations of sulfur ions will exacerbate this trend. Referring to our previous reversible phase transfer method[

27], a dual-soluble silver precursor was prepared employing silver trifluoroacetate as the silver source. In a typical procedure, 10mL of 10.0 mM water solution of silver trifluoroacetate and 10mL of 50.0 mM ethanol solution of OA were mixed and stirring to get a mixture solution (

Figure 1a), where Ag(I)-OA complex was formed Then mixing the Ag(I)-OA solution with 10mL of isooctane and stirring for 10 minutes,

Figure 1b). The results showed that 85.6% of Ag(I) was transferred into isooctane (

Table S1). Then, a reverse phase-transfer was carried out by mixing isooctane solutions of the complex with water. The results (

Table S1) shown that part of Ag(I) diffused to aqueous phase again from isooctane and the diffusion equilibrium constant K

d2 is approximately equal to K

d1. Similarly, the precursor solution of Cu(II) and Co(II) were prepared.

Figure 1a–c shows the photographs of metal ions at different reversible phase-transfer procedure..

2.2. Proposed Mechanism on the Synthesis of Ag2S QDs Through “Uni-Micelle” System

To synthesize monodisperse Ag

2S QDs, a “uni-micelle” system of water/AOT/isooctane was constructed using isooctane solution of Ag(I)-OA and Na

2S solution as precursors.

Figure 1d is the schematic diagram of synthesis mechanism. In the system, uniform micelles containing S

2- serve as the nanoreactors, which carried palisade layers of AOT molecules between water droplets and bulk isooctane[

21]. During the synthesis, the hydrophilic end Ag(I) of the Ag(I)-OA complex passes through the palisade layers into the micelles from isooctane phase and take co-precipitation reaction with the sulfur ions forming silver sulfide crystal nucleus, while the hydrophobic end OA molecules are grouped outside palisade layers. As the gradual addition of Ag(I)-OA complexes, the silver sulfide nuclei gradually grow up, and more OA molecules attach to the micelle out-shell, which enhances the hardness of the micelles and prevents the agglomeration between micelles. Furthermore, the bigger particles such as nuclei were isolated by the rigid palisades and can’t be exchanged out while small Ag(I) ions penetrate the palisades allowing the particle growth, which comply with Ostwalt ripening rule [

23], thereby ensuring the dimensional uniformity of the synthesized silver sulfide quantum dots. In addition, the drop rate and dosage of oil-soluble silver can be freely adjusted as needed, so the reaction rate of the method and the size of the silver sulfide quantum dots are easily controlled.

2.3. Size Controlled Synthesis of Ag2S QDs Through “Uni-Micelle” System

It is well known that the molar ratio (

ѡ) of water to AOT is a key factor in reverse micelle, which is proportional to the micelle determining the particle size [

21]. In a typical synthesis, 90µL of 0.05 M aqueous solution of Na

2S was first added into 5mL of 0.1 M isooctane solution of AOT forming transparent micelle, in which the “

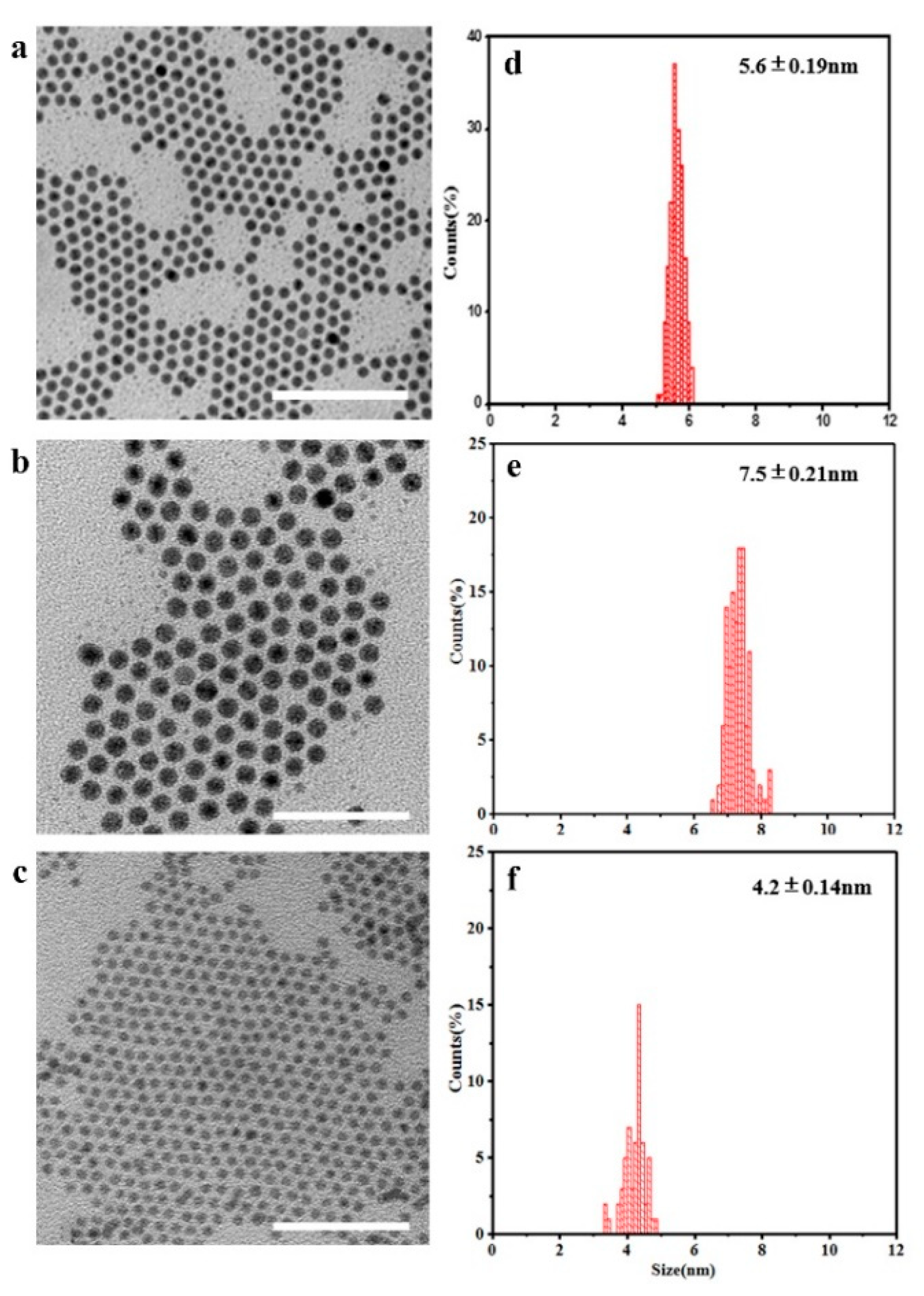

ѡ” is equal to 10, corresponding to a micelle size of 3.0 nm. Then 90 µL of 8.56 mM isooctane e solution of Ag(I)-OA complex was added dropwise to the reaction system under ultrasonication in 15 minutes, when the mixture turned yellowish, implying the nanocrystals were formed. TEM images of the as-resulted Ag

2S QDs show that the average size is 5.60±0.19 nm (

Figure 2a,d), and the size distribution is much narrower with a standard deviation, σ, ~3.3%, than those of the samples synthesized via “twin micelle”, where the σ > 17.0%[

28]. The results also implied that particle aggregation is prevented in the “uni-micelle” system. When the amount of Ag(I)-OA was increased to 180 µL keeping the “ѡ” at 10.0, the size of the Ag

2S QDs increased to 7.50±0.21 nm (

Figure 2b,e) from 5.60±0.19 nm. The results demonstrate that the nanocrystal size can be easily tuned through controlled the amount of Ag(I)-OA complex. Meanwhile the size distribution of the-obtained Ag

2S QDs was also very narrow, σ=~2.8%, further confirming particle aggregation was blocked. The yield of these products is about 80% -85% (Equation 3 in Supporting Information).

As the Ag2S QDs grow larger, the free water molecules in the micelles become AOT-bound molecules, and the water droplets become stiffen, reducing their ability to accommodate new members, the out layer of the micelles become stiffer, and the large Ag2S particles stop growing and remain thermodynamically stable. Our experimental results show that after the silver sulfide quantum dots have grown up to 7.5 nm (ѡ = 10.0), the larger Ag2S QDs particles keep the same size and new smaller particles form with adding more Ag(I)-OA to the reaction system (Figure S1), which is attributed to the excess S2- reacting with Ag(I)-OA in hollow micelles to form new crystal nuclei.

In the synthesis, when the “ѡ” was decreased from 10.0 to 7.5 keeping the amount of Ag(I)-OA unchanged, the size of Ag

2S QDs decrease to 4.20±0.14 nm (

Figure 2c,f). The results domonstrate that the particle size can be controlled by adjusted the “ѡ”, which is consistent with the previous literature[

21].

2.4. Structures and Performances of the as- Synthesized Ag2S QDs

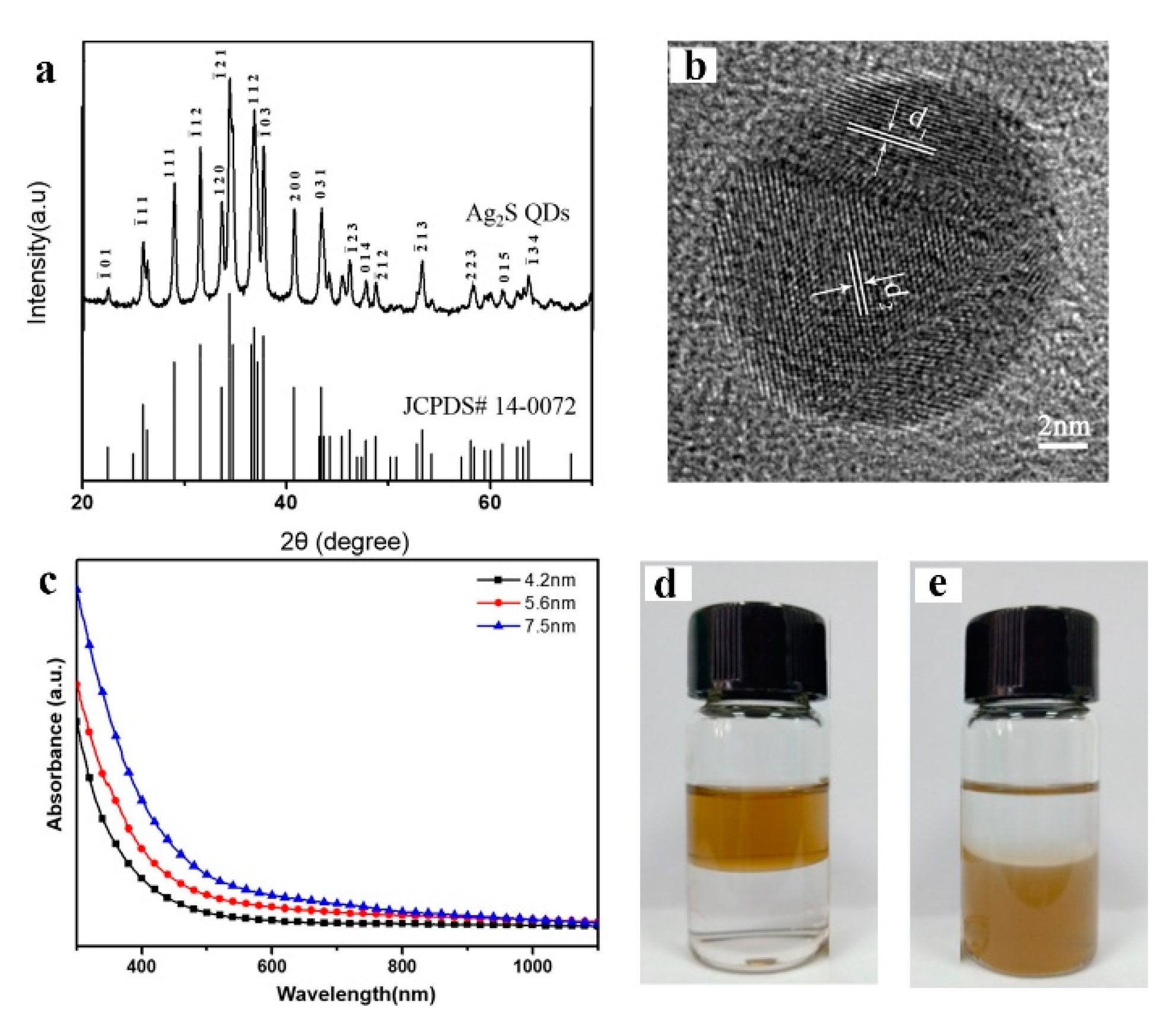

The XRD pattern of the as-resulted sample shows that all of the peaks well-match those of monoclinic α-Ag

2S, and the calculated lattice constants are

a) 4.226 Å,

b) 6.928 Å, and

c) 7.858 Å (JCPDS 14-0072)

(Figure 3a). HRTEM characterization results indicate the resultant nanocrystals have an inter planar distance of the lattice fringes of ~0.26 nm, which corresponds to the(-121)facets of monoclinic crystalline Ag

2S (

Figure 3b).

Figure 3c shows the UV–vis absorption spectra of the as-prepared Ag

2S QDs (4.2 nm, 5.2 nm and 7.5 nm, respectively), which reveal the broad absorption spectrum from NIR to UV-vis region (300-1100 nm). The direct band gaps (

Eg(eV)) can be deduced from the plots of [F(R)hν]

2 versus energy (hν) by performing Kubelka–Munk transformations [

29]. The

Eg are estimated to be 1.68 eV, 1.63 eV, 1.57 eV for the Ag

2S QDs of 4.2 nm, 5.6 nm and 7.5 nm

(Figures S2-4), respectively, which are much higher than that of bulk Ag

2S (1.1 eV), implying they behave within the quantum-confinement regime and the

Eg is enlarged with the decrease of particle size. The photoluminescence spectrum of the synthesized Ag

2S QDs (7.5 nm,

Figure S5) shows a symmetric photoemission peak centered at 1140 nm with an impressive full width of 35 nm, implying they have large potential in NIR relevant applications.

To investigate solubility of Ag

2S QDs, ethanol solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MPH) was first employed as ligand modifying the as-prepared products. The collected sample was dispersed in water forming yellowish transparent solution, which is very stable, with no sign of agglomeration even after seven weeks of storage (

Figure 3e). It was attributed that stable S-Ag bounds are formed between nanoparticles surface and thiol groups of MPH while their hydrophilic hydroxyl groups stretch out into water favoring their dispersing in water. Then, dodecylthiol was also used as ligand to modify Ag

2S QDs obtaining their transparent isooctane solution (

Figure 3d). The results imply that the particles surface in the water droplets are bared and easily formed stable S-Ag bounds with the thiol groups of different ligands. It can be speculated that the particles can be modified using many other ligands to directly get desired products, facilitating their applications.

The results also demonstrate the as-prepared Ag

2S QDs were well organized into hexagonal close-packed 2D matrix (

Figure 2a-c) and 3D supra-crystalline lattice (

Figure S6), which is attributed to the monodisperse particles and the interdigitation of ligand chains on neighboring particles. The cases are in accordance with that reported in literatures[

30], which offer large possibilities for potentially useful collective physical phenomena and facilitate their applications.

Similarly, CuS QDs and CdS QDs were synthesized via “uni-micelle”, which are of small size and narrow size distribution (Figure S7-11). It can be assumed that the approach can be extended to synthesize a large number of metal sulfide QDs because of their similar ionic nature.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we firstly report a metal alkylamine complex manipulating uni-micelle protocol for controlled synthesis of Ag2S QDs “uni-micelle”, which is a room-temperature and one-pot process employing inexpensive precursors. During the synthesis, OA molecules play the key roles which serves as efficient transfer agent while reinforcing micelles and preventing particle aggregation. Monodisperse Ag2S QDs could be synthesized with the rational designed size, narrow distribution and surface modification by adjusting the value of ‘w”, the dosage of Ag(I)-OA complex and ligand species. The as-synthesized Ag2S QDs showed excellent NIR fluorescence and could be well assembled into 2D or 3D superlattices. The results demonstrate that the protocol can provide a general platform for synthesizing a large number of metal sulfide QDs based on their similar ionic nature.

Supporting Information

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Detailed synthesis methods, characterization data from TEM, XRD, UV-vis and FL measurements. Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020ME054); the National Program for Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (“111” plan).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Ahmad, R., et al., Size-Tunable Synthesis of Colloidal Silver Sulfide Nanocrystals for Solution-Processed Photovoltaic Applications. CHEMISTRYSELECT, 2018. 3(20): p. 5620-5629. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.S.G., et al., Silver sulphide nano-particles enhanced photo-current in polymer solar cells. Applied Physics A, 2020. 126(3): p. 207. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., et al., Silver sulphide (Ag2S) quantum dots synthesized from aqueous route with enhanced antimicrobial and dye degradation capabilities. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures, 2023. 151: p. 115730. [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.J., et al., Self-illuminating NIR-II bioluminescence imaging probe based on silver sulfide quantum dots. ACS Nano, 2022. 16(10): p. 16824-16832. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q., et al., One-Step Synthesis of Water-Soluble Silver Sulfide Quantum Dots and Their Application to Bioimaging. ACS Omega, 2021. 6(9): p. 6361-6367. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, V., et al., Pyro-phototronic effect in colloidal quantum dots on silicon heterojunction for high-detectivity infrared photodetectors. Nano Energy, 2025. 133: p. 110465. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., Controlled Synthesis of Ag2S Quantum Dots and Experimental Determination of the Exciton Bohr Radius. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2014. 118(9): p. 4918-4923. [CrossRef]

- Pietryga, J., et al., Spectroscopic and Device Aspects of Nanocrystal Quantum Dots. Chemical reviews, 2016. 116: p. 10513-10622. [CrossRef]

- Stroyuk, A.L., et al., Quantum Size Effects in Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Theoretical and Experimental Chemistry, 2005. 41(4): p. 207-228. [CrossRef]

- Pinna, J., et al., Approaching Bulk Mobility in PbSe Colloidal Quantum Dots 3D Superlattices. ADVANCED MATERIALS, 2023. 35(8). [CrossRef]

- Ushakova, E.V., et al., 3D superstructures with an orthorhombic lattice assembled by colloidal PbS quantum dots. Nanoscale, 2018. 10(17): p. 8313-8319. [CrossRef]

- Raphael, E., D.H. Jara, and M.A. Schiavon, Optimizing photovoltaic performance in CuInS2 and CdS quantum dot-sensitized solar cells by using an agar-based gel polymer electrolyte. RSC Advances, 2017. 7(11): p. 6492-6500. [CrossRef]

- Akdas, T., et al., Continuous synthesis of CuInS2 quantum dots. RSC Advances, 2017. 7(17): p. 10057-10063. [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo-Siguan, M., et al., Bis(stearoyl) Sulfide: A Stable, Odor-Free Sulfur Precursor for High-Efficiency Metal Sulfide Quantum Dot Photovoltaics. ADVANCED ENERGY MATERIALS, 2023. 13(20). [CrossRef]

- Ratnesh, R.K., Hot injection blended tunable CdS quantum dots for production of blue LED and a selective detection of Cu2+ ions in aqueous medium. Optics & Laser Technology, 2019. 116: p. 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Masikane, S.C., et al., Lead(II) halide cinnamaldehyde thiosemicarbazone complexes as single source precursors for oleylamine-capped lead sulfide nanoparticles. JOURNAL OF MATERIALS SCIENCE-MATERIALS IN ELECTRONICS, 2018. 29(2): p. 1479-1488. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, J.C. and G. Hogarth, Dithiocarbamate Complexes as Single Source Precursors to Nanoscale Binary, Ternary and Quaternary Metal Sulfides. CHEMICAL REVIEWS, 2021. 121(10): p. 6057-6123. [CrossRef]

- Wepfer, S., et al., Solution-Processed CuInS2-Based White QD-LEDs with Mixed Active Layer Architecture. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2017. 9(12): p. 11224-11230. [CrossRef]

- Tapley, A., et al., Assessing the Band Structure of CuInS2 Nanocrystals and Their Bonding with the Capping Ligand. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2015. 119(36): p. 20967-20974. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J., N. Schaeffer, and M.P. Pileni, Ligand Exchange Governs the Crystal Structures in Binary Nanocrystal Superlattices. J Am Chem Soc, 2015. 137(46): p. 14773-84. [CrossRef]

- Pileni, M., Reverse Micelles as Micro-reactors. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 1993. 97. [CrossRef]

- Ingert, D., et al., CdTe Quantum Dots Obtained by Using Colloidal Self-Assemblies as Templates. Advanced Materials - ADVAN MATER, 1999. 11: p. 220-223.

- Kershaw, S.V., A.S. Susha, and A.L. Rogach, Narrow bandgap colloidal metal chalcogenide quantum dots: synthetic methods, heterostructures, assemblies, electronic and infrared optical properties. Chem Soc Rev, 2013. 42(7): p. 3033-87. [CrossRef]

- Wikander, K., et al., Size Control and Growth Process of Alkylamine-Stabilized Platinum Nanocrystals: A Comparison between the Phase Transfer and Reverse Micelles Methods. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids, 2006. 22: p. 4863-8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., et al., A general phase-transfer protocol for metal ions and its application in nanocrystal synthesis. Nat Mater, 2009. 8(8): p. 683-9. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., et al., Fine silver sulfide–platinum nanocomposites supported on carbon substrates for the methanol oxidation reaction. RSC Advances, 2017. 7(6): p. 3455-3460. [CrossRef]

- Li H L, Xue J, Liu Z P, et al. Reversible phase-transfer mediated single reverse micelle towards synthesis of silver nanocrystals. Sci China Tech Sci, 2020, 63. [CrossRef]

- Motte, L. and M. Pileni, Influence of Length of Alkyl Chains Used To Passivate Silver Sulfide Nanoparticles on Two- and Three-Dimensional Self-Organization. Journal of Physical Chemistry B - J PHYS CHEM B, 1998. 102. [CrossRef]

- Hagfeldt, A. and M. Graetzel, Light-Induced Redox Reactions in Nano-Crystalline Systems. Chemical Reviews; (United States), 2009. 95:1. [CrossRef]

- Bagwe, R. and K. Khilar, Effects of Intermicellar Exchange Rate on the Formation of Silver Nanoparticles in Reverse Microemulsions of AOT. Langmuir, 2000. 16. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).