Introduction

Insects are among the most evolutionary successful organisms on Earth, largely due to their remarkable adaptability to diverse and rapidly changing environments. Drosophila melanogaster, the fruit fly, has long served as a cornerstone model in genetics and evolutionary biology, offering unique advantages such as a short generation time, ease of genetic manipulation, and a deeply characterized genome (Beckingham et al., 2005). These traits make D. melanogaster an ideal system for investigating the genetic basis of complex traits and evolutionary processes.

With the rise of high-throughput sequencing technologies, our ability to link genetic variation to phenotypic traits has advanced dramatically. Genomic selection (GS) was introduced by Meuwissen et al. (2001) as an extension of marker-assisted selection, designed to capture the full genetic variance of complex traits by using dense, genome-wide marker coverage. The core idea of GS is that, by including markers across the entire genome—assumed to be in linkage disequilibrium with underlying quantitative trait loci (QTL)—it becomes possible to estimate the genetic contribution of all loci simultaneously, even if the specific QTL are unknown. Unlike traditional methods such as best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP; Henderson, 1975), which estimate genetic merit based on pedigree-derived relationships, genomic selection (GS) utilizes genome-wide SNP data to calculate realized genetic relationships among individuals. This marker-based approach significantly improves the accuracy of estimated breeding values (EBVs) by capturing actual genetic similarities rather than relying on expected relationships (Boichard et al., 2016). Additionally, GS enables the identification of high-performing individuals early in life, thereby shortening the generation interval and accelerating the rate of genetic improvement (Boichard et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2009).

A variety of statistical models have been developed for genomic prediction, these models can be classified into two groups: linear and nonlinear methods. Among linear models are genomic best linear unbiased prediction (GBLUP; VanRaden, 2008) and ridge regression best linear unbiased prediction (RRBLUP; Piepho, 2009). The nonlinear methods include Bayesian methods like Bayes A and B (Meuwissen & Goddard, 2010; Gianola, 2013). The performance of statistical models in GS depends heavily on the genetic architecture of traits, including the number and effect size of QTLs and marker density (Daetwyler et al., 2010). Research indicates that Bayesian methods, such as Bayes B, may outperform linear mixed models like GBLUP when traits are influenced by fewer QTLs with larger effects (Coster et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2011; Li & Sillanpää, 2012b). However, empirical studies with real-world data suggest that GBLUP can perform comparably to or, in some cases, outperform Bayesian variable selection models for many traits (Zhong et al 2009; Ober et al., 2012; Rius-Vilarrasa et al., 2012; de los Campos et al., 2013). In Drosophila melanogaster, GBLUP has even been found to yield higher prediction accuracy than BayesB for QTL-associated traits derived from whole-genome sequence data (Ober et al., 2012). One of the practical strengths of GBLUP lies in its ease of implementation through existing residual maximum likelihood (REML) and BLUP frameworks and lower computational demands, making it practical for large-scale genomic predictions (El-Kassaby et al., 2012). Although newer algorithms such as expectation–maximization and variational Bayes have reduced the computational burden of Bayesian approaches (Li & Sillanpää, 2012a; Li & Sillanpää, 2012b), GBLUP remains a widely adopted and effective method in genomic evaluations due to its simplicity and efficiency.

Although GS models are well-established in the fields of breeding and quantitative genetics, their application to Drosophila melanogaster remains relatively limited. To date, only a few studies have systematically compared the predictive performance of different models in this species, and only one has explicitly examined sex-specific differences in prediction accuracy (Ober et al., 2012; Ober et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2016). This represents a critical gap, as both trait-specific genetic architectures and sex-specific genetic effects likely influence the performance of genomic prediction models. However, their combined impact remains poorly understood, particularly in the context of high-resolution genomic data. In this study, we evaluate the performance of GBLUP and Bayes B using food intake phenotypic data from male and female inbred lines of D. melanogaster obtained from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP), along with approximately 4.5 million genome-wide SNPs (Mackay et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2014; Garlapow et al., 2015). By conducting sex-stratified predictions and employing 5-fold cross-validation, we assess how prediction accuracy varies across traits and between sexes, measuring predictive ability as the correlation between observed phenotypes and predicted genetic values. Our results aim to improve genomic prediction strategies and provide insights into the role of sex and trait complexity in shaping model performance, with broader implications for evolutionary genomics and the study of complex trait variation in genetically diverse organisms.

Methodology

Phenotypic and Genotypic Data

This study utilizes phenotypic and genotypic data from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP), a comprehensive resource developed for genetic analyses of complex traits (Mackay

et al. 2012; Huang

et al. 2014). The DGRP consists of 205 inbred

Drosophila melanogaster lines, each established through 20 generations of full-sib mating from the progeny of individual wild-caught females from a Raleigh, North Carolina population. Each line has been fully sequenced, yielding approximately 4.5 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome. All data are publicly available through the DGRP online portal (

http://dgrp2.gnets.ncsu.edu), facilitating robust genomic studies. Phenotypic measurements for food intake of males and females were available for 182 DGRP lines (Garlapow

et al., 2015). These data provide a high-resolution genomic framework to evaluate the predictive accuracy of statistical models for quantitative traits in male and female flies.

Data Preprocessing

Data preprocessing was performed to ensure the quality and consistency of the genomic data from the DGRP, provided in Variant Call Format (VCF). Quality control and filtering were conducted using PLINK version 1.9 (Shaun Purcell, Christopher Chang;

www.cog-genomics.org/plink/1.9; Chang

et al., 2015) to maintain data integrity for downstream analyses. Variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) below 1% were excluded to focus on common variants with potential biological relevance, and variants with more than 5% missing genotype data were removed to ensure data completeness. The filtered dataset was reformatted to VCF for compatibility with imputation software. Missing genotypes were imputed using Beagle version 5.5 Browning

et al., 2015) to enhance dataset completeness, thereby improving the reliability of genomic prediction analyses.

Prediction Accuracy and 5-Fold Cross-Validation

To evaluate the prediction accuracy of genomic models, we implemented a 5-fold cross-validation (CV) strategy. In this approach, the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel population was randomly partitioned into five subsets. For each fold, four subsets served as the training set to build the prediction model, while the remaining subset was used as the validation set to test the model’s performance. This process was repeated five times, ensuring each subset was used as the validation set once. Prediction accuracy was quantified as the Pearson correlation coefficient between the predicted genetic values and the observed phenotypic values for the validation set. The correlations from the five folds were averaged to obtain a single predictive ability estimate per CV replicate. To ensure robustness, we conducted 30 replicates of the 5-fold CV for each model, performed separately for males and females to account for potential sex-specific differences. Genomic predictions were generated using the GBLUP model, implemented via the rrBLUP package (Endelman, 2011), and the Bayes B model, implemented using the hibayes package in R (Yin et al., 2022). These analyses enabled a comprehensive assessment of the predictive performance of each model across phenotypic traits.

Statistical Comparison of Model Predictive Ability

For each genomic feature, Welch’s t-test (i.e., unequal variance t-test) was used to test the difference in mean predictive ability of the two models (Welch, 1947). This test allowed us to compare the mean predictive accuracies of the GBLUP and Bayes B models for each sex separately.

Results

The DGRP dataset, after processing and cleaning, comprised ~1.96 million common SNPs (minor allele frequency ≥0.01) across chromosomes 2L, 2R, 3L, 3R, 4, and X, derived from genomic sequences of 205 largely unrelated inbred lines (Mackay et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2014). Food intake, measured as total food consumption in microliters (μL), was the phenotypic trait analyzed. Males showed a mean intake of 16.48 ± 3.23, while females had a mean of 17.34 ± 3.76 μL. The intake ranged from 7.06–25.33 in males and 9.99–30.06 μL in females, indicating moderate phenotypic variability across sexes.

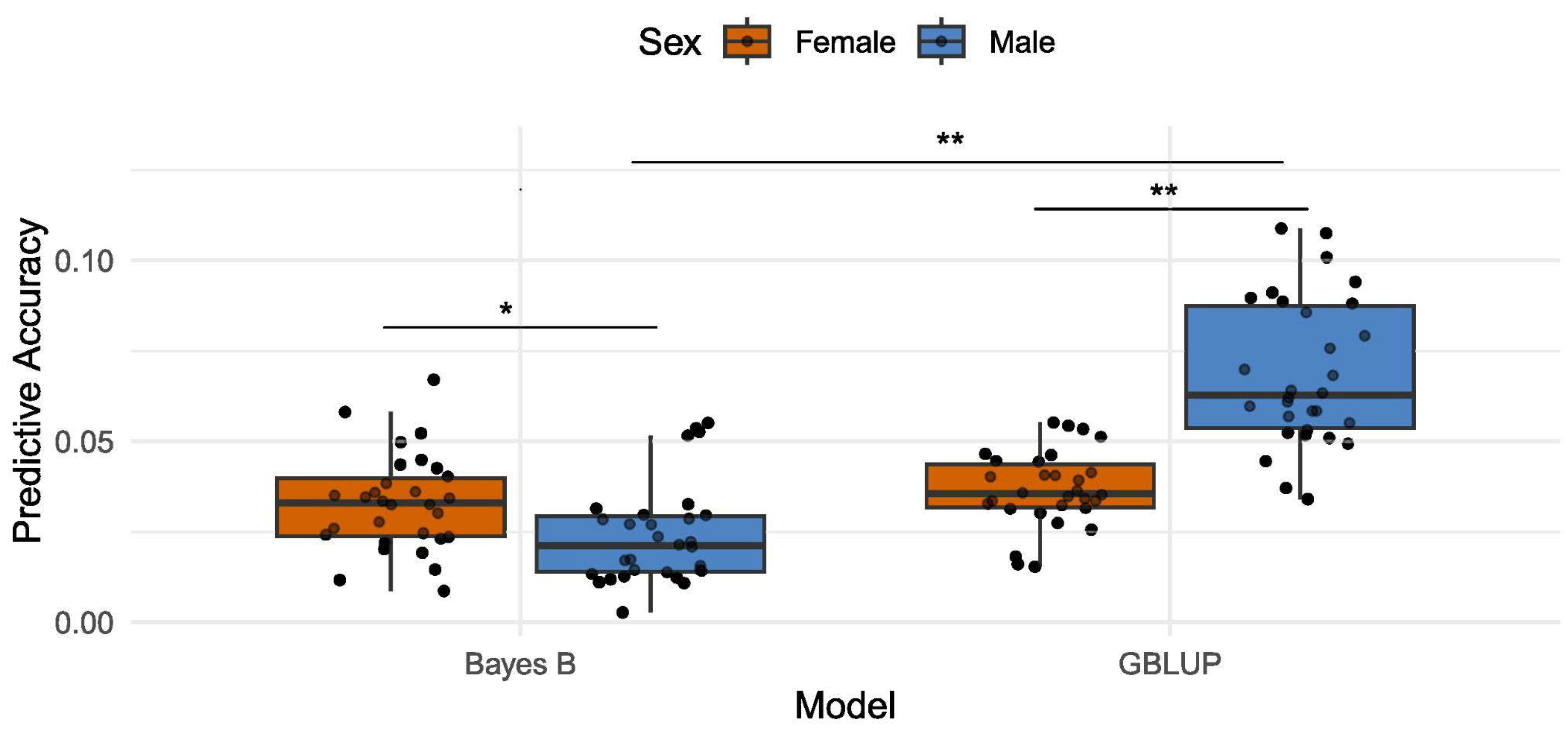

Using 5-fold cross-validation with 30 replicates, we assessed the predictive performance of GBLUP and Bayes B models for food intake. Predictive ability, estimated as the correlation between predicted genetic values and observed phenotypes, was generally low. For GBLUP, predictive ability was 0.0368 ± 0.0103 in females and 0.0687 ± 0.0203 in males. Similarly, Bayes B yielded 0.0329 ± 0.0379 in females and 0.0239 ± 0.0138 in males (

Figure 1).

The GBLUP model showed significantly higher predictive ability for food intake in male Drosophila melanogaster than in females (mean difference = 0.0319, 95% CI = [0.0235, 0.0403], Welch’s t-test: t = 7.65, df = 43.11, p < 0.001). In contrast, the predictive ability of Bayes B was significantly greater in females than in males (mean difference = 0.0090, 95% CI = [0.0020, 0.0160], Welch’s t-test: t = 2.56, df = 57.93, p = 0.013). There was no significant difference in predictive performance between GBLUP and Bayes B for food intake in females (mean difference = 0.0038, 95% CI = [-0.0027, 0.0104], paired t-test: t = 1.20, df = 29, p = 0.238). In contrast, GBLUP significantly outperformed Bayes B in males, with a mean difference of 0.0450 (95% CI = [0.0350, 0.0540], paired t-test: t = 9.91, df = 29, p < 0.001). These results suggest sex-specific differences in model performance, potentially driven by the genetic architecture of food intake.

Discussion

Understanding the genetic basis of phenotypic traits in Drosophila melanogaster is crucial for unraveling mechanisms of adaptation in a species renowned for its genetic diversity and resilience. Accurate genomic prediction of traits such as food intake has significant potential for both evolutionary biology and agricultural applications. By identifying genetic markers that underline adaptive traits across varying environmental contexts, these findings could inform strategies for improving food intake-related traits in other organisms with shared genomic features.

In this study, the predictive ability for food intake using GBLUP was relatively low, suggesting that the genetic architecture of this trait is complex and likely influenced by numerous small-effect loci. Compared to other traits such as starvation resistance and startle response—where genomic prediction reached moderate levels (0.24–0.28; Ober et al., 2012)—the correlation for food intake was notably lower. This complexity presents challenges for genomic prediction, as small-effect loci may interact in intricate ways that are difficult to capture using traditional models. Despite this, we consistently observed higher predictive accuracy in males than in females. This sex-specific trend aligns with previous studies on traits such as chill coma recovery (Ober et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2016), suggesting underlying sex-linked mechanisms that modulate genomic predictability.

The sexual dimorphism in food consumption, with females consuming more than males on average (Garlapow et al., 2015), further supports the idea of a sex-specific genetic architecture. Our finding that males exhibit higher predictive accuracy for food intake suggests that hormonal regulation, reproductive stage, differential expression of X-linked genes, or sex-specific gene-by-environment interactions may influence phenotypic variance (Camus et al., 2018; Malita et al., 2022). This interpretation is supported by a genome-wide association study in the DGRP, which identified sex-specific candidate loci affecting food intake, and functional validation using RNAi knockdown confirmed 24 of 31 candidate genes (~77%) as causal (Garlapow et al., 2015). These findings emphasize that, despite low genome-wide predictability, certain genetic variants exert substantial, biologically meaningful effects on the trait—particularly in a sex-specific context.

Bayes B showed the opposite pattern of predictive ability compared to GBLUP, with higher predictive ability for females than for males. There were no significant differences in model performance between Bayes B and GBLUP for females, but significant differences were observed among males. A similar pattern—where Bayes B and GBLUP had comparable predictive abilities—was reported by Ober et al. (2012) in their study of starvation resistance and startle response in D. melanogaster. Our findings are consistent with theirs for females but differ for males, possibly due to model performance being influenced by interactions between sex and traits.

Several factors may account for the limited predictive ability observed in our study. The relatively small training population size in our 5-fold cross-validation (approximately 140 individuals per fold) likely constrained the model's power. As highlighted by Daetwyler et al. (2010), prediction accuracy is strongly influenced by the size of the training population. In support of this, Ober et al. (2012) demonstrated that increasing the number of sequenced lines improves predictions for starvation resistance and startle response in Drosophila. Therefore, future genomic prediction efforts for food intake would benefit from expanding the training set, which could lead to more robust predictions.

Finally, while GBLUP was able to capture some sex-specific variance in predictive ability, its assumption of homogeneous marker effects across the genome may limit its effectiveness for traits with complex, heterogeneous architectures (Clark et al., 2011). In contrast, Bayesian approaches like Bayes B, which allow for variable selection and differential shrinkage of marker effects (Meuwissen et al., 2001), offer a promising alternative. Our findings suggest that Bayes B may be better suited for predicting phenotypes in males for D. melanogaster, where trait architectures could involve a few large-effect loci rather than a highly polygenic background. However, it is possible that the advantages of Bayes B are more pronounced with larger training datasets, as Bayesian models typically benefit from increased sample sizes. Overall, these results highlight that the sex of the individual should be considered when selecting genomic prediction models, as accounting for sex-specific genetic architectures could improve predictive accuracy. Future research incorporating multi-trait models, epistatic interactions, and functional validation data may further enhance prediction and help clarify the biological mechanisms underlying food intake behavior in D. melanogaster.

References

- Beckingham, K.M.; Armstrong, J.D.; Texada, M.J.; Munjaal, R.; A Baker, D. Drosophila melanogaster--the model organism of choice for the complex biology of multi-cellular organisms. Gravit Space Biol Bull 2005, 18, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boichard, D.; Ducrocq, V.; Croiseau, P.; Fritz, S. Genomic selection in domestic animals: Principles, applications and perspectives. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2016, 339, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, B.L.; Zhou, Y.; Browning, S.R. A One-Penny Imputed Genome from Next-Generation Reference Panels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 103, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camus, M.F.; Huang, C.; Reuter, M.; Fowler, K. Dietary choices are influenced by genotype, mating status, and sex in Drosophila melanogaster. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 5385–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Clark, S.; Hickey, J.M.; van der Werf, J.H. Different models of genetic variation and their effect on genomic evaluation. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2011, 43, 18–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coster, A.; Bastiaansen, J.W.; Calus, M.P.; van Arendonk, J.A.; Bovenhuis, H. Sensitivity of methods for estimating breeding values using genetic markers to the number of QTL and distribution of QTL variance. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2010, 42, 9–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daetwyler, H.D.; Pong-Wong, R.; Villanueva, B.; A Woolliams, J. The Impact of Genetic Architecture on Genome-Wide Evaluation Methods. Genetics 2010, 185, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los, G.; Hickey, J.M.; Pong-Wong, R.; Daetwyler, H.D.; Calus, M.P.L. Whole-Genome Regression and Prediction Methods Applied to Plant and Animal Breeding. Genetics 2013, 193, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.M.; Sørensen, I.F.; Sarup, P.; Mackay, T.F.; Sørensen, P. Genomic Prediction for Quantitative Traits Is Improved by Mapping Variants to Gene Ontology Categories inDrosophila melanogaster. Genetics 2016, 203, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassaby, Y.A.; Klápště, J.; Guy, R.D. Breeding without breeding: selection using the genomic best linear unbiased predictor method (GBLUP). New For. 2012, 43, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endelman, J.B. Ridge Regression and Other Kernels for Genomic Selection with R Package rrBLUP. Plant Genome 2011, 4, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlapow, M.E.; Huang, W.; Yarboro, M.T.; Peterson, K.R.; Mackay, T.F.C. Quantitative Genetics of Food Intake in Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0138129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianola, D. Priors in Whole-Genome Regression: The Bayesian Alphabet Returns. Genetics 2013, 194, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, B.J.; Visscher, P.M.; Goddard, M.E. Increased accuracy of artificial selection by using the realized relationship matrix. Genet. Res. 2009, 91, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, C.R. Best Linear Unbiased Estimation and Prediction under a Selection Model. 1975, 31, 423–47. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sillanpää, M.J. Estimation of Quantitative Trait Locus Effects with Epistasis by Variational Bayes Algorithms. Genetics 2012, 190, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sillanpää, M.J. Overview of LASSO-related penalized regression methods for quantitative trait mapping and genomic selection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malita, A.; Kubrak, O.; Koyama, T.; Ahrentløv, N.; Texada, M.J.; Nagy, S.; Halberg, K.V.; Rewitz, K. A gut-derived hormone suppresses sugar appetite and regulates food choice in Drosophila. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 1532–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Meuwissen, T.H.; Hayes, B.J.; E Goddard, M. Prediction of Total Genetic Value Using Genome-Wide Dense Marker Maps. Genetics 2001, 157, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, T.; Goddard, M. Accurate Prediction of Genetic Values for Complex Traits by Whole-Genome Resequencing. Genetics 2010, 185, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, U.; Ayroles, J.F.; Stone, E.A.; Richards, S.; Zhu, D.; Gibbs, R.A.; Stricker, C.; Gianola, D.; Schlather, M.; Mackay, T.F.C.; et al. Using Whole-Genome Sequence Data to Predict Quantitative Trait Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, U.; Huang, W.; Magwire, M.; Schlather, M.; Simianer, H.; Mackay, T.F.C. Accounting for Genetic Architecture Improves Sequence Based Genomic Prediction for a Drosophila Fitness Trait. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0126880–e0126880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepho, H.P. Ridge Regression and Extensions for Genomewide Selection in Maize. Crop. Sci. 2009, 49, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rius-Vilarrasa, E.; Brøndum, R.; Strandén, I.; Guldbrandtsen, B.; Strandberg, E.; Lund, M.; Fikse, W. Influence of model specifications on the reliabilities of genomic prediction in a Swedish–Finnish red breed cattle population. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2012, 129, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanRaden, P. Efficient Methods to Compute Genomic Predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 4414–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, B.L. The Generalization of `Student's' Problem when Several Different Population Variances are Involved. Biometrika 1947, 34, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L. , Zhang, H., Li, X., Zhao, S., & Liu, X. (2022). hibayes: an R package to fit individual-level, summary-level and single-step Bayesian regression models for genomic prediction and genome-wide association studies. BioRxiv, 2022-02.

- Zhong, S.; Dekkers, J.C.M.; Fernando, R.L.; Jannink, J.-L. Factors Affecting Accuracy From Genomic Selection in Populations Derived From Multiple Inbred Lines: A Barley Case Study. Genetics 2009, 182, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).