Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

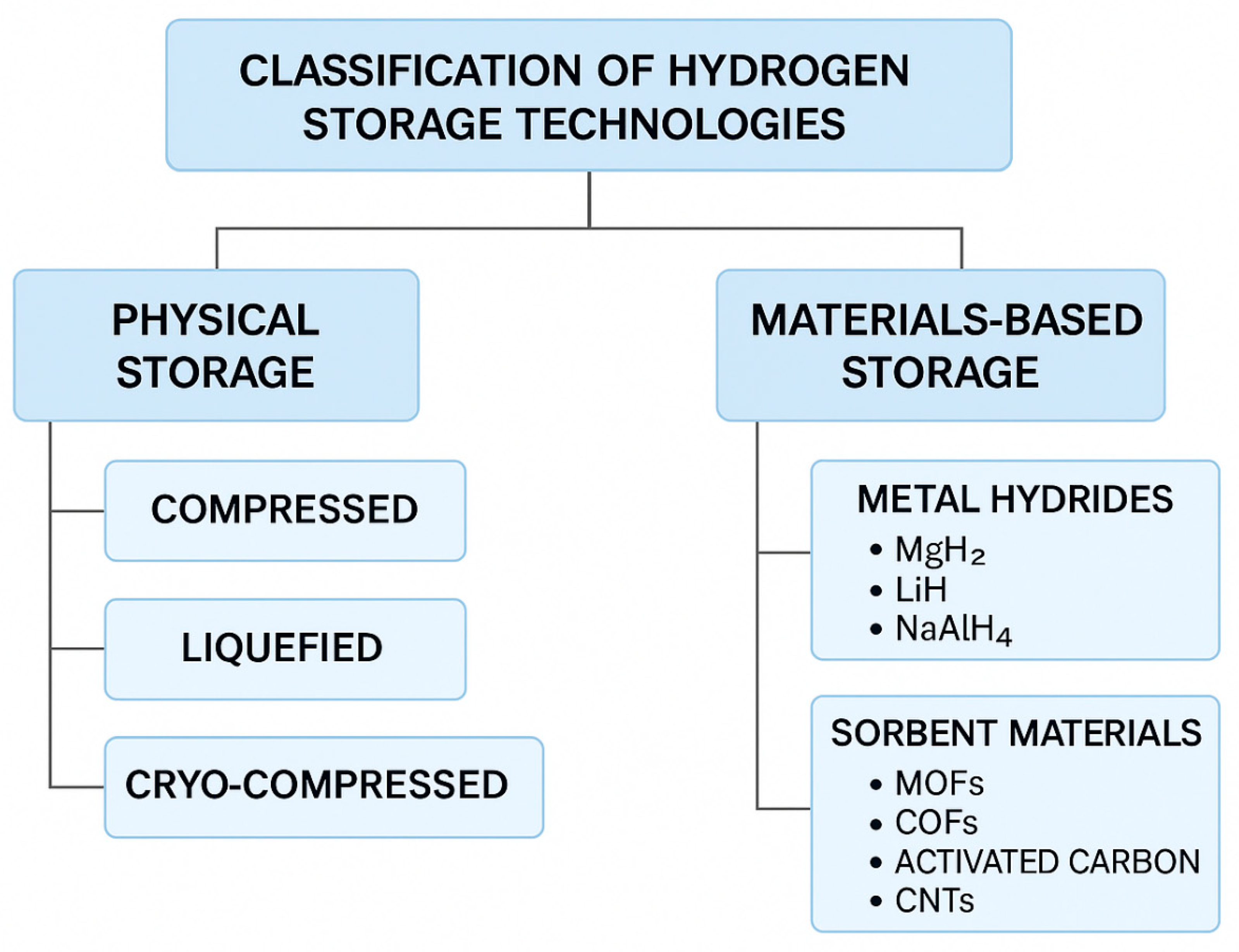

2. Classification of Hydrogen Storage Methods

- •

- Physical Storage: Compressed, Liquefied, Cryo-compressed

- •

- Materials-Based Storage:

- ▪

- Metal Hydrides (MgH2, LiH, NaAlH4, etc.)

- ▪

- Sorbent Materials (MOFs, COFs, Activated Carbon)

2.1. Solid-State Physical Storage Material

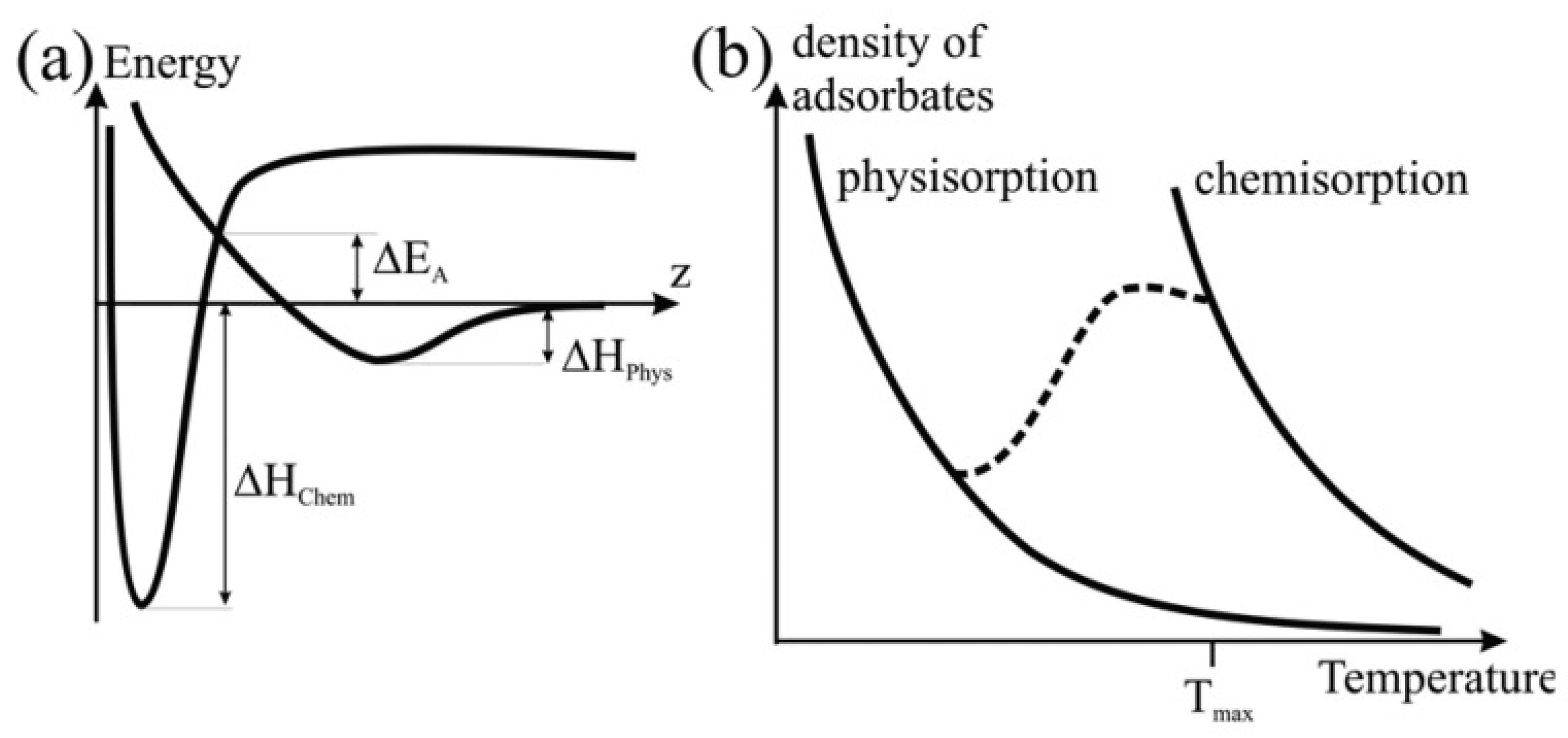

2.1.1. Mechanism of Hydrogen Adsorption on Solid-State Physical Storage Materials

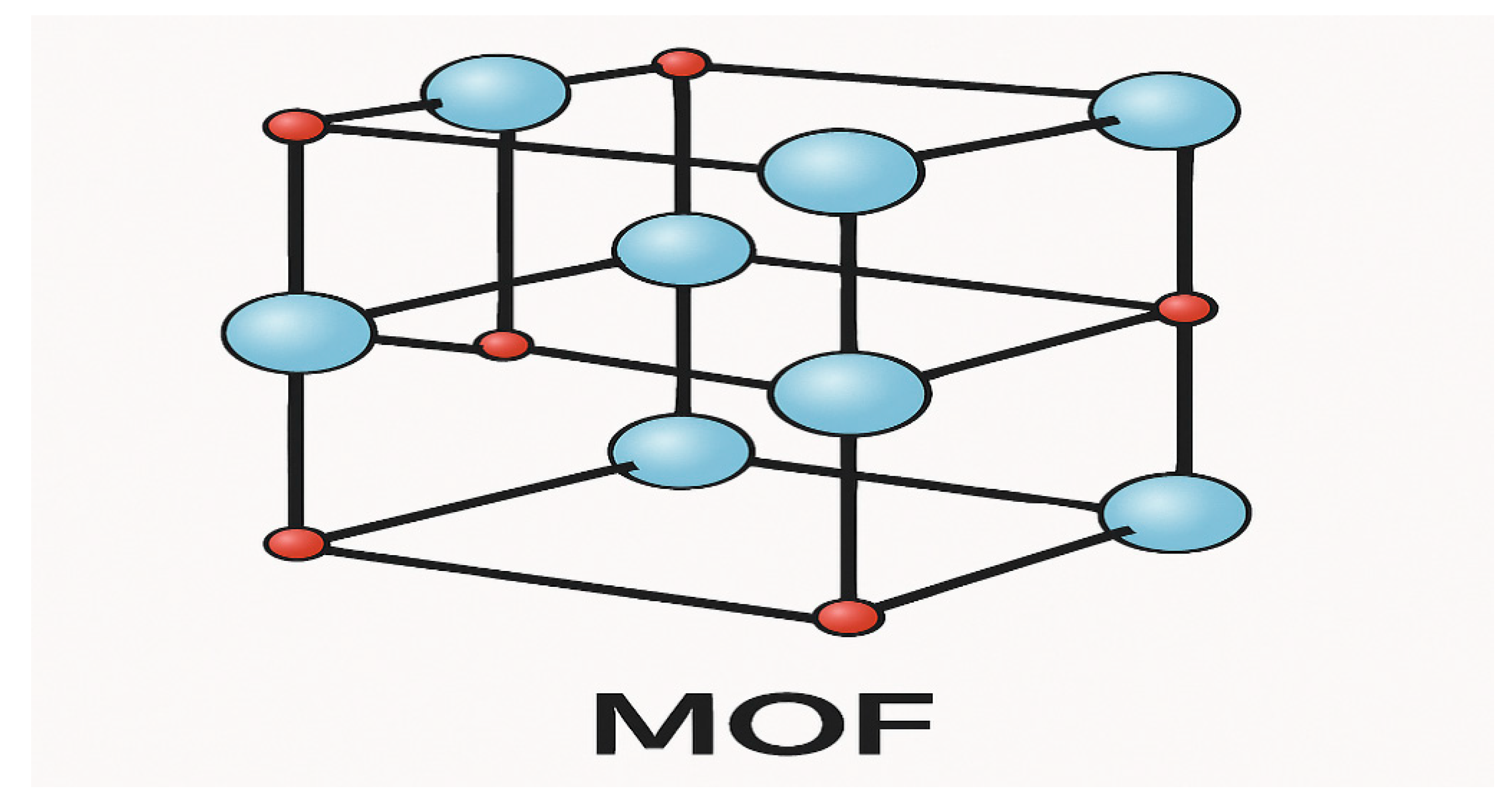

2.2. Metalorganic Framework (MOF)

2.3. Covalent Organic Framework (COF)

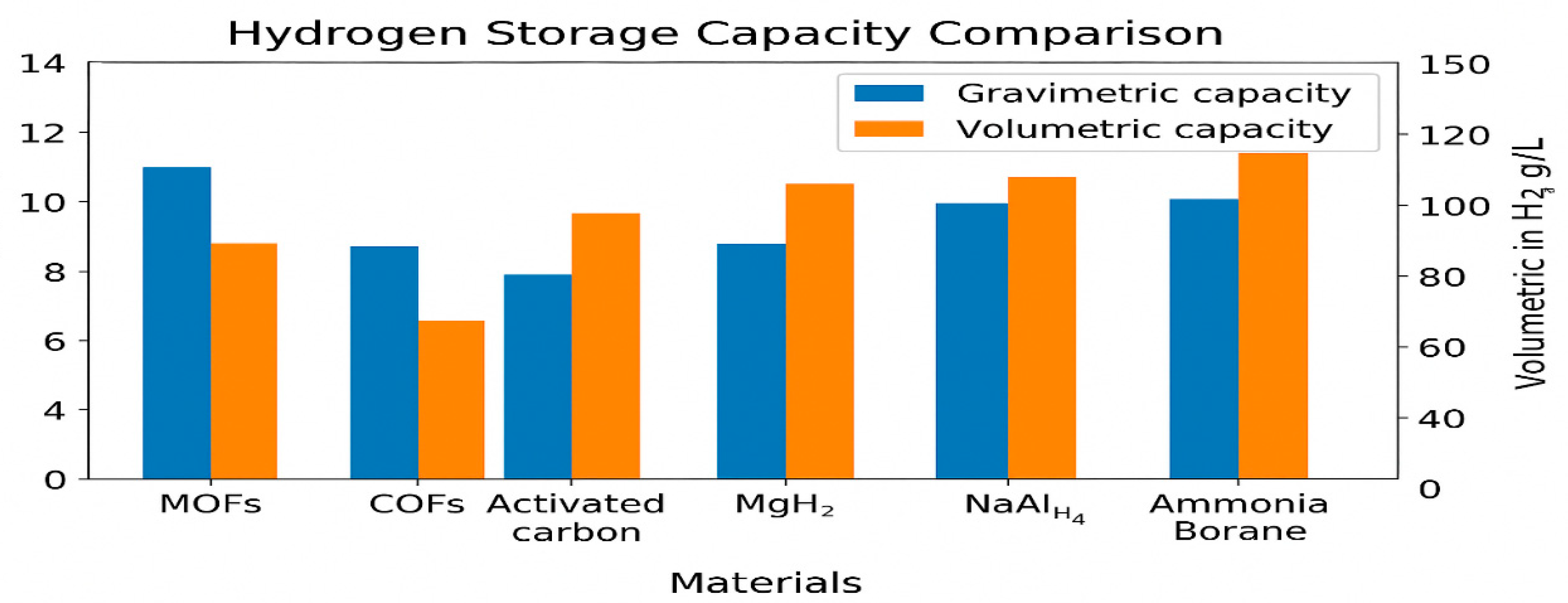

2.4. Hydrogen Storage Technology

2.5. Compressed Hydrogen Technique

- Type 1(seamless steel) withstands high pressure, has low energy density, and is heavier than other types. Withstand pressure up to 20MPa.

- Type 2 (steel liner reinforced with a composite wrap) is higher and more efficient than type 1; however, it is expensive to produce. It can withstand pressure of 30MPa and is suitable for industrial applications.

- Type 3( seamless aluminum liner fully enveloped by a composite material layer) is low-weight and maintains higher pressure. However, it has low thermal energy, so it is not ideal for hydrogen storage. It can withstand up to 70MPa.

- Type 4 (plastic liner fully wrapped with composite materials) vessels can withstand up to 70MPa and are lighter than all other vessels. However, they are expensive, which limits their usage.

2.6. Liquefied Hydrogen Storage

2.7. Cryo-Compressed Hydrogen Storage

2.8. Metal Hydrides

2.8.1. Magnasium Hydroxide MgH2

2.8.2. Lithium Hydride (LiH)

2.8.3. Sodium Alanate (NaAlH4)

2.8.4. Ammonia Borane (AB, H3NBH3)

2.9. Metal Nitrides, Including Amides (M(NH2)x) and Imides (M(NH)x)

2.10. Activated Carbon and Carbon Nanomaterials

3. Designing Material for Hydrogen Storage

3.1. Design Considerations and Strategies for Hydrogen Storage Material

4. High-Throughput Computational Screening and Machine Learning

4.1. Designing New Materials Is a Complex Task with Many Parameters, Methods, and Paths

4.2. ML Techniques Can Be Grouped Broadly into Four General Categories:

- First-Principles Methods Accurately Calculate Essential Physical.

Conclusion

References

- Ramesh, S. (2025). Renewable Energy Technologies. In The Political Economy of Contemporary Human Civilisation, Volume II: From Quantum Computing and Nuclear Fusion to War and Conflict (pp. 183-218). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Bashir, M. F., Pata, U. K., & Shahzad, L. (2025). Linking climate change, energy transition and renewable energy investments to combat energy security risks: Evidence from top energy consuming economies. Energy, 314, 134175. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, P., Edenhofer, O., Kleinnijenhuis, A., Rockström, J., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2025). Why coalitions of wealthy nations should fund others to decarbonize. [CrossRef]

- Awan, T. I., Afsheen, S., & Mushtaq, A. (2025). Carbon-Free Energy—Free Energy Supply. In Influence of Noble Metal Nanoparticles in Sustainable Energy Technologies (pp. 19-47). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Dave, G., Patel, T., & Mitra, S. (2025). Global scenario on renewable energy and net zero goal emphasizing Indian standpoint: a short review. Energy Systems, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Awan, T. I., Afsheen, S., & Mushtaq, A. (2025). Introduction to Sustainable Energy and Climate Change. In Influence of Noble Metal Nanoparticles in Sustainable Energy Technologies (pp. 1-18). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Dinçer, S. (2025). ALTERNATIVE RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES IN THE CONTEXT OF GLOBAL ENERGY CRISES AND SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENT. Kapanaltı Dergisi, (7), 19-30. [CrossRef]

- Zafarullah, H., & Mehnaz, M. (2025). Balancing economic growth and sustainability for environmental protection in Southeast Asia: a regional perspective. Southeast Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., & Nouseen, S. (2025). Tackling economic policy uncertainty and improving energy security through clean energy change. Energy, 315, 134356. [CrossRef]

- Afrane, S., Ampah, J. D., Adun, H., Chen, J. L., Zou, H., Mao, G., & Yang, P. (2025). Targeted carbon dioxide removal measures are essential for the cost and energy transformation of the electricity sector by 2050. Communications Earth & Environment, 6(1), 227. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Li, K., Wen, D., Hao, W., Jin, X., & Jia, L. (2025). Prediction of energy need and zero-carbon China with renewables. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy, 20(1), 2456060. [CrossRef]

- Mghazli, M. O., Bahrar, M., Charai, M., Lamdouar, N., & El Mankibi, M. (2025). Advancing the Net Zero emission building concept: Integrating photovoltaics and electrical storage for NZEB environmental performance in different energy and climate contexts. Solar Energy, 290, 113331. [CrossRef]

- Giama, E., Kyriaki, E., Fokaides, P., & Papadopoulos, A. M. (2025). Energy policy towards nZEB: The Hellenic and Cypriot case. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, 47(1), 5282-5295. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Liang, L., Xie, J., & Zhang, G. (2025). Optimal emission reduction strategy for carbon neutral target: cap-and-trade policy and supply chain contracts with uncertain demand under SDG 13-climate action. Annals of Operations Research, 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Hunjra, A. I., Mishra, T., & Zhao, S. (2025). Carbon neutrality and synergy between industrial and innovation chains: green finance perspective. International Journal of Production Research, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Bera, M., Das, S., Garai, S., Dutta, S., Choudhury, M. R., Tripathi, S., & Chatterjee, G. (2025). Advancing energy efficiency: innovative technologies and strategic measures for achieving net zero emissions. Carbon Footprints, 4(1), N-A. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Aisha. Energy Technology. Publifye AS, 2025.

- Chauhan, I., AbdelRahman, M. A., Scopa, A., Mangat, A., & Kumar, A. (2025). Managing Livestock Manure: Mitigating Greenhouse Gas Emissions. In Smart Technologies for Sustainable Livestock Systems (pp. 35-52). CRC Press.

- Henao, D. C. R., Castrillón, D. Z., Colorado, A., & Amell, A. A. (2025). Impact of hydrogen addition to natural gas mixtures in a premixed combustion system and heat transfer by infrared radiation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. [CrossRef]

- Maka, A. O., & Mehmood, M. (2024). Green hydrogen energy production: current status and potential. Clean Energy, 8(2), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Kim, Y. J., & Lee, M. C. (2025). Navigating stakeholder perspectives on hydrogen generation technologies: A Q-methodology study of current hydrogen production policy in South Korea. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 113, 777-786. [CrossRef]

- Permana, C. T., Handoko, C. T., & Gomonov, K. (2025). Hydrogen’s Potential and Policy Pathways for Indonesia’s Energy Transition: The Actor-Network Analysis. Unconventional Resources, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Laimon, M., & Yusaf, T. (2024). Towards energy freedom: Exploring sustainable solutions for energy independence and self-sufficiency using integrated renewable energy-driven hydrogen system. Renewable Energy, 222, 119948. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R., Panwar, N. L., Agarwal, C., & Gupta, T. (2024). A comprehensive review on unleashing the power of hydrogen: Revolutionizing energy systems for a sustainable future. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, M. K., Al-Mohamad, R., Salameh, T., & Alkhalidi, A. (2024). Strategies to promote nuclear energy utilization in hydrogen production. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 82, 36-46. [CrossRef]

- Swadi, M., Kadhim, D. J., Salem, M., Tuaimah, F. M., Majeed, A. S., & Alrubaie, A. J. (2024). Investigating and predicting the role of photovoltaic, wind, and hydrogen energies in sustainable global energy evolution. Global Energy Interconnection, 7(4), 429-445. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., & Lao, G. (2025). Hydrogen production from renewable sources: Bridging the gap to sustainable energy and economic viability. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 117, 121-134. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Wang, Z., Meng, Q., & White, S. (2025). Advancements in hydrogen storage technologies: Enhancing efficiency, safety, and economic viability for sustainable energy transition. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 105, 10-22. [CrossRef]

- Gulraiz, A., Al Bastaki, A. J., Magamal, K., Subhi, M., Hammad, A., Allanjawi, A., ... & Said, Z. (2025). Energy Advancements and Integration Strategies in Hydrogen and Battery Storage for Renewable Energy Systems. iScience. [CrossRef]

- Permana, C. T., Handoko, C. T., & Gomonov, K. (2025). Hydrogen’s Potential and Policy Pathways for Indonesia’s Energy Transition: The Actor-Network Analysis. Unconventional Resources, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnin, A. S., Wacławiak, K., Humayun, M., Zhang, S., & Ullah, H. (2025). Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts, 15(3), 260.

- Fang, W., Ding, C., Chen, L., Zhou, W., Wang, J., Huang, K., ... & Wang, J. (2024). Review of hydrogen storage technologies and the crucial role of environmentally friendly carriers. Energy & Fuels, 38(15), 13539-13564.

- Aziz, M. (2021). Liquid hydrogen: A review on liquefaction, storage, transportation, and safety. Energies, 14(18), 5917. [CrossRef]

- Karrabi, M., Jabari, F., & Foroud, A. A. (2025). 4 A Comprehensive Review on Green Hydrogen, CCSU, and Methane Production Technologies. Power-to-X in Regional Energy Systems: Planning, Operation, Control, and Market Perspectives, 86.

- Cavaliere, P. (2025). Hydrogen: Energy Vector and Fuel. In Hydrogen Embrittlement in Metals and Alloys (pp. 1-155). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Korkua, S. K., Thubsuang, U., Sakphrom, S., Dash, S. K., Tesanu, C., & Thinsurat, K. (2025). Simulation-Driven Optimization of Thermochemical Energy Storage in SrCl2-Based System for Integration with Solar Energy Technology. Inventions, 10(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Gharehveran, S. S., Shirini, K., & Abdolahi, A. (2025). Optimizing Energy Storage Solutions for Grid Resilience: A Comprehensive Overview.

- Abdin, Z. (2024). Shaping the stationary energy storage landscape with reversible fuel cells. Journal of Energy Storage, 86, 111354. [CrossRef]

- Baricco, M., Dematteis, E. M., Barale, J., Costamagna, M., Sgroi, M. F., Palumbo, M., & Rizzi, P. (2024). Hydrogen storage and handling with hydrides. Pure and Applied Chemistry, 96(4), 511-524. [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A. A., Kalogiannis, T., Van Mierlo, J., & Berecibar, M. (2022). A comprehensive review of stationary energy storage devices for large scale renewable energy sources grid integration. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 159, 112213. [CrossRef]

- Usman, M. R. (2022). Hydrogen storage methods: Review and current status. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 167, 112743. [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, P. K., Chandu, B., Motapothula, M. R., & Puvvada, N. (2024). Potential benefits, challenges and perspectives of various methods and materials used for hydrogen storage. Energy & Fuels, 38(4), 2630-2653. [CrossRef]

- Papoutsakis, A. (2025). Techno-economic feasibility study of retrofitting a double-ended Ro-Pax vessel with hydrogen fuel cells.

- Mekonnin, A. S., Wacławiak, K., Humayun, M., Zhang, S., & Ullah, H. (2025). Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts, 15(3), 260.

- Sumathi, S. V., Rahman, R. K., Iyer, R., Freund, S., & Wygant, K. (2025). Gas-to-liquids and other decarbonized energy carriers. In Energy Transport Infrastructure for a Decarbonized Economy (pp. 397-412). Elsevier.

- Genovese, M., Blekhman, D., & Fragiacomo, P. (2024). An exploration of safety measures in hydrogen refueling stations: delving into hydrogen equipment and technical performance. Hydrogen, 5(1), 102-122. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M. (2021). Liquid hydrogen: A review on liquefaction, storage, transportation, and safety. Energies, 14(18), 5917. [CrossRef]

- Genovese, M., Blekhman, D., & Fragiacomo, P. (2024). An exploration of safety measures in hydrogen refueling stations: delving into hydrogen equipment and technical performance. Hydrogen, 5(1), 102-122. [CrossRef]

- Mboyi, C. D., Poinsot, D., Roger, J., Fajerwerg, K., Kahn, M. L., & Hierso, J. C. (2021). The hydrogen-storage challenge: nanoparticles for metal-catalyzed ammonia borane dehydrogenation. Small, 17(44), 2102759.

- Park, Y. K., & Kim, B. S. (2023). Catalytic removal of nitrogen oxides (NO, NO2, N2O) from ammonia-fueled combustion exhaust: A review of applicable technologies. Chemical Engineering Journal, 461, 141958. [CrossRef]

- Cechanaviciute, I., & Schuhmann, W. (2025). Electrocatalytic Ammonia Oxidation Reactions: Selective Formation of Nitrite and Nitrate as Value-Added Products. ChemSusChem, e202402516. [CrossRef]

- Khan, D., & Ong, W. J. (2025). Tailoring Hydrogen Storage Materials Kinetics and Thermodynamics Through Nanostructuring, and Nanoconfinement With In-Situ Catalysis. Interdisciplinary Materials.

- Boretti, A. (2025). A Narrative Review of Metal and Complex Hydride Hydrogen Storage. Next Research, 100226. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., Acharya, S. K., Patnaik, P. P., Panda, B. S., Roy, A., Saha, S., & Singh, K. A. (2025). Low-pressure hydrogen storage using different metal hydrides: a review. International Journal of Global Warming, 35(2-4), 306-332. [CrossRef]

- Davis Cortina, M., Romero de Terreros Aramburu, M., Neves, A. M., Hurtado, L., Jepsen, J., & Ulmer, U. (2024). The Integration of Thermal Energy Storage Within Metal Hydride Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Inorganics, 12(12), 313. [CrossRef]

- Masood, M. I. (2024). Development of biomass based activated carbons for biogas upgrade (Doctoral dissertation, Heriot-Watt University).

- Nyamathulla, S., & Dhanamjayulu, C. (2024). A review of battery energy storage systems and advanced battery management system for different applications: Challenges and recommendations. Journal of Energy Storage, 86, 111179. [CrossRef]

- Attia, N. F., Elashery, S. E., Nour, M. A., Policicchio, A., Agostino, R. G., Abd-Ellah, M., ... & Oh, H. (2024). Recent advances in sustainable and efficient hydrogen storage nanomaterials. Journal of Energy Storage, 100, 113519. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Bo, X., Xu, H., Wang, L., Daoud, W. A., & He, X. (2024). Advancing lithium-ion battery anodes towards a sustainable future: Approaches to achieve high specific capacity, rapid charging, and improved safety. Energy Storage Materials, 103696. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Bo, X., Xu, H., Wang, L., Daoud, W. A., & He, X. (2024). Advancing lithium-ion battery anodes towards a sustainable future: Approaches to achieve high specific capacity, rapid charging, and improved safety. Energy Storage Materials, 103696. [CrossRef]

- Vanaraj, R., Arumugam, B., Mayakrishnan, G., & Kim, S. C. (2025). Advancements in Metal-Ion Capacitors: Bridging Energy and Power Density for Next-Generation Energy Storage. Energies, 18(5), 1253. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y. Application of different porous materials for hydrogen storage. J Phys. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Erdogan FO, Celik C, Turkmen AC, Sadak AE, Cücü E. Hydrogen storage behavior of zeolite/graphene, zeolite/multiwalled carbon nanotube and zeolite/green plum stones-based activated carbon composites. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Broom DP, Webb CJ, Hurst KE, Parilla PA, Gennett T, Brown CM, Zacharia R, Tylianakis E, Klontzas E, Froudakis GE, Steriotis TA, Trikalitis PN, Anton DL, Hardy B, Tamburello D, Corgnale C, Van Hassel BA, Cossement D, Chahine R, Hirscher M. Outlook and challenges for hydrogen storage in nanoporous materials. Appl Phys A. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Xue Z, Niu K, Liu X, Lv NW, Zhang B, Li Z, Zeng H, Ren Y, Wu Y, Zhang Y. Li–fluorine codoped electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced hydrogen storage. RSC Adv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Stoddart A. Predicting perfect pores. Nat Rev Mater. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Steele, W. (1993). Molecular interactions for physical adsorption. Chemical reviews, 93(7), 2355-2378.

- Munir A, Ahmad A, Sadiq MT, Sarosh A, Abbas G, Ali A. Synthesis and characterization of carbon-based composites for hydrogenstorage application. Eng Proc. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Perrella, F., Petrone, A., & Rega, N. (2023). Understanding charge dynamics in dense electronic manifolds in complex environments. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 19(2), 626-639.

- Lastoskie, C. M., Quirke, N., & Gubbins, K. E. (1997). Structure of porous adsorbents: Analysis using density functional theory and molecular simulation. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis (Vol. 104, pp. 745-775). Elsevier.

- Schlyter, F. (1992). Sampling range, attraction range, and effective attraction radius: Estimates of trap efficiency and communication distance in coleopteran pheromone and host attractant systems 1. Journal of Applied Entomology, 114(1-5), 439-454.

- Züttel A. Hydrogen storage methods. The science of nature; 2004. pp. 157–172; [CrossRef]

- Tranchemontagne DJ, Mendoza-Cortes JL, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Secondary building units, nets and bonding in the chemistry of metal-organic frameworks. Chem Soc Rev. 2009.

- Yaghi OM, Kalmutzki MJ, Diercks CS. Introduction to reticular chemistry. Wiley. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Eddaoudi M, Groy TL, Yaghi OM. Establishing microporosity in open metal-organic frameworks: gas sorption isotherms for Zn(BDC) (BDC = 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylate). J Am Chem Soc. 1998.

- Li H, Eddaoudi M, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Design and Synthesis of an Exceptionally Stable and Highly Porous Metal-organic Framework. Nature. 1999.

- Kaye SS, Dailly A, Yaghi OM, Long JR. Impact of preparation and handling on the hydrogen storage properties of Zn4O(1,4-benzenedicarboxylate)3 (MOF-5). J Am Chem Soc. 2007.

- Feng X, Ding X, Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks. Chem Soc rev. 2012.

- Huang N, Wang P, Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks: a materials platform for structural and functional designs. Nat Rev Mater. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks: an amazing chemistry platform for designing polymers. Chem. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lohse MS, Bein T. Covalent organic frameworks: structures, synthesis, and applications. Adv Func Mat. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks: a molecular platform for designer polymeric architectures and functional materials. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dixit M, Maark TA, Pal S. Ab initio and periodic DFT investigation of hydrogen storage on light metal-decorated MOF-5. Intl J Hydrogen Energy. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Butler KT, Hendon CH, Walsh A. Electronic chemical potentials of porous metal–organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bodrenko IV, Avdeenkov AV, Bessarabov DG, Bibikov AV, Nikolaev AV, Taran MD, Tkalya EV. Hydrogen storage in aromatic carbon ring based molecular materials decorated with alkali or alkali-earth metals. J Phy Chem C. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Bordiga S, Vitillo JG, Ricchiardi G, Regli L, Cocina D, Zecchina A, Arstad B, Bjørgen M, Hafizovic J, Lillerud KP. Interaction of hydrogen with MOF-5. J of Phy Chem B. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Rowsell J, Yaghi O. Effects of functionalization, catenation, and variation of the metal oxide and organic linking units on the lowpressure hydrogen adsorption properties of metal−organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Tashie-Lewis BC, Nnabuife SG. Hydrogen production, distribution, storage andpower conversion in a hydrogen economy - a technology review. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2021;8:100172.

- Zhang L, Jia CQ, Bai FQ, Wang WS, An SY, Zhao KY, et al. A comprehensive review of the promising clean energy carrier: hydrogen production, transportation, storage, and utilization (HPTSU) technologies. Fuel 2024;355:129455.

- Du ZM, Liu CM, Zhai JX, Guo XY, Xiong YL, Su W, et al. A review of hydrogen purification technologies for fuel cell vehicles. Catalysts 2021;11:393. [CrossRef]

- Qazi UY. Future of hydrogen as an alternative fuel for next-generation industrial applications; challenges and expected opportunities. Energies 2022;15:4741. [CrossRef]

- Usman MR. Hydrogen storage methods: review and current status. Renew Sustain. Energy Rev 2022;167:112743. [CrossRef]

- Demirocak DE. Hydrogen storage technologies. Nanostructured Materials for Next-Generation Energy Storage and Conversion: Hydrogen Production, Storage, and Utilization 2017:117–42. [CrossRef]

- Abe JO, Popoola A, Ajenifuja E, Popoola OM. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: review and recommendation. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019;44:15072–86.

- Ahluwalia RK, Hua T, Peng J. On-board and Off-board performance of hydrogen storage options for light-duty vehicles. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2012;37:2891–910. [CrossRef]

- Schlapbach L, Züttel A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications.Nature 2001;414:353–8.

- Mekonnin, A. S., Wacławiak, K., Humayun, M., Zhang, S., & Ullah, H. (2025). Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts, 15(3), 260.

- Ahad, M. T., Bhuiyan, M. M. H., Sakib, A. N., Becerril Corral, A., & Siddique, Z. (2023). An overview of challenges for the future of hydrogen. Materials, 16(20), 6680. [CrossRef]

- Barisic, V. (2024). Roadmap towards utilization of hydrogen technologies in the energy network (Bachelor's thesis, NTNU).

- Kamran, M., & Turzyński, M. (2024). Exploring hydrogen energy systems: A comprehensive review of technologies, applications, prevailing trends, and associated challenges. Journal of Energy Storage, 96, 112601. [CrossRef]

- Petitpas, G., Bénard, P., Klebanoff, L. E., Xiao, J., & Aceves, S. (2014). A comparative analysis of the cryo-compression and cryo-adsorption hydrogen storage methods. International journal of hydrogen energy, 39(20), 10564-10584. [CrossRef]

- Brunner, T., & Kircher, O. (2016). Cryo-compressed hydrogen storage. Hydrogen science and engineering: materials, processes, systems and technology, 711-732.

- Yanxing Z, Maoqiong G, Yuan Z, Xueqiang D, Jun S. Thermodynamics analysis of hydrogen storage based on compressed gaseous hydrogen, liquid hydrogen and cryo-compressed hydrogen. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019;44:16833–40. [CrossRef]

- Kukkapalli VK, Kim S, Thomas SA. Thermal management techniques in metal hydrides for hydrogen storage applications: a review. Energies 2023;16:3444. [CrossRef]

- Lototskyy MV, Tolj I, Pickering L, Sita C, Barbir F, Yartys V. The use of metal hydrides in fuel cell applications. Prog Nat Sci: Mater Int 2017;27:3–20. [CrossRef]

- Tashie-Lewis BC, Nnabuife SG. Hydrogen production, distribution, storage and power conversion in a hydrogen economy - a technology review. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2021;8:100172. [CrossRef]

- Manoharan K, Sundaram R, Raman K. Expeditious re-hydrogenation kinetics of ball-milled magnesium hydride (B-MgH2) decorated acid-treated halloysite nanotube (A-HNT)/polyaniline (PANI) nanocomposite (B-MgH2/A-HNT/PANI) for fuel cell applications. Ionics 2023:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovi´c B, Ritter A, Spliethoff B. Active MgH2 Mg systems for reversible chemical energy storage. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2003;29:223–34.

- Wang L, Zhang L, Lu X, Wu F, Sun X, Zhao H, et al. Surprising cocktail effect in high entropy alloys on catalyzing magnesium hydride for solid-state hydrogen storage. Chem Eng J 2023;465:142766. [CrossRef]

- Schneemann A, White JL, Kang S, Jeong S, Wan LF, Cho ES, et al. Nanostructured metal hydrides for hydrogen storage. Chem Rev 2018;118:10775–839. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Ding Z, Li Y-T, Li S-Y, Wu P-K, Hou Q-H, et al. Recent advances in kinetic and thermodynamic regulation of magnesium hydride for hydrogen storage. Rare Met 2023:1–22. [CrossRef]

- El-Eskandarany MS, AlMatrouk H, Shaban E, Al-Duweesh A. Effect of the nanocatalysts on the thermal stability and hydrogenation/dehydrogenation kinetics of MgH2 nanocrystalline powders. Mater Today Proc 2016;3:2608–16.

- Zhou C, Peng Y, Zhang Q. Growth kinetics of MgH2 nanocrystallites prepared by ball milling. J Mater Sci Technol 2020;50:178–83. [CrossRef]

- Shinde S, Kim D-H, Yu J-Y, Lee J-H. Self-assembled air-stable magnesium hydride embedded in 3-D activated carbon for reversible hydrogen storage. Nanoscale 2017;9:7094–103. [CrossRef]

- Meng Y, Ju S, Chen W, Chen X, Xia G, Sun D, et al. Design of bifunctional Nb/V interfaces for improving reversible hydrogen storage performance of MgH2. Small Structures 2022;3:2200119.

- Bramwell PL, Ngene P, de Jongh PE. Carbon supported lithium hydride nanoparticles: impact of preparation conditions on particle size and hydrogen sorption. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2017;42:5188–98. [CrossRef]

- Milanese C, Jensen TR, Hauback BC, Pistidda C, Dornheim M, Yang H, et al. Complex hydrides for energy storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019;44:7860–74.

- Bahou S, Labrim H, Lakhal M, Ez-Zahraouy H. Improving the hydrogen storage properties of lithium hydride (LiH) by lithium vacancy defects: ab initio calculations. Solid State Commun 2023;371:115167. [CrossRef]

- Vajo JJ, Mertens F, Ahn CC, Bowman RC, Fultz B. Altering hydrogen storage properties by hydride destabilization through alloy formation:: LiH and MgH destabilized with Si. J Phys Chem B 2004;108:13977–83. [CrossRef]

- Abbas MA, Grant DM, Brunelli M, Hansen TC, Walker GS. Reducing the dehydrogenation temperature of lithium hydride through alloying with germanium. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2013;15:12139–46. [CrossRef]

- Jain A, Kawasako E, Miyaoka H, Ma T, Isobe S, Ichikawa T, et al. Destabilization of LiH by Li insertion into Ge. J Phys Chem C 2013;117:5650–7. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Quadir MZ, Aguey-Zinsou KF. Ni coated LiH nanoparticles for reversible hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2016;41:6376–86. [CrossRef]

- Pluengphon P, Tsuppayakorn-aek P, Inceesungvorn B, Ahuja R, Bovornratanaraks T. Formation of lightweight ternary polyhydrides and their hydrogen storage mechanism. J Phys Chem C 2021;125:1723–30. [CrossRef]

- Miyaoka H, Ishida W, Ichikawa T, Kojima Y. Synthesis and characterization of lithium–carbon compounds for hydrogen storage. J Alloys Compd 2011;509: 719–23. [CrossRef]

- Schneemann A, White JL, Kang S, Jeong S, Wan LF, Cho ES, et al. Nanostructured metal hydrides for hydrogen storage. Chem Rev 2018;118:10775–839. [CrossRef]

- Beatrice CAG, Moreira BR, de Oliveira AD, Passador FR, Neto GRD, Leiva DR, et al. Development of polymer nanocomposites with sodium alanate for hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2020;45:5337–46. [CrossRef]

- Ren Z, Zhang X, Li H-W, Huang Z, Hu J, Gao M, et al. Titanium hydride nanoplates enable 5 wt% of reversible hydrogen storage by sodium alanate below 80◦ C. Research. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li YT, Fang F, Fu HL, Qiu JM, Song Y, Li YS, et al. Carbon nanomaterial-assisted morphological tuning for thermodynamic and kinetic destabilization in sodium alanates. J Mater Chem A 2013;1:5238–46. [CrossRef]

- Hudson MSL, Raghubanshi H, Pukazhselvan D, Srivastava ON. Carbon nanostructures as catalyst for improving the hydrogen storage behavior of sodium aluminum hydride. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2012;37:2750–5. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Yao Z, Wang X, Zhu Y, Chen Y. Review on hydrogen production from catalytic ammonia borane methanolysis: advances and perspectives. Energy Fuels 2022;36:11745–59. [CrossRef]

- Tang Z, Li S, Yang Z, Yu X. Ammonia borane nanofibers supported by poly (vinyl pyrrolidone) for dehydrogenation. J Mater Chem 2011;21:14616–21. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Cheng Y, Fan Y, Lu X, Li L, Liu B, et al. Metal-catalyzed hydrolysis of ammonia borane: mechanism, catalysts, and challenges. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2020;45:30325–40. [CrossRef]

- Akbayrak S, ¨Ozkar S. Ammonia borane as hydrogen storage materials. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2018;43:18592–606.

- Sakintuna B, Lamari-Darkrim F, Hirscher M. Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2007;32:1121–40.

- Che H, Wu Y, Wang X, Liu H, Yan M. Improved hydrogen storage properties of Li- Mg-N-H system by lithium vanadium oxides. J Alloys Compd 2023;931:167603. [CrossRef]

- Durbin D, Malardier-Jugroot C. Review of hydrogen storage techniques for on board vehicle applications. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2013;38:14595–617.

- Shindo K, Kondo T, Arakawa M, Sakurai Y. Hydrogen adsorption/desorption properties of mechanically milled activated carbon. J Alloys Compd 2003;359: 267–71. [CrossRef]

- Wr´obel-Iwaniec I, Díez N, Gryglewicz G. Chitosan-based highly activated carbons for hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2015;40:5788–96.

- Akasaka H, Takahata T, Toda I, Ono H, Ohshio S, Himeno S, et al. Hydrogen storage ability of porous carbon material fabricated from coffee bean wastes. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2011;36:580–5. [CrossRef]

- Dillon AC, Jones K, Bekkedahl T, Kiang C, Bethune D, Heben M. Storage of hydrogen in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nature 1997;386:377–9. [CrossRef]

- Su Rather. Preparation, characterization and hydrogen storage studies of carbon nanotubes and their composites: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2020;45: 4653–72. [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh R, Ghaedi M, Kokhdan SN, Vashaee D. Remarkably improved electrochemical hydrogen storage by multi-walled carbon nanotubes decorated with nanoporous bimetallic Fe–Ag/TiO 2 nanoparticles. Dalton Trans 2019;48: 898–907. [CrossRef]

- Kadri A, Jia Y, Chen Z, Yao X. Catalytically enhanced hydrogen sorption in Mg- MgH2 by coupling vanadium-based catalyst and carbon nanotubes. Materials 2015;8:3491–507. [CrossRef]

- Liang H, Du X, Li J, Sun L, Song M, Li W. Manipulating active sites on carbon nanotube materials for highly efficient hydrogen storage. Appl Surf Sci 2023;619: 156740. [CrossRef]

- Lai Q, Sun Y, Wang T, Modi P, Cazorla C, Demirci UB, et al. How to design hydrogen storage materials? Fundamentals, synthesis, and storage tanks. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2019;3:1900043. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Zhao PC, Niu M, Maddy J. The survey of key technologies in hydrogen energy storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2016;41:14535–52. [CrossRef]

- Ramimoghadam D, Gray EM, Webb CJ. Review of polymers of intrinsic microporosity for hydrogen storage applications. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2016;41: 16944–65. [CrossRef]

- Kaur M, Pal K. Review on hydrogen storage materials and methods from an electrochemical viewpoint. J Energy Storage 2019;23:234–49. [CrossRef]

- Blackman JM, Patrick JW, Arenillas A, Shi W, Snape CE. Activation of carbon nanofibres for hydrogen storage. Carbon 2006;44:1376–85. [CrossRef]

- Aceves SM, Berry GD, Martinez-Frias J, Espinosa-Loza F. Vehicular storage of hydrogen in insulated pressure vessels. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2006;31:2274–83. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Adroher XC, Chen JX, Yang XG, Miller T. Three-dimensional modeling of hydrogen sorption in metal hydride hydrogen storage beds. J Power Sources 2009;194:997–1006. [CrossRef]

- Klopˇciˇc N, Grimmer I, Winkler F, Sartory M, Trattner A. A review on metal hydride materials for hydrogen storage. J Energy Storage 2023;72:108456. [CrossRef]

- Lototskyy MV, Yartys VA, Pollet BG, Bowman RC. Metal hydride hydrogen compressors: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2014;39:5818–51. [CrossRef]

- Tarasov BP, Fursikov PV, Volodin AA, Bocharnikov MS, Shimkus YY, Kashin AM, et al. Metal hydride hydrogen storage and compression systems for energy storage technologies. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021;46:13647–57. [CrossRef]

- Modi P, Aguey-Zinsou KF. Room temperature metal hydrides for stationary and heat storage applications: a review. Front Energy Res 2021;9:616115. [CrossRef]

- Salman MS, Lai QW, Luo XX, Pratthana C, Rambhujun N, Costalin M, et al. The power of multifunctional metal hydrides: a key enabler beyond hydrogen storage. J Alloys Compd 2022;920:165936.

- He T, Cao H, Chen P. Complex hydrides for energy storage, conversion, and utilization. Adv Mater 2019;31:e1902757. [CrossRef]

- Orimo S, Nakamori Y, Eliseo JR, Zuttel A, Jensen CM. Complex hydrides for hydrogen storage. Chem Rev 2007;107:4111–32.

- de Jongh PE, Adelhelm P. Nanosizing and nanoconfinement: new strategies towards meeting hydrogen storage goals. ChemSusChem 2010;3:1332–48. [CrossRef]

- Pang Y, Liu Y, Gao M, Ouyang L, Liu J, Wang H, et al. A mechanical-force-driven physical vapour deposition approach to fabricating complex hydride nanostructures. Nat Commun 2014;5:3519. [CrossRef]

- Balde CP, Hereijgers BP, Bitter JH, de Jong KP. Sodium alanate nanoparticles– linking size to hydrogen storage properties. J Am Chem Soc 2008;130:6761–5. [CrossRef]

- Pratthana C, Yang YW, Rawal A, Aguey-Zinsou KF. Nanoconfinement of lithium alanate for hydrogen storage. J Alloys Compd 2022;926:166834. [CrossRef]

- Gutowska A, Li L, Shin Y, Wang CM, Li XS, Linehan JC, et al. Nanoscaffold mediates hydrogen release and the reactivity of ammonia borane. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2005;44:3578–82. [CrossRef]

- Wahab MA, Zhao HJ, Yao XD. Nano-confined ammonia borane for chemical hydrogen storage. Front Chem Sci Eng 2012;6:27–33. [CrossRef]

- Valero-Pedraza MJ, Cot D, Petit E, Aguey-Zinsou KF, Alauzun JG, Demirci UB. Ammonia borane nanospheres for hydrogen storage. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2019; 2:1129–38. [CrossRef]

- Lai QW, Pratthana C, Yang YW, Rawal A, Aguey-Zinsou KF. Nanoconfinement of complex borohydrides for hydrogen storage. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2021;4:973–8. [CrossRef]

- Ngene P, Adelhelm P, Beale AM, de Jong KP, de Jongh PE. LiBH/SBA-15 nanocomposites prepared by melt infiltration under hydrogen pressure: synthesis and hydrogen sorption properties. J Phys Chem C 2010;114:6163–8. [CrossRef]

- Le TT, Pistidda C, Nguyen VH, Singh P, Raizada P, Klassen T, et al. Nanoconfinement effects on hydrogen storage properties of MgH and LiBH. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021;46:23723–36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang QY, Huang YK, Ma TC, Li K, Ye F, Wang XC, et al. Facile synthesis of small MgH nanoparticles confined in different carbon materials for hydrogen storage. J Alloys Compd 2020;825:153953. [CrossRef]

- Ma Z, Zhang Q, Panda S, Zhu W, Sun F, Khan D, et al. In situ catalyzed and nanoconfined magnesium hydride nanocrystals in a Ni-MOF scaffold for hydrogen storage. Sustain Energy Fuels 2020;4:4694–703. [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann C, R¨ontzsch L, Hu J, Weißg¨arber T, Kieback B, Fichtner M. Tailored heat transfer characteristics of pelletized LiNH2–MgH2 and NaAlH4 hydrogen storage materials. J Power Sources 2012;205:173–9.

- Milanese C, Garroni S, Gennari F, Marini A, Klassen T, Dornheim M, et al. Solid state hydrogen storage in alanates and alanate-based compounds: a review. Metals 2018;8:567. [CrossRef]

- Gao Q, Xia G, Yu X. Confined NaAlH(4) nanoparticles inside CeO(2) hollow nanotubes towards enhanced hydrogen storage. Nanoscale 2017;9:14612–9.

- Broom DP, Webb CJ, Fanourgakis GS, Froudakis GE, Trikalitis PN, Hirscher M. Concepts for improving hydrogen storage in nanoporous materials. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019;44:7768–79. [CrossRef]

- Shet SP, Priya SS, Sudhakar K, Tahir M. A review on current trends in potential use of metal-organic framework for hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021;46:11782–803. [CrossRef]

- Yuan S, Zou L, Qin JS, Li J, Huang L, Feng L, et al. Construction of hierarchically porous metal-organic frameworks through linker labilization. Nat Commun 2017; 8:15356. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed A, Seth S, Purewal J, Wong-Foy AG, Veenstra M, Matzger AJ, et al. Exceptional hydrogen storage achieved by screening nearly half a million metal-organic frameworks. Nat Commun 2019;10:1568. [CrossRef]

- Yang SL, Karve VV, Justin A, Kochetygov I, Espín J, Asgari M, et al. Enhancing MOF performance through the introduction of polymer guests. Coord Chem Rev 2021;427:213525.

- Zhang X, Zhang S, Tang Y, Huang X, Pang H. Recent advances and challenges of metal–organic framework/graphene-based composites. Compos B Eng 2022;230: 109532. [CrossRef]

- Kang PC, Ou YS, Li GL, Chang JK, Wang CY. Room-temperature hydrogen adsorption via spillover in Pt nanoparticle-decorated UiO-66 nanoparticles: implications for hydrogen storage. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2021;4:11269–80. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Zhang X, Cheng X, Xie Z, Kuang Q, Zheng L. The function of metal-organic frameworks in the application of MOF-based composites. Nanoscale Adv 2020;2:2628–47. [CrossRef]

- Ren J, Huang Y, Zhu H, Zhang B, Zhu H, Shen S, et al. Recent progress on MOF-derived carbon materials for energy storage. Carbon Energy 2020;2:176–202. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Yang X, Xue H, Pang H, Xu Q. Metal–organic frameworks as a platform for clean energy applications. Inside Energy 2020;2:100027. [CrossRef]

- Niu S, Wang Z, Zhou T, Yu M, Yu M, Qiu J. A polymetallic metal-organic framework-derived strategy toward synergistically multidoped metal oxide electrodes with ultralong cycle life and high volumetric capacity. Adv Funct Mater 2016;27:1605332. [CrossRef]

- Shi W, Ye C, Xu X, Liu X, Ding M, Liu W, et al. High-performance membrane capacitive deionization based on metal-organic framework-derived hierarchical carbon structures. ACS Omega 2018;3:8506–13. [CrossRef]

- Bao W, Yu J, Chen F, Du H, Zhang W, Yan S, et al. Controllability construction and structural regulation of metal-organic frameworks for hydrogen storage at ambient condition: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chavan S, Vitillo JG, Gianolio D, Zavorotynska O, Civalleri B, Jakobsen S, et al. H 2 storage in isostructural UiO-67 and UiO-66 MOFs. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2012;14:1614–26.

- Xia YD, Yang ZX, Zhu YQ. Porous carbon-based materials for hydrogen storage: advancement and challenges. J Mater Chem A 2013;1:9365–81. [CrossRef]

- Xu H, Shang H, Wang C, Du Y. Low-dimensional metallic nanomaterials for advanced electrocatalysis. Adv Funct Mater 2020;30:2006317. [CrossRef]

- Van der Ven A, Deng Z, Banerjee S, Ong SP. Rechargeable alkali-ion battery materials: theory and computation. Chem Rev 2020;120:6977–7019.

- Wang ZF, Jin KH, Liu F. Computational design of two-dimensional topological materials. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2017;7:e1304. [CrossRef]

- Mroz AM, Posligua V, Tarzia A, Wolpert EH, Jelfs KE. Into the unknown: how computation can help explore uncharted material space. J Am Chem Soc 2022; 144:18730–43. [CrossRef]

- Miracle DB, Li M, Zhang ZH, Mishra R, Flores KM. Emerging capabilities for the high-throughput characterization of structural materials. Annu Rev Mater Res 2021;51(2021):131–64. 51. [CrossRef]

- Xu D, Zhang Q, Huo X, Wang Y, Yang M. Advances in data-assisted high-throughput computations for material design. Materials Genome Engineering Advances 2023;1:e11. [CrossRef]

- Cazorla C. The role of density functional theory methods in the prediction of nanostructured gas-adsorbent materials. Coord Chem Rev 2015;300:142–63. [CrossRef]

- Altintas C, Keskin S. On the shoulders of high-throughput computational screening and machine learning: design and discovery of MOFs for H2 storage and purification. Mater Today Energy 2023;38:101426. [CrossRef]

- Ren E, Guilbaud P, Coudert FX. High-throughput computational screening of nanoporous materials in targeted applications. Digital Discovery 2022;1:355–74.

- Col´on YJ, Fairen-Jimenez D, Wilmer CE, Snurr RQ. High-throughput screening of porous crystalline materials for hydrogen storage capacity near room temperature. J Phys Chem C 2014;118:5383–9.

- Ahmed A, Liu YY, Purewal J, Tran LD, Wong-Foy AG, Veenstra M, et al. Balancing gravimetric and volumetric hydrogen density in MOFs. Energy Environ Sci 2017; 10:2459–71. [CrossRef]

- Deniz CU, Mert H, Baykasoglu C. Li-doped fullerene pillared graphene nanocomposites for enhancing hydrogen storage: a computational study. Comput Mater Sci 2021;186:110023. [CrossRef]

- Bian LY, Li XD, Huang XY, Yang PH, Wang YD, Liu XY, et al. Molecular simulation on hydrogen storage properties of five novel covalent organic frameworks with the higher valency. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2022;47:29390–8. [CrossRef]

- Li QY, Qiu SY, Wu CZ, Lau T, Sun CH, Jia BH. Computational investigation of MgH/graphene heterojunctions for hydrogen storage. J Phys Chem C 2021;125: 2357–63. [CrossRef]

- Rana S, Monder DS, Chatterjee A. Thermodynamic calculations using reverse Monte Carlo: a computational workflow for accelerated construction of phase diagrams for metal hydrides. Comput Mater Sci 2024;233:112727. [CrossRef]

- Jing ZJ, Yuan QQ, Yu Y, Kong XT, Tan KC, Wang JT, et al. Developing ideal metalorganic hydrides for hydrogen storage: from theoretical prediction to rational fabrication. ACS Mater Lett 2021;3:1417–25. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Xu C, Liang J. Dependency distance: a new perspective on syntactic patterns in natural languages. Phys Life Rev 2017;21:171–93. [CrossRef]

- Montejo-R´aez A, Jim´enez-Zafra SM. Current approaches and applications in natural language processing. Appl Sci 2022;12:4859.

- Mahadevkar SV, Khemani B, Patil S, Kotecha K, Vora DR, Abraham A, et al. A review on machine learning styles in computer vision—techniques and future directions. IEEE Access 2022;10:107293–329. [CrossRef]

- Shetty SK, Siddiqa A. Deep learning algorithms and applications in computer vision. Int J Comput Sci Eng 2019;7:195–201. [CrossRef]

- Jovel J, Greiner R. An introduction to machine learning approaches for biomedical research. Front Med 2021;8:771607. [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou K, Daneva GN, Adamopoulos PG, Scorilas A. Artificial intelligence: the milestone in modern biomedical research. BioMedInformatics 2022;2:727–44. [CrossRef]

- Cebollada S, Paya L, Flores M, Peidr´o A, Reinoso O. A state-of-the-art review on mobile robotics tasks using artificial intelligence and visual data. Expert Syst Appl 2021;167:114195.

- Cully A, Clune J, Tarapore D, Mouret JB. Robots that can adapt like animals. Nature 2015;521. 503-U476. [CrossRef]

- Tsai C-W, Lai C-F, Chiang M-C, Yang LT. Data mining for internet of things: a survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2014;16:77–97. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Pan R, Martins ML, Cui J, Huang Z, Thapaliya BP, et al. Machine-learning-assisted material discovery of oxygen-rich highly porous carbon active materials for aqueous supercapacitors. Nat Commun 2023;14:4607.

- Borboudakis G, Stergiannakos T, Frysali M, Klontzas E, Tsamardinos I, Froudakis GE. Chemically intuited, large-scale screening of MOFs by machine learning techniques. npj Comput Mater 2017;3:40.

- Lv C, Zhou X, Zhong L, Yan C, Srinivasan M, Seh ZW, et al. Machine learning: an advanced platform for materials development and state prediction in lithium-ion batteries. Adv Mater 2022;34:e2101474. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Kang D, Kim S, Jang HW. Catalyze materials science with machine learning. ACS Mater Lett 2021;3:1151–71. [CrossRef]

- Shi Z, Yang W, Deng X, Cai C, Yan Y, Liang H, et al. Machine-learning-assisted high-throughput computational screening of high performance metal–organic frameworks. Molecular Systems Design & Engineering 2020;5:725–42. [CrossRef]

- J¨ager MO, Morooka EV, Federici Canova F, Himanen L, Foster AS. Machine learning hydrogen adsorption on nanoclusters through structural descriptors, 4; 2018. p. 37.

- Hattrick-Simpers JR, Choudhary K, Corgnale C. A simple constrained machine learning model for predicting high-pressure-hydrogen-compressor materials. Molecular Systems Design & Engineering 2018;3:509–17.

- Nations S, Nandi T, Ramazani A, Wang SN, Duan YH. Metal hydride composition-derived parameters as machine learning features for material design and H2 storage. J Energy Storage 2023;70:107980. [CrossRef]

- Kim JM, Ha T, Lee J, Lee Y-S, Shim J-H. Prediction of pressure-composition-temperature curves of AB2-type hydrogen storage alloys by machine learning. Met Mater Int 2022;29:861–9. [CrossRef]

- Thanh HV, Taremsari SE, Ranjbar B, Mashhadimoslem H, Rahimi E, Rahimi M, et al. Hydrogen storage on porous carbon adsorbents: rediscovery by nature-derived algorithms in random forest machine learning model. Energies 2023;16: 2348. [CrossRef]

- Shekhar S, Chowdhury C. Prediction of hydrogen storage in metal-organic frameworks: a neural network based approach. Results in Surfaces and Interfaces 2024;14:100166. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed A, Siegel DJ. Predicting hydrogen storage in MOFs via machine learning. Patterns (N Y) 2021;2:100291. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).