1. Introduction to Centrioles and Centrosomes

The Centrioles and centrosomes are key components of cellular architecture, essential for the organisation of the microtubule cytoskeleton, accurate cell division, and the formation of cilia and flagella [

1]. The centrosome, often referred to as the major microtubule organising centre (MTOC) in animal cells, consists of a pair of centrioles surrounded by an amorphous matrix of proteins called the pericentriolar material [PCM). Together, these structures coordinate the spatial organisation of microtubules during interphase and direct the formation of the bipolar mitotic spindle during cell division, which is essential for proper chromosome segregation and genomic stability [

2]. Because of their central role in maintaining cellular homeostasis, centrioles and centrosomes are tightly regulated; defects in their function or duplication can contribute to diseases such as cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders [

3,

4,

5].

1.1. Structure of Centrioles

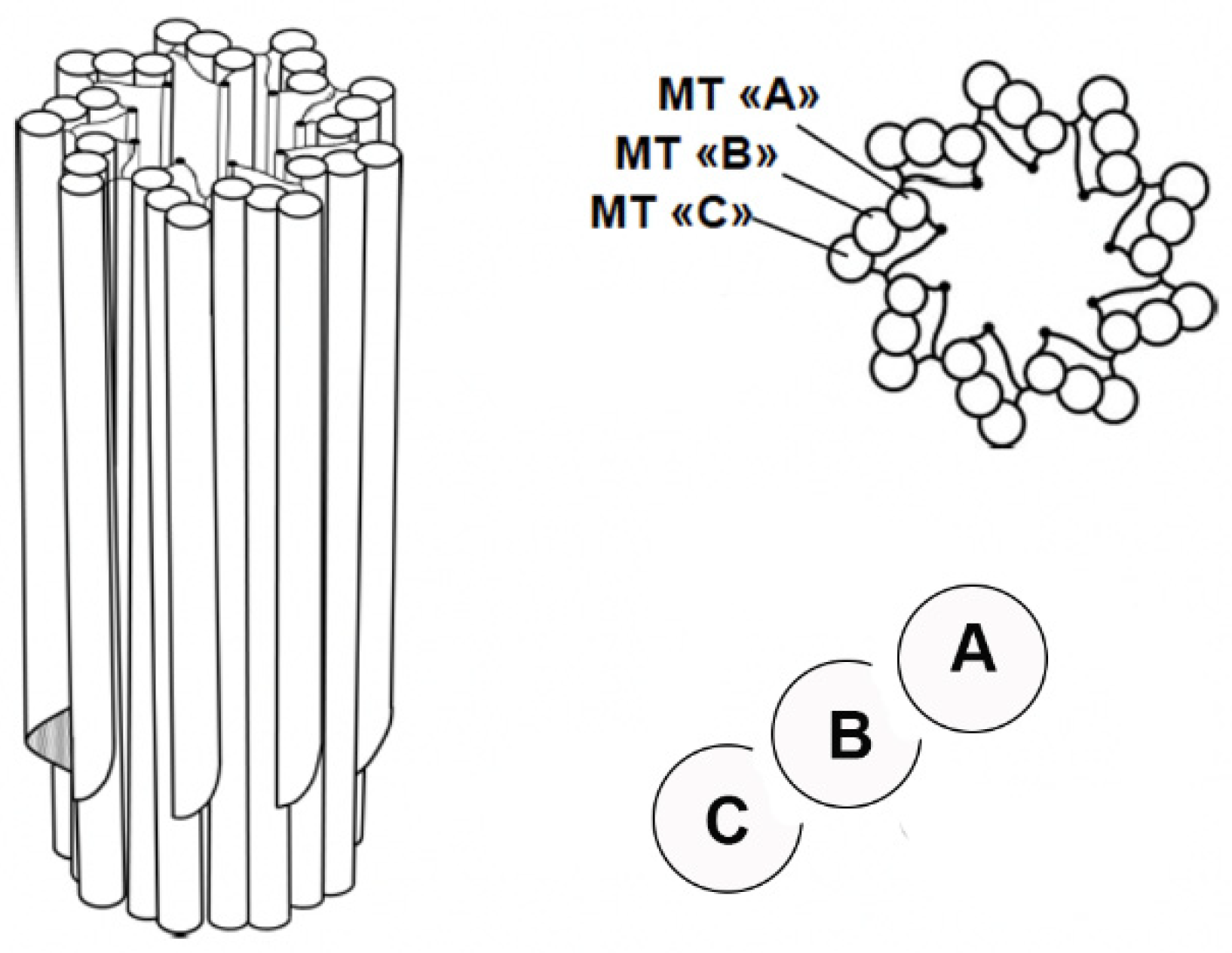

Centrioles are barrel-shaped organelles composed of microtubule triplets arranged in a characteristic 9-fold radial symmetry. Advances in electron microscopy have provided detailed insights into the ultrastructure of centrioles, revealing their 9-fold symmetry and microtubule triplet arrangement [

6]. Each triplet consists of one complete microtubule (A-tubule) and two incomplete microtubules (B- and C-tubules) [

7] (

Figure 1). Centrioles are approximately 200 nm in diameter and 500 nm in length; despite their small size, they serve as platforms for the recruitment of proteins required for microtubule nucleation and anchoring, making them indispensable for various cellular processes [

8].

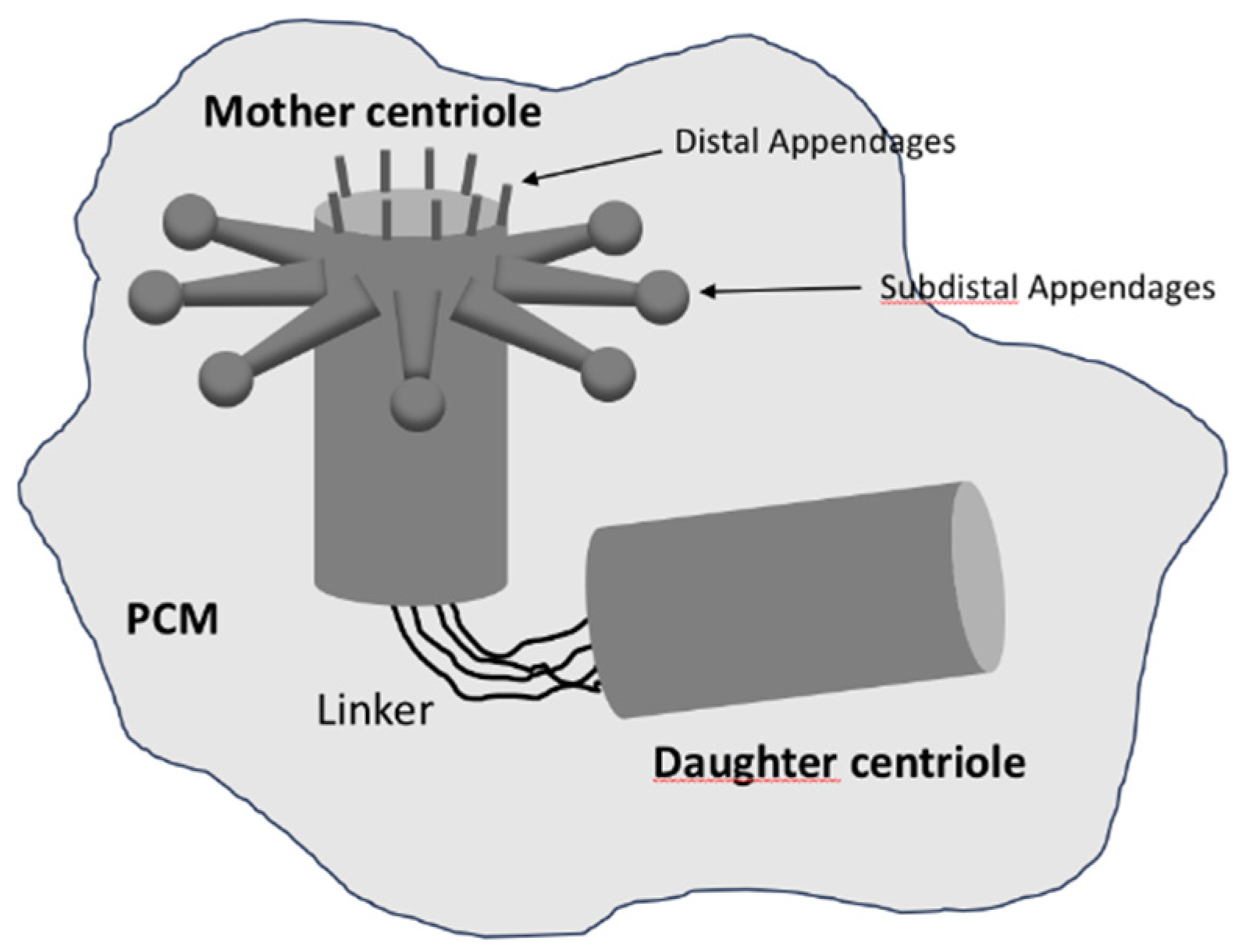

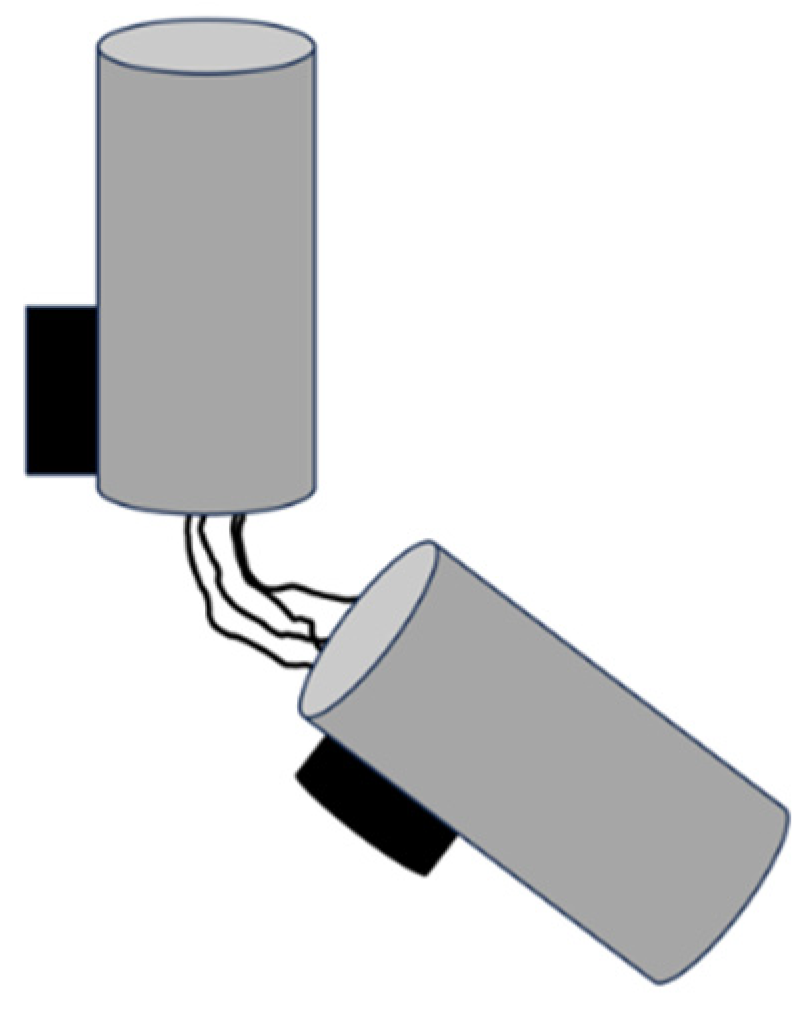

In most animal cells, centrioles are found in pairs, connected by links that form the ’linker’; they are oriented orthogonally to each other, with one called the ’mother’ centriole and the other the ’daughter’ centriole [

9]. The mother centriole is typically older and more structurally mature than the daughter centriole, with appendages at its distal end that are involved in anchoring and organising microtubules (

Figure 2). These appendages are essential for the formation of basal bodies from which cilia and flagella extend [

10]. In contrast, the daughter centriole lacks these appendages and must mature before acquiring full functionality.

1.2. The Centrosome and Its Function

The centrosome is a dynamic organelle that is critical for the spatial organisation of the microtubule network in the cell. In most animal cells, it serves as the primary microtubule-organising centre [

2] and plays an essential role in many processes.

Centrosomes nucleate and anchor microtubules, ensuring that the cell maintains a polarised microtubule array. This organisation is critical for processes such as intracellular transport, cell shape maintenance and migration [

11].

During cell division, centrosomes duplicate during interphase and migrate around the nucleus to opposite poles of the cell during prophase of mitosis to form the mitotic spindle. The spindle apparatus orchestrates the precise segregation of chromosomes into daughter cells, ensuring that each newly formed cell inherits genetic material identical to that of the parent cell. Errors in centrosome function or duplication can therefore lead to aberrant spindle formation, resulting in chromosomal instability and aneuploidy—hallmarks of many cancers [

12,

13].

Centrioles are also critical for the formation of cilia and flagella. During this process, the mother centriole docks to the plasma membrane and becomes a basal body that initiates cilia formation [

14]. Cilia and flagella are essential for several functions, including cell motility and fluid movement across epithelial surfaces. This may be the primary function of centrioles, as Drosophila without centrioles reach adulthood, meaning that cells can divide without centrioles, but the flies die because they have no cilia or flagella [

15].

1.3. Centriole Duplication: A Brief Overview

Centriole duplication is a highly regulated process that ensures that the correct number of centrioles are maintained in each cell. Under normal conditions, a non-dividing cell contains two centrioles (one centrosome). In proliferating cells, these centrioles must duplicate once and only once per cell cycle so that the cell contains two centrosomes to form a bipolar spindle when it enters mitosis. The bipolarity of the spindle is essential to segregate the duplicated chromosomes into two sets. When the cell divides, each daughter cell inherits one set of chromosomes and one centrosome [

16].

The centriole duplication process can be considered semi-conservative, which does not mean that a new centriole is copied from an existing centriole, but rather that each new procentriole is formed on the surface of each existing centriole (

Figure 3). Duplication begins late in G1, just before the G1-S phase transition, with new procentrioles forming orthogonally to each parent centriole, resulting in cells with four centrioles (two centrosomes). The duplication process continues during G2, with centriole elongation and maturation [

17]. As the cell enters mitosis, the two older centrioles that formed the original centrosome separate, each remaining attached to a new centriole. These two pairs of centrioles then become the centrosomes that organise the poles of the bipolar spindle during mitosis.

1.4. The Importance of Centriole Number and Integrity

Proper centriole duplication is critical for cellular homeostasis and organismal development. Errors in centriole duplication can lead to centrosome amplification (more than two centrosomes per cell), which is often observed in cancer cells. Centrosome amplification can affect the assembly of the bipolar mitotic spindle, leading to multipolar spindles and chromosome mis-segregation, contributing to chromosomal instability [

18]. Conversely, insufficient centriole duplication can impair the formation of a bipolar spindle, leading to monopolar spindle assembly, abnormal cell division and aneuploidy [

19].

Defects in centriole function or duplication have also been linked to a wide range of developmental disorders. For example, mutations in genes that regulate centriole duplication are associated with primary microcephaly, a condition characterised by reduced brain size due to defects in neural progenitor cell division [

20]. Polyploidisation of liver cells, which occurs in the absence of centrioles, leads to severe liver damage that affects liver function [

21].

1.5. Historical Perspective and Discovery of Centrioles

The discovery of centrioles dates back to the late 19th century, when they were first observed under the microscope by the Swiss anatomist Theodor Boveri [

22,

23] (

Figure 4). Boveri made significant contributions to the understanding of the role of centrosomes in cell division, proposing that centrosomes are crucial for the proper segregation of chromosomes [

3].

The molecular mechanisms underlying centriole duplication and centrosome function remained elusive until recent studies using advanced molecular biology techniques. The identification of key regulators such as PLK4 (polo-like kinase 4), SAS-6 (spindle assembly abnormal protein 6) and STIL (SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus), together with the use of model organisms such as Drosophila, zebrafish and mouse models, has expanded our understanding of how centrioles duplicate and how dysregulation of this process contributes to disease [

24,

25,

26].

1.6. Relevance of Centriole Research in Disease and Therapeutics

Research into centrioles and centrosomes has broad implications for human health. Centrosome abnormalities are a hallmark of most cancer cells, and the dysregulation of centriole duplication has been implicated in tumorigenesis due to its role in chromosomal instability. Centrosome amplification, driven by overduplication of centrioles, has been observed in various solid tumors, and its contribution to cancer progression is a subject of intense investigation [

5,

27].

Additionally, defects in centriole duplication are linked to several genetic disorders, including primary microcephaly and ciliopathies, diseases caused by defective cilia formation [

28]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing centriole duplication can inform therapeutic strategies for treating these conditions. For example, inhibitors targeting PLK4, a key regulator of centriole duplication, are being explored as potential cancer treatments aimed at reducing centrosome amplification in tumours [

29,

30].

Summary

Centrioles and centrosomes are essential cellular membrane less organelles that play a critical role in microtubule organisation, cell division and ciliogenesis. Centriole duplication is tightly regulated in concert with DNA replication, two processes that ensure genomic stability during cell division. Dysregulation of centriole duplication can have severe consequences, including cancer and developmental disorders. As research in this field advances, a deeper understanding of centriole biology promises to provide insights into the molecular basis of various diseases and open up new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

2. Overview of the Centriole Duplication Process

Centriole duplication is a highly orchestrated, cell cycle-dependent process that ensures that the correct number of centrioles is maintained in a cell. A typical cell contains one pair of centrioles, and as the cell cycle progresses, centriole duplication begins by building a new pro-centriole on the wall of each existing centriole. This process is tightly regulated to occur only once per cell cycle, ensuring that the cell enters mitosis with two centrosomes [

31,

32]. Here, we explore the key stages of centriole duplication, the key molecular players involved, and the regulatory mechanisms that prevent duplication errors.

2.1. The Centriole Duplication Cycle

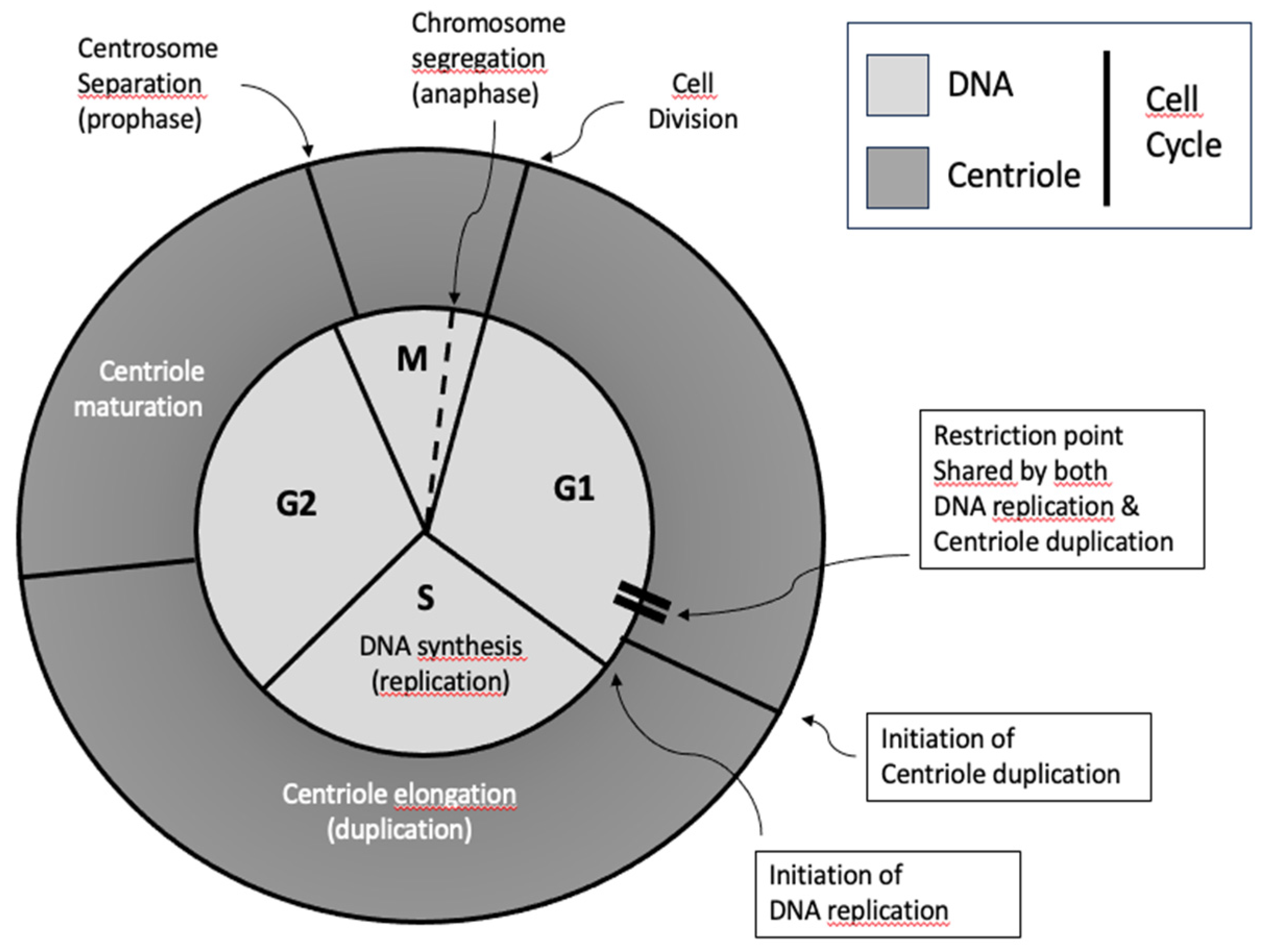

Centriole duplication occurs in synchrony with DNA replication during cell cycle, beginning in the late G1 or early S phase and continuing through the G2 phase (

Figure 5). Centriole duplication occurs independently of DNA synthesis but both events are coordinated [

33,

34,

35,

36]. This ensures that before cell division the cell contains two copies of its genome and precisely two centrosomes at the onset of mitosis, with each centrosome composed of a pair of centrioles. After cell division each daughter cell will then get one centrosome and one copy of the genome.

Key Phases of Centriole Duplication:

Initiation (late G1/early S Phase): A new procentriole begins to form adjacent to each pre-existing mother centriole [

37].

Elongation (S and G2 Phases): The procentriole grows by adding tubulin subunits to its microtubule structure [

38,

39].

Maturation (Late G2 and M Phases): Daughter centrioles mature, acquiring full structural and functional capacity [

9,

40].

Separation (Mitosis): The mother and daughter centrioles separate, and each pair moves to opposite poles of the cell during mitosis [

41,

42].

2.2. Key Stages of Centriole Duplication

2.2.1. Initiation: Formation of the Procentriole

The first step in centriole duplication is the initiation of procentriole formation, which occurs adjacent to the pre-existing mother centriole [

37] (

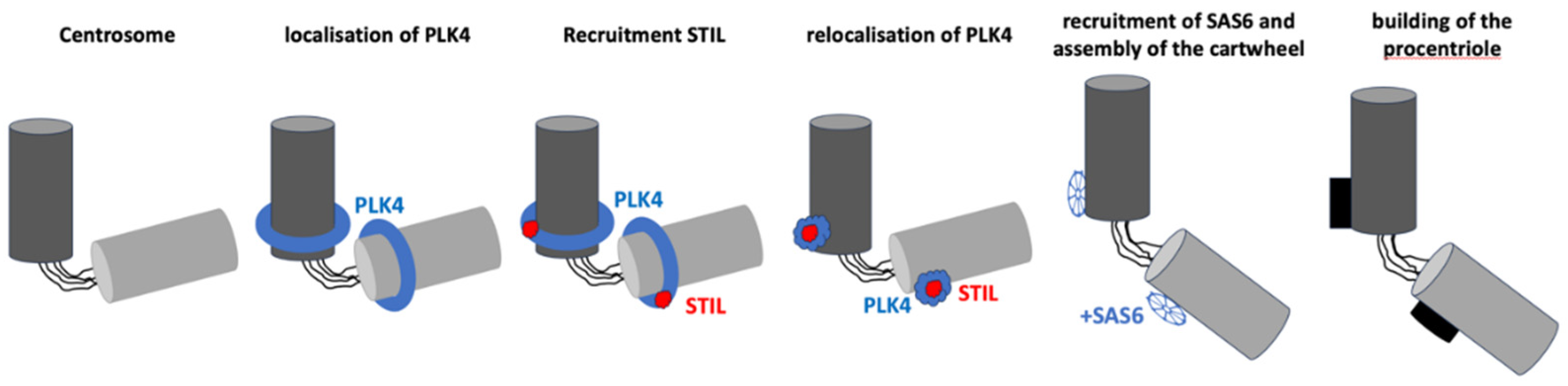

Figure 6). This process begins in the late G1 phase or early S phase of the cell cycle, triggered by the recruitment of several key proteins:

PLK4: PLK4 is a master regulator that localizes to the surface of the mother centriole, forming a scaffold to recruit other essential proteins, including STIL and SAS-6. PLK4 phosphorylation of these proteins is critical for procentriole formation [

43,

44].

STIL: STIL interacts with PLK4 and is necessary for recruiting SAS-6, establishing the structural symmetry of the centriole [

45].

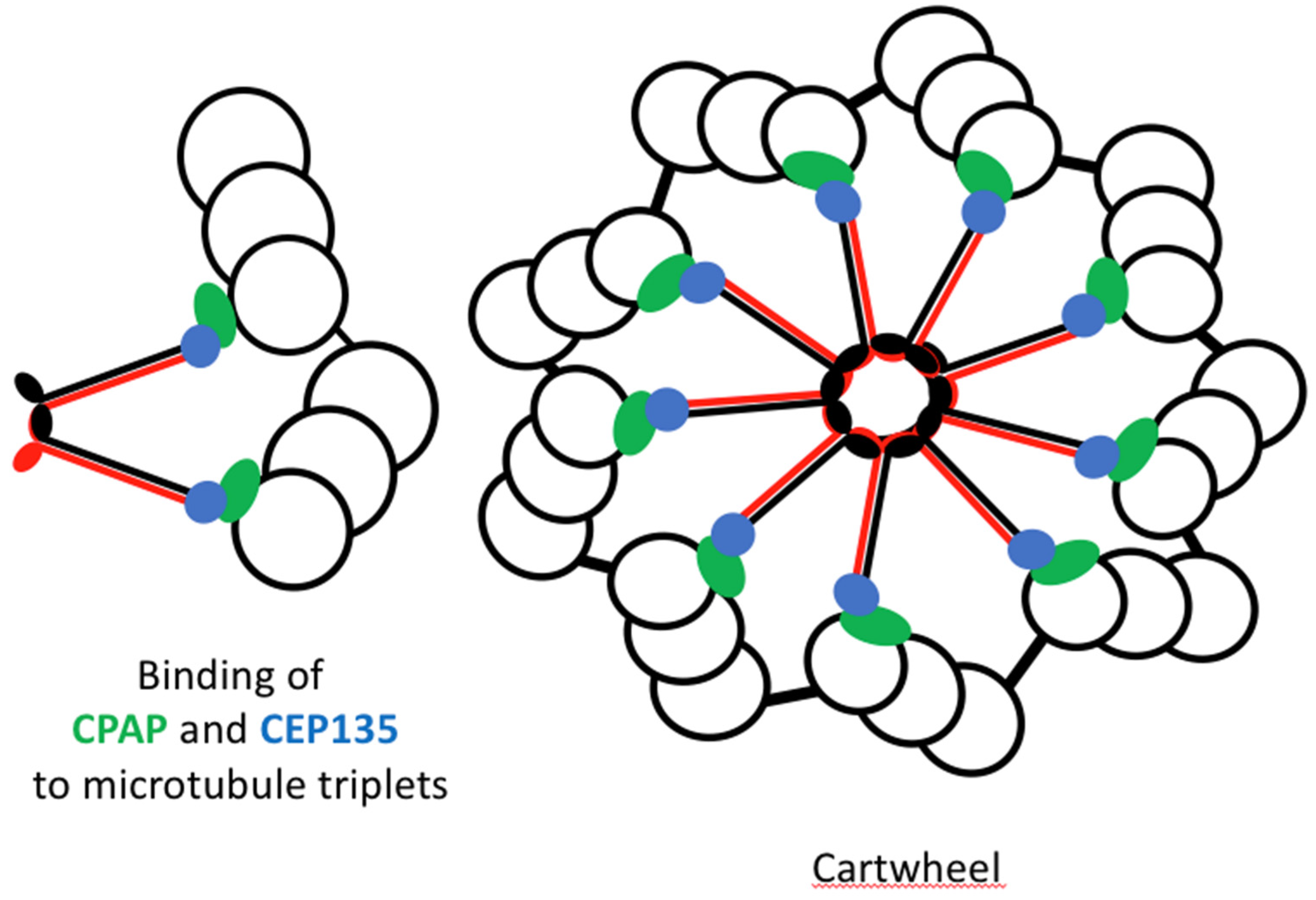

SAS-6: SAS-6 forms the cartwheel structure, establishing the 9-fold radial symmetry of the centriole, which is essential for its assembly [

46].

CEP152 and

CEP192 (Centrosomal Protein 152 and 192): These centrosomal proteins act as scaffolds to recruit PLK4 and other proteins, ensuring that the duplication process is spatially restricted to the site adjacent to the mother centriole [

47,

48].

Once these proteins are recruited and the cartwheel structure forms, microtubule assembly begins, marking the transition to the elongation phase of centriole duplication.

2.2.2. Elongation: Growth of the Procentriole

After initiation, the procentriole elongates by incorporating tubulin subunits into the growing microtubule triplets, driven by proteins that regulate tubulin polymerization:

CPAP (Centrosomal P4.1-associated protein): CPAP promotes the addition of tubulin to the growing microtubules and regulates centriole length by controlling microtubule polymerization [

49].

CEP135 (Centrosomal Protein 135): This protein stabilizes the microtubule triplets that make up the centriole, ensuring the proper structural integrity during elongation [

50].

Elongation continues through the G2 phase of the cell cycle, ensuring that the daughter centriole reaches a length comparable to that of the mother centriole before entering mitosis.

2.2.3. Maturation: Preparation for Function

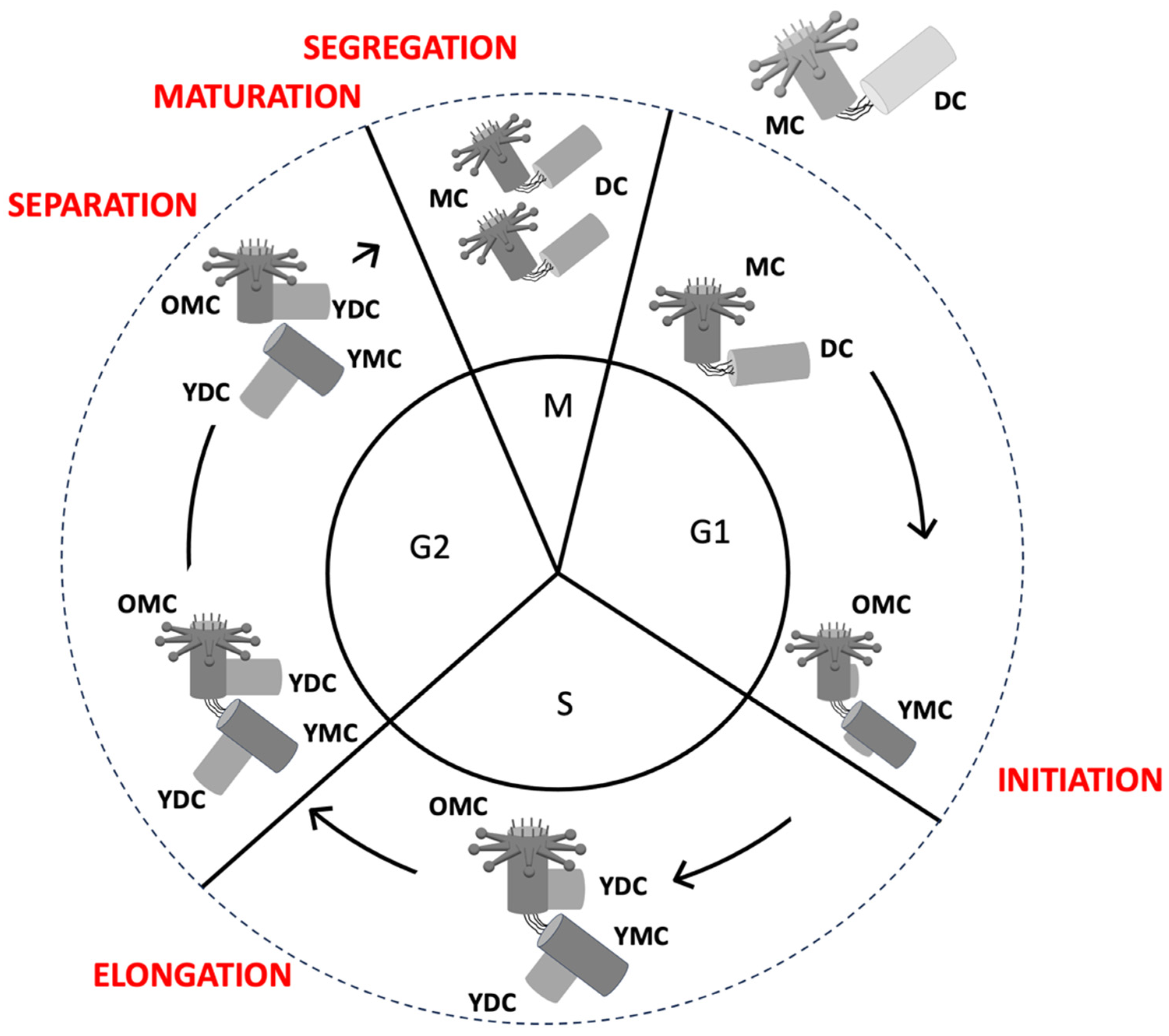

After elongation, each centrosome has two centrioles, one with a mother and daughter centriole and one with two daughter centrioles (

Figure 7). The oldest daughter of the last one then undergoes a maturation process to become a mother centriole, which is crucial to become fully competent to perform all its functions, such as organising pericentriolar material (PCM), which is essential for microtubule nucleation [

51] and acting as a basal body for ciliogenesis. [

52].

How to distinct the Mother from the Daughter Centriole? The mother centriole is structurally distinct and possesses appendages [

53].

What is the pericentriolar material (PCM)? The PCM is a dynamic matrix of proteins surrounding the centrosome, the composition of which changes during the cell cycle. Among the proteins recruited by the centrosome are those involved in microtubule nucleation. For example, in mitosis, when microtubule nucleation is at its peak, the level of proteins involved in MT nucleation is very high in the PCM. [

54].

Maturation of the centrosome’s oldest daughter centriole is mandatory since it prepares the centrosome for subsequent cycles. At the end of mitosis, each daughter cell inherits an active centrosome (a mother centriole and a daughter centriole) ready to organize a PCM and undergo a new cycle of duplication.

2.2.4. Separation: Distribution to Daughter Cells

When the cell enters mitosis, the duplicated centrosomes, each containing a pair of centrioles, separate and move around the nucleus towards opposite poles. This event that depends on microtubules and actin is a prerequisite for the assembly of the bipolar spindle [

55]. When the nuclear envelope breaks, the centrosomes form the poles of the bipolar spindle and organise microtubules that will separate the chromosomes into two identical sets. The presence of two centrosomes in a mitotic cell is essential for the formation of a bipolar spindle (two centrosome for two poles). The two daughter cells must inherit an identical set of chromosomes and a centrosome during the physical division of the two daughter cells, maintaining genomic stability [

56]. Each centrosome consists of a mother centriole and a daughter centriole. During interphase, the mother and daughter centrioles are ’engaged’, held together by cohesion proteins. This engagement does not allow centriole duplication to begin. It is only during the progression of mitosis that these bonds are broken, meaning that the centrioles inherited by the daughter cells are ’disengaged’. This disengagement does not last very long and is only necessary to allow a new cycle of centriole duplication during the next cell cycle [

17,

57].

2.3. Mechanisms Preventing Overduplicatio

A key challenge in centriole duplication is to ensure that each centriole duplicates exactly once and only once per cell cycle. This is achieved by several regulatory mechanisms [

17]. PLK4, which is key to the initiation of centriole duplication, is targeted by ubiquitin ligases for proteasomal degradation after duplication initiation to prevent overactivation and re-duplication [

58]. Proteins such as STIL and SAS-6 are also tightly regulated to prevent aberrant centriole formation and ensure proper centriole duplication [

59]. As described above, when centriole duplication begins, the centrioles become “engaged” meaning “locked”, preventing the initiation of a new duplication. Once duplication is complete, the centrioles are “disengaged” or “unlocked” only during the subsequent mitosis. This disengagement “licenses” the mother and daughter centrioles for a new round of duplication in the next cell cycle [

17]. The semantics are taken from the DNA replication mechanism [

60] (

Figure 7).

Conclusion

Centriole duplication begins with the initiation of procentriole formation, followed by elongation, maturation, and separation. Key regulatory proteins ensure that duplication occurs precisely once per cell cycle, preventing centrosome amplification and maintaining genomic integrity. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for elucidating how errors in centriole duplication contribute to diseases such as cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders.

3. Key Molecular Players in Centriole Duplication

This section looks in more detail at the key molecules involved in centriole duplication, focusing on Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), SAS-6, STIL, CPAP, CEP135 and other helper proteins such as CEP192 and CEP152 that regulate this essential process.

3.1. PLK4

Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) is a member of the polo-like family of serine/threonine kinases that have 5 members. They are all characterised by a N-term catalytic domain at least one polo-box domain at its C-term end. Every PLK play a role in the control of cell cycle progression excepted PLK5 [

61]. (PLK4) is widely recognised as the master regulator of centriole duplication. PLK4 is a serine/threonine kinase that localises to the centrioles where it initiates centriole duplication at the end of G1 phase of the cell cycle. One of the key functions of PLK4 is to phosphorylate specific target proteins such as STIL and SAS-6, both of which are critical for the formation of the nascent centriole. [

37,

59]. In the early stages of centriole duplication, PLK4 phosphorylates STIL, which is necessary for STIL to interact with SAS-6. This interaction is crucial as it initiates the formation of the centriole cartwheel structure, a scaffold required for the assembly of the core components of the centriole [

62]. Phosphorylation by PLK4 also drives the assembly of a ring-like structure at the base of the mother centriole, where daughter centrioles are formed [

63]. By phosphorylating SAS-6, PLK4 ensures the precise organisation of the 9-fold symmetry of the centriole, a hallmark of centriole structural integrity [

64]. Since PLK4 initiates duplication, you do not want too much of its activity. Indeed, PLK4 activity is tightly regulated to prevent centriole overduplication, which can lead to multipolar spindles and aneuploidy, both hallmarks of cancer cells. PLK4 is primarily regulated by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, through several ubiquitin ligases such as βTrCP/Slimb [

65], Mib1 [

66] and CRL4DCAF1 [

67]. Trans-autophosphorylation of PLK4 is a prerequisite for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome [

68,

69]. Temporal control of PLK4 levels is critical. High levels of PLK4 lead to centriole amplification, whereas low levels prevent centriole duplication [

32,

70]. Autophosphorylation of PLK4 can also promote its own degradation, creating a negative feedback loop that controls centriole number [

69]. Tight regulation of PLK4 ensures that centriole duplication occurs once per cell cycle, preventing abnormalities in centrosome number that are associated with chromosomal instability and cancer [

8,

32].

3.2. STIL

STIL is a multi-domain protein that contains structured domains (coiled-coil domains and alpha helixes) but also many intrinsically disordered regions (IRD). STIL function depends on its tetramerization [

71]. STIL plays a critical role in centriole duplication. STIL is recruited to the centrioles during the G1 phase of the cell cycle, where it is phosphorylated by PLK4 [

72]. This phosphorylation allows STIL to interact with SAS-6, facilitating the assembly of the cartwheel structure required for daughter centriole formation [

73]. STIL acts as a bridge between PLK4 and SAS-6, ensuring that centriole duplication occurs in a tightly regulated manner. Its role in stabilising the cartwheel structure throughout centriole elongation ensures that the developing centriole maintains its integrity during maturation [

59].

3.3. SAS-6

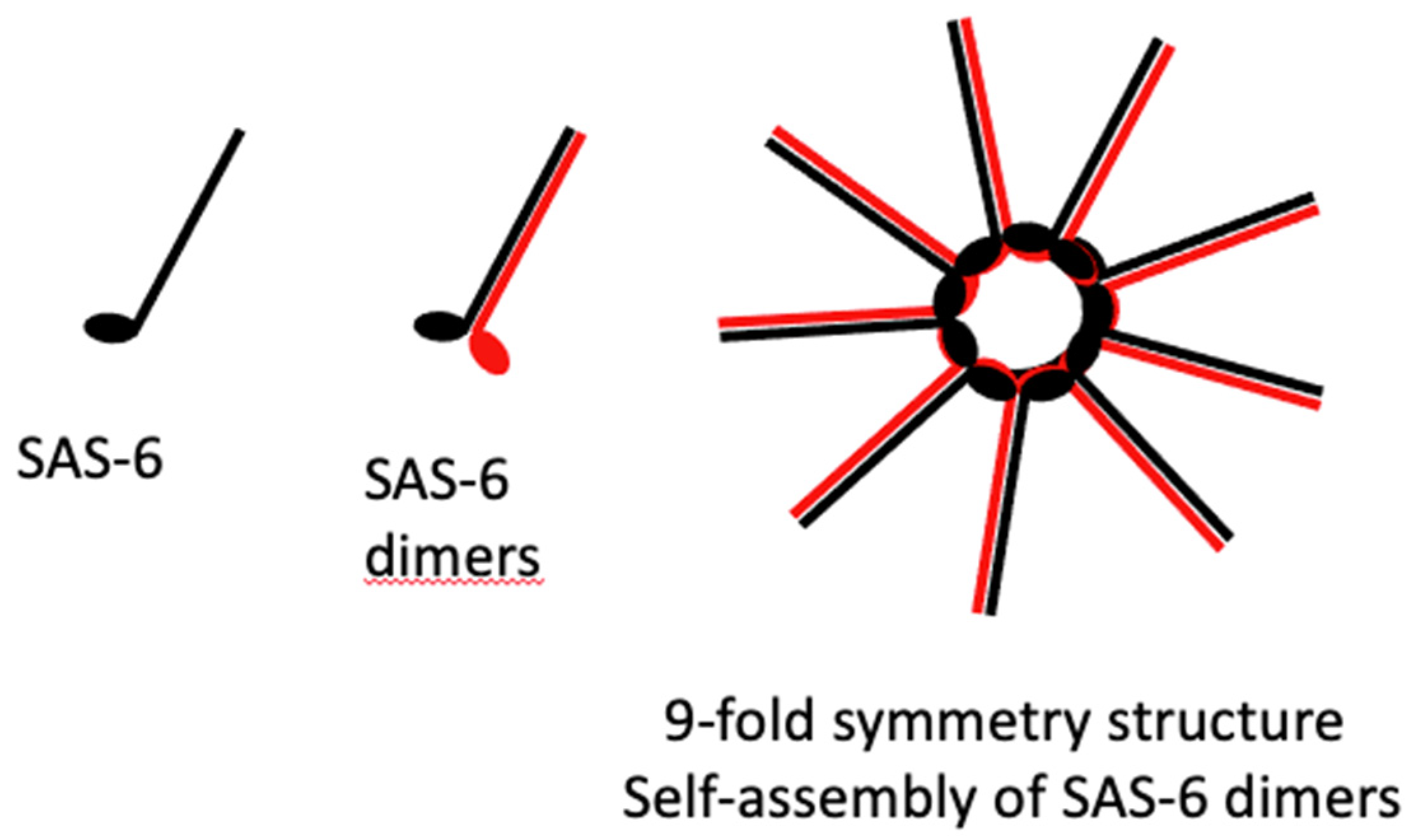

SAS-6 is a coiled-coil protein that can self-assemble in vitro into the 9-fold symmetric structure found at the centre of the cartwheel [

74] (

Figure 8). SAS-6 is thus a core structural protein pivotal in the formation of the cartwheel. The cartwheel structure consists of a central hub surrounded by spokes formed by SAS-6 [

75]. SAS-6 forms the hub of the cartwheel.

This arrangement is crucial for establishing the nine-fold symmetry characteristic of centrioles. The cartwheel serves as a model for directing the subsequent addition of the triplets of microtubules that enable the centriole to develop. It serves as a scaffold for the assembly of the centriole. [

6,

76,

77]. The cartwheel establishes the fundamental symmetry of the centriole, which is essential for its role as a microtubule organisation centre (MTOC) [

77,

78]. The interaction between SAS-6 and STIL, regulated by PLK4 phosphorylation, is essential for centriole duplication (73]. Thus, SAS-6 plays a crucial role in initiating centriole duplication and in maintaining centriole structure (9-fold symmetry) [

79].

3.4. CPAP

CPAP discovered in 2000, is a centriolar protein that binds to γ-tubulin [

80]. It also corresponds to the centromeric protein CENP-J [

81]. CPAP regulates centriole elongation by promoting microtubule polymerization. After the cartwheel structure forms, CPAP is recruited to the growing centriole, where it facilitates the addition of tubulin subunits to the microtubules [

49]. CPAP binds tubulin dimers, stabilizing them and enabling their incorporation into the growing centriole’s microtubule triplets [

82]. The regulation of CPAP is crucial, as abnormalities in centriole length can impair spindle formation, potentially contributing to tumorigenesis. Overexpression of CPAP leads to overly elongated centrioles, while depletion results in shorter centrioles that may be dysfunctional [

49].

3.5. CEP135

CEP135 (Centrosomal Protein 135) acts as a scaffold protein to build a centriole. It stabilizes the microtubule triplets that form the outer structure of the centriole and links the inner cartwheel, formed by SAS-6, to the microtubule triplets [

83]. CEP135 stabilizes the centriole during elongation and maturation, interacting with both microtubules and other centriolar proteins to ensure structural stability [

50]. Mutations in CEP135 have been associated with defects in centriole structure, leading to abnormal cell division and developmental disorders [

84,

85]. CEP135 is essential for centrosome function and accurate cell division.

Figure 9.

Cartwheel assembly with its 9 triplets of microtubules. SAS-6 dimers in Red and Black, CPAP in green and CEP35 in blue.

Figure 9.

Cartwheel assembly with its 9 triplets of microtubules. SAS-6 dimers in Red and Black, CPAP in green and CEP35 in blue.

3.6. Other Proteins Involved in Centriole Biogenesis and Maintenance

Additional proteins, including CEP192 and CEP152 (Centrosomal Protein 192 and 152), are essential for PLK4 recruitment during the initial stages of centriole duplication. CEP192 acts as a scaffold for PLK4, while CEP152 ensures its correct localization and activation [

47,

86]. These two proteins are essential for centriole maturation and hence cell division. Mutations in these proteins are linked to centrosome dysfunction and diseases such as microcephaly [

87]. Auxiliary proteins like CEP295 and CEP63 (Centrosomal Protein 295 and 63) also contribute to centriole duplication by regulating cohesion, recruitment of structural proteins, and centriole length and stability [

88,

89].

4. Regulation of Centriole Duplication

The regulation of centriole duplication involves various mechanisms, including licensing and temporal control, ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, negative regulation by tumour suppressors like p53 and p21, and mechanisms that prevent re-duplication. This section explores these regulatory pathways in detail.

4.1. Licensing and Temporal Control

Centriole duplication must occur at the right time during cell cycle progression and precisely once and only once per cell cycle. This regulation involves multiple checkpoints and regulatory proteins that ensure centriole duplication is tightly coordinated with the phases of the cell cycle.

4.1.1. Licensing Mechanisms

The G1/S transition marks the critical point at which cells are licensed to duplicate their centrioles. This timing is vital because centriole duplication must coincide with DNA replication, ensuring that the new centrioles are made before the subsequent cell division. Cyclin-dependent kinases, particularly CDK2, play a pivotal role in initiating centriole duplication. During the G1 phase, cyclin E associates with CDK2, facilitating the phosphorylation of key proteins involved in DNA replication [

90,

91,

92]. These phosphorylations are essential for the recruitment of regulatory proteins to the centrosome. During S-phase entry, the presence of cyclin E-CDK2 complexes promotes the assembly of new centrioles adjacent to pre-existing mother centrioles. [

93,

94].

4.1.2. Preventing Overduplication

Like DNA, the centrosome must be duplicated once and only once per cell cycle, how is this achieved?

Firstly, it is achieved by controlling the expression of key proteins such as STIL and SAS-6, which are crucial for centriole assembly and whose expression levels are therefore tightly regulated to prevent excessive centriole formation. Indeed, for example, overexpression of STIL leads to supernumerary centrioles [

45] just like overexpression of SAS6 [

95,

96,

97].

Secondly, feedback loops monitor the integrity of centriole duplication. For example, the activity of CDKs is regulated by cyclin degradation at the end of mitosis, preventing premature initiation of duplication in the subsequent cell cycle. This ensures that centriole duplication occurs only once, maintaining cellular integrity [

32].

4.1.3. Checkpoints in Centriole Duplication

The G2/M checkpoint plays a crucial role in ensuring that the cell is ready to enter mitosis. For instance, if centriole duplication is incomplete or if there are any issues with DNA replication, the cell cycle progression is either slowed down or halted, allowing time for necessary repairs [

98]. The regulation of centriole duplication is linked to other cell cycle regulatory pathways. One example is the activity of the retinoblastoma protein (pRb), a tumour suppressor that affects the G1/S transition. Hypophosphorylated pRB inhibits S phase entry, whereas hyperphosphorylation by G1 cyclin/CDK complexes triggers S phase entry [

99,

100]. Treatment of pRB-deficient cells (weak G1/S checkpoint) with hydroxurea results in centrosome amplification [

101].

4.2. Ubiquitination and Proteasomal Degradation

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that regulates various cellular processes by targeting proteins to be degraded. It is, for instance, involved in preventing centrosome overduplication. Indeed, the kinase activity of PLK4 is directly involved in the control of centrosome numbers [

44]. Excessive PLK4 activity results in centriole overduplication, which can disrupt normal centrosome function and contribute to genomic instability, a hallmark of cancer [

32]. PLK4 is considered to be the master regulator of centriole duplication and its levels must then be tightly controlled. One of the primary mechanisms for this control is the degradation of proteins by an ubiquitination dependent pathway. PLK4 is a suicide kinase, when it is autophosphorylated, PLK4 becomes a substrate for SCF-βTrCP ligase, leading to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome [

69]. But SCF-βTrCP is not the only ubiquitin ligase involved in PLK4 degradation. Recently, CRL4

DCAF1 was also identified as a ubiquitin ligase that targets PLK4, but this time, independently of its kinase activity. CRL4

DCAF1 was reported to control of centrosome numbers [

67]. The control of PLK4 degradation by itself creates a self-regulating feedback loop. When centriole duplication is initiated, the increased levels of PLK4 lead to its own degradation, thus preventing the risk of further rounds of duplication. The understanding of PLK4 regulation through ubiquitination has important implications for cancer therapy. Targeting PLK4 for treating cancers has proven to be efficient [

102,

103], targeting the pathways that regulate PLK4 may provide new strategies for treating cancers characterized by centrosome amplification.

4.3. Negative Regulation by p53 and p21

The tumour suppressor protein p53 is a critical player in the cellular response to stress and DNA damage. It exerts negative regulation on cell cycle progression to maintain genomic integrity. P53 is activated in response to DNA damage and functions to arrest cell cycle progression, it acts either in G1 to avoid entry in S or in G2 to avoid entry in M in the presence of lesions in the DNA. One of the functions of p53 is to activate the expression of the p21 protein, which is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor [

104]. It binds directly to cyclin-CDK complexes which in the case of CDK2 delays the G1/S transition. This inhibition prevents the initiation of DNA replication but also centriole duplication, allowing time for the repair of damaged DNA before the cell commits to S phase.

During stress response p53 has also been reported to downregulate PKL4 expression preventing centrosome amplification [

105]. Loss of p53 in another hand leads to centrosome hyperamplification [

106]. P53 also prevents genome instability by arresting cell growth in the presence of centriole duplication defects induced by the absence of PKL4 for instance [

107]. These regulations are crucial for maintaining proper centriole numbers in response to cellular stress. And the regulatory roles of p53 and p21 are critical in tumour suppression. Mutations in p53 are among the most common alterations in cancer, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation and potential centrosome abnormalities [

108]. Understanding the interactions between p53, p21, and centriole duplication can provide valuable insights for developing therapeutic strategies aimed at get rid of cells with amplified centrosomes [

109].

4.4. Centriole Re-Duplication Block

Once centriole duplication is initiated, mechanisms are in place to prevent re-duplication until the next cell cycle begins [

110]. During interphase, cohesion proteins link the mother and daughter centrioles, preventing premature separation and re-duplication. This connection is essential for ensuring that centrioles do not duplicate until the cell is ready for another cycle [

17,

111]. The timing of centriole re-duplication is also tightly regulated. Once centrioles have been duplicated, specific signals prevent any further initiation of duplication until the cell has completed mitosis and returned to interphase [

98]. Following centriole duplication, the activity of PLK4 decreases due to ubiquitination and degradation. This reduction in PLK4 levels effectively silences its activity until the next cell cycle, ensuring that centrioles are not re-duplicated prematurely [

69]. The maturation process of centrioles that is under the control of PLK1 is also critical in controling re-duplication [

112]. During mitosis, the centrosomes, each containing a pair of centrioles, serve as the poles of the mitotic spindle. Proper separation and function of centrioles are essential for the accurate organization of the spindle apparatus, ensuring the correct distribution of chromosomes to daughter cells [

32]. The coordination of centriole duplication and separation with mitotic events underscores the complexity of cellular regulation. Disruptions in this coordination can lead to mitotic errors and contribute to aneuploidy, a common feature of cancer [

98].

The regulation of centriole duplication is a multifaceted process involving licensing mechanisms, ubiquitination pathways, negative regulatory proteins, and systems to block re-duplication. Understanding these regulatory pathways is crucial for elucidating how dysregulation of centriole duplication contributes to various diseases, particularly cancer, and can inform the development of targeted therapies aimed at restoring proper cellular function.

5. Aberrant Centriole Duplication and Its Consequences

Centriole duplication is a tightly regulated process crucial for maintaining cellular integrity and function. However, dysregulation can lead to significant abnormalities, including centrosome amplification. This section explores the mechanisms underlying aberrant centriole duplication, its consequences, and the impact on human health, particularly focusing on cancer and developmental disorders.

5.1. Centrosome Amplification

Centrosome amplification, characterized by the presence of more than two centrosomes, is a common feature of many cancer cells and is associated with various cellular abnormalities.

5.1.1. Dysregulation of Centriole Duplication Proteins

PLK4, the master regulator of centriole duplication, is critical for initiating the duplication process. Dysregulation of PLK4, such as overexpression or hyperactivation, can lead to excessive centriole formation. Studies have demonstrated that increased PLK4 levels can promote centriole overduplication, resulting in centrosome amplification [

113]. This condition is often observed in various cancers, where the cancer cells exhibit aberrant centrosome numbers. SAS-6 is another essential protein in centriole assembly, contributing to the formation of the cartwheel structure. Elevated levels of SAS-6 can also promote the assembly of additional centrioles, leading to the development of supernumerary centrosomes [

59]. When coupled with PLK4 dysregulation, the likelihood of centrosome amplification increases significantly. Several other proteins involved in centriole duplication, such as STIL and CPAP, are also critical for maintaining proper centriole numbers. Dysregulation of these proteins can disrupt the delicate balance of centriole duplication, further contributing to centrosome amplification [

114].

5.1.2. Causes of Amplification

The causes of centrosome amplification are failure of cell division, defect in the licensing mechanism that restricts centriole duplication or centrosome overduplication [

115,

116,

117]. Mutations in genes that regulate centriole duplication are an important cause. These mutations can alter the function of proteins, resulting in a loss or gain of function affecting centriole duplication. For example, a gain of function mutation of PLK4 results in unregulated initiation of centriole formation, leading to centrosome amplification [

32]. A large analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) genomic and transcriptomic data focusing on the “centrosome-ome” identified MCPH1/microcephalin loss as a major cause of centriole amplification, a mechanism involving an increase in STIL [

118]. Oncogenes, such as c-Myc, can drive the overexpression of centriole duplication proteins [

119] such as the oncogene AURKA which overexpression leads to centrosome amplification [

120]. In the case of AURKA centrosome amplification is due to defect in cell division [

115]. This dysregulation in centrosome number contributes to the oncogenic process, inducing tumorigenesis [

26]. The integrity of the cell cycle checkpoints is crucial for maintaining proper centriole duplication. Failure of these checkpoints, particularly during the G1/S and G2/M transitions, can lead to excessive centriole duplication. For instance, when the G1/S checkpoint fails, cells may enter S phase with supernumerary centrosomes, leading to an amplification phenotype [

110].

Centrosome amplification is driven by dysregulation of centriole duplication proteins and exacerbated by genetic mutations, oncogene activation and checkpoint failure. It has significant implications for cellular function and organismal health.

5.2. Cellular Consequences

The consequences of centrosome amplification are profound and far-reaching, particularly concerning cell division and genomic stability.

5.2.1. Formation of Multipolar Spindles

The presence of extra centrosomes leads to the formation of multipolar spindles during mitosis. In normal mitosis, two centrosomes organize a bipolar spindle, ensuring proper chromosome segregation. However, with more than two centrosomes, cells can develop multipolar spindles, which result in improper chromosome alignment and segregation [

121]. Multipolar spindles significantly increase the risk of chromosome mis-segregation. The additional spindle poles can cause chromosomes to be pulled in multiple directions, resulting in unequal distribution of genetic material during cell division. This mis-segregation can lead to aneuploidy, a state in which cells possess an abnormal number of chromosomes [

32].

5.2.2. Cancer and Chromosomal Instability

Centrosome amplification leads to severe cellular consequences, including the formation of multipolar spindles and chromosome mis-segregation, ultimately resulting in increased chromosomal instability. This aneuploidy resulting from centrosome amplification contributes to chromosomal instability, a hallmark of cancer cells. Cells with abnormal chromosome numbers also often exhibit increased mutation rates, driving tumour progression and metastasis [

122]. The resultant genomic instability can thus facilitate the acquisition of additional mutations that confer survival advantages in the tumour microenvironment. Centrosome amplification has been shown to be sufficient for tumorigenesis [

24,

26]. It promotes cell proliferation and survival, allowing also transformed cells to escape normal regulatory mechanisms. This amplification can thus provide a selective advantage, enabling cancer cells to proliferate uncontrollably [

123,

124].

5.3. Microcephaly and Developmental Defects

Aberrant centriole duplication is not only a feature of cancer but also contributes to developmental disorders, particularly primary microcephaly [

125]. Mutations in genes involved in centriole duplication, such as STIL and CPAP, have been linked to primary microcephaly, a condition characterized by reduced brain size and cognitive impairments. These mutations disrupt normal centriole formation and function, leading to defects in neuronal progenitor cell division and brain development [

126]. In addition to primary microcephaly, aberrant centriole duplication has been associated with various other developmental defects, including syndromes characterized by impaired cilia function, known as ciliopathies. Defective cilia can lead to a range of health issues, including developmental delays and organ malformations, highlighting the critical role of centrioles in normal development [

4,

127]. Aberrant centriole duplication has far-reaching consequences, leading to centrosome amplification, chromosomal instability and developmental disorders. Dysregulation of the proteins involved in centriole duplication, genetic mutations and checkpoint failures all contribute to these abnormalities. It is essential to understand these mechanisms and to assess their impact on human health, in particular to develop strategies to combat cancer and developmental disorders.

6. Centriole Duplication and Disease

Centriole duplication is thus a fundamental cellular process, and its dysregulation is associated with several diseases [

128]. Indeed, understanding the relationship between centriole duplication and these diseases may provide insights into their underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

6.1. Cancer

Centrosome amplification is a common feature of cancer cells and is often correlated with increased tumour aggressiveness [

129]. Studies have shown that approximately 30% to 40% of solid tumours exhibit this phenomenon, which can lead to genomic instability and cancer progression [

32]. Is centrosome amplification a cause or a consequence of cancer? It is clear now that it is both. Not only has centrosome amplification been observed in most cancers, but cancer cells also contain extra-long centrioles [

130]. Centrosome amplification has been proven to promote Tumorigenesis [

26]. The MYC oncogene, known for its role in regulating cell proliferation and growth, has been linked to centrosome amplification when overexpressed [

131]. As said above its effect involved the activation of the transcription of genes involved in centriole duplication. The tumour suppressor p53 plays a critical role in maintaining genomic integrity by regulating cell cycle progression. In normal conditions, p53 induces cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage preventing DNA replication and centriole duplication. Only cell lacking p53 divide with an excess of centrosomes [

115,

132]. And loss of p53 function, that is commonly observed in many cancers, leads to unchecked centriole duplication and subsequent centrosome amplification. Other oncogenes and tumour suppressors also influence centrosome dynamics. For instance, the loss of function of tumour suppressors like APC (Adenomatous Polyposis Coli) [

133]. Mutations in the Ras pathway can lead to enhanced centriole duplication in skin cancer for instance but remarkably in this case only in the presence of p53 gain of function mutants and not in the absence of p53 [

134].

6.1.1. Therapeutic Targeting

Targeting the centriole duplication machinery presents a novel therapeutic avenue in cancer treatment. Because centrosome amplification is observed in almost all kind of cancer and because without PLK4, centrosome cannot duplicate, PKL4 emerged as a priority target [

135]. PLK4 inhibitors could selectively reduce centrosome amplification and subsequent aneuploidy, making them attractive candidates for targeted cancer therapies [

32]. And when it was reported that its depletion by RNA silencing induced apoptosis, PLK4 became an interesting target to inhibit in the context of cancer treatment [

136]. Preclinical studies have subsequently produced very promising results, indicating that PLK4 inhibition may contribute to cancer treatment [

137,

138]. Combining PLK4 inhibitors with chemotherapeutic agents such as sorafenib shows synergistic antitumor effect in vitro and may enhance treatment efficacy [

139]. By reducing centrosome numbers, PLK4 inhibitors could improve the response of cancer cells to these treatments, potentially leading to better patient outcomes [

30].

Centriole duplication dysregulation significantly impacts cancer progression, with centrosome amplification being a critical factor. Oncogenes and tumour suppressors like MYC and p53 play vital roles in regulating this process. Therapeutic targeting of centriole duplication machinery, particularly through PLK4 inhibitors, holds promise for future cancer therapies.

6.2. Neurological Disorders

Microcephaly, a condition characterized by abnormally small head size and associated developmental delays, has been linked to mutations in centriole-related proteins [

140]. Mutations in genes such as STIL, CPAP, and KIFC1 disrupt normal centriole duplication and lead to impaired neurogenesis [

126]. These mutations result in fewer neural progenitor cells, subsequently affecting brain size and development [

141,

142]. The defects in centriole duplication can cause issues during cell division, leading to improper mitotic spindle function and consequent loss of neuronal progenitors. Studies have shown that reduced centriole numbers directly correlate with decreased cell division in the developing brain, resulting in microcephaly [

143]. Fully functional centrioles (Mother centrioles) are also involved in ciliogenesis, in particular primary cilia that plays a crucial role in neurogenesis [

144]. Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) has been reported associated with ciliopathies in particular with Orofaciodigital syndrome I (OFD1) [

145]. OFD1 gene codes for a protein involved in controlling the length on centriole and in the biogenesis of the cilium. Genetic analyses have identified mutations in centriole-associated genes in individuals with ASD [

146].

Centriole duplication defects are implicated in several neurological disorders, including microcephaly and other neurodevelopmental conditions. Mutations in centriole-related proteins disrupt normal brain development, leading to significant cognitive and developmental challenges.

6.3. Ciliopathies

Ciliopathies are a diverse group of genetic disorders caused by defects in cilia formation and function, often linked to impaired centriole duplication. Centrioles serve as basal bodies that anchor cilia, essential for their proper assembly and function. Dysregulation of centriole duplication can lead to the formation of abnormal or dysfunctional cilia, which can disrupt signalling pathways critical for various cellular processes [

147]. Cilia play a crucial role in sensing environmental signals and regulating cellular responses. Impaired ciliogenesis due to centriole duplication defects can affect pathways such as Hedgehog and Wnt signaling, leading to a wide range of developmental and physiological abnormalities [

148,

149]. Ciliopathies are notably associated with disorders like polycystic kidney disease (PKD), characterized by the formation of cysts in the kidneys. Abnormalities in centriole function and subsequent cilia defects contribute to the pathogenesis of PKD [

150]. Another example is Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a condition involving obesity, retinal dystrophy, and polydactyly. Mutations in centriole-related proteins that impair ciliogenesis are implicated in this disorder, illustrating the connection between centriole function and ciliary integrity [

151].

Ciliopathies highlight the essential role of centrioles in cilia formation and function. Defective centriole duplication can lead to impaired cilia, resulting in significant developmental disorders and diseases such as polycystic kidney disease and Bardet-Biedl syndrome.

7. Recent Advances in Visualizing Centriole

Recent years have seen significant advancements in the understanding of centriole duplication, driven by technological innovations and novel discoveries. This section highlights key developments in high-resolution structural analysis, the identification of new regulatory pathways, and the integration of centriole duplication with other cellular processes.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has revolutionized the structural biology landscape, allowing researchers to visualize biological macromolecules at unprecedented resolution. This technique has been pivotal in elucidating the intricate architecture of centrioles. For example, researchers have successfully visualized the cartwheel structure of centrioles, identifying the arrangement of proteins such as SAS-6 and the microtubule triplets that comprise the centriole [

152]. The same is true with electron cryo-tomography (cryo-ET) with the visualization of components that maintain together the triplets of MT that build the centriole [

153]. These insights have confirmed that centrioles possess a unique nine-fold symmetry, which is critical for their function as microtubule-organizing centres (MTOC).

Advances in cryo-EM have also allowed for the visualization of associated proteins involved in centriole stability. For instance, the structures of the microtubule-associated protein SSNA-1 (Sjoegren syndrome nuclear autoantigen 1) that can self assemble to form anti-parallel Coiled-coil stabilizing microtubule-based structures such as centrioles [

154]. Understanding these structural interactions at the molecular level is crucial for deciphering how centriole duplication is initiated and regulated.

Microscopy Techniques such as STED (Stimulated Emission Depletion) and SIM (Structured Illumination Microscopy) have enabled the visualization of centrioles at resolutions beyond the diffraction limit of light revealing the 9-fold structure of the centriole and but also how proteins localise around centrioles during cell cycle progression [

155,

156].

Expansion microscopy (exM) consists in expanding the sample and observing it with fluorescent microscopy. A beautiful work by Laporte and collaborators showing the architecture of a human centriole demonstrates the power of exM [

157].

These techniques have provided insights into the dynamic behavior of centrioles and centriolar proteins during the cell cycle, revealing how structural changes correlate with the protein localisation.

8. Future Directions in Centriole Duplication Research

As research on centriole duplication continues to evolve, several critical areas warrant further investigation. One of the foremost questions in centriole duplication research is how this process is precisely timed and coordinated with the various events occurring during cell cycle progression. While significant progress has been made in identifying the phases during which centriole duplication occurs, the underlying mechanisms that ensure this timing remain poorly understood. How do cells integrate signals from various cell cycle events to influence centriole duplication? Another area of interest is the role of external signals, such as growth factors or stress conditions, in modulating the timing of centriole duplication. Understanding how environmental cues influence the centriole duplication cycle could have profound implications for developmental biology and cancer research, as it may highlight potential points of intervention. Despite significant advancements in identifying key players in centriole duplication, it is likely that many unknown proteins and pathways remain to be discovered. New and increasingly powerful proteomic analysis techniques continue to enrich the repertoire of proteins present in the centrosome [

158]. Studies combining proteomics and transcriptomics have also recently revealed the presence of splicing proteins associated with the centrosome [

159]. These results can be compared with those obtained by a recent analysis of the interactome of the centrosome kinase, Aurora-A, identifying a new function in RNA splicing [

160].

9. Conclusions

Future directions in centriole duplication research promise to uncover critical insights that could enhance our understanding of cell biology and its implications for health and disease. Addressing unanswered questions regarding timing and regulation, overcoming technological challenges in imaging, and exploring therapeutic implications will be essential for advancing the field.

As researchers continue to probe the complexities of centriole duplication, the potential for novel therapeutic strategies will become increasingly tangible, paving the way for innovative treatments for cancer, ciliopathies, and neurological disorders.

The advancements in our understanding of centriole duplication hold significant promise for developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting various diseases.

References

- Bornens M. The centrosome in cells and organisms. Science. 2012 Jan 27;335(6067):422-6. [CrossRef]

- Tassin AM, Bornens M. Centrosome structure and microtubule nucleation in animal cells. Biol Cell. 1999 May-Jun;91(4-5):343-54.

- Boveri, T. (1914). Zur Frage der Entstehung maligner Tumoren. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

- Qi F, Zhou J. Multifaceted roles of centrosomes in development, health, and disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2021 Dec 6;13(9):611-621. [CrossRef]

- Kiermaier E, Stötzel I, Schapfl MA, Villunger A. Amplified centrosomes-more than just a threat. EMBO Rep. 2024 Sep 16. [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa D, Vakonakis I, Olieric N, Hilbert M, Keller D, Olieric V, Bortfeld M, Erat MC, Flückiger I, Gönczy P, Steinmetz MO. Structural basis of the 9-fold symmetry of centrioles. Cell. 2011 Feb 4;144(3):364-75. [CrossRef]

- Le Guennec M, Klena N, Aeschlimann G, Hamel V, Guichard P. Overview of the centriole architecture. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021 Feb;66:58-65. [CrossRef]

- Nigg EA, Raff JW. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009 Nov 13;139(4):663-78. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Ameijeiras J, Lozano-Fernández P, Martí E. Centrosome maturation—in tune with the cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 2022 Jan 15;135(2):jcs259395. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi T, Dynlacht BD. Regulating the transition from centriole to basal body. J Cell Biol. 2011 May 2;193(3):435-44. [CrossRef]

- Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature. 1984 Nov 15-21;312(5991):237-42. [CrossRef]

- Godinho SA, Pellman D. Causes and consequences of centrosome abnormalities in cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014 Sep 5;369(1650):20130467. [CrossRef]

- Nam HJ, Naylor RM, van Deursen JM. Centrosome dynamics as a source of chromosomal instability. Trends Cell Biol. 2015 Feb;25(2):65-73. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez I, Dynlacht BD. Cilium assembly and disassembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2016 Jun 28;18(7):711-7. [CrossRef]

- Basto R, Lau J, Vinogradova T, Gardiol A, Woods CG, Khodjakov A, Raff JW. Flies without centrioles. Cell. 2006 Jun 30;125(7):1375-86. [CrossRef]

- Vorobjev IA, Chentsov YuS. Centrioles in the cell cycle. I. Epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1982 Jun;93(3):938-49. [CrossRef]

- Tsou MF, Stearns T. Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle. Nature. 2006 Aug 24;442(7105):947-51. [CrossRef]

- Lingle WL, Barrett SL, Negron VC, D’Assoro AB, Boeneman K, Liu W, Whitehead CM, Reynolds C, Salisbury JL. Centrosome amplification drives chromosomal instability in breast tumor development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Feb 19;99(4):1978-83. [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Limeta A, Lukasik K, Kong D, Sullenberger C, Luvsanjav D, Sahabandu N, Chari R, Loncarek J. CPAP insufficiency leads to incomplete centrioles that duplicate but fragment. J Cell Biol. 2022 May 2;221(5):e202108018. [CrossRef]

- Martin CA, Ahmad I, Klingseisen A, Hussain MS, Bicknell LS, Leitch A, Nürnberg G, Toliat MR, Murray JE, Hunt D, Khan F, Ali Z, Tinschert S, Ding J, Keith C, Harley ME, Heyn P, Müller R, Hoffmann I, Cormier-Daire V, Dollfus H, Dupuis L, Bashamboo A, McElreavey K, Kariminejad A, Mendoza-Londono R, Moore AT, Saggar A, Schlechter C, Weleber R, Thiele H, Altmüller J, Höhne W, Hurles ME, Noegel AA, Baig SM, Nürnberg P, Jackson AP. Mutations in PLK4, encoding a master regulator of centriole biogenesis, cause microcephaly, growth failure and retinopathy. Nat Genet. 2014 Dec;46(12):1283-1292. [CrossRef]

- Sladky VC, Akbari H, Tapias-Gomez D, Evans LT, Drown CG, Strong MA, LoMastro GM, Larman T, Holland AJ. Centriole signaling restricts hepatocyte ploidy to maintain liver integrity. Genes Dev. 2022 Aug 18;36(13-14):843–56. [CrossRef]

- Boveri T 1888 Zellen-Studien Heft 2, Die Befruchtung und Teilung des Eles von Ascaris megalocephala II. Verlag von Gustav Fischer, Jena, Germany.

- Boveri T. 1900 Ueber die Natur de Centrosomen Zellen-Studien 4. Jena, Germany: G Fisher.

- Basto R, Brunk K, Vinadogrova T, Peel N, Franz A, Khodjakov A, Raff JW. Centrosome amplification can initiate tumorigenesis in flies. Cell. 2008 Jun 13;133(6):1032-42. [CrossRef]

- Dzafic E, Strzyz PJ, Wilsch-Bräuninger M, Norden C. Centriole Amplification in Zebrafish Affects Proliferation and Survival but Not Differentiation of Neural Progenitor Cells. Cell Rep. 2015 Oct 6;13(1):168-182. [CrossRef]

- Levine MS, Bakker B, Boeckx B, Moyett J, Lu J, Vitre B, Spierings DC, Lansdorp PM, Cleveland DW, Lambrechts D, Foijer F, Holland AJ. Centrosome Amplification Is Sufficient to Promote Spontaneous Tumorigenesis in Mammals. Dev Cell. 2017 Feb 6;40(3):313-322.e5. [CrossRef]

- D’Assoro AB, Lingle WL, Salisbury JL. Centrosome amplification and the development of cancer. Oncogene. 2002 Sep 9;21(40):6146-53. [CrossRef]

- Turan MG, Orhan ME, Cevik S, Kaplan OI. CiliaMiner: an integrated database for ciliopathy genes and ciliopathies. Database (Oxford). 2023 Jul 26;2023:baad047. [CrossRef]

- Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Polo-like kinase 4 inhibition: a strategy for cancer therapy? Cancer Cell. 2014 Aug 11;26(2):151-3. [CrossRef]

- Lei Q, Yu Q, Yang N, Xiao Z, Song C, Zhang R, Yang S, Liu Z, Deng H. Therapeutic potential of targeting polo-like kinase 4. Eur J Med Chem. 2024 Feb 5;265:116115. [CrossRef]

- Lacey KR, Jackson PK, Stearns T. Cyclin-dependent kinase control of centrosome duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Mar 16;96(6):2817-22. [CrossRef]

- Nigg EA, Holland AJ. Once and only once: mechanisms of centriole duplication and their deregulation in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018 May;19(5):297-312. [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama R, Dasgupta S, Borisy GG. Independence of centriole formation and initiation of DNA synthesis in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1986;6(4):355-62. [CrossRef]

- Krämer A, Neben K, Ho AD. Centrosome replication, genomic instability and cancer. Leukemia. 2002 May;16(5):767-75. [CrossRef]

- Ko MJ, Murata K, Hwang DS, Parvin JD. Inhibition of BRCA1 in breast cell lines causes the centrosome duplication cycle to be disconnected from the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2006 Jan 12;25(2):298-303. [CrossRef]

- Durcan TM, Halpin ES, Casaletti L, Vaughan KT, Pierson MR, Woods S, Hinchcliffe EH. Centrosome duplication proceeds during mimosine-induced G1 cell cycle arrest. J Cell Physiol. 2008 Apr;215(1):182-91. [CrossRef]

- Gönczy P, Hatzopoulos GN. Centriole assembly at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2019 Feb 20;132(4):jcs228833. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt TI, Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Lavoie SB, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA. Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr Biol. 2009 Jun 23;19(12):1005-11. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Olieric N, Steinmetz MO. Centriole length control. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021 Feb;66:89-95. [CrossRef]

- Sullenberger C, Vasquez-Limeta A, Kong D, Loncarek J. With Age Comes Maturity: Biochemical and Structural Transformation of a Human Centriole in the Making. Cells. 2020 Jun 9;9(6):1429. [CrossRef]

- Faruki S, Cole RW, Rieder CL. Separating centrosomes interact in the absence of associated chromosomes during mitosis in cultured vertebrate cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2002 Jun;52(2):107-21. [CrossRef]

- Agircan FG, Schiebel E, Mardin BR. Separate to operate: control of centrosome positioning and separation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014 Sep 5;369(1650):20130461. [CrossRef]

- Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Wilkinson CJ, Nigg EA. The Polo kinase Plk4 functions in centriole duplication. Nat Cell Biol. 2005 Nov;7(11):1140-6. [CrossRef]

- Holland AJ, Fachinetti D, Da Cruz S, Q, Vitre B, Lince-Faria M, Chen D, Parish N, Verma IM, Bettencourt-Dias M, Cleveland DW. Polo-like kinase 4 controls centriole duplication but does not directly regulate cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2012 May;23(10):1838-45. [CrossRef]

- Tang CJ, Lin SY, Hsu WB, Lin YN, Wu CT, Lin YC, Chang CW, Wu KS, Tang TK. The human microcephaly protein STIL interacts with CPAP and is required for procentriole formation. EMBO J. 2011 Oct 21;30(23):4790-804. [CrossRef]

- Yoshiba S, Tsuchiya Y, Ohta M, Gupta A, Shiratsuchi G, Nozaki Y, Ashikawa T, Fujiwara T, Natsume T, Kanemaki MT, Kitagawa D. HsSAS-6-dependent cartwheel assembly ensures stabilization of centriole intermediates. J Cell Sci. 2019 Jun 20;132(12):jcs217521. [CrossRef]

- Hatch EM, Kulukian A, Holland AJ, Cleveland DW, Stearns T. Cep152 interacts with Plk4 and is required for centriole duplication. J Cell Biol. 2010 Nov 15;191(4):721-9. [CrossRef]

- Sonnen KF, Gabryjonczyk AM, Anselm E, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA. Human Cep192 and Cep152 cooperate in Plk4 recruitment and centriole duplication. J Cell Sci. 2013 Jul 15;126(Pt 14):3223-33. [CrossRef]

- Tang CJ, Fu RH, Wu KS, Hsu WB, Tang TK. CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat Cell Biol. 2009 Jul;11(7):825-31. [CrossRef]

- Inanç B, Pütz M, Lalor P, Dockery P, Kuriyama R, Gergely F, Morrison CG. Abnormal centrosomal structure and duplication in Cep135-deficient vertebrate cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2013 Sep;24(17):2645-54. [CrossRef]

- Gould RR, Borisy GG. The pericentriolar material in Chinese hamster ovary cells nucleates microtubule formation. J Cell Biol. 1977 Jun;73(3):601-15. [CrossRef]

- Marshall WF. Basal bodies platforms for building cilia. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:1-22. [CrossRef]

- Ma D, Wang F, Teng J, Huang N, Chen J. Structure and function of distal and subdistal appendages of the mother centriole. J Cell Sci. 2023 Feb 1;136(3):jcs260560. [CrossRef]

- Woodruff JB, Wueseke O, Hyman AA. Pericentriolar material structure and dynamics. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014 Sep 5;369(1650):20130459. [CrossRef]

- Uzbekov R, Kireyev I, Prigent C. Centrosome separation: respective role of microtubules and actin filaments. Biol Cell. 2002 Sep;94(4-5):275-88. [CrossRef]

- Giet R, Petretti C, Prigent C. Aurora kinases, aneuploidy and cancer, a coincidence or a real link? Trends Cell Biol. 2005 May;15(5):241-50. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Yang Y, Duan Q, Jiang N, Huang Y, Darzynkiewicz Z, Dai W. sSgo1, a major splice variant of Sgo1, functions in centriole cohesion where it is regulated by Plk1. Dev Cell. 2008 Mar;14(3):331-41. [CrossRef]

- Korzeniewski N, Zheng L, Cuevas R, Parry J, Chatterjee P, Anderton B, Duensing A, Münger K, Duensing S. Cullin 1 functions as a centrosomal suppressor of centriole multiplication by regulating polo-like kinase 4 protein levels. Cancer Res. 2009 Aug 15;69(16):6668-75. [CrossRef]

- Arquint C, Nigg EA. The PLK4-STIL-SAS-6 module at the core of centriole duplication. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016 Oct 15;44(5):1253-1263. [CrossRef]

- Blow JJ, Laskey RA. A role for the nuclear envelope in controlling DNA replication within the cell cycle. Nature. 1988 Apr 7;332(6164):546-8. [CrossRef]

- Zitouni S, Nabais C, Jana SC, Guerrero A, Bettencourt-Dias M. Polo-like kinases: structural variations lead to multiple functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014 Jul;15(7):433-52. [CrossRef]

- Vakonakis I. The centriolar cartwheel structure: symmetric, stacked, and polarized. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021 Feb;66:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Ohta M, Ashikawa T, Nozaki Y, Kozuka-Hata H, Goto H, Inagaki M, Oyama M, Kitagawa D. Direct interaction of Plk4 with STIL ensures formation of a single procentriole per parental centriole. Nat Commun. 2014 Oct 24;5:5267. [CrossRef]

- Arquint C, Gabryjonczyk AM, Imseng S, Böhm R, Sauer E, Hiller S, Nigg EA, Maier T. STIL binding to Polo-box 3 of PLK4 regulates centriole duplication. Elife. 2015 Jul 18;4:e07888. [CrossRef]

- Cunha-Ferreira I, Rodrigues-Martins A, Bento I, Riparbelli M, Zhang W, Laue E, Callaini G, Glover DM, Bettencourt-Dias M. The SCF/Slimb ubiquitin ligase limits centrosome amplification through degradation of SAK/PLK4. Curr Biol. 2009 Jan 13;19(1):43-9. [CrossRef]

- Čajánek L, Glatter T, Nigg EA. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Mib1 regulates Plk4 and centriole biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2015 May 1;128(9):1674-82. [CrossRef]

- Grossmann J, Kratz AS, Kordonsky A, Prag G, Hoffmann I. CRL4DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase regulates PLK4 protein levels to prevent premature centriole duplication. Life Sci Alliance. 2024 Mar 15;7(6):e202402668. [CrossRef]

- Guderian G, Westendorf J, Uldschmid A, Nigg EA. Plk4 trans-autophosphorylation regulates centriole number by controlling betaTrCP-mediated degradation. J Cell Sci. 2010 Jul 1;123(Pt 13):2163-9. [CrossRef]

- Cunha-Ferreira I, Bento I, Pimenta-Marques A, Jana SC, Lince-Faria M, Duarte P, Borrego-Pinto J, Gilberto S, Amado T, Brito D, Rodrigues-Martins A, Debski J, Dzhindzhev N, Bettencourt-Dias M. Regulation of autophosphorylation controls PLK4 self-destruction and centriole number. Curr Biol. 2013 Nov 18;23(22):2245-2254. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Martins A, Riparbelli M, Callaini G, Glover DM, Bettencourt-Dias M. Revisiting the role of the mother centriole in centriole biogenesis. Science. 2007 May 18;316(5827):1046-50. [CrossRef]

- Shamir M, Martin FJO, Woolfson DN, Friedler A. Molecular Mechanism of STIL Coiled-Coil Domain Oligomerization. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 27;24(19):14616. [CrossRef]

- Kratz AS, Bärenz F, Richter KT, Hoffmann I. Plk4-dependent phosphorylation of STIL is required for centriole duplication. Biol Open. 2015 Feb 20;4(3):370-7. [CrossRef]

- Dzhindzhev NS, Tzolovsky G, Lipinszki Z, Schneider S, Lattao R, Fu J, Debski J, Dadlez M, Glover DM. Plk4 phosphorylates Ana2 to trigger Sas6 recruitment and procentriole formation. Curr Biol. 2014 Nov 3;24(21):2526-32. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan J, Guichard P, Smith AH, Schwarz H, Agard DA, Marco S, Avidor-Reiss T. Self-assembling SAS-6 multimer is a core centriole building block. J Biol Chem. 2010 Mar 19;285(12):8759-70. [CrossRef]

- van Breugel M, Hirono M, Andreeva A, Yanagisawa HA, Yamaguchi S, Nakazawa Y, Morgner N, Petrovich M, Ebong IO, Robinson CV, Johnson CM, Veprintsev D, Zuber B. Structures of SAS-6 suggest its organization in centrioles. Science. 2011 Mar 4;331(6021):1196-9. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa Y, Hiraki M, Kamiya R, Hirono M. SAS-6 is a cartwheel protein that establishes the 9-fold symmetry of the centriole. Curr Biol. 2007 Dec 18;17(24):2169-74. [CrossRef]

- Gönczy P. Towards a molecular architecture of centriole assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012 Jun 13;13(7):425-35. [CrossRef]

- Hilbert M, Noga A, Frey D, Hamel V, Guichard P, Kraatz SH, Pfreundschuh M, Hosner S, Flückiger I, Jaussi R, Wieser MM, Thieltges KM, Deupi X, Müller DJ, Kammerer RA, Gönczy P, Hirono M, Steinmetz MO. SAS-6 engineering reveals interdependence between cartwheel and microtubules in determining centriole architecture. Nat Cell Biol. 2016 Apr;18(4):393-403. [CrossRef]

- Cottee MA, Raff JW, Lea SM, Roque H. SAS-6 oligomerization: the key to the centriole? Nat Chem Biol. 2011 Sep 19;7(10):650-3. [CrossRef]

- Hung LY, Tang CJ, Tang TK. Protein 4.1 R-135 interacts with a novel centrosomal protein (CPAP) which is associated with the gamma-tubulin complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2000 Oct;20(20):7813-25. [CrossRef]

- Garcez PP, Diaz-Alonso J, Crespo-Enriquez I, Castro D, Bell D, Guillemot F. Cenpj/CPAP regulates progenitor divisions and neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex downstream of Ascl1. Nat Commun. 2015 Mar 10;6:6474. [CrossRef]

- Zheng X, Ramani A, Soni K, Gottardo M, Zheng S, Ming Gooi L, Li W, Feng S, Mariappan A, Wason A, Widlund P, Pozniakovsky A, Poser I, Deng H, Ou G, Riparbelli M, Giuliano C, Hyman AA, Sattler M, Gopalakrishnan J, Li H. Molecular basis for CPAP-tubulin interaction in controlling centriolar and ciliary length. Nat Commun. 2016 Jun 16;7:11874. [CrossRef]

- Lin YC, Chang CW, Hsu WB, Tang CJ, Lin YN, Chou EJ, Wu CT, Tang TK. Human microcephaly protein CEP135 binds to hSAS-6 and CPAP, and is required for centriole assembly. EMBO J. 2013 Apr 17;32(8):1141-54. [CrossRef]

- Hussain MS, Baig SM, Neumann S, Nürnberg G, Farooq M, Ahmad I, Alef T, Hennies HC, Technau M, Altmüller J, Frommolt P, Thiele H, Noegel AA, Nürnberg P. A truncating mutation of CEP135 causes primary microcephaly and disturbed centrosomal function. Am J Hum Genet. 2012 May 4;90(5):871-8. [CrossRef]

- Bamborschke D, Daimagüler HS, Hahn A, Hussain MS, Nürnberg P, Cirak S. Mutation in CEP135 causing primary microcephaly and subcortical heterotopia. Am J Med Genet A. 2020 Oct;182(10):2450-2453. [CrossRef]

- Kim TS, Park JE, Shukla A, Choi S, Murugan RN, Lee JH, Ahn M, Rhee K, Bang JK, Kim BY, Loncarek J, Erikson RL, Lee KS. Hierarchical recruitment of Plk4 and regulation of centriole biogenesis by two centrosomal scaffolds, Cep192 and Cep152. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Dec 10;110(50):E4849-57. [CrossRef]

- Cizmecioglu O, Arnold M, Bahtz R, Settele F, Ehret L, Haselmann-Weiss U, Antony C, Hoffmann I. Cep152 acts as a scaffold for recruitment of Plk4 and CPAP to the centrosome. J Cell Biol. 2010 Nov 15;191(4):731-9. [CrossRef]

- Chang CW, Hsu WB, Tsai JJ, Tang CJ, Tang TK. CEP295 interacts with microtubules and is required for centriole elongation. J Cell Sci. 2016 Jul 1;129(13):2501-13. [CrossRef]

- Löffler H, Fechter A, Matuszewska M, Saffrich R, Mistrik M, Marhold J, Hornung C, Westermann F, Bartek J, Krämer A. Cep63 recruits Cdk1 to the centrosome: implications for regulation of mitotic entry, centrosome amplification, and genome maintenance. Cancer Res. 2011 Mar 15;71(6):2129-39. [CrossRef]

- Fagundes R, Teixeira LK. Cyclin E/CDK2: DNA Replication, Replication Stress and Genomic Instability. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Nov 24;9:774845. [CrossRef]

- Tarapore P, Okuda M, Fukasawa K. A mammalian in vitro centriole duplication system: evidence for involvement of CDK2/cyclin E and nucleophosmin/B23 in centrosome duplication. Cell Cycle. 2002 Jan;1(1):75-81.

- Zhao H, Chen X, Gurian-West M, Roberts JM. Loss of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) inhibitory phosphorylation in a CDK2AF knock-in mouse causes misregulation of DNA replication and centrosome duplication. Mol Cell Biol. 2012 Apr;32(8):1421-32. [CrossRef]

- Okuda M, Horn HF, Tarapore P, Tokuyama Y, Smulian AG, Chan PK, Knudsen ES, Hofmann IA, Snyder JD, Bove KE, Fukasawa K. Nucleophosmin/B23 is a target of CDK2/cyclin E in centrosome duplication. Cell. 2000 Sep 29;103(1):127-40. [CrossRef]

- Fisk HA, Winey M. The mouse Mps1p-like kinase regulates centrosome duplication. Cell. 2001 Jul 13;106(1):95-104. [CrossRef]

- Leidel S., Delattre M., Cerutti L., Baumer K., Gönczy P. SAS-6 defines a protein family required for centrosome duplication in C. elegans and in human cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:115–125. [CrossRef]

- Peel N., Stevens N. R., Basto R., Raff J. W. Overexpressing centriole-replication proteins in vivo induces centriole overduplication and de novo formation. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:834–843. [CrossRef]

- Strnad P., Leidel S., Vinogradova T., Euteneuer U., Khodjakov A., Gönczy P. Regulated HsSAS-6 levels ensure formation of a single procentriole per centriole during the centrosome duplication cycle. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:203–213. [CrossRef]

- Lange BM. Integration of the centrosome in cell cycle control, stress response and signal transduction pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002 Feb;14(1):35-43. [CrossRef]

- Reed SI. The role of p34 kinases in the G1 to S-phase transition. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:529-61. [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama M, Brill JA, Fink GR, Weinberg RA. Collaboration of G1 cyclins in the functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein. Genes Dev. 1994 Aug 1;8(15):1759-71. [CrossRef]

- Lentini L, Iovino F, Amato A, Di Leonardo A. Centrosome amplification induced by hydroxyurea leads to aneuploidy in pRB deficient human and mouse fibroblasts. Cancer Lett. 2006 Jul 8;238(1):153-60. [CrossRef]

- Chan CY, Yuen VW, Chiu DK, Goh CC, Thu KL, Cescon DW, Soria-Bretones I, Law CT, Cheu JW, Lee D, Tse AP, Tan KV, Zhang MS, Wong BP, Wong CM, Khong PL, Ng IO, Bray MR, Mak TW, Yau TC, Wong CC. Polo-like kinase 4 inhibitor CFI-400945 suppresses liver cancer through cell cycle perturbation and eliciting antitumor immunity. Hepatology. 2023 Mar 1;77(3):729-744. [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari S, Bhat V, Athwal H, Cescon DW, Allan AL, Parsyan A. PLK4 as a potential target to enhance radiosensitivity in triple-negative breast cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2024 Feb 16;19(1):24. [CrossRef]

- He G, Siddik ZH, Huang Z, Wang R, Koomen J, Kobayashi R, Khokhar AR, Kuang J. Induction of p21 by p53 following DNA damage inhibits both Cdk4 and Cdk2 activities. Oncogene. 2005 Apr 21;24(18):2929-43. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura T, Saito H, Takekawa M. SAPK pathways and p53 cooperatively regulate PLK4 activity and centrosome integrity under stress. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1775. [CrossRef]

- Tarapore P, Fukasawa K. Loss of p53 and centrosome hyperamplification. Oncogene. 2002 Sep 9;21(40):6234-40. [CrossRef]

- Lambrus BG, Uetake Y, Clutario KM, Daggubati V, Snyder M, Sluder G, Holland AJ. p53 protects against genome instability following centriole duplication failure. J Cell Biol. 2015 Jul 6;210(1):63-77. [CrossRef]

- Lipsick J. A History of Cancer Research: The P53 Pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2025 Feb 3;15(2):a035931. [CrossRef]

- Sabat-Pośpiech D, Fabian-Kolpanowicz K, Prior IA, Coulson JM, Fielding AB. Targeting centrosome amplification, an Achilles’ heel of cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2019 Oct 31;47(5):1209-1222. [CrossRef]

- Delattre M, Gönczy P. The arithmetic of centrosome biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2004 Apr 1;117(Pt 9):1619-30. [CrossRef]

- Remo A, Li X, Schiebel E, Pancione M. The Centrosome Linker and Its Role in Cancer and Genetic Disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2020 Apr;26(4):380-393. [CrossRef]

- Shukla A, Kong D, Sharma M, Magidson V, Loncarek J. Plk1 relieves centriole block to reduplication by promoting daughter centriole maturation. Nat Commun. 2015 Aug 21;6:8077. [CrossRef]

- Holland AJ, Lan W, Niessen S, Hoover H, Cleveland DW. Polo-like kinase 4 kinase activity limits centrosome overduplication by autoregulating its own stability. J Cell Biol. 2010 Jan 25;188(2):191-8. [CrossRef]

- Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA. Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev Cell. 2007 Aug;13(2):190-202. [CrossRef]

- Meraldi P, Honda R, Nigg EA. Aurora-A overexpression reveals tetraploidization as a major route to centrosome amplification in p53-/- cells. EMBO J. 2002 Feb 15;21(4):483-92. [CrossRef]

- Inanç B, Dodson H, Morrison CG. A centrosome-autonomous signal that involves centriole disengagement permits centrosome duplication in G2 phase after DNA damage. Mol Biol Cell. 2010 Nov 15;21(22):3866-77. [CrossRef]

- Denu RA, Shabbir M, Nihal M, Singh CK, Longley BJ, Burkard ME, Ahmad N. Centriole Overduplication is the Predominant Mechanism Leading to Centrosome Amplification in Melanoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2018 Mar;16(3):517-527. [CrossRef]

- Denu RA, Burkard ME. Analysis of the “centrosome-ome” identifies MCPH1 deletion as a cause of centrosome amplification in human cancer. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul 17;10(1):11921. [CrossRef]

- Cui FM, Sun XJ, Huang CC, Chen Q, He YM, Zhang SM, Guan H, Song M, Zhou PK, Hou J. Inhibition of c-Myc expression accounts for an increase in the number of multinucleated cells in human cervical epithelial cells. Oncol Lett. 2017 Sep;14(3):2878-2886. [CrossRef]

- Courapied S, Cherier J, Vigneron A, Troadec MB, Giraud S, Valo I, Prigent C, Gamelin E, Coqueret O, Barré B. Regulation of the Aurora-A gene following topoisomerase I inhibition: implication of the Myc transcription factor. Mol Cancer. 2010 Aug 3;9:205. [CrossRef]

- Khodjakov A, Rieder CL. Mitosis: too much of a good thing (can be bad). Curr Biol. 2009 Dec 1;19(22):R1032-4. [CrossRef]

- Zheng S, Guerrero-Haughton E, Foijer F. Chromosomal Instability-Driven Cancer Progression: Interplay with the Tumour Microenvironment and Therapeutic Strategies. Cells. 2023 Nov 26;12(23):2712. [CrossRef]

- Godinho SA, Picone R, Burute M, Dagher R, Su Y, Leung CT, Polyak K, Brugge JS, Théry M, Pellman D. Oncogene-like induction of cellular invasion from centrosome amplification. Nature. 2014 Jun 5;510(7503):167-71. [CrossRef]

- Kulukian A, Holland AJ, Vitre B, Naik S, Cleveland DW, Fuchs E. Epidermal development, growth control, and homeostasis in the face of centrosome amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Nov 17;112(46):E6311-20. [CrossRef]

- Marthiens V, Rujano MA, Pennetier C, Tessier S, Paul-Gilloteaux P, Basto R. Centrosome amplification causes microcephaly. Nat Cell Biol. 2013 Jul;15(7):731-40. [CrossRef]

- Thornton GK, Woods CG. Primary microcephaly: do all roads lead to Rome? Trends Genet. 2009 Nov;25(11):501-10. [CrossRef]

- Chavali PL, Pütz M, Gergely F. Small organelle, big responsibility: the role of centrosomes in development and disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014 Sep 5;369(1650):20130468. [CrossRef]

- Goundiam O, Basto R. Centrosomes in disease: how the same music can sound so different? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021 Feb;66:74-82. [CrossRef]

- Chan JY. A clinical overview of centrosome amplification in human cancers. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7(8):1122-44. [CrossRef]

- Marteil G, Guerrero A, Vieira AF, de Almeida BP, Machado P, Mendonça S, Mesquita M, Villarreal B, Fonseca I, Francia ME, Dores K, Martins NP, Jana SC, Tranfield EM, Barbosa-Morais NL, Paredes J, Pellman D, Godinho SA, Bettencourt-Dias M. Over-elongation of centrioles in cancer promotes centriole amplification and chromosome missegregation. Nat Commun. 2018 Mar 28;9(1):1258. [CrossRef]