1. Introduction

Insects are the most diverse and adaptable organisms on Earth. While many species contribute positively to biodiversity and food production, others emerge as destructive pests, causing devastating losses to crops, forests, and stored food supplies. (Majeed et al., 2022). According to research statistics from the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), insect pests destroy crop yields annually by 20-40%, costing 220 billion USD. This adaptability is deeply rooted in chemo-diversity, representing the range of chemicals insects use for communication, defence, and survival. However, pests' ability to become resilient relies on their ability to respond to environmental cues from both living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) sources, thus creating fascinating research areas for scientists. (Savopoulou-Soultani et al., 2012).

The increase and decrease of insect pest populations are driven by several complex interactions between biotic and abiotic factors that influence their survival, reproduction, and adaptability. These factors also impact how pests chemically adapt to their surroundings.(Savopoulou-Soultani et al., 2012). However, chemo-diversity is at the core of this adaptability, representing the range of chemicals insects use for communication, defence, and survival. Numerous insect species, pollinators, and natural predators depend heavily on these chemical compounds for survival. (Mishra et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding these intricate biotic and abiotic interactions, particularly the role of chemo-diversity, can lead to innovative pest control strategies, manipulation of pest behaviour, and maintenance of ecological balance. The following sections explore green peach aphids (Myzus persicae) as model pest species to illustrate the complexity of interactions.

2. Green Peach Aphids (Myzus persicae)

Myzus persicae (Sulzer, Hemiptera; Aphididae) feeds on over a hundred crop species from 40 different families, which aids its reproduction and population. Despite differences in susceptibility of crops to the pest, the youngest tissue of the plant conceals large aphid populations (Heathcote, 1962). The adults range from 1.2 to 2.5mm; the wingless individuals differ in green to yellowish green colour, while the pinkish individuals from the same colony eventually grow wings(nymphs). The winged ones can be directly distinguished by a dark patch on their abdomen that is indented and punctured. Parthenogenetic M. persicea reproduces both asexually and sexually all year round by alternating between its primary (prunus trees) and secondary host (vegetable crops) at the cycles of the year; however, most time is spent as an asexual mode. Its development is further divided into holocyclic and anholocyclic types based on progenitors involved, and further depends on climatic conditions, mainly, and genetic variability.(Blackman, 1974)However, in the same climatic conditions, some aphids can reproduce sexual morphs in the two developmental conditions (holocyclic and anholocyclic), depending on temperature and photoperiodism. The differences observed in reproduction create an avenue to understand the influence of environmental and genetic factors on the development cycle of M. persicae.

Figure 1.

Green peach aphid, Myzus persicea. Apterous (wingless) on the left and Alate winged on the right. INRAE (2018): Encyclopaphids.

Figure 1.

Green peach aphid, Myzus persicea. Apterous (wingless) on the left and Alate winged on the right. INRAE (2018): Encyclopaphids.

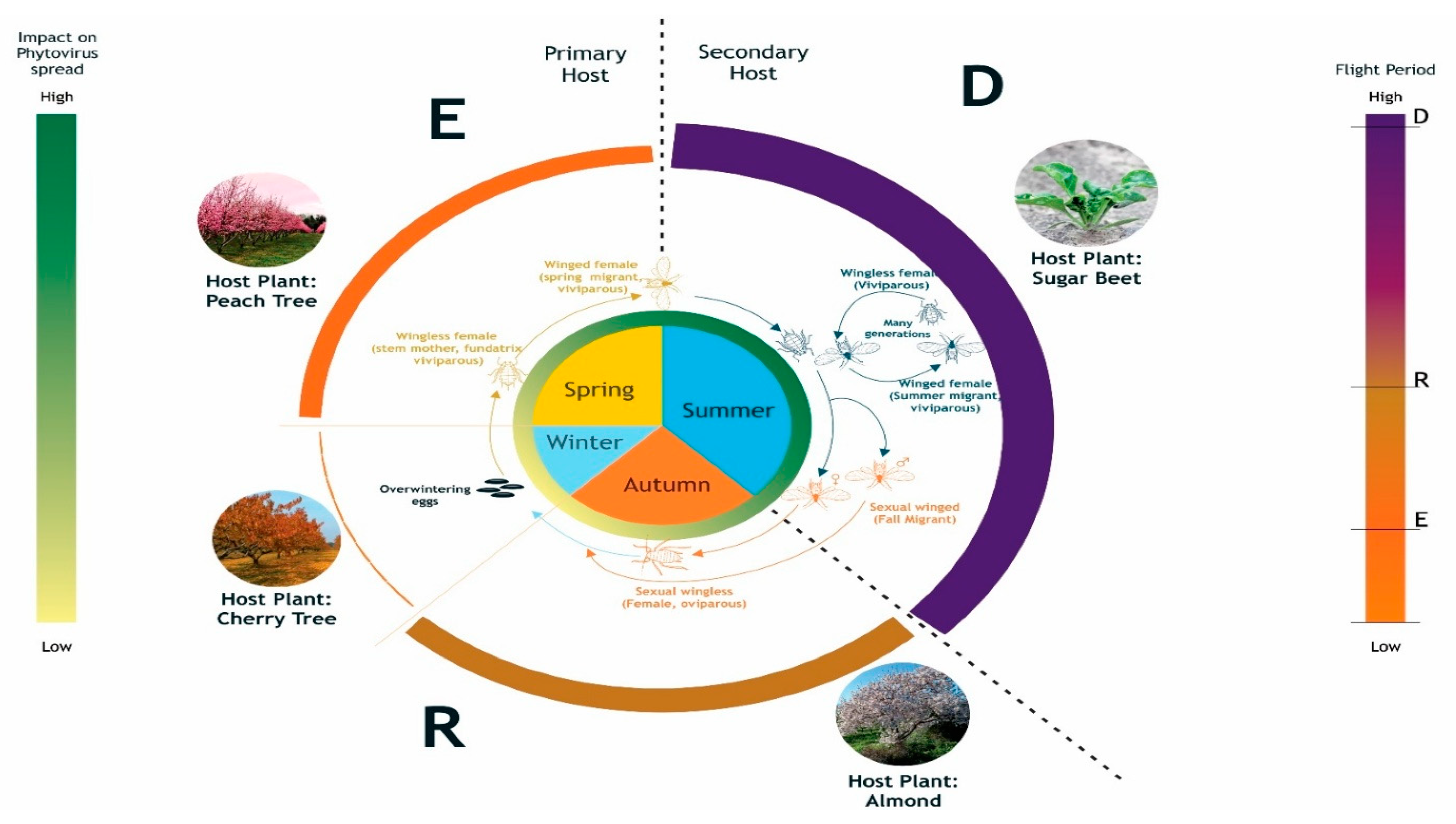

3. Development Cycle of Myzus persicea

Development can be rapid in mild climates, with over 20 annual generations. Females can give birth to the first offspring in an average of 14.8 days, and the larvae require about 15-20°c to mature in 15 days. Finally, 21 generations were observed and determined to be the maximum in conducted experiments. (Capinera, 1969). Winged aphids are increased simultaneously with population density, which aids the dispersal of the virus to summer hosts. Eggs, which measure about 0.6mm to 0.3mm, can overwinter on a prunus tree, and during the spring, the eggs hatch into nymphs, which can feed on young foliage and stems. Approximately forty larvae are produced from each egg by the fundatrigenia process in the middle of spring, then migrate to secondary hosts, which are also economically important. The ability to alternate host by overwintering gives the possibility to have both modes of reproduction in the same region, like France (temperate) (Guillemaud et al., 2003)The secondary host, including abandoned beet harvests, aids the survival of adults and larvae during winter. From the middle of May, three or four generations, either with wings or without, can be found on beets. At the beginning of fall, winged and sexual adults return, with winged males seen on the beets.

Figure 2.

The picture depicts the lifecycle of Myzus persicea, the alternating host plants and the different flight stages all year round (emigration, dispersal and return). (Corel draw; ONI Joshua).

Figure 2.

The picture depicts the lifecycle of Myzus persicea, the alternating host plants and the different flight stages all year round (emigration, dispersal and return). (Corel draw; ONI Joshua).

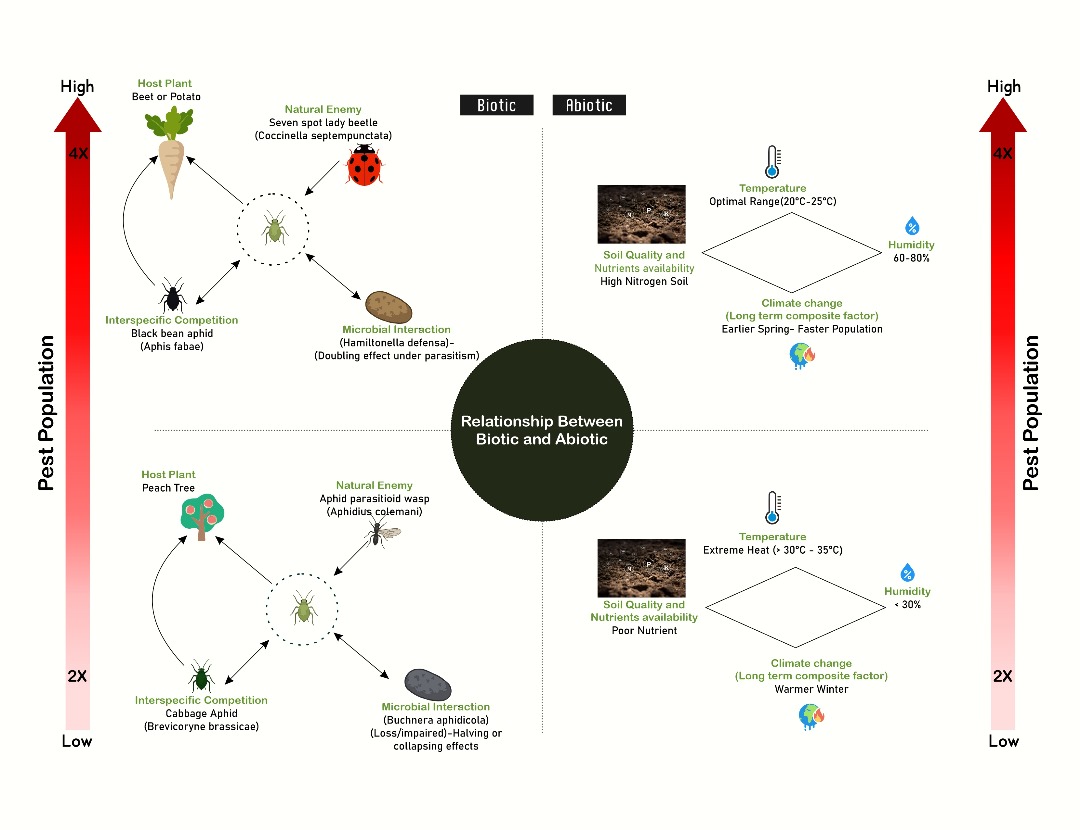

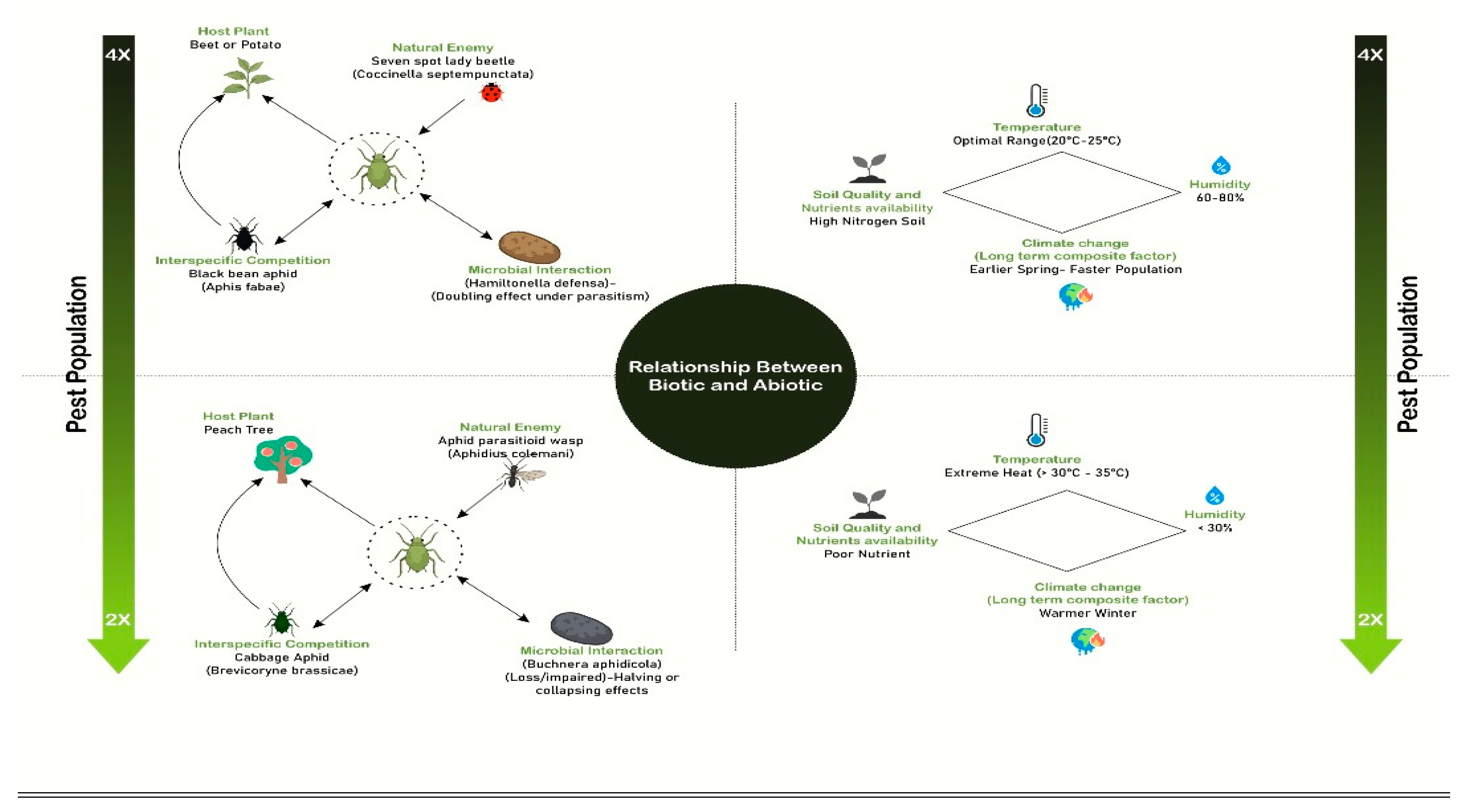

4. Biotic Factors Influencing the Pest Population and Myzus persicae.

The living components of their environment mainly determine the survival, reproduction, and adaptability of insect pests. These factors influence their population dynamics and biochemical mechanisms. It includes host plants, which provide food resources and affect insect pests' metabolism due to their chemical composition. Depending on the species, plants can attract or repel insect pests using their secondary metabolites, including phenolics, terpenoids, and alkaloids. (Mishra et al., 2020). Interestingly, pests often respond by evolving specialised detoxification mechanisms or selective feeding behaviours to counteract plant defences. Some even use substances obtained from plants to protect themselves against predators. (War et al., 2020). Natural enemies like predators, parasitoids, and pathogens can also significantly impact insect populations by controlling and altering their chemical defence (Majeed et al., 2022). However, interspecific competition among insect species further shapes their survival strategies and biochemical composition (Khaliq et al., 2014). Thus, it affects the generation of semiochemicals, mediating interactions between competing species and causing changes in population structure.(Tewari et al., 2014). Furthermore, microbial interactions such as symbiotic relationships with bacteria and fungi also play a fundamental role in insect pest metabolism, adaptation and resistance to control measures, thus influencing their abundance and distribution. (Disi et al., 2018). The specific case of M. persicae further demonstrates how biotic interactions infleunces its population growth, survival and adaptability.

4.1. Influence of Biotic Factors on Myzus persicae: Host Plant and Natural Enemies

Host plant availability or quality can influence the population of aphids due to their crucial role in the developmental period and survival. (La Rossa et al., 2013). Scientists also established that even cultivar or variety differences of the same plant can influence aphid species. (Akköprü et al., 2015). Thus, this correlation can be used to study the tolerance level of any host plant to insect herbivores. (Goundoudaki et al., 2003; Güncan & Gümüş, 2017). Ali et al., 2021 Highlighted the survival, fecundity and population growth rates of chilli pepper and Chinese cabbage. Cabbage was a poor host, hence reducing the reproduction and development rate. Life tables are used to forecast pest outbreaks and create integrated pest management strategies by demonstrating through age-stage, two-sex life table analysis that differences in host plant quality substantially impact aphid demographic parameters(Bailey et al., 2011; Chi & Liu, 1985). Furthermore, host plant factors such as physico-morphological traits, nutritional quality and chemical composition significantly impact the dynamics of aphid populations, highlighting the necessity of host plant-resistant integrated pest management techniques.(Goundoudaki et al., 2003; Jahan et al., 2014).

Coccinellidae (Coccinella undecimpunctata) has a predator-prey numerical interaction with M. persicae, directly converting prey into food for more predators. This relationship is termed a functional response.(Cabral et al., 2009) Coccinella undecimpunctata demonstrated a strong predatory effect on Myzus persicae in lab experiments. Both adults and larvae in their fourth instar displayed great voracity, especially at rising aphid numbers.(Omkar & James, 2004; Omkar & Pervez, 2004; Omkar & Srivastava, 2003). Larvae in their fourth instar ingested a lot more aphids than adults because they needed more energy for growth and pupation, and had less handling time.(Evans & Gunther, 2005) The predator exhibited a Type II functional response, which is characteristic of coccinellids. It showed a sharp rise in predation rate with prey density until saturation. (Ferran & Dixon, 2013; Moura et al., 2006). Additionally, adults spread out more widely throughout the field to find new colonies, but larvae stayed longer in aphid-rich areas and exercised strong localised control. (Dostalkova et al., 2002). While biotic factors such as host plants and predators play a significant role, non-living abiotic factors equally influence pest populations by altering their physiological and biochemical responses.

5. Abiotic Factors and Their Impact on Insect Pests and Myzus persicae

Abiotic factors also drastically affect the population of any insect pest. These non-living components can shape insect reproduction, survival, migration, and biochemical responses, affecting their adaptability and interactions with other organisms. Among these factors, temperature and climate extremes (TE and CE) has been highlighted for its capacity to surpass insect adaptive limits, disrupt food web, phenological mismatches and cycle breakdown in insect communities(Harvey et al., 2020). Studies have indicated that warmer temperatures often accelerate insect metabolism and reproduction, leading to more frequent and severe pest outbreaks (Zhang et al., 2014). On the other hand, extreme heat or prolonged drought can affect development, causing physiological stress that alters insect chemo-diversity. Similarly, humidity and precipitation also influence the availability of host plants, fungal pathogens, and natural enemies, impacting insect populations (Bale et al., 2002; Deutsch et al., 2008). Other crucial factors include: soil quality and nutrient availability; climate change; environmental pollutants such as heavy metals, pesticides, and industrial contaminants; and other environmental stressors such as habitat destruction(Scheirs & De Bruyn, 2002). These factors collectively impact insect pest populations and chemo-diversity by disrupting plant-insect interactions, altering plant chemistry and influencing pest adaptation and resistance(Sánchez-Bayo & Wyckhuys, 2019).

5.1. Influence of Abiotic Factors on Myzus persicae

Aphids (Green Peach Aphids), can be impacted by extreme weather events like heat waves and daily fluctuations in several ways, including decreased fecundity and population growth, slowed development, and altered community structure and trophic cascades due to their effects on individual species' performance and the strength of their interactions with one another.(Colinet et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2014). Gillespie et al., 2012, discovered that M. persicae daily or weekly exposure to 32°c or 40°c reduced aphid population and winged morphs formation. Lastly, they are more sensitive to acute changes in temperatures compared the length of exposure to extreme conditions(Davis et al., 2006). These abiotic stresses, in conjunction with biotic interactions, highlight the necessity of adaptive pest control techniques that account for environmental variability.

6. Implications for Pest Management and Future Research Directions

Integrated pest management (IPM) is improving by understanding insect ecological interactions and manipulating environmental factors to suppress pest populations. (Stenberg, 2017). As environmental challenges continue to evolve, climate-smart agriculture also aims to comprehend how environmental changes affect insect behaviour, presenting opportunities for interdisciplinary research. However, critical research gaps persist in fully mapping the complex mechanisms by which habitat modifications, temperature extremes, humidity, precipitation, pesticide exposure, and climate change collectively influence insect metabolism and population dynamics. Therefore, future research may prioritize leveraging insect chemo-diversity to develop sustainable pest control strategies, promoting climate-smart agriculture and precision pest management.

Figure 3.

A picture to represent the Biotic and Abiotic factors that influence the aphid population.

Figure 3.

A picture to represent the Biotic and Abiotic factors that influence the aphid population.

Conclusion

To sum it up, the complex relationship between insect pest populations and chemo-diversity is vital for effective pest management and ecological balance. Biotic and Abiotic factors collectively drive insect evolution and adaptive strategies. This can be significantly explored for integrated pest control strategies. Insects’ biochemical plasticity further enables them to adapt to environmental shifts and control measures, thus emphasizing the need for integrated pest management (IPM) approaches. By deepening our understanding of how biotic and abiotic factors drive insect chemo-diversity and adaptation, we can pave the way for more resilient and sustainable agricultural systems

References

- Akköprü, E. P., Atlıhan, R., Okut, H., & Chi, H. (2015). Demographic Assessment of Plant Cultivar Resistance to Insect Pests: A Case Study of the Dusky-Veined Walnut Aphid (Hemiptera: Callaphididae) on Five Walnut Cultivars. Journal of Economic Entomology, 108(2), 378–387. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. Y., Naseem, T., Arshad, M., Ashraf, I., Rizwan, M., Tahir, M., Rizwan, M., Sayed, S., Ullah, M. I., Khan, R. R., Amir, M. B., Pan, M., & Liu, T.-X. (2021). Host-Plant Variations Affect the Biotic Potential, Survival, and Population Projection of Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Insects, 12(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R., Chang, N.-T., & Lai, P.-Y. (2011). Two-sex life table and predation rate of Cybocephalus flavocapitis Smith (Coleoptera: Cybocephalidae) reared on Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae), in Taiwan. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 14(4), 433–439. [CrossRef]

- Bale, J. S., Masters, G. J., Hodkinson, I. D., Awmack, C., Bezemer, T. M., Brown, V. K., Butterfield, J., Buse, A., Coulson, J. C., Farrar, J., Good, J. E. G., Harrington, R., Hartley, S., Jones, T. H., Lindroth, R. L., Press, M. C., Symrnioudis, I., Watt, A. D., & Whittaker, J. B. (2002). Herbivory in global climate change research: Direct effects of rising temperature on insect herbivores. Global Change Biology, 8(1), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Blackman, R. L. (1974). Life-cycle variation of Myzus persicae (Sulz.) (Hom., Aphididae) in different parts of the world, in relation to genotype and environment. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 63(4), 595–607. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, S., Soares, A. O., & Garcia, P. (2009). Predation by Coccinella undecimpunctata L. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on Myzus persicae Sulzer (Homoptera: Aphididae): Effect of prey density. Biological Control, 50(1), 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Capinera, J. L. (1969). Green Peach Aphid, Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphididae). EDIS, 2004(6). [CrossRef]

- Chi, H., & Liu, H. (1985). Two new methods for the study of insect population ecology. Bull. Inst. Zool. Acad. Sin, 24(2), 225–240.

- Colinet, H., Sinclair, B. J., Vernon, P., & Renault, D. (2015). Insects in fluctuating thermal environments. Annual Review of Entomology, 60(1), 123–140.

- Davis, J. A., Radcliffe, E. B., & Ragsdale, D. W. (2006). Effects of high and fluctuating temperatures on Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Environmental Entomology, 35(6), 1461–1468.

- Deutsch, C. A., Tewksbury, J. J., Huey, R. B., Sheldon, K. S., Ghalambor, C. K., Haak, D. C., & Martin, P. R. (2008). Impacts of climate warming on terrestrial ectotherms across latitude. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(18), 6668–6672. [CrossRef]

- Disi, J. O., Zebelo, S., Kloepper, J. W., & Fadamiro, H. (2018). Seed inoculation with beneficial rhizobacteria affects European corn borer (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) oviposition on maize plants. In ENTOMOLOGICAL SCIENCE (Vol. 21, Issue 1, pp. 48–58). [CrossRef]

- Dostalkova, I., Kindlmann, P., & Dixon, A. F. (2002). Are classical predator–prey models relevant to the real world? Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218(3), 323–330.

- Evans, E. W., & Gunther, D. I. (2005). The link between food and reproduction in aphidophagous predators: A case study with Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). European Journal of Entomology, 102(3), 423.

-

FAO’s Plant Production and Protection Division. (2022). FAO. [CrossRef]

- Ferran, A., & Dixon, A. F. (2013). Foraging behaviour of ladybird larvae (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). EJE, 90(4), 383–402.

- Gillespie, D. R., Nasreen, A., Moffat, C. E., Clarke, P., & Roitberg, B. D. (2012). Effects of simulated heat waves on an experimental community of pepper plants, green peach aphids and two parasitoid species. Oikos, 121(1), 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Goundoudaki, S., Tsitsipis, J. A., Margaritopoulos, J. T., Zarpas, K. D., & Divanidis, S. (2003). Performance of the tobacco aphid Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on Oriental and Virginia tobacco varieties. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 5(4), 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Guillemaud, T., Mieuzet, L., & Simon, J.-C. (2003). Spatial and temporal genetic variability in French populations of the peach–potato aphid, Myzus persicae. Heredity, 91(2), 143–152.

- Güncan, A., & Gümüş, E. (2017). Influence of Different Hazelnut Cultivars on Some Demographic Characteristics of the Filbert Aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 110(4), 1856–1862. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J. A., Heinen, R., Gols, R., & Thakur, M. P. (2020). Climate change-mediated temperature extremes and insects: From outbreaks to breakdowns. Global Change Biology, 26(12), 6685–6701. [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, G. D. (1962). The suitability of some plant hosts for the development of the peach-potato aphid, Myzus persicae (Sulzer). Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 5(2), 114–118.

- Jahan, F., Abbasipour, H., Askarianzadeh, A., Hassanshahi, G., & Saeedizadeh, A. (2014). Biology and Life Table Parameters of Brevicoryne brassicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on Cauliflower Cultivars. Journal of Insect Science, 14(1), 284. [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A. M., Javed, M., Sohail, M., & Sagheer, M. (2014). Environmental effects on insects and their population dynamics. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 2(2), 1–7.

- La Rossa, F. R., Vasicek, A., & López, M. C. (2013). Effects of Pepper (Capsicum annuum) Cultivars on the Biology and Life Table Parameters of Myzus persicae (Sulz.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Neotropical Entomology, 42(6), 634–641. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, W., Khawaja, M., Rana, N., de Azevedo Koch, E. B., Naseem, R., & Nargis, S. (2022). Evaluation of insect diversity and prospects for pest management in agriculture. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 42(3), 2249–2258. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. S., Shroff, S., Sahu, J. K., Naik, P. P., & Baitharu, I. (2020). Insect Pheromones and Its Applications in Management of Pest Population. In D. Kumar & M. Shahid (Eds.), Natural Materials and Products from Insects: Chemistry and Applications (pp. 121–136). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Moura, R., Cabral, S., & Soares, A. O. (2006). Does pirimicarb affect the voracity of the euriphagous predator, Coccinella undecimpunctata L.(Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)? Biological Control, 38(3), 363–368.

- Omkar, & James, B. E. (2004). Influence of prey species on immature survival, development, predation and reproduction of Coccinella transversalis Fabricius (Col., Coccinellidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 128(2), 150–157.

- Omkar, O., & Pervez, A. (2004). Functional and numerical responses of Propylea dissecta (Col., Coccinellidae).

- Omkar, & Srivastava, S. (2003). Influence of six aphid prey species on development and reproduction of a ladybird beetle, Coccinella septempunctata. BioControl, 48, 379–393.

- Sánchez-Bayo, F., & Wyckhuys, K. A. G. (2019). Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biological Conservation, 232, 8–27. [CrossRef]

- Savopoulou-Soultani, M., Papadopoulos, N. T., Milonas, P., & Moyal, P. (2012). Abiotic factors and insect abundance. In Psyche: A Journal of Entomology (Vol. 2012, Issue 1, p. 167420). Hindawi Publishing Corporation.

- Scheirs, J., & De Bruyn, L. (2002). Integrating optimal foraging and optimal oviposition theory in plant–insect research. Oikos, 96(1), 187–191.

- Stenberg, J. A. (2017). A Conceptual Framework for Integrated Pest Management. Trends in Plant Science, 22(9), 759–769. [CrossRef]

- Tewari, S., Leskey, T. C., Nielsen, A. L., Piñero, J. C., & Rodriguez-Saona, C. R. (2014). Chapter 9—Use of Pheromones in Insect Pest Management, with Special Attention to Weevil Pheromones. In D. P. Abrol (Ed.), Integrated Pest Management (pp. 141–168). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- War, A. R., Buhroo, A. A., Hussain, B., Ahmad, T., Nair, R. M., & Sharma, H. C. (2020). Plant Defense and Insect Adaptation with Reference to Secondary Metabolites. In J.-M. Mérillon & K. G. Ramawat (Eds.), Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites (pp. 795–822). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Cao, Z., Wang, Q., Zhang, F., & Liu, T.-X. (2014). Exposing eggs to high temperatures affects the development, survival and reproduction of Harmonia axyridis. Journal of Thermal Biology, 39, 40–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F., Zhang, W., Hoffmann, A. A., & Ma, C.-S. (2014). Night warming on hot days produces novel impacts on development, survival and reproduction in a small arthropod. Journal of Animal Ecology, 83(4), 769–778.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).