1. Introduction

Trophic transfer of essential and potentially toxic trace elements in marine food webs is an important environmental research area [

1]. In particular, heavy metals such as mercury (Hg) are of great concern, since they may be transferred from the abiotic aquatic environment (water, sediments) to living organisms with accumulation in diverse components of food chains and with a potentially toxic effect. While Hg is naturally emitted mainly from volcanoes, geothermal sources, and soils, it is continually recycled and re-emitted to the atmosphere and deposited on the sea surface [

2]. However, over the last century, the total Hg concentration in the marine environment has increased drastically due to anthropogenic sources [

3]. Methylmercury (MeHg) is the most toxic form of this element due to its capacity for absorption through cell membranes, producing several physiological changes like oxidative stress and neurotoxicity among others [

4]. In that sense, a full comprehension of global sources, speciation, and transport of Hg is necessary to understand the final contribution to MeHg production in aquatic systems, and therefore to its accumulation and transfer among wildlife [

5].

In aquatic systems, pH, dissolved organic matter, and oxygen have a remarkable influence on the Hg cycle [

6]. Mercury methylation rates depend to some extent, on the availability of electron acceptors (O, N, S, Fe) because they influence the metabolism of sulfate-reducing bacteria [

7]. Thus, acidic waters and reducing conditions, associated with low dissolved oxygen (O

2), favor Hg methylation. Some processes connected with global climate change, such as the expansion of the minimum oxygen zones (MOZ) in the tropics, can modify and enhance the presence and abundance of Hg methylation microbiota [

8], ultimately increasing MeHg availability. Additionally, it is known that long-lived top predatory fishes such as sharks, through processes like bioaccumulation and biomagnification, tend to have high concentrations of MeHg in their tissues, particularly in muscle (edible part), which may have serious implications for wildlife and human health [

9].

In contrast, selenium (Se) is an essential element for all organisms that are distributed globally in organic-rich sedimentary rocks. Most of its forms can be quickly transformed and incorporated into food webs [

10]. Indeed, organic Se is the most bio-available chemical form, so the primary route of exposure to Se in marine consumers is through the diet rather than the water [

11]. However, this element is also supplied to aquatic systems as a by-product of several human activities such as coal-fired energy plants, agriculture, refining of crude oil, and coal mining, leading to elevated levels of Se. These elevated levels have resulted in the degradation of several ecosystems and have been linked to reproductive impairment in important fish species [

12]. Selenium is also known to prevent Hg toxicity in the body, through an interaction mechanism that occurs in the organism when both elements are present in high concentrations [

13]. Mercury binds to Se with high affinity, so there is enough evidence suggesting that during the antagonistic interaction, MeHg sequesters the available Se in the body, preventing it from performing its essential physiological roles. Therefore, Hg poisoning can lead to symptoms resembling a Se deficit [

14].

Mercury magnification in the food web is a form of bioaccumulation, often measured using the Biomagnification Factor (BMF) to compare contaminant levels in predators and prey [

15]. But recently a more comprehensive approach has been proposed where the biomagnification potential of an element from a lower to a higher trophic level could be determined by a Trophic Transfer Factor (TTF), obtained from the slope of logarithmically concentrations of chemicals in organisms versus the trophic levels of the organisms in the food chain [

16].

Blue sharks are one of the most abundant apex predators worldwide and therefore one of the main species of fish caught by longline fisheries, which certainly occurs along the California Current Large Marine Ecosystem (CCLME) [

17]. This species can accumulate high levels of toxic elements through their diet, potentially reaching unacceptable levels for consumption [

18]. Blue sharks are not commonly traded in the U.S. due to the low quality of their meat [

19], but they are captured in Mexico for human consumption locally and for exportation [

20]. So, the current conservation status of this species has raised concern due to the global demand for its meat, fins, and liver oil [

21]. In Mexico, blue shark catches make up a significant portion of fisheries landings (about 80%), with most of the catch (90%) being consumed domestically due to its availability and low cost. [

22]. This study aimed to quantify the dietary contribution to the accumulation of mercury (Hg) and selenium (Se) in the muscle of blue sharks, considering the high potential of biomagnification of Hg and the possible biodilution of Se due to its antagonistic behavior, with the final purpose to assess the potential human health risks associated with consuming this shark meat.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Specimens

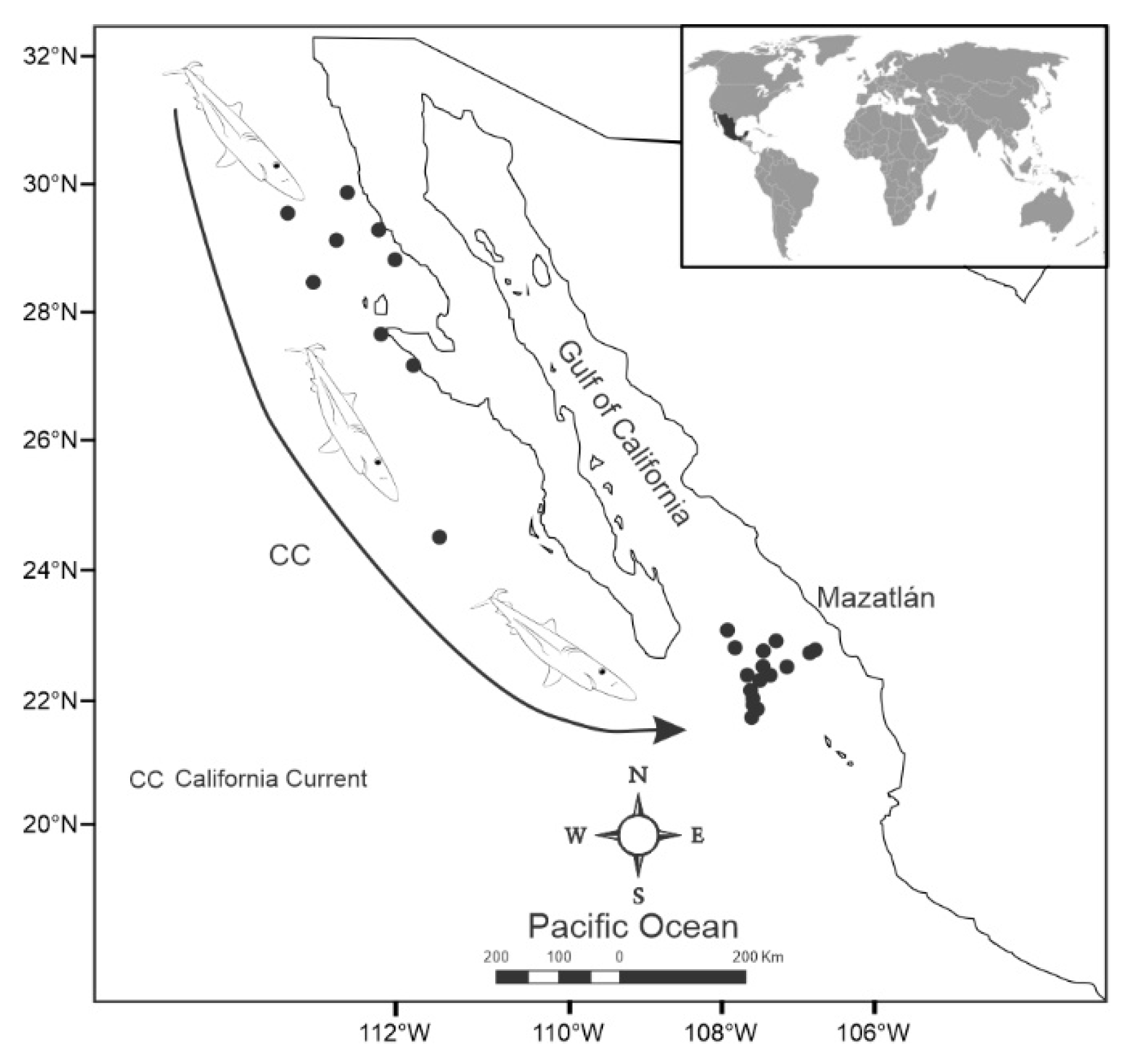

Twenty-three blue shark specimens were collected from oceanographic campaigns carried out by the Mexican Institute for Research in Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture (IMIPAS) between 2019 and 2023 in the north Mexican Pacific (

Figure 1). The sharks were captured using hook lines during the closed season from May to July. Specimens that did not survive the tagging process were retained for further study. Each shark's weight, length, and sex were recorded, and muscle tissue samples (20 g) were collected and stored at -4°C. Additionally, samples of the blue shark's main prey items in the study area were collected [

23,

24,

25], including the red crab (

Pleuroncodes planipes), the squid (

Gonatus spp.), the anchovy (

Engraulis mordax) and the mackerel (

Scomber japonicus) (

Figure 1). Prey items were collected with a trawl net.

2.2. Sampling Procedure

Blue shark muscle and complete prey organisms were freeze-dried (140 x 10-3 mBar; -49° C) for 72 h on Labconco equipment. Dry tissues were manually ground in an agate mortar. Homogenized powdered samples were digested with concentrated nitric acid (69%) (Trace Metal Grade) in stoppered vials for 3h at 120 °C [

26]. Concentrations of Se were measured by graphite furnace-atomic absorption spectrophotometry (GF-AAS) with Zeeman correction background (AAnalyst 800, Perkin-Elmer) equipment. In addition, concentrations of Hg were measured by cold vapor-atomic absorption spectrophotometry (CV-AAS) in Buck Scientific equipment. Quality control of elemental analyses included blanks, duplicates, ultra-pure water (milli-Q, 18.2 MΩ cm), trace metal grade acids, and reference materials. Reference materials used were obtained from the National Research Council of Canada, dogfish muscle (DORM-3) for shark and fish samples, and lobster hepatopancreas (TORT-2) for squids and red crabs. The recovery percentage was 105 ±7 .4% (Se) and 101 ± 0.1% (Hg) in DORM-3 and 103 ± 0.06% (Se) and 100 ± 0.32% (Hg) in TORT-2. The limits of detection (two times the standard deviation of a blank) were 2.1 µg/L for Se and 0.11 µg/L for Hg. Conversions of concentration units from dry weight to wet weight were calculated considering the humidity percentage in muscle (for shark and fish tissue 75%) and for invertebrates (squids and crabs 50%) respectively. Concentration units of Se and Hg are given as μg.g

-1 wet weight.

2.3. Data Analysis

BMF was calculated using equation 1 [

27]:

BMF calculations were made based on the assumption that the concentrations of elements (Hg and Se) have reached a steady state in the sampled tissues. BMF > 1 indicates that biomagnification of the element is occurring [

28].

The TTF to assess the biomagnification or biodilution of an element through the sample food chain was analyzed by equations (2) and (3) [

29]:

Where

a is the intercept of the regression between log10[element concentration] and TL (trophic level), depending on the element background concentrations [

30],

b is the slope of the regression line [

31] representing the biomagnification or biodilution capacity of an element [

32].

Finally, the antilog of the slope b which is the relationship between log10 transformed concentrations (µg.g

−1 ww) and TL, is used to calculate the TTF. Predator and prey TL was taken from bibliographic references [

33]. Biomagnification causes a TTF>1. So, TTF above 1 implies a disequilibrium between organisms and the media (water) that increases with the TL. Slope b was weighted by linear regression for both elements. The correlation coefficient (R

2) was assessed using the Pearson method (statistically significant at p<0.05). Both simple linear models were displayed with R software (R Core Team, 2024).

We calculated the hazard quotient (HQ) of Hg concentrations in the muscular tissues of the blue shark. Values of HQ were calculated using equation 4 [

34]:

Where

E is the exposure level or intake of total Hg,

RfD is the reference dose for total Hg (0.5 μg/kg body weight/day) [

35], and the Exposure level is calculated from equation 5:

Where

C is the concentration of total Hg in the edible part of the fish in wet weight,

I is the intake rate of shark meat expressed in grams per day per capita, determined as 17.38 g.day

-1 for the local population [

36]; W is the weight of an average adult in Mexico (70 Kg).

3. Results

3.1. Mercury and Selenium Assessment

Firstly, when comparing mercury (Hg) levels in the blue shark prey, we found that they were consistently higher than previously reported values in the study area for three species (P. planipes, S. japonicus, and E. mordax). Previous studies in the area [

22] reported Hg concentration values below 0.05 µg.g

−1 ww, while our results showed values above 0.2 µg.g

−1 ww in all reported prey (

Table 1). The Hg average concentration in the muscle of the shark P.glauca was below the recommended limit of 1 μg.g

−1 ww set by national and international standards [

36,

37] (

Table 1). In contrast, selenium (Se) levels were lower than those previously reported for some prey [

22], where authors reported values of 0.83 µg.g

-1 ww for S. japonicus and 0.90 µg.g

-1 ww for P. planipes, while the mean Se values in this study were below 0.35 µg.g

-1 ww (

Table 1).

Nevertheless, molar ratios above 1 in all of the preys suggested a molar excess of Se, so in consequence, this element could be available to protect the organism against Hg toxicity.

3.2. Trophic Transfer Models

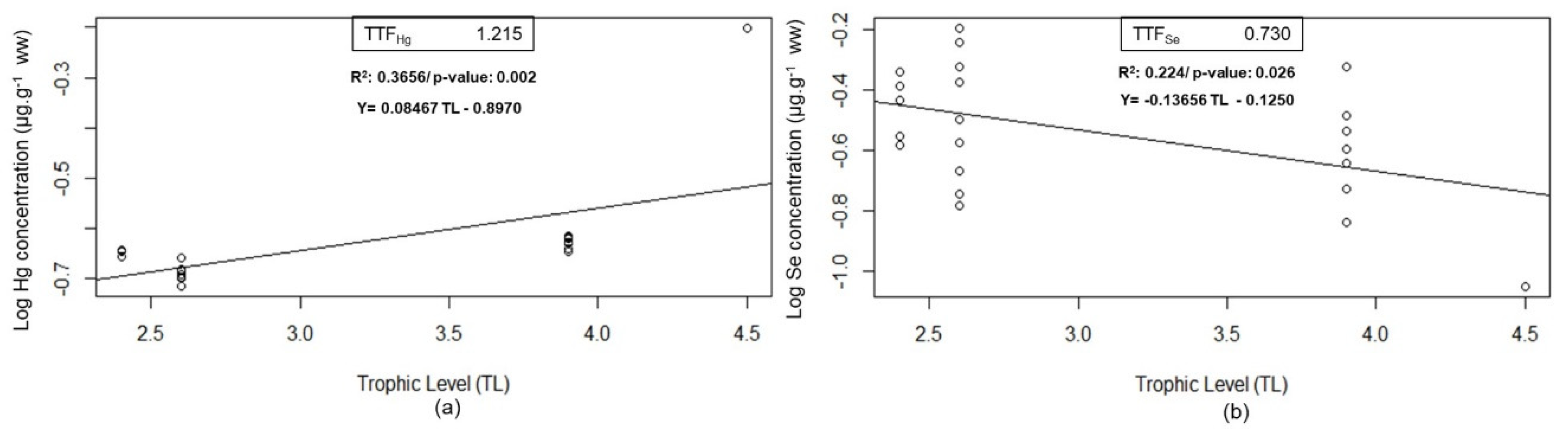

The trophic transfer factor estimated through models was significant, indicating that mercury (Hg) is biomagnified along the blue shark diet (

Figure 2a) while selenium (Se) is diluted (

Figure 2b) through the food chain.

3.2. Risk Assessment

The HQ estimated for each shark category were all below 1, indicating no risk of consumption (

Table 2). However, sensitive population sectors such as pregnant or breastfeeding women and children should always be mindful of the amount of this species consumption.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mercury and Selenium Trophic Transfer

Because of its widespread presence, toxicity, and ability to accumulate in organisms, Hg has been frequently used to study biomagnification in marine food webs [

29]. Sharks, with their reproductive strategy (K), high trophic level, and economic significance, are commonly used as models to study the biomagnification process of this contaminant [

37]. The dietary route plays a main role in determining toxic element burdens in marine organisms. Seafood is considered the major source of Hg intake in the human diet, but it also provides essential minerals like Se which serve as enzymatic cofactors and offer other health benefits [

38].

Bioaccumulation of Hg in the muscle of blue sharks captured in the southern part of the California Current Ecosystem, which occurs in the Mexican North Pacific has been confirmed and reported before, where adults showed a bigger concentration of Hg in muscle [

39]. Under this scene, we consider it relevant to investigate if biomagnification of this toxic metal was also taking place in this species. Food serves as a vehicle for both toxic and beneficial elements, so apex predators, including humans, are exposed to high levels of these elements, potentially leading to organic dysfunctions [

41]. While Se is essential within certain limits, excessive amounts can be harmful [

42]. Most research on this topic agrees that Hg and Se should be assessed together due to their antagonistic relationship [

43]. Selenium proteins are involved in mercury neutralization once they get into the body to prevent its toxicity, so when an organism has high levels of Hg, it is likely to have low levels of Se available [

44]. Therefore, it is crucial to monitor the concentration of both elements in marine products intended for human consumption.

Accordingly, our results show that biomagnification of Hg and Se biodilution occurs at the same time in this top predator. This phenomenon could be attributed to the Hg detoxification process where most of the Se available in the organism would be involved in the demethylation of MeHg to give place to inorganic Hg-Se compounds [

40]. Finally, this compound (Hg-Se) reacts with selenoproteins altering vital functions mainly involved in oxidative stress [

41]. It has been repeatedly suggested that Hg concentration increases along the food chain to explain the levels well above reference values in organisms living in the open sea [

42]. This is mainly because long-lived, slow-growing, and highly migratory oceanic fishes such as sharks tend to accumulate high concentrations of Hg, especially in the muscle, which can often exceed recommended limits for human consumption [

43].

However, other authors who aimed the same biomagnification hypothesis in the North-eastern Atlantic Ocean, found that BMF remained always <1 suggesting that biomagnification of Hg does not occur in this species [

44]. In contrast, in the Mexican Pacific previous studies reported that prey contains less Hg than predators but didn’t estimate the BMF, while also remarking that the main source of this toxic metal throughout the diet of the shark could be the pelagic red crab (

P. planipes), due to the large amount of it that the predator need to consume to compensate the lack of energy that this small prey can offer [

23]. So it is relevant to point out that Hg concentration found for this species after 15 years is almost 4 times higher. It is worth mentioning that this species is also commercial, caught, and used for preparing animal feed for aquaculture which finally will end up being consumed by humans.

4.2. Health risk Assessment

The shark fishery in the Mexican Pacific is a relevant food resource not only locally but globally since Mexico is one of the main producers and exporters of this shark species [

45,

46]. IMIPAS, through various monitoring programs (such as the shark observer programs) and specifically the tagging of blue sharks on board oceanographic cruises, has revealed that catches of this species for human consumption have been increasing due to the growing demand for its products due to its low cost [

47]. Nevertheless, the results of this program after 15 years show that the blue shark population in the Mexican Northwest Pacific stays stable and is not under overfishing pressure [

48]. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind the potential risks to human health that high levels of Hg accumulated in the edible parts of this shark can cause. One way to address this issue is the non-carcinogenic risk assessment method using the HQ established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency [

49]. This approach assumes that there is a level of exposure to the toxic metal (the reference dose, RD) below which even the most sensitive sectors of the population are unlikely to experience adverse health effects [

50].

Based on the results of our hazard quotient estimation, we could state that there is no risk for consumers of blue shark meat since all values were less than 1. However, taking into account that bioaccumulation and biomagnification of Hg occur in this species, it would be most prudent to recommend moderate consumption. In previous works with the same organisms sampled, we stipulated a daily consumption dose of this species that can be consumed without presenting risks of Hg poisoning, so under this calculation, an intake between 11.9 and 10.9 g per day can be recommended for an adult man or woman in Mexico [

39]. These results are similar to those proposed for the Mediterranean where the maximum consumption rate of blue shark is 10 g per day [

51]. In this sense, considering that shark meat is a great source of essential elements, but also the main Hg route of entry to humans, certain precautionary measures must be taken especially when the specimens consumed are adults and the consumers belong to the more sensitive population sector (pregnant and breastfeeding woman and child).

5. Conclusions

This study assessed the levels of mercury (Hg) and selenium (Se) in blue sharks in the CCLME region. While the sample size was limited, the data suggests a potential increase in Hg and a decrease in Se with higher trophic levels. Additionally, Hg and Se concentrations were found in prey species not previously studied in the area, which are also consumed by humans. The Hazard Quotient analysis recommends a weekly consumption limit of 70g of edible muscle of this shark species to avoid Hg poisoning risk for consumers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F Amezcua, JR Ruelas-Inzunza and ME Rechimont; methodology, F. Amezcua, JR Ruelas-Inzunza, F Amezcua-Linares, and ME Rechimont; software, F Amezcua, and ME Rechimont; formal analysis, ME Rechimont; investigation ME Rechimont and F Amezcua; resources, F Amezcua, JR Ruelas-Inzunza, JRF Vallarta-Zaratee and F Amezcua-Linares; data curation, F Amezcua and ME Rechimont; writing—original draft preparation, ME Rechimont; writing—review and editing, F Amezcua, JR Ruelas-Inzunza and F Amezcua-Linares; visualization, F Amezcua and ME Rechimont; supervision, F Amezcua and JR Ruelas-Inzunza; project administration, F Amezcua, F Amezcua-Linares and JR Ruelas-Inzunza; funding acquisition, F Amezcua, Roberto Vallarta and F Amezcua-Linares. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“The Mexican Institute on Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture funded the research surveys. The National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACYT) awarded the Ph.D. research grant 512466 to M.E. Rechimont. The National Autonomous University of México (UNAM) through the Institute of Marine Sciences and Limnology (ICMyL), funded the laboratory research and analysis and paid the processing charge fee for this article”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted under the Ethics Code of the Institute of Marine Sciences and Limnology, and all the samples were legally obtained with the appropriate fishing permits issued by the National Commission for Fisheries and Aquaculture”

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge technical support offered by Tecnológico Nacional de México through the project “Transferencia trófica de Hg y Se entre el tiburón azul Prionace glauca y sus principales presas en el Pacífico Mexicano”. We thank P. Spanopoulos and H. Bojorquez for their technical support in element readings. We also thank C. Suárez-Gutiérrez for editing the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMF |

Biomagnification Factor |

| TTF |

Trophic Transfer Factor |

| CCLME |

California Current Large Marine Ecosystem |

| TL |

Trophic Level |

| IMIPAS |

Mexican Institute for Research in Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture |

References

- Valladolid-Garnica, D.E.; Jara-Marini, M.E.; Torres-Rojas, Y.E.; Soto-Jiménez, M.F. Distribution, Bioaccumulation, and Trace Element Transfer among Trophic Levels in the Southeastern Gulf of California. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 194, 115290. [CrossRef]

- Pirrone, N.; Cinnirella, S.; Feng, X.; Finkelman, R.B.; Friedli, H.R.; Leaner, J.; Mason, R.; Mukherjee, A.B.; Stracher, G.B.; Streets, D. Global Mercury Emissions to the Atmosphere from Anthropogenic and Natural Sources. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2010, 10, 5951–5964.

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Mercury Stable Isotopes in the Ocean: Analytical Methods, Cycling, and Application as Tracers. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 874, 162485.

- Jeong, H.; Ali, W.; Zinck, P.; Souissi, S.; Lee, J.-S. Toxicity of Methylmercury in Aquatic Organisms and Interaction with Environmental Factors and Coexisting Pollutants: A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 173574.

- Bowman, K.L.; Lamborg, C.H.; Agather, A.M. A Global Perspective on Mercury Cycling in the Ocean. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 710, 136166.

- Rincón-Tomás, B.; Lanzén, A.; Sánchez, P.; Estupiñán, M.; Sanz-Sáez, I.; Bilbao, M.E.; Rojo, D.; Mendibil, I.; Pérez-Cruz, C.; Ferri, M. Revisiting the Mercury Cycle in Marine Sediments: A Potential Multifaceted Role for Desulfobacterota. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 465, 133120.

- Zhao, W.; Gan, R.; Xian, B.; Wu, T.; Wu, G.; Huang, S.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, S. Overview of Methylation and Demethylation Mechanisms and Influencing Factors of Mercury in Water. Toxics 2024, 12, 715.

- Sonke, J.E.; Angot, H.; Zhang, Y.; Poulain, A.; Björn, E.; Schartup, A. Global Change Effects on Biogeochemical Mercury Cycling. Ambio 2023, 52, 853–876.

- Pantoja-Echevarría, L.M.; Marmolejo-Rodríguez, A.J.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Arreola-Mendoza, L.; Tripp-Valdéz, A.; Verplancken, F.E.; Sujitha, S.B.; Jonathan, M.P. Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer of Cd in Commercially Sought Brown Smoothhound Mustelus Henlei in the Western Coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2020, 151, 110879. [CrossRef]

- Pałka, I.; Saniewska, D.; Bielecka, L.; Kobos, J.; Grzybowski, W. Uptake and Trophic Transfer of Selenium into Phytoplankton and Zooplankton of the Southern Baltic Sea. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 909, 168312.

- Mayland, H.F.; James, L.F.; Panter, K.E.; Sonderegger, J.L. 2 Selenium in Seleniferous Environments; 1989;

- Li, X.; Meng, Z.; Bao, L.; Su, H.; Wei, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Ji, N.; Zhang, R. Occurrence, Bioaccumulation, and Risk Evaluation of Selenium in Typical Chinese Aquatic Ecosystems. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 435, 140552.

- Adams, W.J.; Duguay, A. Selenium–Mercury Interactions and Relationship to Aquatic Toxicity: A Review. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 2024.

- Spiller, H.A. Rethinking Mercury: The Role of Selenium in the Pathophysiology of Mercury Toxicity. Clinical toxicology 2018, 56, 313–326.

- Kidd, K.; Clayden, M.; Jardine, T. Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification of Mercury through Food Webs. Environmental chemistry and toxicology of mercury. Wiley, Hoboken 2012, 455–499.

- Saidon, N.B.; Szabó, R.; Budai, P.; Lehel, J. Trophic Transfer and Biomagnification Potential of Environmental Contaminants (Heavy Metals) in Aquatic Ecosystems. Environmental pollution 2024, 340, 122815.

- Preti, A.; Soykan, C.U.; Dewar, H.; Wells, R.D.; Spear, N.; Kohin, S. Comparative Feeding Ecology of Shortfin Mako, Blue and Thresher Sharks in the California Current. Environmental Biology of Fishes 2012, 95, 127–146.

- Zafar, A.; Javed, S.; Akram, N.; Naqvi, S.A.R. Health Risks of Mercury. In Mercury Toxicity Mitigation: Sustainable Nexus Approach; Springer, 2024; pp. 67–92.

- Kohin, S.; Sippel, T.; Carvalho, F. Catch and Size of Blue Sharks Caught in US Fisheries in the North Pacific. ISC-16 SharkWG, Haeundai-gu, Busan, South Korea 2016.

- Godínez-Padilla, C.J.; Castillo-Géniz, J.L.; Hernández de la Torre, B.; González-Ania, L.V.; Román-Verdesoto, M.H. Marine-Climate Interactions with the Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca) Catches in the Western Coast of Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Fisheries Oceanography 2022, 31, 291–318. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.E.F.; Lessa, R.; Santana, F.M. Current Knowledge on Biology, Fishing and Conservation of the Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca). Neotropical Biology and Conservation 2021, 16, 71–88.

- Godínez-Padilla, C.J.; Castillo-Géniz, J.L.; Hernández de la Torre, B.; González-Ania, L.V.; Román-Verdesoto, M.H. Marine-climate Interactions with the Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca) Catches in the Western Coast of Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Fisheries Oceanography 2022, 31, 291–318.

- Escobar-Sánchez, O.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Rosíles-Martínez, R. Biomagnification of Mercury and Selenium in Blue Shark Prionace Glauca from the Pacific Ocean off Mexico. Biological Trace Element Research 2011, 144, 550–559.

- Hernández-Aguilar, S.B.; Escobar-Sánchez, O.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Abitia-Cárdenas, L.A. Trophic Ecology of the Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca) Based on Stable Isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) and Stomach Content. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2016, 96, 1403–1410. [CrossRef]

- Markaida, U.; Sosa-Nishizaki, O. Food and Feeding Habits of the Blue Shark Prionace Glauca Caught off Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico, with a Review on Its Feeding. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2010, 90, 977–994. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.; Lemos, V.A.; Silva, L.O.; Queiroz, A.F.; Souza, A.S.; da Silva, E.G.; dos Santos, W.N.; das Virgens, C.F. Analytical Strategies of Sample Preparation for the Determination of Mercury in Food Matrices—A Review. Microchemical Journal 2015, 121, 227–236.

- Gray, J.S. Biomagnification in Marine Systems: The Perspective of an Ecologist. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2002, 45, 46–52. [CrossRef]

- García-Seoane, R.; Antelo, J.; Fiol, S.; Fernández, J.A.; Aboal, J.R. Unravelling the Metal Uptake Process in Mosses: Comparison of Aquatic and Terrestrial Species as Air Pollution Biomonitors. Environmental Pollution 2023, 333, 122069. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, L.Q.; Letcher, R.; Bradford, S.A.; Feng, X.; Rinklebe, J. Biogeochemical Cycle of Mercury and Controlling Technologies: Publications in Critical Reviews in Environmental Science & Technology in the Period of 2017–2021. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 52, 4325–4330.

- Nfon, E.; Cousins, I.T.; Järvinen, O.; Mukherjee, A.B.; Verta, M.; Broman, D. Trophodynamics of Mercury and Other Trace Elements in a Pelagic Food Chain from the Baltic Sea. Science of the Total Environment 2009, 407, 6267–6274.

- Sakata, M.; Miwa, A.; Mitsunobu, S.; Senga, Y. Relationships between Trace Element Concentrations and the Stable Nitrogen Isotope Ratio in Biota from Suruga Bay, Japan. Journal of oceanography 2015, 71, 141–149.

- Guo, B.; Jiao, D.; Wang, J.; Lei, K.; Lin, C. Trophic Transfer of Toxic Elements in the Estuarine Invertebrate and Fish Food Web of Daliao River, Liaodong Bay, China. Marine pollution bulletin 2016, 113, 258–265.

- Amezcua, F.; Muro-Torres, V.; Soto-Jiménez, M.F. Stable Isotope Analysis versus TROPH: A Comparison of Methods for Estimating Fish Trophic Positions in a Subtropical Estuarine System. Aquatic Ecology 2015, 49, 235–250.

- Zhu, L.; Yan, B.; Wang, L.; Pan, X. Mercury Concentration in the Muscle of Seven Fish Species from Chagan Lake, Northeast China. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2012, 184, 1299–1310. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council; Global Affairs; Technology for Sustainability Program; Committee on Incorporating Sustainability in the US Environmental Protection Agency Sustainability and the US EPA; National Academies Press, 2011; ISBN 0-309-21252-9.

- CONAPESCA, 2020-2024 Programa Nacional de Pesca y Acuacultura.

- Sun, T.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Ji, C.; Shan, X.; Li, F. Evaluation on the Biomagnification or Biodilution of Trace Metals in Global Marine Food Webs by Meta-Analysis. Environmental Pollution 2020, 264, 113856. [CrossRef]

- Bushkin-Bedient, S.; Carpenter, D.O. Benefits versus Risks Associated with Consumption of Fish and Other Seafood. Reviews on environmental health 2010, 25, 161–192.

- Rechimont, M.; Ruelas-Inzunza, J.; Amezcua, F.; Paéz-Osuna, F.; Castillo-Géniz, J. Hg and Se in Muscle and Liver of Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca) from the Entrance of the Gulf of California: An Insight to the Potential Risk to Human Health. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2024, 1–13.

- Khan, M.A.; Wang, F. Mercury-selenium Compounds and Their Toxicological Significance: Toward a Molecular Understanding of the Mercury-selenium Antagonism. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry: An International Journal 2009, 28, 1567–1577.

- Mangiapane, E.; Pessione, A.; Pessione, E. Selenium and Selenoproteins: An Overview on Different Biological Systems. Current Protein and Peptide Science 2014, 15, 598–607.

- Baeyens, W.; Leermakers, M.; Papina, T.; Saprykin, A.; Brion, N.; Noyen, J.; De Gieter, M.; Elskens, M.; Goeyens, L. Bioconcentration and Biomagnification of Mercury and Methylmercury in North Sea and Scheldt Estuary Fish. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2003, 45, 498–508.

- Adams, D.H.; McMichael Jr, R.H. Mercury Levels in Four Species of Sharks from the Atlantic Coast of Florida. Fishery Bulletin 1999, 97, 372–379.

- Biton-Porsmoguer, S.; Bǎnaru, D.; Boudouresque, C.F.; Dekeyser, I.; Bouchoucha, M.; Marco-Miralles, F.; Lebreton, B.; Guillou, G.; Harmelin-Vivien, M. Mercury in Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca) and Shortfin Mako (Isurus Oxyrinchus) from North-Eastern Atlantic: Implication for Fishery Management. Marine pollution bulletin 2018, 127, 131–138.

- Sosa-Nishizaki, O.; Márquez-Farías, J.F.; Villavicencio-Garayzar, C.J. Case Study: Pelagic Shark Fisheries along the West Coast of Mexico. In Sharks of the Open Ocean; 2008; pp. 275–282 ISBN 978-1-4443-0251-6.

- Sosa-Nishizaki, O.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Larson, S.E.; Lowry, D. Chapter Four - Conclusions: Do We Eat Them or Watch Them, or Both? Challenges for Conservation of Sharks in Mexico and the NEP. In Advances in Marine Biology; Lowry, D., Larson, S.E., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 85, pp. 93–102 ISBN 0065-2881.

- IMIPAS.

- Fernández-Méndez, J.I.; Castillo-Géniz, J.L.; Ramírez-Soberón, G.; Haro-Ávalos, H.; González-Ania, L.V. Update on Standardized Catch Rates for Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca) in the 2006-2020 Mexican Pacific Longline Fishery Based upon a Shark Scientific Observer Program; ISC/21/SHARKWG-2/15, 2021;

- United States. Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Emergency; Remedial Response Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund: Pt. A. Human Health Evaluation Manual; Office of Emergency and Remedial Response, US Environmental Protection Agency, 1989; Vol. 1;.

- Marrugo-Negrete, J.; Verbel, J.O.; Ceballos, E.L.; Benitez, L.N. Total Mercury and Methylmercury Concentrations in Fish from the Mojana Region of Colombia. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2008, 30, 21–30.

- Storelli, A.; Barone, G.; Garofalo, R.; Busco, A.; Storelli, M.M.; Storelli, A.; Barone, G.; Garofalo, R.; Busco, A.; Storelli, M.M. Citation: Determination of Mercury, Methylmercury and Selenium Concentrations in Elasmobranch Meat: Fish Consumption Safety. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).