Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

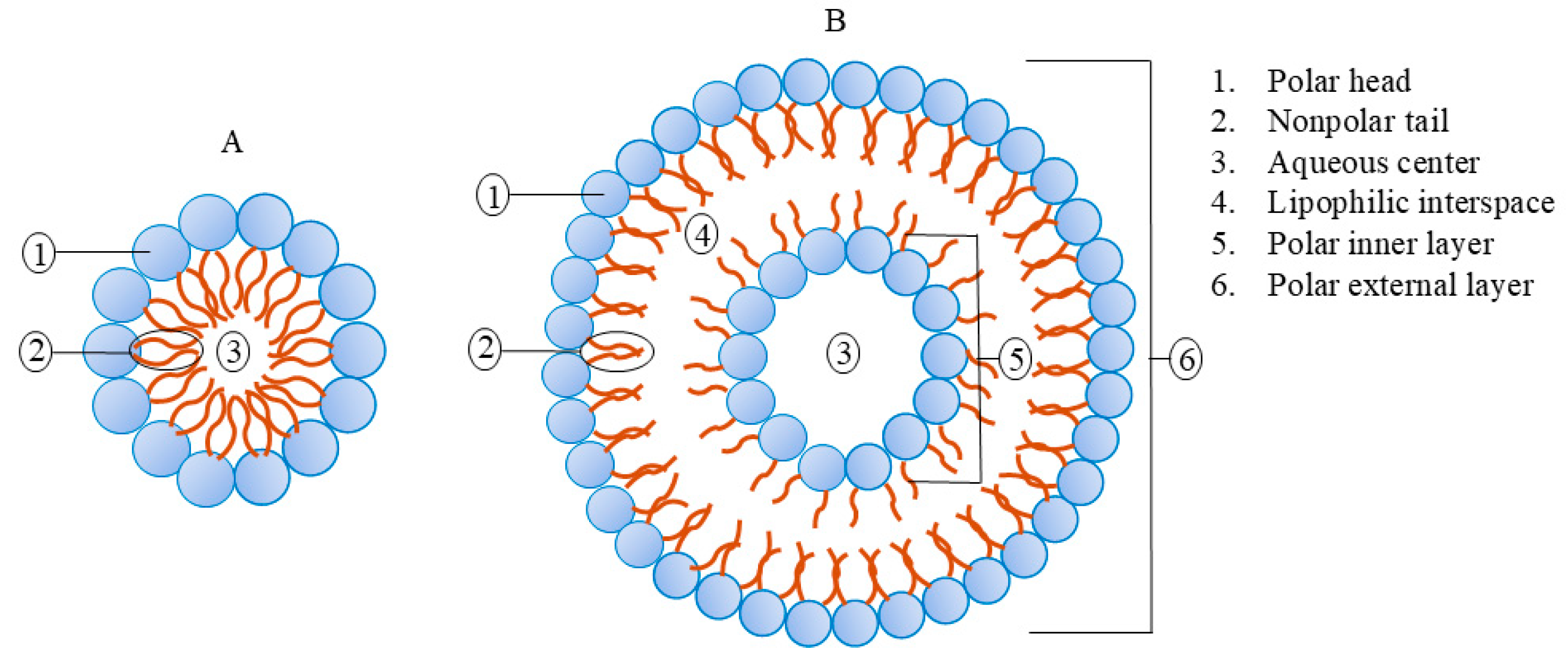

2. Nano-Liposomes

2.1. Structure and Properties of Nano-Liposomes

2.2. Biological Activity of the Encapsulated Compounds

2.3. Bioactive Compounds Encapsulated in Nano-Liposomes

2.4. Nano-Liposomes Enhanced Foods and Human Health

3. Conclusions

4. Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aman Mohamadi, M.; Farshi, P.; Ahmadi, P.; Ahmadi, A.; Yousefi, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Hosseini, S. M. Encapsulation of Vitamins Using Nanoliposome: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambati, R.; Phang, S.-M.; Ravi, S.; Aswathanarayana, R. Astaxanthin: Sources, Extraction, Stability, Biological Activities and Its Commercial Applications—A Review. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assil, K. K. Multivesicular Liposomes: Sustained Release of the Antimetabolite Cytarabine in the Eye. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1987, 105, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, L.; Mavragani, C. P.; Koutsilieris, M. The Immunomodulatory Properties of Vitamin D. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2022, 33, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Liu, Z.; Xie, C.; Marawan, M. A.; Ares, I.; Lopez-Torres, B.; Martínez, M.; Maximiliano, J.-E.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.-R.; Wang, X.; Anadón, A.; Martínez, M.-A. Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) as a Functional Food: Is It Beneficial or Not? Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, E. J.; Garcia, C. V.; Shin, G. H.; Kim, J. T. Improvement of Thermal and UV-Light Stability of β-Carotene-Loaded Nanoemulsions by Water-Soluble Chitosan Coating. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, K.; Patra, J. K. Novel Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Citrullus Lanatus Rind and Investigation of Proteasome Inhibitory Activity, Antibacterial, and Antioxidant Potential. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2015, 7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, S. S.; Raje Harshal, A. Preparation, Optimization, Characterization, and Stability Studies of Salicylic Acid Liposomes. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2003, 29, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, P. Q. M.; Matos, M. F. R. D.; Ramos, I. G.; Magalhães-Guedes, K. T.; Druzian, J. I.; Costa, J. A. V.; Nunes, I. L. Innovative Functional Nanodispersion: Combination of Carotenoid from Spirulina and Yellow Passion Fruit Albedo. Food Chem. 2019, 285, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, C. S.; Bonwick, G. A. Ensuring the Future of Functional Foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1467–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolla, P. K.; Gote, V.; Singh, M.; Patel, M.; Clark, B. A.; Renukuntla, J. Lutein-Loaded, Biotin-Decorated Polymeric Nanoparticles Enhance Lutein Uptake in Retinal Cells. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, C. M.; Tavares, M. N.; Macedo, L. P.; Araújo, G. S.; Furlong, E. B.; Dora, C. L.; Burkert, J. F. M. Physical and Chemical Stability of β-Carotene Nanoemulsions during Storage and Thermal Process. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boura, E.; Nencka, R. Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinases: Function, Structure, and Inhibition. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 337, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzuto, G.; Molinari, A. Liposomes as Nanomedical Devices. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2015, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, L. Polyphenols: Chemistry, Dietary Sources, Metabolism, and Nutritional Significance. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 56, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, E.; Onguka, O.; Claypool, S. M. Phosphatidylethanolamine Metabolism in Health and Disease. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology 2016, 321, 29–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carugo, D.; Bottaro, E.; Owen, J.; Stride, E.; Nastruzzi, C. Liposome Production by Microfluidics: Potential and Limiting Factors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, P.; Famili, A.; Nagapudi, K.; Al-Sayah, M. A. Using Supercritical Fluid Technology as a Green Alternative During the Preparation of Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M. A.; Oseliero Filho, P. L.; Jange, C. G.; Sinigaglia-Coimbra, R.; Oliveira, C. L. P.; Pinho, S. C. Structural Characterization of Multilamellar Liposomes Coencapsulating Curcumin and Vitamin D3. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 549, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-H.; Huang, R.-F. S.; Wei, Y.-J.; Stephen Inbaraj, B. Inhibition of Colon Cancer Cell Growth by Nanoemulsion Carrying Gold Nanoparticles And Lycopene. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2015, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, M. C.; Cosco, D.; Celia, C.; Tudose, A.; Mare, R.; Paolino, D.; Fresta, M. Anticancer Activity of All- Trans Retinoic Acid-Loaded Liposomes on Human Thyroid Carcinoma Cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 150, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, R.; Alvarez, V.; Temelli, F. Encapsulation of Vitamin B2 in Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Using Supercritical CO 2. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2017, 120, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, F.; Ceglie, S.; Miguel, M.; Lindman, B.; Lopez, F. Oral Delivery of All-Trans Retinoic Acid Mediated by Liposome Carriers. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 201, 111655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, P. P.; Andrade, L. D. A.; Flôres, S. H.; Rios, A. D. O. Nanoencapsulation of Carotenoids: A Focus on Different Delivery Systems and Evaluation Parameters. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3851–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, P. P.; Paese, K.; Guterres, S. S.; Pohlmann, A. R.; Costa, T. H.; Jablonski, A.; Flôres, S. H.; Rios, A. D. O. Development of Lycopene-Loaded Lipid-Core Nanocapsules: Physicochemical Characterization and Stability Study. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2015, 17, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Dutta, D. Designing a Nanoliposome Loaded with Provitamin A Xanthophyll β-Cryptoxanthin from K. Marina DAGII to Target a Population Suffering from Hypovitaminosis A. Process Biochem. 2024, 138, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Feng, T.; Wang, X.; Xia, S.; John Swing, C. Liposomes for Encapsulation of Liposoluble Vitamins (A, D, E and K): Comparation of Loading Ability, Storage Stability and Bilayer Dynamics. Food Res. Int. 2023, 163, 112264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focsan, A. L.; Polyakov, N. E.; Kispert, L. D. Supramolecular Carotenoid Complexes of Enhanced Solubility and Stability—The Way of Bioavailability Improvement. Molecules 2019, 24, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, B. J.; Sliwka, H.-R.; Partali, V.; Cardounel, A. J.; Zweier, J. L.; Lockwood, S. F. Direct Superoxide Anion Scavenging by a Highly Water-Dispersible Carotenoid Phospholipid Evaluated by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 2807–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Morales, J.; López Elías, J. A.; Medina Félix, D.; García Lagunas, N.; Fimbres Olivarría, D. Efecto del estrés por nitrógeno y salinidad en el contenido de b-caroteno de la microalga Dunaliella tertiolecta//Effect of nitrogen and salinity stress on the β-carotene content of the microalgae Dunaliella tertiolecta. Biotecnia 2020, 22, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasa-Falcon, A.; Arranz, E.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Giblin, L. Delivery of β-Carotene to the in Vitro Intestinal Barrier Using Nanoemulsions with Lecithin or Sodium Caseinate as Emulsifiers. LWT 2021, 135, 110059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaucheron, F. Iron Fortification in Dairy Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibzahedi, S. M. T.; Jafari, S. M. The Importance of Minerals in Human Nutrition: Bioavailability, Food Fortification, Processing Effects and Nanoencapsulation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, D.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Nogueira, E. Design of Liposomes as Drug Delivery System for Therapeutic Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi Ghahestani, Z.; Alebooye Langroodi, F.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Ramezani, M.; Hashemi, M. Evaluation of Anti-Cancer Activity of PLGA Nanoparticles Containing Crocetin. Artif. Cells Nanomedicine Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huo, P.; Ding, Z.; Kumar, P.; Liu, B. Preparation of Lutein-Loaded PVA/Sodium Alginate Nanofibers and Investigation of Its Release Behavior. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, C.; Sunthar, P. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Preparation Techniques of Liposomes. J. Liposome Res. 2020, 30, 336–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassane Hamadou, A.; Huang, W.-C.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. Comparison of β-Carotene Loaded Marine and Egg Phospholipids Nanoliposomes. J. Food Eng. 2020, 283, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sharma, G.; Thakur, K.; Raza, K.; Shivhare, U. S.; Ghoshal, G.; Katare, O. P. Beta-Carotene-Encapsulated Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (BC-SLNs) as Promising Vehicle for Cancer: An Investigative Assessment. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, B. ENCAPSULATION OF VITAMIN D3 AND VITAMIN K2 IN CHITOSAN COATED LIPOSOMES.

- Jiao, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Chang, Y.; Song, J.; Xiao, Y. Polypeptide – Decorated Nanoliposomes as Novel Delivery Systems for Lutein. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 31372–31381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Wang, X.; Yin, Y.; Xia, J. Preparation and Evaluation of Vitamin C and Folic Acid-Coloaded Antioxidant Liposomes. Part. Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaga, K.; Honda, M.; Adachi, T.; Honjo, M.; Wahyudiono, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Kanda, H.; Goto, M. Nanoparticle Formation of PVP/Astaxanthin Inclusion Complex by Solution-Enhanced Dispersion by Supercritical Fluids (SEDS): Effect of PVP and Astaxanthin Z-Isomer Content. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 136, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, K.; Wu, M. K.; Scapa, E. F.; Roderick, S. L.; Cohen, D. E. Structure and Function of Phosphatidylcholine Transfer Protein (PC-TP)/StarD2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2007, 1771, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, L. M.; Yoon, B. K.; Jackman, J. A.; Knoll, W.; Weiss, P. S.; Cho, N.-J. Understanding How Sterols Regulate Membrane Remodeling in Supported Lipid Bilayers. Langmuir 2017, 33, 14756–14765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, J. G.; Fairn, G. D. Distribution, Dynamics and Functional Roles of Phosphatidylserine within the Cell. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

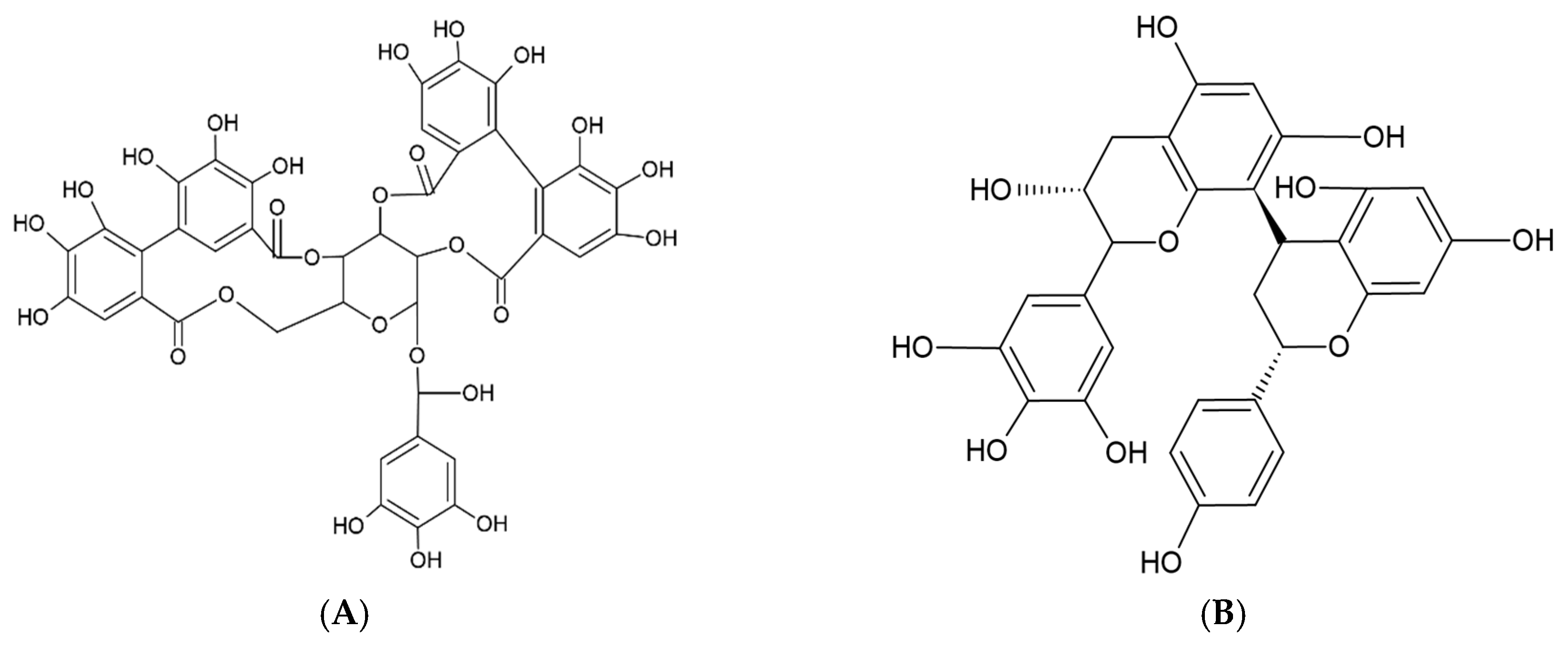

- Koleckar, V.; Kubikova, K.; Rehakova, Z.; Kuca, K.; Jun, D.; Jahodar, L.; Opletal, L. Condensed and Hydrolysable Tannins as Antioxidants Influencing the Health. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, L.; Xiao, N.; Li, M.; Xie, X. Physical Properties of Oil-in-Water Nanoemulsions Stabilized by OSA-Modified Starch for the Encapsulation of Lycopene. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 552, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yalcin, M.; Lin, Q.; Ardawi, M.-S. M.; Mousa, S. A. Self-Assembly of Green Tea Catechin Derivatives in Nanoparticles for Oral Lycopene Delivery. J. Controlled Release 2017, 248, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Shen, J.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. P-Coumaric Acid-Loaded Nanoliposomes: Optimization, Characterization, Antimicrobial Properties and Preservation Effects on Fresh Pod Pepper Fruit. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, X.; Wei, Y.; Fei, T.; Hu, X.; Wang, L. Enhancing the Stability and Bio-Accessibility of Carotenoids Extracted from Canistel (Lucuma Nervosa) via Liposomes Encapsulation. LWT 2024, 204, 116455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shibata, T.; Hisaka, S.; Osawa, T. Astaxanthin Inhibits Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Cellular Toxicity in Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y Cells via Mitochondria-Targeted Protective Mechanism. Brain Res. 2009, 1254, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-Guevara, Ma. L.; Luna-Guevara, J. J.; Hernández-Carranza, P.; Ruíz-Espinosa, H.; Ochoa-Velasco, C. E. Phenolic Compounds: A Good Choice Against Chronic Degenerative Diseases. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry 2018, 59, 79–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A. R.; Pinheiro, A. C.; Vicente, A. A.; Souza-Soares, L. A.; Cerqueira, M. A. Liposomes Loaded with Phenolic Extracts of Spirulina LEB-18: Physicochemical Characterization and Behavior under Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur, M. C. P. P. R.; Campos, C.; Vermelho, A. B.; Nobrega, J.; Da Cunha Boldrini, L.; Balottin, L.; Lage, C.; Rosado, A. S.; Ricci-Júnior, E.; Dos Santos, E. P. Photoprotective Nanoemulsions Containing Microbial Carotenoids and Buriti Oil: Efficacy and Safety Study. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 6741–6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrad, B.; Ravanfar, R.; Licker, J.; Regenstein, J. M.; Abbaspourrad, A. Enhancing the Physicochemical Stability of β-Carotene Solid Lipid Nanoparticle (SLNP) Using Whey Protein Isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazemiyeh, E.; Eskandani, M.; Sheikhloie, H.; Nazemiyeh, H. Formulation and Physicochemical Characterization of Lycopene-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 6, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubigh, A.; Aydi, A.; Abderrabba, M. Experimental Measurement and Correlation of Solubility Data and Thermodynamic Properties of Protocatechuic Acid in Four Organic Solvents. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2015, 60, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsairat, H.; Khater, D.; Sayed, U.; Odeh, F.; Al Bawab, A.; Alshaer, W. Liposomes: Structure, Composition, Types, and Clinical Applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonogi, S.; Riangjanapatee, P. Physicochemical Characterization of Lycopene-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Formulations for Topical Administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 478, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Galindo, A. S.; Díaz-Peralta, L.; Galván-Hernández, A.; Ortega-Blake, I.; Pérez-Riascos, A.; Rojas-Aguirre, Y. Los liposomas en nanomedicina: del concepto a sus aplicaciones clínicas y tendencias actuales en investigación. Mundo Nano Rev. Interdiscip. En Nanociencias Nanotecnología 2023, 16, 1e–26e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Montiel, H.; Herrera-Cruz, E.; Hoya-Florez, J.; Prieto-Guevara, M.; Estrada-Posada, A.; Yepes Blandón, J. A. Crecimiento y Viabilidad Celular de Microalgas: Efecto Del Medio de Cultivo. Intropica 2020, 15, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Wang, H.; Gu, K. Nanoliposomes as Vehicles for Astaxanthin: Characterization, In Vitro Release Evaluation and Structure. Molecules 2018, 23, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.; Zhang, S.; Gu, K.; Zhang, N. Preparation of Astaxanthin-Loaded Liposomes: Characterization, Storage Stability and Antioxidant Activity. CyTA - J. Food 2018, 16, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păvăloiu, R.-D.; Sha’at, F.; Neagu, G.; Deaconu, M.; Bubueanu, C.; Albulescu, A.; Sha’at, M.; Hlevca, C. Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Lycium Barbarum Leaves into Liposomes as a Strategy to Improve Their Delivery. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. G.; Otero, P.; Echave, J.; Carreira-Casais, A.; Chamorro, F.; Collazo, N.; Jaboui, A.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M. A. Xanthophylls from the Sea: Algae as Source of Bioactive Carotenoids. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. C.; Hill, L. E.; Zambiazi, R. C.; Mertens-Talcott, S.; Talcott, S.; Gomes, C. L. Nanoencapsulation of Hydrophobic Phytochemicals Using Poly (Dl-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) (PLGA) for Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Delivery Applications: Guabiroba Fruit (Campomanesia Xanthocarpa O. Berg) Study. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshky, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Hamishehkar, H.; Moghadam, M.; Babazadeh, A. Vitamin A Palmitate-Bearing Nanoliposomes: Preparation and Characterization. Food Biosci. 2016, 13, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raben, D. M.; Barber, C. N. Phosphatidic Acid and Neurotransmission. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2017, 63, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidinejad, A.; Jafari, S. M. Nanoencapsulation of Bioactive Food Ingredients. In Handbook of Food Nanotechnology; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 279–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Imran, M.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Iahtisham-Ul-Haq, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Patel, S.; Pan, X.; Naz, S.; Sanches Silva, A.; Saeed, F.; Rasul Suleria, H.A. Proanthocyanidins: A Comprehensive Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 108999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, H.; Baskaran, V. Biodegradable Chitosan-Glycolipid Hybrid Nanogels: A Novel Approach to Encapsulate Fucoxanthin for Improved Stability and Bioavailability. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Tong, Q.; Jafari, S. M.; Assadpour, E.; Shehzad, Q.; Aadil, R. M.; Iqbal, M. W.; Rashed, M. M. A.; Mushtaq, B. S.; Ashraf, W. Carotenoid-Loaded Nanocarriers: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 275, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis Giada, M. D. L. Food Phenolic Compounds: Main Classes, Sources and Their Antioxidant Power. In Oxidative Stress and Chronic Degenerative Diseases - A Role for Antioxidants; Morales-Gonzalez, J. A., Ed.; InTech, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Roll Zimmer, T. B.; Barboza Mendonça, C. R.; Zambiazi, R. C. Methods of Protection and Application of Carotenoids in Foods - A Bibliographic Review. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamabadi, H.; Falsafi, S. R.; Jafari, S. M. Nanoencapsulation of Carotenoids within Lipid-Based Nanocarriers. J. Controlled Release 2019, 298, 38–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamabadi, H.; Sadeghi Mahoonak, A.; Allafchian, A.; Ghorbani, M. Fabrication of β-Carotene Loaded Glucuronoxylan-Based Nanostructures through Electrohydrodynamic Processing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, U. K.; Nielsen, B. V.; Milledge, J. J. Tuning Dunaliella Tertiolecta for Enhanced Antioxidant Production by Modification of Culture Conditions. Mar. Biotechnol. 2021, 23, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjoerring-Thyssen, J.; Olsen, K.; Koehler, K.; Jouenne, E.; Rousseau, D.; Andersen, M. L. Morphology and Structure of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Loaded with High Concentrations of β-Carotene. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 12273–12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, A.; Durán, N. Nanotoxicology of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Metals 2015, 5, 934–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengul, A. B.; Asmatulu, E. Toxicity of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1659–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabestarian, H.; Homayouni-Tabrizi, M.; Soltani, M.; Namvar, F.; Azizi, S.; Mohamad, R.; Shabestarian, H. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Sumac Aqueous Extract and Their Antioxidant Activity. Mater. Res. 2016, 20, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Dhawan, V.; Holm, R.; Nagarsenker, M. S.; Perrie, Y. Liposomes: Advancements and Innovation in the Manufacturing Process. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 154–155, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Ali, A. A. E.; Trivedi, L. R. An Updated Review On:Liposomes as Drug Delivery System. Pharmatutor 2018, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Neupane, Y. R.; Panda, B. P.; Kohli, K. Lipid Based Nanoformulation of Lycopene Improves Oral Delivery: Formulation Optimization, Ex Vivo Assessment and Its Efficacy against Breast Cancer. J. Microencapsul. 2017, 34, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.; Shukla, S.; Kumar, P.; Wahla, V.; Bajpai, V. K.; Rather, I. A. Application of Nanotechnology in Food Science: Perception and Overview. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotomayor-Gerding, D.; Oomah, B. D.; Acevedo, F.; Morales, E.; Bustamante, M.; Shene, C.; Rubilar, M. High Carotenoid Bioaccessibility through Linseed Oil Nanoemulsions with Enhanced Physical and Oxidative Stability. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soukoulis, C.; Bohn, T. A Comprehensive Overview on the Micro- and Nano-Technological Encapsulation Advances for Enhancing the Chemical Stability and Bioavailability of Carotenoids. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Cameron, R. G.; Manthey, J. A.; Hunter, W. B.; Bai, J. Microencapsulation of Tangeretin in a Citrus Pectin Mixture Matrix. Foods 2020, 9, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Feng, B.; Zhang, X.; Xia, W.; Xia, S. Biopolymer-Coated Liposomes by Electrostatic Adsorption of Chitosan (Chitosomes) as Novel Delivery Systems for Carotenoids. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Uemori, C.; Kon, T.; Honda, M.; Wahyudiono, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Machmudah, S.; Kanda, H.; Goto, M. Preparation of Liposomes Encapsulating β–Carotene Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide with Ultrasonication. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2020, 161, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatipamula, V. B.; Kukavica, B. Phenolic Compounds as Antidiabetic, Anti-inflammatory, and Anticancer Agents and Improvement of Their Bioavailability by Liposomes. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 926–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado, D. F.; Palazzo, I.; Scognamiglio, M.; Calvo, L.; Della Porta, G.; Reverchon, E. Astaxanthin Encapsulation in Ethyl Cellulose Carriers by Continuous Supercritical Emulsions Extraction: A Study on Particle Size, Encapsulation Efficiency, Release Profile and Antioxidant Activity. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 150, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, J. E. MAM (Mitochondria-Associated Membranes) in Mammalian Cells: Lipids and Beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2014, 1841, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, A. G.; Valim, M. O.; Amorim, A. G. N.; Do Amaral, C. P.; De Almeida, M. P.; Borges, T. K. S.; Socodato, R.; Portugal, C. C.; Brand, G. D.; Mattos, J. S. C.; Relvas, J.; Plácido, A.; Eaton, P.; Ramos, D. A. R.; Kückelhaus, S. A. S.; Leite, J. R. S. A. Cytotoxic Activity of Poly-ɛ-Caprolactone Lipid-Core Nanocapsules Loaded with Lycopene-Rich Extract from Red Guava (Psidium Guajava L.) on Breast Cancer Cells. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Secundo, F.; Mao, X. Preparation and Characterization of Phosphatidyl-Agar Oligosaccharide Liposomes for Astaxanthin Encapsulation. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Khan, M. Z.; Ma, Y.; Alugongo, G. M.; Ma, J.; Chen, T.; Khan, A.; Cao, Z. The Antioxidant Properties of Selenium and Vitamin E; Their Role in Periparturient Dairy Cattle Health Regulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Lam, T. I.; Yokoyama, W.; Cheng, L. W.; Zhong, F. Beta-Carotene Encapsulated in Food Protein Nanoparticles Reduces Peroxyl Radical Oxidation in Caco-2 Cells. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Park, J.-Y.; Kwon, C. W.; Hong, S.-C.; Park, K.-M.; Chang, P.-S. An Overview of Nanotechnology in Food Science: Preparative Methods, Practical Applications, and Safety. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, A.; Alipoor Amro Abadi, M.; Khorasani, S.; Mohammadabadi, M.-R.; Jamshidi, A.; Torkaman, S.; Taghavi, E.; Mozafari, M. R.; Rasti, B. Nanoliposomes and Tocosomes as Multifunctional Nanocarriers for the Encapsulation of Nutraceutical and Dietary Molecules. Molecules 2020, 25, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pu, C.; Tang, W.; Wang, S.; Sun, Q. Gallic Acid Liposomes Decorated with Lactoferrin: Characterization, in Vitro Digestion and Antibacterial Activity. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Wei, L.; Yin, B.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Encapsulation of Lycopene within Oil-in-Water Nanoemulsions Using Lactoferrin: Impact of Carrier Oils on Physicochemical Stability and Bioaccessibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Temelli, F.; Curtis, J. M.; Chen, L. Encapsulation of Lutein in Liposomes Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Yan, X.; Sun, L.; Yang, T.; Hu, X.; He, Z.; Liu, F.; Liu, X. Research Progress on Extraction, Biological Activities and Delivery Systems of Natural Astaxanthin. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

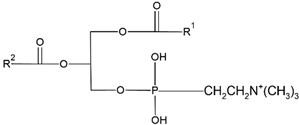

| Natural | Synthetic | Chemical Structure | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

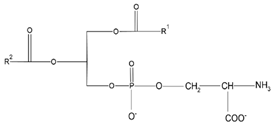

| Phosphatidy- lcholine (PC) |

Dimyristoylphos- phatidylcholine (DMPC) |

|

Increase membranes fluidity and eicosanoid production | [44] |

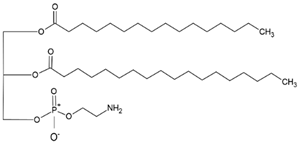

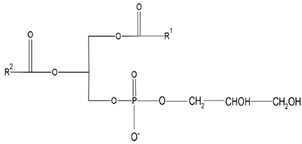

| Phosphatidy- lethanolamine (PE) |

Dioleoylphos- phatidylcholine (DOPC) |

|

PC precursor, promotes membrane fusion, oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial biogenesis | [16] |

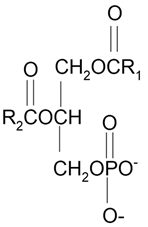

| Phosphatidy- lserine (PS) |

Distearoylphos- phatidylcholine (DSPC) |

|

PE decarboxylation, autophagosomes formation, morphology regulation and dynamics and functions of mitochondria | [94] |

| Phosphatidyl-glycerol (PG) | Dipalmitolphos- phatidylglycerol (DPPG) |

|

Important role in apoptosis and blood clotting, besides serving as a conduit for the transfer of lipids between organelles | [46] |

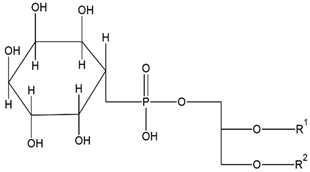

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Distearoylphos- phatidylglycerol (DSPG) |

|

Regulates traffic to and from Golgi apparatus and helps protect against hepatic viruses | [13] |

| Phosphatidic acid (PA) |  |

Serve as a fusogenic lipid, altering membrane structure and promoting membrane fusion, especially in neurons | [69] |

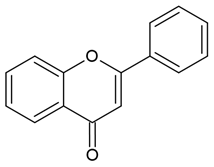

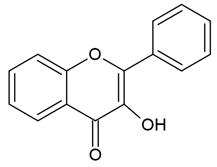

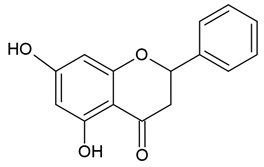

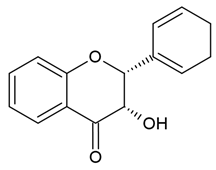

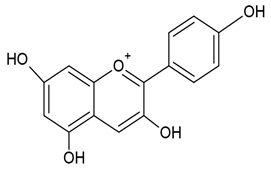

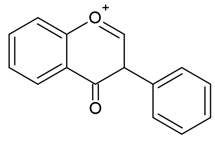

| Flavonoid | Structure |

|---|---|

| Flavones |  |

| Flavonols |  |

| Flavanones |  |

| Flavanols |  |

| Anthocyanidins |  |

| Isoflavones |  |

| Retinoids | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chemical structure | Type of nano-liposome | Reference |

| Retinol |  |

Lecithin-cholesterol structure, small unilamellar (20-200 nm), retinol contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,68] |

| Retinoic acid |  |

Lecithin-cholesterol structure, small unilamellar (20-200 nm), retinoic acid contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,68] |

| Retinyl ester |  |

Lecithin-cholesterol structure, small unilamellar (20-200 nm), retinyl ester contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,68] |

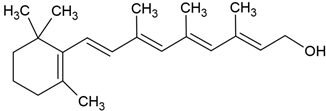

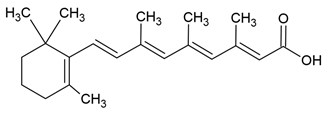

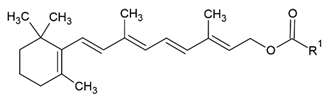

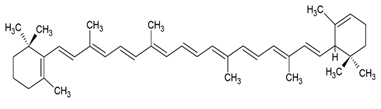

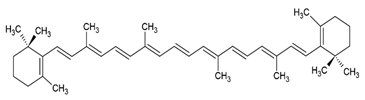

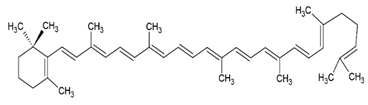

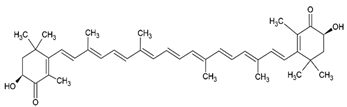

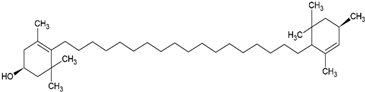

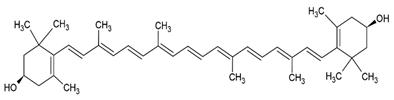

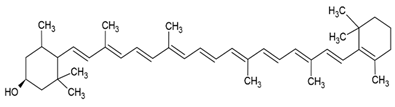

| Carotenoids | |||

| Name | Chemical structure | Type of nano-liposome | Reference |

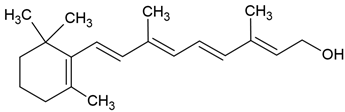

| α-carotene |  |

Lecithin, cholesterol and polysorbate 80 structure, giant unilamellar size (> 1 µm), α -carotene contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,51] |

| β-carotene |  |

Lecithin, cholesterol and polysorbate 80 structure, giant unilamellar size (> 1 µm), β-carotene contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,51] |

| γ-carotene |  |

Soy, egg or marine lecithin and cholesterol structure, giant unilamellar size (> 1 µm), γ -carotene contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,75] |

| Astaxanthin |  |

Agarose oligosaccharides, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidyl galactose and/or phosphatidyl neoagarobiose structure, small unilamellar (20-200 nm), astaxanthin contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [28,96] |

| Lutein |  |

Supercritical carbon-dioxide method, small unilamellar size (20-200 nm), lutein contained in the aqueous center | [103] |

| Zeaxanthin |  |

Lecithin, cholesterol and polysorbate 80 structure, giant unilamellar size (> 1 µm), zeaxanthin contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [28,50] |

| β-criptoxanthin |  |

Cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine structure, small unilamellar (20-200 nm), β-cryptoxanthin contained in the aqueous center | [26] |

| Phenols | |||

| Name | Chemical structure | Type of nano-liposome | Reference |

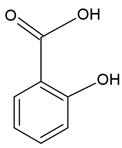

| Gallic acid |  |

Soy lecithin and cholesterol structure, small unilamellar size (20-200 nm), gallic acid contained in the aqueous center | [101] |

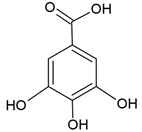

| Protocatechuic acid |  |

Egg yolk phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol structure, small unilamellar size (20-200 nm), protocatechuic acid contained in the aqueous center | [58,65] |

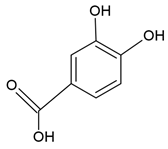

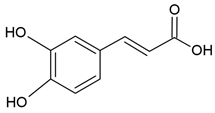

| Caffeic acid |  |

Egg yolk phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol structure, small unilamellar size (20-200 nm), protocatechuic acid contained in the aqueous center | [58,65] |

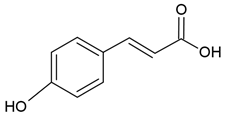

| p-cumaric acid |  |

Soy lecithin and cholesterol structure, small unilamellar size (20-200 nm), p-coumaric acid contained in the aqueous center | [50] |

| Salicylic acid |  |

Soy lecithin and cholesterol structure, small unilamellar size (20-200 nm), p-coumaric acid contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [8] |

| Vitamins | |||

| Name | Chemical structure | Type of nano-liposome | Reference |

| Vitamin A |  |

Lecithin and cholesterol structure, small unilamellar size (20-200 nm), vitamin A contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,68] |

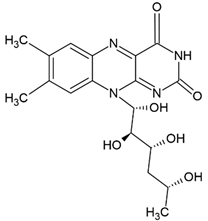

| Vitamin B2 |  |

Vegetable oil (chia, sunflower and virgin olive) structure, giant unilamellar size (> 1µm), vitamin B2 contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,22] |

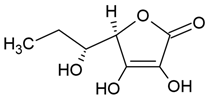

| Vitamin C |  |

Phosphatidylcholine, stearic acid and stearic calcium structure, giant unilamellar (> 1µm), vitamin C contained in the aqueous center | [1,37] |

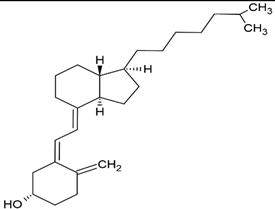

| Vitamin D3 |  |

Soy phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol structure, giant unilamellar size (> 1µm), vitamin D3 contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,19] |

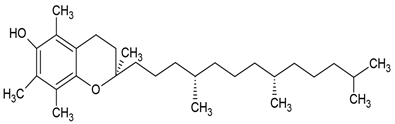

| Vitamin E |  |

Phosphatidylcholine, stearic acid and stearic calcium structure, giant unilamellar (> 1µm), vitamin E contained in the aqueous center | [1,37] |

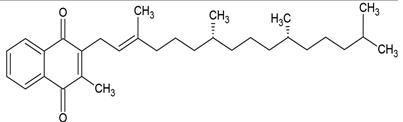

| Vitamin K |  |

Phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol structure, giant unilamellar size (> 1µm), vitamin K contained in the lipid intermembrane section | [1,40] |

| Nanosystem | Carotenoids | Particle Size (nm) | EE (%) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Storage Stability (Days) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoemulsions | β-carotene | 218 | NA | 40 | 21 at 37 °C | [6] |

| 143.7 | −38.2 | 30 at 25 °C | ||||

| Microbial carotenoids | 142.1 | NA | 30 at 25 °C | [55] | ||

| Carotenoids | 290 to 350 | −53.4 to −58.8 | 21 at 25 °C | [31] | ||

| β-carotene | 198.4 to 315.6 | −29.9 to −38.5 | 90 at 4, 25, and 37 °C | [12] | ||

| Carotenoids | <200 | −30 to −45 | 35 at 25 °C | [87] | ||

| Lycopene | 145.1 to 161.9 | −19.7 to −20.7 | 1 at 25 °C | [48] | ||

| 200.1 to 287.1 | 61 to 89.1 | 20 to 45 | 42 at 4, 25, and 37 °C | [102] | ||

| Polymeric/biopolymeric NPs | Carotenoids | 153 | 83.7 | NA | NA | [67] |

| 84.4 | >96 | −41.3 to −43.6 | 60 at 41 °C | [9] | ||

| β-carotene | 77.8 to 371.8 | 98.7 to 99.1 | −37.8 to −29.9 | NA | [98] | |

| β-carotene | 70.4 | 97.4 | NA | NA | [76] | |

| Lycopene | 152 | 89 | 58.3 | NA | [49] | |

| ~ 200 | >95 | −36 | 210 at 5 °C | [95] | ||

| 193 | NA | −11.5 | 14 at 25 °C | [25] | ||

| Lutein | <250 | 74.5 | −27.2 | NA | [11] | |

| Lutein | 240 to 340 | ~91.9 | NA | NA | [36] | |

| Crocetin | 288 to 584 | 59.6 to 97.2 | NA | NA | [35] | |

| Fucoxanthin | 200 to 500 | 47 to 90 | 30 to 50 | 6 at 37 °C | [72] | |

| Nanoliposomes/liposomes | Carotenoids | 70 to100 | 75 | −5.3 | NA | [90] |

| β-carotene | 162.8 to 365.8 | ~98 | 64.5 to 42.6 | 70 at 4 °C | [38] | |

| Astaxanthin | 80.6 | 97.6 | 31.8 | 15 at 4 and 25 °C | [63] | |

| 60 to 80 | 97.4 | NA | NA | [64] | ||

| Lutein | 264.8 to 367.1 | 91.8 to 92.9 | −34.3 to −27.9 | NA | [41] | |

| SLNPs and NLCs | β-carotene SLNPs | 200 to 400 | 53.4 to 68.3 | −6.1 to −9.3 | 90 at 5, 25, and 40 °C | [39] |

| <220 | NA | 20 to 30 | 10 at 25 °C | [56] | ||

| 120 | NA | −30 | 56 at 25 °C | |||

| Lycopene SLNPs | 125 to 166 | 86.6 to 98.4 | NA | 60 at 4 °C | [57] | |

| Lycopene NLCs | 157 to 166 | > 99 | −74.2 to −74.6 | 120 at 4, 30, and 40 °C | [60] | |

| 121.9 | 84.50 | −29 | 90 at 25 °C | [85] | ||

| Supercritical fluid-based NPs | Astaxanthin | 150 to 175 | NA | NA | NA | [43] |

| 266 | 84 | NA | NA | [93] | ||

| Metal/metal oxide-based NPs and hybrid nanocomposites | Carotenoids | 20 to 140 | NA | NA | NA | [7] |

| Lycopene | 3 to 5 | −48.5 | 90 at 4 and 25 °C | [20] | ||

| 20.8 | −25.3 | NA | [82] |

| Nanosystem | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoemulsions |

|

|

[24,88] |

| Polymeric/biopolymeric NPs |

|

|

[24,28] |

| Nanoliposomes/liposomes |

|

|

[24,73] |

| SLNPs |

|

|

[24,73,88] |

| NLCs |

|

|

[24,88] |

| Supercritical fluid-based NPs |

|

|

[18,73,88] |

| Metal/metal oxide-based NPs and hybrid nanocomposites |

|

|

[80,81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).