Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

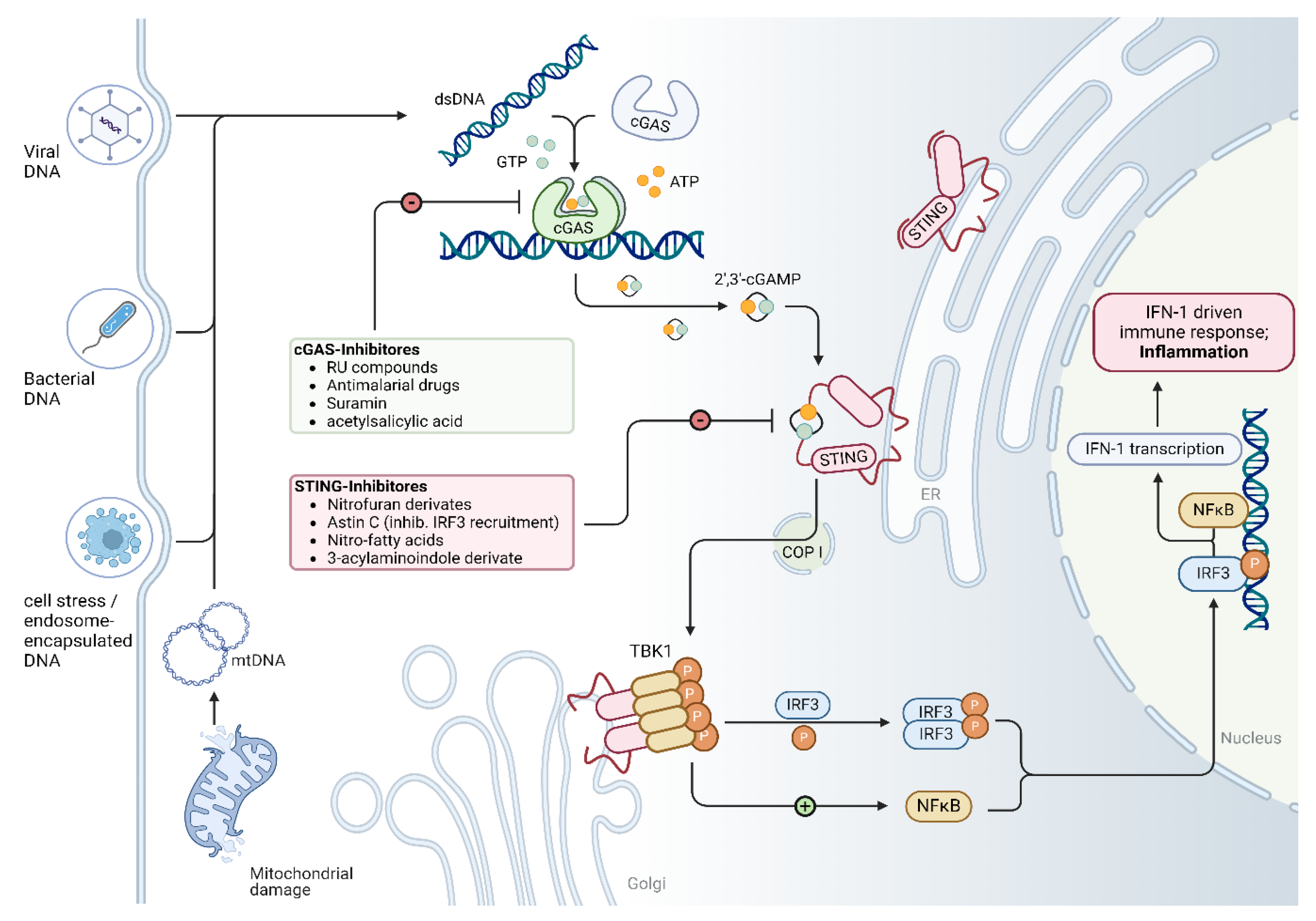

2. Overview of the cGAS/STING Signaling Pathway

3. Activation of cGAS/STING Pathway in Different Cardiomyopathies

3.1. Dilated Cardiomyopathy

3.1.1. LMNA Cardiomyopathy

3.1.2. LEMD2-Associated Cardiomyopathy

3.1.3. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

3.2. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy

3.3. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy

3.5. Other Cardiomyopathies

4. Molecular Intervention and Potential Targets on cGAS/STING Pathway in Cardiomyopathy

4.1. Molecular Intervention on cGAS/STING Pathway in Cardiomyopathy

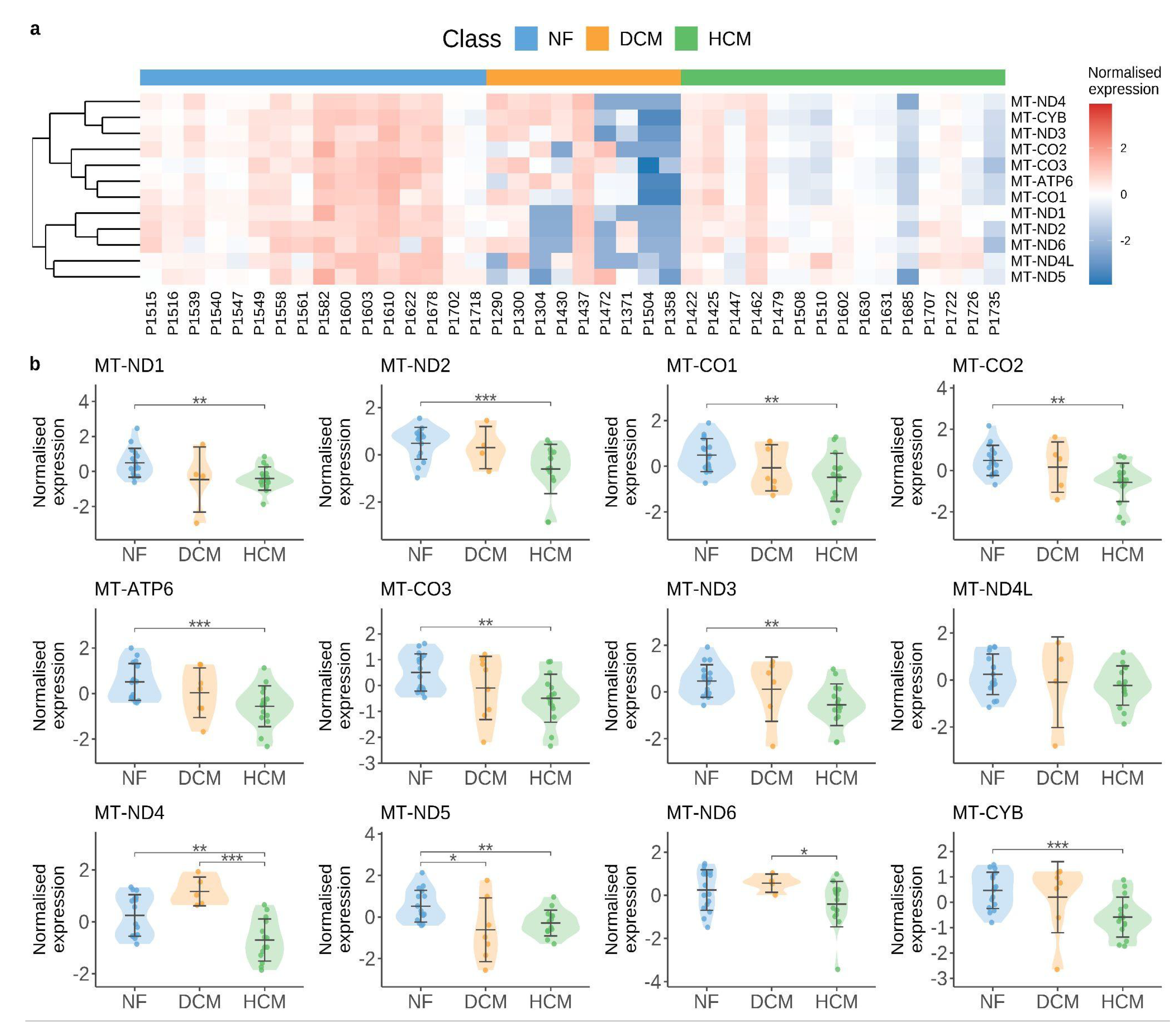

4.2. Mitochondrial Alteration as a Hotspot for cGAS/STING Pathway Activation

4.3. Future Perspectives in Understanding the cGAS/STING Pathway in Cardiomyopathy

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| cGAS | cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding Kinase 1 |

| IRF3 | interferon regulatory factor 3 |

| dsDNA | double-stranded DNA |

References

- Brieler J, Breeden MA, Tucker J. Cardiomyopathy: An Overview. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(10):640-646.

- Ciarambino T, Menna G, Sansone G, Giordano M. Cardiomyopathies: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7722. [CrossRef]

- McKenna WJ, Maron BJ, Thiene G. Classification, Epidemiology, and Global Burden of Cardiomyopathies. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):722-730. [CrossRef]

- Ommen SR, Ho CY, Asif IM, et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR Guideline for the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(23):e1239-e1311. [CrossRef]

- Austin KM, Trembley MA, Chandler SF, et al. Molecular mechanisms of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(9):519-537. [CrossRef]

- van Berlo JH, Maillet M, Molkentin JD. Signaling effectors underlying pathologic growth and remodeling of the heart. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):37-45. [CrossRef]

- Ashrafian H, McKenna WJ, Watkins H. Disease pathways and novel therapeutic targets in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2011;109(1):86-96. [CrossRef]

- Pinilla-Vera M, Hahn VS, Kass DA. Leveraging Signaling Pathways to Treat Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ Res. 2019;124(11):1618-1632. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Sun L, Chen X, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339(6121):826-830. [CrossRef]

- Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339(6121):786-791. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(10):1142-1149. [CrossRef]

- Li XD, Wu J, Gao D, Wang H, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science. 2013;341(6152):1390-1394. [CrossRef]

- Decout A, Katz JD, Venkatraman S, Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(9):548-569. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Wu J, Du F, et al. The cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS forms an oligomeric complex with DNA and undergoes switch-like conformational changes in the activation loop. Cell Rep. 2014;6(3):421-430. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka Y, Chen ZJ. STING specifies IRF3 phosphorylation by TBK1 in the cytosolic DNA signaling pathway. Sci Signal. 2012;5(214):ra20. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Shang G, Gui X, Zhang X, Bai XC, Chen ZJ. Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature. 2019;567(7748):394-398. [CrossRef]

- Nishida K, Otsu K. Inflammation and metabolic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(4):389-398. [CrossRef]

- Shi S, Chen Y, Luo Z, Nie G, Dai Y. Role of oxidative stress and inflammation-related signaling pathways in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Cell Commun Signal CCS. 2023;21(1):61. [CrossRef]

- Harding D, Chong MHA, Lahoti N, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic cardiac inflammation: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. J Intern Med. 2023;293(1):23-47. [CrossRef]

- Nunes JPS, Roda VM de P, Andrieux P, Kalil J, Chevillard C, Cunha-Neto E. Inflammation and mitochondria in the pathogenesis of chronic Chagas disease cardiomyopathy. Exp Biol Med Maywood NJ. 2023;248(22):2062-2071. [CrossRef]

- Luo W, Zou X, Wang Y, et al. Critical Role of the cGAS-STING Pathway in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Circ Res. 2023;132(11):e223-e242. [CrossRef]

- Lei Y, VanPortfliet JJ, Chen YF, et al. Cooperative sensing of mitochondrial DNA by ZBP1 and cGAS promotes cardiotoxicity. Cell. 2023;186(14):3013-3032.e22. [CrossRef]

- Lei C, Tan Y, Ni D, Peng J, Yi G. cGAS-STING signaling in ischemic diseases. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem. 2022;531:177-182. [CrossRef]

- Heymans S, Lakdawala NK, Tschöpe C, Klingel K. Dilated cardiomyopathy: causes, mechanisms, and current and future treatment approaches. Lancet Lond Engl. 2023;402(10406):998-1011. [CrossRef]

- Reichart D, Magnussen C, Zeller T, Blankenberg S. Dilated cardiomyopathy: from epidemiologic to genetic phenotypes: A translational review of current literature. J Intern Med. 2019;286(4):362-372. [CrossRef]

- Weintraub RG, Semsarian C, Macdonald P. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;390(10092):400-414. [CrossRef]

- Peters S, Johnson R, Birch S, Zentner D, Hershberger RE, Fatkin D. Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(4):566-574. [CrossRef]

- McNally EM, Mestroni L. Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Genetic Determinants and Mechanisms. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):731-748. [CrossRef]

- Chen SN, Sbaizero O, Taylor MRG, Mestroni L. Lamin A/C Cardiomyopathy: Implications for Treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21(12):160. [CrossRef]

- Bhide S, Chandran S, Rajasekaran NS, Melkani GC. Genetic and Pathophysiological Basis of Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle Laminopathies. Genes. 2024;15(8):1095. [CrossRef]

- Donnaloja F, Carnevali F, Jacchetti E, Raimondi MT. Lamin A/C Mechanotransduction in Laminopathies. Cells. 2020;9(5):1306. [CrossRef]

- Murray-Nerger LA, Cristea IM. Lamin post-translational modifications: emerging toggles of nuclear organization and function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46(10):832-847. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Ji JY. Understanding lamin proteins and their roles in aging and cardiovascular diseases. Life Sci. 2018;212:20-29. [CrossRef]

- Wong X, Melendez-Perez AJ, Reddy KL. The Nuclear Lamina. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2022;14(2):a040113. [CrossRef]

- Qiu H, Sun Y, Wang X, et al. Lamin A/C deficiency-mediated ROS elevation contributes to pathogenic phenotypes of dilated cardiomyopathy in iPSC model. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7000. [CrossRef]

- Captur G, Arbustini E, Bonne G, et al. Lamin and the heart. Heart Br Card Soc. 2018;104(6):468-479. [CrossRef]

- Ito K, Patel PN, Gorham JM, et al. Identification of pathogenic gene mutations in LMNA and MYBPC3 that alter RNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(29):7689-7694. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Elsherbiny A, Kessler L, et al. Lamin A/C-dependent chromatin architecture safeguards naïve pluripotency to prevent aberrant cardiovascular cell fate and function. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6663. [CrossRef]

- Cheedipudi SM, Asghar S, Marian AJ. Genetic Ablation of the DNA Damage Response Pathway Attenuates Lamin-Associated Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Mice. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2022;7(12):1232-1245. [CrossRef]

- En A, Bogireddi H, Thomas B, et al. Pervasive nuclear envelope ruptures precede ECM signaling and disease onset without activating cGAS-STING in Lamin-cardiomyopathy mice. Cell Rep. 2024;43(6):114284. [CrossRef]

- Zuela-Sopilniak N, Morival J, Lammerding J. Multi-level transcriptomic analysis of LMNA -related dilated cardiomyopathy identifies disease-driving processes. BioRxiv Prepr Serv Biol. Published online June 13, 2024:2024.06.11.598511. [CrossRef]

- Feurle P, Abentung A, Cera I, et al. SATB2-LEMD2 interaction links nuclear shape plasticity to regulation of cognition-related genes. EMBO J. 2021;40(3):e103701. [CrossRef]

- Thanisch K, Song C, Engelkamp D, et al. Nuclear envelope localization of LEMD2 is developmentally dynamic and lamin A/C dependent yet insufficient for heterochromatin tethering. Differ Res Biol Divers. 2017;94:58-70. [CrossRef]

- Vargas JD. The Role of the LEMD2 p.L13R Mutation in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2023;132(2):185-186. [CrossRef]

- Caravia XM, Ramirez-Martinez A, Gan P, et al. Loss of function of the nuclear envelope protein LEMD2 causes DNA damage-dependent cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(22):e158897. [CrossRef]

- Abdelfatah N, Chen R, Duff HJ, et al. Characterization of a Unique Form of Arrhythmic Cardiomyopathy Caused by Recessive Mutation in LEMD2. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4(2):204-221. [CrossRef]

- Chen R, Buchmann S, Kroth A, et al. Mechanistic Insights of the LEMD2 p.L13R Mutation and Its Role in Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2023;132(2):e43-e58. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Almorós A, Cepeda-Rodrigo JM, Lorenzo Ó. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Rev Clin Esp. 2022;222(2):100-111. [CrossRef]

- Dillmann WH. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2019;124(8):1160-1162. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Liu S, Wang X, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: Clinical phenotype and practice. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:1032268. [CrossRef]

- Khan S, Ahmad SS, Kamal MA. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: From Mechanism to Management in a Nutshell. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21(2):268-281. [CrossRef]

- Peterson LR, Gropler RJ. Metabolic and Molecular Imaging of the Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2020;126(11):1628-1645. [CrossRef]

- Ma XM, Geng K, Law BYK, et al. Lipotoxicity-induced mtDNA release promotes diabetic cardiomyopathy by activating the cGAS-STING pathway in obesity-related diabetes. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2023;39(1):277-299. [CrossRef]

- Yan M, Li Y, Luo Q, et al. Mitochondrial damage and activation of the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS-STING pathway lead to cardiac pyroptosis and hypertrophy in diabetic cardiomyopathy mice. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):258. [CrossRef]

- Lu QB, Ding Y, Liu Y, et al. Metrnl ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy via inactivation of cGAS/STING signaling dependent on LKB1/AMPK/ULK1-mediated autophagy. J Adv Res. 2023;51:161-179. [CrossRef]

- Lu L, Shao Y, Xiong X, et al. Irisin improves diabetic cardiomyopathy-induced cardiac remodeling by regulating GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis through MITOL/STING signaling. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2024;171:116007. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Lai X, Li J, et al. BRG1 Deficiency Promotes Cardiomyocyte Inflammation and Apoptosis by Activating the cGAS-STING Signaling in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Inflammation. Published online June 13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huang Q, Chen T, Li J, et al. IL-37 ameliorates myocardial fibrosis by regulating mtDNA-enriched vesicle release in diabetic cardiomyopathy mice. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):494. [CrossRef]

- Corrado D, Basso C, Judge DP. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):784-802. [CrossRef]

- Smith ED, Lakdawala NK, Papoutsidakis N, et al. Desmoplakin Cardiomyopathy, a Fibrotic and Inflammatory Form of Cardiomyopathy Distinct From Typical Dilated or Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;141(23):1872-1884. [CrossRef]

- Gacita AM, McNally EM. Genetic Spectrum of Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(3):e005850. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi R, Marian AJ. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy is a disease of cardiac stem cells. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25(3):222-228. [CrossRef]

- Desai YB, Parikh VN. Genetic Risk Stratification in Arrhythmogenic Left Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2023;15(3):391-399. [CrossRef]

- Kang H, Lee CJ. Transmembrane proteins with unknown function (TMEMs) as ion channels: electrophysiological properties, structure, and pathophysiological roles. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56(4):850-860. [CrossRef]

- Matos J, Helle E, Care M, et al. Cardiac MRI and Clinical Outcomes in TMEM43 Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2023;5(6):e230155. [CrossRef]

- Rouhi L, Cheedipudi SM, Chen SN, et al. Haploinsufficiency of Tmem43 in cardiac myocytes activates the DNA damage response pathway leading to a late-onset senescence-associated pro-fibrotic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117(11):2377-2394. [CrossRef]

- Almajidi YQ, Kadhim MM, Alsaikhan F, et al. Doxorubicin-loaded micelles in tumor cell-specific chemotherapy. Environ Res. 2023;227:115722. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho C, Santos RX, Cardoso S, et al. Doxorubicin: the good, the bad and the ugly effect. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(25):3267-3285. [CrossRef]

- Sheibani M, Azizi Y, Shayan M, et al. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: An Overview on Pre-clinical Therapeutic Approaches. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2022;22(4):292-310. [CrossRef]

- Kong CY, Guo Z, Song P, et al. Underlying the Mechanisms of Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Cardiotoxicity: Oxidative Stress and Cell Death. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18(2):760-770. [CrossRef]

- Rawat PS, Jaiswal A, Khurana A, Bhatti JS, Navik U. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: An update on the molecular mechanism and novel therapeutic strategies for effective management. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2021;139:111708. [CrossRef]

- Wallace KB, Sardão VA, Oliveira PJ. Mitochondrial Determinants of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2020;126(7):926-941. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Shi S, Dai Y. Research progress of therapeutic drugs for doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2022;156:113903. [CrossRef]

- de Baat EC, Mulder RL, Armenian S, et al. Dexrazoxane for preventing or reducing cardiotoxicity in adults and children with cancer receiving anthracyclines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;9(9):CD014638. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi P, Barootkoob B, ElHashash A, Nair A. Efficacy of Dexrazoxane in Cardiac Protection in Pediatric Patients Treated With Anthracyclines. Cureus. 2023;15(4):e37308. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Z, Yu Z, Chen C, Chen R, Su Y. GAS-STING signaling plays an essential pathogenetic role in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023;24(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T, et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1639-1642. [CrossRef]

- Srzić I, Nesek Adam V, Tunjić Pejak D. SEPSIS DEFINITION: WHAT’S NEW IN THE TREATMENT GUIDELINES. Acta Clin Croat. 2022;61(Suppl 1):67-72. [CrossRef]

- Jacobi J. The pathophysiology of sepsis - 2021 update: Part 2, organ dysfunction and assessment. Am J Health-Syst Pharm AJHP Off J Am Soc Health-Syst Pharm. 2022;79(6):424-436. [CrossRef]

- Bleakley G, Cole M. Recognition and management of sepsis: the nurse’s role. Br J Nurs Mark Allen Publ. 2020;29(21):1248-1251. [CrossRef]

- Hollenberg SM, Singer M. Pathophysiology of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(6):424-434. [CrossRef]

- L’Heureux M, Sternberg M, Brath L, Turlington J, Kashiouris MG. Sepsis-Induced Cardiomyopathy: a Comprehensive Review. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22(5):35. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Zhou H, Wu H, et al. STING-IRF3 contributes to lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac dysfunction, inflammation, apoptosis and pyroptosis by activating NLRP3. Redox Biol. 2019;24:101215. [CrossRef]

- Kong C, Ni X, Wang Y, et al. ICA69 aggravates ferroptosis causing septic cardiac dysfunction via STING trafficking. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):187. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Hu Q, Ren K, Wu P, Wang Y, Lv C. ALDH2 mitigates LPS-induced cardiac dysfunction, inflammation, and apoptosis through the cGAS/STING pathway. Mol Med Camb Mass. 2023;29(1):171. [CrossRef]

- Bremer J. Carnitine--metabolism and functions. Physiol Rev. 1983;63(4):1420-1480. [CrossRef]

- Scholte HR, Rodrigues Pereira R, de Jonge PC, et al. Primary carnitine deficiency. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem Z Klin Chem Klin Biochem. 1990;28(5):351-357.

- Berg SM, Beck-Nielsen H, Færgeman NJ, Gaster M. Carnitine acetyltransferase: A new player in skeletal muscle insulin resistance? Biochem Biophys Rep. 2017;9:47-50. [CrossRef]

- Song MJ, Park CH, Kim H, et al. Carnitine acetyltransferase deficiency mediates mitochondrial dysfunction-induced cellular senescence in dermal fibroblasts. Aging Cell. 2023;22(11):e14000. [CrossRef]

- Mao H, Angelini A, Li S, et al. CRAT links cholesterol metabolism to innate immune responses in the heart. Nat Metab. 2023;5(8):1382-1394. [CrossRef]

- Echavarría NG, Echeverría LE, Stewart M, Gallego C, Saldarriaga C. Chagas Disease: Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46(3):100507. [CrossRef]

- Santos É, Menezes Falcão L. Chagas cardiomyopathy and heart failure: From epidemiology to treatment. Rev Port Cardiol. 2020;39(5):279-289. [CrossRef]

- Nunes MCP, Beaton A, Acquatella H, et al. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Current Clinical Knowledge and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138(12):e169-e209. [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri S, Garg NJ. PARP1-cGAS-NF-κB pathway of proinflammatory macrophage activation by extracellular vesicles released during Trypanosoma cruzi infection and Chagas disease. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(4):e1008474. [CrossRef]

- Medina de Chazal H, Del Buono MG, Keyser-Marcus L, et al. Stress Cardiomyopathy Diagnosis and Treatment: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(16):1955-1971. [CrossRef]

- Amin HZ, Amin LZ, Pradipta A. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: A Brief Review. J Med Life. 2020;13(1):3-7. [CrossRef]

- Dawson DK. Acute stress-induced (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. Heart Br Card Soc. 2018;104(2):96-102. [CrossRef]

- Ravindran J, Brieger D. Clinical perspectives: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Intern Med J. 2024;54(11):1785-1795. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Tang X, Cui J, et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 mitigates acute catecholamine surge-induced myocardial injuries in part by suppressing STING-mediated macrophage activation. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2024;175:116794. [CrossRef]

- Chaffin M, Papangeli I, Simonson B, et al. Single-nucleus profiling of human dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nature. 2022;608(7921):174-180. [CrossRef]

- Jenson JM, Li T, Du F, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin-like conjugation by bacterial cGAS enhances anti-phage defence. Nature. 2023;616(7956):326-331. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers JL, Jones J, Bolleddu SI, et al. Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Gender and Aging. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2019;6(2):19. [CrossRef]

- Tahsili-Fahadan P, Geocadin RG. Heart-Brain Axis: Effects of Neurologic Injury on Cardiovascular Function. Circ Res. 2017;120(3):559-572. [CrossRef]

| Cardiomyopathy | Year | Model | Methods | Conclusion | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy (SIC) | 2019 | ∙ In vivo: Male mouse injected with LPS ∙ In vitro: Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs); H9C2 cells |

∙ IB ∙ IF ∙ Real time RT-qPCR |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in LPS-treated heart tissues and cardiomyocytes. ∙ Activated molecules: NLRP3, IRF3, IL-1β, TNF-α, MCP-1, HMGBA, caspase-1, IL-18 ∙ STING knockdown inhibits LPS-induced phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3, suppresses inflammation, apoptosis and pyroptosis, improves cardiac function and survival. |

[1] |

| 2022 | ∙ Human blood samples ∙ In vivo: Male mouse injected with LPS ∙ In vitro: RAW 264.7 macrophages. H9C2 myofibroblasts |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR |

∙ STING is activated in LPS-treated cardiac tissues. ∙ STING is increased in the peripheral blood samples of septic patients. ∙ Activated molecules: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, COX2. ∙ ICA69 knockout inhibits STING-mediated inflammation and ferroptosis. |

[2] | |

| 2023 | ∙ In vivo: LPS-treated mouse ∙ In vitro: LPS-stimulated H9C2 cells (rat cardiomyocytes) |

∙ IB ∙ ELISA ∙ IF/IHC |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in both heart tissue and H9C2 cells following LPS treatment. ∙ Activated molecules: IRF3, TBK1, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α. ∙ Knocking down cGAS in H9C2 cardiomyocytes alleviates cardiac inflammation and apoptosis induced by LPS. ∙ ALDH2 inhibits cGAS/STING signaling both in vivo and in vitro. |

[3] | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 2023 | ∙ In vivo: Myh6-Cre:LmnaF/F:Crat-/- mouse ∙ In vitro: Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR ∙ RNA-Seq ∙ scRNA-Seq |

∙ cGAS and type I interferon responses are activated in CRAT-deficient NRVMs. ∙ Activated molecules: IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α ∙ Knockdown of cGAS abrogates interferon-stimulated gene expression. |

[4] |

| 2023 | ∙ Human hearts with DCM | ∙ IB ∙ RNA-Seq |

∙ cGAS is increased in human heart samples from patients with primary DCM. ∙ STING1 and phospho-STING1 (serine residue 365) are unchanged. ∙ Activated molecules: TBK1. |

[5] | |

| 2022 | ∙ In vivo (LMNA–DCM model): Myh6-Cre:LmnaF/F mouse; Myh6-Cre:LmnaF/F:Mb21d1-/- mouse |

∙ IB ∙ IF |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in LMNA-DCM whole heart tissue. ∙ Activated molecules: ATM, H2AFX, p-TP53, total TP53, CDKN1A. ∙ Knockout of CGAS prolonged survival, improved cardiac function, partially restored levels of molecular markers of heart failure, and attenuated myocardial apoptosis and fibrosis in the LMNA-deficient mice. |

[6] | |

| 2024 | ∙ In vivo (LMNA–DCM model): LmnaF/F;Myh6-MerCreMer mouse |

∙ IF/IHC ∙ snRNA-seq |

∙ cGAS/STING-related transcription is not activated in cardiomyocytes. ∙ CGAS or STING knockout does not rescue the phenotypes of LMNA-DCM. |

[7] | |

| Diabetic cardiomyopathy | 2022 | ∙ In vivo: Male db/db and db/+ mouse ∙ In vitro: Palmitic acid (PA)-treated H9C2 cells (rat cardiomyocytes) |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR |

∙ Mitochondria-derived mtDNA can activate cGAS/STING pathway in cardiomyocytes. ∙ Activated molecules: IRF3, NF-κB, IL-18, IL-1β. ∙ Knockdown of STING in H9C2 cardiomyocytes and inhibition of STING with C176 can ameliorate myocardial inflammation and apoptosis. |

[8] |

| 2022 | ∙ In vivo: Male mouse ∙ In vitro: Palmitic acid (PA)-treated H9C2 cells (rat cardiomyocytes) |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR |

∙ Cytosolic mtDNA activates cGAS/STING in DCM hearts and H9C2 cells. ∙ Activated molecules: p-TBK1, p-IRF3, NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD, TNF-α, INF-β, IL-1β, IL-18. ∙ cGAS or STING knockdown inhibits cardiomyocyte pyroptosis and inflammation. |

[9] | |

| 2023 | ∙ In vivo: STZ-treated mouse; db/db mouse ∙ In vitro: Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs); cultured cardiac fibroblasts; endothelial cells |

∙ IB ∙ IF ∙ TUNEL ∙ Real time RT-qPCR |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated by ULK1 in cardiomyocytes. ∙ Metrnl downregulation exacerbates high glucose-elicited hypertrophy, apoptosis, and oxidative damage in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. ∙ Metrnl activates the autophagy pathway and inhibits the cGAS/STING signaling in a LKB1/AMPK/ULK1-dependent mechanism in cardiomyocytes. |

[10] | |

| 2023 | ∙ In vivo: STZ-treated and HFD-fed mouse ∙ In vitro: Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR ∙ TUNEL |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in cardiomyocytes both in vivo and in vitro. ∙ Activated molecules: p-TBK, p-NF-κB, IL-1β, Caspase-3. ∙ BRG1 deficiency results in the accumulation of dsDNA and triggers cGAS/STING, exacerbating cardiomyocyte inflammation and apoptosis induced by hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. |

[11] | |

| 2024 | ∙ In vivo: Human blood samples; STZ-treated and HFD-fed mouse ∙ In vitro: |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR ∙ TUNEL |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in fibroblasts which engulf released extracellular vesicles containing mtDNA from cardiomyocytes. ∙ Activated molecules: p-TBK1, p-IRF3, p-p65, IL-37. ∙ IL-37 ameliorates mitochondrial injury, reduces the release of mtDNA-enriched vesicles, which attenuates the progression of DCM. |

[12] | |

| 2024 | ∙ In vivo: STZ-treated and HFD-fed mouse ∙ In vitro: HG/HF-treated H9C2 cells |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in myocardium and H9C2 cells. ∙ Activated molecules: MITOL, NLRP3, Caspase 1, IL-1β, GSDMD. ∙ Irisin and MITOL administration alleviates cardiac dysfunction via inhibition of the cGAS/STING pathway. |

[13] | |

| Other cardiomyopathies | 2021 | TMEM43 arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy ∙ In vivo: Myh6-Cre:Tmem43W/F mice |

∙ IB ∙ IF ∙ bulk RNA-Seq |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in cardiomyocytes at later stage. ∙ Activated molecules: pATM, ATM, pH2AFX, LGALS3, VCAN, GDF15, TGFβ1. |

[14] |

| 2020 | Chagas cardiomyopathy ∙ In vivo: T. cruzi trypomastigotes infected mice ∙ In vitro: Murine bone marrow cells; RAW 264.7 macrophages; C2C12 mouse myoblast cells |

∙ IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR |

∙ cGAS/STING is the early responder in recognizing T.cruzi-induced extracellular vesicles stimulus and signaling proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in macrophages. ∙ Activated molecules: NF-κB, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α. ∙ PARP1 synergizes with cGAS in signaling the NF-κB transcriptional activity in macrophages; inhibition of PARP1 reduces myocardial inflammatory infiltrates and improves the left ventricular function. |

[15] | |

| 2024 | Stress cardiomyopathy ∙ In vivo: Ovariectomized mice treated with isoproterenol; ∙ In vitro: RAW 264.7 macrophages |

∙ IF/IHC ∙ bulk RNA-seq |

∙ STING is activated in macrophages. ∙ Activated molecules: TBK1, TNF, IL6, CCL2, IFN-β. ∙ Ginsenoside Rb1 suppresses DNA-stimulated STING-mediated proinflammatory activation of macrophages. |

[16] | |

| 2023 | LEMD2 arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy ∙ In vivo: Lemd2 p.L13R knock-in mouse ∙ In vitro: HeLa LEMD2 p.L13R KI; HeLa LEMD2 DEL; HEK293 |

∙ IF ∙ bulk RNA-seq |

∙ cGAS is recruited to the nuclear envelope rupture sites and micronuclei, subsequently activating cGAS/STING/IFN pathway in mutant LEMD2 cell lines. ∙ Activated molecules: H2AFX, SASPs (Gdf15, Tgfβ2 and Edn3) |

[17] | |

| 2023 | Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy ∙ In vivo: Male mouse treated with doxorubicin for acute injury |

∙ IB ∙ IF/IHC ∙ Real time RT-qPCR ∙ TUNEL |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in myocardium. ∙ Activated molecules: p-IRF3, p-p65, p-TBK1. ∙ STING knockdown reduces vacuolization and myofibril loss, suppresses inflammation and apoptosis, improves survival and cardiac function. |

[18] | |

| 2023 | Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy ∙ In vivo: Mouse treated with low-dose doxorubicin for chronic injury ∙ In vitro: human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (HCMECs) |

∙ IB ∙ IF ∙ Real time RT-qPCR ∙ bulk RNA-Seq |

∙ cGAS/STING is activated in cardiac endothelial cells. ∙ Activated molecules: p-TBK1, p-IRF3 ∙ Global cGAS, Sting, and Irf3 deficiency ameliorates DIC. ∙ Endothelial cell-specific Sting deficiency prevents DIC and endothelial dysfunction. |

[19] |

| Target | Compound / Drug | Mode of action | Effects on signalling cascades and in animal models | Testing systems | Disease to be investigated in the animal model: | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cGAS | RU-compounds (RU.365, RU.521) |

catalytic site inhibitor | reduced expression levels of Ifnb1 mRNA in Trex knockout mice (which constitutively activate cGAS) ∙ ↓ IL-1β, ↓ cleaved caspase-3 ∙ ↓ apoptosis |

In vivo: Trex1−/− mice In vitro: Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) |

multi-organ inflammation Diabetic cardiomyopathy |

[20] |

| Antimalarial drugs (i.e. Hydroxychloroquine, Quinacrine) |

disrupting dsDNA binding | Hydroxychloroquine and Quinacrine inhibit dsDNA binding to cGAS in vitro: ↓ IFN-β expression In vivo: ↓ early IFN-1 response in Hydroxycloroquine-treated mice |

In vitro: THP1-Dual cells In vivo: C57BL/6 mice UVB inflammation model |

[21] | ||

| Suramin | disrupting dsDNA binding | suramin inhibits dsDNA binding to cGAS in vitro THP1-Dual cells: ↓ IFN-β expression (mRNA and protein) |

In vitro: THP1-Dual cells |

[22] | ||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | cGAS acetylation and inhibition | ↓ IFN-production in vitro (THP-1 cells) and ↓ expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) Trex1–/– bone marrow cells; ↓ ISG expression in the hearts of Trex1–/– mice |

In vitro: - THP-1 cells - Trex1–/– bone marrow In vivo: Trex1–/– mice |

multi-organ inflammation | [23] | |

| STING and TBK1 | Astin C | STING inhibition- targeting the cyclic dinucleotide binding site | ↓ expression of Ifnb, Cxcl10, Isg15, Isg56 and Tnf mRNA in the heart of Trex1-/- mice (in vivo); ↓ expression of type 1 interferone in Trex1−/− bone marrow cells (in vitro) |

In vivo: Trex1−/− mice In vitro: Trex1−/− bone marrow cells |

multi-organ inflammation | [24] |

| Nitrofuran derivatives - C176 and C178 |

STING inhibition – Covalent binding to cysteine residue 91, inhibiting palmitoylation and activation of STING |

↓ serum levels of type I interferons and IL-6 in Trex1−/− mice |

In vivo: Trex1−/− mice |

multi-organ inflammation |

[25] | |

| ↓ phosphorylation of p65 ↑ improve diastolic cardiac function ↑ Partially improve myocardial hypertrophy |

In vivo: db/db mice In vitro: H9C2 rat cardiomyocytes |

Diabetic cardiomyopathy | [26] | |||

| ↓ cardiac IRF3 phosphorylation, IRF3 nuclear translocation and CD38 expression. ↑ cardiomyocyte NAD levels, mitochondrial function and ↑ left ventricular systolic function. ↓ cardiomyocyte apoptosis. ↓ antitumor effects of doxorubicin |

In vivo: Tumor free doxorubicin treated mice |

Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy (DIC) | [27] | |||

| ∙ ↓ IL-1β, cleaved caspase-3; ∙ no effect on γ-H2AX; ∙ ↓ apoptosis |

∙ In vitro: Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) |

Diabetic cardiomyopathy | [28] | |||

| Amlexanox | TBK1 inhibitor | Same effect as C176 |

In vivo: Tumor free doxorubicin treated mice |

Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy (DIC) | [29] | |

| 3-acylaminoindole derivative - H-151 |

STING inhibition – blocking the activation-induced palmitoylation and clustering of STING |

↓ calf thymus DNA-induced production of TNF in a dose-dependent manner |

In vitro: calf thymus DNA-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (DMXAA stimulated – STING activator) |

Stress cardiomyopathy (SCM) | [30] | |

| ↓ reduced IFN-β levels in a dose-dependent manner |

In vitro: RAW264.7 cells stimulated with recombinant murine (rm) CIRP |

[31] | ||||

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | major chemical constituent of ginseng; suppressing the activation of STING |

↓ STING-mediated proinflammatory activation of macrophages. ↓ myocardial fibrosis and inflammatory responses in the heart. ↓ DNA-triggered proinflammatory activation of macrophages. ↓ DNA-triggered whole-genome gene expression alterations in macrophages; |

In vivo: OVX-ISO mice; In vitro: calf thymus DNA-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (DMXAA stimulated – STING activator) |

Stress cardiomyopathy (SCM) | [32] | |

| DMXAA | STING agonist | ↑STING phosphorylation. ↑TNF, IL6, CCL2, IFN-β; |

∙ In vitro: RAW264.7 cells |

Stress cardiomyopathy (SCM) | [33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).