Submitted:

01 August 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

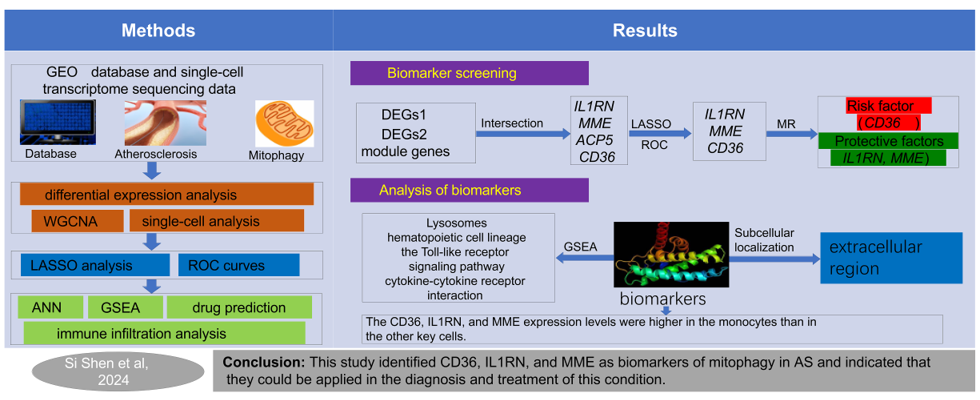

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

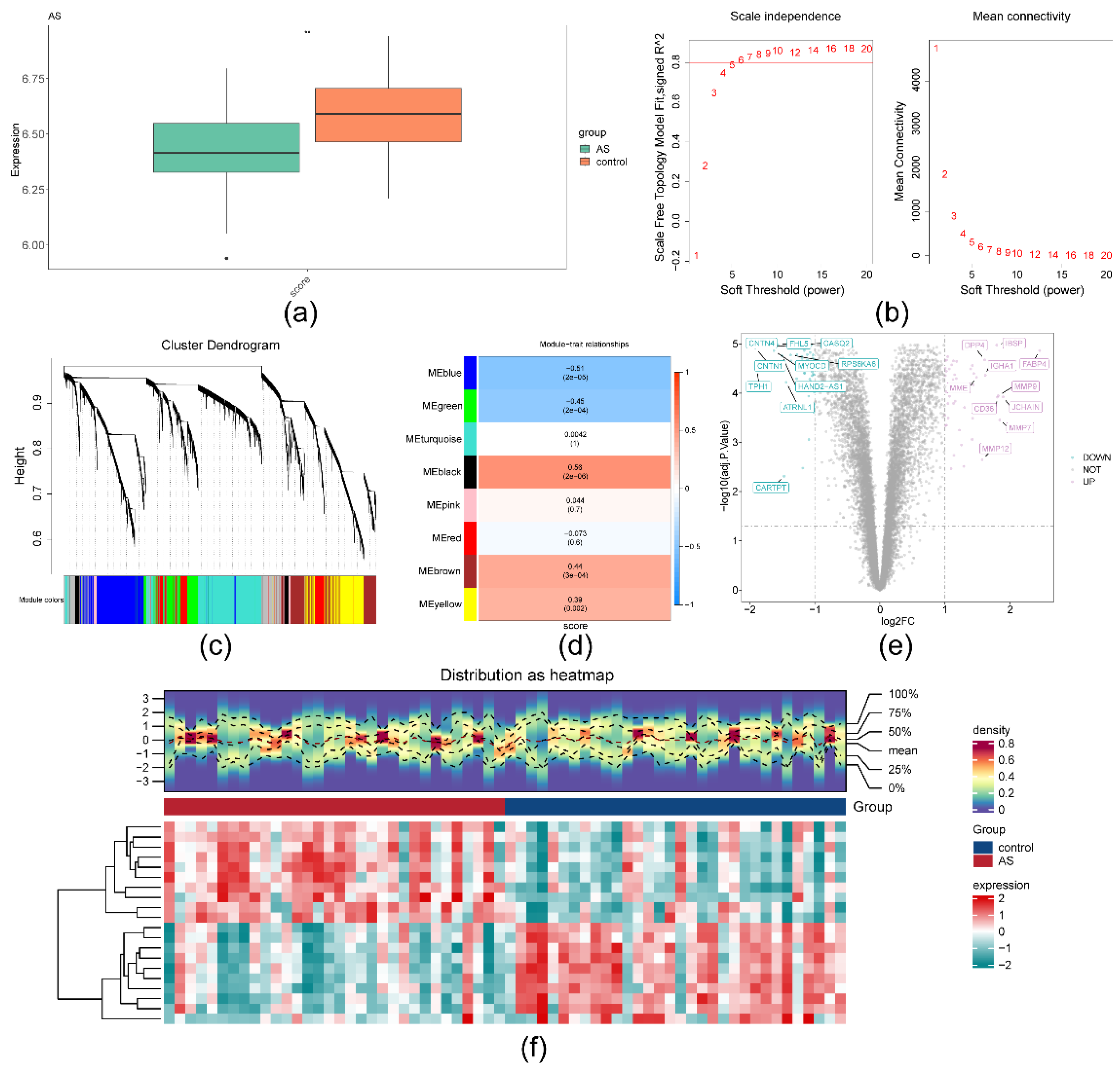

2.1. A total of 4,001 module genes and 102 DEGs1 were obtained in AS

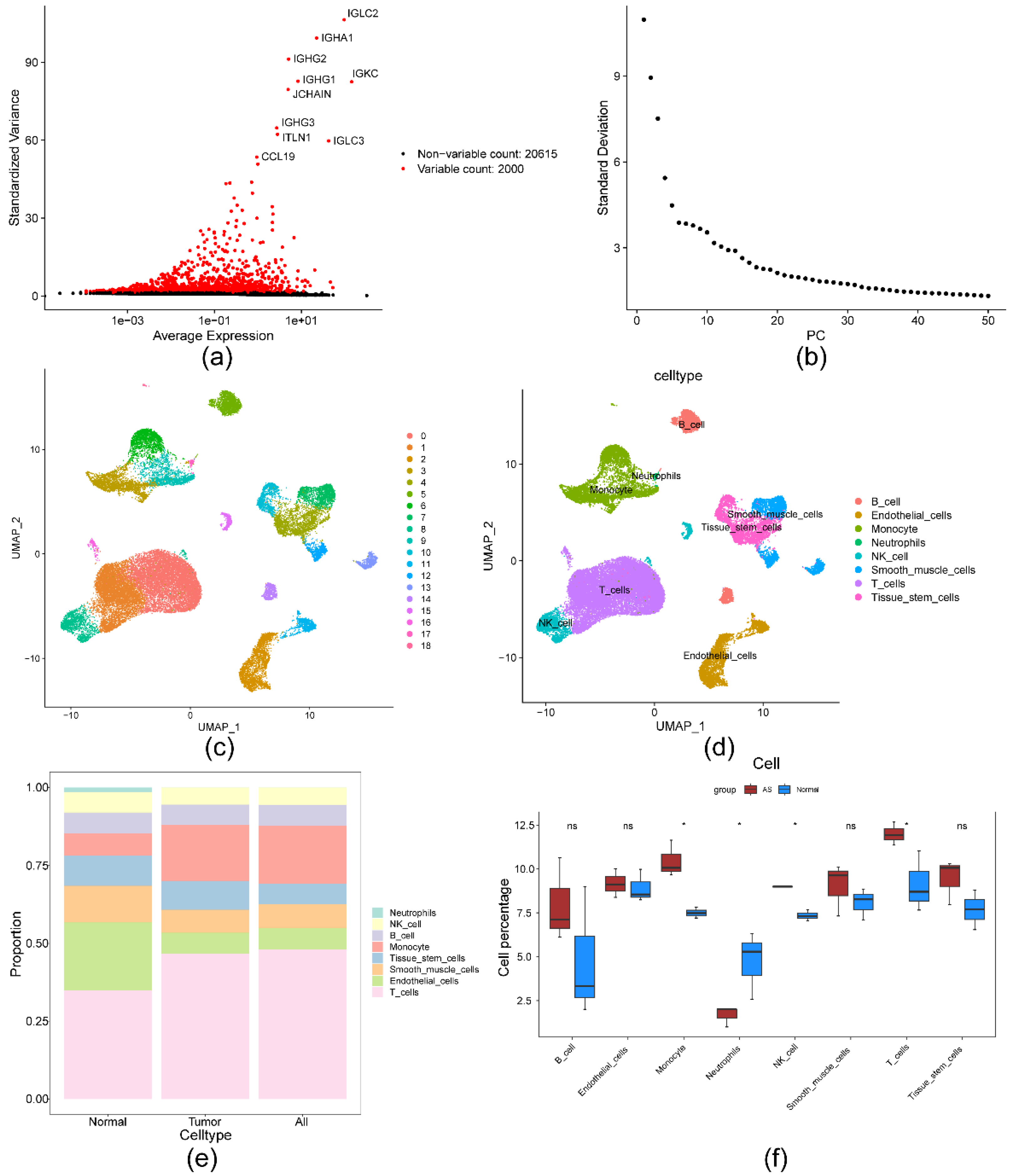

2.2. ScRNA-Seq analysis identified 818 DEGs2

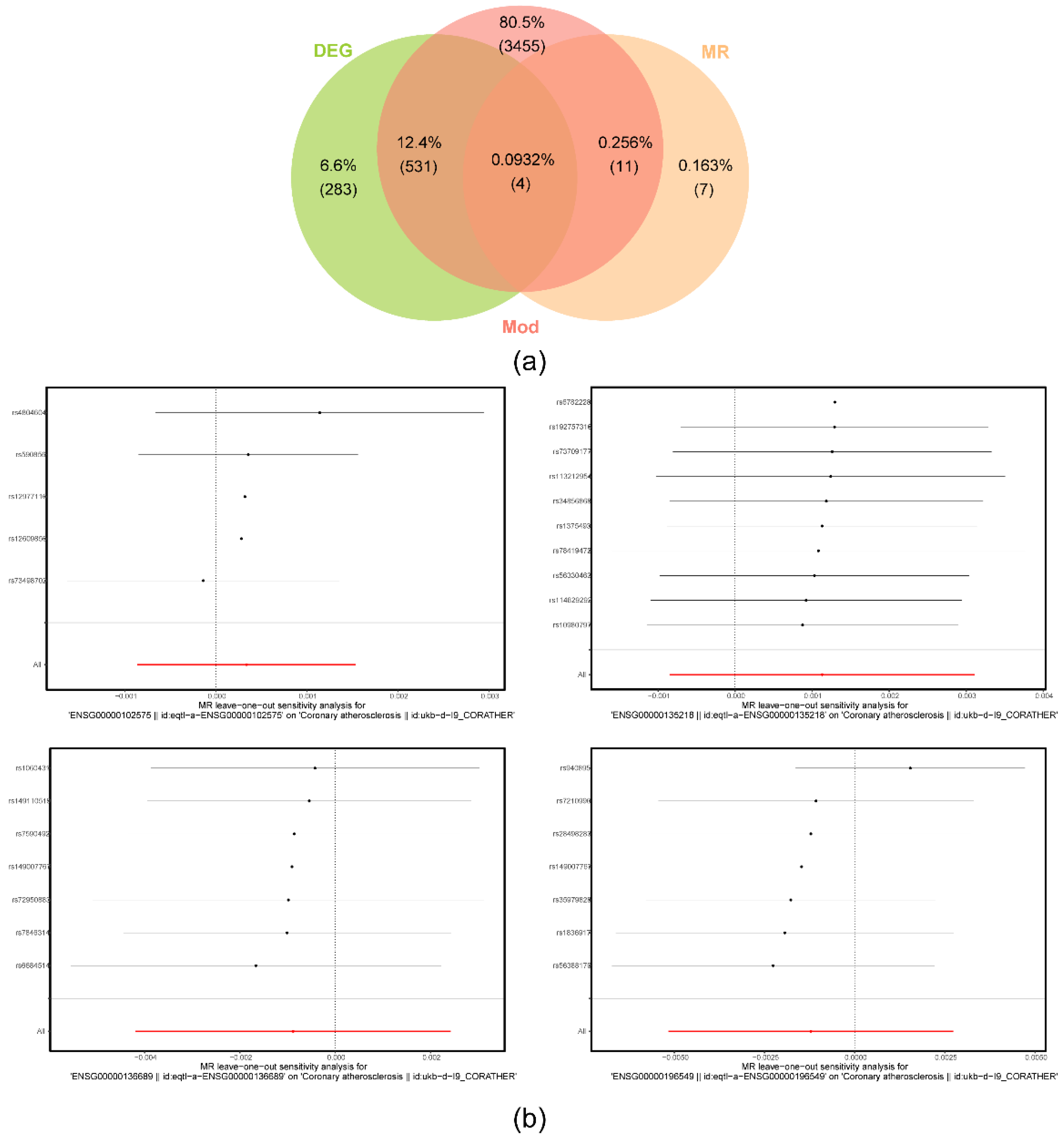

2.3. IL1RN, MME, ACP5 and CD36 detected and identified by MR analysis

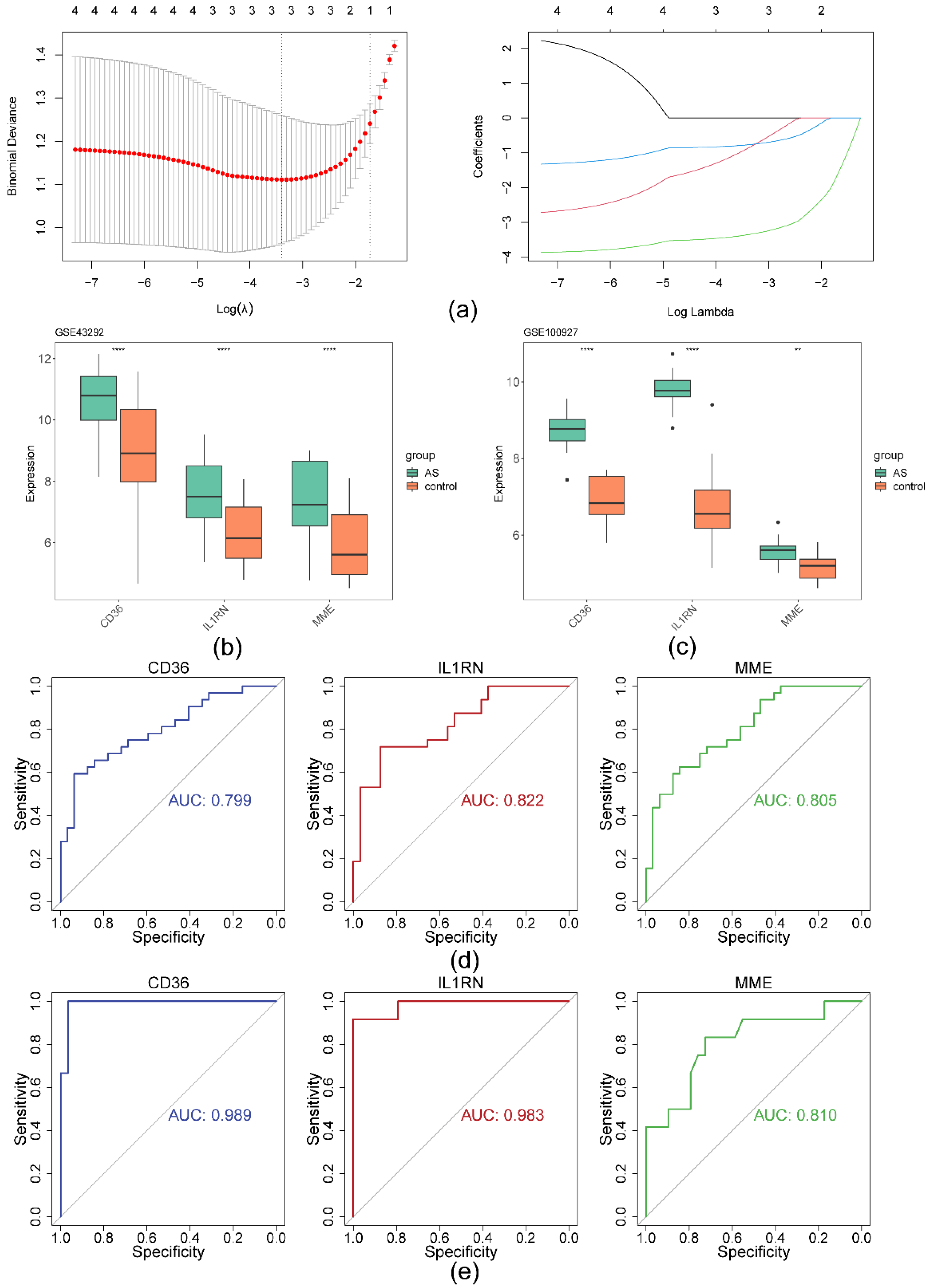

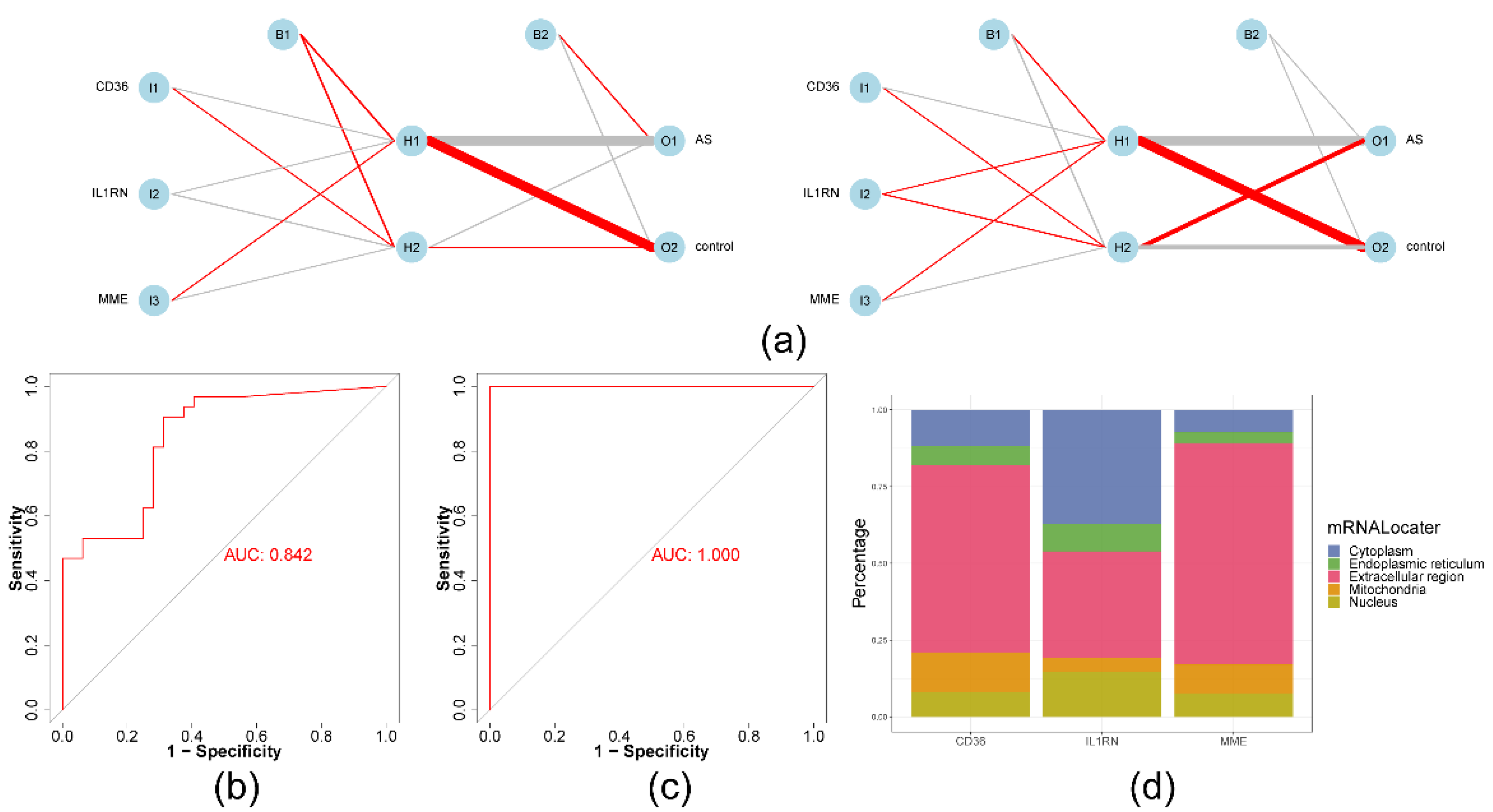

2.4. The ANN model had greater diagnostic power for AS than any other biomarker

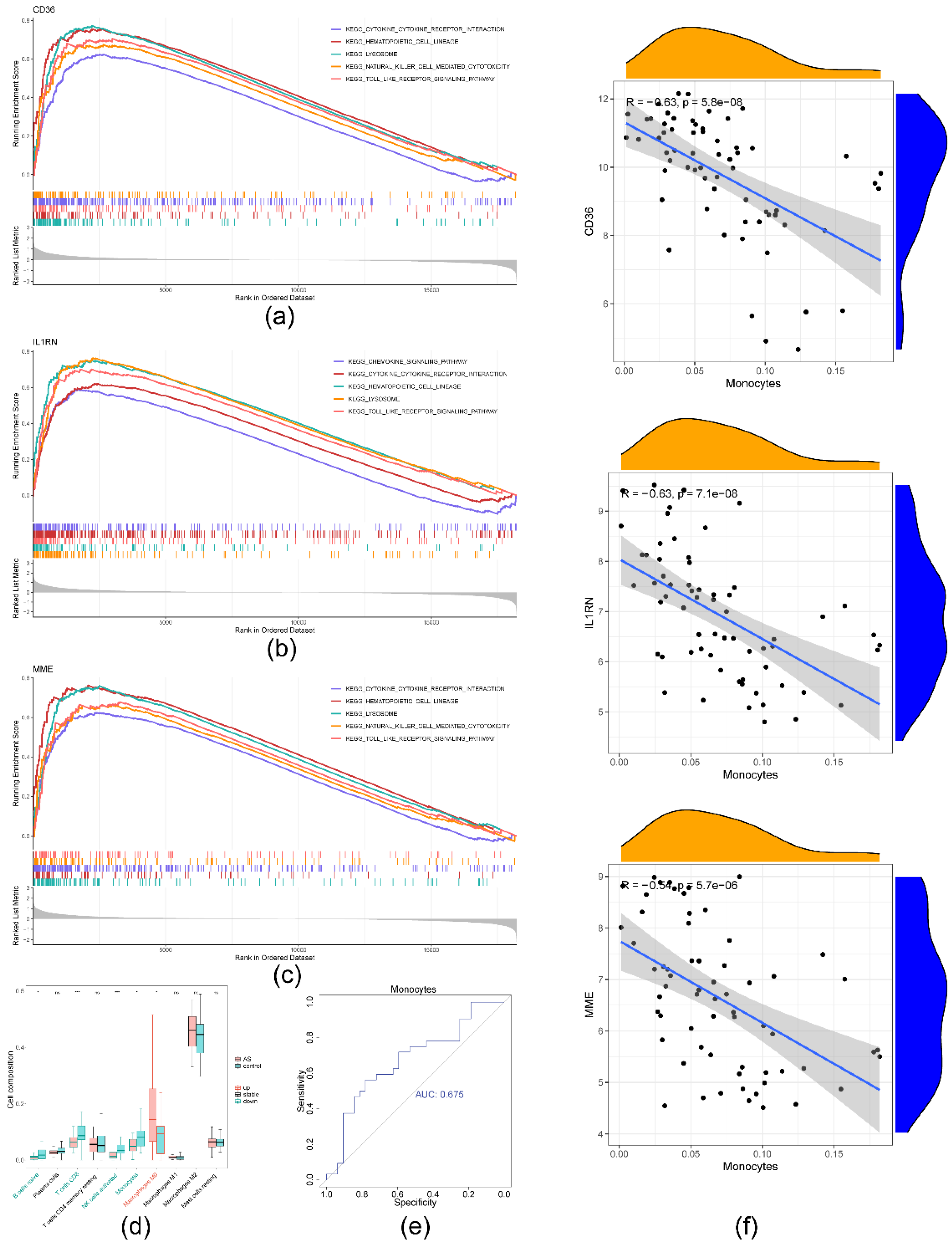

2.5. Significant strong positive correlations between the biomarkers and monocytes

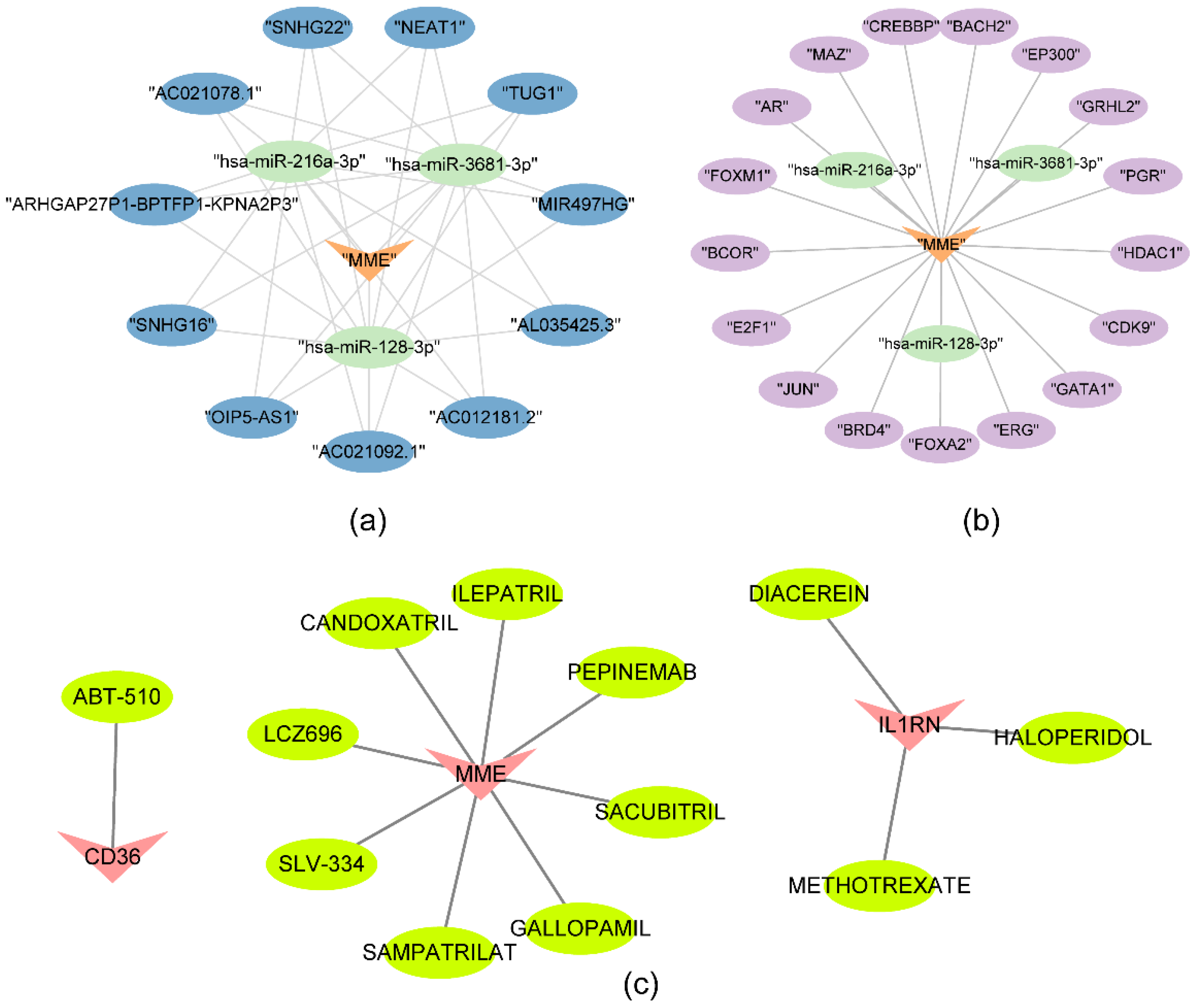

2.6. SNHG16 regulated MME through hsa-miR-216a-3p, hsa-miR-3681-3p and hsa-miR-128-3p

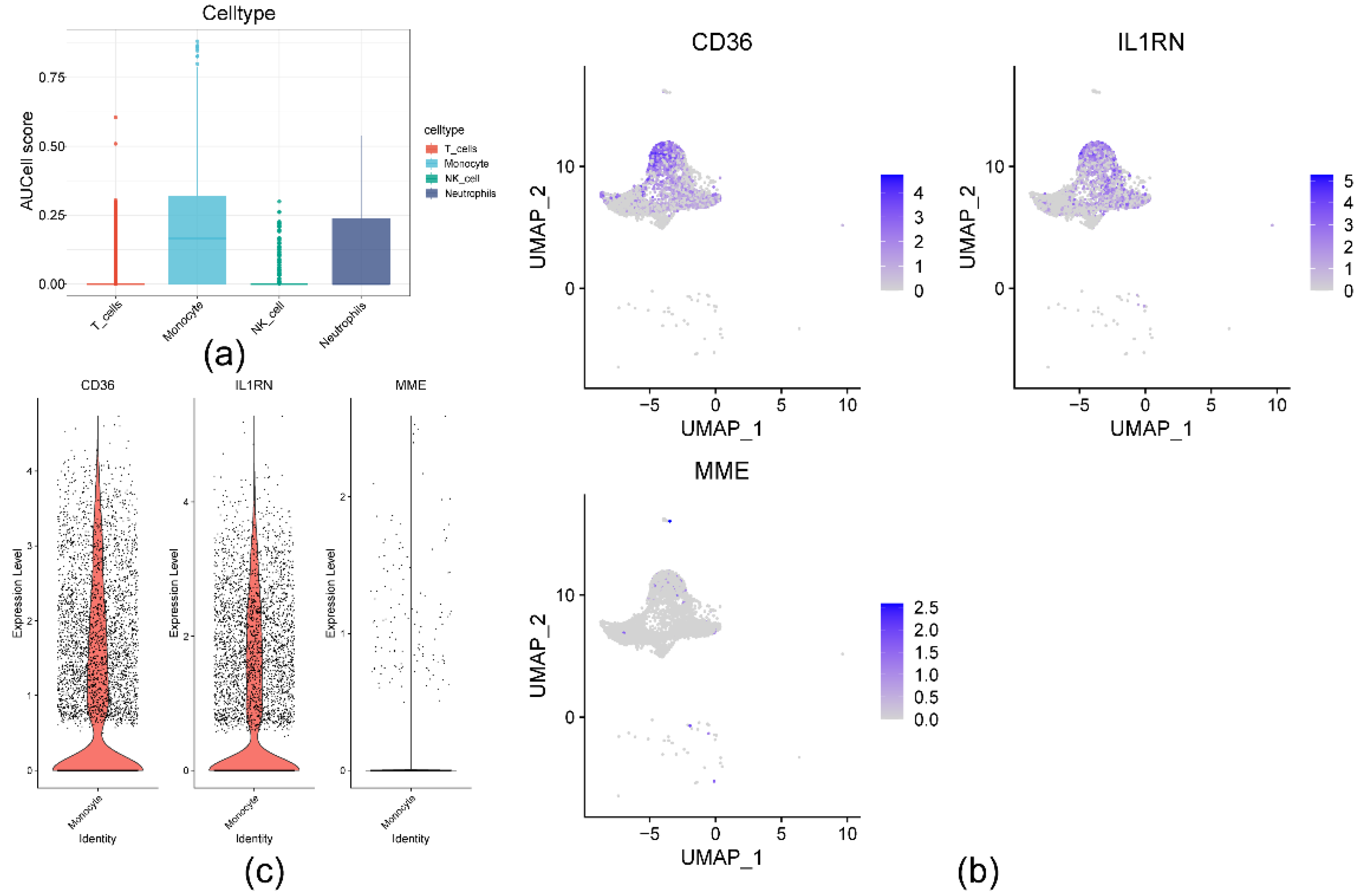

2.7. Cellular- and transcriptome-level verification of CD36, IL1RN, and MME expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data extraction

4.2. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network analysis (WGCNA)

4.3. Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-Seq) analysis

4.4. Differential expression analysis

4.5. MR analysis between DEGs1 and AS

4.6. Biomarker identification

4.7. Artificial neural network (ANN) and subcellular localization analysis

4.8. Biomarker enrichment and immune infiltration analyses

4.9. Regulatory network construction and drug prediction for biomarkers

4.10. Validation of biomarker expression

4.11. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Welsh, P.; Grassia, G.; Botha, S.; Sattar, N.; Maffia, P. Targeting Inflammation to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Realistic Clinical Prospect? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 3898–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The Changing Landscape of Atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.A.; Fernandez, D.M.; Giannarelli, C. Single Cell Analyses to Understand the Immune Continuum in Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2021, 330, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäck, M.; Yurdagul, A.; Tabas, I.; Öörni, K.; Kovanen, P.T. Inflammation and Its Resolution in Atherosclerosis: Mediators and Therapeutic Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, J.; Miyamoto, S.; Sadoshima, J. Mitophagy as a Protective Mechanism against Myocardial Stress. Compr. Physiol. 2017, 7, 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; Perry, J.B.; Allen, M.E.; Sabbah, H.N.; Stauffer, B.L.; Shaikh, S.R.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Colucci, W.S.; Butler, J.; Voors, A.A.; et al. Expert Consensus Document: Mitochondrial Function as a Therapeutic Target in Heart Failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Crisosto, C.; Pennanen, C.; Vasquez-Trincado, C.; Morales, P.E.; Bravo-Sagua, R.; Quest, A.F.G.; Chiong, M.; Lavandero, S. Sarcoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Communication in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonora, M.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Sinclair, D.A.; Kroemer, G.; Pinton, P.; Galluzzi, L. Targeting Mitochondria for Cardiovascular Disorders: Therapeutic Potential and Obstacles. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Chen, G.; Li, W.; Kepp, O.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q. Mitophagy, Mitochondrial Homeostasis, and Cell Fate. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shen, J.; Ran, Z. Emerging Views of Mitophagy in Immunity and Autoimmune Diseases. Autophagy 2020, 16, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qin, W.; Li, L.; Wu, P.; Wei, D. Mitophagy: Critical Role in Atherosclerosis Progression. DNA Cell Biol. 2022, 41, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Stein, M.B.; Klimentidis, Y.C.; Wang, M.-J.; Koenen, K.C.; Smoller, J.W. ; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Assessment of Bidirectional Relationships Between Physical Activity and Depression Among Adults: A 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yifan, C.; Fan, Y.; Jun, P. Visualization of Cardiovascular Development, Physiology and Disease at the Single-Cell Level: Opportunities and Future Challenges. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 142, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, W.; Li, H.; Guo, M.; Yang, L.; Lu, B.; Yu, B.; Fan, G.; Gao, Q.; et al. New Classification of Macrophages in Plaques: A Revolution. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2020, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey Smith, G.; Hemani, G. Mendelian Randomization: Genetic Anchors for Causal Inference in Epidemiological Studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, R89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Zhu, T.; Fu, Y.; Cheongi, I.H.; Yi, K.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Causal Relationships of Excessive Daytime Napping with Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Sleep 2023, 46, zsac257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study of Atherosclerosis and Dementia. iScience 2023, 26, 108325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wheeler, E.; Pietzner, M.; Andlauer, T.F.M.; Yau, M.S.; Hartley, A.E.; Brumpton, B.M.; Rasheed, H.; Kemp, J.P.; Frysz, M.; et al. Lowering of Circulating Sclerostin May Increase Risk of Atherosclerosis and Its Risk Factors: Evidence From a Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis Followed by Mendelian Randomization. Arthritis Rheumatol. Hoboken NJ 2023, 75, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhou, H.; Lv, D.; Lu, L.; Huang, S.; Tang, M.; Zhong, J.; et al. PINK1/Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy Promotes Apelin-13-Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation by AMPKα and Exacerbates Atherosclerotic Lesions. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8668–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouton, A.J.; Li, X.; Hall, M.E.; Hall, J.E. Obesity, Hypertension, and Cardiac Dysfunction: Novel Roles of Immunometabolism in Macrophage Activation and Inflammation. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Peng, Y.; Hang, W.; Nie, J.; Zhou, N.; Wang, D.W. The Role of CD36 in Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, W.; Silverstein, R.L. CD36, a Signaling Receptor and Fatty Acid Transporter That Regulates Immune Cell Metabolism and Fate. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219, e20211314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.M. CD36, a Scavenger Receptor Implicated in Atherosclerosis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2014, 46, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, C.A. Overview of the IL-1 Family in Innate Inflammation and Acquired Immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Z.; Yang, S. Integrating the Characteristic Genes of Macrophage Pseudotime Analysis in Single-Cell RNA-Seq to Construct a Prediction Model of Atherosclerosis. Aging 2023, 15, 6361–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, L.; Zhan, Y.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, X.; Guan, X.-Y.; Li, Y. Membrane Metalloendopeptidase (MME) Suppresses Metastasis of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) by Inhibiting FAK-RhoA Signaling Axis. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.-B.; Shan, M.-J.; Qiu, Y.; Qi, R.; Yu, Z.-M.; Guo, P.; Di, C.-Y.; Gong, T. TPM2 as a Potential Predictive Biomarker for Atherosclerosis. Aging 2019, 11, 6960–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, X.; Yu, Z.; Yang, X.; Chen, J. Protective Effect of Rivaroxaban on Arteriosclerosis Obliterans in Rats through Modulation of the Toll-like Receptor 4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saigusa, R.; Winkels, H.; Ley, K. T Cell Subsets and Functions in Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yue, P.; Lu, T.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Role of Lysosomes in Physiological Activities, Diseases, and Therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol.J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.C.; Bartlett, J.J.; Pulinilkunnil, T. Lysosomal Biology and Function: Modern View of Cellular Debris Bin. Cells 2020, 9, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévy, P.; Kohler, M.; McNicholas, W.T.; Barbé, F.; McEvoy, R.D.; Somers, V.K.; Lavie, L.; Pépin, J.-L. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2015, 1, 15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, A.; Argulian, E.; Leipsic, J.; Newby, D.E.; Narula, J. From Subclinical Atherosclerosis to Plaque Progression and Acute Coronary Events: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1608–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baragetti, A.; Bonacina, F.; Catapano, A.L.; Norata, G.D. Effect of Lipids and Lipoproteins on Hematopoietic Cell Metabolism and Commitment in Atherosclerosis. Immunometabolism 2021, 3, e210014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahrendorf, M.; Swirski, F.K. Lifestyle Effects on Hematopoiesis and Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Fang, J.; Wang, J.-J.; Shao, X.; Xu, S.-W.; Liu, P.-Q.; Ye, W.-C.; Liu, Z.-P. Regulation of Toll-like Receptor (TLR) Signaling Pathways in Atherosclerosis: From Mechanisms to Targeted Therapeutics. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 2358–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.H.; Tran, T.T.P.; Truong, D.H.; Nguyen, H.T.; Pham, T.T.; Yong, C.S.; Kim, J.O. Toll-like Receptor-Targeted Particles: A Paradigm to Manipulate the Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2019, 94, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Tian, Z.; Shen, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zou, J.; Liang, J. CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout in Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells Reveals a pro-Inflammatory Role of TLR2. Cell Biol. Int. 2018, 42, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, T.; Du, Y.; Xing, C.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, R.-F. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling and Its Role in Cell-Mediated Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 812774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, N.M.; Joachim, S.M.; Smita, S.; Callahan, D.; Elsner, R.A.; Conter, L.J.; Chikina, M.; Farber, D.L.; Weisel, F.J.; Shlomchik, M.J. Surface Phenotypes of Naive and Memory B Cells in Mouse and Human Tissues. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.-J.; Gao, K.-Q.; Zhao, M. Epigenetic Regulation in Monocyte/Macrophage: A Key Player during Atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2017, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, S.; Zernecke, A. CD8+ T Cells in Atherosclerosis. Cells 2020, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depuydt, M.A.C.; Prange, K.H.M.; Slenders, L.; Örd, T.; Elbersen, D.; Boltjes, A.; de Jager, S.C.A.; Asselbergs, F.W.; de Borst, G.J.; Aavik, E.; et al. Microanatomy of the Human Atherosclerotic Plaque by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1437–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palano, M.T.; Cucchiara, M.; Gallazzi, M.; Riccio, F.; Mortara, L.; Gensini, G.F.; Spinetti, G.; Ambrosio, G.; Bruno, A. When a Friend Becomes Your Enemy: Natural Killer Cells in Atherosclerosis and Atherosclerosis-Associated Risk Factors. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 798155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profumo, E.; Maggi, E.; Arese, M.; Di Cristofano, C.; Salvati, B.; Saso, L.; Businaro, R.; Buttari, B. Neuropeptide Y Promotes Human M2 Macrophage Polarization and Enhances P62/SQSTM1-Dependent Autophagy and NRF2 Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Changes in Transcriptome of Macrophages in Atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, E.; Berger, H.M.; Brandl, W.T.; Strutz, J.; Hirschmugl, B.; Simovic, V.; Tam-Ammersdorfer, C.; Cvitic, S.; Hiden, U. Maternal Overweight Downregulates MME (Neprilysin) in Feto-Placental Endothelial Cells and in Cord Blood. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Li, C.; Shu, K.; Chen, W.; Cai, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W. Membrane Metalloendopeptidase (MME) Is Positively Correlated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and May Inhibit the Occurrence of Breast Cancer. PloS One 2023, 18, e0289960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-Y.; Gao, Z.-X.; Mao, Z.-H.; Liu, D.-W.; Liu, Z.-S.; Wu, P. Identification of ULK1 as a Novel Mitophagy-Related Gene in Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1079465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänzelmann, S.; Castelo, R.; Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene Set Variation Analysis for Microarray and RNA-Seq Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, E.K.; Zhang, D.; Reynolds, R.H.; Garcia-Ruiz, S.; Ryten, M. Ggtranscript: An R Package for the Visualization and Interpretation of Transcript Isoforms Using Ggplot2. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2022, 38, 3844–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex Heatmaps Reveal Patterns and Correlations in Multidimensional Genomic Data. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Hao, S.; Andersen-Nissen, E.; Mauck, W.M.; Zheng, S.; Butler, A.; Lee, M.J.; Wilk, A.J.; Darby, C.; Zager, M.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Multimodal Single-Cell Data. Cell 2021, 184, 3573–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, D.; Looney, A.P.; Liu, L.; Wu, E.; Fong, V.; Hsu, A.; Chak, S.; Naikawadi, R.P.; Wolters, P.J.; Abate, A.R.; et al. Reference-Based Analysis of Lung Single-Cell Sequencing Reveals a Transitional Profibrotic Macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemani, G.; Zheng, J.; Elsworth, B.; Wade, K.H.; Haberland, V.; Baird, D.; Laurin, C.; Burgess, S.; Bowden, J.; Langdon, R.; et al. The MR-Base Platform Supports Systematic Causal Inference across the Human Phenome. eLife 2018, 7, e34408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Tian, Y.; Si, H.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Sun, K.; Wu, L.; et al. Genetic Causal Association between Iron Status and Osteoarthritis: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.-J.; Ma, L.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.; Hanes, L.; Altepeter, T.; Lee, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y. Model-Informed Approach Supporting Approval of Adalimumab (HUMIRA) in Pediatric Patients with Ulcerative Colitis from a Regulatory Perspective. AAPS J. 2022, 24, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Nie, F.; Kang, J.; Chen, W. mRNALocater: Enhance the Prediction Accuracy of Eukaryotic mRNA Subcellular Localization by Using Model Fusion Strategy. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2021, 29, 2617–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes among Gene Clusters. Omics J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru, Y.; Kechris, K.J.; Tabakoff, B.; Hoffman, P.; Radcliffe, R.A.; Bowler, R.; Mahaffey, S.; Rossi, S.; Calin, G.A.; Bemis, L.; et al. The multiMiR R Package and Database: Integration of microRNA-Target Interactions along with Their Disease and Drug Associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibar, S.; González-Blas, C.B.; Moerman, T.; Huynh-Thu, V.A.; Imrichova, H.; Hulselmans, G.; Rambow, F.; Marine, J.-C.; Geurts, P.; Aerts, J.; et al. SCENIC: Single-Cell Regulatory Network Inference and Clustering. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ENSEMBL | x | id.outcome | outcome | exposure | method | Q | Q_df | Q_pval | method2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000102575 | ACP5 | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000102575 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000102575 | Inverse variance weighted | 1.621829961 | 4 | 0.805 | IVW(fix) |

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000135218 | CD36 | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000135218 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000135218 | Inverse variance weighted | 5.673808854 | 9 | 0.772 | IVW(fix) |

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000136689 | IL1RN | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000136689 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000136689 | Inverse variance weighted | 2.016603369 | 6 | 0.918 | IVW(fix) |

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000196549 | MME | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000196549 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000196549 | Inverse variance weighted | 12.76861245 | 6 | 0.047 | IVW |

| ENSEMBL | x | id.outcome | outcome | exposure | egger_intercept | Se | pval | judge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000102575 | ACP5 | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000102575 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000102575 | 4.39E-05 | 0.000351124 | 0.908487986 | NO |

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000135218 | CD36 | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000135218 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000135218 | 9.70E-05 | 0.000289626 | 0.746417041 | NO |

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000136689 | IL1RN | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000136689 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000136689 | 2.87E-05 | 0.000615668 | 0.964587868 | NO |

| eqtl-a-ENSG00000196549 | MME | ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | Coronary atherosclerosis || id:ukb-d-I9_CORATHER | ENSG00000196549 || id:eqtl-a-ENSG00000196549 | 0.000101792 | 0.000991142 | 0.922191498 | NO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).