1. Introduction

The emergence of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, in late 2019 precipitated an unprecedented global pandemic, leading to a multitude of clinical presentations in affected individuals. While substantial progress has been made in understanding the acute phase of COVID-19, the attention is increasingly shifting towards the long-term consequences experienced by survivors of the disease.

Post-COVID syndrome is a condition that affects some individuals who have recovered from COVID-19, characterized by persistent symptoms that last for weeks or months after the acute illness has resolved. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of post-COVID syndrome varies widely across studies, ranging from 4% to 80% of individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 [

1]. The symptoms of post-COVID syndrome can be diverse and may include fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, cough, palpitations, joint and muscle pain, headache, loss of taste or smell, gastrointestinal symptoms, skin rashes, depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment, among others. [

1,

2]

Post-COVID syndrome lacks a universally accepted definition, leading to variability in estimated prevalence and symptom duration [

1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines post-COVID syndrome (PCS) as the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least 2 months with no other explanation [

2]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK defines post-COVID syndrome as signs and symptoms that develop during or following an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis [

3]. It can also occur in people who were never hospitalized for their initial COVID-19 infection [

4].

Extensive research is ongoing in this important area; however, several lacunae still exist. Short follow up, lack of control group, small sample sizes and inadequate representation of mild to moderate severity disease that comprises majority of post-COVID patients are major issues in available literature.

In this study, we aim to shed light on the multifaceted nature of post-COVID-19 syndrome including its true burden and trends over a one year follow up period.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting and Data Sources

A prospective cohort study was conducted in Wayanad district, in the northeastern region of Kerala state with two groups of participants - an exposure group and control group. Exposure group participants were patients who have recovered from COVID-19 either as inpatients admitted to major hospitals treating COVID-19 patients or outpatients, and non-hospitalized patients at the community level. The scope of the study covered patients treated for COVID-19 in both public and private hospitals, as well as those who were treated outside of the hospital settings in the community.

2.2. Study Population and Sampling Technique

The exposure group participants were selected randomly from COVID-19 positive patients who were admitted at various COVID treatment centers in Wayanad and from outpatients and home-isolated cases under the care areas of Wayanad district health and Dr. Moopen’s Medical College, a tertiary care teaching hospital catering this district. A stratified random sampling proportionate to population was employed to ensure representation of individuals of all taluks in Wayanad. The control group participants were also selected randomly from persons admitted to hospitals without a diagnosis of COVID-19 and outpatients with negative RT-PCR or antigen test as well as healthy adults from field areas of district health department and Dr. Moopen’s Medical College using stratified random sampling.

2.3. Sample Size

Since post COVID syndrome includes several symptoms and abnormalities, we used fatigue which is the commonest feature reported in most studies. Considering that fatigue is likely to be present in 15% of post COVID patients (based on several studies) compared to 7% in the general population, assuming an alpha error of 5% and power of 80%, we calculated that 265 participants would be needed in each group (total of 530). Considering the chances of drop out we recruited 322 participants in study group and 318 participants in control group. However, there was only less than 8% drop out in the whole study resulting in the final sample size of 596 participants.

2.4. Variables at Baseline from the Exposure Cohort

We collected general demographic details, COVID-19 disease category at diagnosis, details of admission, condition at the time of discharge (in hospitalized participants) and COVID-19 vaccination status. Data regarding comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease) were also collected.

2.5. Outcome Variables

Post-COVID syndrome was defined as per the most acceptable definition used currently - symptoms developing during or after COVID-19 infection and lasting beyond 3 months (12 weeks) from first symptom onset in the absence of an alternative etiology and lasting at least 2 months. Any persistent or new symptoms, readmissions and death were determined to quantify post-COVID syndrome and other outcomes.

2.6. Data Collection Procedure

Data was collected by direct interviews using EpiCollect5, in a predesigned format by trained field workers using tablets. Study variables were collected along with measurement of blood pressure (using digital BP apparatus), blood sugar (using glucometer) and oxygen saturation using pulse oximeter (resting and after 6-minute walk test in those with normal resting saturation) by field workers at 6-, 9- and 12-months following recruitment.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Confidentiality of data was ensured, and all data linked to participant identity was coded and stored in password protected data base accessible only to the principal investigator. Institute Ethics Committee approval was obtained (Ref no: IEC/DMWIMS/Oct/2021-013) prior to study initiation.

2.8. Data Analysis

All data were entered in Epicollect5 app and analyzed using the SPSS 25 statistical software. Continuous data were described as mean with standard deviation, minimum and maximum values. Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. We calculated the incidence of post-COVID syndrome using the standard definition. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test and Fischer’s exact test. Mean values were compared using Repeated measures ANOVA (RM ANOVA) between the exposure and control groups. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p<0.05.

3. Results

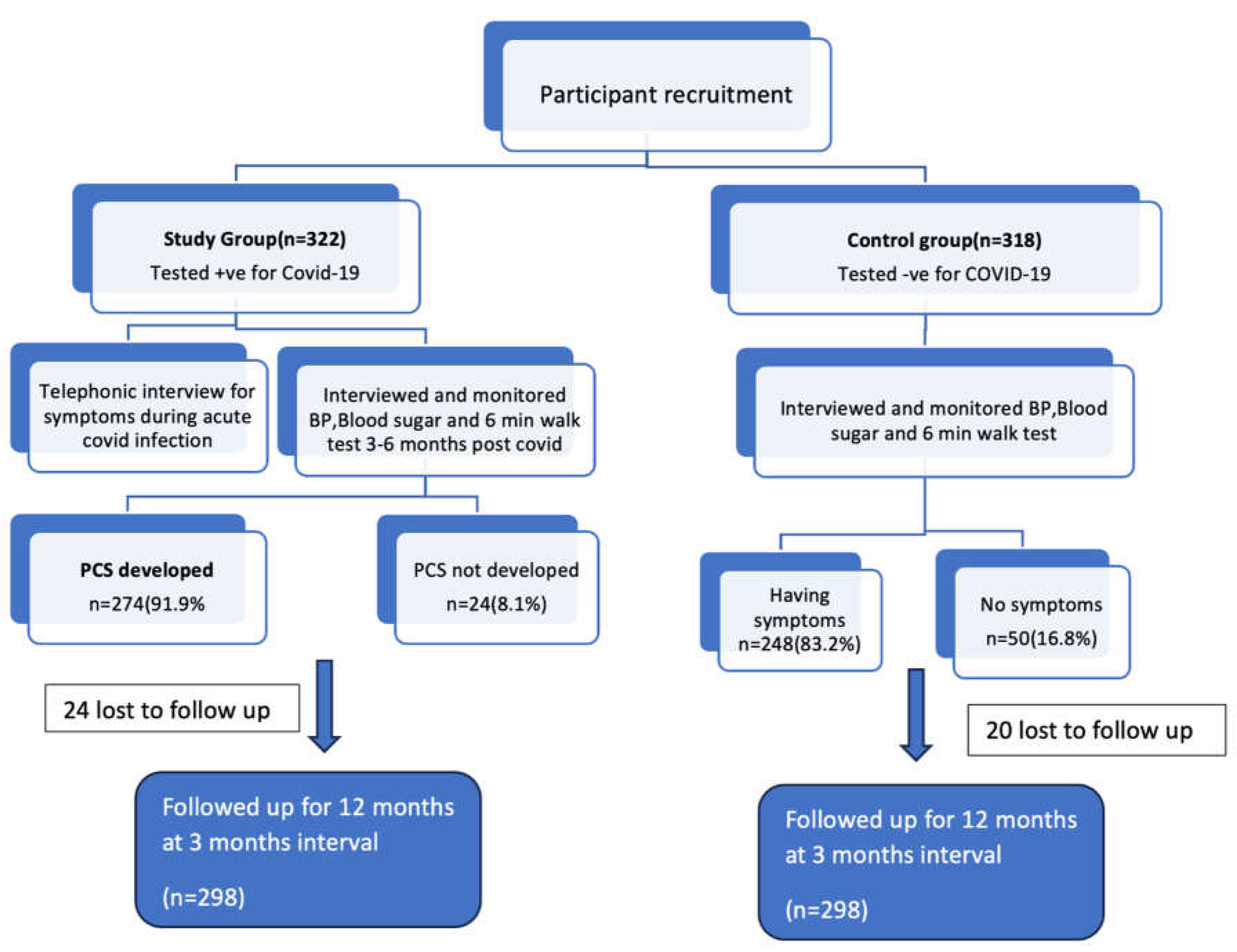

A total of 596 participants were enrolled in the study, of which 298 belonged to the exposure group and remaining to the control group. Details of enrolment of participants in the exposure and control groups are shown in the flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing details of enrolment of participants.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing details of enrolment of participants.

All 298 participants in the exposure group had COVID-19 infection confirmed by RT-PCR or antigen test. 230 (77.2%) of these participants approached private facility for testing. 172 (57.7%) of exposure cohort took home-care isolation, whereas remaining 126 participants required outpatient or inpatient care. Only 11 (3.7%) participants of the exposure cohort were hospitalized. Median duration of hospital stay was 6 days (range: 1 to 17 days) in these patients. Mean age of participants in the exposure group was 39.6 (SD – 11.7) years and in the control group was 37.5 (SD – 12.3) years. The general characteristics of the participants is summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the exposure (n – 298) and control (n – 298) groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the exposure (n – 298) and control (n – 298) groups.

| Categories |

Exposure Group

n (%) |

Control Group

n (%) |

| Gender |

Male |

98(32.9) |

65(21.8) |

| Female |

200(67.1) |

233(78.2) |

| Vaccination status |

Vaccinated |

292(98) |

295(99) |

| Not vaccinated |

6(2) |

3(1) |

| No. of vaccine doses |

0 |

6(2) |

3(1) |

| 1 |

9(3.1) |

8(2.7) |

| 2 |

224(76.7) |

176(59.7) |

| 3 |

59(20.2) |

111(37.6) |

| Comorbidities |

Chronic Kidney disease |

0 |

1(0.3) |

| Chronic liver disease |

2(0.7) |

0 |

| Chronic Heart disease |

5(1.7) |

4(1.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia |

7(2.3) |

3(1) |

| Chronic Lung Disease |

8(2.7) |

3(1) |

| Thyroid dysfunction |

16(5.4) |

7(2.3) |

| Diabetes |

20(6.7) |

14(4.7) |

| Hypertension |

25(8.4) |

21(7) |

| Any of the above comorbidities |

69(23.2) |

44(14.8) |

Among the exposure group only 24 (8.1%) regained pre-COVID health status at 6 months. Of the 298 participants in the exposure cohort, 274 (91.9%) had various symptoms (new or persistent) in the first 6 months after acute COVID infection compared to 248 (83.2%) participants in the control cohort (p = 0.001). As per definition, incidence of post-COVID syndrome was 91.9%.

Symptoms like depressed mood, memory problems, anxiety, hair loss and shortness of breath were more prominent after 6 months of acute COVID infection compared to baseline. While proportion of participants with various symptoms reduced over time from baseline to 12 months, memory problems remained higher at end of 12 months (table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of clinical manifestations over a period of 12 months in the exposure group (n=298).

Table 2.

Prevalence of clinical manifestations over a period of 12 months in the exposure group (n=298).

| Clinical features |

Acute manifestation

n (%) |

6 months post covid

n (%) |

9 months post covid

n (%) |

12 months post covid

n (%) |

| Depressed mood |

5 (1.7) |

10(3.4) |

4(1.3) |

0 |

| Loss of smell |

91 (30.5) |

37(12.4) |

1(0.3) |

0 |

| Loss of taste |

98 (32.9) |

41(13.8) |

2(0.6) |

3(1.0) |

| Anxiety |

34 (11.4) |

55(18.5) |

24(8.1) |

7(2.3) |

| Reduced sleep |

79 (26.5) |

71(23.8) |

2(0.6) |

13(4.4) |

| Memory problems |

17 (5.7) |

74(24.8) |

55(18.5) |

24(8.1) |

| Headache |

205 (68.8) |

116(38.9) |

72(24.2) |

27(9.1) |

| Hair loss |

46 (15.4) |

141(47.3) |

94(34.3) |

36(12.1) |

| Cough |

185 (62.1) |

144(48.3) |

55(18.5) |

18(6.0) |

| Myalgia |

230 (77.2) |

151(50.7) |

64(21.5) |

28(9.4) |

| Shortness of breath |

116 (38.9) |

158(53.0) |

87(29.2) |

56(18.8) |

| Fatigue |

237 (79.5) |

200(67.11) |

90(30.2) |

65(21.8) |

At 9 months, 12 (4.4%) of the exposure cohort required readmission for post-COVID related problems compared to 4 (1.6%) of the control cohort (p = 0.05).

3.1. Persistence of at Least One Symptom at Follow Up

At 9 months of follow up, 203 (68.1%) exposure group participants had at least one ongoing symptom whereas only 138 (46.3%) control group participants had any of these symptoms (p <0.001). At 12 months of follow up, 138 (42.6%) exposure group participants had ongoing symptoms compared to 78 (26.2%) control group participants (p <0.001); (table 3).

Table 3.

Presence of at least one symptom over a period of 12 months of post-COVID in both groups .

Table 3.

Presence of at least one symptom over a period of 12 months of post-COVID in both groups .

| Follow-up period |

Presence of at least one symptom |

Exposure Group, N = 298,

n (%) |

Control Group, N = 298,

n (%) |

P-value |

| 6 months |

Yes |

274(91.9) |

248(83.2) |

0.001 |

| No |

24(8.1) |

50(16.8) |

| 9 months |

Yes |

203(68.1) |

138(46.3) |

<0.001 |

| No |

95(31.9) |

160(53.7) |

| 12 months |

Yes |

127(42.6) |

78(26.2) |

<0.001 |

| No |

171(57.4) |

220(73.8) |

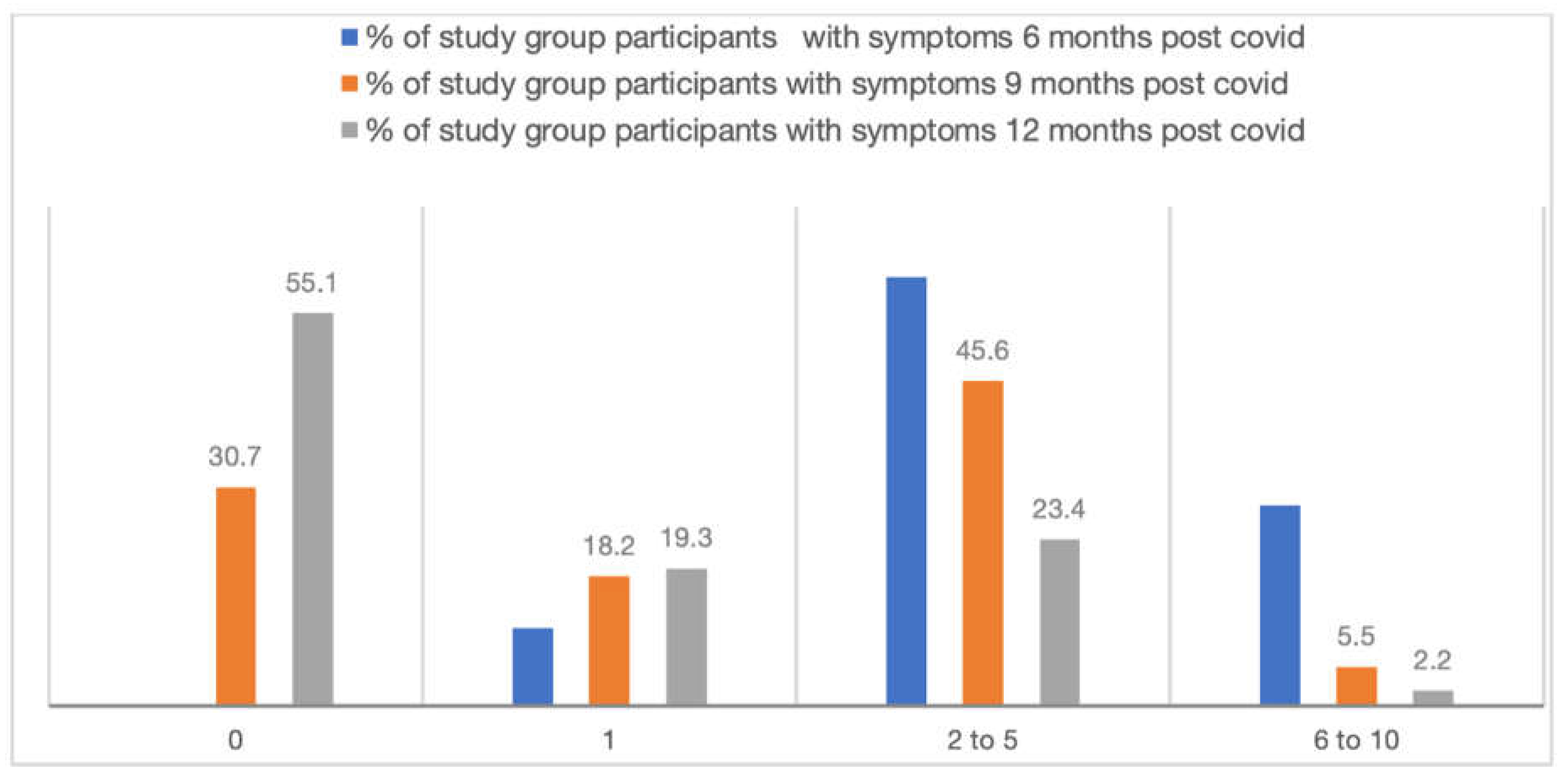

3.2. Number of Symptoms over a Period of 12 Months

After 6 months of acute COVID infection, 28.1% exposure cohort participants had 6 to 10 symptoms whereas it was 8.9% among control cohort. 0.7% of exposure cohort participants had more than 10 symptoms. These differences in number of symptoms experienced by the exposure and control cohorts remained significant even at 9 and 12 months of follow up (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of symptoms over a period of 12 months in the exposure cohort (n=298).

Figure 2.

Number of symptoms over a period of 12 months in the exposure cohort (n=298).

3.3. Effect of COVID 19 on Physical Activity, Blood Pressure, Blood Sugar and Oxygen Saturation

The 6-minute walk distance was 361.3 ± 115.9 m in the exposure group and 380.4 ± 93.9 m in the control group at 6 months follow up (p=0.03). This difference persisted between the groups at 9 months (338.7 ± 131.9 m vs 357.6 ± 100.1 m; p=0.05); however, at 12 months the walk distance was similar in the two groups (p=0.98). The differences in 6-minute walk distance at different follow ups (6, 9 and 12 months) was also statistically significant (p=0.037) with the nadir reduction of walk distance coinciding with 9 months post infection (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

Mean systolic and diastolic BP were statistically significantly higher in the exposure group compared to control group at both 6 and 9 months follow up, while the difference became insignificant by 12 months (table 4). Comparison of cardiometabolic parameters in the exposure group and control group, and trends within the exposure group over the period of 12 months is depicted in tables 4 and 5 respectively.

4. Discussion

This prospective cohort study on the clinical manifestations, risk factors and outcomes of post-COVID syndrome over 12 months in a rural district of Kerala identified that nearly 92% of those who recovered from acute infection suffered from post-COVID syndrome. While fatigue remained the most common post-COVID symptom, its frequency reduced over a period of 12 months from acute infection. COVID resulted in considerable long term cardiorespiratory morbidity as evidenced by statistically significant reductions in 6-minute walk distance and increases in systolic blood pressure.

Unlike other studies conducted in Kerala, this study followed up participants for a longer period of 12 months [

5,

6]. Interestingly this helped identify that post-COVID symptoms persisted even after one year of acute COVID infection. In our study 96.3% of study group were affected with mild or moderate acute COVID infection (may be because of the omicron wave). However, the study is relevant in the sense that even though the COVID infection was mild or moderate, post COVID morbidity appears to last for months. Incidence of some of the symptoms after 6 months, 9 months and 12 months following acute COVID infection is a significant finding. 91.9% of exposure group patients had at least one symptom 6 months post COVID compared to controls. Among the exposure group patients, 68.1% had persistence of at least one symptom after 9 months, and 42.6% had ongoing symptoms even after 12 months.

Like many other studies, prominence of neurological symptoms was seen in this study too, but interestingly, the prevalence increased after 6 months post infection. One study on patients with asymptomatic/mild forms of COVID-19, suggested a possible autoimmune component and association with brain damage [

7]. Loss of smell and taste was noted in more than 10% of post-COVID patients even after 6 months of infection and in lesser proportions after 9 months of infection. Readmission percentage was low as majority of the patients suffered from mild or moderate COVID infection.

A study conducted in Italy found that 87% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 had at least one persistent symptom two months after discharge [

8]. Another study from the UK reported that 10% of patients with mild COVID-19 infection experienced symptoms lasting beyond 12 weeks [

9], while a study in the US found that 31% of outpatients with COVID-19 reported symptoms lasting beyond six months [

7]. However, in our study, a significant proportion of exposure group patients reported persistence of more than 6 symptoms after 6 months of covid infection. After 9 months of post covid, about 6% patients had 6 to 10 symptoms which affected their daily activities, while around 2.5% patients had 6 to 10 symptoms even after one year.

Our study found interesting trajectory of cardiometabolic parameters in post-COVID patients. At 6 months of follow up, the 6-minute walk distance was significantly lower among post-COVID patients compared to controls. Moreover, this distance dropped further at 9 months while still showing statistically significant difference with controls. Interestingly by 12 months, 6-minute walk distance increased and was no longer different from controls. This indicates that the exercise tolerance of post-COVID patients is reduced with maximum impairment at 9 months post infection despite majority of the exposure group participants being mild to moderate disease not requiring hospitalization. It must also be noted that there is also a trend towards recovery or improvement at around one year. Longer follow up of these patients might provide insights as to whether there is complete recovery or return to baseline exercise tolerance. The 6-minute walk distance has been used in many conditions as a marker of disease severity and to monitor progression [

10,

11]. Its use in COVID-19 and post-COVID syndrome has been limited despite its potential as a simple and effective marker of severity of acute disease and progression of chronic effects. The 6-minute walking distance at 6 months in post-COVID patients correlated positively with DLCO and negatively with the HRCT severity score [

12]. A prospective study on 85 patients from Taiwan who were discharged from hospital after COVID-19 found that mean 6-minute walk distance was shorter in those with severe pneumonia at 60 days, although it was not statistically different from those with mild disease and non-severe pneumonia [

13]. Gencer and colleagues reported an improvement in the 6-minute walk distance among post-COVID patients followed up at 3 months compared to 1 month. However, this study included only patients with dyspnea [

14]. Some studies followed up patients for longer periods of time to assess the respiratory functions including 6-minute walk test; however, they included only patients who recovered from COVID pneumonia, limiting the generalizability to the large proportion with mild disease [

15]. Wong and colleagues also demonstrated a significant reduction in the 6-minute walk distance among patients who recovered from severe COVID-19 compared to those with mild disease [

16], but unlike our study, there was no further follow up of these patients to determine trends over time.

A similar trend was noted for changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressures as well. Post-COVID patients had higher systolic and diastolic BP compared to controls at 6 and 9 months follow up. The absolute mean differences between exposure and control groups in systolic BP were around 5 mmHg and 10 mmHg at 6 and 9 months respectively. Again, like the 6-minute walk test, the BP returned to near baseline levels by 12 months with no significant difference with controls. Further, despite such increases, the mean systolic BP and diastolic remained below 130 mmHg and 80 mmHg respectively till the end of study. Therefore, the clinical significance of the elevations in BP among post-COVID patients compared to controls remains elusive. A systematic review on cardiovascular sequelae in post-COVID syndrome reported significantly higher risk for hypertension in these individuals compared to unaffected persons with an Odds ratio of 1.65 (95% CI 1.55-1.77). However, the absolute changes in blood pressures were not discussed in the meta-analysis [

17]. Most studies included in the review were retrospective or case control studies. The few prospective studies in the review had follow up periods ranging between 3 to 6 months.

The major strength of this study is the inclusion of a control cohort which was also followed up for same duration as the exposure group. Further, the large sample size and minimal loss to follow up add considerable internal validity. To the best of our knowledge this is one of the very few studies from India on post-COVID syndrome that compared exposure and control groups and obtained data through direct interviews and regular follow ups for one year. Besides, majority of patients in the exposure group were out-of-hospital, closely resembling real world COVID-19 situation, making our results more generalizable [

18].

While every effort was made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of findings, it is crucial to acknowledge some limitations of this study. We did not employ any diagnostic testing to confirm the COVID-19 status of control group participants, relying instead on self-reported symptoms and medical history. This reliance on self-reporting introduces the possibility of misclassification and underreporting of COVID-19 cases, potentially leading to an inaccurate representation of the infection status within the recruited control group. Consequently, the lack of laboratory-confirmed testing may have impacted the precision of the study's outcomes, as undetected COVID-19 cases among control group participants could have influenced the observed results. Future research should consider incorporating rigorous diagnostic testing protocols to enhance the reliability of participant recruitment and ensure a more accurate delineation of COVID-19 status among study participants.

5. Conclusions

This large, prospective study that followed up patients who recovered from acute COVID-19 identified significant post-COVID impairments that persist even after one year. The overall incidence of post-COVID syndrome is very high and most patients tend to report reductions in the symptoms and functional impairments by the end of one year. Longer follow up of these patients will provide significant insights to the natural history of the condition and enable development of evidence-based recommendations for screening, follow up and management of the various post-COVID manifestations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: baseline data of controls; table S1: baseline data of exposure group; table S3: follow up 1 data of controls; table S4: follow up 1 data of exposure group; S5: follow up 2 data of controls; table S6: follow up 2 data of exposure group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and S.T.P.; methodology, A.B. and S.T.P.; software, V.K.P.; formal analysis, V.K.P and S.T.P.; investigation, V.K.P.; resources, V.M.C. and S.S.; data curation, V.K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K.P.; writing—review and editing, A.B., S.T.P. and S.S.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, A.B. and V.M.C; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Indian Council of Medical Research vide grant No. ECD/CSTPU/Adhoc/COVID-19/12/2021-22.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Dr. Moopen’s Medical College, Wayanad (IEC/DMWIMS/Oct/2021-013 and 07/10/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the field staff (Merlin Sebastian, Ashwini Krishna, Remya John and Prisca Susan Beam) for collecting the data at community level. We also thank the office of District Medical Officer, Wayanad for providing permission to conduct the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| HRCT |

High-Resolution Computed Tomography |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| DLCO |

Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Carbon Monoxide |

References

- Nalbandian, A. , Sehgal, K., Gupta, A., Madhavan, M. V., McGroder, C., Stevens, J. S., Cook, J. R., Nordvig, A. S., Shalev, D., Sehrawat, T. S., Ahluwalia, N., Bikdeli, B., Dietz, D., Der-Nigoghossian, C., Liyanage-Don, N., Rosner, G. F., Bernstein, E. J., Mohan, S., Beckley, A. A., … Wan, E. Y. (2021). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine, 27(4), 601–615. Top of Form. [CrossRef]

- Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition.

- Guideline COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 (nice.org.

- Soriano, J. B. , Murthy, S., Marshall, J. C., Relan, P., Diaz, J. V., & WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. (2022). A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 22(4), e102–e107. [CrossRef]

- Anjana, N. N. , Annie, T., Siba, S., Meenu, M., Chintha, S., & Anish, T. N. (2021). Manifestations and risk factors of post COVID syndrome among COVID-19 patients presented with minimal symptoms – A study from Kerala, India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 10(11), 4023. [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi PR, Siji VS, Gopan K, Gopinath S, Nair AS. Persistence of symptoms after Covid-19 infection in Kerala. Natl Med J India 2022;35:156–8.

- Tenforde, M. W. , Kim, S. S., Lindsell, C. J., Billig Rose, E., Shapiro, N. I., Files, D. C., Gibbs, K. W., Erickson, H. L., Steingrub, J. S., Smithline, H. A., Gong, M. N., Aboodi, M. S., Exline, M. C., Henning, D. J., Wilson, J. G., Khan, A., Qadir, N., Brown, S. M., Peltan, I. D., … IVY Network Investigators. (2020). Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network—United States, March-20. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(30), 993–998. 20 June. [CrossRef]

- Carfì, A. , Bernabei, R., Landi, F., & Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. (2020). Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA, 324(6), 603–605. [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C. H. , Murray, B., Varsavsky, T., Graham, M. S., Penfold, R. S., Bowyer, R. C., Pujol, J. C., Klaser, K., Antonelli, M., Canas, L. S., Molteni, E., Modat, M., Jorge Cardoso, M., May, A., Ganesh, S., Davies, R., Nguyen, L. H., Drew, D. A., Astley, C. M., … Steves, C. J. (2021). Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nature Medicine, 27(4), 626–631. [CrossRef]

- Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, Puhan MA, Pepin V, Saey D, McCormack MC, Carlin BW, Sciurba FC, Pitta F, Wanger J, MacIntyre N, Kaminsky DA, Culver BH, Revill SM, Hernandes NA, Andrianopoulos V, Camillo CA, Mitchell KE, Lee AL, Hill CJ, Singh SJ. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014 Dec;44(6):1428-46. Epub 2014 Oct 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit R, Vaity C, Mulakavalupil B, Matthew A, Sabnis K, Joshi S. Unmasking Hypoxia in COVID 19 - Six Minute Walk Test. J Assoc Physicians India. 2020 Sep;68(9):50-51. [PubMed]

- Ferioli M, Prediletto I, Bensai S, Betti S, Daniele F, Di Scioscio V, et al. The role of 6MWT in Covid-19 follow up. Eur Respir J. 58(suppl 65):OA4046. [CrossRef]

- Eksombatchai D, Wongsinin T, Phongnarudech T, Thammavaranucupt K, Amornputtisathaporn N, Sungkanuparph S. Pulmonary function and six-minute-walk test in patients after recovery from COVID-19: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021 Sep 2;16(9):e0257040. PMCID: PMC8412277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gencer A, Çalışkaner Özturk B, Atahan E, Gemicioğlu B. Six-minute-walk test follow-up in post-coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Cerrahpaşa Med J. 2024;48(1):19-25.

- Pini L, Montori R, Giordani J, Guerini M, Orzes N, Ciarfaglia M, Arici M, Cappelli C, Piva S, Latronico N, Muiesan ML, Tantucci C. Assessment of respiratory function and exercise tolerance at 4-6 months after COVID-19 infection in patients with pneumonia of different severity. Intern Med J. 2023 Feb;53(2):202-208. Epub 2022 Sep 28. PMCID: PMC9538800. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Alyson & López-Romero, Stephanie & Figueroa-Hurtado, Esperanza & Vazquez-Lopez, Saul & Milne, Kathryn & Ryerson, Christopher & Guenette, Jordan & Cortés-Telles, Arturo. (2021). Predictors of reduced 6-minute walk distance after COVID-19: a cohort study in Mexico. Pulmonology. 27. [CrossRef]

- Huang LW, Li HM, He B, Wang XB, Zhang QZ, Peng WX. Prevalence of cardiovascular symptoms in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2025 Feb 6;23(1):70. PMCID: PMC11803987. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund LC, Hallas J, Nielsen H, Koch A, Mogensen SH, Brun NC, Christiansen CF, Thomsen RW, Pottegård A. Post-acute effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection in individuals not requiring hospital admission: a Danish population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Oct;21(10):1373-1382. Epub 2021 May 10. PMCID: PMC8110209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).