Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The Biological Basis of Some Neuro-Psychiatric Diseases

2. Immunotherapy Used in Neurological Disorders

2.1. The Use of Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) in Treating Neurological Disorders

2.2. How IVIG Works

2.3. Conditions Treated with IVIG

2.4. Conditions Where IVIG Is Not Recommended

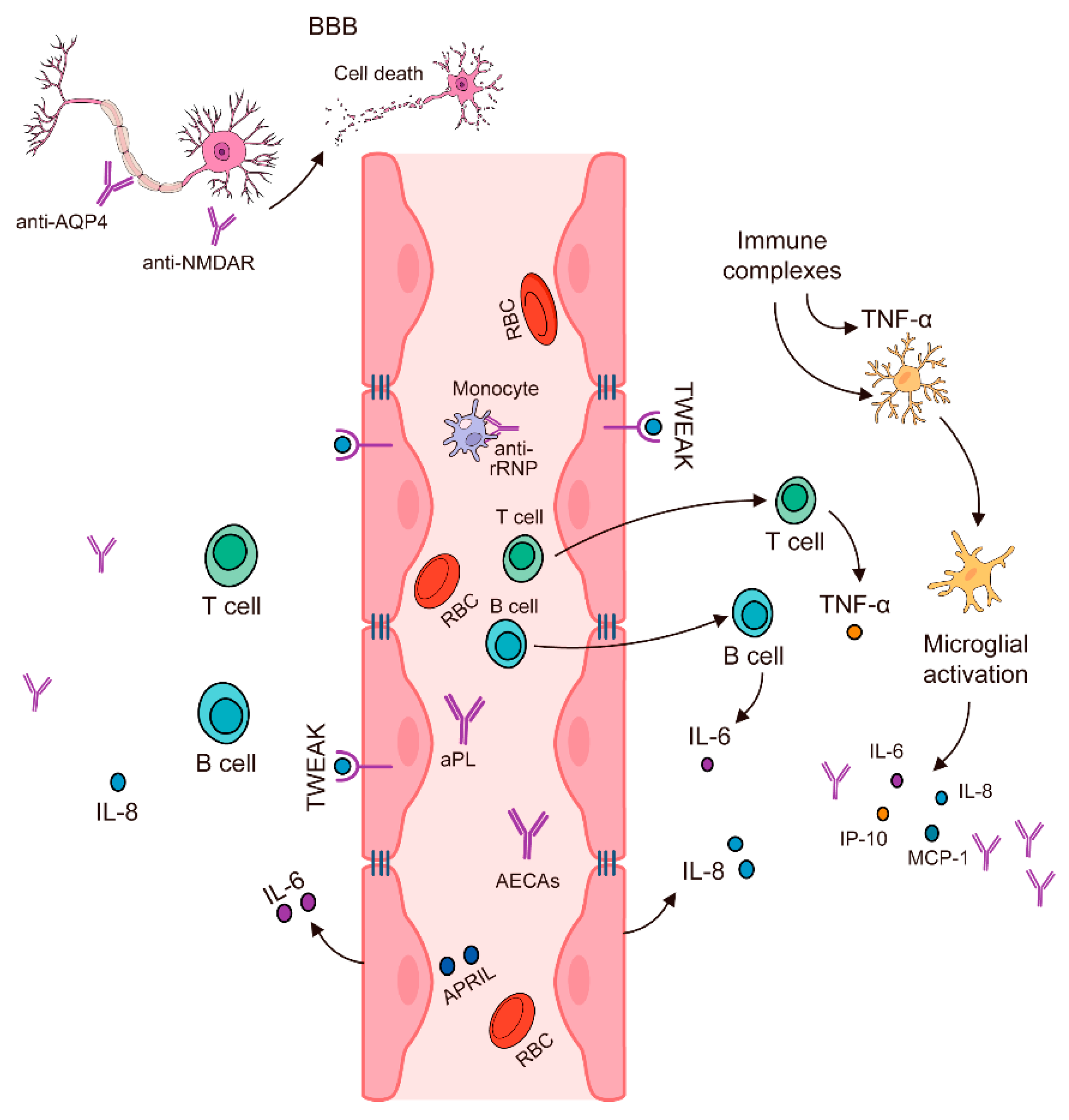

3. Disruption of the Blood-Brain Barrier

4. Cytokines, Antibodies, and Autoimmune Inflammation

6. New approaches in the Treatment of Psychoneuroimmunological Disorders

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kao, Y.C.; Lin, M.I.; Weng, W.C.; Lee, W.T. Neuropsychiatric disorders due to limbic encephalitis: Immunologic aspect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 389. [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, R.O.; Goldberg, H.S.; Ilouz, N.; Singh, P.K.; Shekh-Ahmad, T.; Levite, M. Enigmatic intractable Epilepsy patients have antibodies that bind glutamate receptor peptides, kill neurons, damage the brain, and cause Generalized Tonic Clonic Seizures. J. Neural Transm. 2025, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Husari, K.S.; Dubey, D. Autoimmune epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 685–702.

- Levite, M.; Goldberg, H. Autoimmune epilepsy-novel multidisciplinary analysis, discoveries and insights. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 762743.

- Appenzeller, S.; Andrade, S.D.O.; Bombini, M.F.; Sepresse, S.R.; Reis, F.; França, M.C., Jr. Neuropsychiatric manifestations in primary Sjogren syndrome. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 1071–1081. [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Caraiola, S.; Delcea, C.; Ionescu, R.A.; Jurcut, C.; Badea, C. Self-reported disease severity in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol. Int. 2019, 39, 533–539. [CrossRef]

- Gremke, N.; Printz, M.; Möller, L.; Ehrenberg, C.; Kostev, K.; Kalder, M. Association between anti-seizure medication and the risk of lower urinary tract infection in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022, 135, 108910. [CrossRef]

- Kamyshna, I.I.; Pavlovych, L.B.; Kamyshnyi, A.M. Prediction of the cognitive impairment development in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis and hypothyroidism. Endocr. Regul 2022, 56, 178–189. [CrossRef]

- Manocchio, N.; Magro, V.M.; Massaro, L.; Sorbino, A.; Ljoka, C.; Foti, C. Hashimoto’s Encephalopathy: Clinical Features, Therapeutic Strategies, and Rehabilitation Approaches. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 726.

- Shojima, Y.; Nishioka, K.; Watanabe, M.; Jo, T.; Tanaka, K.; Takashima, H.; Nodayes, K.; Okuma, Y.; Urabe, T.; Yokoyama, K.; et al. Clinical characterization of definite autoimmune limbic encephalitis: A 30-case series. Intern. Med. 2019, 58, 3369–3378. [CrossRef]

- Mangnus, T.J.; Dirckx, M.; Huygen, F.J. Different types of pain in complex regional pain syndrome require a personalized treatment strategy. J. Pain Res. 2023, 4379–4391. [CrossRef]

- Dziadkowiak, E.; Moreira, H.; Buska-Mach, K.; Szmyrka, M.; Budrewicz, S.; Barg, E.; Janik, M.; Pokryszko-Dragan, A. Occult Autoimmune Background for Epilepsy—The Preliminary Study on Antibodies Against Neuronal Surface Antigens. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 660126. [CrossRef]

- Vasilevska, V.; Guest, P.C.; Schlaaff, K.; Incesoy, E.I.; Prüss, H.; Steiner, J. Potential cross-links of inflammation with schizophreniform and affective symptoms: A review and outlook on autoimmune encephalitis and COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 729868. [CrossRef]

- Murashko, A.A.; Pavlov, K.A.; Pavlova, O.V.; Gurina, O.I.; Shmukler, A. Antibodies against N-Methyl D-aspartate receptor in psychotic disorders: A systematic review. Neuropsychobiology 2022, 81, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Zádor, F.; Nagy-Grócz, G.; Kekesi, G.; Dvorácskó, S.; Szűcs, E.; Tömböly, C.; Horvath, G.; Benyhe, S.; Vécsei, L. Kynurenines and the endocannabinoid system in schizophrenia: Common points and potential interactions. Molecules 2019, 24, 3709. [CrossRef]

- Howes, O.D.; Bukala, B.R.; Beck, K. Schizophrenia: From neurochemistry to circuits, symptoms and treatments. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 20, 22–35. [CrossRef]

- Kitanosono, H.; Motomura, M.; Tomita, H.; Iwanaga, H.; Iwanaga, N.; Irioka, T.; Shiraishi, H.; Tsujino, A.. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration with lambert-eaton myasthenic syndrome: A report of an effectively treated case and systematic review of Japanese cases. Brain Nerve = Shinkei Kenkyu No Shinpo 2019, 71, 167–174.

- Takamori, M. Myasthenia gravis: From the viewpoint of pathogenicity focusing on acetylcholine receptor clustering, trans-synaptic homeostasis and synaptic stability. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 86. [CrossRef]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Barbosa, O.A.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pandit, B.; Umakanthan, S.; Akpaka, P.E. Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Molecules Involved in Its Imunopathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 747. [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, G.; Crisafulli, S.G.; Baione, V.; Tartaglia, M.; Cortese, A.; Frontoni, M.; Altieri, M.; Pauri, F.; Millefiorini, E.; Conte, A. Early diagnosis of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: Focus on fluid and neurophysiological biomarkers. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 3626–3645. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, S.; Han, J.; Li, S.; Gao, X.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.; Jin, T. Role of toll-like receptors in neuroimmune diseases: Therapeutic targets and problems. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 777606. [CrossRef]

- Bryll, A.; Skrzypek, J.; Krzyściak, W.; Szelągowska, M.; Śmierciak, N.; Kozicz, T.; Popiela, T. Oxidative-antioxidant imbalance and impaired glucose metabolism in schizophrenia. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 384. [CrossRef]

- Gagné, A.M.; Moreau, I.; St-Amour, I.; Marquet, P.; Maziade, M. Retinal function anomalies in young offspring at genetic risk of schizophrenia and mood disorder: The meaning for the illness pathophysiology. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 219, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Slavov, G. Changes in serum cytokine profile and deficit severity in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Folia Medica 2023, 65, 625–630. [CrossRef]

- Velikova, T.; Sekulovski, M.; Bogdanova, S.; Vasilev, G.; Peshevska-Sekulovska, M.; Miteva, D.; Georgiev, T. Intravenous immunoglobulins as immunomodulators in autoimmune diseases and reproductive medicine. Antibodies 2023, 12, 20. [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Moratti, M.; Leonardi, L.; Catelli, A.; Bortolamedi, E.; Filice, E.; Fetta, A.; Fabi, M.; Facchini, E.; Cantarini, M.E.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effect of high-dose immunoglobulins in children: From approved indications to off-label use. Cells 2023, 12, 2417. [CrossRef]

- Manganotti, P.; Garascia, G.; Furlanis, G.; Buoite Stella, A. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) on COVID-19-related neurological disorders over the last 2 years: An up-to-date narrative review. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1159929. [CrossRef]

- Bayry, J.; Ahmed, E.A.; Toscano-Rivero, D.; Vonniessen, N.; Genest, G.; Cohen, C.G.; Dembele, M.; Kaveri, S.V.; Mazer, B.D. Intravenous immunoglobulin: Mechanism of action in autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 1688–1697. [CrossRef]

- Shock, A.; Humphreys, D.; Nimmerjahn, F. Dissecting the mechanism of action of intravenous immunoglobulin in human autoimmune disease: Lessons from therapeutic modalities targeting Fcγ receptors. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 492–500. [CrossRef]

- Ashton, C.; Paramalingam, S.; Stevenson, B.; Brusch, A.; Needham, M. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: A review. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51, 845–852. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Glaubitz, S.; Schmidt, J. Antibody therapies in autoimmune inflammatory myopathies: Promising treatment options. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 911–921. [CrossRef]

- Gandiga, P.C.; Ghetie, D.; Anderson, E.; Aggrawal, R. Intravenous immunoglobulin in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: A practical guide for clinical use. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2023, 25, 152–168. [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, P.; Fernández-Gayol, O.; Comes, G.; Escrig, A.; Giralt, M.; Palmiter, R.D.; Hidalgo, J. Interleukin-6 derived from the central nervous system may influence the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in a cell-dependent manner. Cells 2020, 9, 330. [CrossRef]

- Danieli, M.G.; Antonelli, E.; Auria, S.; Buti, E.; Shoenfeld, Y. Low-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) in different immune-mediated conditions. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103451. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, E.R.; Ruitenberg, M.J. Neuroinflammation after SCI: Current insights and therapeutic potential of intravenous immunoglobulin. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 320–332. [CrossRef]

- Mroué, M.; Bessaguet, F.; Nizou, A.; Richard, L.; Sturtz, F.; Magy, L.; Bourthoumieu, S.; Danigo, A.; Demiot, C. Neuroprotective Effect of Polyvalent Immunoglobulins on Mouse Models of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 139. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhai, W. Can low-dose intravenous immunoglobulin be an alternative to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of children with newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 199. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.H.; Enk, A.H. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in skin autoimmune disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1090. [CrossRef]

- Nadig, P.L.; Joshi, V.; Pilania, R.K.; Kumrah, R.; Kabeerdoss, J.; Sharma, S.; Suri, D.; Rawat, A.; Singh, S.. Intravenous immunoglobulin in Kawasaki disease—Evolution and pathogenic mechanisms. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2338. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, J.F.; Skare, T.L. Rituximab combined with intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune diseases: A systematic review. Adv. Rheumatol. 2025, 65, 1–10.

- N’kaoua, E.; Attarian, S.; Delmont, E.; Campana-Salort, E.; Verschueren, A.; Grapperon, A.-M.; Mestivier, E.; Roche, M. Immunoglobulin shortage: Practice modifications and clinical outcomes in a reference centre. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 178, 616–623. [CrossRef]

- Barthel, C.; Musquer, M.; Veyrac, G.; Bernier, C. Delayed eczematous skin reaction as an adverse drug reaction to immunoglobulin infusions: A case series. In Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie; Elsevier Masson: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 149, pp. 264–270. [CrossRef]

- Ozen, S.; Esenboga, S. Alternative Therapies for Cytokine Storm Syndromes. Cytokine Storm Syndr. 2019, 581–593.

- Kadry, H.; Noorani, B.; Cucullo, L. A blood–brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020, 17, 1–24.

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pooransingh, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Asin-Milan, O.; Akpaka, P.E. Advancements in Immunology and Microbiology Research: A Comprehensive Exploration of Key Areas. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1672. [CrossRef]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Barbosa, O.A.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pandit, B.; Umakanthan, S.; Akpaka, P.E. Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Molecules Involved in Its Imunopathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 747. [CrossRef]

- Wesselingh, R.; Butzkueven, H.; Buzzard, K.; Tarlinton, D.; O’Brien, T.J.; Monif, M. Innate immunity in the central nervous system: A missing piece of the autoimmune encephalitis puzzle? Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2066. [CrossRef]

- Radetz, A.; Groppa, S. White Matter Pathology. In Translational Methods for Multiple Sclerosis Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 29–46.

- Dhaiban, S.; Al-Ani, M.; Elemam, N.M.; Al-Aawad, M.H.; Al-Rawi, Z.; Maghazachi, A.A. Role of peripheral immune cells in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Sci 2021, 3, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bordet, R.; Camu, W.; De Seze, J.; Laplaud, D.A.; Ouallet, J.C.; Thouvenot, E. Mechanism of action of s1p receptor modulators in multiple sclerosis: The double requirement. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 176, 100–112. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Tian, X.; Chen, C.; Ma, L.; Zhou, S.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Y.. The efficacy and safety of fingolimod in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 637–645. [CrossRef]

- Stascheit, F.; Li, L.; Mai, K.; Baum, K.; Siebert, E.; Ruprecht, K. Delayed onset hypophysitis after therapy with daclizumab for multiple sclerosis–A report of two cases. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 351, 577469. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Patsopoulos, N.A. Genetics and functional genomics of multiple sclerosis. In Seminars in Immunopathology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 44, pp. 63–79.

- Cohan, S.L.; Lucassen, E.B.; Romba, M.C.; Linch, S.N. Daclizumab: Mechanisms of action, therapeutic efficacy, adverse events and its uncovering the potential role of innate immune system recruitment as a treatment strategy for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 18. [CrossRef]

- Rothhammer, V., Kenison, J. E., Li, Z., Tjon, E., Takenaka, M. C., Chao, C. C., ... & Quintana, F. J. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation in astrocytes by laquinimod ameliorates autoimmune inflammation in the CNS. Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation, 2021, 8(2), e946. [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, T.; Sandi, D.; Bencsik, K.; Vécsei, L. Kynurenines in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis: Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020, 9, 1564. [CrossRef]

- Comi, G.; Dadon, Y.; Sasson, N.; Steinerman, J.R.; Knappertz, V.; Vollmer, T.L.; Boyko, A.; Vermersch, P.; Ziemssen, T.; Montalban, X.; et al. CONCERTO: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oral laquinimod in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2022, 28, 608–619.

- Ruetsch-Chelli, C.; Bresch, S.; Seitz-Polski, B.; Rosenthal, A.; Desnuelle, C.; Cohen, M.; Brglez, V.; Ticchioni, M.; Lebrun-Frenay, C. Memory B cells predict relapse in rituximab-treated myasthenia gravis. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 938–948. [CrossRef]

- Mantegazza, R.; Antozzi, C. When myasthenia gravis is deemed refractory: Clinical signposts and treatment strategies. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2018, 11, 1756285617749134. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.M.; Baehring, J.M. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: A single institution 10-year case series. J. Neurooncol. 2019, 141, 431–439. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, M.R.; Dalmau, J. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes. Neurol. Clin. 2018, 36, 675–685.

- Mladinich, M.C.; Himmler, G.E.; Conde, J.N.; Gorbunova, E.E.; Schutt, W.R.; Sarkar, S.; Tsirka, S.-A.E.; Kim, H.K.; Mackow, E.R. Age-dependent Powassan virus lethality is linked to glial cell activation and divergent neuroinflammatory cytokine responses in a murine model. J. Virol. 2024, e0056024. [CrossRef]

- Alakhras, N.S.; Zhang, W.; Barros, N.; Sharma, A.; Ropa, J.; Priya, R.; Yang, X.F.; Kaplan, M.H. An IL-23-STAT4 pathway is required for the proinflammatory function of classical dendritic cells during CNS inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2400153121. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Tang, Y.; Gao, T.; Li, C.; Guo, R.; Sun, C.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Chang, T. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with refractory generalized myasthenia gravis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14793. [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; Van Der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, H.; Andlauer, T.F.; Korn, T.; Mühlau, M.; Henningsen, P.; Hemmer, B.; Ploner, M. Fatigue, depression, and pain in multiple sclerosis: How neuroinflammation translates into dysfunctional reward processing and anhedonic symptoms. Mult. Scler. J. 2022, 28, 1020–1027. [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, A.; Li, Y.; Claflin, S.B.; van der Mei, I.; Taylor, B.V. Role of environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2021, 21, 1389–1408. [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, C.; Puthenparampil, M.; Tomas-Ojer, P.; Jelcic, I.; Docampo, M.J.; Planas, R.; Manogaran, P.; Opfer, R.; Wicki, C.; Reindl, M.; et al. T-cell specificity influences disease heterogeneity in multiple sclerosis. Neurol.-Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 8, e1075. [CrossRef]

- Long, H.M.; Meckiff, B.J.; Taylor, G.S. The T-cell response to Epstein-Barr virus–new tricks from an old dog. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2193. [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [CrossRef]

- Deeba, E.; Koptides, D.; Gaglia, E.; Constantinou, A.; Lambrianides, A.; Pantzaris, M.; Krashias, G.; Christodoulou, C. Evaluation of Epstein-Barr virus-specific antibodies in Cypriot multiple sclerosis patients. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 105, 270–275. [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tengvall, K.; Lima, I.B.; Hedström, A.K.; Butt, J.; Brenner, N.; Gyllenberg, A.; Stridh, P.; Khademi, M.; Ernberg, I.; et al. Genetics of immune response to Epstein-Barr virus: Prospects for multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. Brain 2024, 147, 3573–3582. [CrossRef]

- Jog, N.R.; McClain, M.T.; Heinlen, L.D.; Gross, T.; Towner, R.; Guthridge, J.M.; Axtell, R.C.; Pardo, G.; Harley, J.B.; James, J.A. Epstein Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA-1) peptides recognized by adult multiple sclerosis patient sera induce neurologic symptoms in a murine model. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 106, 102332. [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [CrossRef]

- Tengvall, K.; Huang, J.; Hellström, C.; Kammer, P.; Biström, M.; Ayoglu, B.; Bomfim, I.L.; Stridh, P.; Butt, J.; Brenner, N.; et al. Molecular mimicry between Anoctamin 2 and Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 associates with multiple sclerosis risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 16955–16960. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kennedy, P.G.; Dupree, C.; Wang, M.; Lee, C.; Pointon, T.; Langford, T.D.; Graner, M.W.; Yu, X. Antibodies from Multiple Sclerosis Brain Identified Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 1 & 2 Epitopes which Are Recognized by Oligoclonal Bands. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021, 16, 567–580. [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.; Marinho-Dias, J.; Ribeiro, J.; Sousa, H. Epstein-Barr virus strains and variations: Geographic or disease-specific variants? J. Med. Virol. 2017, 89, 373–387. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, O.G.; Bronge, M.; Tengvall, K.; Akpinar, B.; Nilsson, O.B.; Holmgren, E.; Hessa, T.; Gafvelin, G.; Khademi, M.; Alfredsson, L.; et al. Cross-reactive EBNA1 immunity targets alpha-crystallin B and is associated with multiple sclerosis. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg3032. [CrossRef]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.-S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.-S.; Bartley, C.M.; et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- Telford, M.; Hughes, D.A.; Juan, D.; Stoneking, M.; Navarro, A.; Santpere, G. Expanding the geographic characterisation of Epstein–Barr virus variation through gene-based approaches. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1686. [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Quijada, A.; Abudinén, G.; Céspedes, C.; Aguilera, L. Opercular myoclonic-anarthric status (OMASE) secondary to anti-Hu paraneoplastic neurological syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. Rep. 2024, 27, 100703. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Shan, W.; Lv, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Clinical characteristics of anti-GABA-B receptor encephalitis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 403. [CrossRef]

- Tsang-Shan, C.; Ming-Chi, L.; Huang, H.Y.I.; Chin-Wei, H.; Immunity, Ion Channels and Epilepsy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6446.

- Gilligan, M.; McGuigan, C.; McKeon, A. Paraneoplastic neurologic disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 23, 67–82.

- Gilligan, M.; McGuigan, C.; McKeon, A. Autoimmune central nervous system disorders: Antibody testing and its clinical utility. Clin. Biochem. 2024, 126, 110746. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, L.; Shen, S.; Lin, J.-F.; Wang, J.-R.; Zhou, D.; Li, J.-M.; Sima, X. Neurological autoantibody prevalence in chronic epilepsy: Clinical and neuropathologic findings. Seizure: Eur. J. Epilepsy 2024, 115, 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Kothapalli, N.; McKeon, A.; Flanagan, E.P.; Lennon, V.A.; Klein, C.J.; Britton, J.W.; So, E.; Boeve, B.F.; Tillema, J.-M.; et al. Predictors of neural-specific autoantibodies and immunotherapy response in patients with cognitive dysfunction. J. Neuroimmunol. 2018, 323, 62–72. [CrossRef]

- Orozco, E.; Valencia-Sanchez, C.; Britton, J.; Dubey, D.; Flanagan, E.P.; Lopez-Chiriboga, A.S.; Zalewski, N.; Zekeridou, A.; Pittock, S.J.; McKeon, A. Autoimmune encephalitis criteria in clinical practice. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, e200151. [CrossRef]

- Abide, Z.; Nasr, K.S.; Kaddouri, S.; Edderai, M.; Elfenni, J.; Salaheddine, T. Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis: A case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2023, 18, 2704–2706. [CrossRef]

- rozco, E.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.J.; Dubey, D.; Howell, B.; Moutvic, M.; Louis, E.K.S.; McKeon, A. Clinical reasoning: A 43-year-old man with subacute onset of vision disturbances, jaw spasms, and balance and sleep difficulties. Neurology 2022, 99, 387–392. [CrossRef]

- Tisavipat, N.; Chang, B.K.; Ali, F.; Pittock, S.J.; Kammeyer, R.; Declusin, A.; Cohn, S.J.; Flanagan, E.P. Subacute horizontal diplopia, jaw dystonia, and laryngospasm. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 10, e200128. [CrossRef]

- Lana-Peixoto, M.A.; Talim, N. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and anti-MOG syndromes. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 49. [CrossRef]

- Blattner, M.S.; Day, G.S. Sleep disturbances in patients with autoimmune encephalitis. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 28. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.; Waters, P.; Komorowski, L.; Zekeridou, A.; Guo, C.Y.; Mgbachi, V.C.; Probst, C.; Mindorf, S.; Teegen, B.; Gelfand, J.M.; et al. GABA(A) receptor autoimmunity: A multicenter experience. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 6, e552.

- Gravier-Dumonceau, A.; Ameli, R.; Rogemond, V.; Ruiz, A.; Joubert, B.; Muniz-Castrillo, S.; Vogrig, A.; Picard, G.; Ambati, A.; Benaiteau, M.; et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein autoimmunity: A French cohort study. Neurology 2022, 98, e653–e668.

- Flanagan, E.P.; Hinson, S.R.; Lennon, V.A.; Fang, B.; Aksamit, A.J.; Morris, P.P.; Basal, E.; Honorat, J.A.; Alfugham, N.B.; Linnoila, J.J.; et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoglobulin G as biomarker of autoimmune astrocytopathy: Analysis of 102 patients. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 298–309. [CrossRef]

- Guasp, M.; Dalmau, J. Encephalitis associated with antibodies against the NMDA receptor. Med. Clin. 2018, 151, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Budhram, A.; Sharma, M.; Young, G.B. Seizures in anti-hu-associated extra-limbic encephalitis: Characterization of a unique disease manifestation. Epilepsia 2022, 63, e172–e177.

- Liu, M.; Ren, H.; Wang, L.; Fan, S.; Bai, L.; Guan, H. Prognostic and relapsing factors of primary autoimmune cerebellar ataxia: A prospective cohort study. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 1072–1079. [CrossRef]

- Hadjivassiliou, M.; Graus, F.; Honnorat, J.; Jarius, S.; Titulaer, M.; Manto, M.; Hoggard, N.; Sarrigiannis, P.; Mitoma, H. Diagnostic criteria for primary autoimmune cerebellar ataxia-guidelines from an international task force on immune-mediated cerebellar ataxias. Cerebellum 2020, 19, 605–610. [CrossRef]

- Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.L.; Marignier, R.; Kim, H.J.; Brilot, F.; Flanagan, E.P.; Ramanathan, S.; Waters, P.; Tenembaum, S.; Graves, J.S.; et al. Diagnosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: International MOGAD panel proposed criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 268–282. [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Sanchez, C.; Flanagan, E.P. Uncommon inflammatory/immune-related myelopathies. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 361, 577750. [CrossRef]

- Chiriboga, S.L.; Flanagan, E.P. Myelitis and other autoimmune myelopathies. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2021, 27, 62–92. [CrossRef]

- Banks, S.A.; Morris, P.P.; Chen, J.J.; Pittock, S.J.; Sechi, E.; Kunchok, A.; Tillema, J.-M.; Fryer, J.P.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Krecke, K.N.; et al. Brainstem and cerebellar involvement in MOG-IgG-associated disorder versus aquaporin-4-IgG and MS. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 384–390. [CrossRef]

- Ciron, J.; Cobo-Calvo, A.; Audoin, B.; Bourre, B.; Brassat, D.; Cohen, M.; Collongues, N.; Deschamps, R.; Durand-Dubief, F.; Laplaud, D.; et al. Frequency and characteristics of short versus longitudinally extensive myelitis in adults with MOG antibodies: A retrospective multicentric study. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 936–944. [CrossRef]

- Cacciaguerra, L.; Sechi, E.; Rocca, M. A.; Filippi, M.; Pittock, S. J.; & Flanagan, E. P. Neuroimaging features in inflammatory myelopathies: a review. Frontiers in Neurology, 2022, 13, 993645. [CrossRef]

- McKeon, A.; Lesnick, C.; Vorasoot, N.; Buckley, M. W.; Dasari, S.; Flanagan, E. P.; Mills, J.; et al. Utility of protein microarrays for detection of classified and novel antibodies in autoimmune neurologic disease. Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation, 2023, 10(5), e200145. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.; Varas, R.; Godoy-Santín, J.; Valenzuela, R.; Sandoval, P. Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome associated with anti Kelch-like protein-11 antibodies in a young female patient without cancer. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 355, 577570. [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, M.; Mou, D. P.; Zhou, L. Q.; Dong, M. H.; Huang, L.; Wang, W.; Cai, S. B.; You, Y. F.; Shang, K.; Xiao, J.; Wang, D.; Li, C. R.; Hao, Y.; Heming, M.; Wu, L. J.; Meyer Zu Hörste, G.; Dong, C.; Bu, B. T.; Tian, D. S.; … Wang, W. Single-cell analysis of anti-BCMA CAR T cell therapy in patients with central nervous system autoimmunity. Science immunology, 2024, 9(95), eadj9730. [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, J.; Abazovic, D.; Vucetic, D.; Medenica, S. CAR-engineered T cell therapy as an emerging strategy for treating autoimmune diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024; 11:1447147. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. R.; Lyu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; & Yang, L. Frontiers in CAR-T cell therapy for autoimmune diseases. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 2024, 45(9), 839–857. [CrossRef]

| Disease | Autoantibody | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive and affective dysfunctions in autoimmune thyroiditis | Anti-thyroid peroxidase Ab, anti-central nervous system Ab | [8] | ||

| Hashimoto’s encephalopathy (HE) | Anti-α-enolase Ab, anti-thyroid peroxidase Ab |

[8,9] | ||

| Limbic encephalitis multiple sclerosis | Anti-N-methyl D-aspartate-type glutamate receptor Ab | [1,10] | ||

| Complex regional syndrome | Anti-nuclear Ab (ANA), anti-neuronal Ab | [11] | ||

| Idiopathic and symptomatic epilepsies | Neurotropic Abs to NF-200, GFAP, MBP and S100β, and to receptors of neuromediators (glutamate, GABA, dopamine, serotonin and choline-receptors | [12] | ||

| Schizophrenia | Autoantibodies against glutamate, dopamine, acetylcholine and serotonin receptors, and antineuronal antibodies against synaptic biomolecules | [13,14,15,16] | ||

| Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome | Autoantibodies against P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels | [17] | ||

| Myasthenia gravis | Auto-Ab to tyrosine kinase | muscle-specific | [18] | |

| Disease | Cytokine Involved | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus | Elevated interleukin (IL)-17, IL-2, interferon- gamma (IFN-γ), IL-5, basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and IL-15 |

[19] |

| Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis | Elevated IL-17 and INF-gamma and decreased transforming growth factor- beta (TGF-beta 1) levels | [20] |

| Guillain-Barre syndrome | Elevated TNFα and IL-10 | [21] |

| Schizophrenia | Increased interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and TGF-β appear to be state markers, whereas IL-12, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), TNF-α, and soluble IL-2 receptor appear to be trait markers | [22,23] |

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) | IL-17 plays an important role in the inflammatory phase of relapsing- remitting MS | [24] |

| Diseases | References |

|---|---|

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | [25,26,27,28,29] |

| Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy | [25,26,27,28,29] |

| Multiple motor neuropathy | [26,27] |

| Multiple sclerosis | [26,27] |

| Myasthenia gravis | [26,27,28] |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | [27] |

| Diabetic neuropathy | [27] |

| Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome | [27] |

| Opsoclonus-myoclonus | [27] |

| Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections | [27] |

| Polymyositis | [27,30,31,32] |

| Rasmussen’s encephalitis | [27] |

| Multiple sclerosis | [33] |

| Disease | Drug used | Mechanism of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple sclerosis | Oral fingolimod | It Inhibits egress of lymphocytes from lymph nodes and their recirculation | [50,51] |

| Multiple sclerosis | Daclizumab | It is a humanized neutralizing monoclonal antibody against the α-chain of the interleukin-2 receptor |

[52,53,54] |

| Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis | Laquinimod | Modulates adaptive T cell immune responses via its effects on cells of the innate immune system and may not influence T cells directly | [55,56,57] |

| Myasthenia gravis | Rituximab | A chimeric IgG k monoclonal antibody that target CD20 on B cells | [58,59] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | Plasma exchange | Deplete pathogenic autoantibody | [60] |

| Paraneoplastic neurological disorders | IVIG, plasma exchange | Immunomodulator, deplete auto-Ab | [61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).