The primary objective of integrating railway freight into carbon emissions trading markets is leveraging market mechanisms to economically valorize railway freight’s relatively low-carbon intensity, thus simultaneously achieving economic efficiency and environmental sustainability. This section establishes a detailed carbon trading framework tailored specifically to railway freight operations, highlighting the dual approach of emission reduction incentives and freight-rate adjustments through market-driven price discovery mechanisms, which encourage modal shifts toward rail and facilitate effective implementation of the "road-to-rail" policy.

3.1. Necessity of Integrating Railway Freight into Carbon Trading

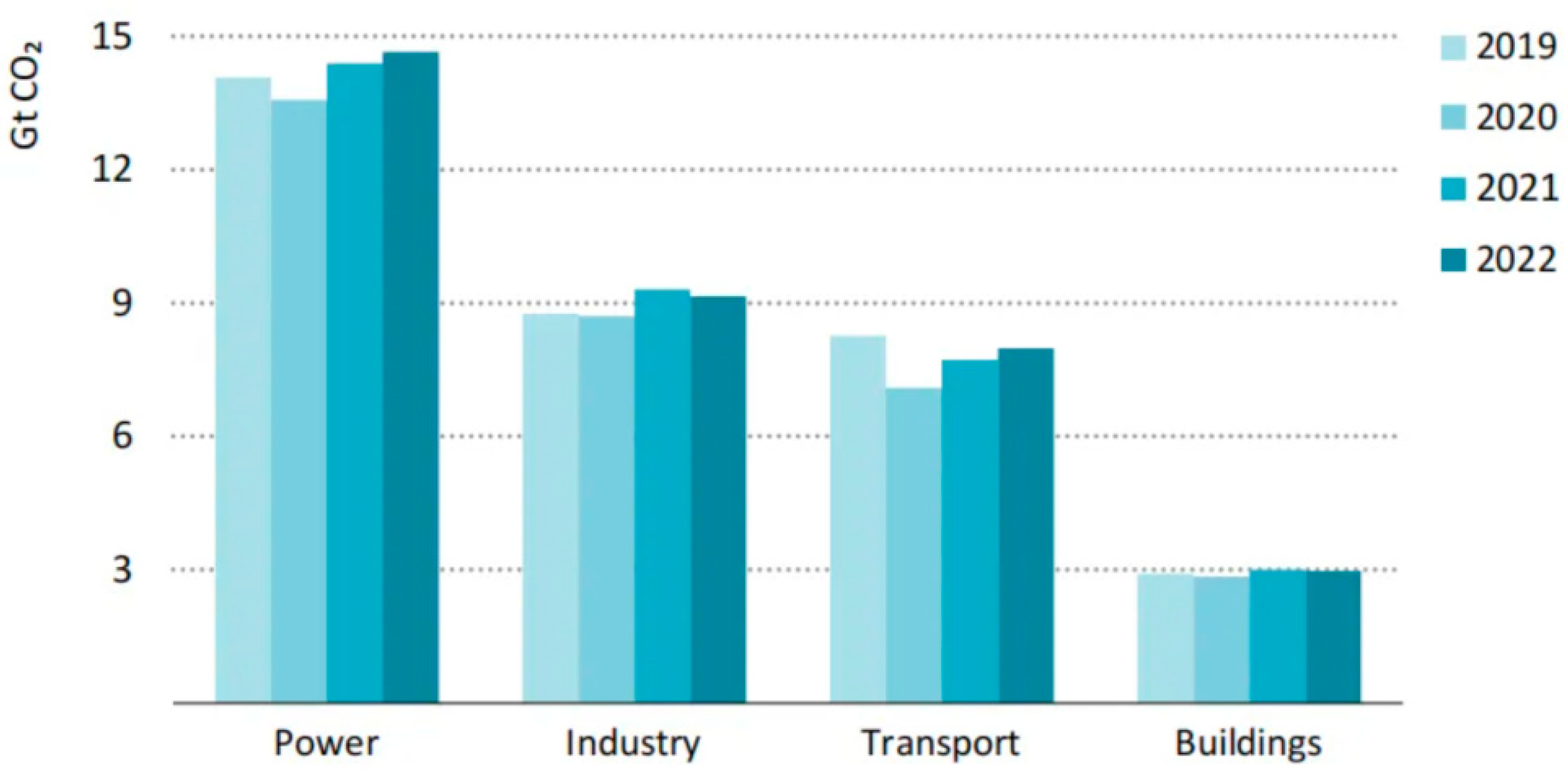

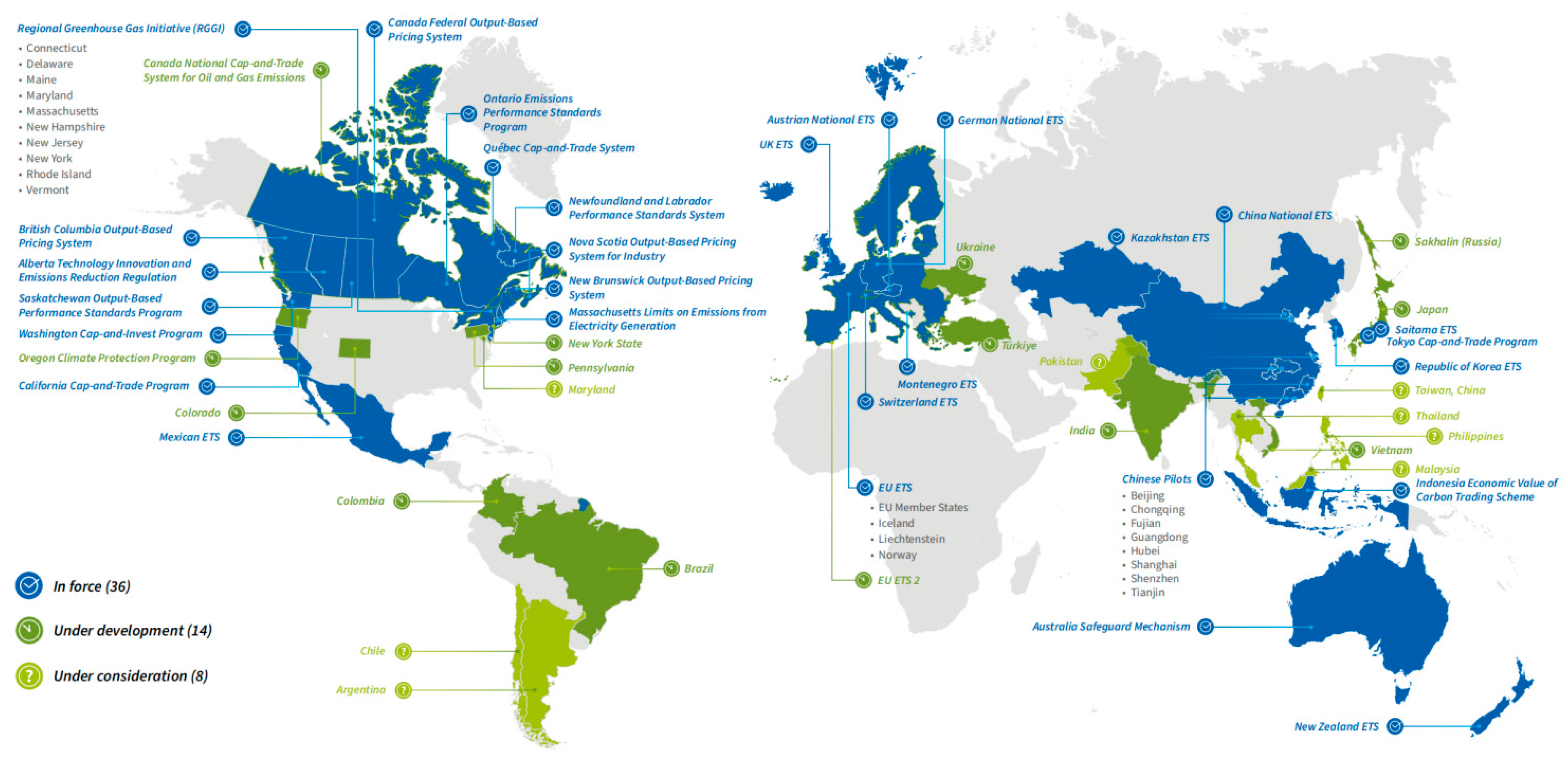

As global carbon trading markets expand, emissions trading has increasingly become a critical economic instrument for facilitating industry-wide low-carbon transitions. As of January 2024, there were 36 carbon emissions trading systems (ETS) in force globally (

Figure 2), including the European Union, the United States, China, Canada, and emerging markets in Asia and Latin America[

20]. International experiences thus underscore both empirical rationale and practical necessity for systematically incorporating China’s railway freight sector into national carbon markets.

Integrating railway freight into carbon trading offers three primary benefits:

1. Optimizing Transport Structure and Modal Shift Facilitation

Carbon markets allocate transport capacities economically, promoting sector-wide low-carbon transformation. Elevated carbon cost for road and air transport magnifies rail freight’s comparative cost advantage. Li et al. (2023) noted China's road transport emissions intensity is approximately 9.5 times higher than rail, with aviation intensity being 88.2 times greater [

21]. A report by the Trades Union Congress (2023) similarly demonstrated European rail freight carbon intensity at only 24% that of road transport [

22]. Thus, carbon markets enhance rail freight’s economic competitiveness, facilitating "road-to-rail" modal shifts, lowering overall logistics costs, and reducing emissions effectively through market-driven mechanisms.

2. Internalizing Environmental Costs and Encouraging Innovation

Carbon trading internalizes emission costs, correcting market failures, incentivizing enterprises to proactively invest in low-carbon technologies and operations [

23]. Railway enterprises can enhance competitiveness through energy-efficiency improvements and innovative operational practices. Multimodal transport systems centered on rail also effectively reduce emissions, with optimized multimodal systems capable of cutting emissions by up to 57% compared to single-mode systems [

24,

25]. Hence, carbon pricing signals and economic incentives within carbon trading markets will encourage railway enterprises to actively pursue technological advancements and innovative operational strategies, significantly reducing their own carbon emissions and providing practical examples for the broader sectoral shift towards low-carbon transportation.

3. Aligning with China's Strategic "Dual-Carbon" Policy

Recent governmental policies explicitly outline strategic objectives for railway participation in carbon markets. Documents such as the "State Council’s Action Plan for Carbon Peaking before 2030" , the "Implementation Plan for Deepening the Implementation of China's 14th Five-Year Plan and 2035 Vision for Railway Development," and the "Implementation Plan for Promoting Low-Carbon Development in the Railway Industry," issued by the Ministry of Transport and the National Railway Administration, clearly stipulate reducing comprehensive energy consumption and CO₂ emissions per unit of railway transportation workload by 10% by 2030 compared to 2020 [

26,

27,

28]. These policy directives further affirm institutional support for integrating railway freight into carbon trading systems.

Thus, integrating railway freight into national carbon trading systems is both theoretically necessary and practically feasible, fully realizing the sector’s inherent low-carbon advantages through market mechanisms and delivering dual economic and environmental benefits.

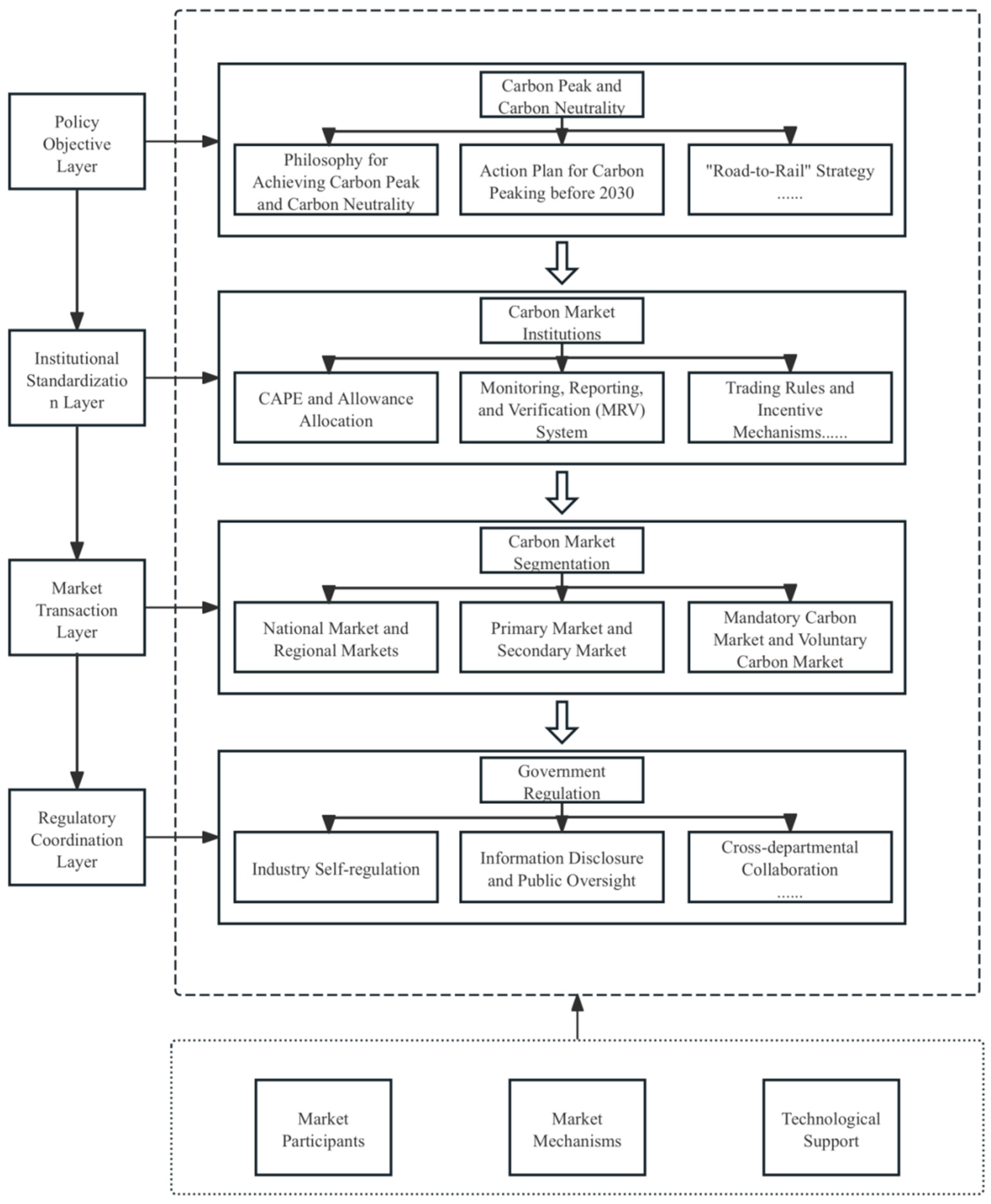

3.3. Layered Analysis of Railway Freight Carbon Market

3.3.1. Policy Objective Layer

The primary goal of designing a railway freight carbon trading mechanism is to support China’s strategic "Dual-Carbon" objectives—achieving carbon peaking before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. As a key market-driven instrument, carbon trading contributes to railway freight decarbonization in two critical ways: defining clear industry-specific emission reduction targets aligned with national objectives, and creating endogenous incentives through carbon pricing to drive green, low-carbon transformations and facilitate the structural shift from road to rail ("Road-to-Rail"). To ensure these goals are effectively implemented, policy objectives must be clearly defined and operationalized across three key dimensions:

1. Emission Reduction Targets Aligned with "Dual-Carbon" Goals

Under the overall "Dual-Carbon" framework, the railway sector, characterized as low-carbon transportation, has the binding responsibility to peak emissions before 2030 and achieve deep decarbonization by 2060. Guided by top-level policy documents such as the "Opinions on Fully, Accurately, and Comprehensively Implementing the New Development Philosophy for Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality" and the "Action Plan for Carbon Peaking before 2030," specific emission reduction indicators for railways must be quantified and systematically decomposed[

28,

29,

30]. Achieving significant reductions in comprehensive energy consumption and carbon emissions in railway operations by 2030 is essential. Given railway freight’s inherent advantages of high transport capacity and relatively low energy intensity compared to higher-emission sectors (e.g., road transport), precise policy timelines aligning with electrification and renewable energy adoption will maximize rail’s contribution as an early mover in transportation decarbonization. Carbon trading policies for the railway sector should thus enforce rigorous yet adaptable allowance allocations, dynamically adjusting to industry developments to ensure timely peak emissions before 2030.

2. Green Low-Carbon Transition by Endogenous Incentives and Price Signals

Carbon trading mechanisms internalize carbon costs into corporate decision-making, making each emitted tonne of CO2 carry explicit economic or opportunity costs. This "carbon pricing" acts as a binding constraint for enterprises. Higher carbon prices encourage firms to increase investments in energy-saving and carbon reduction projects. Conversely, when carbon prices are low or volatile, supporting regulatory guidance and stable policy frameworks are essential for continuously and reliably transmitting price signals. Beyond passive emission constraints, carbon trading actively stimulates innovation. Railway companies will intensify research and development in low-carbon infrastructure, energy-efficient locomotives, renewable energy technologies, intelligent scheduling, and big data logistics management to mitigate emission-related costs. Simultaneously, new business services and management tools, such as carbon asset management platforms and carbon footprint accounting systems, will emerge to meet compliance requirements, accelerating comprehensive industry-wide low-carbon transformations.

3. "Road-to-Rail" based on Structural Adjustments and Synergistic Benefits

The "Road-to-Rail" policy aims for structural optimization within the transportation system, targeting emissions-intensive road freight to shift towards lower-emission rail freight. Through differentiated allowance allocations and complementary measures, carbon trading makes the high-carbon cost of road transport explicitly visible, enhancing railway freight’s comparative economic attractiveness. Increased railway freight market share subsequently reduces aggregate emissions from road transport, generating synergistic decarbonization effects across the entire transport sector. Additionally, carbon trading policies, in conjunction with fuel taxes, road usage regulations, and environmental tax, establish a cohesive policy environment conducive to advancing the "Road-to-Rail" transition.

3.3.2. Institutional Standardization Layer

Robust institutional frameworks are fundamental to the smooth operation of railway freight carbon trading mechanisms, directly impacting emissions reduction effectiveness. Key institutional components include:

1. Emission Cap-Setting and Allowance Allocation

Emissions cap-setting should align with China’s overall railway decarbonization roadmap, targeting a 10% reduction in unit energy consumption and CO2 emissions per transport workload compared to 2020 [

28]. Government regulators can scientifically forecast and dynamically adjust total emission caps based on anticipated railway transport volumes, technological advancements, and energy transitions. Regular evaluations ensure emissions constraints balance reduction pressures with industry realities, providing clear benchmarks for market-based allocations and performance verification.

Allowance distribution combines fairness (historical-based allocation), efficiency (auction and benchmark methods), and incentives (Certified Emission Reductions, CER). Initially, free allocation based on historical emissions, transport volumes, and energy types helps smooth industry transition. Gradually incorporating auctions enhances carbon pricing effectiveness, providing financial aid for further low-carbon technological and infrastructure investments.

2. Trading Mechanisms

Transparent, unified carbon trading platforms should define clear transaction procedures, information disclosure requirements, and pricing mechanisms to foster fair market interactions. Diverse market participants—including railway firms, financial institutions, investors, and CER project developers—enhance liquidity and market activity. Comprehensive risk management (price ceilings/floors, margin requirements, penalties for violations) is crucial to maintain market stability and prevent speculative excesses.

Reward and penalty systems should incentivize proactive emission reductions, rewarding firms that exceed targets through future allowance allocations or tax benefits, while strictly penalizing non-compliance or fraudulent reporting through allowance reductions, substantial fines, or suspension of trading privileges.

3. Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV)

Precise, transparent MRV systems leveraging digital technologies (GIS, IoT sensors, blockchain, and big data analytics) ensure accurate emission measurements and credible data reporting. Independent third-party audits and standardized reporting methodologies mitigate inconsistencies, while initial financial support or additional allowances for compliant high-quality data collection encourage proactive enterprise participation.

3.3.3. Carbon Market Transaction Layer

The carbon market, a critical platform for carbon pricing and allowance transfers, significantly advances railway freight’s low-carbon transformation. Effective carbon market design entails clear segmentation and interconnection based on geographic scope, mandatory levels, and participant types:

1. Regional Segmentation

From a regional standpoint, carbon trading markets can be differentiated into local carbon markets and a national carbon emissions trading market. Local markets, initiated by regional governments, emerged from China’s pilot carbon trading programs. Currently, seven provincial or municipal pilot markets operate in Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Hubei, Guangdong, Shenzhen, and Chongqing. These pilot programs focus predominantly on high-emitting sectors such as power and steel industries, adopting an initial free allowance allocation model that is gradually transitioning toward auctions. They are characterized by relatively flexible policy implementation and lower regulatory costs. Given their limited coverage, can have restricted market liquidity and price discovery. However, variations in allowance allocation methods, verification protocols, and data reporting standards across these pilots present both challenges and valuable lessons for establishing a unified national market.

Building on these localized experiences, China’s national carbon emissions trading market—launched on a trial basis in 2017—initially covered the power sector and will progressively expand to other high-emitting industries. The national market benefits from greater scale, broader participation, enhanced information transparency, and higher liquidity, thus better fulfilling price discovery and inter-regional resource allocation. By imposing strict total emission caps and dynamic adjustment mechanisms, it ensures a gradual decline in overall carbon emissions and creates a more equitable competitive environment for enterprises. Additionally, it can draw upon international experiences such as the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) to refine allowance allocation, monitoring–reporting–verification (MRV), and other operational aspects, thereby bolstering regulatory effectiveness and risk management capacity.

2. Regulatory mandate classification

Based on how carbon allowances are enforced, carbon trading markets fall into two categories: compliance (mandatory) carbon markets (cap-and-trade) and voluntary carbon markets (Certified emissions reduction trading).

In compliance markets, the core mechanism is “cap + trade,” whereby the government sets an emissions cap for regulated entities based on their historical emissions and required reductions. Enterprises must operate within this allocation or purchase extra allowances (or Certified emissions reductions, CER) if they exceed the cap. Once rail freight operators are brought into these compliance markets, carbon management and cost accounting become integral to their business operations. They will prioritize energy-saving technological retrofits and renewable energy adoption to mitigate steadily rising carbon costs. This process can also exert a “crowding-out” effect on more carbon-intensive modes such as road transport, helping advance the policy goal of shifting freight from road to rail.

By contrast, voluntary carbon markets center on the trading of CERs generated by various emissions-reduction projects. Although purchasing CERs is optional, in China’s framework, compliance entities may use a certain percentage (e.g., up to 5%) of CERs to meet their compliance obligations, providing greater flexibility and lowering costs. Rail sector stakeholders can develop projects like forestry carbon sinks, renewable energy utilization, and locomotive efficiency improvements to generate CERs and sell them on the voluntary market, thereby securing additional revenue streams. This approach not only improves the overall decarbonization efficiency of the rail system but also helps raise capital for energy-saving initiatives.

3. Market function classification

In terms of market functions, carbon markets can be grouped into primary and secondary markets.

The primary market handles allowance allocation and the issuance of emissions reduction credits, ensuring a stable supply of carbon assets. Primary-market participants include government, regulated entities, and other parties that voluntarily engage in carbon reduction activities. The government allocates allowances in the primary market to manage total emissions and sets the cap in line with the nation’s reduction targets. This initial allocation must be fair, transparent, and aligned with sector-specific realities.

The secondary market is designed to enhance the flexibility and liquidity of carbon trading. In this open market, regulated entities (including transport operators), individuals, or financial institutions can freely trade allowances or CER. Price formation in the secondary market responds to supply-and-demand dynamics and guides resources toward their most efficient uses. Additionally, financial institutions can introduce derivatives (e.g., carbon futures, options) to help participants hedge price volatility risks and mitigate uncertainties around carbon costs. These instruments also broaden market participation and enhance market depth.

The effective coupling of the primary and secondary markets facilitates the continual reallocation of emission allowances among diverse stakeholders, optimizing resource efficiency and injecting liquidity into the market—both of which drive the sector’s green transition.

3.3.4. Regulatory and Coordination Layer

A robust system of oversight and multi-party coordination is essential to ensure fairness, order, and efficiency in carbon market operations. Given the cross-regional, multi-actor, and multi-step nature of rail freight, developing a sound regulatory and coordination mechanism is especially critical.

1. Building and Refining the Regulatory System

Clarifying the responsibilities of carbon market regulators is a vital first step. Given the distinct parts of carbon trading, it is necessary to designate primary oversight body and collaborative bodies accordingly. Key authorities—such as the National Development and Reform Commission, transport ministries, environmental protection regulators, and financial regulators—must fulfill roles including data verification, market supervision, and penalty enforcement. Regulators should inspect the emissions data submitted by rail enterprises to prevent misreporting or falsification and continuously monitor allowance trading and derivatives transactions to detect market manipulation, insider trading, or excessive speculation.In addition, entities that fail to comply, deliberately fabricate data, or undermine market order face administrative sanctions or financial penalties, ensuring robust deterrence and impartiality.

2.Industry Self-Regulation and Internal Incentives

Industry associations can reinforce self-regulation by drafting emissions standards, technical guidelines, and ethical norms that encourage enterprises to adhere voluntarily to carbon trading rules. For instance, associations may provide specialized training and technical guidance, organizing seminars and workshops on emissions accounting, MRV protocols, trading strategies, and avenues for low-carbon innovation. Or they implement self-imposed codes of conduct and peer reviews, motivating rail operators to benchmark decarbonization efforts and share best practices.Or within rail freight enterprises, a “carbon performance evaluation” system can be adopted, tying departmental or project-level emissions outcomes to bonuses and career advancement. This top-down mechanism stimulates greater initiative in emission reduction efforts across the organization.

3. Information Transparency and Public Oversight

Governmental regulators and industry associations should publish regular updates on market transactions, emission reduction outcomes, and other relevant data, thereby enabling external stakeholders and the general public to monitor carbon trading activities. On the one hand, transparent disclosure fosters investor and public confidence, supporting the stable growth of the market. On the other, it deters misconduct, ensuring information timeliness, symmetry, and accuracy.

To strengthen societal oversight, authorities can establish reporting channels for environmental groups, research institutions, and the public to flag suspicious emissions data or trading practices. Third-party evaluators—such as independent think tanks or environmental NGOs—are also encouraged to perform periodic assessments of carbon market policies and disseminate their findings via media channels, thereby introducing external scrutiny and public pressure on both enterprises and regulators.

4. Cross-agency and Cross-Regional Collaboration

Because carbon trading spans multiple domains (transport, energy, environment, finance, and taxation), the absence of inter-agency coordination can lead to overlapping or fragmented oversight. Governments should adopt uniform interdepartmental collaboration mechanisms, convene joint meetings regularly to share data and market updates, and develop unified policy measures.

Rail transport often extends across provinces or even national borders, and individual local markets might struggle to cover the entire transport chain. Therefore, it is crucial for provinces or transnational regions to align regulatory rules, share data, and mutually recognize allowances to prevent emissions “leakage” or “concealment” across jurisdictions. Through broad-based collaboration, policy overlap or conflict can be minimized, and financial, technological, and informational resources can be pooled more effectively—thereby ensuring that rail freight decarbonization seamlessly aligns with national carbon trading mechanisms.

3.4. Research on Carbon Market’s Three Dimensions

3.4.1. Market Participants

The effective functioning of the carbon trading market relies on close interactions and coordinated division of responsibilities among multiple stakeholders, making market participants central to the carbon trading mechanism. Within the railway freight sector, roles and behaviors of these participants directly influence emission reduction outcomes, economic performance, and the overall liquidity and stability of the carbon market. Based on the operational characteristics of railway freight and the logic of carbon trading, market participants can be classified into five main categories: government (including regulatory bodies), controlled enterprises and emission reduction project developers, financial institutions and qualified traders, carbon exchanges, industry associations, and third-party verification institutions along with the public.

1. Government and Regulatory Authorities

The government acts as the architect and regulator of the carbon trading market, responsible for policy formulation, market supervision, regulatory enforcement, and resource allocation. It establishes overarching emissions reduction targets, sets allocation principles and quotas, and ensures market fairness and transparency by clearly defining regulatory mandates, including data auditing, compliance enforcement, and information disclosure. Financial incentives such as subsidies, tax reliefs, and infrastructure investments are provided, especially during the initial phases, to assist railway enterprises in adapting to carbon constraints and reducing transition costs, thereby promoting active market participation and expediting structural transformation.

2. Controlled Enterprises and Emission Reduction Developers

These entities manage and account for their carbon emissions or emission reductions, actively engaging in trading activities to meet regulatory compliance and profitability objectives. Railway enterprises manage their emissions through precise carbon asset management, trading allowances, technological improvements, and voluntary emission reduction projects (CER). The explicit carbon costs influence operational and investment decisions, such as green locomotive procurement, energy utilization, transport management, and technology adoption, incentivizing proactive engagement with energy-efficient and low-carbon practices.

3. Financial Institutions and Qualified Traders

Financial institutions and qualified traders provide essential liquidity, contribute significantly to price discovery, and promote the development of financial derivatives and green finance. Banks, investment firms, insurance companies, and professional investors inject funds and liquidity into the carbon market by trading allowances and CERs, stabilizing prices and facilitating efficient resource allocation. Derivatives such as carbon futures and options allow railway enterprises to hedge carbon costs and manage price volatility. Increased financial involvement diversifies market instruments, including forwards, swaps, and index investments, enhancing market depth, efficiency, and stability. Specialized green financial products tailored for railway enterprises further support their low-carbon transitions through energy efficiency and renewable energy investments.

4. Carbon Exchanges

As a critical market infrastructure and the core trading platform within the carbon emissions trading system, carbon exchanges play an essential role in enabling railway freight enterprises and other market participants to realize the financial value of their carbon assets through allowance trading. The operational efficiency and institutional design of these exchanges significantly influence market liquidity, transparency, and stability. First, from the perspective of market operations, carbon exchanges establish and enforce trading rules, organize allowance trading, and facilitate market matching. By providing transparent trading platforms and robust clearing mechanisms, they safeguard participants' interests, reduce transaction costs, and enhance trading efficiency, thereby effectively facilitating price discovery. Second, regarding information dissemination, carbon exchanges are responsible for publishing crucial market data such as carbon price indices, trading volumes, transaction trends, and analytical reports. This significantly mitigates information asymmetry among railway freight enterprises, investors, and regulatory bodies, enabling market participants to timely grasp market dynamics and make rational investment decisions. Third, carbon exchanges bear significant responsibilities in risk management, including market risk monitoring, early warning systems, risk prevention, and emergency response mechanisms. By establishing rigorous transaction monitoring frameworks, margin systems, and anomaly transaction handling protocols, exchanges effectively anticipate and mitigate systemic risks and sharp market price fluctuations. Finally, carbon exchanges also proactively contribute to policy coordination and market innovation. Through close collaboration with regulatory authorities, industry associations, and financial institutions, exchanges co-develop tailored trading rules and innovative products specifically suited to railway freight sector characteristics, including specialized carbon financial instruments and derivatives. Additionally, by providing targeted training programs and consultancy services, exchanges help railway freight enterprises better adapt to market rules and achieve their low-carbon transformation objectives. In summary, carbon exchanges play an indispensable role in promoting railway freight enterprises' participation in carbon markets, stimulating sector-wide emissions reduction efforts, and driving structural decarbonization in railway transportation.

5. Industry Associations

Industry associations complement government oversight by promoting self-regulation and industry-wide collaboration. They formulate standardized accounting methodologies, data management protocols, and ethical guidelines that encourage members to comply with carbon market rules. These associations can hold seminars, workshops, and technology showcases to equip railway freight enterprises with up-to-date policy interpretations, best practices, and case studies, thereby elevating overall decarbonization performance across the sector.

6. Third-Party Verification Agencies, and the Public

Third-party verification agencies and the general public play vital supervisory roles in ensuring data integrity and upholding the credibility of carbon trading. Independent, professional auditors validate emissions data submitted by enterprises and verify the outcomes of emissions-reduction projects, thus mitigating risks of false reporting or misconduct. Their unbiased verification also provides a trusted reference point for market participants and regulatory authorities alike. The general public—including media, social organizations, and individual consumers—can likewise hold enterprises and government agencies accountable by scrutinizing publicly disclosed information. Broader societal acceptance of low-carbon transport reinforces the market positioning of rail freight solutions; positive public opinion and demand for sustainable mobility options can further motivate railway operators to enhance environmental performance and accelerate the transition to green logistics.

3.4.2. Carbon Trading Mechanisms

Mechanisms that guide how allowances or carbon credits move among market participants—and how carbon-related costs are internalized—are central to effective carbon trading. In the context of China’s railway freight sector, this study delineates a two-tier model: the primary market (where government agencies set emissions caps and distribute initial allowances) and the secondary market (where rail freight operators make operational decisions under carbon constraints and engage in allowance/credits trading to maximize profits).

1. Primary Market

The primary market is administered by government agencies, which establish sector-wide emissions caps and allocate initial allowances among regulated entities in line with the compliance period’s reduction objectives. Two core steps are involved:

(1) Setting the Total Emissions Cap

The first step uses scientifically grounded targets that take into account overall national or regional development considerations, as well as reduction potential across industries[

31]. This study restricts the emissions boundary primarily to mobile sources—i.e., in-service locomotives—omitting life-cycle emissions from infrastructure construction or maintenance based on international practice and the current level of carbon emission monitoring technology. In practice, total emissions can be estimated using either a top-down or bottom-up approach, as recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2006)[

32]. Top-down is to leverage aggregated energy consumption statistics and emission factors from authoritative bodies like the National Bureau of Statistics, National Energy Administration, or National Railway Administration. This macro-level approach can minimize gaps in accounting, ensuring alignment with official energy statistics. Bottom-up means summing detailed activity data—for example, per-vehicle mileage, cargo loads, and fuel usage—multiplied by specific emission factors. Though more accurate , this method requires extensive data. In practice, IPCC guidelines recommend cross-verification of these two approaches to enhance reliability.

Given China’s centralized data collection and stable operating conditions for rail freight, a top-down method based on aggregated railway energy consumption often serves as the baseline, supplemented by bottom-up checks on high-priority corridors or locomotive types[

14] .

Model Assumptions and Constraints:

The rail freight sector adheres to a designated peak emissions timeline (e.g., before 2030), with government gradually tightening sector allowances to align with these targets.

Emissions calculations only include direct diesel combustion from diesel locomotives and indirect emissions from purchased electricity for electric locomotives—thus excluding life-cycle emissions from infrastructure.

The cap can be recalibrated annually, declining steadily or holding post-peak at a stable level.

International or cross-border railway emissions remain out of scope; calculations focus on domestic railway operations.

Within the compliance period, the baseline carbon emissions for the railway freight sector can be determined via the following model:

where E denotes the baseline carbon emissions (in tonnes of CO2) for the railway freight sector during the compliance period; i indexes fuel type; F is the consumption of fuel type i (in TJ);

is the carbon emission factor (tonnes/TJ) for fuel i;

represents electricity consumption (in kWh) for the freight railway system;

is the carbon emission factor for electricity (tonnes/kWh);

is the thermal conversion rate for fuel i, generally expressed in TJ/tonne (for solid or liquid fuels) or TJ/m

3 (for gaseous fuels); and

is the energy conversion coefficient for each fuel type i (in TJ/tonne or TJ/m

3 ).

The total initial carbon emissions for the compliance period are then calculated using the following model:

In this expression, Q represents total carbon emissions (in tonnes of CO2 ) from railway freight during the compliance period, while R indicates the reduction rate for carbon allowances over that same period.

(2) Allocation of Emissions Allowances

After establishing the total emissions cap for the railway freight sector, the government must allocate these allowances reasonably among the regulated entities—such as regional railway bureaus, joint-venture rail companies, or other rail freight operators. By issuing initial allowances, regulatory bodies enforce emissions-reduction responsibilities and implement differentiated management strategies. Allowance allocation mechanisms should balance both fairness and efficiency. Globally, the most common approaches can be classified into two broad categories—paid (auction) and free allocation [

33] . Free allocation can further be subdivided into historical emissions methods (the “grandfathering” approach), sectoral benchmarking methods, or historical intensity reduction methods[

34] .

Although theoretical analyses suggest that under zero transaction costs and perfect competition, initial allowance distribution does not affect market efficiency in carbon trading [

35] , real-world conditions entail trading frictions and imperfect competition, preventing academic consensus on a single “best” allocation method. Many international carbon markets, at various development stages or across specific regions and industries, adopt different allocation approaches. However, most countries begin with free allocation in the early stages of carbon markets, primarily to ease the financial burden on key industries and encourage early participation [

36]. As markets mature and enterprises develop mitigation strategies, auction-based methods are gradually introduced to enhance price accuracy and generate reinvestment funding.

China’s current allowance system features both free and paid allocations. In the existing regional pilot programs, free allocation is the primary mechanism across all pilots—for instance, Beijing and Fujian employ fully free allocation—while certain provinces implement a hybrid of free and paid methods. For example, Guangdong Province adopted partial free, partial paid allocation of allowances in 2021: steel, petrochemical, cement, and paper enterprises received 96% free allowances, whereas aviation enterprises received 100% of their allowances free, with the remainder purchasable as needed. At the national level, China’s nationwide carbon emissions trading market has so far relied on free allocation, though future plans may combine free and paid approaches.

Given the multiple stakeholders and diverse interests in China’s rail freight sector, this study recommends free historical-based allocation during the initial phase of railway freight carbon trading. Such an approach eases the transition for enterprises and aligns with precedents from the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) in its early phase (Phase I) and the U.S. SO2 /NOx trading programs [

37,

38] . These programs began with grandfathered (historical) free allocations to expedite market launch, garner industry cooperation, and accumulate data, while mitigating short-term shocks. Over time, as the railway freight carbon market matures, China could gradually introduce paid (auction) allocations and increase the auction ratio, thereby allowing carbon prices to more accurately reflect reduction costs.

The allowances for the railway sector based on historical emissions averages is:

where

represents the sector’s annual average historical emissions. Suppose the railway freight sector has n compliance entities, and each entity’s historical average emissions are denoted by

(often the average of three to five recent years; this study adopts three years in line with prevailing market practice).

In line with the predetermined upper limit Q for the railway freight sector’s carbon emissions, the allowance for each entity is allocated proportionally:

where

is the free allowance allocated to entity j.

2. Secondary Market

The secondary market is the venue in which enterprises or other participants freely trade carbon emission rights (allowances, CERs, etc.). Through an overall cap-and-trade system, the government or competent authority allocates a certain volume of carbon allowances to railway enterprise j. During the compliance period, enterprise j may purchase or sell carbon credits (encompassing both allowances and CER) to meet its compliance obligations or obtain additional revenue; the carbon price is primarily determined by market supply and demand, in circumstances where the market fails to function efficiently or when required to stabilize the system, government authorities may implement price control measures.

Within the carbon market, the following relationship applies to enterprise j between its actual carbon emissions and the enterprise’s initially allocated allowances , carbon offset credits .

If

the enterprise must buy additional allowances

from the market:

If

then the enterprise needs no extra allowances and can, in fact, sell the surplus credits:

The revenues (or costs) from an enterprise’s sale (or purchase) of allowances in the secondary market, denoted as:

A positive Z indicates the enterprise has earned revenue by selling surplus carbon assets; a negative Z indicates that it has incurred costs by purchasing extra allowances.

3.4.3. Technical Support

Within the framework of a railway freight carbon trading market, technical support serves as the lynchpin for ensuring efficient, transparent, and robust market operations. Based on this study’s analyses and a broad review of relevant literature, two core technological components are indispensable: carbon emissions monitoring and accounting (MRV) technology, the construction and operation of digital carbon trading platforms.

1. Carbon Emissions Monitoring and Accounting (MRV) Technology

A substantial body of research identifies precise measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) as a prerequisite for a healthy carbon trading system [

39,

40]. For the railway freight sector, accurately capturing and calculating in-transit energy consumption and emissions is fundamental not only to setting allowances and evaluating mitigation performance but also to finalizing trading settlements. Recommended railway freight emissions monitoring methods include energy-consumption-based estimates, route tracking techniques, and direct emissions measurement. In practice, these approaches are often augmented with IoT sensors, real-time energy monitoring devices, trackside energy collectors, satellite positioning(Beidou or GPS), and comprehensive, intelligent data analysis of train operating parameters [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. In addition, Ju et al. (2022) propose a distributed traceability model based on “traceability off the chain and verification on the chain” which uses a distributed storage file structure to achieve rapid retrieval and localization of carbon data in hybrid on-chain records[

46]. This significantly improves traceability efficiency for long-span trading chains and meets multi-tier user demands for auditability.

Ding et al. (2024) highlight that strengthening intelligent energy monitoring and management is critical to reducing carbon emissions in railway operations[

47]. By equipping locomotives with real-time monitoring devices, IoT sensors, and energy management systems, enterprises can continuously collect data on traction energy consumption, the switching of power types, locomotive motor status, and other key indicators. Similarly, Li and Zhu (2025) demonstrate in their “net-train-line” coupling study for high-speed trains that capturing and modeling high-frequency data such as speed, gradient, and traction parameters substantially improves the precision of spatiotemporal emissions estimates—an approach equally relevant to freight locomotives[

48]. As these new technologies enhance both data collection and analytic efficiency, they lay a more objective foundation for allowance allocation and carbon price formation. Consequently, MRV technology not only drives carbon market operations but also underpins the railway freight sector’s low-carbon transition by supplying critical baseline data.

2. Construction and Operation of a Carbon Trading Platform

Several studies emphasize that building a digital, intelligent carbon trading platform is vital to achieving efficient resource allocation, reducing transaction costs, and mitigating information asymmetry (Chen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020)[

9,

49]. In the context of railway freight carbon trading—where transport processes are intricate and participants are numerous—unifying diverse operational links and data interfaces on a shared, collaborative trading system poses significant technological challenges.

In recent years, blockchain technology, with its consensus mechanisms, encryption methods, distributed data storage, and real-time processing capabilities, has proven essential for ensuring data transparency and tamper-proof records in carbon trading [

50,

52]. Through Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), each transaction of allowances or instructions in a railway freight carbon market is recorded on-chain and validated by multiple network nodes. Once data are verified and written to the ledger, no single participant can alter them unilaterally—a safeguard against duplicated trades, data manipulation, and other misconduct, while enhancing the openness and traceability of regulatory oversight. In addition, smart contracts automate the execution of trading instructions, fund transfers, and settlements once pre-agreed conditions are triggered. This functionality lowers the barriers to market participation, boosting trading efficiency [

53].

Technical support comprises not only data collection, encryption, and intelligent transaction processing but also big-data-based real-time monitoring of carbon price fluctuations, trading volume shifts, and potentially suspicious orders. In cases of an abrupt spike in the carbon price or large-scale buy orders, the platform can automatically alert regulators or exchange authorities. Coupled with protective mechanisms like price limits and temporary margin rules, these alerts mitigate the risk of speculative excess and market manipulation.

In conclusion, advanced technological support across multiple dimensions ensures a reliable and efficient railway freight carbon trading market. Real-time emission monitoring, transparent trading platforms, and comprehensive tracing systems collectively create a robust environment for sustainable, low-carbon industry transitions, reinforcing competitive market positioning and long-term adaptability.