Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Strains

2.2. Animals

2.3. Obtaining and Characterization of MVs

2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.5. SDS-PAGE

2.6. Obtaining of L3 Larva Stage from H. contortus

2.7. Culture of Abomasal Explants

2.8. Recovery of L3 Larvae of H. contortus

2.9. Histopathology

2.10. Larval Mortality Assay

2.11. RAW 264.7 Cell Cultures

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

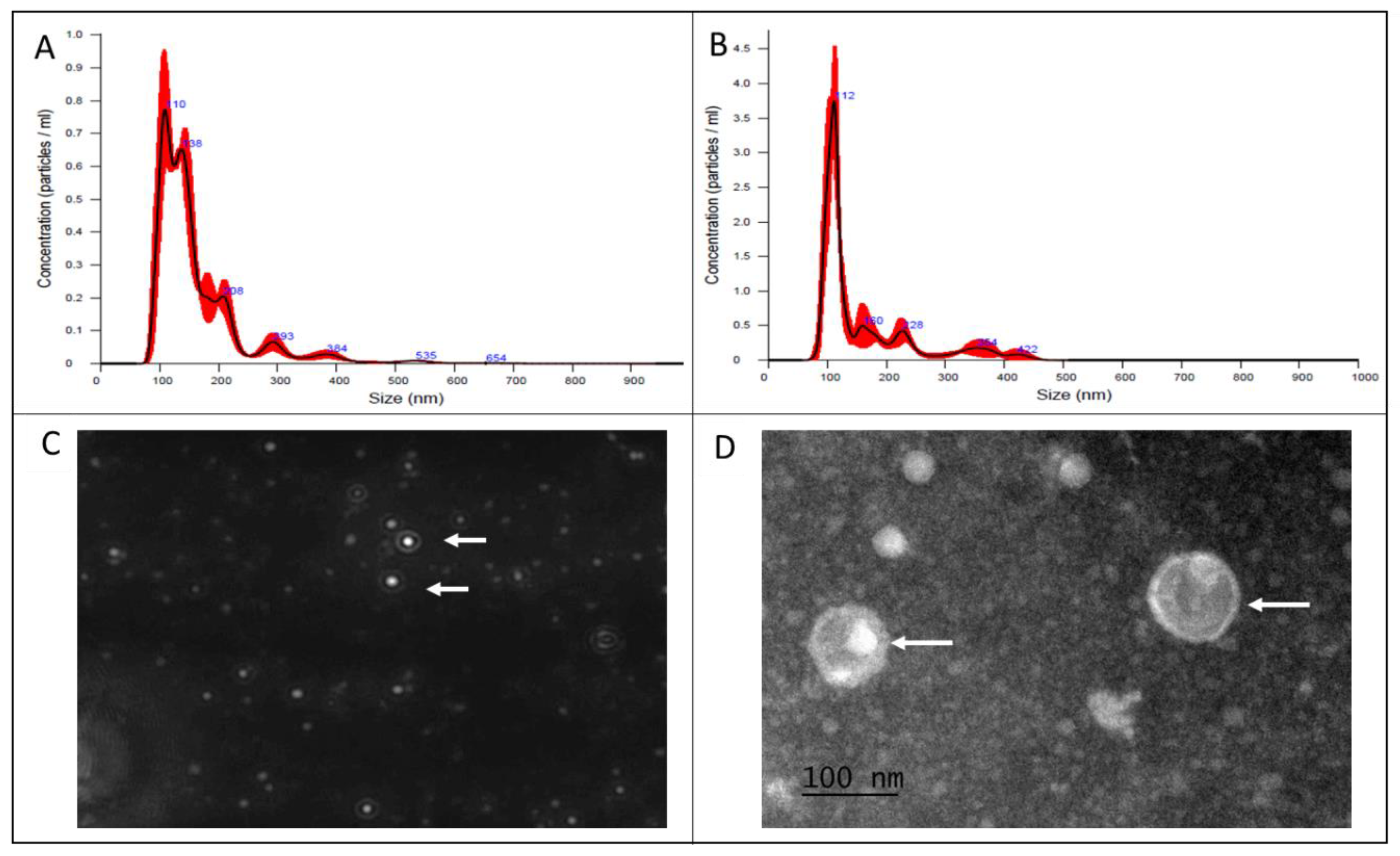

3.1. Characterization of MVs by NTA and TEM

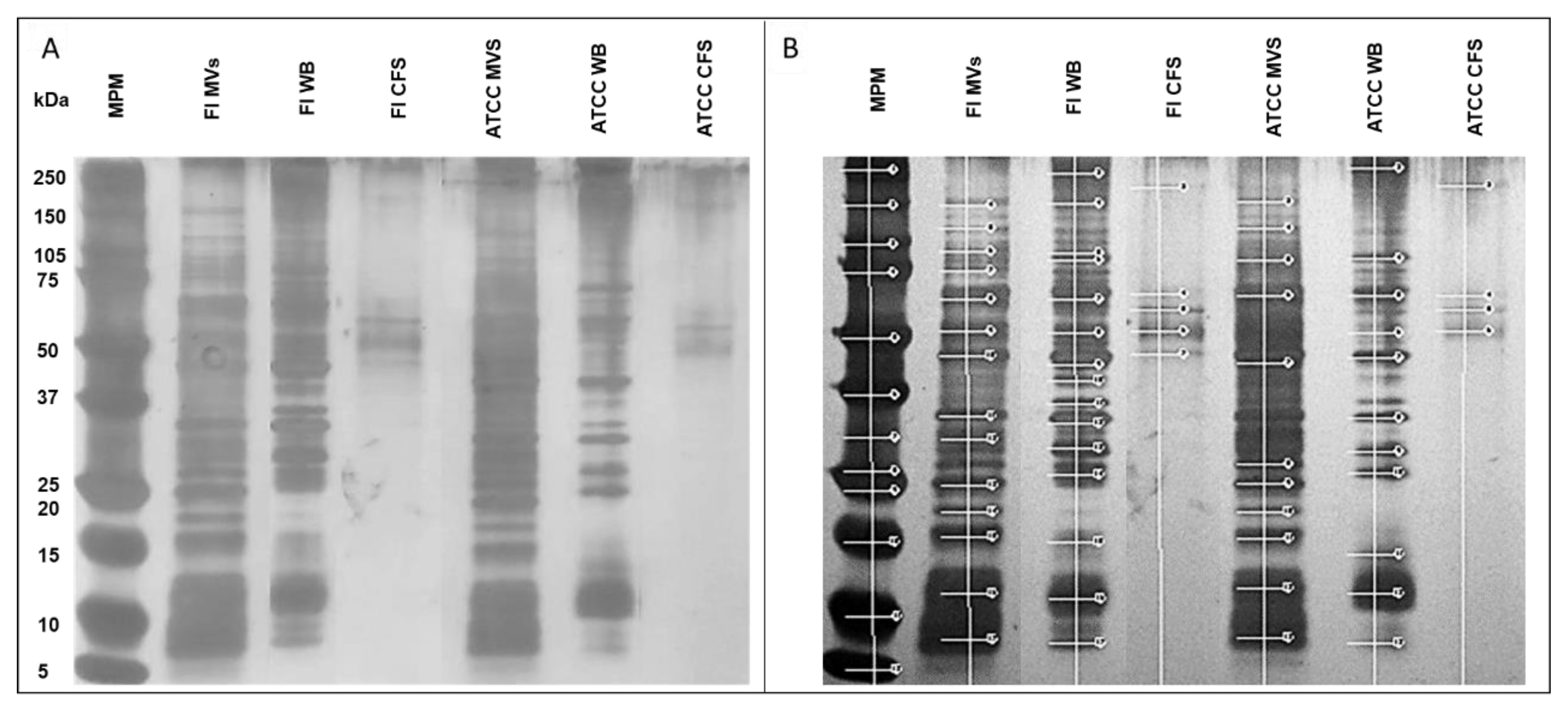

3.2. L. acidophilus MVs Express Proteins

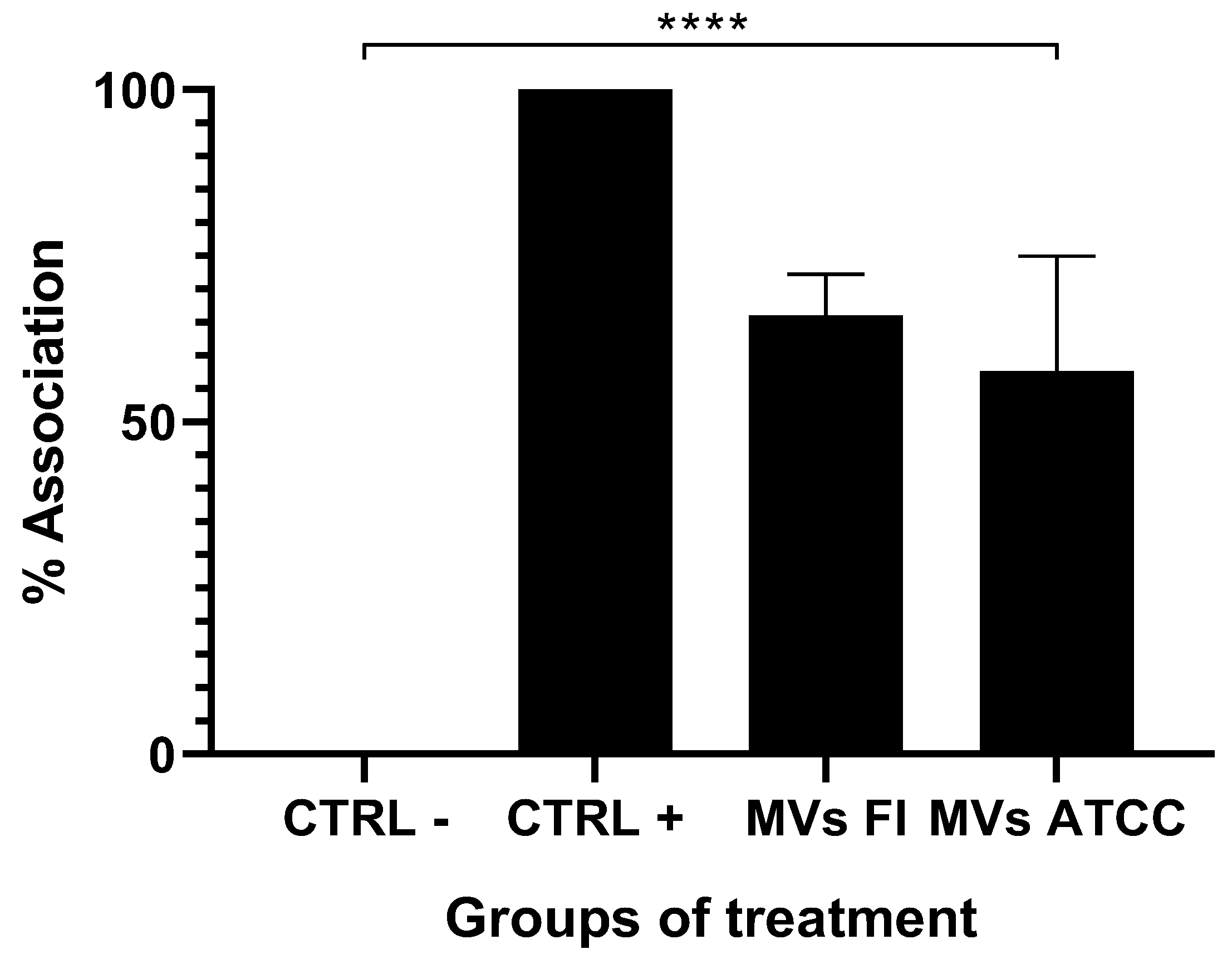

3.3. Tissue Stimulated with L. acidophilus MVs Decrease Larvae Association

3.4. Stimulation with the Field L. acidophilus MVs Increase the Presence of Inflammatory Cells in the Abomasal Tissue

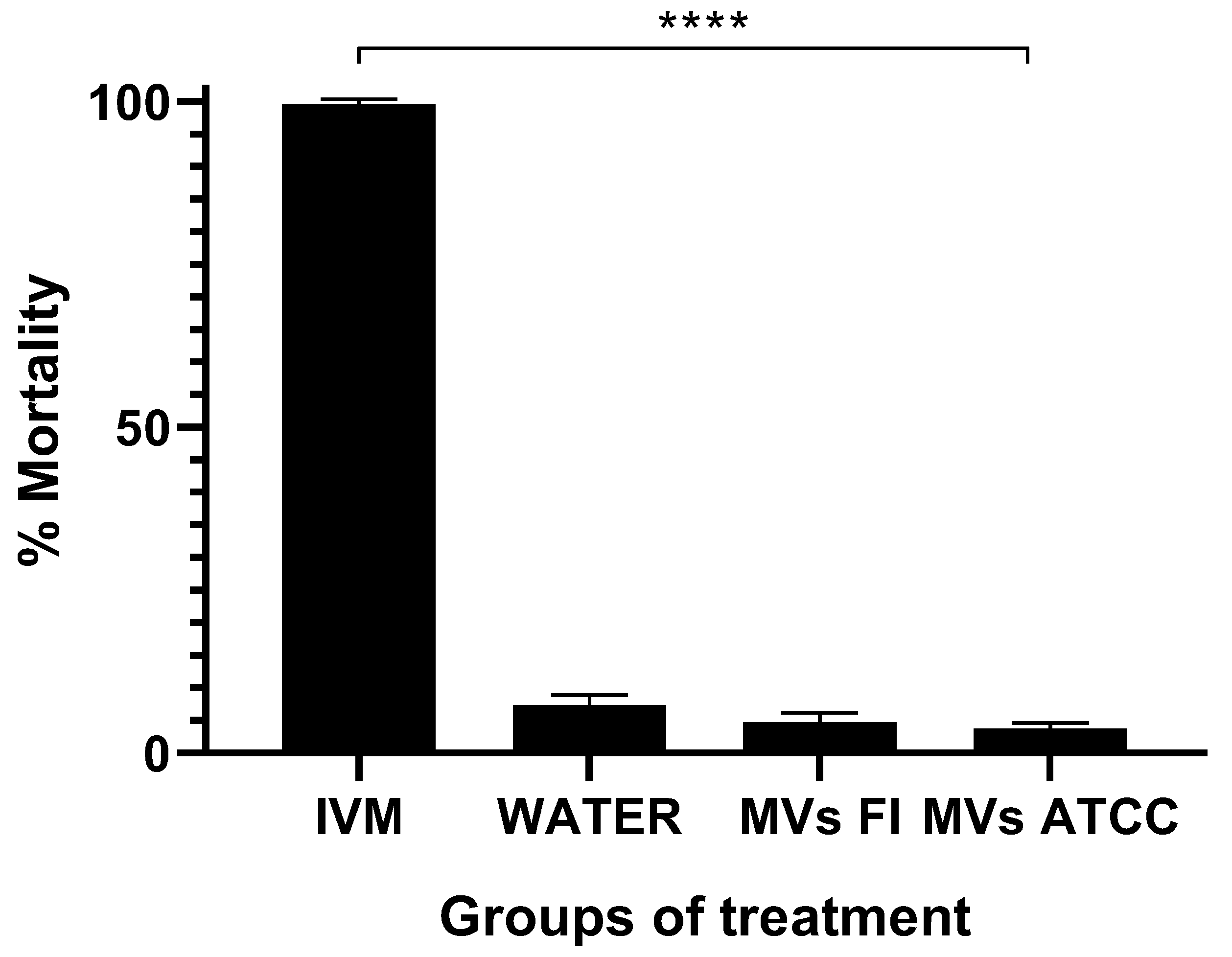

3.5. L. acidophilus MVs Do Not Kill the L3 Larvae of H. contortus

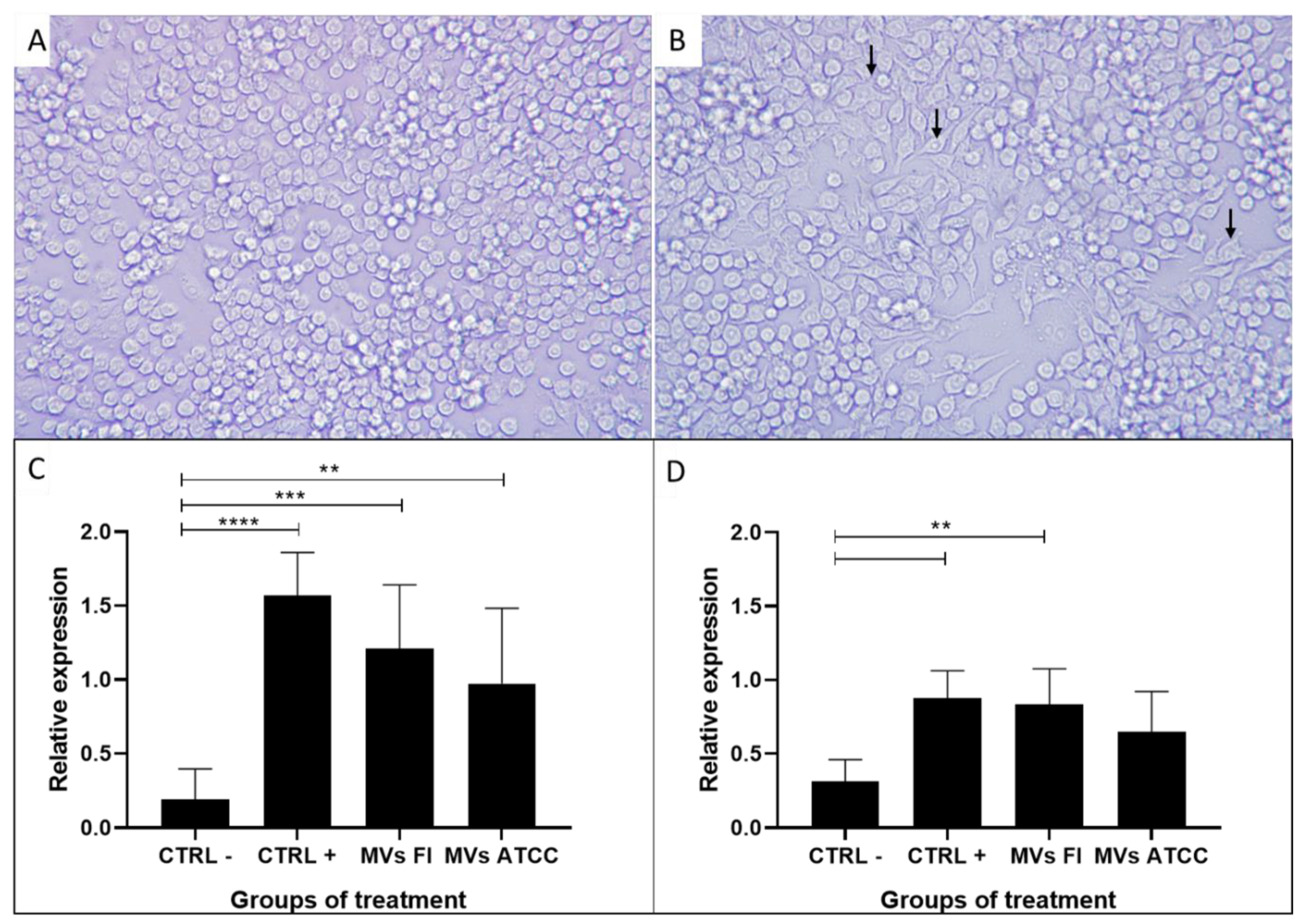

3.6. L. acidophilus MVs Activate Macrophages (RAW 264.7)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MVs | Microvesicles |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal tract |

| L3 | Stage 3 larva |

| WB | Whole bacteria |

| CFS | Cell-free supernatant |

| BLS | Bacteriocin-like substances |

| FI | Field Isolated |

References

- Santacroce, L.; Charitos, I.A.; Bottalico, L. A successful history: probiotics and their potential as antimicrobials. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther 2019, 17, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibnou-Zekri, N.; Blum, S.; Schiffrin, E.J.; von der Weid, T. Divergent patterns of colonization and immune response elicited from two intestinal Lactobacillus strains that display similar properties in vitro. Infect Immun 2013, 71, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnsen, J.; Sassone-Corsi, M.; Raffatellu, M. Probiotics: Properties, Examples, and Specific Applications. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013, 3, a010074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, L.; Capurso, L. FAO/WHO Guidelines on Probiotics: 10 Years Later. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001, 46, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corthesy, B.; Gaskins, H.R.; Mercenier, A. Cross-talk between probiotic bacteria and the host immune system. J Nutr 2007, 137(3 Suppl 2), 781S–90S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.; Hevia, A.; Bernardo, D.; Margolles, A.; Sánchez, B. Extracellular molecular effectors mediating probiotic attributes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2014, 359, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nedawi, K.; Mian, M.F.; Hossain, N.; Karimi, K.; Mao, Y.K.; Forsythe, P.; Min, K.K.; Stanisz, A.M.; Kunze, W.A.; Bienenstock, J. Gut commensal microvesicles reproduce parent bacterial signals to host immune and enteric nervous systems. FASEB J 2015, 29, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulp, A.; Kuehn, M.J. Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Annu Rev Microbiol 2010, 64, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Nomura, N.; Eberl, L. Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Eagen, W.J.; Lee, J.C. Orchestration of human macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activation by Staphylococcus aureus extracellular vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 3174–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Moon, C.M.; Shin, T.S.; Kim, E.K.; McDowell, A.; Jo, M.K.; Joo, Y.H.; Kim, S.E.; Jung, H.K.; Shim, K.N.; Jung, S.A.; Kim, Y.K. Lactobacillus paracasei-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate the intestinal inflammatory response by augmenting the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Exp Mol Med 2020, 52, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, A. L.; Corona, A. I.; Jiménez, A. L. L.; Cortés, N. G.; Vera, R. J. Sensibilidad y Resistencia a Antibióticos de Cepas Probióticas Empleadas en Productos Comerciales. ESJ 2020, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Zhang, X.; Tong, L.; Liu, Q.; Liang, X.; Bu, Y.; Gong, P.; Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Y.; Ai, L.; Yi, H. Effect of Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Lactobacillus plantarum Q7 on Gut Microbiota and Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Front Immunol 2021, 2, 12–777147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, S.N.; Leary, D.H.; Sullivan, C.J.; Oh, E.; Walper, S.A. Isolation and characterization of Lactobacillus-derived membrane vesicles. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.L.; Stanisz, A.M.; Mao, Y.K.; Champagne-Jorgensen, K.; Bienenstock, J.; Kunze, W.A. Microvesicles from Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM-17938) completely reproduce modulation of gut motility by bacteria in mice. PLoS One 2020, 7;15(1), e0225481. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.P.; Martínez, J.H.; Martínez, D.C.; Coluccio, F.; Piuri, M.; Pérez, O.E. Lactobacillus casei BL23 Produces Microvesicles Carrying Proteins That Have Been Associated with Its Probiotic Effect. Front Microbiol 2017, 20, 8–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.T. Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs) of Gram-negative Bacteria: A Perspective Update. Front. Microbiol 2017, 8, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Thompson, C.D.; Weidenmaier, C.; Lee, J.C. Release of Staphylococcus aureus extracellular vesicles and their application as a vaccine platform. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.A; Hussein, E.; Davies, S.P.; Humphreys, P.N.; Collett, A. Commensal-derived OMVs elicit a mild proinflammatory response in intestinal epithelial cells. Microbiology (Reading) 2017, 163(5), 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.S.; Ban, M.; Choi, E.J.; Moon, H.G.; Jeon, J.S.; Kim, D.K.; Park, S.K.; Jeon, S.G.; Roh, T.Y.; Myung, S.J.; Gho, Y.S.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, Y.K. Extracellular vesicles derived from gut microbiota, especially Akkermansia muciniphila, protect the progression of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. PLoS One 2018, 8, e76520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargoorani, M.E.; Modarressi, M.H.; Vaziri, F.; Motevaseli, E.; Siadat, S.D. Stimulatory effects of Lactobacillus casei derived extracellular vesicles on toll-like receptor 9 gene expression and cytokine profile in human intestinal epithelial cells. IJDMD 2020, 19, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.M.; Awanye, A.M.; Marsay, L.; Dold, C.; Pollard, A.J.; Rollier, C.S.; Feavers, I.M.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Derrick, J.P. Application of a Neisseria meningitidis antigen microarray to identify candidate vaccine proteins from a human Phase I clinical trial. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3835–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, D.R.; Lichtenegger, S.; Temel, P.; Zingl, F.G.; Ratzberger, D.; Roier, S.; Schild-Prüfert, K.; Feichter, S.; Reidl, J.; Schild, S. A. A combined vaccine approach against Vibrio cholerae and ETEC based on outer membrane vesicles. Front. Microbiol 2015, 6, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, W.; Petersen, H.; Judy B. M., A. Burkholderia pseudomallei outer membrane vesicle vaccine provides protection against lethal sepsis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol 2014, 21, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, S.; Confer, A.W.; Shrestha, B.; Wilson, A.E.; Montelongo, M. Proteomic analysis and immunogenicity of Mannheimia haemolytica vesicles. Clin. Vaccine Immunol 2013, 20, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Garza, M.; González, C.; Suárez, F.; Tenorio, V.; Trigo, F. Biológico vacunal elaborado a partir de Microvesículas (MVs) de Mannheimia haemolytica serotipo A2 de administración intranasal en ovinos. (Mexico pathent Nomber 341611). IMPI 2016. https://siga.impi.gob.mx/newSIGA/content/common/principal.jsf.

- Dhama, K.; Verma, V.; Sawant, P.; Tiwari, R.; Vaid, R.; Chauhan, R. Applications of probiotics in poultry: enhancing immunity and beneficial effects on production performances and health: a review. Immunol. Immunopathol 2011, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Sun, Y.Z.; Wang, A.; Zhou, Z. Probiotics as means of diseases control in aquaculture, a review of current knowledge and future perspectives. Front. Micrrobiol 2018, 9, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia, D.; Biavati, B. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Animal Health and Food Safety Switzerland. Springer International Publishing 2018, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, S.; Di, H.; Deng, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Gut health benefit and application of postbiotics in animal production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol 2022, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Liang, L.; Zhang, G.; Cui, S. Modulatory Effects of Probiotics During Pathogenic Infections with Emphasis on Immune Regulation. Front. Immunol 2021, 12, 616713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhou, M.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, N.F.; Deng, K.D.; Ma, T.; Diao, Q.Y. Effect of oral administration of probiotics on growth performance, apparent nutrient digestibility and stress-related indicators in Holstein calves. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr 2015, 100, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Huang, W.; Hou, Q.; Kwok, L.Y.; Sun, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhao, F.; Lee, Y.K.; Zhang, H. The effects of probiotics administration on the milk production, milk components and fecal bacteria microbiota of dairy cows. Sci. Bull. 2017, 62, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Q.Q.; Chang, J.; Zuo, R.Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Chen, Q.X.; Wei, X.Y.; Guan, Q.F.; Sun, J.W.; Zheng, Q.H.; Yang, X.; Ren, G.Z. Effect of the transformed lactobacillus with phytase gene on pig production performance, nutrient digestibility, gut microbes, and serum biochemical indexes. AJAS 2010, 23, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Zeng, D.; Wang, H.; Sun, N.; Zhao, Y.; Dan, Y.; Pan, K.; Jing, B.; Ni, X. Probiotic Lactobacillus johnsonii BS15 Promotes Growth Performance, Intestinal Immunity, and Gut Microbiota in Piglets. Probiotics Antimicro 2020, 12, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Pan, X. Compound Lactobacillus sp. administration ameliorates stress and body growth through gut microbiota optimization on weaning piglets. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2020, 104, 6749–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraqi, E.K.G.; Fayed, R.H. Effect of yeast as feed supplement on behavioural and productive performance of broiler chickens. J. Life Sci 2012, 9, 4026–4031. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, C.; Manuali, E.; Abbate, Y.; Papa, P.; Vieceli, L.; Tentellini, M.; Trabalza, M.; Moscati, L. Dietary Lactobacillus acidophilus positively influences growth performance, gut morphology, and gut microbiology in rurally reared chickens. Poult. Sci 2018, 97, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anee, I.J.; Alam, S.; Begum, R.A.; Shahjahan, R.; Khandaker, A. The role of probiotics on animal health and nutrition. JOBAZ 2021, 82, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H.; Grimmer, S.; Naterstad, K.; Axelsson, L. In vitro testing of commercial and potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol 2012, 153, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonngi, C. Evaluación del efecto de microvesículas (MVs) de bacterias ácido lácticas (BAL), en cultivos de Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 154 y Escherichia coli de campo. Bachelor’s degree, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, State of Mexico 2022. Avaiable on the institutional repository of the UNAM https://tesiunam.dgb.unam.mx/F/UE2HK7UPD3Q2NV8BG4VCT8GNALMUPXXVYPVIFF5225NLCRDT3A-40114?

- Zhang, S.D.; Lin, G.H.; Han, J.R.; Lin, Y.W.; Wang, F.Q.; Lu, D.C.; Xie, J.X.; Zhao, J.X. Digestive Tract Morphology and Gut Microbiota Jointly Determine an Efficient Digestive Strategy in Subterranean Rodents: Plateau Zokor. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.Q.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Ge, J.; Chen, Y.X.; Chen, X.J.; Zhong, X.S.; Ou, Z.J.; Gao, Y.H.; Cheng, M.J.; Mo, Y.; Wen, Y.Q.; Qiu, M.; Huo, S.T.; Chen, S.W.; Zheng, X.Y.; He, H.; Li, Y.Z.; You, F.F.; Zhang, M.Y.; Chen, Q. Composition of gut and oropharynx bacterial communities in Rattus norvegicus and Suncus murinus in China. BMC Vet. Res 2020, 16, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desvars, A.; Ruppitsch, W.; Lepuschitz, S.; Szostak, M.P.; Spergser, J.; Feßler, A.T.; Schwarz, S.; Monecke, S.; Ehricht, R.; Walzer, C.; Loncaric, I. Urban brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) as possible source of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. Vienna, Austria, 2016 and 2017. Euro Surveill 2019, 24, 1900149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Katsarou, E.I.; Papadopoulos, E. Haemonchosis: A challenging parasitic infection of sheep and goats. Animals 2021, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besier, R.B.; Kahn, L.P.; Sargison, N.D.; Van, J.A. The pathophysiology, ecology and epidemiology of Haemonchus contortus infection in small ruminants. Adv. Parasitol 2016, 93, 95–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, D.L.; Hunt, P.W.; Leo, F.L.J. Haemonchus contortus: The then and now, and where to from here? Int. J. Parasitol 2016, 46, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adduci, I.; Sajovitz, F.; Hinney, B.; Lichtmannsperger, K.; Joachim, A.; Wittek, T.; Yan, S. Haemonchosis in Sheep and Goats, Control Strategies and Development of Vaccines against Haemonchus contortus. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reséndiz, G.; Higuera, R.I.; Lara, A.; González, R.; Cortes, J.A.; González, M.; Mendoza, P.; Romero, S.G.; Olmedo, A. In Vitro Anthelmintic Activity of a Hydroalcoholic Extract from Guazuma ulmifolia Leaves against Haemonchus contortus. Pathog 2022, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México/ SENASICA. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/senasica/documentos/nom-051-zoo-1995 (accessed on 26/03/2025).

- Corticelli, B.; Lai, M. Ricerche sulla tecnica di coltura delle larve infestive degli strongili gastro-intestinali del bovino. Acta Med. Vet 1963, 9, 347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, J.R.; Mega, C.; Coelho, C.; Cruz, R.; Vala, H.; Estebez, S.; Santos, C.; Vasconcelos, C. EBC series on diagnostic parasitology part 3: The Baermann technique. Vet. Nurs. J 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, F.; Greer, A.W.; Huntley, J.; McAnulty, R.W.; Bartley, D.J.; Stanley, A.; Stenhouse, L.; Stankiewicz, M.; Sykes, A.R. Studies using Teladorsagia circumcincta in an in vitro direct challenge method using abomasal tissue explants. Vet. Parasitol 2004, 124, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, A.; Rojo, R.; Zamilpa, A.; Mendoza, P.; Arece, J.; López, M.E.; von Son-de Fernex, E. In vitro larvicidal effect of a hydroalcoholic extract from Acacia cochliacantha leaf against ruminant parasitic nematodes. Vet. Res. Commun 2017, 41, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, S.; Skaletsky, H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol 2000, 132, 365–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerburg, B. G.; Singleton, G. R.; Kijlstra, A. Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health. Crit Rev Microbiol 2009, 35, 221–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čoklo, M.; Maslov, D.R.; Kraljević, S. Modulation of gut microbiota in healthy rats after exposure to nutritional supplements. Gut Microbes, 2020; 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.P.; McAllister, M.; Sandoz, M.; Kalmokoff, M.L. Culture-independent phylogenetic analysis of the faecal flora of the rat. Can. J. Microbiol 2003, 49, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, H.; Mao, B.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, W. Microbial Biogeography and Core Microbiota of the Rat Digestive Tract. Sci. Rep 2017, 4;8, 45840. Sci. Rep. [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Rodriguez, M.d.C.; Lanz, H.; Zhu, S. AdDLP, a bacterial defensin-like peptide, exhibits anti-Plasmodium activity. BBRC 2009, 387, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.M.; Nice, J.B.; Chang, E.H.; Brown, A.C. Size Exclusion Chromatography to Analyze Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicle Heterogeneity. Journal of Visualized Experiments. Vis Exp 2021, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, S.N.; Rimmer, M.A.; Turner, K.B.; Phillips, D.A.; Caruana, J.C.; Hervey, W. J 4th.; Leary, D.H.; Walper, SA. Lactobacillus acidophilus Membrane Vesicles as a Vehicle of Bacteriocin Delivery. Front. Microbiol 2020, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolin, W. FtsZ and the division of prokaryotic cells and organelles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2005, 6, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerl, C.; Coll, J. M.; Tarazona, C.; Pérez, G. Lactobacillus casei extracellular vesicles stimulate EGFR pathway likely due to the presence of proteins P40 and P75 bound to their surface. Sci. Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, M.; Ambalam, P.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Pithva, S.; Kothari, C.; Patel, A.T.; Purama, R.K.; Dave, J.M.; Vyas, B.R. Potential of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics for management of colorectal cancer. Gut Microbes 2013, 4, 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes I., J.; Schoofs, G.; Regulski, K.; Courtin, P.; Chapot, M.P.; Rolain, T.; Hols, P.; von Ossowski, I.; Reunanen, J.; de Vos, W.M.; Palva, A.; Vanderleyden, J.; De Keersmaecker, S.C.; Lebeer, S. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the cell wall hydrolase activity of the major secreted protein of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Teng, K.; Liu, Y. Bacteriocins: Potential for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2021, 10, 5518825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, R.; Cebrián, R.; Maqueda, M.; Romero, D.; Rosales, M.J.; Sánchez, M.; Marín, C. Assessing the effectiveness of AS-48 in experimental mice models of Chagas’ disease. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2020, 75, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puspitasari, S.; Farajallah, A.; Sulistiawati, E.; Muladno. Effectiveness of Ivermectin and Albendazole against Haemonchus contortus in Sheep in West Java, Indonesia. Trop. Life. Sci. Res 2016, 27, 135–44. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, M.; Kousheh, S.A.; Almasi, H.; Alizadeh, A.; Guimarães, J.T.; Yılmaz, N.; Lotfi, A. Postbiotics produced by lactic acid bacteria: The next frontier in food safety. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf 2020, 19, 3390–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Mardani, K.; Tajik, H. Characterization and application of postbiotics of Lactobacillus spp. on Listeria monocytogenes in vitro and in food models. LWT 2019, 111, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakovich, L. J.; Balskus, E. P. Metabolic functions of the human gut microbiota: The role of metalloenzymes. Nat. Prod. Rep 2019, 36, 593–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, G.; Lacroux, C.; Andreoletti, O.; Grisez, C.; Prevot, F.; Bergeaud, J.P.; Penicaud, J.; Rouillon, V.; Gruner, L.; Brunel, J.C.; Francois, D.; Bouix, J.; Dorchies, P.; Jacquiet, P. Immune response to Haemonchus contortus infection in susceptible (INRA 401) and resistant (Barbados Black Belly) breeds of lambs. Parasite Immunol 2007, 29, 415–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, E.; Greiner, S.P.; Russ, B.; Bowdridge, S.A. Interleukin-13 induces paralysis of Haemonchus contortus larvae in vitro. Parasite Immunol 2020, 42, e12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, H.V.; Umair, S.; Hoang, V.C.; Savoian, M.S. Histochemical study of the effects on abomasal mucins of Haemonchus contortus or Teladorsagia circumcincta infection in lambs. Vet. Parasitol 2016, 226, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.I.; Brackett, B.G.; Halper, J. Culture supernatant of Lactobacillus acidophilus stimulates proliferation of embryonic cells. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2005, 230, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, S.; Segura, I.; Olivares, P.J.; Almazán, M.T. Prevalencia de nematodos gastrointestinales en ovinos en pastoreo en la parte alta del MPIO. de Cuetzala del Progreso, Guerrero-México. Redvet 2007, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Solís, J.; Gaxiola, S.; Enríquez, I.; Portillo, J.; López, G.; Castro, N. Factores ambientales asociados a la prevalencia de Haemonchus spp en corderos de la zona centro de Sinaloa. Abanico veterinario 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Córdova, C.; Torres, G.; Mendoza, P.; Arece, J. Prevalencia de parásitos gastrointestinales en ovinos sacrificados en un rastro de Tabasco, México. Veterinaria México 2011, 42, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Balic. A.; Cunningham, C.P.; Meeusen, E.N. Eosinophil interactions with Haemonchus contortus larvae in the ovine gastrointestinal tract. Parasite Immunol 2006, 28, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J.M.; Robinson, N.A.; Meeusen, E.N.; Piedrafita, D.M. The relationship between the rapid rejection of Haemonchus contortus larvae with cells and mediators in abomasal tissues in immune sheep. Int. J. Parasitol 2009, 39, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Khan, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Nisar, A.; Feng, X. Suppression of hyaluronidase reduces invasion and establishment of Haemonchus contortus larvae in sheep. J. Vet. Res 2020, 51, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller. H.R.; Jackson. F.; Newlands. G.; Appleyard. W.T. Immune exclusion, a mechanism of protection against the ovine nematode Haemonchus contortus. Res. Vet. Sci 1983, 35, 357–363.

- Xiaoyan, X.; Hongxia, S.; Jiamin, G.; Huicheng, C.; Ye, L.; Qiang, X. Antimicrobial peptide HI-3 from Hermetia illucens alleviates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells via suppression of the nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway. Microbiol. Immunol 2023, 67, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Wasiliew, P.; Kracht, M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci. Signaling 2020, 105, cm1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T.N.; Leiman, S.A.; Kuehn, M.J. Naturally produced outer membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa elicit a potent innate immune response via combined sensing of both lipopolysaccharide and protein components. Infect. Immun 2010, 78, 3822–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briaud, P.; Carroll, R.K. Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Functions in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Infect Immun 2020, 88, e00433–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, C.A. Descripción general de la familia IL-1 en la inflamación innata y la inmunidad adquirida. Immunol. Rev 2018, 281, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, V.H.; Ishikawa, K.H.; Ando, E.S.; Bueno, B.; Nakamae, A.E.M.; Mayer, M.P.A. Probiotic Bacteria Alter Pattern-Recognition Receptor Expression and Cytokine Profile in a Human Macrophage Model Challenged with Candida albicans and Lipopolysaccharide. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, S.; Goto, H.; Maywood, Hirota, T. ; Fukuda, S.; Ohno, H.; Yamamoto, N. Lactobacillus acidophilus L-92 Cells Activate Expression of Immunomodulatory Genes in THP-1 Cells. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2014, 33, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, B.; Anh, P.T.N.; Yang, S.H. Enhancement of the anti-inflammatory effect of mustard kimchi on RAW 264.7 macrophages by the Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation-mediated generation of phenolic compound derivatives. Foods 2020, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G.; Sanders, M.E.; Salminen, S. The Concept of Postbiotics. Foods 2022, 11, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilingiri, K.; Barbosa, T.; Penna, G.; Caprioli, F.; Sonzogni, A.; Viale, G.; Rescigno, M. Probiotic and postbiotic activity in health and disease: comparison on a novel polarised ex-vivo organ culture model, Gut 2012, 61, 1007–1015. [CrossRef]

| Primer gene | Sequence [5’- 3’] | Alignment temperature | Length [bp] |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | FwGTGTGTGACGTTCCCATTA Rv CGTTGCTTGGTTCTCCTTGT | 62°C | 170 |

| TNF-α | FwTATGGCTCAGGGTCCAACTC Rv CTCCCTTTGCAGAACTCAGG | 62°C | 174 |

| HPRT1 | FwATTCCCAACAGACAGACAGACAGAA Rv TTAGGTCGGAAGGCATCAT | 50° C | 224 |

| Proteins | Fractions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | PM/ kDa |

FI MVs | FI WB | FI CFS | ATCC MVS | ATCC WB | ATCC CFS |

| p75 | 75 | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| FtsZ protein | 64 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ABC transporter ATP-binding and membrane spanning protein | 59 | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Glutamine ABC transporter permease protein glnP | 54 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| p40 | 40 | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Cell division protein DivIB | 32 | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Bacteriocin like proteins BLP | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | |

| 6 | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).