Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

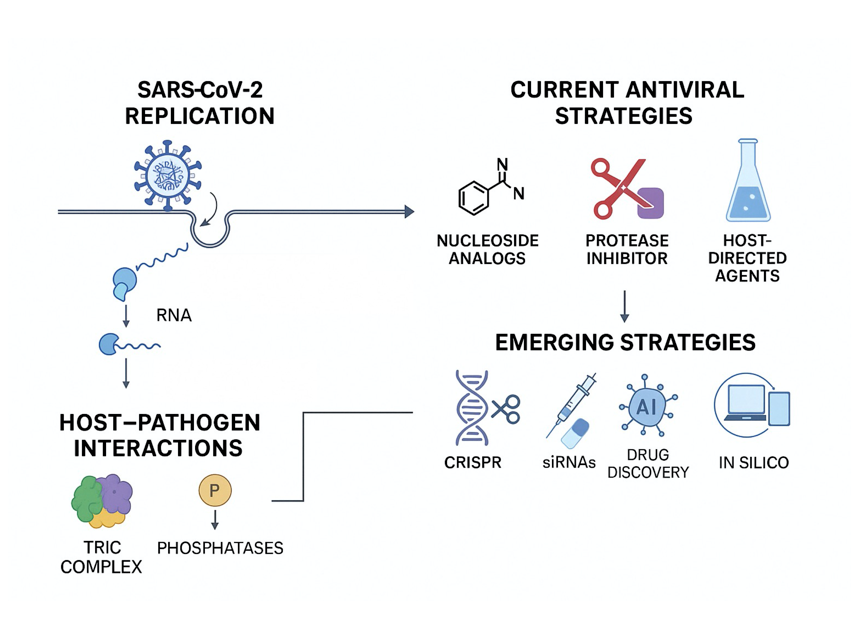

1. Introduction

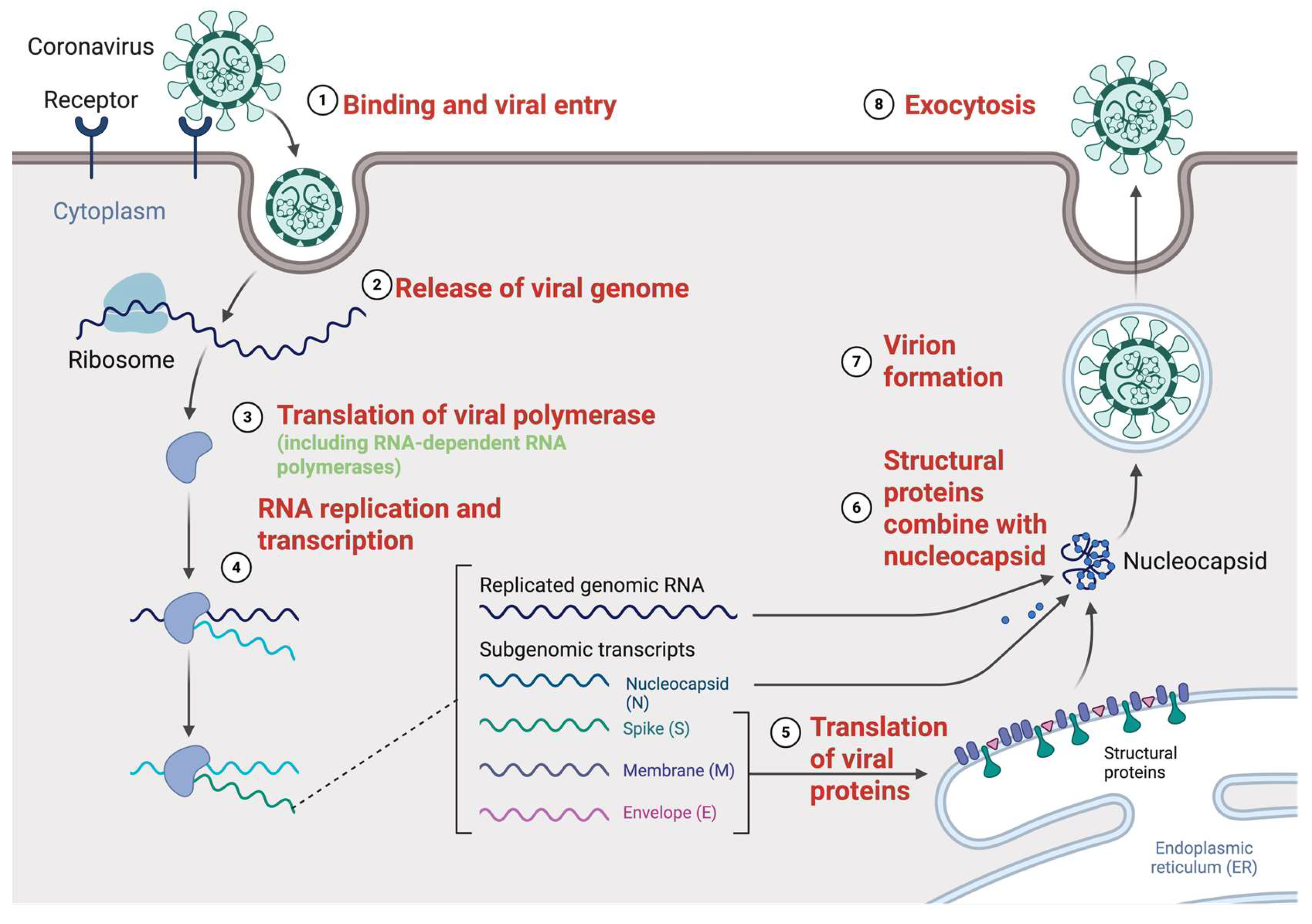

2. Molecular Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Replication

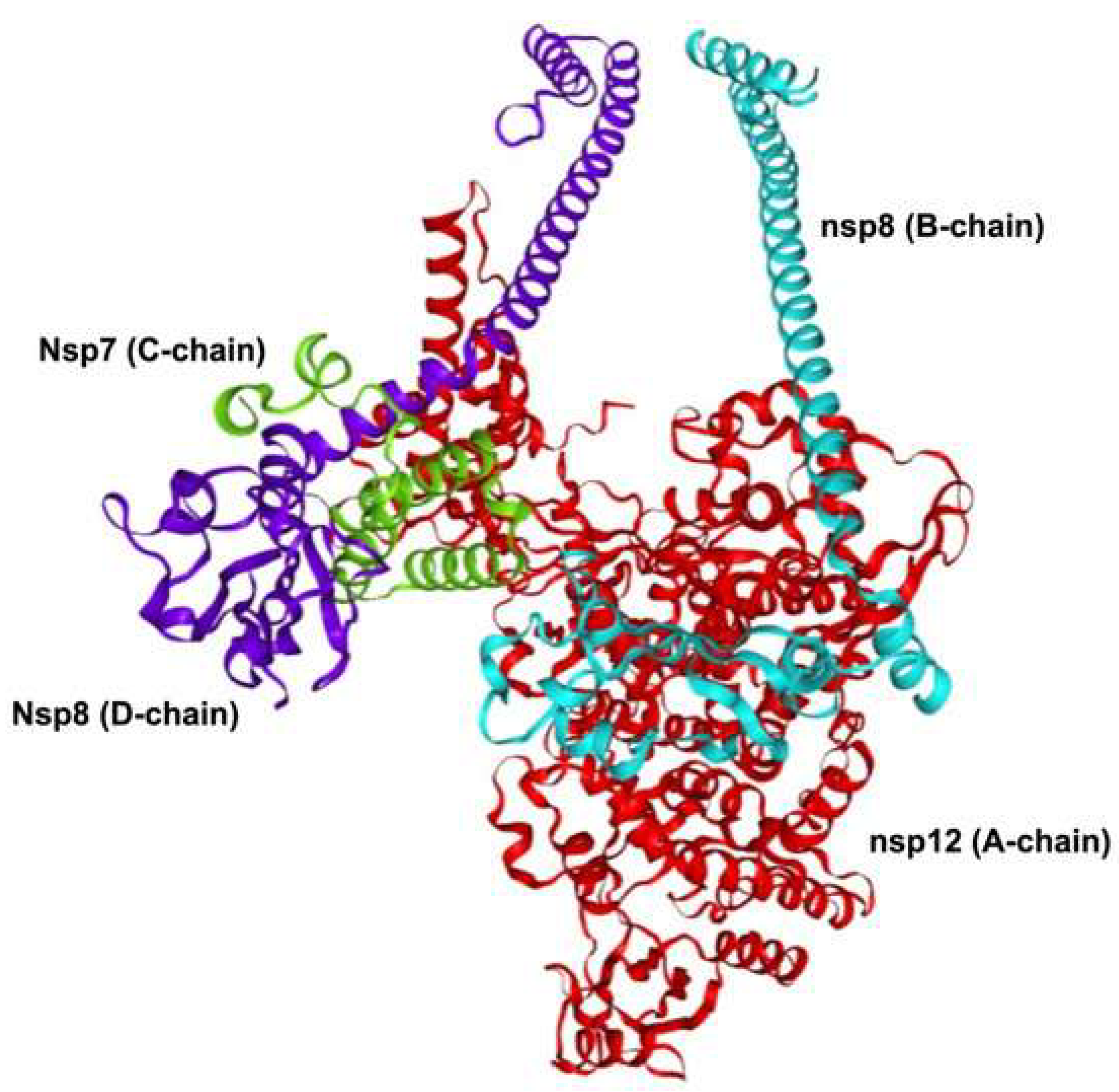

2.1. Replication Complex and Enzymatic Machinery

2.2. Genome Replication Cycle

2.3. Host Factors in Viral Replication

3. Drugs Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Replication

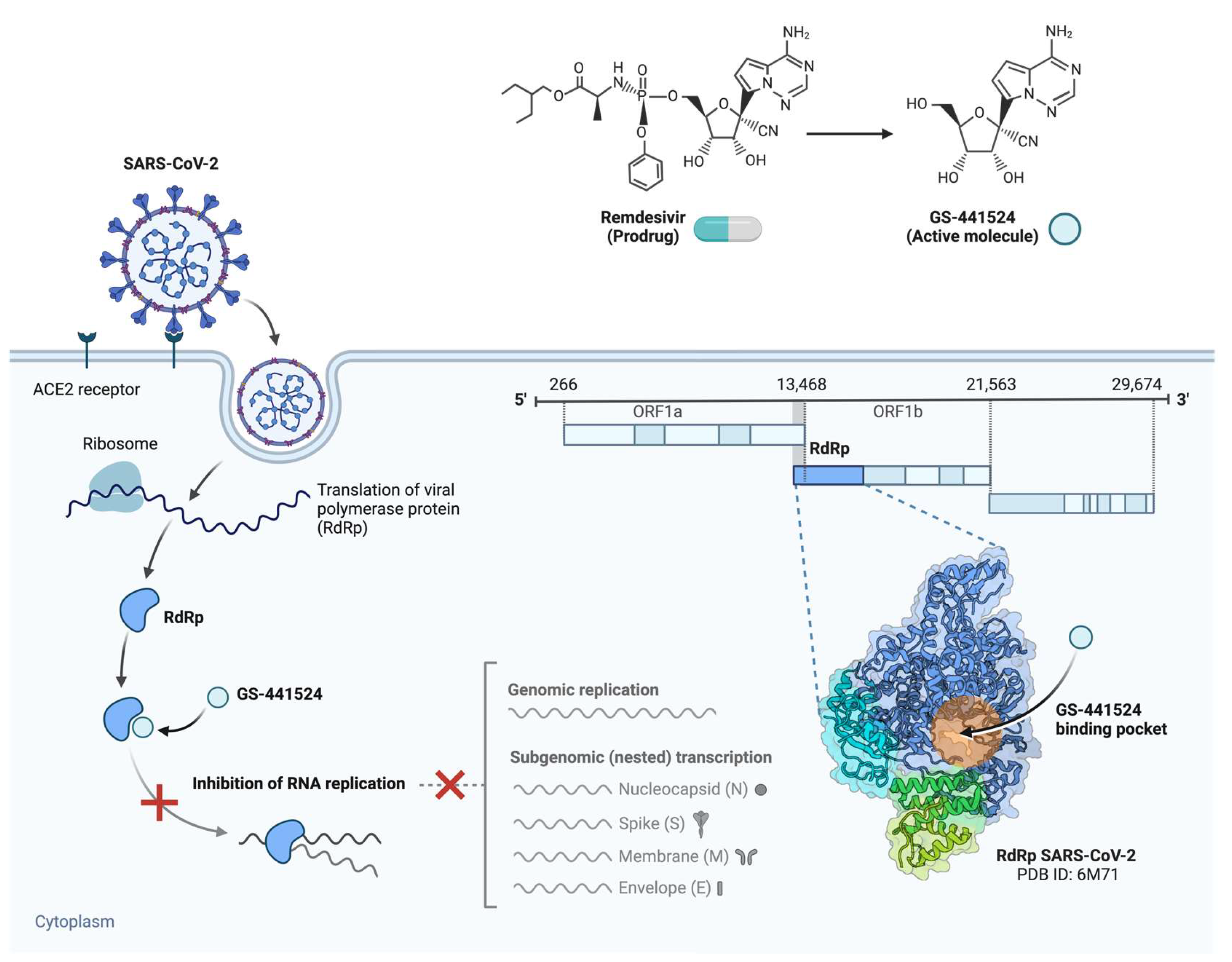

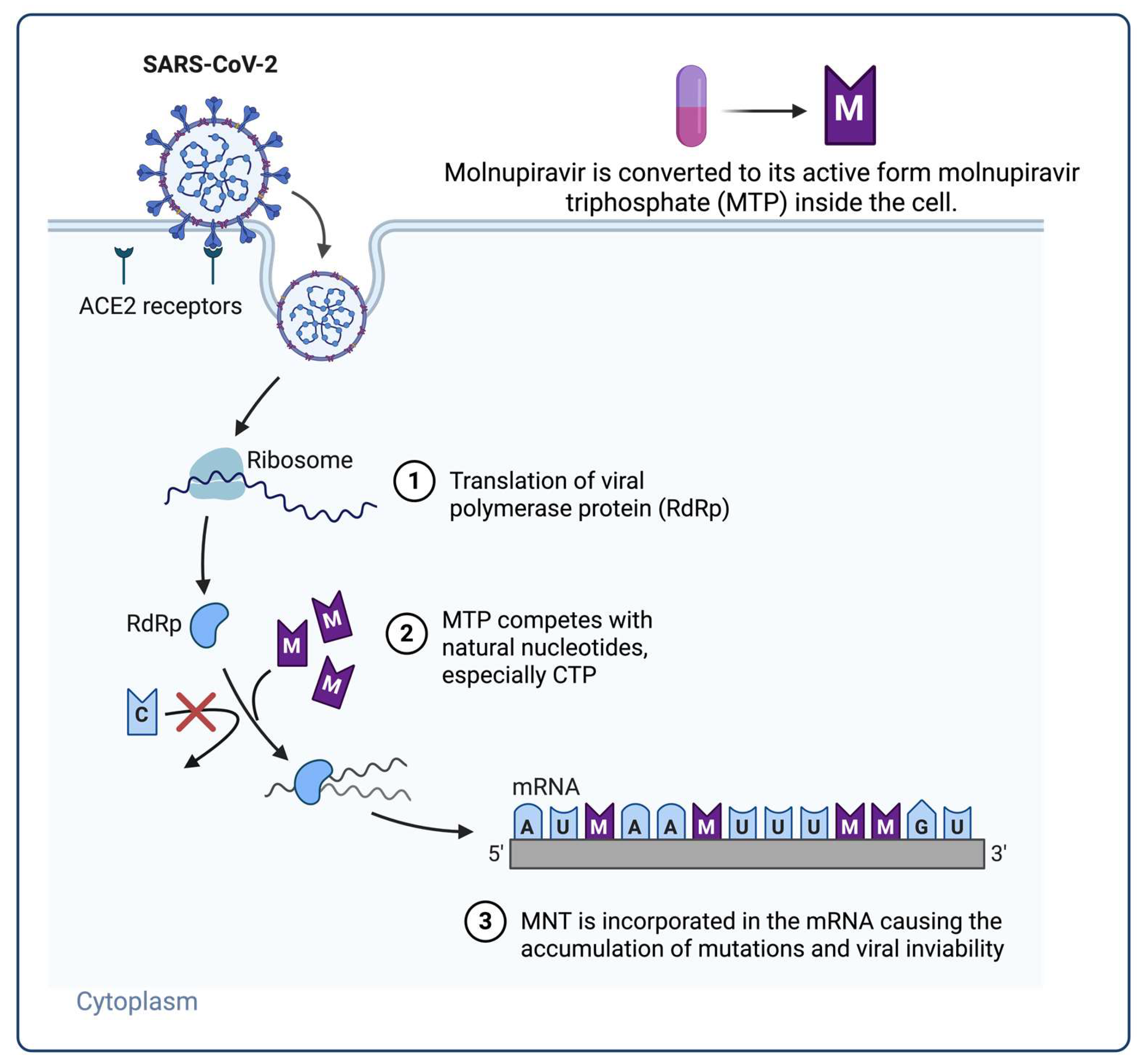

3.1. Nucleoside Analogue Polymerase Inhibitors

3.2. Protease Inhibitors

3.3. Host-Directed Antivirals

3.4. Combination Therapies and Drug Synergy

3.5. Antiviral Resistance Considerations

4. Future Trends and Emerging Antiviral Strategies

4.1. Novel Targets in the Viral Replication Cycle

4.2. Emerging and Novel Host-Directed Antivirals

4.3. AI and Computational Drug Discovery

4.4. Gene Silencing and RNA-Targeting Therapies

4.5. Pan-Coronavirus and Broad-Spectrum Antivirals

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, A.; Preiss, A.J.; Xiao, X.; Brannock, M.D.; Alexander, G.C.; Chew, R.F.; Fitzgerald, M.; Hill, E.; Kelly, E.P.; Mehta, H.B.; et al. Effect of Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (Paxlovid) on Hospitalization among Adults with COVID-19: An EHR-Based Target Trial Emulation from N3C. medRxiv 2023, 2023.05.03.23289084. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, H.M.N.; Katti, K.S.; Katti, D.R. Differences in Interactions Within Viral Replication Complexes of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and SARS-CoV Coronaviruses Control RNA Replication Ability. JOM (1989) 2021, 73, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Mao, C.; Luan, X.; Shen, D.-D.; Shen, Q.; Su, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, W.; Gao, M.; et al. Structural Basis for Inhibition of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase from SARS-CoV-2 by Remdesivir. Science 2020, 368, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, A.; Gulyaeva, A.A.; Brubacher, J.L.; Newmark, P.A.; Gorbalenya, A.E. A Planarian Nidovirus Expands the Limits of RNA Genome Size. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1007314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, P.J. An Introduction to Viruses of Invertebrates. In Encyclopedia of Virology; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 699–723 ISBN 978-0-12-814516-6.

- Bettini, A.; Lapa, D.; Garbuglia, A.R. Diagnostics of Ebola Virus. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1123024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, H.S. Structure and Function of SARS-CoV-2 Polymerase. Current Opinion in Virology 2021, 48, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrier, O.; Si-Tahar, M.; Ducatez, M.; Chevalier, C.; Pizzorno, A.; Le Goffic, R.; Crépin, T.; Simon, G.; Naffakh, N. Influenza Viruses and Coronaviruses: Knowns, Unknowns, and Common Research Challenges. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1010106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, A.; Singh, R.; Misra, A. Molnupiravir in COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Literature. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2021, 15, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wen, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, W.; Li, G.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, J.; Zhan, Y.; Su, Y.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir (Paxlovid)-Treated for COVID-19 Patients with Onset of More than 5 Days: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1401658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, A.A.T.; Fatima, K.; Mohammad, T.; Fatima, U.; Singh, I.K.; Singh, A.; Atif, S.M.; Hariprasad, G.; Hasan, G.M.; Hassan, Md. I. Insights into the SARS-CoV-2 Genome, Structure, Evolution, Pathogenesis and Therapies: Structural Genomics Approach. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2020, 1866, 165878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, A.C.; Tian, W.; Majerciak, V.; Yang, W.; Zheng, Z.-M. SARS-CoV-2: From Its Discovery to Genome Structure, Transcription, and Replication. Cell Biosci 2021, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillen, H.S. Structure and Function of SARS-CoV-2 Polymerase. Current Opinion in Virology 2021, 48, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polatoğlu, I.; Oncu-Oner, T.; Dalman, I.; Ozdogan, S. COVID-19 in Early 2023: Structure, Replication Mechanism, Variants of SARS-CoV-2, Diagnostic Tests, and Vaccine & Drug Development Studies. MedComm 2023, 4, e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggen, J.; Vanstreels, E.; Jansen, S.; Daelemans, D. Cellular Host Factors for SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nat Microbiol 2021, 6, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, X.; He, B.; Cheng, W. Structural Biology of SARS-CoV-2: Opening the Door for Novel Therapies. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-R.; Cao, Q.-D.; Hong, Z.-S.; Tan, Y.-Y.; Chen, S.-D.; Jin, H.-J.; Tan, K.-S.; Wang, D.-Y.; Yan, Y. The Origin, Transmission and Clinical Therapies on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak-an Update on the Status. Mil Med Res 2020, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An Overview of Their Replication and Pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1282, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subong, B.J.J.; Ozawa, T. Bio-Chemoinformatics-Driven Analysis of Nsp7 and Nsp8 Mutations and Their Effects on Viral Replication Protein Complex Stability. CIMB 2024, 46, 2598–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshamwala, S.M.S.; Likhite, V.; Degani, M.S.; Deb, S.S.; Noronha, S.B. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Nsp7 and Nsp8 Proteins and Their Predicted Impact on the Replication/Transcription Complex Structure. Journal of Medical Virology 2021, 93, 4616–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yan, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, T.; Sun, Q.; Ming, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase from COVID-19 Virus. Science 2020, 368, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, H.; Madhugiri, R.; Bylapudi, G.; Schultheiß, K.; Karl, N.; Gulyaeva, A.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Linne, U.; Ziebuhr, J. Coronavirus Replication–Transcription Complex: Vital and Selective NMPylation of a Conserved Site in Nsp9 by the NiRAN-RdRp Subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2022310118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickolajczyk, K.J.; Shelton, P.M.M.; Grasso, M.; Cao, X.; Warrington, S.E.; Aher, A.; Liu, S.; Kapoor, T.M. Force-Dependent Stimulation of RNA Unwinding by SARS-CoV-2 Nsp13 Helicase. Biophysical Journal 2021, 120, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Malone, B.; Llewellyn, E.; Pechersky, Y.; Maruthi, K.; Eng, E.T.; Perry, J.K.; Campbell, E.A.; Shaw, D.E.; et al. Ensemble Cryo-EM Reveals the Conformational States of the Nsp13 Helicase in the SARS-CoV-2 Helicase Replication–Transcription Complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2022, 29, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinthapatla, R.; Sotoudegan, M.; Srivastava, P.; Anderson, T.K.; Moustafa, I.M.; Passow, K.T.; Kennelly, S.A.; Moorthy, R.; Dulin, D.; Feng, J.Y.; et al. Interfering with Nucleotide Excision by the Coronavirus 3′-to-5′ Exoribonuclease. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Kong, F.; Hou, Y.J.; Wang, Q. Crucial Mutation in the Exoribonuclease Domain of Nsp14 of PEDV Leads to High Genetic Instability during Viral Replication. Cell Biosci 2021, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvet, M.; Lugari, A.; Posthuma, C.C.; Zevenhoven, J.C.; Bernard, S.; Betzi, S.; Imbert, I.; Canard, B.; Guillemot, J.-C.; Lécine, P.; et al. Coronavirus Nsp10, a Critical Co-Factor for the Activation of Multiple Replicative Enzymes. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 25783–25796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Rao, Z. Structural Biology of SARS-CoV-2 and its Implications for Therapeutic Development. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Cortese, M.; Winter, S.L.; Wachsmuth-Melm, M.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Cerikan, B.; Stanifer, M.L.; Boulant, S.; Bartenschlager, R.; Chlanda, P. SARS-CoV-2 Structure and Replication Characterized by in Situ Cryo-Electron Tomography. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, B.; Urakova, N.; Snijder, E.J.; Campbell, E.A. Structures and Functions of Coronavirus Replication–Transcription Complexes and Their Relevance for SARS-CoV-2 Drug Design. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.H.; Edgar, J.R.; Martello, A.; Ferguson, B.J.; Eden, E.R. Exploiting Connections for Viral Replication. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 640456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roingeard, P.; Eymieux, S.; Burlaud-Gaillard, J.; Hourioux, C.; Patient, R.; Blanchard, E. The Double-Membrane Vesicle (DMV): A Virus-Induced Organelle Dedicated to the Replication of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Positive-Sense Single-Stranded RNA Viruses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Yuan, S.; Ni, T. Molecular Architecture of the Coronavirus Double-Membrane Vesicle Pore Complex. Nature 2024, 633, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.M.; Chen, Y.-J.; Cho, W.J.; Tai, A.W.; Tsai, B. Reticulons Promote the Formation of ER-Derived Double-Membrane Vesicles That Facilitate SARS-CoV-2 Replication. Journal of Cell Biology 2023, 222, e202203060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeijer, M.C.; Monastyrska, I.; Griffith, J.; Van Der Sluijs, P.; Voortman, J.; Van Bergen En Henegouwen, P.M.; Vonk, A.M.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Reggiori, F.; De Haan, C.A.M. Membrane Rearrangements Mediated by Coronavirus Nonstructural Proteins 3 and 4. Virology 2014, 458–459, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandersen, S.; Chamings, A.; Bhatta, T.R. SARS-CoV-2 Genomic and Subgenomic RNAs in Diagnostic Samples Are Not an Indicator of Active Replication. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telwatte, S.; Martin, H.A.; Marczak, R.; Fozouni, P.; Vallejo-Gracia, A.; Kumar, G.R.; Murray, V.; Lee, S.; Ott, M.; Wong, J.K.; et al. Novel RT-ddPCR Assays for Measuring the Levels of Subgenomic and Genomic SARS-CoV-2 Transcripts. Methods 2022, 201, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, P.V.; Ghafari, M.; Beer, M.; Lythgoe, K.; Simmonds, P.; Stilianakis, N.I.; Katzourakis, A. The Evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, A.H.; Menzies, G.; Southgate, A.; Jones, D.D.; Connor, T.R. A Proofreading Mutation with an Allosteric Effect Allows a Cluster of SARS-CoV-2 Viruses to Rapidly Evolve. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2023, 40, msad209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prydz, K.; Saraste, J. The Life Cycle and Enigmatic Egress of Coronaviruses. Molecular Microbiology 2022, 117, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdikari, T.M.; Murthy, A.C.; Ryan, V.H.; Watters, S.; Naik, M.T.; Fawzi, N.L. SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Phase-separates with RNA and with Human hnRNPs. The EMBO Journal 2020, 39, e106478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, G.J.; Mears, H.V.; Broncel, M.; Snijders, A.P.; Bauer, D.L.V.; Carlton, J.G. ER-Export and ARFRP1/AP-1–Dependent Delivery of SARS-CoV-2 Envelope to Lysosomes Controls Late Stages of Viral Replication. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Hiatt, J.; Bouhaddou, M.; Rezelj, V.V.; Ulferts, S.; Braberg, H.; Jureka, A.S.; Obernier, K.; Guo, J.Z.; Batra, J.; et al. Comparative Host-Coronavirus Protein Interaction Networks Reveal Pan-Viral Disease Mechanisms. Science 2020, 370, eabe9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.; Wang, S.; Kwon, Y.; Reid, A.A.; Robison, R.; Shen, P.; Willardson, B. Folding of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA Polymerase by the Cytosolic Chaperonin CCT. The FASEB Journal 2022, 36, fasebj.2022–36.S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, M.; Armstrong, S.; Prince, T.; Erdmann, M.; Matthews, D.A.; Davidson, A.; Aljabr, W.; Hiscox, J.A. SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 Associates with the TRiC Complex and the P323L Substitution Is a Host Adaption 2023.

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Hou, Y.; Ye, S.; Sha, T.; Su, Y.; Zhao, W.; Bao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Chen, H. Ongoing Natural Selection Drives the Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Genomes 2020.

- Shi, J.; Du, T.; Wang, J.; Tang, C.; Lei, M.; Yu, W.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, P.; Chen, H.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Is a Proviral Host Factor and a Candidate Pan-SARS-CoV-2 Therapeutic Target. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf0211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Pu, Y.; Yuan, S.; Pache, L.; Churas, C.; Weston, S.; Riva, L.; Simons, L.M.; Cisneros, W.; Clausen, T.; et al. Global siRNA Screen Reveals Critical Human Host Factors of SARS-CoV-2 Multicycle Replication 2024.

- Jockusch, S.; Tao, C.; Li, X.; Anderson, T.K.; Chien, M.; Kumar, S.; Russo, J.J.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Ju, J. A Library of Nucleotide Analogues Terminate RNA Synthesis Catalyzed by the Polymerases of Coronaviruses That Cause SARS and COVID-19. Antiviral Research 2020, 180, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; De Clercq, E. Therapeutic Options for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020, 19, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigel, J.H.; Tomashek, K.M.; Dodd, L.E.; Mehta, A.K.; Zingman, B.S.; Kalil, A.C.; Hohmann, E.; Chu, H.Y.; Luetkemeyer, A.; Kline, S.; et al. Remdesivir for Treating COVID-19 — Final Report. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olender, S.A.; Perez, K.K.; Go, A.S.; Balani, B.; Price-Haywood, E.G.; Shah, N.S.; Wang, S.; Walunas, T.L.; Swaminathan, S.; Slim, J.; et al. Remdesivir for Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Versus a Cohort Receiving Standard of Care. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 73, e4166–e4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogando, N.S.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Van Der Meer, Y.; Bredenbeek, P.J.; Posthuma, C.C.; Snijder, E.J. The Enzymatic Activity of the Nsp14 Exoribonuclease Is Critical for the Replication of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. J Virol 2020, 94, e01246–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.-Y.; Lahser, F.; Warren, C.; He, X.; Murray, E.; Wang, D. The Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Nsp14 Proofreading on Nucleoside Antiviral Activity: Insights from Genetic and Pharmacological Investigations 2024.

- Lee, C.-C.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Ko, W.-C. Molnupiravir—A Novel Oral Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Agent. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabinger, F.; Stiller, C.; Schmitzová, J.; Dienemann, C.; Kokic, G.; Hillen, H.S.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P. Mechanism of Molnupiravir-Induced SARS-CoV-2 Mutagenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2021, 28, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Pang, Z.; Li, M.; Lou, F.; An, X.; Zhu, S.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H.; Fan, J. Molnupiravir and Its Antiviral Activity Against COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 855496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, B.; Campbell, E.A. Molnupiravir: Coding for Catastrophe. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2021, 28, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masyeni, S.; Iqhrammullah, M.; Frediansyah, A.; Nainu, F.; Tallei, T.; Emran, T.B.; Ophinni, Y.; Dhama, K.; Harapan, H. Molnupiravir: A Lethal Mutagenic Drug against Rapidly Mutating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2—A Narrative Review. 4.4 Journal of Medical Virology 2022, 94, 3006–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraco, Y.; Crofoot, G.E.; Moncada, P.A.; Galustyan, A.N.; Musungaie, D.B.; Payne, B.; Kovalchuk, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Brown, M.L.; Williams-Diaz, A.; et al. Phase 2/3 Trial of Molnupiravir for Treatment of COVID-19 in Nonhospitalized Adults. NEJM Evidence 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizki, J.M.; Gaspar, J.M.; Howe, J.A.; Hutchins, B.; Mohri, H.; Nair, M.S.; Kinek, K.C.; McKenna, P.; Goh, S.L.; Murgolo, N. Molnupiravir Maintains Antiviral Activity against SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Exhibits a High Barrier to the Development of Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2024, 68, e00953–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, H.A.; Korkmaz Ekren, P.; Çağlayan, D.; Işikgöz Taşbakan, M.; Yamazhan, T.; Taşbakan, M.S.; Sayiner, A.; Gökengi̇N, D. Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia with Favipiravir: Early Results from the Ege University Cohort, Turkey. Turk J Med Sci 2021, 51, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemnejad-Berenji, M.; Pashapour, S. Favipiravir and COVID-19: A Simplified Summary. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2021, 71, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, T.; Kambayashi, D.; Akatsu, H.; Kudo, K. Favipiravir for the Treatment of Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2021, 21, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, S.; Nielsen, E.E.; Feinberg, J.; Siddiqui, F.; Jørgensen, C.K.; Barot, E.; Holgersson, J.; Nielsen, N.; Bentzer, P.; Veroniki, A.A.; et al. Interventions for the Treatment of COVID-19: Second Edition of a Living Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses and Trial Sequential Analyses (The LIVING Project). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D.B.; Budhathoki, P.; Khadka, S.; Shah, P.B.; Pokharel, N.; Rashmi, P. Favipiravir versus Other Antiviral or Standard of Care for COVID-19 Treatment: A Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Virol J 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.; Su, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Jiang, J. Ribavirin Therapy for Severe COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2020, 56, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, E.; Danise, A.; Ferrari, G.; Andolina, A.; Chiurlo, M.; Razanakolona, M.; Barakat, M.; Israel, R.J.; Castagna, A. Ribavirin Aerosol for treating SARS-CoV-2: A Case Series. Infect Dis Ther 2021, 10, 2791–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liang, L.; Cao, Y.; Duan, H.; Tian, G.; Ma, J.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of VV116, an Oral Nucleoside Analog against SARS-CoV-2, in Chinese Healthy Subjects. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2022, 43, 3130–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Huang, X.; Kang, X.; Zang, W.; Li, B.; Kiselev, S. The Safety and Efficacy of the Oral Antiviral Drug VV116 for the Treatment of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Medicine 2023, 102, e34105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.W. VV116 as a Potential Treatment for COVID-19. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2023, 24, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Baniecki, M.; Hendrick, V.M.; Damle, B.; Simón-Campos, A.; et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, M.; Vakil, M.K.; Bahmanyar, M.; Zarenezhad, E. Paxlovid: Mechanism of Action, Synthesis, and In Silico Study. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022, 7341493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzolini, C.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Marra, F.; Boyle, A.; Gibbons, S.; Flexner, C.; Pozniak, A.; Boffito, M.; Waters, L.; Burger, D.; et al. Recommendations for the Management of Drug–Drug Interactions Between the COVID -19 Antiviral Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (Paxlovid) and Comedications. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 2022, 112, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gammeltoft, K.A.; Ryberg, L.A.; Pham, L.V.; Fahnøe, U.; Binderup, A.; Hernandez, C.R.D.; Offersgaard, A.; Fernandez-Antunez, C.; Peters, G.H.J.; et al. Nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 Variants with High Fitness in Vitro 2022.

- Iketani, S.; Mohri, H.; Culbertson, B.; Hong, S.J.; Duan, Y.; Luck, M.I.; Annavajhala, M.K.; Guo, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Uhlemann, A.-C.; et al. Multiple Pathways for SARS-CoV-2 Resistance to Nirmatrelvir 2022.

- Costacurta, F.; Dodaro, A.; Bante, D.; Schöppe, H.; Peng, J.-Y.; Sprenger, B.; He, X.; Moghadasi, S.A.; Egger, L.M.; Fleischmann, J.; et al. A Comprehensive Study of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) Inhibitor-Resistant Mutants Selected in a VSV-Based System. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, G.; Ruan, L.; Song, B.; Cai, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. A Trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, T.; Nobori, H.; Fukao, K.; Baba, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Yoshida, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Watari, R.; Oka, R.; Kasai, Y.; et al. Efficacy Comparison of the 3CL Protease Inhibitors Ensitrelvir and Nirmatrelvir against SARS-CoV-2 in Vitro and in Vivo. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2023, 78, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnsey, M.R.; Robinson, M.C.; Nguyen, L.T.; Cardin, R.; Tillotson, J.; Mashalidis, E.; Yu, A.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Balesano, A.; Behzadi, A.; et al. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 Papain-like Protease (PLpro ) Inhibitors with Efficacy in a Murine Infection Model. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Săndulescu, O.; Apostolescu, C.G.; Preoțescu, L.L.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Săndulescu, M. Therapeutic Developments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection—Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Antivirals and Strategies for Mitigating Resistance in Emerging Variants in Clinical Practice. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1132501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, S.; Einav, S. Old Drugs for a New Virus: Repurposed Approaches for Combating COVID-19. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 2304–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunotte, L.; Zheng, S.; Mecate-Zambrano, A.; Tang, J.; Ludwig, S.; Rescher, U.; Schloer, S. Combination Therapy with Fluoxetine and the Nucleoside Analog GS-441524 Exerts Synergistic Antiviral Effects against Different SARS-CoV-2 Variants In Vitro. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (Previously 2019-nCoV) Infection by a Highly Potent Pan-Coronavirus Fusion Inhibitor Targeting Its Spike Protein That Harbors a High Capacity to Mediate Membrane Fusion. Cell Res 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Duan, X.; Men, K. Small Molecules for treating COVID-19. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.; Chokkakula, S.; Jeong, J.H.; Baek, Y.H.; Song, M.-S. SARS-CoV-2 Drug Resistance and Therapeutic Approaches. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, L.; Abarikwu, S.O.; Arero, A.G.; Essouma, M.; Jibril, A.T.; Fal, A.; Flisiak, R.; Makuku, R.; Marquez, L.; Mohamed, K.; et al. Oral Antiviral Treatments for COVID-19: Opportunities and Challenges. Pharmacol. Rep 2022, 74, 1255–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidari, A.; Sabbatini, S.; Schiaroli, E.; Bastianelli, S.; Pierucci, S.; Busti, C.; Saraca, L.M.; Capogrossi, L.; Pasticci, M.B.; Francisci, D. Synergistic Activity of the Remdesivir–Nirmatrelvir Combination in a SARS-CoV-2 In Vitro Model and a Case Report. Viruses 2023, 15, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidari, A.; Sabbatini, S.; Schiaroli, E.; Bastianelli, S.; Pierucci, S.; Busti, C.; Comez, L.; Libera, V.; Macchiarulo, A.; Paciaroni, A.; et al. The Combination of Molnupiravir with Nirmatrelvir or GC376 Has a Synergic Role in the Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Replication In Vitro. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodall, M.; Ellis, S.; Zhang, S.; Kembou-Ringert, J.; Kite, K.-A.; Buggiotti, L.; Jacobs, A.I.; Agyeman, A.A.; Masonou, T.; Palor, M.; et al. Efficient in Vitro Assay for Evaluating Drug Efficacy and Synergy against Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2025, 69, e01233–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Crespo, C.; De Ávila, A.I.; Gallego, I.; Soria, M.E.; Durán-Pastor, A.; Somovilla, P.; Martínez-González, B.; Muñoz-Flores, J.; Mínguez, P.; Salar-Vidal, L.; et al. Synergism between Remdesivir and Ribavirin Leads to SARS-CoV-2 Extinction in Cell Culture. British J Pharmacology 2024, 181, 2636–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, F.; Khan, K.S.; Le, T.K.; Paris, C.; Demirbag, S.; Barfuss, P.; Rocchi, P.; Ng, W.-L. Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting. Molecular Cell 2020, 79, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.N.D.; Abdelnabi, R.; Boda, B.; Constant, S.; Neyts, J.; Jochmans, D. The Triple Combination of Remdesivir (GS-441524), Molnupiravir, and Ribavirin Is Highly Efficient in Inhibiting Coronavirus Replication in Human Nasal Airway Epithelial Cell Cultures and in a Hamster Infection Model. Antiviral Research 2024, 231, 105994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, J.; Engler, O.; Rothenberger, S. Antiviral Efficacy of Ribavirin and Favipiravir against Hantaan Virus. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagoner, J.; Herring, S.; Hsiang, T.-Y.; Ianevski, A.; Biering, S.B.; Xu, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Pöhlmann, S.; Gale, M.; Aittokallio, T.; et al. Combinations of Host- and Virus-Targeting Antiviral Drugs Confer Synergistic Suppression of SARS-CoV-2. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e03331–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.M.; Schiffer, J.T.; Bender Ignacio, R.A.; Xu, S.; Kainov, D.; Ianevski, A.; Aittokallio, T.; Frieman, M.; Olinger, G.G.; Polyak, S.J. Drug Combinations as a First Line of Defense against Coronaviruses and Other Emerging Viruses. mBio 2021, 12, e03347–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Chokkakula, S.; Min, S. C.; Kim, B.K.; Choi, W.-S.; Oh, S.; Yun, Y.S.; Kang, D.H.; Lee, O. J.; Kim, E.-G.; et al. Combination Therapy with Nirmatrelvir and Molnupiravir Improves the Survival of SARS-CoV-2 Infected Mice. Antiviral Research 2022, 208, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahendran, T.R.; Cynthia, B.; Thevendran, R.; Maheswaran, S. Prospects of Innovative Therapeutics in Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mol Biotechnol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaziz, L.; Elhadi, E.; Abdallah, E.A.; Alnoor, F.A.; Yousef, B.A. Antiviral Activity of Approved Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antiprotozoal and Anthelmintic Drugs: Chances for Drug Repurposing for Antiviral Drug Discovery. JEP 2022, Volume 14, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.; Mäser, P.; Mahmoud, A.B. Drug Repurposing in the Chemotherapy of Infectious Diseases. Molecules 2024, 29, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Thakur, S.S. Remdesivir and Its Combination With Repurposed Drugs as COVID-19 Therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 830990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, M.; Hermán, L.; Réthelyi, J.M.; Bálint, B.L. Potential Role of the Antidepressants Fluoxetine and Fluvoxamine for treating COVID-19. IJMS 2022, 23, 3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajeri, H.; Baroun, F.; Abutiban, F.; Al-Mutairi, M.; Ali, Y.; Alawadhi, A.; Albasri, A.; Aldei, A.; AlEnizi, A.; Alhadhood, N.; et al. Therapeutic Role of Immunomodulators during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Narrative Review. Postgraduate Medicine 2022, 134, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, S.C.J.; Tse, C.L.Y.; Burry, L.; Dresser, L.D. Baricitinib: A Review of Pharmacology, Safety, and Emerging Clinical Experience in COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediansyah, A.; Tiwari, R.; Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Harapan, H. Antivirals for COVID-19: A Critical Review. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2021, 9, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, T.G.; Abril, A.G.; Sánchez, S.; De Miguel, T.; Sánchez-Pérez, A. Animal and Human RNA Viruses: Genetic Variability and the Ability to Overcome Vaccines. Arch Microbiol 2021, 203, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkmahomed, L.; Carbonneau, J.; Du Pont, V.; Riola, N.C.; Perry, J.K.; Li, J.; Paré, B.; Simpson, S.M.; Smith, M.A.; Porter, D.P.; et al. In Vitro Selection of Remdesivir-Resistant SARS-CoV-2 Demonstrates High Barrier to Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e00198–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szemiel, A.M.; Merits, A.; Orton, R.J.; MacLean, O.A.; Pinto, R.M.; Wickenhagen, A.; Lieber, G.; Turnbull, M.L.; Wang, S.; Furnon, W.; et al. In Vitro Selection of Remdesivir Resistance Suggests the Evolutionary Predictability of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, T.; Hisner, R.; Donovan-Banfield, I.; Hartman, H.; Løchen, A.; Peacock, T.P.; Ruis, C. A Molnupiravir-Associated Mutational Signature in the Global SARS-CoV-2 Genomes. Nature 2023, 623, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; He, G.; Huang, W. A Novel Model of Molnupiravir against SARS-CoV-2 Replication: Accumulated RNA Mutations to Induce Error Catastrophe. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.T.; Yang, Q.; Gribenko, A.; Perrin, B.S.; Zhu, Y.; Cardin, R.; Liberator, P.A.; Anderson, A.S.; Hao, L. Genetic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Reveals High Sequence and Structural Conservation before the Introduction of Protease Inhibitor Paxlovid. mBio 2022, 13, e00869–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; Deeks, S.G. Mechanisms of Long COVID and the Path toward Therapeutics. Cell 2024, 187, 5500–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupașcu (Moisi), R.E.; Ilie, M.I.; Velescu, B. Ștefan; Udeanu, D.I.; Sultana, C.; Ruță, S.; Arsene, A.L. COVID-19-Current Therapeutical Approaches and Future Perspectives. Processes 2022, 10, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chala, B.; Tilaye, T.; Waktole, G. Re-Emerging COVID-19: Controversy of Its Zoonotic Origin, Risks of Severity of Reinfection and Management. IJGM 2023, Volume 16, 4307–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zheng, M.; Gao, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhu, H.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y. Overview of Host-Directed Antiviral Targets for Future Research and Drug Development. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2025, S2211383525001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, M.; Zarganes-Tzitzikas, T.; Bennett, J.; De Cesco, S.; Fearon, D.; Von Delft, F.; Fedorov, O.; Brennan, P.E.; Ahel, I. Discovery and Development Strategies for SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 Macrodomain Inhibitors. Pathogens 2023, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petushkova, A.I.; Zamyatnin, A.A. Papain-Like Proteases as Coronaviral Drug Targets: Current Inhibitors, Opportunities, and Limitations. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, M.; Damalanka, V.C.; Tartell, M.A.; Chung, D.H.; Lourenço, A.L.; Pwee, D.; Mayer Bridwell, A.E.; Hoffmann, M.; Voss, J.; Karmakar, P.; et al. A Novel Class of TMPRSS2 Inhibitors that Potently Block SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV Viral Entry and Protect Human Epithelial Lung Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2108728118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, W. Heat Shock Proteins and Viral Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 947789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramaratne, A.C.; Wickner, S.; Kravats, A.N. Hsp90, a Team Player in Protein Quality Control and the Stress Response in Bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2024, 88, e00176–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, T.; Song, M.; Jin, M.; Liu, S.; Guo, K.; Zhang, Y. Rab1b-GBF1-ARFs Mediated Intracellular Trafficking Is Required for Classical Swine Fever Virus Replication in Swine Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Veterinary Microbiology 2020, 246, 108743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhoune, L.; Poggi, C.; Moreau, J.; Dubucquoi, S.; Hachulla, E.; Collet, A.; Launay, D. JAK Inhibitors (JAKi): Mechanisms of Action and Perspectives in Systemic and Autoimmune Diseases. La Revue de Médecine Interne 2025, 46, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeifian, F.; Nikfarjam, M.; Kian, N.; Mohamed, K.; Rezaei, N. The Role of Type I Interferon for treating COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology 2022, 94, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savan, R.; Gale, M. Innate Immunity and Interferon in the SARS-CoV-2 Infection Outcome. Immunity 2023, 56, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floresta, G.; Zagni, C.; Gentile, D.; Patamia, V.; Rescifina, A. Artificial Intelligence Technologies for COVID-19 De Novo Drug Design. IJMS 2022, 23, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodera, J.; Lee, A.A.; London, N.; Von Delft, F. Crowdsourcing Drug Discovery for Pandemics. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 581–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Badshah, S.L.; Kubra, B.; Sharaf, M.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M.; Abdalla, M. Computational Study of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Dependent RNA Polymerase Allosteric Site Inhibition. Molecules 2021, 27, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Yang, S.; He, S.; Li, F. AI Drug Discovery Tools and Analysis Technology: New Methods Aid in Studying the Compatibility of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Pharmacological Research-Modern Chinese Medicine 2025, 14, 100566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, S.; Taghavi Shahraki, B.; Rameh, F.; Nazarabi, M.; Fatahi, Y.; Akhavan, O.; Rabiee, M.; Mostafavi, E.; Lima, E.C.; Saeb, M.R.; et al. A Review on Computer-aided Chemogenomics and Drug Repositioning for Rational COVID -19 Drug Discovery. Chem Biol Drug Des 2022, 100, 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottaqi, M.S.; Mohammadipanah, F.; Sajedi, H. Contribution of Machine Learning Approaches in Response to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2021, 23, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, A.; Thakur, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Kamboj, S.; Rastogi, A.; Gautam, S.; Jassal, H.; Kumar, M. Prediction of Repurposed Drugs for Coronaviruses Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2021, 19, 3133–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchting, J. Targeting Viral Genome Synthesis as a Broad-Spectrum Approach against RNA Virus Infections. Antivir Chem Chemother 2020, 28, 204020662097678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolksdorf, B.; Heinze, J.; Niemeyer, D.; Röhrs, V.; Berg, J.; Drosten, C.; Kurreck, J. Development of a Highly Stable, Active Small Interfering RNA with Broad Activity against SARS-CoV Viruses. Antiviral Research 2024, 226, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, T.R.; Dhamdhere, G.; Liu, Y.; Lin, X.; Goudy, L.; Zeng, L.; Chemparathy, A.; Chmura, S.; Heaton, N.S.; Debs, R.; et al. Development of CRISPR as an Antiviral Strategy to Combat SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza. Cell 2020, 181, 865–876.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Qi, H.; Cui, W.; Zhang, L.; Fu, X.; He, X.; Liu, M.; Li, P.; Yu, T. CRISPR/Cas9 Therapeutics: Progress and Prospects. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, S.; Tan, S.C.; Aghamiri, S.; Raee, P.; Ebrahimi, Z.; Jahromi, Z.K.; Rahmati, Y.; Sadri Nahand, J.; Piroozmand, A.; Jajarmi, V.; et al. Therapeutic Potentials of the CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing Technology in Human Viral Infections. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2022, 148, 112743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Delft, A.; Hall, M.D.; Kwong, A.D.; Purcell, L.A.; Saikatendu, K.S.; Schmitz, U.; Tallarico, J.A.; Lee, A.A. Accelerating Antiviral Drug Discovery: Lessons from COVID-19. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2023, 22, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, A.; Ludwig, S. Host-Targeted Antivirals against SARS-CoV-2 in Clinical Development-Prospect or Disappointment? Antiviral Research 2025, 235, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seley-Radtke, K.L.; Thames, J.E.; Waters, C.D. Broad Spectrum Antiviral Nucleosides—Our Best Hope for the Future. In Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry; Elsevier, 2021; Vol. 57, pp. 109–132 ISBN 978-0-323-91511-3.

- Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Ward, A.B. Structure of the SARS-CoV Nsp12 Polymerase Bound to the Nsp7 and Nsp8 Co-Factors. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, R.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Shang, W.; Jiang, X.; et al. Novel and Potent Inhibitors Targeting DHODH Are Broad-Spectrum Antivirals against RNA Viruses, Including the Newly-Emerged Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Protein Cell 2020, 11, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, B.L.; Cheng, M.T.K.; Csiba, K.; Meng, B.; Gupta, R.K. SARS-CoV-2 and Innate Immunity: The Good, the Bad, and the “Goldilocks. ” Cell Mol Immunol 2023, 21, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiya, J.; Bhavsar, T.; Černý, J. Assessment and Strategy Development for SARS-CoV-2 Screening in Wildlife: A Review. Vet World 2023, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.; Lo, C.-W.; Einav, S. Preparing for the next Viral Threat with Broad-Spectrum Antivirals. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2023, 133, e170236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug/Compound | Target/Mechanism | Drug Class | Mode of Action | Clinical Use/Efficacy | Resistance/Limitations |

| Remdesivir | RdRp (nsp12) | Nucleoside analogue | Adenosine analogue; chain termination via delayed RNA translocation | IV use; moderately accelerates recovery in hospitalized patients | Partial resistance via nsp12 mutations (e.g., V166, E802); fitness cost limits spread |

| Molnupiravir | RdRp | Nucleoside analogue | Cytidine/uridine analogue; induces lethal mutagenesis | Oral use; reduces hospitalization in mild-to-moderate cases | Theoretical mutagenic risks; not fully neutralized by proofreading |

| Favipiravir | RdRp | Nucleoside analogue | Purine analogue; weak RNA synthesis inhibition | Limited effect; not a frontline drug | Requires high concentrations; inconsistent trial results |

| Ribavirin | RdRp | Nucleoside analogue | Guanosine analogue; promotes mutagenesis | Alone: limited effect; synergistic in combinations | High toxicity; synergizes with remdesivir |

| VV116 (Deuviridine) | RdRp | Nucleoside analogue | Oral prodrug of GS-441524 | Comparable to Paxlovid in trials; high bioavailability | Not widely approved |

| Nirmatrelvir + Ritonavir (Paxlovid) | 3CLpro | Protease inhibitor | Blocks polyprotein cleavage; halts replication complex maturation | Oral use; ~89% reduction in hospitalization if early | Resistance via 3CLpro mutations (in vitro); clinical relevance not yet clear |

| Ensitrelvir | 3CLpro | Protease inhibitor | Similar to nirmatrelvir | Effective in Japan trials | Investigational |

| Lopinavir + Ritonavir | 3CLpro | Protease inhibitor | HIV protease inhibitor; weak SARS-CoV-2 activity | No benefit in early COVID-19 trials | Largely abandoned |

| GRL-0617 | PLpro | Protease inhibitor | Preclinical inhibitor of papain-like protease | Preclinical stage | Not clinically available |

| Fluoxetine | Host (cell pathways) | SSRI / host-directed | Synergistic with GS-441524; may block viral egress | In vitro synergy with remdesivir | Lysosomotropic mechanism; repurposed drug |

| Itraconazole | Host (cholesterol trafficking) | Antifungal / host-directed | Disrupts sterol trafficking needed for replication | Enhances remdesivir efficacy in vitro | Repurposed, not virus-specific |

| Baricitinib | Host (JAK/STAT + endocytosis) | JAK inhibitor/immunomodulator | Blocks cytokine storm; may block viral entry | EUA with remdesivir; reduces inflammation | Minor antiviral activity; adjunctive |

| Camostat | TMPRSS2 | Host entry inhibitor | Blocks spike protein priming | In vitro efficacy; used in combinations | Investigational |

| Brequinar | DHODH (pyrimidine synthesis) | Host-targeting | Reduces the nucleotide pools needed for RNA synthesis | Strong synergy with molnupiravir | Host toxicity concerns |

| Remdesivir + Nirmatrelvir | RdRp + 3CLpro | Antiviral synergy | Blocks RNA synthesis and protein processing | Superior in vitro and in case reports | Dual targeting reduces the resistance potential |

| Remdesivir + Ribavirin | RdRp | Chain terminator + mutagen | Complete viral extinction in vitro | Enhances the mutational burden and replication block | Not in clinical use |

| Molnupiravir + Nirmatrelvir | RdRp + 3CLpro | Dual-action antiviral | Polymerase + protease inhibition | Enhanced synergy; potential for resistant strains | Preclinical and early trial stages |

| Molnupiravir + Camostat + Brequinar | Multi-target | Polymerase + entry + nucleotide synthesis | Maximal suppression in vitro | For persistent/resistant infections | Not tested clinically |

| Strategy | Targets/Approaches | Key Compounds/Tools | Potential Impact |

| Novel Viral Targets | nsp14 exonuclease (ExoN), the NiRAN domain of nsp12, PLpro, and macrodomains | PLpro inhibitors (e.g., GRL-0617), and experimental NiRAN inhibitors | Enhances polymerase inhibitor efficacy; reduces immune suppression; introduces new viral drug targets |

| Host-Directed Antivirals | TMPRSS2, pyrimidine biosynthesis (e.g., DHODH), TRiC, Hsp90, JAK-STAT pathways, IFN-λ system | Camostat, nafamostat, brequinar, baricitinib, teriflunomide, interferon lambda (IFN-λ) | Reduced viral resistance potential; broad-spectrum activity; may pose host toxicity risks |

| AI and Computational Drug Discovery | Structure-based virtual screening, machine learning prediction, synergy modeling, allosteric pockets on RdRp (nsp12) | COVID Moonshot, flavonoid derivatives (e.g., myricetin), ML-based compound ranking | Accelerates drug discovery; identifies novel scaffolds; enables variant-specific antiviral tailoring |

| Gene silencing and RNA-Targeting Therapies | siRNA targeting conserved genome regions (e.g., RdRp); CRISPR-Cas13-mediated cleavage of viral RNA | siRNA-nanoparticle delivery systems and Cas13-based antiviral platforms | Programable and rapidly deployable antivirals; adaptable to emerging viruses |

| Pan-Coronavirus and Broad-Spectrum Antivirals | Conserved viral domains (nsp12-nsp7/nsp8 interface, nsp13 helicase); shared host dependency factors (e.g., DHODH, IFN) | Ribavirin, NHC, DHODH inhibitors, innate immune modulators | Enables pandemic preparedness; broad viral coverage; strategic stockpiling for future zoonotic outbreaks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).