1. Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a life-threatening condition associated with high mortality rates and the incidence of severe disability among survivors [

1]. Early medical intervention (including treating the ruptured aneurysm) is recommended to prevent rebleeding, control intracranial pressure, and to prevent delayed complications [

2,

3]. However, patients with acute SAH are not necessarily admitted to medical institutions immediately due to an underestimation of the SAH symptoms by the patients or via initial misdiagnosis at the first medical contact [

4,

5].

Previous studies have described the impact of delayed admission on SAH-related complications and functional outcomes primarily based on single-center experience, with mixed results depending on definition of delayed admission and treatment strategy of the ruptured aneurysms [

5,

6,

7]. In particular, when the patient is admitted during the period prone to delayed neurological deterioration due to vasospasm, the choice of an optimal treatment modality and its timing are still debatable to date.

In this article, we investigated the impact of delayed admission at Day 4 or later (Day 0 = SAH onset) on the incidence of symptomatic cerebral vasospasm and functional outcomes from a multicenter, prefecture-wide SAH registry in Japan. The timing of aneurysmal treatment and the choice of treatment modality were also analyzed and discussed in the delayed admission patient group.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted based on the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Study in Epidemiology) criteria. The study protocol was approved by the Kochi Medical School Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Kochi, Japan) (#108921), and consent was waived because there were no unique patient identifiers. The institutional ethics committees of all participating hospitals also approved the study protocol.

2.1. Patient Selection, Clinical Evaluation, and Study Design

The Department of Health Policy in Kochi Prefectural Office, Japan, has registered all acute stroke patients who were admitted to 29 hospitals in Kochi prefecture since 2011 (Kochi Acute Stroke Survey of Onset: KATSUO registry). The characteristics of the stroke care system in Kochi Prefecture and KATSUO registry database have been described previously [

8,

9]. Briefly, selection bias is minimized because all the prefecture-wide stroke patients are registered, and because Kochi Prefecture is a ‘closed’ county regarding emergency patient transfer, where only about 1% of the patients are transferred into or out of Kochi Prefecture [

9,

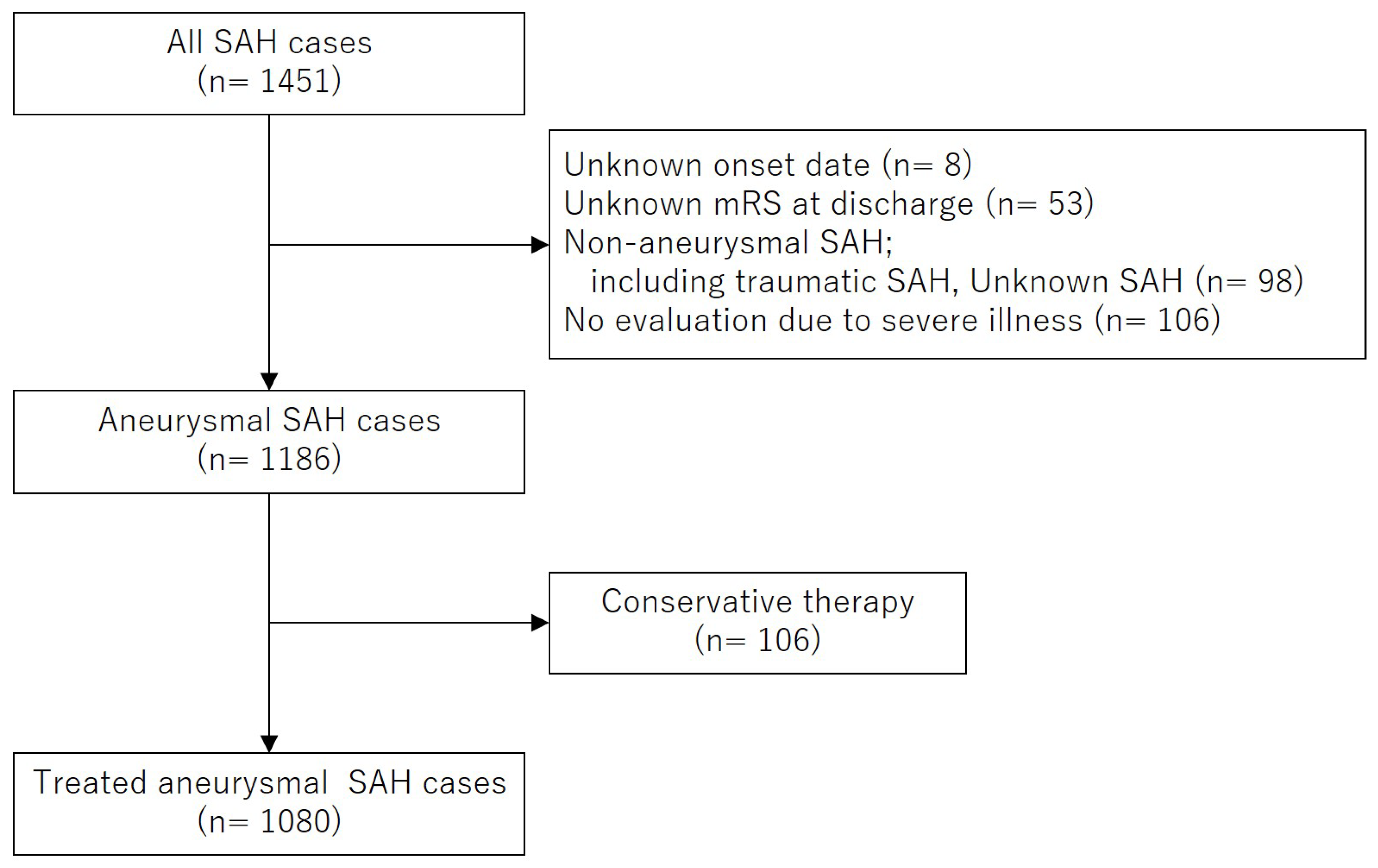

10]. Data were provided for Kochi Medical School Hospital after patient anonymization. Between May 2011 and December 2022, 1,451 patients with SAH were registered in the KATSUO registry from seven primary and comprehensive stroke centers in Kochi Prefecture. Among them, eight patients with an unknown onset date, 98 with non-aneurysmal SAH, and 53 with missing modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at discharge, were excluded. Among the remaining 1,186 patients with aneurysmal SAH, 106 who did not undergo surgical or endovascular treatment were excluded from the study population. Consequently, 1,080 patients who underwent treatment for the ruptured aneurysms were included in the final analysis.

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the patient selection process.

This retrospective cohort study investigated the association between delayed hospital admission at Day 4 or later (Day 0 = SAH onset) and functional outcomes, symptomatic vasospasm, procedure-related complications, and chronic hydrocephalus in patients with SAH due to ruptured intracranial aneurysms. The threshold of Day 4 was determined on the basis that delayed cerebral ischemia due to vasospasm typically occurs after Day 3, and obliteration of the aneurysm within 72 hours of onset has been reported to improve functional outcomes [

11,

12]. The date of SAH onset was deemed to be the time of occurrence of a headache that persisted, aggravated, recurred after initial improvement, and was either followed by a new neurological deficit or not. Symptomatic vasospasm was defined as a neurological worsening characterized by a decrease in the Glasgow Coma Scale score of two points or greater or an increase in the motor score of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale of two point or greater, which lasted for more than 8 hours, after excluding other causes by laboratory and radiological examinations [

13]. Poor functional outcomes were defined as an increasing mRS score ≥ 3 at the time of discharge from hospital for patients with a pre-admission mRS score of 0 or 1. Procedure-related complications were defined as neurological deterioration associated with cortical or subcortical cerebral infarction, postoperative hematoma formation, and increasing subarachnoid clot volume [

14]. Chronic hydrocephalus was defined as symptomatic hydrocephalus requiring cerebrospinal fluid shunting. Age, sex, dates of SAH onset and hospital admission, and premorbid history (hypertension, smoking status), were retrieved from the KATSUO registry. In addition, Fisher computed tomography (CT) group, initial neurological status according to the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) grade, treatment modality (direct surgery or endovascular therapy), the maximum diameter of the aneurysm, aneurysmal location (internal carotid artery [ICA], anterior cerebral artery [ACA], middle cerebral artery [MCA], and posterior circulation [PCQ]), symptomatic vasospasm, procedure-related complications, chronic hydrocephalus, and mRS score at the time of discharge were collected for the patient cohort from the participating hospitals. During the study period, the timing of therapeutic intervention, choice of treatment modality, and postoperative care were determined at the discretion of the participating hospitals and attending physicians.

Baseline characteristics of the delayed admission group (Day 4 ∼) were compared with those of the early admission group (∼ Day 3). The association between delayed hospital admission and functional outcomes, symptomatic vasospasm, procedure-related complications, and chronic hydrocephalus, was analyzed using univariate, multivariable, and subgroup analyses. Subsequently, the date of intervention and choice of treatment modality for the ruptured aneurysms in the delayed admission group were recorded in detail, along with the presence of angiographic vasospasm on admission, which was defined as ≥ 50% stenosis in the major cerebral arteries via magnetic resonance imaging, CT, or cerebral angiography.

2.2. Date Analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR: 25th-75th percentile) as appropriate, and non-normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were evaluated using the Chi-square test. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the risk factors for symptomatic cerebral vasospasm and poor functional outcomes (mRS 3-6). The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were also determined via logistic regression analyses. Multiple imputation was used to handle missing values. The number of multiple imputations was set at 10, and 50 iterations were performed. This created 10 complete datasets in which the missing values were imputed with different plausible values. Predictive mean matching was specified as the imputation method. Logistic regression analysis was performed on each imputed dataset, and the results were pooled to calculate the OR and 95% CI. SPSS version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R Statistical Software (v4.2.0; R Core Team 2022) were used for all statistical analyses. Probability (p) values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and all p-values were two-sided.

3. Results

Patient baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. Delayed admission at Day 4 or later were observed in 69 (6.4%) cases. All the patients experienced a headache with or without vomiting at the onset. Among them, 63 patients visited the hospital for persisting headache, two from drowsiness, one from general malaise, and one from gait disturbance. One patient exhibiting aphasia and the other displaying right leg weakness were considered to have symptomatic vasospasm upon admission.

Table 2 shows the results of a univariate analysis of factors for delayed admission. The location of the aneurysm was significantly different between the patient groups, where more ICA aneurysms and less MCA and PCQ aneurysms were observed in the delayed admission group. The neurological status upon admission, as represented by the WFNS grade, was significantly better in the delayed admission group with more WFNS grades I-II (89.8% vs. 56.2%) and less WFNS grades IV-V (4.3% vs. 40.0%, respectively) cases compared with those in the early admission group. A patient with Fisher group 3, representing the presence of a thick subarachnoid clot in the head CT, was less likely to be observed in the delayed admission compared with the early admission group (44.9% vs. 83.8%, respectively).

Univariate analyses were used to assess an association between delayed patient admission and either treatment modalities or various outcome measures and the results are shown in

Table 3. The incidence of endovascular therapy use, and the frequency of procedure-related complications were comparable with those of the early admission group. Symptomatic vasospasm was significantly more likely to be observed in the delayed versus the early admission group (20.3% vs. 11.9%, respectively; p = 0.042, Chi-square test), while poor functional outcomes representing mRS scores 3-6 at the time of discharge were less likely to be observed in the delayed compared with the early admission group (28.6% vs. 53.2%, respectively; p < 0.001, Chi-square test). In the analysis for poor functional outcomes, 97 patients with premorbid mRS ≥ 2 were excluded so that the remaining 983 patients could be evaluated. An association between delayed admission and symptomatic vasospasm was further evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses. After adjustment for other covariates such as WFNS grade and endovascular therapy use, delayed admission was observed to be an independent risk factor for symptomatic vasospasm (OR = 2.51, 95% CI [1.26-5.00], p = 0.009), (

Table 4). Motivated by the significant differences in WFNS grade between the early and delayed admission groups, we undertook subgroup analysis and multivariable logistic regression analyses to investigate the association between delayed admission and poor functional outcomes. The subgroup analysis of 627 patients with WFNS grade I-III revealed 17/60 (28.3%) and 207/567 (36.5%) patients with poor functional outcomes in the early and delayed admission groups, respectively.

The association between delayed admission and poor functional outcomes was not revealed in a statistically significant fashion by multivariable analysis (OR = 0.53, 95% CI [0.28-1.02], p = 0.059) (

Table 5). The choice of treatment modality in the delayed admission group and its association with the timing of aneurysmal treatment, angiographical vasospasm upon admission, procedure-related complications, functional outcomes, and location of the aneurysm, were further analyzed (

Table 6). Comparing the endovascular therapy with the direct surgery group, the interval from admission to treatment was significantly shorter (0 [0-1] vs. 1[1-8] days, median [IQR], respectively; p = 0.007, Mann-Whitney U test) and the ratio of treatment within 4 days after admission was significantly higher (91.9% vs. 68.8%, respectively; p = 0.028, Mann-Whitney U test). Procedure-related complications (composite of ischemic and hemorrhagic) occurred in 7/37 (18.9%) and 6/32 (18.8%) patients of the endovascular therapy and direct surgery groups, respectively. The incidence of poor functional outcomes was also comparable between these two groups.

Patients with angiographic vasospasm upon admission were treated by endovascular therapy (eight cases), all of whom were treated before the angiographic vasospasm resolved. Direct surgery was performed in six patients with angiographic vasospasm upon admission before (three cases) and after (three cases) resolution of the vasospasm. More PCQ aneurysms and less MCA aneurysms were treated by endovascular therapy than direct surgery in the delayed admission group, and this statistical trend was similar to that observed in the early admission group.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association of delayed admission at Day 4 or later with complications and outcomes of aneurysmal SAH from a multicenter, prefecture-wide registry in Japan. Delayed admission was found to be an independent risk factor for symptomatic vasospasm. Although more patients with better functional outcomes were observed in the delayed admission group, this positive impact of delayed admission did not achieve statistical significance after adjustment for potential confounders. We also described interactions among choice of treatment modality, timing of treatment, and procedure-related complications of the ruptured aneurysms in the delayed admission group of patients.

Aneurysmal SAH remains a life-threatening condition, associated with high mortality and morbidity [

1]. Immediate occlusion of the culprit aneurysm and subsequent neurocritical care are recommended to prevent secondary brain injury caused by rebleeding and vasospasm [

15]. However, hospital admission of patients with SAH may sometimes be delayed for several reasons including misdiagnosis at the initial contact to the medical service as well as delay in seeking of medical help by the patients themselves who do not consider their symptoms serious [

5]. Previous studies have investigated the prognosis of SAH with delayed admission, resulting in controversy presumably due to a lack of consensus for the definition of delayed admission [

5,

6,

7,

16,

17]. When a study exclusively focuses on patients who were misdiagnosed by clinicians, significantly worse outcomes were reported in the group of patients with delayed admission [

6,

16]. However, when a study also included a delay in seeking medical help on the part of the patient, which is more prevalent than misdiagnosis in the current era with more accurate and widespread neurovascular imaging, better functional outcomes were observed in patients with delayed admission [

5,

7]. This discrepancy in functional outcome results may have been caused by a better initial neurological status (e.g., WFNS grade I-II) for patients reporting a delayed visit to the hospital. A study including patients with a delayed hospital visit does not capture patients presenting with severe neurological deficit upon admission, who cannot describe their first ictus, resulting in a selection bias. Also, the initial symptoms of those patients who sought medical attention at the onset and were misdiagnosed should be more severe than those of patients who took a wait-and-see approach and chose to stay at home. Although patients who survived for several days after the first ictus without rebleeding [

18,

19] generally exhibit better functional outcomes that are associated with a better neurological status upon admission, we have been wondering whether the outcomes of patients with delayed admission are different from those of the early admission group after adjustment for confounding factors such as initial WFNS grade. Also, we wanted to determine trends in choice of treatment modality and treatment timing of ruptured aneurysms in patients with delayed admission from a multicenter registry that is less affected by treatment policy of the individual institution.

In this study, delayed hospital admission was found to be an independent risk factor for symptomatic cerebral vasospasm. There are several possible reasons for this finding. First, a subarachnoid clot is not effectively cleaned out early after the onset in the delayed admission group. The remaining subarachnoid clot contains vasoconstrictive factors including products of the vascular endothelium and erythrocyte degradation [

20,

21]. An early washout of the subarachnoid clot by surgical removal, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, and spontaneous mechanisms, has been reported to decrease the risk of vasospasm [

22,

23,

24]. Second, intracranial pressure elevation due to cerebral edema and hydrocephalus at the acute SAH facilitates the vasospasm to symptomatize, which have been mitigated by decompressive craniectomy and external ventricular drainage in the early admission group [

25]. Furthermore, early anti-vasospastic treatment is available particularly after the aneurysmal repair [

26]. Notably, a delayed hospital admission has also been shown to be significantly associated with symptomatic vasospasm in a previous study by Goertz et al., which has a different study design that employs a definition of delayed admission as ≥ 48 hours and involves a more predominant use of endovascular therapy [

7], which may explain the robustness of the findings in our study.

In this study, we did not find significantly different functional outcomes between the early and delayed admission groups after adjustment for confounding factors by multivariable analysis, suggesting that the seemingly more favorable outcomes were attributable to a better neurological status upon admission in the delayed admission group. Although the functional outcomes of the delayed admission group were generally favorable, a treatment strategy should be optimized for even better outcomes. Several controversies exist in the treatment modality and treatment timing for ruptured aneurysms of the patients in the delayed admission group. More frequent use of less invasive endovascular therapy may be advantageous when dealing with brain tissues and vessels showing signs of vasospasm, while an over-use of endovascular therapy may increase procedure-related complications of the aneurysm that is amenable to direct surgery [

7,

27]. Additionally, although an immediate obliteration of the ruptured aneurysm offers maximal protection from rebleeding and provides anti-vasospastic treatment, delaying aneurysmal obliteration for > 10 days after SAH onset may minimize the risk of procedure-related complications by avoiding insult during the unstable hemodynamic conditions prevalent in the vasospastic period [

17]. In our present study, attending physicians in multiple participating hospitals, on average, did not increase the use of endovascular therapy, but preferred it when immediately treating the aneurysm in the delayed admission group. A comparable incidence rate of procedure-related complications between early endovascular therapy performed during the vasospastic period and late direct surgery performed during the post-vasospastic period may suggest the validity of endovascular therapy as an immediate intervention for patients who were admitted in the vasospastic period. We believe that the treatment strategy for ruptured aneurysms in the delayed admission group should be individualized according to multiple factors including patient characteristics, timing of hospital visit, anatomical conditions of the aneurysm, and the presence of an angiographic vasospasm. For example, the clinical management responses to a patient admitted on Day 4 with no signs of vasospasm and the one who is admitted on Day 9 with a severe angiographic vasospasm may be varied. Also, even though an elective direct surgery may have been planned after the vasospasm subsides, a drastic change in the shape of the aneurysm revealed by neuroimaging may urge the attending physician to treat the aneurysm immediately. However, a potential contribution of non-individual approaches by institutional treatment policies, including the application of immediate endovascular therapy to as many aneurysms as possible with the aggressive use of adjunctive devices (e.g., stents) [

7] or a universally applied delayed intervention strategy in the post-vasospastic period given the lowered daily rebleeding rate of the ruptured aneurysm at Day 4 or later [

18,

19], may also be worth evaluating.

This study has several limitations. First, our findings should be interpreted with caution because of the observational and retrospective study design. Second, a direct comparison between early and delayed admission groups is intrinsically challenging even with multivariable or subgroup analysis. For example, a comparison of clot volume at presentation may be less relevant, where the patients with a Fisher group 2 subarachnoid clot in the delayed admission group may have had a Fisher group 3 SAH at onset before washout. Third, because of the small number of the patient, an association of functional outcomes with patients baseline characteristics, treatment modality, treatment timing, presence of angiographic or symptomatic vasospasm, anatomical condition of the aneurysm, and their interactions, was only descriptive and thus less conclusive in the delayed admission group. Further investigations, using a nationwide registry with more patients, for example, is warranted to identify individualized optimal treatment strategies in this heterogeneous patient subgroup.

5. Conclusions

In this study, using a prefecture-wide multicenter registry in Japan, a delayed admission at Day 4 or later was observed to be significantly associated with an increased incidence of symptomatic vasospasm, while functional outcomes remained comparable to those of the early admission group. The use of endovascular therapy did not increase in the delayed admission group, but it was used significantly earlier than in the direct surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Hosokawa. and H.F.; Methodology, Y.Hosokawa. and H.F.; Formal analysis, Y.Hosokawa., H.F., and Y. Hyohdoh.; Investigation, Y.Hosokawa., T.K., K.S., Y.Y., M.Y., Y.Hoashi., A.M., K.B., N.M., F.H., Y.K., Y.U., N.F.,; Data curation, Y.Hosokawa., T.K., K.S., Y.Y., M.Y., Y.Hoashi., A.M., K.B., N.M., F.H., Y.K., Y.U., N.F.,; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.Hosokawa., H.F., and Y. Hyohdoh.; Writing—review and editing, All authors.; Supervision, T.U.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Kochi Medical School Hospital (Ethical Approval Number 108921, approved on February 10, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because there were no unique patient identifiers.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available from the authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAH |

Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| mRS |

modified Rankin Scale |

| WFNS |

World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies |

| ICA |

Internal Cerebral Artery |

| ACA |

Anterior Cerebral Artery |

| MCA |

Middle Cerebral Artery |

| PCQ |

Posterior Circulation |

| KATSUO |

Kochi Acute Stroke Survey of Onset |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Study in Epidemiology |

References

- Huhtakangas, J.; Lehto, H.; Seppä, K.; Kivisaari, R.; Niemelä, M.; Hernesniemi, J.; Lehecka, M. Long-term excess mortality after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: patients with multiple aneurysms at risk. Stroke 2015, 46, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, J.V. Acute endovascular treatment by coil embolisation of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2001, 83, 253–256. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, S.; Ogasawara, K.; Kuroda, S.; Itabashi, R.; Toyoda, K.; Itoh, Y.; Iguchi, Y.; Shiokawa, Y.; Takagi, Y.; Ohtsuki, T.; et al. Japan Stroke Society Guideline 2021 for the Treatment of Stroke. Int J Stroke 2022, 17, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neil-Dwyer, G.; Lang, D. ‘Brain attack’-aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: death due to delayed diagnosis. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1997, 31, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagawa, T. Delayed diagnosis of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in patients: a community-based study. J Neurosurg 2011, 115, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.G.; Claassen, J.; Kreiter, K.T.; Bates, J.E.; Ostapkovich, N.D.; Connolly, E.S.; Mayer, S.A. Initial misdiagnosis and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. JAMA 2004, 291, 866–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, L.; Pflaeging, M.; Hamisch, C.; Kabbasch, C.; Pennig, L.; von Spreckelsen, N.; Laukamp, K.; Timmer, M.; Goldbrunner, R.; Brinker, G.; et al. Delayed hospital admission of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: clinical presentation, treatment strategies, and outcome. J Neurosurg 2021, 134, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H.; Hyohdoh, Y.; Ninomiya, H.; Ueba, Y.; Ohta, T.; Kawanishi, Y.; Kadota, T.; Hamada, F.; Fukui, N.; Nonaka, M.; et al. Impact of areal socioeconomic status on prehospital delay of acute ischaemic stroke: retrospective cohort study from a prefecture-wide survey in Japan. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e075612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H.; Ninomiya, H.; Ueba, Y.; Ohta, T.; Kaneko, T.; Kadota, T.; Hamada, F.; Fukui, N.; Nonaka, M.; Watari, Y.; et al. Impact of temperature decline from the previous day as a trigger of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage: case-crossover study of prefectural stroke database. J Neurosurg 2020, 133, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Department of Health Policy in Kochi Prefectural Office. Available online: https://www.pref.kochi.lg.jp/soshiki/130401/ (accessed on 20 September 2019.).

- Lawton, M.T.; Vates, G.E. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, E.C., Jr.; Kassell, N.F.; Torner, J.C. The international cooperative study on the timing of aneurysm surgery. The North American experience. Stroke 1992, 23, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, R.L.; Rosengart, A.; Huo, D.; Karrison, T. Factors associated with the development of vasospasm after planned surgical treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2003, 99, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H.; Hayashi, K.; Yoshino, K.; Koyama, T.; Lo, B.; Kurosaki, Y.; Yamagata, S. Impact of aneurysm projection on intraoperative complications during surgical clipping of ruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2016, 78, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gijn, J.; Rinkel, G.J. Subarachnoid haemorrhage: diagnosis, causes and management. Brain 2001, 124, 249–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, P.L.; Awad, I.A.; Todor, R.; Harbaugh, K.; Varnavas, G.; Lansen, T.A.; Dickey, P.; Harbaugh, R.; Hopkins, L.N. Misdiagnosis of symptomatic cerebral aneurysm. Prevalence and correlation with outcome at four institutions. Stroke 1996, 27, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilstra, E. H.; Rinkel, G. J.; Algra, A.; van Gijn, J. Rebleeding, secondary ischemia, and timing of operation in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology 2000, 55, 1656–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkuma, H.; Tsurutani, H.; Suzuki, S. Incidence and significance of early aneurysmal rebleeding before neurosurgical or neurological management. Stroke 2001, 32, 1176–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassell, N.F.; Torner, J.C. Aneurysmal rebleeding: a preliminary report from the Cooperative Aneurysm Study. Neurosurgery 1983, 13, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Masaoka, H.; Hirata, Y.; Marumo, F.; Isotani, E.; Hirakawa, K. The role of endothelin-1 in the origin of cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1992, 77, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberg, M.R.; Okada, T.; Bark, D.H. The role of hemoglobin in arterial narrowing after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of Neurosurgery 1990, 72, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Mielke, D.; Barner, C.; Malinova, V.; Kerz, T.; Wostrack, M.; Czorlich, P.; Salih, F.; Engel, D.C.; Ehlert, A.; et al. Effectiveness of lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drain among patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2023, 80, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, N.; Matsukawa, H.; Kamiyama, H.; Tsuboi, T.; Noda, K.; Hashimoto, A.; Miyazaki, T.; Kinoshita, Y.; Saito, N.; Tokuda, S.; et al. Preventing cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage with aggressive cisternal clot removal and nicardipine. World Neurosurg 2017, 107, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, C.; Amidei, C.; Tolentino, J.; Jahromi, B.S.; Macdonald, R.L. Clot volume and clearance rate as independent predictors of vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2004, 101, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Manoel, A.L.; Jaja, B.N.; Germans, M.R.; Yan, H.; Qian, W.; Kouzmina, E.; Marotta, T.R.; Turkel-Parrella, D.; Schweizer, T.A.; Macdonald, R.L.; et al. The VASOGRADE: A Simple Grading Scale for Prediction of Delayed Cerebral Ischemia After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Stroke 2015, 46, 1826–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, K.; Moore, J.M.; Griessenauer, C.J.; Xu, J.; Teng, I.; Dmytriw, A.A.; Chiu, A.H.; Ogilvy, C.S.; Thomas, A. Ultra-early angiographic vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2017, 102, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaney, K.K.; Todd, M.M.; Torner, J.C.; IHAST Investigators. Variation of patient characteristics, management, and outcome with timing of surgery for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2011, 114, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).