Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare and aggressive tumor that most commonly affects the pleural lining of the lungs (both the parietal and visceral surfaces), and less frequently the peritoneum, pericardium and tunica vaginalis of the testis [

1]. This disease is closely associated with asbestos exposure and most cases, due to a latency period exceeding 30 years and the challenges of early diagnosis, are not detected until they reach an advanced stage [

2]. Since the main risk factor for MPM is asbestos exposure, it is crucial to collect a detailed patient’s history to determine if and under what circumstances exposure occurred [

3]. Studies on pleural mesothelioma have shown that, in Italy, the percentage of tumors not related to occupational asbestos exposure is less than 20% [

4]. The peak incidence of MPM in Italy is expected between 2020 and 2030, considering that the industrial use of asbestos peaked in the mid-1980s and ceased in 1992 with the enactment of law 257/92 [

5]. The highest incidence of MPM is observed in the north of the country, in particular the province of Pavia where, between 1932 and 1993, the second largest asbestos factory in Italy was operational, producing components for the construction industry [

6].

In most patients, MPM is not associated with oncogenic mutations. However, genetic susceptibility exists due to germline mutations in the BAP1 oncogene. BAP1 is essential for DNA repair, and mutations in this gene are linked to a condition known as BAP1-TPDS (BAP1 Tumor Predisposition Syndrome). Patients with this syndrome are more likely to develop pleural mesothelioma, along with other cancers such as renal cell carcinoma and cutaneous and uveal melanoma [

7]. Despite the predisposition to multiple cancers, patients with BAP1-TPDS generally have a better prognosis compared to other MPM patients, potentially due to differences in tumor biology and response to treatment [

8].

The therapeutic approach of malignant pleural mesothelioma has long been defined as trimodal, involving an integrated combination of chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy. This triple approach aims to leverage the strengths of each modality. Multidisciplinary teams must account for interindividual variability, as even patients with similar morphological features may experience differing disease progression and manifestations. It is essential that the treatment of MPM is managed by highly specialized centers, equipped with dedicated multidisciplinary teams, ensuring comprehensive and personalized care [

9,

10]. The presence of a complex and progressively worsening symptomatology, especially in advanced stages, necessitates a well-structured approach to the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway. Consequently, collaboration between specialists responsible for specific treatments and personnel in pain management and palliative care becomes essential from the moment of diagnosis [

11]. This multidisciplinary approach aligns with the "Simultaneous Care" model, ensuring a smooth and gradual transition while maintaining continuity of care. Surgery is a key component in the treatment of MPM, particularly for patients with localized disease (stages T1 to T3 and N0 or N1) and the epithelioid subtype, which has the most favorable prognosis [

12]. However, due to the non-specific nature of early symptoms, diagnosis is often confirmed in more advanced stages. In these cases, surgery typically assumes a palliative role, such as draining pleural effusions to improve lung expansion and prevent recurrence [

13]. In the treatment of MPM, radiotherapy can be used for palliative purposes, particularly in patients whose symptoms are not adequately controlled by systemic or symptomatic therapy, or in case of disease oligoprogression or curative treatment of localized pleural disease [

14,

15].

Chemotherapy (CT) for malignant pleural mesothelioma can be either neoadjuvant or adjuvant. There are no significant differences between these two approaches in terms of their effect on patient survival, although the neoadjuvant strategy is generally preferred [

16]. One of the negative aspects of chemotherapy is the thinning of blood vessels, which leads to an increased predisposition to bleeding [

17]. In patients for whom surgery is not a viable option, CT is the best treatment choice and should be initiated once the histological diagnosis is confirmed, not at the onset of symptoms [

18]. This treatment involves the use of platinum derivatives, such as cisplatin or carboplatin, combined with a third-generation antifolate, either pemetrexed or raltitrexed. Currently carboplatin is preferred over cisplatin due to its reduced toxicity [

19,

20]. In cases of disease progression or poor drug tolerance, a second-line chemotherapy regimen may be considered, such as gemcitabine or vinorelbine, or participation in ongoing clinical trials, if the inclusion criteria are met [

21,

22]. Currently, the biological drug ramucirumab is also available in combination with gemcitabine in second-line treatment, through nominal drug use requests [

23].

In non-epithelioid histology, which is associated with a poorer prognosis, standard treatments with platinum derivatives and pemetrexed have not proven effective in ensuring long-term survival improvement [

24]. Consequently, studies have been conducted to identify viable alternatives for this patient group. Among these, CheckMate 743 has emerged as one of the most promising. This study evaluates the combination of Nivolumab, a human antibody targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and Ipilimumab, a human antibody targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4). The combination of Nivolumab and Ipilimumab has been established as the new standard of care for patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), irrespective of histology, and for those who are treatment-naïve [

25].

Despite the possibility of using various approaches and drugs, malignant pleural mesothelioma cannot be completely eradicated, and this inevitably leads to disease recurrence [

26]. In patients on follow-up who show progression on CT scan, rechallenging with platinum-pemetrexed regimen or with pemetrexed alone may be proposed after that other second- and third-line drugs have been exhausted, or as an alternative to these therapies. However, this additional therapeutic option cannot be offered in all cases. Several factors must be considered before recommending this approach: the overall health status of the patient, the extent of the response to the initial platinum-pemetrexed regimen, the time interval between the end of the treatment and the subsequent disease progression and any recorded treatment-related side effects.

Our study aims to evaluate the benefit, in terms of survival, of chemotherapy rechallenge treatment versus supportive therapies alone in patients with MPM who don’t have further available chemotherapy options and to identify potential epidemiological and clinical predictive factors for response to chemotherapy rechallenge strategy.

Materials and methods

We collected data from patients diagnosed with MPM since November 2018 and treated in our single Institution. The collected informations include patients' medical history, tumor histology, staging, and the therapeutic approaches undertaken. Among the therapies considered, in addition to surgery and radiotherapy, various chemotherapy regimens, both first- and second-line, were included, as well as the choice, in advanced cases, between the option of chemotherapy rechallenge with platinum-pemetrexed and the approach of palliative and supportive care. The patients' sample was then reduced based on the inclusion criteria. Cases where the diagnosis of MPM was not confirmed and cases where rechallenge therapy was performed at other institutions with no available data regarding outcomes, side effects, and survival were excluded from the study. The data collected come from patients' medical histories, day hospital admissions, outpatient visits, and discharge letters from services received in the asbestos-related diseases department at IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo Hospital. Special attention was given to sensitive data for each patient with informed consent signed according to standard hospital procedures. Epidemiological aspects such as sex, age at diagnosis, smoking habits, and asbestos exposure were investigated. Clinically, factors such as histology, tumor staging, and therapeutic approach were considered, particularly focusing on the side effects from first-line platinum-pemetrexed therapy and from chemotherapy rechallenge.

Continuous variables were described using the mean and the standard deviation or the median and 25th–75th percentiles for skewed distributions, while categorical data were reported as counts and percentages. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were assessed with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the effect of rechallenge chemotherapy and palliative care on survival. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals.

A two-tailed p-value < 0.005 was considered statistically significant. The data analysis was performed using Stata software (release 18, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

From November 2018 to March 2024, 183 patients were considered in our analysis, 20 of whom were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Table 1 presents the general descriptive clinical characteristics of the entire study population.

Of these, 41 patients with advanced stage of disease and previously treated, were evaluated for chemotherapy rechallenge with platinum-pemetrexed regimen or were candidate only to palliative and supportive care. 17 patients (41.5%) were candidate for chemotherapy rechallenge, 24 patients (58.5%) received only best supportive care.

Table 2 describes these two different populations.

Comparing these populations, in the overall population 69.3% of patients are male, 70.8% whom undergoing palliative care. This is notably different from the population treated with chemotherapy rechallenge, where only 41.1% of the cases (7 out of 17) are male, indicating a female predominance. The male-to-female ratio in the first two categories is close to 2.3, a value not far from that reported in the seventh Italian National Work Injuries Istitute report (M/F 2.6) [

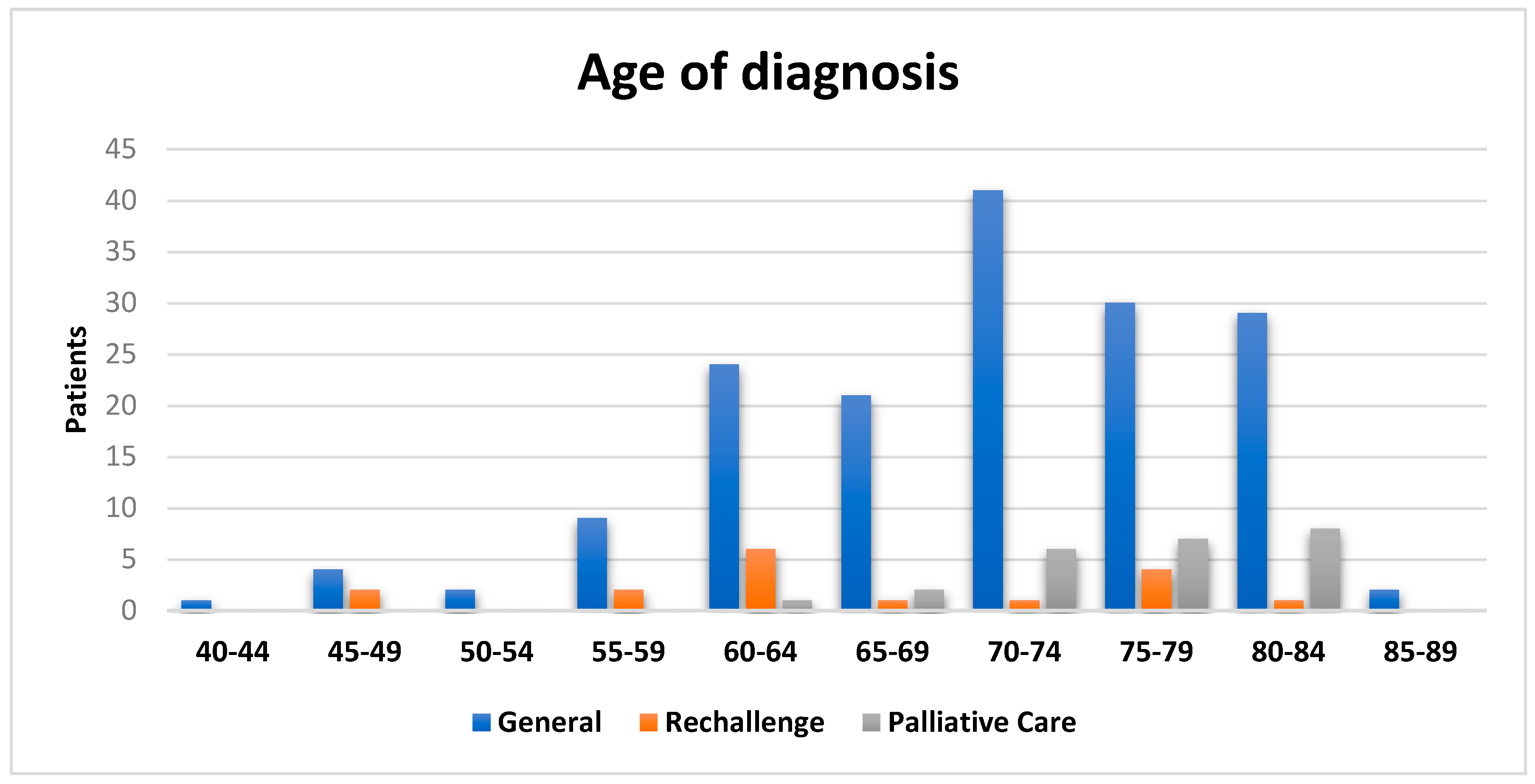

27]. In the overall population, the male predominance is associated with occupational exposure to asbestos in industrial plants, where most of the workforce was male. The average age at diagnosis is 70.6 for all patients (

Figure 1), in line with the most recent Italian National Mesothelioma Register report [

27]. This value drops to 65.3 for the rechallenge cases and rises to 75.7 for those who did not undergo rechallenge treatment. Analyzing the data regarding asbestos exposure highlights its significant role in the onset of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Indeed, only 37.4% of patients report no known exposure to asbestos, with the remaining cases split evenly between occupational and environmental exposure. Of these, 47 patients are residents in an area known for its facilities and structures built with this material, including schools. These individuals were exposed both directly and indirectly (as family members of workers in asbestos-related industrial plants). Between 1932 and 1993, in the town of Broni was located the second-largest asbestos factory in Italy [

28]. Nine out of the 17 patients treated with platinum-pemetrexed had a positive history of asbestos exposure (3 occupational and 6 environmental), a proportion that rises to 17 out of 24 in the untreated group (10 occupational and 7 environmental). Of the total 163 patients, about half (51.5%) have no history of smoking, a percentage that drops to 35.3% for the rechallenge group, which is not much different from the 45.8% in the palliative care group. Exposure to smoking has been shown to be synergistic with asbestos in increasing the risk and prevalence of malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), acting biologically by causing an inflammatory state and direct DNA damage [

29].

When evaluating the histology of the overall population, it is reported that the epithelioid histotype predominates over the others, representing 80% of the cases, which is consistent with the data reported in literature (70-85%) [

30]. The incidence of the sarcomatoid subgroup is 6.7%, the same as the biphasic subgroup. Only 9 patients did not have a definitive histological confirmation. Histological diversity is completely lost in patients who underwent rechallenge, as only 2 are classified as NOS (Not Otherwise Specified) and the remaining 15 are epithelioid. In contrast, the population initiated to pain management, although it maintains a predominance of epithelioid histotype shows more variety, with 4 biphasic cases and one case of desmoplastic mesothelioma. Neither group present patients with the sarcomatoid histotype.

70% of the patients are diagnosed with early stage of disease (IA-IB-II) and are therefore eligible for surgical therapy and a multimodal approach. The proportions remain similar in the rechallenge population, with 11 out of 17 patients at early stages and only one patient at stage IV. In contrast, the representation of advanced stages is different in the untreated patients, with 14 out of 24 at advanced stages, including 6 at stage IV.

We conducted an analysis to identify and select the most significant predictive and prognostic variables. In comparing the two populations, rechallenge and palliative care, we focused on the clinical parameter of overall survival (OS). The temporal reference point for the analysis was the visit in which the decision was made to initiate platinum-pemetrexed rechallenge therapy or to start the palliative and supportive care pathway. Table 3 shows the distribution of patients who are alive and deceased, as well as the expected proportions based on survival outcomes. The rechallenge group demonstrates a higher proportion of patients alive compared to the palliative care group, reflecting the potential benefit of rechallenge therapy in improving overall survival.

The observation period ranges from approximately 0.36 to 41 months, with an average of about 8.88 months and a median of approximately 4.44 months.

Analyzing the distribution of failures (patient death) relative to the treatment, it was observed that 21 out of 24 patients who were not re-challenged with platinum-pemetrexed regimen died. Among the re-challenged patients, 5 are still alive, while 12 have died. Therefore, 80.5% of the subjects experienced the failure event. Initially, the survival probability is high, but it decreases rapidly in the first few months. After about 6 months, the survival probability drops below 50%. After about 12 months, the survival probability falls below 35%. After about 24 months, the survival probability drops below 15%.

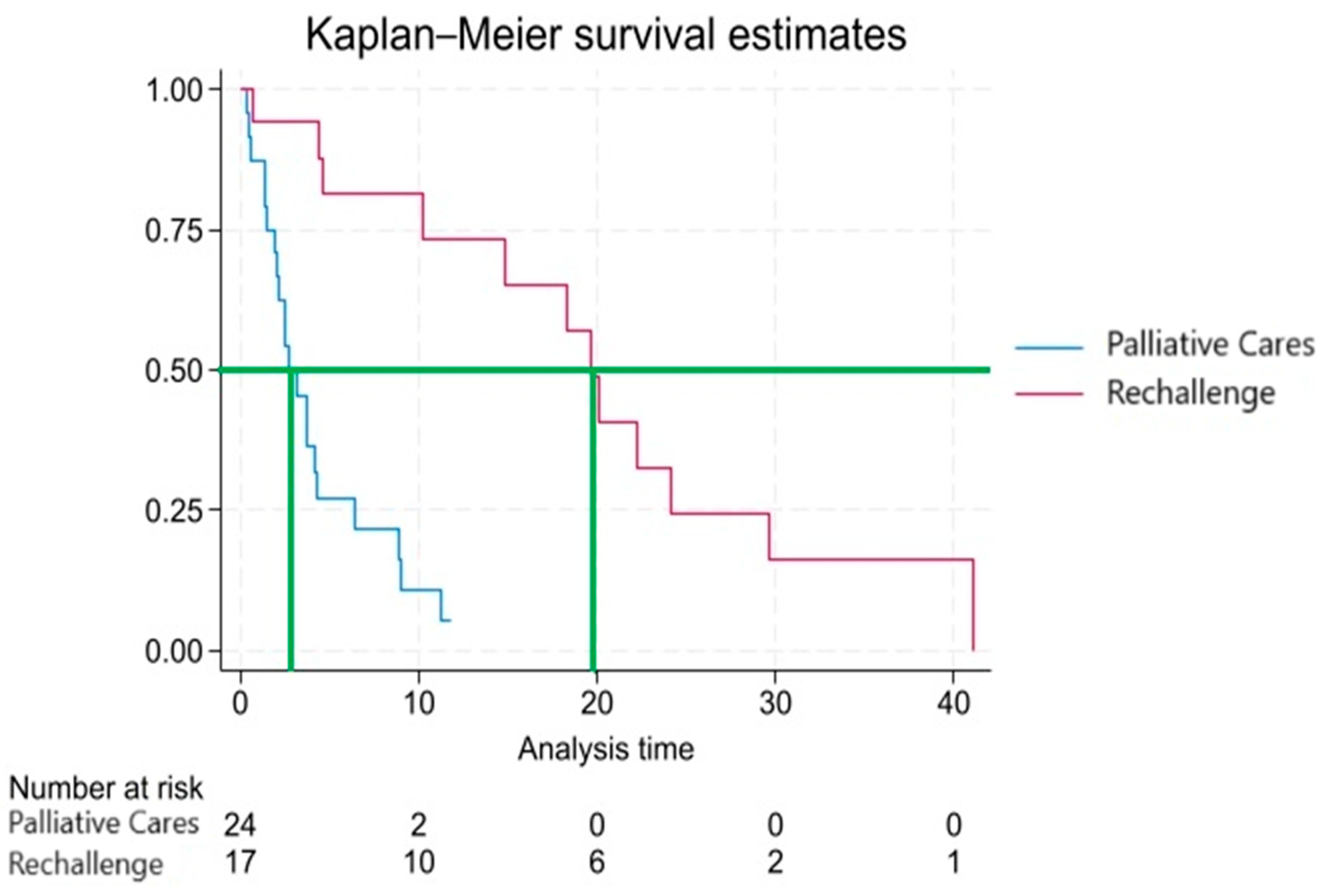

The Kaplan-Meier survival function depicted in

Figure 2 reveals a rapid decline in the first few months, indicating a high mortality rate during that period. The confidence intervals become wider at later time points, reflecting increased uncertainty in the estimates when fewer subjects remain at risk. This trend could be influenced by various factors including the severity of the disease, the effectiveness of treatments, and other clinical and demographic variables.

At several observed time points, patients in the rechallenge group appear to exhibit better survival outcomes than those in the palliative care group, as evidenced by the differences in survival proportions.

Cox regression analysis further supports this observation, identifying rechallenge as a significant predictor of survival. The coefficient analysis reveals a p-value of less than 0.001 (-3.780 [CI 95%: -3.22, -1.01], p<0.001), indicating a statistically significant association between rechallenge and improved survival. When expressed as a hazard ratio (HR 0.12, [CI 95%: 0.04-0.36]), the p-value remains below 0.001, suggesting that patients who did not undergo rechallenge are at a significantly higher risk of failure compared to those who received the treatment. To validate the assumptions of the Cox regression model, a Schoenfeld residuals test was conducted, yielding a negative result, confirming the absence of temporal dependencies between hazards and validating the procedure. The p-value is very small, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis of equal survival functions between the two rechallenge groups. This suggests that the survival functions in the two groups are significantly different, meaning that the survival between patients treated with rechallenge is significantly different from those who did not receive the treatment.

Given the small number of patients and the associated low reliability, multivariable models were not performed. Due to collinearity, palliative care and rechallenge cannot be included in the same model. Furthermore, age at diagnosis did not have a significant impact on survival (p > 0.005), suggesting that the age at which the diagnosis is made may not be a critical factor in determining patient prognosis.

Discussion

In this study, 41 patients with advanced-stage malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) were analyzed from a cohort of 163 MPM patients. The primary goal was to assess the actual survival benefit of platinum-pemetrexed rechallenge treatment in patients who had exhausted second-line chemotherapy options or as a replacement for these, compared to palliative care. Additionally, the study aimed to identify possible predictive factors for response to chemotherapy. When comparing median survival times, a significant difference was observed between the two study groups, with patients treated with platinum-pemetrexed rechallenge reaching approximately 20 months of median survival, while those receiving palliative care only had a median survival of 3 months. However, this finding should be contextualized, as there are decision-making criteria considered by clinicians that may act as confounders. The patient's age at the time of the therapeutic decision is a factor that influences the treatment course, along with performance status, which may lead the physician to not consider rechallenge in older patients. This is supported by the difference in mean age at diagnosis between the two populations, with 65.3 years in the rechallenge group and 75.7 years in the Palliative Care group.

The most important limitations of our study are its retrospective design and the small number of patients analyzed, based only on a single-center patient population. Multivariable models were tested to look for possible associations between epidemiological-clinical factors and survival outcomes for the two groups. However, due to the small sample size available in the study, the results were not deemed reliable.

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), despite being a rare neoplasm, continues to be the subject of ongoing studies and updates, encompassing every aspect of the diagnostic and therapeutic pathways, as well as the underlying etiological and predictive factors. National and international guidelines encourage the participation of patients in ongoing clinical trials whenever eligible, due to the current lack of demonstrated efficacy for second-line alternatives in patients previously treated with platinum and pemetrexed.

This study was able to highlight a potentially significant relationship between the survival of patients and the use of the rechallenge regimen with platinum-pemetrexed as therapy for advanced-stage mesothelioma. However, considering the study's limitations, future research should expand the sample size to better identify factors that may serve as predictors of a positive response to treatment. Prospective studies would allow for the analysis of factors such as side effects and quality of life associated with rechallenge, correlating these with epidemiological and tumor characteristics. Furthermore, looking ahead, the goal is to delve deeper into molecular, genetic, and epigenetic aspects, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the patient and the tumor. This would facilitate a more personalized treatment approach, based on the specific characteristics of each patient, in line with precision medicine. Tailoring treatments based on clinical and molecular features is becoming a cornerstone of modern oncology, but many gaps remain, gaps that only continued research can fill.

References

- Lettieri S, Bortolotto C, Agustoni F, et al. The Evolving Landscape of the Molecular Epidemiology of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J Clin Med 2021; 10 (5): 1034. [CrossRef]

- Hajj GNM, Cavarson CH, Pinto CAL, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: an update. J Bras Pneumol 2021; 47 (6): e20210129. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi C, Bianchi T. Malignant mesothelioma: global incidence and relationship with asbestos. Ind Health. giugno 2007;45(3):379–87. [CrossRef]

- Marinaccio A, Binazzi A, Bonafede M, Di Marzio D, Scarselli A. Epidemiology of malignant mesothelioma in Italy: surveillance systems, territorial clusters and occupations involved. J Thorac Dis. gennaio 2018;10(Suppl 2):S221–7. [CrossRef]

- Marsili D, Angelini A, Bruno C, et al. Asbestos Ban in Italy: A Major Milestone, Not the Final Cut. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14 (11): 1379. [CrossRef]

- Visonà SD, Villani S, Manzoni F, et al. Impact of asbestos on public health: a retrospective study on a series of subjects with occupational and non-occupational exposure to asbestos during the activity of Fibronit plant (Broni, Italy). J Public Health Res 2018; 7 (3): 1519. [CrossRef]

- Hiltbrunner S, Fleischmann Z, Sokol ES, Zoche M, Felley-Bosco E, Curioni-Fontecedro A. Genomic landscape of pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma tumours. Br J Cancer. 23 novembre 2022;127(11):1997–2005. [CrossRef]

- Betti M, Casalone E, Ferrante D, Aspesi A, Morleo G, Biasi A, et al. Germline mutations in DNA repair genes predispose asbestos-exposed patients to malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Lett. 1 ottobre 2017;405:38–45. [CrossRef]

- Scherpereel A, Opitz I, Berghmans T et al. ERS/ESTS/EACTS/ESTRO guidelines for the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur Respir J 2020; 55 (6): 1900953. [CrossRef]

- Saracino L, Bortolotto C, Tomaselli S, et al. Integrating data from multidisciplinary Management of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: a cohort study. BMC Cancer 2021; 21 (1): 762. [CrossRef]

- Harrison M, Gardiner C, Taylor B, Ejegi-Memeh S, Darlison L. Understanding the palliative care needs and experiences of people with mesothelioma and their family carers: An integrative systematic review. Palliat Med. giugno 2021;35(6):1039–51. [CrossRef]

- van Zandwijk N, Clarke C, Henderson D, Musk AW, Fong K, Nowak A, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Dis. dicembre 2013;5(6):E254-307. [CrossRef]

- Moro J, Sobrero S, Cartia CF, et al. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Diagnostics 2022; 12 (12): 3009. [CrossRef]

- Gomez DR, Rimner A, Simone CB, et al. The Use of Radiation Therapy for the Treatment of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Expert Opinion from the National Cancer Institute Thoracic Malignancy Steering Committee, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation. J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14 (7): 1172–83. [CrossRef]

- Luna J, Bobo A, Cabrera-Rodriguez JJ, Pagola M, Martín-Martín M, Ruiz MÁG, et al. GOECP/SEOR clinical guidelines on radiotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. World J Clin Oncol. 24 agosto 2021;12(8):581–608. [CrossRef]

- Scherpereel A, Astoul P, Baas P, Berghmans T, Clayson H, de Vuyst P, et al. Guidelines of the European Respiratory Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons for the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. marzo 2010;35(3):479–95. [CrossRef]

- Tsao AS, Pass HI, Rimner A, Mansfield AS. New Era for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Updates on Therapeutic Options. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40 (6): 681–92. [CrossRef]

- Hughes A, Calvert P, Azzabi A, Plummer R, Johnson R, Rusthoven J, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of pemetrexed and carboplatin in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 15 agosto 2002;20(16):3533–44. [CrossRef]

- Deiana C, Fabbri F, Tavolari S, et al. Improvements in Systemic Therapies for Advanced Malignant Mesothelioma. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24 (13): 10415. [CrossRef]

- Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 5 ottobre 2014;740:364–78. [CrossRef]

- Petrini I, Lucchesi M, Puppo G, Chella A. Medical treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma relapses. J Thorac Dis 2018; 10 (Suppl 2): S333–41. [CrossRef]

- Biersack B. Interplay of non-coding RNAs and approved antimetabolites such as gemcitabine and pemetrexed in mesothelioma. Non-Coding RNA Res. dicembre 2018;3(4):213–25. [CrossRef]

- Pinto C, Zucali PA, Pagano M, et al. Gemcitabine with or without ramucirumab as second-line treatment for malignant pleural mesothelioma (RAMES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021 Oct; 22 (10): 1438-47. [CrossRef]

- Clopton B, Long W, Santos M, Asarian A, Genato R, Xiao P. Sarcomatoid mesothelioma: unusual findings and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. novembre 2022;2022(11):rjac512. [CrossRef]

- Baas P, Scherpereel A, Nowak AK, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2021; 397 (10272): 375–86. [CrossRef]

- Carbone M, Adusumilli PS, Alexander HR, Baas P, Bardelli F, Bononi A, et al. Mesothelioma: Scientific Clues for Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. settembre 2019;69(5):402–29. [CrossRef]

- Italian National Mesothelioma Register report. https://www.inail.it/cs/internet/comunicazione/pubblicazioni/catalogo-generale/pubbl-il-registro-nazionale-mesoteliomi-settimo-rapporto.html.

- Consonni D, De Matteis S, Dallari B, et al. Impact of an asbestos cement factory on mesothelioma incidence in a community in Italy. Environ Res 2020; 183: 108968. [CrossRef]

- Klebe S, Leigh J, Henderson DW, Nurminen M. Asbestos, Smoking and Lung Cancer: An Update. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 17 (1): 258. [CrossRef]

- Italian Medical Oncology Association National Guidelines for malignant pleural mesothelioma. https://www.aiom.it/linee-guida-aiom-2021-mesotelioma-pleurico.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).