1. Introduction

The diversity of goat and sheep breeds is fundamental to the sustainability of agricultural production, especially in regions with adverse ecological conditions. The history of animal husbandry practices among local communities reflects a rich cultural heritage and an intrinsic relationship between tradition and the environment. In this context, ethnozootechnics emerges as an approach that integrates traditional and academic knowledge, valuing the wisdom accumulated over generations and its application in management and selection practices [26].

This appreciation of local knowledge is a manifestation of what is known as ethnoscience, which emerged in the United States in the 20th century. This new approach transcends the view of cultures as mere sets of artifacts and behaviors, and begins to consider them as knowledge systems [3]. Ethnozootechnics, in turn, was made official with the creation of the Société d'Ethnozootechnie in France [24]. This discipline represents the intersection between local and academic knowledge, especially in the context of zootechnical practices. It values the connection between traditional knowledge accumulated over generations and academic knowledge related to animal breeding and management, which is essential for sustainable animal production.

However, the loss of local knowledge represents a significant threat to the conservation of agrobiodiversity, especially in traditional communities [5]. This loss of knowledge, often the result of the modernization and industrialization of agriculture, compromises the genetic diversity of breeds and the ability of communities to adapt to environmental changes. In addition, industrial land use systems also contribute to the erosion of biodiversity and local cultural elements, resulting in the global trend of biodiversity loss [11].

Traditional knowledge is also important in breeding programs, especially in the selection of breeding animals based on local criteria. This is particularly relevant in small-scale, family-based breeding systems, whose interests differ from large production systems [11]. However, despite its importance, studies adopting this perspective in Brazil are still recent and punctual, reflecting the need for greater research into the application and valorization of local knowledge in management practices [3,4].

In this context, the aim of this work was to evaluate the history, diversity index and selection criteria of goats and sheep in four territories in the semi-arid region of Paraíba, using the ethno-zoological approach.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research was carried out in four territories that are part of the Semi-Arid Articulation of Paraíba (ASA-PB). ASA-PB forms a network of organizations that operate throughout the Semi-Arid Region, with the aim of defending the rights of the inhabitants and communities of this area. The organizations that make up the ASA are structured in assemblies and networks in the ten states that cover this Brazilian biome (MG, BA, SE, AL, PE, PB, RN, CE, PI and MA). One of the initiatives undertaken by this network is the improvement of family-based animal husbandry systems with locally adapted breeds in Paraíba. The study involved 80 families from four groups (CASACO, FOLIA, BORBOREMA and COLETIVO) in eight municipalities in Paraíba (Soledade, São Vicente, Esperança, Queimadas, Campina Grande, Boqueirão, Aroeiras and Caraúbas).

The territory of CASACO (Association of Leaders, Organizations, Farmers and Family Farmers of Cariri Paraibano) was established in 2008 by Father Francisco Ponciano da Silva, then serving as priest of the Parish of Nossa Senhora do Desterro - Boqueirão-PB. Its efforts are focused on the transition of family farmers to agroecology, impacting nine municipalities in the Cariri Paraibano Territory: Alcantil, Barra de São Miguel, Cabaceiras, Caraúbas, Caturité, Congo, Boqueirão, Riacho de Santo Antônio and São Domingos do Cariri.

The territory known as “Polo Borborema” is a Centre of Trade Union and Family Farming Organizations of Borborema, established in July 1996. Embracing agro-ecological principles, it is currently dedicated to innovative initiatives to support family farming in the municipalities of Alagoa Nova, Algodão de Jandaíra, Arara, Areial, Casserengue, Esperança, Lagoa Seca, Matinhas, Montadas, Queimadas, Remígio, São Sebastião de Lagoa de Roça and Solânea. Folia, or the Agreste Leadership Forum, involves women farmers and young people from the municipalities of Aroeiras, Fagundes, Gado Bravo, Ingá, Itatuba, Itabaiana, Natuba, Mogeiro and Umbuzeiro.

Finally, the Collective serves as a significant platform for critical analysis, formulation, proposal and negotiation of public policies aimed at family farming in Cariri, Curimataú and Seridó. It has also been instrumental in the management and planning of community and regional development initiatives, with a focus on strengthening agroecological practices in family farming.

This region, in particular, covers an area of 22,671 km² and is located at geographical coordinates 8° 13' 37“ S and 37° 12' 46” W, with an elevation of 525 meters and a distance of 126.5 km from the capital of Paraíba.

2.2. Data Collection

The study used an ethno-zootechnical approach, integrating the knowledge and experience of breeders at all stages of the project (3). To this end, a semi-structured questionnaire was used, supported by the focus group technique, which involved technicians, researchers and breeders.

2.3. Historical Survey

The history of the formation of the herds was based on information from six breeders, representatives of the aforementioned territories. These individuals, aged over 50, have dedicated more than two decades of their lives to raising animals of locally adapted breeds/ecotypes and, given their experience, have been recognized as guardians of biodiversity and local traditions. In addition, they have cultural information and a great deal of experience in handling and managing their livestock.

2.4. Current and Past Diversity in the Territories

In order to understand and quantify the current and past diversity of locally adapted breeds/ecotypes and species in the territories, two workshops were held with breeders from the four territories involved.

Workshop 1 - Participants were divided into separate groups and interviewed separately to ensure that the answers of one group did not influence those of the others. Each group discussed the conservation situation of the diversity of locally adapted goat and sheep breeds/ecotypes, answering open-ended questions about the presence or absence of these animals in the landscape of each territory. The Recall technique [13] was used to explore the collective memory of the communities, complementing the information obtained. The answers were documented in a structured spreadsheet (diagrams 1 and 2) for later analysis.

Workshop 02 - In the second workshop, photographic support was used to present the interviewees with images of the ecotypes and locally adapted breeds of goats and sheep in the region studied. A discussion group was formed to discuss the most important characteristics considered by farmers when choosing goats and sheep for breeding. The Recall technique [13] was then applied again to improve and complement the data collected. In order to assess the participants' level of knowledge about locally adapted breeds and ecotypes, a questionnaire was carried out with three levels of response: (1) know; (2) heard of; and (3) don't know. The answers were recorded in a spreadsheet based on the schemes 3 and 4 provided, assuming the existence of breeds and ecotypes.

2.5. Definition of Selection Criteria

Workshop 3 - This workshop used the ranking matrix methodology [12]. One male and one female sire were presented to the breeders, who evaluated and scored the characteristics of interest in order of importance. The answers were recorded on appropriate spreadsheets for later analysis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The interviews were recorded, later transcribed and then subjected to content analysis in order to highlight the most important and relevant aspects of the reports. The interview data was examined using frequency and multiple correspondence analyses to verify the association between current and past knowledge of animal diversity in the four territories studied.

The citation frequencies of breeds, ecotypes/species in the present and in the past were submitted to correspondence analysis (ACM) with the support of the SAS program, using the following mathematical model in summary:

Where:

S: The original data matrix containing the citation frequencies of the breeds in the present and past.

U: The unit matrix containing the eigenvectors of the SST matrix. The columns of U are called left singular vectors.

D: This is a diagonal matrix containing the singular values of S. The singular values are the square root of the eigenvalues of the ST S (or SST) matrix.

VT: This is the transpose of the unit matrix V, which contains the eigenvectors of the STS matrix. The columns of V are called the right-hand singular vectors.

The factor coordinates are obtained using the following formula:

, Where:

: These are the factorial coordinates of the rows and columns, respectively.

: The element of the U matrix at position i α, it represents the value of the i-th eigenvector in the direction of the α-th singular value.

It is the α-th squared singular value, which is an eigenvalue of the STS or SS matrices.

It is the sum of the elements of row i in the contingency matrix S. It represents the total frequency of the row.

: It is the sum of the elements of column j in the contingency matrix S. It represents the total frequency of column j.

This analysis was used to assess the existence of a significant association between the observed frequencies and the expected frequencies in the data distribution.

The ACM helps to understand the associations between categories in contingency tables. Its use is proposed when you have many categorical variables and want to identify patterns underlying the real data. ACM consists of transforming the original data into a space of reduced dimensions, where the relationships between categories are more easily visualized. The ACM estimates the inertia, which measures the total variation in the data and seeks to maximize the variation explained by each dimension. Finally, a graph is generated with the first two dimensions (inertia), and the behavior of the data is analyzed based on these dimensions, which are the most explanatory.

2.7. Diversity Index

The Shannon diversity index (H') was used to assess the diversity of locally adapted breeds/ecotypes of goats and sheep in the territories, which was calculated for the number of animals present in the past and present on the farms. Shannon's index will be higher the greater the number of breeds and the uniformity of their abundance. If the index value is equal to 0, only one species is present in the territory. The H' index is calculated as follows:

Where:

H= índice de diversidade de Shannon;

proportion of individuals of the i-th species in an entire community;

Σ = symbol;

log = usually the natural logarithm, but the base of the logarithm is arbitrary (base 10 and 2 logarithms are also used);

n = individuals of a certain type/species;

N = total number of individuals in a community.

The minimum value that Shannon's diversity index can take on is 0. This number would indicate the absence of diversity, as only one species/race/ecotype would be found in that habitat. The range of values for the Shannon diversity index is generally 1,5 to 3,5.

For a better interpretation of the diversity index, the uniformity was calculated:

Where k is the number of locally adapted breeds/ecotypes cited by the interviewees. Uniformity gives a value between 0 and 1, and the closer it is to 1, the greater the diversity.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. History of Breeding

According to the oldest farmers interviewed (guardians), the most common farming system in the region since ancient times has been the diversified system, which involves the rearing of small ruminants for the most part, but also includes other animal species such as cattle, poultry and pigs. This system has numerous advantages, including economic sustainability, proper use of pastures and better labor management [31].

All the interviewees expressed a strong emotional connection with their livestock. The animals are only sold at specific times to meet the family's needs. In this study, the sheep farmers were asked about the breeds/ecotypes that were part of their emotional memory. They highlighted the lanzuda sheep as a significant component in the ancestral narrative of their lineage, information corroborated by Finan [14], who highlighted the great importance attributed by farmers to animal welfare, emphasizing the emotional bond shared between the family and the livestock.

This emotional connection with animals is not exclusive to small ruminant farmers. According to Schuppli [38], individuals involved in dairy farming also develop strong emotional connections with cattle, highlighting the importance of these animals beyond financial gain. In a study with stingless bees, it was identified that beekeepers are also in favor of conservation for emotional and aesthetic reasons [7,8]. Thus, the appreciation of the animal in traditional communities transcends mere economic production, reflecting a deep recognition of the role that these living beings play in the lives and cultures of the communities.

Based on the farmers' reports, there has been a dynamic change in the breeds and ecotypes present in the region. Ecotypes such as the Lanzuda and Cariri, of the sheep species, as well as the Canindé, Azul, Vermelha, Nambi, and mocha goat breeds/ecotypes with short hair and black backs, which were once quite evident, are now rare in the region. The ethnozootechnical approach made it possible to verify that breeders often use specific names for the ecotypes, which are the same ecotypes known by other names, which does not necessarily represent greater racial diversity.

The Nambi ecotype, for example, is known in most territories as Landi. This knowledge has a direct impact on the calculation of the diversity index, which can be overestimated or underestimated if it is not possible to verify when it is the same genotype with different names. On the other hand, the term “red goat”, used by the breeders, probably corresponds to the Parda Sertaneja, while the term “Tartaruga” suggests characteristics of crossbreeds of the Nubian breed with local ecotypes. It was also found that the term “Lombo Preto” is another name given to the Moxotó breed.

Another important observation made by breeders is that, according to them, “in the past, animals were healthier, got sick less and had less difficulty giving birth.” This is certainly due to the loss of genetic variability, with significant impacts on animal health and reproduction over time. When an animal population shows a reduction in genetic variability, it results in a lower capacity to face environmental and biological challenges [20].

Research carried out by Salles [37], Cardoso [6] and Pakpahan [34], with the goat species, reveals that the decrease in genetic variability has serious consequences on the health and reproductive performance of the animals. In addition, Stachowicz [41], in a study with sheep, emphasize the importance of monitoring and controlling inbreeding levels to maintain genetic variability, a necessary measure for the conservation of breeds/ecotypes.

3.2. Local Knowledge and Diversity of Genotypes

The farmers reported that the Azul, Canindé and Repartida goat genotypes existed in the Casaco and Coletivo territories more than 15 years ago. However, only the Azul still populates the region, albeit with few flocks. The Graúna, Marota and Parda Sertaneja ecotypes were also common in the region, but are no longer seen in the local landscape.

Of all the groups, the Moxotó goat breed still inhabits Folia territory. As these breeds and ecotypes disappear from the region, new groups appear and populate the landscape. Therefore, in addition to the groups that are still frequent in the region, breeders have pointed out new genetic groups, such as the Chuíte and the Olho de Prata, completely unknown to academia until now. Many of these new groups may just be different names for existing groups.

Among the sheep genotypes present in the ancient landscape of the territories are the Cara Curta, Lanzuda and Santa Inês. These same genotypes are seen in the current landscape, with the exception of the Pé-duro ecotype. The breeders highlighted the Lanzuda ecotype as being very resistant. Many genotypes are no longer found in the region, and several studies highlight a strong association between this disappearance and the extinction of local knowledge, promoted by the modernization of livestock farming and the introduction of exotic material [22].

The growing importance of agro-industry and corporate power has restricted the viability of many small-scale systems as they become increasingly exposed to competition from the open market. The organization of agricultural and livestock systems according to the principles of an industrial factory, scientifically organized for mass production, has massively displaced and devalued traditional knowledge systems and the elements that make up these systems [15, 43, 17].

The introduction of imported genetic material, driven by globalization, has contributed to the erosion of local knowledge and biological diversity, as research in other regions of the world has reported [10,39]. The loss of biodiversity associated with the loss of local knowledge has had negative consequences for conservation. Therefore, efforts must be made to safeguard biodiversity, traditional peoples and their knowledge systems [36].

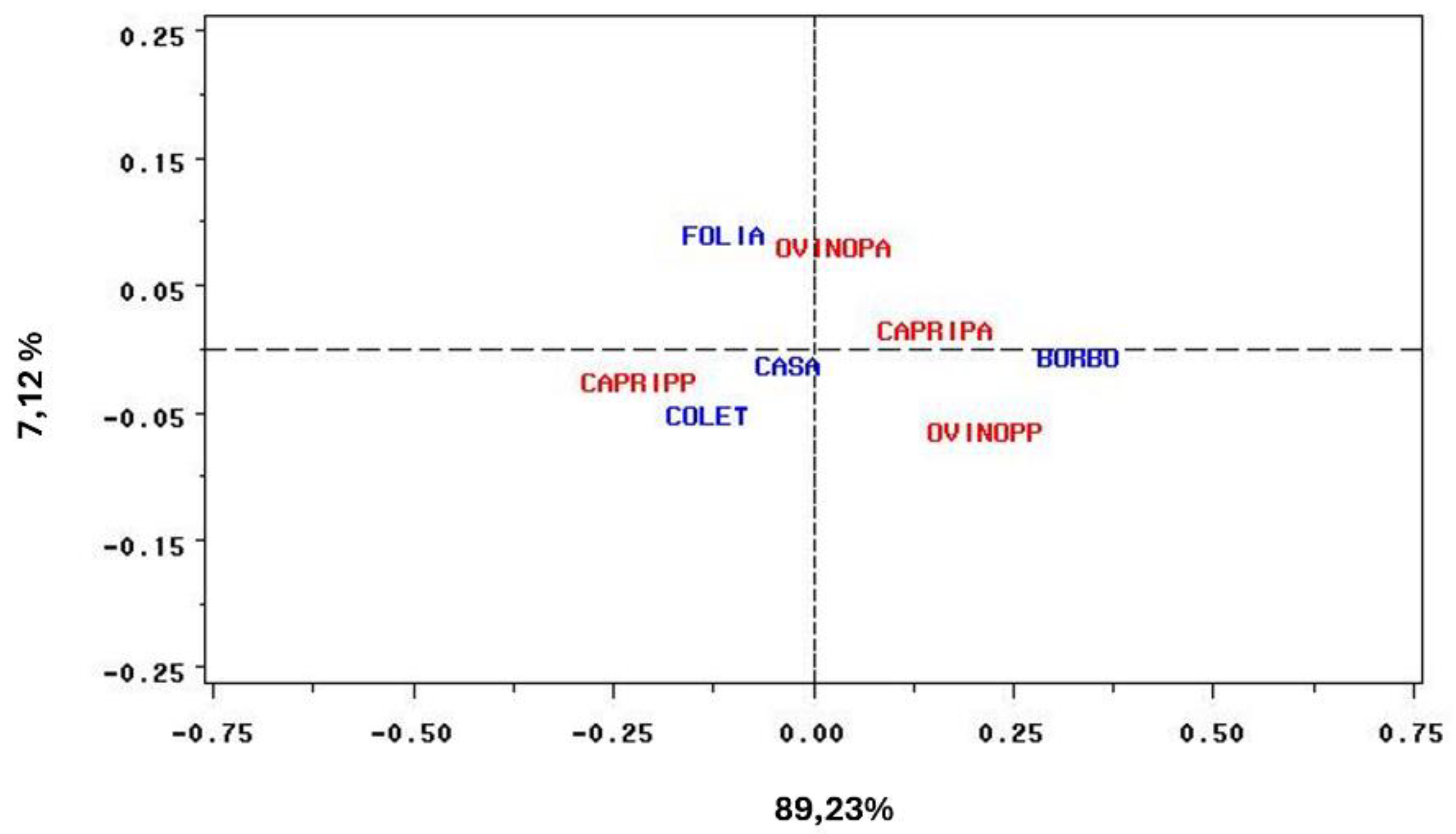

Figure 1 shows the distribution of goats and sheep in the current and past landscape, according to the multiple correspondence analysis. In the Past Landscape, the coletivo territory had the greatest diversity of goats, followed by the Casaco territory. However, in the current landscape, this panorama has changed, indicating a loss of goat diversity. Only in the Casaco territory was there a greater diversity of breeds/ecotypes. The breeders showed concern about the exchange of breeding stock.

This study found that only 30.0% of the people interviewed knew of any locally-adapted goat breed/ecotype. The majority of those interviewed (70.0%) had only heard of these animals or were unaware of them. The interviewees cited Marota, Moxotó and Graúna as the least known genotypes. On the other hand, they showed greater knowledge of exotic breeds, such as Anglo Nubiana and Boer, which populate the region and have been widely used to crossbreed and replace locally adapted breeds/genotypes. Among the goats, the Azul ecotype, the Canindé breed and the Nambi ecotype are the best known, perhaps due to social and development projects using these genotypes in the study region.

These findings reveal a concerning scenario regarding the preservation of traditional knowledge and the associated local biodiversity. The erosion of local knowledge is closely correlated with the decline of genetic resources in the territories where they have historically developed. This knowledge, built upon accumulated experience and orally transmitted across generations, constitutes an intangible heritage that is essential for the management, conservation, and sustainable use of animal biodiversity, particularly in contexts of traditional and subsistence agriculture. The loss of this knowledge weakens not only local production systems but also the socio-ecological resilience of the communities involved. Aswani [5], report that, due to the interconnection between cultural and biological diversity, the loss of local and Indigenous knowledge is likely to seriously threaten the effective conservation of biodiversity, particularly in community-based local conservation efforts. Local knowledge is being transformed globally, and in many cases, lost. In many parts of the world, rural and Indigenous communities are facing profound cultural, economic, and environmental changes, which contribute to the weakening of their local knowledge base.

With regard to the knowledge and conservation of local breeds, these trends towards the use of exotic breeds reflect policies to encourage the modernization of farming, which often prioritize productivity over the conservation of local genetic diversity. Rege and Ibson [35] point out that although public policies favor the introduction of exotic breeds motivated by the search for desirable characteristics, such as higher milk or meat productivity, this can unintentionally result in the erosion of traditional knowledge and the replacement of locally adapted breeds that are better suited to the environmental conditions of the region.

Ginja [16], in studies of genetic markers with Ibero-American native goat breeds, point out that the progressive abandonment of agriculture in marginal areas and uncontrolled crossbreeding with exotic breeds represent the greatest threat to existing breeds/ecotypes, leading to a decline in genetic diversity. In Africa, studies by Ouchene-Khelifi [33] and Chokoe [9] also highlight the loss of genetic diversity promoted by uncontrolled crossbreeding with exotic breeds.

The lack of intra-racial gene flow in the territories is another factor contributing to the disappearance of certain breeds in this region, promoted by geographical isolation. Mdladla [29], using the ethnozootechnical approach, observed that genetic isolation over time had a significant influence on the genetic diversity of goat populations.

Regarding sheep, a greater diversity of breeds and ecotypes was observed in the ancient landscape, especially in the Borborema territory. In the current landscape, there has been a change in this scenario. The Folia territory showed greater diversity of sheep, indicating a change in the distribution of these breeds across the territories over time.

Of the interviewees, only 38,22% were familiar with the locally adapted sheep breeds or ecotypes, and at least 13,73% had heard of them. However, 50,00% of the interviewees are unaware of any locally adapted breed.

The most well-known sheep, according to the interviewees, are Morada Nova and Somali (74.50%), followed by Santa Inês sheep (49.01%). The vast majority of respondents are unaware of the Barriga Negra (88.23%), Rabo Largo (74.50%), and Cariri (66.70%) ecotypes. This is certainly due to the absence of herds of these groups in the region, which is associated with the low effective number and the high degree of threat they are subjected to, as indicated by some studies.

These results are also related to the introduction of exotic breeds, reinforcing the fact that the interviewees did not have the opportunity to know and interact with these genotypes in the local landscape. The literature is extensive on the strong association between the extinction of local knowledge and the loss of genetic material. This knowledge is essential for the implementation of effective conservation and management strategies for these populations, aiming to preserve not only genetic diversity but also cultural and environmental richness, as these elements are intrinsically related.

Traditional breeding systems play a fundamental role in the conservation of local genetic diversity. By valuing these systems, it is possible to stimulate the recognition of the genetic potential of locally adapted breeds, essential material for sustainable breeding programs [4]. These genotypes have adapted to local environments and possess characteristics suitable for the specific conditions of their habitats. The maintenance of this genetic material contributes to the global resilience and sustainability of livestock production systems [19] . Furthermore, it is essential to empower and involve the breeders, holders of local knowledge, in the decision-making processes [27]. This will help ensure that their knowledge and experience are valued and incorporated into conservation and improvement programs.

3.3. Diversity Index

The Shannon diversity index (H’) obtained for goats in the prehistoric landscape was 1,3. In the current landscape, this index was significantly lower (0,87), which suggests a significant loss of breed/ecotype diversity over time in the studied territories, negatively impacting genetic variability. A similar study, conducted by Kuznetsov [23] with taurine breeds, observed a Shannon diversity index of 1,69, suggesting a moderate level of genetic diversity in these populations.

For sheep breeds/ecotypes, an H’ value of 0,7 was observed in the past landscape, while in the current landscape this value was slightly lower. (0,66). These values are considered low compared to those observed for goats; however, they remained constant over time. A study with locally adapted Iranian bovine breeds, using genetic markers, reported an average of 0,9 for the Shannon Index, indicating a reasonable genetic diversity [2].

The locally adapted breeds and ecotypes in breeding systems are essential for the maintenance of agrobiodiversity. Maintaining this local diversity in animal production favors the integrity of these systems. This local genetic heritage enhances the dynamics of animal production systems, enabling access to genetic adaptive capacities that allow the animal to become established in the region, while the traditional knowledge of the human-animal relationship accumulated over the years continues to be passed on to future generations. More than maintaining productive practices, genetic diversity is essential for food security as it provides resources for the settlement and well-being of family farmers, promoting the availability of food for the future [40].

These results provide important information about the genetic variation among different breeds and ecotypes of goats and sheep in the studied territories, highlighting the importance of proper conservation and management of these populations to ensure their long-term viability.

3.4. Criteria for Animal Selection

The interviewees highlighted the importance of choosing animals with uniform, harmonious, and aesthetically pleasing conformation, which exhibit characteristics such as libido, vitality, and normal testicles. Furthermore, the preference for animals from healthy and defect-free parents was emphasized. Among the characteristics considered essential for breeders, testicle size and body uniformity were mentioned as attributes of greatest interest. The interviewees' statements reflect the appreciation of specific characteristics in the selection of breeders, which can directly influence the quality and performance of future generations.

The interviewed breeders emphasized that cryptorchid, small, and feminine-looking animals should be disqualified and discarded. Based on the breeders' reports, it was possible to identify specific criteria for the selection of goat and sheep breeders. (

Table 1 and 2).

Several studies suggest that the choices of goat breeders are influenced by a combination of personal perceptions, market information, breeding experience, and animal characteristics, although there are regional variations in preferences [1, 45, 42].

The guardian breeders cited reproductive characteristics, the physical conformation of the individual, health, health history, parent production, and behavioral issues as being of great importance in the selection of an animal for reproduction. It became clear from the interviewees' statements that the greatest emphasis is placed on the reproductive, adaptive, and health characteristics of the animals. Less importance was given to production characteristics (meat or milk).

In the Brazilian semi-arid region, Arandas [4] investigated the selection criteria adopted by breeders of the Morada Nova sheep breed, highlighting those related to the breed standard, notably the appearance and coat color of the animals as the most important. Mbuku [28], in Africa, considered that their integrated systems of knowledge about the studied herds were adequate to identify that the breeding objectives are based on the appearance of the animals. In turn, Nandolo [32] observed criteria based on meat production in one community and non-productive criteria in other communities in Malawi. In these situations, distinct genetic improvement programs could produce better responses.

Liljestrand [25] found that, among Maasai herders, the reason for keeping animals is based on multiple objectives. Adaptive characteristics, such as disease and drought resistance, and productive traits, such as increased growth and carcass weight, were well classified by these breeders. Furthermore, the sheep holds social and traditional value in Maasai culture. Thus, goats and sheep contribute tangible and intangible benefits to family farming in arid and semi-arid regions, as reported by Kaumbata [21] and Guerrero-Gatica [18].

The most recent work by Tyasi [44], studying goats in Africa, found that the most preferred characteristics by breeders for females in the surveyed villages were the ability to have twin births, maternal ability, and body size in reproduction; while for males, they were mating ability, growth rate, and body size.

In general, studies in semi-arid regions indicate local criteria for selecting animals for reproduction in family farming systems, based on appearance and adaptive characteristics. This information is useful for developing improvement programs for breeder communities, as demonstrated by Mueller [30]. On the other hand, studies conducted in controlled breeding systems adopt criteria more related to production, as these environments support animals of specialized breeds, for which the literature is extensive across all species.