Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

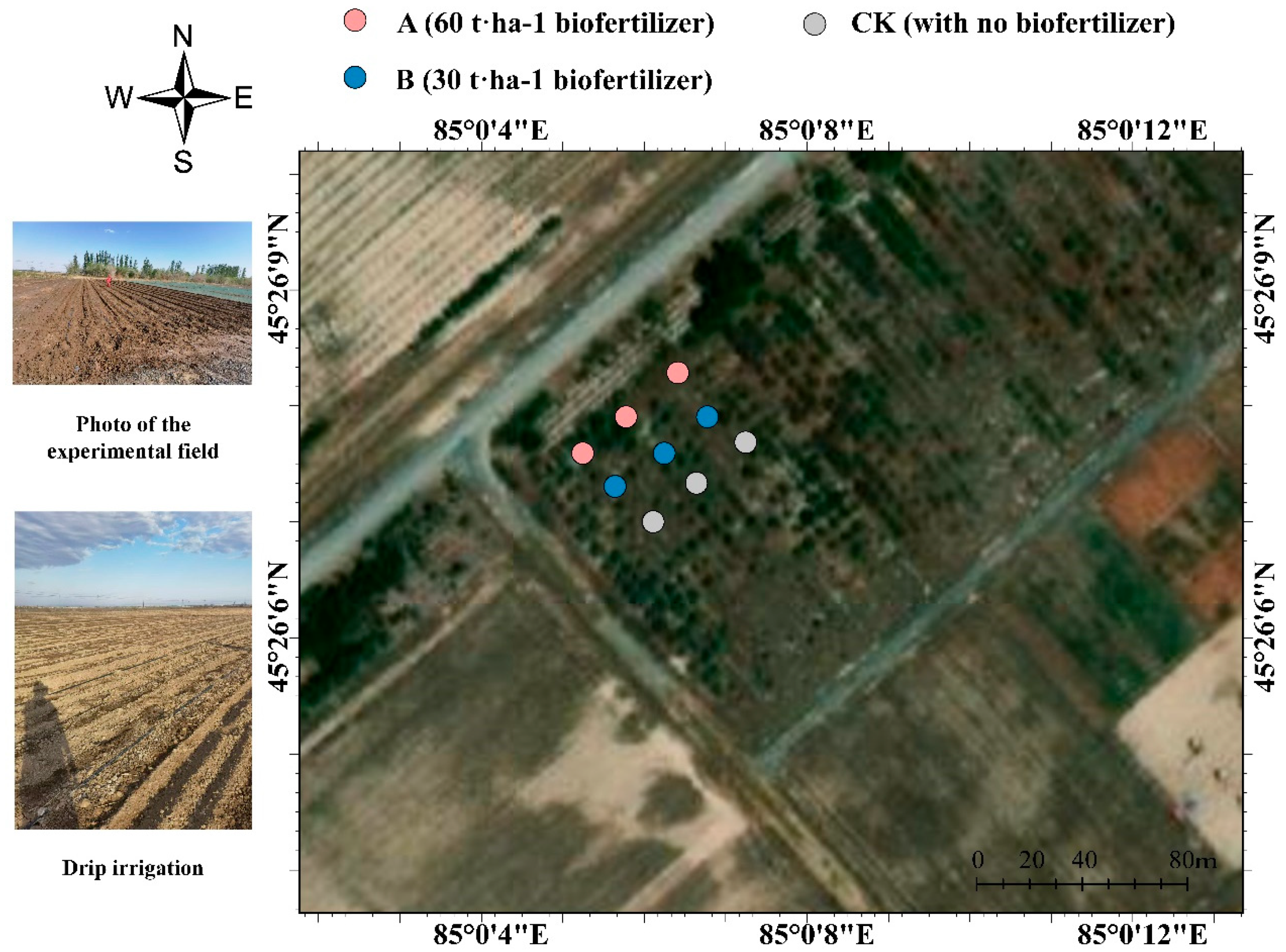

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Field Experiment Design

2.3. Soil Sampling and Measurement

2.4. Plant Sampling and Measurement

2.5. Carbon Sequestration Accounting

2.6. Soil Enzymes Activities Measurement

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

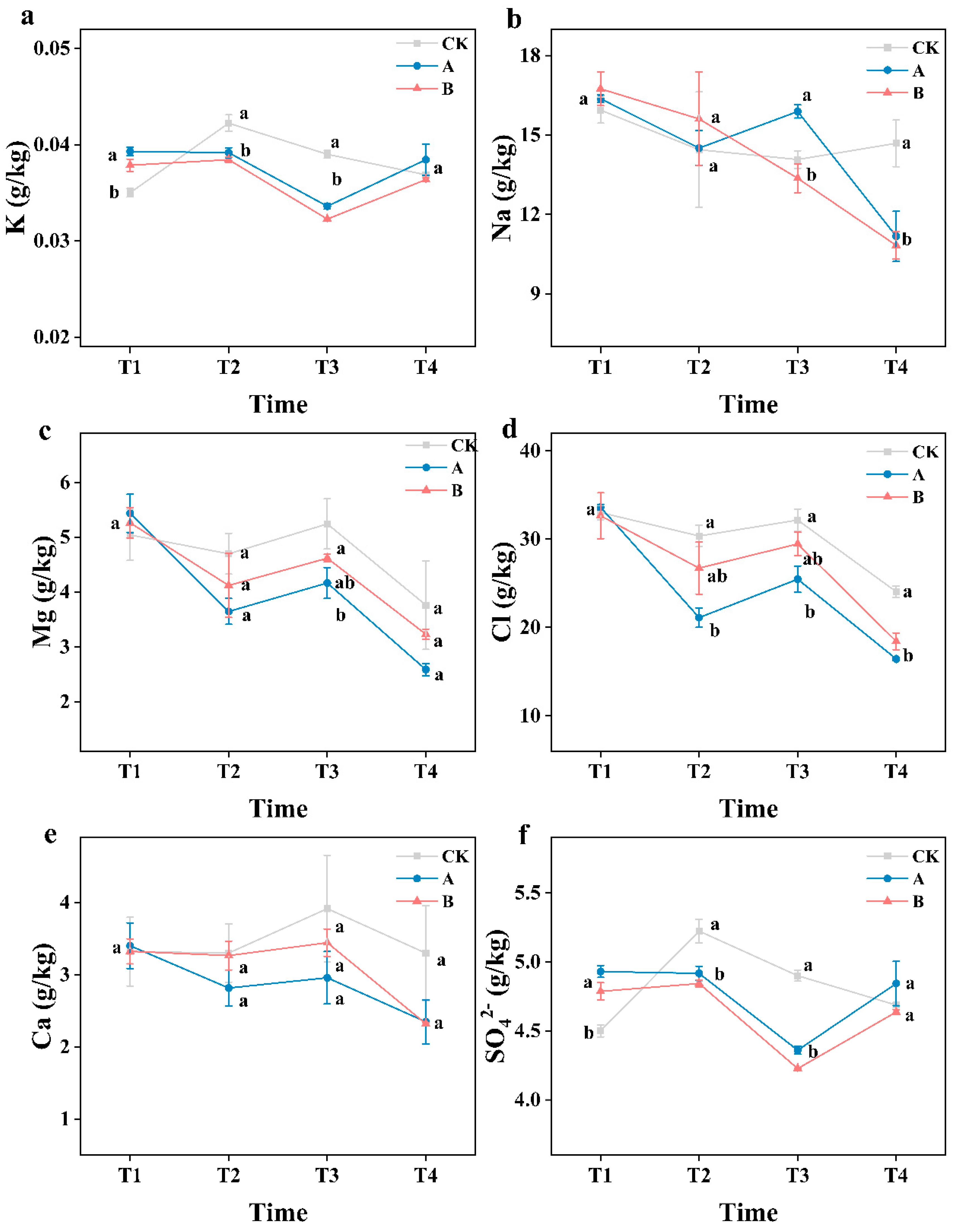

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties

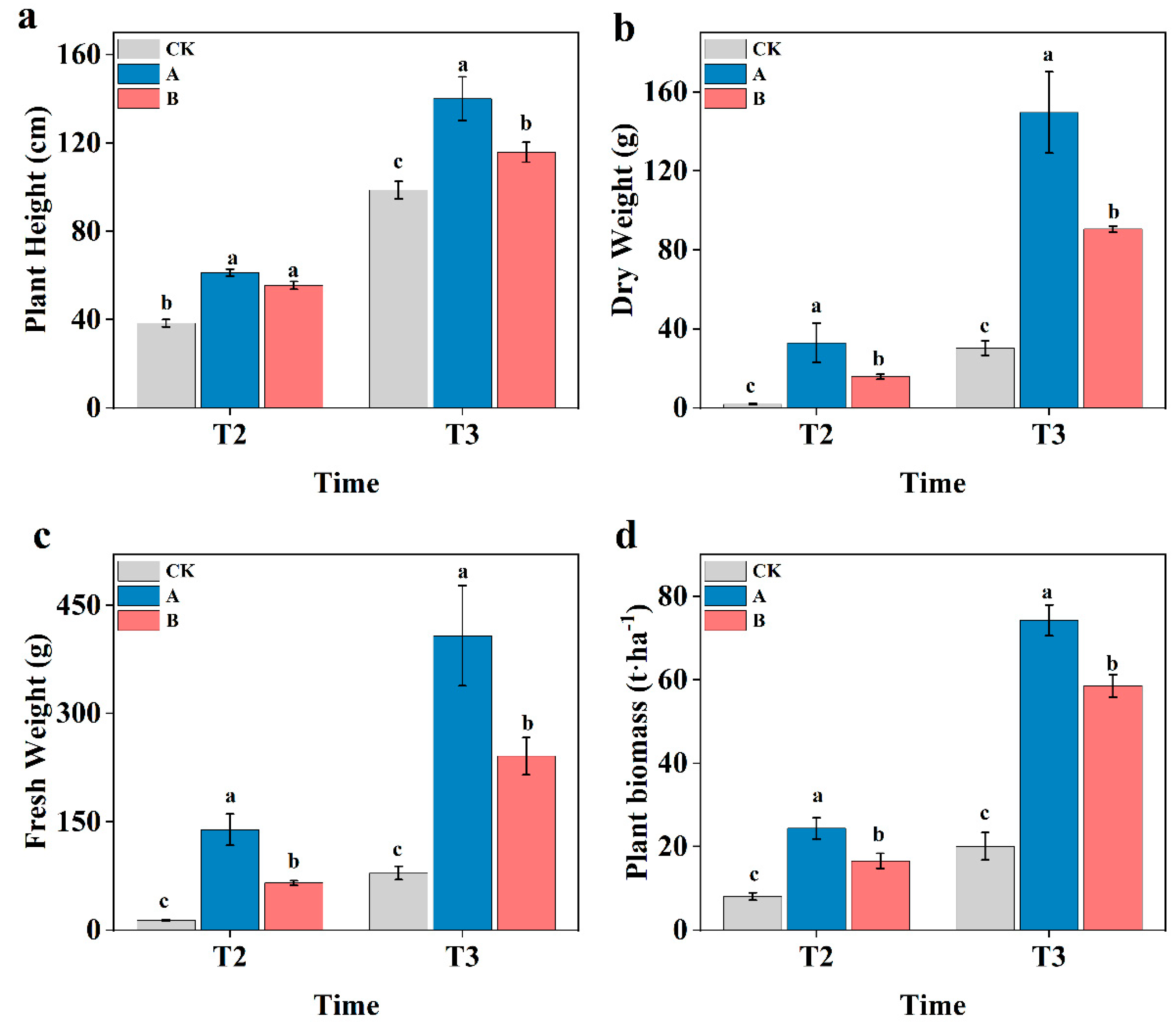

3.2. Biomass and Physiological Characteristics of S. salsa

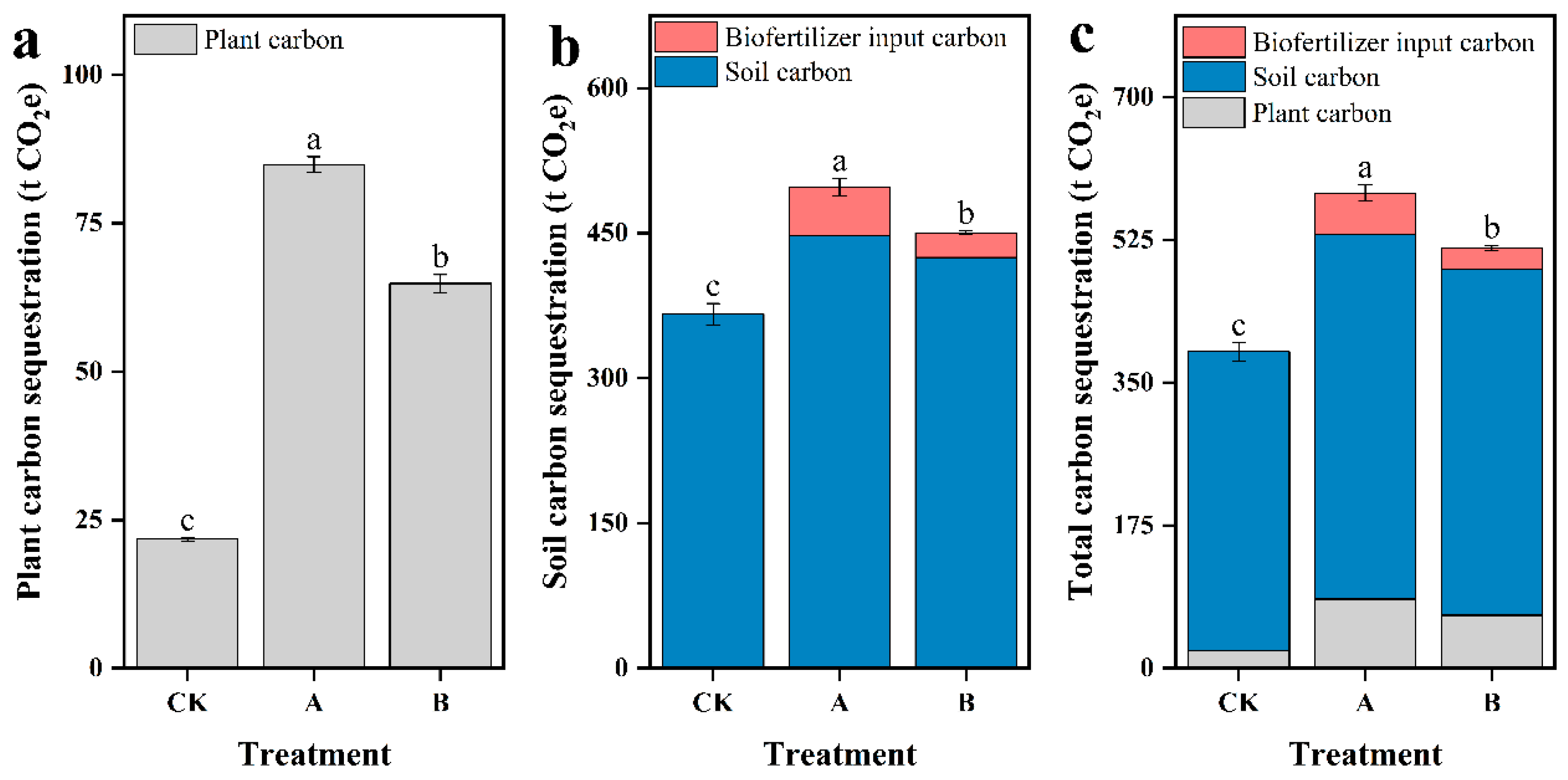

3.3. Calculation of Carbon Sequestration

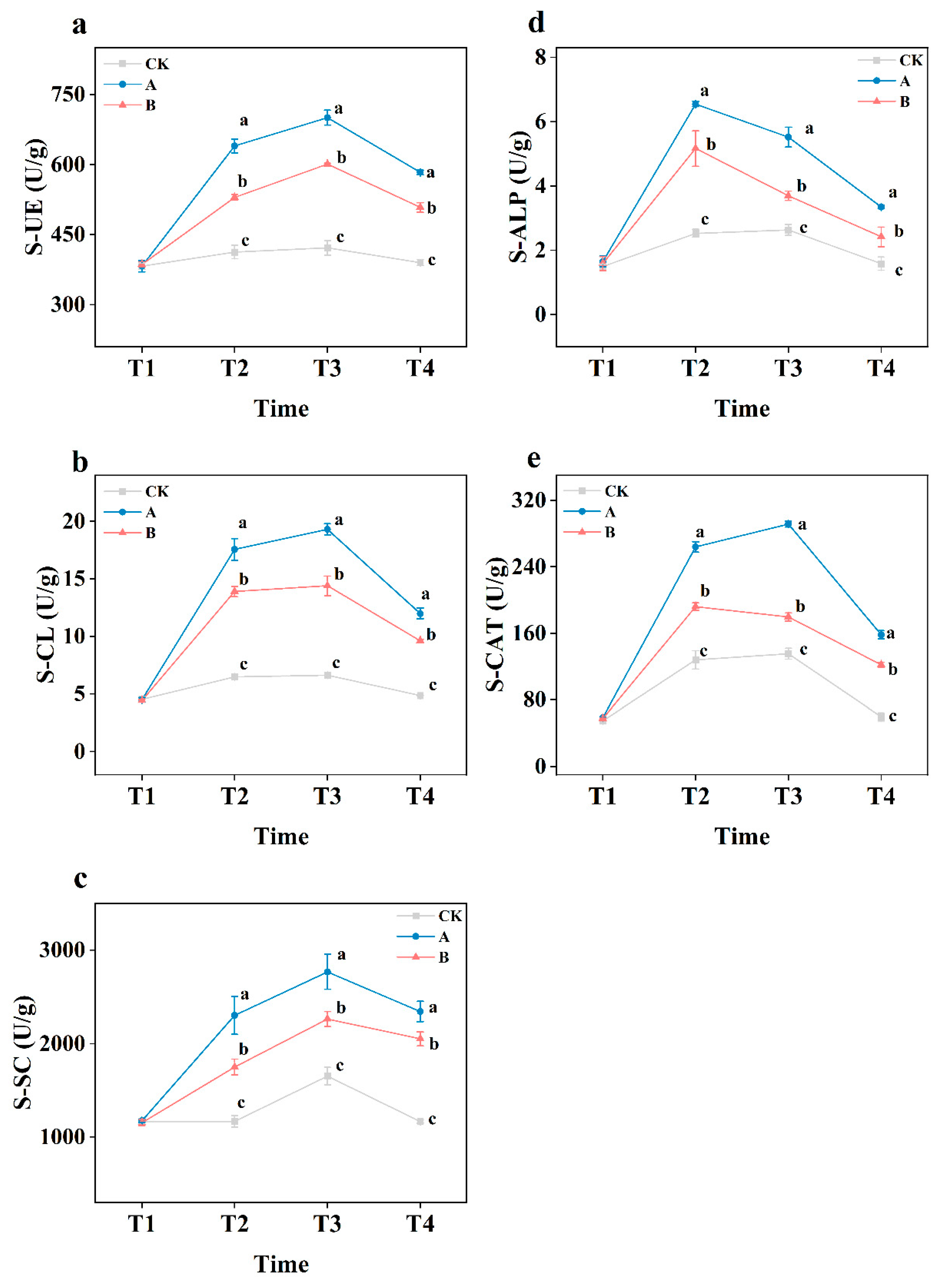

3.4. Soil Enzymes Activities

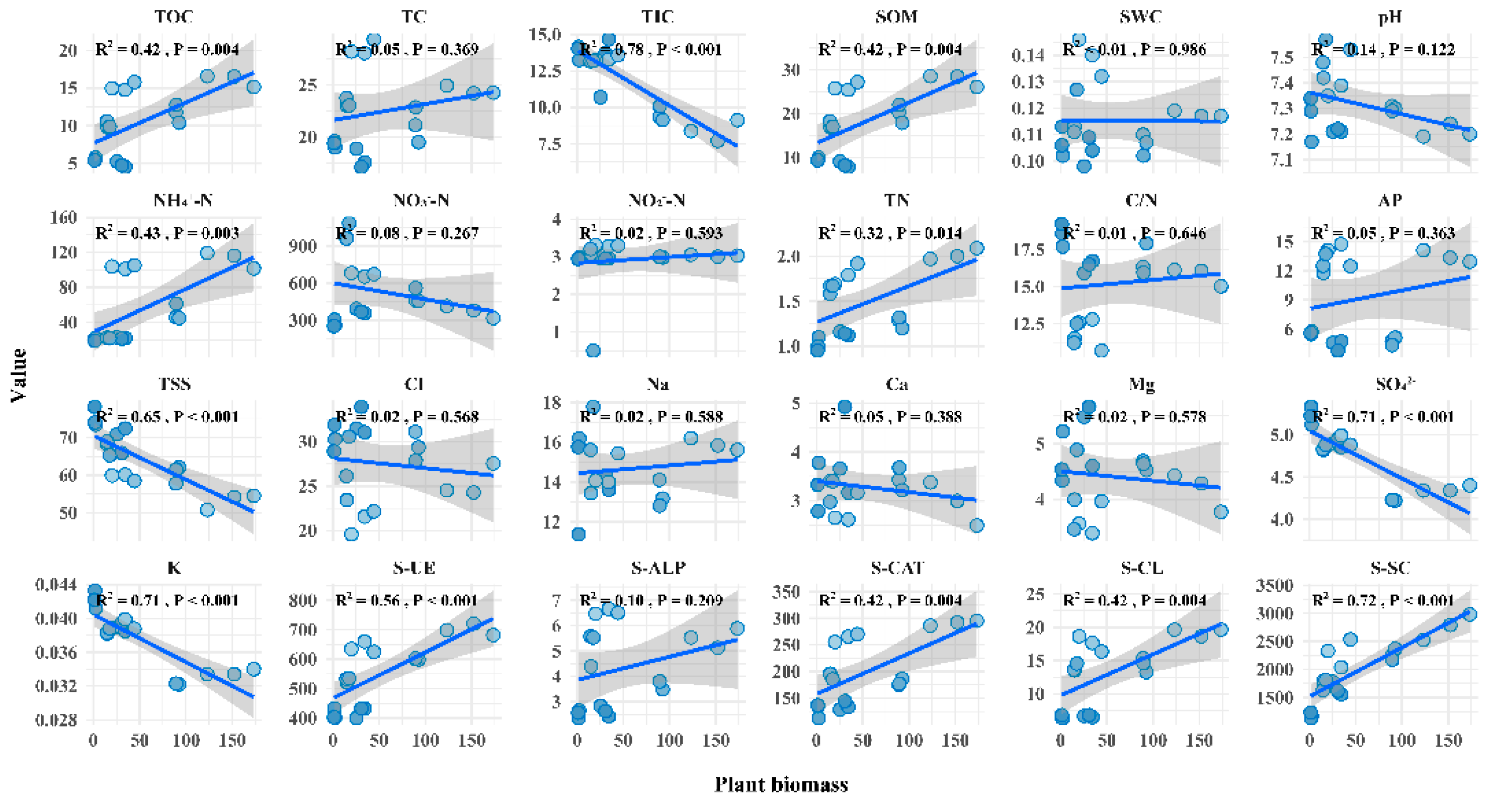

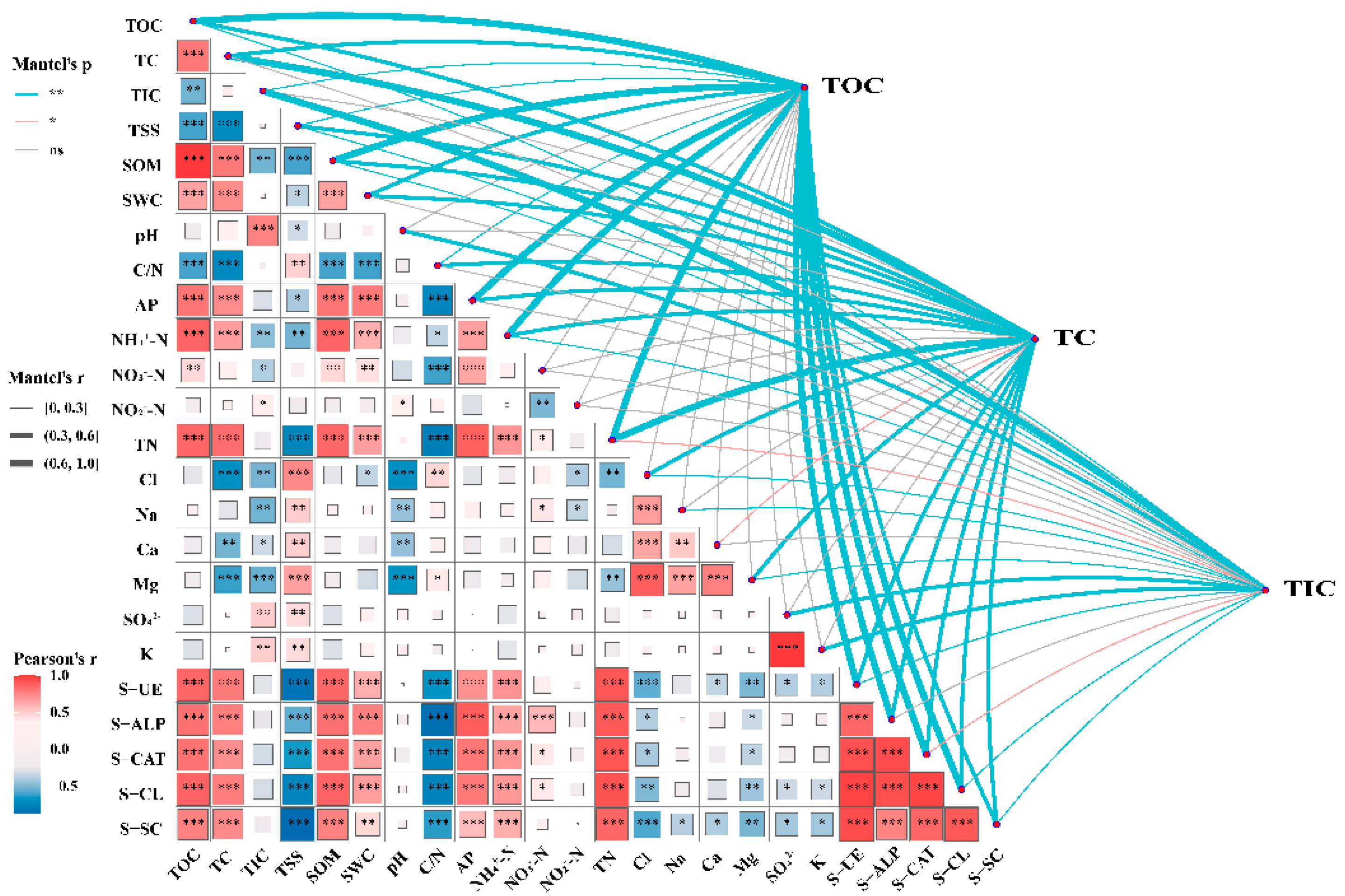

3.5. Interaction of Environmental Factors and Their Relationship with Soil Carbon Components

4. Discussion

4.1. Improvement of Saline-Alkali Soil by Biofertilizer

4.2. Growth Promotion of S. salsa by Biofertilizer

4.3. Enhancement of Soil Enzymes Activities by Biofertilizer

4.4. Interaction of Biotic and Abiotic Factors and Its Impact on Carbon Sequestration

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.; Yu, Y.; Nan, S.; Chai, Y.; Xu, W.; Qin, Y.; Li, X.; Bodner, G. Conversion of SIC to SOC Enhances Soil Carbon Sequestration and Soil Structural Stability in Alpine Ecosystems of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 195, 109452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternicht, G.I.; Zinck, J.A. Remote Sensing of Soil Salinity: Potentials and Constraints. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Land Exploitation Resulting in Soil Salinization in a Desert–Oasis Ecotone. Catena 2013, 100, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xue, L.; Liu, J.; Xia, L.; Jia, P.; Feng, Y.; Hao, X.; Zhao, X. Biochar Application Reduced Carbon Footprint of Maize Production in the Saline−alkali Soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 368, 109001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Y.; Wu, X.; Ni, H.; Lu, Q.; Zang, S. Long-Term Surface Composts Application Enhances Saline-Alkali Soil Carbon Sequestration and Increases Bacterial Community Stability and Complexity. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Hou, N.; Li, D. Remediation of Soda-Saline-Alkali Soil through Soil Amendments: Microbially Mediated Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles and Remediation Mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Cui, H.; Fu, C.; Li, R.; Qi, F.; Liu, Z.; Yang, G.; Xiao, K.; Qiao, M. Unveiling the Crucial Role of Soil Microorganisms in Carbon Cycling: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Yuan, H.; Xie, J.; Ge, L.; Chen, Y. Herbaceous Plants Are Better than Woody Plants for Carbon Sequestration. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 184, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Q.; Gao, T.; Wang, G.G. Mycorrhizal Type Regulates Trade-Offs between Plant and Soil Carbon in Forests. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Bramston, D. A Planting Optimization Strategy to Improve the Carbon Sink Benefit for Urban Green-Taking the Communal Green of Nanjing Forestry University as an Example. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, D.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Miao, Y.; Chen, Z.; He, T.; Ding, W. Wetland Restoration after Agricultural Abandonment Enhances Soil Organic Carbon Efficiently by Stimulating Plant- Rather than Microbial-Derived Carbon Accumulation in Northeast China. Catena 2024, 241, 108077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Zamanian, K.; Chang, F.; Yu, R.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y. Inorganic Carbon Accumulation in Saline Soils via Modification Effects of Organic Amendments on Dissolved Ions and Enzymes Activities. Catena 2024, 241, 108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, M. Synergistic Improvement of Carbon Sequestration and Crop Yield by Organic Material Addition in Saline Soil: A Global Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Su, X.; Meng, H.; Wang, H.; Yan, X.; Qin, D.; Liu, C.; Men, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, X.; et al. Long-Term Cotton Stubble Return and Subsoiling Improve Soil Organic Carbon by Changing the Stability and Organic Carbon of Soil Aggregates in Coastal Saline Fields. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 241, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, G.A.; Glick, B.R.; Yaish, M.W. Salt Tolerance in Plants: Using OMICS to Assess the Impact of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB). In Mitigation of Plant Abiotic Stress by Microorganisms; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 299–320 ISBN 978-0-323-90568-8.

- Cai, J.-F.; Fan Jiang; Liu, X. -S.; Sun, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.-X.; Li, H.-L.; Xu, H.-F.; Kong, W.-J.; Yu, F.-H. Biochar-Amended Coastal Wetland Soil Enhances Growth of Suaeda Salsa and Alters Rhizosphere Soil Nutrients and Microbial Communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J.; Hao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Guo, W. Bio-Organic Fertilizer Promoted Phytoremediation Using Native Plant Leymus Chinensis in Heavy Metal(Loid)s Contaminated Saline Soil. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 327, 121599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xue, R.; Zhang, Q. Soil Enzyme Activity Mediated Organic Carbon Mineralization Due to Soil Erosion in Long Gentle Sloping Farmland in the Black Soil Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Tang, J.; Liu, B.; Lyu, H.; Duan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Z. Rhizosphere Enzyme Activities and Microorganisms Drive the Transformation of Organic and Inorganic Carbon in Saline–Alkali Soil Region. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Gu, L.; Bao, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zhuang, G.; Zhuang, X. Application of Biofertilizer Containing Bacillus Subtilis Reduced the Nitrogen Loss in Agricultural Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Bai, Z.; Bao, L.; Xue, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhuang, G.; Zhuang, X. Bacillus Subtilis Biofertilizer Mitigating Agricultural Ammonia Emission and Shifting Soil Nitrogen Cycling Microbiomes. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhuang, G.; Bai, Z.; Cen, Y.; Xu, S.; Sun, H.; Han, X.; Zhuang, X. Mitigation of Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Acidic Soils by Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens, a Plant Growth-promoting Bacterium. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 2352–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, H.; Hou, R.; Sun, Z.; Ouyang, Z. Soil Microbes from Saline–Alkali Farmland Can Form Carbonate Precipitates. Agronomy 2023, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Sun, B.; Song, M.; Yan, G.; Hu, Q.; Bai, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhuang, X. Improvement of Saline Soil Properties and Brassica Rapa L. Growth Using Biofertilizers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tian, C.; Zhang, R.; Mohamed, I.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Pan, J.; Chen, F. Plastic Mulching with Drip Irrigation Increases Soil Carbon Stocks of Natrargid Soils in Arid Areas of Northwestern China. Catena 2015, 133, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Wang, H.; Ma, C.; Wu, C.; Zheng, X.; Xie, L. Carbon Sinks and Carbon Emissions Balance of Land Use Transition in Xinjiang, China: Differences and Compensation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hao, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; Su, D. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Saline-Alkali Land Improvement and Utilization on Soil Organic Carbon. 2022.

- Li, C.Y.; He, R.; Tian, C.Y.; Song, J. Utilization of Halophytes in Saline Agriculture and Restoration of Contaminated Salinized Soils from Genes to Ecosystem: Suaeda Salsa as an Example. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 197, 115728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; LinkET: Everything Is Linkable. R Package Version 0.0.3 2021. Available online: https://github.com/Hy4m/linkET (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Kuzyakov, Y. Priming Effects: Interactions between Living and Dead Organic Matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, P.C. Soil Organic Matter/Carbon Dynamics in Contrasting Tillage and Land Management Systems: A Case for Smallholder Farmers with Degraded and Marginal Soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2017, 48, 2013–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L.; Xuan, J.; Chen, A.; You, C. Short-Term Phosphorus Addition Augments the Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Soil Respiration in a Typical Steppe. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Arya, V.M.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, S.; Popescu, S.M.; Thakur, N.; M. Iqbal, J.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Baath, G.S. Impact of Cropping Intensity on Soil Nitrogen and Phosphorus for Sustainable Agricultural Management. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2024, 36, 103244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, D.; Shi, C.; Sun, Q.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of Vegetation Restoration on the Temporal Variability of Soil Moisture in the Humid Karst Region of Southwest China. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, J.; Xu, D.; Wu, B.; Chang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wei, Z. Soil Salinization Poses Greater Effects than Soil Moisture on Field Crop Growth and Yield in Arid Farming Areas with Intense Irrigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 451, 142007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Rasool, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, T. Biochar and Chlorella Increase Rice Yield by Improving Saline-Alkali Soil Physicochemical Properties and Regulating Bacteria under Aquaculture Wastewater Irrigation. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Feng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H. Dynamic Changes in Water and Salinity in Saline-Alkali Soils after Simulated Irrigation and Leaching. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0187536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, N.; Li, D.; Tian, C.; Zhang, K.; Hu, M.; Niu, H.; Zhao, Z. Effects of Halophyte Suaeda Salsa Continuous Cropping on Physical and Chemical Properties of Saline Soil under Drip Irrigation in Arid Regions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 371, 109076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Wang, S.; Cui, C.; Wu, X.; Zhu, J. Suaeda Salsa NRT1.1 Is Involved in the Regulation of Tolerance to Salt Stress in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; He, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Kong, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hu, R. Biochar Amendment Ameliorates Soil Properties and Promotes Miscanthus Growth in a Coastal Saline-Alkali Soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 155, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R.; Burr, M.D.; Camper, A.K.; Moss, J.J.; Stein, O.R. Seasonality, C:N Ratio and Plant Species Influence on Denitrification and Plant Nitrogen Uptake in Treatment Wetlands. Ecological Engineering 2023, 191, 106946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; He, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Lin, Z.; Yu, L.; Wei, X.; Zhang, W.; Geng, Y.; et al. Different Microbial Functional Traits Drive Bulk and Rhizosphere Soil Phosphorus Mobilization in an Alpine Meadow after Nitrogen Input. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, A.T.; Ncube, B.; Meyer, A.H.; Olatunji, O.S.; Mulidzi, R.; Lewu, F.B. Soil pH, Nitrogen, Phosphatase and Urease Activities in Response to Cover Crop Species, Termination Stage and Termination Method. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollavali, M.; Bolandnazar, S.A.; Schwarz, D.; Rohn, S.; Riehle, P.; Zaare Nahandi, F. Flavonol Glucoside and Antioxidant Enzyme Biosynthesis Affected by Mycorrhizal Fungi in Various Cultivars of Onion ( Allium Cepa L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-M.; Li, Q.; Liang, W.-J.; Jiang, Y. Distribution of Soil Enzyme Activities and Microbial Biomass Along a Latitudinal Gradient in Farmlands of Songliao Plain, Northeast China. Pedosphere 2008, 18, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Wu, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, H.; Qiao, Y. Different Responses of Enzyme Activities to 6-year Warming after Transplant of the 12 Types of Soils. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2023, 186, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Wang, B.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, P. Calcium Alginate−biochar Composite Promotes Nutrient Retention, Enzyme Activity, and Plant Growth in Lime Soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 35, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y. The Effects of Biochar Addition on Soil Physicochemical Properties: A Review. Catena 2021, 202, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, G.; Lin, Y.; Li, B. Effects of Conservation Tillage on Soil Enzyme Activities of Global Cultivated Land: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 345, 118904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, T.; Xue, X.; Wu, L.; Zhou, W.; Yun, X.; Yan, R.; et al. Moderate Grazing Increased Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Storage in Plants and Soil in the Eurasian Meadow Steppe Ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Mao, J.-H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y. Carbon Capture by Phytomass Storage and Trading to Mitigate Climate Change and Preserve Natural Resources. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 22, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, Q.; Li, X. Promoting Sustainable Carbon Sequestration of Plants in Urban Greenspace by Planting Design: A Case Study in Parks of Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, F.; Hasse, U. Permanent Wood Sequestration: The Solution to the Global Carbon Dioxide Problem. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Price, G.W.; Liang, C.; Burton, D.L.; Lynch, D.H. Effects on Soil Carbon Storage from Municipal Biosolids Application to Agricultural Fields. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 361, 121249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bughio, M.A.; Wang, P.; Meng, F.; Qing, C.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wang, X.; Junejo, S.A. Neoformation of Pedogenic Carbonates by Irrigation and Fertilization and Their Contribution to Carbon Sequestration in Soil. Geoderma 2016, 262, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Zhu, E.; Jia, J.; Feng, X. Shifting Relationships between SOC and Molecular Diversity in Soils of Varied Carbon Concentrations: Evidence from Drained Wetlands. Geoderma 2023, 433, 116459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Effects of the Interaction between Biochar and Nutrients on Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration in Soda Saline-Alkali Grassland: A Review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wu, J.; Pan, X.; Tan, X.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, Q.; Liu, T.; Zeng, Y. Effects of Long-Term Straw Return on Soil Organic Carbon Fractions and Enzyme Activities in a Double-Cropped Rice Paddy in South China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Taylor, P.; Richter, A.; Porporato, A.; Ågren, G.I. Environmental and Stoichiometric Controls on Microbial Carbon-use Efficiency in Soils. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, C.; Peñuelas, J. Rhizodeposition under Drought and Consequences for Soil Communities and Ecosystem Resilience. Plant Soil 2016, 409, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkanç, S.Y. Effects of Afforestation on Soil Organic Carbon and Other Soil Properties. Catena 2014, 123, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Irshad, A.; Margenot, A.; Zamanian, K.; Li, N.; Ullah, S.; Mehmood, K.; Ajmal Khan, M.; Siddique, N.; Zhou, J.; et al. Inorganic Carbon Is Overlooked in Global Soil Carbon Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Geoderma 2024, 443, 116831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, J. Soil Inorganic Carbon Storage and Spatial Distribution in Irrigated Farmland on the North China Plain. Geoderma 2024, 445, 116887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Zamanian, K.; Ullah, S.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Virto, I.; Zhou, J. Inorganic Carbon Losses by Soil Acidification Jeopardize Global Efforts on Carbon Sequestration and Climate Change Mitigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Feng, B.; Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, F.; Shen, C.; Ma, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Saline–Alkali Land Reclamation Boosts Topsoil Carbon Storage by Preferentially Accumulating Plant-Derived Carbon. Sci. Bull. 2024, S2095-9273(24)00357-8, doi:10.1016/j.scib.2024.03.063. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, M.; Ding, S.; Liu, B.; Chang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Grassland Degradation with Saline-Alkaline Reduces More Soil Inorganic Carbon than Soil Organic Carbon Storage. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.P.; Lohse, K.A.; Commendador, A.; Joy, S.; Aho, K.; Finney, B.; Germino, M.J. Vegetation and Precipitation Shifts Interact to Alter Organic and Inorganic Carbon Storage in Cold Desert Soils. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Qiu, Y.; Hu, S. Nitrogen Availability Mediates the Effects of Roots and Mycorrhizal Fungi on Soil Organic Carbon Decomposition: A Meta-Analysis. Pedosphere 2024, 34, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-B.; Zhang, R.-D. Dynamics of Soil Organic Carbon Under Uncertain Climate Change and Elevated Atmospheric CO2. Pedosphere 2012, 22, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Tian, P.; Ai, J.; Yang, Y.; Zamanian, K.; Zeng, Z.; Zang, H. Enhanced Soil Organic Carbon Stability in Rhizosphere through Manure Application. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 244, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, L.; Meng, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.; Song, X.; Zhang, X.; Mao, L. Long-Term Conservation Tillage Increase Cotton Rhizosphere Sequestration of Soil Organic Carbon by Changing Specific Microbial CO2 Fixation Pathways in Coastal Saline Soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).