1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Requirements

The increasing use of Fibre Reinforced Polymers (FRPs) for the manufacturing of critical components in demanding environments has created a need for reliable online assessment methods based on Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) techniques. Compared with metals and alloys used in advanced structural applications, FRPs often demonstrate superior performance coupled with excellent mechanical properties characteristics while eliminating common degradation mechanisms associated with corrosion and Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC). These advantages arise from their microstructural characteristics, which incorporate either unidirectional or multidirectional fibre configurations embedded within a polymer matrix. Thus, their properties and performance can be precisely tailored to meet the specific application requirements [

1]. However, these microstructural characteristics also introduce complex damage mechanisms, further complicating direct inspection due to the anisotropic nature of FRPs.

Standard inspection of FRP components relies on Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) techniques to assess the type of defects and their severity within a structure. One commonly used NDT method for the inspection of FRPs is Ultrasonic Testing (UT). UT enables the accurate detection and localisation of defects and damage within FRP components [

2]. However, a key limitation of this technique is that the sensitivity and resolution of the inspection is dependent on the frequency of the probe used. Moreover, damage can only be detected during an inspection and not while the component is in service. This limits the opportunities during which UT can be carried out whilst defects smaller than half the wavelength of the ultrasonic beam cannot be detected at all. Thus, UT cannot be used for real-time monitoring of damage initiation and subsequent propagation, potentially resulting in lower availability due to the time that the components have to be taken off line in order to undergo inspection.

Since damage can only be evaluated periodically, predicting how the damage detected may progress over time is required. However, for FRPs this is not straightforward and approaches such as the Paris-Erdogan law and the Palmgren-Miner Linear damage hypothesis do not usually work well. Hence, it is not always possible to achieve sufficient accuracy in structural degradation predictions. Wind Turbine Blades (WTBs) are large-scale industrial FRP structures commonly installed in remote locations, Manual inspection apart from requiring a shutdown of the wind turbine can be affected by limited accessibility due to weather conditions. Also, WTBs are subject to stochastic loads and adverse environmental conditions. This means degradation can accelerate unexpectedly and remain undetected until the next opportunity for inspection. In the event where severe damage is detected, repair or replacement will need to be scheduled based on the availability of necessary spare blades and lifting equipment. Therefore, real-time SHM has distinct advantages over conventional inspection methods. Apart from allowing the continuous evaluation of the structural health of WTBs it can contribute to the effective planning and scheduling of the maintenance intervention required.

The implementation of a reliable SHM system can help ensure the reliability of large FRP structures, including WTBs, enabling the accurate, effective and cost-efficient maintenance planning. Acoustic Emission (AE) is a passive technique that can be used for the effective SHM of composite structures. However, the characterisation and quantitative evaluation of the severity of damage detected using existing approaches for AE data interpretation are challenging. Within the present study we report on the development of a novel methodology for the accurate real-time characterisation and quantitative assessment of damage detected in composite structures using AE.

1.2. Current Approaches

Monitoring and evaluation of FRP structures using AE relies on the use of Digital Signal Processing (DSP) techniques to extract features from the recorded signals. These signal features can subsequently be used to evaluate the characteristics of the damage detected. There are several methods and approaches to achieve this, although the accuracy can vary significantly between them. In the proposed methodology, frequency components in the AE signal recorded can help increase accuracy in the evaluation of severity and characteristics of the damage events detected. Unlike other parameters which can be extracted from an AE signal, such as peak amplitude, AE energy, Root Mean Square (RMS), risetime etc., the effects of the acquisition settings, together with the amplification used and the distance between sensor and source can influence the values recorded, in turn effecting the conclusions drawn.

A more reliable approach for direct damage assessment can be achieved through evaluation of the input signal in the frequency domain, together with the relevant frequency components. A common way used extensively is through the evaluation of the peak frequency value of a captured AE event. Frequency values can be used in different ways to evaluate the damage mode. There are various mechanical tests that can be used to cause damage in FRPs and in turn monitor the associated peak frequency value. One approach, involves tests that result in individual damage modes to occur through specific experimental setups, such as matrix cracking caused during mechanical testing of a pure resin system [

3,

4]. Such tests ensure the observation of the intended damage mode. However, they do not account for any behavioural differences resulting from the structural differences and the effects of the constituent components. Alternatively, more general mechanical testing can be carried out where no target damage mode is specified, instead aiming to replicate a realistic loading pattern for a component or material [

5], such as tensile testing for a tensile-tensile loading system or flexural testing for a tensile-compressive system. The peak frequency, amplitude, and energy of the AE signals obtained during such tests must be typically correlated to damage sustained by simultaneously evaluating the stress-strain curve.

1.3. Departure from Consideration of Singular Frequency Values

FRPs exhibit anisotropic mechanical properties which are strongly dependent on the fibre orientation. Fibre orientation and anisotropy characteristics of FRP materials introduce an additional level of complexity when studying the transmission of elastic stress waves through the material [

6]. Taking into consideration how an individual elastic stress wave generated at the crack tip as it propagates and attenuates within the structure the frequency domain-based analysis becomes advantageous over time domain-based evaluation.

The propagation of Lamb waves in plate structures can be characterised by phase (c

p) and group velocities (c

g). The group velocity refers to the entire wave package, and the velocity at which it propagates within the medium. However, within a wave package and its constituent group, exist individual phases, of different frequencies, and in turn different velocities (c

p). Let us consider a wave package emitted from an event within the material, such as matrix cracking combined with fibre fracture, which excites the surrounding particles at two distinct energy levels, hence producing two distinct frequencies. For this individual wave package, containing varying frequency components from the same source, detection and evaluation of these is possible, providing the ability for their simultaneous assessment. This is due to the dispersion of the associated phase velocities (

cp) within the overall group velocity (

cg); hence the arrival time of these components will propagate faster or slower accordingly. Dispersion allows for each of the phases to be individually assessed, as there is limited overlapping or combination when considering the captured signal [

6,

7].

A multi-variant-based methodology for the analysis of AE signals through which the simultaneous occurrence of multiple damage modes can be assessed and quantified is of significant interest. Using the proposition of discrete frequency ranges that have been attributed to specific damage modes, and the separation of frequencies within a wave package due to dispersion in the cp, designation of more than one frequency for the description of an AE event is required. By taking into consideration peak frequency rather than signal amplitude, we can distinguish damage initiation and early onset of damage evolution from later stages of damage propagation, delamination, and final failure. In conventional analysis of AE signals delamination-related events can overlap with extensive matrix cracking which would influence the accuracy of the interpretation of the structural health of the structure significantly.

Consideration of the frequency spectra beyond the observed peak frequency, as suggested above, has been explored to some extent in previous studies [

3,

8]. This is achieved through the use of Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) upon an extracted waveform, and the in-depth assessment of the produced frequency domain representation. Fotouhi et al. demonstrated the presence of multiple peaks in the frequency spectra related to multiple damage types for a singular damage event [

8]. This is limited, however, by its lack of expandability, focusing only on a few damage events. Similarly, labelling and attribution of further peaks within a produced frequency spectra for a damage event was completed by Bussiba et. al. for the rationalisation of the damage processes seen within an FRP [

3]. However, the work that has been reported in previous studies did not cover all damage events during testing but instead the analysis was only applied to a few examples.

The use of Wavelet Transforms (WTs) has been studied to assess the frequency components of a given AE signal. WTs were explored by Qi to determine damage in FRP materials [

9]. Barile et al. focused on Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) for the evaluation of the relative energies of the spectral components within an input waveform [

10], essentially evaluating the energy distribution within the frequency spectrum of the AE signals. Within this study the frequency ranges assigned seem to overlap to frequencies assigned to different damage modes.

The aim of the technique studied herewith is to allow for the accurate characterisation and evaluation of severity of different forms of damage occurring within FRP structures. To implement a quantitative AE system accurate characterisation and evaluation of severity of damage modes is required.

2. Materials and Methods

The materials and equipment used in the study are outlined in the following sections.

2.1. Materials

The test coupons used in the present study were manufactured using the resin infusion process as part of the Horizon 2020 Carbo4Power project using a layered lamina structure. The tensile coupon samples tested were 250 mm long with a width of 25 mm and a thickness between 1.03-1.33 mm. The layup of [0/45/QRS/-45/90]. Quantum Resistive Sensors (QRS) had been embedded within each sample for monitoring strain, temperature or humidity. Samples were end-tabbed using resin. Sample coupons for flexural testing had a length of 150 mm, width of 25 mm and thickness of 1.15-1.32 mm, with a layup of [0/QRS/45/-45/90], with no end tabbing required.

2.2. Mechanical Testing

Mechanical testing was carried out to collect the required data used for the present study as well as qualify the materials for use in the manufacturing of the demonstration blades planned within the CARBO4POWER project. Tensile and flexural (3-point bending) tests were carried out on the available samples.

Tensile testing was completed using a Zwick-Roell electro-mechanical testing machine, model number 1484, with a 200 kN loadcell, a crosshead movement speed of 2 mm/min and the extensometer set at 10 mm. Flexural testing was completed using a Dartec Universal Mechanical Testing Machine with a 50 kN load cell and crosshead movement speed of 1 mm/min

2.3. Acoustic Emission Acquisition

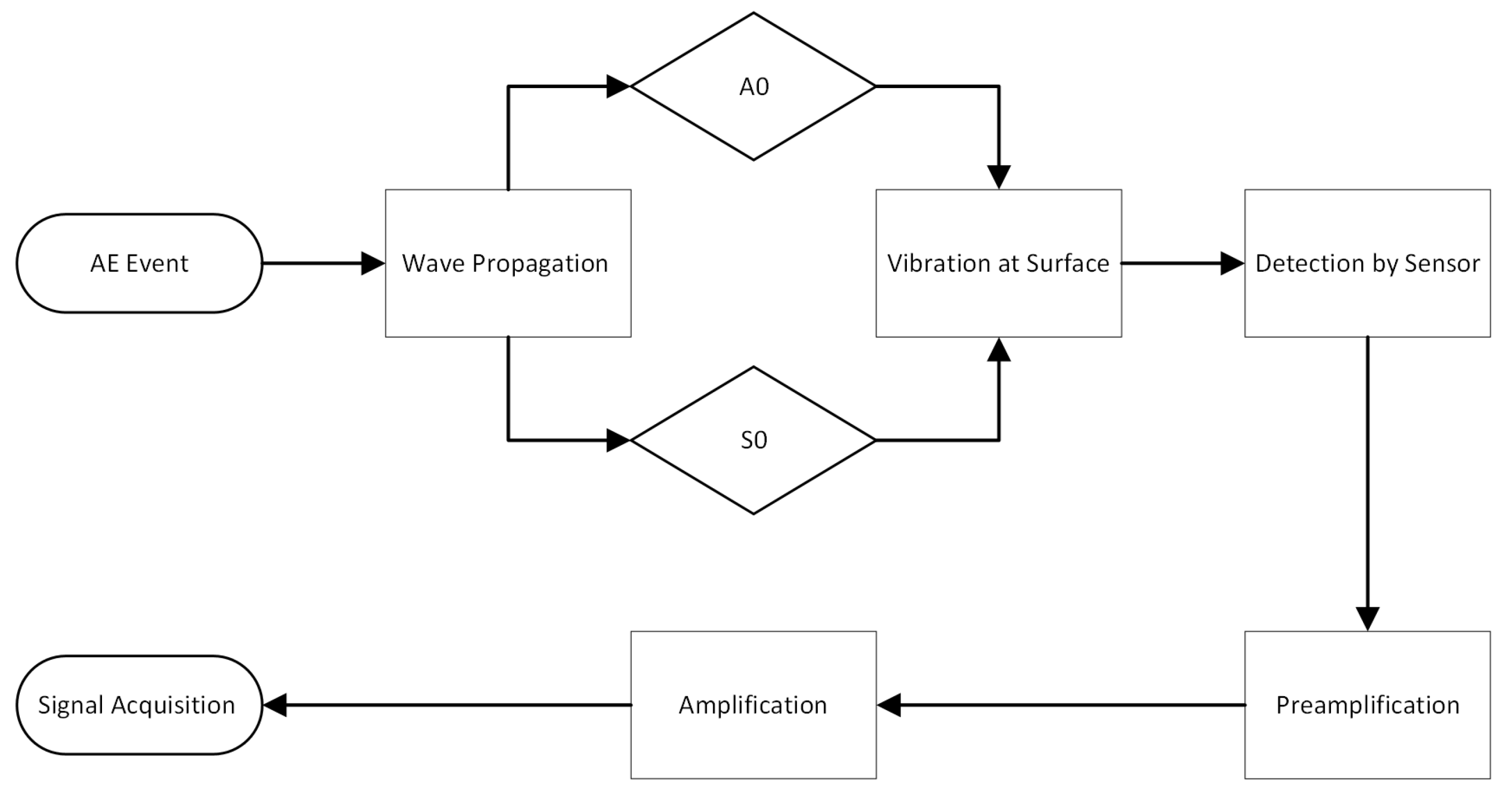

During the mechanical testing a customised 4-channel AE acquisition system built by the authors at the University of Birmingham was used. AE activity was detected using an R50α resonant sensor, with an operational frequency range of 100 – 700 kHz [

11]. The sensor was mounted on the sample surface using Araldite

®, a two-component epoxy adhesive, which also acted as couplant. The output from the AE sensor was subject to a pre-amplification and a main amplification. Pre-amplification was achieved through PAC 2/4/6 pre-amplifiers set at 40 dB. The main amplification was achieved using a Feldman Enterprises Ltd. 4-channel amplifier applying with amplification set at 9 dB. The AE signals were filtered at 500 kHz for anti-aliasing purposes and digitised using a 4-channel 16-bit National Instruments 9223 Compact Data Acquisition (NI-cDAQ) module. The NI-cDAQ module was connected to a compact Intel Next Unit of Computing (NUC) computer using a cDAQ-9171 connected via a USB port. The data acquisition was performed using custom-written software in MATLAB and developed in-house using NI-DAQmx running on the NUC computer. The recorded datasets were captured at 1MSamples/s per channel periodically for 5 seconds with a 1-second interval between each recording. The schematic diagram in

Figure 1 shows the overall system architecture.

2.4. Digital Signal Processing

The nature of the data captured using the customised acquisition system requires a bespoke data handling and DSP approach to translate the raw captured AE signal into usable information. This involves all necessary processes, including the importing and data handling, pre-processing and signal correction, location of damage events and extraction of relevant data, application of required signal processing techniques, identification and extraction of important information and finally the visualisation of the data completed with MATLAB-written software.

Several processes and operations are required in a DSP system. Herewith, we consider only the key ones applicable. One of these key processes, is the correction of the DC offset introduced to the signal during acquisition, using a defined threshold to prevent any unwanted electromechanical noise captured within the signal background being identified mistakenly as a damage event. However, due to the different materials considered in this study, selection of a single stationary value that would be suitable for all is not possible due to the different acoustic impedances. Hence, dynamic evaluation of an appropriate value based on the content of the signal was introduced. This allows for adjustments to be made based on the material being evaluated to account for any deviation in noise as well as prioritisation of the selection of damage related information contained in the signal. Following this, AE signals related to damage events can be identified, evaluated, extracted, labelled and timestamped accordingly. Once these have been identified for the input signals, the desired DSP technique, i.e., the Fourier transform using the FFT algorithm can be applied.

After this transformation, for both the peak frequency and multi-variant methods to be explored, there is need to employ further peak selection. For peak frequency, only the maxima of the spectra need to be selected. However, for the extraction of multiple peaks restrictions and selection parameters must be applied to ensure the accuracy of extracted values as well as prevent the selection of overlapping values.

3. Results

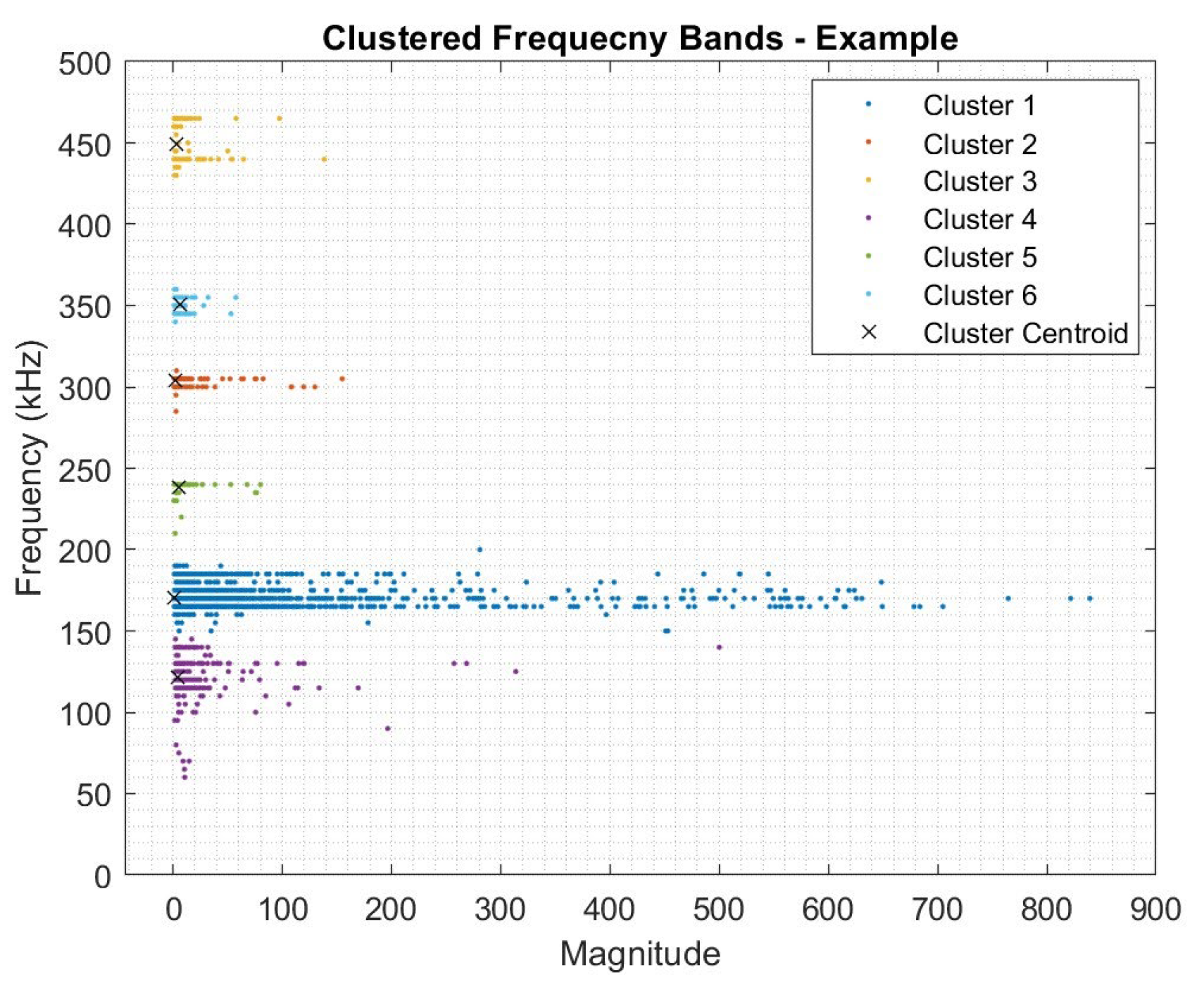

3.1. Peak Frequency Assessment and Damage Mode Classification

For the characterisation of the materials tested and damage evolution during testing frequency-based analysis can be used. In the present study, the peak frequency of AE signals related to damage events has been evaluated. To maximise the effectiveness of this technique, k-means clustering has been applied to evaluate the signal clusters arising as damage evolves and extract the values of these frequency bands. In this way damage events associated with different damage modes can be related to a different frequency range. Due to the nature of k-means clustering, some level of operator input and level of insight is required. This includes the number of clusters to be assigned, which is required to be specified technique advance [

12]. The number of clusters typically assigned should be equal to the expected number of damage modes observed in FRP structure, including matrix cracking, matrix-fibre debonding, interlaminar delamination, fibre fracture and fibre pullout [

13]. However, in practice this is not always sufficient, as variations in the aforementioned damage mechanisms can result in signals assigned to a single cluster. For example transverse and longitudinal matrix cracking, are two different mechanisms resulting in different AE signal intensity [

14]. As the energy of an event and frequency can be directly related to each other, it is feasible to attribute separate bands to each of these specific mechanisms, for differentiating them [

15,

16]. Hence for the application of k-means in this regard, 6 total clusters were assigned. Multiple applications of the k-means clustering algorithm on the same dataset were additionally performed to ensure that proper assignment of clusters was achieved, and for preventing misidentification [

17]. Misidentification can result depending on the way that clusters are assigned, e.g., applying random cluster centroids [

12]. This limits the reproducibility of the results, such that comparison with hand-labelled data is completed to ensure proper implementation.

Figure 2 demonstrates an example of the implementation of the discussed approach. Frequency vs. magnitude is used preferentially over a frequency vs. time representation as clusters are far greater pronounced and allow for more accurate evaluation. Based on the results obtained for a total of 9 tensile and 7 flexural CFRP samples the frequency ranges summarised in

Table 1 were established.

In the

Table 1, the two identified mechanisms for matrix cracking have been combined into a single band for simplicity, as well as having a lower threshold limit applied on this band despite data points existing below 100 kHz, as it can be seen in

Figure 1. Points detected within the frequency range of, 50-100 kHz fall outside any established trend, as well as being outside of the optimum sensitivity of the sensor being used, i.e., 100-700 kHz [

11]. The above given values are an overall approximation based on the complete dataset involving both tensile and flexural test results. It should be noted that not all samples displayed every possible damage mode listed when using the peak frequency assessment method. In such cases, a null value was entered and not included within the final evaluation. The specific values collected herewith for the range frequency band of each damage mode is difficult to be directly compared with the available literature [

18], in the sense that these values are a product of a specific material and its properties, alongside with the customised AE setup employed, particularly, the sensors used. However, the general ordering and their position relative with the frequency spectrum does align with literature values [

3,

5,

17,

19].

3.2. Multi-Variant Assessment

As highlighted earlier, the main drawback associated with the use of peak frequency for damage assessment in practice is the lack of consideration for damage, which is happening simultaneously, but at a lower intensity level. Even when a particular damage mode is not dominant, at least in terms of the spectral representation, it is still vital that it is evaluated as it may provide insight into the initiation of damage, allowing for its early detection and allowing maintenance intervention to be carried out timely. A simple yet effective means of implementing such a system involves analysis of the entire frequency spectra for each identified event within a captured AE signal. There are several ways in which this can be achieved, as explored within section 1.3 of the paper. Within the present study, two methods shall be considered. Main focus will be on the use of the Fourier Transform but with the evaluation of the entire frequency spectra, however, WTs will be evaluated also as an alternate to this as presented within [

9,

10], yet this technique will not be the main approach considered.

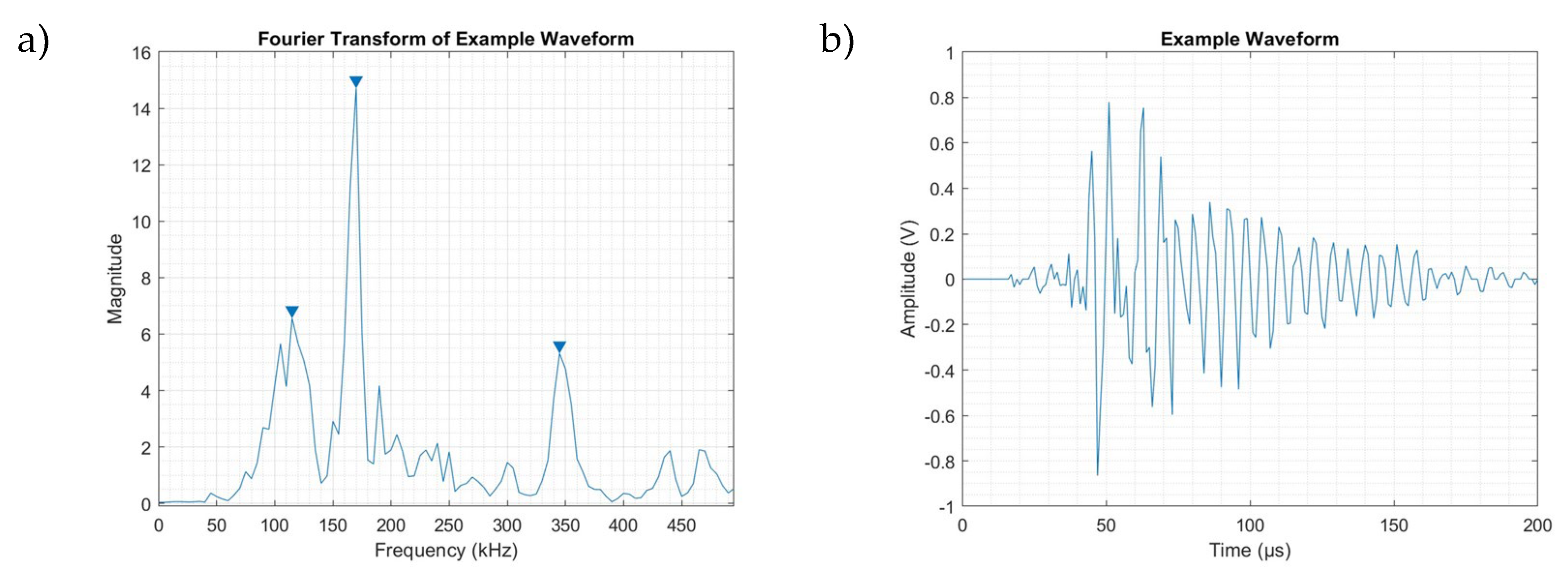

3.2.1. Fourier Transform

The assessment of the peak frequency of a given signal involves the isolation and extraction of damage events. FFT can be applied to transform the data into its frequency domain and extract the peaks of interest, under a set of strict selection parameters to ensure choice of independent peaks of significant value, as detailed in section 2.4. Expansion upon this involves the selection of the maximum number of peaks which are to be extracted for each of the input signals. In the present study 5 peaks were selected in relation to each of the damage modes identifiable. To prevent desynchronisation, as well as for the ease of representation, any inputs which did not yield significant peaks to trigger their acquisition, were filtered out using null values for uniform length of each level.

Figure 4 shows the established selection parameters based on the frequency domain.

Figure 4 also shows the distribution of the signal within the frequency spectrum, allowing for comparison with the result from the WT performed on the same input signal. As it can be seen only three peaks meet the selection criteria established. Thus, these will be recorded in the highest three of the levels, and null values inputted into the lower two.

For the evaluation of the information, as highlighted, proper selection of means of its representation are key. This will allow for distinguishing between the presented levels within the data, as well as the establishment of any trends apparent. To best display this, division of each defined level, separated by their magnitude relative to other peaks within the same event, each into a singular plot. Each of these was further subdivided based upon the frequency ranges established earlier in the investigation using the peak frequency values and k-means clustering, represented by the colouration of a given point.

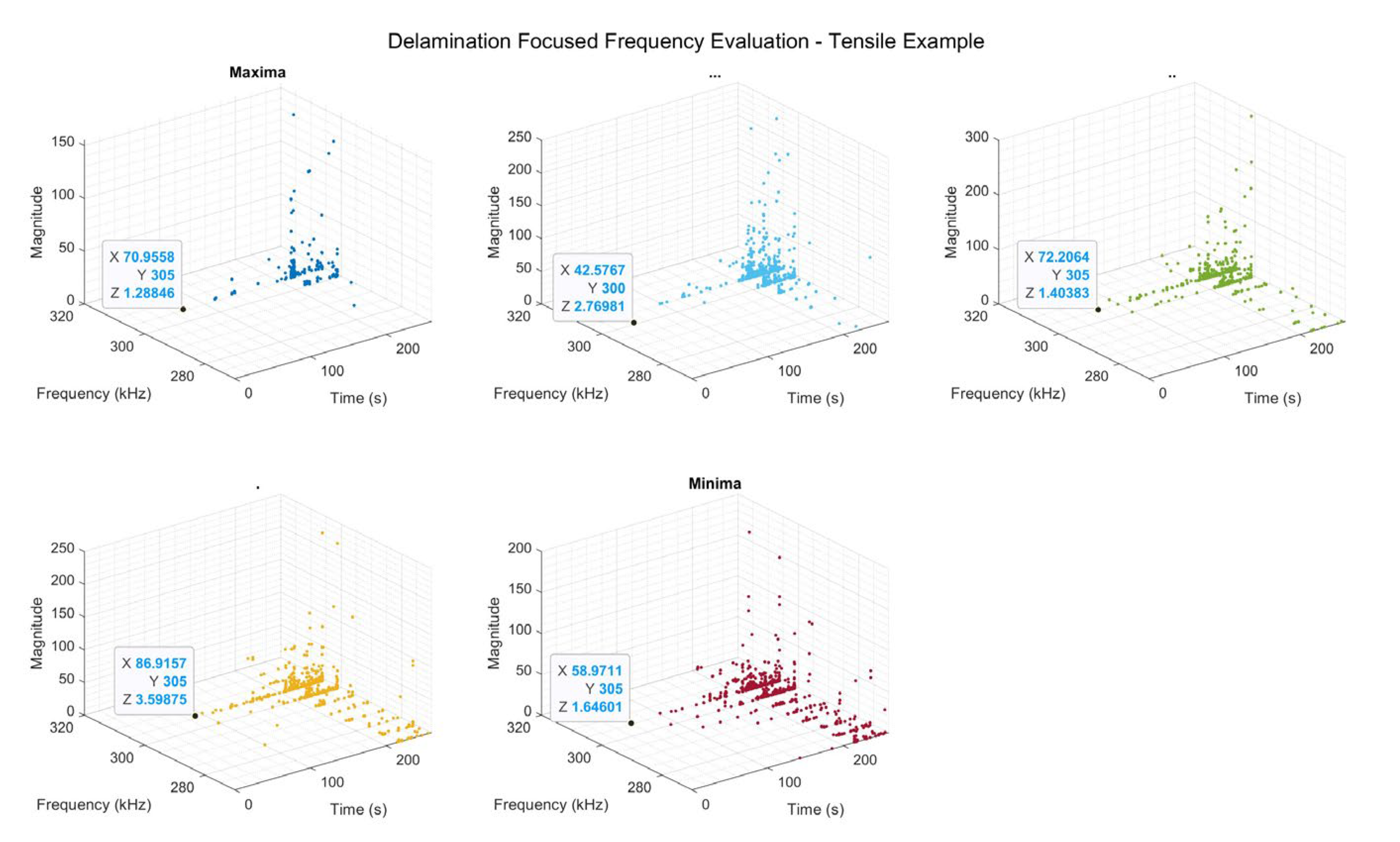

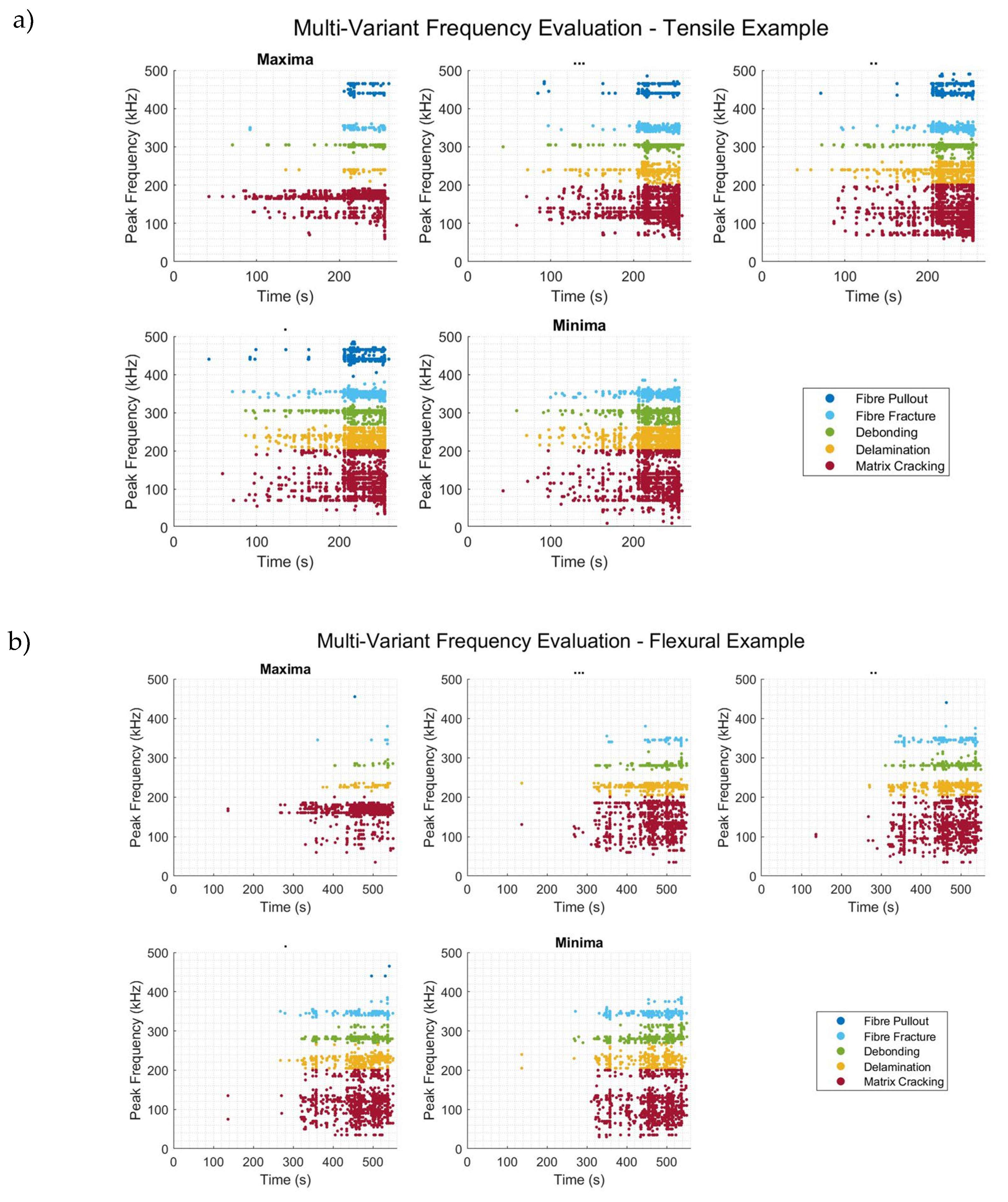

The plots in

Figure 5 show, from left to right, the different intensity levels extracted from the frequency spectra of the damage events identified within the inputted examples. Despite large input data sizes, the operations performed to acquire such data were efficient timewise for the machine used for the processing and experimentation upon the data here; Dell Inspiron 16 7610 (Intel 11th Gen i7-11800H with upgraded 32 GB RAM at 3200 MT/s, up to 14 GB allocated to MATLAB). For tensile test data around 220 million input data points (220 seconds) were evaluated for each sample, yielding around 6000 damage events identified, resulting in a total of 30,000 points overall. In this an elapsed runtime, including the input, formatting, preprocessing, identification and extraction of damage events, application of FFT and extraction of points, is in the range of approximately 14 seconds on average for completion and plotting. For flexural testing, an increase in the length of input was observed, i.e., lengths of 425 to 475 million datapoints (425 to 475 seconds). However, as flexural testing is far less active in terms of the AE response produced, hence an average of 3,000 damage events were observed per test, which combined yield a total of 15,000 points. Despite this, an average elapsed runtime of approximately 18 seconds was observed per test dataset. The dominance in the relationship between the processing time required and the length of the input data is evident, rather than on the number of identified events. The increase in time observed between the two input types generally demonstrates good scalability of the processes described.

3.2.2. Wavelet Transform

WT are used to decompose the input wave into different levels, such that the spectral components can be directly assessed. The means by which this is done is specified through the wavelet type selected for the decomposition itself, with the number of levels being alterable and operator specific. The specifics of this given operation are well explored and developed by Qi, considering both the theoretical and physical implications of their application to AE information of this type [

9].

To assess the spectral content of an input AE event, as discussed by Barile et al., application the in-built functionality of MATLAB applications designed for WT, specifically the Wavelet Signal Analyser and Signal Multiresolution Analyser, are sufficient for providing the spectral energy distribution of given input signal. The application of DWT, is influenced by the wavelet type selected, influencing the information ultimately extracted from the input signal [

9,

10]. As the aim herewith is for these parameters to serve as a source of comparison using a limited sample to reflect previous related work, a full comprehensive review of the best suited wavelet type and level of decomposition is outside of the scope of the present study. Through application of DWT in this manner specific control of frequency ranges contained within each level of a given wavelet decomposition, hence direct overlap between this and the established ranges within section 3.1 is not observed. However, through selection of the correct wavelet type, Haar or Daubechies, and level good overlap can be achieved. From this correlation between information presented on the frequency spectra content though use of WT and Fourier Transform can be seen. For these reasons, as well as more accurate control of the frequency band selection, at least in the method chosen, Empirical Wavelet Transform (EWT) will be used and serve as a point of comparison. Within EWT the decomposition of the signal is performed based on segmentation detected through the frequency spectra of a given input signal, upon which the signal division is based [

20]. However, as this is done sample by sample, it may give rise to variations of the assigned levels dependent on the frequency distribution of the input signal, as well as being overall a less efficient approach than a predetermined DWT due to the additional required processes.

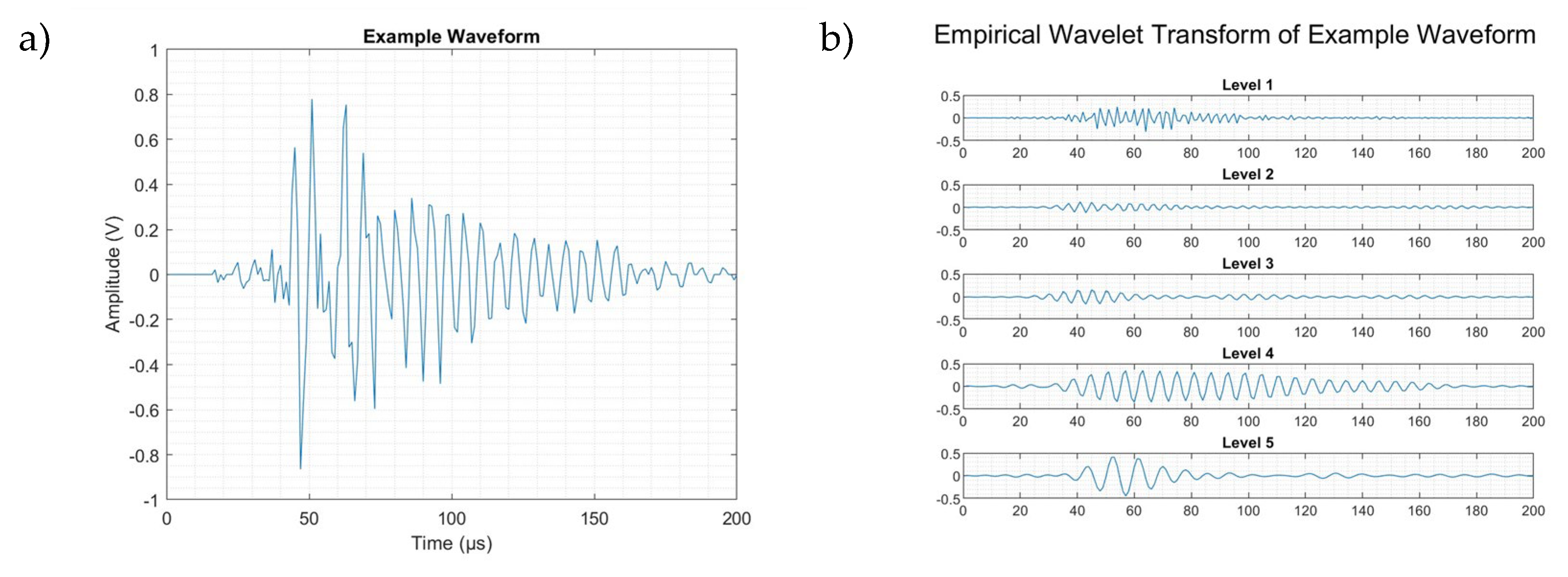

Figure 3 demonstrates the processing associated with the completion of EWT in this manner, with

Figure 3a showing an example input damage waveform, and 3b the wavelet components produced as a result of the performance of EWT. Each of these levels is limited between frequency bands. In turn, like in the cases where DWT is applied, this allows for the evaluation of the spectral energy of a given input signal, the distribution of energy amongst the frequency range. From the above example, it was found that over 75% of the spectral energy was within the range associated with matrix cracking.

4. Discussion

4.1. Method Comparison

The two methods explored in the present study investigate the frequency components of a given input signal in a different manner. The FT-based approach, is a direct expansion of the existing peak frequency assessment approach, in order to include events beyond the dominant damage mode observed. The WT method based on EWT, explores the energy contained within a specified frequency range extracted from a signal by its decomposition. From the example given amongst further direct comparison on the performance of the two methods discussed, using identified damage modes from across the dataset, shows general agreement in the content. What clearly differentiates the two approaches is the manner in which this information is interpreted.

The FFT-based approach gives a direct peak associated with a detected frequency within the damage event, whose magnitude can be evaluated directly. This allows for the tracking of progression of a specific damage mode, through its initiation and propagation based upon the value reflected here, as opposed to a generalised level of a signal which can be attributed to that range. It is not however, certain that the same specific instance of damage can be tracked directly within this environment with the described monitoring setup. Yet, it can provide earlier indications of the occurrence of various damage modes simultaneously, which when considering their interlinked nature in some cases, such as matrix cracking and delamination, may prove particularly useful in the analysis of the health of a structure, as well as the expected lifetime. For example, an early detection of delamination, through detection of its initiation in this way may prevent the associated risks with such a damage site present in a structure, this is further explored within the subsequent section.

For the WT method, explored by Qi and Barile et al., and which is further investigated here, evaluation of the spectral energy, can be used to assess the health of the monitored structure/component during monitoring. The signal content is essential for obtaining a good general approximation of the damage modes that have occurred and the extent that damage has evolved.

4.2. Tracking Damage Propagation

As discussed earlier, the proposed methodology has the ability to detect and quantify the damage events identified. Thus, it can be used as an early warning system for detection and quantification of initiation of a specific damage mode, as well as to evaluate its propagation in service. To best achieve this individual damage mode, and hence associated frequency range can be considered. In this case, delamination has been selected. Moreover, to allow for further interrogation of the events being displayed, a third axis can be introduced within the plots, displaying the magnitude of each of the events, allowing for inter level comparison, as well as the study of the progression of damage in terms of its intensity. To demonstrate the benefit of such an approach, the first instance of delamination observed within each of the levels has been highlighted providing its time, frequency and magnitude information, displayed as X, Y and Z respectively.

Figure 6.

Delamination Focused Damage Assessment Displaying Initial Occurrence.

Figure 6.

Delamination Focused Damage Assessment Displaying Initial Occurrence.

When the acoustic emission frequency content is analysed in this way, the primary benefit becomes apparent, as demonstrated by the occurrence of an event indicative of delamination be detected sooner, at ~42 seconds for level 2, comparative to ~70 seconds for level 1 equivalent to peak frequency assessment. What is also gained through the introduction of the third, magnitude, axis is the overall higher magnitude seen for this event type when comparing the lower levels and level 1 (peak). From this it can be inferred that in the assessment using peak frequency alone, these relatively high magnitude delamination events would be masked by the simultaneous occurrence of a more intense, in terms of signal, damage mode. As matrix cracking generally occurs at lower loading levels, crack growth here would generally be of greater intensity than the initiation of another damage mode within the structure, hence its masking.

5. Conclusions

Damage in FRC materials and structures can initiate and propagate through complex mechanisms. This means damage characterisation and accurate assessment of the severity of damage detected, particularly when using passive monitoring methods, such as AE, poses significant challenges. In the present study, frequency-based analysis has been explored as a means of directly identifying and quantifying specific damage events and their associated modes within FRP materials and structures. The appropriateness of the proposed multi-variant frequency-based analysis approach has been demonstrated. A comparison between the Fast Fourier and Wavelet Transform algorithms employed has been provided with respect to the limitations of methods that have been studied previously.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Matthew Gee and Mayorkinos Papaelias; Data curation, Matthew Gee, Sanaz Roshanmanesh, Farzad Hayati and Mayorkinos Papaelias; Formal analysis, Matthew Gee; Funding acquisition, Mayorkinos Papaelias; Methodology, Mayorkinos Papaelias; Project administration, Mayorkinos Papaelias; Software, Sanaz Roshanmanesh and Farzad Hayati; Supervision, Mayorkinos Papaelias; Validation, Matthew Gee, Sanaz Roshanmanesh and Farzad Hayati; Writing – original draft, Matthew Gee; Writing – review & editing, Mayorkinos Papaelias. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme Carbo4Power project (Grant No.: 953192).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author for any data access requests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the School of Metallurgy and Materials at the University of Birmingham for the provision of testing facilities. The authors would also like to thank AIMEN for the manufacturing and provision of the FRP samples tested during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FRP |

Fibre Reinforced Polymer |

| SHM |

Structural Health Monitoring |

| SCC |

Stress Corrosion Cracking |

| NDT |

Non-Destructive Testing |

| UT |

Ultrasonic Testing |

| WTB |

Wind Turbine Blades |

| CM |

Condition Monitoring |

| AE |

Acoustic Emission |

| DSP |

Digital Signal Processing |

| RMS |

Root Mean Square |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier Transform |

| WT |

Wavelet Transform |

| DWT |

Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| CFRP |

Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer |

| QRS |

Quantum Resonance Sensor |

| EWT |

Empirical Wavelet Transform |

References

- Qureshi, J. A Review of Fibre Reinforced Polymer Structures. Fibers 2022, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, C.; Pastor, M.-L.; Eyma, F.; Lorrain, B. The Detection of Aeronautical Defects in Situ on Composite Structures Using Non Destructive Testing. Compos. Struct. 2011, 93, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussiba, A.; Kupiec, M.; Ifergane, S.; Piat, R.; Bohlke, T. Damage Evolution and Fracture Events Sequence in Various Composites by Acoustic Emission Technique. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, S0266353807003430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Guo, F.; Cheng, J. Study on Delamination Damage of CFRP Laminates Based on Acoustic Emission and Micro Visualization. Materials 2022, 15, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, P.J.; Wijnen, P.A.M.; Janssen, R.B.F. Real-Time Frequency Determination of Acoustic Emission for Different Fracture Mechanisms in Carbon/Epoxy Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1995, 55, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.L. Ultrasonic Guided Waves in Solid Media, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2014; ISBN 978-1-107-04895-9. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.; Ye, L. Identification of Damage Using Lamb Waves; Lecture Notes in Applied and Computational Mechanics; Springer London: London, 2009; Vol. 48, ISBN 978-1-84882-783-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fotouhi, M.; Najafabadi, M.A. Acoustic Emission-Based Study to Characterize the Initiation of Delamination in Composite Materials. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2016, 29, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G. Wavelet-Based AE Characterization of Composite Materials. NDT E Int. 2000, 33, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, C.; Casavola, C.; Pappalettera, G.; Paramsamy Kannan, V. Acoustic Emission Waveforms for Damage Monitoring in Composite Materials: Shifting in Spectral Density, Entropy and Wavelet Packet Transform. Struct. Health Monit. 2022, 21, 1768–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Acoustics Corporation; MISTRAS Group Inc R50-Alpha 2010.

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-Means Clustering Algorithms: A Comprehensive Review, Variants Analysis, and Advances in the Era of Big Data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, N.; Wang, P.H. A Review of Failure Modes and Fracture Analysis of Aircraft Composite Materials. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 115, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebière, J.-L. The Initiation of Transverse Matrix Cracking and Longitudinal Matrix Cracking in Composite Cross-Ply Laminates: Analysis of a Damage Criterion. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1175060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, E. Fibre-Dominated Failures of Polymer Composites. In Failure Analysis and Fractography of Polymer Composites; Elsevier, 2009; pp. 107–163. ISBN 978-1-84569-217-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rebière, J.-L. Matrix Cracking and Delamination Evolution in Composite Cross-Ply Laminates. Cogent Eng. 2014, 1, 943547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkin, R.; Green, C.J.; Vangrattanachai, S.; Pinho, S.T.; Robinson, P.; Curtis, P.T. On Acoustic Emission for Failure Investigation in CFRP: Pattern Recognition and Peak Frequency Analyses. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2011, 25, 1393–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedifar, M.; Zarouchas, D. Damage Characterization of Laminated Composites Using Acoustic Emission: A Review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 195, 108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, S.F.; Beganovic, N.; Söffker, D. Investigation of Damage Detectability in Composites Using Frequency-Based Classification of Acoustic Emission Measurements. Struct. Health Monit. 2019, 18, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, W. Recent Advancements in Empirical Wavelet Transform and Its Applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 103770–103780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).