1. Introduction

Sarcopenia is a syndrome characterized by the progressive, age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function [

1,

2]. Its prevalence increases significantly with age, impacting a substantial portion of the elderly population [

3]. Furthermore, sarcopenia is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including functional decline, increased risk of falls and fractures, and higher mortality rates, highlighting its significance as a public health concern [

2,

4]. Muscle mass is regulated by a delicate balance between muscle protein synthesis (anabolism) and muscle protein breakdown (catabolism). Sarcopenia and muscle atrophy resulting from various causes occur when this balance shifts towards excessive breakdown [

5].

A major mechanism underlying muscle atrophy is the activation of protein degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). Playing pivotal roles in this pathway are the muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases, MAFbx (muscle atrophy F-box, also known as Atrogin-1) and MuRF1 (muscle RING finger 1) [

6,

7]. The expression of these genes is regulated by various upstream signaling pathways. Notably, the Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1)/Akt pathway promotes muscle growth and inhibits protein breakdown. IGF-1/Akt signaling suppresses the transcription of MAFbx and MuRF1 by phosphorylating Forkhead box O (FOXO) family transcription factors (mainly FoxO1 and FoxO3), retaining them in the cytoplasm [

8]. Conversely, under atrophic conditions such as starvation, immobilization, inflammation, or excess glucocorticoids, Akt activity is reduced. This allows dephosphorylated FOXO proteins to translocate into the nucleus, where they increase the expression of MAFbx and MuRF1, thereby promoting protein degradation [

9]. Additionally, activation of the energy sensor AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) can also influence protein breakdown pathways [

10].

Stigmasterol is a phytosterol (plant sterol) found in various plant sources, including soybeans, nuts, seeds, and several vegetable oils [

11,

12]. It has been reported to possess diverse biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, cholesterol-lowering, and anti-osteoarthritic effects [

13,

14]. Structurally, stigmasterol is very similar to β-sitosterol, differing primarily by an additional double bond in the side chain. While β-sitosterol has demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and the ability to modulate muscle protein homeostasis by reducing markers of muscle atrophy, such as MuRF1 and MAFbx, and improving grip strength and myofiber thickness in animal models [

15]. On the other hand, stigmasterol has been studied for its anti-inflammatory and metabolic benefits, including lipid metabolism regulation and bile acid modulation [

16,

17]. However, no studies have directly linked stigmasterol to muscle mass regulation or function.

Synthetic glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone, are widely used for treating inflammatory conditions but can cause severe muscle atrophy as a side effect, particularly with long-term or high-dose use [

18]. Glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy is primarily mediated by increased protein breakdown, specifically through the upregulation of MAFbx and MuRF1 expression via FoxO transcription factors [

18]. Despite the various known bioactivities of stigmasterol, its specific impact on muscle mass loss and functional decline, especially under conditions inducing atrophy like glucocorticoid treatment, remains poorly understood. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on its mechanism of action concerning the regulation of muscle protein breakdown pathways.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the potential protective effects of stigmasterol against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy using both in vitro (C2C12 myotubes) and in vivo (mouse) models. We specifically sought to elucidate the underlying mechanism by examining the impact of stigmasterol on the FoxO3-mediated ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway, focusing on the regulation of MuRF1 and MAFbx expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Stigmasterol (Cat. No. S0088) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan), and dexamethasone (Dexa) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), horse serum (HS), penicillin-streptomycin, and trypsin-EDTA were obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The following primary antibodies were used: MuRF-1 (Cat# sc-398608; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), MAFbx (Cat# sc-166806; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FoxO3 (Cat# 2497; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and β-actin (Cat# A5441; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were also used. Giemsa and May-Grunwald staining solutions were sourced from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and obtained from standard commercial suppliers.

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.2.1. Cell Maintenence and Differentiation

C2C12 mouse myoblast cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO₂ atmosphere. For differentiation into myotubes, cells were grown to 80% confluence and then switched to differentiation medium (DMEM with 2% HS) for 5 days, with the medium changed every 48 h.

2.2.2. Dose-Response Study

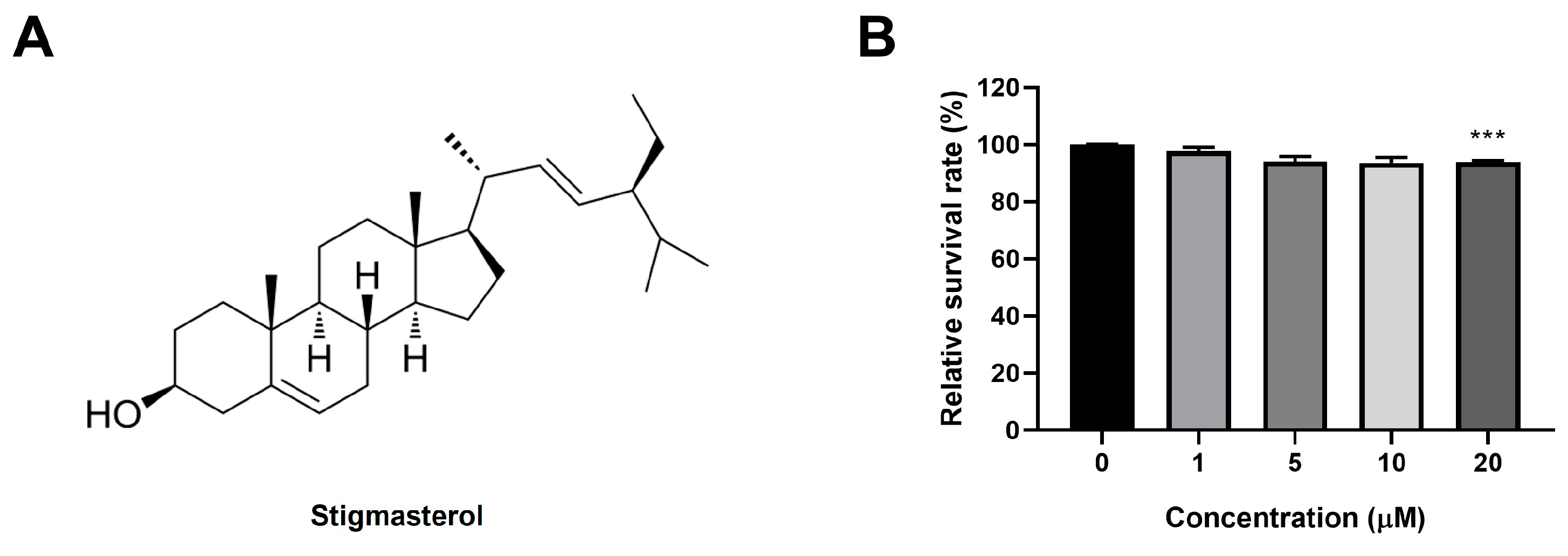

To assess the effect of stigmasterol on C2C12 myoblast viability, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 10³ cells/well and treated with stigmasterol at concentrations of 0, 1, 5, 10, and 20 μM for 24 h. Subsequently, each well was treated following the protocol provided with the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). Specifically, 10 µL of the CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. The absorbance at 450 nm, corresponding to the amount of formazan produced by cellular dehydrogenases, was then measured using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Data were expressed as a percentage of the untreated control.

2.2.3. Dexamethasone-Induced Atrophy and Stigmasterol Treatment

Differentiated C2C12 myotubes were divided into four groups: (1) Control (CTL), treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO); (2) Dexa, treated with 50 μM dexamethasone; (3) Stigmasterol (S), treated with 10 μM stigmasterol; and (4) Dexa + Stigmasterol (DS), treated with 50 μM dexamethasone and 10 μM stigmasterol. Treatments were applied for 24 h. The concentration of stigmasterol (10 μM) was selected based on the dose-response study (

Figure 1B), which showed mild significant toxicity at this level.

2.2.4. Giemsa and May-Grunwald Staining

Myotubes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, stained with Giemsa and May-Grunwald solutions according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were acquired from four randomly selected fields of the stained cells using a camera-equipped microscope (Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Using NIS Elements software (NIS-Elements Advanced Research, Melville, NY, USA), myotubes within each field were randomly selected to measure their diameter.

2.2.4. Fusion Index Quantification

Myotubes were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to visualize nuclei. The fusion index was calculated as the percentage of nuclei within multinucleated myotubes (containing ≥3 nuclei) relative to the total number of nuclei, as described previously [

19]. At least 10 fields per group were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Western Blot Analysis

C2C12 myotubes and mouse muscle tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to NC membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 hour at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against MuRF1 (1:1000), MAFbx (1:1000), FoxO3 (1:1000), and β-actin (1:5000). After washing with TBST, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using the Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA) and quantified by densitometry using the ChemiDocTM Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc). Expression levels were normalized to β-actin as a loading control.

2.4. Animal Model and Experimental Design

2.4.1. Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice with an average body weight of 22 g (6 weeks old) were obtained from Core Tech Co., Ltd., (Seoul, Korea) and housed under controlled conditions (22 ± 2°C, 12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Gyeongsang National University (GNU-230719-M0156-01), in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.4.2. Induction of Muscle Atrophy and Treatment

Mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 8 per group): (1) Control (CTL), receiving vehicle (saline with 0.1% DMSO); (2) Dexa, receiving 20 mg/kg/day dexamethasone i.p. and 3 mg/kg/day stigmasterol by oral administration. Treatments were administered daily for 21 days. The dose of dexamethasone was selected based on its established ability to induce muscle atrophy in mice [

18]. The stigmasterol dose (3 mg/kg/day) was determined based on preliminary studies indicating that this dosage demonstrated efficacy against muscle atrophy indicators while showing no apparent toxicity in the mouse model.

2.4.3. Body Weight and Muscle Mass Measurements

Body weight was recorded weekly throughout the 21-day experimental period. At the end of the experiment, mice were euthanized by CO₂ inhalation, and the gastrocnemius (GA), tibialis anterior (TA), and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles were dissected and weighed immediately to assess muscle mass.

2.4.4. Bone Mineral Density (BMD) Measurement

BMD was measured using a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanner (OsteoSys, Seoul, Korea). Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane during the procedure, and BMD was calculated for the whole body excluding the head.

2.4.5. Immunofluorescence and Cross-Sectional Area (CSA) Analysis

GA and TA muscles were harvested, embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA), and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Transverse sections (5 μm) were cut using a cryostat (Leica CM1950; Heidelberg, Germany) and stained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (W11261; Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to visualize muscle fiber boundaries. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse ni DSRi2; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) at 20× magnification. Fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) was quantified using MyoVision (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA) by measuring at least 200 fibers per muscle per mouse [

20].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments (for in vitro studies) and as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from eight mice per group (for in vivo studies). Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple group comparisons. For the body weight time course, two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

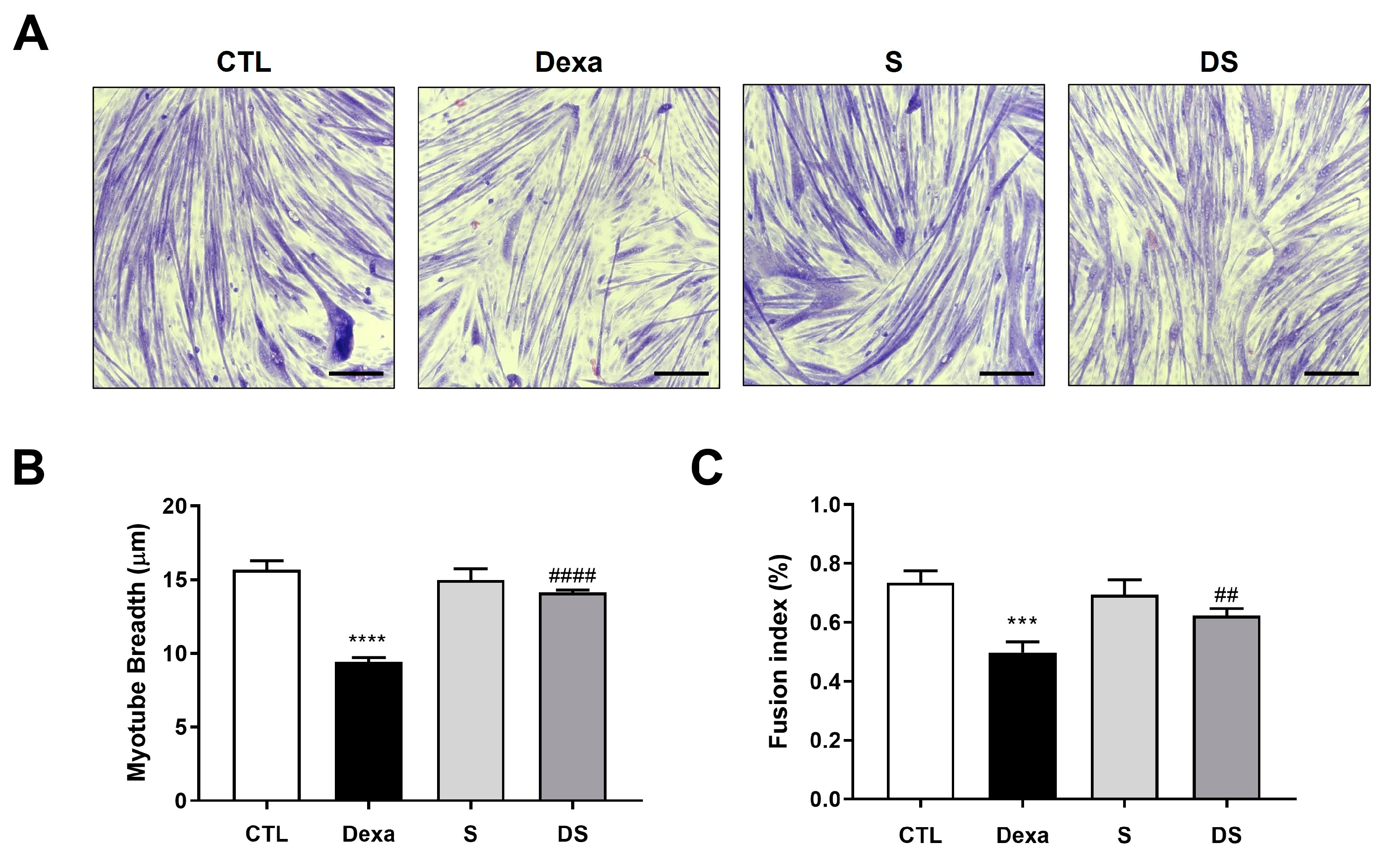

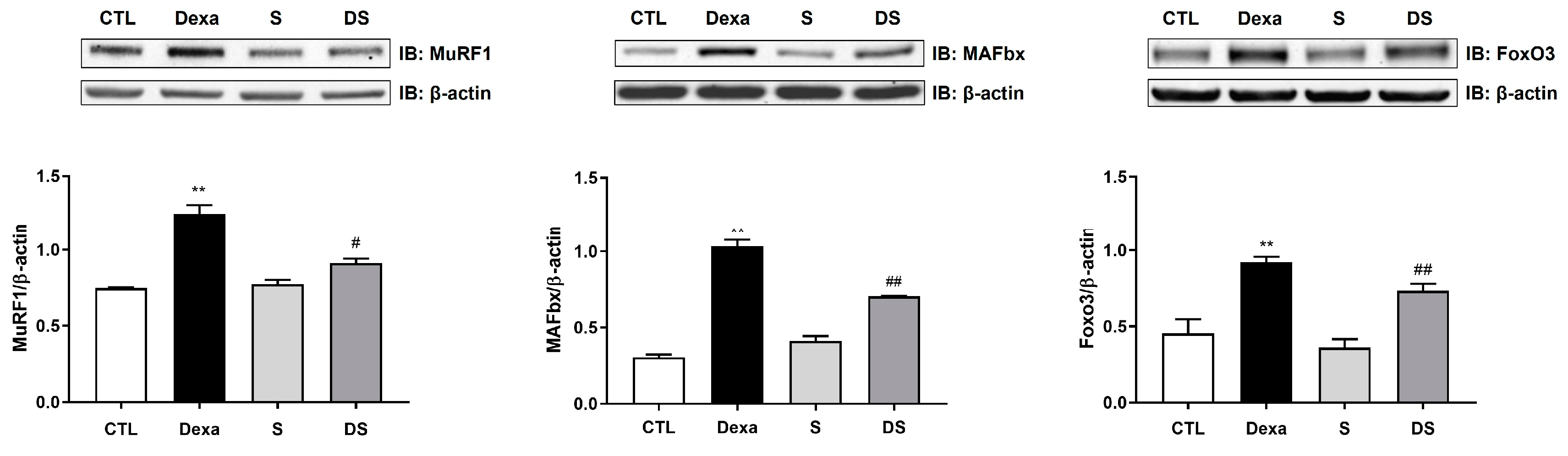

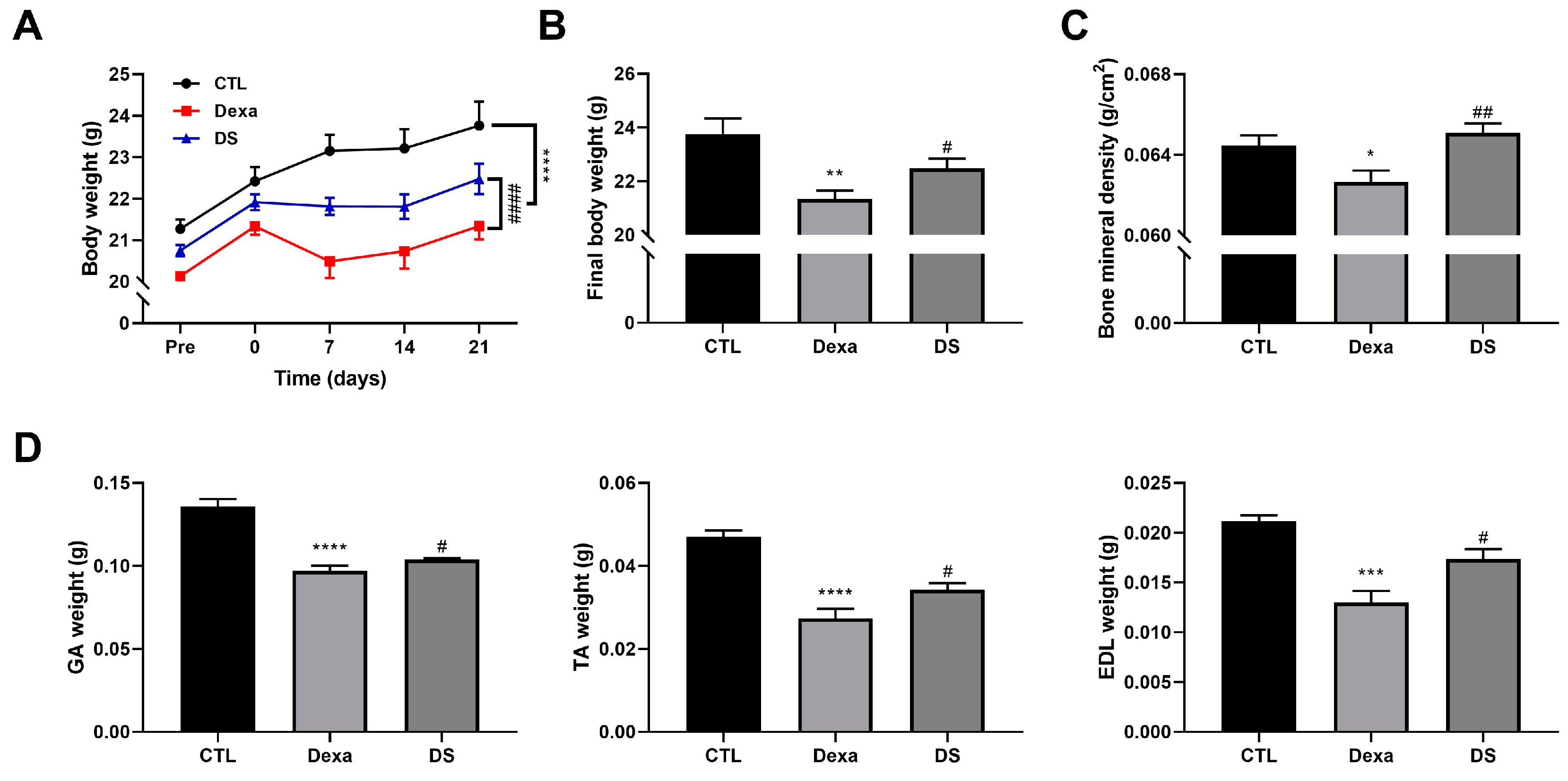

This study demonstrates that Stigmasterol, a naturally occurring phytosterol, exerts significant protective effects against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy both in vitro in C2C12 myotubes and in vivo in a mouse model. The key findings indicate that Stigmasterol treatment ameliorates the loss of myotube size and fusion (

Figure 2), prevents reductions in body weight and skeletal muscle mass (

Figure 4), and preserves muscle fiber cross-sectional area (

Figure 5) in the context of dexamethasone exposure. Mechanistically, these protective effects are strongly associated with the downregulation of the critical ubiquitin-proteasome system components, specifically the E3 ubiquitin ligases MuRF1 and MAFbx, and their upstream transcriptional regulator, FoxO3 (

Figure 3,

Figure 6).

The observed mitigation of dexamethasone-induced atrophy by Stigmasterol highlights its potential to counteract excessive muscle protein breakdown. Glucocorticoids like dexamethasone are well-established inducers of muscle wasting, primarily by enhancing protein catabolism through the activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system [

18]. Central to this process is the activation of Forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factors, which drive the expression of MuRF1 and MAFbx [

6,

8,

9]. The FOXO signaling pathway is recognized as playing a crucial role in the pathogenesis of skeletal muscle atrophy [

21]. Our in vitro results showed that dexamethasone treatment robustly increased FoxO3, MuRF1, and MAFbx expression in C2C12 cells (

Figure 3), confirming the activation of this catabolic pathway. In vivo, dexamethasone also significantly upregulated FoxO3 and MAFbx protein levels in mouse skeletal muscle (

Figure 6). However, under our experimental conditions, dexamethasone treatment did not result in a significant increase in MuRF1 protein expression in vivo (

Figure 6). This discrepancy might reflect the complexities of the in vivo environment, potential time-dependent regulation, or differential sensitivity of MuRF1 versus MAFbx regulation in this specific model. Indeed, studies using knockout mice have shown functional divergence between MuRF1 and MAFbx in response to glucocorticoids in vivo, suggesting their roles are not entirely redundant in this context [

22]. Furthermore, the regulation of these atrogenes can be influenced by other factors such as genetic background, potentially leading to varied responses [

23]. Crucially, stigmasterol co-treatment significantly attenuated the dexamethasone-induced upregulation of FoxO3 and MAFbx in vivo (

Figure 6). While MuRF1 protein expression was suppressed by stigmasterol in vitro (

Figure 3), its expression was not significantly increased by dexamethasone treatment in vivo under our experimental conditions (

Figure 6), differing from the in vitro findings. This highlights MAFbx as a key downstream target modulated by stigmasterol in vivo in this model. The divergence between MuRF1 protein levels in vitro and in vivo could stem from the complex systemic environment, differing time-course responses, or specific regulatory mechanisms prevailing in vivo under 21-day dexamethasone exposure. Although functional studies like Baehr et al. demonstrated the necessity of MuRF1 for the full atrophic response using knockout mice [

22], our protein expression data at this time point most strongly link stigmasterol’s protective effect in vivo to the attenuation of the FoxO3-MAFbx axis. Therefore, our findings provide a direct molecular mechanism for stigmasterol’s muscle-protective effects – primarily involving the suppression of the FoxO3-MAFbx signaling axis in vivo, as depicted in our proposed mechanism (

Figure 7). The concordance between our in vitro findings for FoxO3 and MAFbx (

Figure 3) and the corresponding in vivo findings (

Figure 6) strengthens the validity of this aspect of the conclusion.

Stigmasterol belongs to the phytosterol family, plant-derived compounds known for various bioactivities [

11,

24]. It shares structural similarity with β-sitosterol [

24,

25]. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that β-sitosterol also attenuates dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in vitro and in vivo, with evidence suggesting involvement of FoxO signaling regulation [

15]. The current study highlights the modulation of FoxO3 by stigmasterol in mitigating dexamethasone effects. While both structurally similar phytosterols appear protective and converge on modulating FoxO transcription factors, further investigation is warranted to fully elucidate the specificities and potential overlap in their regulation of different FoxO isoforms (including FoxO1 and FoxO3) in the context of muscle atrophy. Beyond direct modulation of atrophy signaling, Stigmasterol possesses known anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [

13,

26]. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress contribute significantly to muscle wasting pathologies, including glucocorticoid-induced myopathy. Stigmasterol’s anti-inflammatory effects, potentially mediated via NF-κB inhibition [

13], and its antioxidant actions could create a more favorable environment for muscle preservation, complementing its effects on the FoxO pathway [

11].

The precise mechanism by which Stigmasterol inhibits FoxO3 activation or expression requires further elucidation. Glucocorticoids can suppress the pro-survival Akt signaling pathway, which normally phosphorylates and inhibits FoxO transcription factors [

9,

27]. It is plausible that Stigmasterol may counteract Dexa’s effect on Akt or act downstream or parallel to it to reduce FoxO3 activity. Our study focused on the key catabolic regulators identified; however, exploring the effects of Stigmasterol on upstream kinases like Akt or other relevant pathways (e.g., AMPK, protein synthesis pathways like mTOR) would provide a more comprehensive mechanistic picture.

This study possesses several strengths, including the consistent demonstration of Stigmasterol’s efficacy in both cell culture (

Figures 2, 3) and animal models (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), coupled with the investigation of a specific, relevant molecular mechanism (

Figures 3, 6, 7). However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The findings are currently limited to the dexamethasone-induced atrophy model, a specific form of toxic myopathy [

12]; its applicability to other prevalent conditions like age-related sarcopenia or disuse atrophy remains to be determined. Furthermore, while muscle mass and fiber size were preserved (

Figure 4,

Figure 5), direct assessments of muscle function (e.g., strength, endurance) were not included. Evaluating functional outcomes is critical for establishing physiological relevance. Additionally, our mechanistic focus was on protein catabolism via the FoxO3 axis; potential effects on protein synthesis pathways were not investigated. Finally, further studies are needed to determine the optimal dosage, administration route, and long-term bioavailability and safety of Stigmasterol for muscle protection in vivo. Moreover, the in vivo study did not include a group treated with stigmasterol alone; while preliminary studies suggested minimal independent effects of stigmasterol at the tested dose, the inclusion of this group would have allowed for a direct assessment of its baseline effects.

Despite these limitations, the results carry potentially significant implications. Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy remains a challenging clinical problem [

28]. Our findings identify Stigmasterol as a potential therapeutic candidate derived from natural sources that could be explored to mitigate this adverse effect. Given the increasing interest in nutritional interventions for muscle health, particularly concerning sarcopenia which affects functionality and quality of life in the elderly [

29], Stigmasterol could also hold promise as a nutraceutical ingredient, although specific studies in aging models are needed.

Future research should focus on addressing the current study’s limitations. Testing Stigmasterol’s efficacy in models of sarcopenia and disuse atrophy, incorporating comprehensive muscle function tests, is paramount. Mechanistic studies should expand to include upstream signaling pathways (e.g., Akt/mTOR) regulating both protein synthesis and degradation. Investigating potential synergistic effects with exercise or other nutritional compounds could also yield valuable insights. Finally, detailed pharmacokinetic, dose-optimization, and long-term safety studies are essential before considering any potential clinical translation.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of stigmasterol and its effect on C2C12 myoblast viability. (A) Chemical structure of stigmasterol, a plant-derived sterol used in this study. (B) Dose-response effect of stigmasterol on C2C12 myoblast viability. Cells were treated with stigmasterol at concentrations of 0, 1, 5, 10, and 20 μM for 24 h, and cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments (n = 4). Statistical significance compared to the control (0 μM) is indicated as follows: *** p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of stigmasterol and its effect on C2C12 myoblast viability. (A) Chemical structure of stigmasterol, a plant-derived sterol used in this study. (B) Dose-response effect of stigmasterol on C2C12 myoblast viability. Cells were treated with stigmasterol at concentrations of 0, 1, 5, 10, and 20 μM for 24 h, and cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments (n = 4). Statistical significance compared to the control (0 μM) is indicated as follows: *** p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test).

Figure 2.

Stigmasterol attenuates dexamethasone-induced atrophy in C2C12 myotubes. (A) Representative images of C2C12 myotubes stained with Giemsa and May-Grunwald to assess morphological changes. Myotubes were treated for 24 h under the following conditions: control (CTL, vehicle), dexamethasone (Dexa, 50 μM), stigmasterol (S, 10 μM), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 50 μM Dexa + 10 μM S). Scale bar: 250 μm. (B) Quantification of myotube diameter in the four treatment groups. (C) Fusion index, calculated as the percentage of nuclei in multinucleated myotubes (≥3 nuclei) relative to the total number of nuclei, reflecting myoblast differentiation and fusion. Data in (B) and (C) are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 4). Statistical significance is indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001 vs. CTL; ## p < 0.01, #### p < 0.0001 vs. Dexa (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol.

Figure 2.

Stigmasterol attenuates dexamethasone-induced atrophy in C2C12 myotubes. (A) Representative images of C2C12 myotubes stained with Giemsa and May-Grunwald to assess morphological changes. Myotubes were treated for 24 h under the following conditions: control (CTL, vehicle), dexamethasone (Dexa, 50 μM), stigmasterol (S, 10 μM), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 50 μM Dexa + 10 μM S). Scale bar: 250 μm. (B) Quantification of myotube diameter in the four treatment groups. (C) Fusion index, calculated as the percentage of nuclei in multinucleated myotubes (≥3 nuclei) relative to the total number of nuclei, reflecting myoblast differentiation and fusion. Data in (B) and (C) are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 4). Statistical significance is indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001 vs. CTL; ## p < 0.01, #### p < 0.0001 vs. Dexa (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol.

Figure 3.

Stigmasterol suppresses the FoxO3-MuRF1-MAFbx signaling pathway in dexamethasone-treated C2C12 myotubes. (Upper panel) Western blot analysis of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 protein expression in C2C12 myotubes treated for 24 h under the following conditions: control (CTL, vehicle), dexamethasone (Dexa, 50 μM), stigmasterol (S, 10 μM), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 50 μM Dexa + 10 μM S). β-actin was used as a loading control. (Lower panel) Densitometric quantification of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 expression levels, normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ** p < 0.01 vs. CTL; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 vs. Dexa (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; IB, immunoblot.

Figure 3.

Stigmasterol suppresses the FoxO3-MuRF1-MAFbx signaling pathway in dexamethasone-treated C2C12 myotubes. (Upper panel) Western blot analysis of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 protein expression in C2C12 myotubes treated for 24 h under the following conditions: control (CTL, vehicle), dexamethasone (Dexa, 50 μM), stigmasterol (S, 10 μM), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 50 μM Dexa + 10 μM S). β-actin was used as a loading control. (Lower panel) Densitometric quantification of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 expression levels, normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ** p < 0.01 vs. CTL; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 vs. Dexa (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; IB, immunoblot.

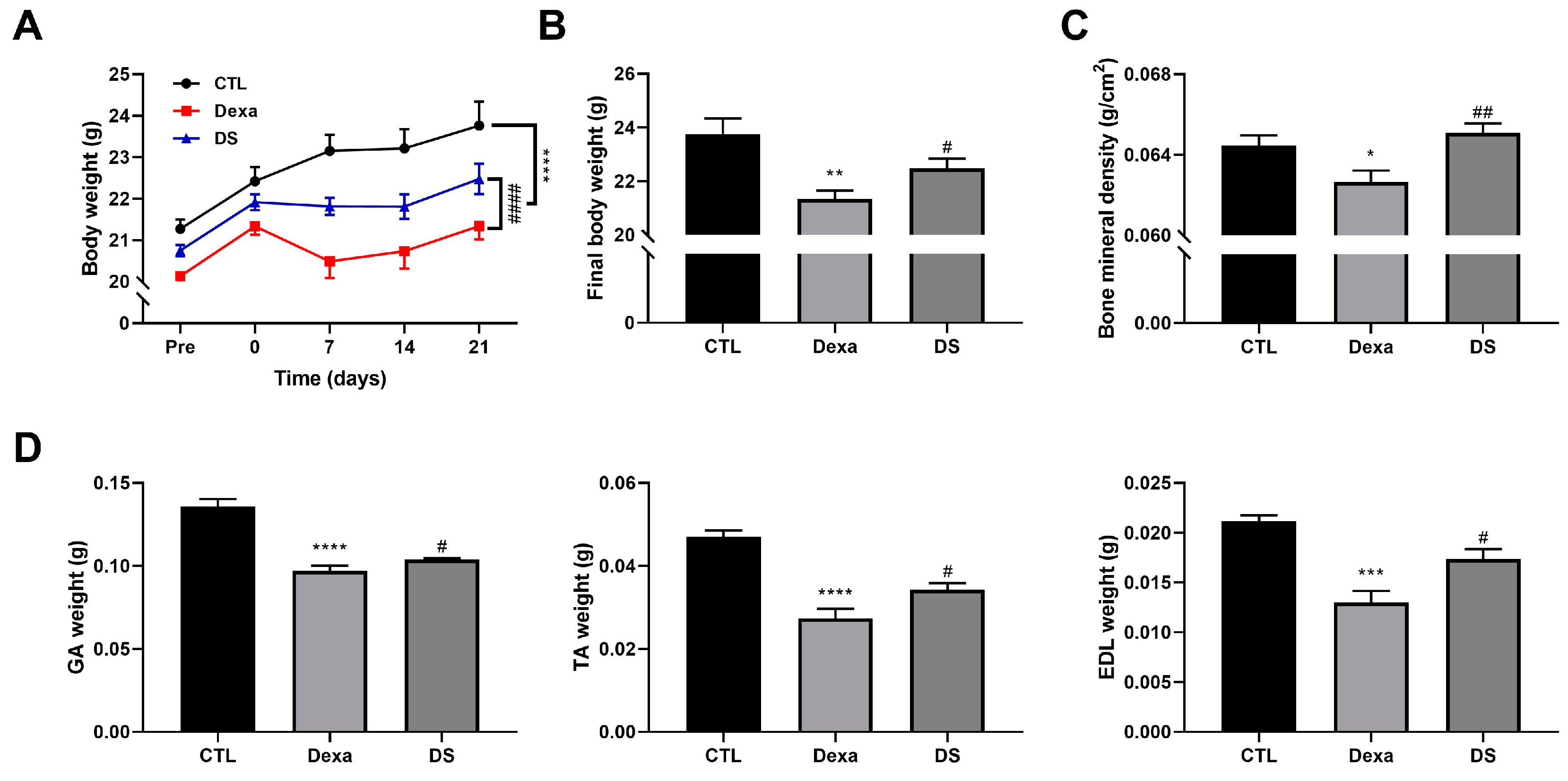

Figure 4.

Stigmasterol ameliorates dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in mice. (A) Body weight changes over 21 days in mice treated with vehicle (CTL), dexamethasone (Dexa, 20 mg/kg/day), stigmasterol (S, 3 mg/kg/day), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 20 mg/kg/day Dexa + 3 mg/kg/day S). (B) Final body weight at day 21. (C) Bone mineral density (BMD) measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). (D) Muscle mass of the gastrocnemius (GA), tibialis anterior (TA), and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles at day 21. Data in (A) to (D) are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 8 mice per group). Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. CTL; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 vs. Dexa (two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for A; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for B–D). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; GA, gastrocnemius; TA, tibialis anterior; EDL, extensor digitorum longus.

Figure 4.

Stigmasterol ameliorates dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in mice. (A) Body weight changes over 21 days in mice treated with vehicle (CTL), dexamethasone (Dexa, 20 mg/kg/day), stigmasterol (S, 3 mg/kg/day), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 20 mg/kg/day Dexa + 3 mg/kg/day S). (B) Final body weight at day 21. (C) Bone mineral density (BMD) measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). (D) Muscle mass of the gastrocnemius (GA), tibialis anterior (TA), and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles at day 21. Data in (A) to (D) are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 8 mice per group). Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. CTL; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 vs. Dexa (two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for A; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for B–D). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; GA, gastrocnemius; TA, tibialis anterior; EDL, extensor digitorum longus.

Figure 5.

Stigmasterol preserves muscle fiber cross-sectional area in dexamethasone-treated mice. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of gastrocnemius (GA) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscle cross-sections stained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) to visualize fiber boundaries. Mice were treated for 21 days with vehicle (CTL), dexamethasone (Dexa, 20 mg/kg/day), stigmasterol (S, 3 mg/kg/day), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 20 mg/kg/day Dexa + 3 mg/kg/day S). Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Histogram distribution of fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) in GA and TA muscles, showing the percentage of fibers within specified CSA ranges. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8 mice per group). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; GA, gastrocnemius; TA, tibialis anterior.

Figure 5.

Stigmasterol preserves muscle fiber cross-sectional area in dexamethasone-treated mice. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of gastrocnemius (GA) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscle cross-sections stained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) to visualize fiber boundaries. Mice were treated for 21 days with vehicle (CTL), dexamethasone (Dexa, 20 mg/kg/day), stigmasterol (S, 3 mg/kg/day), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 20 mg/kg/day Dexa + 3 mg/kg/day S). Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Histogram distribution of fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) in GA and TA muscles, showing the percentage of fibers within specified CSA ranges. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8 mice per group). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; GA, gastrocnemius; TA, tibialis anterior.

Figure 6.

Stigmasterol reduces expression of atrophy-related proteins in mouse muscle tissues. (A) Western blot analysis of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 protein expression in gastrocnemius (GA) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles from mice treated for 21 days with vehicle (CTL), dexamethasone (Dexa, 20 mg/kg/day), stigmasterol (S, 3 mg/kg/day), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 20 mg/kg/day Dexa + 3 mg/kg/day S). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometric quantification of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 expression levels, normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8 mice per group). Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. CTL; # p < 0.05 vs. Dexa (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; GA, gastrocnemius; TA, tibialis anterior; IB, immunoblot.

Figure 6.

Stigmasterol reduces expression of atrophy-related proteins in mouse muscle tissues. (A) Western blot analysis of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 protein expression in gastrocnemius (GA) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles from mice treated for 21 days with vehicle (CTL), dexamethasone (Dexa, 20 mg/kg/day), stigmasterol (S, 3 mg/kg/day), or a combination of dexamethasone and stigmasterol (DS, 20 mg/kg/day Dexa + 3 mg/kg/day S). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometric quantification of MuRF1, MAFbx, and FoxO3 expression levels, normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8 mice per group). Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. CTL; # p < 0.05 vs. Dexa (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). CTL, control; Dexa, dexamethasone; S, stigmasterol; DS, Dexa + stigmasterol; GA, gastrocnemius; TA, tibialis anterior; IB, immunoblot.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanism for the protective effect of Stigmasterol against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy. Schematic diagram illustrating the hypothesized mechanism. Stigmasterol is proposed to inhibit the activation or nuclear translocation of the transcription factor FoxO3 induced by dexamethasone. This leads to reduced transcription and expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase MAFbx, a key component of the ubiquitin-proteasome system consistently downregulated by stigmasterol in vivo in this study. While MuRF1 was also downregulated in vitro, its in vivo protein expression was not significantly increased by dexamethasone or reduced by stigmasterol under these conditions. Consequently, the downregulation of the FoxO3-MAFbx axis contributes significantly to decreased muscle protein degradation, thereby ameliorating muscle atrophy induced by dexamethasone.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanism for the protective effect of Stigmasterol against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy. Schematic diagram illustrating the hypothesized mechanism. Stigmasterol is proposed to inhibit the activation or nuclear translocation of the transcription factor FoxO3 induced by dexamethasone. This leads to reduced transcription and expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase MAFbx, a key component of the ubiquitin-proteasome system consistently downregulated by stigmasterol in vivo in this study. While MuRF1 was also downregulated in vitro, its in vivo protein expression was not significantly increased by dexamethasone or reduced by stigmasterol under these conditions. Consequently, the downregulation of the FoxO3-MAFbx axis contributes significantly to decreased muscle protein degradation, thereby ameliorating muscle atrophy induced by dexamethasone.