1. Introduction

With increasing global competitiveness and deep technological change, Industry 4.0 adoption became a prerequisite for small- and medium-sized firms (SMEs) in such industries, as the ones providing customized mechanic products, that are historically low in digital maturity. Even as they are known to be responsive and specialized, SMEs are held back by outdated technology, decentralized activities, and a low familiarity with technology such as IoT, AI, and data analysis (Garzoni et al., 2020). These limitations are strongest in structurally deprived regions, such as the case of Southern Italy, as infrastructure shortages limit the diffusion of new technology (Battistoni et al., 2023). On the experience of Tecnomulipast S.r.l., a Gravina in Puglia manufacturing SME that, in a technologically under-equipped environment, initiated an Industry 4.0 revolution, the study here explores how IoT-based systems, intelligent automation, and responsive data analysis architecture spur the digitalization with manager-led successor innovation. Closing a literature gap that is particularly regional- or large-firm-centric, the study provides a place-specific, transferable model to underperforming setting SMEs (Filieri et al., 2025). Placing the analysis in the paradigms of regional policy (e.g., Titolo II - Capo II PIA), the study makes the point that the integration of technical and manager-led innovation can stimulate competitiveness and robustness even in poor-resource environments.

2. Company Profile: Tecnomulipast

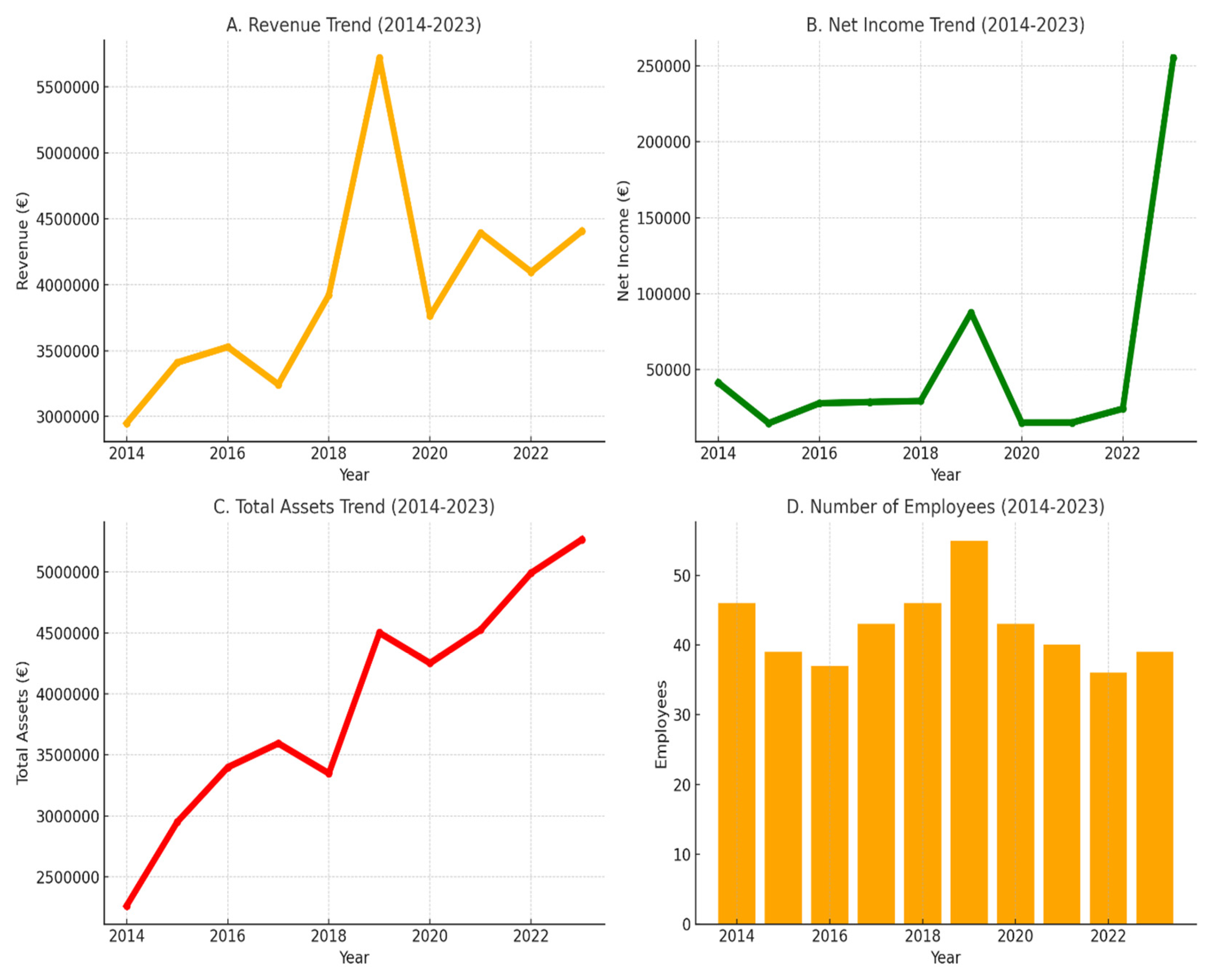

Tecnomulipast S.r.l. is a private Italian SME based in Gravina in Puglia, Southern Italy, with a specialisation in food, beverages, and tobacco machinery design and manufacturing (ATECO 289300). The company, established in 2005, has 39 employees and turnover of €4.4 million in 2023. Tecnomulipast has an Engineer-to-Order (ETO) system, creating customised solutions in the form of silos, elevators, and filters with high vertical integration in design, purchase, assembly, and test. Although the company has a leadership position in the local market and good financial situation (EBITDA 11.24%, ROE 36.65%, ROA 7.40%), the company also faces essential constraints, such as dependence on short-term debts (debt-to-equity ratio: 1.87) as well as the absence of an integrated ERP system. It means unconnected streams of data, manual activities, and poor scalability.

Tecnomulipast is undergoing a digitalization drive in accordance with Industry 4.0 principles, backed by the Regione Puglia’s “Titolo II - Capo II” PIA programme. Proof of the concept of the project is a robot laser spot welding workstation with IoT sensors and inspection cameras to monitor in the moment and log data. Supporting the investment are a full-stack ERP platform to link the design, stocks, and production, and a data analytics platform to process the un/semi-structured types of data. The project is to enhance efficiency, flexibility, and data-driven governance, and to establish the company as a regional benchmark in SME digitalization (

Figure 1).

3. Literature Review

The digitization of Tecnomulipast, an Italian South-SME, is in close correspondence with Industry 4.0, driven by automation, IoT, and analytics. These enable monitoring in real-time, predictive preventive measures, and set the stage for integration with AI. Scarton et al. (2025) document a corresponding application of expert systems to automated control of quality, replicating Tecnomulipast’s laser welding equipment in diagnosing faulty conditions. Rehman et al. (2025) draw a connection between IoT adoption and analytics and SME competitiveness in underpinning the regionally-sponsored digitization of Tecnomulipast. In the forthcoming years, Latino (2025) provides an Industry 5.0 model of human-centered and sustainable innovation. Tecnomulipast’s scalable digital infrastructure implies preparedness for the next step. Tanane et al. (2025) lay out TMQ 4.0, synergizing quality along the production value chain—an approach repeated in Tecnomulipast’s sensor-based monitoring. Lastly, Sima et al. (2025) propose the exploitation of knowledge by means of recommender systems, repeated in the analytics- and learning-based decision-making of Tecnomulipast. Blockchain, in turn, is absent from the system of Tecnomulipast, but Alimohammadlou and Alinejad (2023) view complexity and cost as barriers to adoption by SMEs, underling the demand for scalable, contextual solutions. Elhusseiny and Crispim (2022) view infrastructure, skills, and alignment as Industry 4.0’s main challenges—gaps filled in Tecnomulipast through public-private partnership and regional policy intervention. Adoption of smart technology in phases reflects the institution advocated by Amaral and Pečas (2021) for the digitization of SMEs. Estensoro et al. (2022) and Somohano-Rodríguez et al. (2022) echo the demand for internal capacity for innovation—a Tecnomulipast’s digitization strength. Turkyilmaz et al. (2021) compare such success to infrastructure shortcomings in Kazakhstan, while Atieh et al. (2023) view intelligent manufacturing as beneficial in Tecnomulipast’s laser welding system. Han and Trimi (2022) view data platforms in SME partnership, an approach repeated in Tecnomulipast’s IoT- and imaging integration in real-time. In the name of sustainability, Onu and Mbohwa (2021) equate Industry 4.0 to efficiency and the minimization of the use of resources—targets facilitated by Tecnomulipast’s application of sensors in monitoring. Peter et al. (2023) distil regional adaptation needs, and Mofolasayo et al. (2022) propose lean–digital integration, seen in Tecnomulipast’s look-ahead maintenance and real-time monitoring approach. Chang et al. (2021) examine Industry 4.0 readiness in a hybrid MCDM approach, underpinning strategic congruence’s function. Tecnomulipast’s AI-infrastructure and operations-driven by data are high in both dimensions. Also FinTech-focused, Soni et al. (2022) prioritize structure of decision-making and tech-business congruence—values embodied in the company’s change plan. Ricci et al. (2021) prioritize leverage of external knowledge and institutionally-backed aid, such as that of Regione Puglia, at the centre of Tecnomulipast’s development. Fernando et al. (2022) regard capability and cost barriers as dominant constraints. Tecnomulipast removes them through capability-building and external aid. Saad et al. (2021) prioritize organization readiness, a value evident in the company’s scalable, analytics-driven infrastructure. Kee et al. (2025) regard leadership, infrastructure, and training, driven to the heart of Tecnomulipast’s model. Ali and Johl (2021) align TQM with sustainable performance, evident in Tecnomulipast’s assurance of quality in real-time. Liu et al. (2022) and Sriram & Vinodh (2021) prioritize partnership and digitization readiness, both of them configuring Tecnomulipast’s environment. And, ultimately, Nagy et al. (2023) look to machine intelligence and cyber-physical infrastructure, both of them central to Tecnomulipast’s predictive, adaptive intelligent manufacturing approach.

Table 1.

Synthesis of the literature review with their impact on the case study.

Table 1.

Synthesis of the literature review with their impact on the case study.

| Theme |

Description |

Key Articles (APA Short) |

Relevance to Case |

| Smart Manufacturing & Technological Integration |

Focus on automation, AI, IoT, and smart machines applied in SME production environments. |

Scarton et al. (2025), Tanane et al. (2025), Atieh et al. (2023), Sima et al. (2025), Chang et al. (2021) |

Directly supports Tecnomulipast’s implementation of automated laser welding, sensor networks, and AI-ready infrastructure. |

| Organizational Readiness & Strategic Management |

Readiness factors, leadership, digital maturity models, and implementation frameworks. |

Latino (2025), Kee et al. (2025), Sriram & Vinodh (2021), Saad et al. (2021), Antony et al. (2023) |

Aligns with Tecnomulipast’s structured transformation, guided by innovation-focused leadership and policy support. |

| Data-Driven Innovation & Performance |

Use of analytics, decision-making platforms, and performance impact of I4.0 adoption. |

Rehman et al. (2025), Han & Trimi (2022), Somohano-Rodríguez et al. (2022), Estensoro et al. (2022), Soni et al. (2022) |

Reflects Tecnomulipast’s real-time analytics, performance monitoring, and innovation capacity. |

| Barriers, Policy, and Regional Context |

Challenges in SME digitalization, especially in emerging or underserved regions. |

Elhusseiny & Crispim (2022), Amaral & Peças (2021), Turkyilmaz et al. (2021), Alimohammadlou & Alinejad (2023), Peter et al. (2023) |

Relevant to the firm’s public-private funding (Regione Puglia), and regional challenges overcome in Southern Italy. |

4. Methodology

The methodology in this study is based on a multi-method qualitative approach, drawn from organizational studies, industrial development, and system science. The study draws on embedded case study research (Yin, 2009), action research (Coghlan, 2019), and design science methodology (Hevner et al., 2004) to obtain depth as well as replicability in one set of industrial settings.

Case-Embedded and Context-Aware. The research explores Tecnomulipast S.r.l. as an embedded case in the wider socio-economic context of Southern Italy, influenced by constraints in digital infrastructure. Utilizing the contextual approach makes it possible to explain in depth the digital transformation process by including all three factors: technological, managerial, and policy. The research embraces Eisenhardt’s (1989) case study approach to theory development because it frames Tecnomulipast both as an analytical unit of analysis as well as an empirical case that is generalizable to digitalizing SMEs.

Triangulation Data Collection. In order to achieve construct validity, the research applies triangulation (Denzin, 2017; Patton, 1999), from three data resources: (1) document analysis from project plans, compliance files, and PIA program materials; (2) field observation from the deployment of IoT-integrated robotic welding and monitoring systems; and (3) shopfloor with engineers, allowing for joint process mapping and action planning.

Phased Temporal Structuring. In line with action research and phases of an innovation cycle (Coghlan, 2019; Hevner et al., 2004), there were four phases in this intervention: diagnostics (initial KPI measurement), co-design (designing the ERP, CAD, and IoT architecture), pilot rollout (live implementation of smart systems and application of real-time dashboards), and validation (KPI measurement and learning loop implementation). These define the guidelines for iterative trial and development in Design Science Research (DSR).

Sociotechnical Model. A significant methodological accomplishment was to apply digital simulation techniques to interoperability representation across systems, e.g., CAD-to-ERP flows, IoT data streams, and near real-time visualization. These practices align with Industry 4.0 architecture approaches (Kagermann & Wahlster, 2022) as well as cyber-physical system design (Baines et al., 2007), enhancing methodological validity.

Policy-Embedded Analysis. Policy analysis is embedded in the research to study the impact of local co-financing mechanisms, specifically Titolo II - Capo II PIA, on influencing innovation strategies as well as on risk management. Grounded in National and Regional Innovation Systems theory (Lundvall, 1992; Edquist, 2013), this approach situates firm-level change in an institution- and policy-embedded context.

5. Digital Transformation Framework and Technological Integration and System Architecture

Tecnomulipast’s digitalization is an exemplary case of how SMEs can move from superficial technology enhancements to systemic innovations in operations and management (Subramanian, 2024). Led by strategic innovation, the company embedded digital capabilities into decision-making, workflow, and value generation in the long-term, adopting a mode of organizational ambidexterity—managing exploration of new technology in the presence of established capabilities (Qin et al., 2025). Core to the change is the new IoT-empowerd laser welding system, integrated to a centralized cyber-physical platform for processing data in-network in real-time. This operational model supports traceability, anomalous analysis, and optimization of performance, and was designed to be scalable in architecture to accommodate integration of AI in the future (Ruiz & Muñoz, 2025). Roll-out marks a departure from manual craftsmanship to intelligent automation, increasing throughput, uniformity, and versatility in Tecnomulipast’s Engineer-to-Order (ETO) manufacturing paradigm. Transformational change was spurred by cross-functional leadership and collaboration with LUM Enterprise, allowing digitization of potential into operational value (Satwekar et al., 2024). Practices of co-creation, such as workflow design and process mapping, ensured alignment of technology and user requirements, promoting ownership and continuing learning (Brink et al., 2023).

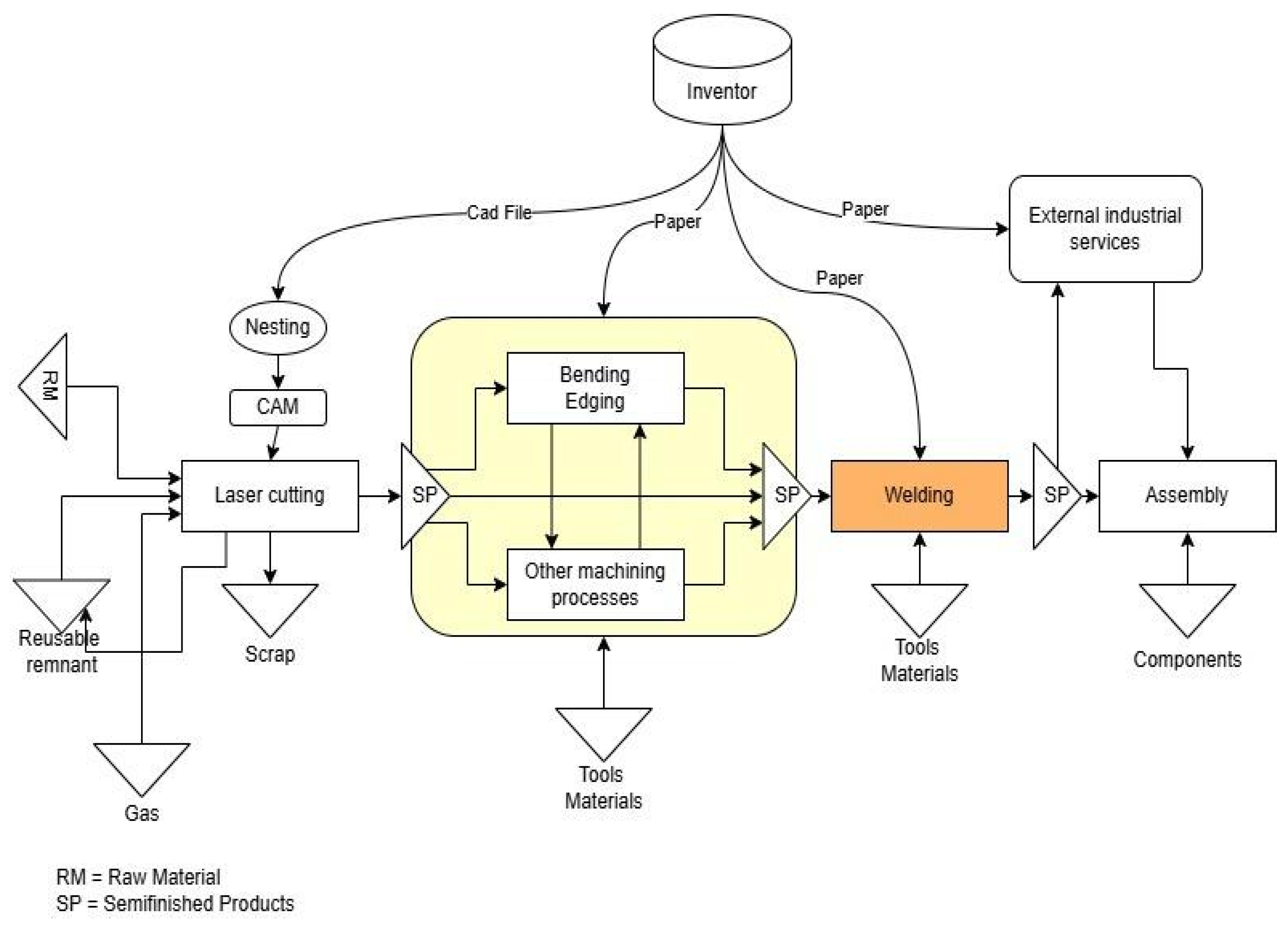

Tecnomulipast used a four-step model anchored in action research and design science research (Farinelli et al., 2023). The diagnosis step established KPIs and identified issues such as the lack of integration of ERP. During the co-design step, cross-functional teams defined a modular architecture with interoperable ERP and AI readiness. The step of pilot deployment started with the laser welding cell in an IoT frame, with ongoing monitoring and ongoing fine-tuning potentialities. The project validation step recorded general performance gains on production management and collected comments from personnel, as a success from both technical and cultural perspectives. The prime facilitator of the project was policy-based funding under Regione Puglia’s Titolo II – Capo II PIA, that provided both funding and planning as well as a risk-governance structure (Satwekar et al., 2024). Beside the impact on production management, the automated system also co-exists with CAD tools and facilities, thereby allowing design-to-production tracing. This enables rapid changeover of variant products and avoids human errors—critical in high-precision, low-run productions. The integration framework is also AI-ready and will play a central role in the development of enhanced optimization policies for production efficiency, product and process quality as well as for smart maintenance approaches (

Figure 2).

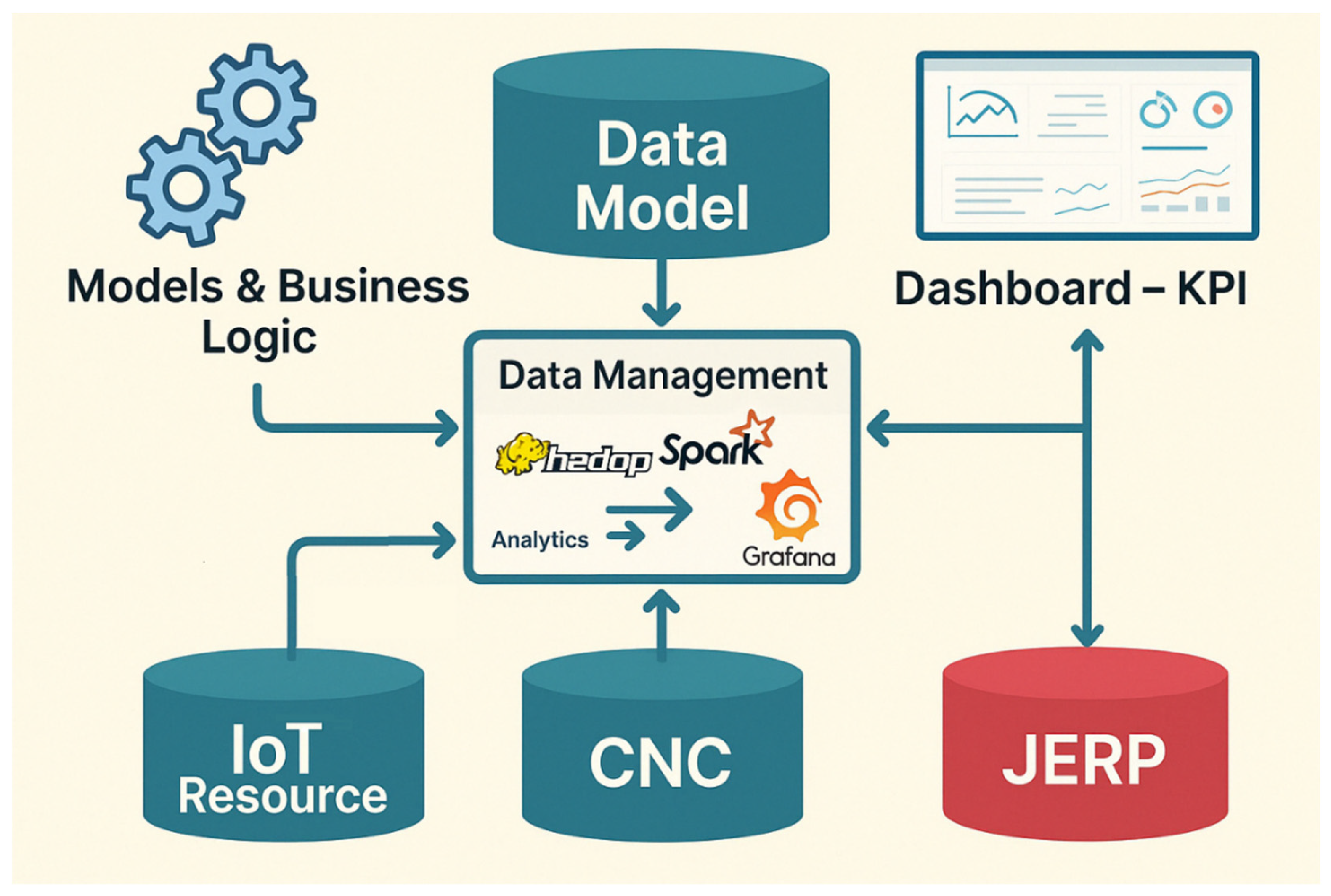

Organizationally, the system triggered a change in culture allowing increased cross-functional coordination, employee training, and data literacy. Experimentation and execution were taken on by operators, allowing for progress toward standard processes and digital literacy. Underlying digital and the infrastructure redefined a previously fragmented environment to an integrated system for production. Utilizing such an architecture for technology, additional IoT capabilities could in future be added. As an example, additional sensors and high-resolution cameras could collect real-time data on machine condition, temperature, and alignment and pipe that through to an AI engine for smart use. That could support real-time alerting, predictive repair, and closed-loop control, to maximize productivity with minimum downtime. Sensor data can feed to an analytics platform in the center, processing unstructured (e.g., images, such as from a camera) and structured (e.g., cycle time, telemetry, such as temperature, pressure, and speed of the motors) data. KPI and anomaly reports can push to multiple levels of users through dashboards, allowing data-driven action in both top-management and shop floor levels. The AI-readiness in the platform offers potential to add new tech in future, preparing Tecnomulipast for Industry 4.0, and opening doors to new challenges for technology. Its modular, scalable construction makes future-proofing simple, allowing new ideas to incorporate without needing to redesign, allowing continued flexibility for adapting, as well as flexibility for strategy. The company’s real-time data-visualization platform is the cognitive layer for their smart factory (

Figure 3).

Designed to serve both operational decision-making and strategic insight, democratizing the access to the data, breaking down departmental silos, and enabling predictive analysis, the platform boosts governance, responsiveness, and robustness. Through the provision of anticipatory intervention, such as auto-correcting the laser target, or preventive servicing, the platform enhances governance, responsiveness, and robustness. Overall, Tecnomulipast’s transformation involves the blending of custom engineering, networking, and organization learning. It demonstrates how SMEs, by visionary leadership, innovation by collaborative partnership, and the support from public structures devoted to industry development, can be turned into digitally mature, AI-ready firms. The company’s achievement offers a replicable model for Industry 4.0 rollout in high skilled resource settings, and Tecnomulipast emerges as a benchmark to be followed in intelligent manufacturing in Southern Italy.

6. Strategic and Organizational Implications

One of the most significant consequences of Tecnomulipast’s change has been the trend toward data-driven governance. No longer relying on manual, experience-driven decisions, the company had to cope with disjointed data and lagging responses. Since the installation of IoT infrastructure and monitoring, managers have access to live operational data, supporting faster, fact-based responses to deviations in production and quality. An integrated dashboard pools both unstructured (visual feeds) and structured inputs (KPIs, sensor logs), supporting tighter feedback loops and allowing mid-level managers to autonomously make aligned decisions. The change constitutes a shift toward proactive, away from reactive, management and the exercise of core Industry 4.0 capabilities. The changeover to semi-automated manufacturing necessitated considerable change in organization. Initial resistance, particularly in regions based on tacit knowledge and paper-based processes, was countered by a formal change management plan, stressing cross-functional working, iterative training, and co-participative design.

Workflows became the main training arenas in which teams redesigned the processes, formalized methods, and brought the ETO (Engineer-to-Order) model into alignment with the new modular digital platform. The starting point (AS-IS) exposed entrenched structural issues—such as poor departmental synchronization, document untraceability, and the lack of workflow standards. These were overcome, however, by more than new technology, as they necessitated cultural transformations in accountability and procedure discipline, the hallmark of digital maturity. Tecnomulipast’s experience provides other SMEs with important lessons in management. To begin, digital innovation has to be viewed as an ongoing capability, rather than a one-time project. The success resulted from strategic insight, good leadership, and a process of iterative implementation. Second, interoperability—particularly in the domains of CAD, ERP, and shopfloor—was essential. Initial inefficiencies resulted from workflow fragmentation rather than technology constraints. Third, access to public funding like the Titolo II – Capo II PIA program was crucial. Beyond enabling investment, its structure promoted formal innovation planning, KPI development, and external validation, improving accountability and reducing risk. Finally, by embedding data literacy, iterative learning, and cross-functional dialogue, Tecnomulipast has laid a foundation for continuous innovation and scalability, becoming a resilient model for digital transformation in the SME sector.

7. Conclusions

The case of Tecnomulipast S.r.l. shows how a typical manufacturing SME, in a low digital maturity region, can successfully implement a planned, innovation-driven digital revolution. At the heart of the research project was the integration of an automated laser welding cell with a data-analytic infrastructure that provides data management and processing of both structured and unstructured process data. These capabilities facilitated process optimization and pavd the way for anomaly detection, and monitoring in real-time, underpinning a more intelligent, adaptive production system. Underpinning the change was a manager-centric model of strategic innovation, change by participation, and cross-functional integration. A sequential approach, enabled by investments on IT and advanced production systems, facilitated implementation a new operation model strongly based on the digitalization of the order management process and a real time control of the manufacturing steps. Titolo II - Capo II PIA regional funding helped to drive down the costs of the project, embedding the initiative in a top-down approach to an innovation system. Organizational change at Tecnomulipast involved increased agility, decision-making through data, and a change in collaboration practices. The mapping of the new digital architecture to the ETO production paradigm placed the company as a model for Industry 4.0 uptake among small, resource-constrained firms. However, the project is still in process, and the ultimate effects of scalability and profitability are to be determined.

The qualitative approach of the study may preclude broader transfer, and maximum integration of the ERP-CAD and production systems is still in progress, so the potential of the system has yet to be fully unlocked. Future research can extend to post-implementation performance in similar SMEs, with a focus also to be placed on AI uptake, resiliency, and digital talent development. Cross-case analysis across regions might identify how institutionally supported pathways to change vary by institution, culture, and region. Tecnomulipast demonstrates the capability of modular, interoperable, and data-centric architecture to enable SME digitalization. The next step may be the further embedding of AI to enable predictive quality control, supply chain automation, and workflow adaptability. In the future, cybersecurity, interoperable standardization, and green manufacturing would assume greater importance, necessitating the development of dynamic capabilities beyond technology upgrades. At Tecnomulipast, ongoing innovation sets the company up to achieve a leadership status in the region of smart manufacturing, supporting both industrial renewal and economic renewal in the South of Italy.

Acknowledgment

Results obtained in the research and development project “Tecnomulipast” - Codice Pratica 683TK4 - a valere sul Bando Programmi Integrati di Agevolazioni PIA Piccole Imprese (Art 27 Reg. Regionale 17/2014 e smi).

References

- Ali, K., & Johl, S. K. (2021, June). Impact of total quality management on SMEs sustainable performance in the context of industry 4.0. In International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Intelligent Systems (pp. 608-620). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadlou, M., & Alinejad, S. (2023). Challenges of blockchain implementation in SMEs’ supply chains: an integrated IT2F-BWM and IT2F-DEMATEL method. Electronic Commerce Research, 1-43. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A., & Peças, P. (2021). SMEs and Industry 4.0: Two case studies of digitalization for a smoother integration. Computers in Industry, 125, 103333. [CrossRef]

- Antony, J., Sony, M., & McDermott, O. (2023). Conceptualizing Industry 4.0 readiness model dimensions: an exploratory sequential mixed-method study. The TQM Journal, 35(2), 577-596. [CrossRef]

- Atieh, A. M., Cooke, K. O., & Osiyevskyy, O. (2023). The role of intelligent manufacturing systems in the implementation of Industry 4.0 by small and medium enterprises in developing countries. Engineering Reports, 5(3), e12578. [CrossRef]

- Baines, T. S., Lightfoot, H. W., Evans, S., Neely, A., Greenough, R., Peppard, J., ... & Wilson, H. (2007). State-of-the-art in product-service systems. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: journal of engineering manufacture, 221(10), 1543-1552.

- Battistoni, E., Gitto, S., Murgia, G., & Campisi, D. (2023). Adoption paths of digital transformation in manufacturing SME. International Journal of Production Economics, 255, 108675. [CrossRef]

- Brink, T., Sørensen, H. B., & Neville, M. (2023). Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises Strategizing Digital Transformation: Backend & Frontend Integration for Horizontal Value Creation. In Digitalization and Management Innovation (pp. 58-77). IOS Press. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. C., Chang, H. H., & Lu, M. T. (2021). Evaluating industry 4.0 technology application in SMES: Using a Hybrid MCDM Approach. Mathematics, 9(4), 414. [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, D. (2019). Doing action research in your own organization.

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Edquist, C. (2013). Systems of innovation: technologies, institutions and organizations. Routledge.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. [CrossRef]

- Elhusseiny, H. M., & Crispim, J. (2022). SMEs, Barriers and Opportunities on adopting Industry 4.0: A Review. Procedia Computer Science, 196, 864-871. [CrossRef]

- Estensoro, M., Larrea, M., Müller, J. M., & Sisti, E. (2022). A resource-based view on SMEs regarding the transition to more sophisticated stages of Industry 4.0. European Management Journal, 40(5), 778-792. [CrossRef]

- Farinelli, M., Canterino, F., & Caniato, F. (2023). Guiding digital transformation and collaborative knowledge creation in the pharmaceutical supply chain through action research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 59(4), 585-616. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y., Wahyuni-TD, I. S., Gui, A., Ikhsan, R. B., Mergeresa, F., & Ganesan, Y. (2022). A mixed-method study on the barriers of industry 4.0 adoption in the Indonesian SMEs manufacturing supply chains. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 14(4), 678-695. [CrossRef]

- Filieri, J., Goretti, G., & Terenzi, B. (2025). Integrating Design processes and Intelligent systems within supply chain digitalization, Two case studies in Made in Italy manufacturing. Intelligent Human Systems Integration (IHSI 2025): Integrating People and Intelligent Systems, 160(160). [CrossRef]

- Garzoni, A., De Turi, I., Secundo, G., & Del Vecchio, P. (2020). Fostering digital transformation of SMEs: a four levels approach. Management Decision, 58(8), 1543-1562. [CrossRef]

- Han, H., & Trimi, S. (2022). Towards a data science platform for improving SME collaboration through Industry 4.0 technologies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121242. [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004). Design science in information systems research. MIS quarterly, 75-105. [CrossRef]

- Kagermann, H., & Wahlster, W. (2022). Ten years of Industrie 4.0. Sci, 4(3), 26. [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. M. H., Cordova, M., & Khin, S. (2025). The key enablers of SMEs readiness in Industry 4.0: a case of Malaysia. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 20(3), 1042-1062. [CrossRef]

- Latino, M. E. (2025). A maturity model for assessing the implementation of Industry 5.0 in manufacturing SMEs: learning from theory and practice. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 214, 124045. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Sampaio, P., Pishchulov, G., Mehandjiev, N., Cisneros-Cabrera, S., Schirrmann, A., ... & Bnouhanna, N. (2022). The architectural design and implementation of a digital platform for Industry 4.0 SME collaboration. Computers in Industry, 138, 103623. [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B. A. (1992). National systems of innovation: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Francis Printer.

- Mofolasayo, A., Young, S., Martinez, P., & Ahmad, R. (2022). How to adapt lean practices in SMEs to support Industry 4.0 in manufacturing. Procedia Computer Science, 200, 934-943. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, M., Lăzăroiu, G., & Valaskova, K. (2023). Machine intelligence and autonomous robotic technologies in the corporate context of SMEs: Deep learning and virtual simulation algorithms, cyber-physical production networks, and Industry 4.0-based manufacturing systems. Applied Sciences, 13(3), 1681. [CrossRef]

- Onu, P., & Mbohwa, C. (2021). Industry 4.0 opportunities in manufacturing SMEs: Sustainability outlook. Materials Today: Proceedings, 44, 1925-1930. [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health services research, 34(5 Pt 2), 1189.

- Peter, O., Pradhan, A., & Mbohwa, C. (2023). Industry 4.0 concepts within the sub–Saharan African SME manufacturing sector. Procedia Computer Science, 217, 846-855. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J., Lin, J., & Filieri, J., Goretti, G., & Terenzi, B. (2025). Integrating Design processes and Intelligent systems within supply chain digitalization, Two case studies in Made in Italy manufacturing. Intelligent Human Systems Integration (IHSI 2025): Integrating People and Intelligent Systems, 160(160). [CrossRef]

- Qin, J., Lin, J., & Subramanian, A. M. (2024). Balancing exploitative and exploratory innovation in high-tech small-and medium-sized enterprises: the role of digitalization and performance feedback. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S. U., Jabeen, F., Shahzad, K., Riaz, A., & Bhatti, A. (2025). Industry 4.0 technologies and international performance of SMEs: mediated-moderated perspectives. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 21(1), 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Ricci, R., Battaglia, D., & Neirotti, P. (2021). External knowledge search, opportunity recognition and industry 4.0 adoption in SMEs. International Journal of Production Economics, 240, 108234. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S. V. C., & Muñoz, S. D. P. (2025). Challenges and Opportunities for Digital Leadership in the Transformation of Educational Organisations: Developing Digital, Soft, Intercultural, and Inclusive Skills. Multidisciplinary Organizational Training of Human Capital in the Digital Age, 25-58. [CrossRef]

- Saad, S. M., Bahadori, R., & Jafarnejad, H. (2021). The smart SME technology readiness assessment methodology in the context of industry 4.0. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 32(5), 1037-1065. [CrossRef]

- Satwekar, A., Miozza, M., Abbattista, C., Palumbo, S., & Rossi, M. (2024). Triad of digital transformation: Holistic orchestration for people, process, and technology. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. [CrossRef]

- Scarton, G., Formentini, M., & Romano, P. (2025). Automating quality control through an expert system. Electronic Markets, 35(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Sima, X., Coudert, T., Geneste, L., & de Valroger, A. (2025). Small and medium-sized enterprise dedicated knowledge exploitation mechanism: A recommender system based on knowledge relatedness. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 110941. [CrossRef]

- Somohano-Rodríguez, F. M., Madrid-Guijarro, A., & López-Fernández, J. M. (2022). Does Industry 4.0 really matter for SME innovation?. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(4), 1001-1028. [CrossRef]

- Soni, G., Kumar, S., Mahto, R. V., Mangla, S. K., Mittal, M. L., & Lim, W. M. (2022). A decision-making framework for Industry 4.0 technology implementation: The case of FinTech and sustainable supply chain finance for SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 180, 121686. [CrossRef]

- Sriram, R. M., & Vinodh, S. (2021). Analysis of readiness factors for Industry 4.0 implementation in SMEs using COPRAS. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 38(5), 1178-1192. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A. M. (2024). Balancing exploitative and exploratory innovation in high-tech small-and medium-sized enterprises: the role of digitalization and performance feedback. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. [CrossRef]

- Tanane, B., Bentaha, M. L., Dafflon, B., & Moalla, N. (2025). Bridging the gap between Industry 4.0 and manufacturing SMEs: A framework for an end-to-end Total Manufacturing Quality 4.0’s implementation and adoption. Journal of Industrial Information Integration, 100833. [CrossRef]

- Turkyilmaz, A., Dikhanbayeva, D., Suleiman, Z., Shaikholla, S., & Shehab, E. (2021). Industry 4.0: challenges and opportunities for Kazakhstan SMEs. Procedia Cirp, 96, 213-218. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).