1. Introduction

Indoor farming or controlled environment agriculture (CEA) has been a rapidly growing research topic due to both climate destabilization [

1] leading to increased conventional agriculture inconsistency as well as new technological developments like high-efficiency light emitting diode (LED) lighting [

2]. LEDs consistently outperform conventional artificial lighting for growth, yield, and nutritional content of various plants [

3,

4]. As LEDs allow for granular spectral tuning, research often centers around the spectral impacts on the growth, yield, and various nutritional content of the resulting plants [

5]. This work has resulted in a widely accepted result that red (625 – 700nm) and blue (425-475nm) light is required for ideal fresh mass production, and that supplemental green (475-625) and infrared (IR) (700-750nm) lights also improve the photosynthesis and health level of some crops [

6]. In this regard, several studies agree that optimal growth occurs with a blue:red ratio of 0.5 or higher [

7,

8,

9]. It has been widely shown that far red light promotes total biomass and elongation [

10], red light promotes biomass and reduces nitrate concentration [

11], green promotes growth [

12] and blue increases chlorophyll [

11] and flowering [

13]. In general, plants grown under multiwavelength irradiation will have higher photosynthetic activity and higher healthy growth [

14,

15]. The vast majority of these studies have focused on conventional horizontal growing systems. Recently, however, increases in yield per unit area have been observed with true vertical farming in walls [

16]. Systems like the agrivoltaics agrotunnel, enable extremely high land utilization in vertical grow walls [

17]. The agrivoltaics agrotunnel, operates with conventional agrivoltaics (partially transparent solar photovoltaic (PV) systems providing shading for conventional outdoor agriculture) providing the electricity to power heat pumps, water pumps and LED lighting for a CEA tunnel [

17]. The optimization of LEDs is particularly important for this type of CEA as the capital cost of the system is dependent on the energy use as the PV provide all the electric power for the CEA. For example, if part of the spectra (and thus energy) that is used for grow lights can be reduced, the overall size of PV system necessary for net zero production would also be reduced. The impact of spectral effects on these systems on the agrotunnel and the broader true vertical growing is relatively unexplored. Thus, the impacts of spectral lighting on CEA in vertical systems have not yet been verified.

To fill this knowledge gap, this study investigates the impact of three spectral light treatments on the plant growth in vertical farming of relatively unexplored root vegetables: radishes and turnips. The specific biological events activated by each wavelength range are explored for: designated red (620nm - 700nm), white (425nm - 650nm), and full spectrum (425nm - 750nm) light as well as species' varying response to identical treatment. The results will be compared against prior studies and discussed in the context of using specific light recipes for individual crops to provide sustainable CEA.

2. Materials and Methods

Seeds of Raphanus sativus (French breakfast radish) (Veseys Seeds, York, PE, Canada) and fuku Komachi (turnip) (Veseys Seeds, York, PE, Canada) were planted in rows of ports in the agrivoltaic agrotunnel (Food Security Structures Canada (FSSC), London, Canada) [

17]. Seeds which did not germinate were removed and discounted from the study. Total samples of each specimen are summarized in

Table 1.

The agrotunnel was kept at a temperature between 22° C to 23°C with a relative humidity between 55% and 60%. For the radish and turnip, the target electrical conductivity (EC) was 1.8-2.4, target pH was kept at 6-6.5. The grow walls in the agrotunnel operate as a hybrid aeroponic-hydroponic system. This system is neither pure hydroponic (roots are submerged in the nutrient water) nor pure aeroponic (roots are being sprayed with nutrient-rich water). The perforated peat pots with porous structure and 70-30 mixture of coco coir and perlite as the main grow substrate inside can absorb and hold the nutrient water, which is pumped to the top of the walls and allowed to drip and cascade through the pots. The irrigation cycle occurred twice in 2 minute watering duration each day. The 10-12-22 ForaPro and 14-0-0 Calcium+Micros FloraPro nutrients were being used mainly to feed the crops’ roots. It is important to highlight that the cultivation periods of both crops (from seed to the harvest) were 8 weeks.

Two walls facing one another were planted with 10 rows of 24 ports which were vertically divided into sections by curtains, and covered such that only the applied wavelength of light and lights were adjusted to provide specific wavelengths to each section as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Lighting was provided by BGL 360A lights (FSSC, London, ON, Canada). Wavelengths in each section were measured with an Oceanview Ocean FX mini spectrometer and analyzed with Oceanview software v2.0.16 (Orlando, FL, USA). From the absolute irradiance provided by Oceanview measurements, Equation 1 was used to find the energy of a single photon at a given wavelength (taken as the peak wavelength of each treatment):

where E is the energy of a single photon in Joules, h is Planck’s Constant (6.626 × 10

-34 Js) and c is the speed of light (3.00 × 10

8m/s). The photon flux can be calculated using Equation 2:

Finally, the flux can be converted to micromoles using Equation 3.

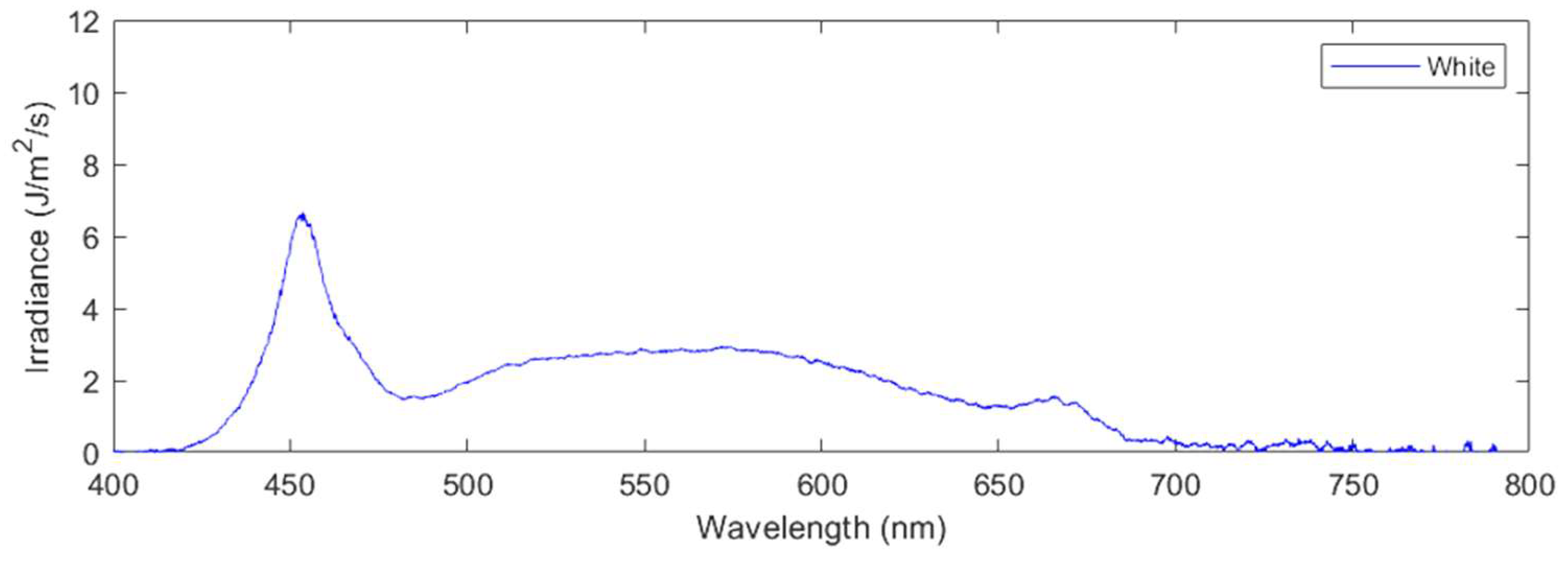

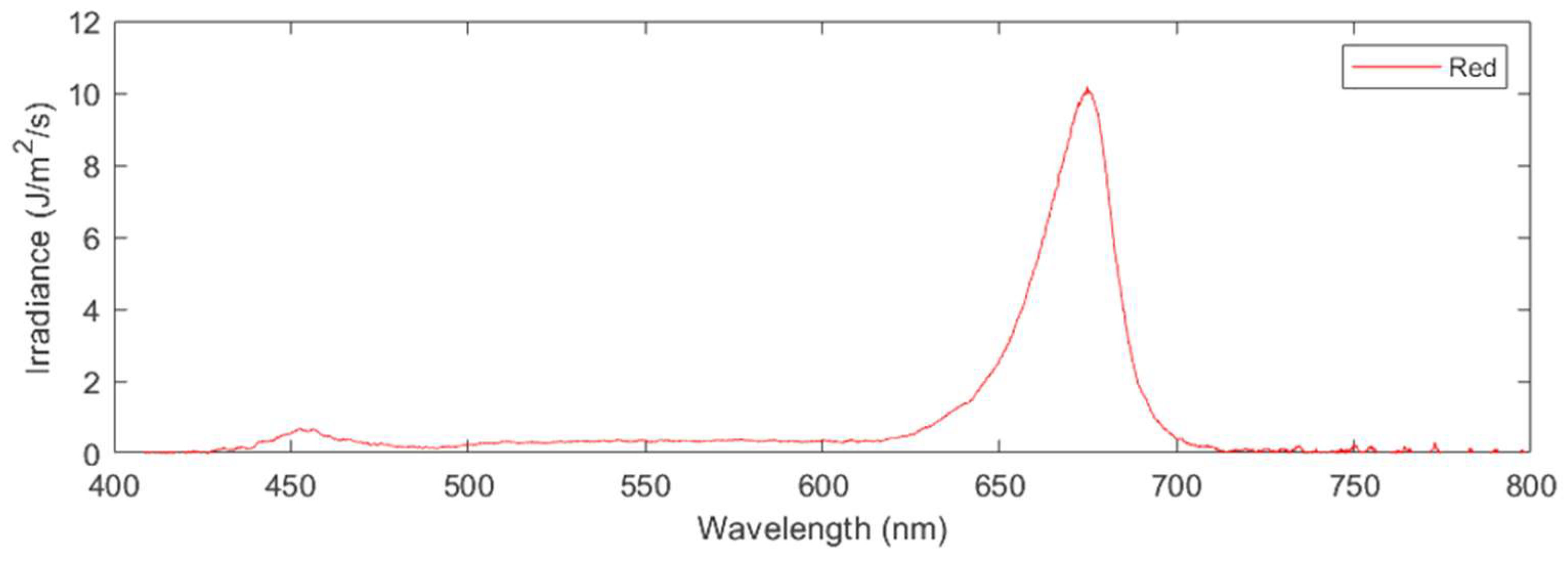

Applying these formulas yields the following photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) values for each of the three treatments applied: red light only (620nm-700nm) at a PPFD of 57 μmol/m

2/s (

Figure 3), white light only (425nm-650nm) with PPFD 63 μmol/m

2/s (

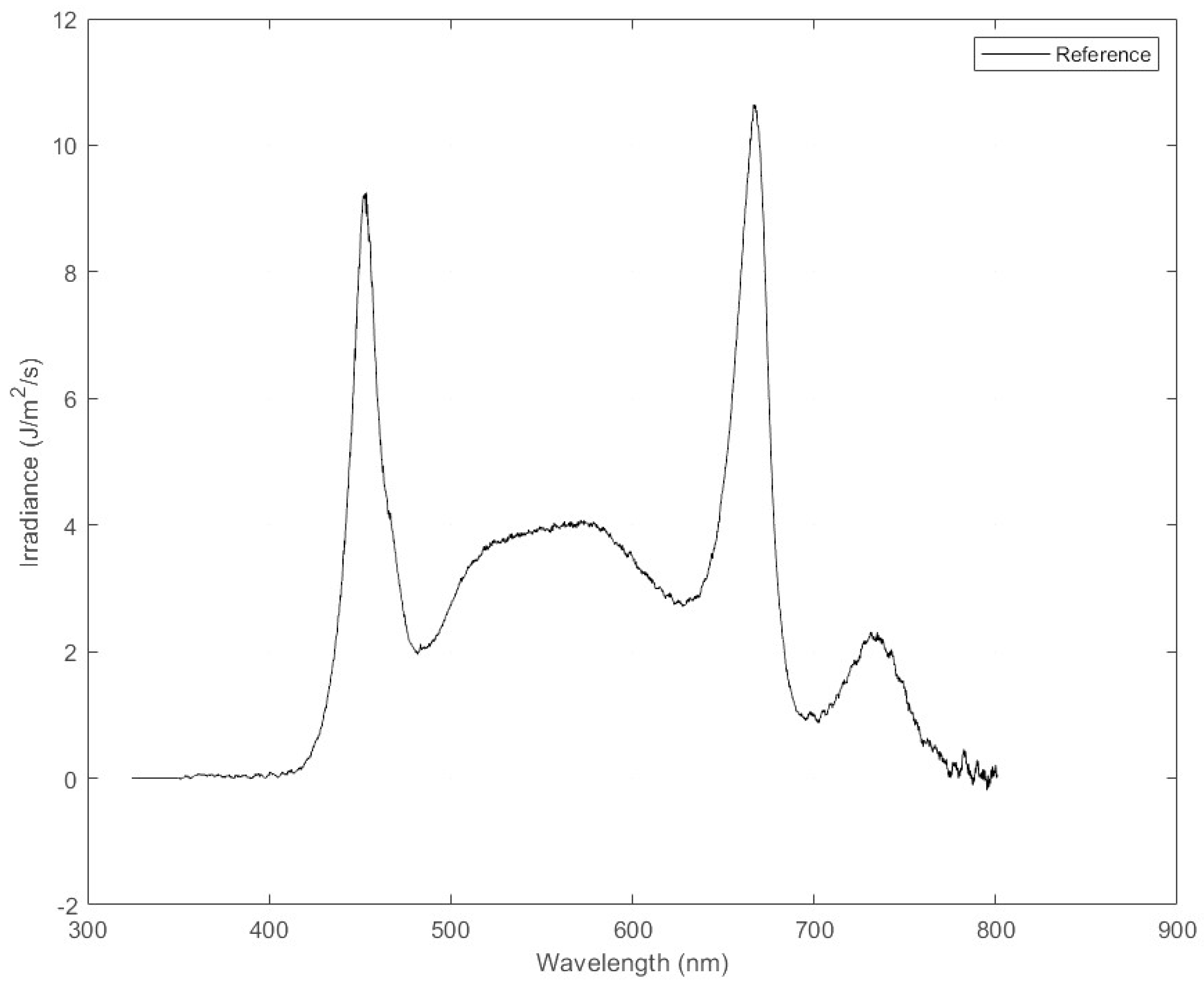

Figure 4), and control light which was the full spectrum, for a combined PPFD of the control of 123 μmol/m

2/s (

Figure 5).

Normalization of energy between treatments was used to better interpret the results, which was accomplished by similarly calculating the energy contribution from each treatment with Equation 1, integrated over the range of wavelengths characteristic to each treatment. These values were then compared to the total energy and their percentage contribution was used to accordingly scale the height, leaf count, and yield of each crop by an appropriate ratio. It was found that for the particular grow lights used, red contributed 28.9% of control light, and white was 70.2%, and the rest made up by IR light.

Measurements taken included plants’ green leaf height (mm), leaf count, chlorophyll content (atLeaf Chloropyll meter, Wilmington, DE, USA), and fresh yield measured with a Starfrit digital scale with an uncertainty ± 0.1g (Longueuil, Quebec, Canada). Measurements were taken for all plants in each treatment which were accepted to be within one standard deviation of the average. Plants were grown and harvested over an 8 week period using a 24-hours of light cycle.

3. Results

The height and leaf counts are presented both as the raw results and as the normalized results (adjusted for total energy provided by each treatment). This was done to better approximate the growth that would be seen under equal light intensity conditions, which were not explicitly tested in this study.

3.1. Plant Heights

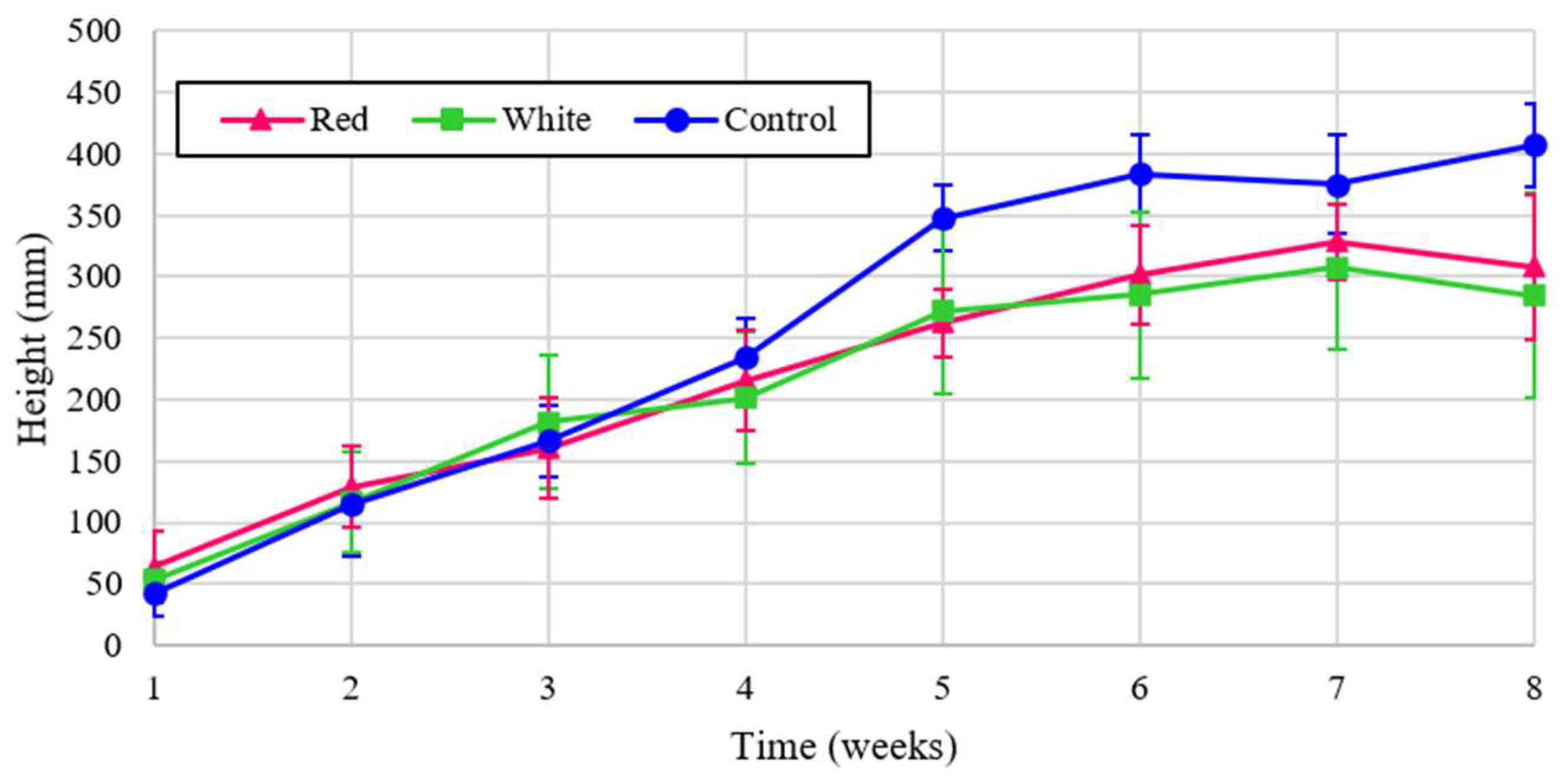

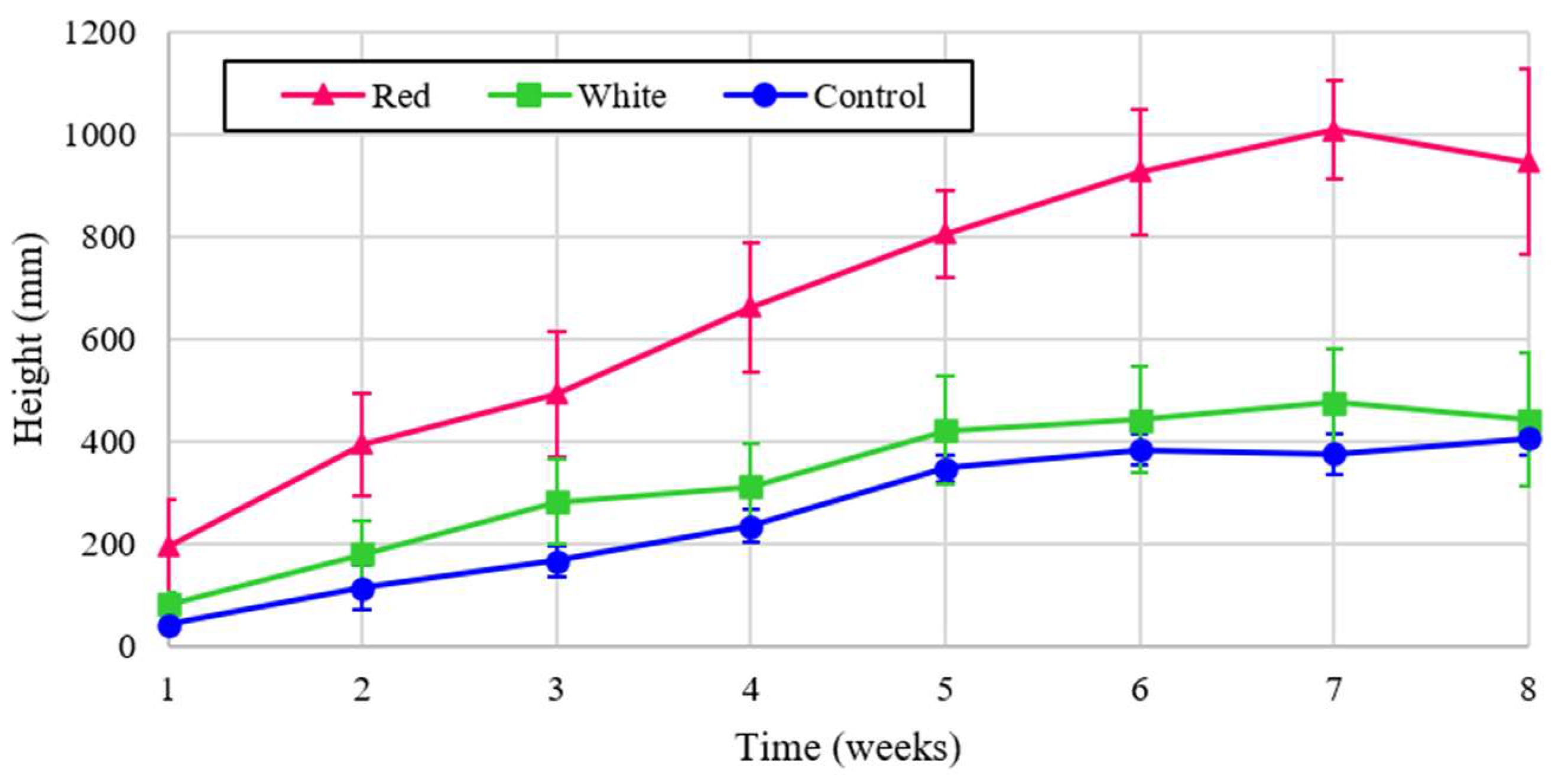

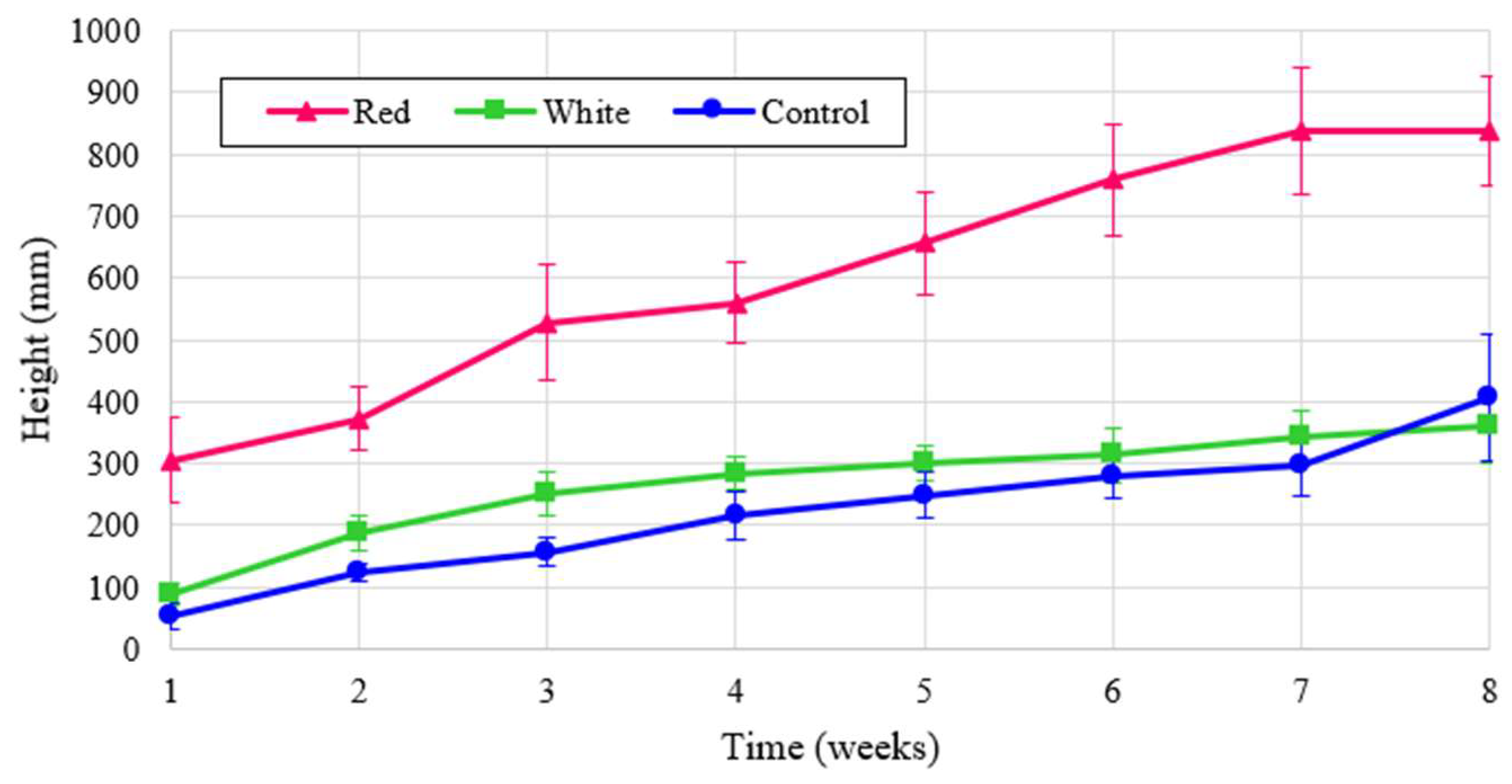

The experimental plant heigh is shown for turnips for the three light treatments in

Figure 6 over the eight week cultivation period and the normalized to energy heights is shown in

Figure 7.

Figure 6 shows that turnip height was the largest under the control, but when normalized for energy the turnip height was far and away the greatest with red light. The proximity of graphs for two treatments of red and white in

Figure 6 reflects the critical influence of red spectrum on the plant height despite the lower energy contribution of this wavelength. This significancy is shown in the dominant graph for the normalized analysis, shown in

Figure 7.

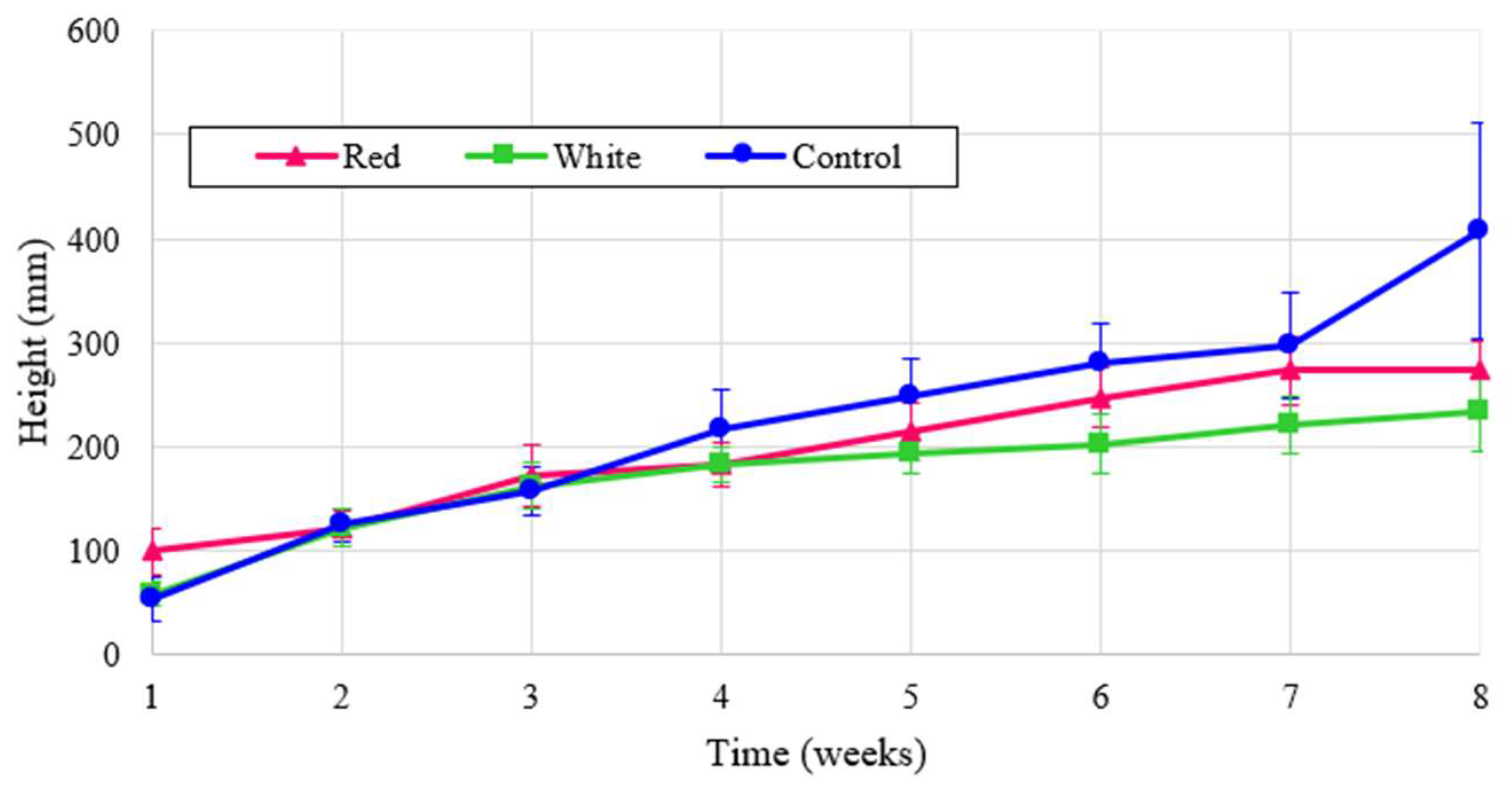

Similarly, the height of radish plants is shown in

Figure 8, and the normalized values are presented in

Figure 9. Though it may be expected that control would outperform the other treatments as it did in

Figure 8, radishes are also known to thrive under red light [

7] and these results were confirmed by the normalized values shown in

Figure 9. These results indicate that turnips have a similar response to red light as radishes.

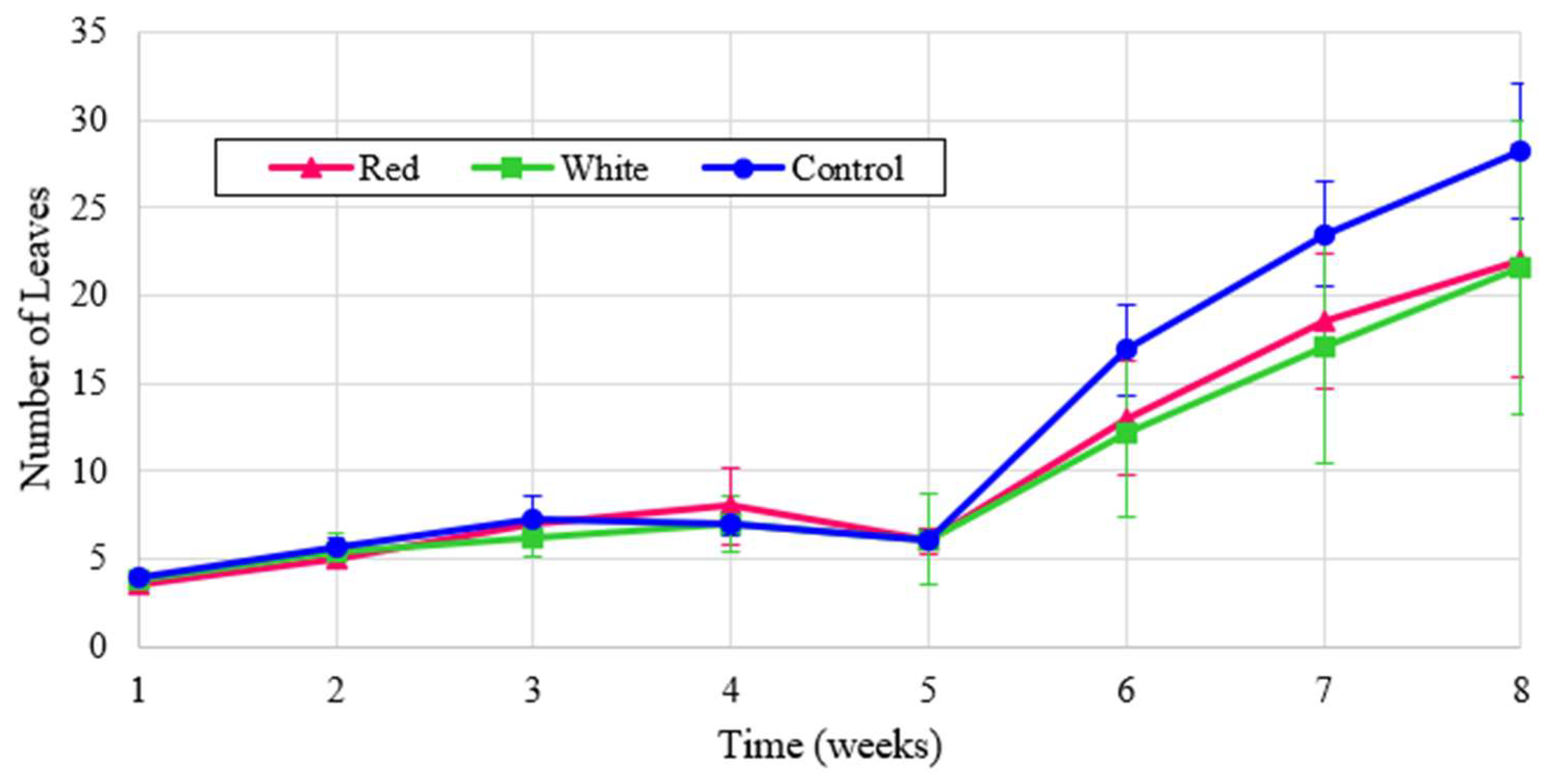

3.2. Leaf Count

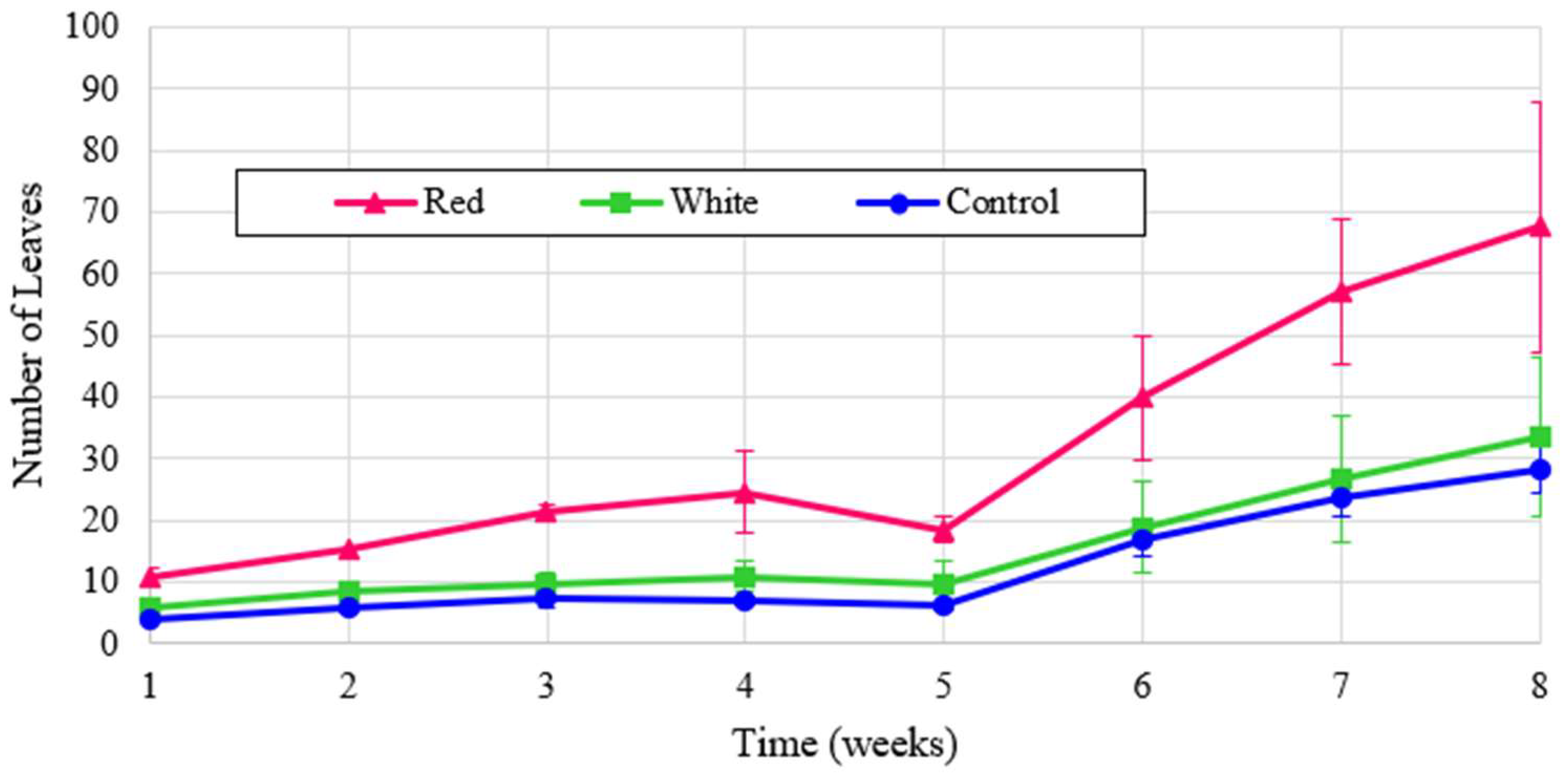

Leaf counts for experimental turnip results are shown in

Figure 10 and the normalized values are illustrated in

Figure 11. All treatments exhibit a similar growth pattern, and the red-light treatment produces more than double the leaf count when normalized. The small dip in counts in week 5 is due to some leaves dying out, which were quickly regrown.

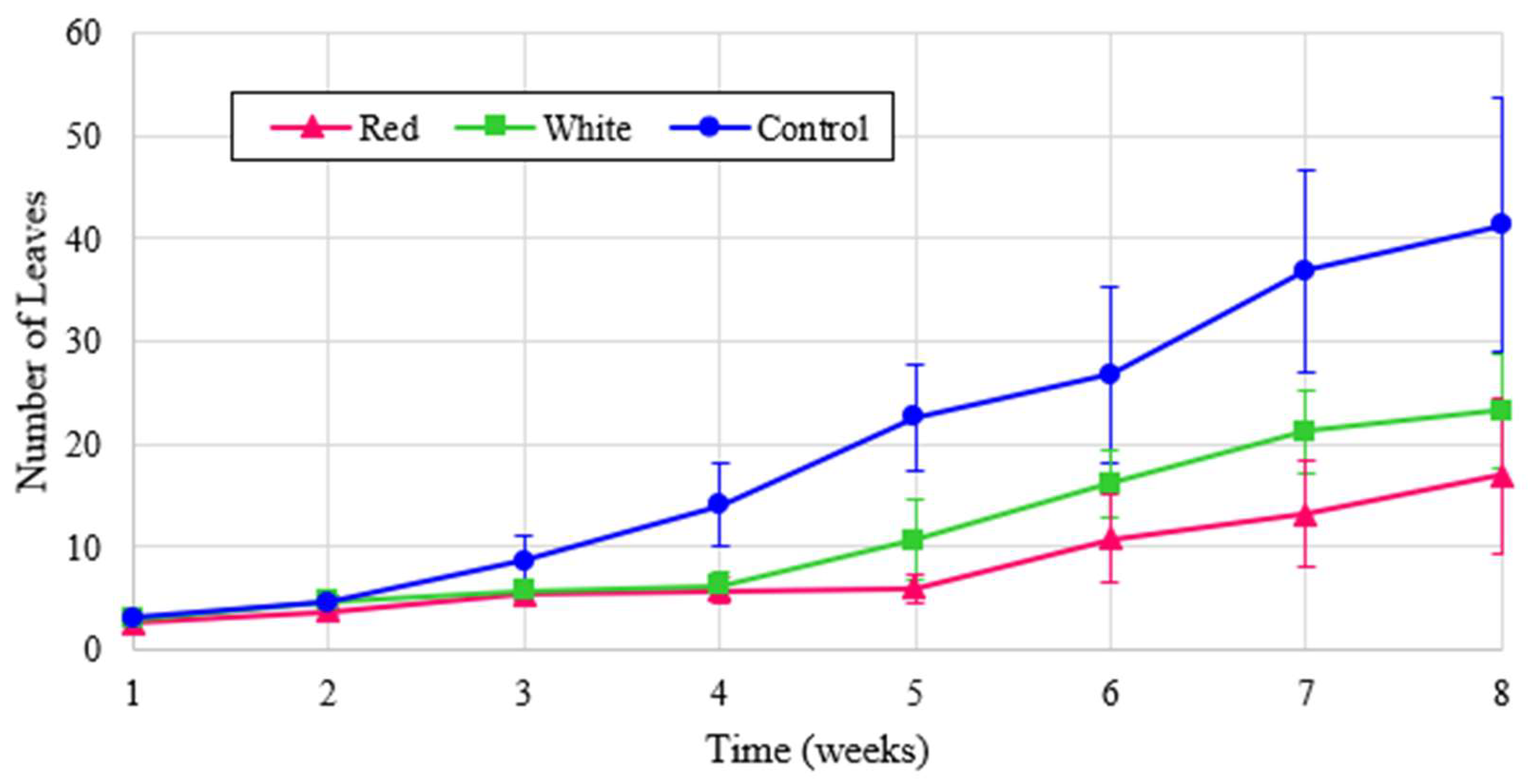

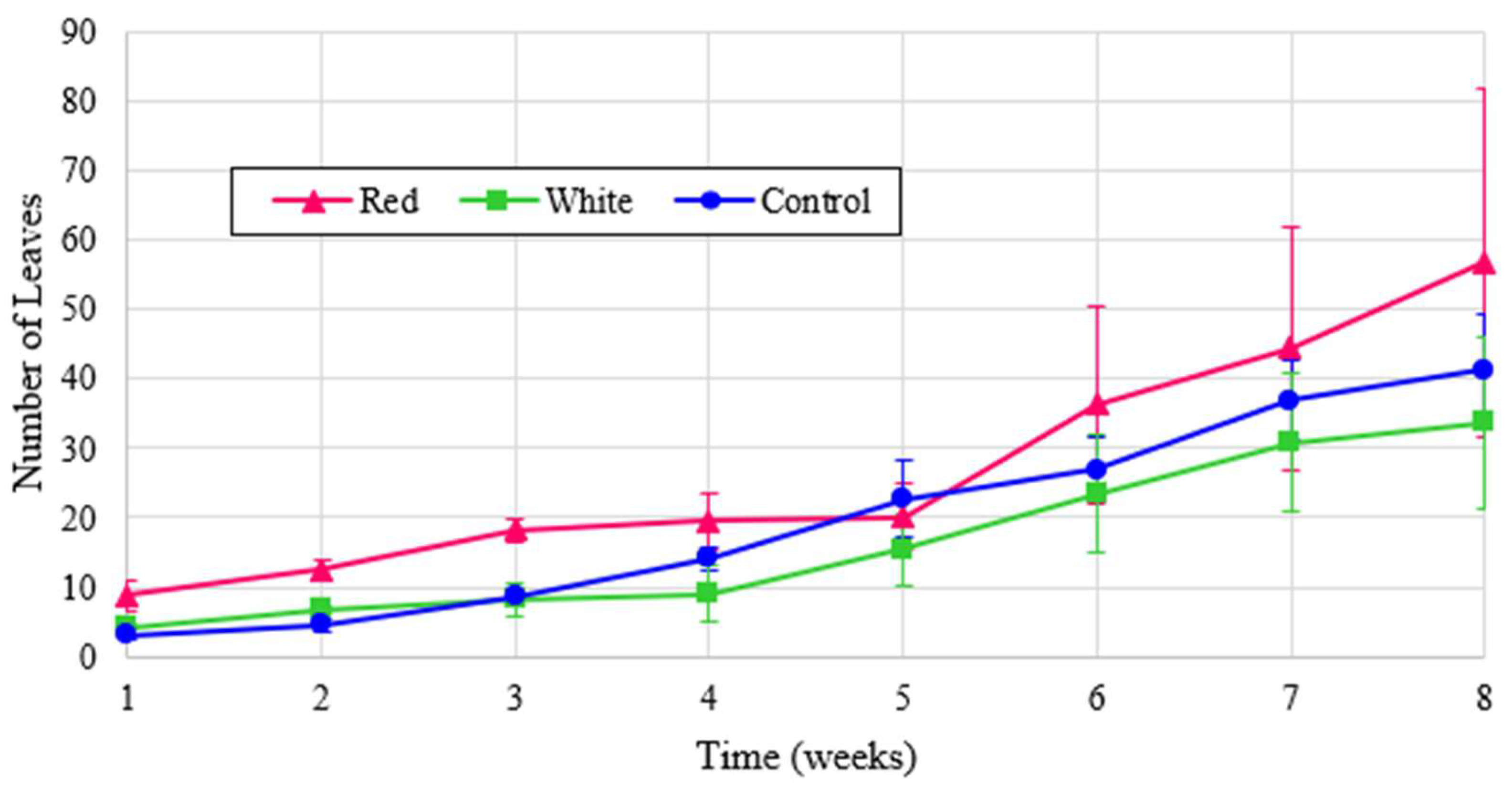

Similarly, the experimental leaf count for radishes is shown in

Figure 12 and the normalized values are reflected in

Figure 13.

Figure 12 shows that radish leaves increased consistently with the amount of energy, demonstrating that light intensity has the most impact on growth in agreement with [

7]. The higher growth can be attributed to control, white and red light treatments, respectively. Again, as shown in the normalized values in

Figure 13, the red light provided the highest leaf count. In

Figure 13, however, all treatments possess very close values of leaf numbers, indicating the indisputable contribution of white light in increasing the fresh biomass of the studied cultivars.

3.3. Crop Yields

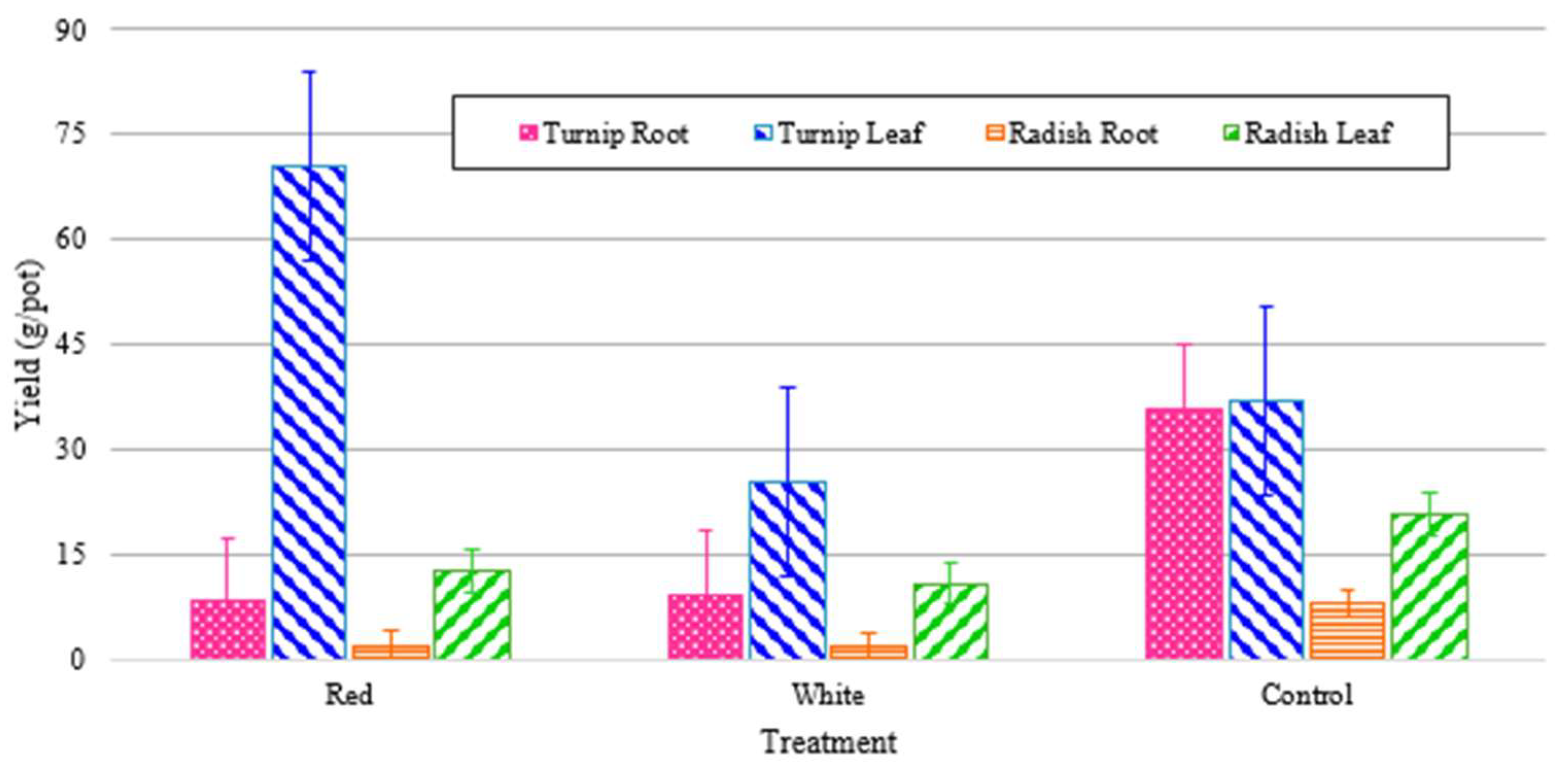

Plants were harvested after eight weeks, having lived their entire lives from germination in the walls under 24-hour light from their respective light treatments. Yields were recorded in grams per port (by averaging the harvested yield with respect to total number of active ports) for both the edible leaves and for the root crops. The experimental values are shown in

Figure 14, which shows that the turnips had much higher leaf and root yields as compared to the radishes. In both cases, as can be seen in

Figure 14, the leaf mass was greater than the root mass. As can also be seen, this trend was exaggerated in the white and red-light treatments, which had substantially less energy shares. This can underscore the significance of other factors such as IR wavelength in the root mass growth.

Figure 14 also shows that turnip leaf yields are high across all treatments regardless of wavelength of total PPFD. Red light produced extremely low root growth for both radishes and turnips, and while white outperformed both significantly for turnips, only the control produced significantly higher radish root yield.

The normalized values in

Figure 15 presents that red light produces a much higher fresh biomass of turnip leaf than radish, with little significant effect on other relationships, likely due in part to the elongating properties of red light [

10].

Representative images of the turnip plants produced by each light treatment are shown in

Figure 16. As can be seen in

Figure 16, the growth of the roots is substantially larger under full control light conditions, literally pulling out of the pots.

Similar results are evident in Figure 17 for radishes.

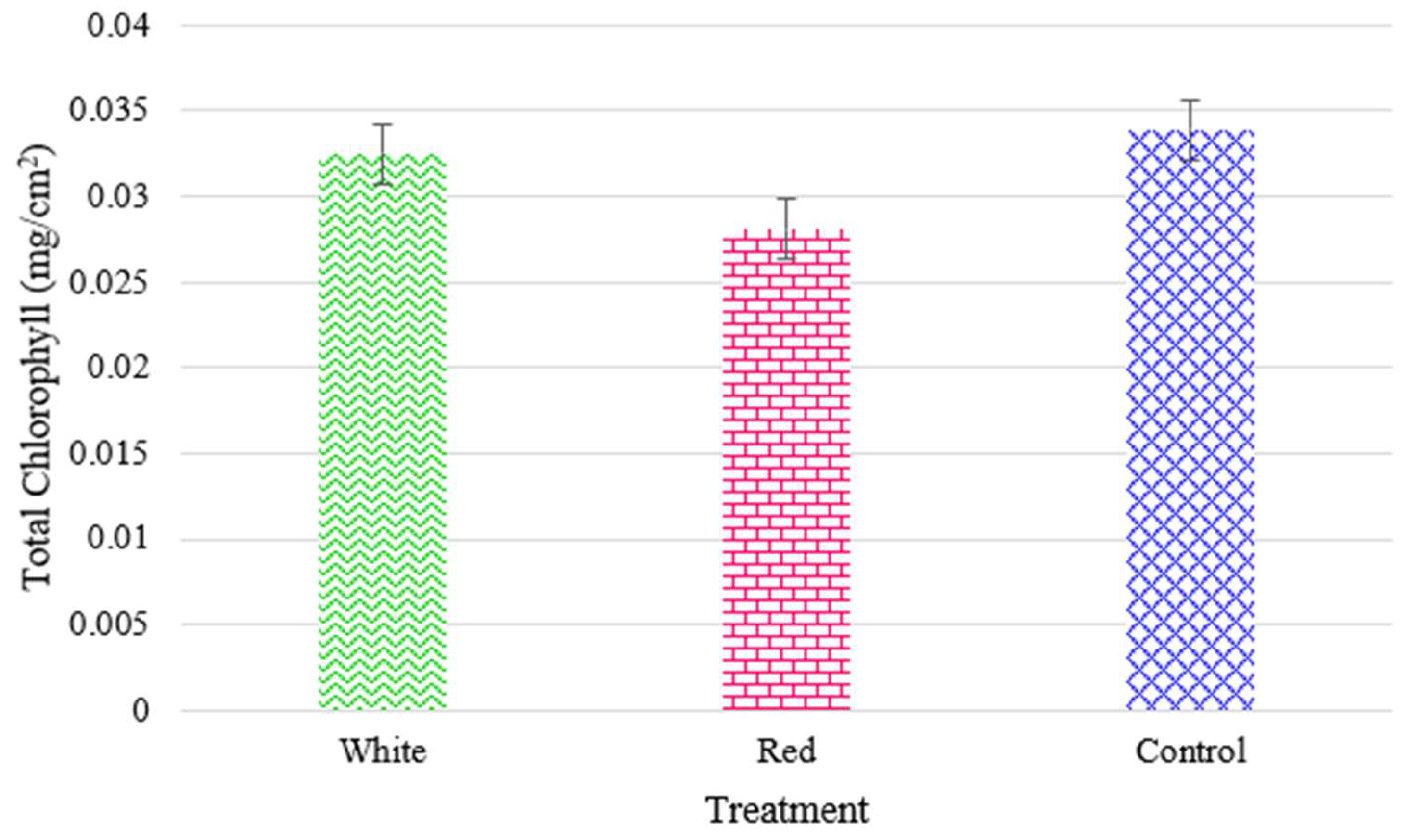

The outcomes can in part be explained by the results of the measured chlorophyll content for radishes (

Figure 18) and turnips (

Figure 19), respectively. The turnip chlorophyll content and yeilds were much higher with more proximate values (0.0138 to 0.0162 mg/cm

2) as the plants seem to have better adapted to the vertical CEA. For both cultivars, the positive impact of the white light in enhancing the total chlorophyll is observable.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have heavily investigated the impact of light on crops. There have been many studies on leafy vegetables (romaine [

18], spinach [

16,

19], chard [

20], red salad [

5,

21,

22], and kale [

23]) have all been covered in great detail. The results here are consistent, agreeing that leafy vegetables prefer a light quality ratio of 0.5-0.7 blue:red [

24]. Basil and tomatoes have also been well researched in horizontal systems; basil thrives with 70% red light [

25] and tomatoes similarly benefit from a full spectrum treatment [

14]. Radishes are a little different, and do well with higher red ratio [

7], though purely red light is known to produce a lower overall leaf mass [

26]. The results found here for a vertical system were consistent with the previous horizontal results on radishes. The yields were not particularly strong as was expected to be for an indoor vertical farming facility, and this could be due primarily to the grow walls being designed specifically for growing greens.

This study, however, provides the first spectral light study for turnips in the literature and the first true indoor vertical growing study. The turnip results were much stronger than those of the radishes both in terms of production of roots and leaves. Turnip leaves can be sold in bunches for anywhere from 80cȼ to

$2.99 per bunch [

27,

28], depending on the location. They are much often more expensive in northern states, as typically they are sourced from southern states [

29]. According to normalized values, red light produces a large biomass of leaves, however, to maximize profitability, a higher root value should also be considered as turnip roots can sell for around 43ȼ per 100g (current price at Walmart) [

29]. For radish light treatment experiments, the effect of white wavelength on the plant height, number of leaves, and chlorophyll (mostly green biomass indicators) was considerable according to the normalized energy data. It is worth noting that the control treatment does not vastly outperform the other treatments in either category, or in fact is less effective when values are normalized. Root yield of both turnip and radish, however, is higher under full spectrum conditions, even after normalization. In a low energy environment, stress can shift growth [

30] and plants may prioritize growing leaves to increase photosynthesis, causing roots to grow smaller (according to yield values in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

Further analysis is required to determine whether turnip leaf sales are profitable in a vertical layout or if they are better reserved for horizontal farming. If northern U.S. or Canadian farmers were able to start suppling this using the agrivoltaics agrotunnel or similar growing systems, not only would transportation costs be reduced but there would also be reductions in the environmental impacts. Full economic analysis on leafy greens has already been shown to be economic in such systems [

31] and there is some evidence that because consumers support agrivoltaics [

32] they may be willing to pay more for agrivoltaic crops [

33]. This is particularly interesting because this form of agrivoltaics where solar power is integrated to CEA would allow for year-round production of these root vegetables and their green leaves. Since turnip leaves grow so abundantly under reduced lighting, these could be produced with much lower energy use than other products, which again would decrease capital cost because it would allow for downsizing of the PV array.

French breakfast radishes, which are typically much smaller, grew much closer to typical commercial size than turnips. This is primarily due to the limited root area available in cups optimized for leafy green production. The variety of turnips planted is best harvested at a diameter of two inches, and as the pots of the wall are also two inches, it is not possible to grow ideal turnip roots in this setup. Much larger grow bins exist for this lighting system [

34]. It is possible, however, to have different sized ports on a grow wall and container design is well known to influence growth [

35]. To increase root growth, however, radishes only thrived under full spectrum lighting, so it would seem that the other treatments were not receiving enough light to increase the photosynthetic rate of the plant to produce stronger roots. Future work can repeat these experiments using higher intensity light of all three spectral ranges. It is worth noting that there is a significant difference for both turnip and radish root yield values between the white light and the control treatment. The addition of red and white light to control, though it contributes little total PPFD, still has an impact on growth factors allowing for higher photosynthetic rate and greater production.

Though true energy normalization cannot be achieved due to the multitudinous effects of multiple wavelengths on plant growth, the normalized results are meant to predict what may occur should these plants be grown under pure lighting conditions with equal PPFD. They show that the red-light treatment performs the best, especially in boosting the growth of the plants’ green parts. It is worth noting that very small amounts of white light were present in this treatment because the systems were not completely light tight (

Figure 4), so plants were receiving small amounts of all wavelengths which could also impact their scaled values. Additionally, controlling the photoperiod for the crops being grown would also save energy and can be targeted to maximize the growth. Although increasing the flux may be necessary for maintaining the optimal DLI, the required time period could be reduced. Reducing the light period down from 24 hours/day has been shown not to impact growth of some lettuces [

31], but additional work is needed to determine if this is also the case for turnips of radishes. Finally, for turnips there is already a call for a need to improve energy efficiency of its production to reduce carbon emissions [

36]. Further analysis is required to determine whether turnip leaf sales are profitable in a vertical layout and if this approach using agrivoltaics coupled to CEA would reduce the overall energy and emissions for cultivation. A full environmental life cycle analysis could be used to do this.

5. Conclusions

This is the first study to demonstrate that root vegetables including turnips and radishes could be successfully grown in an agrivoltaic agrotunnel using both lighting and grow walls optimized for cultivating the leafy greens and salads [

31]. As reductions in LED energy use is particularly important for agrivoltaic indoor vertical farming to minimize capital costs for PV modules, this study investigated the impacts of LED spectra on growth indicators of the studied cultivars. Both plants preferred more daily light integral or light intensity during the light operating hours than was available during 24 hours with the LEDs designed for leafy greens. The normalized values, however, showed that they preferred to receive more red light to increase their height and number of green leaves. In some other cases such as number of radish leaves and total chlorophyll, however, the positive effect of white light was indisputable. For both cultivars, the leaves provided higher crop masses than the roots, although turnips appeared to be far more adaptable to this approach than the radishes.

The results here show promise for providing true net zero energy root vegetables year-round even in northern climates with agrivoltaics agrotunnel or similar PV-powered CEA. Future work is needed to optimize the grow walls with larger ports to allow effective growth of these root vegetables and also other crops as well as further work with light intensity trials over the various wavelengths (e.g., including/excluding IR) to reach optimal light recipes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.P.; methodology, A.S., N.A. and J.M.P.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., N.A. and J.M.P.;; formal analysis, A.S., N.A. and J.M.P.;; investigation, A.S., N.A.; resources, J.M.P.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., N.A. and J.M.P.; writing—review and editing, A.S., N.A. and J.M.P.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, J.M.P.; project administration, J.M.P.; funding acquisition, J.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Thompson Endowment, Carbon Solutions @ Western, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEA |

Controlled Environment Agriculture |

| VF |

Vertical Farming |

| LED |

Light Emitting Diode |

| EC |

Electrical Conductivity |

| FSSC |

Food Security Structures Canada |

| PPFD |

Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

References

- Muller, A.; et al. Can soil-less crop production be a sustainable option for soil conservation and future agriculture? Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benke, K.; Tomkins, B. Future food-production systems: vertical farming and controlled-environment agriculture. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2017, 13, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, K.; et al. Effect of Supplemental Lighting from Different Light Sources on Growth and Yield of Strawberry. Environ. Control Biol. 2013, 51, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Basu, C.; Meinhardt-Wollweber, M.; Roth, B. LEDs for energy efficient greenhouse lighting,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajhi, A.A.; et al. The Effect of LED Light Spectra on the Growth, Yield and Nutritional Value of Red and Green Lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Plants 2023, 12, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, N.; Chung, J.-P. High-brightness LEDs—Energy efficient lighting sources and their potential in indoor plant cultivation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2175–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, L.; Liu, W. Effects of light quality, light intensity, and photoperiod on growth and yield of cherry radish grown under red plus blue LEDs. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2018, 59, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiamba, H.D.S.S.; et al. Enhancement of photosynthesis efficiency and yield of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa Duch. ) plants via LED systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 918038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olle, M.; Viršile, A. The effects of light-emitting diode lighting on greenhouse plant growth and quality. Agric. Food Sci. 2013, 22, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kubota, C. Effects of supplemental light quality on growth and phytochemicals of baby leaf lettuce. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, C.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Han, X. Effects of Different Light Sources on the Growth of Non-heading Chinese Cabbage (Brassica campestris L. ). J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 4, p262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johkan, M.; Shoji, K.; Goto, F.; Hahida, S.; Yoshihara, T. Effect of green light wavelength and intensity on photomorphogenesis and photosynthesis in Lactuca sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 75, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Amaki, W.; Watanabe, H. Effects of monochromatic light irradiation by led on the growth and anthocyanin contents in leaves of cabbage seedlings. Acta Hortic. 2011, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazaitytė, A.; et al. The effect of light-emitting diodes lighting on the growth of tomato transplants.

- Goto, E.; Matsumoto, H.; Ishigami, Y.; Hikosaka, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Yano, A. Measurements of the photosynthetic rates in vegetables under various qualities of light from light-emitting diodes. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1037, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, C.; Mattoni, B.; Bisegna, F. The Impact of Spectral Composition of White LEDs on Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) Growth and Development. Energies 2017, 10, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, N.; Jamil, U.; Pearce, J.M. Net Zero Agrivoltaic Arrays for Agrotunnel Vertical Growing Systems: Energy Analysis and System Sizing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loconsole, D.; Cocetta, G.; Santoro, P.; Ferrante, A. Optimization of LED Lighting and Quality Evaluation of Romaine Lettuce Grown in An Innovative Indoor Cultivation System. Sustainability 2019, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; et al. Effects of Light Intensity on Growth and Quality of Lettuce and Spinach Cultivars in a Plant Factory. Plants 2023, 12, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, L.P.; Coyle, S.D.; Bright, L.A.; Shultz, R.C.; Hager, J.V.; Tidwell, J.H. Comparison of Four Artificial Light Technologies for Indoor Aquaponic Production of Swiss Chard, BETA VULGARIS, and Kale, BRASSICA OLERACEA. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2018, 49, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anum, H.; Cheng, R.; Tong, Y. Improving plant growth, anthocyanin production and oxidative status of red lettuce (Lactuca sativa cv. Lolla Rossa) by optimizing red to blue light ratio with a constant green light fraction in a plant factory. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutte, G.W.; Edney, S.; Skerritt, T. Photoregulation of Bioprotectant Content of Red Leaf Lettuce with Light-emitting Diodes. HortScience 2009, 44, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefsrud, M.G.; Kopsell, D.A.; Sams, C.E. Irradiance from Distinct Wavelength Light-emitting Diodes Affect Secondary Metabolites in Kale. HortScience 2008, 43, 2243–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatistas, C.; Avgoustaki, D.D.; Monedas, G.; Bartzanas, T. The effect of different light wavelengths on the germination of lettuce, cabbage, spinach and arugula seeds in a controlled environment chamber. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 331, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, B.; Kowalski, A. The growth, photosynthetic parameters and nitrogen status of basil, coriander and oregano grown under different led light spectra. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2021, 20, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhov, N.G.; et al. Development of storage roots in radish (Raphanus sativus) plants as affected by light quality. J. Plant Physiol. 1996, 149, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wholesale Price of Turnip Tops Greens.

- Turnip Greens - 1 Bunch - safeway. Available online: https://www.safeway.com/shop/product-details.184400064.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Turnips, White, 1 kg, 1.00 - 1.00 KG - Walmart.ca. Available online: https://www.walmart.ca/en/ip/turnips-white/982055 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Dolferus, R. To Grow or Not to Grow: A Stressful Decision for Plants. Plant Science 2014, 229, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, N.; Basdeo, A.; Givans, J.; Pearce, J.M. Lighting and Revenue Analysis of Grow Lights in Agrivoltaic Agrotunnel for Lettuces and Swiss Chard 2025. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Pascaris, A.S.; Schelly, C.; Rouleau, M.; Pearce, J.M. Do Agrivoltaics Improve Public Support for Solar? A Survey on Perceptions, Preferences, and Priorities. GRN Tech Res Sustain 2022, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Nguyen, J.; Pearce, J.M. Determinants of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Agrivoltaic Produce: The Mediating Role of Trust 2024. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.-Y.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Indoor Horizontal Grow Structure Designs. Designs 2024, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, J.; Álvaro, J.E.; Urrestarazu, M. Container Design Affects Shoot and Root Growth of Vegetable Plant. HortScience 2020, 55, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshroo, A.; Izadikhah, M.; Emrouznejad, A. Improving Energy Efficiency Considering Reduction of CO2 Emission of Turnip Production: A Novel Data Envelopment Analysis Model with Undesirable Output Approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 187, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Curtain setup between walls with full spectrum light.

Figure 1.

Curtain setup between walls with full spectrum light.

Figure 2.

White-light treatment wall with curtains on either side.

Figure 2.

White-light treatment wall with curtains on either side.

Figure 3.

Irradiance as a function of wavelength for the spectral composition of white-light treatment.

Figure 3.

Irradiance as a function of wavelength for the spectral composition of white-light treatment.

Figure 4.

Irradiance as a function of wavelength for the spectral composition of red-light treatment.

Figure 4.

Irradiance as a function of wavelength for the spectral composition of red-light treatment.

Figure 5.

Irradiance as a function of wavelength for the spectral composition of full spectrum (control treatment).

Figure 5.

Irradiance as a function of wavelength for the spectral composition of full spectrum (control treatment).

Figure 6.

Turnip heights over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 6.

Turnip heights over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 7.

Turnip heights over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 7.

Turnip heights over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 8.

Radish heights over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 8.

Radish heights over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 9.

Radish heights over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 9.

Radish heights over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 10.

Number of turnip leaves over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 10.

Number of turnip leaves over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 11.

Number of turnip leaves over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 11.

Number of turnip leaves over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 12.

Number of radish leaves over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 12.

Number of radish leaves over eight weeks of growth.

Figure 13.

Number of radish leaves over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 13.

Number of radish leaves over eight weeks of growth (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 14.

Yield values for turnip and radish fresh root and green leaves grown under various light spectral treatments running for 24 hours during the eight-week cultivation period.

Figure 14.

Yield values for turnip and radish fresh root and green leaves grown under various light spectral treatments running for 24 hours during the eight-week cultivation period.

Figure 15.

Yield values for turnip and radish fresh root and green leaves grown under various light spectral treatments running for 24 hours during the eight-week cultivation period (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 15.

Yield values for turnip and radish fresh root and green leaves grown under various light spectral treatments running for 24 hours during the eight-week cultivation period (normalized energy from LEDs).

Figure 16.

Representative turnip plants produced by each light treatment: (a) red light condition, (b) white light condition, and (c) control light condition.

Figure 16.

Representative turnip plants produced by each light treatment: (a) red light condition, (b) white light condition, and (c) control light condition.

Figure 17.

Representative turnip plants produced by each light treatment: (a) red light condition, (b) white light condition, and (c) control light condition.

Figure 17.

Representative turnip plants produced by each light treatment: (a) red light condition, (b) white light condition, and (c) control light condition.

Figure 18.

The total chlorophyll for turnip shown for the three light treatments.

Figure 18.

The total chlorophyll for turnip shown for the three light treatments.

Figure 19.

The total chlorophyll for radish shown for the three light treatments.

Figure 19.

The total chlorophyll for radish shown for the three light treatments.

Table 1.

Total samples of each crop in each treatment.

Table 1.

Total samples of each crop in each treatment.

| Crop |

Red |

White |

Control |

Total |

| Turnip |

10 |

11 |

10 |

31 |

| Radish |

14 |

12 |

11 |

37 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).