1. Introduction

The social media age has fundamentally transformed the global knowledge ecology. The proliferation of digital information access and the development of social media platforms have dramatically altered how people search for, consume, and disseminate information. These transformations have significantly influenced genealogy - the study of family lineage - which has emerged as a widespread practice attracting millions of practitioners globally who seek to reconstruct their familial narratives (

Davison, 2009).

Historically, genealogical research was limited to professional historians and privileged families (

Willever-Farr, 2017). Researchers were required to undertake costly expeditions to distant archives to examine primary documents, making such research too expensive to afford. The digital revolution has fundamentally restructured this paradigm: The emergence of digital databases, commercial genealogical platforms, and DNA analysis technologies has democratized genealogical research by making it both accessible and affordable for people of all walks of life (Liew et al., 2022). Simultaneously, social media platforms have facilitated the development of online communities dedicated to genealogical research (

Charpentier and Gallic, 2020).

Based on interviews with 15 Facebook community managers, the research demonstrates that such communities function as significant knowledge hubs, facilitating information exchange’ and the construction of collective knowledge.

These communities are coordinated by managers who integrate technological expertise, historical scholarship, and information management competencies. Their function assumes particular significance in communities that have endured historical trauma. These managers transcend the role of mere data brokers; they serve as custodians of collective memory, facilitating the restoration and preservation of familial and communal heritage.

This research explores the function of online genealogical communities as knowledge hubs. Furthermore, it analyzes community managers as critical mediators of knowledge, examining their self-perception and their perceived reception by community members. Through this research, the study aims to elucidate how these communities and their managers take a primary role within contemporary genealogical information ecology.

2. Literature Review

The literature review examines the evolution of genealogy and the transformations in its information ecology across three centuries, with particular emphasis on the substantial developments of the past three decades.

The term “genealogy” derives from the conjunction of two Greek words: genea, signifying “generation” or “family”, and logos, denoting “knowledge” or “study” (

Online Etymology Dictionary, 2023). The term shares etymological roots with related concepts including Genesis, Genetics, Generation, Genome, Generator, and Gender, underscoring its fundamental connection to origins, development, and heredity.

Genealogy constitutes a field of systematic research of families, their histories, and their lineages, wherein individuals with shared interests or cultural backgrounds collaborate to achieve optimal outcomes (

Yakel, 2004). The genealogical process encompasses root discovery and lineage tracing through documentary analysis. This process synthesizes historical, social, communal, geographical, and cultural information, transforming empirical findings into coherent biographical narratives.

Genealogical research facilitates comprehensive understanding of ancestral origins and lifestyles, functions to preserve ethnic traditions and family culture for subsequent generations and currently contributes to understanding familial medical histories while validating or challenging family narratives to preserve historical, cultural, communal and social heritage.

2.1. Vygotsky’s Theory of Knowledge Co-Creation

This research is grounded in the theory of knowledge co-creation, originating from Lev Vygotsky’s seminal work. Vygotsky’s theoretical framework on collaborative knowledge creation supports his sociocultural theory, which proposes that cognitive development is fundamentally social and collaborative in nature (Vygotsky, 1978). He contends that higher psychological functions emerge from social interactions rather than individual processes and are internalized through cultural mediation. Vygotsky emphasizes that learning manifests within social contexts, where dialogic exchange and interpersonal cooperation assume key roles in shaping individual cognition and intellectual capabilities.

A fundamental construct introduced by Vygotsky is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which elucidates the learning potential actualized when learners interact with more knowledgeable peers (Vygotsky, 1997). Moreover, Vygotsky accentuates the cultural-historical context of learning, thereby reinforcing the conceptualization of collaborative knowledge creation. He maintains that cultural tools, particularly language, function as essential mediators of social interaction and knowledge generation (Veer and IJzendoorn, 1985). This theoretical perspective aligns with the understanding that learning transcends isolated cognitive processes, representing instead a dynamic interplay between individuals and their cultural environment, wherein shared experiences and collaborative endeavors facilitate deeper comprehension (

Veresov and Kulikovskaya, 2015).

Although Vygotsky formulated his theory well before the advent of internet technologies and digital platforms, he precisely identified and characterized social learning processes that manifest in contemporary online communities. His theoretical framework on collaborative knowledge creation, emphasizing social interaction and collaborative learning, demonstrates particular relevance to online community dynamics. His conceptualization of cognitive development as a social process underscores the significance of learner interaction, now facilitated through social media platforms. The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) construct illuminates how learners achieve enhanced understanding through engagement with more knowledgeable peers in collaborative contexts. Within online learning environments, this theoretical framework manifests in collaborative task execution that promotes peer interaction and problem-solving through technological mediation (

Durrington and Du, 2013).

2.2. Development of Genealogical Information Ecology

Genealogy, family history research, representing the most ancient branch of historical inquiry, originated with lineage documentation in biblical texts and persisted as a traditional pursuit across millennia, primarily through written records and physical documentation (

Davison, 2009).

By the eighteenth century, genealogical research had evolved into an aristocratic pursuit, primarily due to the substantial financial resources required to fund research demanding specialized expertise (

Willever-Farr, 2017). The economic and professional constraints became increasingly pronounced in the pre-digital twentieth century, as the expansion of international research necessitated physical presence in global archives, comprehensive understanding of diverse archival systems, and mastery of sophisticated search methodologies. The substantial financial burden associated with archive visitation and professional consultation continued to restrict access to this field (

Willever-Farr, 2017).

Public engagement with genealogical research intensified significantly during the 1970s, though throughout approximately the next twenty-five years, genealogists remained dependent upon physical archives, correspondence-based inquiries, and direct archival research. In the pre-internet era, knowledge co-creation relied upon traditional mechanisms such as interpersonal encounters, academic conferences, and institutional collaborations (Wenger, 1998). However, this paradigm encountered substantial limitations: geographical boundaries and physical constraints impeded information access and collaborative opportunities. Traditional knowledge dissemination operated within hierarchical frameworks, restricting interactive discourse and feedback. Moreover, the dissemination process proceeded at a slower pace, relying predominantly on print publications and academic periodicals (Wenger, 1998).

Interest escalated remarkably at the millennium’s dawn with internet proliferation, transforming the field into a robust commercial sector (

Davison, 2009). The 2009 emergence of platforms like Ancestry.com initiated the transition from traditional archival and library-based research to online services, despite lacking the sophisticated digital tools characteristic of contemporary practice, such as social networks and specialized mobile applications

.

The digital transition has inaugurated unprecedented possibilities for genealogical research, enhancing both accessibility and efficiency. Genealogy has transformed from an elitist pursuit into a “serious leisure activity” (

Fulton, 2016), motivated by diverse imperatives ranging from self-discovery to intellectual stimulation (

Moore and Rosenthal, 2021).

The web transition prompted individuals to utilize software platforms and websites for family tree construction based on available data. Subsequently, genealogical communities emerged, initially communicating through chat rooms and later via email distribution networks (

Fulton, 2009). Contemporary online genealogical communities differ fundamentally from their predecessors, having evolved from basic communication platforms into sophisticated research environments and becoming integral to modern genealogical research

.

While basic internet searches persist, many researchers now prioritize online communities as primary information sources. These communities not only reveal previously inaccessible databases and facilitate access to visual and textual artifacts but also enable productive collaboration among “memory workers” - the investigating amateur genealogists (

Stein, 2009). The lack of formal records, coupled with heightened interest in cultural heritage, drives market evolution. Genealogical service providers employ diverse investigative methodologies, including DNA genetic analysis and interviews, to accumulate substantive familial information

.

These technological advancements are fundamentally restructuring methodologies for family history research and ancestral connection. Contemporary digital platforms and tools have increased the accessibility of genealogical research.

2.3. Modern Genealogical Information Ecology

The digital revolution has fundamentally transformed not only the accessibility of genealogical information but has engendered an entirely novel ecosystem of methodological tools, resources, and investigative approaches. The contemporary genealogical information ecology is characterized by an extensive array of digital resources available to researchers. Advanced technologies for information access, preservation, and enhancement of familial comprehension encompass comprehensive access to historical documentation through digital hubs and archives. These platforms facilitate the exploration of diverse records, including census data, historical periodicals, military documentation, testamentary documents, and immigration records, thereby optimizing and enriching ancestral research processes (

Pugh, 2017). Supplementary resources comprise yearbooks, telephone directories, cemetery records, immigration certificates and more.

Digital family trees have emerged as fundamental collaborative instruments, facilitating the generation, modification, and dissemination of genealogical data. Web platforms integrate sophisticated technologies such as “smart matches” that facilitate familial connection discovery and enrich family tree information (Kaplanis et al., 2018). Certain platforms offer genealogical education, photographic enhancement and animation technologies like “deep storytelling technologies”, enabling historical photographic subjects to narratively convey their experiences (

Family Search, 2023).

Geographical information systems and cartographic technologies have substantially enhanced the capacity to comprehend familial migration patterns and analyze geographical influences on historical events. These instruments provide comprehensive contextual frameworks, enriching familial research and establishing connections between local and communal histories within individual family narratives (

Timothy and Guelke, 2016).

DNA tests for genetic analysis contributes an additional dimension to genealogical research, enabling researchers to trace genetic origins, verify familial connections, and identify previously unknown relatives. These analyses facilitate the examination of migration patterns, ancestral origins, and genetic development across generations, enriching research methodologies (

Duster, 2016).

Concurrently, digital collaborative platforms have revolutionized communal approaches to genealogical research. These communities facilitate the exchange of insights, methodological tools, and expertise, enabling the resolution of genealogical complexities and the synthesis of fragmented information (

Charpentier and Gallic, 2020). Digital platforms enable the preservation of family histories, photographic materials, and community documentation while ensuring intergenerational accessibility. Thus, digital preservation establishes research continuity and unprecedented information accessibility (Liew et al., 2022).

The genealogical products and services market was projected to attain

$4.66 billion in 2024 and

$10.10 billion by 2031 (

Verified Market Research, 2022), demonstrating a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.19% during the 2024-2031 forecast period.

As of August 2023, SimilarWeb analytics indicate Ancestry.com as the preeminent genealogy platform, with average visit durations of 14 minutes and 26 page views. Familysearch.org demonstrates average engagements of 15 minutes and 24 page views per visit, while MyHeritage.com records averages of 6 minutes and 10 pages per visit. According to Edwards (2022), Ancestry maintains over 3 million subscribers, 20 million DNA samples, and 20 billion records; MyHeritage, accessible in 42 languages, serves 96 million users, manages 16.1 billion records, 49 million family trees, and 8.3 million DNA analyses; and Geni encompasses 250 million profiles from 15 million users.

These metrics indicate the field’s evolution from a specialized pursuit to a robust market and widespread engagement phenomenon, attracting millions of practitioners and generating substantial revenue. Beyond commercial considerations, it maintains its attractiveness, relevance, and significance for individuals pursuing familial historical documentation.

This research expands the comprehension of contemporary genealogical information ecology by identifying and defining two emergent constituents: online communities and their managers, who collectively establish a significant knowledge hub within the current genealogical landscape. While current research has predominantly focused on digital databases and commercial platforms, the findings indicate that online communities and their managership have become integral components of genealogical information ecology, providing not only information access but also frameworks for collaborative knowledge generation and enhanced understanding of historical and cultural contexts.

2.4. Social Media and Genealogy

Social networks and digital platforms have established a novel paradigm that challenges traditional knowledge hubs, such as archives and professional expertise (

Golan and Martini, 2020). Alongside websites, digital databases and electronic archives, collaborative platforms have developed to help people connect with each other and work together to solve complex genealogical challenges (

Charpentier and Gallic, 2020).

Social media has emerged as a pivotal and significant instrument, superseding websites and databases that have rapidly become conventional and antiquated. Contemporary online communities constitute essential spaces for information retrieval and dissemination across diverse domains (

Lewis et al., 2018). Their significance derives from multiple factors: they aggregate members with heterogeneous backgrounds and experiences, enriching the collective knowledge hub, providing enhanced information accessibility unrestricted by temporal or spatial constraints, and ensuring information immediacy and relevance. In the context of online communities, by 2021, Facebook alone hosted more than 16,700 genealogy-focused groups (Vita Brevis, 2023).

Within the complex genealogical ecosystem, online community managers assume an essential role in bridging the divide between digital information and users, contributing substantively to the development of communities as significant knowledge hubs. The prevailing perspective is that social media functions as an arena of egalitarian interactions generating collective knowledge. However, reality presents greater complexity. Research demonstrates that the majority of online community members are “lurkers”, engaging passively, while a limited cohort - led by community managers - constitutes the primary content generators (Author). Consequently, online communities must be conceptualized as environments based on interactions between members and managers, and on the collaborative knowledge generated through such interaction, rather than merely platforms for user-generated content. The managers’ roles as knowledge hubs and gatekeepers are fundamental to community dynamics.

Panteli (2016) identified key managership paradigms related to knowledge sharing, particularly emphasizing knowledge transfer and facilitation of discussions. Beyond technical administration, managers’ role encompasses value addition through information and knowledge dissemination. Managers function as central nodes for discussion initiation, query resolution, and information source direction. Research across various domains demonstrates that online community managers evolve into central knowledge hubs (Author). They facilitate connections among members with shared interests and assist in refining information requirements through mediative expertise (Lueg, 2008).

Managers significantly influence community social structure and knowledge dissemination patterns, potentially creating “distortions” in typical interaction paradigms that may deviate from characteristic social network “power law” distributions (

Cottica et al., 2017). They encourage enhanced participation from less active users, thereby transforming network dynamics and amplifying knowledge flow.

As central hubs in online community dynamics, managers serve as critical knowledge and information intersections. They guide community discourse and establish content parameters, thereby maintaining information quality and relevance (

Amann and Rubinelli, 2017). In their gatekeeper capacity, they monitor information quality to ensure adherence to community standards.

The centrality of managers in social media communities encompasses content production, initiative, discussion contribution, and information provision. They function as knowledge and information hubs-soliciting and providing information (Author), contributing (

Agarwal and Toshniwal, 2020), creating and sharing (

Gal et al., 2023), managing knowledge (

Huffaker, 2010), and promoting motivation and knowledge transmission (

Mustapha, 2018). As knowledge experts, they respond to and encourage engagement (

Lee et al., 2019), reflecting prosocial orientation (

Jadin et al., 2013). They establish and maintain knowledge managership status through digital platforms (

Golan and Martini, 2020).

The central role of community managers in knowledge production and management reflects a broader shift in authority structures within social networks. Social networks demonstrate a transition from traditional hierarchical authority to more distributed authority based on social media presence and activity (

Golan and Martini, 2020).

Based on these changes in knowledge sharing patterns, this study examines how online genealogical communities and their managers function as knowledge hubs within the broader genealogical information ecology. The research examines how these communities, under the guidance of their managers, serve as spaces where genealogical knowledge is created, shared, and refined through member interactions. This suggests that these online communities have evolved into essential hubs in the genealogical information landscape, where both practical research expertise and theoretical genealogical knowledge converge and develop through the facilitation of community managers.

Just as Instagram enables direct connection between managers and their followers, evident when politicians share personal updates and daily life videos while bypassing traditional media, online communities similarly facilitate direct contact between information seekers and community managers without traditional institutional mediation (

Golan and Martini, 2020). Community managers promote connections between members with shared interests and help users understand and refine their information needs.

Given their role, community managers employ various tools and strategies to enhance their knowledge dissemination effectiveness. The use of technological tools for data management, online communication, and content creation enables more efficient information flow management (

Tohani et al., 2023). Additionally, they develop strategies to improve information quality and combat misinformation (

Rohman, 2020).

This research explores the role of genealogy community managers in social media as central knowledge hubs for preserving and making accessible family and community history. Despite social media’s growing importance in family history research, there has been no comprehensive study examining how community managers function as knowledge hubs: leading the processes of collecting, documenting, and preserving genealogical knowledge, while helping community members reconstruct their family narratives and the social fabric of their historical communities.

Online communities typically feature several knowledge experts who serve as knowledge hubs. It is neither self-evident nor necessary that community managers become the central knowledge hubs beyond their organizational and administrative duties (Author). Establishing the community or holding a formal management role does not automatically grant content expertise status; such expertise is built through significant contributions to discourse and the shared knowledge base. This phenomenon is particularly prominent in genealogy communities, where community managers typically serve as knowledge hubs.

Fulton (2009) studied online genealogy community managers and identified their significant influence, describing them as “super-participants” or “information champions”. According to her research, these dedicated individuals are central contributors to the genealogical community. Their involvement typically begins with a defining event, leads to thorough data collection, continues with searching for breakthroughs and constructing complex family trees, and culminates in publishing and preserving the collected information.

However, it is crucial to note that Fulton’s 2009 study reflects a vastly different technological landscape from today’s reality. The research was based on then-available technology, primarily email distribution lists. Study participants had to rely on limited, primitive digital databases that were hardly user-friendly, and cumbersome software for building family trees.

Currently, genealogical information ecology has evolved significantly, thanks to the integration of advanced technologies and new competencies. The substantial change in dynamics since Fulton’s (2009) study over a decade and a half ago emphasizes the need for updated research on the role, practices, and impact of genealogical community managers in the social media age.

3. Research Questions

The research primary objective is to examine the role of online genealogical communities as knowledge hubs and the vital cognitive position of their managers. This research imperative emerges from a significant lacuna: while online communities and their managers have been identified as responsible for technical and social managership, their specific contributions within the genealogical ecosystem remain insufficiently examined.

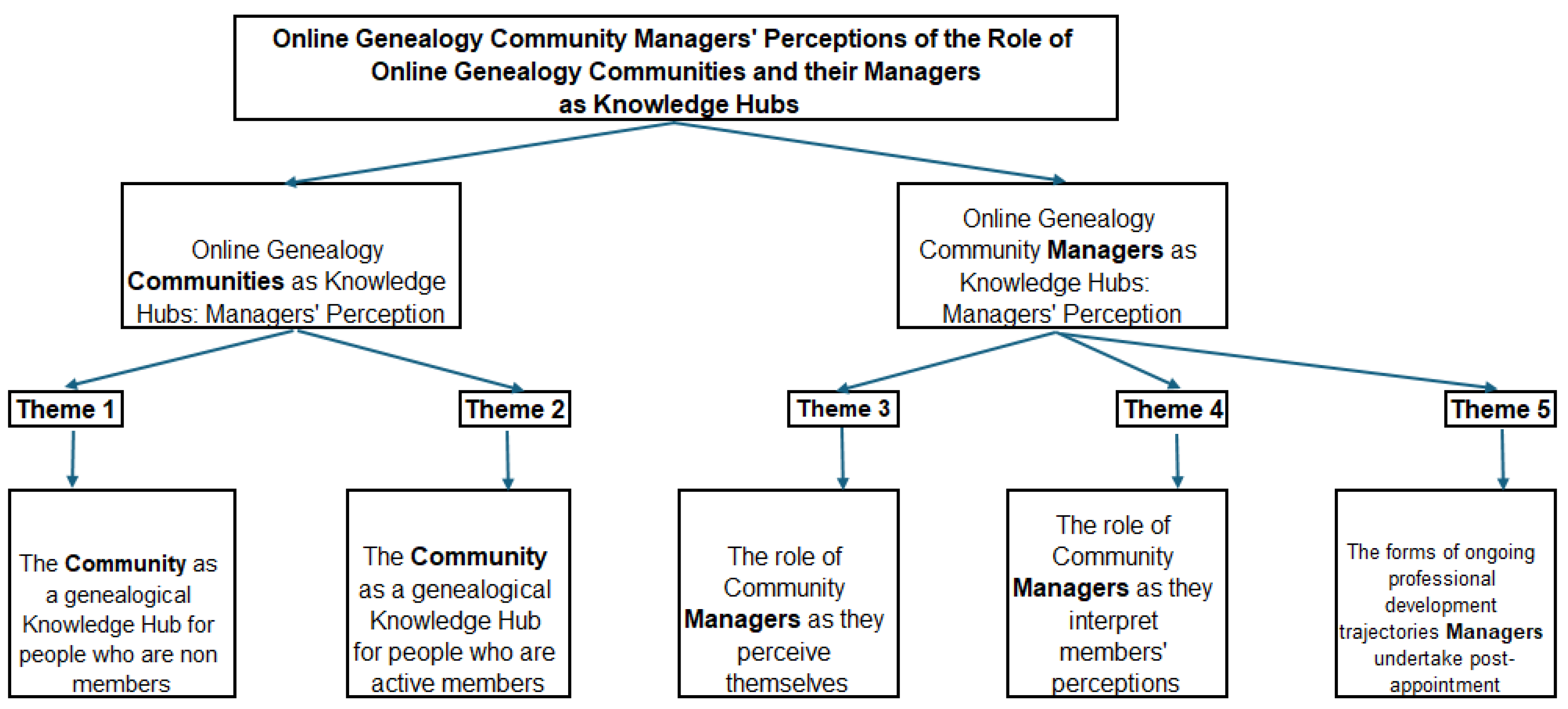

To address this gap, five research questions have been formulated, focusing on understanding community managers’ perceptions of the community’s role and their own function as knowledge hubs. The first two research questions examine the position of online communities as knowledge hubs for both community members and non-members, while the following three questions examine the position of online community managers as knowledge hubs.

3.1. Online Communities as Knowledge Hubs: Community Managers’ Perspective

What is the position of online communities within the genealogical knowledge ecology for individuals who are not community members but are seeking relevant information as community managers view it?

What position do online communities occupy in the knowledge ecology from the perspective of their active members as community managers view it?

The next three questions address the position of genealogical community managers as knowledge centers in their respective communities as they view it.

3.2. Online Community Managers as Knowledge Hubs: Community Managers’ Perspective

How do community managers interpret their role and significance within the genealogical information ecology?

How do community managers interpret community members’ perceptions of their role and significance?

What forms of ongoing professional development trajectories do managers undertake post-appointment?

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Population

The study participants are managers of diverse online genealogical communities, overseeing Facebook groups that engage thousands of members. While some approach genealogy as a hobby, these managers undertake self-directed professional development and possess significant expertise in the field. The study encompassed fifteen managers from Jewish communities spanning global locations including Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Morocco, South Africa, Australia, Poland, Germany, Romania, Slovakia, the former Soviet Union, Rhodes, India, Argentina, and the United States. These communities represent both extinct historical communities now administered by descendants and active contemporary ones, either in their original locations or new settings.

The research focused on understanding community managers’ perceptions of their role and their communities’ function as knowledge hubs, as they occupy a unique position at the intersection of community administration and knowledge management. Selected communities met rigorous criteria, including minimum membership of one thousand individuals and sustained contemporary activity of at least five monthly posts. The participant demographics showed a two-thirds male majority, with most managers being over 60 years old and the remainder between 36 and 50 years of age.

4.2. Data Collection

The research instrument evolved through systematic development, initiating with review of questionnaires from previous studies examining community manager characteristics, attributes, and motivations in social media contexts (Author;

Eitan and Gazit, 2023). Subsequently, questions were adapted for the target population of online genealogical community managers. Following preliminary exploratory interviews and six comprehensive interviews, emergent patterns informed questionnaire refinement.

Data collection proceeded through in-depth interviews averaging approximately one hour in duration. Some interviews were conducted in person, while those around the world were carried out via zoom meetings. Both were digitally recorded. Methodological rigor was maintained through consistent redirection to research questions when responses diverged, ensuring focused data collection while preserving rich informational depth.

All interviews underwent digital recording and software-assisted transcription. After identifying relevant communities, managers were recruited through snowball sampling and contacted via Facebook Messenger with standardized research participation invitations. When direct messaging attempts were unsuccessful, recruitment was expanded through public posts in the relevant communities.

4.3. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis followed systematic, structured protocols. Initial familiarization with material proceeded through iterative transcript review and preliminary notation. Initial coding identified meaningful textual units with appropriate code designation. The third phase involved preliminary code aggregation into potential themes, followed by relationship examination between themes and the comprehensive data set. The fifth phase encompassed theme essence refinement and precise definition, culminating in representative quote selection and coherent findings presentation.

Throughout analysis, responses to each inquiry were aggregated to identify recurring patterns, with attention to emergent topics from initial interviews, including follow-up with original participants for comprehensive understanding. Analysis reliability was ensured through independent coding cross-validation between two researchers, with collaborative discussion to achieve consensus on central themes. Thematic analysis revealed five central themes: two addressing online community knowledge hub function for members and non-members, and three examining manager self-perception of their role, community perception as they interpret it, and knowledge hub strategies they pursue.

4.4. Ethics

The research, receiving university Ethics Committee approval, incorporated comprehensive ethical considerations. All participants received detailed research objective explanations and provided signed or zoom recorded informed consent. Privacy protection involved numerical and alphabetical substitution for participant and community identifiers respectively, with explicit withdrawal rights communication. Research materials were secured with restricted researcher access.

5. Findings

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the analysis of interviews revealed five predominant themes. The themes emerged from analysis of managers’ interviews and solely reflect their own subjective perceptions and understanding of their role and the community’s function as knowledge hubs. The initial two themes examine the community’s function as a knowledge hub according to managers’ perception, addressing both non-member and active participant engagement. The subsequent three themes explore the community manager’s role, analyzing their interpretation of how they perceive their positioning within the genealogical information ecology, community members view their role, and the forms of ongoing professional development trajectories managers undertake post-appointment, to reinforce position as knowledge hubs.

The following analysis presents the managers’ perspectives and perceptions of their communities’ and their own roles as knowledge hubs. It is important to note that these findings reflect the subjective viewpoints of the managers interviewed, while other stakeholders may perceive these aspects differently.

5.1. Theme 1: Online Genealogy Communities as Knowledge Hubs for Non-Members: Managers’ Perspective

Interview analysis reveals distinct pathways in genealogical information acquisition, with information seekers typically utilizing several primary channels. As Interviewee 8 articulates, “Most individuals initially seek familial sources of information, frequently an elder with preserved memories... Subsequently, they pursue institutional databases such as the Diaspora Museum.

Following exhaustion of primary familial sources, digital search engines, particularly Google, become the predominant channel. This pattern is exemplified by Interviewee 3: “Information seekers predominantly arrive through Google searches. Those investigating Jewish community information invariably discover my platform.

However, while search engines function as initial access points, over half of participants emphasize online communities’ distinctive value proposition. As Interviewee 12 elucidates: “Contemporary information seekers gravitate toward communities due to their interconnected nature. While websites facilitate specific terminological searches, they cannot provide contextual frameworks, narrative associations, or familial connections. Communities provide comprehensive contextual understanding”.

Moreover, online communities’ efficacy manifests in their emergence as primary information acquisition channels. Approximately 40% of participants emphasize this transformation, with Interviewee 13 noting, “Within our ethnic demographic, our Facebook community has become the preliminary resource for information seekers”.

5.2. Theme 2: Online Genealogy Communities as Knowledge Hubs for Active Members: Managers’ Perspective

While the previous theme examined information seeker access patterns, this theme investigates the community’s function as a primary knowledge source for active participants. All managers report that post-membership, the community becomes members’ principal information resource. Interviewee 3 articulates this transformation:

The online community facilitates memory, visual, and narrative sharing, demonstrating superior efficiency compared to traditional newsletters. According to managers interviewed, members recognize its capacity for inquiry submission, document interpretation assistance, and location-specific research, acknowledging its unparalleled knowledge concentration in their domain of interest.

Community engagement encompasses diverse educational and investigative practices, as Interviewee 5 emphasizes: “Community participants engage through inquiries, seek document interpretation assistance, and utilize digital hubs and historical archives recommended within the group, trusting in the community’s capacity to provide authoritative and definitive information”.

Furthermore, collaborative learning dynamics emerge within the community, as described by Interviewee 7: “Members engage in mutual assistance regarding documentation and complex queries. The sustained discourse facilitates collaboration and collective knowledge preservation”.

The community’s significance is particularly emphasized by Interviewee 11, highlighting its contribution to familial historical reconstruction: “Our platform facilitates the reconnection of long-severed familial connections. In our historical community of 2000-3000 Jewish residents over four centuries, universal interconnection existed. The online platform enables the restoration of these historical connections.

5.3. Theme 3: Genealogy Online Community Managers as Knowledge Hubs: Managers’ Self-Perception

Following examination of the community’s function as a knowledge hub, analysis focuses on manager role conceptualization, particularly self-perception and functional interpretation. Findings reveal diverse self-conceptualizations ranging from comprehensive expertise claims to pronounced humility.

Approximately 50% of participants present themselves as knowledge hubs. Interviewee 2 self-identifies as “the authoritative source” and “preeminent global expert regarding their community’s Jewish population. This position is echoed by Interviewee 9: “Individual consultation requests reflect recognition of comprehensive and precise response capability. Extensive field experience engenders member trust”.

A significant emergent theme encompasses responsibility for communal heritage preservation. Interviewee 8 emphasizes interaction management importance: “Facilitating interactions demands substantial responsibility, ensuring universal recognition and narrative acknowledgment”. Furthermore, Interviewee 10 articulates clear strategic vision: “The objective is establishing the world’s predominant information hub for regional Jewish communities. While current positioning appears optimal, the challenge involves meaningful material utilization”.

5.4. Theme 4: Genealogy Online Community Managers as Knowledge Hubs: Managers’ Interpretation of Community Members Perceptions

After examining how managers conceptualize their own role, this section analyzes how they believe community members perceive them. These findings derive exclusively from managers’ self-reported perceptions of how community members view them, as direct examination of member attitudes exceeded study parameters.

Interview analysis indicates universal manager perception of significant community standing. Interviewee 9 states: “Members anticipate contributions and discussion participation. Substantial investment in ancestral documentation generates universal appreciation for voluntary contribution”. Similarly, Interviewee 6 describes member attitudes: “Members regard me as authoritative source, anticipating publications, responding enthusiastically to content, and regularly seeking specific consultation”.

Manager status manifestation extends beyond content anticipation to professional authority recognition, as Interviewee 11 notes: “I am acknowledged as the community’s authoritative source. Members frequently express, ‘Your contributions have illuminated previously undocumented aspects.’ Recognition and commendation are frequent”.

Approximately 80% of managers interviewed report the substantial responsibility accompanying their position. Interviewee 8 emphasizes: “Heritage preservation responsibility resides with the community rather than institutional bodies”. Community narrative preservation represents an internal obligation.

Some managers present nuanced role interpretations, exemplified by Interviewee 10: “My function transcends managership to encompass guidance. Member consultation carries the significant responsibility of facilitating access to factual information and technological resources”.

The managers’ status is reflected not only in content expectations but also in recognition of their professional authority, as Interviewee 11 attests: “I’m considered the ultimate authority on my community. Community members note that ‘it’s all thanks to you! Nobody knew, nothing was written, and we finally see.’ I receive abundant appreciation and praise”.

Alongside status recognition, approximately 80% of managers emphasize the heavy sense of responsibility accompanying their role. For instance, Interviewee 8 emphasizes: “The responsibility for preserving heritage lies with us, and we cannot expect a country or institutions to do it for us. It’s each community’s duty to preserve its own story”.

Finally, some managers present a more balanced approach to their role, as reflected in Interviewee 10’s words: “I see myself not just as a manager, but as someone who guides the way. When group members approach me, I feel it’s a great responsibility to be the factor that leads them to truth and technology”.

5.5. Theme 5: Forms of Ongoing Professional Development Trajectories Managers Undertake Post-Appointment

Following examination of managers’ self-perceptions and how the community perceives them, this theme focuses on translating these perceptions into practical actions. Analysis of the interviews reveals that all managers, before but increasingly after assuming community manager roles, invest considerable efforts, at varying levels of commitment, in deepening their knowledge and capabilities across six main domains.

First, in the domain of self-learning and research, approximately 90% of managers emphasize the importance of continuous learning. As Interviewee 14 describes: “I am autodidactic. I read extensively and rarely need a formal educational framework to develop expertise in a specific subject.” Similarly, Interviewee 3 notes: “I acquired all my genealogical knowledge through self-learning, through intensive research and connections with key community members”.

This commitment to research and learning is also reflected in significant resource investment, as Interviewee 2 describes: “I made 20-30 trips to my community’s country, invested millions in documentation and research... I conducted comprehensive research in archives and the national library.” Interviewee 6 adds: “I frequently read and search for information online... I’m interested in personal and family stories, researching in digital archives”.

Second, in the domain of documentation and preservation, approximately 90% of managers conduct extensive activities. Interviewee 3 describes: “I photographed all the tombstones in Jewish cemeteries in my community’s geographical location... I interview people and document their stories... I collected historical books and materials.” Similar investment is described by Interviewee 7: “Through JewishGen, we found ourselves as a group of amateur researchers and decided to try photographing all our city’s documents... For three years, we scanned and photographed all the documents”. Interviewee 8 emphasizes the importance of preservation: “The group isn’t just for finding connections. It’s meant to preserve heritage”.

In the third domain, event and activity organization, managers initiate a wide range of activities. For example, Interviewee 5 elaborates: “Our community has an annual calendar of events throughout the year. I organize social gatherings, holiday celebrations, memorial ceremonies, and I’ve also initiated and facilitated Zoom courses on genealogical research skills for community members”. This diverse activity is also reflected in Interviewee 3’s remarks: “About seven years ago, we held a major gathering attended by around 400 people... including X - a very important public figure in Israel who was born in (country)... I also organized meetings in (city) and Zoom conferences attended by about 300 people”. Interviewee 12 adds: “I initiated a physical event... with (community-specific) games and brought an interesting lecture... There was also a culinary gathering”.

In the fourth domain, collaborations and mutual learning, extensive activity occurs across all communities. Interviewee 4 describes: “I learn tremendously from senior board members who have been in the field for decades. They teach me about genealogy, and I teach them about technology”. These collaborations extend to research institutions, as Interviewee 5 describes: “We work with local historians and locals who have taken it upon themselves to assist and research Jewish topics (in the region)”. Interviewee 3 adds: “I maintain contact with Center X at Y University and with the Jewish museum there”.

In the fifth domain, development of unique skills, approximately 80% of managers acquire specific competencies required for their communities. Interviewee 14 provides translation services: “Some have their parents’ ID cards in (language). They ask me to translate the dates for them, as (country) has its own calendar”. Interviewee 5 describes acquired technological skills: “I taught myself to develop interactive maps, upload scanned books to shared drives, perform digitization”. Interviewee 1 adds: “I studied areas like museology and curation”.

Finally, in the domain of long-term commitment, sustained investment in knowledge deepening is evident in at least 80% of managers. As Interviewee 14 describes: “For the past five years, I’ve invested all my energy and time in studying and researching the history and culture (of the country). I’ve already written five books on these subjects”. This commitment is also reflected in managers’ impressive tenure, as evidenced by Interviewee 3: “I’ve been involved in documentation for 25 years, including creating a website and Facebook group to preserve heritage”, and Interviewee 9, who dedicated “over 40 years to documenting the stories of my community members”.

It is important to note that all these domains do not operate in isolation but maintain complex interrelationships, reinforcing the managers’ role as knowledge hubs and gatekeepers of community heritage.

6. Discussion

This research examined the roles of online communities and their managers as knowledge hubs in the genealogical ecosystem, as perceived by the managers themselves. While millions of people engage in family history research through online communities, little is known about how these communities and their managers function as knowledge hubs in the genealogical ecosystem, particularly from the managers’ perspective. This study specifically aimed to examine the position of these communities within the field’s knowledge ecology and their managers’ role, drawing on insights from other domains about the centrality of community management.

Through interviews with fifteen diverse Facebook genealogy community managers, the study revealed five key themes describing how managers understand these knowledge hub functions: the first two themes illuminate how communities serve as knowledge hubs for both non-members and active participants, while the remaining three themes explore managers’ perceptions of their own role as knowledge hubs, including their self-perception, their interpretation of community members’ perceptions, and the forms of ongoing professional development trajectories they undertake post-appointment for knowledge enhancement..

These findings, based on managers’ perspectives, suggest that online communities and their managers have developed distinct roles in facilitating access to and preservation of genealogical knowledge in the social media age.

According to the managers interviewed, online communities have emerged as significant knowledge hubs within contemporary genealogy, marking a fundamental shift from traditional research methods. While historical genealogical methodology relied upon physical archives, academic conferences, and interpersonal encounters, managers report a transition toward digital, decentralized, and globalized information ecology. This transformation aligns with Willever-Farr’s (2017) research, which identified digital communities’ democratizing influence and enhanced accessibility. The managers’ accounts suggest that this digital ecological transition not only expanded participant demographics but generated novel collaborative dynamics, facilitating information contribution, insight sharing, and reciprocal learning.

From the managers’ perspective, their role as community leaders has evolved to represent emergent “knowledge authorities” within digital genealogy. They describe integrating technological expertise, comprehensive historical knowledge, and social mediation competencies in their work. Their reported responsibilities transcend technical administration to encompass member connection facilitation, collaborative engagement promotion, and integration of traditional knowledge with contemporary digital methodologies. These dynamics, emphasized in Charpentier a Gallic’s (2020) research, illustrate the complexities inherent in digital community administration, particularly within specialized domains like genealogy.

The managers’ descriptions of knowledge sharing and learning within their communities demonstrate the enduring relevance of Vygotsky’s (1978) collaborative learning theory. Although conceived prior to social network emergence, the current research validates his assertions regarding social interaction’s significance in learning and collective knowledge generation. According to managers’ accounts, these communities exemplify the “Zone of Proximal Development” (ZPD) concept, wherein member interactions with experienced managers and peers facilitate understanding, enhancement and genealogical research advancement. These insights align with Durrington and Du’s (2013) findings regarding digital environments’ capacity for knowledge co-creation.

These findings reinforce and extend Stein’s (2009) conceptualization of online communities as central genealogical information hubs. Managers describe how their communities facilitate access to previously obscured databases and contribute significantly to collective memory formation. Although Stein’s research predates current technological developments by fifteen years, the managers’ accounts suggest that her fundamental assertion regarding online communities’ centrality remains valid, with subsequent technological and social developments enhancing their position as knowledge hubs.

Of particular significance is managers’ perception of their role as custodians of communal memory, especially within communities focused on Holocaust-affected, migrated, or diminished populations. The managers describe how their activities expand community function beyond knowledge dissemination platforms to spaces that preserve and transmit collective memory, adding new dimensions to the traditional understanding of genealogical research communities.

Finally, the findings highlight what managers perceive as their exceptional commitment levels. While Fulton (2016) characterized genealogy as “serious leisure”, the interviewed managers describe their roles as having evolved beyond recreational boundaries into intensive endeavors demanding substantial temporal, energetic, and resource investment. According to their accounts, this commitment encompasses content management, interaction facilitation, collaboration strategy development, technological adaptation, continuous learning, and support for individual and collective member requirements.

7. Conclusions

Based on community managers’ accounts and perceptions, this research presents a distinctive contribution to understanding genealogical information ecology within the digital paradigm. Its primary innovation lies in identifying two emergent constituents: Online communities as collaborative knowledge hubs and community managers as central knowledge authorities in the generation, formation, and governance of collective knowledge according to managers’ self-perception.

The research emphasizes the fundamental transformation in genealogical knowledge creation and dissemination processes, evolving from traditional methodological constraints to contemporary digital communities’ virtually unrestricted accessibility.

While previous studies, such as Charpentier and Gallic’s (2020), focused on platform characteristics, the current research deepens understanding of online genealogy communities’ internal dynamics and administrative significance. These insights complement Stein’s (2009) and Willever-Farr’s (2017) work, while expanding theoretical frameworks by positioning manager roles as pivotal knowledge hubs within digital information ecology.

7.1. Limitations of the Study

Despite its contribution to understanding the central role of online genealogy communities and their managers as knowledge hubs, the current research has several methodological limitations. The first limitation lies in its reliance on community managers’ own perceptions, who are themselves integral parts of the knowledge ecology they describe. As they discuss their own role and position within this ecology, there may be inherent bias in their portrayal of their place and function. The managers might have emphasized or elevated their position while potentially understating other factors. Future research should examine the perspectives of community users themselves and those interested in genealogy but not participating in these communities to provide a more comprehensive understanding of these knowledge hubs.

Another limitation concerns the focus on Jewish online genealogy community managers, which may reflect unique dynamics related to ethnic origin and Jewish history that may not necessarily represent general genealogical communities.

Additionally, while the focus on Facebook as a platform may appear to be a methodological limitation, findings from this dissertation’s first chapter, which examined collaborative genealogical activity in a WhatsApp group, indicate similar patterns of community knowledge co-creation across other social media platforms.

7.2. Challenges and Future Research

This research presents both practical and theoretical implications, underscoring digital communities’ significance in genealogical information accessibility while providing insights into administrative challenges and opportunities. The findings generate new research trajectories and questions for future examination. Subsequent research might explore member perspectives regarding administrative roles and contributions to collective knowledge generation. Additionally, inter-community dynamics and knowledge exchange patterns warrant research.

A critical challenge meriting further research concerns knowledge continuity and intergenerational transfer between community managers. Given the predominantly advanced age of current genealogy community managers, questions arise regarding preservation and transmission of accumulated knowledge and expertise to subsequent administrative generations. This concern becomes particularly salient considering increasing technological complexity and the imperative to integrate genealogical expertise with advanced digital competencies.

Statements and Declarations

Ethical considerations

Funding statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Will be available upon request.

Consent to participate

A study of survey participants: The Ethics Review Committee at Ariel University approved our interviews (approval: AU-COM-ALO-20240723) on July 23, 2024. Respondents gave written and video-recorded consent for review and signature before starting interviews.

Consent for publication

I hereby confirm that I have received written and video- recorded informed consent from all participants for the publication of this research. All participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose and the intended use of their data in publication, and they provided their explicit written consent for their responses to be used in this research publication.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Amann, J., and S. Rubinelli. 2017. Views of community managers on knowledge co-creation in online communities for people with disabilities: qualitative study. Journal of medical Internet research 19, 10: e320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A., and D. Toshniwal. 2020. Identifying Managership Characteristics from Social Media Data during Natural Hazards using Personality Traits. Scientific Reports 10, 1: 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charpentier, A., and E. Gallic. 2020. Using collaborative genealogy data to study migration: a research note. The History of the family 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottica, A., G. Melançon, and B. Renoust. 2017. Online community management as social network design: testing for the signature of management activities in online communities. Applied Network Science 2: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, G. 2009. Speed-relating: Family history in a digital age. History Australia 6, 2: 43–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrington, V. A., and J. Du. 2013. Learning tasks, peer interaction, and cognition process an online collaborative design model. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE) 9, 1: 38–50. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/185933/10.4018/jicte.2013010104. [CrossRef]

- Duster, T. 2016. Ancestry Testing and DNA: Uses, Limits–and Caveat Emptor 1. In Genetics as social practice. Routledge: pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, and Luke. 2022. Best genealogy sites 2023. June 14. Available online: https://www.toptenreviews.com/best-genealogy-websites.

- Eitan, T., and T. Gazit. 2023. Manager behaviors in Facebook support groups: An exploratory study. Current Psychology 42, 12: 9691–9707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family Search. 2023. Use the internet for family history research. Available online: https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Use_the_Internet_for_family_history_research.

- Fulton, C. 2009. The pleasure principle: the power of positive affect in information seeking. In Aslib Proceedings. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, May, Vol. 61, No. 3, pp. 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, C. 2016. The genealogist’s information world: Creating information in the pursuit of a hobby. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 8, 1: 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, L., T. Gazit, and J. Bronstein. 2023. The motivations of managers to lead Facebook online groups: a case study of parenting groups. Behaviour & Information Technology 42, 10: 1604–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, O., and M. Martini. 2020. The Making of contemporary papacy: Manufactured charisma and Instagram. Information, Communication & Society 23, 9: 1368–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffaker, D. 2010. Dimensions of managership and social influence in online communities. Human Communication Research 36, 4: 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadin, T., T. Gnambs, and B. Batinic. 2013. Personality traits and knowledge sharing in online communities. Computers in Human Behavior 29, 1: 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y. H., C. S. Yang, C. Hsu, and J. H. Wang. 2019. A longitudinal study of manager influence in sustaining an online community. Information & Management 56, 2: 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. A., P. M. Gee, C. L. Ho, and L. E. Miller. 2018. Understanding why older adults with type 2 diabetes join diabetes online communities: semantic network analyses. JMIR Aging 1, 1: e10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, C. P. 2007. Querying information systems or interacting with intermediaries? Towards understanding the informational capacity of online communities. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 44, 1: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S. M., and D. A. Rosenthal. 2021. What Motivates Family Historians? A Pilot Scale to Measure Psychosocial Drivers of Research into Personal Ancestry. Genealogy 5, 3: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S. S. 2018. Case-based reasoning for identifying knowledge manager within online community. Expert Systems with Applications 97: 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2023. Online Etymology Dictionary (Genealogy. Available online: https://www.etymonline.com/word/genealogy.

- Panteli, N. 2016. On managers’ presence: interactions and influences within online communities. Behaviour & Information Technology 35, 6: 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, J. 2017. Information journeys in digital archives. Doctoral dissertation, University of York. [Google Scholar]

- Rohman, A. 2020. The emergence, peak, and abeyance of an online information ground: the lifecycle of a facebook group for verifying information during violence. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 72, 3: 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SimilarWeb. 2023. Most Visited Ancestry and Genealogy Websites Ranking Analysis for August 2023. Available online: https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites/hobbies-and-leisure/ancestry-and-genealogy/.

- Stein, A. 2009. Trauma and origins: Post-Holocaust genealogists and the work of memory. Qualitative Sociology 32, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D. J., and J. K. Guelke. 2016. Geography and genealogy: Locating personal pasts. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tohani, E., P. Fauziah, I. Prasetya, M. Munifah, and D. Sylviani. 2023. Ict training to improve clc data management through nonformal education service program. Jurnal Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat (Indonesian Journal of Community Engagement) 9, 2: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Veer, R., and M. H. Van IJzendoorn. 1985. Vygotsky’s theory of the higher psychological processes: some criticisms. Human Development 28, 1: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veresov, N. N., and I. E. Kulikovskaya. 2015. Human world-outlook evolution: from L.S. Vygotsky to modern times. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6, 3: 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022. Verified Market Research Global genealogy products & services market size by application (household and institution), by product (newspaper, blog links, DNA testing), by geographic scope and forecast. September. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/genealogy-products-services-market/.

- Brevis, Vita. 2023. A Resource for Family History from AmericanAncestors.org Facebook’s locational genealogy groups. April 6. Available online: https://vitabrevis.americanancestors.org/2023/04/facebooks-locational-genealogy-groups.

- Wenger, E. 1999. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willever-Farr, H. L. 2017. Finding Family Facts in the Digital Age: Family History Research and Production Literacies. Drexel University. [Google Scholar]

- Yakel, E. 2004. Seeking Information, Seeking Connections, Seeking Meaning: Genealogists and Family Historians. Information Research: an international electronic journal 10, 1: n1. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).