Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

16 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How do users of the NCNPF arrive at their landscaping decisions and what factors influence their adoption of native landscaping?

- How does the NCNPF influence its users in their native and exotic landscaping choices?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Native Plants

2.2. Pro-Environmental Behavior and Intention

2.3. Social Networking Sites (SNSs)

2.4. Models of PEB

2.5. Factors Leading to PEB

2.5.1. Personal

2.5.1.1. Knowledge

2.5.1.2. Nature Connectedness

2.5.1.3. Self-efficacy

2.5.1.4. Personal Norms

2.5.2. Social

2.5.2.1. Social Norms

2.5.2.2. Role Modeling Behavior

2.5.3. Contextual

2.5.3.1. Place Attachment

2.5.3.2. Sense of Belonging

3. Materials and Methods

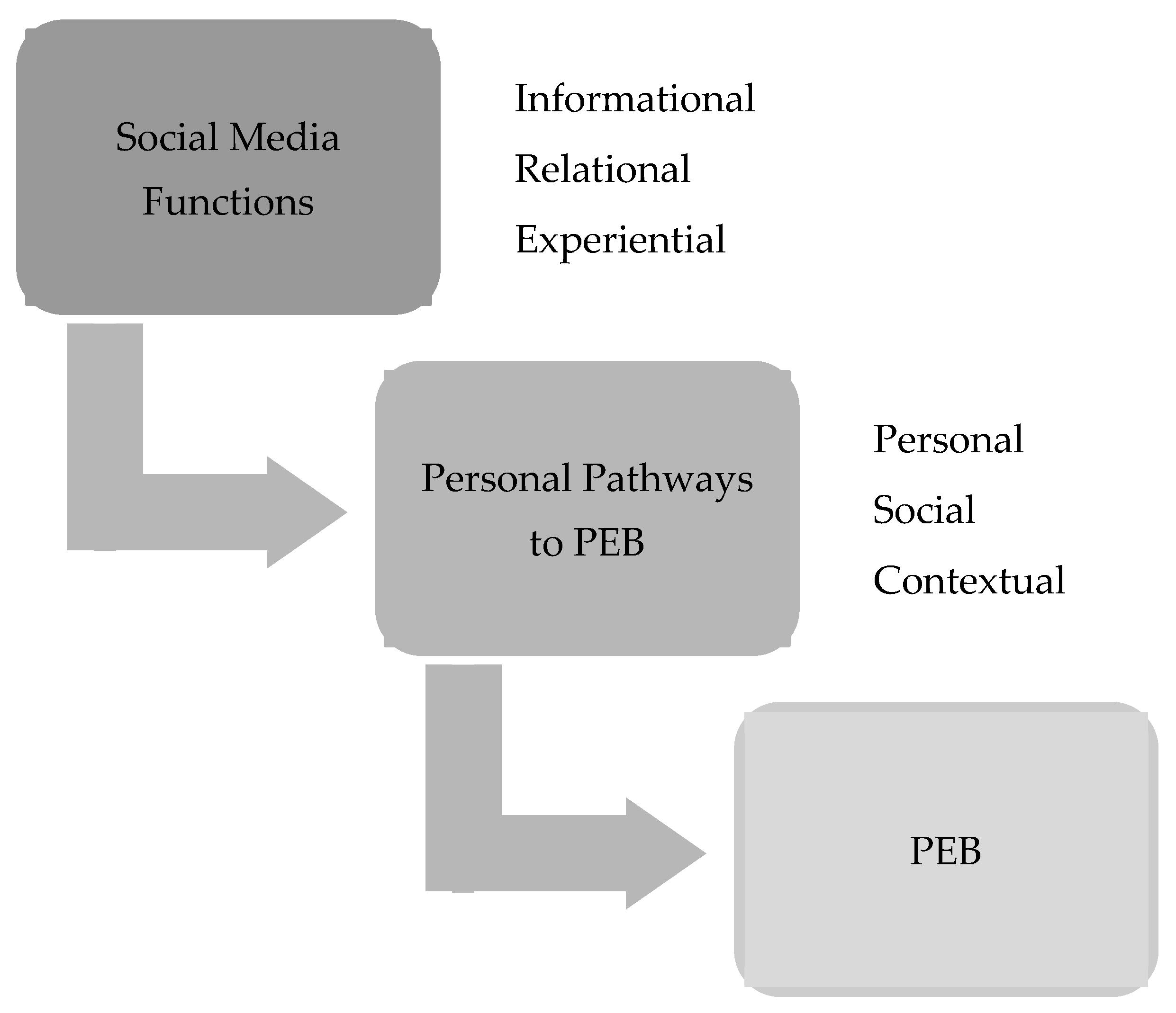

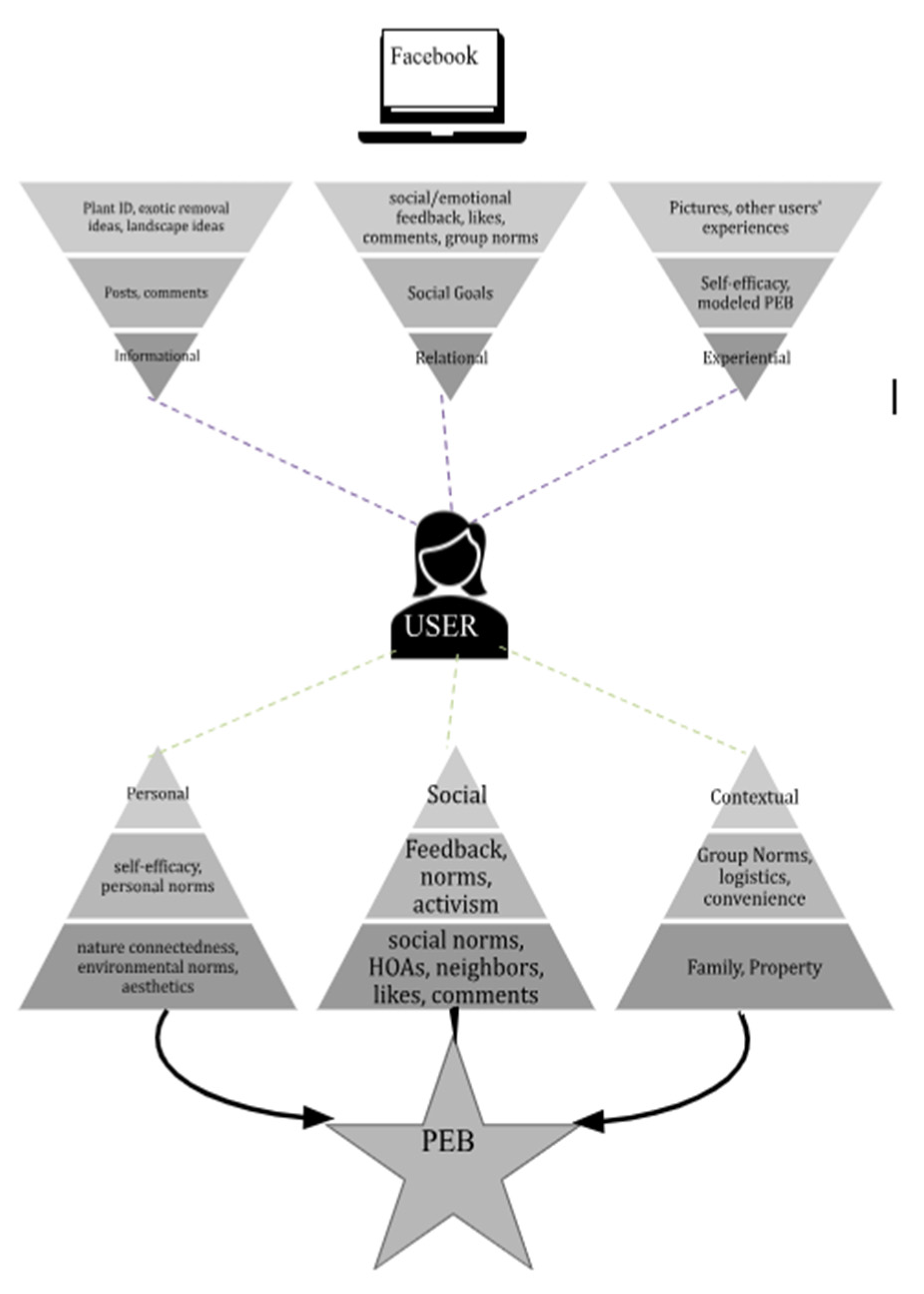

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Interviews

3.4. Coding

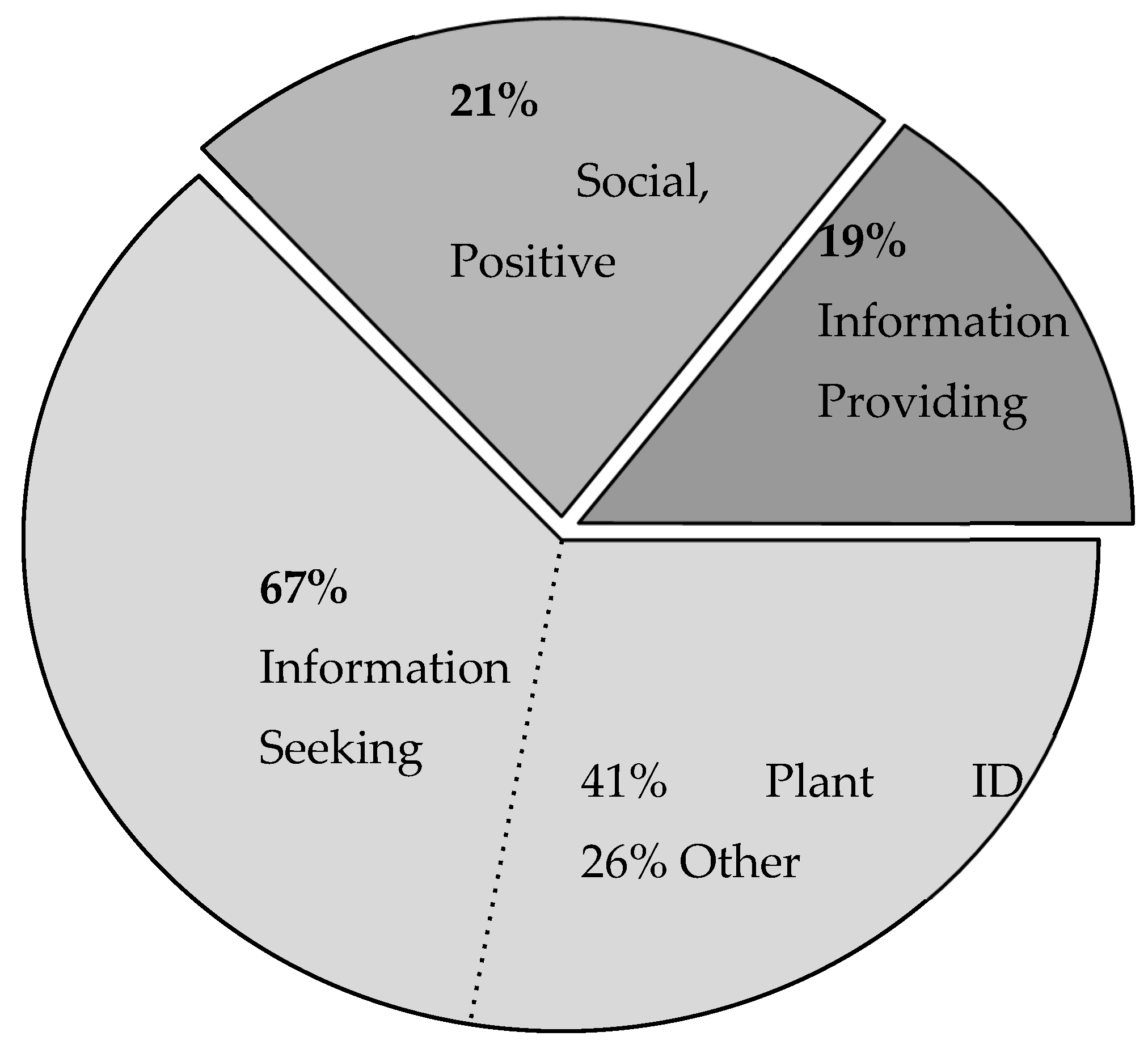

3.5. Content Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Personal Factors

4.2. Social

4.2.1. Social norms and home-owners associations.

4.2.2. Self-efficacy

4.3. Contextual

4.3.1. Property

4.3.2. Related Interests

4.3.3. Aesthetics

4.4. Research Question #2: How does the NCNPF Influence its users in their native planting choices?

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

- Tell me about yourself and how you got interested in native plants.

- Are you generally an environmentalist? What other environmental actions do you take?

- Tell me about your land. How big is it, and how much exotic eradication/native planting have you done?

- Tell me about one native plants project you undertook. What factors led up to this project?

- What are some things you have learned from the NCNPF?

- How does the NCNPF influence your landscaping choices?

- What frustrates you about using the NCNPF?

Appendix B

Code Book

| tag | description | number of highlights |

| precursor | Something that had to happen leading up to NP PEB. Includes buying property, family gardening, assessing a threat, environmentalism and related interests. |

51 |

| precursor.property | the precursor of property purchase | 15 |

| precursor.first | first native plant experience | 11 |

| low-maintenance | Participants describe native plants as low-maintenance. This is said as a reason that native planting matters. The plants require less water, less work and less time. |

26 |

| word of mouth | Participants describe gaining information about the NPF or plants, from a friend or family member. Includes informal EE like extension agent, botanical garden tour |

34 |

| raising confidence | displays or discusses an increase in self-efficacy. This includes IDing plants, finding plant sources, sharing experiences, learning new information, experimenting, becoming an advocate | 86 |

| NPF | North Carolina Native Plant Forum on Facebook. Code indicates that the participant is commenting on the forum's users, content, interactions or rules. |

80 |

| finding suppliers | Participants mention finding NP suppliers through NPF as a limitation to their PEB, or as a crucial step in the process that is aided by the NPF |

20 |

| related interest | a related interest that brings the interviewee to native plants | 24 |

| natural history | Participants describe the natural history of plants as a reason for their interest, outside of environmental reasons. stories of land and plants and people |

7 |

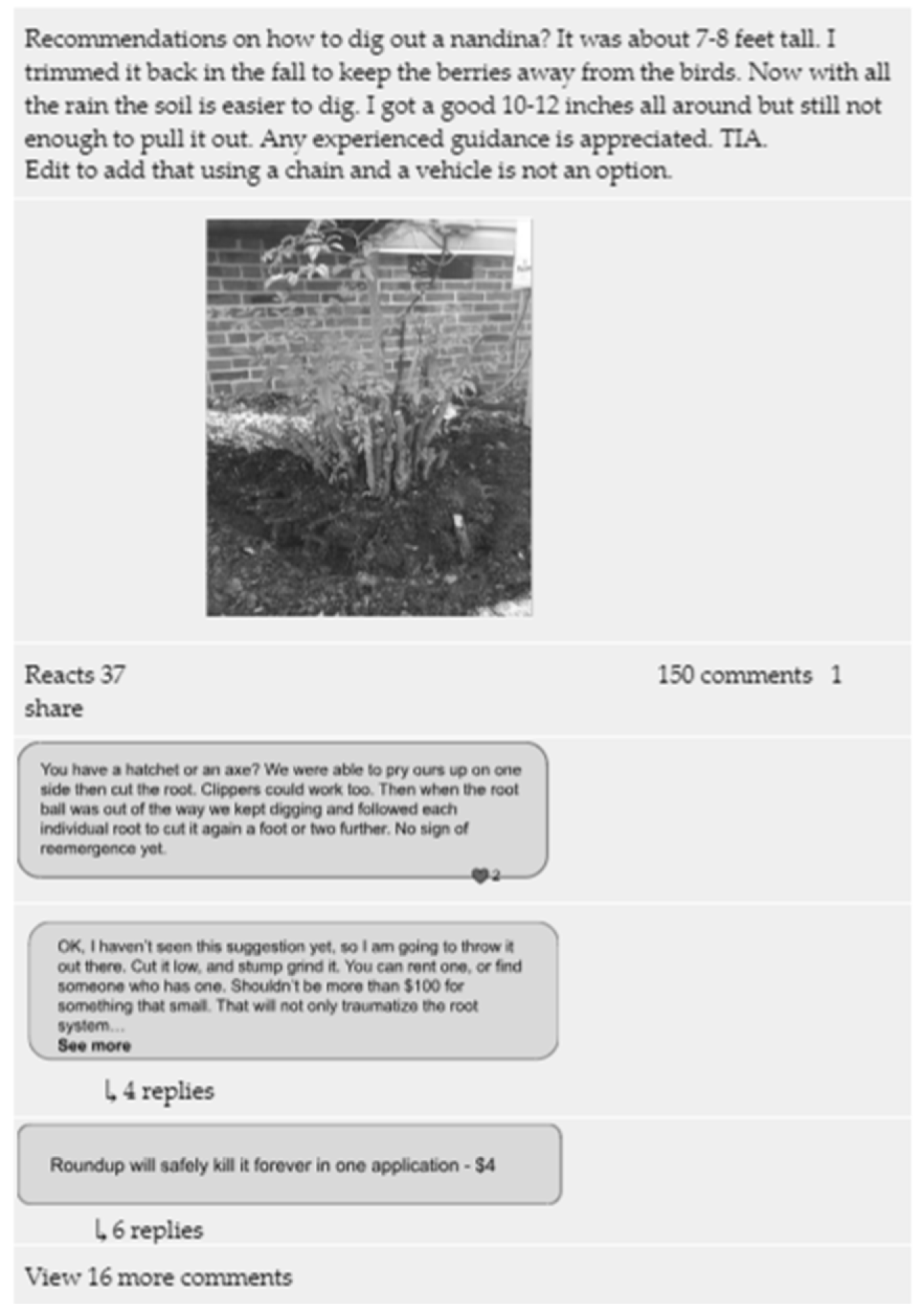

| frustration.misinformation | Participants describe frustration with the NCNPF because of misinformation in the forum. This usually involves users guessing incorrectly at Plant ID, or providing spurious advice for planting, maintaining, removal, or care of plants. |

8 |

| frustration.repitition | Some participants noted frustration with the NCNPF because users post the same posts over and over, usually ID requests. This causes lots of repetition. Not included are participants who find the repetition useful. |

1 |

| environmentalism | generally how environmental is the person? A participant discusses their overall environmentalism and how it relates to their planting choices. Includes self-reports of recycling, plastic reduction and taking your own bags to the grocery store. |

55 |

| PEB | pro-environmental behavior. Includes planting natives, removing exotics, recycling, reducing plastic (after the merging with non-plant PEB. | 130 |

| materials | Participants list important educational materials they have used, includes books, websites, facebook groups |

42 |

| becoming advocate | the person describes becoming an advocate in their communities for native plants. This can include plant swaps, demo gardens, lobbying HOAs, or sharing information formally or informally. | 44 |

| learning | Participants describe integrating new information into their cognitive conception | 63 |

| why it matters | Also described as "values". Participants, when asked why NP mattered to them, list climate change, pollinators, wildlife, ecosystems, and others. |

34 |

| family gardening | the interviewees describe the influence of family members' gardening interests on them. Influential family members can be parents, guardians, uncles, aunts, grandparents, children or grandchildren. | 19 |

| wildlife | Participants describe the importance of wildlife in their planting choices. Includes negative wildlife interactions as with deer eating landscaping. |

38 |

| pollinators | Participants mention pollinators as a reason they feel native planting is important, or something they learned. Pollinators include bees, wasps, butterflies, moths, birds, etc. |

33 |

| Identifying plants | a learning step that is prerequisite for planting native and removing exotics. Includes participants who describe using NCNPF for plant id or for determining its native status. |

40 |

| sharing experiences | Participants describe getting information, inspiration and satisfaction from sharing their NP experiences on the forum and seeing others' experiences, especially with photos. Doesn't include comments, likes and emojis. |

47 |

| gauging public attitude | Participants report being sensitive to the general public's attention to and attitude towards native plants. Includes instances of noticing positive and negative attitudes. Includes HOAs. | 31 |

| aesthetics | what matters to interviewee. Participant discussed the aesthetic value of native plants or exotic plants |

35 |

| passion/obsession | expressed by interviewees about native plants. Participants describe a fierce passion and obsession developing as they learned and experimented with native plants. Interviewees use words like down the rabbit hole, into the weeds, totally obsessed. |

36 |

| hoping | Participants describe finding hope in the impacts of native planting and in the large community building around it. Its included in both the category of social feedback, and why it matters. | 22 |

| assessing a threat | A participant discusses threats to themselves, to humans, to the environment from climate change, exotic plants, biodiversity collapse and others. |

29 |

| using fb for good | Participants describe value of the NCNPF as a way to make facebook a positive experience with learning opportunities and cool pictures. Includes comparisons with political arguments on facebook. | 8 |

| overriding PEB intent for convenience | Participants describe various failures to perform PEB as attributable to convenience | 22 |

Appendix C

Image Collage

References

- Fonseca, C.R. The silent mass extinction of insect herbivores in biodiversity hotspots. Conserv Biol. 2009, 23, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atske, S. As economic concerns recede, environmental protection rises on the public’s policy agenda. Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy. February 13, 2020. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/02/13/as-economic-concerns-recede-environmental-protection-rises-on-the-publics-policy-agenda/.

- Four in five parents want schools to teach about climate change. Ipsos. April 22, 2019. Accessed November 4, 2023. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/four-five-parents-want-schools-teach-about-climate-change-04-22-2019.

- TheGovLab. The Power of Virtual Communities. TheGovLab; 2021:21. https://virtual-communities.thegovlab.org/.

- Pew Research Center. Gen Z, Millennials more active than older generations addressing climate change on- and offline _ Pew Research Center.pdf. May 24, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/05/26/gen-z-millennials-stand-out-for-climatechange-activism-social-media-engagement-with-issue/ps_2021-05-26_climate-andgenerations_00-01/.

- Potter, G. Environmental education for the 21st century: Where do we go now? J Environ Educ. 2009, 41, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robelia, B.A.; Greenhow, C.; Burton, L. Environmental learning in online social networks: Adopting environmentally responsible behaviors. Environ Educ Res. 2011, 17, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Curtis, J. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: A review of methods and approaches. Renew Sustain Energy Rev, 2021; 135, 110039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audubon. Why Native Plants Matter. 2023. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.audubon.org/content/why-native-plants-matter#:~:text=Native%20plants%20provide%20nectar%20for,for%20all%20forms%20of%20wildlife.

- Tallamy, D.W. The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees. Timber Press; 2021.

- Narango, D.L.; Tallamy, D.W.; Marra, P.P. Nonnative plants reduce population growth of an insectivorous bird. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018, 115, 11549–11554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaury, E.M.; Patrick, M.; Bradley, B.A. Invaders for sale: the ongoing spread of invasive species by the plant trade industry. Front Ecol Environ. 2021, 19, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early, R.; Bradley, B.A.; Dukes, J.S. , et al. Global threats from invasive alien species in the twenty-first century and national response capacities. Nat Commun. 2016, 7, 12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Joshi, N.K. Assessing role of major drivers in recent decline of monarch butterfly population in north america. Front Environ Sci 2018, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D.R.; Hadiyanto, H.; Hadi, S.P. Pro-environmental behavior from a socialcognitive theory perspective. Procedia Environ Sci 2015, 23, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley Schultz, P.; Zelezny, L. Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: Evidence for consistency across 14 countries. J Environ Psychol. 1999, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ Educ Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In: Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol 10. Elsevier; 1977:221-279.

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemp Educ Psychol 2020, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Liobikienė, G.; Saadi, H.; Sepahvand, F. The influence of media usage on iranian students’ pro-environmental behaviors: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.O.; Whitmarsh, L.; Haddock, G.; Mac Giolla Chríost, D. A grounded theory of pro-nature behaviour: From moral concern to sustained action. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Richardson, M.; Lumber, R. Evaluating connection to nature and the relationship with conservation behaviour in children. J Nat Conserv. 2018, 45, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The importance of environmental knowledge for private and public sphere pro-environmental behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. Advances in consumer research, 32, p.592.

- Han, W.; Wang, Y.; Scott, M. Social media activation of pro-environmental personal norms: an exploration of informational, normative and emotional linkages to personal norm activation. J Travel Tour Mark. 2021, 38, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N.; Wilson, J. I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: Can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technol Forecast Soc Change 2016, 111, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, K. Media and social norms: Exploring the relationship between media and plastic avoidance social norms. Environ Commun. 2022, 16, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, E.; Ginanti, A. Online environmental citizenship: Blogs, green marketing and consumer sentiment in the 21st century. Electron Green J. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, X.; Gu, M. Promote pro-environmental behaviour through social media: An empirical study based on Ant Forest. Environ Sci Policy 2022, 137, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Wei, L.; Ghani, U. The use of social networking sites and pro-environmental behaviors: A mediation and moderation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, K.Y.; Heng, C.S.; Lin, Z. Social media brand community and consumer behavior: Quantifying the relative impact of user-and marketer-generated content. Inf Syst Res. 2013, 24, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Read, G.L.; Chen, J. Changing attitudes on social media: Effects of fear and information in green advertising on non-green consumers. J Curr Issues Res Advert. 2021, 42, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, S.; Ohme, J. Pathways to environmental activism in four countries: social media, environmental concern, and political efficacy. J Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 771–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujata, M.; Khor, K.S.; Ramayah, T.; Teoh, A.P. The role of social media on recycling behaviour. Sustain Prod Consum 2019, 20, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba-Nalikant, M.; Syed-Mohamad, S.; Husin, M.; Abdullah, N.; Saleh, M.; Rahim, A. A zero-waste campus framework: Perceptions and practices of university campus community in Malaysia. RECYCLING 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattini, S.; Gillingham, K.; Meng, X.; Yoeli, E. Peer-to-peer solar and social rewards: Evidence from a field experiment. J Econ Behav Organ. 2024, 219, 340–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.W.; Russell, S.V.; Robinson, C.A.; Chintakayala, P.K. Sustainable retailing – Influencing consumer behaviour on food waste. Bus Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X. Pro-environmental behavior predicted by media exposure, SNS involvement, and cognitive and normative factors. Environ Commun. 2021, 15, 954–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, Z.J. Extending media system dependency theory to informational media use and environmentalism: A cross-national study. Telemat Inform 2020, 50, 101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour Conserv Recycl 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.; Omoto, A.; Winter, P. Using Web 2.0 and social media technologies to foster proenvironmental action. Sustainability. 2015, 7, 10620–10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rock, B.; Henaff, F.L. Walk the talk: Measuring green preferences with social media data. In: ULB -- Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Working Papers ECARES: 2023-17; 2023:61 p. https://proxying.lib.ncsu.edu/index.php?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=2076911&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Dekoninck, H.; Schmuck, D. The mobilizing power of influencers for pro-environmental behavior intentions and political participation. Environ Commun. 2022, 16, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallivan, N.P. “What Happens next Is up to You:” Encouraging Americans’ Engagement in and Communication about the Issue of Climate Change. University of Iowa; 2016.

- Shen, M.; Lu, Y.; Kua, H.W.; Cui, Q. Eco-feedback delivering methods and psychological attributes shaping household energy consumption: Evidence from intervention program in Hangzhou, China. J Clean Prod 2020, 265, 121755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domalewska, D. A longitudinal analysis of the creation of environmental identity and attitudes towards energy sustainability using the framework of identity theory and big data analysis. Energies. 2021, 14, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.; Yaacob, N.; Ab Samat, R.; Ismail, A. Knowledge, readiness and barriers of street food hawkers to support the single-use plastic reduction program in northeast Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y. Uses and gratifications of and exposure to nature 2.0 and associated interdependence with nature and pro-environmental behavior. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2022, 40, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Otsuka, Y. Pro-climate behaviour and the influence of learning sources on it in Chinese adolescents. Int Res Geogr Environ Educ. 2021, 30, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhamaliveva, S.; Giosan, C.; Opariuc-Dan, C. Relationship between Instagram users’ information-sharing behavior and nature relatedness. Romanian J Appl Psychol, Published online June 19, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dini, M.; Curina, I.; Francioni, B.; Hegner, S.; Cioppi, M. Tourists’ satisfaction and sense of belonging in adopting responsible behaviors: the role of on-site and social media involvement in cultural tourism. TQM J. 2023, 35, 388–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Han, R. The Influence of place attachment on pro-environmental behaviors: The moderating effect of social media. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaini, A.; Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J.; Hussin, N. “I buy green products, do you…?” The moderating effect of eWOM on green purchase behavior in Malaysian cosmetics industry. Int J Pharm Healthc Mark. 2020, 14, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, D. Mind the Gap: How Zhongyong thinking affects the effectiveness of media use on pro-environmental behaviours in China. Environ Commun- J Nat Cult. 2023, 17, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Geiger, M.; Wilhelm, O. Environment-specific vs. general knowledge and their role in pro-environmental behavior. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolderdijk, J.W.; Gorsira, M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. Values determine the (in)effectiveness of informational interventions in promoting pro-environmental behavior. Ozakinci G, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e83911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Murtagh, N.; Abrahamse, W. Values, identity and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemp Soc Sci. 2014, 9, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J Environ Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladwani, A.M.; Almarzouq, M. Understanding compulsive social media use: The premise of complementing self-conceptions mismatch with technology. Comput Hum Behav. 2016, 60, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.c.; Chu, L.H. The mediating role of self-regulation on harmonious passion, obsessive passion, and knowledge management in e-learning. Educ Technol Res Dev. 2018, 66, 615–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Hamlin, I.; Elliott, L.R.; White, M.P. Country-level factors in a failing relationship with nature: Nature connectedness as a key metric for a sustainable future. Ambio. 2022, 51, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessnack, M. Children and nature-deficit disorder. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2009, 14, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, C.D.; Profice, C.C.; Collado, S. Nature experiences and adults’ self-reported pro-environmental behaviors: The role of connectedness to nature and childhood nature experiences. Front Psychol. 2018, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychol. 2002, 3, 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.D.; Acharya, N. Causality analysis of media influence on environmental attitude, intention and behaviors leading to green purchasing. J Clean Prod 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, C.; Vitali, J.; Ainscough, L.; Langfield, T.; Colthorpe, K. A review of self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: The key to tertiary transition in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Int J High Educ. 2021, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J Bus Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugert, P.; Greenaway, K.H.; Barth, M.; Büchner, R.; Eisentraut, S.; Fritsche, I. Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. J Environ Psychol 2016, 48, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.N.; Thurmond, B.; Mchale, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Bondell, H.D.; Cook, M. Predicting native plant landscaping preferences in urban areas. Spec Issue Third Glob Conf Renew Energy Energy Effic Desert Reg - GCREEDER 2011. 2012, 5, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pandey, M. Social media and impact of altruistic motivation, egoistic motivation, subjective norms, and EWOM toward green consumption behavior: An empirical investigation. SUSTAINABILITY 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodko, J.; Schmidtke, K.; Readl, D.; Vlaev, I. #LetsUnlitterUK: A demonstration and evaluation of the Behavior Change Wheel methodology. PLOS ONE. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubar, H.; Holagh, S.; Sadri, A. Identifying factors affecting green consumer purchase behavior on e-commerce websites. TALTECH J Eur Stud. 2023, 13, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Koo, B.; Han, H. Exploring the factors that influence customers’ willingness to switch from traditional hotels to green hotels. J TRAVEL Tour Mark. 2023, 40, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimiás, A.R.; Volo, S. Food discourse: ethics and aesthetics on Instagram. Br Food J. 2023, 125, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofio, I. How Does Climate Change Content on Social Media Influence Individual Pro-Environmental Behaviors? Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder; 2020.

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerman, S.C.; Meijers, M.H.C.; Zwart, W. The importance of influencer-message congruence when employing Greenfluencers to promote pro-environmental behavior. Environ Commun. 2022, 16, 920–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellhed, U.; Bäckström, M.; Björklund, F. Will I fit in and do well? The importance of social belongingness and self-efficacy for explaining gender differences in interest in STEM and HEED majors. Sex Roles. 2017, 77, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. Fifth Edition. SAGE; 2020.

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Rev. and expanded. Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1998.

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd edition. Sage; 2014. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Constructing_Grounded_Theory/v_GGAwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=charmaz%20kathy&pg=PR4&printsec=frontcover.

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Fourth edition. Jossey-Bass; 2016.

- Haythornthwaite, C.; Kumar, P.; Gruzd, A.; Gilbert, S.; Esteve del Valle, M.; Paulin, D. Learning in the wild: Coding for learning and practice on Reddit. Learn Media Technol. 2018, 43, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, C.; Khoza, N.; Abler, L.; Ranganathan, M. Process guidelines for establishing Intercoder Reliability in qualitative studies. Qual Res. 2016, 16, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiseman, D.L. The Path to High Status Is Paved with Litter : A Netnography of Status Competition among Litterati. 2016. https://proxying.lib.ncsu.edu/index.php?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ddu&AN=8CDD79066EC6F162&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Soule, C.; Sekhon, T. Signaling nothing: Motivating the masses with status signals that encourage anti-consumption. J MACROMARKETING. 2022, 42, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W. Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: What Works, What Doesn’t, and Why. Academic Press; 2019.

- Ballantyne, R.R.; Packer, J.M. Teaching and learning in environmental education: Developing environmental conceptions. J Environ Educ. 1996, 27, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, C.; Winkler, A.C.; Childs, A.R.; Muller, C.; Potts, W.M. Can social media platforms be used to foster improved environmental behaviour in recreational fisheries? Fish Res. 2023, 258, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.H.; Chiu, D.K.W.; Ho, K.K.W.; Au, C.H. Applying social media to environmental education: is it more impactful than traditional media? Inf Discov Deliv. 2020, 48, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Xu, J. A comparative study of the role of interpersonal communication, traditional media and social media in pro-environmental behavior: A China-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Noor, S. A study on the influence of social media on college students’ pro-environmental behavior. EURASIAN J Educ Res. 2022, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, K.A.; Hidi, S.E. The Power of Interest for Motivation and Engagement. 1st ed. Routledge; 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Binder, C.R. Determinants of different types of positive environmental behaviors: An analysis of public and private sphere actions. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Precursor | Values | Inspiration | Social/Emotional Feedback | Raised Confidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | An event, attitude, or behavior that precedes the PEB. This includes PEI, family gardening, property purchase and related interests | Personally held beliefs that contribute to PEI and PEB, including wildlife, hope, and aesthetics | An event, book, photo, website, or person who triggers PEI. In this study, a state extension agent was often mentioned as an inspiration for native planting. | Verbal, in-person, or virtual feedback (can be in the form of Facebook likes and comments on the PEB or experienced feelings like guilt or joy. | an increase in an individual’s belief that they can accomplish a PEB. Often comes from experience, experiences of others, modeled behavior, and learning. |

| Connections | Personal and contextual pathways lead to PEB | Social and personal pathways to PEB | Social and Personal pathways to PEB | Social pathway to PEBs. | Personal, social, and contextual pathways lead to more PEB. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).