1. Introduction

Rare Earth Elements (REEs) are considered valuable minerals that have a variety of applications in different industries such as tech, automotive, industrial etch [

1]. They consist of the 15 lanthanide series elements (La, Pr, Ce, Eu, Pm, Ho, Nd, Gd, Yb, Dy, Sm, Er, Tm, Tb, and Lu) with the addition of Sc and Y [

2]. With an increasing demand of REEs for clean energy market and advanced materials, alternative sources for minerals should be implemented. As of 2023, China with an annual production of around 240000 metric tons holds of 68.57 % of the annual production share of REEs followed by US at 12.29%, and Myanmar at 20.86 %, while Europe does not produce yet, despite the fact that REEs were recognized by the European Commission in 2017 as one of the vital raw materials (CRMs) to the European economy [

3,

4]. There are however, few identified REE deposits in the Europe with those associated with Mesoproterozoic rift-related magmatism in Greenland and Sweden, and with Neoproterozoic to Palaeozoic carbonatites across Greenland and the Fennoscandian Shield being the most important ones, but none of them are currently under exploitation [

5,

6].

Apatite, a group of phosphate minerals, can incorporate substantial amounts of REEs into their crystalline structure, and has been identified as an important host for rare earth and secondary source of them. [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This is due to enrichment of REE within apatite, that can be done by two processes; the first is the substitution of REE

3+ and Na

+ for Ca

2+ within the apatite, while the second is P

5+ substituted with REE

3+ and Si

4+ with the end member of the second substitution being britholite, a mineral heavily enriched in REE [

11,

12]. As a consequence, the REE content can go as high as 0.1 to 3.5 %, as shown by Owens et al. on a list presenting REE-hosting apatite deposits [

8].

The carbonatite complex, located in North Savo, Finland is a typical case of REE-enriched apatite deposit. The complex comprises of intermixed carbonatite and glimmerite, with almost all rocks constituting phosphate ore with apatite content of about ≈10 % [

13,

14]. The mine production was 11 Mt/y, and ore reserves were estimated to 234 Mt at an average grade of 4 wt. %, and has been identified as potential source of REE and F [

13,

14]. REE content in apatite was estimated to 0.3-0.4 wt. % ,while the fluorine content for the apatite ranges from 2.3 to 3.5 % [

15,

16].

Further to the primary sources of REEs, the wide range of uses and the rising global demand have led to exploration of alternative sources beyond regular mining, with the recovery from industrial wastes and byproducts like acid mine drainage and mine tailings being considered viable secondary sources of REEs [

17,

18].

Being identified as an important source of REEs, various beneficiation studies deal with the production of a valuable concentrate from ore deposits or mining tailings [

19]. For the production of bastnäsite (Ce,La(FCO3)), monazite (Ce,La(PO4)), and xenotime (YPO4) concentrates, which are the REE bearing minerals that have been extracted on a commercial scale, gravity, magnetic, electrostatic and flotation separation are commonly applied, with the latter being the most significant one worldwide [

19,

20,

21]. The most commonly used collectors for REE minerals flotation are either hydroxamic or fatty acids [

20]. Initially, fatty (carboxylic) acid was the preferred collector for bastnasite flotation due to the wide availability and low price, however considerable amounts of depressants are needed to achieve high grade and recovery in the concentrate [

22]. Regarding monazite and xenotime which are found typically together in heavy metal sand deposits, the collectors that are used are similar to bastnasite (fatty acid and hydroxamate collectors) , due to similarities at surface they share [

19]. On the other hand, apatite flotation is commonly done using either fatty acids like oleic acid [

23,

24]and sodium oleate [

25], and anionic surfactants like alkyl sulfate[

26], alkyl sulfonate [

27]and alkyl hydroxamates[

28].

Lignin is a polymer structuring the cell walls of plants, exhibiting complex structure with various functional groups, including phenolic hydroxyl, aliphatic hydroxyls and carboxyl acids, while when extracted using organic solvents (organosolv), results in a less chemically modified and more uniform product compared to other lignin types[

29]. Recent studies have shown that organosolv lignin nanoparticles can be beneficial to the flotation by interacting with mineral surfaces, probably through the many functional groups [

30]. Other studies have shown that lignin is beneficial to the flotation because it enhances the separation efficiency through depressing calcite [

31] in scheelite-calcite system, and molybdenite in molybdenite-chalcopyrite system [

32]. The use of lignin in the flotation process is of particular interest because of the environmental benefits that arise from the fact that it is biodegradable, natural and renewable biopolymer of low toxicity, as well as its abundance and cost-efficiency.

Potential use of organosolv lignin micro- and nanoparticles have been investigated by Hruzova et al. in a Cu-Ni sulfide ore (Maurliden, Sweden) and a complex Cu-Pb-Zn ore (Kristineberg, Sweden), leading to improvement to the Zn grade and recovery, Ni grade and Pb recovery [

33]. In another study dealing with Kupfershiefer copper ore (Poland), it was shown that lignin nanoparticles can replace maltodextrin in final concentrate selective flotation, where it would provide the selective separation of copper and total organic carbon [

34]. Angelopoulos et al. use organosolv lignin nanoparticles to partially replace sodium isopropyl xanthate (SIPX) in the flotation of sphalerite and pyrite/arsenopyrite from mixed sulfide ore, achieving higher sphalerite grade and higher pyrite arsenopyrite grade and recovery by 50% replacement of SIPX by lignin[

35]. Recently, Bazar et al investigated the flotation of iron oxide apatite ore tailings using a combination of tall oil fatty acid-based collector (TOFA) and organosolv lignin nanoparticles focusing on the identification of synergy[

36]. The study highlights a synergistic effect between OLP and the TOFA collector, suggesting that lignin might interact with TOFA, either by enhancing its adsorption onto apatite or by surface modification, leading to higher P

2O

5 grade and recovery.

The article presents an investigation on the beneficiation potential of ore originated from Finnish carbonatite complex, targeting the recovery of fluorapatite concentrate through froth flotation tests with dual aim; the identification of the possibility to achieve enrichment of REEs in parallel to the concentration of fluorapatite by evaluating the performance of different conventional reagents on that, but also the determination of the separation performance under the reduction of best-performance collectors and the addition of lignin, on application levels extending from lab- to bench scale.

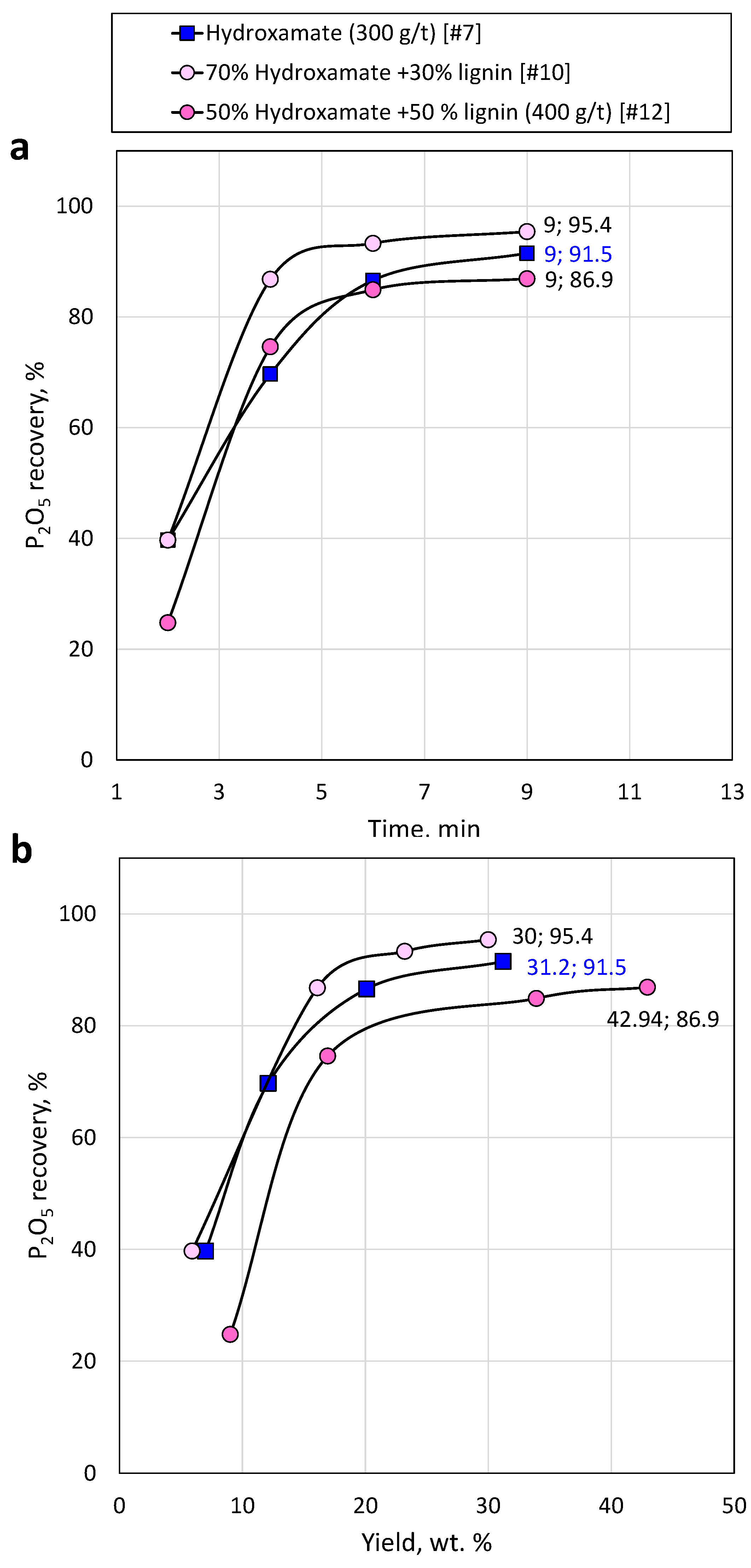

4. Conclusions

The study presented the results of flotation tests for the recovery of REE-hosting apatite from ore originating from a carbonatite deposit, Finland, using conventional anionic and amine-based collectors, but also natural organosolv lignin nanoparticles individually or a mixture to identify synergies. The following conclusions are drawn from the chemical and mineralogical characterization of the ore, and the evaluation of flotation products:

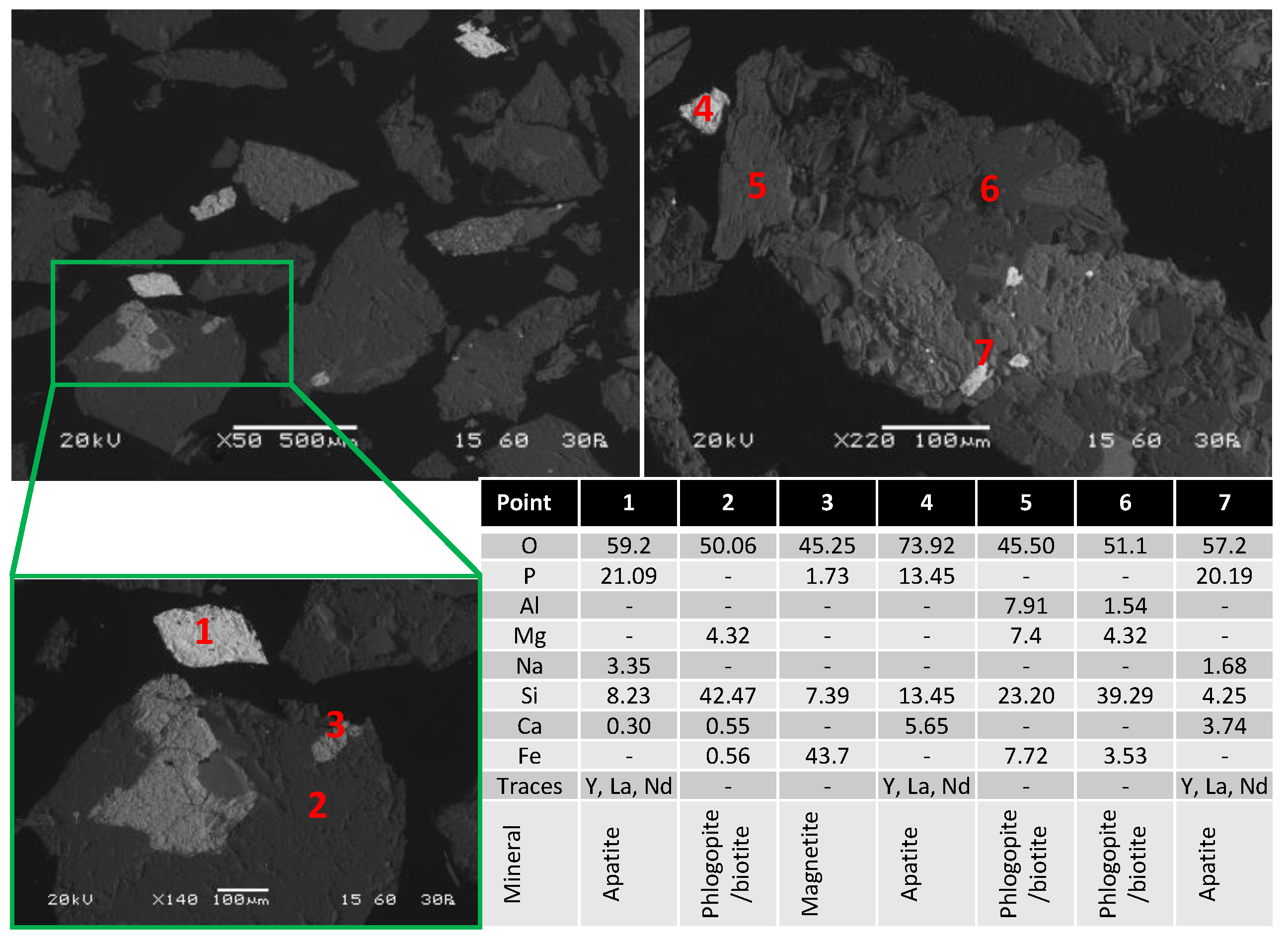

The ore originates from carbonatite deposit, located in central Finland exhibits fluorapatite content of about 8.9 %, having also overall content on L, Ce and Y of about 0.03%.

Apatite hosts most of REE minerals, which was confirmed by the flotation tests which shown that the concentration of apatite implies concentration of the L, Ce and Y.

Adequate recovery of apatite and REEs was achieved using common anionic collectors hydroxamate and sacrosine reaching P grade of 23.4 and 21.5%, and recovery of 96.4% and 89.2 %, at collector dosage of 250 and 300 g/t, and pH of 10 and 11, respectively.

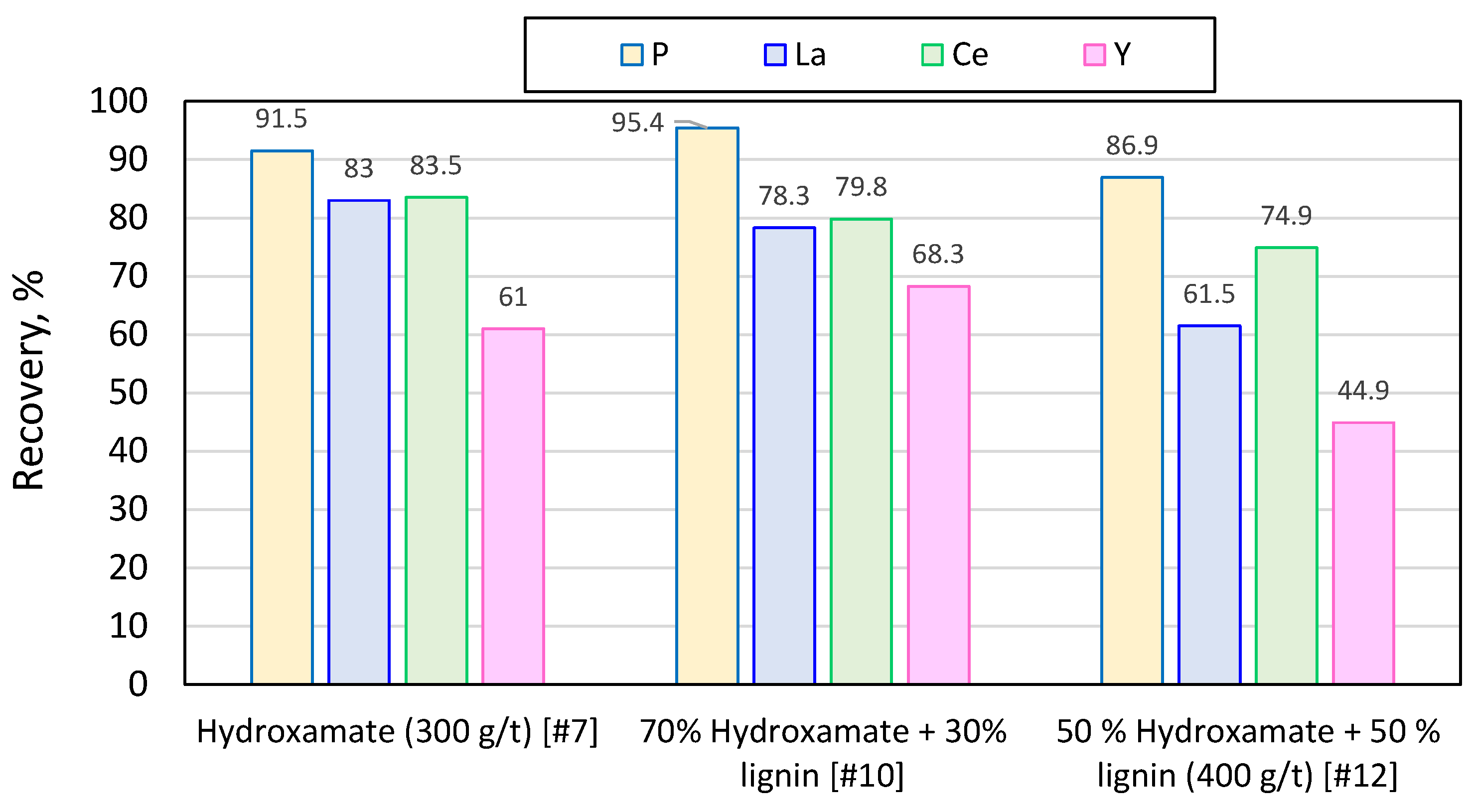

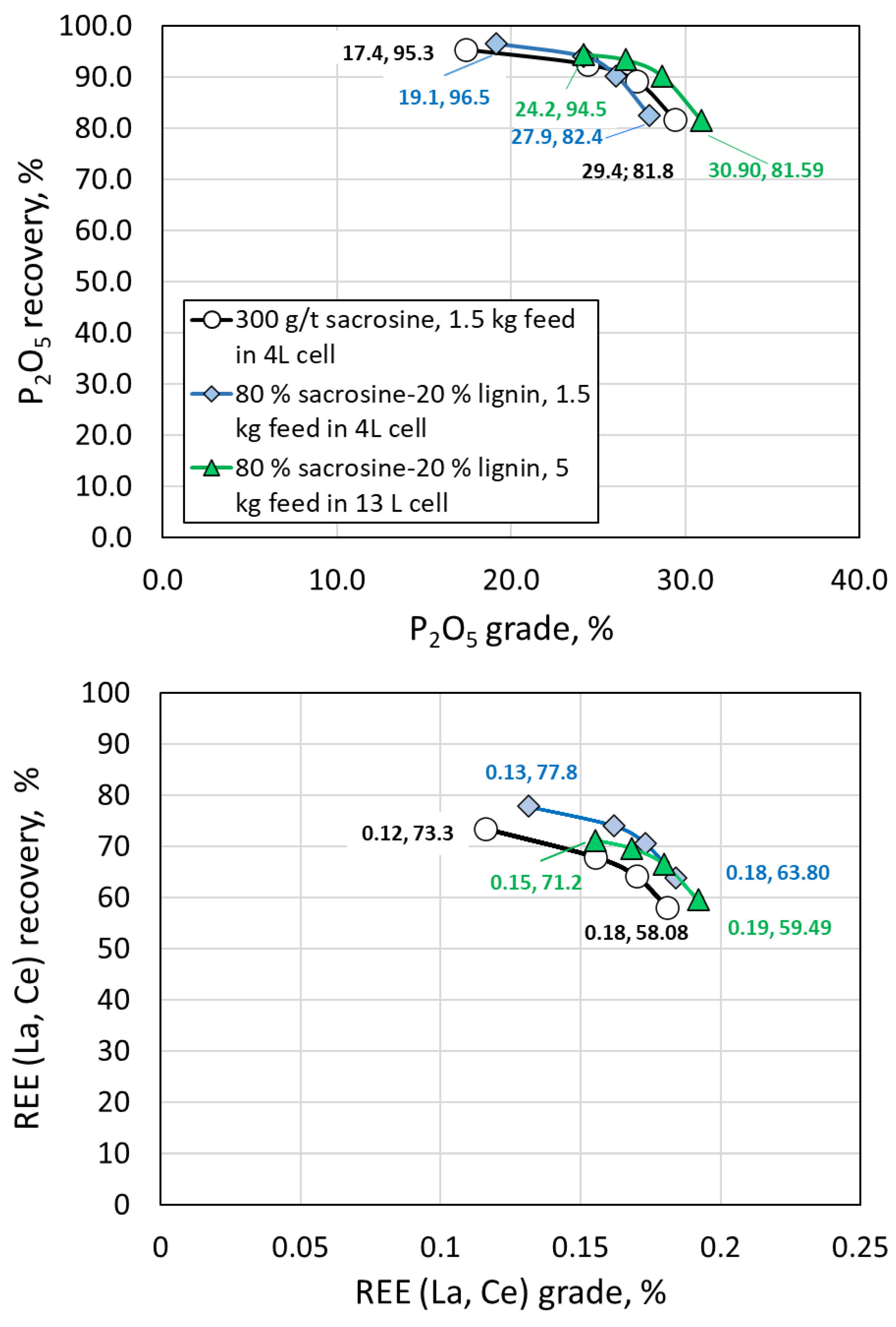

The reduction of conventional collectors by up to 30% and the addition of lignin nanoparticles does not burden the flotation process and does not deteriorate the quality of the concentrate; in sacrosine and hydroxamate after collectors’ reduction by 30% and addition of lignin nanoparticles the P recovery reached 86.7% and 95.4 %, respectively.

Bench scale flotation tests in 13 L flotation cell confirmed the lab-scale results for sacrosine; 20 % reduction of sacrosine and addition of lignin nanoparticles allowed obtaining of concentrate with P recovery of 94.5%, and La and Ce recovery of 71.5%.

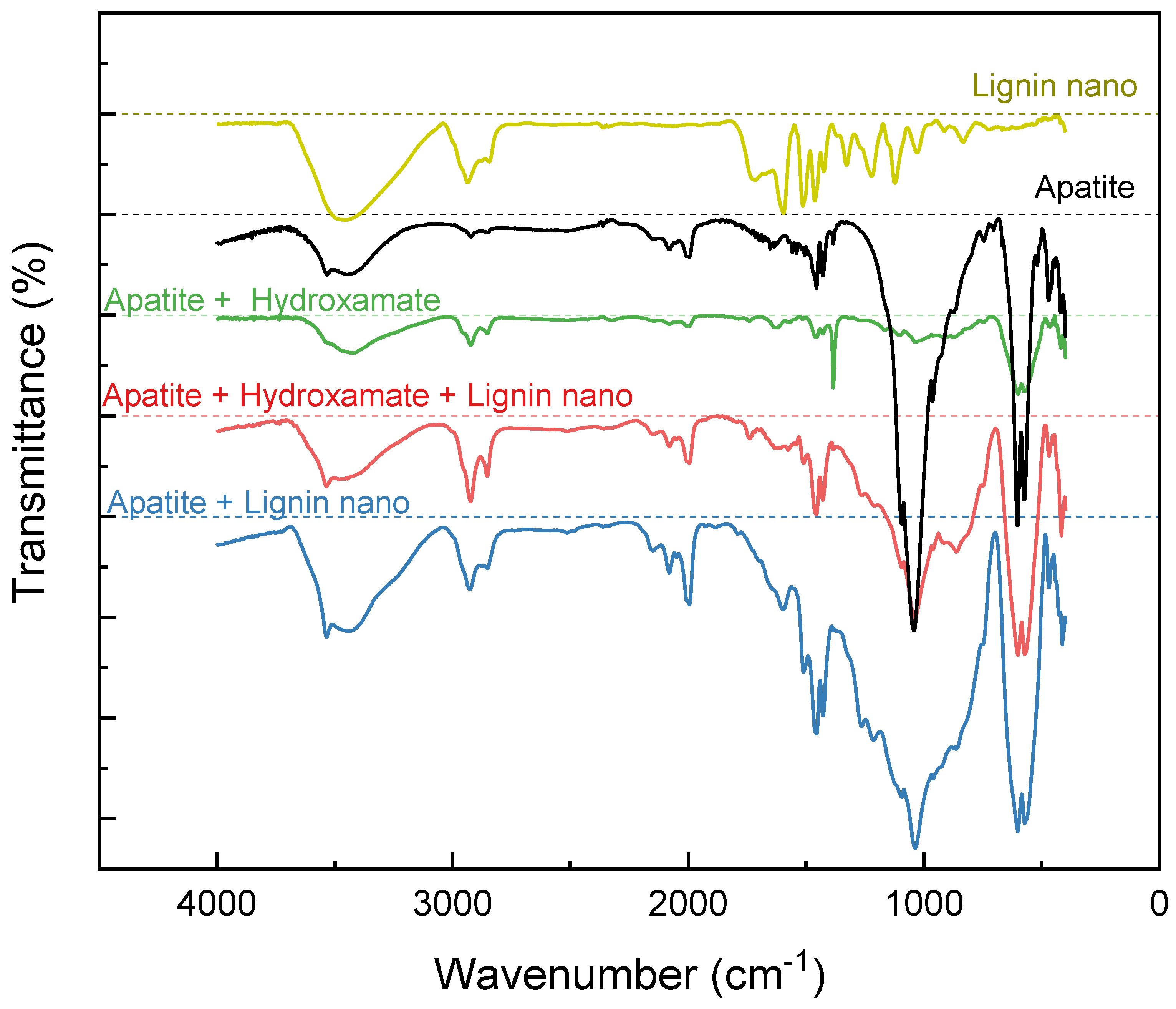

The enhancement of FT-IR peaks related to PO4 and OH species when apatite was treated with lignin nanoparticles indicate interaction of species possibly through hydrogen bonding, however a focused study is needed to confirm this and gain more insights regarding bonding type.

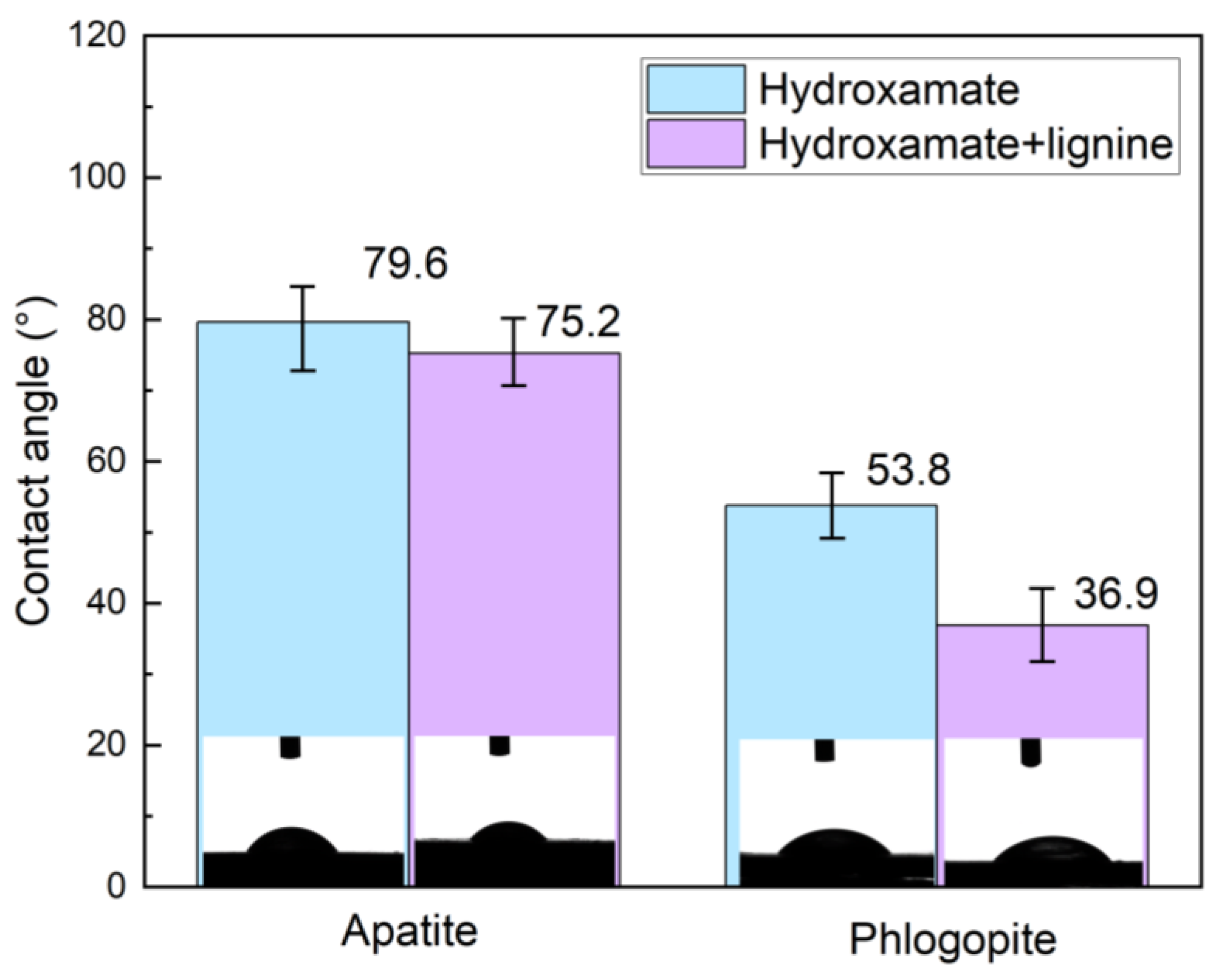

Lignin appears to increase the hydrophilicity of both apatite and phlogopite, with the effect being more pronounced in the latter, thereby improving their separation via flotation.

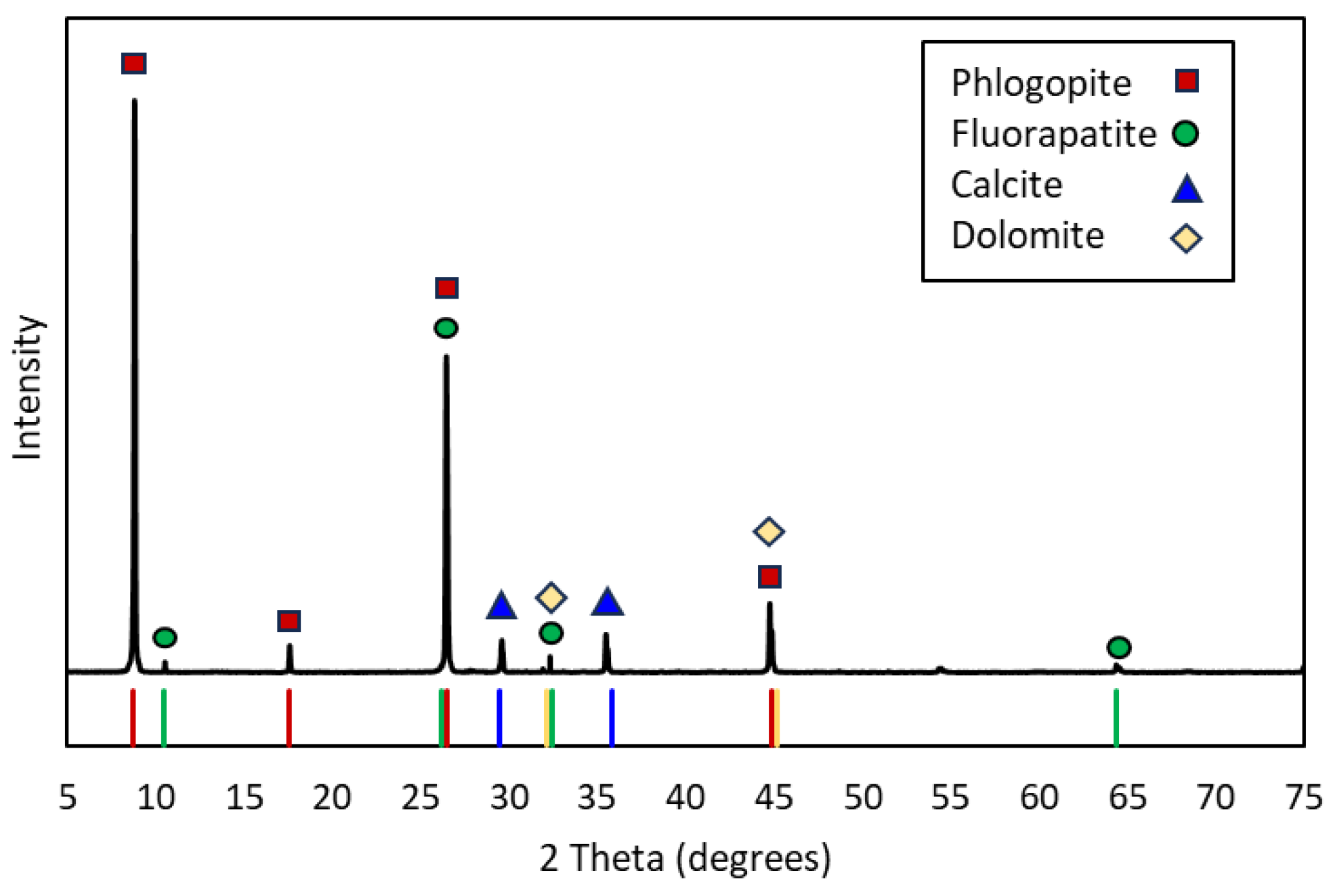

Figure 1.

Macroscopic (a) and microscopic view (b) of lignin nanoparticles.

Figure 1.

Macroscopic (a) and microscopic view (b) of lignin nanoparticles.

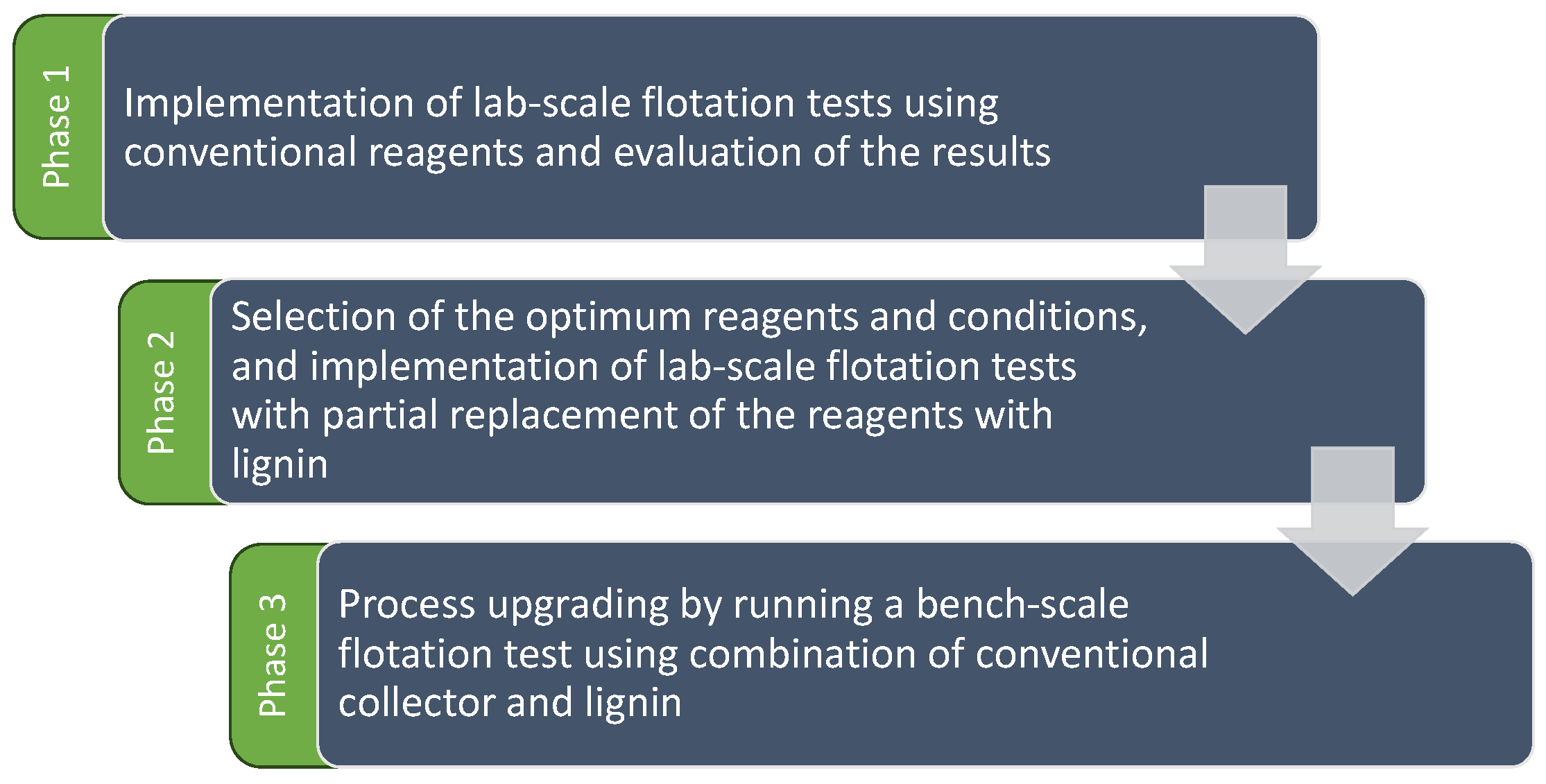

Figure 2.

Research methodology.

Figure 2.

Research methodology.

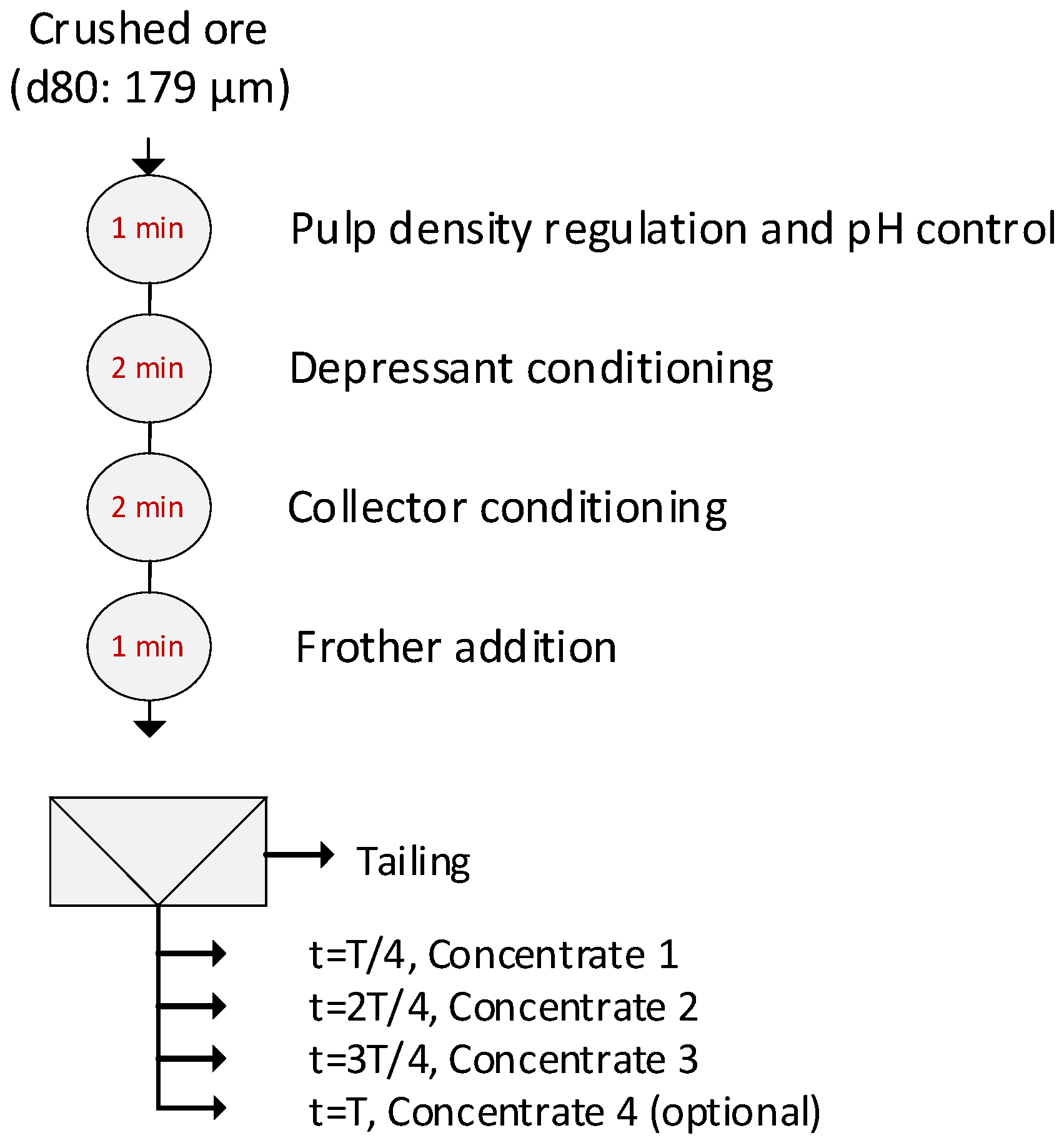

Figure 3.

Sequence of steps in conditioning and flotation.

Figure 3.

Sequence of steps in conditioning and flotation.

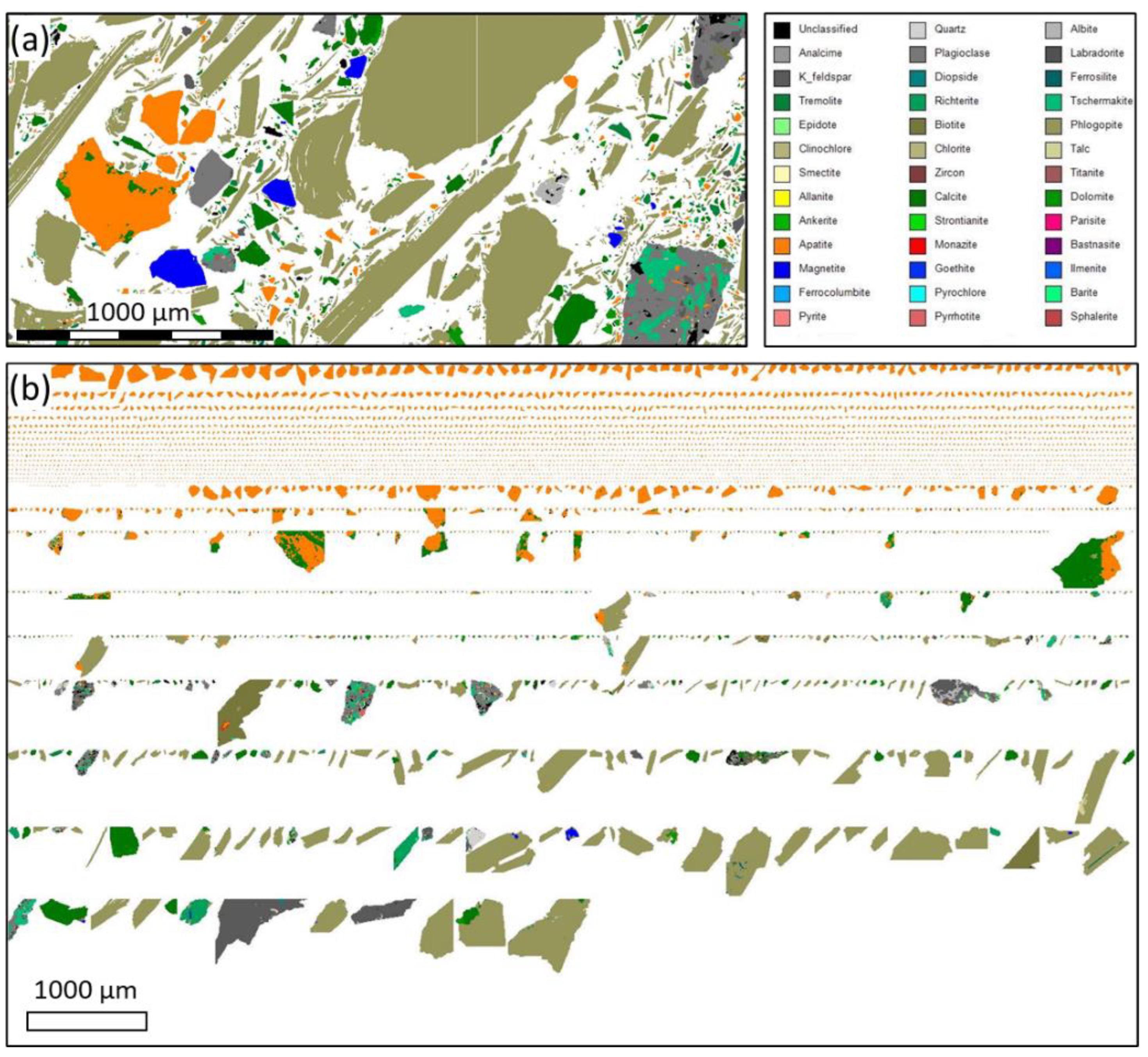

Figure 6.

Representative pseudo-colour particle map from the mineral liberation analysis of the ore, and (b) grains classification according to the apatite liberation degree.

Figure 6.

Representative pseudo-colour particle map from the mineral liberation analysis of the ore, and (b) grains classification according to the apatite liberation degree.

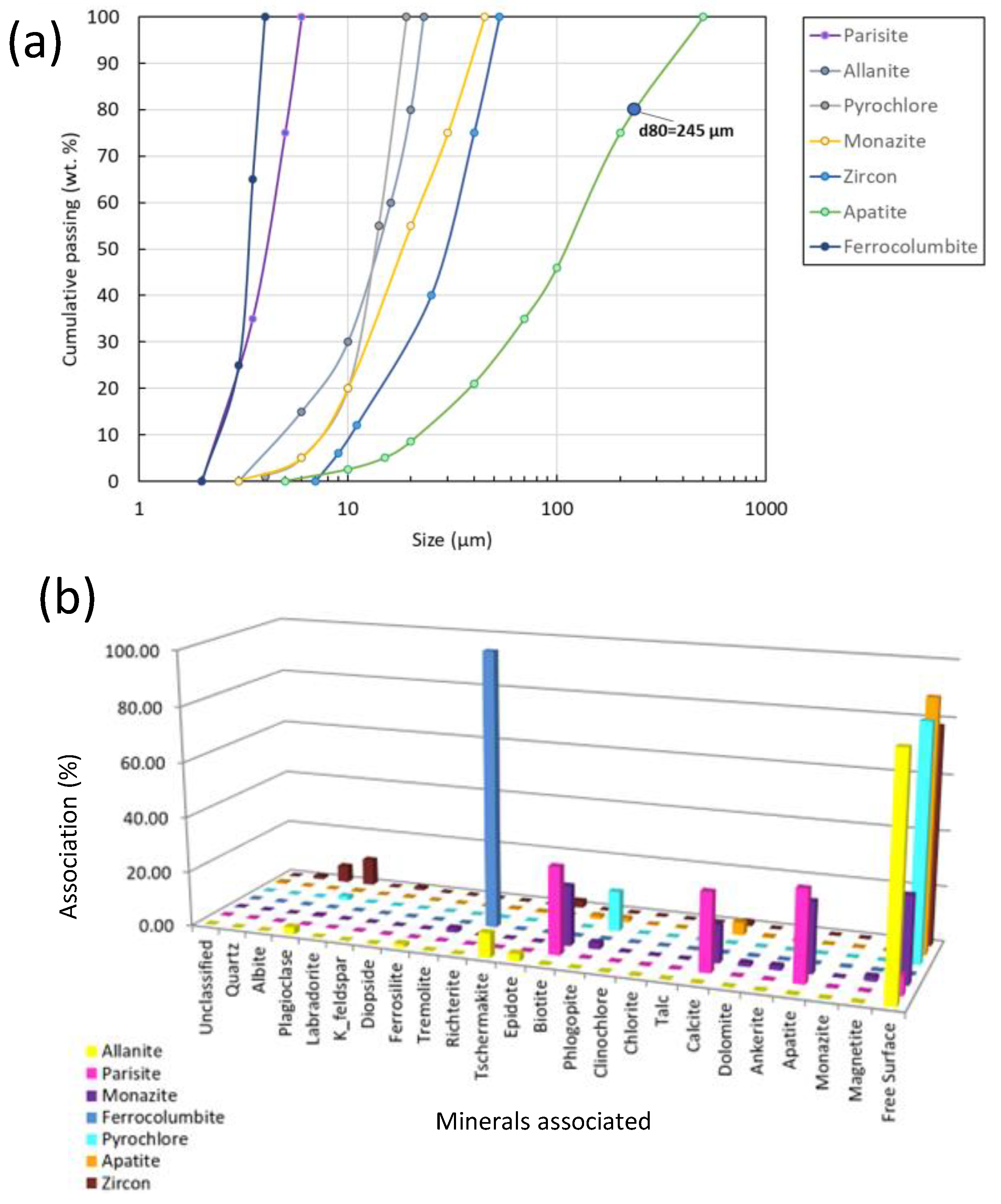

Figure 7.

Grains’ size distribution for apatite and the identified REE minerals (a), and REE minerals and apatite liberation and association degree with other minerals in the sample.

Figure 7.

Grains’ size distribution for apatite and the identified REE minerals (a), and REE minerals and apatite liberation and association degree with other minerals in the sample.

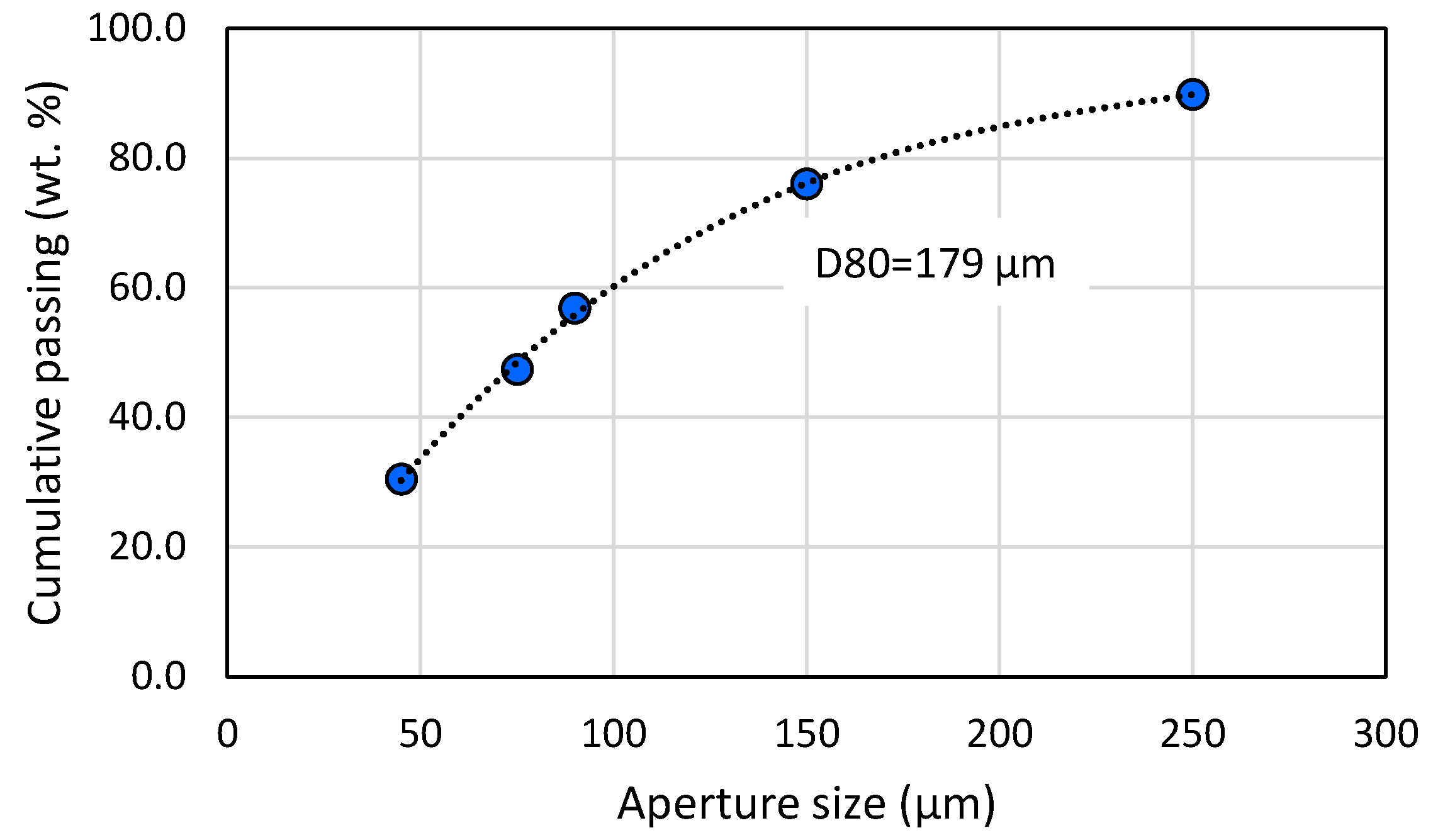

Figure 8.

Particle size distribution of the feed after grinding.

Figure 8.

Particle size distribution of the feed after grinding.

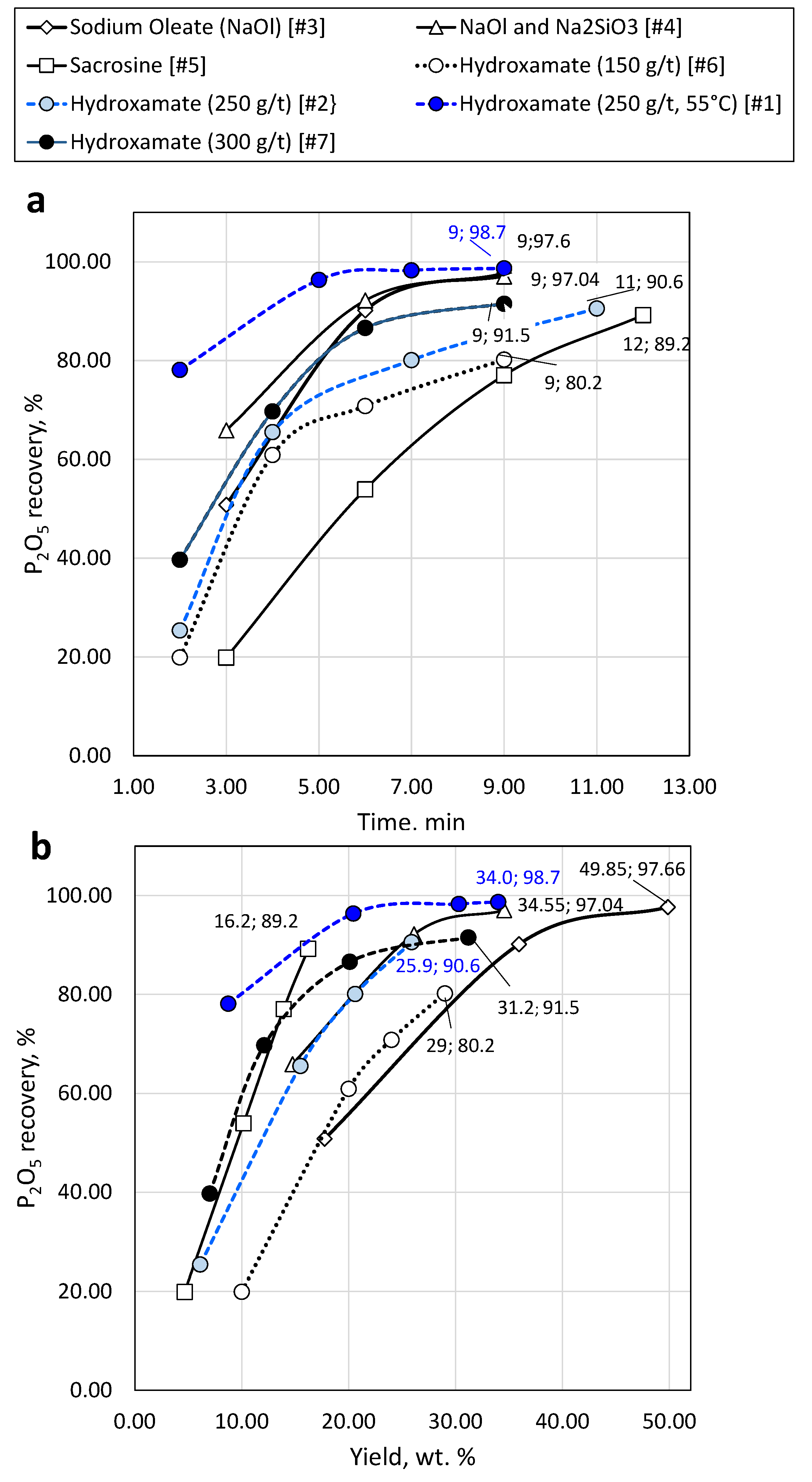

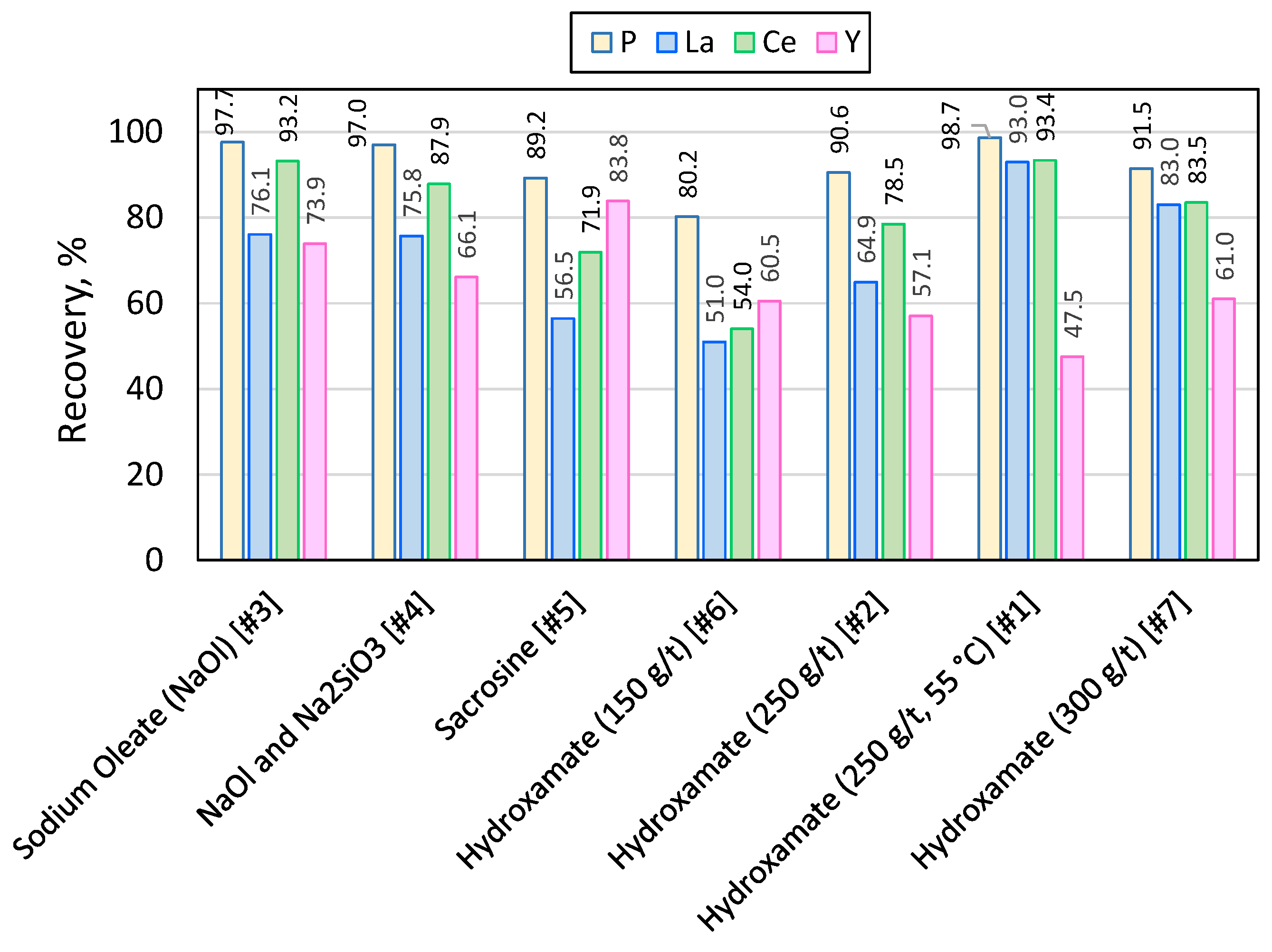

Figure 9.

Apatite recovery versus time (a) and mass concentrate yield (b) using different conventional collectors.

Figure 9.

Apatite recovery versus time (a) and mass concentrate yield (b) using different conventional collectors.

Figure 10.

Recovery of phosporus, lantanum, cerrium and ytrium in the combined concentrates for different collectors.

Figure 10.

Recovery of phosporus, lantanum, cerrium and ytrium in the combined concentrates for different collectors.

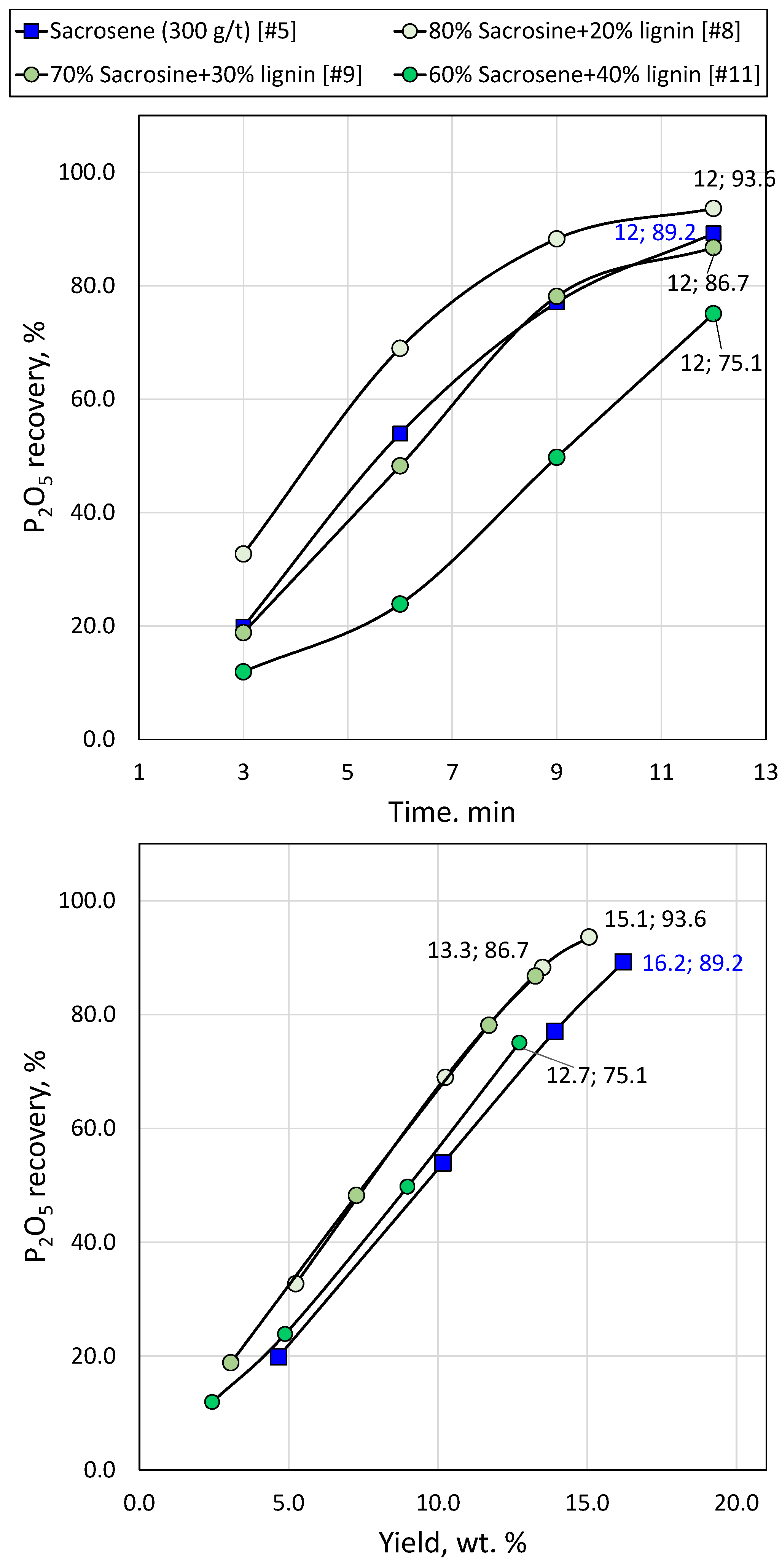

Figure 11.

Apatite recovery versus time (a) and mass concentrate yield (b) using sole sarcosine and sarcosine/lignin mixture at different ratio.

Figure 11.

Apatite recovery versus time (a) and mass concentrate yield (b) using sole sarcosine and sarcosine/lignin mixture at different ratio.

Figure 12.

Recovery of phosphorus and major REEs (lanthanum, cerium, yttrium) using solely sarcosine, and sacrosine/lignin mixtures .

Figure 12.

Recovery of phosphorus and major REEs (lanthanum, cerium, yttrium) using solely sarcosine, and sacrosine/lignin mixtures .

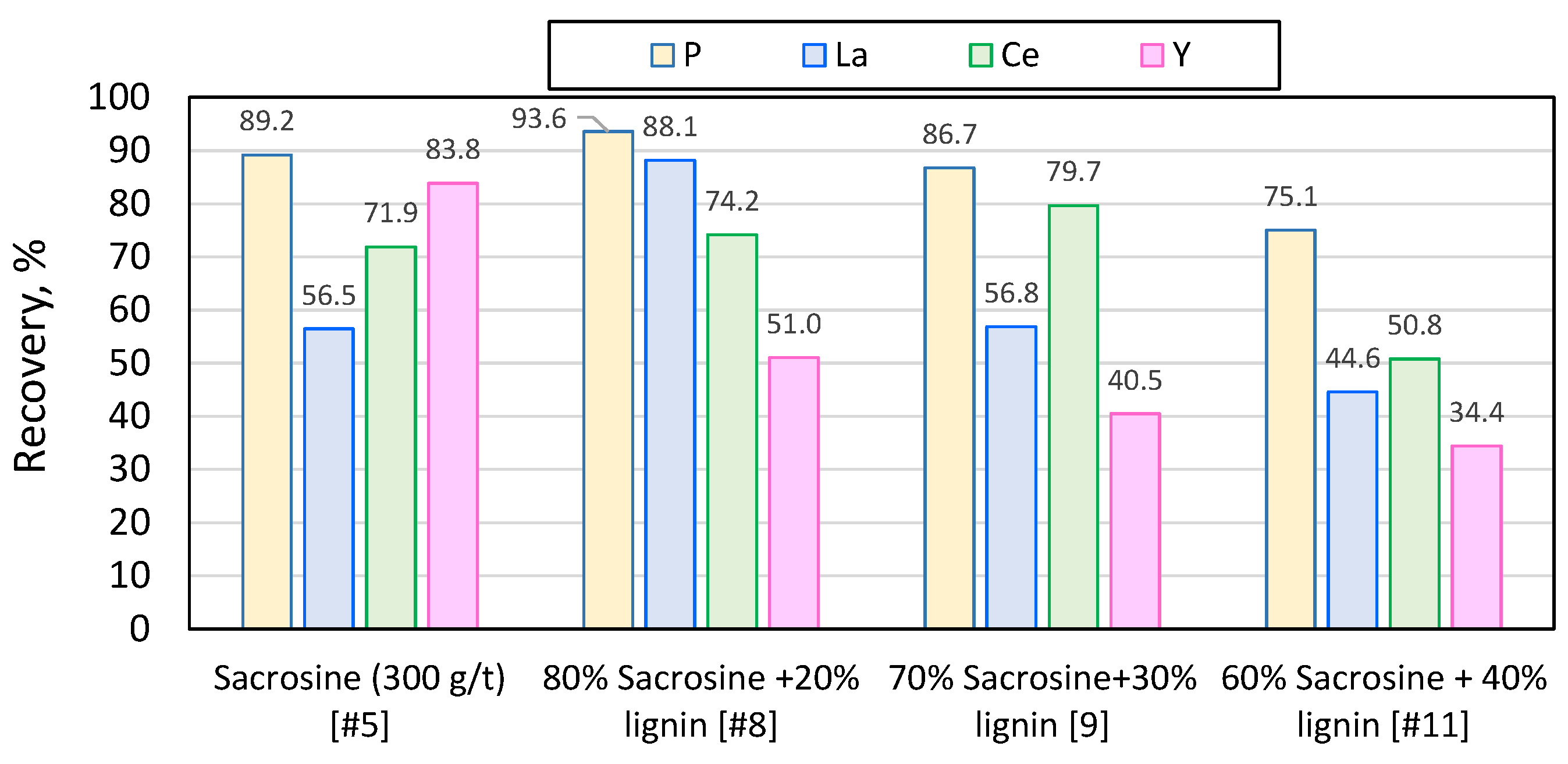

Figure 13.

Apatite recovery versus time (a) and mass concentrate yield (b) using sole hydroxamate and hydroxamate/lignin mixture at different ratio.

Figure 13.

Apatite recovery versus time (a) and mass concentrate yield (b) using sole hydroxamate and hydroxamate/lignin mixture at different ratio.

Figure 14.

Recovery of phosphorus and major REEs (lanthanum, cerium, yttrium) using solely hydroxamate, and hydroxamate/lignin mixtures .

Figure 14.

Recovery of phosphorus and major REEs (lanthanum, cerium, yttrium) using solely hydroxamate, and hydroxamate/lignin mixtures .

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra of apatite and lignin nanoparticles, and apatite treated with sole hydroxamate, hydroxamate and lignin nanoparticles mixture.

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra of apatite and lignin nanoparticles, and apatite treated with sole hydroxamate, hydroxamate and lignin nanoparticles mixture.

Figure 16.

Contact angle of single minerals treated using different chemicals.

Figure 16.

Contact angle of single minerals treated using different chemicals.

Figure 17.

Phosphorous, and Lanthanium and Cerrium grade and recovery using solely sacrosin in lab scale trials, and 80/20 sacrosine/lignin mixture in lab and bench scale trials with 4 and 13 L cell size and 1.5 kai and 5 kg feed, respectively.

Figure 17.

Phosphorous, and Lanthanium and Cerrium grade and recovery using solely sacrosin in lab scale trials, and 80/20 sacrosine/lignin mixture in lab and bench scale trials with 4 and 13 L cell size and 1.5 kai and 5 kg feed, respectively.

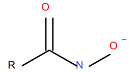

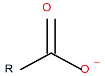

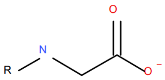

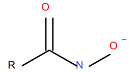

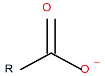

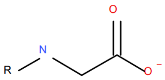

Table 1.

Tradename, formula and structure of the conventional collectors used [

41].

Table 1.

Tradename, formula and structure of the conventional collectors used [

41].

| Trade Name and Formula |

Molecular Structure of the Functional Group |

| Aero 6494©, anionic, alkyl hydroxamate-based collector |

|

| Sodium Oleate (NaOL), anionic, sodium salt of oleic acid |

|

| Berol A3©, sarcosine, a carboxylic acid coupled to a methylated nitrogen |

|

Table 2.

Lab-scale flotation tests’ reagents and conditions.

Table 2.

Lab-scale flotation tests’ reagents and conditions.

| Number |

Reagents (g/t) |

pH |

Time (m) |

Cell Size (L) |

Pulp Density (g/L) |

| Hydroxamate (Aero 6494®) |

Ling-chain fatty acid (NaOL) |

Sacrosine (Berol A3®) |

Organosolv Nanosized lignin |

Replacement ** |

Na2SiO3 |

Conditioning |

Flotation |

| 1* |

250 |

|

|

|

|

800 |

10 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 2 |

250 |

|

|

|

|

800 |

10 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 3 |

|

300 |

|

|

|

|

10.5 |

5 |

6 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 4 |

|

350 |

|

|

|

1400 |

10.5 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 5 |

|

|

300 |

|

|

|

11 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 6 |

150 |

|

|

|

|

800 |

10 |

5 |

12 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 7 |

300 |

|

|

|

|

800 |

10 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 8 |

|

|

240 |

60 |

20 |

|

11 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 9 |

|

|

210 |

90 |

30 |

|

11 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 10 |

210 |

|

|

90 |

30 |

800 |

10 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 11 |

|

|

180 |

120 |

40 |

|

11 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

| 12 |

200 |

|

|

200 |

50 |

800 |

10 |

5 |

9 |

2.5 |

300 |

Table 3.

Chemical analysis of the feed.

Table 3.

Chemical analysis of the feed.

| Oxide |

Content (wt. %) |

| SiO2

|

32.4 |

| MgO |

17.90 |

| CaO |

17.17 |

| Al2O3

|

7.52 |

| FeO |

6.88 |

| K2O |

6.51 |

| P2O5

|

3.75 |

| Na2O3

|

0.40 |

| C |

3.04 |

| La |

0.01 |

| Ce |

0.019 |

| Y |

0.002 |

Table 4.

Mineralogical composition of the ore.

Table 4.

Mineralogical composition of the ore.

| Mineral |

Content (wt. %) |

| K-feldspar |

2.28 |

| Phlogopite (KMg3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2) |

57.37 |

| Biotite (K(Mg,Fe)3(AlSi3)O10(OH)2) |

3.18 |

| Apatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH, F, Cl) |

8.87 |

| Calcite (CaCO3) |

16.68 |

| Dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2

|

2.45 |

| Magnetite (Fe3O4) |

0.74 |

Table 5.

REEs content in the concentrates obtained from the flotation of the ore using conventional reagents. For comparison purposes, the concentration of the elements in the feed are also given in the last raw.

Table 5.

REEs content in the concentrates obtained from the flotation of the ore using conventional reagents. For comparison purposes, the concentration of the elements in the feed are also given in the last raw.

| Flotation Experiment |

REEs Grade in Final Concentrate, % |

| La |

Ce |

Y |

| Sodium Oleate (NaOl) [#3] |

0.0192 |

0.0413 |

0.0031 |

| NaOl and Na2SiO3 [#4] |

0.0237 |

0.0550 |

0.0037 |

| Sacrosine [#5] |

0.0402 |

0.0926 |

0.0054 |

| Hydroxamate (150 g/t) [#6] |

0.0498 |

0.1046 |

0.0041 |

| Hydroxamate (250 g/t) [#2] |

0.0265 |

0.0627 |

0.0038 |

| Hydroxamate (250 g/t, 55 °C) [#1] |

0.0257 |

0.0550 |

0.0032 |

| Hydroxamate (300 g/t) [#7] |

0.0299 |

0.0595 |

0.0037 |

| In the feed |

0.0098 |

0.0190 |

0.0020 |

Table 6.

FTIR peaks identified under apatite treatment with sole hydroxamate, hydroxamate and lignin nanoparticles mixture and sole lignin nanoparticles.

Table 6.

FTIR peaks identified under apatite treatment with sole hydroxamate, hydroxamate and lignin nanoparticles mixture and sole lignin nanoparticles.

| Wavelength (cm-1) |

Mode |

Apatite |

Lignin nano |

Apatite + Hydroxamate |

Apatite + Hydroxamate + Lignin nano |

Apatite + Lignin nano |

Reference |

| Intensity (w: weak, m: medium, s: strong) |

| 468 |

Deformation vibration of P-O |

m |

- |

w |

w |

m |

[36,52] |

| 573 |

m |

- |

w |

m |

m |

[52,53] |

| 600 |

m |

- |

w |

m |

m |

[52,53] |

| 742 |

OH vibration band |

w |

- |

w |

w |

w |

[54] |

| 853 |

C-H out-of-plane deformation of syringyl (S) unit |

w |

m |

- |

m |

m |

[55] |

| 956 |

Symmetric stretching of PO4 group |

w |

- |

- |

w |

w |

[54] |

| 1021 |

Aromatic C-H in plane deformation for S units |

s |

- |

w |

s |

s |

[36] |

| 1000-1150 |

Asymmetric stretching of the PO4 group |

s |

- |

w |

s |

s |

[53,54] |

| 1214 |

Absorbance of guaiacyl |

- |

m |

- |

w |

w |

[36] |

| 1326 |

C=O bending of S unit |

- |

m |

- |

w |

w |

[36] |

| 1385 |

OH vibration band |

w |

- |

s |

- |

- |

[54] |

| 1460 |

C-H bending |

m |

- |

w |

m |

s |

[36] |

| 1512 |

C=C aromatic skeletal vibration |

|

- |

- |

w |

w |

[36] |

| 1590 |

|

- |

w |

- |

m |

[36] |

| 1623 |

C=N stretching |

w |

- |

m |

w |

- |

[56] |

| 1999 |

PO4

|

m |

- |

w |

m |

s |

[54] |

| 2079 |

PO4

|

w |

- |

- |

w |

m |

[54] |

| 2855 |

C-H stretching in -CH2 and -CH3

|

w |

- |

w |

m |

w |

[36] |

| 2926 |

w |

- |

w |

s |

m |

| 3420 |

O-H stretching |

w |

- |

w |

w |

m |

[36] |

| 3538 |

OH vibration band |

w |

- |

- |

w |

m |

[54] |

Table 7.

P and Mg distribution in concentrates and tailings, and SI and SE values for all laboratory flotation tests.

Table 7.

P and Mg distribution in concentrates and tailings, and SI and SE values for all laboratory flotation tests.

| Number. |

Reagents |

Conv. collector Replacement (%) |

P recovery in Conc. (%) |

Mg recovery in Conc. (%) |

Mg recovery in Tail (%) |

Selectivity Index |

Separation efficiency |

| 1 |

Hydroxamate diluted at 55 °C |

- |

98.7 |

13.6 |

86.4 |

5.2 |

85.1 |

| 2 |

Hydroxamate |

- |

90.6 |

13.7 |

86.3 |

0.7 |

76.9 |

| 3 |

Fatty acid |

- |

97.7 |

38.3 |

61.7 |

0.9 |

59.4 |

| 4 |

Fatty acid, Na2SiO3

|

- |

97 |

46.2 |

53.8 |

0.5 |

50.8 |

| 5 |

Sacrosine |

- |

89.2 |

6.7 |

93.3 |

1.3 |

82.5 |

| 6 |

Hydroxamate, Na2SiO3

|

- |

80.2 |

59.3 |

40.7 |

0.0 |

20.9 |

| 7 |

Hydroxamate, Na2SiO3

|

- |

91.5 |

8.9 |

91.1 |

1.2 |

82.6 |

| 8 |

Sacrosine, lignin |

20 |

93.6 |

4.8 |

95.2 |

3.1 |

88.8 |

| 9 |

Sacrosine, lignin |

30 |

86.7 |

5.5 |

94.5 |

1.2 |

81.2 |

| 10 |

Hydroxamate, lignin, Na2SiO3

|

30 |

95.4 |

18.6 |

81.4 |

1.0 |

76.8 |

| 11 |

Sacrosine, lignin |

40 |

75.1 |

4.7 |

95.3 |

0.7 |

70.4 |

| 12 |

Hydroxamate, lignin, Na2SiO3

|

50 |

86.9 |

5.9 |

94.1 |

1.2 |

81 |