Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Oil Flavoring

2.2. Oil Ageing Test

2.3. Determination of Oil Parameters

2.3.1. Density

2.3.2. Quality Indices

2.3.3. Pigments Quantification

2.3.4. Color Determination

2.3.5. Total Phenols Determination

2.3.6. Fatty Acids Determination

2.3.7. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.4. Consumer Survey

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of the Method of Aromatization on the Physicochemical Characterization of Flavored Oils

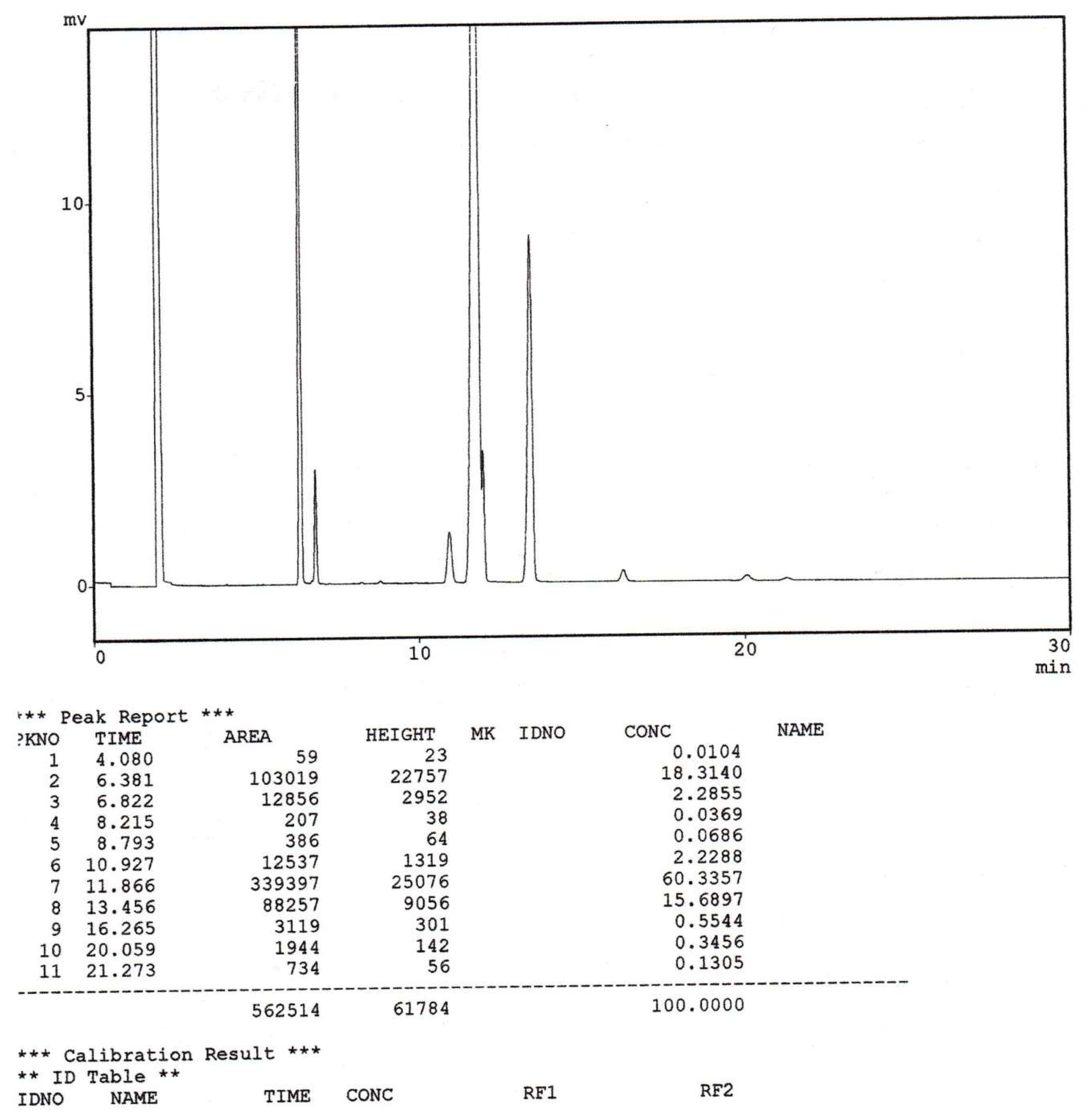

3.2. Fatty Acid Analysis

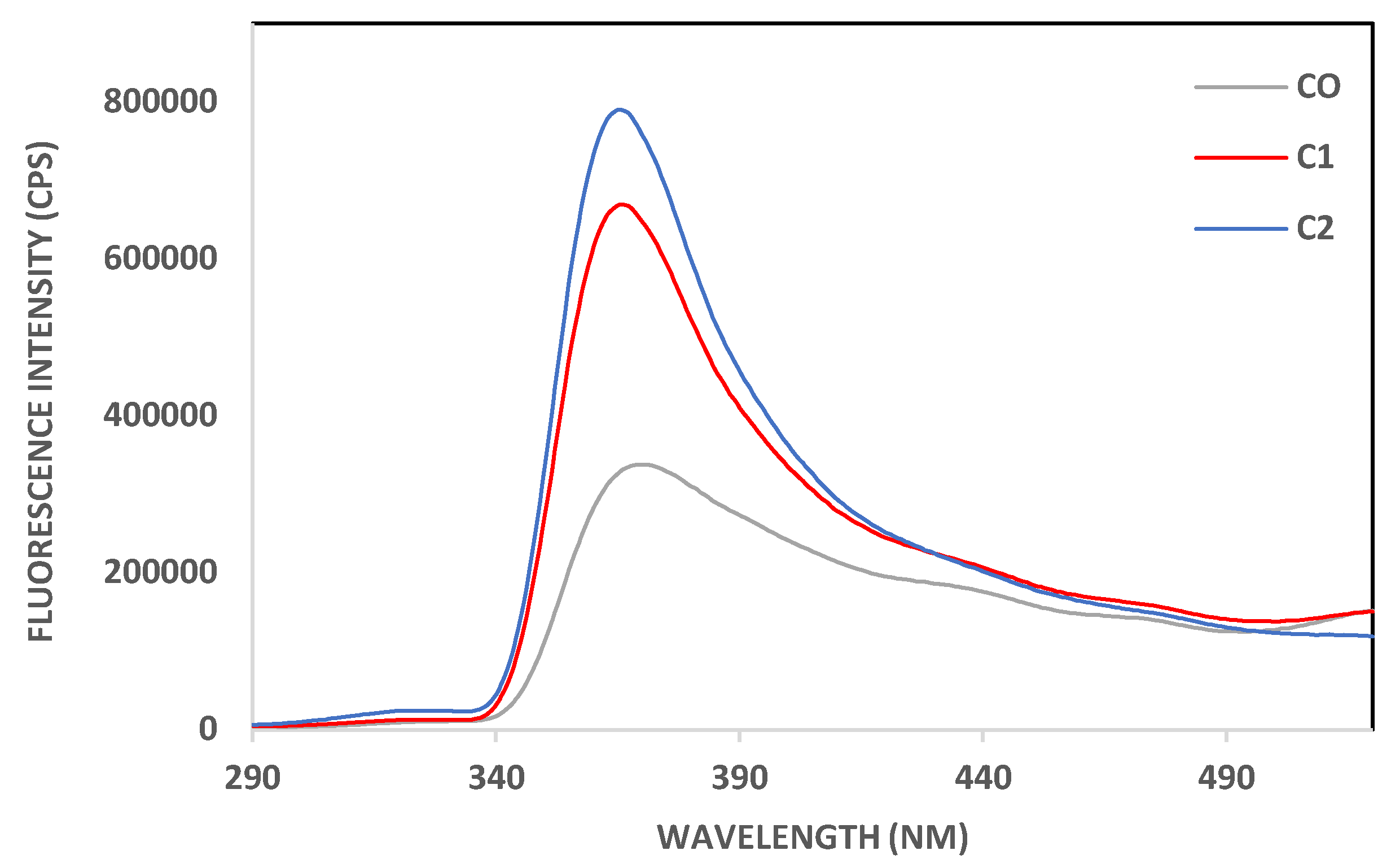

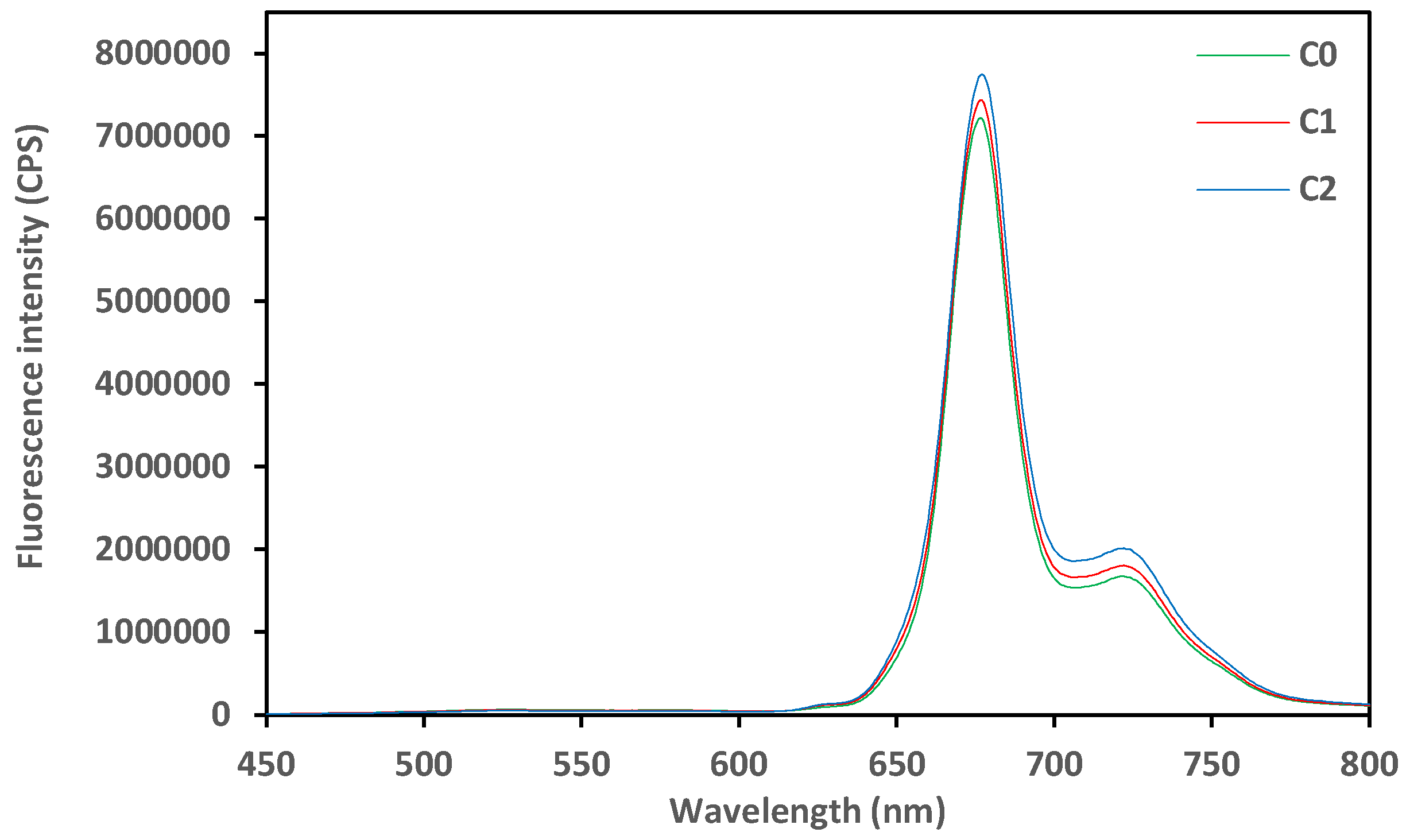

3.3. Emission Fluorescence Spectra of Polyphenols and Chlorophylls for Aromatized Oils

3.4. Effect of Ageing on the Quality of Olive Oils

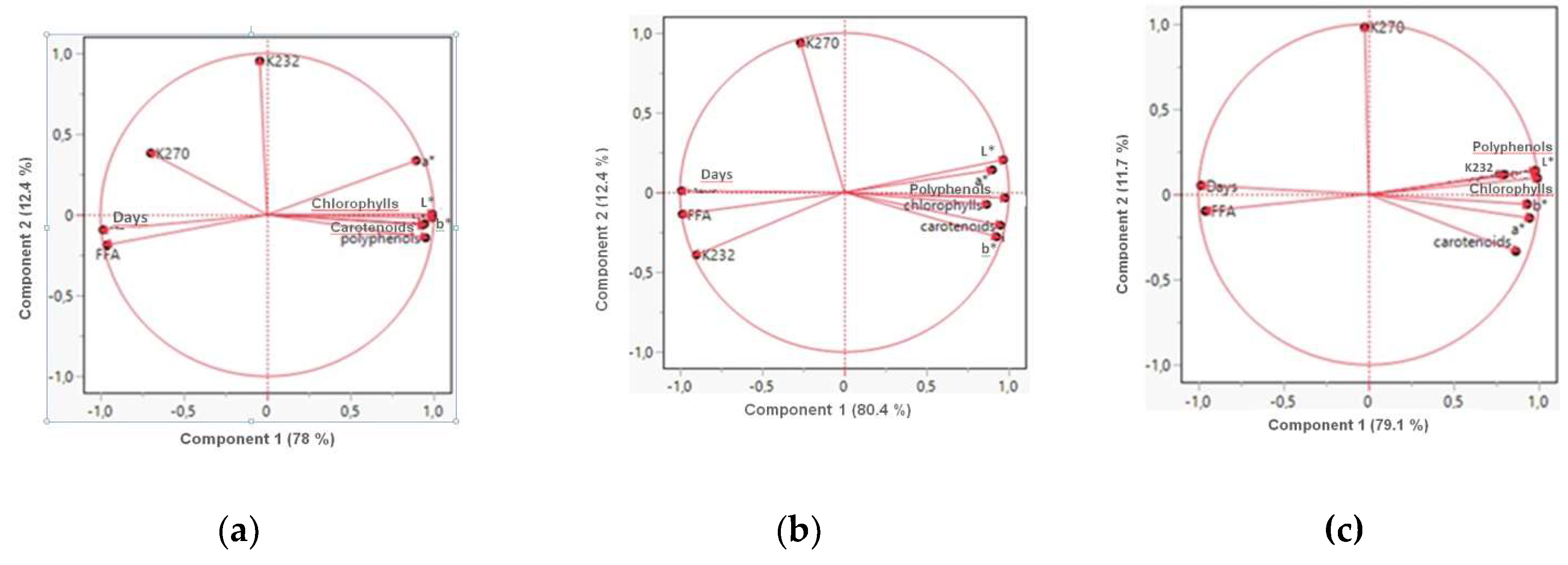

3.5. Principal Component Analysis

3.6. Consumer Survey

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical approval/consent form

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Chromatogram

References

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomized trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72(1), 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumuzachi, O.; Kieserling, H.; Rohn, S.; Mocan, A. The impact of oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and tyrosol on cardiometabolic risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memmola, R.; Petrillo, A.; Di Lorenzo, S.; Altuna, S.C.; Habeeb, B.S.; Soggiu, A. Correlation between olive oil intake and gut microbiota in colorectal cancer prevention. Nutrients 2022, 14(18), 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazlollahi, A.; Motlagh Asghari, K., Aslan, C.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Araj-Khodaei, M.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Karamzad, N.; Kolahi, A.A. and Safiri, S. The effects of olive oil consumption on cognitive performance: a systematic review. 2023, 10, 1218538. [CrossRef]

- Tzekaki, E.E.; Tsolaki, M.; Pantazaki, A.A.; Geromichalos, G.; Lazarou, E.; Kozori, M.; et al. The pleiotropic beneficial intervention of olive oil intake on the Alzheimer’s disease onset via fibrinolytic system. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 150, 111344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddoumi, A.; Denney, T.S.Jr.; Deshpande, G.; Robinson, J.L.; Beyers, R.J.; Redden, D.T.; Praticò, D.; Kyriakides, T.C.; Lu, B.; Kirby, A.N.; Beck, D.T.; & Merner, N.D. Extra-virgin olive oil enhances the blood–brain barrier function in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients, 2022, 14(23), 5102. [CrossRef]

- Rey-Giménez, R.; Sánchez-Gimeno, A.C. Effect of cultivar and environment on chemical composition and geographical traceability of Spanish olive oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2024, 101(4), 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.C.; Vieitez, I.; Gámbaro, A. Sensory and physicochemical characteristics of Uruguayan picual olive oil obtained from olives with different ripening indexes. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A.; Caporaso, N.; Sacchi, R. Flavor chemistry of virgin olive oil: an overview. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11(4), 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trade standard applying to olive oils and olive pomace oils COI/T.15/NC No 3/Rev. 16 June 2021.

- Karacabey, E.; Özkan, G.; Dalgıç, L.; Sermet, S.O. Rosemary aromatization of extra virgin olive oil and process optimization including antioxidant potential and yield. TURJAF, 2016, 4(8), 628-635.

- Barreca, S.; La Bella, S.; Maggio, A.; Licata, M.; Buscemi, S.; Leto, C.; Pace, A.; Tuttolomondo, T. Flavouring extra-virgin olive oil with aromatic and medicinal plants essential oils stabilizes oleic acid composition during photo-oxidative stress. Agriculture 2021, 11, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, S.; Rodrigues, N.; Peres, A.M.; Pereira, J.A. Flavoured and fortified olive oils-pros and cons. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Terracone, C.; Gambacorta, G.; La Notte, E. Changes in quality indices, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of flavored olive oils during storage. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 86(11), 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoui, M.; Flamini, G.; Souid, S.; Bendini, A.; Barbieri, S.; Gharbi, I. How the addition of spices and herbs to virgin olive oil to produce flavored oils affects consumer acceptance. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11(6), 1934578X1601100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, D.; Acar, A. Aromatization of olive oil with ginger and turmeric powder or extracts by the co-processing and maceration methods. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2024, 126, ex2300074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, F.; Durante, V.; Varva, G.; Silletti, R.; Previtali, M.A.; Viggiani, I.; Squeo, G.; Summo, C.; Pasqualone, A.; Gomes, T.; Baiano, A. , Effect of infusion of spices into the oil vs combined malaxation of olive paste and spices on quality of naturally flavoured virgin olive oils, Food Chem. 2016, 202, 221-228. [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.; Abdallah, M.; Taamali, W.; Genovese, A.; Balivo, A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Trabelsi, N. Enhancing olive oil quality through an advanced enrichment process utilizing ripe and fallen fruits. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Pouramin, S.; Adinepour, F.; Haghani, S.; Jafari, S.M. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with clove essential oil: Characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.V.; De Lima, A.D.C. A.; Silva, M.G.; Caetano, V.F.; De Andrade, M.F.; Da Silva, R.G.C.; De Moraes Filho, L.E.P.T.; Lima Silva, I.D.D.; Vinhas, G.M. Clove essential oil and eugenol: A review of their significance and uses. Food Biosci. 2024, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Bai, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of clove essential oil against foodborne pathogens. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 173, 114249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Pandey, V.; Shams, R.; Singh, R.; Dar, A. H.; Pandiselvam, R.; Rusu, A. V.; et al. A comprehensive review on clove (Caryophyllus aromaticus L.) essential oil and its significance in the formulation of edible coatings for potential food applications. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 987674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indiarto, R.; Herwanto, J.A.; Filianty, F.; Lembong, E.; Subroto, E.; Muhammad, D.R.A. Total phenolic and flavonoid content, antioxidant activity and characteristics of a chocolate beverage incorporated with encapsulated clove bud extract. CyTA – J. Food, 2024, 22 (1). [CrossRef]

- Ricardo-Rodrigues, S.; Rouxinol, M.I.; Agulheiro-Santos, A.C.; Potes, M. E.; Laranjo, M.; Elias, M. The Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potential of Thyme and Clove Essential Oils for Meat Preservation—An Overview. Appl. Biosci. 2024, 3(1), 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.T.; Orzali, L.; Manetti, G.; Magnanimi, F.; Matere, A.; Bergamaschi, V.; Grottoli, A.; Bechini, S.; Riccioni, L.; Aragona, M. Rapid molecular assay for the evaluation of clove essential oil antifungal activity against wheat common bunt. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1130793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, F.; Li, Q.; Huang, J.; Ju, J. Antifungal mechanism of essential oil against foodborne fungi and its application in the preservation of baked food. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 2024, 64(9), 2695–2707. [CrossRef]

- Idowu, S.; Adekoya, A.E.; Igiehon, O.O.; Idowu, A.T. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) spices: A review on their bioactivities, current use, and potential application in dairy products. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 3419–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, N.; Marotta, S.M.; Giarratana, F.; Taamali, A.; Zarrouk, M.; Ziino, G.; Giuffrida, A. Use of Tunisian flavored olive oil as anisakicidal agent in industrial anchovy marinating process. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98(9), 3446–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA (2023) Tunisia: Oilseeds and products annual. https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/tunisia-oilseeds-and-products-annual-7. Accessed 30 June 2023.

- Debbabi, O.S.; Ben Amar, F.; Rahmani, S.M.; Taranto, F.; Montemurro, C.; Miazzi, M.M. The status of genetic resources and olive breeding in Tunisia. Plants 2022, 11(13), 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latino, M.E.; De Devitiis, B.; Corallo, A.; Viscecchia, R.; Bimbo, F. Consumer Acceptance andPreference for Olive Oil Attributes—A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, J.P. Manuel d’analyse des Corps Gras; Tokyo University of Fisheries: Tokyo, Japan, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Determination of free fatty acids, cold method, code COI/T.20/Doc. No 34/Rev. 1 2017. International Olive Council (IOC).Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/(accessed the 1/01/2025).

- Determination of peroxide value. Code COI/T.20/Doc. No 35/Rev.1 2017 International Olive Council (IOC). Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/(accessed the 1/01/2025).

- Spectrophotometric investigation in the ultraviolet. Code COI/T.20/Doc. No 19/Rev. 5 2019. International Olive Council (IOC). Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/(accessed the 1/01/2025).

- Martakos, I.; Kostakis, M.; Dasenaki, M.; Pentogennis, M.; Thomaidis, N. Simultaneous determination of pigments, tocopherols, and squalene in Greek olive oils: A study of the influence of cultivation and oil-production parameters. Foods 2020, 9(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, I.; BenAmira, A.; Khemakem, I.; Attia, H.; Ennouri, M. Effect of Opuntia ficus-indica flowers maceration on quality and on heat stability of olive oil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1502–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, R.B.; Hadjkacem, B.; Ayadi, M.; Ikram, B.A.; Feki, A.; Gargouri, J. ;...& Allouche, N. Phytochemical profile of Tunisian Pistacia lentiscus fruits oil: Antioxidant, antiplatelet, and cytotoxic activities assessment. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2024, 2300274.

- Aljobair, M.O. Physicochemical, nutritional, and sensory quality and storage stability of cookies: effect of clove powder. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25(1), 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambacorta, G.; Faccia, M.; Pati, S.; Lamacchia, C.; Baiano, A.; La Notte, E. Changes in the chemical and sensorial profile of extra virgin olive oils flavored with herbs and spices during storage. J. Food Lipids 2006, 14, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, R.; Della, M.D.; Paduano, A.; Caporaso, N.; Genovese, A. Characterisation of lemon- flavoured olive oils. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amar, F.; Guellaoui, I.; Ayadi, M.; Elloumi, O.; Triki, M. A.; Boubaker, M. “‘Zeitoun Ennour’: A new olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivar in Tunisia with high oil quality”, Genetic Resources, 2021, 2(4), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Singh,M.;Botosoa,E.; Karoui, R. MonitoringofAntioxidant Efficacy ofMangrove-Derived PolyphenolsinLinseedOilby Physicochemical andFluorescence Methods. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 192. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V. K.; Srivastava, S.; Dash, K. K.; Singh, R.; Dar, A. H.; Singh, T. ;... & Kovacs, B. Bioactive properties of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) essential oil nanoemulsion: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10(1), e22437. [CrossRef]

- DGPA. (2021). Data of the General Directorate of Agricultural Production. Republic of Tunisia: Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources and Fisheries http://www.agridata.tn/organization/direction-generale-de-la-production-agricole?organization=direction-generale-de-la-production-agricole&page=2.

- Chahdoura, H., Mzoughi, Z., Ziani, B. E., Chakroun, Y., Boujbiha, M. A., Bok, S. E., ... & Mosbah, H. (2023). Effect of Flavoring with Rosemary, Lemon and Orange on the Quality, Composition and Biological Properties of Olive Oil: Comparative Study of Extraction Processes. Foods 2023, 12(6), 1301. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | CO | C1 | C2 | AOMC1 | AOMC2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 0.908±0.005a | 0.915±0.002a | 0.917±0.002a | 0.914±0.005a | 0.916±0.002a | |

| Color | L | 21.81±0.043a | 18.37±0.036b | 20.223±0.02c | 10.826±0.005d | 10.245±0.034e |

| a* | -0.843±0.015a | -0.843±0.661a | -0.378±0.021b | 0.226±0.01c | 0.54±0.122d | |

| b* | 13.503±0.047a | 11.393±0.072b | 12.756±0.083c | 2.483±0.156d | 2.606±0.176d | |

| FFA (%) | 0.175±0.007a | 0.185±0.005a | 0.225±0.001b | 0.38±0.012c | 0.41±0.014d | |

| PV (meq/kg) | 11.208±0.325a | 11.542±0.477a | 12.458±0.409a | 15.645±0.161b | 17.865±0.163c | |

| K232 | 1.651±0.001a | 1.928±0.008b | 2.245±0.001c | 2.135±0.010d | 2.889±0.014e | |

| K270 | 0.136±0.006a | 0.210±0.003b | 0.249±0.014c | 0.256±0.002c | 0.262±0.007c | |

| Chlorophylls (mg/kg) | 6.056±0.01a | 4.124±0.04b | 4.371±0.013c | 2.712±0.029d | 1.984±0.019e | |

| Carotenoïds (mg/kg) | 1.786±0.028a | 1.874±0.010a | 1.960±0.002b | 1.284±0.04c | 1.048±0.029d | |

| Total phenols (mg GAE/kg) | 385.703±0.02a | 517.88±0.03b | 668.72±0.04c | 451.62±0.01d | 587.64±0.01e | |

| Fatty acids | C0 | C1 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palmitic acid (C16 :0) | 18.048±0.314a | 17.871±0.055a | 17.809±0.037a |

| Palmitoleic acid (C16 :1) | 2.291±0.040a | 2.270±0.064a | 2.237±0.019a |

| Heptadecanoic acid (C17 :0) | 0.0349±0.001a | 0.035±0.001a | 0.035±0.0007a |

| Heptadecenoic acid (C17 :1) | 0.274±0.353a | 0.066±0.001a | 0.066±0.000a |

| Stearic acid (C18 :0) | 2.217±0.028a | 2.211±0.045a | 2.23±0.005a |

| Oleic acid (C18 :1) | 60.434±0.278a | 60.512±0.201a | 60.576±0.045a |

| Linoleic acid (C18 :2) | 15.821±0.015a | 15.939±0.054b | 15.946±0.020b |

| Linolenic acid (C18 :3) | 0.564±0.006a | 0.553±0.015ac | 0.546±0.002bc |

| Arachidic acid (C20 :0) | 0.360±0.022a | 0.377±0.006ac | 0.39±0.006bc |

| Eicosenoic acid (C20 :1) | 0.147±0.015a | 0.151±0.010ab | 0.154±0.010ac |

| Saturated fatty acid (SFA) | 20.670±0.266a | 20.505±0.082a | 20.473±0.046a |

| Monounsaturated fatty acid | 63.148±0.507a | 63.002±0.125a | 63.034±0.029a |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acid | 16.386±0.019a | 16.493±0.069ab | 16.493±0.022b |

| Storage (days) | Olive oil samples | FFA (%) | K232 | K270 | Chlorophylls (mg/kg) | Carotenoids (mg/kg) | Total phenolics (mg GAE/kg) |

| 0 | C0 | 0.175±0.01a | 1.652±0.10a | 0.136±0.02a | 6.056±0.07a | 1.786±0.03a | 385.703±5.601a |

| C1 | 0.185±0.01b | 1.928±0.05b | 0.211±0.03b | 4.123±0.06b | 1.874±0.01a | 517.88±13b | |

| C2 | 0.225±0.01c | 2.245±0.06c | 0.281±0.03c | 4.371±0.06b | 1.960±0.02a | 668.72±14c | |

| 21 | C0 | 0.44±0.01a | 1.789±0.09a | 0.175±0.02a | 4.193±0.07a | 1.435±0.09a | 322.349±13.383a |

| C1 | 0.485±0.01b | 1.909±0.07a | 0.243±0.01b | 3.707±0.04a | 1.316±0.02a | 511.995±16.619b | |

| C2 | 0.57±0.03c | 2.127±0.04b | 0.330±0.03c | 3.970±0.09a | 1.102±0.03b | 650.317±15.155c | |

| 35 | C0 | 0.61±0.02a | 1.719±0.03a | 0.207±0.01a | 3.646±0.16a | 1.198±0.02a | 283.270±13.083a |

| C1 | 0.60±0.02a | 1.862±0.06b | 0.282±0.02b | 3.490±0.01a | 1.216±0.01a | 498.948±17.380b | |

| C2 | 0.66±0.01b | 2.088±0.07c | 0.363±0.01c | 3.456±0.07a | 1.021±0.02b | 605.933±19.244c | |

| 56 | C0 | 0.92±0.01a | 1.728±0.05a | 0.296±0.01a | 3.040±0.17a | 0.970±0.02a | 265.425±12.99a |

| C1 | 0.935±0.02a | 1.962±0.08a | 0.341±0.05a | 3.260±0.05a | 1.010±0.08a | 470.295±17.44b | |

| C2 | 0.89±0.02a | 2.243±0.10b | 0.381±0.02b | 3.283±0.07a | 0.891±0.03a | 593.146±25.92c | |

| 83 | C0 | 1.31±0.02a | 1.770±0.02a | 0.360±0.01a | 2.714±0.18a | 0.944±0.03a | 234.006±14.42a |

| C1 | 1.29±0.02a | 1.916±0.02a | 0.436±0.03b | 3.124±0.21a | 0.798±0.02a | 352.406±15.41b | |

| C2 | 1.185±0.03b | 2.219±0.05b | 0.489±0.04b | 3.252±0.06a | 0.889±0.01a | 573.513±24.69c | |

| 98 | C0 | 1.63±0.01a | 1.775±0.1a | 0.442±0.01a | 2.239±0.06a | 0.782±0.02a | 223.420±12.003a |

| C1 | 1.615±0.01a | 1.982±0.06a | 0.501±0.03b | 2.479±0.1a | 0.798±0.07a | 321.057±15.506b | |

| C2 | 1.67±0.02b | 2.150±0.01a | 0.504±0.03b | 3.155±0.04b | 0.873±0.03a | 552.183±17.806c | |

| 130 | C0 | 2.215±0.06a | 2.025±0.03a | 0.605±0.01a | 1.413±0.16a | 0.470±0.05a | 213.833±13.875a |

| C1 | 2.425±0.02b | 2.154±0.04a | 0.545±0.03b | 2.114±0.14b | 0.669±0.06b | 258.995±15.194b | |

| C2 | 2.210±0.03a | 2.246±0.05a | 0.532±0.01b | 2.481±0.07b | 0.687±0.01b | 401.93±25.010c | |

| 165 | C0 | 3.110±0.01a | 2.483±0.04a | 0.702±0.01a | 0.923±0.06a | 0.354±0.04a | 207.446±10.054a |

| C1 | 3.290±0.01b | 2.221±0.03b | 0.557±0.01b | 1.542±0.04b | 0.500±0.01a | 215.203±9.338a | |

| C2 | 3.235±0.03b | 2.963±0.09c | 0.542±0.01b | 1.861±0.06b | 0.481±0.03a | 382.753±24.002b |

| Storage (days) | Olive oil samples | L | a* | b* |

| 0 | C0 | 21.81±0.043c | -0.843±0.015b | 13.503±0.047c |

| C1 | 18.37±0.036a | -0.842±0.018b | 11.393±0.072a | |

| C2 | 20.223±0.02b | -0.378±0.021a | 12.756±0.083b | |

| 21 | C0 | 20.247±0.05c | -0.833±0.015c | 12.71±0.026b |

| C1 | 18.310±0.017a | -0.743±0.05b | 10.176±0.1a | |

| C2 | 19.793±0.032b | -0.443±0.02a | 12.703±0.05b | |

| 35 | C0 | 18.417±0.308b | -0.89±0.026c | 11.66±0.049b |

| C1 | 18.330±0.01b | -0.74±0.04b | 10.436±0.04a | |

| C2 | 17.146±0.09a | -0.483±0.037a | 10.243±0.096a | |

| 56 | C0 | 17.42±0.073a | -0.96±0.01a | 10.81±0.04b |

| C1 | 17.646±0.065a | -0.746±0.030b | 9.726±0.032a | |

| C2 | 17.873±0.047a | -0.66±0.036c | 10.256±0.023b | |

| 83 | C0 | 16.556±0.037a | -0.996±0.077c | 9.870±0.098a |

| C1 | 16.113±0.156a | -0.849±0.031b | 9.700±0.01a | |

| C2 | 17.723±0.085b | -0.76±0.026a | 9.870±0.05a | |

| 98 | C0 | 14.286±0.031a | -1.253±0.049a | 8.543±0.04a |

| C1 | 15.653±0.23b | -1.063±0.015b | 9.2130.025b | |

| C2 | 15.986±0.058b | -0.85±0.045c | 9.193±0.051b | |

| 130 | C0 | 12.903±0.04a | -1.153±0.02a | 7.826±0.056a |

| C1 | 12.276±0.066a | -1.09±0.065a | 8.903±0.055b | |

| C2 | 12.166±0.065a | -0.93±0.016b | 8.866±0.071b | |

| 165 | C0 | 11.800±0.05a | -1.568±0.015c | 7.238±0.034a |

| C1 | 11.230±0.012a | -1.219±0.011b | 8.842±0.021b | |

| C2 | 11.010±0.013a | -1.02±0.026a | 8.012±0.011a |

| Variables | Levels | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <25 | 102 | 45.5 |

| 25-40 | 76 | 33.9 | |

| 40-60 | 44 | 19.6 | |

| >60 | 2 | 1 | |

| Gender | F | 122 | 54.5 |

| M | 102 | 45.5 | |

| Educational level | Bachelor’sdegree | 38 | 17 |

| High schooldiploma | 116 | 51.8 | |

| Lowersecondaryschoolcertificate | 18 | 8 | |

| Master’sdegree | 43 | 19.2 | |

| PhD or other | 9 | 4 |

| Question | Levels | % |

|---|---|---|

| How do you buy your olive oil? | Directly from the producer | 86.5 |

| From supermarket | 4 | |

| at the grocer’s | 3.6 | |

| on the market | 5.9 | |

| On average, how often do you use olive oil in your personal diet? | 3 time/week | 70.2 |

| 1 to 2 time/week | 15.4 | |

| 1 time/15 days | 8.7 | |

| little | 5.7 | |

| On average, what is your household’s monthly consumption of olive oil? | < ½ L/month | 7.8 |

| 1 L/month | 27.2 | |

| 2L/month | 23.3 | |

| >2L/month | 41.7 | |

| Use of olive oil | Salad dressing | 51.5 |

| Cooking | 45.6 | |

| Frying | 2.9 | |

| Do you know about flavoured oils for food uses? | Yes | 30 |

| No | 70 | |

| What would be your reservations about buying ready-to-use flavoured oils in supermarkets? | Lack of advice. | 22.3 |

| No specialized point of sale. | 15.5 | |

| Doubts about the quality of the product. | 46.6 | |

| The price higher than for an unflavored oil | 15.5 | |

| Do you know the health benefits of cloves? | yes | 52.7 |

| No | 47.3 | |

| If you find a clove flavored oil, would you be willing to buy it? | Yes | 83.9 |

| No | 14.3 | |

| Probably | 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).