1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had many unwanted effects on the lives of present-day individuals and organizations, including higher education [

1]. Medical education, with its unique functional demands, has experienced various disruptions: online teaching for basic medical sciences has become the norm; examinations have been performed through the internet; and clinical rotations have been cancelled [

2,

3]. Mental health and well-being were brought to the fore as prevalence of depression and anxiety increased [

4]. Medical schools were challenged with establishing curriculum frameworks, recruiting qualified faculty, and securing necessary resources [

5].

Many studies have examined adaptations in higher education in response to the pandemic, ranging from curriculum revisions and hybrid learning to mental health initiatives and faculty development [

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, there's a notable gap in the literature about newly established higher education institutions, including medical schools, that emerged in the shadow of the pandemic. This distinction is important because unlike established medical schools, new medical schools wouldn't just adapt but would likely embed pandemic-era values, technologies, and expectations into their very foundation. The pioneer cohort of faculty and students can thus provide a valuable case study for understanding the complexities of launching a medical education initiative in a post-pandemic context. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the motivations of faculty and students in embarking on this newly accredited medical program in the wake of the pandemic, as well as on the concerns that need to be addressed by the university at the beginning of this inaugural cohort’s journey. A learning environment that strives to nurture these motives and that provides opportunities for addressing the concerns of both faculty and students will assist in producing quality physicians. The baseline data can further inform future initiatives aimed at monitoring changes in motivation, addressing evolving concerns, and optimizing the educational experience throughout the students' medical training and the faculty's teaching careers. Moreover, the findings of this research are anticipated to provide valuable insights not only for the studied institution but also for other emerging medical education programs globally as they develop resilient and adaptable educational models in a rapidly evolving post-pandemic situation [

10].

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods cross-sectional survey design. The design allowed for collection of quantitative data on motivation and qualitative data on concerns, capturing the experiences of faculty and students. The cross-sectional nature of the study provides a snapshot of perspectives at a specific point in time, which is valuable for understanding the initial experiences of the participants within the specific context.

The study was conducted at a newly established medical school in the northern Philippines during its first academic year (i.e. 2023-2024). We initially aimed for total population sampling (a non-probability method) to include all participants. However, due to voluntary participation, the study included 17 faculty (of 22) and 15 first-year students (of 17).

Data were collected via validated questionnaires. Faculty motivations were measured via a Likert-based questionnaire adapted from the Physician Teaching Motivation Questionnaire (PTMQ) [

11]. This questionnaire evaluated the degree to which faculty engage in teaching activities for reasons such as enjoyment, a sense of competence, external rewards, or a lack of motivation. Student motivations were measured as adapted from the Likert-based Motivation to Do Medicine Scale (MMS), a questionnaire that can assess the desire for a stable and respected career, the desire to help and care for others, and the interest in scientific inquiry and advancement of medical knowledge [

12]. Both questionnaires included an open-ended section where the participants could articulate their specific concerns in their own words, providing valuable contextual information to supplement the quantitative data.

The participants were provided with detailed information about the study's objectives, methods, possible risks and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time. They were assured that their participation was voluntary and that their decision would not affect their academic or professional standing. The participants’ responses were kept confidential and anonymous, in accordance with the Philippine Data Privacy Act (RA 10173). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the university’s Ethics Review Board.

The quantitative data were analyzed via the statistical tools of Microsoft Excel®. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the faculty and student demographics and motivation scores. Exploratory subgroup analyses were conducted via independent samples t-tests to compare mean motivation scores between groups (e.g., males vs. females) and Spearman's rho correlation coefficients to examine potential linear relationships between continuous variables (e.g., age, years in teaching) and motivation scores. Statistical significance was set at a P-value < 0.05. The qualitative data were analyzed through a process of summarizing and synthesizing the main points with the aid of tagging software.

3. Results

The demographic data of the participants are shown in

Table 1. The faculty members had a mean age of 50.4 years (SD = 5.5), with a range of 42 - 62 years. The faculty composition was predominantly female (70%), with 30% being male. The majority held the position of Associate Professor (70%), whereas 30% were Professors. Their years of teaching experience varied, with an average of 5.5 years (SD = 4.6), and a range from 1 - 15 years. The students had a mean age of 25.3 years (SD = 2.7), with a range of 22 - 31 years. The gender distribution was 40% male and 60% female. Their undergraduate degrees represented a range of science disciplines, with the most common being laboratory science (40%) and biology (26.67%).

Faculty members demonstrated a strong inclination towards intrinsic motivation in their teaching roles (

Table 2). The average scores for intrinsic motivation items were consistently high: "I enjoy my teaching most of the time" (mean = 4.65), "During teaching, I am completely in my element" (mean = 4.59), and "I teach because it’s important for me to make my contribution to students becoming good physicians in the future" (mean = 4.88). In contrast, average scores for extrinsic motivation (e.g., mean = 2.06 for "I mainly teach because otherwise I would get into trouble with my supervisors") and amotivation (e.g., mean = 1.53 for "I teach although I often perceive it as an annoying chore"), were significantly lower. In contrast, student motivations revealed a multifaceted orientation, encompassing a combination of status and security, people-centered, and research-oriented drives (

Table 2). Students expressed moderate to high levels of motivation related to status and security (e.g., mean = 4.2 for "job security" and mean = 4.33 for "defined profession"). Simultaneously, the students demonstrated strong people motivation (e.g., mean = 4.47 for "social and humanitarian effort" and mean = 4.73 for "caring for people"). Furthermore, the students showed considerable interest in research (e.g., mean = 4.13 for "interest in human biology" and mean = 4.27 for "general interest in natural science").

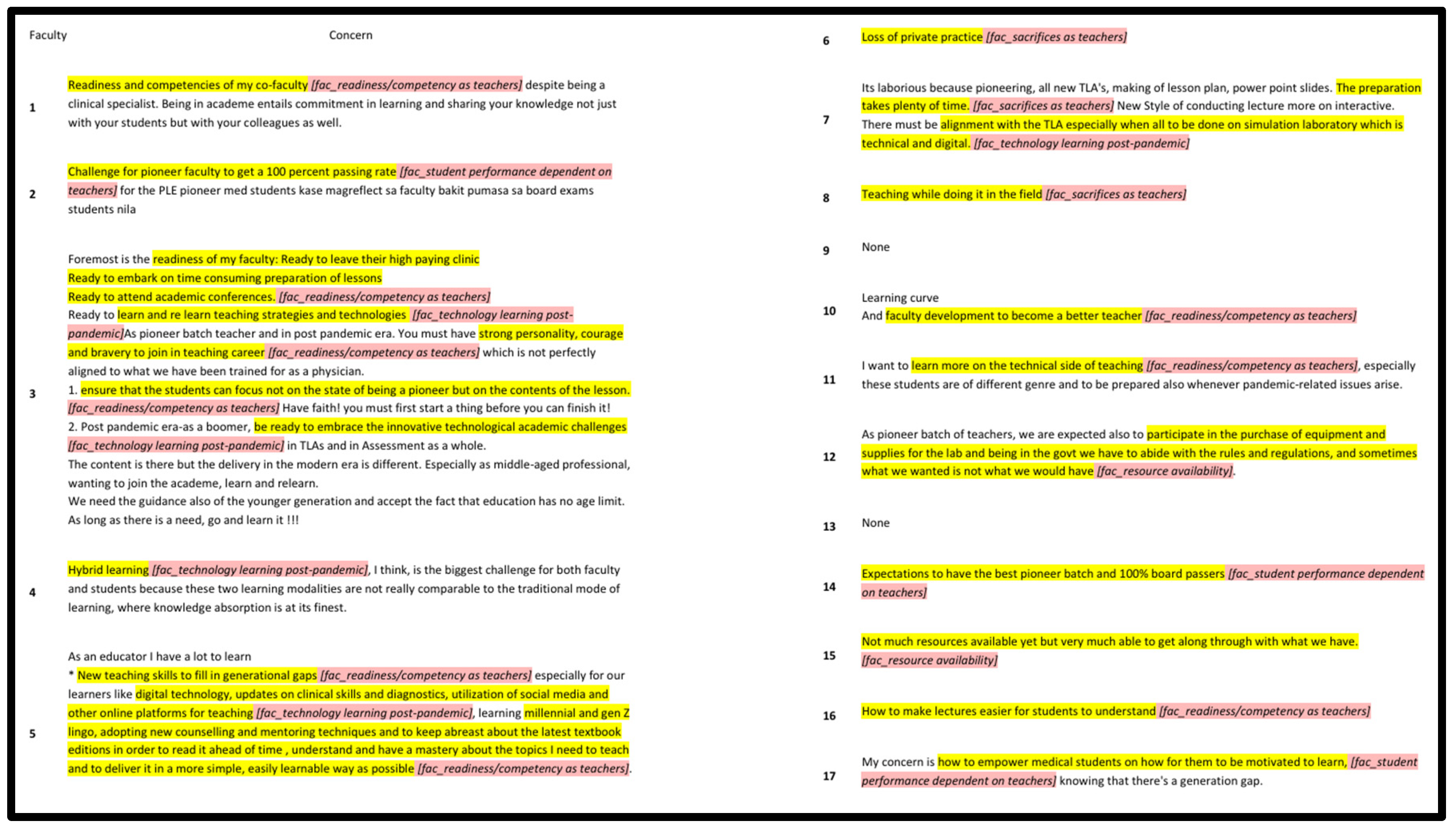

A summary of the concerns of each faculty member (

Figure 1) revealed that their concerns were related primarily to their preparedness for the academic role and the challenges of ensuring effective student learning in a new post-pandemic program. Specific concerns included their anxieties about their readiness and competence, such as adapting to new teaching approaches (n = 9):

“Foremost is the readiness of my faculty: ready to leave their high paying clinic, ready to embark on time consuming preparation of lessons, ready to attend academic conferences, ready to learn and re learn teaching strategies and technologies.”

Challenges related to student performance and expectations were also noted (n = 3):

“Challenge for pioneer faculty to get a 100 percent passing rate for the PLE pioneer med students.”

Faculty members recognized the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education, particularly the challenges of implementing hybrid learning models and utilizing modern teaching technologies and online learning platforms (n = 5):

“Hybrid learning, I think, is the biggest challenge for both faculty and students because these two learning modalities are not really comparable to the traditional mode of learning, where knowledge absorption is at its finest.”

Some faculty members also expressed concerns about the availability of adequate resources, such as teaching materials, laboratory equipment, and technological infrastructure, to support effective teaching and learning in the new medical program (n = 2):

“Not much resources available yet but very much able to get along through with what we have.”

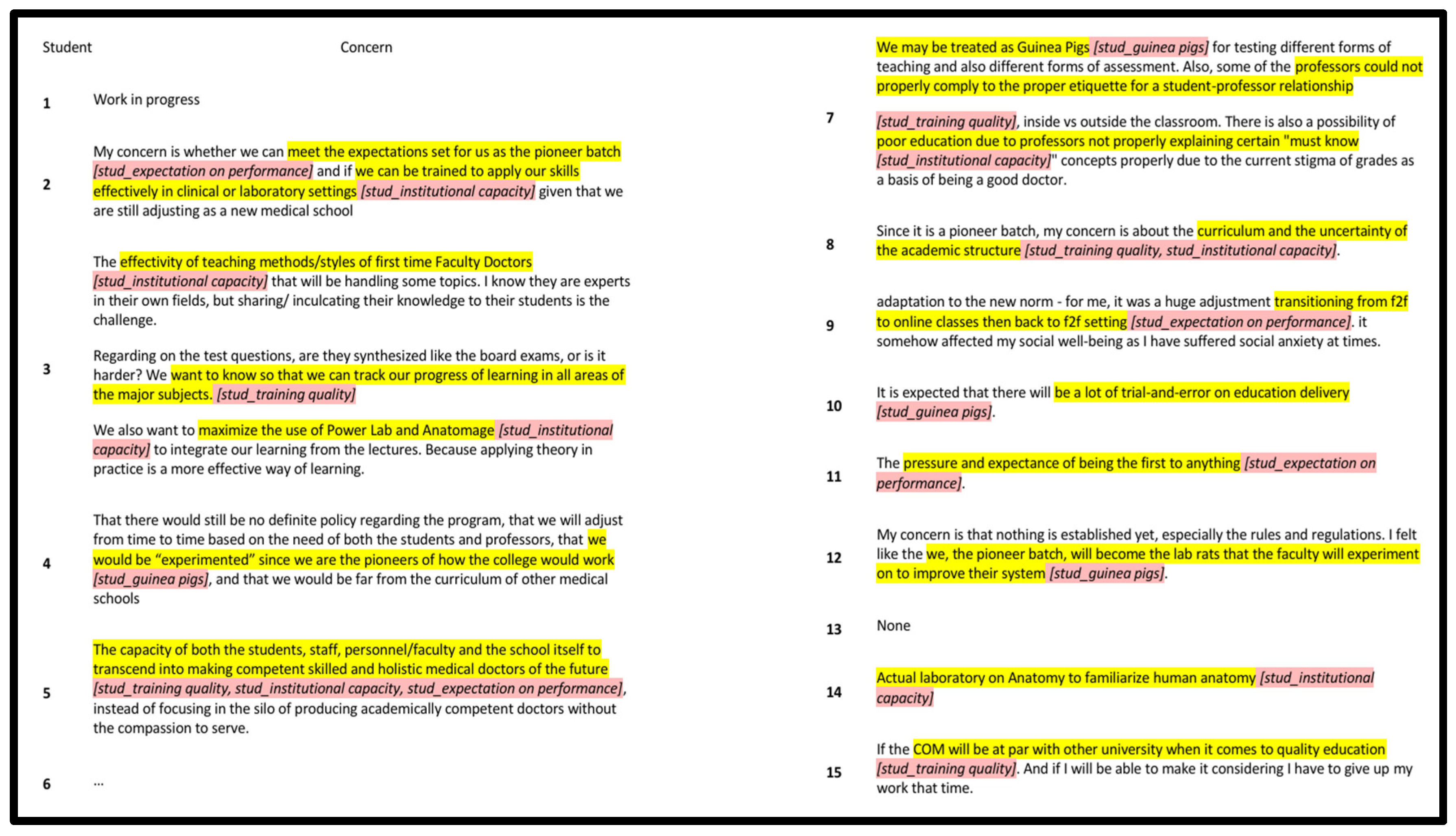

The synthesis of all the students’ concerns (

Figure 2) revealed that their concerns largely revolved around their anxieties about the training they would receive, institutional capacity in training them and their unique circumstances of being the pioneer batch. In particular, students raised questions about the institution's resources and infrastructure to support a medical program, including the adequacy of laboratory facilities, library resources, and the availability of qualified faculty (n = 12):

“The effectivity of teaching methods/styles of first time Faculty Doctors that will be handling some topics. I know they are experts in their own fields, but sharing/ inculcating their knowledge to their students is the challenge.”

Additionally, they acknowledged the unique pressures and challenges associated with being the first cohort in a new medical program, such as being considered guinea pigs, with respect to potential trial-and-error approaches and the need to adapt to evolving program expectations (n = 8):

“My concern is that nothing is established yet, especially the rules and regulations. I felt like the we, the pioneer batch, will become the lab rats that the faculty will experiment on to improve their system.”

Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential relationships between demographic variables and motivation scores (

Table 3). These analyses revealed no statistically significant correlations between faculty age or years in teaching and their motivation scores. Similarly, no significant differences were found between male and female faculty members in their intrinsic, extrinsic, or amotivation scores. Student age and sex were also not significantly related to motivational orientation.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the motivations and concerns of pioneer faculty and students in a newly established medical school during the post-pandemic period. The findings reveal that faculty members have greater intrinsic motivation than do students with more diverse drive styles. Concerns center on anxieties related to preparedness, resources, and the unique context of a new program in a transformed educational environment. By examining the differences in medical school landscapes in the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic eras, the results of this study can be effectively applied to the development of effective institutional strategies to support both faculty and students in this unique context.

The faculty's strong intrinsic motivation as seen in their enjoyment of teaching, feeling "in their element," and perceiving teaching as enriching, aligns with self-determination Theory (SDT), a theory that emphasizes intrinsic drives such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness as fundamental psychological needs driving behavior [

13]. The low scores in extrinsic motivation and amotivation further support that they are less likely to teach because of external pressures or a sense of obligation. These results point to a great advantage for the new school: pioneer faculty may face unique challenges, but their intrinsic motivation can translate to greater dedication, creativity, and resilience to face demands of post-pandemic realities [

14]. Faculty members also voiced their concerns about their readiness to teach in a pioneering program. This is consistent with Kegan’s theory of adult learning and professional development wherein faculty members transitioning into new academic roles, from their usual clinical endeavors, can experience a phase of uncertainty [

15]. Furthermore, in the technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) framework, the faculty’s concern with adapting to new teaching approaches and modern technologies is consistent with the need to integrate digital tools effectively into teaching practices [

16]. Concern about the availability of laboratory equipment, teaching materials, and technological infrastructure is related to the idea that an institution’s success relies on its capacity to provide necessary resources for effective performance, which is consistent with resource-based theory [

17].

The students exhibit a more varied motivational profile, encompassing elements of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: their considerable drive for curiosity and intellectual stimulation in research points toward intrinsic motivation; their emphasis on job security and a defined profession points toward extrinsic motivation; their strong people-centered orientation wherein altruism is awarded a conscious value, as it is personally important to the student (i.e., identified regulation), also points toward external motivation [

18]. These results are typical of students embarking on a demanding professional path such as medicine, where both personal fulfillment and career stability are important considerations [

19,

20]. Students' worries about training quality, resources, and faculty availability can be driven by their professional and people-centered motivations to provide quality care, ultimately influencing their confidence in their education. This aligns with research data on the importance of the learning environment and its impact on students' experiences, satisfaction, and success [

21]. Additionally, their notion of being guinea pigs in a newly established program aligns with Kotter’s change management model, which can explain why students in pioneering cohorts can experience uncertainty due to evolving curricula and institutional adjustments [

22].

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, medical education was characterized by in-person instruction and hands-on clinical training with technology serving as a supplementary tool [

23]. Intrinsic motivations for faculty and students involve dedication to patient care and intellectual curiosity [

24]. Come the pandemic, there was an abrupt shift in medical education, necessitating online learning models in the pre-clerkship and clerkship environments [

25]. Faculty had to adapt quickly to tools required for the new status quo, such as videoconferencing, social media and telemedicine [

26]. The pandemic also brought about increased workload and uncertainty, which led to increased stress and burnout among educators [

27]. For students, the loss of clinical exposure and hands-on training sparked concerns about competency upon graduation [

28]. In the post-pandemic era, medical schools are attempting to merge traditional teaching methods with the innovations necessitated by the pandemic [

29]. The faculty members in this study, who displayed strong intrinsic motivation, may have experienced commitment despite challenges. However, their concerns regarding preparedness, adapting to new technologies, and meeting student expectations, while seemingly counterintuitive to their high intrinsic motivation, may signal that they are still experiencing some discomfort or challenges in fully adapting to the changes brought about by the pandemic era. Additionally, faculty concerns about hybrid learning and resource availability suggest that, while digital education tools are now more accepted, their effective integration remains a challenge [

30]. Students’ concerns about institutional resources, faculty capability, and being the pioneer cohort in a new program highlight the distinct pressures associated with entering a newly established medical school. While not exclusively post-pandemic, they align with broader trends in medical education, where students increasingly emphasize the quality of their training and the adequacy of institutional support [

31].

Overall, the findings suggest that both faculty and students in this new medical school are navigating an already pandemic-shaped educational landscape. There’s a clear awareness among the faculty on what it means to teach in this post-pandemic context wherein medical education is shifting away from rigid, traditional models toward something more flexible, student-centered, and tech-integrated. At the same time, students aren’t entering a well-established system but are stepping into something that is still taking shape, where they can influence the norms and values that will ultimately prevail. From the beginning, the school didn’t try to copy or adjust to pre-pandemic structures; it started fresh, with flexibility, resilience, and openness to change built into its foundation. The shared experience of the pandemic may explain why faculty and students, despite their different demographic characteristics, manifest similar motivations and concerns. Viewed through the lens of Transformative Learning Theory, the pandemic served as a major turning point that led the participants to reflect deeply on what it means to become, or to train, a doctor today [

32]. These reflections seemed to have brought about common themes on how they understand and approach medical education now: worries about readiness, concerns about institutional capacity, and the challenge of adapting to new ways of teaching and learning.

The study's results also highlight critical challenges for faculty and students that demand immediate attention. Faculty members expressed concerns regarding their preparedness for the academic role, utilization of modern teaching technologies and challenges in ensuring effective student learning in a new program. These concerns, amplified by the rapid adoption of technology-enhanced learning, can be addressed through multifaceted faculty development programs [

33]. Programs can emphasize contemporary pedagogies, such as problem-based learning, team-based learning, or case-based learning. Additionally, with the increased reliance on digital tools, professional development should focus on the use of learning management systems (LMSs), online collaboration tools, and other educational technologies that support hybrid learning environments. This is crucial, as the post-pandemic landscape necessitates educators be proficient in leveraging technology to enhance pedagogical practices and student engagement [

34]. Students’ concerns, on the other hand, largely revolve about their anxieties on the training they will receive, institutional capacity in training them and their unique circumstances of being the pioneer batch. Building a culture of trust through open communication about available resources and a demonstrable commitment to ongoing investment and improvement is crucial for mitigating student anxieties and fostering a supportive learning environment [

35,

36].

The mixed-methods design provided a rich understanding of these issues by combining quantitative and qualitative data. The focus on pioneer faculty and students in a new post-pandemic institution offers a unique perspective in medical education. However, the study has several limitations. The small sample sizes of both faculty and students limit the statistical power and generalizability of the quantitative or qualitative findings and may not be fully transferable in other cultural or socioeconomic contexts. The reliance on self-reported data may also be subject to biases. Nevertheless, future research can build upon the study’s initial findings: longitudinal studies to track the changing motivations and concerns of both faculty and students; comparative studies with established medical schools to identify nuanced data for this school; and investigations of the effectiveness of the suggested solutions, such as specific hybrid learning models appropriate in the post-pandemic era, to share with other nascent schools.

5. Conclusions

In launching a medical school in the aftermath of a global pandemic, the main stakeholders are presented with a unique set of challenges and possibilities. This study, though based on a small pioneer cohort, offers valuable insights into how faculty are driven by purpose, yet face the pressures of adapting to evolving roles and technologies, and students stepping into a space where the rules are still being written, carry anxieties about the future. What unites them is a shared experience of the pandemic—an event that seems to have sparked reflection on what it means to teach and learn medicine today, with that reflection centered on readiness, institutional trust, and adaptability. These findings suggest that new medical schools have the opportunity not just to adjust to post-pandemic realities, but to fully embrace them by building educational models that are flexible, forward-thinking, and centered on the real experiences of those at their core.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft, investigation, and formal analysis, EB; methodology and writing—review and editing, GM.

Funding

This research was funded by Isabela State University Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Isabela State University (# 2024-03-002).

Informed Consent Statement

Each individual who took part in this study signed a consent form, confirming they were informed about the research before agreeing to participate.

Data Availability Statement

The authors opt to make the data available on acceptance of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the management, faculty and students of ISU and ISU-COM for their steadfast support of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Babbar, M., & Gupta, T. (2021). Response of educational institutions to COVID-19 pandemic: An inter-country comparison. Policy Futures in Education, 20(4), 469-491. [CrossRef]

- Karim, Z., Javed, A., & Azeem, M. W. (2022). The effects of Covid-19 on Medical Education. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 38(1), 320–322. [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M., Almusharraf, N., & Aldeghaither, D. (2021). Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in higher education: Evidence from G20 countries. Journal of public health research, 9(Suppl 1), 2010. [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Bueno-Notivol, J., Pérez-Moreno, M., & Santabárbara, J. (2021). Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Brain Sciences, 11(9), 1172. [CrossRef]

- Althwanay, A., Ahsan, F., Oliveri, F., Goud, H. K., Mehkari, Z., Mohammed, L., Javed, M., & Rutkofsky, I. H. (2020). Medical Education, Pre- and Post-Pandemic Era: A Review Article. Cureus, 12(10), e10775. [CrossRef]

- Bashir A, Bashir S, Rana K, Lambert P, Vernallis A. (2021). Post-COVID-19 Adaptations; the Shifts Towards Online Learning, Hybrid Course Delivery and the Implications for Biosciences Courses in the Higher Education Setting. Frontiers in Education 6 (1). [CrossRef]

- Singh, J., Steele, K., & Singh, L. (2021). Combining the Best of Online and Face-to-Face Learning: Hybrid and Blended Learning Approach for COVID-19, Post Vaccine, & Post-Pandemic World. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50(2), 140-171. [CrossRef]

- Gardanova, Z., Belaia, O., Zuevskaya, S., Turkadze, K., & Strielkowski, W. (2023). Lessons for Medical and Health Education Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare, 11(13), 1921. [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C. J., Barbieri, V., Plagg, B., Marino, P., Piccoliori, G., & Engl, A. (2023). Fortifying the Foundations: A Comprehensive Approach to Enhancing Mental Health Support in Educational Policies Amidst Crises. Healthcare, 11(10), 1423. [CrossRef]

- Samaraskera, Dujeepa. (2023). Emerging stronger post pandemic: Medical and Health Professional Education. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 8. 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Dybowski, C., & Harendza, S. (2015). Validation of the Physician Teaching Motivation Questionnaire (PTMQ). BMC medical education, 15, 166. [CrossRef]

- Pastor, María-Ángeles & López-Roig, Sofía & Sánchez, Salvador & Hart, Jo & Johnston, Marie & Dixon, Diane. (2009). Analysing motivation to do medicine cross-culturally: The International motivation to do medicine scale. Escritos de Psicología - Psychological Writings. 2. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. W. (2009). Intrinsic motivation at work: Building energy and commitment. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Harvard University Press.

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Deci E., Ryan R. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Yousefy, A., Ghassemi, G., & Firouznia, S. (2012). Motivation and academic achievement in medical students. Journal of education and health promotion, 1, 4. [CrossRef]

- Goel, S., Angeli, F., Dhirar, N., Singla, N., & Ruwaard, D. (2018). What motivates medical students to select medical studies: a systematic literature review. BMC medical education, 18(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Genn, J. M. (2001). AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 23: Curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education—a unifying perspective. Medical Teacher, 23(5), 445-454. [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Harvard Business Press.

- Harden, R. M., & Laidlaw, J. M. (2020). Essential skills for a medical teacher: An introduction to teaching and learning in medicine (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

- Kusurkar, R. A., Croiset, G., Mann, K. V., Custers, E., & Ten Cate, O. (2013). Have motivation theories guided the development and reform of medical education curricula? A review of the literature. Academic Medicine, 88(7), 1025–1031. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA, 323(21), 2131–2132. [CrossRef]

- Dedeilia, A., Sotiropoulos, M. G., Hanrahan, J. G., Janga, D., Dedeilias, P., & Sideris, M. (2020). Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: A systematic review. In Vivo, 34(3 Suppl), 1603–1611. [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Legorburu Fernnadez, I., Lipnicki, D. M., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., & Santabárbara, J. (2023). Prevalence of Burnout among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(6), 4866. [CrossRef]

- Harries, A. J., Lee, C., Jones, L., Rodriguez, R. M., Davis, J. A., Boysen-Osborn, M., Kashima, K. J., Krane, N. K., Rae, G., Kman, N., Langsfeld, J. M., & Juarez, M. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: a multicenter quantitative study. BMC medical education, 21(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Garba SA, Abdulhamid L. (2024). Students’ Instructional Delivery Approach Preference for Sustainable Learning Amidst the Emergence of Hybrid Teaching Post-Pandemic. Sustainability; 16(17):7754. [CrossRef]

- Alenezi M, Wardat S, Akour M. (2023). The Need of Integrating Digital Education in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability. 15(6):4782. [CrossRef]

- Jalili, M., Mirzazadeh, A., & Azarpira, A. (2008). A Survey of Medical Students' Perceptions of the Quality of their Medical Education upon Graduation. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, 37(12), 1012-8.

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1997(74), 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Dysart, Sarah & Weckerle, Carl. (2015). Professional Development in Higher Education: A Model for Meaningful Technology Integration. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, 14. 255-265. [CrossRef]

- Sato, S. N., Condes Moreno, E., Rubio-Zarapuz, A., Dalamitros, A. A., Yañez-Sepulveda, R., Tornero-Aguilera, J. F., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2024). Navigating the New Normal: Adapting Online and Distance Learning in the Post-Pandemic Era. Education Sciences, 14(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445. [CrossRef]

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).