Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Survey of Relevant Literature

3. The Evolution of Wildlife Hazard Management

4. Challenges Associated with Wildlife Strike Reporting

4.1. More than Just Wildlife Strikes

4.2. Potential Tunnel Vision on Success

4.3. Impact on Wildlife Risk Assessment

5. The Use of Wildlife Strike Data in Research

6. International/National Standards & Guidance

- An accident is an event involving the operation of an aircraft that results in the death or serious injury of a person, the aircraft sustains significant damage or the aircraft is missing. However, this definition excludes specific types of damage resulting from a bird strike.

- A serious incident is a situation that had a high probability of being an accident.

- An incident is any other type of occurrence that affects or could affect safety.

- someone witnesses a collision between wildlife and an aircraft;

- there is evidence on an aircraft, including damage, of a collision with wildlife;

- the remains of wildlife are found either on or near a runway, on a taxiway or anywhere else near an aerodrome where there is no other explanation for the animal’s death, or a collision is suspected; or

- wildlife on or near an aerodrome have had a “significant negative effect on a flight” [121] (p. 3).

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAWHG | Australian Aviation Wildlife Hazard Group |

| ADOP | Aerodrome Design and Operations Panel |

| ANC | Air Navigation Commission |

| ATC | Air Traffic Control |

| ATSB | Australian Transport Safety Bureau |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| IBIS | ICAO Bird Strike Information System |

| IBSC | International Bird Strike Committee |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organisation |

| IFATCA | International Federation of Air Traffic Controllers’ Associations |

| NAA | National Aviation Authority |

| OLS | Obstacle Limitation Surface |

| RHS | Relative Hazard Score |

| USDA-WS | US Department of Agriculture – Wildlife Services |

| WBA | World Birdstrike Association |

| WHMP | Wildlife Hazard Management Plan |

References

- Lofquist, E.A. The art of measuring nothing: The paradox of measuring safety in a changing civil aviation industry using traditional safety metrics. Safety Science 2010, 48, 1520–1529. [CrossRef]

- Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Australian aviation wildlife strike statistics 2008 – 2017 [Data set]. Australian Transport Safety Bureau: Canberra, Australia, 2019. https://www.atsb.gov.au/publications/2018/ar-2018-035.

- Australian Transport Safety Bureau. ATSB national aviation occurrence database: Detailed data search. Available online: http://data.atsb.gov.au/DetailedData (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Dolbeer, R.A.; Begier, M.J.; Miller, P.R.; Weller, J.R.; Anderson, A.L. Wildlife strikes to civil aircraft in the United States 1990-2023; Federal Aviation Administration: Washington DC, United States, 2022. https://www.faa.gov/airports/airport_safety/wildlife/wildlife-strike-report-1990-2023-USDA-FAA.

- Civil Aeronautics Board. Aircraft accident report: Eastern air lines, inc., Lockheed Electra L-188, N 5533, Logan International Airport, Boston, Massachusetts, October 4, 1960, 1962. https://www.faa.gov/lessons_learned/transport_airplane/accidents/N5533.

- Allan, J.R. The costs of bird strikes and bird strike prevention. Human Conflicts with Wildlife: Economic Considerations 2000, 18. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrchumanconflicts/18.

- Allan, J.R.; Orosz, A.P. The costs of birdstrikes to commercial aviation. In 2001 Bird Strike Committee-USA/Canada, Third Joint Annual Meeting, Calgary, Canada, August 2001; pp. 218–226. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=birdstrike2001.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Annex 14 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation: Aerodromes, Volume I (9th ed.). International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 2022. https://portal.icao.int/icao-net/Annexes/an14_v1_cons.pdf.

- Title 14, Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] 2004 [US]. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14.

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Part 139 (aerodromes) manual of standards 2019, Civil Aviation Safety Authority: Canberra, Australia, 2019. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2020C00797.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Easy access rules for aerodromes (Regulation (EU) no 139/2014), 3rd ed.; European Union, 2020. https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/Easy%20Access%20Rules%20for%20Aerodromes%20%28Revision%20from%20November%202020%29.pdf.

- Allan, J.; Baxter, A.; Callaby, R. The impact of variation in reporting practices on the validity of recommended birdstrike risk assessment processes for aerodromes. Journal of Air Transport Management 2016, 57, 101–106. https://canadianbirdstrike.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Allan_et_al_2016.pdf.

- Metz, I.C.; Ellerbroek, J.; Mühlhausen, T.; Kügler, D.; & Hoekstra, J.M. The bird strike challenge. Aerospace 2020, 7, 26. https://www.mdpi.com/2226-4310/7/3/26/pdf.

- Eekeren, R. van. Wildlife strike definition. In Proceedings of the World Birdstrike Association 2021 Conference, virtual (13–14 January 2021). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/wba-conferences/66-wba-conferences/167-wba-1st-virtual-conference-2021.

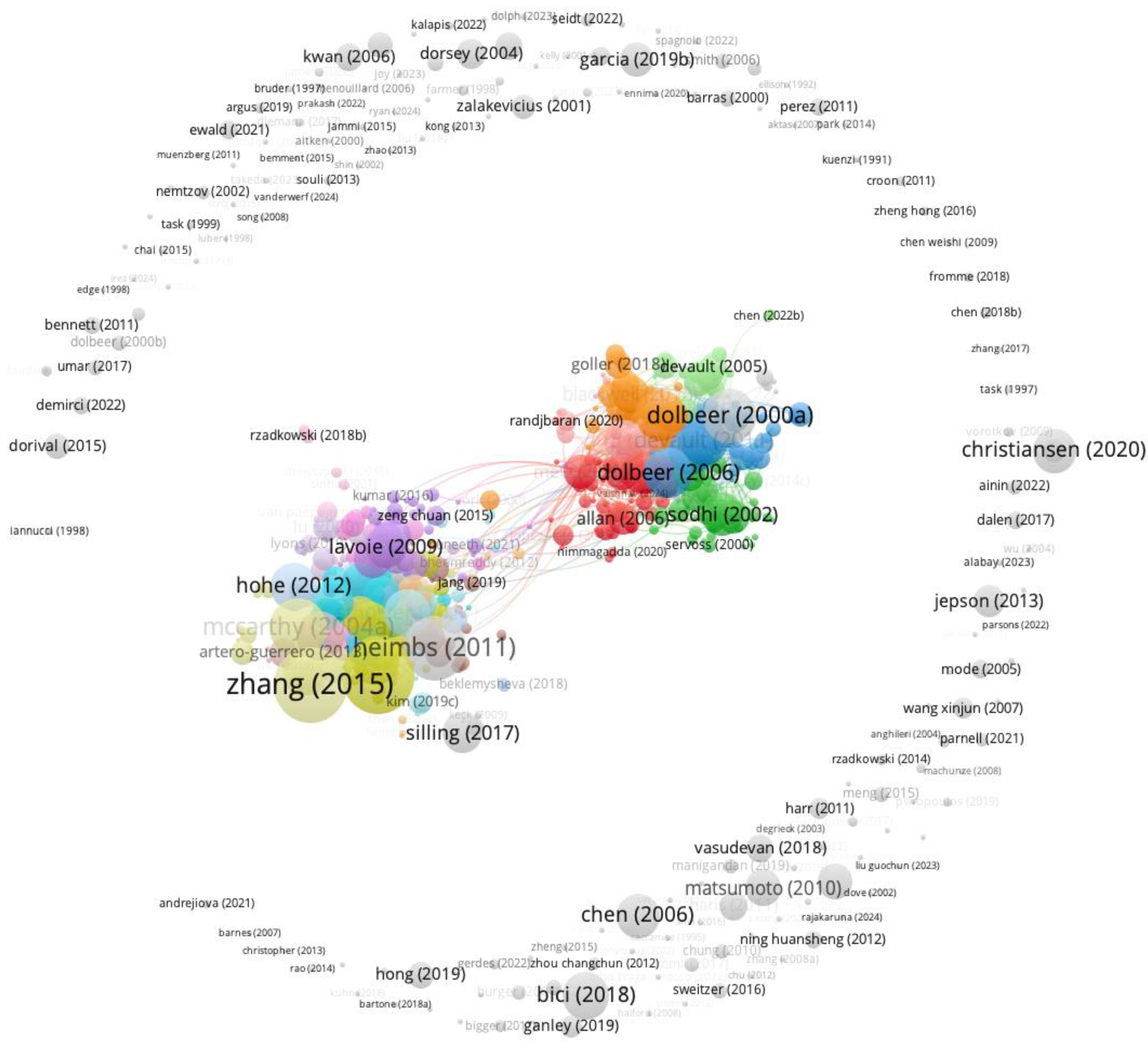

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. https://akjournals.com/downloadpdf/view/journals/11192/84/2/article-p523.pdf.

- Christiansen, F.; Dawson, S.M.; Durban, J.W.; Fearnbach, H;. and others. Population comparison of right whale body condition reveals poor state of the North Atlantic right whale. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2020, 640, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Jepson, P.D.; Deaville, R.; Acevedo-Whitehouse, K.; Barnett, J.; Brownlow, A.; Brownell Jr., R.L.; and others. What Caused the UK's Largest Common Dolphin (Delphinus delphis) Mass Stranding Event? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60953. [CrossRef]

- Bici, M.; Brischetto, S.; Campana, F.; Ferro, C.G.; Seclì, C.; Varetti, S.; Maggiore, P.; Mazza, A. Development of a multifunctional panel for aerospace use through SLM additive manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2018, 67, 215–220. [CrossRef]

- Parnell, K.J.; Wynne, R.A.; Griffin, T.G C.; Plant, K.L.; Stanton, N.A. Generating Design Requirements for Flight Deck Applications: Applying the Perceptual Cycle Model to Engine Failures on Take-off. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2021, 37, 611–629. [CrossRef]

- Caccamise, D.F.; Reed, L.M.; Dosch, J.J.; Bennett, K. Management of bird strike hazards at airports: A habitat approach. In Proceedings of the 82nd Annual Meeting of the New Jersey Mosquito Control Association, Inc., Atlantic City, NJ, (01 January 1995). https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000076630200008.

- Caccamise, D.F.; Dosch, J.J.; Benett, K.; Reed, L.M.; DeLay, L. Management of bird strike hazards at airports: a habitat approach. Proceedings of the International Bird Strike Committee Meeting, Vienna, Austria, (29 August – 02 September 1994).

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11192-017-2300-7.pdf.

- Meo, M.; Morris, A.J.; Vignjevic, R.; Marengo, G. Numerical simulations of low-velocity impact on an aircraft sandwich panel. Composite Structures 2003, 62, 353–360. [CrossRef]

- Guida, M.; Marulo, F.; Meo, M.; Riccio, M. Analysis of bird impact on a composite tailplane leading edge. Applied Composite Materials 2008, 15, 241–257. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10443-008-9070-6.

- Guida, M.; Marulo, F.; Meo, M.; Grimaldi, A.; Olivares, G. SPH–Lagrangian study of bird impact on leading edge wing. Composite Structures 2011, 93, 1060–1071. [CrossRef]

- Vignjevic, R.; Orłowski, M.; De Vuyst, T.; Campbell, J.C. A parametric study of bird strike on engine blades. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2013, 60, 44–57. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Fei, Q. Effect of bird geometry and impact orientation in bird striking on a rotary jet-engine fan analysis using SPH method. Aerospace Science and Technology 2016, 54, 320–329. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, D. Effect of arbitrary yaw/pitch angle in bird strike numerical simulation using SPH method. Aerospace Science and Technology 2018, 81, 284–293. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W. Finite element simulation of PMMA aircraft windshield against bird strike by using a rate and temperature dependent nonlinear viscoelastic constitutive model. Composite Structures 2014, 108, 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Mohagheghian, I.; Charalambides, M.N.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Kinloch, A.J.; Dear, J.P. Effect of the polymer interlayer on the high-velocity soft impact response of laminated glass plates. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2018, 120, 150–170. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huang, T. Bird-Strike Resistance of Composite Laminates with Different Materials. Materials 2020, 13, 129. [CrossRef]

- Zakrajsek, E.J.; Bissonette, J.A. Ranking the risk of wildlife species hazardous to military aircraft. Wildlife Society Bulletin 2005, 33, 258–264. https://www.proquest.com/docview/230200803.

- Allan, J. A heuristic risk assessment technique for birdstrike management at airports. Risk Analysis 2006, 26, 723–729. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00776.x.

- DeVault, T.L.; Belant, J.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T. W. Interspecific variation in wildlife hazards to aircraft: Implications for airport wildlife management. Wildlife Society Bulletin 2011, 35, 394–402. [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, B.F.; DeVault, T.L.; Seamans, T.W.; Lima, S.L.; Baumhardt, P.; Fernández-Juricic, E. Exploiting avian vision with aircraft lighting to reduce bird strikes. Journal of Applied Ecology 2012, 49, 758–766. https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02165.x.

- Lima, S.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; DeVault, T.L.; Fernández-Juricic, E. Animal reactions to oncoming vehicles: a conceptual review. Biological Reviews 2015, 90, 60–76. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/brv.12093.

- Dolbeer, R.A. Height distribution of birds recorded by collisions with civil aircraft. The Journal of Wildlife Management 2006, 70, 1345–1350. https://www.proquest.com/docview/234183927.

- Blackwell, B.F.; DeVault, T.L.; Fernández-Juricic, E.; Dolbeer, R.A. Wildlife collisions with aircraft: a missing component of land-use planning for airports. Landscape and Urban Planning 2009, 93, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- van Gasteren, H.; Krijgsveld, K.L.; Klauke, N.; Leshem, Y.; Metz, I.C.; Skakuj, M.; Sorbi, S.; Schekler, I.; Shamoun-Baranes, J. Aeroecology meets aviation safety: early warning systems in Europe and the Middle East prevent collisions between birds and aircraft. Ecography 2019, 42, 899–911. https://nsojournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/ecog.04125.

- Marra, P.P.; Dove, C.J.; Dolbeer, R.; Dahlan, N.F.; Heacker, M.; Whatton, J.F.; Diggs, N.E.; France, C.; Henkes, G.A. Migratory Canada geese cause crash of US Airways Flight 1549. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2009, 7, 297–301. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1890/090066.

- Altringer, L.; Navin, J.; Begier, M.J.; Shwiff, S.A.; Anderson, A. Estimating wildlife strike costs at US airports: A machine learning approach. Transportation research part D: transport and environment 2021, 97, 102907. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.; Ryan, J.; Malouf, M.; Martin, W. Estimating the Cost of Wildlife Strikes in Australian Aviation Using Random Forest Modeling. Aerospace 2023, 10, p. 648. [CrossRef]

- Eschenfelder, P. Successful Strategies for Aviation Wildlife Mitigation. In Proceedings of the 11th Joint meeting of Bird Strike Committee USA & Canada, Victoria BC, Canada, (14–17 September 2009). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/birdstrike2009/5.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Airport Services Manual – Part 3 – Wildlife Hazard Management, 5th ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 2020. https://www.bazl.admin.ch/dam/bazl/en/dokumente/Fachleute/Flugplaetze/ICAO/icao_doc_9137_airportsevicesmanual-part3.pdf.download.pdf/icao_doc_9137_airportsevicesmanual-part3.pdf.

- Scheer, D.; Benighaus, C.; Benighaus, L.; Renn, O.; Gold, S.; Röder, B.; Böl, G. The distinction between risk and hazard: understanding and use in stakeholder communication. Risk Analysis 2014, 34, 1270–1285. https://www.academia.edu/download/39716097/The_Distinction_Between_Risk_and_Hazard_20151105-8133-7ftuqa.pdf.

- Allan, J.R. The use of risk assessment in airport bird control. In the Proceedings of the Bird-Strike Committee annual meeting, (August 2001). https://canadianbirdstrike.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Allan_2001.pdf.

- Dolbeer, R.A.; Wright, S.E.; Cleary, E.C. Ranking the hazard level of wildlife species to aviation. Wildlife Society Bulletin 2000, 28, 372–378. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P. A model for assessing bird strike risk at airports, 2006. Unpublished manuscript.

- Paton, D.C. Bird risk assessment model for airports and aerodromes, 3rd ed.; University of Adelaide, Adelaide, 2010. https://canadianbirdstrike.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Paton_2010.pdf.

- Pfeiffer, M.B.; Blackwell, B.F.; DeVault, T.L. Quantification of avian hazards to military aircraft and implications for wildlife management. PloS ONE 2018, 13, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- DeVault, T.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T.W.; Begier, M.J.; Kougher, J.D.; Washburn, J.E.; Miller, P.R.; Dolbeer, R.A. Estimating interspecific economic risk of bird strikes with aircraft. Wildlife Society Bulletin 2018, 42, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Standards Australia. Risk management: AS/NZS 4360:2004. Standards Australia International Ltd, Sydney, 2004.

- House, A.P.N.; Ring, J.G.; Hill, M.J.; Shaw, P.P. Insects and aviation safety: The case of the keyhole wasp Pachodynerus nasidens (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in Australia. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2020, 4, 1–11. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590198220300075.

- Bridgman, C.J. Birds nesting in aircraft. British Birds 1962, 55, 461–470. https://britishbirds.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/article_files/V55/V55_N11/V55_N11_P461_470_A062.pdf.

- Solman, V.E.F.; Thurlow, W.J. Reduction of wildlife hazards to aircraft. In the Proceeding of the 18th Meeting of the Bird Strike Committee Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark, (26–30 May 1986). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA368046.pdf.

- Marcus, L. AirAsia flight in Malaysia rerouted after snake found on board plane. CNN. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/airasia-malaysia-snake-plane-rerouted-intl-hnk/index.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ntampakis, D.; Biermann, T. Applying SMS and sustainability principles to airport wildlife hazard management. Revista Conexão SIPAER 2014, 5, 8–21. http://conexaosipaer.cenipa.gov.br/index.php/sipaer/article/view/255/278.

- McKee, J.; Shaw, P.; Dekker, A.; Patrick, K. Approaches to wildlife management in aviation. In Problematic wildlife. A cross-disciplinary approach; Angelici, F.M., Ed.; Springer: Switzerland, 2016; pp. 465–488. [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A.; Kelly, T.F.; Sowden, R.J.; Lang, A. L. Bird use, bird hazard risk assessment, and design of appropriate bird hazard zoning criteria design of appropriate bird hazard zoning criteria for lands surrounding the Pickering airport site. Transport Canada: Ontario, Canada, 2002. https://ininet.org/bird-use-bird-hazard-risk-assessment-and.html.

- Marateo, G.; Grilli, P.; Bouzas, N.; Ferretti, V.; Juarez, M.; Soave, G.E. Habitat use by birds in airports: A case study and its implications for bird management in South American airports. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2015, 13, 799–808. http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/10915/86192/Documento_completo.pdf?sequence=1.

- Iglay, R.B.; Buckingham, B.N.; Seamans, T.W.; Martin, J.A.; Blackwell, B.F.; Belant, J.L.; DeVault, T.L. Bird use of grain fields and implications for habitat management at airports. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2017, 242, 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Duo, L. Effects of vegetation management on the composition and diversity of the insect community at Tianjin Binhai International Airport, China. Bulletin of Entomological Research 2021, 111, 553-559. [CrossRef]

- Servoss, W.; Engeman, R.M.; Fairaizl, S.; Cummings, J.L.; Groninger, N.P. Wildlife hazard assessment for Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2000, 45, 111–127. [CrossRef]

- Hesse, G.; Rea, R.V.; Booth, A.L. Wildlife management practices at western Canadian airports. Journal of Air Transport Management 2010, 16, 185–190. https://web.unbc.ca/~reavweb/pdfs/rea_2010_wildlife_management_canadian_airports.pdf.

- Arshad, S.; Malik, A.M. Bird species richness, evenness and habitat management around airports: a case study of Benazir Bhutto International Airport Islamabad, Pakistan. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2020, 8, 413–421. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.S.; Ning, H.S.; Li, J. Flying Bird Detection and Hazard Assessment for Avian Radar System. Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2012, 25, 246–255. http://www.cybermatics.org/lab/paper_pdf/2011/Flying%20bird%20detection%20and%20hazard%20assessment%20for%20avian%20radar%20system.pdf.

- Ning, H.S.; Hu, S.; He, W.; Xu, Q.Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.S. nID-based Internet of Things and Its Application in Airport Aviation Risk Management. Chinese Journal of Electronics 2012, 21, 209–214. http://www.cybermatics.org/lab/paper_pdf/2012/nID-based%20Internet%20of%20Things%20and%20Its%20Application%20in%20Airport%20Aviation%20Risk%20Management.pdf.

- Muller, B.M.; Mosher, F.R.; Herbster, C.G.; Brickhouse, A.T. Aviation Bird Hazard in NEXRAD Dual Polarization Weather Radar Confirmed by Visual Observations. International Journal of Aviation Aeronautics and Aerospace 2015, 2. [CrossRef]

- Rochard, J.B.A. The UK civil aviation authority’s approach to bird hazard risk assessment. In the Proceedings of the 25th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Amsterdam, Netherlands, (12–21 April 2000). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Amsterdam/IBSC25_WPSA4.pdf.

- MacKinnon, B. Sharing the skies. An aviation industry guide to the management of wildlife hazards, 2nd ed.; Transport Canada: Ontario, Canada, 2004. https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/migrated/tp13549e.pdf.

- Cleary, E.C.; Dolbeer, R.A. Wildlife hazard management at airports: A manual for airport personnel, 2nd ed.; Federal Aviation Administration, Washington DC, United States, 2005. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1127&context=icwdm_usdanwrc.

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority. AC 139-26(0) – Wildlife Hazard Management at Aerodromes. Civil Aviation Safety Authority: Canberra, Australia, 2011. https://www.casa.gov.au/file/152501/download?token=sup4rVxS.

- Federal Aviation Administration. Advisory circular 150/5200-38 – protocol for the conduct and review of wildlife hazard site visits, wildlife hazard assessments, and wildlife hazard management plans. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington DC, United States, 2018. https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/150-5200-38.pdf.

- Dekker, A.; Buurma, L. Mandatory reporting of bird strikes in Europe. In the Proceedings of the 27th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Athens, Greece, (23–27 May 2005). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Athens/IBSC27_WPII-1.pdf.

- Mendonca, F.A.C. SMS for bird hazard: Assessing airlines pilots’ perceptions (Order No. 1458347), Master’s thesis, University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg, 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Flavio-Mendonca/publication/279931558_SMS_for_bird_hazard_assessing_airlines'_pilots'_perceptions/links/5e18d4eea6fdcc2837688eba/SMS-for-bird-hazard-assessing-airlines-pilots-perceptions.pdf.

- International Birdstrike Committee. Recommended practices no. 1 – standards for aerodrome bird/wildlife control, Issue 1, 2006. https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Documents/BestPractices/Standards_for_Aerodrome_bird_wildlife_control.pdf.

- Reason, J. Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Routledge, London, United Kingdom, 2016. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315543543/.

- Lupoli, L.C. Discovering the Brazilian Air Force squadron commanders’ perceptions regarding organisational accidents, Master’s thesis, University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg, 2006. https://search.proquest.com/openview/669df2ecd6c94f31493f2597f8409d33/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Schwarzenbach, T. (1978, May 29 – June 2). The bird strike reporting system in Swissair. In the Proceedings of the 13th Meeting of the Bird Strike Committee Europe, Berne, Germany, (29 May – 2 June 1978). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Bern/IBSC13_WP6.pdf.

- Klope, M.W.; Beason, R.C.; Nohara, T.J.; Begier, M.J. Role of near-miss bird strikes in assessing hazards. Human-Wildlife Conflicts 2009, 3, 208–215. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1269&context=hwi.

- Dolbeer, R.A.; Begier, M.J.; Miller, P.R.; Weller, J.R.; Anderson, A.L. Wildlife strikes to civil aircraft in the United States 1990-2020. Federal Aviation Administration, Washington DC, United States, 2021. https://www.faa.gov/airports/airport_safety/wildlife/media/Wildlife-Strike-Report-1990-2020.pdf.

- Smallie, J.; Froneman, A. Bird strike data analysis at South African airports and spatial representation of bird patrols in relation to bird strike occurrences. In the Proceeding of the 27th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Athens, Greece, (23–27 May 2005). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Athens/IBSC27_WPV-4.pdf.

- Metz, I.C. Air Traffic Control Advisory System for the Prevention of Bird Strikes, Doctoral thesis, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, 2021. https://research.tudelft.nl/files/90772572/20210519_Dissertation_ICMetz_Final.pdf.

- Metz, I.C.; Ellerbroek, J.; Mühlhausen, T.; Kügler, D.; Kern, S.; Hoekstra, J.M. The Efficacy of Operational Bird Strike Prevention. Aerospace 2021, 8, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J. Conflict of wings: birds versus aircraft. In Problematic wildlife. A cross-disciplinary approach; Angelici, F.M., Ed.; Springer: Switzerland, 2016, 443–463. [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J. 100 years of fatalities and destroyed civil aircraft due to bird strikes. In the Proceedings of the 30th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Stavanger, Norway, (25–29 June 2012).

- Thorpe, J. Fatalities and destroyed civil aircraft due to bird strikes, 2002 to 2004. In the Proceedings of the 27th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Athens, Greece, (23–27 May 2005). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Athens/IBSC27_WPII-3.pdf.

- Thorpe, J. Fatalities and destroyed civil aircraft due to bird strikes, 1912 – 2002. In the Proceedings of the 26th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Warsaw, Poland, (5–9 May 2003). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Warsaw/IBSC26_WPSA1.pdf.

- Shaw, P.; Dolbeer, R. Avisure - about us: incident database. Available online: https://avisure.com/wp/incident-database/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Richardson, W.J. Serious birdstrike-related accidents to military aircraft of ten countries: Preliminary analysis of circumstances. In the Proceedings of the 22nd Meeting of the Bird Strike Committee Europe, Vienna, Austria, (29 August – 2 September 1994). http://www.lgl.com/images/pdf/Richardson_1994_BSCE-Vienna.pdf.

- Richardson, W. J. Serious birdstrike-related accidents to military aircraft of Europe and Israel: List and analysis of circumstances. In the Proceedings of the 23rd Meeting of the Bird Strike Committee Europe, London, United Kingdom, (13–17 May 1996). http://www.lgl.com/images/pdf/Richardson_1996_BSCE-London.pdf.

- Richardson, W.J.; West, T. Serious birdstrike accidents to military aircraft: updated list and summary. In the Proceedings of the 25th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Amsterdam, Netherlands, (17–21 April 2000). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Amsterdam/IBSC25_WPSA1.pdf.

- Viljoen, I.M.; Bouwman, H. Conflicting traffic: characterization of the hazards of birds flying across an airport runway. African Journal of Ecology 2016, 54, 308–316. [CrossRef]

- Dolbeer, R.A. The history of wildlife strikes and management at airports. In Wildlife in airport environments: Preventing animal-aircraft collisions through science-based management; DeVault, T.L, Blackwell, B.f., Belant, J.L., Eds.; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, United States, 2013, 1–6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2657&context=icwdm_usdanwrc.

- Tatlier, M.S.; Baran, T. Structural and CFD analysis of an airfoil subjected to bird strike. European Journal of Mechanics B-Fluids 2020, 84, 478–486. [CrossRef]

- Swaddle, J.P.; Moseley, D.L.; Hinders, M.K.; Smith, E.P. A sonic net excludes birds from an airfield: implications for reducing bird strike and crop losses. Ecological Applications 2016, 26, 339–345. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, R.F.; Buschke, F.T. Urbanization around an airfield alters bird community composition, but not the hazard of bird-aircraft collision. Environmental Conservation 2019, 46, 124–131. [CrossRef]

- History.com Editors. Pilot Sully Sullenberger performs “miracle on the Hudson.” Available online: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/sully-sullenberger-performs-miracle-on-the-hudson (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Martin, J.A.; Belant, J.L.; DeVault, T.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Burger, L.W.J.; Riffell, S.K.; Wang, G. Wildlife risk to aviation: A multi-scale issue requires a multi-scale solution. Human-Wildlife Interactions 2011, 5, 198–203. [CrossRef]

- National Transportation Safety Board. Aircraft accident report – loss of thrust in both engines after encountering a flock of birds and subsequent ditching on the Hudson River US Airways flight 1549 Airbus A320-214, N106US Weehawken, New Jersey January 15, 2009 (NTSB/AAR-10/03 PB2010-910403). Available online: https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Pages/AAR1003.aspx (accessed 14 November 2024).

- Blackwell, B.F.; Schafer, L.M.; Helon, D.A.; Linnell, M.A. Bird use of stormwater-management ponds: Decreasing avian attractants on airports. Landscape and Urban Planning 2008, 86, 162–170. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1797&context=icwdm_usdanwrc.

- DeVault, T.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T.W.; Belant, J.L. Identification of off airport interspecific avian hazards to aircraft. Journal of Wildlife Management 2016, 80, 746–752. [CrossRef]

- Soldatini, C.; Albores-Barajas, Y.V.; Lovato, T.; Andreon, A.; Torricelli, P.; Montemaggiori, A.; Corsa, C.; Georgalas, V. Wildlife strike risk assessment in several Italian airports: lessons from BRI and a new methodology implementation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Dolbeer, R. Percentage of wildlife strikes reported and species identified under a voluntary reporting system. In the Proceedings of the 2005 Bird Strike Committee-USA/Canada 7th Annual Meeting, Vancouver, Canada, (14–18 August 2005). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=birdstrike2005.

- Dolbeer, R. Trends in reporting of wildlife strikes with civil aircraft and in identification of species struck under a primarily voluntary reporting system, 1990-2013. Other Publications in Zoonotics and Wildlife Disease 2015, 1–15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1190&context=zoonoticspub.

- Allan, J.R. The costs of bird strikes and bird strike prevention. Human Conflicts with Wildlife: Economic Considerations 2000, 18, 147–153. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrchumanconflicts/18/.

- Allan, J.R.; Orosz, A.; Badham, A.; Bell, J. The development of birdstrike risk assessment procedures, their use on airports, and the potential benefits to the aviation industry. In the Proceedings of the 26th Meeting of the International Bird Strike Committee, Warsaw, Poland, (5–9 May 2003). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/images/Resources/IBSC_Documents_Presentations/Warsaw/IBSC26_WPOS7.pdf.

- Dolbeer, R.A.; Wright, S.E. Safety management systems: how useful will the FAA national wildlife strike database be? Human – Wildlife Conflicts 2009, 3, 167–178. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=hwi.

- Dolbeer, R.A.; Wright, S.E.; Weller, J.R.; Anderson, A.L.; Begier, M.J. Wildlife strikes to civil aircraft in the United States 1990–2014. Federal Aviation Administration, Washington DC, United States, 2015. [CrossRef]

- DeFusco, R.P. The U.S. Air Force bird avoidance model. Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference 1998, 18. [CrossRef]

- Barras, S.C.; Seamans, T.W. Habitat management approaches for reducing wildlife use of airfields. Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference 2002, 20, 309–315. https://escholarship.org/content/qt5m88878j/qt5m88878j.pdf.

- Navin, J.; Weiler, S.; Anderson, A. Wildlife strike cost revelation in the US domestic airline industry. Transportation Research Part D 2020, 78, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Convention on international civil aviation, 4th ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 2006. https://www.icao.int/publications/Documents/7300_cons.pdf.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. State Letter: Damage to aircraft caused by bird strikes – provision of bird strike data to ICAO, AN 3/32 – 76/111, (14 July 1976).

- Hoon, A. de; Wong, Y. ICAO WHM Update. In the Proceedings of the WBA 2021 Conference, virtual, (13–14 January 2021). https://www.worldbirdstrike.com/wba-conferences/66-wba-conferences/167-wba-1st-virtual-conference-2021.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Manual on the ICAO bird strike information system (IBIS), 3rd ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 1989. https://www.icao.int/SAM/Documents/2013-BIRDH-STD/9332_3ed_en.pdf.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Doc 9981 – procedures for air navigation services – aerodromes, 2nd ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 2016. https://www.bazl.admin.ch/dam/bazl/de/dokumente/Fachleute/Flugplaetze/ICAO/icao_doc_9981_pans-aerodromes.pdf.download.pdf/ICAO%20doc%209981%20PANS-Aerodromes.pdf.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Annex 13 to the convention on international civil aviation – aircraft accident and incident investigation, 12th ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 2020. https://www.bazl.admin.ch/dam/bazl/de/dokumente/Fachleute/Regulationen_und_Grundlagen/icao-annex/icao_annex_13_aircraftaccidentandincidentinvestigation.pdf.download.pdf/AN13_cons.pdf.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Annex 19 to the convention on international civil aviation – safety management, 2nd ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 2016. https://www.bazl.admin.ch/dam/bazl/en/dokumente/Fachleute/Regulationen_und_Grundlagen/icao-annex/icao_annex_19_second-edition.pdf.download.pdf/an19_2ed.pdf.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Doc 9859 – safety management manual, 9th ed.; International Civil Aviation Organisation: Montreal, Canada, 2018. https://www.bazl.admin.ch/dam/bazl/en/dokumente/Fachleute/Flugplaetze/ICAO/icao_doc_9859_safetymanagementmanualsmm.pdf.download.pdf/icao_doc_9859_safetymanagementmanualsmm.pdf.

- Federal Aviation Administration. Advisory circular 150/5200-32b – reporting wildlife aircraft strikes. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington DC, United States, 2013. https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_150_5200-32B.pdf.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Easy access rules for occurrence reporting (Regulation (EU) no 376/2014), 3rd ed.; European Union, 2020. https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/easy_access_rules_for_occurrence_reporting_regulation_eu_no_376-2014.pdf.

- SKYbrary. Wildlife strike. SKYbrary, 2020. https://www.skybrary.aero/index.php/Wildlife_Strike.

- SKYbrary. Bird strike reporting. SKYbrary, 2020. https://www.skybrary.aero/index.php/Bird_Strike_Reporting.

- Civil Aviation Safety Amendment (Part 139) Regulations 2019 (Cth) (Austl.). https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2019L00176/latest/text.

- Transport Safety Investigation Regulations 2003 (Cth) (Austl.). https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2003B00171/latest/text.

- International Federation of Air Traffic Controllers’ Associations. Making SARPs : how does it work? Available online: https://ifatca.org/icao-activities/making-sarps-how-does-it-work/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Bliss, D.T. ICAO's Strength: Reinventing itself to address the challenges facing international aviation. Air & Space Law 2019, 32, 3–7. https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/air_space_lawyer/Winter2019/as_bliss.pdf.

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Making an ICAO SARP. Available online: https://www.icao.int/about-icao/AirNavigationCommission/Documents/How%20to%20Build%20an%20ICAO%20SARP.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. State Letter: Proposal for the amendment of Annex 14, Volume I and PANS-Aerodromes (Doc 9981) relating to aerodrome design and operations, AN 4/1.1.58 – 23/33, (30 May 2023). https://slcaa.gov.sl/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Proposal-for-Amendment-of-Annex-14-Vol-I_compressed.pdf.

- Salih, C. International Aviation Law for Aerodrome Planning; Sringer, Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Abeyratne, R. Rulemaking in Air Transport; Springer International, Switzerland, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.R.; Anderson, A.L. IBIS Manual for Strike Reporting (Doc 9332). Available online: https://www.icao.int/ESAF/Documents/meetings/2024/Wildlife%20Hazrd%20Management%205-9%20February%20Nairobi%20Kenya/IBIS-Nairobi-2024.pdf (accessed 13 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).