Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

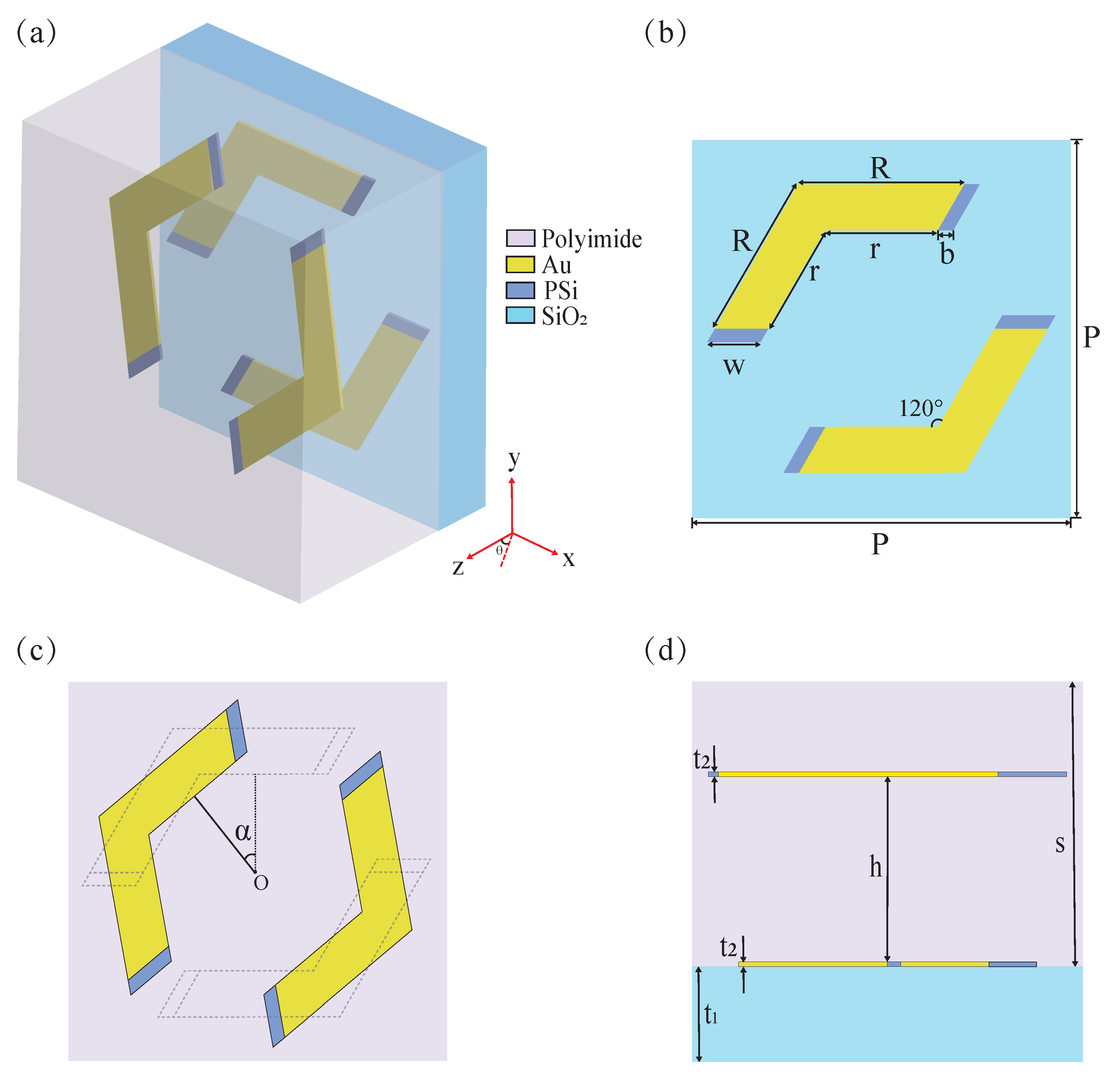

2. Structure Design and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

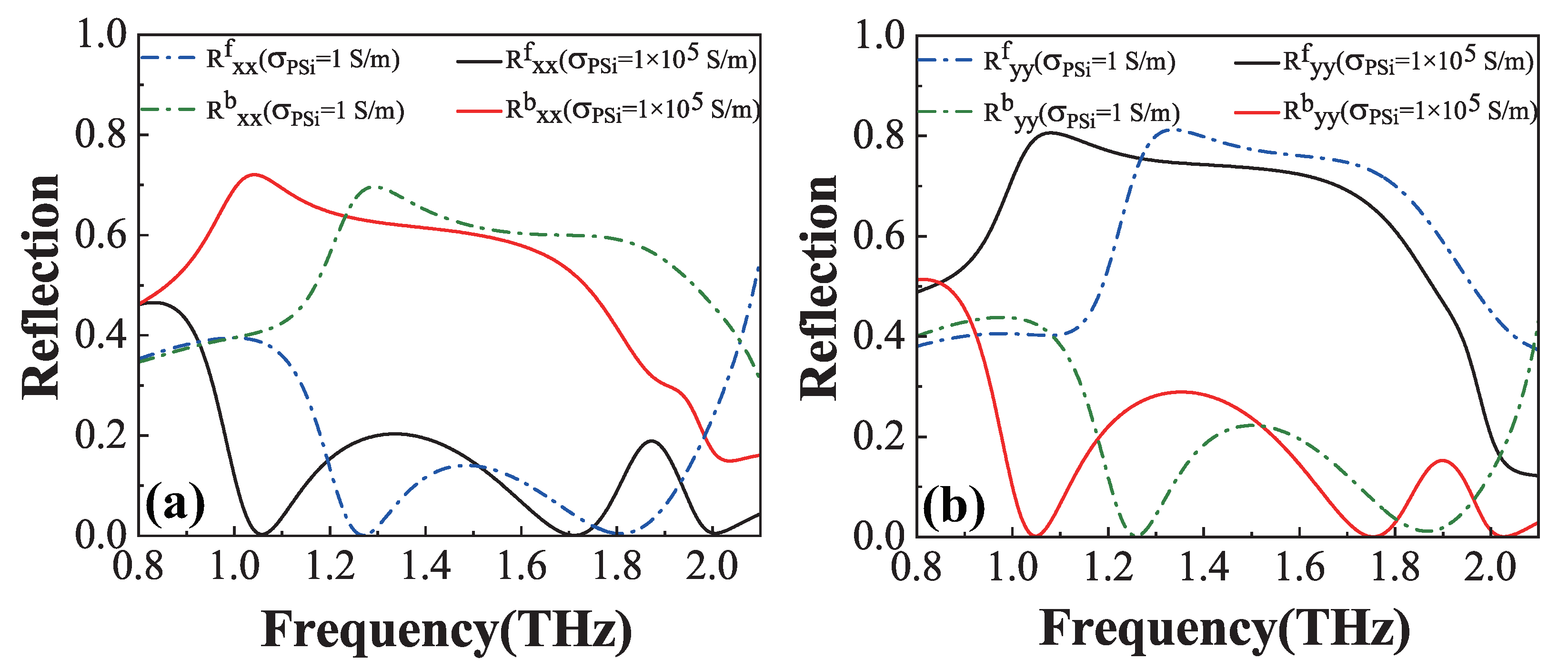

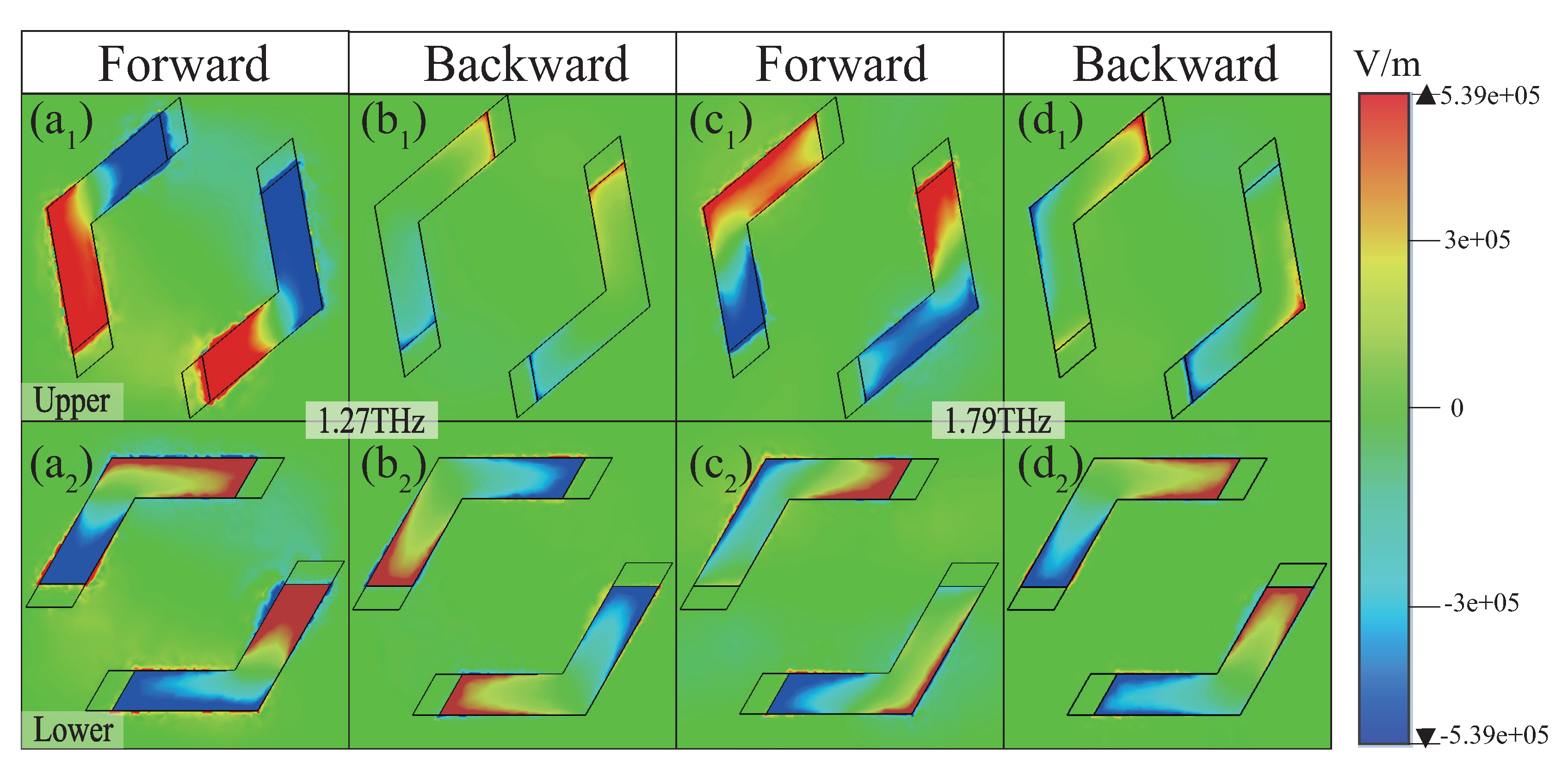

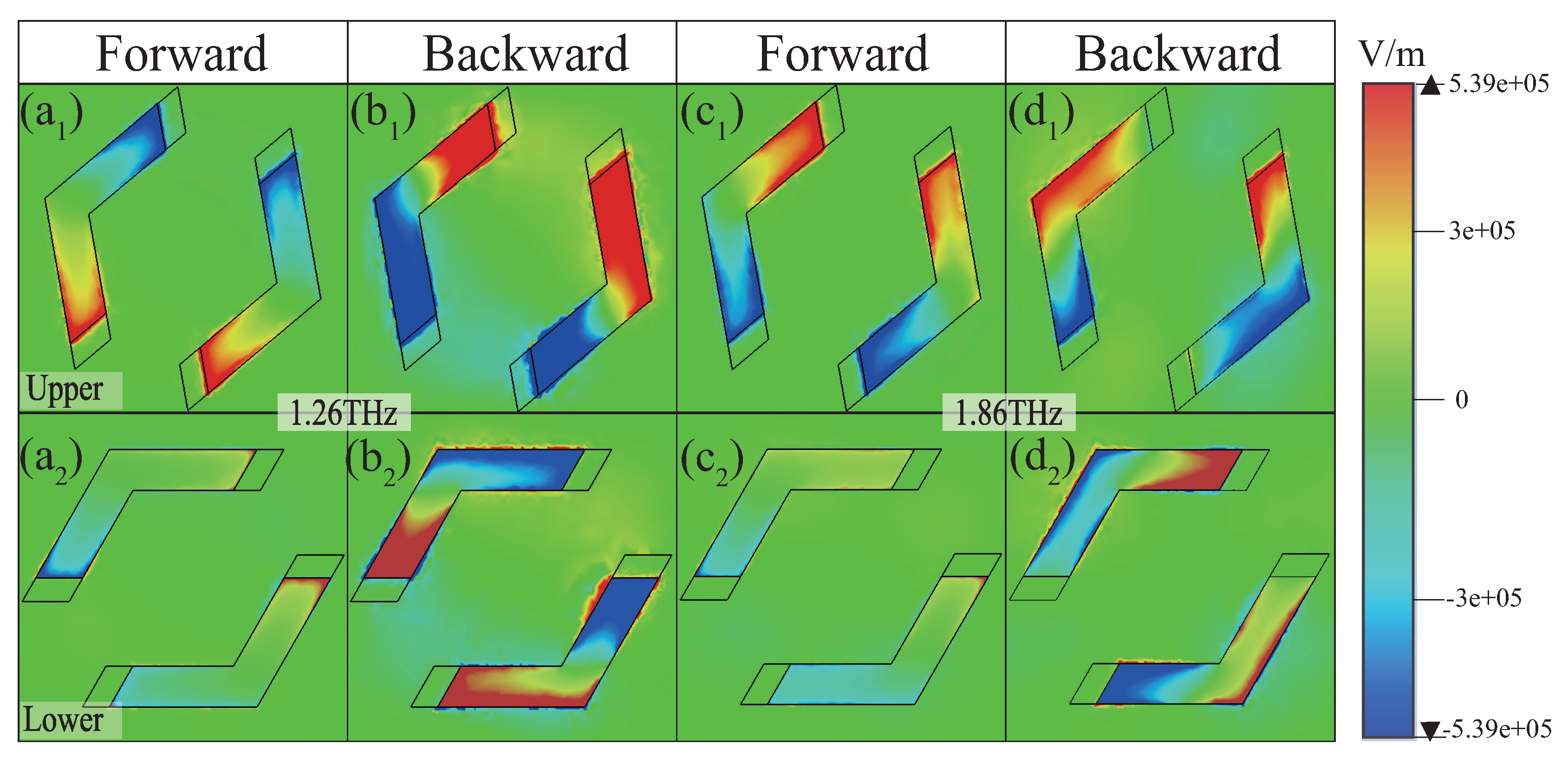

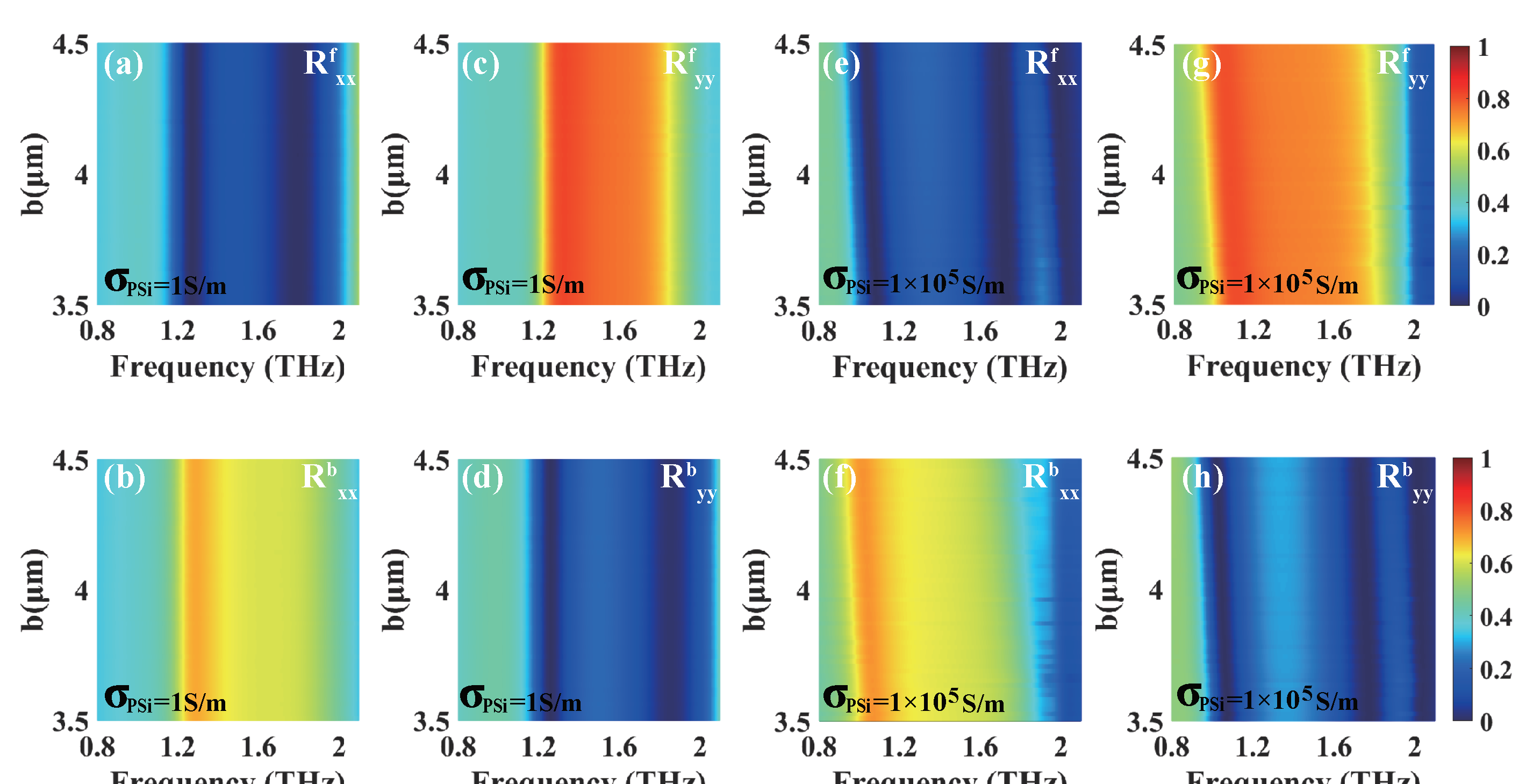

3.1. Unidirectional reflectionlessness

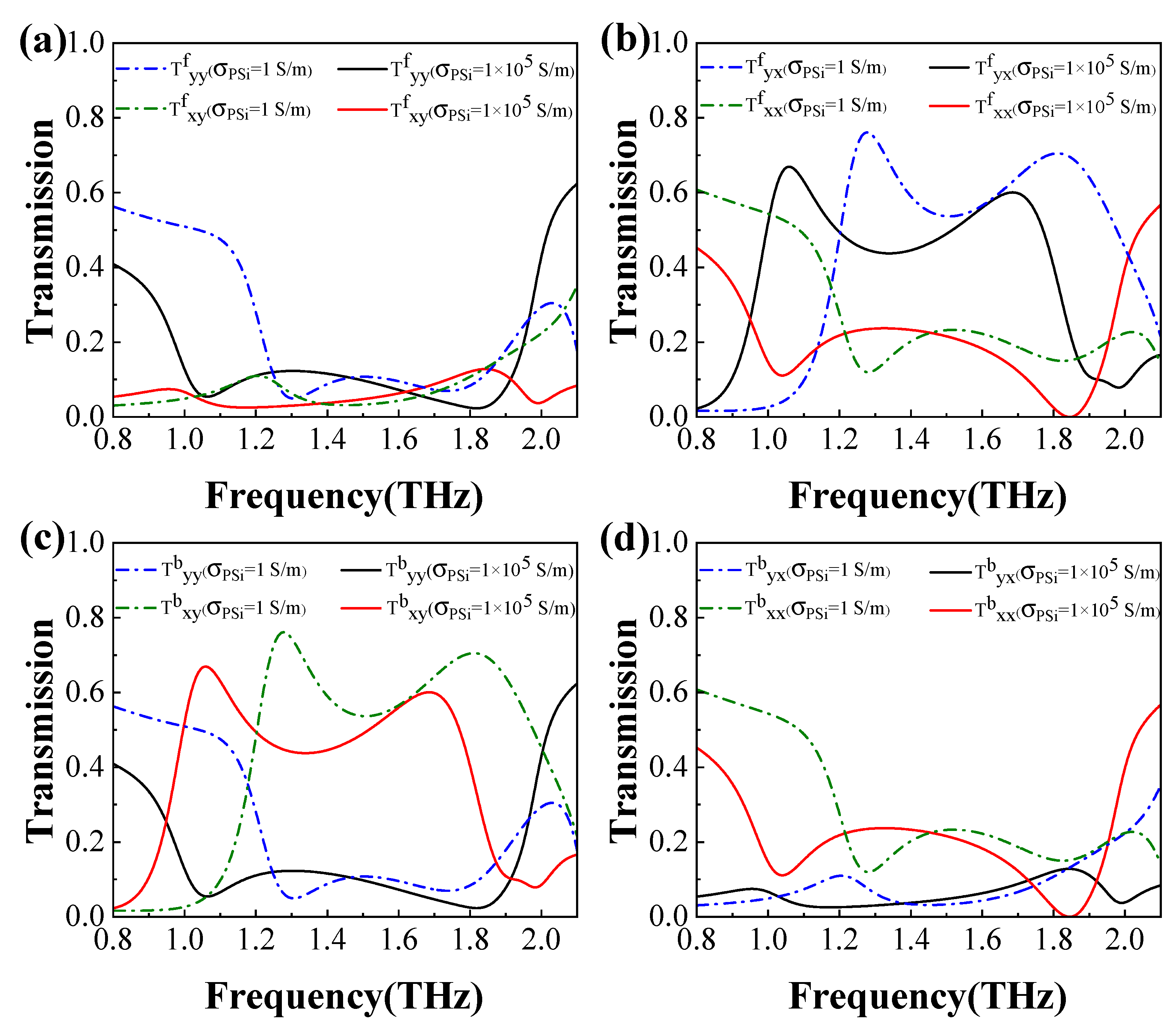

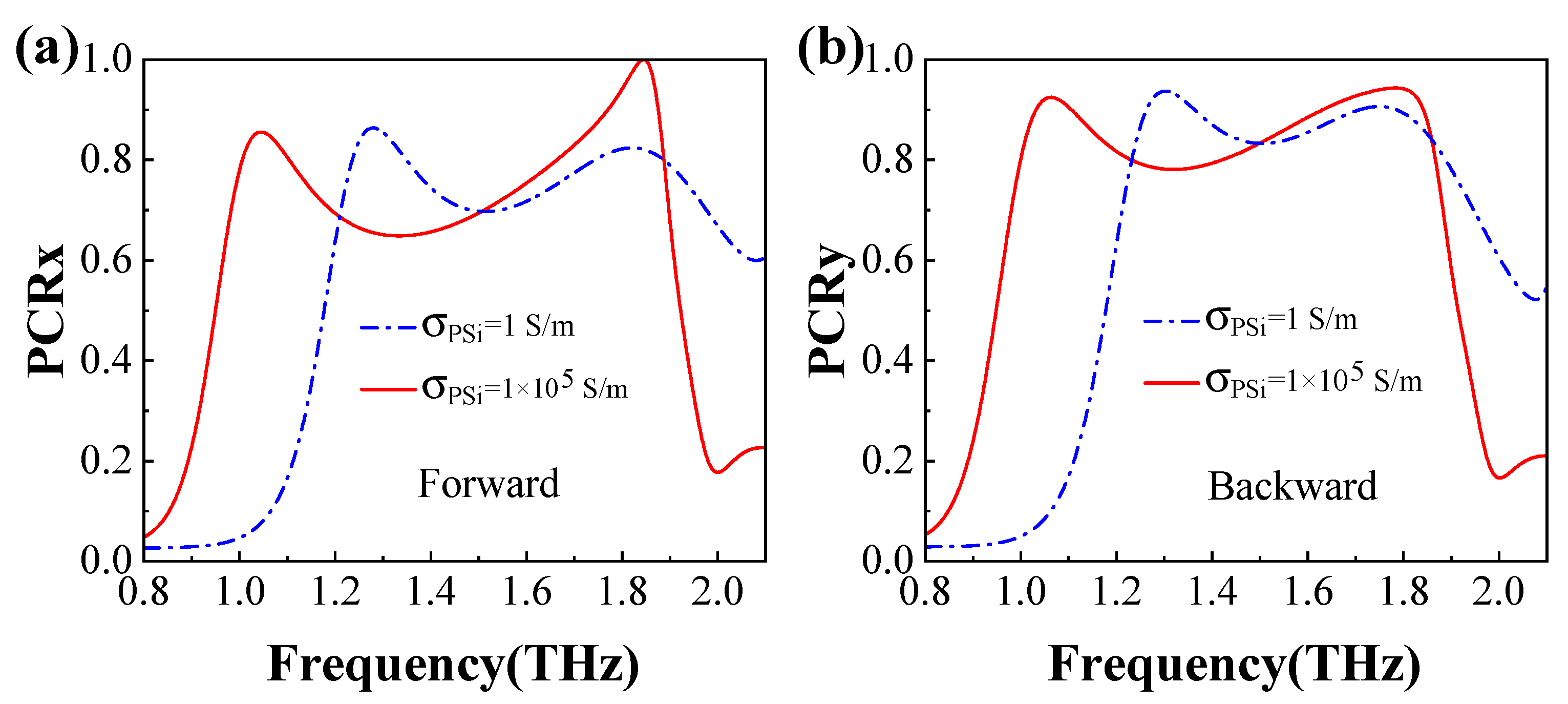

3.2. Polarization Conversion

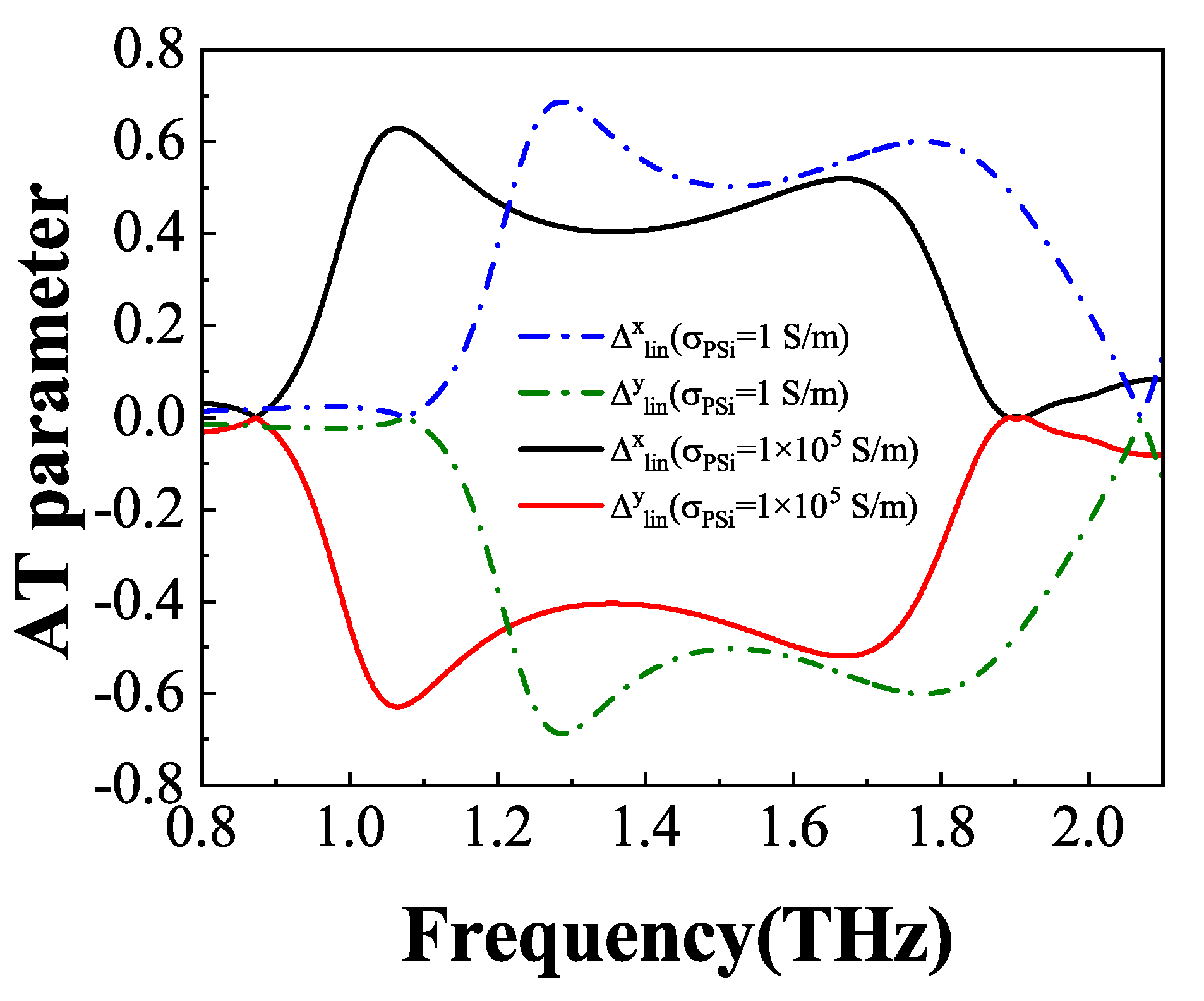

3.3. Asymmetric Transmission

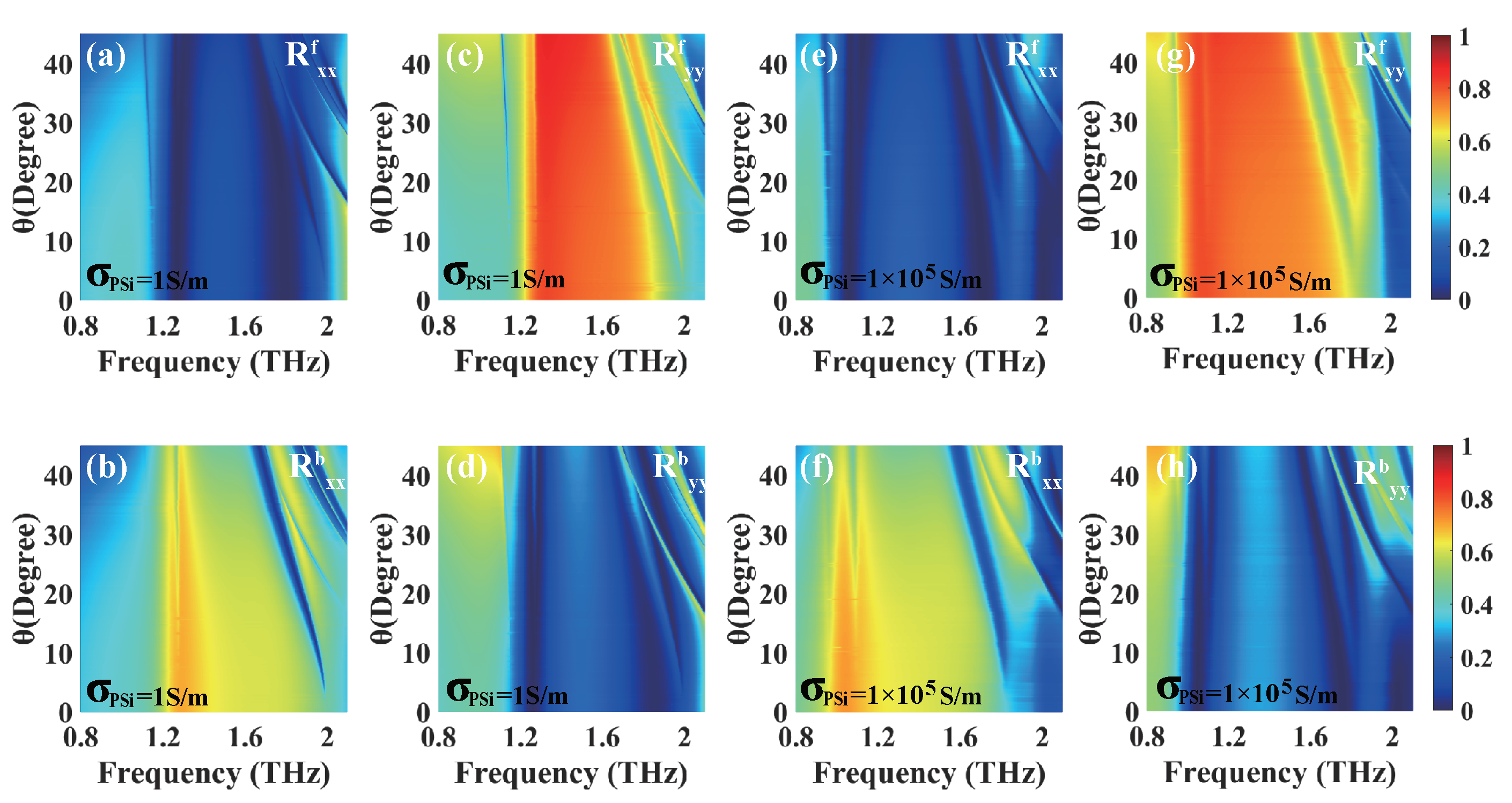

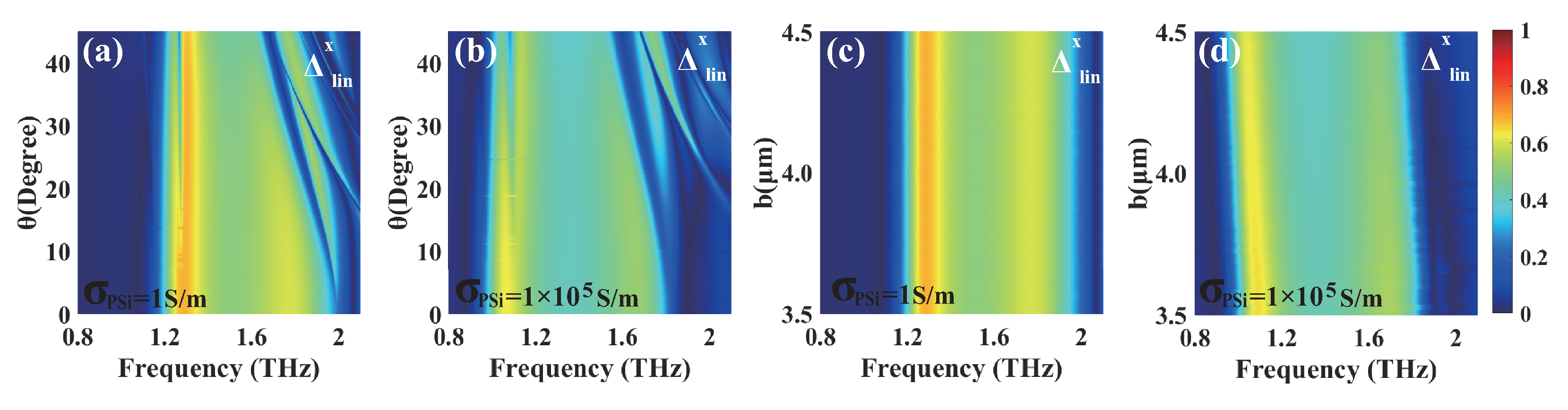

3.4. The Effect of Incident Angle and PSi Sheet Length on UR and AT

3.5. Relative Advantages and Potential Fabrication Processes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| THz | Terahertz |

| UR | Unidirectional Reflectionlessness |

| PC | Polarization Conversion |

| AT | Asymmetric Transmission |

| PSi | Photosensitive Silicon |

| PCR | Polarization Conversion Rate |

| T | Transmission |

| R | Reflection |

| A | Absorption |

| LPL | Linearly Polarized Light |

| CPL | Circularly Polarized Light |

| LTCPC | Linear to Circular Polarization Conversion |

| CDR | Circular Dichroism of Reflection |

| CDT | Circular Dichroism of Transmission |

| EIT | Electromagnetically Induced Transparency |

References

- Xu, C.; Ren, Z.H.; Wei, J.X.; Lee, C.K. Reconfigurable terahertz metamaterials: From fundamental principles to advanced 6G applications. Iscience 2022, 25, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, M.; Pitchappa, P.; Wang, N.; Szriftgiser, P.; Ducournau, G.; Singh, R.J. Phototunable chip-scale topological photonics: 160 Gbps waveguide and demultiplexer for THz 6G communication. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghoutane, B.; El Ghzaoui, M.; El Faylali, H. Spatial characterization of propagation channels for terahertz band. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Williams, K.; Dai, J.M.; Zhang, X.C.; et al. Observation of broadband terahertz wave generation from liquid water. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 071103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, I.V.K.; Elmaadawy, S.; Furlani, E.P.; Jornet, J.M. Photothermal effects of terahertz-band and optical electromagnetic radiation on human tissues. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Li, J.Q.; He, C.P.; Qin, J.S.; Chen, X.H.; Li, S.L. Enhancement of high transmittance and broad bandwidth terahertz metamaterial filter. Opt. Mater. 2021, 115, 111029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Dai, J.M.; Zhang, X.C. Coherent control of THz wave generation in ambient air. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 075005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.L.; Wang, Y. Structural optimization of metamaterials based on periodic surface modeling. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 395, 115057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billa, M.B.; Hakim, M.L.; Alam, T.; Almutairi, A.F.; Misran, N.; Soliman, M.S.; Islam, M.T. Near-ideal absorption high oblique incident angle stable metamaterial structure for visible to infrared optical spectrum applications. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2023, 55, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.X.; Ren, Z.H.; Lee, C. Metamaterial technologies for miniaturized infrared spectroscopy: Light sources, sensors, filters, detectors, and integration. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 240901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Sekiya, M.; Sato, T.; Takebayashi, Y. Negative refractive index metamaterial with high transmission, low reflection, and low loss in the terahertz waveband. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 8314–8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjappa, M.; Pitchappa, P.; Wang, N.; Lee, C.; Singh, R. Active control of resonant cloaking in a terahertz MEMS metamaterial. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Hasan, M.; Faruque, M. A new metamaterial-based wideband rectangular invisibility cloak. Appl. Phys. A 2018, 124, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; He, Y.H.; Lou, P.C.; Huang, W.Q.; Pi, F.W. Penta-band terahertz light absorber using five localized resonance responses of three patterned resonators. Results Phys. 2020, 16, 102930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Heo, N.; Park, J.; Seo, I.; Yoo, J. All-dielectric structure development for electromagnetic wave shielding using a systematic design approach. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 021908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devendran, M.; Beno, A.; Kannan, K.; Dhamodaran, M.; Sorathiya, V.; Patel, S.K. Numerical investigation of cross metamaterial shaped ultrawideband solar absorber. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2022, 54, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Li, W.Y.; Meng, T.H.; Zhao, G.Z. Design and optimization of terahertz metamaterial sensor with high sensing performance. Opt. Commun. 2021, 494, 127051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.F.; Bai, R.P.; Jin, X.R.; Zhang, Y.Q.; An, C.S.; Lee, Y. Dual-band unidirectional reflectionless propagation in metamaterial based on two circular-hole resonators. Materials 2018, 11, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.L.; Xu, D.Y.; Yin, F.H.; Yang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; An, C.S.; Jin, X.R. A versatile meta-device for linearly polarized waves in terahertz region. Phys. Scripta 2024, 99, 025517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.T.; Li, X.; Liu, G.D.; Wang, L.L.; Lin, Q. Analytical investigation of unidirectional reflectionless phenomenon near the exceptional points in graphene plasmonic system. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 30458–30469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, J.; Shim, J.; Son, H.; Park, J.; Baek, S.; Kim, T.T. Broadband metamaterial polarizers with high extinction ratio for high-precision terahertz spectroscopic polarimetry. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 110807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Plum, E.; Menzel, C.; Rockstuhl, C.; Azad, A.; Cheville, R.; Lederer, F.; Zhang, W.; Zheludev, N. Terahertz metamaterial with asymmetric transmission. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 153104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, U.U.R.; Deng, B.; Wu, X.D.; Xiong, C.J.; Jalal, A.; Khan, M.I.; Hu, B. Chiral terahertz metasurface with asymmetric transmission, polarization conversion and circular dichroism. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 32836–32848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.Y.; Lv, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Jin, X.R. Unidirectional reflectionlessness, asymmetric reflection, and asymmetric transmission with linear and circular polarizations in terahertz metamaterial. Aip Adv. 2024, 14, 095121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.H.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Jin, X.R. Manipulation of unidirectional reflectionlessness and asymmetric transmissionlessness in terahertz metamaterials. Opt. Commun. 2023, 533, 129309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.Q.H.; Nguyen, T.M.; Nguyen, H.Q. High efficient bi-functional metasurface with linear polarization conversion and asymmetric transmission for terahertz region. J. Opt. 2025, 27, 015104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Cao, Q.S.; Khan, M.I.; Shah, G.; Ahmed, F.; Khan, M.I.; Abidin, Z.U. An angular stable ultra-broadband asymmetric transmission chiral metasurface with efficient linear-polarization conversion. Phys. Scripta 2024, 99, 035519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Xia, K.; Zhang, L. Multifunctional and tunable metastructure based on VO2 for polarization conversion and absorption. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 34586–34600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Z.; Zhang, H.W.; Ren, G.J.; Xue, L.F.; Yao, J.Q. Photosensitive silicon-based tunable multiband terahertz absorber. Opt. Commun. 2022, 523, 128681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.H. Achieving broadband absorption and polarization conversion with a vanadium dioxide metasurface in the same terahertz frequencies. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 12487–12497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Yang, R.C.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, W.M.; Tian, J.P. VO 2-assisted multifunctional metamaterial for polarization conversion and asymmetric transmission. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 27407–27417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.L.; Zhong, R.B.; Liang, Z.K.; Fang, Z.; Fang, J.H.; Zhang, H.M.; Wu, Z.H.; Zhang, K.C.; Hu, M.; Liu, D.W. A tunable multifunctional terahertz asymmetric transmission device hybrid with vanadium dioxide blocks. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 881229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.X.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Jin, X.R. Tunable unidirectional reflectionlessness based on vanadium dioxide in a non-Hermitian metamaterial. Phys. Scripta 2024, 99, 125550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.B.; Yang, J.B.; Huang, J.; Bai, W.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, Z.J.; Xu, S.Y.; Xie, W.L. The novel graphene metasurfaces based on split-ring resonators for tunable polarization switching and beam steering at terahertz frequencies. Carbon 2019, 154, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Kong, X.K.; Liu, S.B.; Ahmed, A.; Rahman, S.U.; Wang, Q. Graphene-based THz tunable ultra-wideband polarization converter. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 384, 126567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.P.; Fan, S.T.; Zhao, J.J.; Xu, J.Z.; Zhu, J.F.; Wang, X.R.; Qian, Z.F. A multi-functional tunable terahertz graphene metamaterial based on plasmon-induced transparency. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 141, 110686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.X.; Xiong, J.F.; Wang, T.R.; Wang, S.Z.; Zhang, Y.D.; Wen, H.; et al. Multifunctional analysis and verification of lightning-type electromagnetic metasurfaces. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 17008–17025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.L.; Li, J.S. Bi-directional multi-function terahertz metasurface. Opt. Commun. 2023, 529, 129105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.C.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, S.L.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, W.R. Large and active circular dichroism in a photosensitive silicon based metasurface. J. Opt. 2024, 26, 035101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.S.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, Y.L.; Huang, J.Z.; Zhu, J.W.; Guo, C.P. Monolayer actively tunable dual-frequency switch based on photosensitive silicon metamaterial. Opt. Commun. 2024, 562, 130557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Z.; Liu, S.Y.; Ren, G.J.; Zhang, H.W.; Liu, S.C.; Yao, J.Q. Multi-parameter tunable terahertz absorber based on graphene and vanadium dioxide. Opt. Commun. 2021, 494, 127050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.G.; Li, Y.Z.; Wu, T.T.; Qiu, Q.X.; Duan, J.X.; Jiang, L.; Mao, W.C.; Yao, N.J.; Huang, Z.M. Terahertz metasurface modulators based on photosensitive silicon. Laser Photonics Rev. 2023, 17, 2200808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.X.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Wang, X.W.; Cheng, P. Integrated metamaterial with the functionalities of an absorption and polarization converter. Appl. Opt. 2023, 62, 3519–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E.F.; Kim, J.K.; Xi, J.Q. Low-refractive-index materials: A new class of optical thin-film materials. phys. stat. sol. (b) 2007, 244, 3002–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Zuo, S.; Li, M.; Yang, S.; Jia, Y.; Gao, Y. Switchable and tunable terahertz metamaterial based on vanadium dioxide and photosensitive silicon. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Gong, R.Z.; Zhao, J.C. A photoexcited switchable perfect metamaterial absorber/reflector with polarization-independent and wide-angle for terahertz waves. Opt. Mater. 2016, 62, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Li, X.J. Switchable tri-function terahertz metasurface based on polarization vanadium dioxide and photosensitive silicon. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 12823–12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Qi, Y.P.; Zhou, Z.H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, X.X. Switchable bi-functional metasurface for absorption and broadband polarization conversion in terahertz band using vanadium dioxide and photosensitive silicon. Nanotech. 2024, 35, 195205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Yang, R.C.; Li, Z.H.; Tian, J.P. Reconfigurable multifunctional polarization converter based on asymmetric hybridized metasurfaces. Opt. Mater. 2022, 124, 111953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Miao, X.; Jiang, X.X.; Li, A.Q. Tunable and switchable common-frequency broadband terahertz absorption, reflection and transmission based on graphene-photosensitive silicon metamaterials. Opt. Commun. 2023, 541, 129555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zuo, S.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.C.; Yang, S.; Jia, Y.; Gao, Y.C. Difunctional terahertz metasurface with switchable polarization conversion and absorption by VO 2 and photosensitive silicon. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 19719–19726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, B.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, Y. High-efficiency and tunable circular polarization selectivity in photosensitive silicon-based zigzag array metasurface. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 156, 108453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, C.; Gao, P.; Dai, Y.; Lu, X.; Wan, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X. Switchable multifunctional metasurface based on electromagnetically induced transparency and photosensitive silicon. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Yang, R.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Tian, J. Photoexcited switchable single-/dual-band terahertz metamaterial absorber. Mater. Res. Express. 2019, 6, 075807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.T.; O’hara, J.F.; Azad, A.K.; Taylor, A.J.; Averitt, R.D.; Shrekenhamer, D.B.; Padilla, W.J. Experimental demonstration of frequency-agile terahertz metamaterials. Nature Photon. 2008, 2, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanpour, J.; Beyraghi, S.; Cheldavi, A. Ultrafast reprogrammable multifunctional vanadium-dioxide-assisted metasurface for dynamic THz wavefront engineering. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Incident light type | Tunable material | Function | PC type | Spectrum range | Frequency shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPL | PSi,VO2 | PC, LTCPC | R,T | THz | No | |

| LPL | PSi,Graphene | T,A,R | No | THz | No | |

| LPL | PSi,VO2 | PC,A | T | THz | No | |

| CPL | PSi | CDR,CDT | No | THz | No | |

| LPL | PSi | EIT | No | THz | No | |

| LPL | PSi | A | No | THz | Red-shift, Blue-shift | |

| This work | LPL | PSi | UR,PC,AT | T | THz | Red-shift |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).