1. Introduction

Bioactive glass (BG) has emerged as a prominent biomaterial, gaining a lot of attention in the field of biomaterials due to its favourable characteristics including versatility, bioactivity, ease of synthesis, cost-effectiveness, and application in regenerative medicine and drug delivery [

1]. BG can be synthesized through melt-quenching, sol-gel [

2], flame synthesis [

3] and microwave-assisted synthesis [

4,

5]. Each method results in BG with unique properties that can be used for different applications. Sol-gel BG has gained a lot of interest due to its higher porosity and increased surface area, which leads to improved bioactivity as the increased surface area allows for more rapid ion exchange with biological fluids and the formation of an apatite-like layer on its surface [

6,

7]. Specifically, the tertiary system of SiO2-CaO-P2O5 is one of the most widely utilized and studied BG systems due to its versatility and adaptability in various biomedical applications [

8]. This versatility can be attributed to the inclusion of network formers, like SiO2 P2O5, which contribute to the structure of the glass and network modifiers such as CaO which enhance bioactivity and mechanical properties [

9,

10]. Typically, the synthesis of this system involves high thermal treatment to remove organics and nitrates [

8]. However, recent studies have reported successful synthesis of bioactive glass without the need for thermal treatment [

11,

12]. This expands the uses and applications of bioactive glass to include pre-loaded drugs. This study will look at the ability of synthesizing BG-preloaded with antibiotics and to test its ability to deliver these drugs over a long time aimed to treat infections like biofilms that develop on prosthetics following prosthetic joint surgeries.

Biofilms are colonies of bacterial species that are protected by a self-produced polymeric matrix that can invade inert or living surfaces [

13]. These colonies require prolonged antimicrobial exposure above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). A drug delivery system that aims to treat these infections needs to load enough antibiotics to deliver them over at least a month with minimal burst release to not cause any toxicities locally at the infection site. BG can be designed to load antibiotics during synthesis to deliver them over an extended period as the matrix gradually degrades, making them ideal for the treatment of biofilm and biofilm-related infections. Vancomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic, is often the antimicrobial of choice when treating these biofilm infections as it has proven to be effective in penetrating the biofilm matrix. Vancomycin acts by binding to cell precursors that are essential for the integrity of cell wall development, which is effective in killing bacterial cells [

14]. The choice of antibiotics by surgeons trying to treat biofilms due to their familiarity and common use, the number of pathogens it can attack, its successful release from bone cement [

15].

Vancomycin incorporation into BG has traditionally been achieved through post-synthesis depletion methods, with varying degrees of success. This approach involves immersing BG particles in drug solutions of different concentrations, with loading efficiency determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy measurements before and after immersion. Previous studies have demonstrated a wide range of loading efficiencies, heavily influenced by BG composition, synthesis methods, and templating techniques. Highly porous mesoporous bioactive glasses (MBGs) have shown antibiotic loading efficiencies ranging from 50-90%, with release durations spanning from a few hours to over 25 days [

13]. Anand et al. reported loading efficiencies of approximately 40% for Ceftriaxone and sulbactam sodium in MBGs [

16], while Xia et al. achieved 36-48% loading efficiency for gentamicin [

17]. This study aims to enhance antimicrobial loading, specifically vancomycin, by incorporating the drug during the BG synthesis process. This approach is expected to promote stronger chemical interactions between vancomycin molecules and the BG matrix, potentially improving loading efficiency and releasing kinetics.

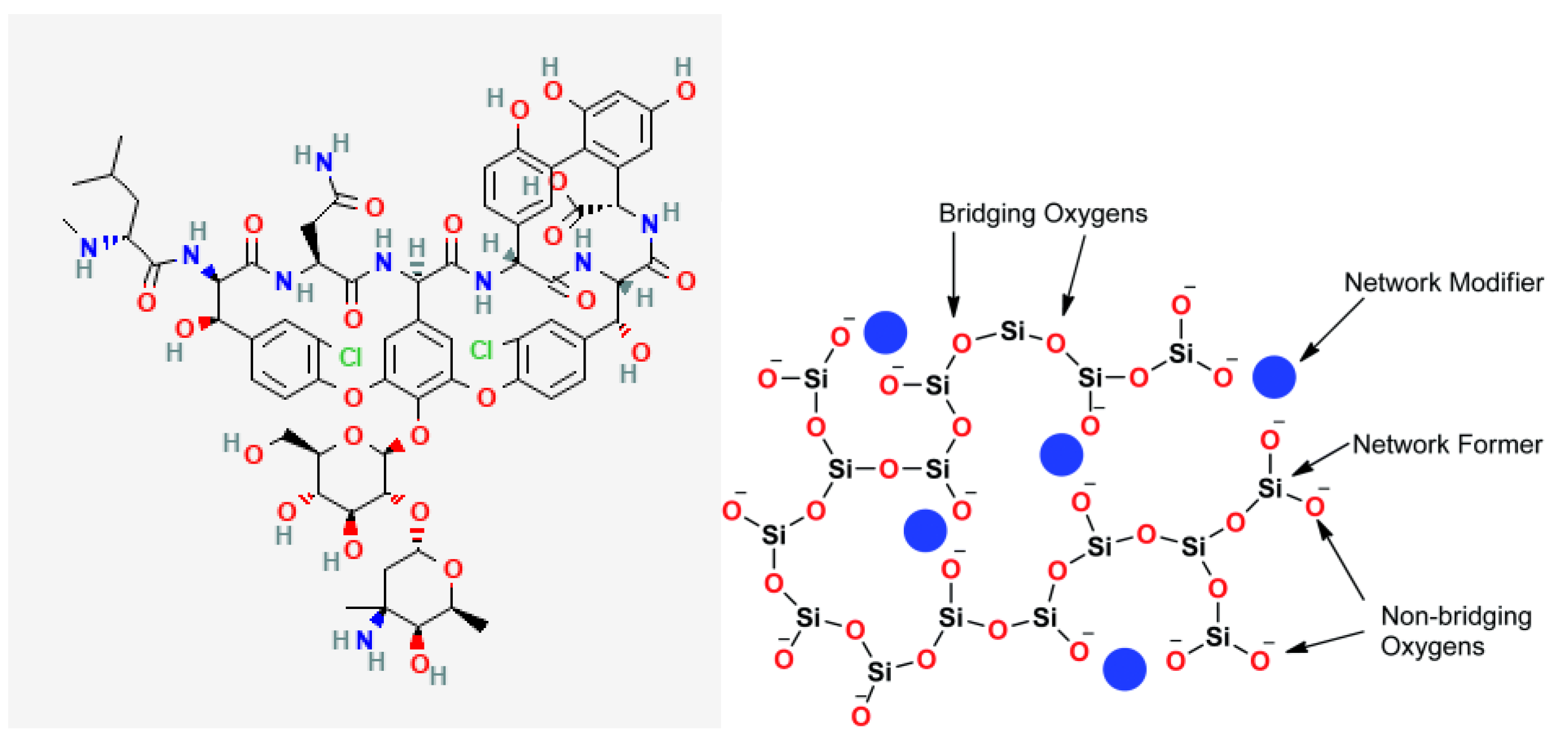

When BG is loaded with any drug, chemical bonds are expected to form between BG and the drug of choice based on their chemical structures. The interactions will strongly affect the encapsulation efficiency of the drug and subsequent release. For this study, vancomycin was chosen for the reasons previously stated. When BG is loaded with vancomycin there is a high potential of forming hydrogen bonds between the two. This is primarily due to the presence of multiple functional groups in vancomycin’s structure, such as amide, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups [

18], which can interact with the silanol groups (Si-OH) on the surface of the BG. These hydrogen bonds are stronger than simple physical adsorption forces, resulting in vancomycin being held more tightly within the BG matrix compared to surface adsorption alone.

Figure 1.

Structure of (a) Vancomycin molecule and (b) bioactive glass structure [

19]

.

Figure 1.

Structure of (a) Vancomycin molecule and (b) bioactive glass structure [

19]

.

This study aims to establish the ability of BG to load drugs during synthesis and its bioactivity and biocompatibility in vitro when it is synthesized without thermal treatment. BG is a versatile biomaterial that can be used in various applications including bone regeneration and drug delivery. BG properties such as porosity surface chemistry, and degradation rate are highly influenced by the synthesis method. These properties can be tailored differently based on the application, enabling customization and the creation of application-specific biomaterial.

3. Results and Discussion

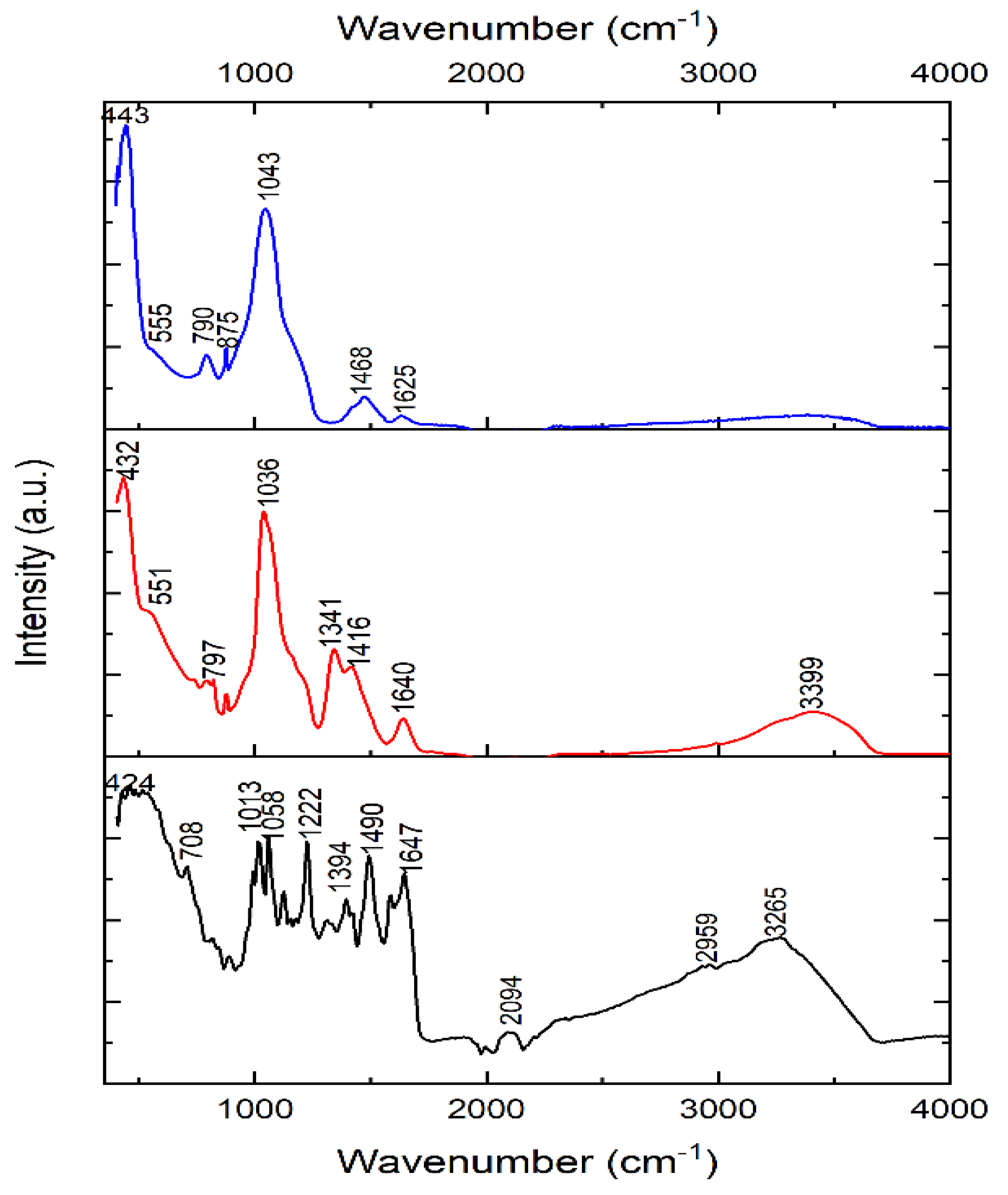

Figure 2 shows the FTIR of the as-synthesized BG-V (red), Vancomycin (black) and BG (blue). Vancomycin spectrum shows peaks at 424, 708, 1013, 1058, 1222, 1394, 1490, 1647, 2094, 2959 and 3265 cm-1 which signify the functional groups of vancomycin including the amide and hydroxyl stretch around 3265 cm-1, C=O stretching vibration from the amide bonds around 1647 cm-1 and C-N stretching and bending vibration peaks in the 1200-1500 cm-1 range [

25]. The peaks observed at 2094 and 2959 cm-1 represent the R-NH-R and -CH2-CH3 functional groups, respectively. BG spectra peaks include 443, 790, 875, 1043 and 1468 cm-1, which signify the characteristics of silica, phosphate and carbonate peaks. The peaks observed at 790 and 1043 cm-1 represent Si-O-Si stretching and bending vibrations characteristic of the silicate glass, the peak observed at 875 represents the P-O bending vibration, and the peak at 1468 represents the carbonate group (CO3-2) [

26]. BG-V spectra show peaks at 432, 797, 1036, 1341, 1416, 1640 and 3399 cm-1, which signify the characteristics of silica, phosphate and carbonate peaks similar to the BG spectra. Specifically, the peaks at 1036 and 797 cm-1 represent the Si-O-Si stretching and bending vibrations, characteristic of silicate glass structures. The broad peak at 3399 cm-1 suggests hydroxyl stretching with a shift of the peak for the BG-V, indicating interactions between the hydroxyl and amide groups. The higher intensity of the peaks observed at 1341, and 1416 cm-1 of the BG-V suggests the integration of vancomycin into the BG pores during synthesis. The peak at 1640 cm-1 suggests retained amide C=O stretching, indicating vancomycin’s integrity within the composite.

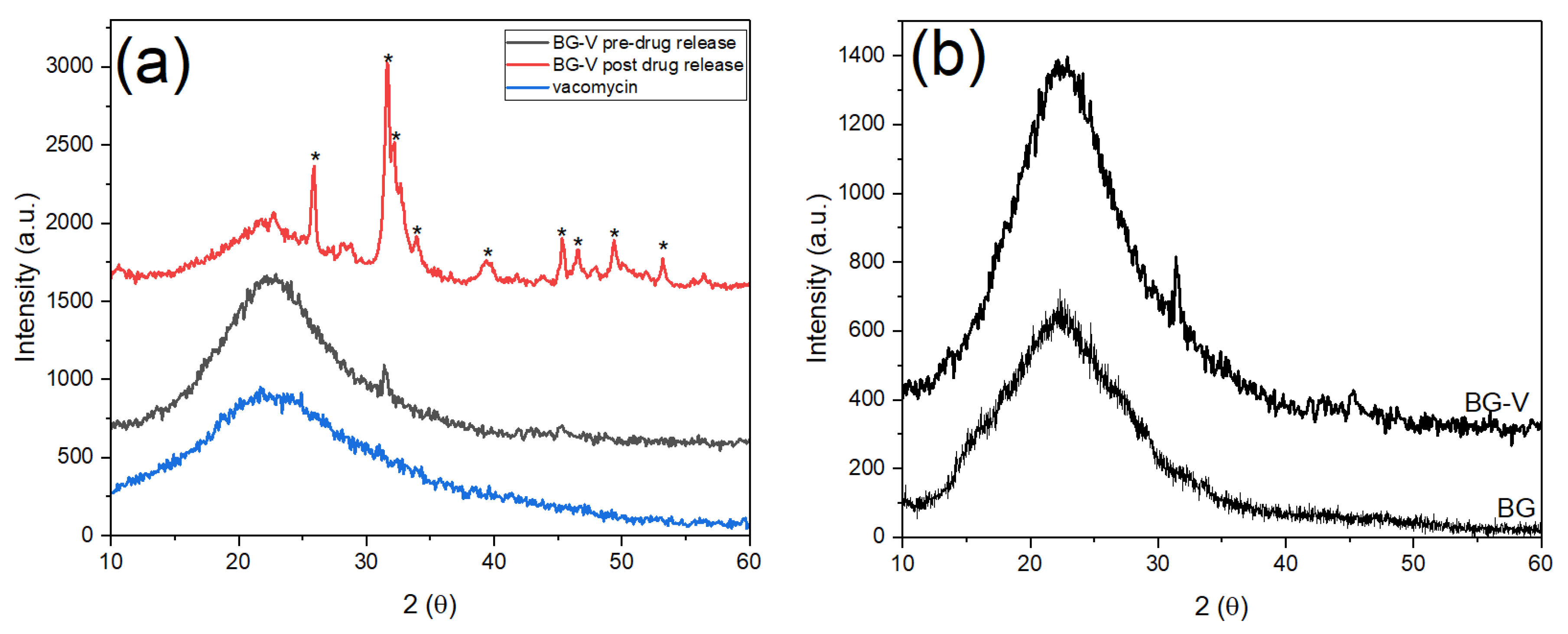

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of vancomycin and BG-V before and after drug release studies. The black amorphous pattern represents the glass before immersion in PBS for drug release, while the red pattern shows the crystalline phase after immersion in PBS. The blue patter shows the vancomycin spectrum which has an amorphous structure with a broad band that starts at ~10.2° and ends around ~38.8°which was also observed in other studies [

27]. The black pattern shows the amorphous BG-V structure with a broad band ~10° and ~35° that is characteristic of bioactive glass before immersion in PBS [

28]. The integration of vancomycin can be observed through the higher intensity of BG-V pattern as the two broad peaks overlap as observed in

Figure 3 (b), which compares the XRD pattern of BG without vancomycin and BG-V.

Figure 3 (b) shows BG-V which has a broad amorphous peak with an intensity going up to 1127 a.u. while the BG without vancomycin had the highest intensity at 680 a.u the intensities were measured starting at the same intensity of 0 a.u. but the figure shows both spectra to clarify differences between the spectra.

Figure 3 (a) also shows the XRD pattern of BG-V after the drug release (red) which revealed distinct crystalline structures formed on the BG after immersion, signifying the formation of hydroxyapatite (HA) and indicating the degradation of the glass as it releases vancomycin. The development of HA on the surface of BG-V is confirmed by the presence of the following diffraction peaks at θ =25.9°, 31.6°, 32.2°, 32.7°, 39.7° corresponding to the (002), (211) and (310) reflections of the HCA crystals [

29].

Hydroxyapatite (HA) is the mineral component of bone and based on the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDF) 09-0432, when detected through XRD different peaks will appear at 25.87°, 31.77°, 32.19°, 32.9° and 39.81° representing the (h,k,l) diffraction planes (002), (211), (300) and (310) respectively. Additionally, peaks appearing at θ 45.3°, 46.5°,49.4°, 53.2° which represent the (203), (222), (213) and (004), (422) respectively [

22]. After drug release in PBS, BG-V shows incredible bioactivity indicating that the glass is biodegrading as it releases the loaded vancomycin in vitro. The deposition of HA on BG-V emphasizes its suitability for bone regeneration and antimicrobial applications, demonstrating its dual function of enhancing bone integration while mitigating bacteria.

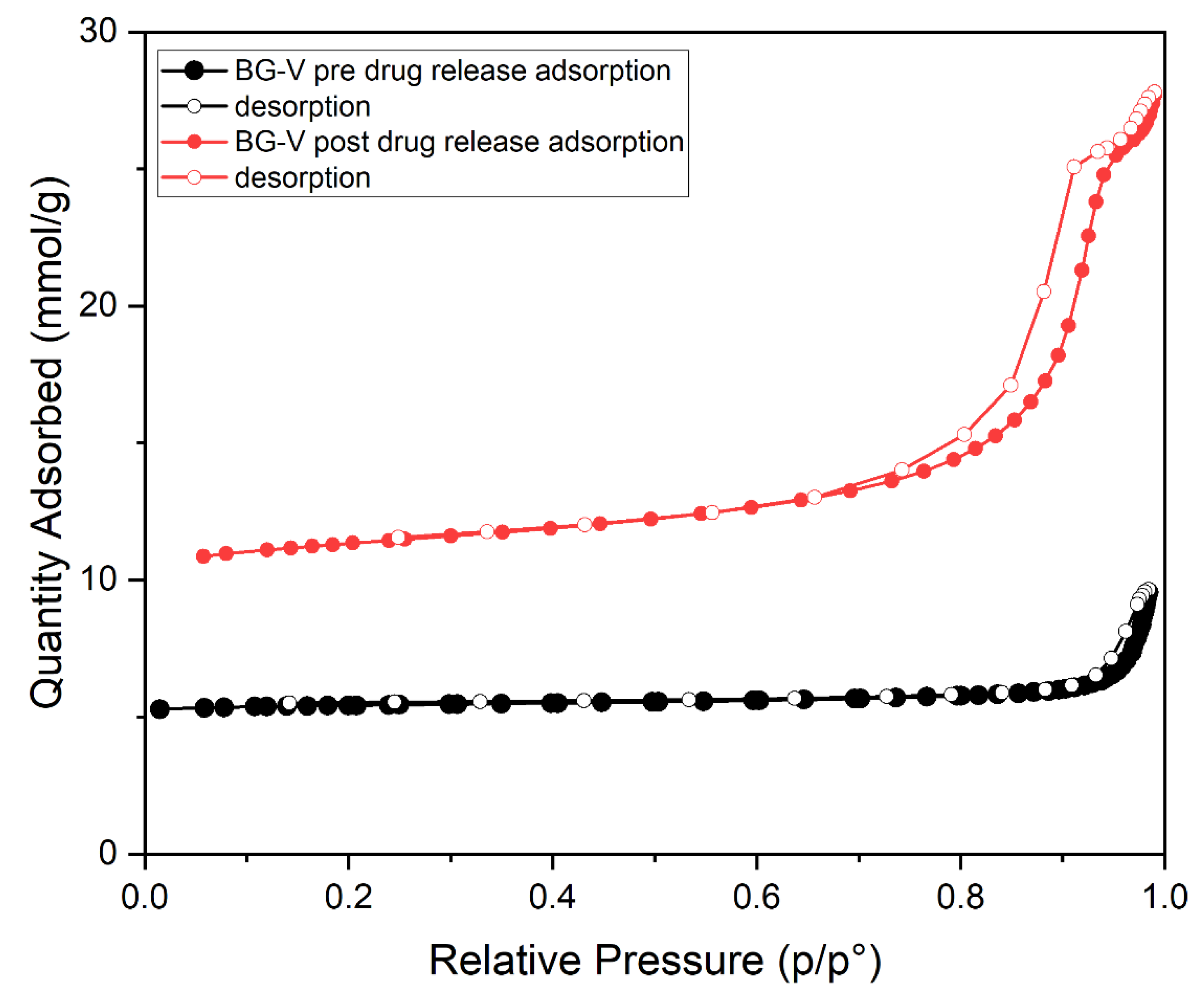

The nitrogen adsorption-desorption graph shown in

Figure 4 represents the BG-V before drug release (black). It is observed that the graph shows type IV isotherm with no hysteresis, indicating that there is a lower surface area as the pores are blocked by adsorption of vancomycin onto the BG. The second graph in red shows that after the drug is released, the isotherm observed is type IV with hysteresis indicating a vertically oriented horn-shaped pore [

30]. This shows that following drug release the pores of BG-V open up, and the surface area increases, this aids in the gradual release of the vancomycin from the BG as it allows it to release the physically adsorbed drug followed by drug entrapped inside that is being held by hydrogen bonds. The development of hydroxyapatite on the surface of BG also contributes to the increase in the surface area as the silanol layer (Si-OH) is being converted into HA.

Table 1 presents the data obtained from BET analysis, including surface area, pore volume, and pore size. Measurements were taken both before and after the drug release test to evaluate changes over time. A significant increase in surface area is observed from before drug release and after. On day 0, the surface area was measured at 20.23 m²/g, which increased to 156.64 m²/g after drug release, suggesting pore opening and drug release. This increase may also indicate the formation of HA on the surface or pore widening due to the biodegradation of BG-V when immersed in PBS.

The results further reveal changes in pore volume. At day 0, the pore volume was recorded at approximately 0.128 cm³/g, increasing to 0.613 cm³/g following the drug release study. This suggests that the release of the drug from the pores contributed to pore expansion, allowing more gas to adsorb on the surface during the second BET analysis.

Pore size measurements, recorded in nanometers, show a shift from 23.27 nm before drug release to 15.05 nm after drug release. This reduction may result from the deposition of HA on the surface, leading to the formation of numerous smaller pores. The reprecipitation of material on the glass surface could explain the simultaneous increase in surface area and decrease in average pore size.

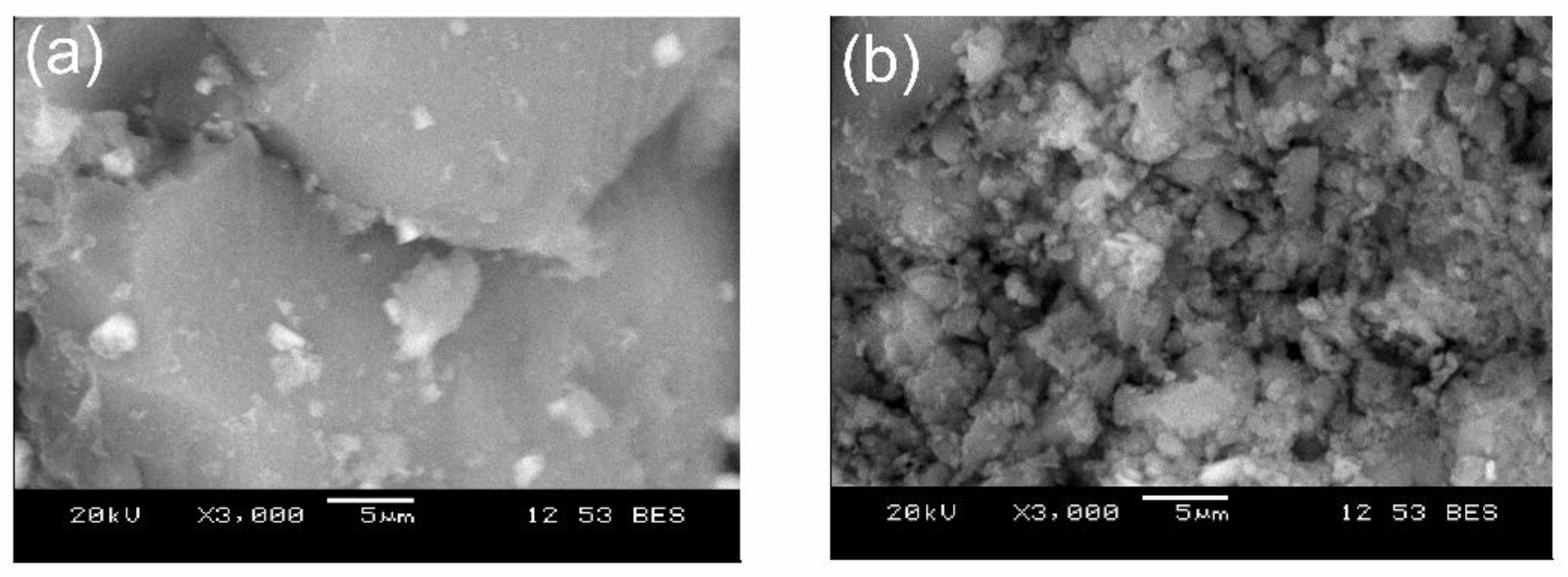

Figure 5 shows the SEM images of the as-synthesized BG-V before and after drug release studies. The first image (a) shows a smooth and dense surface at day 0, while the second image (b) shows the crystallization of the apatite layer on the surface of the BG.

Figure 4 (b) shows an increase in porosity which can be attributed to the degradation of BG as well as the release of the preloaded vancomycin.

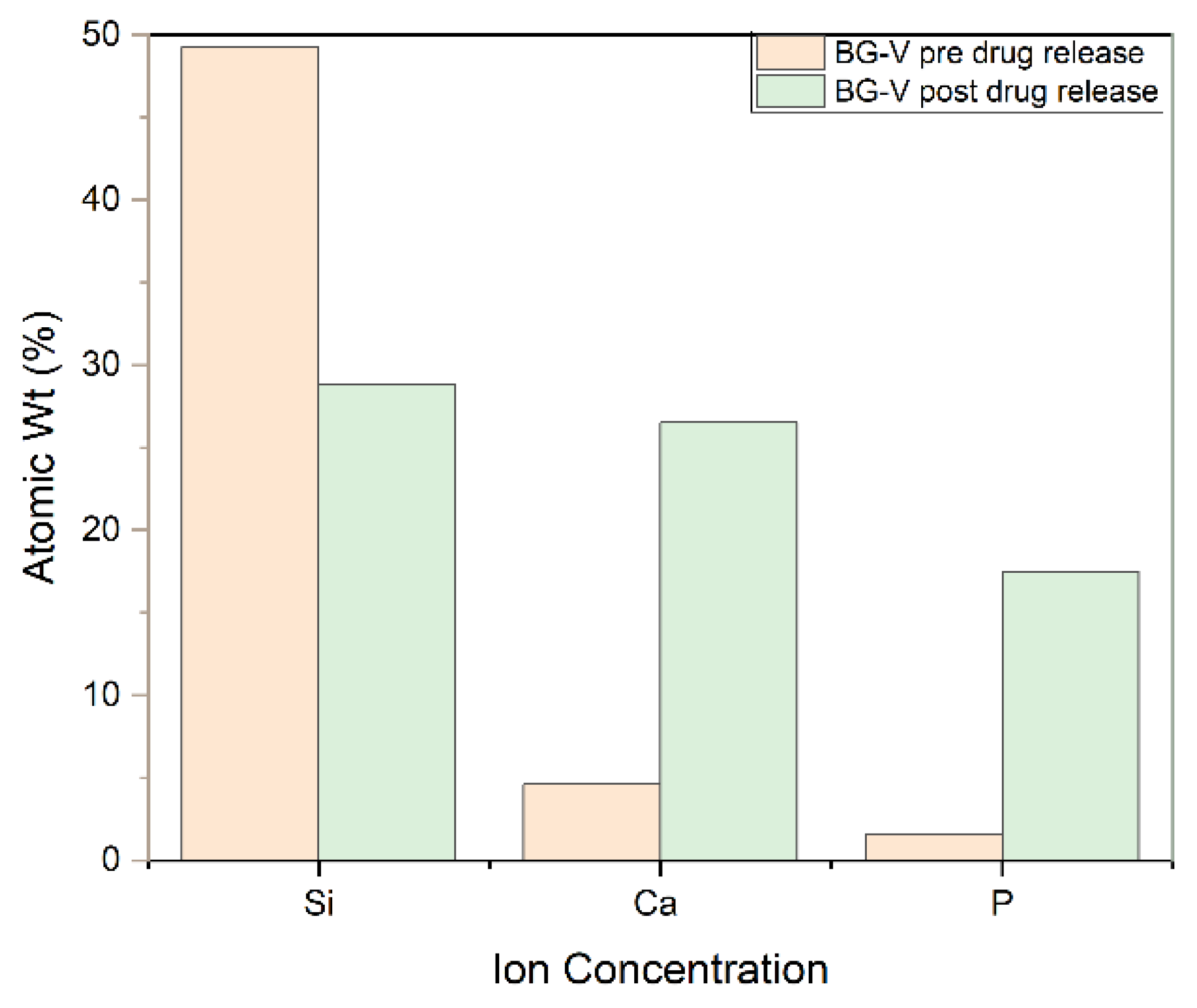

Figure 6 shows the SEM-EDS, which also confirms the development of HA on the surface of BG-V as a spectrum of atom weight percentage of Si, Ca and P went from 49.3%, 45% and 10% respectively to 28.5%, 26.5% and 17.5% after the drug release test was done in around 30 days. The ratio of Ca/P was observed to be 1.51 after immersion in PBS, the same ratio reported in other studies indicating the crystallization of apatite on the surface of the BG. The formation of a Ca/P ratio around 1.5 is particularly significant as it closely resembles the stoichiometric ratio found in natural bone minerals, suggesting that the bioactive glass has effectively facilitated the biomimetic mineralization process [

31,

32]. Furthermore, the SEM-EDS analysis revealed the presence of a newly formed crystalline layer on the surface of the BG-V after immersion in PBS, which indicates the bioactive glass’s capability to promote the deposition of HA. This is consistent with the XRD findings as it shows the crystalline layer that developed on the surface of BG-V after immersion in PBS and provides evidence for the ability of this material to deliver drugs and repair bone defects.

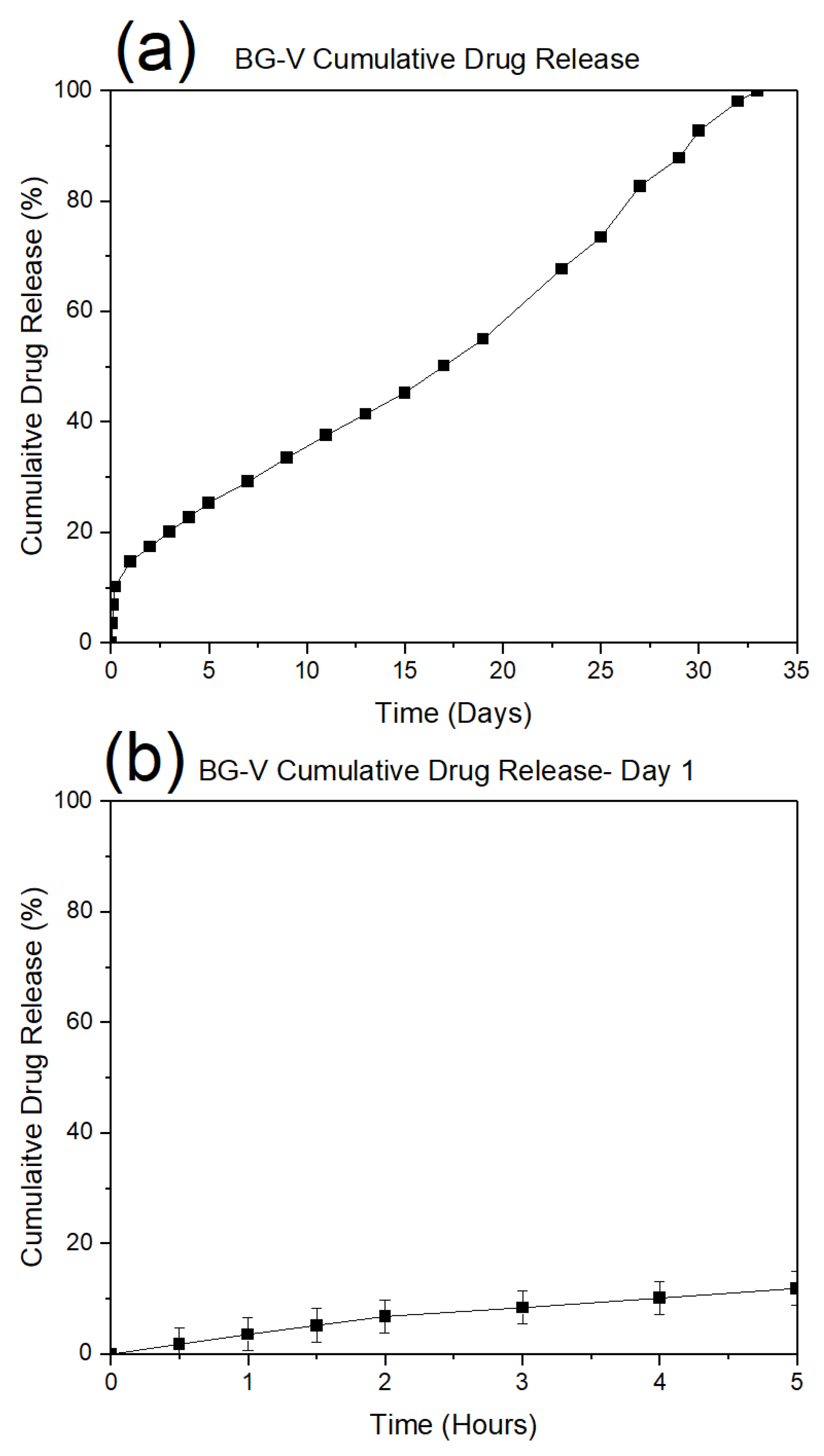

Figure 7 (a) shows the drug release observed on day 1, demonstrating a rapid initial release where approximately 20% of the vancomycin was released within the first few hours. This is followed by a plateau phase, indicating that the initial burst corresponds to the release of drug molecules adsorbed on the surface, which occurs within 4 to 5 hours.

Figure 7 (b) illustrates the cumulative vancomycin release over 23 days. While the initial phase mirrors the burst release as seen in

Figure 5 (a), the long-term profile reveals a more gradual and sustained release pattern. The near-linear progression of drug release beyond the first day suggests a controlled diffusion mechanism or gradual degradation of the bioactive glass matrix, facilitating continuous drug delivery. This extended-release profile is advantageous for maintaining therapeutic levels of vancomycin over extended periods, reducing the need for frequent dosing and enhancing the material’s suitability for applications in infection prevention and bone regeneration.

The data highlights the biphasic nature of drug release, where an initial rapid phase addresses acute therapeutic needs, followed by a sustained release phase that supports prolonged treatment efficacy. This release behaviour is characteristic of bioactive glass systems designed for localized drug delivery, reinforcing their potential in clinical applications.

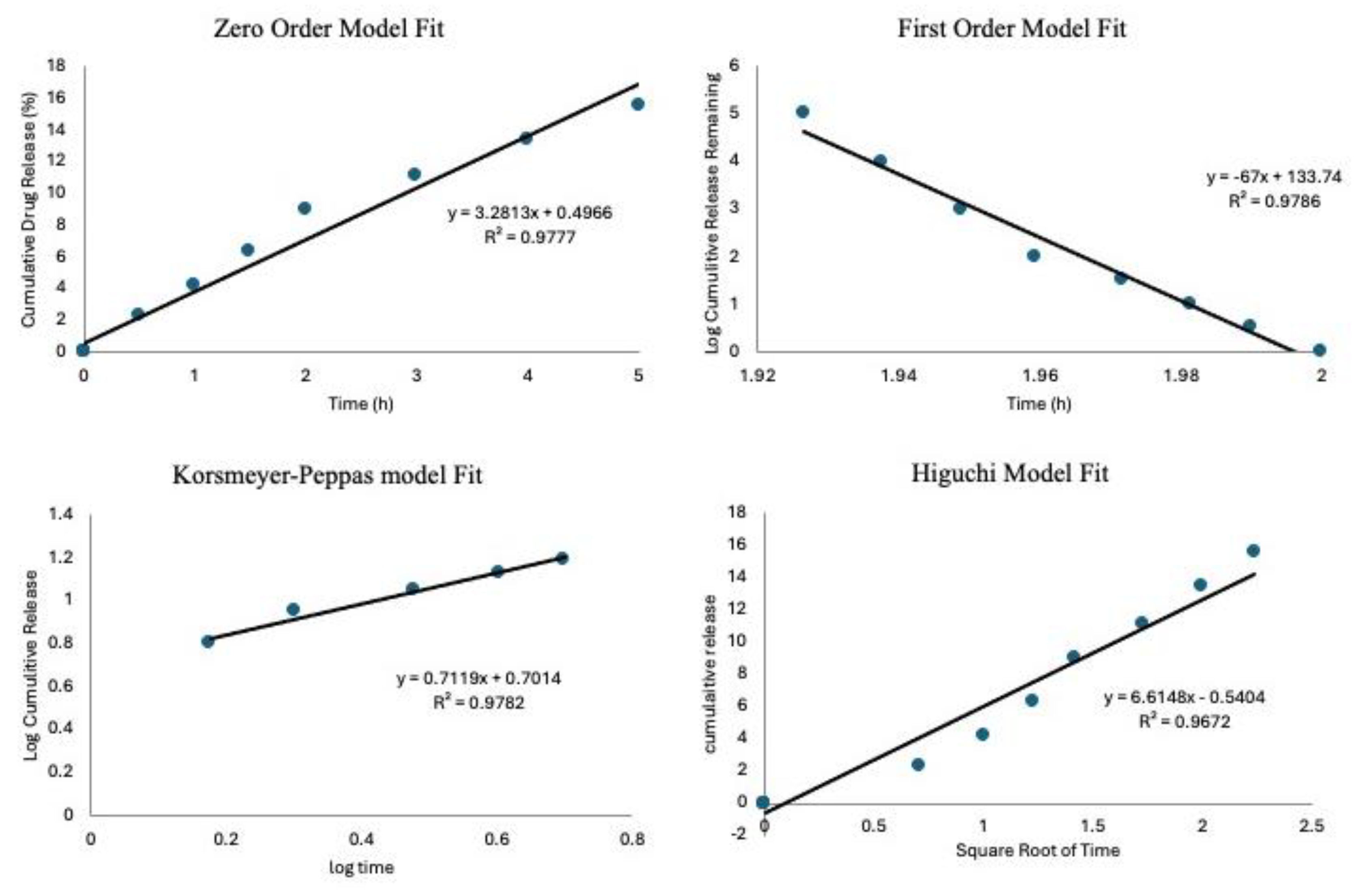

The drug release data were analyzed using kinetic models to describe the release mechanisms; this was done following previous studies [

35,

36]. To assess which model best fits the experimental data, the coefficient of determination (R

2) was calculated for each model. The results show an R

2 value of 0.977 for the Zero-Order model, while the First-Order model gave a negative R

2 of 0.978. The Higuchi and Korsmeyer-Peppas models had R

2 values of 0.967 and 0.978, respectively. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model had the highest R

2 value, suggesting that drug release is governed by a combination of diffusion and matrix erosion, which are characteristic of anomalous transport. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model is usually applied to describe drug release from porous materials, where the release mechanism does not follow simple diffusion [

37]. An important parameter in this model is the release exponent n, which provides insight into the drug release mechanism. In this study, the calculated n-value was 0.7119, indicating anomalous (non-Fickian) transport. This result implies that drug release is controlled by a combination of diffusion through the matrix and gradual erosion of the delivery system, aligning with findings from previous research on bioactive glass and polymeric drug delivery systems [

38].

Figure 8.

The drug release kinetics models to show goodness of fit for the zero-order model, first-order mode, Korsmeyer-Peppas mode and Higuchi model.

Figure 8.

The drug release kinetics models to show goodness of fit for the zero-order model, first-order mode, Korsmeyer-Peppas mode and Higuchi model.

Biofilm infections require consistent and high concentration when detected on prosthetics because of their extracellular matrix, which impairs drug penetration. Given that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for

S. aureus ranges from 2-16 μg/mL [

33], biofilm infections require higher concentration and exposure for a longer time, BG-V needs to maintain a much higher concentration for a long period to achieve complete eradication of biofilms. In this study, BG-V was able to maintain an average of around 229.5 μg/mL daily

in vitro which is below the toxic levels identified by Drouet et al. (2015) where they found a significant increase in human umbilical vein endothelial cell death from vancomycin concentrations of 2.5 mg/ml [

34]. By maintaining this level of drug release, BG-V ensures the complete elimination of biofilms while simultaneously dissolving to rebuild bone damaged by the infection.

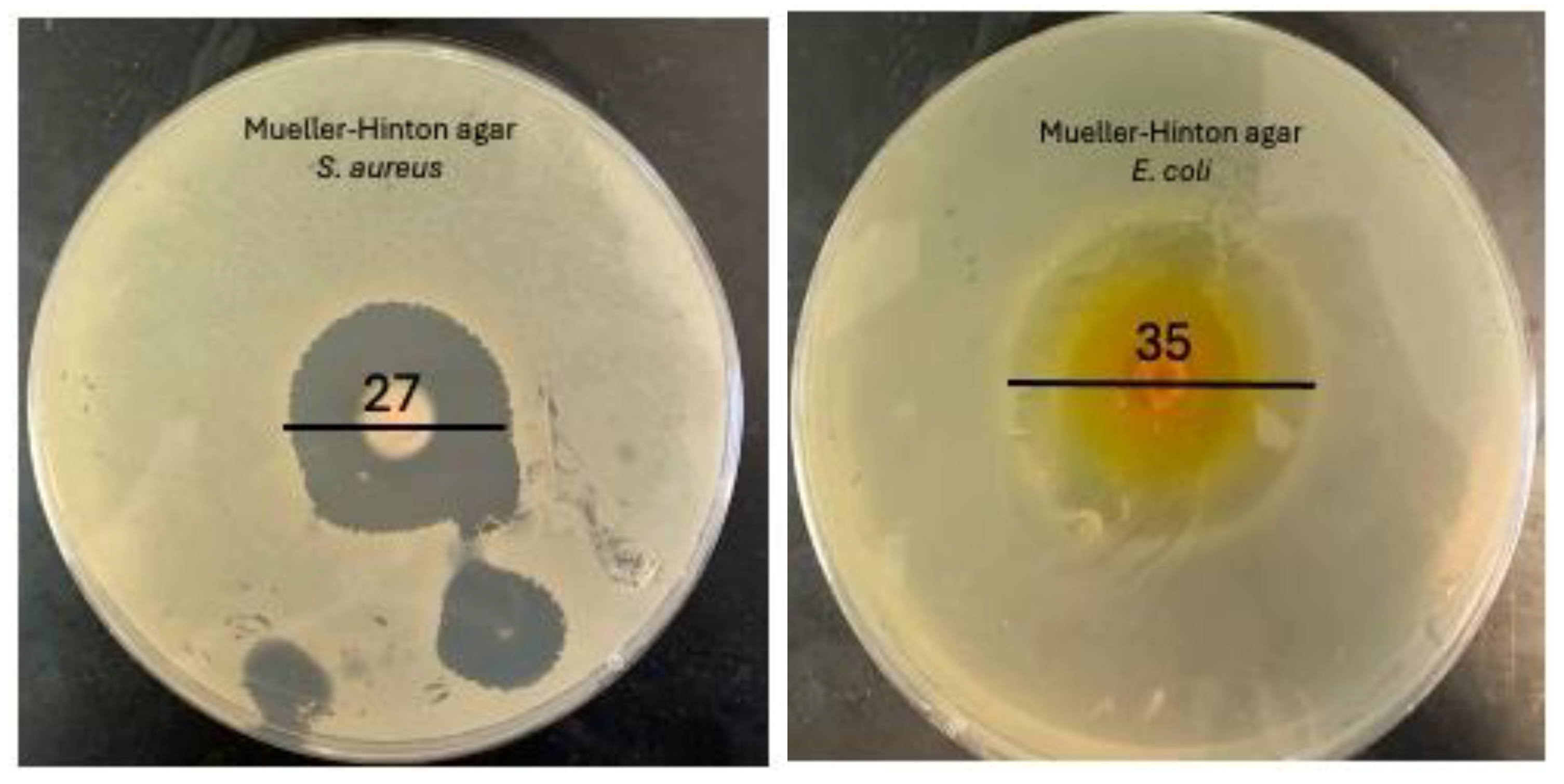

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted using the disc diffusion method. Sterilized BG-V samples were placed in wells within the agar to evaluate their antibacterial activity. The experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the results. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours, after which the zones of inhibition (ZOI) were measured [

39]. The disc diffusion test against

S. aureus on Mueller Hinton agar revealed a ZOI of 27 ± 0.2 mm, indicating a strong antibacterial effect. Similarly, the test against

E. coli showed a ZOI of 35 ± 0.4 mm, demonstrating a strong antibacterial effect against this gram-negative bacterium. The well-defined circular shape of the ZOI reflects consistent diffusion of vancomycin from the BG-V, suggesting homogeneity in drug loading and release from the BG-V matrix.

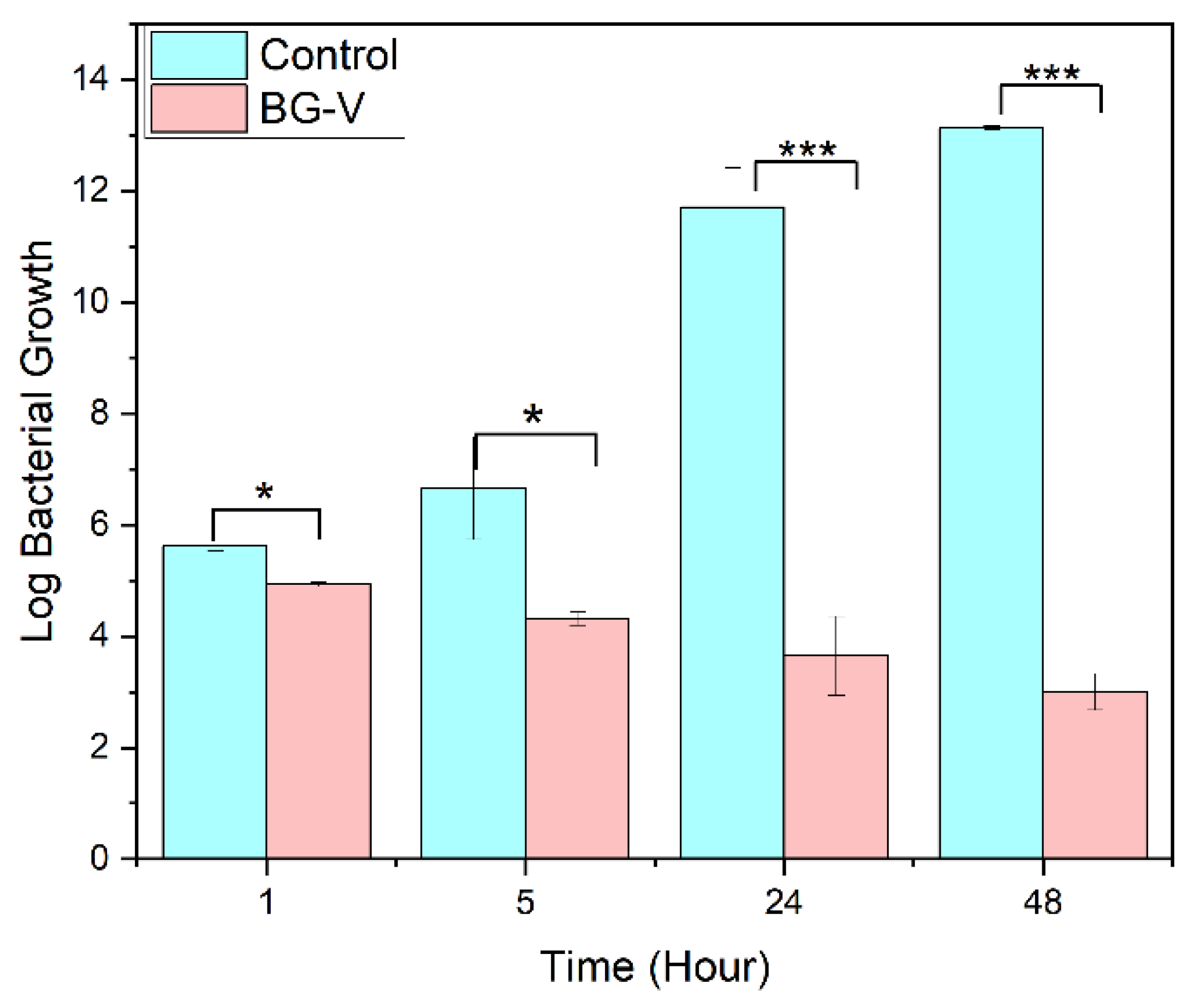

Figure 9 shows the antibacterial efficacy of BG-V was evaluated against S. aureus using a time-dependent bacterial killing assay. A bacterial culture of

S. aureus (10⁶ CFU/mL) was treated with BG-V, and samples were withdrawn at 1h, 5h, 24h, and 48h for plating. The results show a significant reduction in colony counts for BG-V compared to the control. At 24 hours, BG-V showed 1,400 colonies, compared to 5 trillion in control. By 48 hours, BG-V exhibited lower colony counts even lower colony count, showing the effectiveness of BG-V in bacteria killing. The means of BG-V and control were tested for significant differences between the two groups, t-test shows that after 1 hour there is no significant difference between the two. After 5, 24 and 48 hours there was a log reduction of 3.73, 9.55, and 10.176 respectively, meaning that there is a significant reduction in bacterial growth with the application of BG-V. This time-dependent antibacterial activity highlights the potential of vancomycin-loaded MBGs for localized antibiotic delivery in biomedical applications.

Figure 9.

Disc diffusion of BG-V against S. aurues. It has a zone of inhibition of 2.7± 0.2 cm and E.coli with a ZOI of 3.5± 0.4 .

Figure 9.

Disc diffusion of BG-V against S. aurues. It has a zone of inhibition of 2.7± 0.2 cm and E.coli with a ZOI of 3.5± 0.4 .

Figure 10.

Bacterial Killing assay comparing the control group to BG-V at 1 hour, 5 hours, 24 hours and 48 hours. The Figure shows the log bacterial growth of the control group compared to BG-V. The statistical difference is indicated by the * where * shows that the p>0.05 while *** shows that P>0.001.

Figure 10.

Bacterial Killing assay comparing the control group to BG-V at 1 hour, 5 hours, 24 hours and 48 hours. The Figure shows the log bacterial growth of the control group compared to BG-V. The statistical difference is indicated by the * where * shows that the p>0.05 while *** shows that P>0.001.