1. Introduction

Articular cartilage is an avascular tissue, and its capacity for self-repair is extremely limited once damaged. As cartilage lesions progress, they often lead to osteoarthritis (OA), which significantly impairs patients’ quality of life (QOL) [

1]. Bone marrow stimulation, osteochondral autograft transplantation, and autologous chondrocyte implantation have been used in clinical practice to treat cartilage injuries. However, these treatments have not been fully established, and the development of a minimally invasive technique that enables hyaline cartilage repair and maintains long-term tissue morphology and function is required [

2]. Among these treatments, bone marrow stimulation has been widely used because of its simplicity and minimal invasiveness. It is generally indicated for relatively small cartilage defects of less than 2 cm², and promotes cartilage repair by creating small holes in the subchondral bone at the site of injury, thereby inducing the migration and accumulation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into the site of injury [

3]. However, the repair tissue formed by bone marrow stimulation is primarily fibrocartilage, which is less mechanically durable than hyaline cartilage. Therefore, this can result in difficulties in maintaining joint function over the long term [

4]. Another clinical limitation is the difficulty of application to relatively large defects. One of the reasons for these issues is thought to be the insufficient chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs recruited into the repair tissue [

5]. Notably, MSCs are known to be present in hypoxic stem cell niches, and recent studies have reported that hypoxic conditions promote the chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs [

6]. In particular, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) has been shown to stabilize under hypoxic conditions and promote the expression of SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), a master regulator of chondrogenic differentiation, thereby contributing to chondrogenesis [

7]. However, most studies on hypoxia-induced chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs have been limited to the field of cartilage tissue engineering [

8], studies on cartilage repair through the use of hypoxic conditions in vivo remain limited. Recently, hypoxic responses via HIF-1α have attracted attention in the field of musculoskeletal research, and we have previously reported the protective effects of HIF-1α on articular cartilage and its role in muscle function in vivo [

9,

10,

11]. Based on this background, this study aimed to investigate the effects of hypoxic conditions on the quality of repair tissue in a rat osteochondral defect model. We hypothesized that hypoxic conditions promote the chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs, leading to the repair of hyaline cartilage-like tissue. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of hypoxic conditions on cartilage repair using an animal model and to contribute to the development of novel treatment for cartilage injuries in the future.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Hypoxic Conditions on Rat Knee Osteochondral Defect Model

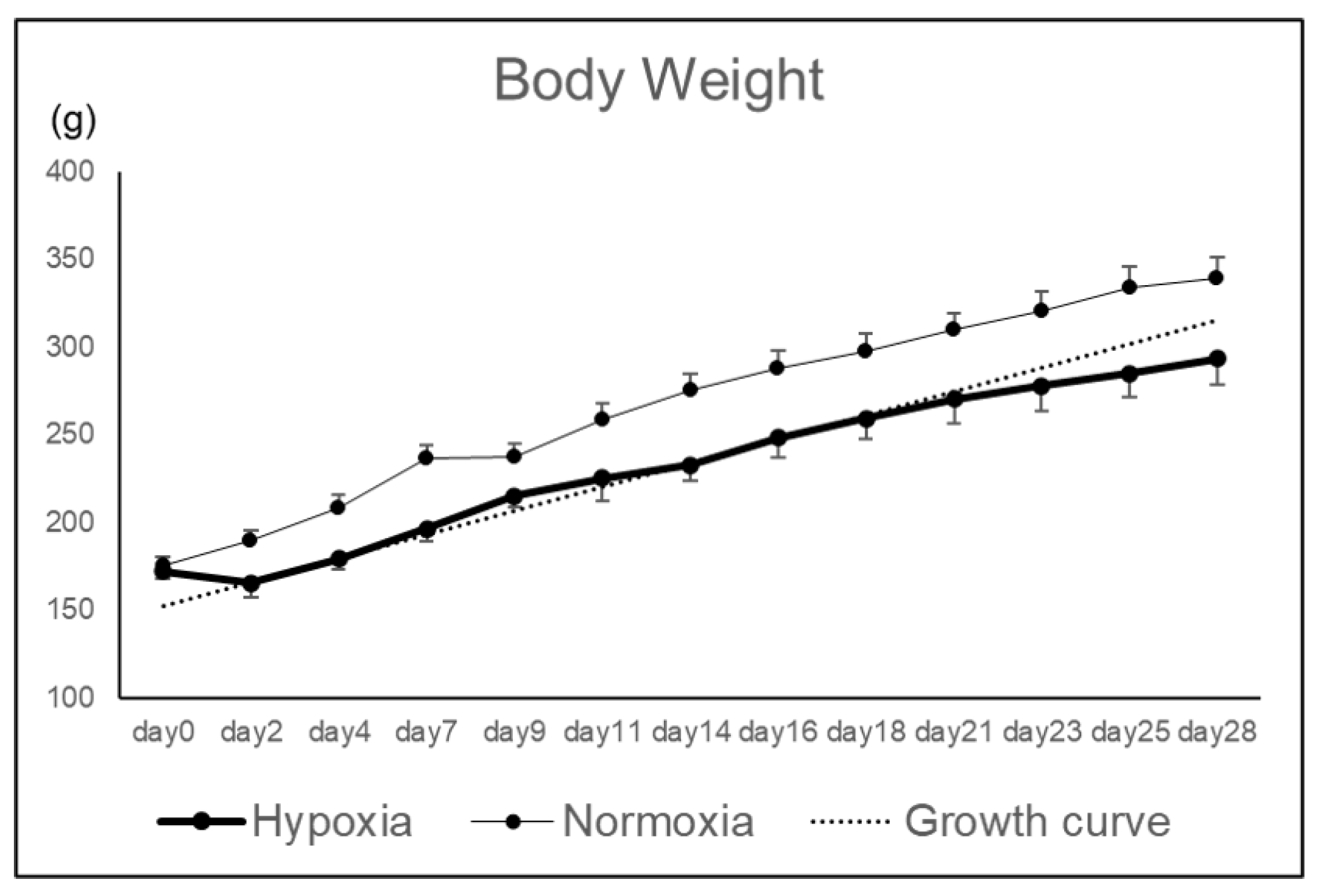

Rat knee osteochondral defect models were bred under hypoxic conditions (12%), and the effects of hypoxic conditions on the repair tissue were evaluated macroscopically and histologically. Body weight in Hypoxia group tended to decrease until postoperative day 4, but subsequently increased along the growth curve without deviation (

Figure 1).

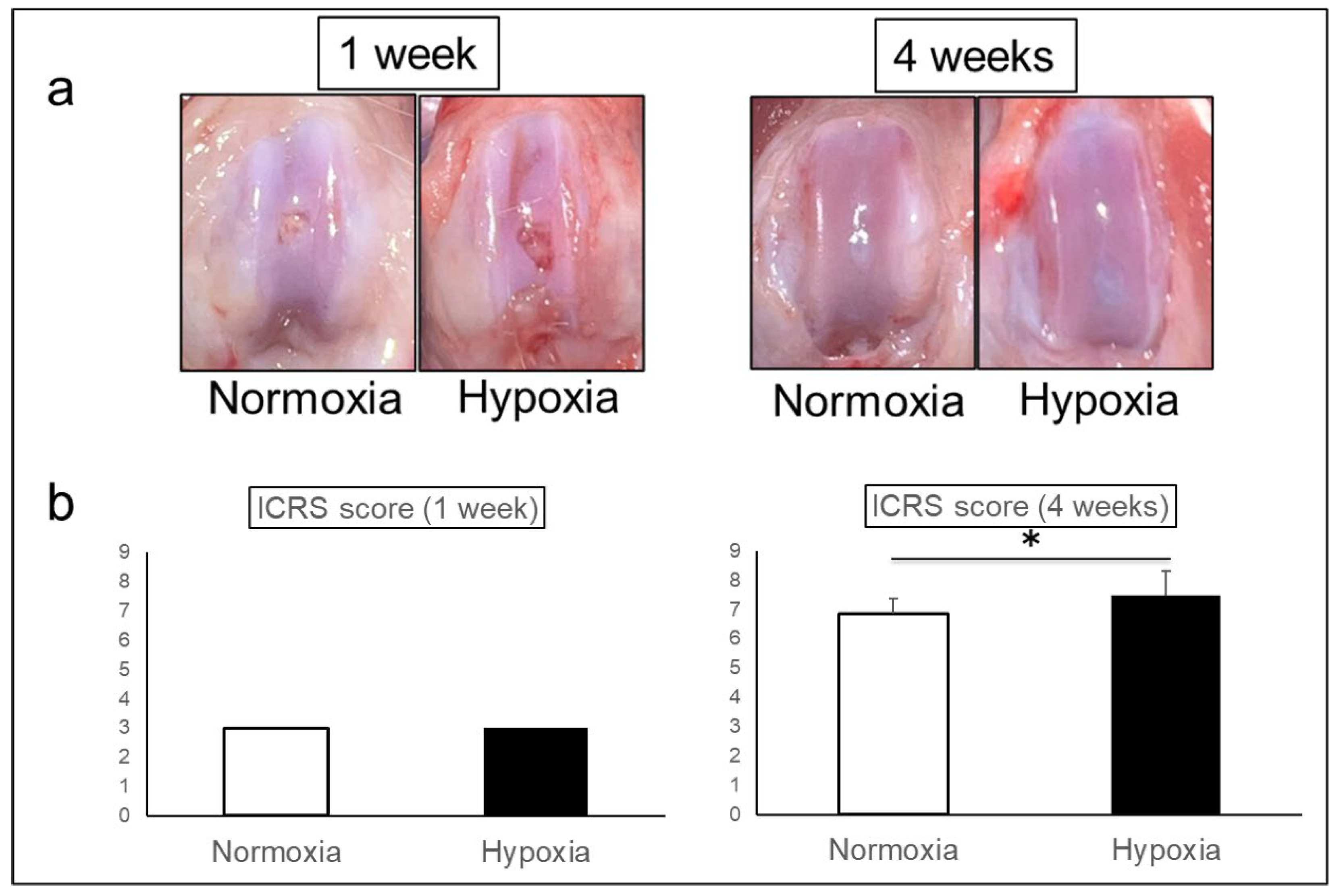

Macroscopically, both groups showed the defects with surface irregularity at 1 week. At 4 weeks, the defects were repaired without depression in both groups, but the surface of Hypoxia group was smoother than that of Normoxia group (

Figure 2a).

ICRS scores were 3.00 ± 0.00 in Normoxia group and 3.00 ± 0.00 in Hypoxia group at 1 week, however, 6.88 ± 0.50 in Normoxia group and 7.50 ± 0.82 in Hypoxia group at 4 weeks, indicating a significant improvement in Hypoxia group (p = 0.001) (

Figure 2b).

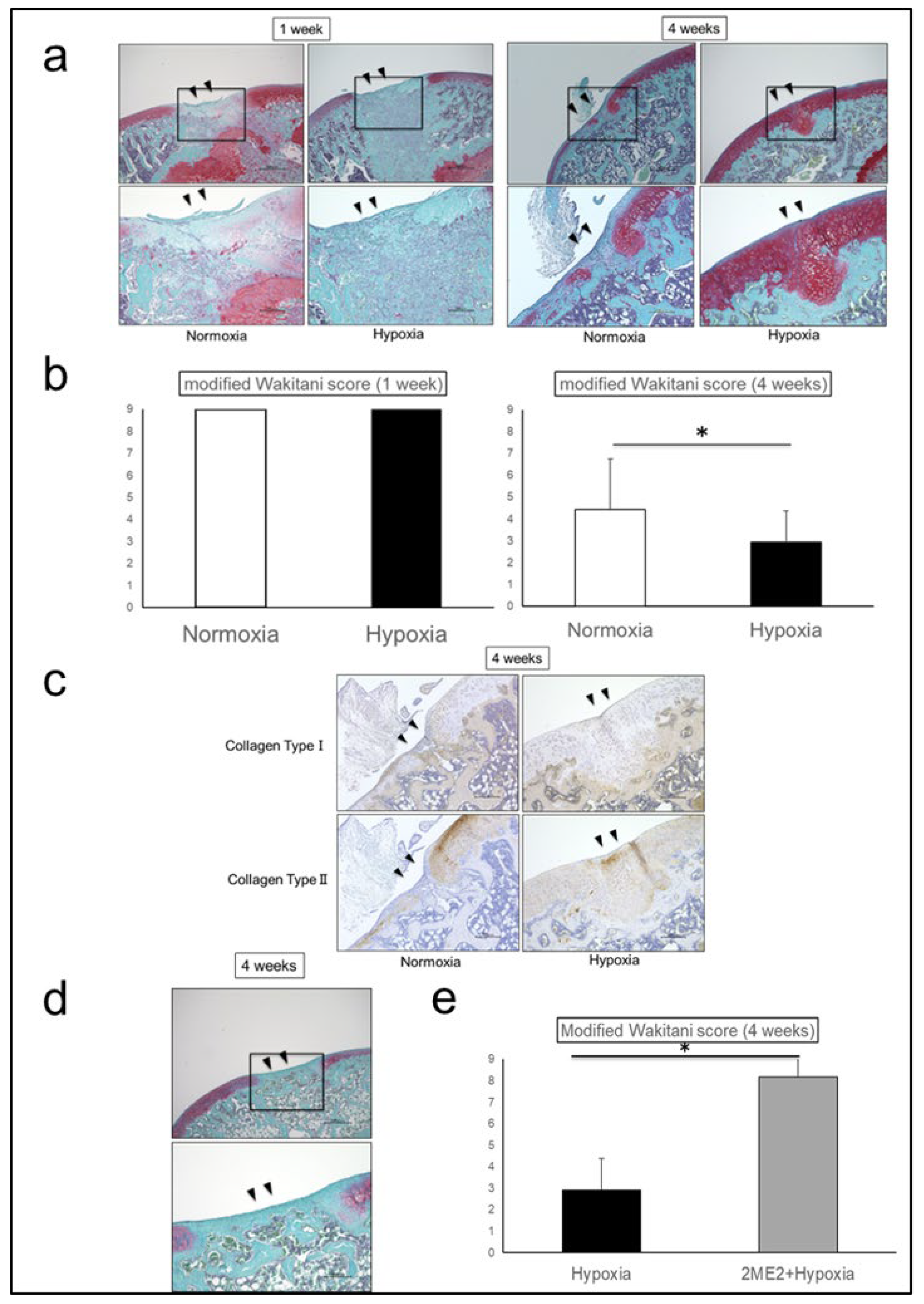

Histologically, Safranin O staining intensity of the repair tissue at 4 weeks was higher in Hypoxia group than in Normoxia group. The repair tissue was mainly fibrocartilage in Normoxia group, whereas hyaline cartilage-like tissue was observed in Hypoxia group (

Figure 3a). Modified Wakitani score was 9.00 ± 0.00 in Normoxia group and 9.00 ± 0.00 in Hypoxia group at 1 week, however, 4.44 ± 2.30 in Normoxia group and 2.94 ± 1.44 in Hypoxia group at 4 weeks, showing significantly promoted cartilage repair in Hypoxia group (p = 0.04) (

Figure 3b). The repair tissues in Hypoxia group exhibited decreased staining for Collagen Type I and increased staining for Collagen Type II, indicating that the repair tissue was similar to hyaline cartilage (

Figure 3c). When suppression experiments were conducted using 2-Methoxyestradiol (2-ME2) as a HIF-1α-specific inhibitor, in 2-ME2 + Hypoxia group at 4 weeks, Safranin O staining was absent, and the repair tissue was mainly fibrocartilage-like tissue (

Figure 3d). Modified Wakitani score was 8.17 ± 2.04 in 2-ME2 + Hypoxia group, significantly higher than that in Hypoxia group, indicating that cartilage repair was significantly suppressed by HIF-1α inhibition (p = 0.001) (

Figure 3e).

2.2. Effects of HIF-1α on the Repair Tissue

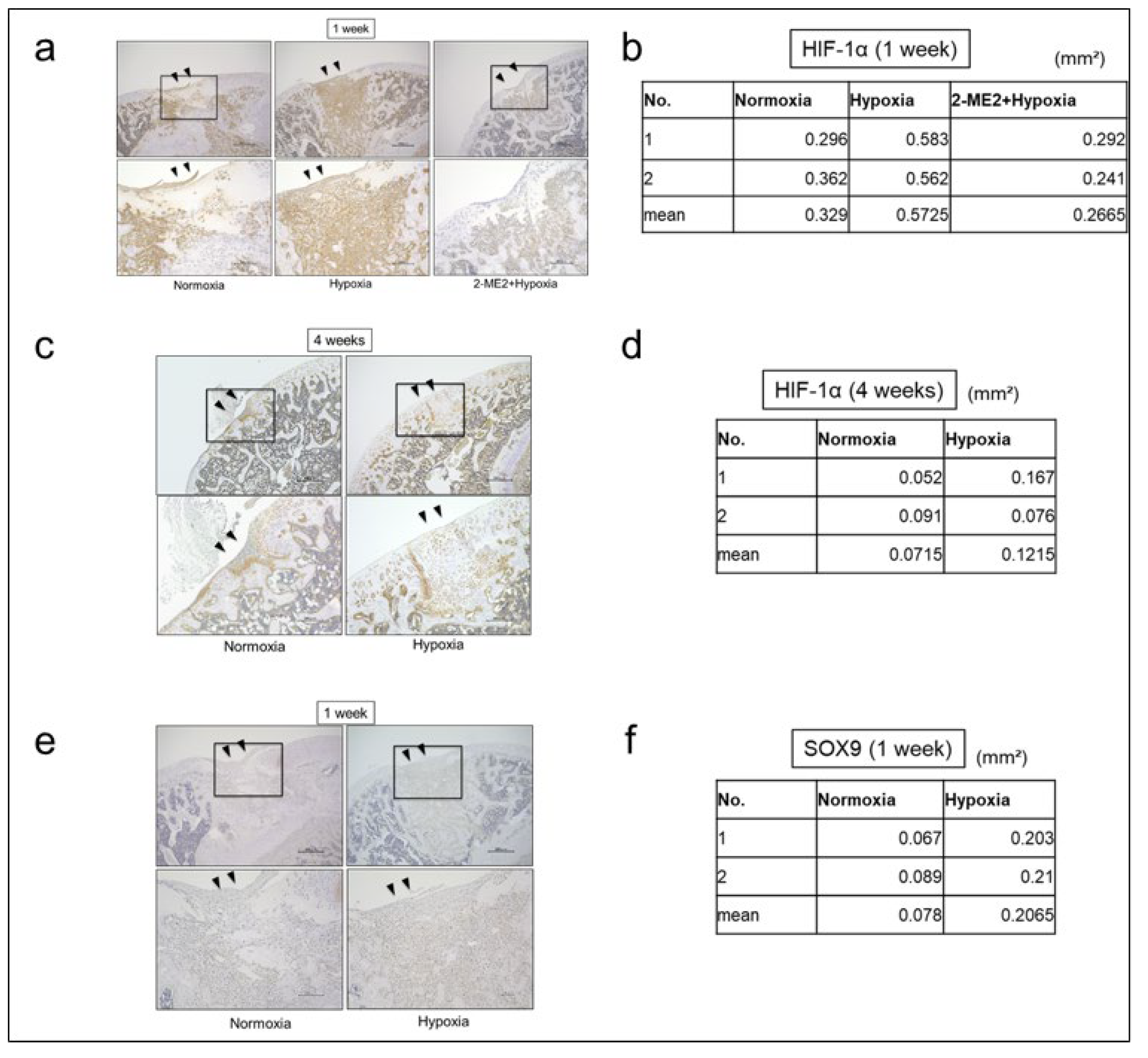

The effects of hypoxic conditions on the repair tissue were histologically evaluated using immunohistochemical staining for HIF-1α. The immunostaining area (mm²) of HIF-1α in the repair tissues was 0.33 ± 0.05 in Normoxia group and 0.57 ± 0.01 in Hypoxia group and 0.27 ± 0.03 in 2-ME2+Hypoxia group at 1 week, and 0.07 ± 0.03 in Normoxia group and 0.12 ± 0.06 in Hypoxia group at 4 weeks. At 1 week, the protein expression of HIF-1α in Hypoxia group was increased compared to Normoxia group (

Figure 4a, b). However, at 4 weeks, the protein expression of HIF-1α in both Normoxia and Hypoxia groups was decreased (

Figure 4c, d). The immunostaining area (mm²) of SOX9 in the repair tissues was 0.08 ± 0.01 in Normoxia group and 0.21 ± 0.01 in Hypoxia group, and the protein expression of SOX9 in Hypoxia group was also increased (

Figure 4e, f). Furthermore, at 1 week, we observed that the protein expression of HIF-1α in the repair tissues was suppressed in 2-ME2+Hypoxia group compared to Hypoxia group (

Figure 4a, b).

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of hypoxic conditions on the repair tissue in a rat knee osteochondral defect model. The results demonstrated that at 4 weeks postoperatively, Hypoxia group exhibited repair tissue that was more similar to hyaline cartilage compared to Normoxia group. Furthermore, at 1 week postoperatively, which corresponds to the early phase after surgery, the protein expression of HIF-1α and SOX9 in the repair tissue was increased in Hypoxia group. In addition, the repair-promoting effect of hypoxic conditions was suppressed by HIF-1α inhibitor (2-ME2), suggesting that hypoxic conditions may promote the chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs via HIF-1α induction, thereby contributing to the qualitative improvement of the repair tissue.

Articular cartilage is an avascular tissue with extremely limited self-repair capacity once injured. Yoshioka et al. reported that, in the knee joint at 6 weeks rat, a V-shaped cartilage defect with a width of 0.7 mm could be repaired with hyaline cartilage-like tissue, whereas 1.5 mm defect was predominantly repaired with fibrocartilage-like tissue [

12]. Thus, while small defects may have some potential for spontaneous repair, the healing of larger defects remains challenging.

Bone marrow stimulation is a treatment that promotes cartilage repair by creating small holes in the subchondral bone at the site of injury to induce bleeding from the bone marrow, leading to the formation of a marrow clot containing MSCs, which serves as the basis for inducing cartilage repair. However, the repair tissue is generally fibrocartilage, which has inferior mechanical properties compared to hyaline cartilage, and may eventually lead to secondary osteoarthritis (OA) in the long term [

3]. One of the possible reasons for this qualitative problem is the insufficient chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs during the repair process [

4,

5]. Recently, the application of hypoxia-responsive mechanisms in cartilage repair has garnered significant attention. Articular cartilage is physiologically under hypoxic conditions of 1-8% [

13], and many studies have reported the effects of hypoxic conditions on chondrocytes and the chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs. Nevo et al. were the first to demonstrate that hypoxic conditions promote the differentiation of embryonic chick chondrocytes [

14]. Henrionnet et al. reported that hypoxic conditions is a critical environmental factor that promotes chondrogenic differentiation while inhibiting osteogenic differentiation of MSCs [

15]. Semenza et al. identified hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) as a key regulator of hypoxic responses, demonstrating that HIF-1α is stabilized under hypoxic conditions by escaping degradation via prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) and functions as a transcription factor [

16,

17,

18]. Amarilio et al. demonstrated that HIF-1α directly binds to the promoter region of SOX9 and promotes chondrogenic differentiation [

7], and many reports have shown that hypoxia enhances the chondrogenic differentiation potential of MSCs in vitro. For example, Adesida et al. found that culturing human bone marrow-derived MSCs under hypoxic conditions upregulated HIF-1α expression and increased the expression of chondrogenic markers such as SOX9, ACAN, and COL2A1 [

19]. Duval et al. demonstrated that hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs exhibit enhanced extracellular matrix production [

20], Li et al. revealed that hypoxic conditions promote chondrogenic differentiation while suppressing hypertrophic differentiation of MSCs [

21], and Shimomura et al. showed similar effects in induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells [

22]. Although these findings have been mainly based on in vitro studies in the field of cartilage tissue engineering, this study provides important in vivo evidence that hypoxic conditions promote chondrogenic differentiation within the repair tissue of osteochondral defects.

In this study, we adopted hypoxic conditions with an oxygen concentration of 12%, which has been previously confirmed to be safe and effective in the musculoskeletal field [

9,

10]. In this environment, 1.0 mm-diameter osteochondral defect models were created, and histological evaluation was performed at 4 weeks postoperatively. As a result, Hypoxia group exhibited increasingly Safranin O staining, and increased the protein expression of Collagen Type II, decreased the protein expression of Collagen Type I, indicating the formation of tissue structure closer to hyaline cartilage. Furthermore, at 1 week postoperatively, the protein expression of HIF-1α and SOX9 was increased in Hypoxia group. Inhibition of HIF-1α with 2-ME2 led to the suppression of these increased expressions, resulting in the formation of fibrocartilage-like tissue, suggesting that HIF-1α plays a pivotal role in promoting cartilage repair under hypoxic conditions.

HIF-1α forms a complex with ARNT (HIF-1β) in the cytoplasm and subsequently enters the nucleus, where it directly promotes the transcription of SOX9 by binding to the hypoxia-responsive element located in the promoter region of the SOX9 gene. In addition, it is also known that HIF-1α regulates SOX9 expression by activating the TGF-β/Smad, BMP/Smad, and Hedgehog pathways, while inhibiting the Notch and Wnt/β-catenin pathways [

23]. These pathways interact with each other, and SOX9, in conjunction with SOX5 and SOX6, forms the SOX trio to promote transcription of the ACAN and COL2A1 genes. Yan et al. demonstrated that the TGF-β/Smad pathway is activated via HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions [

24], while Tan et al. demonstrated the presence of crosstalk between HIF-1α and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [

25]. Based on these findings, in this study, it is highly likely that HIF-1α induced in MSCs within the repair tissue under hypoxic conditions directly or indirectly promoted SOX9 transcriptional activity, thereby contributing to the formation of hyaline cartilage-like repair tissue.

This study has several limitations. First, the experiment was conducted under a single hypoxic condition, and the effects of different oxygen concentrations were not evaluated. Second, the evaluation period was limited to the short term, with assessments performed only up to 4 weeks after surgery. Third, HIF-1α inhibitor (2-ME2) used in this study does not act specifically on the repair tissue, and the potential effects of the inhibitor itself on the repair tissue remain unclear. Finally, the downstream signaling pathways of HIF-1α in MSCs within the repair tissue have not been fully elucidated.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

A total of forty-eight 6-week-old male Wistar rats (Shimizu Laboratory Suppliers, Kyoto, Japan) were used in this study. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of our institution (Code: M2023-286) and conducted in accordance with its ethical guidelines.

4.2. Creation of Rat Knee Osteochondral Defect Model

Anesthesia induction was performed by administering 0.375 mg/kg medetomidine, 2.0 mg/kg midazolam, and 2.5 mg/kg butorphanol intraperitoneally to the rats. An anterior straight longitudinal incision was made on the left knee joint, and the knee was exposed using a medial parapatellar approach. The patella was dislocated laterally to expose the femoral trochlear groove. According to the method reported by Yoshioka et al., which is known to create an osteochondral defect that does not allow spontaneous repair with hyaline cartilage, an osteochondral defect (1.0 mm in diameter and 2.0 mm in depth) reaching the subchondral bone was created in the femoral trochlear groove using a Kirschner wire (Diameter: 1.0 mm, ISO Medical Advance, Osaka, Japan), and bleeding from the bone marrow was confirmed [

12]. After reduction of the patella, the joint capsule and skin were sutured using 5-0 nylon sutures to complete the surgery.

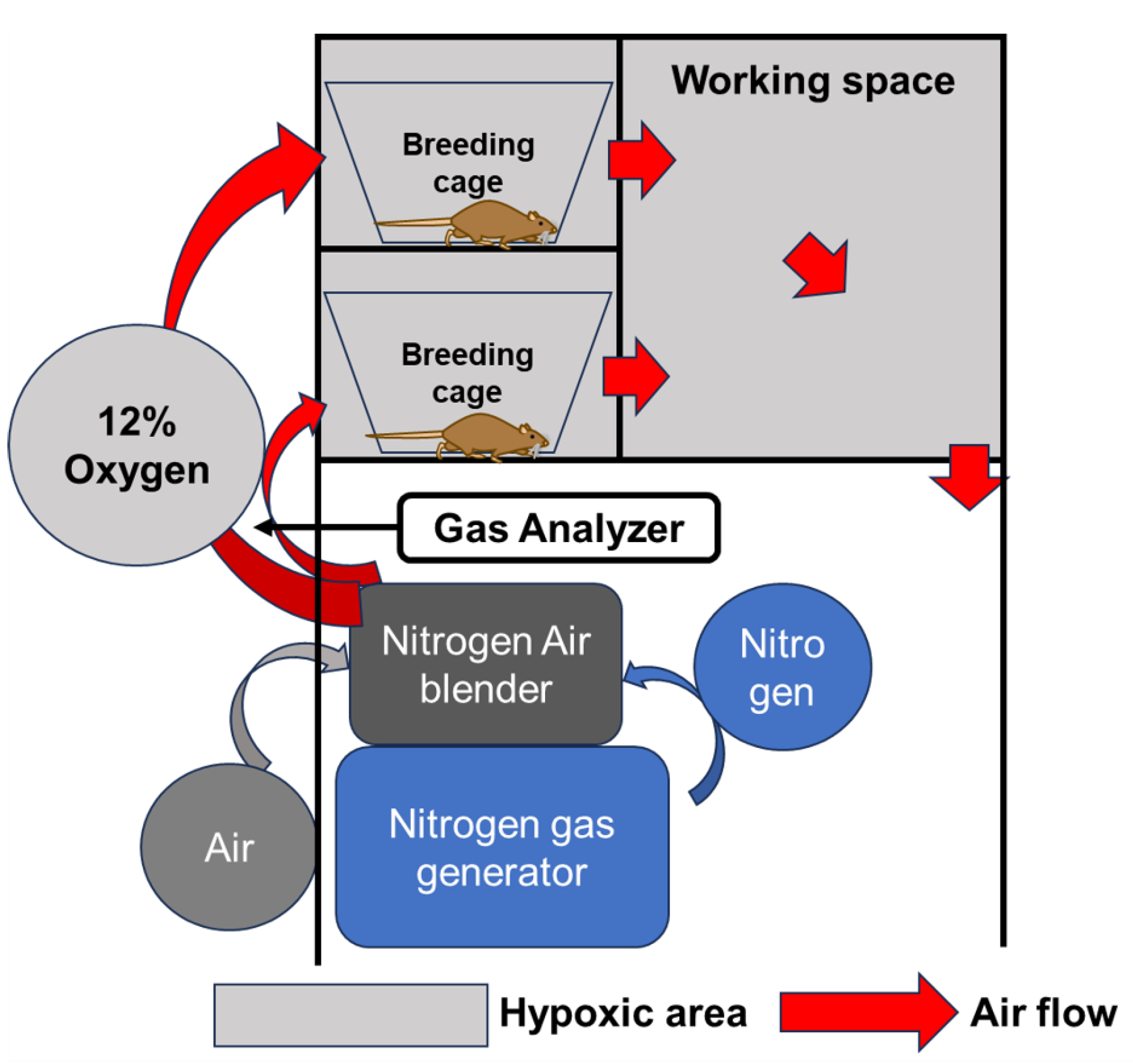

4.3. Breeding in a Hypoxic Chamber

Hypoxic conditions were established using a chamber with adjustable oxygen concentration (Natsume Seisakusho Co., Ltd. Wakenyaku Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) as equipment capable of breeding under hypoxic conditions. Nitrogen supplied from a gas generator was mixed with ambient air at a desired ratio using an air blender to reduce the oxygen concentration. This hypoxic air was circulated through the breeding cage and workplace to maintain hypoxic conditions in the chamber. The oxygen concentration in any given area of the chamber can be measured using a gas analyzer, and the oxygen concentration in the chamber can be adjusted at will within the range of 4-20% by adjusting the air blender (

Figure 5). Based on previous reports of animal models, the oxygen concentration was set at 12% in the hypoxic conditions [

9,

10].

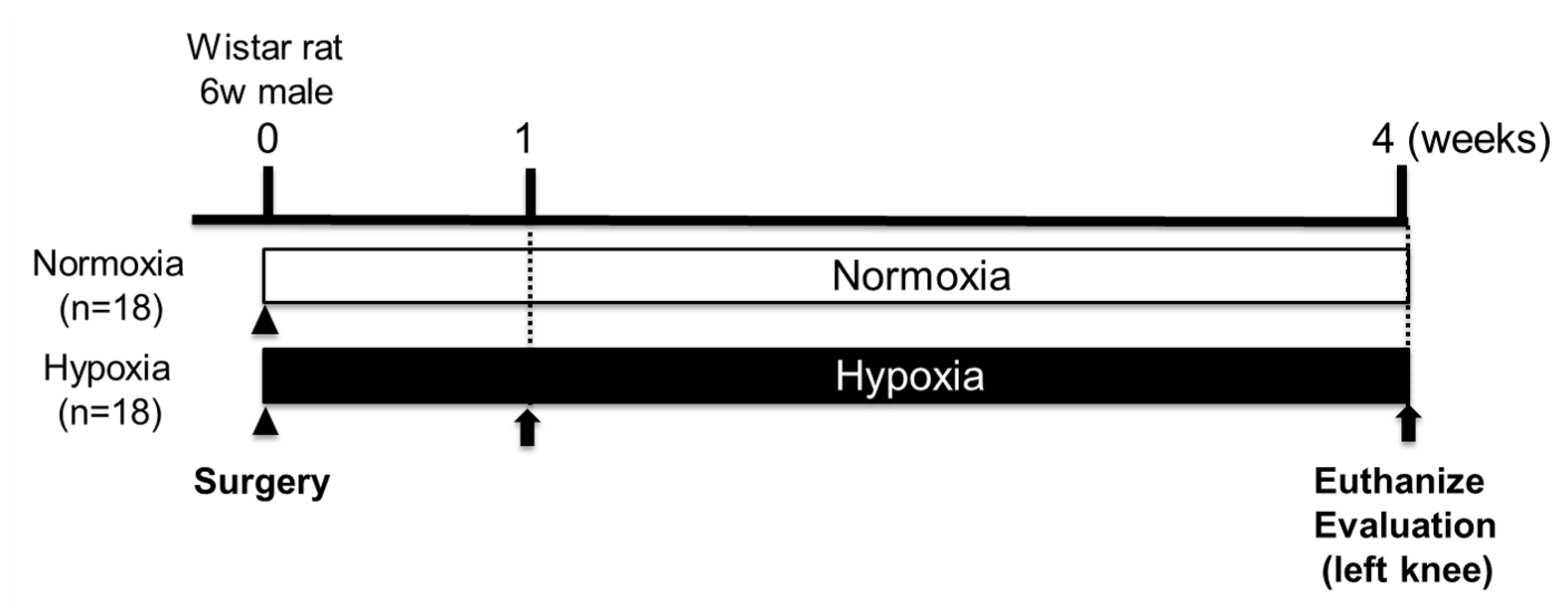

4.4. Effects of Hypoxic Conditions on Rat Knee Osteochondral Defect Model

Postoperatively, rats were divided into Normoxia group (n=18, 21% oxygen) and Hypoxia group (n=18, 12% oxygen). At 1 and 4 weeks after surgery (1 week: n=2 per group, 4 weeks: n=16 per group), rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital, and their left femur was surgically removed (

Figure 6). Both groups were bred under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Body weight of both groups was measured over time until 4 weeks postoperatively (n=16).

4.5. HIF-1α Inhibitor Treatment

To evaluate the effects of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions, inhibition of HIF-1α was performed. 2-ME2(Selleck, Tokyo, Japan) was used as a HIF-1α-specific inhibitor. After creating an osteochondral defect in the left femoral trochlear groove of rats (n=8), rats were bred under 12% hypoxic conditions, and 2-ME2 was intra-articularly administered three times per week starting from the day after surgery, according to previous reports, at an appropriate concentration (100 μM) [

26]. The animals were defined as 2-ME2 + Hypoxia group. Their left femur was surgically removed at 1 week (n=2) and 4 weeks (n=6) after surgery.

4.6. Macroscopic Evaluation

Macroscopic evaluation of the osteochondral defects in the femoral trochlear groove was performed at 1 week (n=2 per group) and 4 weeks (n=16 per group) postoperatively in Normoxia and Hypoxia groups. The repair tissue was evaluated using the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) scoring system [

27]. In this study, to focus on the quality of the repair tissue, the item “Integration to border zone” was excluded from the evaluation, and the scoring was performed on an 8-point scale.

4.7. Histological Evaluation

After macroscopic evaluation, samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako, Osaka, Japan), decalcified in 20% EDTA, and embedded in paraffin. Sagittal sections (6 μm thick) were prepared from the created defect site and stained with Safranin O. Histological evaluation of the repair tissue in the femoral trochlear groove was performed under a microscope at 1 week (n=2 per group) and 4 weeks (n=16 per group) postoperatively in Normoxia and Hypoxia groups. The repair tissue was evaluated using the Modified Wakitani score [

28]. In addition, the effect of HIF-1α was evaluated by comparing the Hypoxia group (n=16) with the 2-ME2+Hypoxia group (n=6) at 4 weeks postoperatively. In this study, to focus on the quality of the repair tissue, the item “Integration of implant with adjacent host cartilage” was excluded from the evaluation, and scoring was performed on a 9-point scale.

4.8. Immunohistochemical Analysis

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of HIF-1α (1 week: n=2 per group; 4 weeks: Normoxia and Hypoxia groups, n=2), SOX9 (1 week: Normoxia and Hypoxia groups, n=2), Collagen Type I, and Collagen Type II (4 weeks: Normoxia and Hypoxia groups, n=1). Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated through graded ethanol, and washed with running water and PBS. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in 3% H2O2 methanol solution for 15 minutes. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-HIF-1α antibody (ab114977; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:100 dilution), mouse monoclonal anti-SOX9 antibody (ab76997; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:1200 dilution), rabbit polyclonal anti-Collagen Type I antibody (ab34710; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:40 dilution), and mouse monoclonal anti-Collagen Type II antibody (F-57; Kyowa Pharma Chemical Co., Toyama, Japan; 1:100 dilution). After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with Histofine® Simple Stain Rat MAX-PO (NICHIREI BIOSCIENCES INC., Tokyo, Japan) at 25°C for 30 minutes. Immunostaining was detected by DAB staining, and Mayer’s hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. The stained sections were observed under a light microscope. To quantify the expression of HIF-1α and SOX9, images were captured at 100x magnification in TIFF format, and the stained area was measured using ImageJ software.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution, and non-normal distributions were confirmed in all groups (p < 0.05). Comparisons between two groups were performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that applying a 12% hypoxic condition to a rat osteochondral defect model may increase HIF-1α expression in MSCs within the repair tissue, promote their chondrogenic differentiation, thereby contributing to the formation of hyaline cartilage-like tissue. Bone marrow stimulation with hypoxic conditions may enhance the repair effect on articular cartilage injuries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N., and S.N.; methodology, A.I. and K.T.; software, K.N. and A.I.; validation, Y.A., A.I. and T.K.; formal analysis, K.N., R.C., K.S., and K.H; investigation, K.N., Y.F., and R.C.; resources, Y.F. and S.N.; data curation, K.N., A.I., and S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.N.; writing—review and editing, K.N., A.I., and Y.A.; visualization, K.N.; supervision, O.M. and K.T.; project administration, A.I., S.N., and Y.A.; funding acquisition, K.N., S.N., Y.A., A.I., and K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number: JP21H03295).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan (protocol code no. M2023-286 and date of approval: 01/04/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberthal J, Sambamurthy N, Scanzello CR. Inflammation in joint injury and post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015, 23, 1825–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasson M, Fernandes LM, Solomon H, Pepper T, Huffman NL, Pucha SA, Bariteau JT, Kaiser JM, Patel JM. Considering the Cellular Landscape in Marrow Stimulation Techniques for Cartilage Repair. Cells Tissues Organs 2024, 213, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armiento AR, Alini M, Stoddart MJ. Articular fibrocartilage - Why does hyaline cartilage fail to repair? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 146, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li M, Yin H, Yan Z, Li H, Wu J, Wang Y, Wei F, Tian G, Ning C, Li H, Gao C, Fu L, Jiang S, Chen M, Sui X, Liu S, Chen Z, Guo Q. The immune microenvironment in cartilage injury and repair. Acta Biomater. 2022, 140, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia JP, Avila FR, Torres RA, Maita KC, Eldaly AS, Rinker BD, Zubair AC, Forte AJ, Sarabia-Estrada R. Hypoxia-preconditioning of human adipose-derived stem cells enhances cellular proliferation and angiogenesis: A systematic review. J Clin Transl. Res. 2022, 8, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Amarilio R, Viukov SV, Sharir A, Eshkar-Oren I, Johnson RS, Zelzer E. HIF1alpha regulation of Sox9 is necessary to maintain differentiation of hypoxic prechondrogenic cells during early skeletogenesis. Development 2007, 134, 3917–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheem DK, Jell G, Gentleman E. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α in Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2020, 26, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura S, Inoue H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, Fujii Y, Kishida T, Shin-Ya M, Ichimaru S, Tsuchida S, Mazda O, Takahashi K. Mechanical stimulation of chondrocytes regulates HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions. Tissue Cell 2021, 71, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada Y, Arai Y, Toyama S, Inoue A, Nakagawa S, Fujii Y, Kaihara K, Cha R, Mazda O, Takahashi K. Hypoxia with or without Treadmill Exercises Affects Slow-Twitch Muscle Atrophy and Joint Destruction in a Rat Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 9761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha R, Nakagawa S, Arai Y, Inoue A, Okubo N, Fujii Y, Kaihara K, Nakamura K, Kishida T, Mazda O, Takahashi K. Intermittent hypoxic stimulation promotes efficient expression of Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and exerts a chondroprotective effect in an animal osteoarthritis model. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka M, Kubo T, Coutts RD, Hirasawa Y. Differences in the repair process of longitudinal and transverse injuries of cartilage in the rat knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998, 6, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiaer, T.; Grønlund, J.; Sørensen, K.H. Subchondral pO2, pCO2, pressure, pH, and lactate in human osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Nevo Z, Beit-Or A, Eilam Y. Slowing down aging of cultured embryonal chick chondrocytes by maintenance under lowered oxygen tension. Mech Ageing Dev. 1988, 45, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrionnet C, Liang G, Roeder E, Dossot M, Wang H, Magdalou J, Gillet P, Pinzano A. Hypoxia for Mesenchymal Stem Cell Expansion and Differentiation: The Best Way for Enhancing TGFß-Induced Chondrogenesis and Preventing Calcifications in Alginate Beads. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017, 23, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza GL, Wang GL. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992, 12, 5447–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1995, 270, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, von Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001, 292, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesida AB, Mulet-Sierra A, Jomha NM. Hypoxia mediated isolation and expansion enhances the chondrogenic capacity of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval E, Baugé C, Andriamanalijaona R, Bénateau H, Leclercq S, Dutoit S, Poulain L, Galéra P, Boumédiene K. Molecular mechanism of hypoxia-induced chondrogenesis and its application in in vivo cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2012, 33, 6042–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li DX, Ma Z, Szojka AR, Lan X, Kunze M, Mulet-Sierra A, Westover L, Adesida AB. Non-hypertrophic chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells through mechano-hypoxia programing. J Tissue Eng. 2023, 14, 20417314231172574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomura S, Inoue H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, Fujii Y, Kishida T, Shin-Ya M, Ichimaru S, Tsuchida S, Mazda O, Kubo T. Hypoxia promotes differentiation of pure cartilage from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Med Rep. 2022, 26, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang X, Tian S, Fan L, Niu R, Yan M, Chen S, Zheng M, Zhang S. Integrated regulation of chondrogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells and differentiation of cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Wang S, Zhang W, Zhu Y, Fan Z, Huang Y, Li F, Yang R. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells facilitate diabetic wound healing through the restoration of epidermal cell autophagy via the HIF-1α/TGF-β1/SMAD pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022, 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan Z, Zhou B, Zheng J, Huang Y, Zeng H, Xue L, Wang D. Lithium and Copper Induce the Osteogenesis-Angiogenesis Coupling of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells via Crosstalk between Canonical Wnt and HIF-1α Signaling Pathways. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 6662164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelse K, Pfander D, Obier S, Knaup KX, Wiesener M, Hennig FF, Swoboda B. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha in the integrity of articular cartilage in murine knee joints. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008, 10, R111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Borne MP, Raijmakers NJ, Vanlauwe J, Victor J, de Jong SN, Bellemans J, Saris DB. International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) and Oswestry macroscopic cartilage evaluation scores validated for use in Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) and microfracture. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2007, 15, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Huang YC, Gertzman AA, Xie L, Nizkorodov A, Hyzy SL, Truncale K, Guldberg RE, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Endogenous regeneration of critical-size chondral defects in immunocompromised rat xiphoid cartilage using decellularized human bone matrix scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012, 18, 2332–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).