1. Introduction

Recycling of residues from both agricultural and industrial sections are so attractive nowadays due to increasing in environmental concerns. In general, for agricultural sections most residues are lignocellulosic materials, which are considered the future of a non-food material. They mainly consist of 3 natural polymers including lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose. Among those, cellulose is perhaps the largest presence in the form of microfibrils, and is well-known for its turnover capacity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [

1]. Therefore, cellulose has been extracted from a variety of residual biomass for various applications, including paper, building materials, automotive materials, textile, food and packaging industries [

2].

The extraction methods of cellulose include chemical methods [

3], biological methods [

4], hydrothermal methods [

5] and microwave (MW)-assisted methods [

6,

7], all aiming for removal of hemicellulose and lignin from biomass feedstocks. In order to be consistent with environmental concerns of using natural materials (agricultural residue), the extraction method of cellulose from those materials should also conform to the environmental issues.

The hydrothermal method recognized as an environmentally friendly process, thus is appropriate to be used for that purpose. It uses an aqueous solution as a reaction system within a closed vessel, and it then creates special conditions of high temperatures and high pressures [

8]. As a result, no or less chemicals are used in the hydrothermal process.

Sugarcane bagasse (SCB)− a fibrous waste material with a high content of cellulose (40-50%, [

7])− is usually brought to the high purify cellulose production [

9]. Thailand is the second largest producer of sugarcane in the world. Therefore, a high number of sugarcane bagasse is generated annually, and will cause an environmental impact if left inappropriately managed. Therefore, a hydrothermal extraction of cellulose from SCB seem to be an attractive way for SCB waste management, resulting from its lower environmental impact and also cost effective. Nevertheless, its efficiency should be concerned together as it has lower capability of extraction compared with conventional chemical methods. Hence, improving its efficiency by introducing a small amount of chemicals or using non-hazardous active substance should be investigated and elucidated.

With benefits from using a non-toxic method and substances for a cellulose extraction, the obtained cellulose from a hydrothermal extraction could be used in applications, which require health safety standards such as food containers and packaging. There have been some literatures employing hydrothermal methods for cellulose extractions from biomass with various extractive solvents including normal water [

10], seawater [

11], hydrochloric acid [

12], alkali [

13,

14]. However, no study has covered various types of solvents for a hydrothermal method, and consequently used the extracted materials for the food container production.

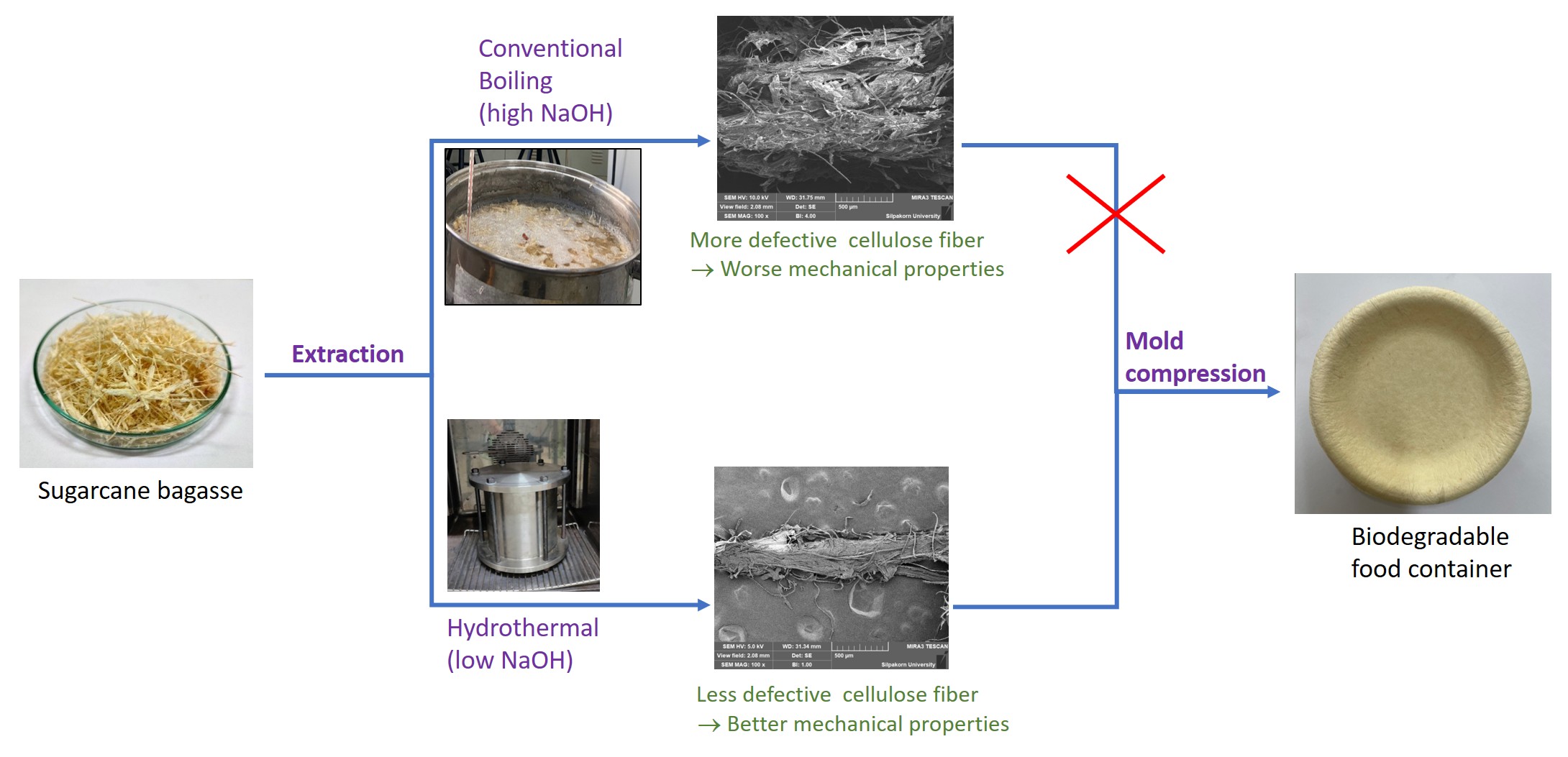

Therefore, in this study, the hydrothermal extractions of SCB to obtain cellulose were carried out with using non-toxic acids i.e., formic acid and citric acid, and also compared with an alkali agent (NaOH). The extracted cellulose was then employed for a food container production. The properties of the cellulose and the finished products were analyzed using appropriate techniques and instrument.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Extraction Ability

The composition of SCB had been first determined to compare the extraction ability of each process, and the composition of the obtained samples were determined as shown in

Table 1. It was found that SCB composed of 47.8% of cellulose, 26.4% of hemicellulose, 18.1% of lignin and the other components. These values close to those in the reviewed literatures [

17,

18]. All samples from various extraction methods showed higher cellulose contents than SCB, but lower hemicellulose and lignin contents. This suggests that all methods have ability to extract cellulose from the materials by removing hemicellulose and lignin.

In samples B-NaOH_low and B-NaOH_high, the conventional extraction methods with boiling the materials with two different concentrations of alkali (NaOH 0.25 and 2 M) were observed. In general, hydroxide ions (-OH) of alkali can weaken the hydrogen bonds between cellulose and hemicellulose, and disrupt the ester linkages between hemicellulose and lignin. In addition, it can break the glycosidic bonds between the monosaccharide groups inside hemicellulose. These lead to more solubilization of both lignin and hemicellulose fragments in the alkali solution, and increasing more energy to the system by boiling can enhance the solubilization [

19,

20]. The higher concentration of NaOH caused the higher extraction ability, with the extraction abilities of 70.5% and 60.4% for B-NaOH_high and B-NaOH_low, respectively. This is due to the higher hydroxide ions in the system. The amounts of hemicellulose and lignin were also lower with the higher alkali concentration.

To increase extraction ability even at the low concentration of alkali, a hydrothermal process was used in comparison as seen in H-NaOH_low and H-NaOH_high. It can be seen that the hydrothermal method increased the extraction ability for both concentrations of NaOH, as previously observed [

21]. The significant increase was found at the low concentration of NaOH (0.25 M), about 10 % from 60.4 to 67.7. This suggests that an influence of the hydrothermal condition was more profound at the lower concentration of NaOH. Thus, it indicates the benefit of the hydrothermal method with using less amount of chemicals compared with the conventional method.

Non-toxic acids i.e., citric acid and formic acid were also employed in the hydrothermal extractions as seen in sample H-Citric_low, H-Citric_high, H-Formic_low and H-Formic_high. Roles of acids in the cellulose extraction are disruption of the lignocellulosic matrix by cleaving glucosidic bonds, and then transforming the polysaccharides into the smaller oligomeric and monomeric sugars. The acids also hydrolyze hemicellulose and lignin, causing them more solubilization [

22,

23,

24]. It should be noted that citric acid and formic acid −weak organic acids with low strength− usually have the lower activity compared with strong acids like HCl and H

2SO

4. However, from the results it shows that both acids still had the relatively high extraction ability from 52.4 to 57.0%. This reveals that the hydrothermal methods could enhance the activity of weak acids for the extraction, and therefore boost a chance for use non-toxic acids instead of toxic acids in the cellulose extraction, for lessening the environmental impact. It was observed that increasing the concentration of acids also increased the extraction ability for both citric acid and formic acid, but slightly. Therefore, low concentration of acid would be used for the cellulose extraction with the hydrothermal method.

In sample H-water, only water was used as an extractive solvent equipped with the hydrothermal method for the extraction. Nevertheless, it can extract the cellulose with a cellulose extraction ability up to 50.1 %. Under hydrothermal condition, water turns into water steam which can disrupt the cellulose structure, hydrolyze the hemicellulose component into smaller sugar molecules, and depolymerize the lignin component into phenolic compounds [

25] . This suggests the efficiency of the hydrothermal system, which can convert water into a capable solvent for the cellulose extraction.

2.2. Cellulose Characterization

The cellulose samples i.e., H-Formic_high, H-Citric_high, and H_NaOH_low were selected to be applied in the food container production due to their high cellulose concentration and low toxic remained after the extraction through the hydrothermal methods. B-NaOH_high represented for the cellulose sample extracted from the conventional method was also selected for the application to compared with the earlier mentioned samples. All selected samples were investigated for the cellulose properties compared with the raw sugarcane bagasse (SCB) and the commercial pure cellulose (Cellulose).

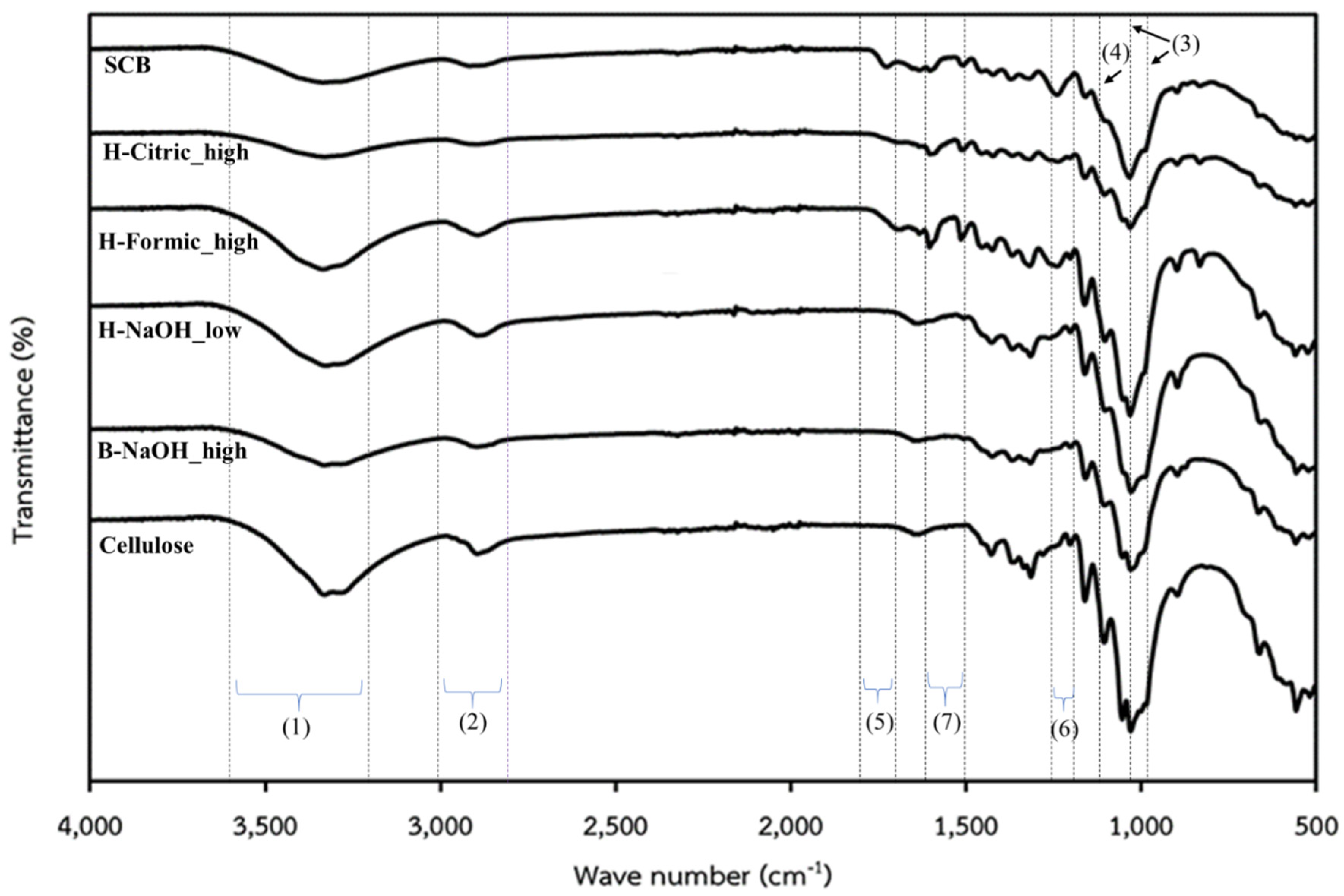

The functional groups of the samples were determined with FTIR, and all obtained FTIR spectra are shown in

Figure 1. All sample spectra exhibited the characteristic peaks of cellulose including O−H stretching between 3600-3200 cm

-1, C−H stretching between 3000-2800 cm

-1, C−O−C stretching at 1159 cm

-1 and 897 cm

-1, and C−O stretching vibration at 1025 cm

-1. Nevertheless, those peaks are not clearly distinct for SCB and H-Formic_high due to the lower contents of cellulose in them. The characteristic peaks of hemicellulose and lignin were observed in SCB, H-Formic_high and H-Citric_high i.e.

, C=O stretching vibration between 1765-1715 cm

-1 of hemicellulose, and C−O−C stretching vibration between 1250-1200 cm

-1 and C=C stretching vibration between 1600-1500 cm

-1 of lignin [

26,

27,

28]. This suggests that in the extracted samples with formic acid and citric acid still had high amounts of hemicellulose and lignin, while the extracted samples with NaOH had small amounts of those components so that they cannot be observed by the FTIR. These results are in agreement with the data in

Table 2.

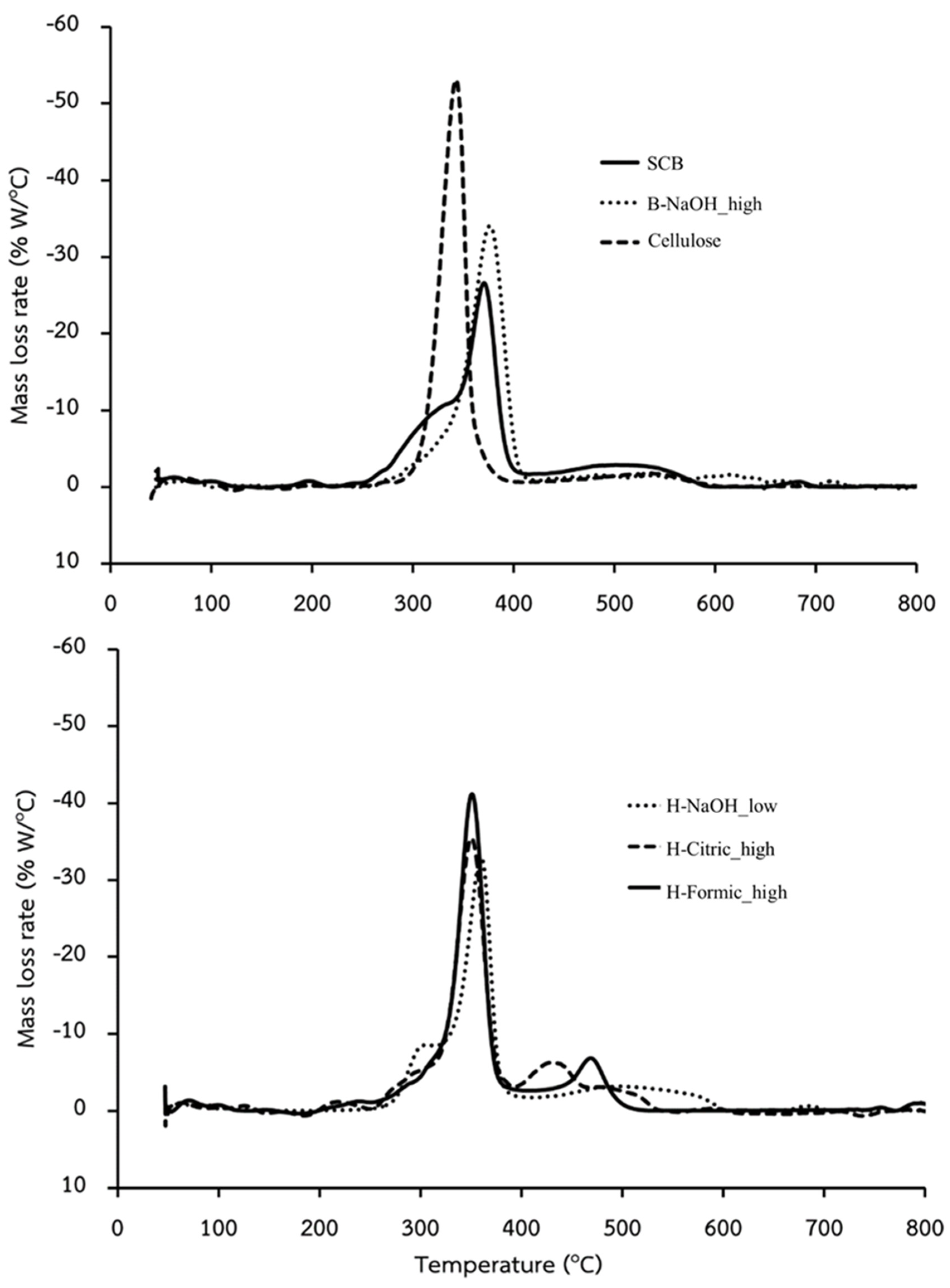

Thermal stability of the cellulose samples was evaluated with a TGA measurement, and also a DTG analysis, which analyses the first derivative of the TGA curve. The DTG peaks of the samples shown in

Figure 2 can indicate a specific thermal event occur during the heating process. It was found that all samples except cellulose had 3 DTG peaks, but in different degrees for each sample. This suggests 3 ranges of thermal decomposition during heating. In general, the thermal decomposition between 245-290

°C is the decomposition of hemicellulose, 290-350

°C is the decomposition of cellulose and 350-500

°C is the decomposition of lignin [

29]. It was seen that for SCB all 3 peaks cannot be unclearly distinct due to a high number of other components. For the cellulose peaks, they obviously seen for all extracted samples with slightly shift from that of the pure cellulose. These shifts could be derived from change in nature of the cellulose, probably due to MW and crystallinity. The lignin and hemicellulose peaks were clearly observed for H-Formic_high and H_Citric_high, but slightly observed for H-NaOH_low and B-NaOH_high due to their low contents.

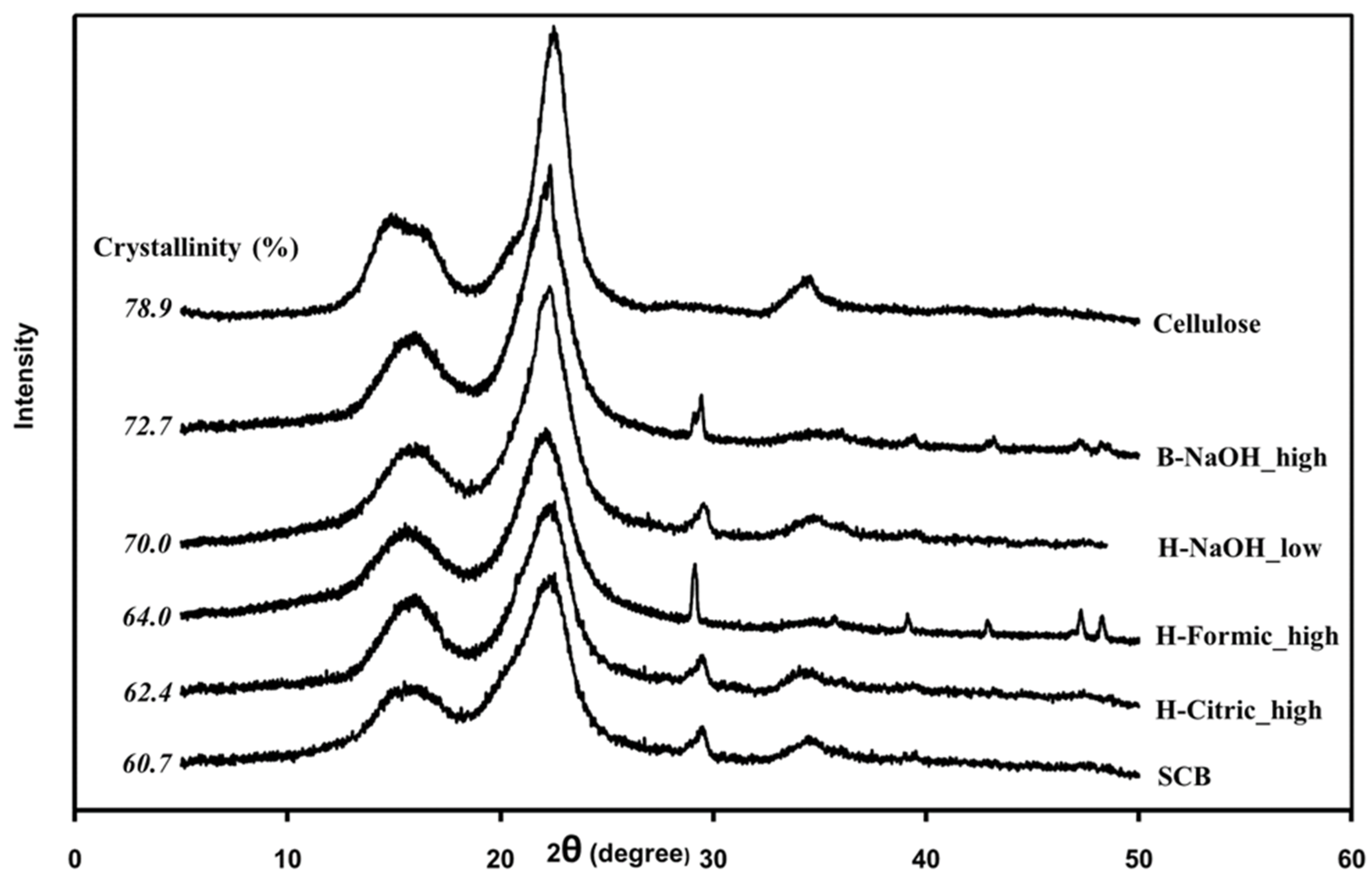

Crystal structures of the cellulose samples were evaluated with an XRD analysis. The characteristic XRD peaks of cellulose generally appear at 2

θ=16.5°, 22.5°, and 34.3° which correspond to the crystallographic planes of (110), (200) and (040) respectively [

29,

30]. The XRD patterns of all cellulose samples are shown in

Figure 3. It was seen that all samples exhibited the XRD peaks correlated to the characteristic peaks of cellulose as mentioned above. From the cellulose XRD peaks, they can be calculated for crystallinity of the cellulose, and the cellulose crystallinity were also shown in the figure. The pure cellulose exhibited the highest crystallinity of 78.9%, in agreement with the values reported previously [

31]. All extracted samples had the higher cellulose crystallinity (62.4-72.7%) than SCB (60.7%). This was due to the raw biomass composing of high contents of other components including hemicellulose and lignin which disturb the crystallization process of the cellulose [

32,

33]. Moreover, the higher cellulose crystallinity of the extracted samples came from the combination of recrystallization and hornification of cellulose after the extraction [

34]. The higher fractions of lignin and hemicellulose in H-Formic_high and H-Citric_high, which correspond to the amorphous parts of the material lead to their lower crystallinity compared with the alkali-extracted samples.

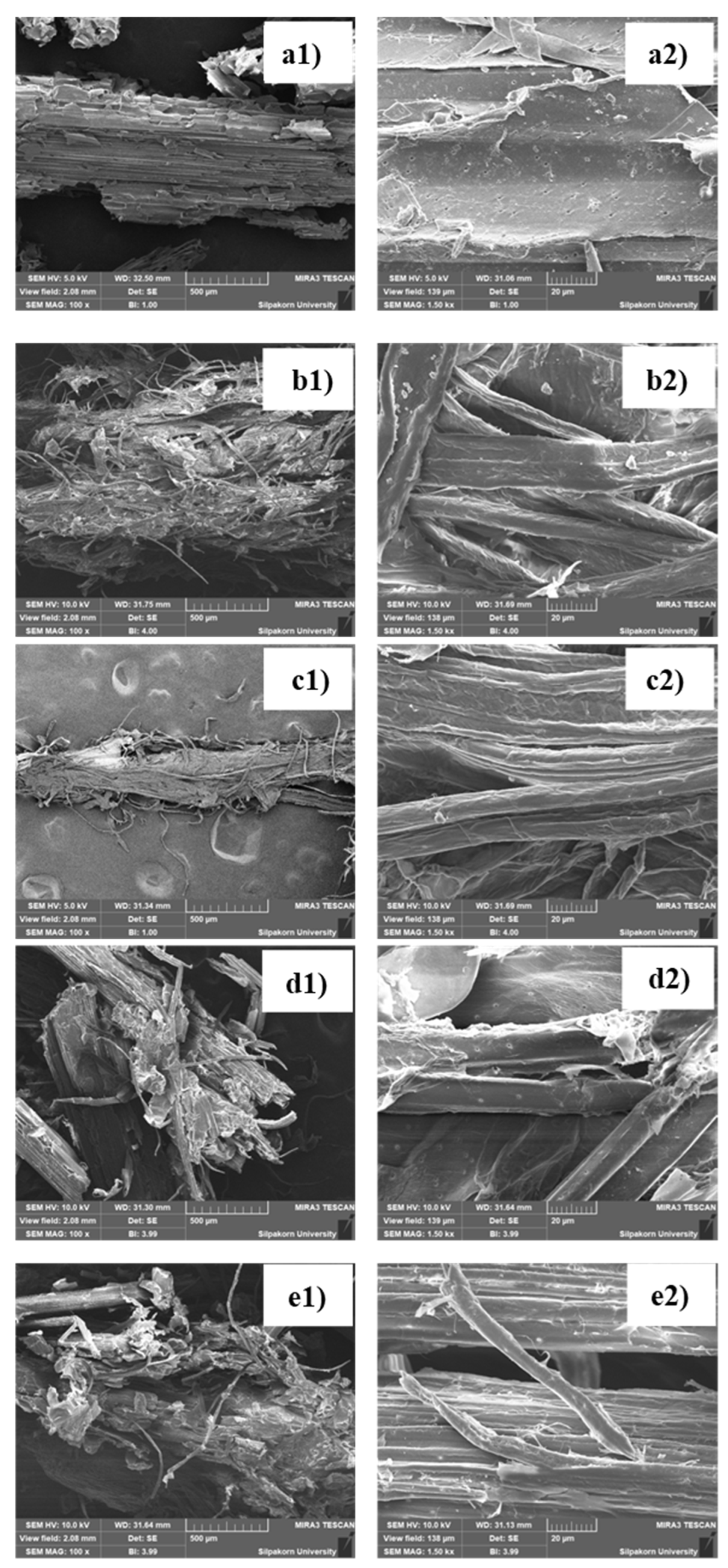

Morphologies of the cellulose samples were determined using an SEM analysis, and the SEM images with various magnificent of all samples are shown in

Figure 4. SCB showed a compact morphology covered with cell walls, while the extracted samples exhibited a loose morphology with more fibers exposed. The alkali-extracted samples exhibited more segregated fibers, compared with the organic acid-extracted samples (H-Formic_high and H-Citric_low). The latter samples still have the high amounts of hemicellulose which help hold cellulose fiber together, and also lignin which keep the fiber structure rigid and bind hemicellulose with cellulose. Comparing between two alkali-extracted samples, it can be seen that B-NaOH_high with the high alkali concentration provided more damaged fibers, compared with H-NaOH_low. The higher concentration of NaOH leaded to vigorous reactions, and consequently deformed the structures of fibers.

2.3. Food Container Production

The selected extracted samples were brought to form a sheet for further use in the food container production, by first mixing with a starch and being passed through a compression mold. It was found that only H-NaOH_low and B-NaOH_high could be constructed into a sheet. The cellulose fibers of H-Citric_high and H-Formic_high did not form a sheet. They were fragile and unable to withstand stretching during the process. This is related to the purity of the cellulose, and the structural characteristic of the fibers as seen from the SEM. As observed, the fibers extracted using the organic acids have the lower cellulose contents, and more defective structures than those extracted with the alkali.

The attained sheets from H-NaOH_low and B-NaOH_high were tested for their mechanical properties, and the results are shown in

Table 2. All measuring values indicate that the sheet produced from H-NaOH_low had better mechanical properties than B-NaOH_high. This is reasoned from low damaged fibers of H-NaOH_low under the hydrothermal treat. This suggests the benefit of the hydrothermal method, which provides the extracted cellulose fibers with high quality with less chemicals.

The sheet derived from H-NaOH_low was then chosen for the production of food container i.e.

, 7-inch plate using a specific mold. The mechanical properties of the produced plate were determined and compared with two sampling commercial plates (sugarcane bagasse plates) as the results shown in

Table 3. It can be seen that the produced plate had most mechanical propertied comparable to the commercial ones. The slightly lower value of tensile strength of the produced plate may because of no introduction of some additives and a coating process, which enhance the strength of the commercial products. For more stretchability (elongation at break) and more resistance to tear (tear strength values) of the produced plate than the commercial ones, it was probably due to good quality of the fibers obtained from the hydrothermal methods.

Biodegradability of the food containers was also evaluated by burying the samples and observing physical changes. It was found that the as-produced plate in this study was easily decomposed under environment and almost completely within a week, while the commercial ones could be last for 7 weeks. As mentioned earlier, the produced plate here was not passed the coating process, and without addition of special additives. Thus, the obtained product in this study need to be improved for its durability, but has to maintain its benefit of biodegradability.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Material

Sugarcane bagasse was collected from Raimaijon Co.,Ltd, Thailand. It was cut into 3-4 cm length, and then boiled in hot water for 30 mins (2-3 times) until the Brix value of the solution becomes zero, indicating no sugar left in the bagasse. After that, the bagasse was dried under sunlight for 3 days, and consequently dried in an oven at 80°C for 24 hrs, and then kept in an airtight container for further use. Analytical grade chemicals i.e., citric acid, formic acids, sodium hydroxide and ethanol were obtained from Merck.

3.2. Cellulose Extraction

3.2.1. Chemical Method

The chemical method, which uses chemicals for extraction, is considered a conventional method, conducted here for comparing with an environmentally friendly hydrothermal method. It started by immersing bagasse in a stirring solution of NaOH (0.25 and 2 M) for 2 h at 90°C with the ratio of fiber/solution = 1:20 by weight. After that, the bagasse was removed from the solution and washed several times with tap water, and neutralized by immersing in an acetate buffer (1 mol/L, pH 5.5) for 2 hrs. It was washed again with deionize water until the pH of solution was closed to 7, filtrated and dried at 65°C for 1 day in an air circulating oven, and kept in a desiccator for further use.

3.2.2. Hydrothermal Method

The hydrothermal extractions were carried out with a 2-L stainless steel reactor chamber, featured with an inner Teflon liner. A solution of water, non-toxic acid: formic and citric acids (0.25 and 2 M), or NaOH (0.25 and 2 M) was first introduced into the reactor for each experimental run. The bagasse with the ratio of fiber/solution = 1:20 was filled into the reactor, and it was placed in the oven at 90°C for 2 hrs. After that, the bagasse was treated following the same procedure as the conventional methods, mentioned above.

3.3. Food Container Production

The obtained bagasse fibers (cellulose) were brought for the food container production using a self-designed mold with a compression machine. Firstly, 50 g of cellulose was first mixed with a colloidal solution of starch (5 g of corn flour in 500 g of water). The slurry mixture was sieved, dried, and spread in the mold. Then, the mold was placed in the compression machine at 60°C and 50 kg/cm3 for 5 mins. The obtained product was removed from the mold, and kept for further testing.

3.4. Characterization

3.4.1. Chemical Composition

The raw bagasse and the extracts were analyzed for their composition according to the procedures described by Mensaha et al. [

15]. The sample, W

A (1 g) was boiled in 60 ml of acetone at 90°C for 2 h. After that, the fiber sample was separated, washed with deionized water, and dried at 110°C. The finished sample (W

B) was weighted, and then calculated for a percentage (by weight) of contaminants inside the sample, using the followed equation (Equation (1));

After removing the contaminants, the compositions of the sample i.e., hemicellulose, lignin and cellulose were then determined.

1 g (W

B) of sample (free-contaminant bagasse) was boiled in a solution of 0.5 M NaOH of volume 150 ml, at 80°C for 3 hrs 30 mins. Then, the sample was separated, washed with deionized water until neutral, and dried at 110°C until constant weight. The final weight (W

C) was used to calculated for a percentage of hemicellulose by using the followed equation (Equation (2));

1 g (W

A) of sample (raw bagasse) was soaked in a solution of sulfuric acid of volume 30 ml, for 4 hrs, and then boiled at 100°C for 1 hr. Then, the sample was separated, washed with deionized water until neutral, and the filtrate was titrated with an acid for ensuring no sulfate ions left in the system. The obtained sample was dried at 110°C and weighted, and the obtained weight (W

D) is immediately the lignin weight which was then converted into a percentage as the followed equation (Equation (3)).

The weight of cellulose was calculated by subtraction of the weight of raw bagasse with the total of contaminants, hemicellulose and lignin, and was converted into a percentage according to the following equation (Equation (3));

3.4.2. Functional Group

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used to determine functional groups of the samples, with Thermo SCIENTIFIC, NICOLET iS5. FTIR spectra were collected in the transmittance mode and recorded in the range of 400-4000 cm-1 at 1 cm-1 resolution.

3.4.3. Thermal Stability

Thermal stability and decomposition behavior of the samples were analyzed by thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) using Pyris I TGA, PerkinElmer, Inc. Each sample was heated from 50°C to 800°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min under nitrogen environment.

3.4.4. Crystal Structure

An X-ray diffractometer (XRD) analysis was employed to determine crystal structures of the samples, using PANalytical, Aris. The scanning range was from 2θ of 0-60 at a speed of 2°/min with Cu-K, radiation of wavelength 1.54 Å. XRD crystallinity indexes (% CrI) were calculated from the method developed by Segal et al. [

16] as the following equation;

where I

002 is the intensity of the 002 crystalline peak at 22° and I

AM is the height of the minimum between the 002 and the 101 peaks.

3.4.5. Morphology

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was employed for investigating surface morphology of the samples, using MIRA 3, Tescan. The samples were mounted on stubs and sputter coated with gold for 15-30 s before being examined.

3.4.6. Mechanical Property

A universal testing machine (UTM) (Comtech, QC-536M1-2L4) was used to evaluate mechanical properties of the samples, according to ASTM D412 (Die C) for their tensile properties and elongation at break, and ASTM D624 (Die B) for their tear strength. The prepared samples were cut to the required size and shape according to the mentioned standards.

5. Conclusions

SCB was extracted for the cellulose with the hydrothermal method with various solvents, compared with the conventional boiling method. It was found that the hydrothermal with the alkali was more efficient than with the organic acids (citric and formic). Using low concentration of alkali (0.25M) with the hydrothermal extraction (H-NaOH_low) exhibited the cellulose extraction ability near to that using high concentration of alkali (2M) with the conventional boiling method (B-NaOH_high). H-NaOH_low also provided the fibers with low defect structure, and then revealed the better mechanical properties than B-NaOH_high. The high concentration of alkali leads to vigorous reactions and damages the cellulose fibers. Thus, the hydrothermal extraction has a benefit of using less chemicals and then lower environmental impact. In addition, H-NaOH_low was employed for the food container production, and found that the obtained product has the excellent properties comparable with the commercial ones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and E.C.; methodology, A.J.; formal analysis, A.J., T.S., K.S. and E.C.; investigation, A.J., T.S., K.S. and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, A.J. and E.C.; funding acquisition, A.J. and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Research Council of Thailand.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Trin Pathomnithipinyo (Department of industrial Promotion, Ministry of Industry, Thailand) for laboratory facilities and technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Causer, T.P.; Ciolkosz, D. Biomass for energy: A review on supply chain management models. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husin, M.; Rahim, N.; Ahmad, M.R.; Romli, A.Z.; Ilham, Z. Hydrolysis of microcrystalline cellulose isolated from waste seeds of Leucaena leucocephala for glucose production. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2019, 15, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, L. ; Manikanika Extraction of cellulosic fibers from the natural resources: A short review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.K.; Xu, C.; Qin, W. Biological Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuels and Bioproducts: An Overview. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisanti, P.N.; Rifan, M.; Akbar, P.; Gunardi, I.; Sumarno, S. Isolation of cellulose from teak wood using hydrothermal method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2349. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Liang, K.; Wang, M.; Xing, T.; Chen, C.; Wang, Q. Microwave-assisted Formic Acid/Cold Caustic Extraction for Separation of Cellulose and Hemicellulose from Biomass. Bioresour. 2023, 18, 6896–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.X.; Sun, X.F.; Zhao, H.; Sun, R.C. Isolation and characterization of cellulose from sugarcane bagasse. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 84, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Park, S.-J. Conventional and Microwave Hydrothermal Synthesis and Application of Functional Materials: A Review. Mater. 2019, 12, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumla, N.; Sakuanrungsirikul, S.; Punpee, P.; Hamarn, T.; Chaisan, T.; Soulard, L.; Songsri, P. Sugarcane Breeding, Germplasm Development and Supporting Genetics Research in Thailand. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Armijos, J.; Lapo, B.; Beltrán, C.; Sigüenza, J.; Madrid, B.; Chérrez, E.; Bravo, V.; Sanmartín, D. Effect of Alkaline and Hydrothermal Pretreatments in Sugars and Ethanol Production from Rice Husk Waste. Resour. 2024, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akatwijuka, O.; Gepreel, M.A.H.; Abdel-Mawgood, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Saito, Y.; Hassanin, A.H. Green hydrothermal extraction of banana cellulosic fibers by seawater-assisted media as an alternative to freshwater: physico-chemical, morphological and mechanical properties. Cellul. 2023, 30, 9989–10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, M.; Ling, C.; Hou, W.; Yan, Z. Extraction and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from waste cotton fabrics via hydrothermal method. Waste Manage. 2018, 82, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.R.; Hirata, S.; Hassan, M.A. Combined pretreatment using alkaline hydrothermal and ball milling to enhance enzymatic hydrolysis of oil palm mesocarp fiber. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 169, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machmudah, S. ; Wahyudiono; Trisanti, P. N.; Setyawan, H.; Madhania, S.; Sambodho, K.; Winardi, S.; Adschiri, T.; Goto, M. Hydrothermal alkaline treatment of lignocellulosic biomass for microcrystalline cellulose generation at subcritical water. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 51, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, I.; Ahiekpor, J.C.; Herold, N.; Bensah, E.C.; Pfriem, A.; Antwi, E.; Amponsem, B. Biomass and plastic co-pyrolysis for syngas production: Characterisation of Celtis mildbraedii sawdust as a potential feedstock. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Creely, J.J.; Martin, A.E.; Conrad, C.M. An Empirical Method for Estimating the Degree of Crystallinity of Native Cellulose Using the X-Ray Diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 1959, 29, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelee, K.; Yingkamhaeng, N.; Nimchua, T.; Sukyai, P. Extraction and characterization of cellulose from sugarcane bagasse by using environmental friendly method. In lp]. 2014. Publisheol-[p];’/r.

- Melesse, G.T.; Hone, F.G.; Mekonnen, M.A. Extraction of Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse Optimization and Characterization. 2022, 2022, 1712207.

- Kumar, R.; Strezov, V.; Weldekidan, H.; He, J.; Singh, S.; Kan, T.; Dastjerdi, B. Lignocellulose biomass pyrolysis for bio-oil production: A review of biomass pre-treatment methods for production of drop-in fuels. 2020, 123, 109763.

- Mafa, M.S.; Malgas, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Rashamuse, K.; Pletschke, B.I. The Effects of Alkaline Pretreatment on Agricultural Biomasses (Corn Cob and Sweet Sorghum Bagasse) and Their Hydrolysis by a Termite-Derived Enzyme Cocktail. 2020, 10, 1211.

- Kumneadklang, S.; O-Thong, S.; Larpkiattaworn, S. Characterization of cellulose fiber isolated from oil palm frond biomass. 2019, 17, 1995–2001.

- Rattanaporn, K.; Tantayotai, P.; Phusantisampan, T.; Pornwongthong, P.; Sriariyanun, M. Organic acid pretreatment of oil palm trunk: effect on enzymatic saccharification and ethanol production. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering 2018, 41, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarte-Toro, J.C.; Romero-García, J.M.; Martínez-Patiño, J.C.; Ruiz-Ramos, E.; Castro-Galiano, E.; Cardona-Alzate, C.A. Acid pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for energy vectors production: A review focused on operational conditions and techno-economic assessment for bioethanol production. 2019, 107, 587–601.

- Xiong, B.; Ma, S.; Chen, B.; Feng, Y.; Peng, Z.; Tang, X.; Yang, S.; Sun, Y.; Lin, L.; Zeng, X.; Chen, Y. Formic acid-facilitated hydrothermal pretreatment of raw biomass for co-producing xylo-oligosaccharides, glucose, and lignin. 2023, 193, 116195.

- Martín, C.; Dixit, P.; Momayez, F.; Jönsson, L.J. Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Feedstocks to Facilitate Biochemical Conversion. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2022, 10, 846592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Negi, Y.S.; Choudhary, V.; Bhardwaj, N.K. Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals Produced by Acid-Hydrolysis from Sugarcane Bagasse as Agro-Waste. 2014, 2, 1–8.

- Thite, V.S.; Nerurkar, A.S. Valorization of sugarcane bagasse by chemical pretreatment and enzyme mediated deconstruction. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 15904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choquecahua Mamani, D.; Otero Nole, K.S.; Chaparro Montoya, E.E.; Mayta Huiza, D.A.; Pastrana Alta, R.Y.; Aguilar Vitorino, H. Minimizing Organic Waste Generated by Pineapple Crown: A Simple Process to Obtain Cellulose for the Preparation of Recyclable Containers. 2020, 5, 24.

- Romruen, O.; Karbowiak, T.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Shiekh, K.A.; Rawdkuen, S. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose from Agricultural By-Products of Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzi, F.; Puglia, D.; Sarasini, F.; Tirillò, J.; Maffei, G.; Zuorro, A.; Lavecchia, R.; Kenny, J.M.; Torre, L. Valorization and extraction of cellulose nanocrystals from North African grass: Ampelodesmos mauritanicus (Diss). Carbohydrate polymers 2019, 209, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Varanasi, P.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Melnichenko, Y.B.; Simmons, B.A.; Kent, M.S.; Singh, S. Transition of Cellulose Crystalline Structure and Surface Morphology of Biomass as a Function of Ionic Liquid Pretreatment and Its Relation to Enzymatic Hydrolysis. 2011, 12, 933–941.

- Park, S.; Baker, J.O.; Himmel, M.E.; Parilla, P.A.; Johnson, D.K. Cellulose crystallinity index: measurement techniques and their impact on interpreting cellulase performance. 2010, 3, 10.

- Fang, S.; Xia, Q.; Lin, Z.; Zhan, P.; Qing, Y.; Wang, H.; Shao, L.; Liu, N.; He, J.; Liu, J. Differentiated Fractionation of Various Biomass Resources by p -Toluenesulfonic Acid at Mild Conditions. 2023, 8.

- Ethaib, S.; Omar, R.; Mustapa Kamal, S.; Radiah, D. Comparison of sodium hydroxide and sodium bicarbonate pretreatment methods for characteristic and enzymatic hydrolysis of sago palm bark. 2020, 46, 1–11.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).