Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

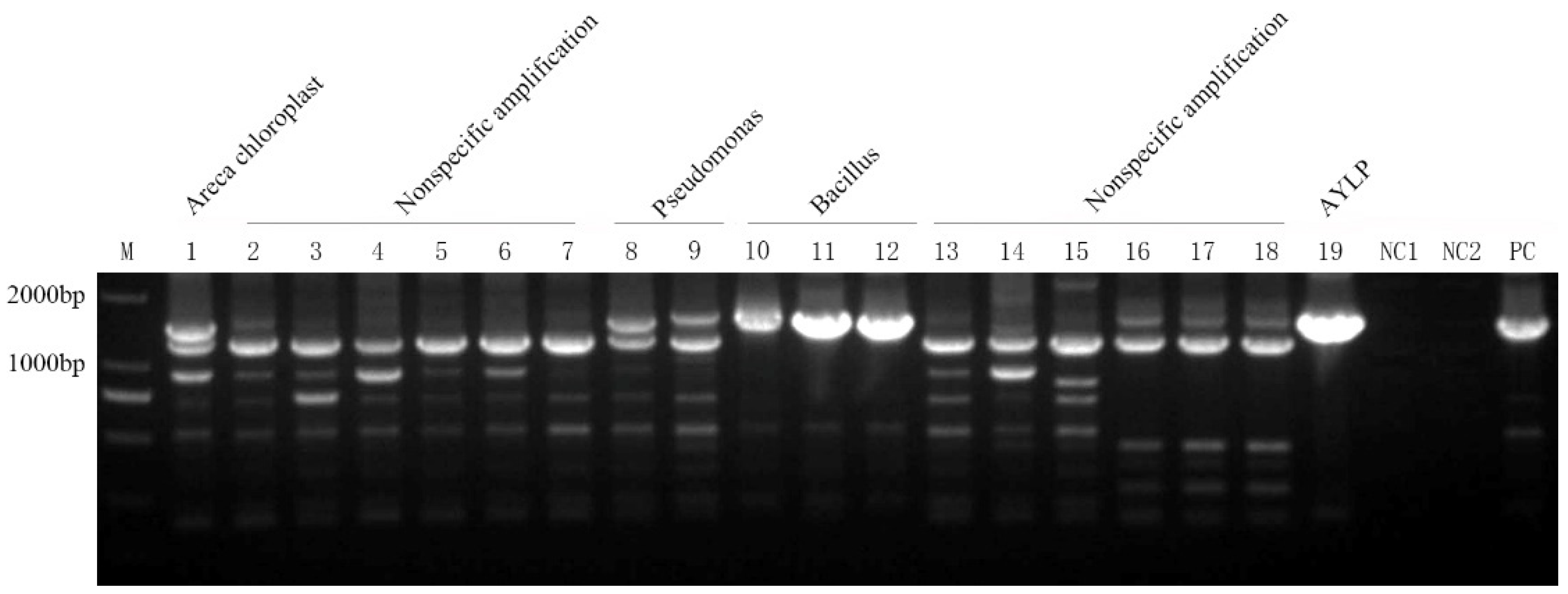

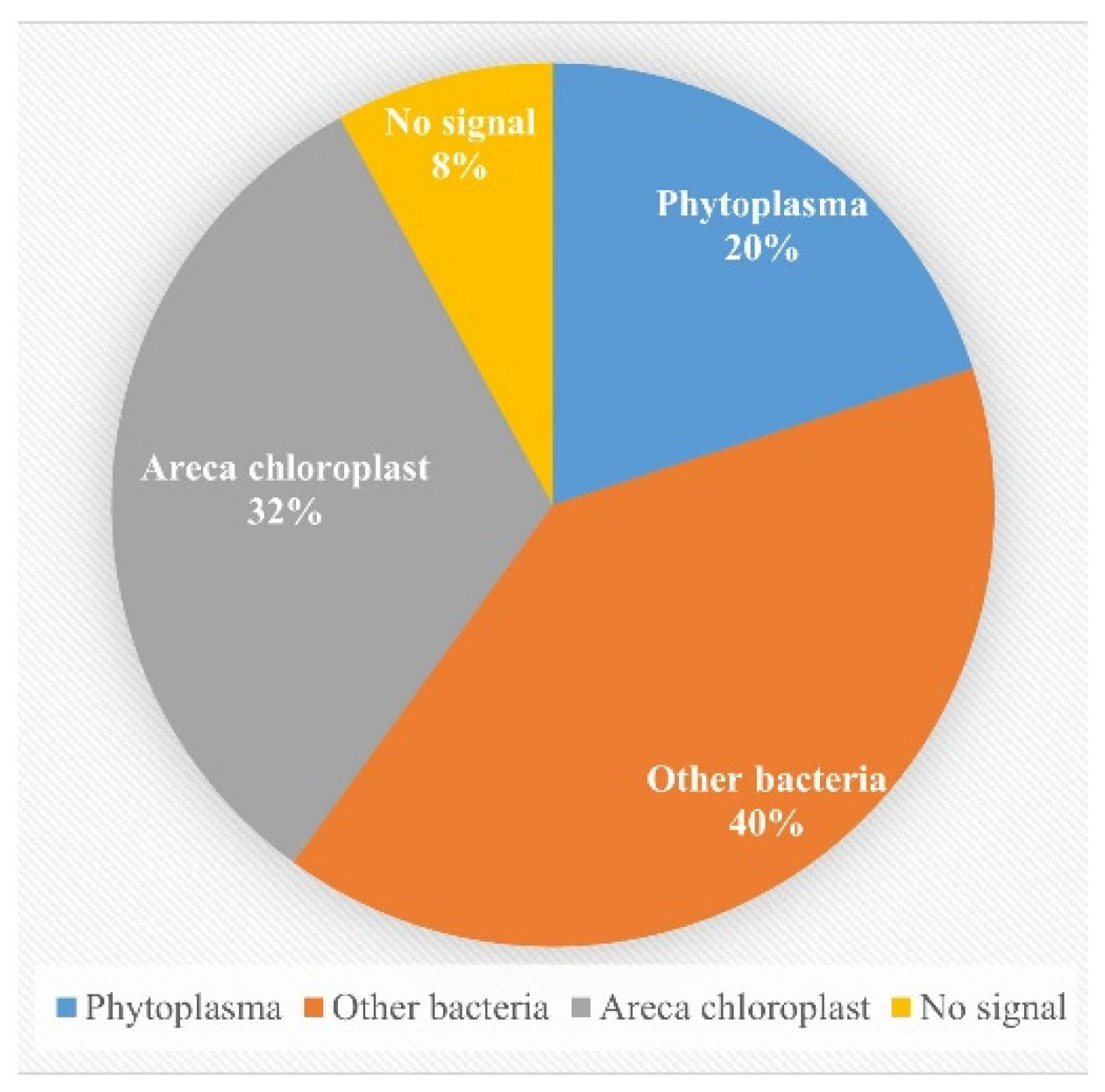

2.1. Application of Universal Nested PCR for Phytoplasma Detection

2.2. Nested PCR Primer Test and Combination

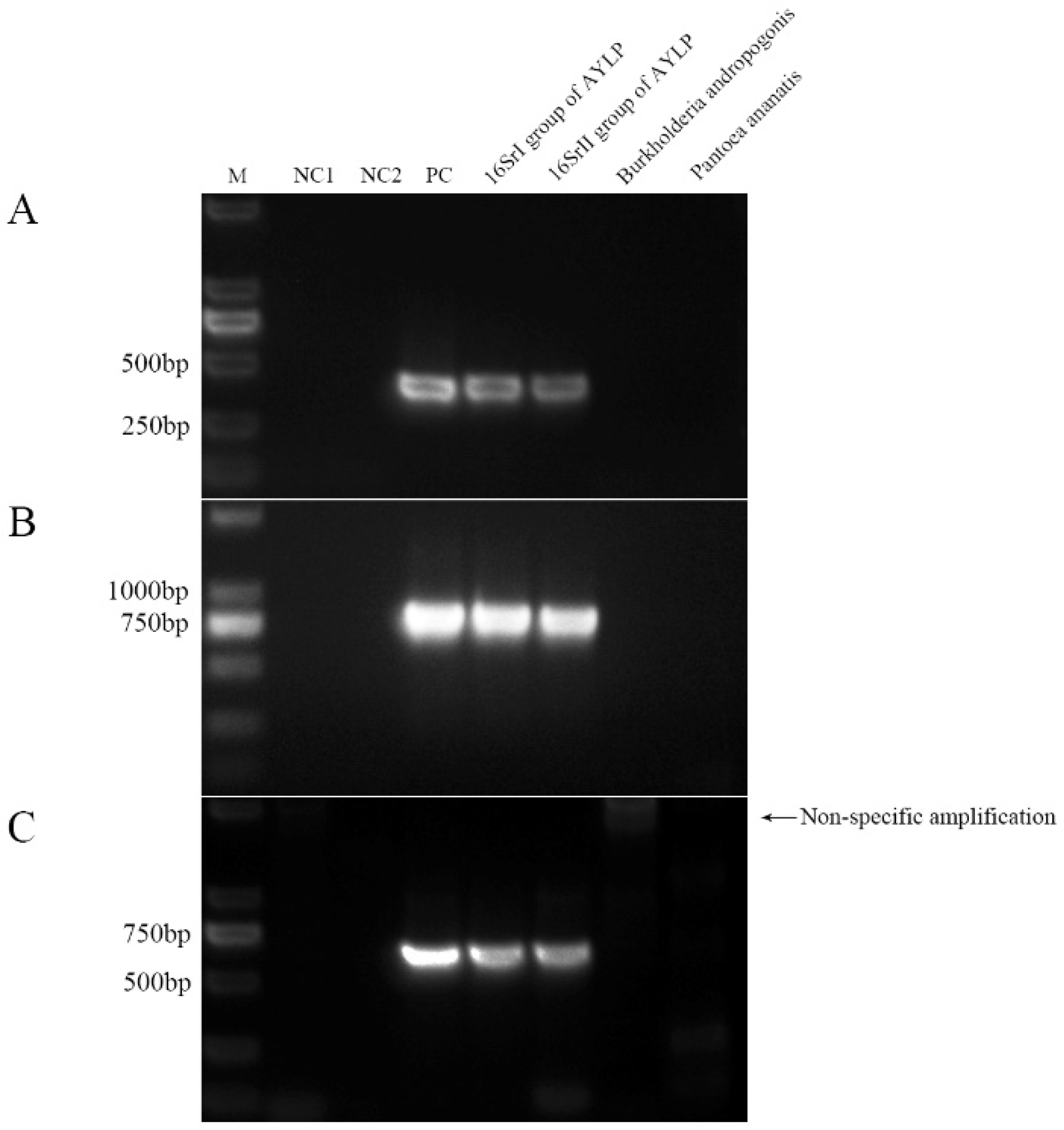

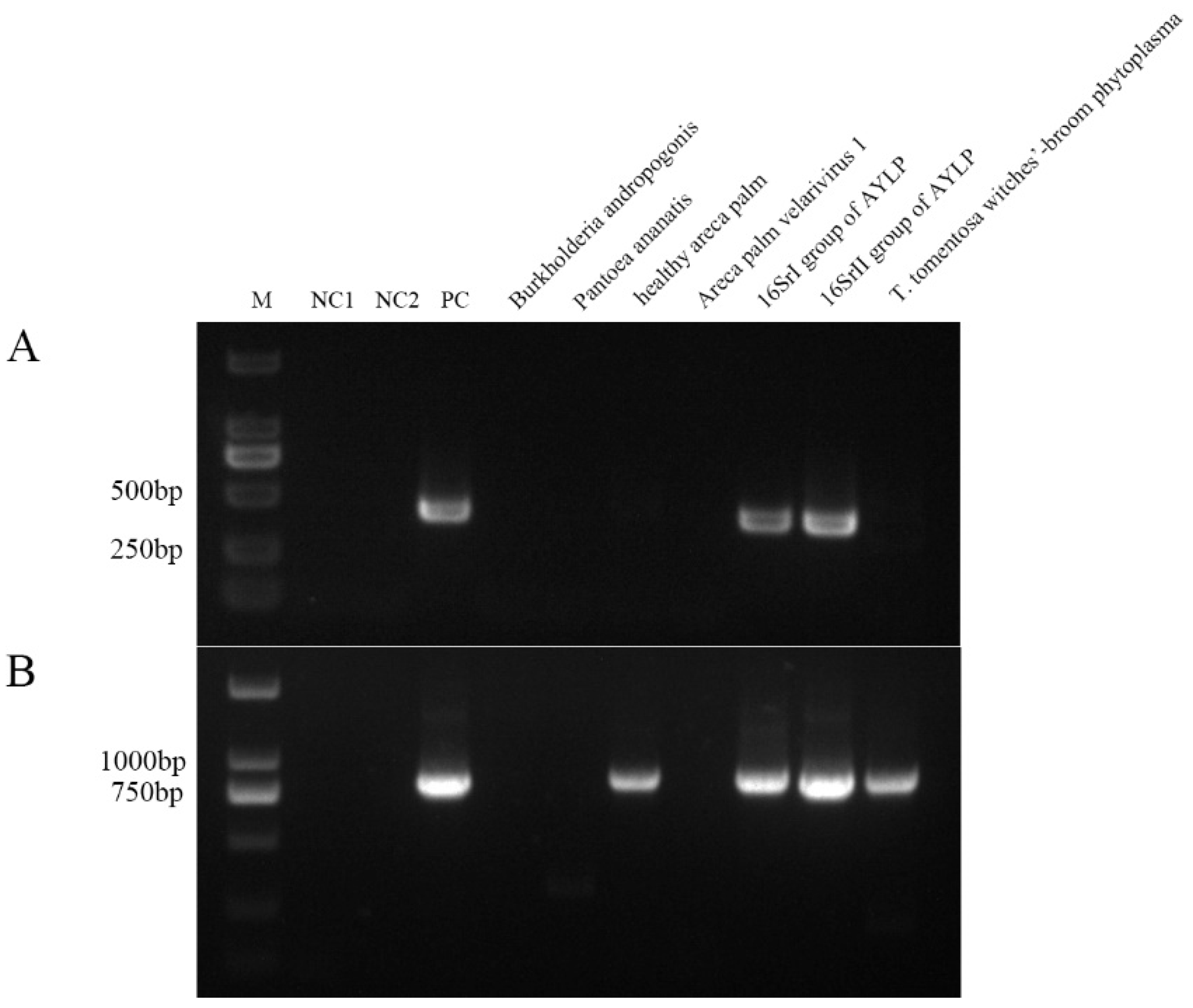

2.3. Specificity Validation of Nested PCR

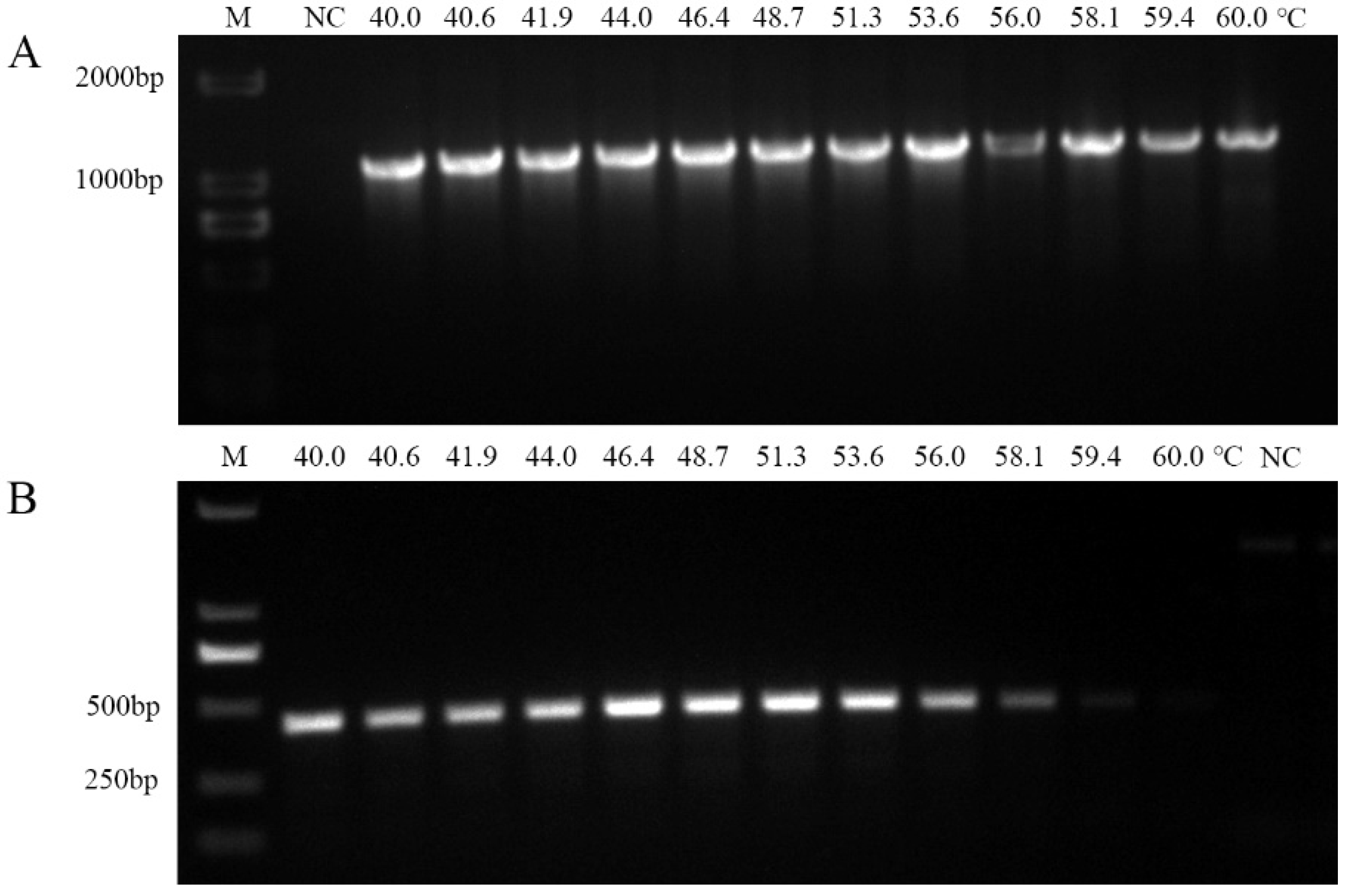

2.4. Optimization of PCR Annealing Temperatures

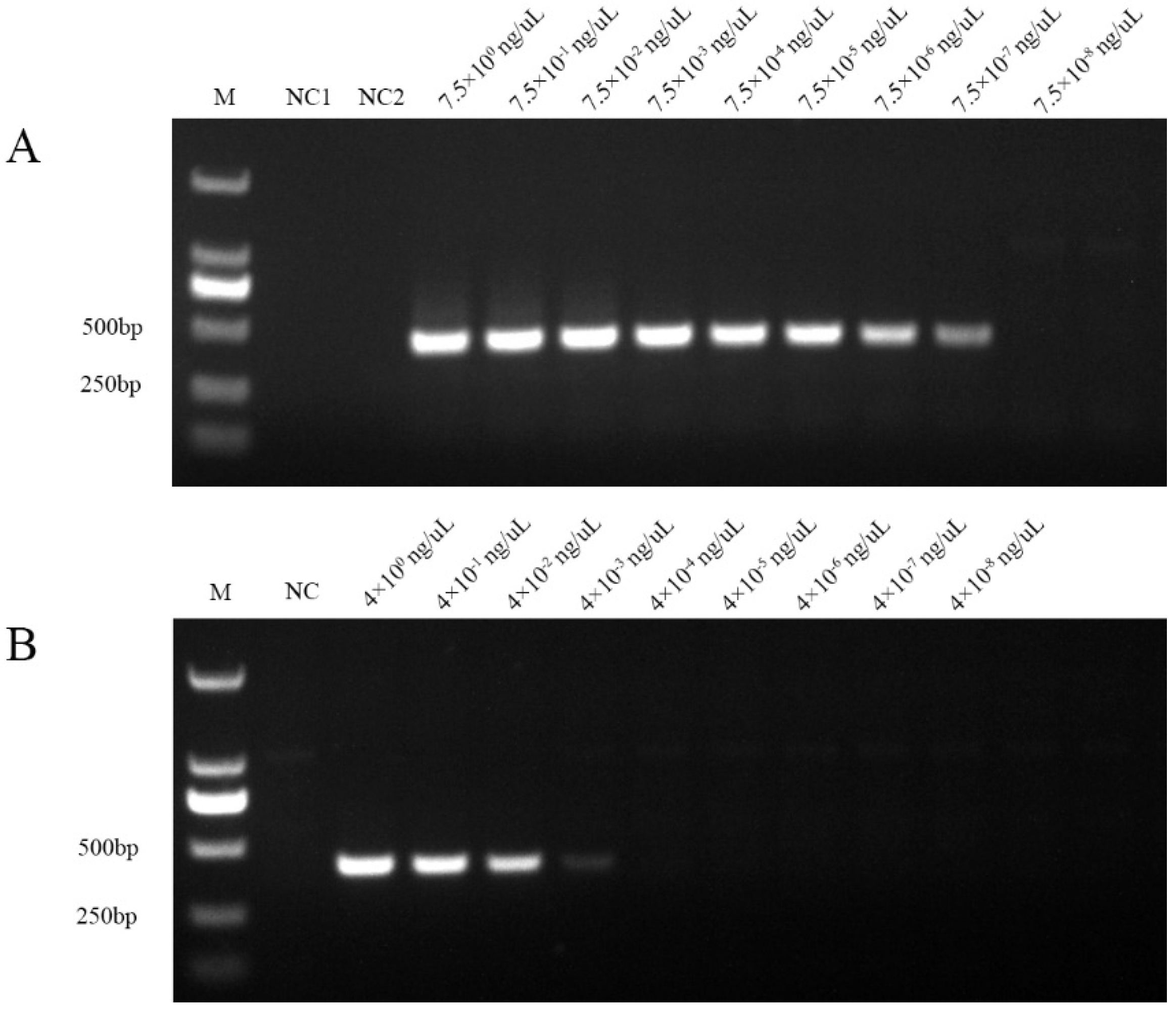

2.5. Sensitivity Determination of Nested PCR

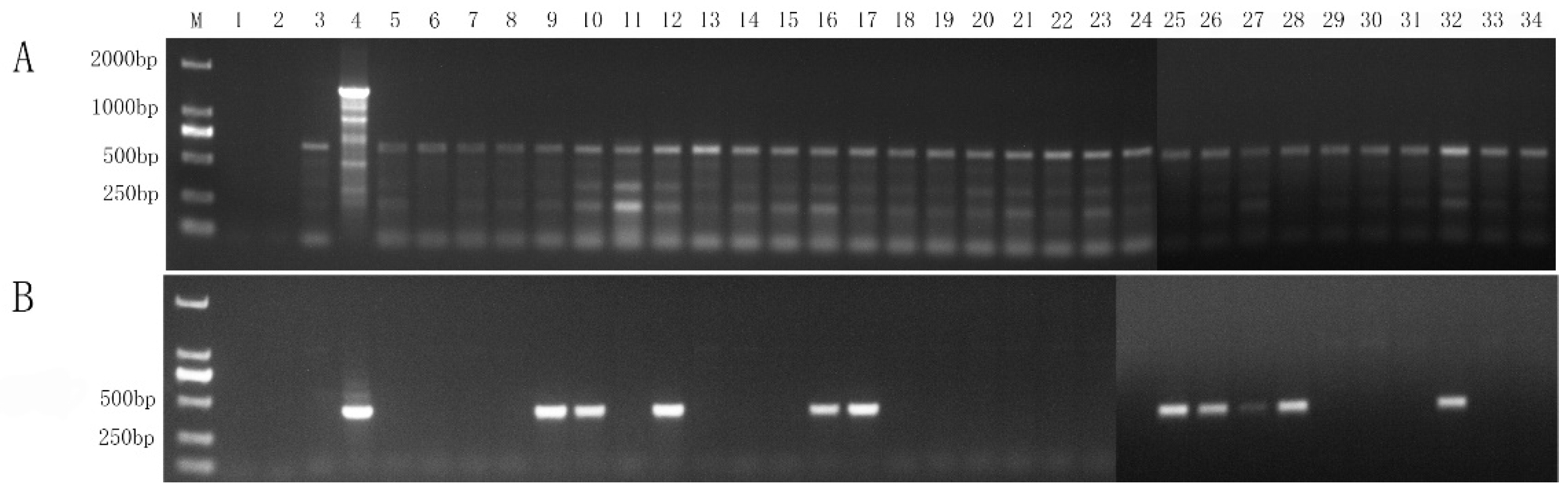

2.6. Comparison of The Newly Developed Nested PCR with Universal Nested PCR

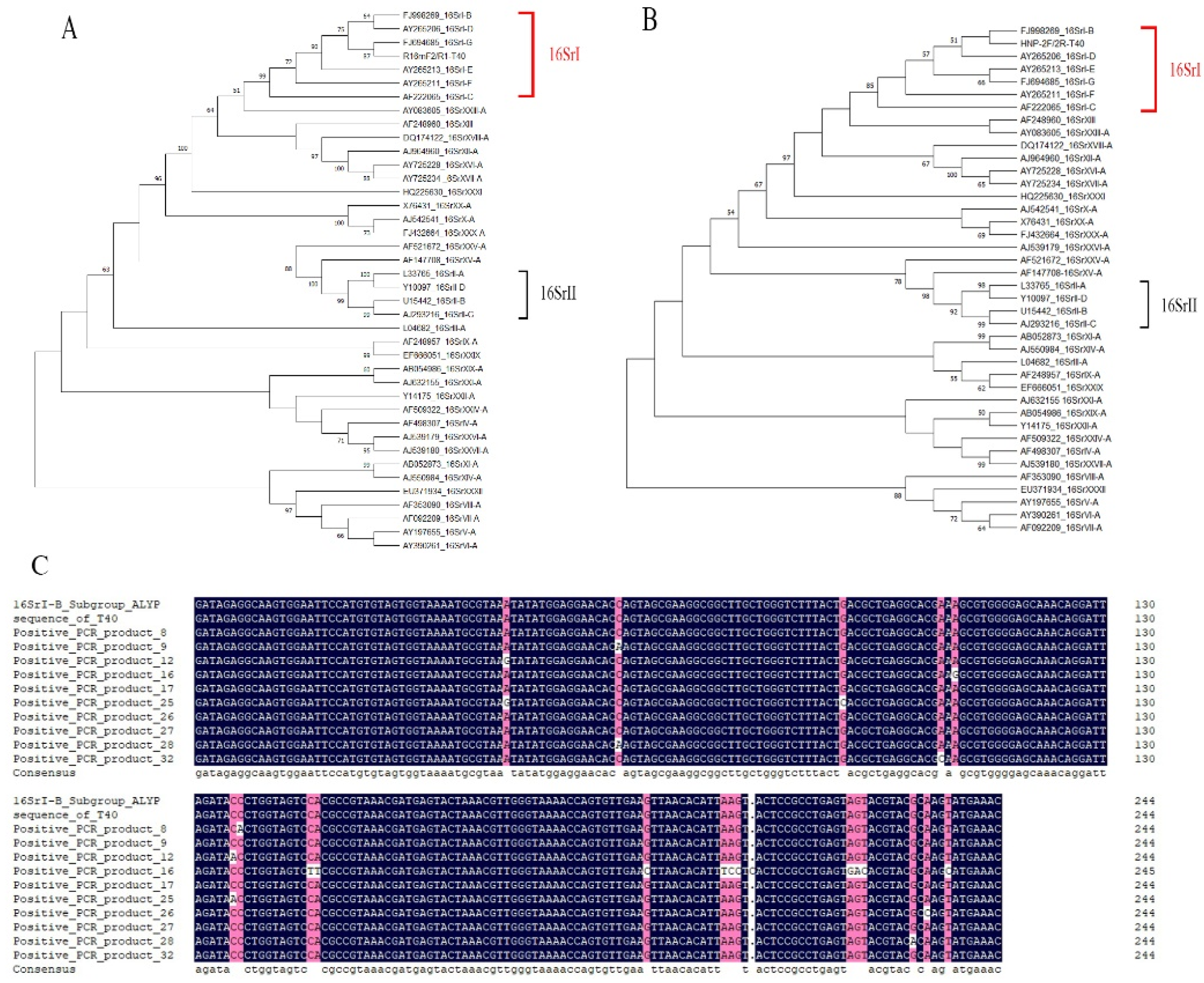

2.7. Construction and Analysis of Phylogenetic Trees

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Extraction of Total DNA from Areca Plam Leaf Samples Showing Yellow

4.3. Construction of Recombinant Plasmids for 16S rDNA of Areca Palm Yellow Leaf Phytoplasma

4.4. Design and Primary Screening of Specific Primers

4.5. Specificity Verification of Nested PCR

4.6. Optimization of Annealing Temperatures for Nested PCR with Internal Primers

4.7. Establishment of Nested PCR Reaction System

4.8. Sensitivity Testing of Newly Developed Nested PCR

4.9. Comparison of Newly Developed Nested PCR Method with Universal Nested PCR Method

4.10. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Fragment Amplified from Primers HNP1F/1R and HNP-2F/2R

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YLD | Yellow leaf disease of areca palm |

| AYLP | areca palm yellow leaf phytoplasma |

| LAMP | loop-mediated isothermal amplification |

| qPCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| ddPCR | droplet digital PCR |

Appendix

| No | Sample | Result | City/County | Time | No | Sample | Result | City/County | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | J069 | Positive | Wenchang | 2022 | 169 | ZB1-2 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 2 | A056 | Positive | Wenchang | 2022 | 170 | MQR4 | Negative | Ledong | 2021 |

| 3 | T40 | Positive | Wenchang | 2022 | 171 | HL3-4 | Negative | Ledong | 2021 |

| 4 | W4 | Positive | Wenchang | 2022 | 172 | HL3-1 | Negative | Ledong | 2021 |

| 5 | S97 | Positive | Wenchang | 2022 | 173 | HL1-2 | Negative | Ledong | 2021 |

| 6 | M25 | Positive | Wenchang | 2023 | 174 | HZ3-2 | Negative | Ledong | 2021 |

| 7 | H61 | Positive | Wenchang | 2023 | 175 | HZ5-2 | Negative | Ledong | 2021 |

| 8 | H64 | Positive | Wenchang | 2023 | 176 | T52 | Negative | Ledong | 2021 |

| 9 | R71 | Positive | Waning | 2022 | 177 | NY1-2 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 10 | R72 | Positive | Waning | 2022 | 178 | ZB2-2 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 11 | R61 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 179 | M22 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 12 | R62 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 180 | M23 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 13 | R63 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 181 | M25 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 14 | R64 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 182 | M26 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 15 | R65 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 183 | M27 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 16 | R66 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 184 | M30 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 17 | R67 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 185 | M31 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 |

| 18 | R68 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 186 | L30 | Negative | Wenchang | 2021 |

| 19 | R69 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 187 | L32 | Negative | Wenchang | 2021 |

| 20 | R70 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 188 | L33 | Negative | Wenchang | 2021 |

| 21 | R73 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 189 | S40 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 22 | R74 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 190 | S41 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 23 | R75 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 191 | S42 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 24 | R76 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 192 | S43 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 25 | R77 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 193 | S44 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 26 | R78 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 194 | S45 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 27 | R79 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 195 | S46 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 28 | R80 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 196 | S47 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 29 | R81 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 197 | S50 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 30 | R82 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 198 | W11 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 31 | R83 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 199 | W12 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 32 | R84 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 200 | W13 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 33 | R85 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 201 | W14 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 34 | R86 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 202 | W15 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 35 | R87 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 203 | W16 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 36 | R88 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 204 | W17 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 37 | R89 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 205 | W18 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 38 | R90 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 206 | W19 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 39 | W1 | Negative | Waning | 2022 | 207 | W20 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 40 | W2 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 208 | W21 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 41 | W3 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 209 | W22 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 42 | W3-4 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 210 | W23 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 43 | A09 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 211 | W24 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 44 | A12 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 212 | W25 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 45 | A13 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 213 | W26 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 46 | A14 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 214 | W27 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 47 | A16 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 215 | W28 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 48 | A19 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 216 | W29 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 49 | A22 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 217 | W30 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 50 | A24 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 218 | W31 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 51 | A27 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 219 | W32 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 52 | A30 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 220 | W33 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 53 | A31 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 221 | W34 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 54 | A32 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 222 | W35 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 55 | A34 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 223 | W36 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 56 | A36 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 224 | W37 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 57 | A37 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 225 | W38 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 58 | A39 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 226 | W39 | Negative | Wenchang | 2023 |

| 59 | A49 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 227 | B2-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 60 | A50 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 228 | B2-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 61 | A51 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 229 | B2-4 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 62 | A55 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 230 | B2-5 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 63 | A57 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 231 | B2-6 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 64 | A59 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 232 | B2-7 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 65 | A60 | Negative | Wenchang | 2022 | 233 | B2-9 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 66 | B13 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 234 | B4-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 67 | B4 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 235 | B4-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 68 | B17 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 236 | B4-3 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 69 | B20 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 237 | B4-4 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 70 | B21 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 238 | B4-5 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 71 | B23 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 239 | B4-6 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 72 | B24 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 240 | B4-7 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 73 | B25 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 241 | B4-8 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 74 | B27 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 242 | B4-9 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 75 | B30 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 243 | B4-10 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 76 | B31 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 244 | B4-11 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 77 | B32 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 245 | B4-12 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 78 | B33 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 246 | B4-13 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 79 | B37 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 247 | B4-14 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 80 | B41 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 248 | B4-15 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 81 | B44 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 249 | B4-16 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 82 | B46 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 250 | B4-17 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 83 | B47 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 251 | B4-18 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 84 | B49 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 252 | B4-19 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 85 | B53 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 253 | B5-4 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 86 | B54 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 254 | B5-5 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 87 | B56 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 255 | B5-6 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 88 | B57 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 256 | B5-10 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 89 | B61 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 257 | B6-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 90 | B63 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 258 | B6-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 91 | B76 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 | 259 | B6-4 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 92 | C21 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 260 | B6-5 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 93 | C26 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 261 | B6-6 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 94 | C27 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 262 | B6-8 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 95 | C41 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 263 | B6-10 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 96 | C47 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 264 | B6-11 | Negative | Baoting | 2021 |

| 97 | C61 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 265 | F04-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 98 | C68 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 266 | F05-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 99 | C69 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 267 | F05-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 100 | C70 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 268 | F06-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 101 | C73 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 269 | F07-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 102 | C85 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 270 | F022-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 103 | C87 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 271 | F028-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 104 | C89 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 272 | F023-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 105 | C90 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 273 | F035-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 106 | C91 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 274 | F036-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 107 | C95 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 275 | F036-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 108 | C99 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 276 | F037-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 109 | C100 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 | 277 | F037-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 110 | BSL-1 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 278 | F038-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 111 | BSL-2 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 279 | F038-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 112 | BSL-3 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 280 | F039-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 113 | BSL-4 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 281 | F040-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 114 | BSL-5 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 282 | F040-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 115 | BSL-6 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 283 | F041-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 116 | BSL-7 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 284 | F044-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 117 | BSL-8 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 285 | F044-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 118 | BSL-9 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 286 | F045-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 119 | BSL-10 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 287 | F045-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 120 | BSL-11 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 288 | F049-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 121 | BSL-12 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 289 | F055-2 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 122 | BSL-13 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 290 | F099-1 | Negative | Tunchang | 2020 |

| 123 | BSL-14 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 291 | C002-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 124 | BSL-15 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 292 | C007-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 125 | BSL-16 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 293 | C013-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 126 | BSL-17 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 294 | C018Y-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 127 | BSL-18 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 295 | C018Y-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 128 | BSL-19 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 296 | C021-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 129 | BSL-20 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 297 | C023-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 130 | XS-1 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 298 | C026-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 131 | XS-2 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 299 | C026-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 132 | XS-3 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 300 | C031-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 133 | XS-4 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 301 | C048-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 134 | XS-5 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 302 | C064-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 135 | XS-6 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 303 | C065-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 136 | XS-7 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 304 | C071-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 137 | XS-8 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 305 | C072-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 138 | XS-9 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 306 | C076-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 139 | XS-10 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 307 | C077-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 140 | XS-11 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 308 | C078-1 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 141 | LK-1 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 309 | C080-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 142 | LK-2 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 310 | C056-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 143 | LK-3 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 311 | C065-2 | Negative | Qionghai | 2020 |

| 144 | LK-4 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 312 | D008-2 | Negative | Ding’an | 2020 |

| 145 | LK-5 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 313 | D039-1 | Negative | Ding’an | 2020 |

| 146 | LK-6 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 314 | D062-2 | Negative | Ding’an | 2020 |

| 147 | LK-7 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 315 | D093-2 | Negative | Ding’an | 2020 |

| 148 | LK-8 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 316 | ZY2-1 | Negative | Wenchang | 2020 |

| 149 | LK-9 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 317 | 7-4-2 | Negative | Wenchang | 2020 |

| 150 | LK-10 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 318 | 003-2 | Negative | Wenchang | 2020 |

| 151 | LK-11 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 319 | B021-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 152 | LK-12 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 320 | B027-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 153 | LK-13 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 321 | B029-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 154 | LK-14 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 322 | B030-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 155 | LK-15 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 323 | B032-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 156 | LK-16 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 324 | B037-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 157 | LK-17 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 325 | B038-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 158 | LK-18 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 326 | B042-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 159 | LK-19 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 327 | B042-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 160 | LK-20 | Negative | Ding'an | 2023 | 328 | B055-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 161 | I027 | Negative | Qionghai | 2022 | 329 | B059-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 162 | N01 | Negative | Lingshui | 2022 | 330 | B059-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 163 | N06 | Negative | Lingshui | 2022 | 331 | B056-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 164 | N07 | Negative | Lingshui | 2022 | 332 | B056-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 165 | N012 | Negative | Lingshui | 2022 | 333 | B061-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 166 | N013 | Negative | Lingshui | 2022 | 334 | B069-1 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 167 | ZH-40 | Negative | Lingshui | 2022 | 335 | B069-2 | Negative | Baoting | 2020 |

| 168 | NLT | Negative | Lingshui | 2022 | |||||

References

- Kumar, S.N.; Bai, K.V.K.; Rajagopal, V.; Aggarwal, P.K. Simulating coconut growth, development and yield with the infocrop-coconut model. Tree Physiology 2008, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.J.; Gong, M. Current Development status and countermeasures of Arecanut planting and processing industry in Hainan. Chinese Journal of Tropical Agriculture 2019, 39, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Liu, T.; L, J.J.; Chen, J.X. The medical value of areca nut. China Tropical Medicine 2014, 14, 243–245. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.H.; Meng, X.L.; Yu, S.S.; Lin, Z.W.; Niu, X.Q.; Song, W.W.; Qin, W.Q. Forty years of research on “yellow leaf disease of areca palm” in China: New progress of the causal agent and the management. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops 2022, 43, 1010–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.H.; Song, W.W.; Yu, S.S.; Niu, X.Q.; Qin, W.Q. Questions and foresight on the causal agent of Arecanut yellow leaf disease researches and it’s management Plant Protection 2021, 47, 6–11.

- Abeysinghe, S.; Abeysinghe, P.D.; Kanatiwela-de Silva, C.; Udagama, P.; Warawichanee, K.; Aljafar, N.; Kawicha, P.; Dickinson, M. Refinement of the taxonomic structure of 16SrXI and 16SrXIV phytoplasmas of gramineous plants using multilocus sequence typing. Plant Disease 2016, 100, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.X.; Sun, F.S.; Chen, M.R.; Luo, D.Q.; Cai, X.Z. Yellows disease of betel nut palm in Hainan, China. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 1995, 31, 556–558. [Google Scholar]

- Kanatiwela-de Silva, C.; Damayanthi, M.; de Silva, R.; Dickinson, M.; de Silva, N.; Udagama, P. Molecular and scanning electron microscopic proof of phytoplasma associated with areca palm yellow leaf disease in Sri Lanka. Plant Disease 2015, 99, 1641–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.W.; Tang, Q.H.; Meng, X.L.; Song, W.W.; Yu, F.Y.; Huang, S.C.; Niu, X.Q.; Qin, W.Q. Occurrence and distribution of areca pathological yellowing in Hainan, China and Its phytoplasma detection analysis. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops 2022, 43, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, S.; Roshna, O.M.; Soumya, V.P.; Hegde, V.; Suresh Kumar, M.; Manimekalai, R.; Thomas, G.V. Real-Time PCR technique for detection of Arecanut yellow leaf disease phytoplasma. Australasian Plant Pathology 2014, 43, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaithra, M.; Priya, M.; Kumar, S.; Manimekalai, R.; Rao, G. Detection and characterization of 16SrI-B phytoplasmas associated with yellow leaf disease of Arecanut palm in India. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2015, 4, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sumi, K.; Priya, M.; Kumar, S.; Rao, G.; Rao, K. Molecular confirmation and interrelationship of phytoplasmas associated with diseases of palms in South India. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2015, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.K.; Gan, B.C.; Zhang, Z.; Sui, C.; Wei, J.H.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.Q. Detection of the phytoplasmas associated with yellow leaf disease of Areca catechu L. in Hainan province of China by Nested PCR. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin 2010, 26, 381–384. [Google Scholar]

- Che, H.Y.; Wu, C.T.; Fu, R.Y.; Wen, Y.S.; Ye, S.B.; Luo, D.Q. Molecular identification of pathogens from Areca nut yellow leaf disease in Hainan. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops 2010, 31, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Song, W.; Tang, Q.; Meng, X. First Report of 16SrII group-related phytoplasma associated with areca palm yellow leaf disease on Areca catechu in China. Plant Disease 2023, 107, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.S.; Zhu, A.N.; Che, H.Y.; Song, W.W. Molecular identification of ‘Candidatus phytoplasma Malaysianum’-related strains associated with Areca Catechu palm yellow leaf disease and phylogenetic diversity of the phytoplasmas within the 16SrXXXII group. Plant Disease 2024, 108, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.W.; Tang, Q.H.; Long, S.D.; Niu, X.Q.; Liu, F.; Song, W.W. Establishment of Real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR method for detection of areca yellows phytoplasma 16SrI group. Molecular Plant Breeding 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nayar, R.; Seliskar, C.E. Mycoplasma like organisms associated with yellow leaf disease of Areca Catechu L. Forest Pathology 1978, 8, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, G.; Vijayamma Ramakrishnan Nair, P.; Vaganan, M.; Sasikala, M.; Solomon, J.; Nair, G. Microscopic and polyclonal antibody-based detection of yellow leaf disease of Arecanut (Areca Catechu L.). Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 2011, 44, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.L.; Tang, Q.H.; Lin, Z.W.; Niu, X.Q.; Liu, B.; Song, W.W. Developing efficient primers to detect phytoplasmas in areca palms infected with yellow leaf disease. Molecular Plant Breeding 2022, 20, 4624–4633. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.S.; Che, H.Y.; Wang, S.J.; Lin, C.L.; Lin, M.X.; Song, W.W.; Tang, Q.H.; Yan, W.; Qin, W.-Q. Rapid and efficient detection of 16SrI group areca palm yellow leaf phytoplasma in China by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. Journal of Plant Pathology 2020, 36, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Qin, W. Accurate and sensitive detection of areca palm yellow leaf phytoplasma in China by Droplet Digital PCR targeting tuf gene sequence. Annals of Applied Biology 2022, 181, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.W.; Meng, X.L.; Tang, Q.H.; Niu, X.Q.; Song, W.W. Establishment of TaqMan probe real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR detection method for areca palm yellow leaf phytoplasma. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.X.; Zhao, Y.G.; Li, L.; Wu, X.D.; Wang, Z.L. Research progress of recombinant Enzyme Polymerase Amplification (RPA) in rapid detection of diseases. China Animal Health Inspection 2016, 33, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.P.; Wu, W.H.; Zheng, J.L.; Wang, G.H.; He, C.P.; Lin, P.Q.; Huang, X.; Liang, Y.Q.; Yi, K.X. Establishment and optimization of single-tube Nested PCR detection technique for phytoplasma related to sisal purple leafroll disease. Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology 2021, 29(7), 1426–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.W.; Long, S.D.; Meng, X.L.; Tang, Q.H.; Niu, X.Q.; Wang, Y.N.; Song, W.W. Cloning and sequence analysis of tuf, secA and rp genes of areca yellows phytoplasma. Molecular Plant Breeding 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, H.Q.; Zhu, S.F.; Xu, X.; Zhao, W.J. An overview of research on phytoplasma-induced diseases. Plant Protection 2011, 37, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bertaccini, A. Plants and phytoplasmas: when bacteria modify plants. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhao, Y. Phytoplasma taxonomy: nomenclature, classification, and identification. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Liu, B.S.; He, F.T.; Chen, Z.W. Relationship between the seasonal temperature variation and the phytoplasmal amounts in mulberry trees. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 1998, 34, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.W.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Q.L.; Xiao, Z.L.; Li, D.Y.; Zhang, W.Z.; Zhao, W.J. Molecular identification of beggarweed witches′-broom phytoplasma. Plant Quarantine 2019, 33, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.B.; Huang, F.; Tang, Y.F.; Cui, Y.P.; Ling, J.F.; Chen, X. First report of; little leaf disease caused by phytoplasma on Breynia disticha in China. Plant Protection 2024, 50, 272 277+292. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, S.F. Research progress on phytoplasma classification and identification. Plant Quarantine 2020, 34, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.C.; Tian, G.Z. The present status on classification of phytoplasmas. Microbiology China 2008, 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Wu, W.; Tan, S.; Liang, Y.; He, C.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Yi, K. Development of a specific Nested PCR assay for the detection of 16SrI group phytoplasmas associated with sisal purple leafroll disease in sisal plants and mealybugs. Plants 2022, 11, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Hiruki, C. Amplification of 16S rRNA genes from culturable and nonculturable mollicutes. Journal of Microbiological Methods 1991, 14, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, D.E.; Lee, I.M.; Gundersen, D.E.; Lee, I.M. Ultrasensitive detection of phytoplasmas by Nested-PCR assays using two universal primer pairs. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 1996, 35, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A.N.; Yu, S.S.; Su, L.H.; Liu, L.; Song, W.W.; Yan, W. Molecular detection and genetic variation of phytoplasmas from eight plants in garden of areca palm with yellow leaf disease in China. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops 2023, 44, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | Taxonomy | Host plant | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| J069 | 16SrI Group | Areca palm Areca catechu | Wenchang, Hainan |

| S97 | 16SrI Group | Areca palm A. catechu | Wenchang, Hainan |

| T40 | 16SrI Group | Areca palm A. catechu | Wenchang, Hainan |

| H-9 | 16SrI Group | Periwinkle Catharanthus roseus | Wenchang, Hainan |

| A056 | 16SrII Group | Areca palm A. catechu | Wenchang, Hainan |

| W4 | 16SrII Group | Areca palm A. catechu | Wenchang, Hainan |

| MW1-1 | Burkholderia andropogonis | Areca palm A. catechu | Wenchang, Hainan |

| I027 | Areca palm velarivirus 1 | Areca palm A. catechu | Wenchang, Hainan |

| TC-1 | Pantoea ananatis | Areca palm A. catechu | Tunchang, Hainan |

| SHM-1 | 16SrXXXII Group | Trema tomentosa | Qionghai, Hainan |

| PT-1 | 16SrI Group | Paulownia sp. | Taian, Shandong |

| ZF-1 | 16SrIV Group | Jujube Ziziphus jujuba | Taian, Shandong |

| Primer | Primer sequence (5’- 3’) | Annealing temperature (℃) | Target fragment length (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | AAGAATTTGATCCTGGCTCAGGATT | 55 | 1800 | [36] |

| P7 | CGTCCTTCATCGGCTCTT | |||

| R16mF2 | CATGCAAGTCGAACGGA | 50 | 1500 | [37] |

| R16mR1 | CTTAACCCCAATCATCGA | |||

| HNP-1F | TTCTTGTTTTTAAAAGACCT | 44 | 1072 | This study |

| HNP-1R | AAACTTGCGCTTCAGCT | |||

| HNP-2F | TGTGGTCTAAGTGCAAT | 48 | 429 | This study |

| HNP-2R | CTGATAACCTCCACTGTGTT | |||

| HNP-3F | TTCTTGTTTTTAAAAGACCT | 50 | 837 | This study |

| HNP-3R | ATAACCTCCACTGTGTTTCT | |||

| HNP-4F | AATGCTCAACATTGTGATGCT | 48 | 652 | This study |

| HNP-4R | AAACTTGCGCTTCAGCT |

| NO. | Samples | GenBank accession number | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16Sr I-B SubGroup AYLP | FJ998269 | Primer Design/Phylogenetic analysis |

| 2 | 16Sr I-G SubGroup AYLP | FJ694685 | Primer Design/Phylogenetic analysis |

| 3 | 16Sr II-A SubGroup AYLP | OQ586085 | Primer Design |

| 4 | Areca Catechu Chloroplast | NC_050163 | Primer Design |

| 5 | Burkholderia andropogonis | NR_104960 | Primer Design |

| 6 | Pantoea ananatis | MW174802 | Primer Design |

| 7 | Chrysophyllum albidum | LC110196 | Primer Design |

| 8 | Curtobacterium citreum | MF319766 | Primer Design |

| 9 | Curtobacterium luteum | JX437941 | Primer Design |

| 10 | Sphingomonas yantingensis | MF101149 | Primer Design |

| 11 |

Bacillus cereus (Robbsia andropogonis) |

HQ833025 | Primer Design |

| 12 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | CP040883 | Primer Design |

| 13 | Xanthomonas sacchari | MN889285 | Primer Design |

| 14 | Xanthomonas campestris | JX415480 | Primer Design |

| 15 | |||

| 16 | 16SrI-C SubGroup | AF222065 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 17 | 16SrI-D SubGroup | AY265206 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 18 | 16SrI-E SubGroup | AY265213 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 19 | 16SrI-F SubGroup | AY265211 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 20 | |||

| 21 | 16SrII-A SubGroup | L33765 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 22 | 16SrII-B SubGroup | U15442 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 23 | 16SrII-C SubGroup | AJ293216 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 24 | 16SrII-D SubGroup | Y10097 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 25 | 16SrIII-A SubGroup | L04682 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 26 | 16SrIV-A SubGroup | AF498307 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 27 | 16SrV-A SubGroup | AY197655 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 28 | 16SrVI-A SubGroup | AY390261 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 29 | 16SrVII-A SubGroup | AF092209 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 30 | 16SrVIII-A SubGroup | AF353090 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 21 | 16SrIX-A SubGroup | AF248957 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 32 | 16SrX-A SubGroup | AJ542541 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 33 | 16SrXI-A SubGroup | AB052873 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 34 | 16SrXII-A SubGroup | AJ964960 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 35 | 16SrXIII Group | AF248960 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 36 | 16SrXIV-A SubGroup | AJ550984 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 37 | 16SrXV-A SubGroup | AF147708 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 38 | 16SrXVI-A SubGroup | AY725228 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 39 | 16SrXVII-A SubGroup | AY725234 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 40 | 16SrXVIII-A SubGroup | DQ174122 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 41 | 16SrXIX-A SubGroup | AB054986 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 42 | 16SrXX-A SubGroup | X76431 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 43 | 16SrXXI-A SubGroup | AJ632155 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 44 | 16SrXXII-A SubGroup | Y14175 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 45 | 16SrXXIII-A SubGroup | AY083605 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 46 | 16SrXXIV-A SubGroup | AF509322 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 47 | 16SrXXV-A SubGroup | AF521672 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 48 | 16SrXXVI-A SubGroup | AJ539179 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 49 | 16SrXXVII-A SubGroup | AJ539180 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 50 | 16SrXXIX Group | EF666051 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 51 | 16SrXXX-A SubGroup | FJ432664 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 52 | 16SrXXXI Group | HQ225630 | Phylogenetic analysis |

| 53 | 16SrXXXII Group | EU371934 | Phylogenetic analysis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).