1. Introduction

Tropospheric ozone also named ground-level ozone (O

3) is a secondary air pollutant formed by the photochemical oxidation of precursors such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) in the presence of ultraviolet radiation [

1]. These precursors are predominantly emitted from anthropogenic sources [

2,

3].

The complex precursors dynamics together with atmospheric transport processes often result in elevated concentrations observed not only within urban environments, where precursor emissions are high, but also in downwind areas where O

3 pollution can be more pronounced than near the emission sources [

4,

5,

6]. This is due to the long-range transport of ozone and precursors, which undergo photochemical reactions during transit leading to ozone formation and accumulation far from its primary emission source , with a variation that largely depends on geographical characteristics and climatic conditions [

7].

Ozone concentrations exhibit pronounced spatial and temporal variability, following a specific diurnal pattern. Levels typically peak in the afternoon around 16:00 h[

8], especially during summer due to increased photolysis rates, by contrast, winter diurnal cycles are generally less pronounced [

9]. Concentrations progressively decrease, reaching their lowest levels during the night [

6,

10].

In Europe, the highest O₃ levels are observed in the Mediterranean basin and parts of central Europe[

11]. The health impact of ozone exposure depends on duration, concentration [dose] and individual susceptibility. Long-term exposure has been linked to faster decline in spirometry lung function [

12], elevated risk of death from cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, respiratory causes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

13,

14]. Furthermore, a possible association has been identified between ozone exposure and an increased incidence of diabetes [

15,

16,

17], end-stage renal disease and mortality in individuals with chronic kidney disease [

18].

Short-term O₃ exposure can lead to a decrease in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and trigger respiratory symptoms such as coughing, burning sensation, chest tightness, and difficulty breathing [

19]. It is also linked to increased all-cause mortality [

20,

21] and cardiovascular mortality [

22,

23]. Despite a growing body of research on the health effects of ozone worldwide, most previous studies are limited to urban areas, sometimes due to the paucity of air pollutant measurements in rural areas [

24]. Moreover, elevated background ozone levels —especially in northern and eastern Europe— have hindered the identification of consistent trends in urban ozone concentrations, particularly when considering the broader influences of transboundary pollution [

25]. In Spain, several studies including multicenter analyses have examined the health impacts of ozone [

26,

27], but the majority have focused on urban areas or provincial capitals, with relatively little attention paid to suburban and rural areas. In this context, the present study aims to analyze the impact of daily maximum eight-hour ozone concentrations on cause-specific mortality (non-accidental mortality, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality) in suburban and rural areas of Spain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We set up an ecological time-series study conducted from April 1 to September 30, 2017. The study population included residents of 122 municipalities across 43 of Spain’s 52 provinces, based on official population figures as of January 1, 2017. These data were obtained from the municipal registers provided by the National Statistics Institute (INE) [

28], in accordance with Article 17 of the Law on the Basis of Local Government [

29].

The primary outcome was daily mortality, including all-cause natural mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and respiratory mortality, classified using the Spanish version of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). All-cause mortality included all deaths from natural causes (ICD-10: A00–R99). Cardiovascular mortality included all deaths coded under Chapter I (I00–I99), and respiratory mortality included those classified under Chapter J (J00–J99).

Mortality data were aggregated daily for each of the 122 municipalities and covered the study period from April to September 2017. All mortality data were obtained from the INE [

28].

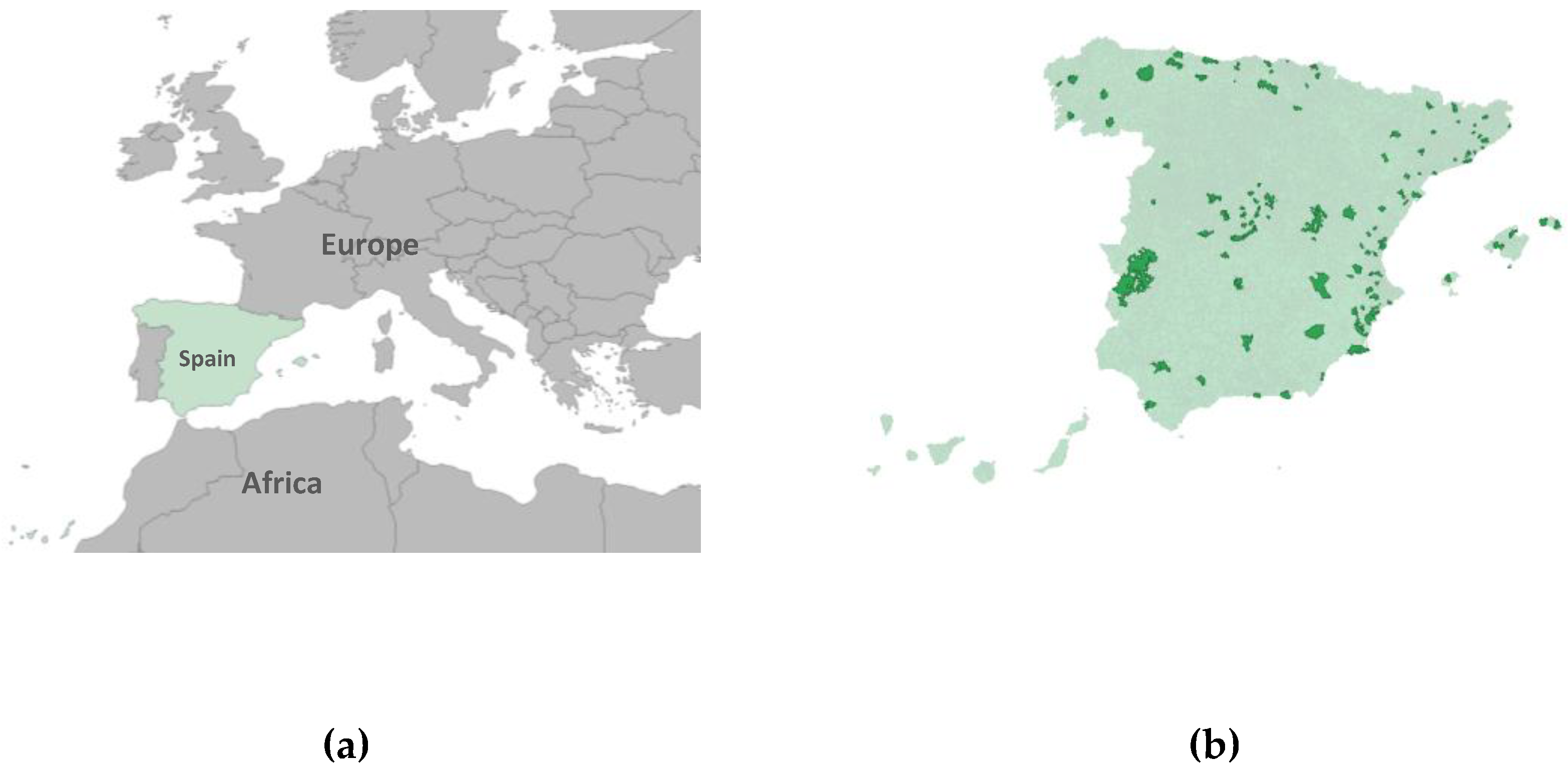

2.2. Ozone Concentration Measures

The independent variable was the daily maximum eight-hour average ozone concentration (µg/m³), measured at air quality monitoring stations located within the selected municipalities (

Figure 1). In accordance with current legislation [

30], monitoring stations are classified by area type: urban, characterized by continuous building structures; suburban, built environments separated by non-urbanized spaces such as small lakes or forests; and rural, which do not meet the criteria for either urban or suburban classifications. Stations are further categorized based on predominant emission sources: traffic stations, where air pollution is primarily influenced by nearby vehicle emissions; industrial stations, located near major industrial emission sources; and background stations, which are not dominated by any specific emission source. In this study, we exclusively included background monitoring stations located in suburban and rural areas.

Ozone concentration data were provided from the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge [

31].

2.3. Control Variables

We included daily maximum temperature, measured in degrees Celsius at provincial level. Previous studies have shown that temperature may influence both air pollutant concentrations and their health effects [

32], particularly in the case of ozone, which tends to peak during periods of high temperatures [

33]. Additionally, province was incorporated as a control variable to account for spatial heterogeneity in demographic, geographic, and socio-economic factors that could affect the observed associations. Meteorological data were obtained from the Spanish Meteorological Agency (AEMET) [

34].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Given that the outcome variable was the daily number of deaths in relation to time-varying covariates, Poisson regression models were employed—using generalized linear models (GLMs)—to assess the association between O₃ concentrations and daily mortality. The effect of air pollution on daily mortality may not be immediate, as it can be delayed by several days[

35,

36]. In the case of ozone, previous studies have shown that its health effects can extend for days following exposure [

21,

27,

37]. Therefore, in addition to incorporating all previously described variables, lag variables were constructed for ozone, covering from day 1 to day 30 prior to the date of death. Models included all previously described covariates (daily maximum temperature and province) and accounted for potential delayed effects by incorporating distributed lag structures. Analyses were conducted separately for each of the three mortality outcomes and stratified by sex. The measure of association estimated in this study was the relative risk (RR), which quantifies the change in mortality risk associated with each unit increase in air pollutant concentration.

The RR was calculated based on an increment of 10 units of the pollutant (10 μg/m³ O₃), using the following formula:

Where “i” denotes the municipality, “j” the day of observation, “k” represents the lag period [days before the event] and “p” refers to the province.

We set statistical significance to a p-value < 0.05. For this analysis, we used the software package R, Version 4.4.1 (2024-06-14).

3. Results

The descriptive analysis showed that, during the study period, a total of 33,397 all-cause deaths were recorded, of which 17,306 occurred in men and 16,091 in women. When stratified by cause, circulatory-cause mortality was higher in women, with 4,749 deaths, compared to 4,243 in men. In contrast, respiratory-cause mortality was more frequent in men, with 2,018 cases, versus 1,586 in women (

Table 1).

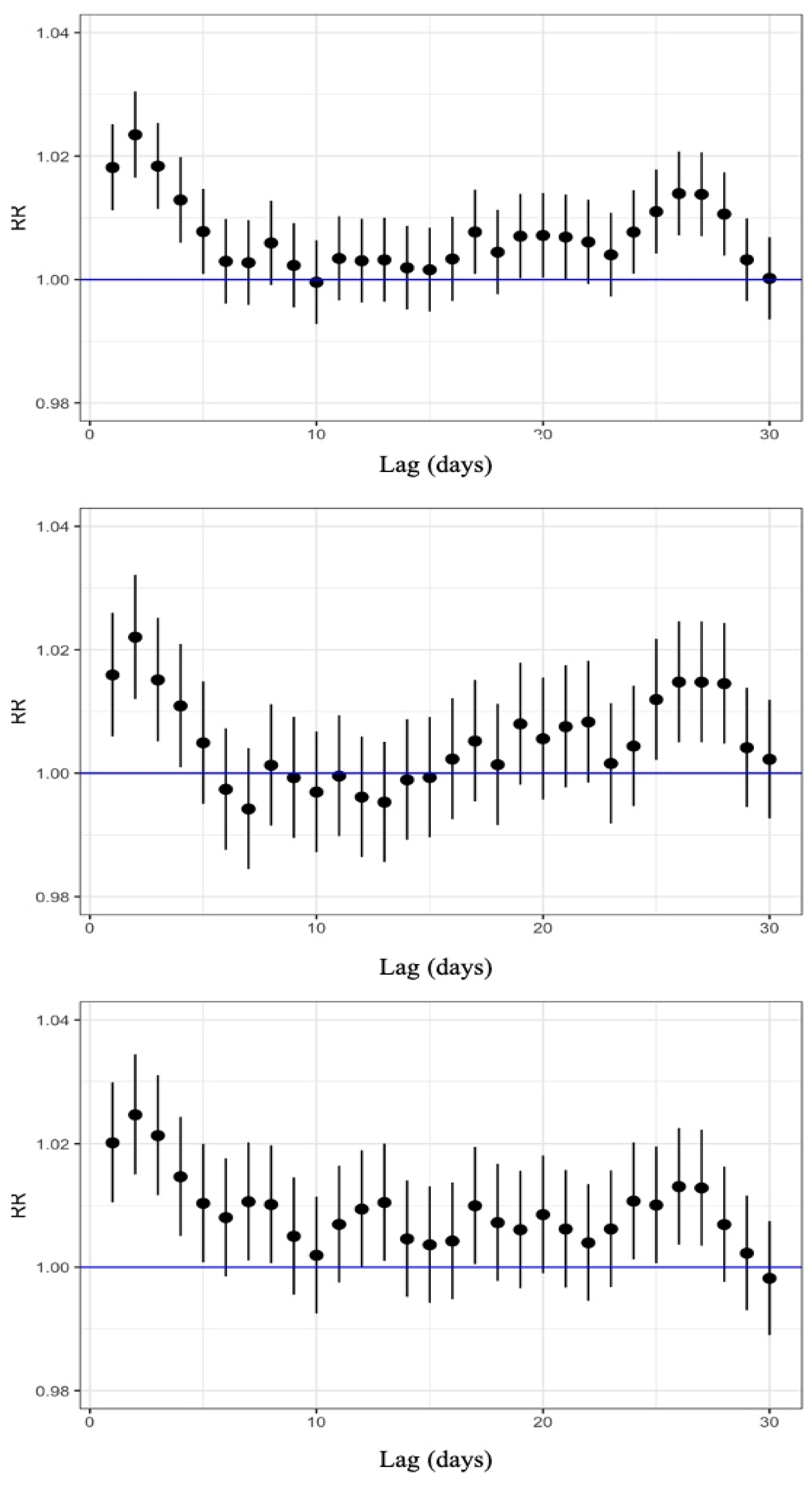

Figure 2 presents the RR and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals based on the Poisson regression modeling for all-cause mortality, stratified by sex. The relationship between ozone concentration and mortality was evaluated across different lag days, ranging from 1 to 30. The results show that, for the total population, a significant increase in all-cause mortality risk was observed from lag1 to lag5, with the maximum effect at lag2, where the RR was 1.023 (95% CI: 1.016–1.030), indicating a 2.3% increase in mortality risk per 10 µg/m³ increase in O₃.

When stratified by sex, both women and men showed the highest risk at lag2. Among women, the RR was 1.022 (95% CI: 1.012–1.032), while among men, the RR was slightly higher, reaching 1.025 (95% CI: 1.015–1.034). All three graphs also indicate an excess risk between lags 24 and 28.

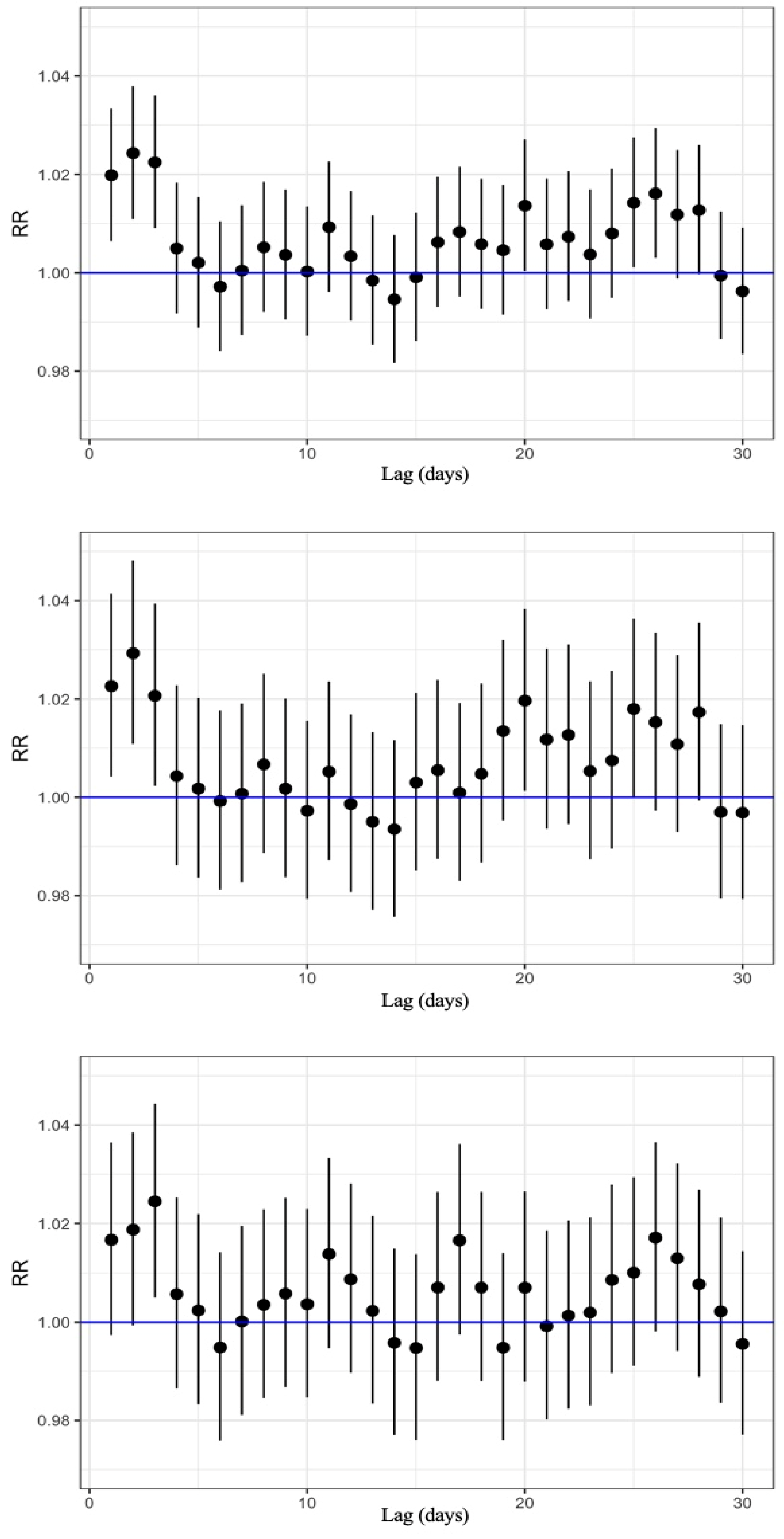

Figure 3 illustrates the association between ozone exposure and cardiovascular mortality. In the total population, a significant increase in mortality risk was observed between lag1 and lag3, with the highest relative risk at lag2 (RR: 1.024; 95% CI: 1.011–1.038).

When analyzing by sex, women also exhibited a significant increase in risk from lag1 to lag3, with the highest RR at lag2, corresponding to a 2.9% increase in cardiovascular mortality per 10 µg/m³ increase in O₃ (95% CI: 1.011–1.048). Among men, however, a statistically significant association was only observed at lag3 (RR: 1.024; 95% CI: 1.005–1.044). This could indicate a variable response to ozone exposure or reflect the complexity of factors influencing cardiovascular diseases in this population.

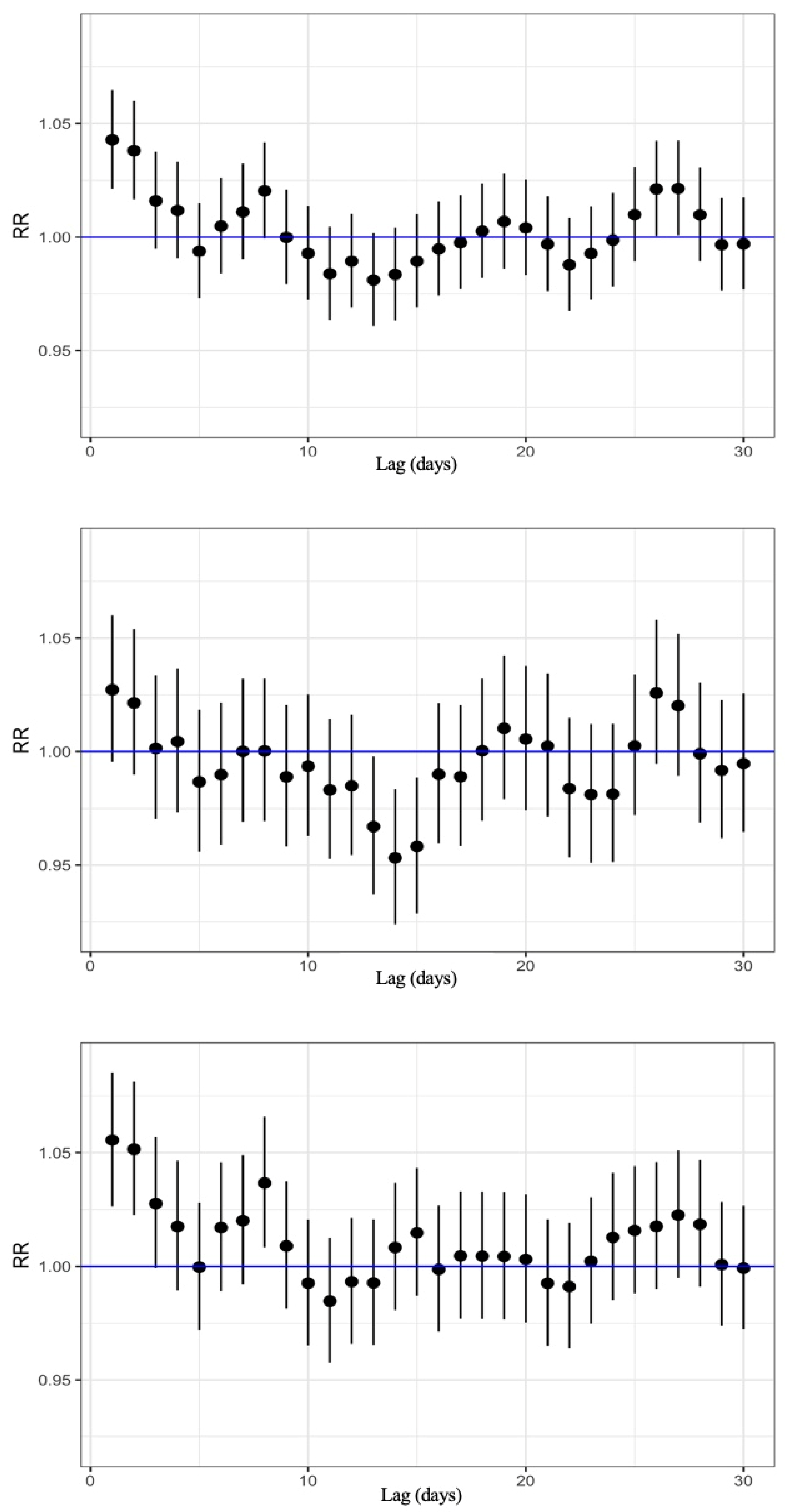

Finally,

Figure 4 presents the association between ozone exposure and respiratory mortality. For the total population, the highest relative risk was observed at lag1, with an RR of 1.043 (95% CI: 1.021–1.065). This finding suggests that immediate exposure to O3 has a significant impact on respiratory-related deaths. In sex-stratified analyses, the highest risk was also found at lag1 for both men and women. Among women, the RR was 1.027 (95% CI: 0.995–1.060), whereas in men, the association was stronger, with an RR of 1.055 (95% CI: 1.027–1.085), suggesting higher susceptibility to respiratory effects of ozone exposure. It is important to note that significant associations were concentrated on the day immediately preceding death (lag1). However, a secondary increase in risk was observed between lags 24 and 28, consistent with the pattern seen for cardiovascular mortality, which may be due to cumulative effects of ozone exposure or confounding seasonal or environmental factors.

4. Discussion

In this ecological time-series study, we investigated the relationship between maximum 8-hour ozone concentrations and daily mortality, including all-causes, circulatory and respiratory causes, in suburban and rural areas of Spain during the period from April to September 2017. The results show a significant association between ozone exposure and daily mortality, with the strongest effects observed in the days immediately preceding death. Additionally, elevated relative risks between lags 24 and 28 days prior to death, suggest both immediate and short-term effects of ozone on mortality.

Recent studies have confirmed the significant relationship between ozone exposure and non-accidental mortality [

38,

39]. One study conducted in 95 urban areas in the United States found a significant association between short-term ozone exposure and all-cause mortality, reporting that a 10-ppb increase in daily ozone levels of the previous week corresponded to a 0.52% (95% posterior interval, 0.27%-0.77%) increase in daily mortality [

21]. This finding aligns with our results, where a 2.3% increase of daily total mortality per 10 µg/m³ increase in ozone concentration was observed.

Cardiovascular mortality followed a similar pattern. Few studies have specifically studied the underlying biological mechanisms explaining the cardiovascular effects of ozone such as platelets activation and blood pression increase[

40], acute changes in inflammation, fibrinolysis, and endothelial cell function [

41]. A previous meta-analysis estimated that the pooled relative risk for cardiovascular mortality for each 10 µg/m3 increment in ozone concentration was 0.068 % (95% CI: 1.0049-1.0086)[

42], lower than our estimate of 2,4% (95% CI: 1.011–1.038).

Our findings also revealed a significant increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular mortality at lag 2 in both the total population and among women, while in men, it peaked at lag 3. This temporal pattern differs slightly from previous studies, which have reported a significant increase in circulatory-cause mortality for a 10-μg/m

3 increase in ozone concentration in lag 0-1[

43]. Regarding respiratory-cause mortality, this study showed that the highest relative risk was observed at lag 1 in the overall population, with an RR of 4,3 % (95% CI: 1.021–1.065), suggesting that short-term exposure to ozone has a significant impact on respiratory mortality. These findings are in line with previous studies that have consistently reported associations between short-term ozone exposure and increased respiratory mortality [

44], though some studies have failed to find significant associations [

22,

45]. Ozone exposure is known to trigger acute airway inflammation, and exposure to 0.10 ppm ozone has been shown to result in significant increases in inflammatory markers and protein levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, as well as impaired phagocytic function of alveolar macrophages via the complement receptor [

46].

It is essential to consider the inherent complexity in comparing studies conducted in different regions, due to variations in population characteristics, ozone exposure and environmental conditions. For instance, demographic structure, prevalence of pre-existing diseases, and health-related behaviors may differ substantially between different countries. Given the regional variability in ozone precursor emissions and the higher sensitivity of low-latitude areas, it is essential to consider the geographic distribution and evolving trends of ozone sources when designing air quality policies [

47].

A notable finding is the increase in RR observed between lags 24 and 28 days prior to death for all three causes of death. This pattern is not yet widely documented in literature and may be explained by the cumulative damage caused by ozone exposure.

A key strength of our study is to consider the ambient air quality data provided by suburban and background Air Quality monitoring facilities distributed throughout the country to ensure an accurate representation of regional ozone exposure, minimizing the bias that can result from relying on a single station that represent large areas . Furthermore, our focus on suburban and rural areas provides a more comprehensive and precise assessment of background ozone exposure across diverse populations and limits the confusion with urban pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide. The statistical models were adjusted for meteorological variables and stratified by province, thereby reducing the risk of confounding and enhancing the validity of the findings

However, several limitations should be recognized. First, the ecological study design inherently limits the ability to establish definitive causal relationships. Second, although adjustments were made for several control variables, unmeasured confounding factors may still influence the observed associations.

In addition, while our analysis examined the association between ozone levels and all-cause, circulatory and respiratory mortality, we lacked detailed data on tobacco use prevalence within the study population. Tobacco consumption is a well-established risk factor for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, as well as for various types of cancer [

48,

49]. The absence of this variable may affect the precision of our estimates, as tobacco is a major contributor to mortality from these causes. Without information on variations in tobacco consumption, we were unable to adequately adjust our models for this potential confounder, which may result in either an overestimation or underestimation of the effects of ozone exposure on mortality.

Finally, our analysis focused exclusively on ozone as a pollutant, without accounting for the potential influence of other environmental pollutants. This may limit the broader understanding of the cumulative health and ecological impacts of air pollution.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings indicate a potential association between daily ozone concentrations and daily mortality, with short-term effects. These results underscore the urgent need for rapid and effective interventions to mitigate ozone exposure and safeguard public health. The implementation of stringent environmental policies and the promotion of health-conscious behaviors can substantially contribute to the reduction of mortality linked to air pollution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R. and M.D.; methodology, R.R.; formal analysis, M.D.; data curation, J.R.M.F and M.D; writing—original draft preparation, M.D..; writing—review and editing, ALL; visualization, M.D; supervision, R.R.; funding acquisition, B.N.C and R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by European Union H2020, grant number 945391 and Horizon 101157269.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE)

www.ine.es

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| INE |

National Statistics Institute [Instituto Nacional de Estadística] |

| ICD |

International Classification of Diseases |

| AEMET |

Spanish Meteorological Agency [Agencia Estatatal de Meteorología] |

References

- Moeini, O.; Tarasick, D. W.; McElroy, C. T.; Liu, J.; Osman, M. K.; Thompson, A. M.; et al. Estimating Wildfire-Generated Ozone over North America Using Ozonesonde Profiles and a Differential Back Trajectory Technique. Atmos. Environ. X 2020, 7, 100078. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.; Fang, Z. Ozone Pollution: A Major Health Hazard Worldwide. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2518. [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.; Lupascu, A.; Nalam, A. Attribution of Ground-Level Ozone to Anthropogenic and Natural Sources of Nitrogen Oxides and Reactive Carbon in a Global Chemical Transport Model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20 [17], 10707–10731.

- Qu, K.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, X.; Vrekoussis, M.; Kanakidou, M.; et al. The Effect of Cross-Regional Transport on Ozone and Particulate Matter Pollution in China: A Review of Methodology and Current Knowledge. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174196. [CrossRef]

- Holloway, T.; Fiore, A.; Hastings, M. G. Intercontinental Transport of Air Pollution: Will Emerging Science Lead to a New Hemispheric Treaty? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37 [20], 4535–4542. [CrossRef]

- García, M. Á.; Villanueva, J.; Pardo, N.; Pérez, I. A.; Sánchez, M. L. Analysis of Ozone Concentrations between 2002–2020 in Urban Air in Northern Spain. Atmosphere 2021, 12 [11], 1495. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.-H.; Lin, C.; Vu, C.-T.; Cheruiyot, N. K.; Nguyen, M. K.; Le, T. H.; Lukkhasorn, W.; Vo, T.-D.-H.; Bui, X.-T. Tropospheric Ozone and NOx: A Review of Worldwide Variation and Meteorological Influences. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102809.

- European Environment Agency. Annex 2. Phenomenology of Ozone Concentrations. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/c1i92-9167-123-1/page008.html [accessed March 31, 2025].

- Petetin, H.; Thouret, V.; Athier, G.; Blot, R.; Boulanger, D.; Cousin, J.-M.; Gaudel, A.; Nédélec, P.; Cooper, O. Diurnal Cycle of Ozone Throughout the Troposphere over Frankfurt as Measured by MOZAIC-IAGOS Commercial Aircraft. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2016, 4, 000129. [CrossRef]

- Bernier, C.; Wang, Y.; Estes, M.; Lei, R.; Jia, B.; Wang, S. C.; Sun, J. Clustering Surface Ozone Diurnal Cycles to Understand the Impact of Circulation Patterns in Houston, TX. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124 [23], 13457–13474. [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Europe’s Air Quality Status 2023. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/europes-air-quality-status-2023/europes-air-quality-status2023 [accessed March 31, 2025].

- Zhao, T.; Markevych, I.; Fuertes, E.; de Hoogh, K.; Accordini, S.; Boudier, A.; et al. Impact of Long-Term Exposure to Ambient Ozone on Lung Function over a Course of 20 Years [The ECRHS Study]: A Prospective Cohort Study in Adults. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 34, 100729. [CrossRef]

- Jerrett, M.; Burnett, R. T.; Pope, C. A., III; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.; Krewski, D.; Shi, Y.; Calle, E.; Thun, M. Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360 [11], 1085–1095. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C. C.; Hayes, R. B.; Ahn, J.; Shao, Y.; Silverman, D. T.; Jones, R. R.; García, C.; Bell, M. L.; Thurston, G. D. Long-Term Exposure to Ozone and Cause-Specific Mortality Risk in the United States. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200 [8], 1022–1031. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, R.; Xu, Z.; Jin, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, T.; Wei, J.; Huang, J.; Li, G. Long-Term Exposure to Ozone and Diabetes Incidence: A Longitudinal Cohort Study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151634. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q.; Meng, X.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Su, X.; Huang, Y.; et al. Long-Term Low-Level Ozone Exposure and the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Glycemic Levels: A Prospective Cohort Study from Southwest China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 293, 118028. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X.; Bigambo, F. M.; Snijders, A. M.; et al. The Effect of Ambient Ozone Exposure on Three Types of Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Environ. Health 2023, 22 [1], 32. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Huh, H.; Mo, Y.; Park, J. Y.; Jung, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, D. K.; Kim, Y. S.; Lim, C. S.; Lee, J. P.; Kim, Y. C.; Kim, H. Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Large Cohort Study. BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25 [1], 74. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Health Effects of Ozone in the General Population. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ozone-pollution-and-your-patients-health/health-effects-ozone-general-population [accessed April 1, 2025].

- Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M.; Sera, F.; Liu, C.; Armstrong, B.; Milojevic, A.; Guo, Y.; et al. Short Term Association between Ozone and Mortality: Global Two Stage Time Series Study in 406 Locations in 20 Countries. BMJ 2020, 368, m108. [CrossRef]

- Bell, M. L.; McDermott, A.; Zeger, S. L.; Samet, J. M.; Dominici, F. Ozone and Short-Term Mortality in 95 US Urban Communities, 1987–2000. JAMA 2004, 292 [19], 2372–2378. [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Chen, R.; Wang, L.; Meng, X.; Liu, C.; Niu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; You, J.; Zhou, M.; Kan, H. Ambient Ozone Pollution and Daily Mortality: A Nationwide Study in 272 Chinese Cities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125 [11], 117006. [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Dahlquist, M.; Lind, T.; Ljungman, P. L. S. Susceptibility to Short-Term Ozone Exposure and Cardiovascular and Respiratory Mortality by Previous Hospitalizations. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 37. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ma, Y.; Liu, R.; Shao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, L.; Jing, Y.; Bell, M. L.; Chen, K. Associations between Short-Term Ambient Ozone Exposure and Cause-Specific Mortality in Rural and Urban Areas of Jiangsu, China. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 113098. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.; Drysdale, W. Urban Ozone Trends in Europe and the USA [2000–2021]. EGUsphere 2025, 2024–3743.

- Ballester, F.; Sáez, M.; Daponte, A.; Ordóñez, J. M.; Taracido, M.; Cambra, K.; et al. El proyecto EMECAS: Protocolo del estudio multicéntrico en España de los efectos a corto plazo de la contaminación atmosférica sobre la salud. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2005, 79 [2], 229–242.

- Díaz, J.; Ortiz, C.; Falcón, I.; Salvador, C.; Linares, C. Short-term effect of tropospheric ozone on daily mortality in Spain. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 187, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE]. Instituto Nacional de Estadística – INE. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ [accessed April 1, 2025].

- Ley 7/1985, de 2 de abril, Reguladora de las Bases del Régimen Local. Boletín Oficial del Estado, núm. 80, 3 de abril de 1985, pp. 8945–8964. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1985-5392 [accessed April 2, 2025].

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades [CIE-10]. Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ [accessed April 2, 2025].

- Real Decreto 102/2011, de 28 de enero, relativo a la mejora de la calidad del aire. Boletín Oficial del Estado, núm. 25, 29 de enero de 2011, pp. 9574–9613. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2011-1645 [accessed April 2, 2025].

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico; Gobierno de España: Madrid, España. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es.html [accessed April 3, 2025].

- Coates, J.; Mar, K. A.; Ojha, N.; Butler, T. M. The Influence of Temperature on Ozone Production under Varying NOx Conditions – A Modelling Study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16 [18], 11601–11615.

- Zhang, X.; Waugh, D. W.; Kerr, G. H.; Miller, S. M. Surface Ozone-Temperature Relationship: The Meridional Gradient Ratio Approximation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49 [13], e2022GL098680. [CrossRef]

- Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Agencia Estatal de Meteorología - AEMET. Gobierno de España. Available online: https://www.aemet.es/es/portada [accessed April 3, 2025].

- Chiusolo, M.; Cadum, E.; Stafoggia, M.; Galassi, C.; Berti, G.; Faustini, A.; Bisanti, L.; Vigotti, M. A.; Dessì, M. P.; Cernigliaro, A.; Mallone, S.; Pacelli, B.; Minerba, S.; Simonato, L.; Forastiere, F.; EpiAir Collaborative Group. Short-Term Effects of Nitrogen Dioxide on Mortality and Susceptibility Factors in 10 Italian Cities: The EpiAir Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119 [9], 1233–1238. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Fei, F.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, X.; Zhong, J.; et al. Short-Term Effects of Fine Particulate Matter Constituents on Mortality Considering the Mortality Displacement in Zhejiang Province, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 457, 131723. [CrossRef]

- Stafoggia, M.; Bellander, T. Short-Term Effects of Air Pollutants on Daily Mortality in the Stockholm County—A Spatiotemporal Analysis. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109854. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhou, L.; Chen, X.; Bi, J.; Kinney, P. L. Acute Effect of Ozone Exposure on Daily Mortality in Seven Cities of Jiangsu Province, China: No Clear Evidence for Threshold. Environ. Res. 2017, 155, 235–241. [CrossRef]

- Ozone and Daily Mortality Rate in 21 Cities of East Asia: How Does Season Modify the Association? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180 [7], 729–739. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/aje/article-abstract/180/7/729/149673?redirectedFrom=fulltext [accessed April 4, 2025].

- Day, D. B.; Xiang, J.; Mo, J.; Li, F.; Chung, M.; Gong, J.; et al. Association of Ozone Exposure With Cardiorespiratory Pathophysiologic Mechanisms in Healthy Adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177 [9], 1344–1353. [CrossRef]

- Mirowsky, J. E.; Carraway, M. S.; Dhingra, R.; Tong, H.; Neas, L.; Diaz-Sanchez, D.; Cascio, W.; Case, M.; Crooks, J.; Hauser, E. R.; Dowdy, Z. E.; Kraus, W. E.; Devlin, R. B. Ozone Exposure Is Associated with Acute Changes in Inflammation, Fibrinolysis, and Endothelial Cell Function in Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Environ. Health 2017, 16 [1], 126. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Su, W.; Wang, H.; Li, N.; Song, Q.; Liang, Q.; Sun, C.; Liang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Song, E. J.; Sun, Y. Short-Term Exposure to Ambient Ozone and Cardiovascular Mortality in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2023, 33 [10], 958–975. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, T.; Sun, Q.; Shi, W.; He, M. Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Short-Term Exposure to Ozone and Cause-Specific Mortality Risks and Thresholds in China: Evidence from Nationally Representative Data, 2013–2018. Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107666. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lu, K.; Fu, J. A Time-Series Study for Effects of Ozone on Respiratory Mortality and Cardiovascular Mortality in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Cortes, T. R.; Silveira, I. H.; Oliveira, B. F. A. de; Bell, M. L.; Junger, W. L. Short-Term Association Between Ambient Air Pollution and Cardio-Respiratory Mortality in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLOS ONE 2023, 18 [2], e0281499. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, R. B.; McDonnell, W. F.; Mann, R.; Becker, S.; House, D. E.; Schreinemachers, D.; et al. Exposure of Humans to Ambient Levels of Ozone for 6.6 Hours Causes Cellular and Biochemical Changes in the Lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1991, 4 [1], 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; West, J. J.; Emmons, L. K.; Flemming, J.; Jonson, J. E.; Lund, M. T.; et al. Contributions of World Regions to the Global Tropospheric Ozone Burden Change From 1980 to 2010. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48 [1], e2020GL089184.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. About Tobacco Use and Prevention. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/index.html [accessed April 6, 2025].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).