1. Introduction

Air pollution has various health effects on humans. Traditionally, it is assumed that air pollutants are mainly related to respiratory diseases. This stems from a simple situation: humans breathe polluted air, and various pollutants enter the body, primarily affecting the lungs. Therefore, diseases related to the respiratory system are most commonly studied in relation to air quality. However, the presence of pollutants in the body can lead to various diseases [

1,

2]. The spectrum of health aspects affected by air pollution is broad. In fact, almost all health conditions can be impacted. Additionally, air quality influences human behavior, as well as pregnancy outcomes and the health of new-borns [

3,

4,

5,

6].

When studying the impact of short-term exposures to air pollution, acute health incidents are examined. Typically, these are situations that result in a visit to a doctor, an emergency department (ED) visit, hospitalization, morbidity, or in some cases, even sudden death. This work considers ED visits and the diagnosed medical reasons for these visits. It is assumed that the visits are random, in the sense that they are not pre-planned or scheduled. Of course, the number of visits fluctuates throughout the year due to seasonal variations, time trends, epidemics, or other factors. Typically, constructed statistical models take these phenomena associated with temporal changes into account [

7]. These models incorporate the level of air pollution concentration and weather factors, usually temperature and humidity. Such models help determine whether the considered air pollution is associated with a particular disease.

Human health is threatened by environmental factors, including air pollution. The hypothesis here is that every aspect of health may respond to pollution. This is supported by numerous current publications that provide such examples. Additionally, some human behaviors are dictated by reactions to pollution. It has been shown that the nervous system reacts to dirty air, which can lead to often atypical behavior or reactions in individuals [

4].

Overall, this approach assumes that human health is a system of various health connections. A harmful factor acts on this system. Determining which aspect of health will be most affected or will respond is usually difficult to predict. It significantly depends on the individuals, their health status, condition, and vulnerabilities. Thus, the hypothesis here is that every aspect of health may be impacted by pollution and its related factors [

1].

This view is presented through the lens of air pollution. The issue arises from the fact that a person lives in a place, in an environment where the air is polluted. This air pollution concentration influences the type of health impairment.

In this paper, 12 health groups are considered based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes. In total, emergency department visits are analyzed as a measure of human health status [

2].

The study presented here is a meta-analysis. We do not use raw data, which consisted of values related to air pollution, weather parameters, and, most importantly, health. For each day of the study, this group of three characteristics provided input data for constructing statistical models. It is worth emphasizing that the models applied allow for efficient computations, even for large datasets. In particular, they handle the temporal progression of these values with ease, from seasonal variations to trends and periodicity.

Time control in the applied statistical models involves analysing ED visits in clusters based on calendar structure (year, month, day of the week). Thus, time is “divided” into segments of 4, and occasionally 5, days.

The data used in this study consist of a pair of values derived from a statistical model: the coefficient for a given air pollutant and its standard error. These values are estimated for a large number of considered coordinates. For example, for a specific coordinate defined as follows: patient group (boys under 11 years old), air pollutant (ozone), exposure (3 days before the ED visit, lag 3), the estimated coefficient is 0.0022, and its standard error is 0.0009. Additionally, a specific p-value threshold can be adopted, which enables the identification of statistically significant relationships at the chosen level. This approach allows for the categorization of results and the identification of relationships.

The study conveys a straightforward message: it examines all classifications of ED visits for individual air pollutants, their lags, and defined strata. The obtained values enable the identification of relationships between air pollutants and health outcomes. In other words, we perform large-scale computations and then look for meaningful associations.

2. Materials and Methods

This work presents the results on the short-term exposure and acute impact of ambient air pollutants on various disease groups in the urban area of the city of Toronto, Canada. The period of the study was defined by the available data resulting in a period from April 2004 to December 2015. Statistical models were developed to estimate the relative risk of an emergency department visit in the relation to ambient air pollution concentration levels. These models were constructed for eight air pollutants (lagged from 0 to 14 days) and for 18 strata. The strata were defined based on sex (all, male, female) of the patients and their age group. In addition, the data were categorized by season; a whole period (January – December), warm (April – September), and cold (October – March).

Twelve disease groups defined by the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) were used as health classifications in the models [

8]. The results were collected in matrices composed of 18 rows (strata) and 15 columns (lags) for each air pollutant and separately for each of the 12 health classifications. The matrix cells contain the coefficient of the fitted regression (Beta) and its standard error (SE). These two values allow to determine the statistically significant associations. They could be positive or negative. Also, the results could have statistically non-significant associations. A p value < 0.05 was assumed statistically significant. The numerical values obtained from the models are provided for each air pollutant. For each air pollutant there are 270 estimated and tested values.

The data on six ambient air pollutant concentrations as carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO

2), ozone (O

3), sulphur dioxide (SO

2), daily maximum 8-h ozone (O

3H8), and fine particulate matter (PM

2.5), where the particles are not greater than 2.5μm in diameter were collected [

9].

In addition, the air quality health index (AQHI) was calculated. Its value bases on three air pollutants: NO

2, O

3, and PM

2.5. The coefficients used in the formula are determined on risk of mortality in large Canadian cities [

10]. Another index, designated here as AQHIX, was also generated. In its calculation, the concentration of O

3 is replaced with the concentration of O

3H8. As the AQHI index is an amalgamate of three air pollutants, this index construction allows emphasis of the presence of ozone in multi-pollutant exposures.

Statistical models based on the case-crossover (CC) design were constructed [

7]. In the realization of the CC approach, the time-stratified technique to identify control periods for cases was applied [

11]. Conditional logistic regression is usually realized, where health events are considered as individual and separate ED visits. In this work, events were grouped and represented as the number (counts) of daily ED visits. In such approach, conditional Poisson regression models were constructed for daily counts [

12,

13,

14]. The calendar hierarchical structure was applied to control “time”. In such approach time trends and seasonal fluctuations are well controlled by the realized design. The hierarchical clusters were constructed using the scheme “year: month: day of week”. Thus, each cluster contains 4 or 5 days. The weather factors, temperature and relative humidity were represented in the form of natural splines. Air pollution concentrations were lagged, from 0 to 14 days. In the same way were lagged the weather factors.

The main results from the used models are the estimated slope (Beta) and its standard error (SE). These values allow to calculate the relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The risks are estimated for an increase of air pollution concentration levels. It can be reported for an assumed fixed measure (say 10 units). Very often it is reported for a one interquartile range (IQR) change in concentrations. For example, the calculations are performed as follow for an IQR increase

The value of 95% CI, its lower and upper boundary, is calculated according to the simple formulae

These three values (RR, 95%CI) are usually used and reported to assess an impact of air pollutant on human health.

The second part of the method presented in this study involves the following approach. The RR (Relative Risk) is calculated for a given air pollutant and an assumed dose (e.g., 10 units or IQR). Consequently, for each lag value, there are 18 RR values along with their corresponding 95% CI. These values are calculated for the entire population, as well as subgroups such as men, women, children, and different seasons (warm, cold).

For a given lag, only one value among the 18 calculated RRs is considered. This value is taken as a representative and can be the mean, median, minimum, maximum, or one of the quartiles Q1 (25%) or Q3 (75%). This approach enables the examination of relationships between air pollutants and ED visits. For a set of 15 values (lags 0–14) and the selected representative RR values along with their lower and upper 95% CI bounds, a model is fitted. This model is determined using the least squares method and is nonlinear. From the observed relationships (Figure 5), it is evident that a suitable representative function is of the form:

Here, the variable x represents the lag value, which ranges from 0 to 14 days. This is a cubic polynomial function. Its coefficients are estimated using the chosen model and the nlsML procedure in the R language. As mentioned earlier, the data contain 18 values for each argument x. These values can be represented by a single value such as their mean, median, minimum, maximum, or one of the quartiles. This also applies to the bounds of the 95% CI. Overall, this approach yields the trajectory of RR in relation to lag.

3. Results

The results are presented in the form of graphs. It is possible to generate many of such illustrations. The estimated coefficients (Beta) and their standard error (SE) for the examined air pollution have been tabulated. The tables containing these values are stored as a database and are freely accessible. Simple calculations with them, using Beta and SE, allow determining RR values and their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Descriptive data on ambient air pollutants and meteorological conditions on a daily basis, collected in Toronto, Canada between April 1, 2004 and December 31, 2015 are presented in another publication (Table 3) [

15]. The presented here analyses were done using the statistical software R, and one of its tools to create graphics, ggplot [

16].

Table 1 shows the set of disease groups used in this study. The classification is according to ICD-10 codes. It also presents the number of diagnosed ED visits.

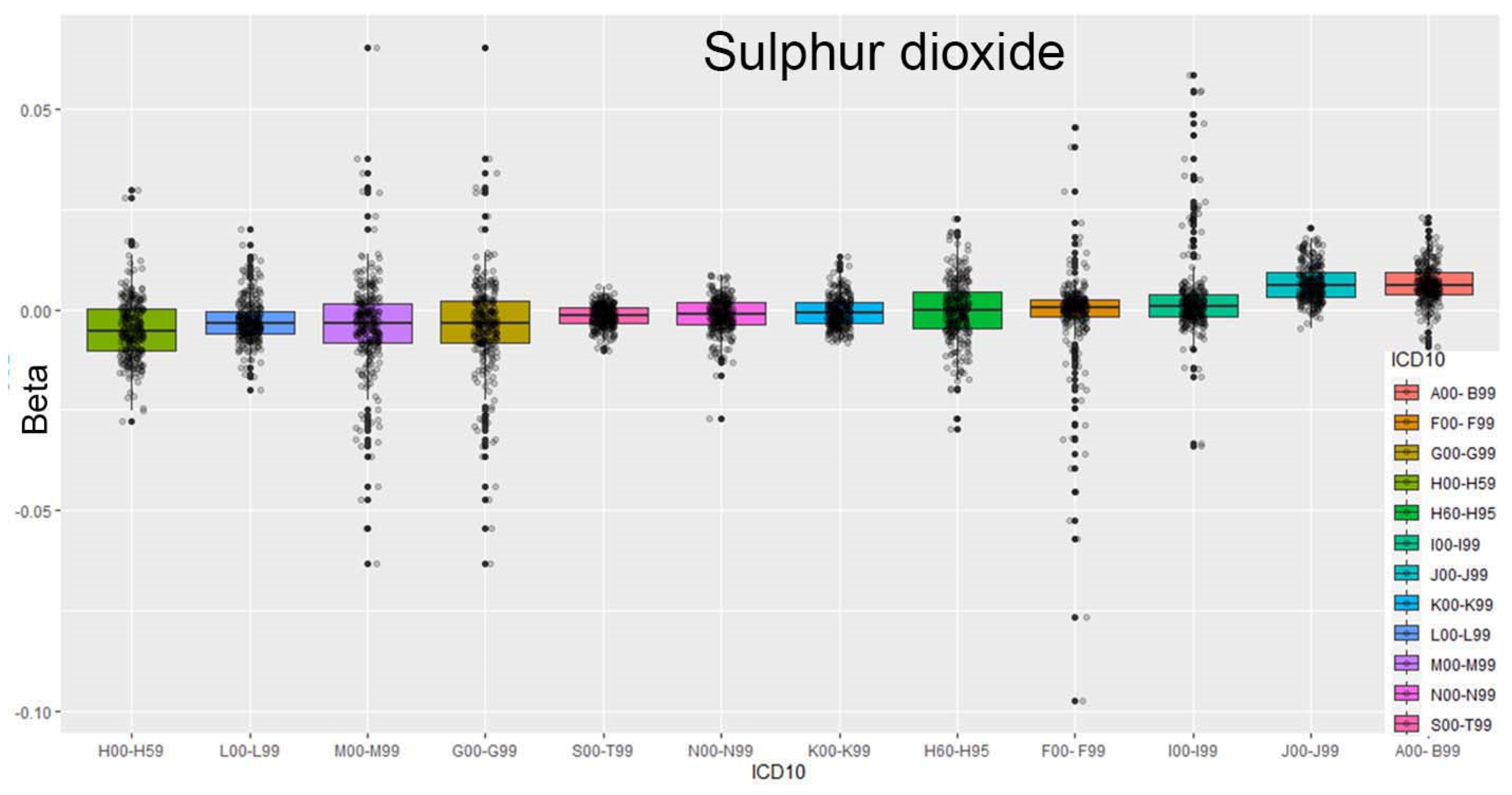

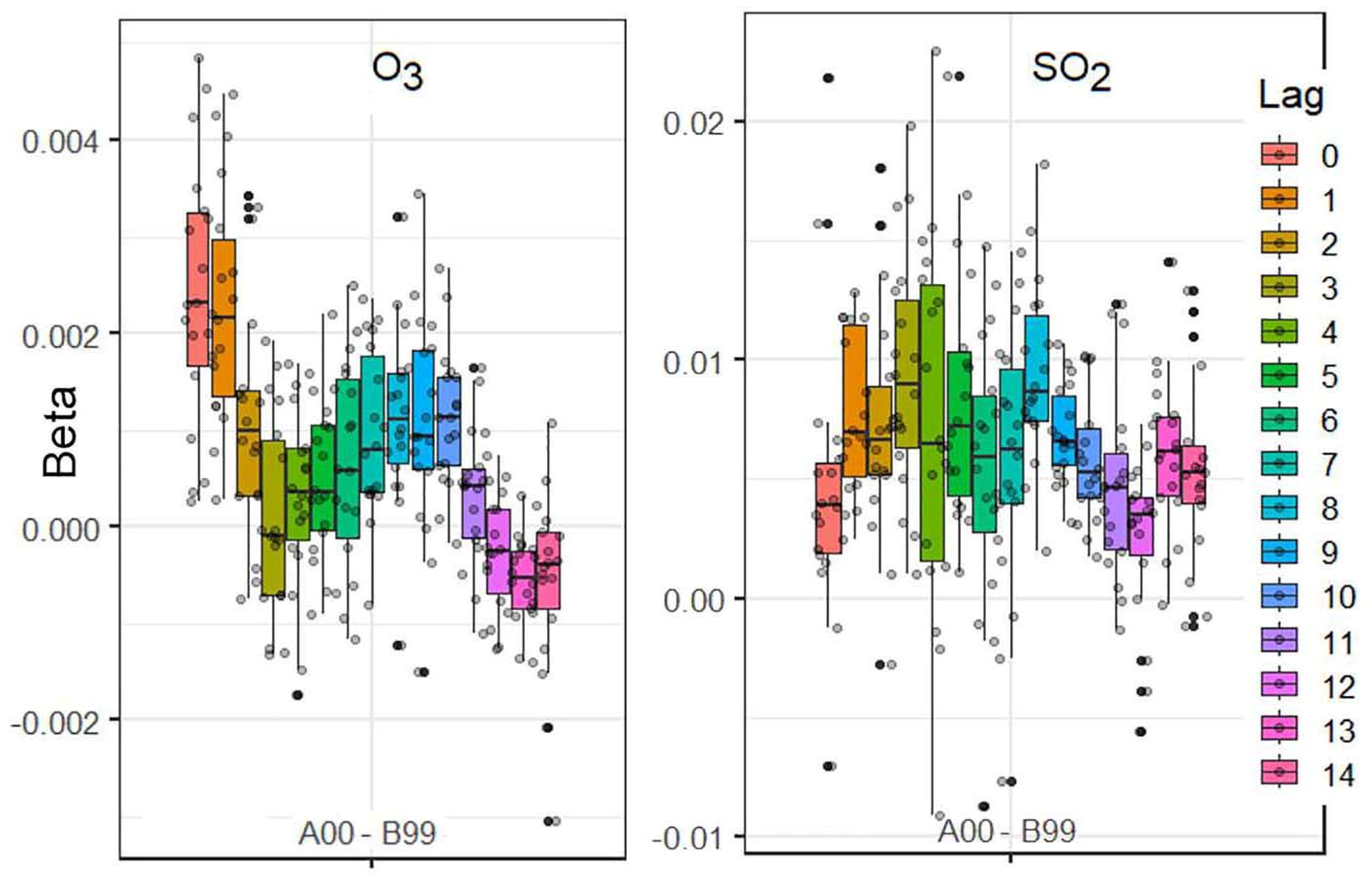

For each air pollutant, it is easy to create a plot to observe potential relationships. For example,

Figure 1 shows the situation for sulphur dioxide. It presents in the form of a box plot displaying the values of the three quantiles (Q1 = 25%, Q2 = 50%, and Q3 = 75%). Values outside of these are shown as outliers. In this case, the order was established between ICD-10 codes based on Q2.

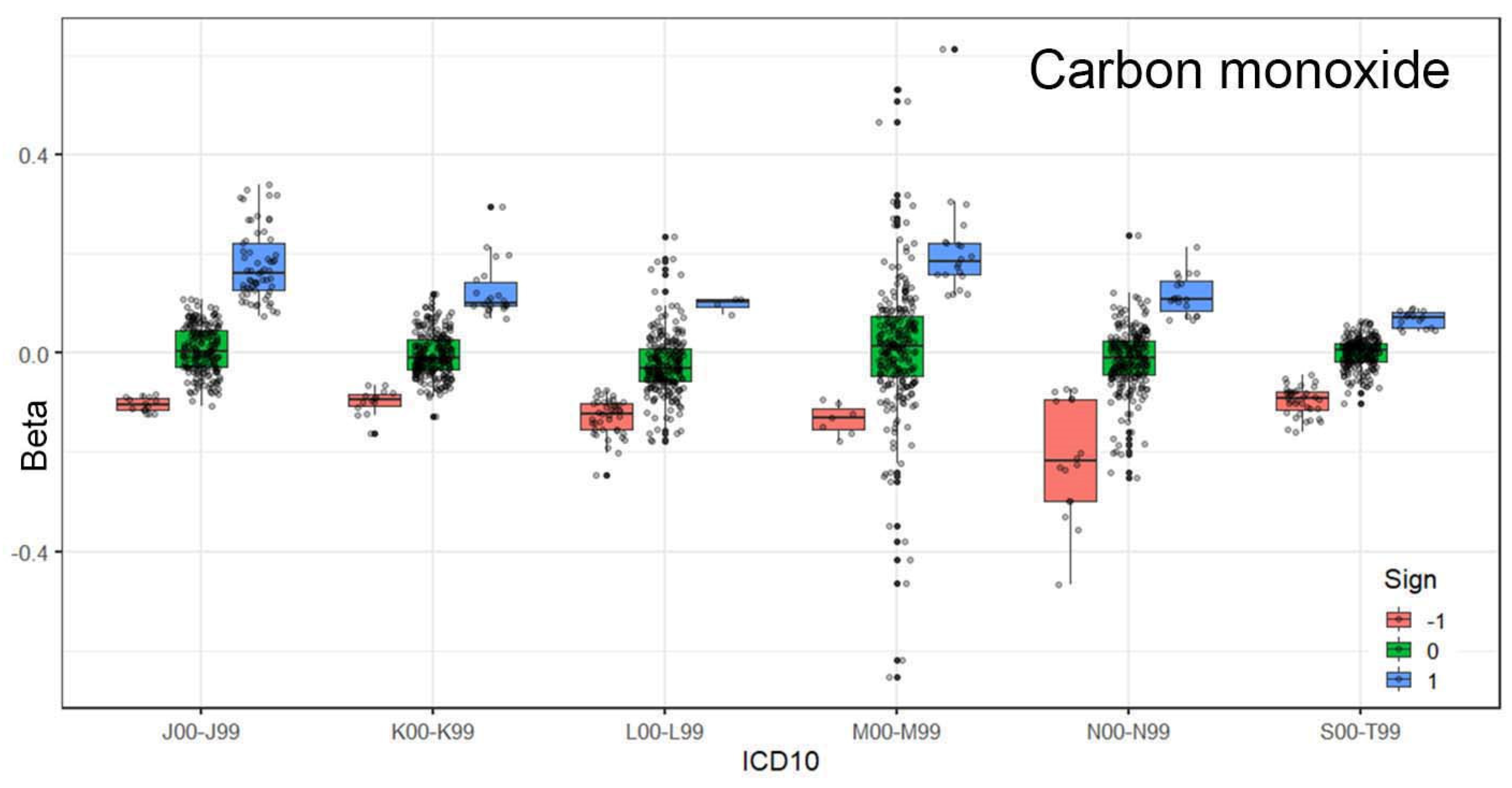

Figure 2 shows the relationships for carbon monoxide. The result is shown for three situations: when the relationship is statistically significant positive (1), negative (-1), or no relationship (0). Here, the relationship between exposure to carbon monoxide and respiratory diseases is visible.

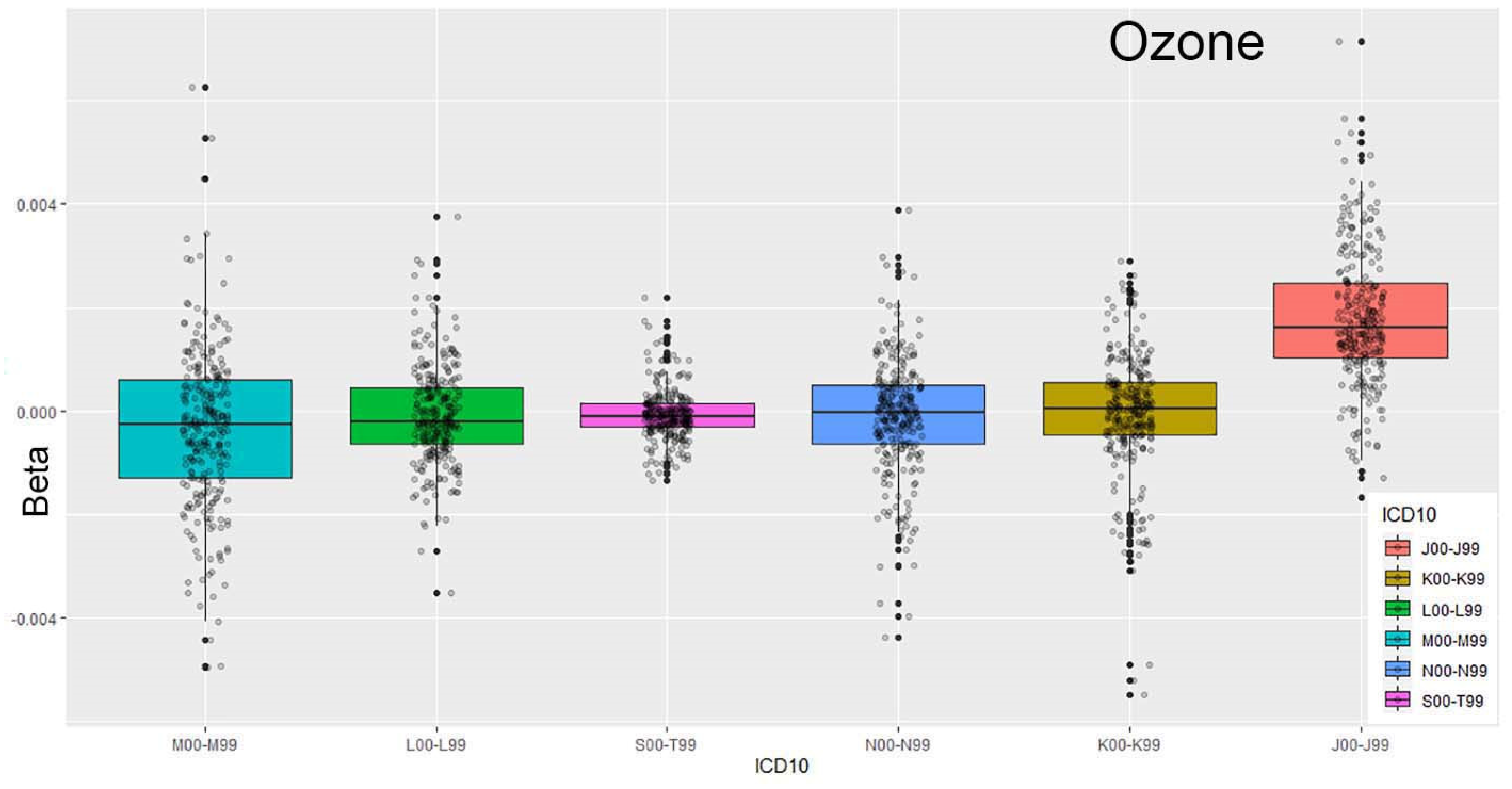

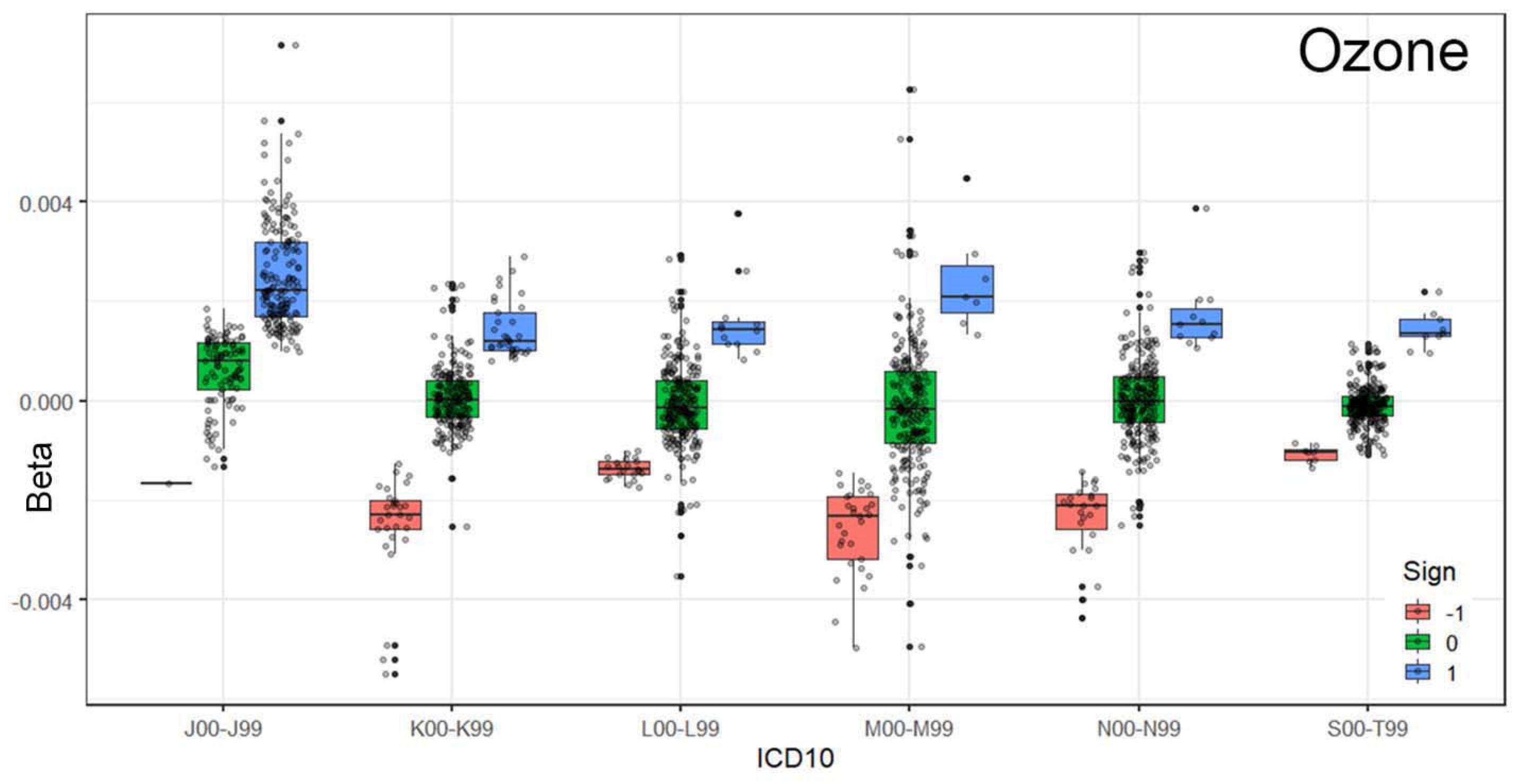

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the relationships between the respiratory system and exposure to ozone concentration in the environment. The arrangement of ICD-10 codes based on the median (Q2) shows a strong relationship between ozone and ED visits for respiratory issues.

This is confirmed by grouping the coefficients according to their statistical relationships (-1, 0, and 1). As shown in

Figure 4, among the tested relationships, the statistically significant positive ones stand out.

The data used in this study, which, it is worth noting, are derived from statistical models, allow us to observe numerous relationships. For a given air pollutant, we consider 15 lags (lag 0–14 days). For each lagged exposure, there are 18 strata, resulting in 18 pairs of values (Beta, SE).

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of the obtained Beta values for ED visits classified under A00–B99, which, according to the description, correspond to “Certain infectious and parasitic diseases.”

For ozone, a strong association (Beta>0) is observed at lags 0, 1, 2, and subsequently at lags 8, 9, and 10. In contrast, the relationship for exposure to sulfur dioxide exhibits a different pattern. This example demonstrates how the proposed approach can effectively capture various dependencies. The use of strata allows for the selection of different subgroups of ED visits, making the results more reliable.

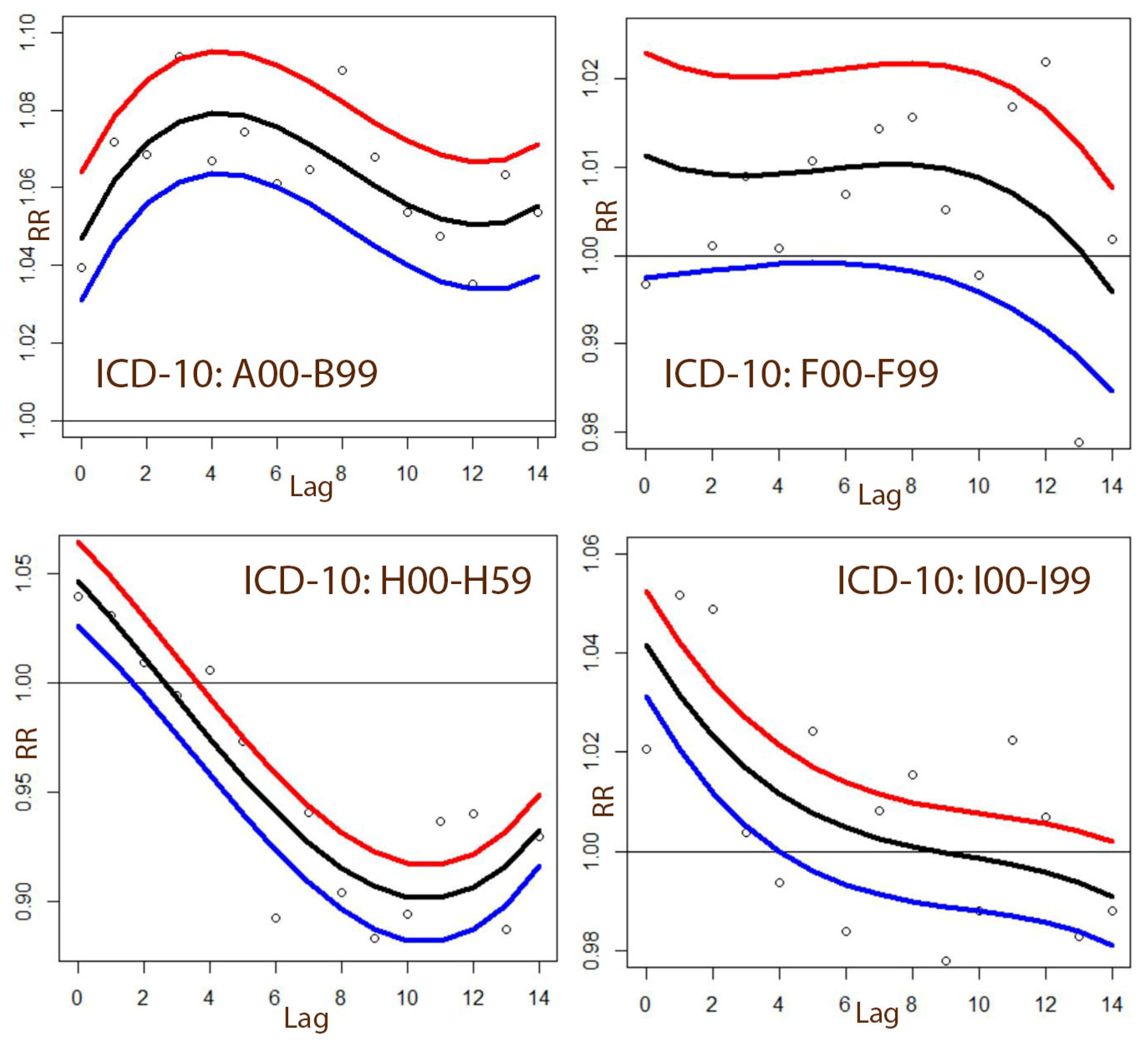

Figure 6 consists of four panels. It shows the relative risk (RR) for a 10-unit increase in sulfur dioxide concentration for four ED vista classifications. It illustrates how different the effects are on specific health categories. The black line represents the RR, the blue line shows the lower bound, and the red line shows the upper bound. The median of these values was used, specifically the median of 18 RR values and their lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence intervals. As a result, an analytical formula for RR as a function of lag, i.e., previous exposure to air pollution, is derived. The data used, the R language program, and example results are provided in the following location: szyszkowiczm/TorontoEDAirMetaAnalysis. This allows for verification of the presented results and also gives the possibility of obtaining the coefficients for the RR model as a function of lag.

4. Discussion

One of the main findings of this study is the demonstration of a strong connection between respiratory diseases and exposure to air pollution. High concentrations of air pollution are associated with respiratory diseases. This confirms results and observations that have been published previously over many years [

17,

18,

19]. Ozone has proven to be the most influential gas in terms of the number of ED visits related to respiratory diseases. Carbon monoxide also shows strong associations with this type of visit, suggesting that urban air is a major contributor to the worsening of respiratory conditions.

The result presented in

Figure 1 is also very interesting. It shows a link between infectious diseases and the presence of sulphur dioxide. The available data allows for various perspectives on the relationships between ED visits and specific pollutants.

Of course, more detailed results can be obtained by considering individual strata within the defined categories. For instance, one can take a closer look at the relationships for children, the elderly, or by seasonal variations.

A weak point of this study is that not all ED visits were considered, specifically not all 22 ICD-10 classifications. Naturally, many diseases are clearly not linked to air quality. For such diseases, the results should be in the 0 category. The proposed approach can capture other relationships and serve as a method verification. For example, pre-arranged ED visits (e.g., for chemotherapy) should show no correlation.

This study addresses several key issues related to research on the impact of air pollution on health. It can be summarized as follows. It is assumed that there is good access to databases related to air quality and meteorological factors such as temperature, humidity, and others. Of course, having accurate health data is crucial. In this case, we refer to properly diagnosed emergency visits. Having extensive data over a long period, such as several years, is highly beneficial for obtaining reliable results.

Currently used statistical methods are highly effective. The application of the time-stratified case-crossover method allows for consistent control of time-related changes, such as seasonal, trend, and other variations. Thus, the computational process does not pose a significant challenge.

This study proposes analyzing all disease groups. In other words, calculations should be performed for all ICD-10 categories. As a result, one obtains a cube of results with components (stratum, air pollution/lag, ICD-10 code). This set of results enables a comprehensive exploration of the relationships and impact of air pollution on health. It breaks the preconceived notion that air pollution affects only the respiratory system. In different centers, cities, or regions, this impact may vary significantly. Conducting such calculations will put an end to surprises regarding the associations between health and air quality.

It is known that certain visits are unrelated to air pollution. Therefore, pre-scheduled visits should demonstrate independence in the calculations. Such results serve as a test of the reliability of the conducted study.

The study offers several further research perspectives. The presented data for Toronto can be explored in greater depth and detail. One approach could involve focusing on specific patient groups (e.g., women over 60 years old). Another aspect is the potential to provide a “summary” result, as is common in meta-analyses. This could mean reporting a unified risk value for a particular disease in relation to an air pollutant.

However, the main strength of this study lies in its proposition to investigate all health categories. This approach enables a more precise identification of relationships between air pollutants and health outcomes. It represents a “top-down” perspective, starting from the general (ED visits for all classifications). So far, research has predominantly adopted a “bottom-up” approach, beginning with specific cases (e.g., ED visits for asthma).

5. Conclusions

A broad perspective on the harmfulness of air pollution allows us to recognize significant connections. The impact of ozone on the human respiratory system is well-known [

20]. This relationship has been clearly demonstrated through the applied approach. It is evident that the connection is strong. It turns out that inhaled air serves as a wide entry point for pollutants into the body. The thesis presented in this study suggests that a health response can occur through any system in the human body. Behavior and its consequences (such as injuries) are also associated with poor air quality. It seems reasonable to conduct similar studies in other centers and locations

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MS. and WJ; methodology, MS.; software, MS.; validation, MS., and WJ.; formal analysis, MS.; investigation, MS.; resources, MS.; data curation, MS.; writing—original draft preparation, MS.; writing—review and editing, MS. and WJ.; visualization, MS.; supervision, MS.; project administration, MS.; funding acquisition, MS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI was used to verify language editing and grammar. AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schraufnagel, D.E.; Balmes, J.R.; Cowl, C.T.; et al. Air pollution and noncommunicable diseases: a review by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies’ Environmental Committee, Part 2: Air Pollution and Organ Systems. Chest. 2019, 155(2):417–426.

- Szyszkowicz, M.; De Angelis, N. Ambient air pollution and emergency department visits in Toronto, Canada. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2021, 28, 28789–28796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendzerska, T.; Szyszkowicz, M.; Saymeh, M.; et al. Air pollution, weather and positive airway pressure treatment adherence in adults with sleep apnea: a retrospective community-based repeated-measures longitudinal study. Journal of Sleep Research. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szyszkowicz, M.; Thomson, E.M.; de Angelis, N.; et al. Urban air pollution and emergency department visits for injury in Edmonton and Toronto, Canada. Hygiene and Environmental Health Advances. 2022, 4, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszkowicz, M. Urban Air Pollution and Emergency Department Visits Related to Pregnancy Complications. European Journal of Rhinology and Allergy. 2022, 5(2), 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszkowicz, M.; Lukina, A.; Dinu, T. Urban air pollution and emergency department visits for neoplasms and outcomes of blood forming and metabolic systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19(9), 5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclure, M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol 1991, 133, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NACRS. The National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, CIHI, Canada. Canada. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-ambulatory-carereporting-system-metadata (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- NAPS Web site. Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/air-pollution/monitoring-networks-data/national-air-pollution-program.html (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Stieb, D.M.; Burnett, R.T.; Smith-Doiron, M.; et al. A new multipollutant, no-threshold air quality health index based on short-term associations observed in daily time-series analyses. J AirWaste Manage Assoc. 2008, 58(3):435–450.

- Janes, H.; Sheppard, L.; Lumley, T. (2005) Case-crossover analyses of air pollution exposure data: referent selection strategies and their implications for bias. Epidemiology. 2005, 16:717–726.

- Szyszkowicz, M. Use of generalized linear mixed models to examine the association between air pollution and health outcomes. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2006, 19:224–227.

- Armstrong, B.G.; Gasparrini, A.; Tobias, A. (2014) Conditional Poisson models: a flexible alternative to conditional logistic case crossover analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014, 14:122. [CrossRef]

- Szyszkowicz, M. Use of two-point models in “Model choice in time-series studies of air pollution and mortality”. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2020, 13:225–232.

- Lukina, A.O.; Burstein, B.; Szyszkowicz, M. Urban air pollution and emergency department visits related to central nervous system diseases. PLOS. 2022.

- R Core Team (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R. 2023, Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Brugha, R.; Grigg, J. Urban air pollution and respiratory infections. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2014, 15(2):194-9.

- Adamkiewicz, G.; Liddie, J.; Gaffin, J.M. The Respiratory Risks of Ambient/Outdoor Air Pollution. Clin Chest Med. 2020, 41(4):809-824.

- Jędrychowski, W. Ambient air pollution and respiratory health in the east Baltic region. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999, 25 Suppl 3:5-16.

- Szyszkowicz, M. Cardiopulmonary mortality and temperature. Environmental Pollution and Protection. 2017, 2(1), 32–38. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).