1. Introduction

Phytate makes up more than 85% of total phosphorus in oilseeds and cereal grains and is the main organic phosphorus storage form in plants[

1]. Non-ruminant animals like pigs and poultry eat diets high in phytate-phosphorus, which is poorly digested as they do not produce the enzyme phytase that degrades phytic acid[

2]. Phytate can complex with protein at low pH (stomach) and bind with divalent metal cations at high pH (intestine) which makes these nutrients less available to the animal[

3]. Besides being an antinutritional molecule for monogastric animals, it can also cause eutrophication[

4].

Phytase can catalyze the removal of inorganic phosphate from phytate along with the bound nutrients[

5]. As non-ruminants lack the enzyme, adding exogenous phytase to the feed can enhance nutrition availability, thus enhancing growth and less eutrophication[

6]. Exogenous phytase addition in feed can also exert a positive effect on the immune system, intestinal microbiota, and antioxidant status[

7]. There are several types of phytases from several sources and they have some advantages over each other[

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Phytases from

Bacillus species are Beta-propeller phytase (BPP) as opposed to the usual commercial phytase from fungal or other bacterial sources which are mostly histidine acid phosphatases (HAP). Although BPP has in general less activity than HAP, they have the advantage of having strict substrate specificity for phytate only (thus unlike HAP, it avoids ATP, GTP and NADH) and being inherently thermostable (so it can withstand the necessary industrial feed pelleting process)[

14,

15]. Nevertheless, partly due to inefficient enzyme prodction methods,

Bacillus phytases have not been applied on a large scale [

16].

The global market size for phytase is valued at 547.74 million in 2022 and is predicted to reach 949.96 million by the year 2031[

17]. In Bangladesh however, phytases are not locally produced, but rather imported[

18] which increases the cost and causes less use of phytase in poultry feed. Also, the long transportation hinders the enzyme’s shelf life and activity. And if these are not thermostable enough they lose significant activity when going through the industrial feed pelleting processes. So, thermostable phytase production from an indigenous strain inside the country can address these issues in Bangladesh.

So, this study focused on 1. Isolating and identifying phytase-producing indigenous bacteria 2. Production optimization of its phytase using both statistical (placket-burman and central composite design) and classical (change one factor at a time) approaches and 3. characterization of the crude enzyme.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

Soil samples were collected from three different poultry farms in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Samples were immediately taken to the enzyme and fermentation biotechnology laboratory, at the University of Dhaka, and preserved in dry and cool conditions until processing.

2.2. Isolation of Phytase-Producing Bacteria

To isolate the phytase-producing bacteria from these samples, approximately 1g of soil was suspended in 0.85% saline up to 10 mL. Diluted samples (10-4 or 10-5) were then spread onto the Phytate Specific Medium (PSM) Plate adapted from Howsan et al.[

19] (glucose 15.0 g/l, NH

4NO

3 5.0 g/l , Na-phytate 5.0g/l, CaCl2 0.3g/l, MgSO4 0.5g/l, MnSO4 0.01g/l, FeSO4 0.01g/l and 1.5% agar, pH adjusted to 6) and incubated at 37

oC for 3 days. PSM plates were later observed for the clear zones of hydrolysis around the colonies which indicates the production of extracellular phytase. A clear zone around the colony was evaluated by the plate detection method described by Bea et al.[

20] using cobalt chloride and ammonium molybdate/ammonium vanadate solution.

The zone ratio was calculated to determine the efficiency of phytate degradation in PSM plates[

21] using the formula:

2.3. Quantitative Screening of Phytase-Producing Bacteria

The bacteria showing clear zone on the PSM were selected for further evaluation of their capacity to produce enzyme in liquid medium. Submerged fermentation was carried out in the 250 ml flask containing 50 ml of Phytase Production Medium (PPM- same composition as PSM without agar) with 5% inoculum size for 3 days at 37ºC and 120 rpm. The inoculum was prepared by taking a loopful of colonies from the plates and inoculating them into 5 mL TSB broth. At 24-hour intervals the phytase activity was measured.

2.4. Phytase Assay

For phytase assay, the method used in this experiment was adopted from Bea et al. [

20], which is based on the detection of inorganic phosphate. The cell-free supernatant (CFS) was collected by centrifugation of the fermented broth at 10,000g for 10 minutes. Phytase activity was determined by incubating 300µl of the enzyme solution (CFS) with 1.2 ml of substrate solution [0.2%(w/v) sodium phytate (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0] for 30 min at 37

oC. The reaction was stopped by adding 1.5 ml of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid. From this mixture, 1.5 ml was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 1.5 ml ammonium molybdate ferrous sulfate mixture, which had been prepared by mixing 4 volumes of 1.5% (w/v) ammonium molybdate (Merck, Germany) in 5.5% sulfuric acid (Merck, Germany) with 1 volume of 2.7% (w/v) ferrous sulfate solution. The production of phosphomolybdate was measured spectrophotometrically at 700 nm. From the phosphate standard curve, the amount of liberated Phosphate per ml was found and the enzyme activity was calculated (U/mL). One U is defined as the activity that releases 1 μmol of inorganic phosphate from 0.2% (w/v) sodium phytate per minute at pH 5 and 37

oC.

2.5. Identification of SP11 Isolate

Morphological, Microscopic, and various Biochemical tests [Kligler Iron Agar (KIA), citrate utilization , Motility Indole Urease (MIU), Methyl Red- Voges Proskauer (MR-VP), Starch hydrolysis] were determined for the presumptive identification of the SP 11 strain.

To confirm the identification, 16s rDNA sequencing was performed. Total DNA was prepared from isolates using the technique described by Bravo et al.[

22]. 16s rDNA (1465 bp) was PCR amplified using Universal primers, 27F (Forward Primer: 5’AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG3’) and 1492R (Reverse Primer: 5’CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT3’), using a thermocycler (annealing Temperature 50

oC). PCR products were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using a purification kit (ATPTM Gel/PCR Fragment DNA Extraction Kit). Purified PCR products were sequenced by chain termination method from DNA Solution Lab, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Bio Edit Sequence Alignment Editor and Mega 7.0 software were used for sequence alignments and the construction of phylogenetic trees respectively.

2.6. Detection of Full-Length Gene Encoding Phytase

DNA was isolated by the method described previously. Related sequences were collected from NCBI and primers with overhangs (for later cloning) were designed using MEGA to amplify a 1200 bp phytase gene. The primers were analyzed with OligoAnalyzer. Phyt.CD S-F: 5'-GGATCCATGAAGGTTCCAAAAACAATGCTGC-3' (Tm¬=61oC) and Phyt.CD S-R: 5'-CTCGAGCTAGCCGTCAGAACGGTCTTTCA-3' (Tm=63.5oC). PCR was performed (each step had 30 seconds for 35 cycles) to obtain the amplicon having an annealing temperature of 58oC.

2.7. Single Factor Analysis

The effect of inoculum size, incubation temperature, pH, and shaking speed on phytase production by Bacillus subtilis SP11 was evaluated by changing a single factor at a time. Fermentation was done using various inoculum sizes (1%, 5%, 10%), temperatures (30oC, 37oC and 42oC), media pH (3, 4, 5, 6, control, 7, 8, 9, 10), and shaking speed (0, 60, 120, 180)

2.8. Plackett-Burman Design (PBD)

PBD was used to evaluate the effect of different media components on phytase production. 19 factors. These are: 7 cheap raw materials for carbon, nitrogen, and mainly for phytate sources (Rice bran, Wheat bran, Soybean meal, Corn meal, mustard meal, Linseed Meal and Sesame Meal), 4 carbon sources [ raw (cane molasses) and organic (glucose as rapid metabolizing and sucrose and citrate as slow metabolizing)], 3 nitrogen sources [inorganic (ammonium nitrate) and organic (Tryptone and yeast extract)], 1 phosphate sources (K2HPO4), and 4 mineral sources (CaCl2, MgCl2, FeSO4, MnSO4). Each factor had 2 levels: high level (+ 1) and low level (− 1), as shown in Table.

24 experimental runs were done and the responses were expressed by the first-order model as shown in Equation:

where Y represents the response variable, ß

0 is the interception coefficient and ßi is the coefficient of the linear effects of the 19 independent variables (X1 – X19)

2.9. Central Composite Design (CCD)

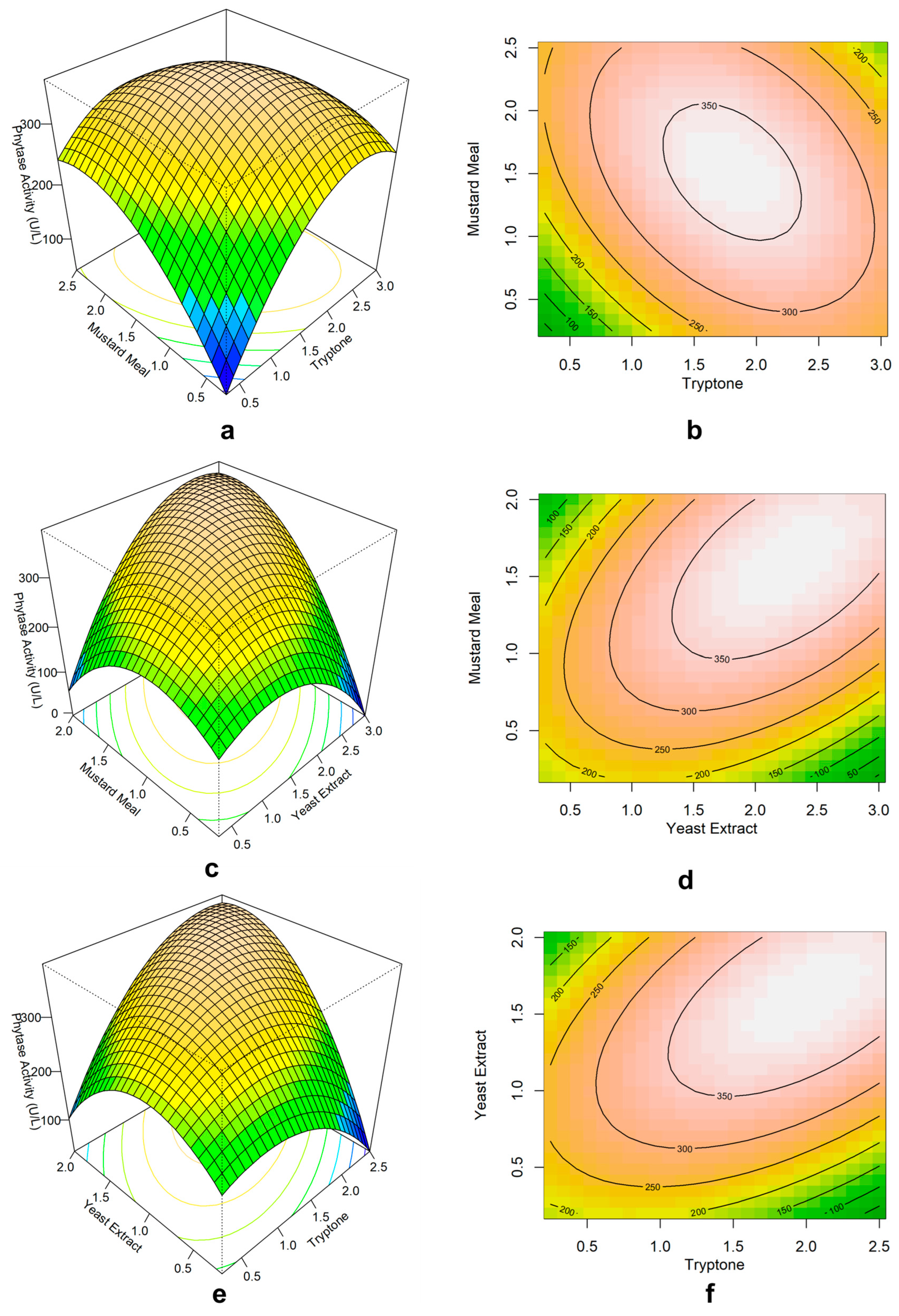

CCD was used to determine the optimum levels of three positive significant factors identified in the placket-Burman Design (Mustard Meal, tryptone, and Yeast Extract) and to study the interactions among them for maximum phytase production. Each variable had five levels: two axial (-α, +α), two cube points (-1,+1), and a center point (0) where α is 1.68. 20 experimental runs were conducted with center points repeated six times as per the design. The following quadratic polynomial equation depicts the statistical relationship between the dependent variable Phytase activity (Y) and the selected independent variables:

where Y is the predicted response (Phytase activity U/L); β

0 is the model intercept; Xi and Xj are the independent variables, βi is linear coefficients; βij is the cross-product coefficients; βii is the quadratic coefficients. For optimizing and determining interaction coefficients across many parameters the analysis of contour and surface plots achieved was utilized Rstudio.

2.10. Characterization of Crude Phytase

Thermostability of the enzyme was evaluated by treating the crude enzyme at 20oC, 30oC, 40oC, 50oC, 60oC,70oC, 80oC, and 90oC in a water bath for 1 hour. After heat treatment, the enzyme assay is done at standard assay conditions. A control is set which is not subject to any heat treatment. To investigate the optimum temperature for the enzyme, the enzyme assay is done at varying assay temperatures which are 25oC, 30oC, 37oC, 41oC, 50oC, 56oC, 65oC, and 70oC. Other conditions were as per the standard assay conditions. To determine the optimum pH for phytase activity enzyme assay is done in various pH buffer (3,4,5,6,7, and 8). All the standard protocol for phytase assay was followed except the use of specific buffers for different pH and individual standard curves were used for the buffers. The effect of metal ions on the enzyme’s catalytic behavior was studied by pre-incubating phytase enzyme at room temperature in a specified ion (5mM final concentration) containing buffer solution The metals ions were Ca2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Mn2+, Fe3+, and EDTA. After 1 hour of incubation, substrate (0.2% Na-phytate) was added and the relative activity of the enzyme was measured under standard assay conditions (untreated enzyme was taken as control).

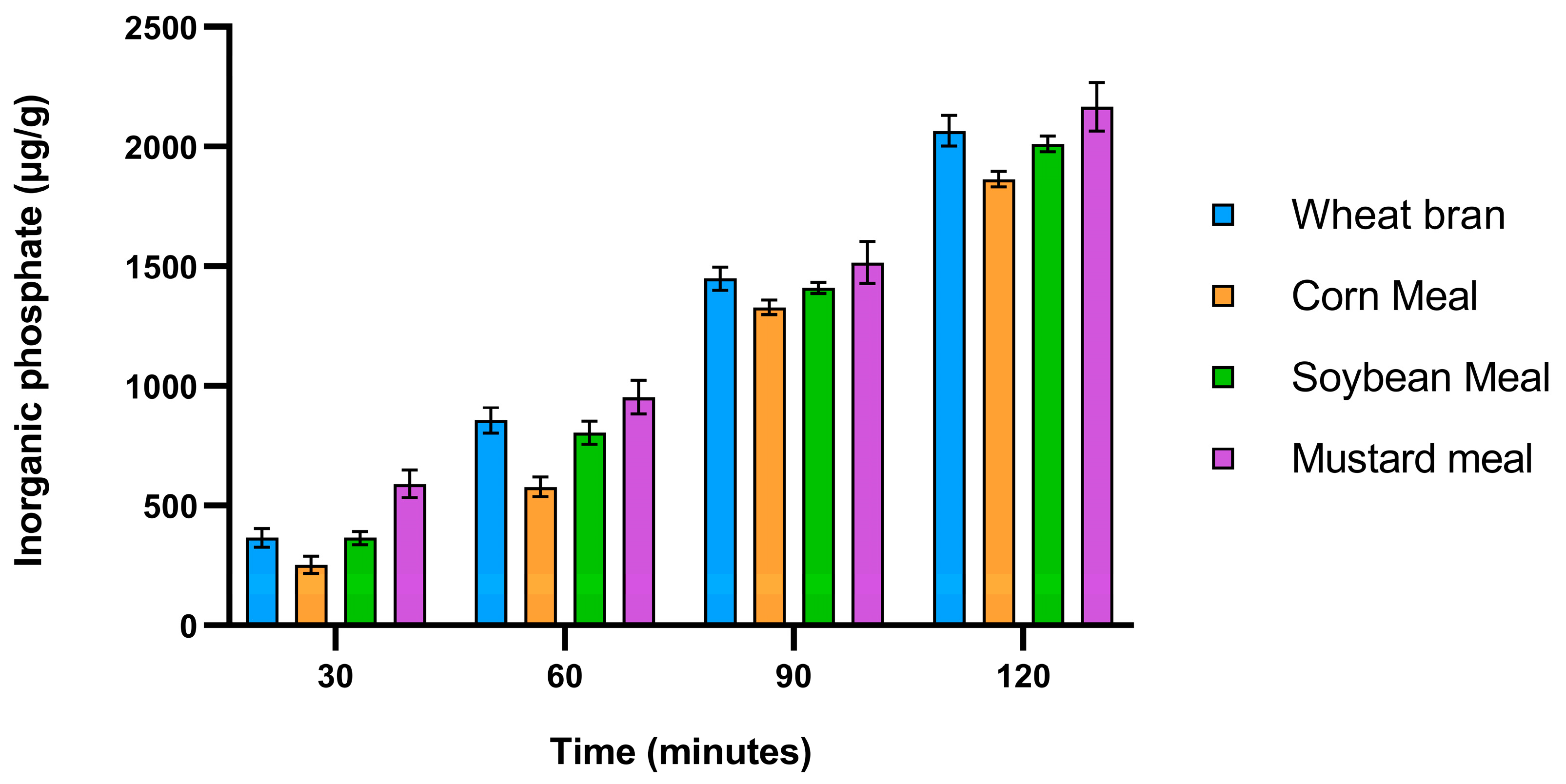

2.11. In-Vitro Dephytinization

A modified method from Suresh S and Radha K[

23] was adapted to test the applicability of the crude enzyme in dephytinization. 1g of wheat bran or mustard meal was placed into 18 mL of 0.1M pH 5 acetate buffer in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask. 2 mL of crude phytase was added and incubated at 120 rpm and 37

oC. After incubation for 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes, the suspension was centrifuged at 10000g for 10 min and the amount of inorganic phosphorus was detected by the method described previously.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analyses, experiment designs, and data visualization Minitab 21.4.2, Graphpad prism 9 and Rstudio 4.1 were used. Statistical significance among means was assumed at 5% significance level

4. Discussion

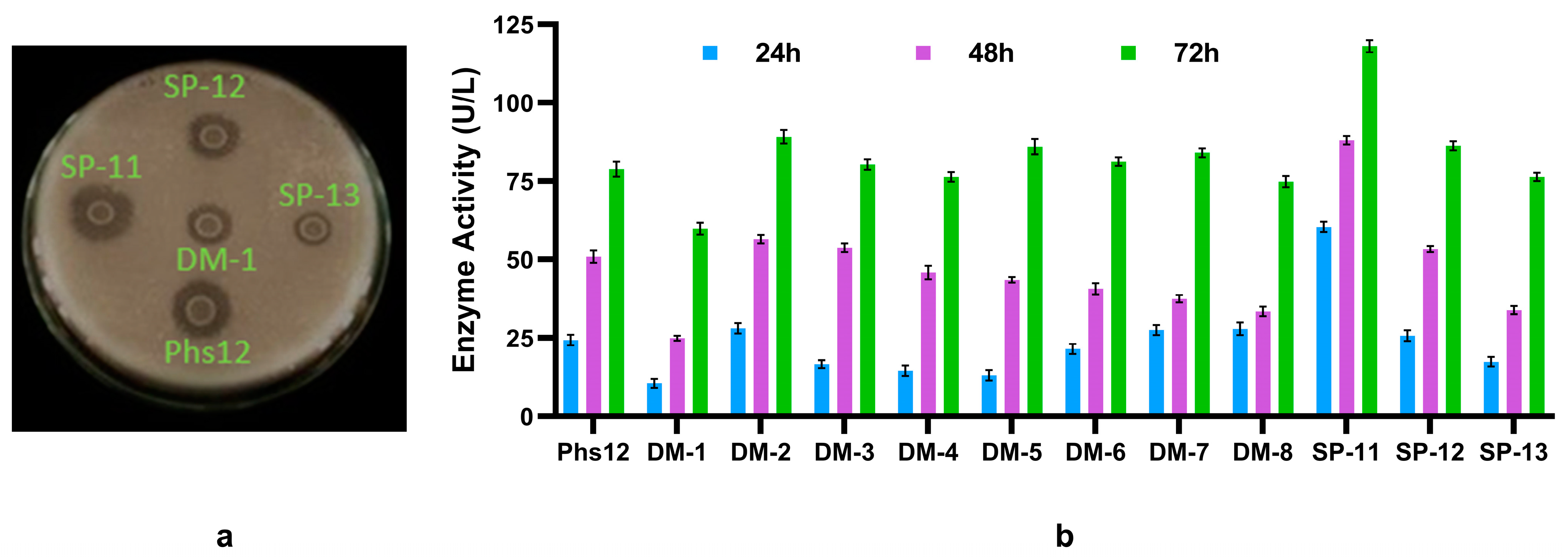

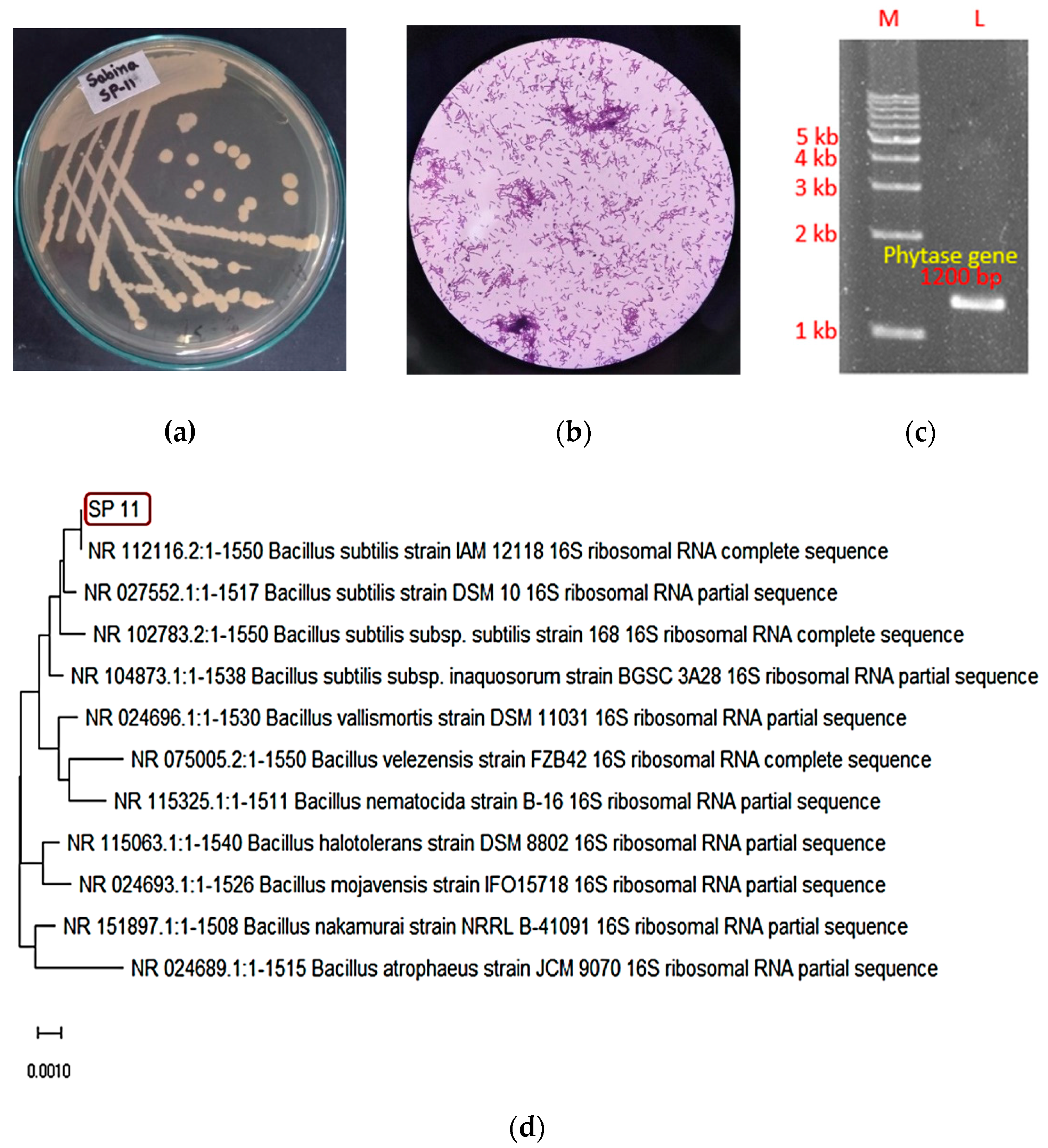

The goal of this study was to isolate a thermostable phytase-producing bacteria from broiler farms and optimize media composition using agro-industrial by-products to maximize phytase production. Twelve Isolates were selected based on the zone ratio in the PSM plate ranging from 1.3 to 2.3. A quantitative screening with the phytase production medium and the earlier zone ratio helped conclude that the SP11 strain is the best phytase producer among these isolated strains. Bacterial identification with microscopic, biochemical, and 16s rDNA characterization revealed that the species is

Bacillus subtilis and the presence of the phytase gene was confirmed by PCR amplification. Mussa et al. screened for phytase-producing bacteria from and around poultry farms but found no

Bacillus species as a notable producer[

24].

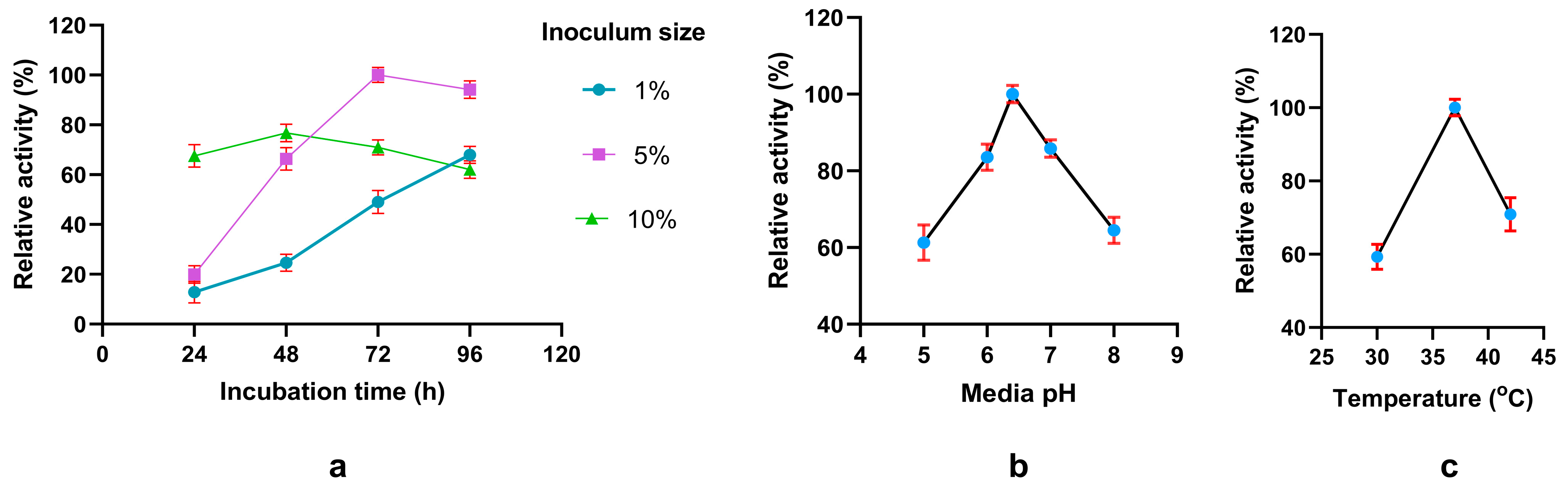

To optimize the fermentation protocol including both conditions and media composition, we initially analyzed by changing single fermentation condition per experiment, followed by statistical optimization using Plackett-Burman design (PBD) to identify significant media components and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to determine the optimum amount. Single factor analysis revealed that phytase production maximally occurs at pH 6.4 and 37

oC for 72 hours of fermentation, conditions that were applied later in the experiments. A similar case is seen for another

Bacillus species[

25] but the optimum temperature (30

oC) and incubation time (48h) differed for

B. subtilis US417[

16] As

B. subtilis is a mesophilic bacterium, it is not unusual for the ideal temperature to be 37

oC.

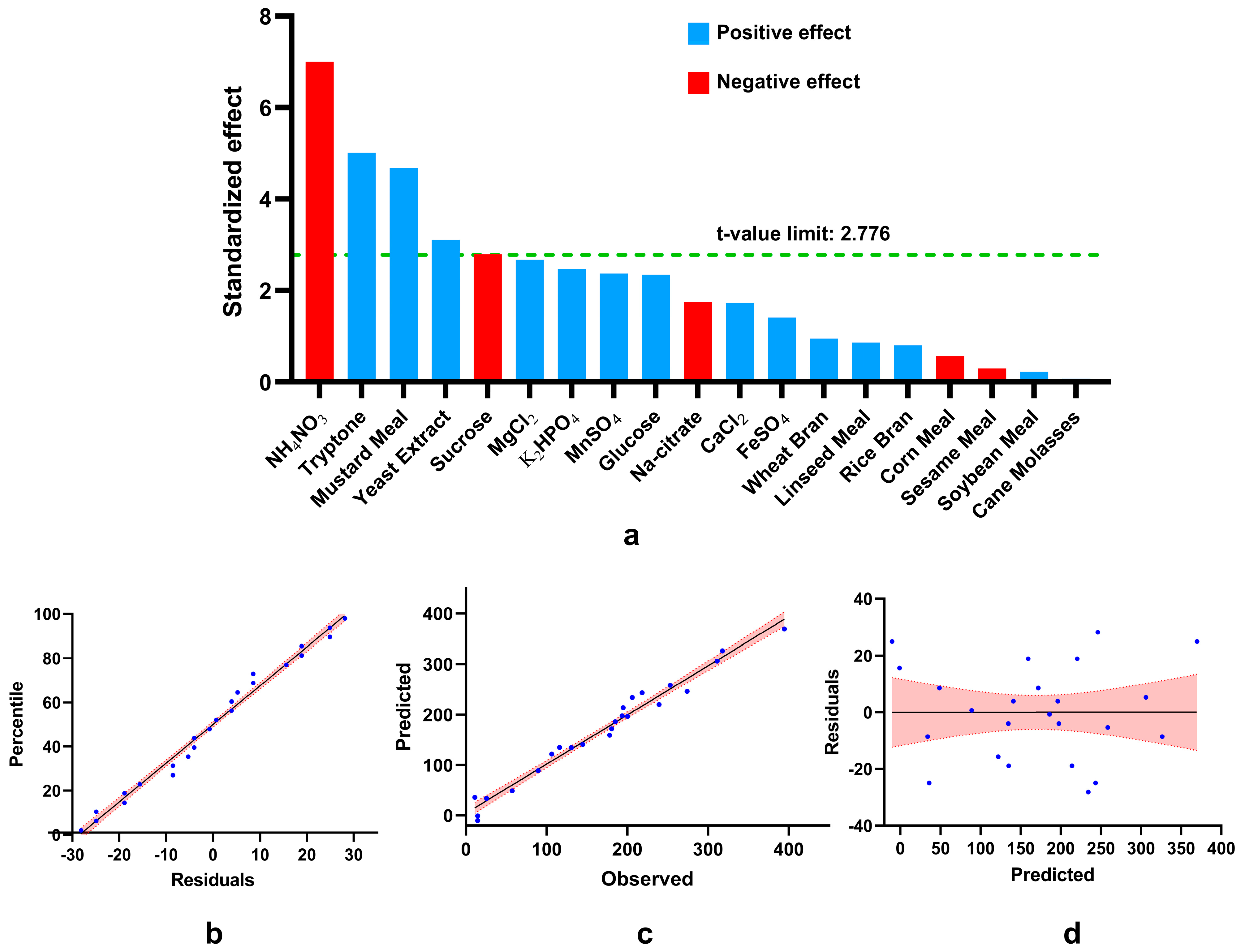

Plackett-Burman design (PBD) showed that mustard meal, tryptone, and yeast extract enhance but ammonium nitrate and sucrose inhibit phytase production significantly. The substantial positive effect of yeast extract[

16] and tryptone[

26] and the negative effect of ammonium nitrate[

27] on

Bacillus spp. have been previously reported which agrees with our findings. This indicates the critical role of nitrogen sources in phytase production. Mustard meal might have a multifunctional role here, serving as the main source of carbon (crude fiber:12-13%) and phytate (2-3%) and also providing nitrogen (crude protein: 30-32%) and required minerals[

29,

30]. Our study finds mustard meal as a fermentation media component for the first time as no previous report could be retrieved. However, our findings with sucrose as a significant inhibitor of phytase synthesis contradict previous report of

B. subtilis MJA where sucrose was the best carbon source for phytase production[

31].

Three positive factors from PBD were used in response surface methodology (RSM) to find the ideal amount. Central composite design (CCD) analysis suggested the optimum amount to be 2.21% mustard meal, 1.95% tryptone, and 1.8% yeast extract for a maximum phytase activity of 436 U/L with a 92% accuracy. Kammoun R. et al.[

16] used 5% w/v wheat bran for

B. subtilis US417 and found 0.75g yeast extract per gram of wheat bran to be the optimum amount. Our study found a similar ratio (0.81g yeast extract per gram of mustard meal), but the amount is half. However, 0.5% w/v tryptone was optimum for

Bacillus sp. HCYL03[

26] which is almost one-fourth of our finding with tryptone. This creates a significant limitation of the study as it will increase the cost of production. CCD obtained a 3.7 fold increase in the phytase production compared to initial unoptimized media. The high amount of required tryptone, yeast extract, and mustard meal along with the inhibition by ammonium nitrate and no dependence on simple carbon sources like cane molasses, glucose, or sucrose suggests that this strain’s phytase production is highly associated with utilization of polysaccharides as well as protein and peptide.

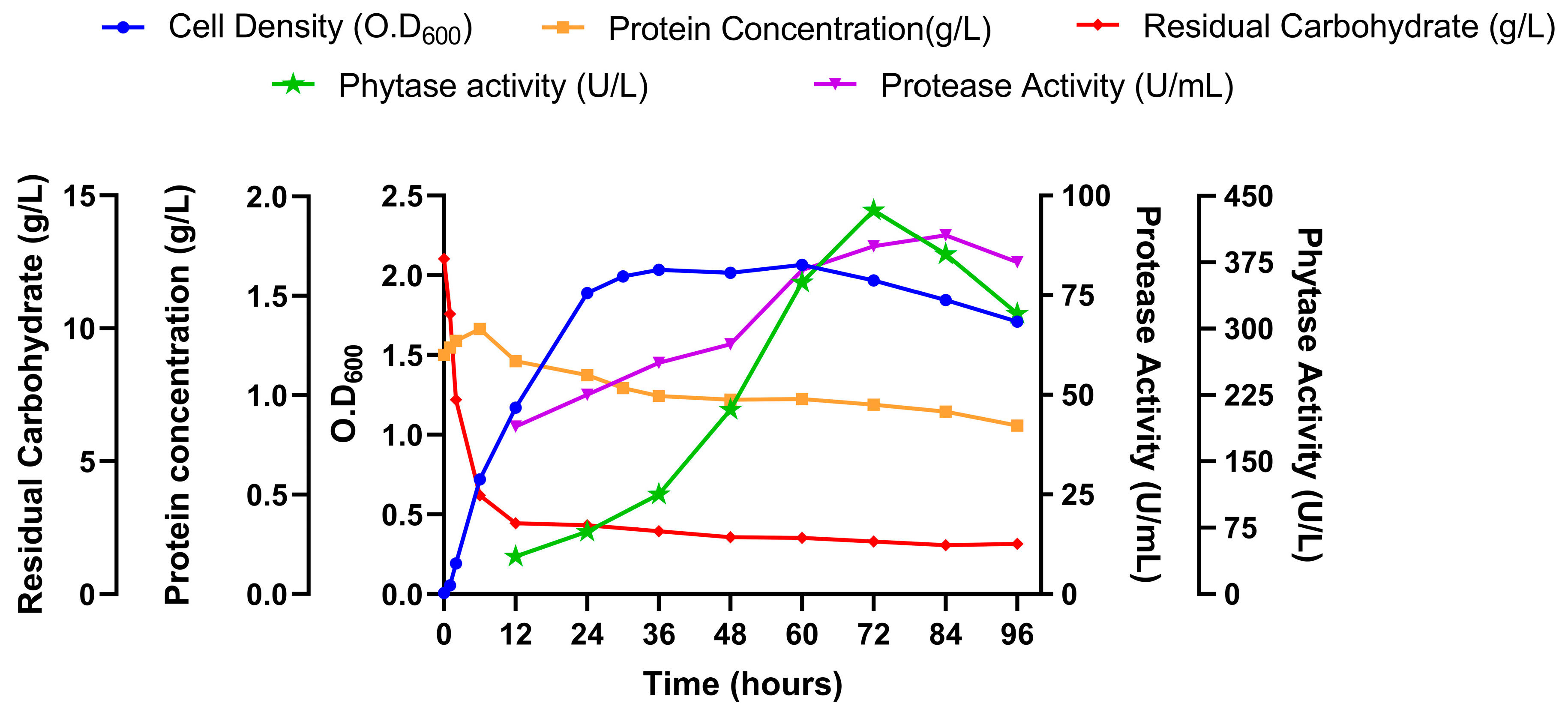

Monitoring the cell growth, nutrient utilization, and enzyme production were done at various time points up to 96 hours. Choi et al. reported that phytase production in

Bacillus spp. is increased in the stationary phase[

28]. However,

Figure 7c shows that

B. subtilis SP11 has the highest phytase activity at the death phase. Their study also suggested that phytase production may be related to nutrient limitation, which gives an idea about the inhibition of ammonium nitrate and sucrose on the phytase production by

B. subtilis SP11 while yeast extract, tryptone, and complex substrates like mustard meal enhance it. The initial increase of protein concentration may be due to the release of protein from mustard meal and then with the rise of protease activity it started getting utilized.

McCapes et al. suggested a combination of 85.7

oC conditioning temperature and 4.1 min heating time for effective feed pelleting processes[

32] due to which the feed enzymes need to be thermostable. Our crude phytase being thermostable, as shown in

Figure 7a, is thus compatible with the industrial feed pelleting process. The optimum temperature for the crude phytase of this strain is 50oC which is close to various previous reports stating 45oC[

24] to 55oC[

33]. It retains more than 95% of its activity at the body temperature of a chicken, which is near 41oC, thus ideal for poultry application[

34]. Crude phytase from

B. subtilis SP11 shows optimum pH of 6 which agrees with the study with

B. subtilis B.S.46[

35]. Nonetheless, their study showed high phytase activity even at pH 10 and no activity below pH 5 whereas our crude phytase is active in pH range 3-8. The pH of the crop and duodenum of different poultry birds is near 6[

36,

37], making this enzyme suitable for poultry.

Figure 7c suggests that the enzyme requires metal ions as cofactors because EDTA, which chelates metal ions, causes a massive decrease in phytase activity. This supports the mechanism of action of beta-propeller phytase, found in

B. subtilis, requiring calcium ions for its action[

38] . However, Mg

2+, Zn

2+and Mn

2+ do not affect phytase activity significantly which opposed the result shown by Rocky-Salimi et al. where metal ions inhibited phytase[

34]. Fe

2+ and Cu

2+ inhibiting crude phytase may be due to the complex formation of phytate with these ions that leads to insufficient binding to the active site and poor substrate availability[

39].

Although, the final optimized production was still lower than many of the reports of other bacteria and fungi, Bangladesh however, like many other countries, does not locally produce phytase and relies on imports from other countries[

18] which is why this holds an opportunity for the local poultry application and food security. To test the applicability of crude crude phtase, In vitro dephytinization of different raw materials such as corn meal, soybean meal, wheat bran and mustard meal were conducted. It shows that the crude phytase released higher phytate phosphates per gram of substrate per hour (896 to 1057 μg) than some of the previous reports from

Bacillus subtilis (759 μg), indicating its applicability in poultry feed dephytinization[

40]. The highest release seen in mustard meal may explain why it was the best substrate for phytase production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.K, M.M. and M.A.M.K., ; methodology, S., M.M.M., M.A.M.K and T.A.; software, M.A.M.K, M.M; validation, S.N.K., M.A.M.K.; formal analysis, M.M.K; investigation, S.N.K., M.M.K., M.A.A.M. ; resources, S.N.K., M.M.K., M.A.A.M. ; data curation, M.A.M.K. ; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.M.K.; writing—review and editing, S.N.K., M.M.K., and M.A.A.M., ; visualization, M.A.M.K; supervision, S.N.K; project administration, S.N.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Figure 1.

Isolation and screening of phytase-producing bacteria. (a) Isolation of phytase producing bacteria in phytate specific medium (PSM) plate. The halo zones indicate zone of phytate degradation. (b) Phytase production by the bacteria in the phytase production medium (broth) was measured at 24-hour intervals for 3 days

Figure 1.

Isolation and screening of phytase-producing bacteria. (a) Isolation of phytase producing bacteria in phytate specific medium (PSM) plate. The halo zones indicate zone of phytate degradation. (b) Phytase production by the bacteria in the phytase production medium (broth) was measured at 24-hour intervals for 3 days

Figure 2.

Identification of the phytase-producing SP11 isolate. (a) Colony morphology of SP11 isolate (b) 100x microscopic observation of SP11 (c) PCR confirmation of phytase gene (d) 16s rDNA-based phylogenetic tree showing SP11 as a Bacillus subtilis species

Figure 2.

Identification of the phytase-producing SP11 isolate. (a) Colony morphology of SP11 isolate (b) 100x microscopic observation of SP11 (c) PCR confirmation of phytase gene (d) 16s rDNA-based phylogenetic tree showing SP11 as a Bacillus subtilis species

Figure 3.

Factors influencing the production of phytase. Effect of (a) incubation time and inoculum size (b) various media pH and (c) different temperatures. Relative activity has been measured compared to the highest observed value for a particular experiment.

Figure 3.

Factors influencing the production of phytase. Effect of (a) incubation time and inoculum size (b) various media pH and (c) different temperatures. Relative activity has been measured compared to the highest observed value for a particular experiment.

Figure 4.

Analysis of results obtained by placket-burman design. (a) Pareto chart of standardized effect (absolute values of t-statistics) draws a reference line (α) on the chart. Any effect greater than α is statistically significant). Evaluation of the model’s fitness (b, c, and d) where the red region indicates 95% confidence bands. (b) Normal probability plot of residuals for phytase production. (c) Correlation between observed value and predicted values, (d) Residual versus predicted values show the equal distribution of residuals along both sides of the y-axis with no recognizable pattern.

Figure 4.

Analysis of results obtained by placket-burman design. (a) Pareto chart of standardized effect (absolute values of t-statistics) draws a reference line (α) on the chart. Any effect greater than α is statistically significant). Evaluation of the model’s fitness (b, c, and d) where the red region indicates 95% confidence bands. (b) Normal probability plot of residuals for phytase production. (c) Correlation between observed value and predicted values, (d) Residual versus predicted values show the equal distribution of residuals along both sides of the y-axis with no recognizable pattern.

Figure 5.

Response surface plots and contour plots showing how the tryptone, mustard meal, and yeast extract composition affect the production of phytase. (a) Surface plot and (b) contour plot of mustard meal vs tryptone (yeast extract held at 1.1 %), (c) Surface plot and (d) contour plot of mustard meal vs yeast extract (tryptone held at 1.4 %), (e) Surface plot and (f) contour plot of tryptone vs yeast extract (mustard meal held at 1.6%).

Figure 5.

Response surface plots and contour plots showing how the tryptone, mustard meal, and yeast extract composition affect the production of phytase. (a) Surface plot and (b) contour plot of mustard meal vs tryptone (yeast extract held at 1.1 %), (c) Surface plot and (d) contour plot of mustard meal vs yeast extract (tryptone held at 1.4 %), (e) Surface plot and (f) contour plot of tryptone vs yeast extract (mustard meal held at 1.6%).

Figure 6.

Time course profile of Cell growth and enzyme production by B. subtilis SP11.

Figure 6.

Time course profile of Cell growth and enzyme production by B. subtilis SP11.

Figure 7.

Characterization of the crude phytase. (a) Thermal stability (activity relative to untreated control) and temperature optima. (b) pH optima and (c) Effect of metal ions and EDTA (activity relative to untreated control). Different letters differ at 5% significance level at turkey’s test

Figure 7.

Characterization of the crude phytase. (a) Thermal stability (activity relative to untreated control) and temperature optima. (b) pH optima and (c) Effect of metal ions and EDTA (activity relative to untreated control). Different letters differ at 5% significance level at turkey’s test

Figure 8.

In vitro dephytinization of wheat bran, corn meal, soybean meal and mustard meal using crude phytase.

Figure 8.

In vitro dephytinization of wheat bran, corn meal, soybean meal and mustard meal using crude phytase.

Table 1.

Nineteen Independent variables used for Plackett-Burman Design for the optimization of phytase production by Bacillus subtilis SP11 having two levels: High (+1) and Low (-1).

Table 1.

Nineteen Independent variables used for Plackett-Burman Design for the optimization of phytase production by Bacillus subtilis SP11 having two levels: High (+1) and Low (-1).

| Code |

Variable |

Low Value (-1) (%w/v) |

High Value (+1) (% w/v) |

| X1

|

Rice Bran |

0 |

1 |

| X2

|

Wheat Bran |

0 |

1 |

| X3

|

Corn Meal |

0 |

1 |

| X4

|

Soybean Meal |

0 |

1 |

| X5

|

Sesame Meal |

0 |

1 |

| X6

|

Mustard Meal |

0 |

1 |

| X7

|

Linseed Meal |

0 |

1 |

| X8

|

Cane Molasses |

0 |

2 |

| X9

|

Glucose |

0.4% |

1 |

| X10

|

NH4NO3

|

0.2% |

0.5 |

| X11

|

Tryptone |

0 |

1 |

| X12

|

Yeast Extract |

0 |

0.5 |

| X13

|

K2HPO4

|

0.02% |

0.1 |

| X14

|

Sucrose |

0 |

1 |

| X15

|

CaCl2

|

0.002% |

0.02 |

| X16

|

MgCl2

|

0.002% |

0.02 |

| X17

|

FeSO4

|

0.002% |

0.02 |

| X18

|

MnSO4

|

0.002% |

0.02 |

| X19

|

Sodium Citrate |

0 |

1 |

Table 2.

Twenty-four experimental runs for Plackett-Burman Design with nineteen different variables with Low and High Values and their phytase activity. Red and green colored boxes indicate low value (-1) and high value (+1) respectively

Table 2.

Twenty-four experimental runs for Plackett-Burman Design with nineteen different variables with Low and High Values and their phytase activity. Red and green colored boxes indicate low value (-1) and high value (+1) respectively

| Run |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

J |

K |

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

Q |

R |

S |

T |

Phytase activity (U/L) |

| Observed |

Predicted |

Residuals |

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

89.59 |

88.868 |

0.7225 |

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

194.99 |

213.874 |

-18.8842 |

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

180.54 |

171.998 |

8.5425 |

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

394.57 |

369.679 |

24.8908 |

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

185.13 |

185.852 |

-0.7225 |

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

57.29 |

48.748 |

8.5425 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

253.13 |

258.414 |

-5.2842 |

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

317.90 |

326.443 |

-8.5425 |

| 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

193.63 |

197.611 |

-3.9808 |

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11.05 |

35.941 |

-24.8908 |

| 11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

218.45 |

243.341 |

-24.8908 |

| 12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

144.84 |

140.859 |

3.9808 |

| 13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14.62 |

-1.006 |

15.6258 |

| 14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

130.56 |

134.541 |

-3.9808 |

| 15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

106.25 |

121.876 |

-15.6258 |

| 16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

178.16 |

159.276 |

18.8842 |

| 17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25.50 |

34.043 |

-8.5425 |

| 18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

116.11 |

134.994 |

-18.8842 |

| 19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

239.36 |

220.476 |

18.8842 |

| 20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

206.04 |

234.189 |

-28.1492 |

| 21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

274.21 |

246.061 |

28.1492 |

| 22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

311.44 |

306.156 |

5.2842 |

| 23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14.62 |

-10.271 |

24.8908 |

| 24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

200.26 |

196.279 |

3.9808 |

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of Plackett–Burman design experimental results

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of Plackett–Burman design experimental results

| Term |

Coefficients |

t-statistics |

F-value |

p-value |

Contribution |

| Constant |

169.09 |

20.73 |

|

0.000 |

|

| Rice Bran |

6.56 |

0.8 |

0.65 |

0.466 |

0.42% |

| Wheat Bran |

7.73 |

0.95 |

0.9 |

0.397 |

0.59% |

| Corn Meal |

-4.55 |

-0.56 |

0.31 |

0.607 |

0.20% |

| Soybean Meal |

1.83 |

0.22 |

0.05 |

0.834 |

0.03% |

| Sesame Meal |

-2.45 |

-0.3 |

0.09 |

0.779 |

0.06% |

| Mustard Meal |

38.22 |

4.68 |

21.95 |

0.009 |

14.38% |

| Linseed Meal |

7.01 |

0.86 |

0.74 |

0.439 |

0.48% |

| Cane Molasses |

0.57 |

0.07 |

0 |

0.948 |

0.00% |

| Glucose |

19.14 |

2.35 |

5.5 |

0.079 |

3.61% |

| NH4NO3

|

-57.08 |

-7 |

48.94 |

0.002 |

32.07% |

| Tryptone |

40.87 |

5.01 |

25.1 |

0.007 |

16.45% |

| Yeast Extract |

25.4 |

3.11 |

9.69 |

0.036 |

6.35% |

| K2HPO4

|

20.15 |

2.47 |

6.1 |

0.069 |

4.00% |

| Sucrose |

-22.77 |

-2.79 |

7.79 |

0.049 |

5.10% |

| CaCl2

|

14.04 |

1.72 |

2.96 |

0.16 |

1.94% |

| MgCl2

|

21.8 |

2.67 |

7.14 |

0.056 |

4.68% |

| FeSO4

|

11.5 |

1.41 |

1.99 |

0.231 |

1.30% |

| MnSO4

|

19.41 |

2.38 |

5.66 |

0.076 |

3.71% |

| Na-citrate |

-14.24 |

-1.75 |

3.05 |

0.156 |

2.00% |

| Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) |

| Source |

DF |

Adj SS |

Adj MS |

F-Value |

P-Value |

| Model |

19 |

237392 |

12494 |

7.82 |

0.030 |

| Residuals |

4 |

8840 |

2210 |

|

|

| R2 = 97.38% |

Table 4.

Central Composite Design for phytase production by Bacillus subtilis SP11 along with results and residuals. For axial points α =1.68, Low value=-1, Medium=0 and High value=+1

Table 4.

Central Composite Design for phytase production by Bacillus subtilis SP11 along with results and residuals. For axial points α =1.68, Low value=-1, Medium=0 and High value=+1

| Run |

Mustard Meal (X6) |

Tryptone (X11) |

Yeast Extract (X12) |

Phytase Activity (U/L) |

|

| Observed |

Predicted |

Residual |

|

| 1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

388.8 |

361.9 |

26.8 |

|

| 2 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

257.2 |

244.1 |

13.1 |

|

| 3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

427.0 |

386.5 |

40.5 |

|

| 4 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

219.2 |

236.4 |

-17.2 |

|

| 5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

374.7 |

361.9 |

12.8 |

|

| 6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

378.7 |

361.9 |

16.8 |

|

| 7 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

323.6 |

313.4 |

10.2 |

|

| 8 |

0 |

0 |

-1.68 |

199.4 |

189.3 |

10.1 |

|

| 9 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

231.8 |

246.4 |

-14.6 |

|

| 10 |

0 |

0 |

1.68 |

274.6 |

317.7 |

-43.1 |

|

| 11 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

353.8 |

361.9 |

-8.2 |

|

| 12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

349.7 |

361.9 |

-12.3 |

|

| 13 |

1.68 |

0 |

0 |

232.0 |

287.4 |

-55.4 |

|

| 14 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

153.9 |

151.2 |

2.7 |

|

| 15 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

367.7 |

329.8 |

37.9 |

|

| 16 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

169.2 |

148.6 |

20.6 |

|

| 17 |

0 |

1.68 |

0 |

287.7 |

310.2 |

-22.5 |

|

| 18 |

-1.68 |

0 |

0 |

242.0 |

219.5 |

22.5 |

|

| 19 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

331.6 |

361.9 |

-30.3 |

|

| 20 |

0 |

-1.68 |

0 |

243.7 |

254.1 |

-10.5 |

|

| Level |

Mustard meal

(% w/v) |

Tryptone

(% w/v) |

Yeast extract

(% w/v) |

|

|

|

|

| - α |

0.3 |

0.25 |

0.2 |

|

|

|

|

| -1 |

0.85 |

0.71 |

0.57 |

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

1.65 |

1.38 |

1.1 |

|

|

|

|

| +1 |

2.45 |

2.04 |

1.64 |

|

|

|

|

| + α |

3 |

2.5 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

Multiple regression analysis and ANOVA of the central composite design.

Table 5.

Multiple regression analysis and ANOVA of the central composite design.

| Term |

Coefficient |

t-statistics |

p-value |

| Constant |

361.9 |

24.86 |

0.000 |

| Mustard Meal |

20.19 |

2.09 |

0.063 |

| Tryptone |

16.66 |

1.72 |

0.115 |

| Yeast Extract |

38.16 |

3.95 |

0.003 |

| Mustard Meal*Mustard Meal |

-38.35 |

-4.08 |

0.002 |

| Tryptone*Tryptone |

-28.2 |

-3 |

0.013 |

| Yeast Extract*Yeast Extract |

-38.33 |

-4.08 |

0.002 |

| Mustard Meal*Tryptone |

-26.4 |

-2.09 |

0.063 |

| Mustard Meal*Yeast Extract |

42.7 |

3.38 |

0.007 |

| Tryptone*Yeast Extract |

38.1 |

3.02 |

0.013 |

| Source |

DF |

F-value |

p-value |

| Model |

9 |

9.26 |

0.001 |

| Linear |

3 |

7.65 |

0.006 |

| Square |

3 |

11.82 |

0.001 |

| 2-Way Interaction |

3 |

8.3 |

0.005 |

| Lack-of-Fit |

5 |

4.55 |

0.061 |

| R2 = 89.28% |