Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

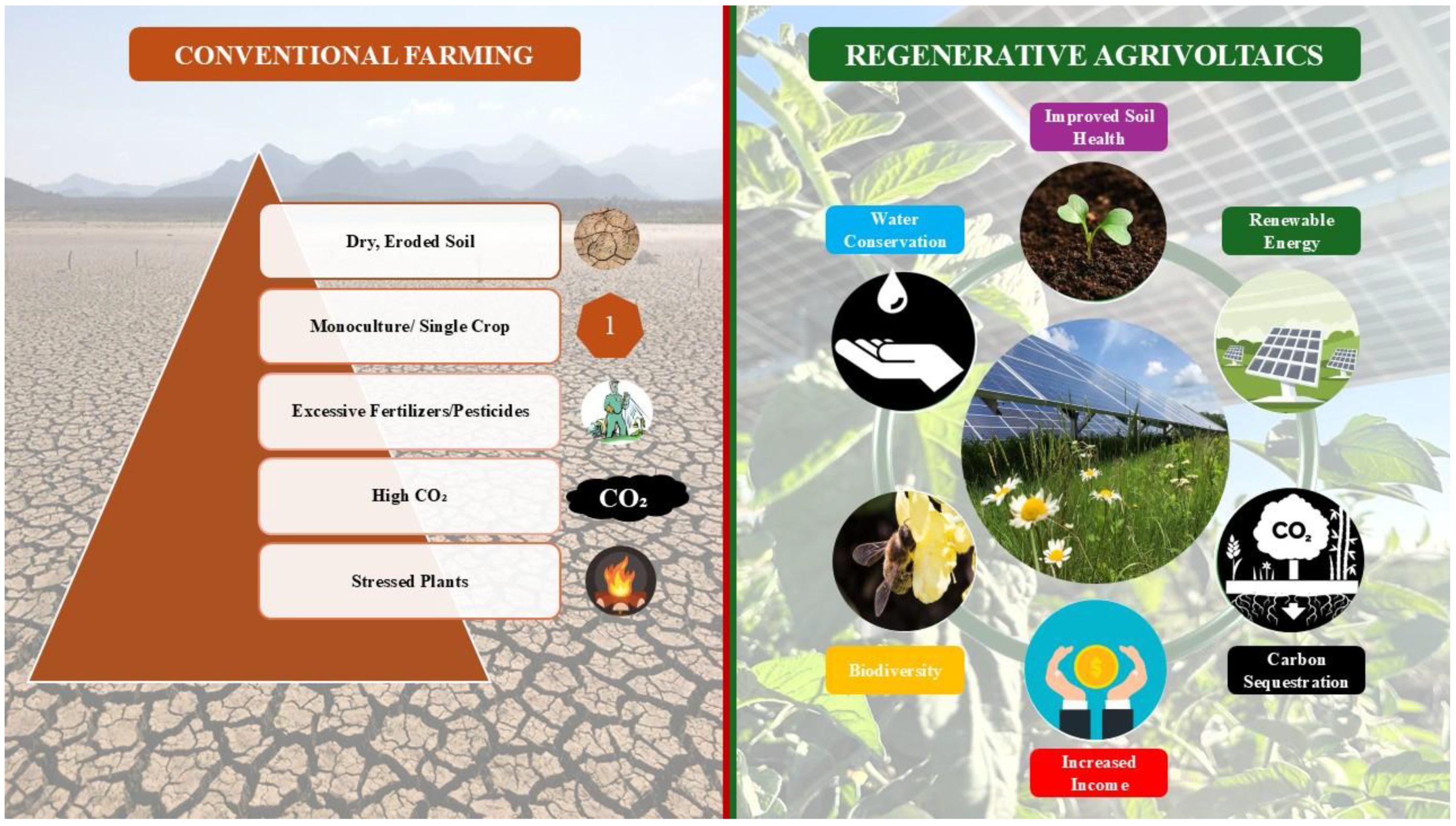

1.1. Regenerative Agriculture: A Sustainable Approach to Food Production

1.2. Agrivoltaics: Integrating Energy and Agriculture

1.3. Economics and Market Growth of Agrivoltaics

1.4. Combining Regenerative Farming and Agrivoltaics

2. Fostering Resilience: Agrivoltaics Meets Regenerative Agriculture – Regenerative Agrivoltaic

3. Innovative Agrivoltaic Strategies for Regenerative Agriculture

3.1. Cover Cropping

3.2. Increasing Crop Diversity

3.3. Organic Annual Cropping

3.4. Composting

3.5. Animal Integration

3.6. Managed Grazing

3.7. Reduced/No-Till Farming Practices

3.8. Silvopasture/Agroforestry

4. Unlocking the Potential of Regenerative Agrivoltaics: Synergies, Challenges, and Theoretical Contributions

4.1. Synergies and Opportunities

4.2. Challenges and Barriers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fróna, D.; Szenderák, J.; Harangi-Rákos, M. The Challenge of Feeding the World. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstra, N.; Vermeulen, L.C. Impacts of Population Growth, Urbanisation and Sanitation Changes on Global Human Cryptosporidium Emissions to Surface Water. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2016, 219, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamuda, H.E.A.F.B.; Patko, I. Relationship between Environmental Impacts and Modern Agriculture 2010.

- Padhiary, M.; Kumar, R. Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Agriculture, Industrial Operations, and Mining on Agro-Ecosystems. In Smart Internet of Things for Environment and Healthcare; Azrour, M., Mabrouki, J., Alabdulatif, A., Guezzaz, A., Amounas, F., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-70102-3. [Google Scholar]

- Maraseni, T.N.; Qu, J. An International Comparison of Agricultural Nitrous Oxide Emissions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 135, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture Production and Its Sustainable Solutions. Environmental Sustainability 2019, 2, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. The Imperative for Regenerative Agriculture. Science Progress 2017, 100, 80–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreefel, L.; Schulte, R.P.O.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Schrijver, A.P.; van Zanten, H.H.E. Regenerative Agriculture – the Soil Is the Base. Global Food Security 2020, 26, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Civita, N.; Frankel-Goldwater, L.; Bartel, K.; Johns, C. What Is Regenerative Agriculture? A Review of Scholar and Practitioner Definitions Based on Processes and Outcomes. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drawdown, P. About Project Drawdown | Project Drawdown. Available online: https://drawdown.org/about (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Eichler, S. ; Mamta Mehra; Eric Toensmeier; Chad Frischmann Regenerative Annual Cropping | Project Drawdown. Available online: https://drawdown.org/solutions/regenerative-annual-cropping (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Giller, K.E.; Hijbeek, R.; Andersson, J.A.; Sumberg, J. Regenerative Agriculture: An Agronomic Perspective. Outlook Agric 2021, 50, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. Why Regenerative Agriculture? The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 2020, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, P.A.; Duic, N.; Noorollahi, Y.; Kalogirou, S. Advances in Renewable Energy for Sustainable Development. Renewable Energy 2023, 219, 119377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Srivastava, R.K. Sustainability Perspectives- a Review for Solar Photovoltaic Trends and Growth Opportunities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 227, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory Documenting a Decade of Cost Declines for PV Systems. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/news/program/2021/documenting-a-decade-of-cost-declines-for-pv-systems.html (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Späth, L. Large-Scale Photovoltaics? Yes Please, but Not like This! Insights on Different Perspectives Underlying the Trade-off between Land Use and Renewable Electricity Development. Energy Policy 2018, 122, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Marklein, A.; Toth, M.A.; Karpoff, M.; Paul, G.S.; McCormack, R.; Kyriazis, J.; Krueger, T. Biofuel Impacts on World Food Supply: Use of Fossil Fuel, Land and Water Resources. Energies 2008, 1, 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Bonnington, A.; Pearce, J.M. The Agrivoltaic Potential of Canada. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fthenakis, V.M.; Kim, H.C.; Alsema, E. Emissions from Photovoltaic Life Cycles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 2168–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, K. The Impact of Climate Change on the Global Economy 2017.

- Elamri, Y.; Cheviron, B.; Lopez, J.-M.; Dejean, C.; Belaud, G. Water Budget and Crop Modelling for Agrivoltaic Systems: Application to Irrigated Lettuces. Agricultural Water Management 2018, 208, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, M.; Lahham, N. Solar Energy Farming as a Development Innovation for Vulnerable Water Basins. Development in Practice 2019, 29, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, B.D.; Stillinger, C.; Chapman, E.; Martin, M.; Riihimaki, B. Residential Agrivoltaics: Energy Efficiency and Water Conservation in the Urban Landscape. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Green Technologies Conference (GreenTech), April 2021; pp. 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, R.; Khanna, M. Harnessing Advances in Agricultural Technologies to Optimize Resource Utilization in the Food-Energy-Water Nexus. Annual Review of Resource Economics 2020, 12, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M.; Kang, J.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S.; Bopp, G.; Ehmann, A.; Weselek, A.; Högy, P.; Obergfell, T. Combining Food and Energy Production: Design of an Agrivoltaic System Applied in Arable and Vegetable Farming in Germany. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 140, 110694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.P.; Bombelli, E.L.; Shubham, S.; Watson, H.; Everard, A.; D’Ardes, V.; Schievano, A.; Bocchi, S.; Zand, N.; Howe, C.J.; et al. Tinted Semi-Transparent Solar Panels Allow Concurrent Production of Crops and Electricity on the Same Cropland. Advanced Energy Materials 2020, 10, 2001189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudelson, T.; Lieth, J.H. Crop Production in Partial Shade of Solar Photovoltaic Panels on Trackers. AIP Conference Proceedings 2021, 2361, 080001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Högy, P. Effects on Crop Development, Yields and Chemical Composition of Celeriac (Apium Graveolens L. Var. Rapaceum) Cultivated Underneath an Agrivoltaic System. Agronomy 2021, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Rahman, M.; Pearce, J.M. Complexities in Agrivoltaic Policy Mandates Illustrated with Semitransparent Photovoltaic Yields 2024.

- Jamil, U.; Rahman, M.M.; Hayibo, K.S.; Alrayes, L.; Fordjour, E.; Thomas, R.; Pearce, J.M. Impacts of Transparency in Agrivoltaics Lettuce Cultivation Using Uniform or Non-Uniform Semitransparent Solar Photovoltaic Modules 2024.

- Sekiyama, T.; Nagashima, A. Solar Sharing for Both Food and Clean Energy Production: Performance of Agrivoltaic Systems for Corn, A Typical Shade-Intolerant Crop. Environments 2019, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Pearce, J.M. Impacts of Type of Partial Transparency on Strawberry Agrivoltaics Uniform Illumination Thin Film Cadmium-Telluride and Non-Uniform Crystalline Silicon Solar Photovoltaic Modules 2024.

- Jamil, U.; Pearce, J.M. Experimental Impacts of Transparency on Strawberry Agrivoltaics Using Thin Film Photovoltaic Modules Under Low Light Conditions 2024.

- Adeh, E.H.; Selker, J.S.; Higgins, C.W. Remarkable Agrivoltaic Influence on Soil Moisture, Micrometeorology and Water-Use Efficiency. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0203256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Pearce, J.M. Maximizing Biomass with Agrivoltaics: Potential and Policy in Saskatchewan Canada. Biomass 2023, 188–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Ehmann, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Schindele, S.; Högy, P. Agrophotovoltaic Systems: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SJ Herbert Yield Comparisons UMass Farm NREL Co-Location Project 2016-17 2018.

- SJ Herbert; K Oleskewicz UMass Dual-Use Solar Agricultural Report and Final Report Summary 2019.

- Trommsdorff, M.; Dhal, I.S.; Özdemir, Ö.E.; Ketzer, D.; Weinberger, N.; Rösch, C. Chapter 5 - Agrivoltaics: Solar Power Generation and Food Production. In Solar Energy Advancements in Agriculture and Food Production Systems; Gorjian, S., Campana, P.E., Eds.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 159–210. ISBN 978-0-323-89866-9. [Google Scholar]

- B. Tiffon-Terrade Effect of Transient Shading on Phenology and Berry Growth in Grapevine 2020.

- Willockx, B.; Kladas, A.; Lavaert, C.; Uytterhaegen, B.; Cappelle, J. HOW AGRIVOLTAICS CAN BE USED AS A CROP PROTECTION SYSTEM. In Proceedings of the EUROSIS, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pan, S.; Wang, Q.; He, J.; Jia, X. An Agrivoltaic Park Enhancing Ecological, Economic and Social Benefits on Degraded Land in Jiangshan, China.; Freiburg, Germany, 2022; p. 020002.

- Williams, J. How China Uses Renewable Energy to Restore the Desert. The Earthbound Report 2022.

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P.; et al. Agrivoltaics Provide Mutual Benefits across the Food–Energy–Water Nexus in Drylands. Nat Sustain 2019, 2, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, C.; Marrou, H.; Talbot, G.; Dufour, L.; Nogier, A.; Ferard, Y. Combining Solar Photovoltaic Panels and Food Crops for Optimising Land Use: Towards New Agrivoltaic Schemes. Renewable Energy 2011, 36, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindele, S.; Trommsdorff, M.; Schlaak, A.; Obergfell, T.; Bopp, G.; Reise, C.; Braun, C.; Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Högy, P.; et al. Implementation of Agrophotovoltaics: Techno-Economic Analysis of the Price-Performance Ratio and Its Policy Implications. Applied Energy 2020, 265, 114737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavani, D.D.; Chauhan, P.M.; Joshi, V. Beauty of Agrivoltaic System Regarding Double Utilization of Same Piece of Land for Generation of Electricity & Food Production. IJSER 2019, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Mow, B. Solar Sheep and Voltaic Veggies: Uniting Solar Power and Agriculture. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/state-local-tribal/blog/posts/solar-sheep-and-voltaic-veggies-uniting-solar-power-and-agriculture.html (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Adeh, E.H.; Good, S.P.; Calaf, M.; Higgins, C.W. Solar PV Power Potential Is Greatest Over Croplands. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 11442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, R. The Local Food Movement: Definitions, Benefits, and Resources. USU Extension Publication 2012, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S.; Hand, M.; Pra, M.; Pollack, S.; Ralston, K.; Smith, T.; Vogel, S.; Clark, S.; Lohr, L.; Low, S.; et al. Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues. In Local Food Systems: Background and Issues; 2010; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra, G.W. Local Food Systems and Sustainable Communities. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 1997, 12, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prehoda, E.W.; Pearce, J.M. Potential Lives Saved by Replacing Coal with Solar Photovoltaic Electricity Production in the U.S. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 80, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeldt, N.; Pearce, J.M. Can Grid-Tied Solar Photovoltaics Lead to Residential Heating Electrification? A Techno-Economic Case Study in the Midwestern U.S. Applied Energy 2023, 336, 120838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.T.; Hayibo, K.S.; Hafting, F.; Pearce, J.M. Economics of Open-Source Solar Photovoltaic Powered Cryptocurrency Mining 2022.

- Tributsch, H. Photovoltaic Hydrogen Generation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 5911–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereidooni, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Kalantar, V.; Goudarzi, H. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Hydrogen Production from Photovoltaic Power Station. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Mukherjee, V. Off-Grid Solar Photovoltaic/Hydrogen Fuel Cell System for Renewable Energy Generation: An Investigation Based on Techno-Economic Feasibility Assessment for the Application of End-User Load Demand in North-East India. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 149, 111421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Weiss, R.; Savolainen, J.; Breyer, C. Global Potential of Green Ammonia Based on Hybrid PV-Wind Power Plants. Applied Energy 2021, 294, 116170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Denkenberger, D.; Pearce, J.M. Solar Photovoltaic Powered On-Site Ammonia Production for Nitrogen Fertilization. Solar Energy 2015, 122, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.K.; Pearce, J.M. How Easy Is It to Feed Everyone? Economic Alternatives to Eliminate Human Nutrition Deficits. Food ethics 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Pearce, J.M. Energy Policy for Agrivoltaics in Alberta Canada. Energies 2023, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.; Lara, R.; Pearce, J.M. Financial Analysis of Agrivoltaic Sheep: Breeding and Auction Lamb Business Models. Applied Energy 2025, 381, 125057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MarkNtel Advisors Agrivoltaics Market Share, Size, & Industry Growth Report 2030 | Latest. Available online: https://www.marknteladvisors.com/research-library/agrivoltaic-market.html (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Singh, S. Energy Crisis and Climate Change. In Energy; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2021; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-119-74150-3. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, E. The Coming Global Food Crisis. Cornhusker Economics 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Hartung, J.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Högy, P. Agrivoltaic System Impacts on Microclimate and Yield of Different Crops within an Organic Crop Rotation in a Temperate Climate. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khangura, R.; Ferris, D.; Wagg, C.; Bowyer, J. Regenerative Agriculture—A Literature Review on the Practices and Mechanisms Used to Improve Soil Health. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, L.A.; Dale, B.E.; Bozzetto, S.; Liebman, M.; Souza, G.M.; Haddad, N.; Richard, T.L.; Basso, B.; Brown, R.C.; Hilbert, J.A.; et al. Meeting Global Challenges with Regenerative Agriculture Producing Food and Energy. Nat Sustain 2022, 5, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. Carbon Sequestration in Agricultural Soils via Cultivation of Cover Crops – A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2015, 200, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C.; Bailey, B.A. Role of Cover Crops in Improving Soil and Row Crop Productivity. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2005, 36, 2733–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, W.W.; Blevins, R.L.; Smith, M.S.; Corak, S.J.; Varco, J.J. Role of Annual Legume Cover Crops in Efficient Use of Water and Nitrogen. In Cropping Strategies for Efficient Use of Water and Nitrogen; ASA Special Publications, 1988; Vol. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil Carbon Sequestration to Mitigate Climate Change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Solas, Á.; Fernández-Ocaña, A.M.; Almonacid, F.; Fernández, E.F. Potential of Agrivoltaics Systems into Olive Groves in the Mediterranean Region. Applied Energy 2023, 352, 121988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, A.; Colauzzi, M.; Amaducci, S. Innovative Agrivoltaic Systems to Produce Sustainable Energy: An Economic and Environmental Assessment. Applied Energy 2021, 281, 116102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jia, L.; Jia, T.; Hao, Z. An Carbon Neutrality Industrial Chain of “Desert-Photovoltaic Power Generation-Ecological Agriculture”: Practice from the Ulan Buh Desert, Dengkou, Inner Mongolia. zgdzyw 2022, 5, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fuentes, I.A.; Elamri, Y.; Cheviron, B.; Dejean, C.; Belaud, G.; Fumey, D. Effects of Shade and Deficit Irrigation on Maize Growth and Development in Fixed and Dynamic AgriVoltaic Systems. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 280, 108187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T.; Scarano, A.; Curci, L.M.; Leggieri, A.; Lenucci, M.; Basset, A.; Santino, A.; Piro, G.; De Caroli, M. Shading Effects in Agrivoltaic Systems Can Make the Difference in Boosting Food Security in Climate Change. Applied Energy 2024, 358, 122565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchanski, M.; Hickey, T.; Bousselot, J.; Barth, K.L. Characterization of Agrivoltaic Crop Environment Conditions Using Opaque and Thin-Film Semi-Transparent Modules. Energies 2023, 16, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Liu, W.; Ali Abaker Omer, A.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W. Spectral-Splitting Concentrator Agrivoltaics for Higher Hybrid Solar Energy Conversion Efficiency. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 276, 116567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, R.; Pearce, J.M. Greener Sheep: Life Cycle Analysis of Integrated Sheep Agrivoltaic Systems. Cleaner Energy Systems 2022, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, F.G.A.; Bastos, A.C. Discussion: Avoid Severe (Future) Soil Erosion from Agrivoltaics. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 873, 162249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T.; Pimentel, D.; Paoletti, M.G. Environmental Impact of Different Agricultural Management Practices: Conventional vs. Organic Agriculture. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2011, 30, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C. a.; Atkinson, D.; Gosling, P.; Jackson, L. r.; Rayns, F. w. Managing Soil Fertility in Organic Farming Systems. Soil Use and Management 2002, 18, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaoui, M.; Jemo, M.; Datla, R.; Bekkaoui, F. Heat and Drought Stresses in Crops and Approaches for Their Mitigation. Front. Chem. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasyl Cherlinka Heat Stress In Plants: Symptoms, Prevention, And Recovery. Available online: https://eos.com/blog/heat-stress-in-plants/ (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Lal, R. Challenges and Opportunities in Soil Organic Matter Research. European Journal of Soil Science 2009, 60, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corato, U. Agricultural Waste Recycling in Horticultural Intensive Farming Systems by On-Farm Composting and Compost-Based Tea Application Improves Soil Quality and Plant Health: A Review under the Perspective of a Circular Economy. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 738, 139840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti, R.; Pane, C.; Spaccini, R.; Palese, A.M.; Piccolo, A.; Celano, G.; Zaccardelli, M. On-Farm Compost: A Useful Tool to Improve Soil Quality under Intensive Farming Systems. Applied Soil Ecology 2016, 107, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, K.T.; Heins, B.J.; Buchanan, E.S.; Reese, M.H. Evaluation of Solar Photovoltaic Systems to Shade Cows in a Pasture-Based Dairy Herd. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 2794–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M.; Montemurro, F. Long-Term Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Fertility. In Sustainable Agriculture Volume 2; Lichtfouse, E., Hamelin, M., Navarrete, M., Debaeke, P., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2011; pp. 761–786. ISBN 978-94-007-0394-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bedada, W.; Karltun, E.; Lemenih, M.; Tolera, M. Long-Term Addition of Compost and NP Fertilizer Increases Crop Yield and Improves Soil Quality in Experiments on Smallholder Farms. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2014, 195, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.C.; Higgins, C.W.; Smallman, M.A.; Graham, M.; Ates, S. Herbage Yield, Lamb Growth and Foraging Behavior in Agrivoltaic Production System. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, W.; Meyer, T.K.; Tanikella, N.G.; Burnham, L.; Engel, J.; Schelly, C.; Pearce, J.M. Conceptual Design and Rationale for a New Agrivoltaics Concept: Pasture-Raised Rabbits and Solar Farming. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 282, 124476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascaris, A.S.; Handler, R.; Schelly, C.; Pearce, J.M. Life Cycle Assessment of Pasture-Based Agrivoltaic Systems: Emissions and Energy Use of Integrated Rabbit Production. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 2021, 3, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heins, B.J.; Sharpe, K.T.; Buchanan, E.S.; Reese, M.H. Agrivoltaics to Shade Cows in a Pasture-Based Dairy System. AIP Conference Proceedings 2022, 2635, 060001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Olk, D.C.; Fang, X.; He, Z.; Schmidt-Rohr, K. Influence of Animal Manure Application on the Chemical Structures of Soil Organic Matter as Investigated by Advanced Solid-State NMR and FT-IR Spectroscopy. Geoderma 2008, 146, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.R. Plant Nutrient and Economic Valus of Animal Manures. Journal of Animal Science 1979, 48, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UDROIU, N.-A. THE USE OF AGRIVOLTAIC SYSTEMS, AN ALTERNATIVE FOR ROMANIAN FARMERS. Scientific Papers. Series D. Animal Science. 2023, LXVI, No. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz de Otálora, X.; Epelde, L.; Arranz, J.; Garbisu, C.; Ruiz, R.; Mandaluniz, N. Regenerative Rotational Grazing Management of Dairy Sheep Increases Springtime Grass Production and Topsoil Carbon Storage. Ecological Indicators 2021, 125, 107484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturchio, M.A.; Kannenberg, S.A.; Knapp, A.K. Agrivoltaic Arrays Can Maintain Semi-Arid Grassland Productivity and Extend the Seasonality of Forage Quality. Applied Energy 2024, 356, 122418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, T.J.; Schütte, U.M.E.; Drown, D.M. Soil Disturbance Affects Plant Productivity via Soil Microbial Community Shifts. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.R.; van Es, H.M.; Schindelbeck, R.; Ristow, A.J.; Ryan, M. No-till and Cropping System Diversification Improve Soil Health and Crop Yield. Geoderma 2018, 328, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, G.; Singh, R.P. Conservation Tillage and Optimal Water Supply Enhance Microbial Enzyme (Glucosidase, Urease and Phosphatase) Activities in Fields under Wheat Cultivation during Various Nitrogen Management Practices. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2013, 59, 911–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaducci, S.; Yin, X.; Colauzzi, M. Agrivoltaic Systems to Optimise Land Use for Electric Energy Production. Applied Energy 2018, 220, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juillion, P.; Lopez, G.; Fumey, D.; Lesniak, V.; Génard, M.; Vercambre, G. Shading Apple Trees with an Agrivoltaic System: Impact on Water Relations, Leaf Morphophysiological Characteristics and Yield Determinants. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 306, 111434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghami, M.R.; Hizam, H.; Gomes, C.; Radzi, M.A.; Rezadad, M.I.; Hajighorbani, S. Power Loss Due to Soiling on Solar Panel: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 59, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, N.Z.; Fox, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ave, K.; Carvalho, F.; Li, Y.; Walston, L.J.; Ricketts, M.P.; Jordaan, S.M.; Abou Najm, M.; et al. Impacts of Photovoltaic Solar Energy on Soil Carbon: A Global Systematic Review and Framework. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 208, 115032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, E.; Karas, T.; Janski, J.; Macknick, J.; Ravi, S. Managed Sheep Grazing Can Improve Soil Quality and Carbon Sequestration at Solar Photovoltaic Sites. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, E.K.; Gruss, S.M.; Schull, V.Z.; Gosney, M.J.; Mickelbart, M.V.; Brouder, S.; Gitau, M.W.; Bermel, P.; Tuinstra, M.R.; Agrawal, R. Optimized Agrivoltaic Tracking for Nearly-Full Commodity Crop and Energy Production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 191, 114018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willockx, B.; Reher, T.; Lavaert, C.; Herteleer, B.; Van de Poel, B.; Cappelle, J. Design and Evaluation of an Agrivoltaic System for a Pear Orchard. Applied Energy 2024, 353, 122166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Meng, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Ning, X.; Chen, F.; Omer, A.A.A.; Ingenhoff, J.; Liu, W. Increasing the Comprehensive Economic Benefits of Farmland with Even-Lighting Agrivoltaic Systems. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0254482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Greenfield, E.J.; Hoehn, R.E.; Lapoint, E. Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Trees in Urban and Community Areas of the United States. Environmental Pollution 2013, 178, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Vandewetering, N.; Sadat, S.A.; Pearce, J.M. Wood- and Cable-Based Variable Tilt Stilt-Mounted Solar Photovoltaic Racking System. Designs 2024, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Vandewetering, N.; Pearce, J.M. Solar Photovoltaic Wood Racking Mechanical Design for Trellis-Based Agrivoltaics. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0294682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewetering, N.; Jamil, U.; Pearce, J.M. Ballast-Supported Foundation Designs for Low-Cost Open-Source Solar Photovoltaic Racking. Designs 2024, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).